Abstract

Signaling through the IGF-I receptor by locally produced IGF-I or -II is critical for normal skeletal muscle development and repair after injury. In most tissues, IGF action is modulated by IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs). IGFBP-5 is produced by muscle cells, and previous studies have suggested that when overexpressed it may either facilitate or inhibit IGF actions, and thus potentially enhance or diminish IGF-mediated myoblast differentiation or survival. To resolve these contradictory observations and discern the mechanisms of action of IGFBP-5, we studied its effects in cultured muscle cells. Purified wild-type (WT) mouse IGFBP-5 or a variant with diminished extracellular matrix binding (C domain mutant) each prevented differentiation at final concentrations as low as 3.5 nm, whereas analogs with reduced IGF binding (N domain mutant) were ineffective even at 100 nm. None of the IGFBP-5 variants altered cell number. An IGF-I analog (R3IGF-I) with diminished affinity for IGFBPs promoted full muscle differentiation in the presence of IGFBP-5WT, showing that IGFBP-5 interferes with IGF-dependent signaling pathways in myoblasts. When IGFBP-5WT or variants were overexpressed by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer, concentrations in muscle culture medium reached 500 nm, and differentiation was inhibited, even by IGFBP-5N. As 200 nm of purified IGFBP-5N prevented activation of the IGF-I receptor by 10 nm IGF-II as effectively as 2 nm of IGFBP-5WT, our results not only demonstrate that IGFBP-5 variants with reduced IGF binding affinity impair muscle differentiation by blocking IGF actions, but underscore the need for caution when labeling effects of IGFBPs as IGF independent because even low-affinity analogs may potently inhibit IGF-I or -II if present at high enough concentrations in biological fluids.

THE MAINTENANCE AND repair of skeletal muscle is controlled by an interplay between systemically derived and local signals mediated by hormones, peptide growth factors, and other molecules acting in concert with a genetically determined hierarchical program of muscle-specific transcription factors (1,2,3). Among growth factors with major actions on muscle are IGF-I and -II (4,5), closely related single-chain secreted proteins that bind with high affinity to the IGF-I receptor, a membrane-spanning ligand-activated tyrosine protein kinase (6). The importance of IGF action in muscle has been illustrated through a series of genetic manipulations in mice. IGF-I receptor deficiency led to muscle hypoplasia, and death in the perinatal period secondary to respiratory failure caused by severe muscle weakness (7), whereas targeted overexpression of IGF-I stimulated an increase in muscle mass throughout the life span (8), and enhanced anabolic responses to exercise (9). Although the signal transduction mechanisms downstream of the IGF-I receptor that are responsible for its actions in muscle have not been characterized fully, recent evidence supports a major role for the phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway (10,11,12), and overexpression of an activated Akt in muscle leads to hypertrophy similar to that seen with IGF-I (13).

IGF-I and -II also bind to a family of six soluble IGF binding proteins, IGFBP-1 through -6 (14,15). It is agreed that IGFBPs play modulating roles in IGF action, potentially by regulating both IGF half-life and access to the IGF-I receptor (14,15), although other studies suggest that these proteins may mediate additional biological effects independent of their ability to bind IGFs (14,15). The predominant IGFBP in muscle is IGFBP-5 (16), a 252-amino acid secreted protein that consists of highly conserved, cysteine-rich, amino (NH2)- and carboxyl (COOH)-terminal domains, and a poorly conserved central segment (17,18). The NH2-terminal domain of IGFBP-5 encodes the primary IGF binding site, although the COOH-terminal region also is needed for high-affinity ligand binding (19,20). The COOH-terminal portion contains additional determinants that interact with extracellular matrix proteins (21,22,23), and encodes a binding site for acid-labile subunit, the protein that forms a ternary complex with either IGFBP-3 or -5 and IGF-I or -II in the blood (24). IGFBP-5 is synthesized in the myotomal component of the somite during early embryonic development (25), and its expression is induced in muscle after differentiation (16). Despite this information, direct evidence defining specific roles for IGFBP-5 in skeletal muscle remains limited. Global deficiency of IGFBP-5 in mice had a minimal impact on muscle or on whole organism physiology (26), whereas its systemic overexpression caused impaired growth (27). In cultured muscle cells, precocious overexpression of wild-type (WT) IGFBP-5 blocked differentiation, which could be overcome by added IGF-I or IGF-II (28,29), whereas a version of the protein with diminished IGF binding capability had no effect (29). In contrast, addition of purified bone-derived human IGFBP-5 to muscle cells enhanced differentiation (30).

To address the roles of IGFBP-5 in muscle, we purified mouse IGFBP-5 from a mammalian cell expression system, along with modified versions of the protein with reduced affinity for IGFs or for extracellular matrix, and studied the effects of these molecules on myoblast differentiation. All IGFBP-5 molecules tested inhibited acute activation of the IGF-I receptor by IGF-II, but with dose-potencies that varied over two orders of magnitude. Concentrations of IGFBP-5 or variants that blocked the IGF-I receptor also prevented muscle differentiation. Taken together, our results underscore the need for caution when labeling effects of IGFBPs as IGF independent because even analogs with diminished affinity for IGF-I or -II are able to bind these ligands and inhibit their biological effects if present at high enough concentrations in biological fluids.

RESULTS

Expression and Purification of IGFBP-5 Variants

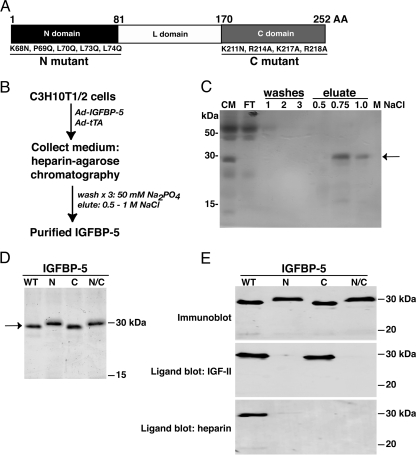

Several investigators have introduced amino acid modifications into IGFBP-5 as a way of characterizing different functional domains of the protein. Results of these experiments have shown that the primary binding site for IGF-I or -II resides in the NH2-terminal third of the molecule (19), with accessory contributions from the COOH-terminal part of the protein (20). Other studies have indicated that interactions with the extracellular matrix, as manifested by the ability of IGFBP-5 to bind heparin, related sulfated proteoglycans, and other matrix proteins, are mediated by amino acids located in the COOH-terminal part of the molecule (21,22,23). We generated recombinant adenoviruses encoding a series of IGFBP-5 variants with specific amino acid substitutions in the NH2- or COOH-terminal segments of the protein, or in both domains, as depicted in Fig. 1A. Based on published studies, we expected that an IGFBP-5 protein with NH2-terminal modifications would have reduced affinity for IGF-I or -II (19,20), whereas changes in the COOH-terminal segment would lead to diminished ability to bind heparin (21). After infection of C3H10T1/2 cells with Ad-IGFBP-5WT, Ad-IGFBP-5N, Ad-IGFBP-5C, or Ad-IGFBP-5N/C according to the scheme outlined in Fig. 1B, IGFBP-5 accumulated in the conditioned medium and could be purified readily by heparin-agarose affinity chromatography (Fig. 1, C and D), but with different patterns of elution (Fig. 1C and data not shown). After purification, all four proteins were recognized to an equivalent extent by a polyclonal anti-IGFBP-5 antibody, but only IGFBP-5WT and IGFBP-5C could bind IGF-II, and only IGFBP-5WT could interact strongly with heparin by ligand blotting (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Purification and Characterization of Recombinant Mouse IGFBP-5 and Variants

A, Diagram of mouse IGFBP-5, showing N-, L-, and C-domains. Amino acid substitutions to create N and C mutants are indicated. B, Purification scheme using heparin-affinity chromatography. C, Purification of IGFBP-5WT, showing elution pattern from heparin-agarose column (CM, conditioned culture medium; FT, flow through) by silver staining. D, Detection of purified IGFBP-5 and variants after staining with Gelcode blue. E, Detection of purified IGFBP-5 and variants (N, C, and N/C) by immunoblotting (top panel), IGF-II ligand blotting (middle), and heparin ligand blotting (bottom).

IGFBP-5 Inhibits MyoD-Induced Muscle Differentiation by IGF-Dependent Mechanisms

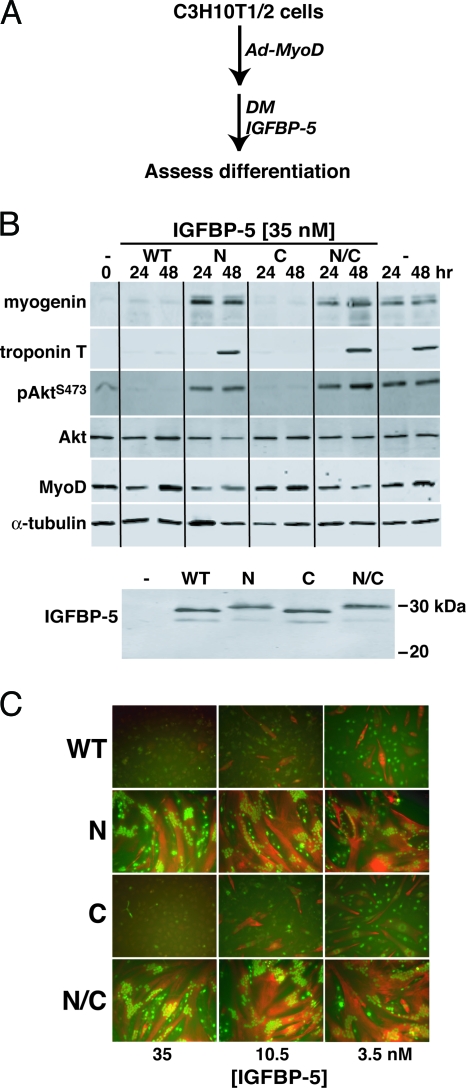

To examine the effects of modified IGFBP-5 proteins on MyoD-mediated myoblast differentiation, graded amounts of purified IGFBP-5WT or variants were added in DMEM plus 2% horse serum (DM) to confluent Ad-MyoD-infected C3H10T1/2 cells, and the rate and extent of differentiation was monitored over the ensuing 48 h, according to the scheme outlined in Fig. 2A. As shown in Fig. 2, B and C, biochemical and morphological differentiation were blocked by IGFBP-5WT or IGFBP-5C when added at final concentrations of 3.5, 10.5, or 35 nm, but not by IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C. Of particular note was the sustained activation of Akt in the presence of the highest concentration of IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C, as indicated by its phosphorylation on serine 473 (pAktS473 in Fig. 2B), and the lack of Akt phosphorylation after incubation with IGFBP-5WT or IGFBP-5C because Akt activity has been shown to be required for IGF-mediated muscle differentiation (12,31,32,33). The lack of effectiveness of IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C was not because of their diminished stability, as nearly equivalent concentrations of each intact protein were detected in the medium after incubation for up to 48 h (Fig. 2B, lower panel), although degradation products also were seen for each analog. As illustrated graphically in Fig. 3, A–C, added IGFBP-5WT or IGFBP-5C caused dose-dependent inhibition of all aspects of myoblast differentiation, including expression of the muscle-specific transcription factor, myogenin, the extent of myocyte fusion, and the overall size of the resultant myotubes. In contrast, IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C had no effect on any of these parameters, even at 35 nm, the highest dose added, yielding results that were indistinguishable from those seen in the absence of added binding proteins (Fig. 3, A–C).

Figure 2.

IGFBP-5 Inhibits MyoD-Mediated Muscle Differentiation

Results are shown of experiments using C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal stem cells infected with Ad-MyoD, followed by incubation in DM for 24 or 48 h with added purified IGFBP-5 (WT), or variants (N, C, or N/C). A, Experimental scheme. B, Immunoblots of whole cell protein lysates for myogenin, troponin T, Akt phosphorylated at serine 473 (pAkt S473), Akt, MyoD, α-tubulin, and immunoblots of conditioned DM for IGFBP-5. The final IGFBP-5 concentrations in DM were 35 nm. C, Immunocytochemistry for troponin T (red) and myogenin (green) after incubation for 48 h with 3.5, 10.5, or 35 nm of IGFBP-5 or variants as indicated. Magnification, ×200.

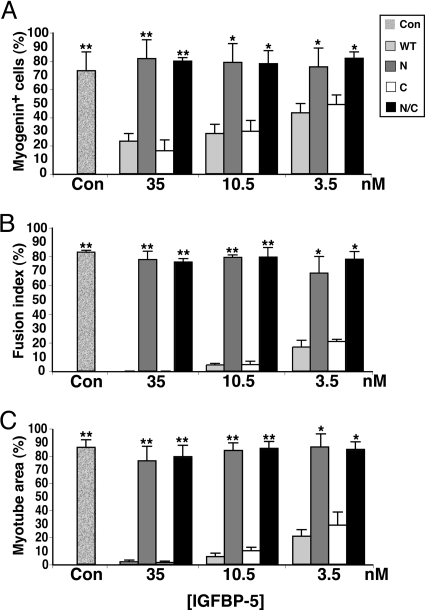

Figure 3.

IGFBP-5 Inhibits Muscle Differentiation

C3H10T1/2 cells were infected with Ad-MyoD, followed by incubation in DM for 48 h with purified IGFBP-5 (WT), or variants (N, C, or N/C) at 3.5, 10.5, or 35 nm, as in Fig. 2. A, Percentage of myogenin-positive cells (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 vs. cells incubated with IGFBP-5 WT or C). B, Fusion Index (*, P < 0.002; **, P < 0.003 vs. cells incubated with IGFBP-5 WT or C). C, Myotube area (*, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.005 vs. cells incubated with IGFBP-5 WT or C). Con, Cells incubated without IGFBP-5.

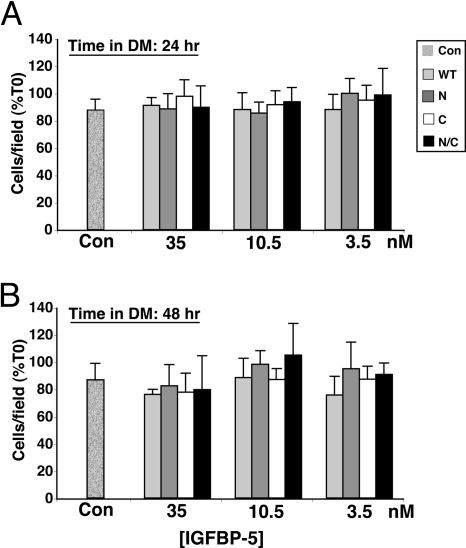

Previous studies have suggested that IGFBP-5 could increase myoblast survival (29), an action potentially independent of its effects on muscle differentiation (29). To address this possibility, we counted living cells after incubation in DM for 24 and 48 h. As depicted in Fig. 4, A and B, cell number was unchanged under all conditions. Thus, at least in this model system, exposure to IGFBP-5WT or variants did not cause a decline in myoblast number.

Figure 4.

IGFBP-5 Does Not Alter Cell Viability

C3H10T1/2 cells were infected with Ad-MyoD, followed by incubation in DM for up to 48 h with purified IGFBP-5 (WT), or variants (N, C, or N/C) at 3.5, 10.5, or 35 nm, as in Fig. 2. A, Cell number after 24 h in DM. B, Cell number after 48 h in DM. Results are presented as percentage of time 0 (mean ± sd) and were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Con, Cells incubated without IGFBP-5. None of the results were statistically different from the others.

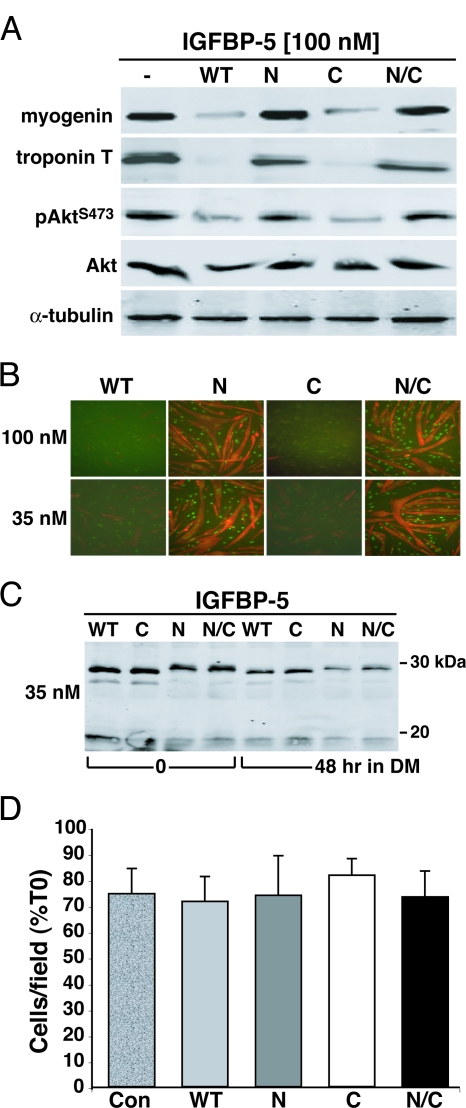

To eliminate the possibility that the effects of IGFBP-5 and variants were specific for myoblasts derived from MyoD-converted C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal stem cells, we examined the consequences of exposure of the C2 muscle cell line to these purified proteins. As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, addition of 35 or 100 nm of IGFBP-5WT or IGFBP-5C to confluent C2 cells in DM prevented both biochemical and morphological differentiation, whereas equivalent amounts of IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C had no effect. As seen in Fig. 5D, none of the IGFBP-5 analogs caused a change in the number of living myocytes after incubation for 48 h, thus illustrating that they exerted no measurable effect on either cell proliferation or viability. Thus, based on the results depicted in Figs. 2–5, mutations in the NH2-terminal IGF binding domain of IGFBP-5 appear to cripple the ability of the protein to interfere with skeletal muscle differentiation, whereas alterations in the COOH-terminal portion of the molecule do not.

Figure 5.

IGFBP-5 Inhibits Differentiation of C2 Myoblasts without Altering Cell Viability

Cells were incubated in DM for 48 h with purified IGFBP-5 (WT), or variants (N, C, or N/C) at 35 or 100 nm. A, Immunoblots of whole cell protein lysates for myogenin, troponin T, Akt phosphorylated at serine 473 (pAktS473), Akt, and α-tubulin. B, Immunocytochemistry for troponin T (red) and myogenin (green). Magnification, ×200. C, Immunoblots at 0 and 48 h of conditioned culture medium for IGFBP-5 or variants added at time 0. D, Cell number at 48 h after addition of 100 nm of IGFBP-5WT or variants. Results are presented as percentage of time 0 (mean ± sd) and were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Con, Cells incubated without IGFBP-5. None of the results were statistically different from the others.

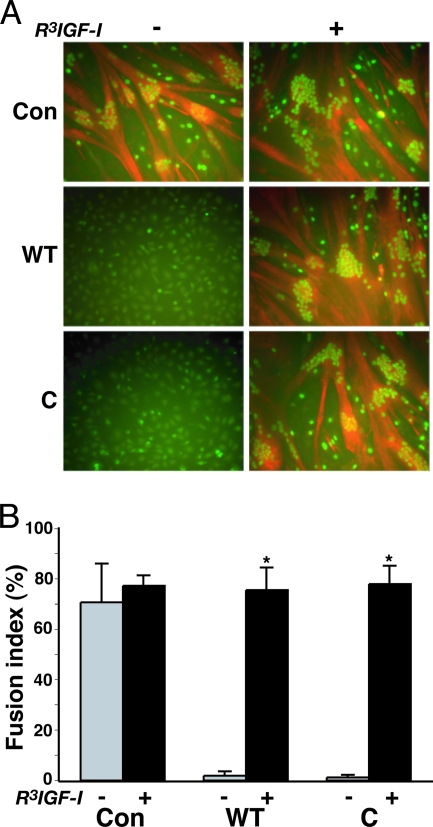

One interpretation of the studies pictured in Figs. 2–5 is that IGFBP-5WT and IGFBP-5C are able to prevent muscle differentiation by inhibiting the ability of endogenously produced IGF-II to activate the IGF-I receptor in both MyoD-converted C3H10T1/2 cells and C2 myoblasts (34,35). If true, then an IGF analog with limited affinity for IGFBP-5 but normal affinity for the IGF-I receptor should reverse this impairment. To test this hypothesis, confluent Ad-MyoD-infected C3H10T1/2 cells were incubated in DM with purified IGFBP-5WT or IGFBP-5C [35 nm] in the absence or presence of R3IGF-I [5 nm]. As illustrated in Fig. 6, under these conditions, R3IGF-I not only enhanced the overall size of myofibers in control cells over a 48-h exposure period, but more importantly promoted extensive differentiation in myoblasts incubated with IGFBP-5. Taken together, the results in Figs. 2–6 demonstrate that IGFBP-5 inhibits skeletal muscle differentiation by interfering with IGF actions, and strongly support the idea that it is the IGF-dependent effects of IGFBP-5 that are critical for its regulation of muscle differentiation.

Figure 6.

IGF-I Reverses the Inhibitory Effect of IGFBP-5 on MyoD-Mediated Muscle Differentiation

C3H10T1/2 cells were infected with Ad-MyoD, followed by incubation in DM for 48 h with purified IGFBP-5 (WT or C) [35 nm] with or without R3IGF-I [5 nm]. A, Immunocytochemistry for myogenin (green) and troponin T (red). Magnification, ×200. B, Fusion index (*, P < 0.003 vs. cells not incubated with R3IGF-I). Results are presented as mean ± sd and were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Con, Cells incubated without IGFBP-5.

IGFBP-5 Variants with Poor IGF Binding Affinity Can Inhibit MyoD-Mediated Muscle Differentiation When Massively Overexpressed

In several model cell systems, the effects of overexpressed IGFBP-5 or variants have been ascribed to their IGF-independent actions (reviewed in Ref.18), although in nearly all of these cases the results have not been subjected to rigorous scrutiny. Here we have tested the idea that overexpression of IGFBP-5 variants, which were otherwise ineffective when added directly at defined concentrations to myoblasts, could inhibit differentiation, primarily by interfering with IGF actions. Ad-MyoD-infected C3H10T1/2 cells were infected 1 d later with doxycycline (Dox)-regulated recombinant adenoviruses encoding modified versions of IGFBP-5, following the scheme outlined in Fig. 7A, and the rate and extent of differentiation was assessed over the ensuing 48 h. Under the conditions of these experiments, the concentration of IGFBP-5 in conditioned DM reached > 500 nm after 48 h, but was < 0.5 nm in the presence of Dox (Fig. 7B, and data not shown). As seen in Fig. 7C, myotube formation was obliterated when any of the IGFBP-5 variants was overexpressed to this level but was normal when Dox was added at the onset of adenoviral infection and production of IGFBP-5 was blocked. Remarkably, overexpression of IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C inhibited differentiation and reduced the number of myogenin-positive myocytes by approximately 75%, an effect that was almost as extensive as the 95% decline seen with IGFBP-5WT (Fig. 7D). There was no effect on muscle cell number when any of the IGFBP-5 variants was overexpressed (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7.

Overexpression of IGFBP-5 or Variants Inhibits MyoD-Mediated Muscle Differentiation

A, C3H10T1/2 cells were infected with Ad-MyoD and Ad-tTA, followed by infection with Ad-IGFBP-5WT or variants, and incubation in DM ± Dox for 48 h. The final concentration of IGFBP-5 in conditioned medium after 48 h in DM ranged from 500–700 nm. B, Quantitative immunoblots for IGFBP-5WT and variants (N, C, or N/C), using 1–6 μl of conditioned DM and graded amounts of purified IGFBP-5WT as standards. C, Immunocytochemistry for myogenin (green) and troponin T (red). Magnification, ×200. D, Myogenin-positive nuclei (mean ± sd; *, P < 0.003; **, P < 0.01 vs. no Dox). E, Cell number (mean ± sd). Results for D and E were calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

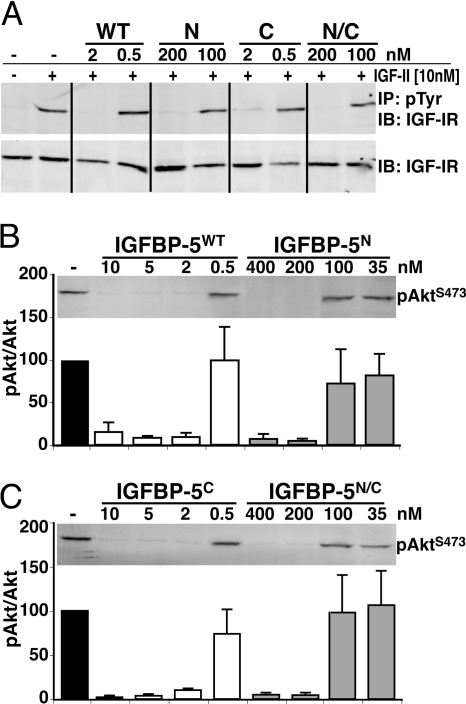

To address this conundrum of inhibition of muscle differentiation in the presence of high concentrations of IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C (Fig. 6) but not lower amounts (Figs. 2 and 3), we analyzed the acute effects of graded doses of the purified proteins on IGF-II-stimulated activation of the IGF-I receptor. Illustrated in Fig. 8 are results of experiments in which different amounts of purified IGFBP-5WT or variants were added to C3H10T1/2 cells together with 10 nm of recombinant human IGF-II. As seen in Fig. 8, IGFBP-5WT and IGFBP-5C each prevented acute IGF-II-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of the IGF-I receptor and phosphorylation of Akt at serine 473 at concentrations of 2 nm or greater. By contrast, IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C were much less effective, being fully inhibitory only at concentrations of 200 or 400 nm. This rightward shift in the inhibitory dose-response curve for IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C is consistent with their greatly reduced affinity for IGF-I or -II compared with IGFBP-5WT or IGFBP-5C (19,20). Nevertheless, despite the diminished dose-potency of either IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C, the results in Fig. 7 show that both are effective inhibitors of IGF-II at concentrations achieved in Fig. 6 by overexpression via adenoviral-mediated gene delivery.

Figure 8.

Dose-Dependent Inhibition of IGF-I Receptor Activation by IGFBP-5

C3H10T1/2 cells were incubated in serum-free medium for 3 h followed by addition of new serum-free medium for 30 min with IGF-II [10 nm] plus IGFBP-5WT or variants (N, C, or N/C) at the concentrations indicated. A, Immunoblots (IB) of anti-phosphotyrosine (pTyr) immunoprecipitates (IP) and whole cell protein lysates for the IGF-I receptor (IGF-IR). A representative experiment (of two performed) is shown. B and C, Immunoblots of whole cell protein lysates for Akt phosphorylated at serine 473 (pAktS473). Relative levels of pAktS473 normalized to Akt are indicated graphically at the bottom of the panels. A representative experiment (of four performed) is shown.

DISCUSSION

IGFBP-5 Inhibits Muscle Differentiation by Blocking IGF Actions

IGFBP-5, the most conserved member of the IGFBP family (18), can function as either a facilitator or inhibitor of IGF action depending on the cell type and context (17,18), and additionally has been reported to exert biological effects that are independent of its ability to bind IGF-I or IGF-II with high affinity (17,18). In skeletal myoblasts, the preponderance of evidence indicates that IGFBP-5 blocks IGF actions, and inhibits IGF-mediated muscle differentiation, although this conclusion is based solely on results of experiments involving overexpression of IGFBP-5 cDNAs in muscle cells (28,29). By contrast, a single report showed that direct addition of purified human IGFBP-5 to L6A1 myoblasts enhanced IGF-I-stimulated differentiation in a dose-dependent way up to a final concentration of approximately 8 nm (30). Here we have reexamined the role and mechanisms of action of IGFBP-5 in muscle. We find in contrast to the results of Ewton et al. (30), that purified WT mouse IGFBP-5, when added to culture medium at concentrations of 3.5 nm or greater, blocked muscle differentiation (Figs. 2–5). Because normal differentiation was restored in the presence of IGFBP-5WT by R3IGF-I, an IGF analog that interacts normally with the IGF-I receptor but poorly with IGFBPs (36) (Fig. 6), our results clearly demonstrate that IGFBP-5 is primarily an inhibitor of IGF actions in cultured skeletal muscle cells. This conclusion is consistent with in vivo observations showing that IGFBP-5 prevented cell proliferation mediated by locally produced IGF-I in the muscle environment after denervation injury (37), although additional IGF-independent actions cannot be ruled out. In support of the inhibitory effects of IGFBP-5 on muscle differentiation, we additionally found that a purified IGFBP-5 variant containing amino acid substitutions that reduced interactions with extracellular matrix proteins (IGFBP-5C), also potently blocked differentiation, whereas analogs with diminished affinity for IGF-I and IGF-II (IGFBP-5N and IGFBP-5N/C), did not (Figs. 2 and 5).

The NH2-terminal third of IGFBP-5 encodes the major determinants for high-affinity ligand binding, and the amino acid substitutions found in IGFBP-5N have been reported to cause a 60- to 1000-fold decline in IGF binding (19,20). In previous biological studies, IGFBP-5N was unable to block IGF-I-mediated DNA synthesis at concentrations up to 35 nm or smooth muscle cell migration at 70 nm (19). We found that purified IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C were ineffective inhibitors of muscle differentiation at even higher concentrations [100 nm], and at this dose could not block stimulation of IGF-I receptor tyrosine phosphorylation by 10 nm IGF-II or activation of the serine-threonine kinase, Akt, whereas either IGFBP-5WT or IGFBP-5C were fully potent at 2 nm (Fig. 8). Surprisingly, when added to fibroblasts at a higher concentration [200 nm], purified IGFBP-5N or IGFBP-5N/C each completely inhibited IGF-I receptor and Akt activation (Fig. 8), and when overexpressed in muscle cells by adenoviral-mediated gene transfer so that the concentrations in culture medium reached 500 nm, both IGFBP-5N and IGFBP-5N/C prevented differentiation (Fig. 7). Thus, not only do we conclude that in muscle IGFBP-5 is predominantly an inhibitor of IGF action, but our results also suggest a need for caution when attributing effects of IGFBPs as IGF independent because even analogs with diminished affinity for IGF-I or -II are able to bind these ligands if present at high enough concentrations in biological fluids.

No Evidence for IGF-Independent Effects of IGFBP-5 in Muscle Cells

A previous study has shown that when overexpressed in a muscle cell line, both IGFBP-5WT and IGFBP-5N increased myoblast viability by steps involving a reduction in the concentrations of death-promoting caspases 3 and 9 (29). This survival effect also was considered to be an IGF-independent action of IGFBP-5 (29), but because the amount of IGFBP-5 secreted by these cells was not measured, this interpretation may now be challenged. In our experiments, neither IGFBP-5WT nor any of the variants used had an effect on muscle cell number, either when added exogenously or when overexpressed (Figs. 3–5 and 7). In contrast, others have noted opposite effects on growth of breast cancer cells (38), or on viability of osteosarcoma cells (39), depending on whether IGFBP-5 was added to culture medium or overexpressed. At present, there appears to be no unifying hypothesis to explain these discordant results.

What Actions of IGFBP-5 in Muscle Cells Might Be IGF Independent?

During muscle repair after injury, newly formed myoblasts migrate into the wound (3). IGFBP-5 can stimulate migation of vascular smooth muscle cells at relatively low concentrations (<7 nm), and IGFBP-5N is just as effective as IGFBP-5WT (40), supporting the hypothesis that this is an IGF-independent effect. It remains to be determined whether skeletal myoblasts respond similarly.

IGFBP-5 also has been shown to bind to the extracellular matrix protein, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, through the same COOH-terminal sequences involved in interactions with heparin, thrombospondin, and vitronectin (41). Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 blocks the generation of plasmin from plasminogen, which in turn is inhibited by IGFBP-5 (18,41). In addition, IGFBP-5 has been found to stimulate the plasminogen activator, tPA (42). Because plasmin is involved in wound repair and extracellular matrix remodeling (18), these results indicate that IGFBP-5 could modulate this process potentially in an IGF-independent way. Again, it remains to be shown if IGFBP-5 exerts similar effects in skeletal muscle. To date, IGFBP-5-deficient mice have not been demonstrated to have a skeletal muscle phenotype, but their response to muscle injury has not been measured (26).

In summary, we have shown that IGFBP-5 is a potent inhibitor of muscle differentiation via its ability to neutralize IGF actions through high-affinity growth factor binding, and presumptive sequestration away from the IGF-I receptor. Our results also raise a cautionary note to conclusions reached with IGFBP-5 mutants about putative IGF-independent effects of this protein, when studied under conditions in which the amount of IGFBP-5 in biological fluids is undefined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Antibodies

Fetal calf serum, newborn calf serum, horse serum, DMEM, and PBS were from Mediatech-Cellgrow (Herndon, VA). Trypsin/EDTA solution and Silver Quest silver staining kit were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Dox, from CLONTECH (Palo Alto, CA), was dissolved in distilled water at a concentration of 1 mg/ml and stored at −20 C until use at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. Protease inhibitor tablets were purchased from Roche Applied Sciences (Indianapolis, IN), okadaic acid from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA), and sodium orthovanadate and heparin agarose from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit was obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The BCA protein assay kit and Gelcode blue staining solution were from Pierce Biotechnologies (Rockford, IL), Immobilon-FL from Millipore Corp. (Billerico, MA), and AquaBlock EIA/WIB solution from East Coast Biologicals (North Berwick, ME). Restriction enzymes, buffers, ligases, and polymerases were purchased from Roche Applied Sciences, BD Biosciences (CLONTECH), and Fermentas (Hanover, MD). Recombinant human IGF-II, biotinylated human IGF-II, and R3IGF-I were purchased from GroPep (Adelaide, Australia). The following hybridoma cell lines were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (Iowa City, IA): F5D (anti-myogenin, W. E. Wright), CT3 (anti-troponin T, J. J.-C. Lin). The monoclonal antibody to MyoD was from BD Biosciences (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and polyclonal antibodies to Akt and phospho-Akt (Ser473) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Polyclonal antibodies against phospho-tyrosine, IGFBP-5, and the IGF-I receptor β-subunit were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The following antibody conjugates were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR): goat antimouse IgG1-Alexa 488, goat antimouse IgG2b-Alexa 594, goat-antimouse IgG-Alexa 680. Goat-antirabbit IgG-IR800 was from Rockland Immunochemical Inc. (Gilbertsville, PA). Biotin-conjugated heparin was from Calbiochem, EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Other chemicals were reagent grade and were purchased from commercial suppliers.

Preparation and Purification of Recombinant Adenoviruses

Ad-MyoD and Ad-tTA have been described (35). The entire coding region of mouse IGFBP-5 was cloned by PCR, using cDNA from C2 myoblasts and the following primers: sense strand, 5′-ACGCGGTCGACATGGTGATCAG CGTGGTCCTC-3′ and antisense, 5′-TGCGCGAATTCTCACTCAACGTTACTGCTGTC-3′. After digestion with SalI and EcoRI restriction enzymes (underlined), the PCR fragment was ligated into the pShuttle:TetR adenoviral shuttle vector, and the DNA sequence obtained. Specific mutations were introduced with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit. To generate the IGFBP-5 N mutant [Lys68 to Asn, Pro69 to Gln, Leu70 to Gln, Leu73 to Gln, and Leu74 to Gln (19)], the following primers were used: sense strand, 5′-CTCCCCCGGCAGGATGAGGAGAACCAG CAGCATGCCCAGCAGCACGGCCGCGGGTTTGCCTC-3′, and antisense, 5′-GAGGCAAACC CCGCGGCCGTGCTGCTGGGCATGCTGGTT CTCCTCATCCTGCCGGGGAG-3′. For the C mutant [Lys211 to Asn, Arg214 to Ala, Lys217 to Ala, Arg 218 to Ala (21)] the following primers were used: sense strand, 5′-AAGAGAAAGCAGTGTAATCCCTCCGCTGGCCGCGCTGCAGGCATCTGCTGG-3′, and antisense, 5′-CCAGCAGATGCCTGCAGCGCGGCCAGCGGAGGGATTACACTGCTTTCTCTT-3′. The IGFBP-5 N/C double mutant was prepared by combining specific segments of N and C mutants. All IGFBP-5 cDNAs were subcloned into pShuttle:TetR and sequenced. All expected modifications were verified and no unwanted nucleotide changes were introduced. Recombinant adenoviruses were generated, purified, and titered as previously described (35).

Cell Culture and Gene Transfer with Recombinant Adenoviruses

C3H10T1/2 mouse embryonic fibroblasts (ATCC catalog number CCL226) were incubated on gelatin-coated tissue culture dishes in growth medium (35). Cells were infected at 50% of confluent density with Ad-MyoD and Ad-tTA (35), and 24 h later with Ad-IGFBP-5 or variants at multiplicities of infection of 500 in DM with or without Dox, as described (35) [Dox blocks the activity of tTA, a tetracycline-inhibited transcriptional activator, which stimulates expression of the gene encoding each IGFBP-5 protein]. Under these conditions, approximately 90% of cells were infected with all three viruses. C2 myoblasts were incubated on gelatin-coated tissue culture dishes in growth medium at 37 C in humidified air with 5% CO2. Cells were washed and DM added at approximately 95% of confluent density, as described (16).

Purification and Use of IGFBP-5 and IGFBP-5 Variants

C3H10T1/2 cells were infected with Ad-tTA plus either Ad-IGFBP-5WT, Ad-IGFBP-5N, Ad-IGFBP-5C, or Ad-IGFBP-5N/C. Medium (DMEM plus 0.5% horse serum) was conditioned for 48 h between d 1 and 3 of infection, clarified by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 10 min at 4 C, and applied to heparin-Sepharose columns at 4 C. After three washes with 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 6.5), proteins were eluted by a step-wise NaCl gradient in 10 mm sodium phosphate (pH 6.5). IGFBP-5WT eluted primarily at 0.75–1 m NaCl, and IGFBP-5N, IGFBP-5N/C, and IGFBP-5C at 0.5–0.75 m NaCl. Purity, yield, and quality were assessed after SDS-PAGE and silver staining, and concentrations determined by comparison to BSA standards after SDS-PAGE and staining with Gelcode blue. Purified proteins were stored in aliquots at −80 C in 0.75–1 m NaCl, 1 mm Na2EDTA, 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), plus 10% glycerol. Purified IGFBP-5WT or variants were added in DM to Ad-MyoD-infected C3H10T1/2 cells or to C2 myoblasts at 95% of confluent density, and incubated for 24–48 h. For short-term studies of IGF signaling, IGFBP-5WT or variants at the indicated concentrations and 10 nm IGF-II were added for 30 min to C3H10T1/2 cells at 50% of confluent density that were serum starved for 3 h.

Protein Isolation, Immunoblotting, and Ligand Blotting

Whole cell protein lysates and conditioned cultured medium were prepared as described (35), and aliquots stored at −80 C until use. Protein samples (30 μg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to Immobilon-FL, blocked in AquaBlock, and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies (35). Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: anti-IGFBP-5 (1:1000), anti-myogenin supernatant (1:50), anti-Akt (1:1000), anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) (1:1000), anti-MyoD (1:2000), anti-troponin-T (1:1000), and the appropriate conjugated secondary antibody at 1:5000. Images were acquired using a LiCoR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System, and analyzed with version 2.0 analysis software (LiCoR, Lincoln, NE). For immunoprecipitation studies, cellular protein lysates (150 μg) were incubated overnight at 4 C with phospho-tyrosine antibody (1 μg), followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with an IGF-I receptor β subunit antibody (1:1000 dilution), and other steps as above. For ligand blotting, 1–20 μl of conditioned medium was separated under nondenaturing conditions by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-FL, blocked in Aquablock, and incubated with biotin-conjugated heparin (20 μg/ml) or biotin-conjugated IGF-II (100 ng/ml) in 50% AquaBlock, 50% PBS, and 0.1% Tween 20 overnight at 4 C. After binding, membranes were washed with TBS-T. After incubation with IR800-conjugated strepavidin (1:5000 dilution) and washing with TBS-T, images were acquired and analyzed as above.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed, permeabilized, blocked, and incubated with antibodies as described (35). Primary antibodies were added in blocking buffer for 16 h at 4 C (anti-myogenin, 1:50 dilution; anti-troponin-T, 1:1000; secondary antibodies at 1:1000). Images were captured with a Roper Scientific Cool Snap FX CCD camera attached to a Nikon Eclipse T300 fluorescent microscope using IP Labs 3.6 software. Adobe Photoshop was used for image processing and editing. Cell counts were determined using National Institutes of Health Image 1.63 program by counting nuclei stained with Hoechst 33258 dye from four to 10 microscopic fields at ×200 magnification. Myogenin-expressing cells, cell fusion index, and myotube area were assessed as described (12).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± sd. Statistical significance was determined using a paired Student’s t test. Results were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health RO1 Grants DK42748 and DK63073 (to P. R).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose

First Published Online September 20, 2007

Abbreviations: COOH, Carboxyl; DM, DMEM plus 2% horse serum; Dox, doxycycline; IGFBP, IGF binding protein; NH2, amino; WT, wild type.

References

- Buckingham M 2001 Skeletal muscle formation in vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev 11:440–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkes CA, Tapscott SJ 2005 MyoD and the transcriptional control of myogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 16:585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charge SB, Rudnicki MA 2004 Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol Rev 84:209–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DJ 2003 Signalling pathways that mediate skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Nat Cell Biol 5:87–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotwein P 2003 Insulin-like growth factor action and skeletal muscle growth, an in vivo perspective. Growth Horm IGF Res 13:303–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakae J, Kido Y, Accili D 2001 Distinct and overlapping functions of insulin and IGF-I receptors. Endocr Rev 22:818–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JP, Baker J, Perkins AS, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A 1993 Mice carrying null mutations of the genes encoding insulin-like growth factor I (Igf-1) and type 1 IGF receptor (Igf1r). Cell 75:59–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton-Davis ER, Shoturma DI, Musaro A, Rosenthal N, Sweeney HL 1998 Viral mediated expression of insulin-like growth factor I blocks the aging-related loss of skeletal muscle function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:15603–15607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul AC, Rosenthal N 2002 Different modes of hypertrophy in skeletal muscle fibers. J Cell Biol 156:751–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson EM, Tureckova J, Rotwein P 2004 Permissive roles of phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase and Akt in skeletal myocyte maturation. Mol Biol Cell 15:497–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt TN, Drujan D, Clarke BA, Panaro F, Timofeyva Y, Kline WO, Gonzalez M, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ 2004 The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol Cell 14:395–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson EM, Rotwein P 2007 Selective control of skeletal muscle differentiation by Akt1. J Biol Chem 282:5106–5110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai KM, Gonzalez M, Poueymirou WT, Kline WO, Na E, Zlotchenko E, Stitt TN, Economides AN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ 2004 Conditional activation of akt in adult skeletal muscle induces rapid hypertrophy. Mol Cell Biol 24:9295–9304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach LA, Headey SJ, Norton RS 2005 IGF-binding proteins—the pieces are falling into place. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16:228–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan C, Xu Q 2005 Roles of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding proteins in regulating IGF actions. Gen Comp Endocrinol 142:44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James PL, Jones SB, Busby WHJ, Clemmons DR, Rotwein P 1993 A highly conserved insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (IGFBP-5) is expressed during myoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem 268:22305–22312 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MR, Wolf E, Hoeflich A, Lahm H 2002 IGF-binding protein-5: flexible player in the IGF system and effector on its own. J Endocrinol 172:423–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie J, Allan GJ, Lochrie JD, Flint DJ 2006 Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5): a critical member of the IGF axis. Biochem J 395:1–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Moralez A, Andag U, Clarke JB, Busby WHJ, Clemmons DR 2000 Substitutions for hydrophobic amino acids in the N-terminal domains of IGFBP-3 and -5 markedly reduce IGF-I binding and alter their biologic actions. J Biol Chem 275:18188–18194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shand JH, Beattie J, Song H, Phillips K, Kelly SM, Flint DJ, Allan GJ 2003 Specific amino acid substitutions determine the differential contribution of the N- and C-terminal domains of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-5 in binding IGF-I. J Biol Chem 278:17859–17866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T, Clarke J, Parker A, Busby WJ, Nam T, Clemmons DR 1996 Substitution of specific amino acids in insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein 5 alters heparin binding and its change in affinity for IGF-I response to heparin. J Biol Chem 271:6099–6106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam TJ, Busby WHJ, Rees C, Clemmons DR 2000 Thrombospondin and osteopontin bind to insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-5 leading to an alteration in IGF-I-stimulated cell growth. Endocrinology 141:1100–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam T, Moralez A, Clemmons D 2002 Vitronectin binding to IGF binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) alters IGFBP-5 modulation of IGF-I actions. Endocrinology 143:30–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twigg SM, Baxter RC 1998 Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein 5 forms an alternative ternary complex with IGFs and the acid-labile subunit. J Biol Chem 273:6074–6079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BN, Jones SB, Streck RD, Wood TL, Rotwein P, Pintar JE 1994 Distinct expression patterns of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins 2 and 5 during fetal and postnatal development. Endocrinology 134:954–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Y, Schuller AG, Bradshaw S, Rotwein P, Ludwig T, Frystyk J, Pintar JE 2006 Diminished growth and enhanced glucose metabolism in triple knockout mice containing mutations of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3, -4, and -5. Mol Endocrinol 20:2173–2186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salih DA, Tripathi G, Holding C, Szestak TA, Gonzalez MI, Carter EJ, Cobb LJ, Eisemann JE, Pell JM 2004 Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 (Igfbp5) compromises survival, growth, muscle development, and fertility in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:4314–4319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James PL, Stewart CE, Rotwein P 1996 Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 modulates muscle differentiation through an insulin-like growth factor-dependent mechanism. J Cell Biol 133:683–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb LJ, Salih DA, Gonzalez I, Tripathi G, Carter EJ, Lovett F, Holding C, Pell JM 2004 Partitioning of IGFBP-5 actions in myogenesis: IGF-independent anti-apoptotic function. J Cell Sci 117:1737–1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewton DZ, Coolican SA, Mohan S, Chernausek SD, Florini JR 1998 Modulation of insulin-like growth factor actions in L6A1 myoblasts by insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP)-4 and IGFBP-5: a dual role for IGFBP-5. J Cell Physiol 177:47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng XD, Xu PZ, Chen ML, Hahn-Windgassen A, Skeen J, Jacobs J, Sundararajan D, Chen WS, Crawford SE, Coleman KG, Hay N 2003 Dwarfism, impaired skin development, skeletal muscle atrophy, delayed bone development, and impeded adipogenesis in mice lacking Akt1 and Akt2. Genes Dev 17:1352–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandromme M, Rochat A, Meier R, Carnac G, Besser D, Hemmings BA, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ 2001 Protein kinase B β/Akt2 plays a specific role in muscle differentiation. J Biol Chem 276:8173–8179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez I, Tripathi G, Carter EJ, Cobb LJ, Salih DA, Lovett FA, Holding C, Pell JM 2004 Akt2, a novel functional link between p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways in myogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 24:3607–3622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CE, Rotwein P 1996 Insulin-like growth factor-II is an autocrine survival factor for differentiating myoblasts. J Biol Chem 271:11330–11338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson EM, Hsieh MM, Rotwein P 2003 Autocrine growth factor signaling by insulin-like growth factor-II mediates MyoD-stimulated myocyte maturation. J Biol Chem 278:41109–41113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis GL, Aplin SE, Milner SJ, McNeil KA, Ballard FJ, Wallace JC 1993 Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-II binding to IGF-binding proteins and IGF receptors is modified by deletion of the N-terminal hexapeptide or substitution of arginine for glutamate-6 in IGF-II. Biochem J 293:713–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroni P, Schneider C 1994 Signaling by insulin-like growth factors in paralyzed skeletal muscle: rapid induction of IGF1 expression in muscle fibers and prevention of interstitial cell proliferation by IGF-BP5 and IGF-BP4. J Neurosci 14:3378–3388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt AJ, Dickson KA, McDougall F, Baxter RC 2003 Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 inhibits the growth of human breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem 278:29676–29685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P, Xu Q, Duan C 2004 Paradoxical actions of endogenous and exogenous insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 revealed by RNA interference analysis. J Biol Chem 279:32660–32666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh T, Gordon RE, Clemmons DR, Busby WHJ, Duan C 2003 Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell responses to insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I by local IGF-binding proteins. J Biol Chem 278:42886–42892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam TJ, Busby WJ, Clemmons DR 1997 Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 binds to plasminogen activator inhibitor-I. Endocrinology 138:2972–2978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell AM, Shand JH, Tonner E, Gamberoni M, Accorsi PA, Beattie J, Allan GJ, Flint DJ 2006 Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 activates plasminogen by interaction with tissue plasminogen activator, independently of its ability to bind to plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, insulin-like growth factor-I, or heparin. J Biol Chem 281:10883–10889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.