Abstract

The primary purpose of this study was to understand further the heterogeneity of popularity, by exploring contextual correlates of two dimensions of positive peer regard among seventh graders within two highly disparate sociodemographic groups: affluent suburban and low-income urban (N = 636). Three sets of attributes were examined, all consistently linked to social status in past research: rebellious behaviors (aggression, academic disengagement, delinquency, and substance use), academic application (effort at school and good grades), and physical attributes (attractiveness and athletic ability). The data provide empirical validation for the conceptual distinctions among peer-perceived admiration and social preference with adolescents from diverse contexts. More specifically, results showed that within each socioeconomic context (a) some forms of rebellious behaviors are clearly admired, (b) prosocial attributes are linked with peer-perceived admiration and social preference, (c) physical attractiveness and athletic skills are important for positive peer regard, the former particularly for suburban girls and the latter for suburban boys, and (d) aggression elicits admiration among early adolescents, but can also generate their disdain (i.e., lowered social preference). In the urban context, results provided evidence for the salience of distinct forms of rebellious and achievement oriented behaviors among different racial/ethnic groups as well.

The primary goal of this study was to understand further the heterogeneity of popularity, by exploring contextual correlates of two dimensions of positive peer regard among adolescents within affluent suburban and low-income urban contexts. In recent years, increasing recognition of the distinction between popularity as a measure of social preference (sociometric popularity) (e.g., Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982) and popularity as a function of social dominance, intimidation, and self-assurance (perceived popularity) (e.g., Weisfeld, Bloch, & Ivers, 1983, 1984), has resulted in burgeoning research linking these previously disparate traditions of inquiry. Indeed, it appears that adolescents—unlike their elementary school counterparts—do not necessarily like the same children they regard as popular (e.g., Adler & Adler, 1998); evidence suggests that sociometric popularity encompasses traits that youth might seek in close personal relationships such as consideration and kindness to others (e.g., Newcomb, Bukowski, & Pattee, 1993), whereas perceived popularity involves attributes that can be better appreciated at a "safe distance," i.e., power and even aggression (Graham & Juvonen, 2002).

Parkhurst and Hopmeyer's (1998) study with middle school students was one of the first to provide empirical support for the distinction between sociometric and peer-perceived popularity. Researchers used traditional sociometric methods to obtain student nominations of "liked most" and "liked least" peers (see Coie et al., 1982). Perceived popularity, on the other hand was assessed by asking adolescents to nominate up to three classmates they considered popular. The term "popular" was not defined by researchers and consequently, students relied on their own conceptions of popularity in making nominations. Subsequent findings showed that the behaviors linked with perceived popularity (e.g., dominant, stuck-up) differed from those consistently documented in the child development literature by sociometric methods (e.g., kind, trustworthy). In an attempt to understand how these seemingly distinct dimensions of peer regard might vary by the social status and gender of the perceiver, LaFontana and Cillessen (1999) examined fourth and fifth graders' perceptions of sociometric and perceived popular peers as a function of their own social status and gender. Although, with regard to sociometric classifications, it was demonstrated that children typically liked peers with similar social status and disliked youth from other status groups, such links were much stronger when perceived popularity was considered. Findings led researchers to speculate that further understanding of the correlates of perceived popularity would likely be critical in understanding children's social experiences. In very recent years, research has further contributed to our understanding of not only the distinctions between sociometric and peer-perceived popularity (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002; Lease, Kennedy, & Axelrod, 2002), but also the unique correlates associated with these two high peer status dimensions (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002; Lease et al., 2002; Rodkin, Farmer, Pearl, & Van Acker, 2000; Rose, Swenson, & Waller, 2004).

Despite this nascent research, however, almost no studies have explored contextual correlates of positive peer regard across economically and ethnically diverse contexts. Traditionally, links between rebellious behaviors and peer approval have been viewed as occurring chiefly among economically disadvantaged youth, reflecting their marginalization from mainstream society (Hammond & Yung, 1993); studies have shown that low-income, ethnic minority boys are more likely than other groups of adolescents to be considered popular and antisocial (Luthar & McMahon, 1996; Rodkin et al., 2000). On the contrary, relatively little is known about peers' reactions to different types of negative behaviors in more affluent settings. Given this gap, it is the goal of this study to further understand how students' gender, economic, and racial/ethnic background may moderate the contextual correlates of positive peer regard.

THE VALUE PLACED ON REBELLIOUS BEHAVIORS

Several researchers have noted that behaviors included in the "problem behavior syndrome" (Jessor, 1998)—aggression, delinquency, and low effort at school—provide access into prestigious groups of peers within low-income contexts. Subcultural forces characteristic of poverty stricken communities, such as crime and violence (Coie & Jacobs, 1993; Luthar, 1999) likely influence the peer group's endorsement of both physical aggression and delinquent behaviors. At the same time, perceived job ceilings and experiences of discrimination can cause many of these students to develop "oppositional identities" toward education and effort at school (see Ogbu, 1986).

In recent years, however, there have been increasing suggestions that peers' approval of antisocial behaviors may represent an adolescent phenomenon, and not solely an economic (Brown, 1990; Moffitt, 1993). During the middle school years in particular, rebellious leaders incur much social influence, as other adolescents are drawn to those "antiestablishment" peer leaders who have the "gumption to buck the system" (Luthar, 1997). Indeed, recently, Cillessen and Mayeux's (2004) 5-year longitudinal study (beginning when children were in the fifth grade) showed differential effects by age on links between physical and relational aggression and social status. Over the course of the middle school years, not only did physical aggression become less aversive in terms of peer acceptance, but relational aggression became increasingly predictive of perceived social prominence, with this link especially true for girls. Such findings corroborated those of other studies with similar age groups showing a strong relationship between being perceived as popular and being considered "mean" (among girls) (Merten, 1997), intimidating, and manipulative (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002).

Still others have noted that it can be overly simplistic to suggest that all rebellious behaviors have an "absolute" positive (or negative) value, for as some researchers have noted, adolescents' approval of different types of rebellious behaviors may vary depending on norms within their own immediate subcultures (Chen, Chang, & He, 2003; Stormshak, Bierman, Bruschi, Dodge, & Coie, 1999). Research in affluent suburban communities, for example, are consistent with such suggestions for the context specificity of peer values, as substance use, a form of adolescent rebellion particularly common in this setting, has been linked with high peer acceptance among these teens. In a study of over 250 tenth graders Luthar and D'Avanzo (1999) found that high substance use was linked with peer acceptance for affluent suburban students, but not for their low socioeconomic status (SES), innercity counterparts. These links were particularly robust among suburban males, remaining statistically significant even after controlling for potential confounds in multivariate analyses (see also Luthar & Becker, 2001).

Other studies demonstrate that gender plays a role as well (see e.g., Benenson, Apostoleris, & Parnass, 1998; LaFontana & Cillessen, 1999), and it has been suggested that due to gender role socialization, peers react differently to rebellious behaviors displayed by boys as opposed to girls (Adler & Adler, 1998; Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004). Although past research has posited adolescent boys as generally valuing deviant behaviors more so than adolescent girls (e.g., Goodenow & Grady, 1995), recent research challenges such notions, showing girls, more so than boys, to associate popularity with rebellious behavior (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002; Rose et al., 2004), and to conceive of popularity as a function of social dominance, rather than social preference or likeability (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002; Merten, 1997).

Finally, despite few studies examining attributes associated with peer regard among ethnically diverse groups of adolescents, those that do exist have shown paradoxical findings. Some research, has depicted African-American boys as being more likely than their White peers to be considered popular and antisocial (Luthar & McMahon, 1996; Rodkin et al., 2000). Other studies have shown African-American and Latino youth (particularly boys) as receiving less support for academic success than their White counterparts (Kennedy, 1996; Steinberg, Dornbusch, & Brown, 1992). In contrast, research has also shown that despite often sharing similarly disadvantaged backgrounds (Matute-Bianchi, 1991) and low levels of achievement (Whitworth & Barrientos, 1990) with their African-American peers, Latino students do not evidence comparable disregard for academic application (Osborne, 1997). Further complicating interpretation of extant research, many studies confound ethnicity with SES, precluding distinctions between racial/ethnic and socioeconomic influences (McLoyd, 1998). Thus, given not only that the present study included a diverse sample of African-American, Latino, and White adolescents, but also that these youth were all from an urban, poverty stricken community, it presented a unique opportunity to explore correlates of peer regard among these subgroups of youth, and to address inconsistencies in the research regarding correlates of positive peer regard demographically diverse groups of adolescents. For these analyses, contrast codes were created to explore whether variability on the attributes associated with positive peer regard (particularly regarding academic disengagement) might be observed between (a) ethnic minority youth and their White counterparts and (b) African-American and Latino adolescents.

THE VALUE PLACED ON ACADEMIC APPLICATION

Just as some have argued for a relationship between academic disengagement and high peer status among low-income students (Fordham & Ogbu, 1986; Matute-Bianchi, 1991), it has also been suggested that academic effort and achievement can jeopardize popularity in these settings (MacLeod, 1991). For example, in Luthar's (1995) prospective study of innercity ninth graders, students who were popular in the beginning of the year showed significant declines in their grades over time, suggesting that for low-income youth, repudiating the values of mainstream society (particularly the culture of the school) is one factor likely related to lowered achievement trajectories. This relationship may be particularly true for African-American boys, who have been shown to assume the role of class clown in order to mask their academic accomplishments and maintain positive peer approval (see Fordham & Ogbu, 1986).

On the other hand, in the affluent suburban context, one might expect academic application to promote peer acceptance given the pervasive emphasis on children's high achievement in such communities (Luthar & Becker, 2001; Luthar & D'Avanzo, 1999; Luthar & Sexton, 2004). Research conducted with predominantly Caucasian, middle class samples has shown sociometric popularity to be linked with academic endeavors (see Wentzel, 1998). However, some researchers argue that regardless of sociocultural status, American adolescents in general do not value hard work in school (Moffitt, 1993; Steinberg, 1987). Brown's (1990) research, for example, showed that most Caucasian students avoided ostracism and the negative implications associated with being labeled a "brain" by hiding their academic accomplishments from friends.

THE VALUE PLACED ON PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS AND ATHLETIC ABILITY

Universally agreed upon in the literature is the prominent role played by physical attractiveness and athletic ability in relation to peer status among adolescents from diverse backgrounds (Adler & Adler, 1998; Brown, 1990; Kennedy, 1990; LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002). Students considered attractive have been shown to be significantly more popular than their less attractive peers (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002), regardless of academic success (Boyatzis, Baloff, & Durieux, 1998). Similarly, studies have documented the link between high peer status and athletic ability (Adler & Adler, 1998; LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002). For boys in particular, athletic ability appears not only to distinguish perceptions of popular from unpopular peers, but also to provide entry into socially prominent peer groups (see Crosnoe, 2000).

SUMMARY OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS

To further understand how the social value of behaviors may vary by context, gender, and race/ethnicity, the goal of this study was to explore factors associated with two dimensions of positive peer regard—peer-perceived admiration and social preference—among early adolescents from highly disparate sociodemographic settings. Social preference was the number of "liked most" peer nominations minus the number of "liked least" nominations. Peer admiration was operationalized by peer ratings on "admire," "respect," and "want to be like." Based on prior research showing that adolescents' perceived peer popularity overlaps highly with peer sentiments of admiration, respect, and envy (Dong, Weisfeld, Boardway, & Shen, 1996; Weisfeld et al., 1983, 1984), we theorized that in both contexts, attributes associated with peer-perceived admiration would not only be analogous to those previously reported for peer-perceived popularity but also distinct from social preference.

We examined three sets of constructs as predictors of peer regard, all previously shown to be linked with social status: rebellious,1 problem behaviors (physical aggression, academic disengagement, delinquency, and substance use), academic application (effort at school and good grades), and physical attributes (attractiveness and athletic ability) were examined. Expectations were that peers' approval of particular behaviors would show different connotations for positive peer regard depending on both their relative frequencies in the setting concerned, and on socially prominent peer-group attitudes. With regard to rebellious behaviors we expected aggression (physical/bullying behaviors), delinquency, and academic disengagement to be associated with peer admiration among urban youth (with this especially true among ethnic minority adolescents). In the suburban context, we expected that (a) aggression would be linked with high peer admiration but low social preference (b) among boys, substance use would be linked with high peer admiration and also with high social preference (as seen in other cohorts of affluent, suburban boys) (Luthar & Becker, 2001; Luthar & D'Avanzo, 1999); and (c) academic application would be positively associated with social preference, with converse links for academic disengagement. Finally, being considered attractive (especially among girls) and athletically skilled (especially boys) were hypothesized to be linked with the two dimensions of positive peer regard in both contexts.

METHOD

Participants

This study is part of a larger investigation of risk and resilience among youth at the socioeconomic extremes (Luthar & Latendresse, 2002; Luthar & Sexton, 2004). The sample included 636 seventh-graders attending middle schools in the Northeast. Three-hundred and fourteen of these students (145 female and 169 male) were from an affluent suburban school and 322 (162 female and 160 male) were from a low-income urban school. The mean age of the sample of suburban students was 12.58 years (SD = .53) and for the urban students was 12.48 years (SD = .79). Ninety-four percent of the suburban students were Caucasian, and 6% were ethnic minority (2% African American, 1.0% Latino, 2.3% Asian, and .7% Biracial). Among urban students, 20.7% were Caucasian and 79.3% were ethnic minority (31% African American, 46.1% Latino, .8% Asian, and 5.7% Biracial).

The two schools differed sharply in family socioeconomic status. At the time of data collection, the median income in the suburban town was well over $120,000 (Connecticut Department of Housing, 1999). This is more than three times greater than the median income in the urban setting, which was $28,243 (Bureau of the Census: American Community Survey, 1999). Percentages of students receiving free or reduced lunches in the suburban and urban schools respectively were 3% and 84.4%.

The 314 students in the suburban school represented 91.7% of the entire cohort of students who were in the seventh grade of that town during the spring of 2000. Of the 26 students who did not participate, 18 did so because of a lack of parental permission, three because they did not wish to complete the questionnaires and five because they were absent on both days of data collection.

Complete data were obtained for 90.7% of the 322 students in the urban school. Of the 33 students who were not included in this study, two were excluded because of a lack of parental permission, five because they did not wish to participate in the study, and 26 because they were absent on both days of data collection.

Measures

Peer nominations

A sociometric questionnaire was used to assess positive peer regard and the associated child attributes. For both peer status and student attribute nominations, students were told that the same classmates could be chosen for more than one role and that they could nominate classmates of either gender, however, self-nominations were not permitted. For peer status, students were asked to nominate up to three individuals from their English classes (names of students whose parents declined their participation in this study were not included in class rosters) whom they liked most and three they liked least as in the sociometric procedures devised by Coie et al. (1982). Liked-most and liked-least nominations received by each participant were summed and standardized by class.

There are two methods commonly used to identify students considered well liked by peers from sociometric data. The more straightforward method involves simply summing and standardizing all "liked most" nominations. The second denotes social preference and involves subtraction of standardized scores of peer dislike from peer liking, correcting for the fact that some students who are nominated as being liked are also often nominated as being disliked. In this study, social preference scores were computed and were employed to represent relative likeability.2

A sociometric questionnaire was also used to assess peer-perceived admiration (someone who is admired; is respected; others want to be like), as well as academic disengagement (someone who does not work hard; does not follow school rules; does not get good grades); academic application (someone who works hard; follows school rules; gets good grades); athletic ability (someone who is a good athlete); and physical attractiveness, (someone who is good looking). Physically aggressive/bullying behaviors were assessed by four items drawn from another measure of behavioral reputation administered in this study, the Revised Class Play (RCP, Masten, Morison, & Pellegrini, 1985). The four items in question were chosen because they have consistently loaded among the most strongly on the aggressive–disruptive subscale of this measure (Luthar, 1995; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998): someone who gets into a lot of fights, loses temper easily, picks on other kids, teases other kids.

As with sociometric nominations, students were allowed to nominate up to three individuals from their English classes. For each of these peer-nominated dimensions, the total number of nominations was standardized by class in order to account for variance in class sizes. Acceptable psychometric properties for such procedures have been widely reported (Graham, Taylor, & Hudley, 1998; Luthar & D'Avanzo, 1999; Masten et al., 1985). Alpha coefficients among suburban and urban students, respectively, were as follows for the various dimensions: Admiration, .93 and .86; academic disengagement, .93 and .73; academic application, .88 and .87; and physical aggression, .88 and .87. No coefficient was available for athletic ability or physical attractiveness as they were assessed by a single item. However, of note, because peer nominations are derived from all participating adolescents' responses, with students permitted to nominate up to three peers per item, the typical problems associated with single-item measures (e.g., low reliability/validity) are not considered problematic, and many existing studies have used similar single-item nominations methods (e.g., see Gest, Graham-Bermann, & Hartup, 2001; Graham et al., 1998; LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002).

Delinquency

This was assessed by the Self-Report Delinquency Checklist (SRD) (Elliot, Dunford, & Huizinga, 1987), an instrument that includes 37 items rated on a four-point scale that ask about the frequency of delinquent acts at home, at school, and in the community. The SRD is a reliable and valid instrument (Elliot, Huizinga, & Menard, 1989). In order to avoid redundancy in examining statistical associations with substance use, six items on the SRD pertaining to substance use (e.g., "used alcohol") were removed from the total delinquency score (see also Luthar & Becker, 2001; Luthar & D'Avanzo, 1999). Alpha coefficients of the resultant SRD scores were .92 and .89 for youth from suburban and urban contexts, respectively.

Substance use

Adolescents' substance use was assessed via self-reports of the frequency of drug use questions in the Monitoring the Future Study Survey (Johnston, Bachman, & O'Malley, 1989). This measure probes students about the frequency of use of individual substances over the past year. Ratings are obtained on a seven-point scale ("never" to "40+times"). The reliability and validity of this measure have been amply documented (Wallace & Bachman, 1991; Winters, Weller, & Meland, 1993). A mean score composite index of past-year frequency scores of cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use was created (see also Luthar & Becker, 2001; Luthar & D'Avanzo, 1999). Alpha coefficients in this sample had adequate reliability among suburban and urban youth .77 and .79, respectively.

Academic grades

As per the permission of the school (and stated in the permission forms), grades were obtained from all students' records whose parents did not decline their participation. Cumulative grade-point averages (GPA) were computed based on students' grades from the previous three quarters of the school year in four classes (English, Social Studies, Science, and Math), with standardized grade scores used as indices of achievement. Letter grades were coded such that A+ was assigned a score of 13 and an F a score of 1.

Procedure

Students' inclusion in the sample was based on passive consent procedures, as data collection was a part of a school-based initiative on positive youth development in both schools. Letters were mailed home to parents of all seventh grade students, describing the project, indicating that survey results would be presented only in aggregate form, and requesting notification from parents who wished that their children not participate. Data were collected on 2 separate days, during English class periods. In order to ensure that reading capacities did not influence the data, a member of the research team read each questionnaire aloud, with students marking their responses accordingly. Two research team members were also present in the classroom to attend to students' questions. The protocols were administered in the same order to all students. Once participation in the study was complete, a gift of money to support a pizza party and of mechanical pencils was given to all participating students in the suburban and urban schools, respectively (as per the request of school administrators).

RESULTS

Overview and Analysis Plan

Considering our overarching goal to examine contextual correlates of two dimensions of positive peer regard, hierarchical regressions were run, examining predictors of: (1) peer-perceived admiration, and (2) social preference, with the two contexts combined in a single analysis. In these analyses, gender, race/ethnicity, and context were controlled for at the outset. In order to attain a more accurate understanding of the unique relationship between student attributes and each of the dimensions of positive peer regard, the positive peer regard dimension that was not the criterion was entered in Step 2. Student attributes were entered in Step 3, allowing for an evaluation of the unique explanatory power of student traits and behaviors as predictors of positive peer regard.

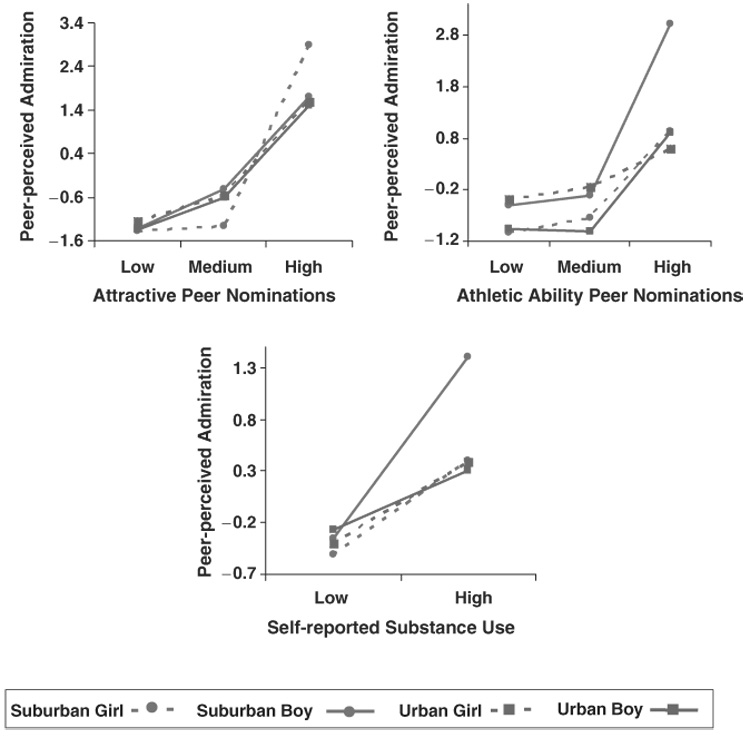

To explore expectations that context (affluent suburban versus low-income urban) might moderate relations between student attributes and positive peer regard, two-way interaction terms were considered in Step 4. Finally, in Step 5, three-way interactions were entered, in order to assess whether the moderating role of gender was context specific (e.g., Context × Gender × Attribute). The two- and three-way interaction terms were entered in the last two steps in order to determine their unique contribution to variance accounted for, after the main effects had already been entered. As recommended by Aiken and West (1991), the predictors were centered before running the analyses, in order to avoid problems of multicollinearity. To aid interpretation of these effects, a graph was created for each interaction (see Figure 1 and Figure 2), with regression slopes depicting associations between the predictor and peer status dimension at low (M–1 SD), medium (M), and high (M+1 SD) levels of the moderator (see Jaccard, Turrisi, & Wan, 1990).

FIGURE 1.

Interactions between context, gender, and student attributes in predicting positive peer regard.

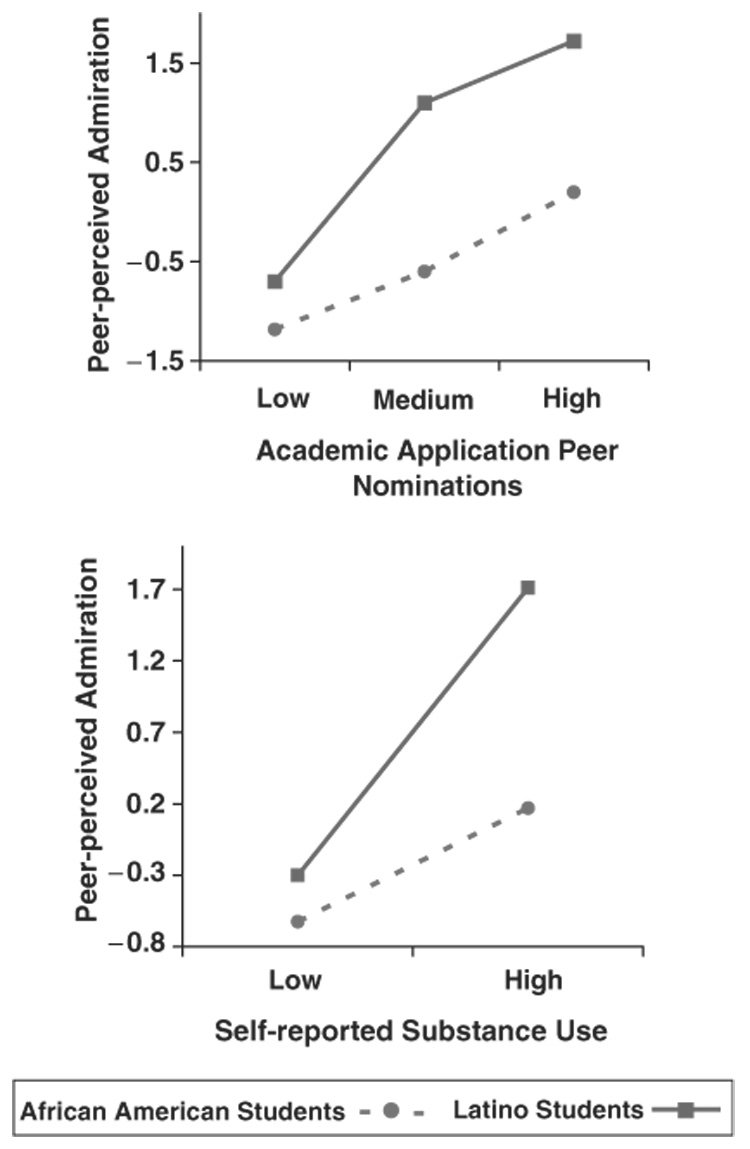

FIGURE 2.

Interactions between race/ethnicity and student attributes in predicting urban students' positive peer regard.

With regard to analyses exploring possible race/ethnicity differences in the urban context, contrast comparisons were created for the three racial/ethnic groups and were entered in lieu of context interactions in Step 4. These groups included White students contrasted with ethnic minority students (White/minority) and African-American students contrasted with Latino students (AA/Latino).3

Correlations between Student Attributes and Positive Peer Regard

Simple correlations among all of the variables are depicted in Table 1, with girls presented in the top row, and those for boys underneath; values for suburban students are depicted below the diagonal. For the most part, the traits and behaviors associated with positive peer regard in the two contexts were more similar than different. Peer-perceived admiration was associated with both rebellious and achievement oriented behaviors, while the traits and behaviors linked with social preference were generally more prosocial. There were modest correlations between perceived admiration and social preference (r's of .41–.51, p<.01).

TABLE 1.

Correlations among Positive Peer Regard and Student Attributes: Suburban and Urban Context

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Race/ethnicitya | −.03 | .08 | .16* | .10 | −.10 | −.15 | −.01 | −.09 | .01 | .01 | |

| −.15 | −.13 | .11 | .10 | −.06 | −.16* | −.11 | −.04 | −.15 | −.15 | |||

| 2 | Perceived admiration | .10 | .50*** | .04 | .26*** | .22** | .26*** | .47*** | −.12 | .74*** | .15 | |

| −.02 | .41*** | .22** | .45*** | .35*** | .48*** | .14 | .05 | .75*** | .72*** | |||

| 3 | Social preference | .23** | .51*** | .07 | .09 | .03 | −.07 | .30*** | −.05 | .64*** | .27*** | |

| .14 | .44*** | .09 | .15 | −.10 | −.01 | .08 | .01 | .49*** | .38*** | |||

| 4 | Grades | .19* | .07 | .21** | .44*** | −.28*** | −.28*** | −.24** | −.01 | −.06 | .07 | |

| .30*** | .03 | .18* | .45*** | −.28*** | −.17* | −.02 | .02 | .09 | .04 | |||

| 5 | Academic application | .13 | .17* | .33*** | .60*** | −.16* | −.21** | −.14 | −.04 | .02 | .11 | |

| .09 | .15* | .28*** | .47*** | −.19* | −.16* | −.10 | .09 | .17* | .09 | |||

| 6 | Academic disengagement | −.31*** | −.01 | −.36*** | −.51*** | −.36*** | .47*** | .27*** | −.00 | .29*** | .14 | |

| −.33*** | .18* | −.22** | −.55*** | −.36*** | .71*** | .13 | .21* | .37*** | .45*** | |||

| 7 | Physical aggression | −.17* | .22** | −.29*** | −.13 | −.19* | .38*** | .28*** | −.05 | .22** | .14 | |

| −.35*** | .11 | −.43*** | −.40*** | −.37*** | .74*** | .18* | .00 | .46*** | .63*** | |||

| 8 | Substance use | −.12 | .34*** | .02 | −.07 | −.08 | .01 | .18* | −.05 | .43*** | −.00 | |

| −.15 | .14 | −.03 | −.21** | −.17* | .31*** | .28*** | −.04 | .63*** | .12 | |||

| 9 | Delinquency | −.03 | .06 | −.08 | .05 | −.13 | −.04 | .01 | .10 | −.11 | .07 | |

| −.07 | .06 | .01 | −.03 | −.11 | .05 | .03 | .07 | −.04 | .02 | |||

| 10 | Physical attractiveness | .15 | .87*** | .46*** | .09 | .19* | −.06 | .17* | .38*** | .08 | .30*** | |

| −.07 | .78*** | .42*** | .12 | .20** | .02 | .04 | .06 | .04 | .72*** | |||

| 11 | Athletic ability | .05 | .38*** | .31*** | .14 | .19* | −.09 | .04 | −.03 | −.08 | .23** | |

| −.06 | .59*** | .35*** | .02 | −.02 | .23** | .21** | .17* | .08 | .53*** |

White = 1, ethnic minority = 0.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Note. Correlations for youth from the low-income context are presented in the top half of the diagonal (affluent context correlations in the bottom half), with coefficients for girls listed in the top row and boys underneath.

Contextual Correlates of Positive Peer Regard: Hierarchical Multiple Regressions

Results of regression analyses are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3. For each step both the increment in R² change and standardized βs are indicated; unstandardized regression coefficients are listed for interaction terms (see Aiken & West, 1991). The full model accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance in the dimensions of positive peer regard among all adolescents (74% of the variance for peer-perceived admiration and 48% of the variance for social preference).

TABLE 2.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Contextual Correlates of Two Dimensions of Positive Peer Regard Among Suburban and Urban Adolescents

|

Perceived Admiration |

Social Preference |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | β | r² | β | r² | |||

| Demographics | 1 | .01 | .01 | ||||

| Gendera | .01 | .00 | .01 | .00 | |||

| Race/ethnicityb | −.06 | .00 | .08 | .00 | |||

| School | .05 | .00 | .17 | .00 | |||

| Peer regard | 2 | .24*** | .24*** | ||||

| Positive peer regardc | .16 | .02*** | .30 | .03*** | |||

| Student attributes | 3 | .43*** | .18*** | ||||

| Grades | .01 | .00 | −.05 | .00 | |||

| Academic application | .17 | .02*** | .01 | .00 | |||

| Academic disengagement | .06 | .00 | −.09 | .00 | |||

| Aggression | .15 | .01** | −.37 | .06*** | |||

| Substance use | −.01 | .00 | .04 | .00 | |||

| Delinquency | .02 | .00 | .00 | .00 | |||

| Athletic ability | .14 | .01** | .19 | .02*** | |||

| Physical attractiveness | .59 | .18*** | .27 | .02*** | |||

| Two-way interactions | 4 | .02 | .02 | ||||

| Three-way interactions | 5 | .04*** | .02 | ||||

| Gender × context × academic application | |||||||

| Substance Use | .08 | .01* | |||||

| Athletic Ability | −.42 | .02** | |||||

| Physical Attractiveness | .10 | .02* | |||||

| Total R² | .74*** | .48*** | |||||

Girl=1, boy=0.

White=1, ethnic minority=0.

This variable is the dimension of positive peer regard not being considered as an outcome.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Note. As recommended by Aiken and West (1991), (a) interaction terms in these analyses involve centered variables, (b) β values for main effects are standardized, and (c) β values for interaction effects are unstandardized. Only those interactions that showed significant effects in one or both analyses are presented.

TABLE 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Predicting Two Dimensions of Positive Peer Regard: Race/ethnicity Comparisons Among Urban Students

|

Perceived Admiration |

Social Preference |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | β | r² | β | R² | |||

| Demographics | 1 | .05** | .01 | ||||

| Gendera | −.03 | .00 | −.04 | .00 | |||

| White/ethnic minorityb | −.17 | .00 | .04 | .00 | |||

| AA/Lationc | −.01 | .00 | .11 | .00 | |||

| Peer regard | 2 | .26*** | .27*** | ||||

| Positive peer regardd | .14 | .02*** | .29 | .02** | |||

| Student attributes | 3 | .44*** | .22*** | ||||

| Grades | .04 | .00 | −.02 | .00 | |||

| Academic application | .29 | .10*** | −.09 | .00 | |||

| Academic disengagement | .05 | .01 | −.14 | .01 | |||

| Physical aggression | .22 | .01* | −.29 | .03*** | |||

| Substance use | .04 | .00 | .04 | .00 | |||

| Delinquency | .01 | .00 | −.00 | .00 | |||

| Athletic ability | .16 | .02* | .13 | .00 | |||

| Physical attractiveness | .41 | .05*** | .49 | .08*** | |||

| Two-way interactions | 4 | .01 | .01 | ||||

| Three-way interactions | 5 | .03** | .01 | ||||

| AA/latino academic application | −.11 | .02** | |||||

| Substance Use | −.11 | .01* | |||||

| Athletic Ability | |||||||

| Physical Attractiveness | |||||||

| Total R² | .79*** | .52*** | |||||

Girl=1, boy=0.

White=1, ethnic minority=0.

African American=1, Latino=0.

This variable is the dimension of positive peer regard not being considered as an outcome.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Note. As recommended by Aiken and West (1991), (a) interaction terms in these analyses involve centered variables, (b) β-values for main effects are standardized, and (c) β-values for interaction effects are unstandardized. Only those interactions that showed significant effects in one or both analyses are presented.

With regard to peer-perceived admiration, gender and race/ethnicity were not unique predictors. Social preference was a significant predictor, after controlling for the effects of gender, race/ethnicity and school. The block of student attributes achieved statistical significance, and Table 2 depicts the attributes that uniquely contributed to peer-perceived admiration, having considered variance shared with all other predictors in the equation. As expected, peer-perceived admiration was associated with physical aggression, physical appearance, and athletic ability. Unexpectedly, results also showed academic application to be a unique predictor.

Interaction terms in the regression analyses were examined individually only if the block as a whole yielded a statistically significant increase in R² change. No significant effects were indicated for the two-way interactions examining context as a moderator of student attributes. However, three-way interactions exploring whether the moderating role of gender was context specific revealed three significant effects (see Figure 1). Although among all students, physical attractiveness was linked with perceived admiration, among suburban girls, links were especially strong, as suburban girls with high levels of perceived attractiveness received increased scores for perceived admiration. Unlike girls and urban boys, suburban boys stood out from the other three groups in terms of having exceptionally high peer admiration associated with (a) high substance use and (b) high athleticism.

As with peer-perceived admiration, gender and race/ethnicity were not unique predictors of social preference. Perceived admiration, however, was a significant predictor, after controlling for the effects of gender, race/ethnicity, and school. As hypothesized, physical attributes (attractiveness and athletic ability) were significant predictors. Negative links were also revealed for aggression. There were no significant interaction effects for social preference.

Moderation by Race/Ethnicity: Urban Context

Given the study hypotheses of potential differences among the racial/ethnic groups in the urban sample, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were rerun within the urban context. In these analyses, the planned orthogonal contrasts were entered in lieu of race/ethnicity and with gender, were controlled for at the outset; of central interest were interaction effects involving these contrast terms and the major predictors. Results of these regression analyses are summarized in Table 3. Although these analyses were performed solely within the urban context, for the most part, main effect findings were comparable with those depicted in Table 2. Peer-perceived admiration showed positive links with rebellious (physical aggression) and prosocial (academic application) behaviors, as well as with physical attributes (physical attractiveness and athletic ability). Social preference showed negative associations with physical aggression and positive links with attractiveness. Two significant interaction effects were also indicated; both with regard to peer-perceived admiration (see Figure 2). In terms of rebellious behaviors, for Latino youth, more so than for African-American youth, high levels of self-reported substance use were linked with increased peer admiration. Academic application also appeared particularly salient for Latino students in comparison with their African-American peers, as peer admiration was unusually high for those Latino students with high scores for academic application.

DISCUSSION

Our results showed that within each of these contexts—at the two extremes of socioeconomic status—attributes linked with peer-perceived admiration were not only comparable with those documented in past studies for peer-perceived popularity, but were also distinct from social preference. Moreover, there were more similarities than differences in the contextual correlates of peer-perceived admiration and social preference. In accordance with past research (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002), all adolescents were admiring of classmates who showed some physical aggression and at the same time, showed lowered social preference for peers exhibiting aggressive behavior. In the suburban context, peer-perceived admiration was also associated with substance use among boys; similar links were observed in the urban context for Latino youth. Contrary to widespread stereotypes that youth from economically disadvantaged environments look down upon their academically committed peers, all seventh graders in this study, regardless of economic background, expressed strong admiration for academic application (with this particularly true in the urban context for Latino youth). Finally, in both settings, peer-perceived admiration and social preference were associated with physical attractiveness (especially true for suburban girls) and athletic ability (particularly true for suburban boys). The major findings are discussed in turn.

Distinctions Among Two Dimensions of Positive Peer Regard

The two dimensions of positive peer regard—peer-perceived admiration and social preference—were only modestly correlated, and for the most part, appeared linked to distinct behaviors (for similar findings see Gest et al., 2001). Consistent with hypotheses, peer-perceived admiration generally included negative attributes as well as positive ones. By contrast, social preference was associated with positive attributes in both contexts. It should be noted in interpreting these findings that by controlling for the effects of the peer dimension not under consideration, analyses yielded a more stringent measure of the unique relationship between student attributes and each of the two dimensions of positive peer regard. Thus, significant links with each dimension of peer regard portray those that are specific only to that dimension, having removed any overlap between the two.

Our findings extend extant evidence on the heterogeneity of positive peer regard by showing that regardless of economic or ethnic background, adolescents emphasize prosocial, positive traits in the people that they like, but tend to admire those who act aggressively (in this case in terms of physical and bullying behaviors) toward others (see Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002). Adolescents in the low-income urban context appeared no more admiring of physically aggressive bullying behaviors than their counterparts at the very top of the socioeconomic ladder.

That said, we note that our data did not capture some fine-grained distinctions such as those between physical and relational aggression. Although these two dimensions tend to be highly correlated among early adolescents (e.g., Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002). Rose et al. (2004) found that relational but not physical aggression was instrumental in adolescent girls' ability to manipulate peers in ways that bolstered perceived popularity. Future research is needed to further examine longitudinal relations between physical and relational aggression and peer admiration among youth from different demographic and gender groups.

It is important to underscore that findings showing peer admiration of physical aggression in both contexts do not necessarily connote similar long-term risks. Among suburban youth—who tend to have various safety nets available to them including adults strongly urging behavioral conformity (Bradley & Corwyn, 2003; Luthar & Burack, 2000)—occasional episodes of deviance may be largely dissipated by early adulthood. The odds however, that youth in chronic poverty will benefit from similar safeguards are far lower (Gest et al., 2001; Luthar, 1999). Thus, it is plausible that although rebellious behaviors may lose their social value over time (Moffitt, 1993), other maladaptive contextual forces may come to sustain rebellious behaviors among certain groups of adolescents (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004).

Our findings substantiate suggestions (e.g., Stormshak et al., 1999) that all rebellious behaviors do not have an "absolute" positive value among adolescents in general. In fact, some rebellious behaviors were especially salient among particular ethnic and gender groups within the urban and suburban contexts, respectively. Among urban Latino students in comparison with their African-American peers, for example, substance use showed stronger links with peer admiration. Future research is needed on the specific forms of illegal substances that elicit peer admiration, and how these may vary across different gender, age, and ethnic groups.

In the suburban setting, substance use was linked with peer admiration among boys but not with social preference. The latter findings are at odds with those documented in two other cohorts of suburban adolescents, one of 10th graders (Luthar & D'Avanzo, 1999), and the other of seventh graders (Luthar & Becker, 2001). Differences in findings might derive from varying operational definitions of peer status. In the two previously mentioned studies (Luthar & Becker, 2001; Luthar & D'Avanzo, 1999), calculations summed all "liked most" nominations whereas in this investigation, social preference corrected for the fact that some students who are nominated as liked are also often nominated as being disliked (i.e., "disliked" nominations were subtracted from "liked most"). Moreover, controlling for the effects of peer admiration in predicting social preference in effect, removed the "admired" parts of social preference, which may have also attenuated the previously documented links between suburban boys' substance use and social preference.

Despite these differences, peers' approval of suburban boys' substance use is of concern from an applied standpoint because the previously mentioned safety nets for affluent suburban youth could be less successful in curtailing substance use, due to its being more easily concealed than, say, rebelliousness at school. Moreover, the illegal substances assessed in this study (alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana) are considered by many researchers to be "gateway" drugs, often preceding harder illicit drug use such as cocaine and heroin (Botvin et al., 2000).

As our findings show some unsettling yet expected correlates of peer admiration in both contexts, they also show some unexpectedly positive trends; this is particularly true in relation to urban peers' attitudes to academic effort. Based on some prior research (e.g., Fordham & Ogbu, 1986; Graham et al., 1998; Luthar, 1995), we had originally anticipated that students who worked hard at school would have low social preference among urban youth but high social preference in the suburban context. However, our results showed that all students strongly admired good students—with 10% of variance explained—and within the urban context, lower social preference scores were indicated for peers viewed as academically disengaged. In recent years, there have been other findings consistent with these. To illustrate, in a sample of over 17,000 tenth graders, Cook and Ludwig (1998) demonstrated that high achieving low-income ethnic minority 10th graders were no more likely to be considered unpopular than other students. In other research, Ainsworth-Barnell and Downey (1998) reported that relative to White students, African-American students were more likely to be perceived as popular when considered to be very good students (see also Spencer, Noll, Stoltzfus, & Harpalani, 2001).

These findings suggest the need for more comprehensive inquiry into the achievement-related attitudes of different ethnic minority groups, appraising variations by both immigrant status and developmental shifts over time. In this study, seventh graders' perceptions of peers as good students, relative to their perceived admiration, were particularly beneficial for urban Latino youth in comparison with their African-American peers. Recent studies show that differences in achievement attitudes exist between ethnic minority adolescents from immigrant families and those who have resided in the United States for two or more generations (for a review see Zhou, 1997), with recent Latino immigrants receiving higher academic scores and reporting stronger endorsement of achievement values than their American-born counterparts (Fuligini, 1997). Considering that no information was obtained regarding the immigrant or generational status of Latino youth in this study, differential associations for the value of academic commitment among African-American and Hispanic students must be interpreted with caution. Moreover, research has shown that during the middle school years, adolescents become increasingly aware of, and susceptible to, existing racial/ethnic group stereotypes (Aronson & Good, 2003). Stereotypes regarding lowered academic capacity among African-American (Steele & Aronson, 1995), and to some degree Latino students (Aronson, Quinn, & Spencer, 1998) have been linked with inferior achievement performance among these students, in situations that elicit such stereotypes (Steele & Aronson, 1995).

Finally, as expected, being considered attractive and athletic by peers were strongly related to both dimensions of peer regard, with links particularly salient among suburban girls and boys, respectively. Indeed, findings for the significant value of suburban girls' attractiveness were rather unsettling. This variable alone explained 18% of variance in scores of peers' admiration, and the average admiration score of suburban girls rated as attractive was almost two and a half standard deviations from the group mean. Considering the powerful influence physical attractiveness appears to have on suburban girls' peer-admiration, it is of little surprise that girls in affluent, mostly Caucasian families are as intensely preoccupied with body image and appearance as they are reputed to be (see Franko & Striegel-Moore, 2002).

Links between athletic ability and admiration among suburban boys are consistent with Crosnoe's (2000) findings of significant respect garnered by athletic skills among White, suburban, middle school youth. Such patterns may reflect the high visibility of talented athletes in upper-class communities. During the middle school years, a large proportion of teens from affluent, suburban settings play on sports teams. Thus, a sizable number of children (and their parents) attending these games are well aware of which students are athletically talented. Similarly, modest findings for the relation between athletic ability and perceived admiration and the nonsignificant link with social preference in analyses specific to the urban context may also be understood in terms of contextual factors, reflecting lack of opportunities for athletic participation in low-income communities (see Elkins, Cohen, Koralewicz, & Taylor, 2004).

Two variables were nonsignificant in all of our analyses: academic grades and delinquency. With regard to grades, it appears that among all seventh graders, impressions of academic application are linked with peer admiration more so than actual grades (to which the wider peer group is not necessarily privy; for comparable findings see Luthar & McMahon, 1996). The nonsignificance of delinquency in multivariate analyses (despite good reliability) might derive from the high variance shared with other rebellious behaviors that are less serious and more common, such as academic disengagement, physical aggression, and occasional substance use. Such behaviors, more visible to the peer group, are perhaps more powerful in shaping peers' overall attitudes than their delinquency per se.

Caveats, Limitations, and Implications for Future Work

A major limitation of this study lies in the confounds involving family income with both race/ethnicity and location, as adolescents from the affluent context were mostly White and suburban, while low-income youth were ethnically diverse and urban. In the future, it would be valuable to separate the effects of geographical context, by comparing, for example, adolescents living in high- and low-income urban contexts. Extricating confounds between family income and race/ethnicity however, will not be easy considering contemporary demographic patterns. In order to recruit large enough samples of ethnic minority youth from wealthy families, a large number of school districts will have to be sampled (see also Luthar & Sexton, 2004).

Also relevant to issues of generalizability are developmental considerations. These results demonstrate the salience of student attributes with regard to positive peer regard during one time point: while students were in the seventh grade. Moreover, two of the peer-nominated student attributes (physical attractiveness and athletic ability) were based on single-item assessments. Although the social value of these attributes have been shown to be quite robust over time (Adler & Adler, 1998), future longitudinal research directed at understanding the stability of the underlying traits and behaviors associated with positive peer regard is warranted. For, as previously mentioned, as adolescents mature, they are subject to new influences and values outside of the home, school, and peer context (see Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; Gutman, Sameroff, & Cole, 2003).

Reliance on cross-sectional data also precludes the inference of cause-effect conclusions on student attributes and positive peer regard. It is possible, for example, that high substance use garners high peer admiration among suburban boys, but the opposite causal direction is also possible. As noted by Engels and ter Bogt (2001) adolescents rejected by peers are likely to have fewer opportunities to experiment with illegal substances as such behaviors are typically social.

The fact that nominations were restricted to a maximum of three peers from students' English class placed restrictions on the generalizability of the data. Seventh graders' social relations are not necessarily restricted to classrooms and as recommended by Terry (2000), sociometric studies with middle- and high-school students could benefit by using unlimited-choice methods. Even as we acknowledge these limitations, we note that our past programmatic research has demonstrated good psychometrics for peer ratings using similar procedures in multiple middle- and high-school cohorts (e.g., Luthar, 1995; Luthar & Becker, 2001; Luthar & D'Avanzo, 1999; Luthar & McMahon, 1996). In this study, furthermore, the high correlations among conceptually linked peer-rated dimensions also attest to the validity of scores (e.g., correlations between peer ratings of students with high "academic application" in their English classes, and students' academic grades across all their major subjects, ranged between .44 and .60, see Table 1).

Offsetting these limitations are various strengths, most notable among which is the availability of data on correlates of two distinct dimensions of positive peer regard—peer-perceived admiration and social preference—among adolescents from opposite ends of the economic spectrum. For developmental theory, the findings support Moffitt's views that it is not only youth from poor, innercity contexts that admire "rebellious" behaviors, but ostensibly privileged, wealthy teens as well (Moffitt, 1993). At the same time, the results counter many prevalent stereotypes. Whereas youth from low-income, urban environments do admire some rebellious behaviors, they also clearly admire academic application. Teenagers from wealthy communities, by the same token, are not as risk free as one might assume, for peers can reinforce various undesirable attributes including physical aggression, excessive concern with physical attractiveness (among girls), and substance use (among boys). Considered collectively, our findings underscore the dangers of assuming—without examining—the negative or positive nature of academic peer values in little-studied communities. The findings also carry sobering implications for applied efforts, underscoring the need for parents and practitioners to recognize that across economic and demographic contexts, adolescent peers can be a potent force in socializing youth toward some behaviors that can, in the long run, prove to be counterproductive for their personal health and well-being.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper is based in part on a doctoral dissertation by the first author and was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1-DA10726 and RO1-DA11498, RO1-DA14385), the William T. Grant Foundation, and the Spencer Foundation. We are grateful to B. Bradford Brown and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. A special thank you is also extended to the students, teachers, and schools who participated in this research.

Footnotes

The term rebellious refers to behaviors which contradict mainstream expectations and norms for the developmental stage of adolescence, but not necessarily the norms and expectations of the peer group.

All analyses reported here were rerun with the uncorrected liked-most scores as well (i.e., without subtracting liked-least nominations), and results were identical to those presented.

Parallel analyses within the suburban context were precluded due to the homogeneity of the sample (94% of this sample was White).

Contributor Information

Bronwyn E. Becker, New York University

Suniya S. Luthar, Columbia University

REFERENCES

- Adler PA, Adler L. Peer power: Preadolescent culture and identity. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth-Barnell JW, Downey DB. Assessing the oppositional cultural explanation for racial/ethnic differences in school performance. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:536–553. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J, Good C. The development and consequences of stereotype vulnerability in adolescents. In: Pajares F, Urdan TC, editors. Academic motivation of adolescents. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing; 2003. pp. 299–330. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J, Quinn DM, Spencer SJ. Stereotype threat and the academic underperformance of minorities and women. In: Swim JK, Stangor C, editors. Prejudice: The target's perspective. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Benenson J, Apostoleris N, Parnass J. The organization of children's same-sex peer relationships. In: Bukowski A, Cillessen AHN, editors. Sociometry then and now: Building on six decades of measuring children's experiences with the peer groups (new directions for child development No. 80) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1998. pp. 5–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Scheier LM, Williams C, Epstein JA, et al. Preventing illicit drug use in adolescents: Long-term follow-up data from a randomized control trial of a school population. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:769–774. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis CJ, Baloff P, Durieux C. Effects of perceive attractiveness and academic success on early adolescent peer popularity. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1998;159:337–344. doi: 10.1080/00221329809596155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Age and ethnic variations in family process mediators of SES. In: Bornstein MH, Bradley RH, editors. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Monographs in parenting series. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB. Peer groups and peer cultures. In: Feldman SS, Elliot GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 171–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of the Census: American Community Survey. 1999 from http://factfinder.census.gov/home/en/acsdata.html.

- Chen X, Chang L, He Y. The peer group as a context: Mediating and moderating effects on relations between academic achievement and social functioning in Chinese children. Child Development. 2003;74:710–727. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN, Mayeux L. From censure to reinforcement: Developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development. 2004;75:147–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Jacobs MR. The role of social context in the prevention of conduct disorder. Development & Psychopathology. 1993;5:263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Connecticut Department of Housing. 1999 Retrieved from http://www.state.ct.us/ecd/

- Cook PJ, Ludwig J. The burden of "acting White": Do Black adolescents disparage academic achievement? In: Jencks C, Phillips M, editors. The Black–White test score gap. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute; 1998. pp. 375–400. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R. Friendships in childhood and adolescence: The life course and new directions. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2000;63:377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Q, Weisfeld G, Boardway RH, Shen J. Correlates of social status among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1996;27:476–493. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins WL, Cohen DS, Koralewicz LM, Taylor SN. After school activities, overweight, and obesity among inner city youth. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Dunford FW, Huizinga D. The identification and prediction of career offenders utilizing self-reported and official data. In: Burchard J, Burchard S, editors. Prevention of delinquent behavior. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. pp. 90–121. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Huizinga D, Menard S. Multiple problem youth: Delinquency, substance use, and mental health problems. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Engels RC, ter Bogt T. Influences of risk behaviors on the quality of peer relations in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30:675–695. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham S, Ogbu JU. Black students' school success: "Coping with the burden of acting white". The Urban Review. 1986;18:176–206. [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Striegel-Moore RH. The role of body dissatisfaction as a risk factor for depression in adolescent girls: Are the differences Black and White? Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:975–983. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligini AJ. The academic achievement of adolescents from immigrant families: The roles of family background, attitudes, and behavior. Child Development. 1997;68:351–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gest SD, Graham-Bermann SA, Hartup W. Peer experience: Common and unique features of number of friendships, social network centrality, and sociometric status. Social Development. 2001;10:23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C, Grady KE. The relationship of school belonging and friends' values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. Journal of Experimental Education. 1995;62:60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Juvonen J. Ethnicity, peer harassment, and adjustment in middle school: An exploratory study. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2002;22:173–199. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Taylor AZ, Hudley C. Exploring achievement values among ethnic minority early adolescents. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1998;90:606–620. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Sameroff AJ, Cole R. Academic growth curve trajectories from 1st grade to 12th grade: Effects of multiple social risk factors and preschool child factors. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:777–790. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WR, Yung B. Psychology's role in the public health response to assaultive violence among young African American men. American Psychologist. 1993;94:308–319. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Turrisi R, Wan CK. Interaction effects in multiple regression. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. New York: Cambridge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM. Monitoring the Future: Questionnaire responses from the nation's high school seniors. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy E. Correlates of perceived popularity among peers: A study of race and gender differences among middle school students. Journal of Negro Education. 1996;64:186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy JH. Determinants of peer social status: Contributions of physical appearance, reputation, and behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1990;19:233–243. doi: 10.1007/BF01537889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFontana KM, Cillessen A. Children's perceptions of popular and unpopular peers: A multimethod assessment. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:635–647. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFontana KM, Cillessen HN. Children's interpersonal perceptions as a function of sociometric and peer-perceived popularity. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1999;160:225–242. [Google Scholar]

- Lease AM, Kennedy CA, Axelrod JL. Children's social constructions of popularity. Social Development. 2002;11:87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Social competence in the school setting: Prospective cross-domain associations among inner-city teens. Child Development. 1995;66:416–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Sociodemographic disadvantage and psychosocial adjustment: Perspectives from developmental psychopathology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Poverty and children's adjustment. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Becker BE. Privileged but pressured? A study of affluent youth. Child Development. 2001;73:1593–1610. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Burack JA. Adolescent wellness: In the eye of the beholder? In: Cicchetti D, Rappaport J, Sandler I, Weissberg RP, editors. The promotion of wellness in children and adolescents. Washington, DC: Child Welfare League of America; 2000. pp. 29–57. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, D'Avanzo K. Contextual factors in substance use: A study of suburban and inner-city adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:845–867. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Latendresse SJ. Adolescent risk: The costs of affluence. In: Noam G, Taylor CS, Lerner RM, von Eye A, editors. New directions for youth development: Theory, practice and research: Vol. 95. Pathways to positive development among diverse youth. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 101–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, McMahon T. Peer reputation among inner city adolescents: Structure and correlates. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1996;6:581–603. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Sexton C. The high price of affluence. In: Kail RV, editor. Advances in child development and behavior. Vol. 32. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. pp. 125–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod J. Bridging street and school. Journal of Negro Education. 1991;60:260–275. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons from research on successful children. American Psychologist. 1998;53:205–220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Morison P, Pellegrini DS. A revised Class Play method of peer assessment. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:523–533. [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bianchi M. Situational ethnicity and patterns of school performance among immigrant and nonimmigrant Mexican-descent students. In: Gibson M, Ogbu JU, editors. Minority status and schooling. New York: Garland; 1991. pp. 205–247. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Changing demographics in this American population: Implications for research on minority children and adolescents. In: McLoyd VC, Steinberg L, editors. Studying minority adolescents: Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Merten DE. The meaning of meanness: Popularity, competition, and conflict among junior high school girls. Sociology of Education. 1997;70:175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, Bukowski WM, Pattee L. Children's peer relations: A metanalytic review of popular, rejected, neglected, controversial, and average sociometric status. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:99–128. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. The consequences of the American caste system. In: Neisser U, editor. The school achievement of minority children: New perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 19–56. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne JW. Race and academic disidentification. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1997;89:728–735. [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst JT, Hopmeyer A. Sociometric popularity and peer-perceived popularity: Two distinct dimensions of peer status. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1998;18:125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rodkin PC, Farmer TW, Pearl R, Van Acker R. Heterogeneity of popular boys: Antisocial and prosocial configurations. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:14–24. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Swenson LP, Waller EM. Overt and relational aggression and perceived popularity: Developmental differences in concurrent and prospective relations. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:378–387. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Noll E, Stoltzfus J, Harpalani V. Identity and school adjustment: Revisiting the "acting White" assumption. Educational Psychologist. 2001;36:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:797–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. The New York Times. 1987. Apr 25, Why Japan's students outdo ours; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Dornbusch SM, Brown BB. Ethnic differences in adolescent achievement: An ecological perspective. American Psychologist. 1992;47:723–729. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.6.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL, Bruschi C, Dodge KA, Coie JD. The relation between behavior problems and peer preference in different classrooms. Child Development. 1999;70:169–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry R. Recent advances in measurement theory and the use of sociometric techniques. In: Cillessen AHN, Bukowski WM, editors. Recent advances in the measurement of acceptance and rejection in the peer system. Vol. 88. New York: Jossey-Bass; 2000. pp. 27–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Bachman JG. Explaining racial/ethnic differences in adolescent drug use: The impact of background lifestyle. Social problems. 1991;38:333–357. [Google Scholar]

- Weisfeld G, Bloch SA, Ivers JW. A factor analytic study of peer-perceived dominance in adolescent boys. Adolescence. 1983;18:229–243. [Google Scholar]

- Weisfeld G, Bloch SA, Ivers JW. Possible determinants of social dominance among adolescent girls. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1984;144:115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1998;90:202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth RH, Barrientos GA. Comparison of Hispanic and Anglo graduate record examination scores and academic performance. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 1990;8:128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Weller CL, Meland JA. Extent of drug abuse among juvenile offenders. Journal of Drug Issues. 1993;23:515–524. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Growing up American: The challenge confronting immigrant children and children of immigrants. Annual Review of Sociology. 1997;23:63–95. [Google Scholar]