Abstract

Deficiency in n-3 fatty acids has been accomplished through the use of an artificial rearing method in which ICR mouse pups were hand fed a deficient diet starting from the second day of life. There was a 51% loss of total brain DHA in mice with an n-3 fatty acid deficient diet relative to those with a diet sufficient in n-3 fatty acids. N-3 fatty acid adequate and deficient mice did not differ in terms of locomotor activity in the open field test or in anxiety-related behavior in the elevated plus maze. The n-3 fatty acid deficient mice demonstrated impaired learning in the reference-memory version of the Barnes circular maze as they spent more time and made more errors in search of an escape tunnel. No difference in performance between all dietary groups in the cued and working memory version of the Barnes maze was observed. This indicated that motivational, motor and sensory factors did not contribute to the reference memory impairment.

Introduction

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n3) is a highly unsaturated n-3 fatty acid that is concentrated in the nervous system [1]. Dietary restriction of n-3 fatty acids in the maternal diet does not grossly affect growth or development of the offspring but does lead to a reduction of DHA accumulation in the developmental period and results in substantially lower DHA levels in the brain and other organs relative to those supplied with dietary n-3 fatty acid, with a reciprocal increase in the n-6 docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n6, DPAn-6) [2, 3]. Many studies have now demonstrated that prolonged consumption of an n-3 fatty acid-deficient diet accompanied by a significant lower brain DHA content results in poorer performance in a variety of cognitive tasks. For example, a lower brain DHA content was associated with impairment in simple associative learning tasks [4, 5, 6] alterations in electroretinograms [7, 8, 9], and avoidance tasks in rodents [10, 11]. Our previous work showed that rats on an n-3 fatty acid deficient diet throughout two generations had a deficit in two-odor olfactory discrimination tasks [12, 13] and olfactory-cued set learning [14]. We also demonstrated that n-3 fatty acid deficiency affected spatial performance in the Morris water maze [15, 16, 17, 18]. In the present study, the Barnes circular maze, a hippocampus-dependent cognitive task that requires spatial reference memory, was employed to study performance in mice fed an n-3 fatty acid deficient diet beginning on the second day of postnatal life. The Barnes circular maze is similar to the Morris water maze in that both tests require an escape response. However, the Barnes maze may offer the advantage that it is less stressful and physically less taxing than the Morris water maze since it does not involve swimming [19, 20] a significant factor given the relatively poor swimming ability of mice. In the present study, n-3 fatty acid deficiency was achieved by implementation of an artificial rearing (AR) method.

Methods

Animals and dietary treatments

The results of two experiments, conducted with two separate batches of ICR mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) are presented in this paper. An artificial rearing method, adapted from the work of Hoshiba [21], has been described in detail elsewhere [17]. In short, the method employs a custom-designed bottle-nipple system to hand feed pups starting from the second day of life. There were two different types of milk – an n-3 fatty acid deficient (n-3 Def) and an n-3 fatty acid adequate (n-3 Adq). The major difference between them a small amount of LNA (3 wt%) and DHA (1 wt%) was added to the n-3 Adq diet. The artificial mice milk formula was modified from the method of Yajima et al. [22] (Table 1). The fat content in both milks was 16g/100 g diet, and the amount of n-3 fatty acids in the n-3 Def and n-3 Adq diets were <0.1 and 4% of total fatty acids, respectively. The mice were weaned to the corresponding pelleted diets, with a fat content of 10g/kg diet. The source of n-3 fatty acids in the n-3 adequate diet was flaxseed oil and DHASCO™ (Martek Biosciences, Columbia, MD); flaxseed oil supplied α-linolenic acid (18:3n3, LNA), as 2.5% of total fatty acids and DHASCO supplied DHA as 1.3% of total fatty acids. The deficient diet contained a residual level of 0.04% of LNA. Dam-reared mice were fed by the dams on a diet containing 3 wt% LNA as the only source of n-3 fatty acids and were weaned to the same diet as their dams.

Table 1.

Nutrient composition of the artificial milk for mouse pups.

| Amount (weight/100mL milk)

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Ingredient | n-3 Def | n-3 Adq |

| Protein (g) | ||

| Whey protein (Alacen, WPI)a | 3.64 | 3.64 |

| Why protein Hydrolysate H | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Casein (Alacid, acid casein)a | 3.46 | 3.46 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | ||

| alpha-Lactose b | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Fat (g) | ||

| MCT oil e | 2.08 | 2.08 |

| Coconut oil (hydrogenated) f | 4.32 | 4.32 |

| 18:1n-9 ethyl ester g | 7.2 | 6.6 |

| 18:2n-6 ethyl ester g | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| 18:3n-3 ethyl ester g | — | 0.48 |

| 22:6n-3 ethyl ester g | — | 0.16 |

| Cholesterol b | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Vitamins (g) | ||

| Vitamin mix c | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Vitamin C b | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Tricholine citrate b | 0.37 | 0.37 |

| Minerals (mg) | ||

| NaOH b | 50 | 50 |

| KOH b | 170 | 170 |

| GlyCaPO4 b | 800 | 800 |

| MgCl2 6H2O b | 183 | 183 |

| CaCl2 2H2O b | 210 | 210 |

| Ca3-4H2O-citrateb | 250 | 250 |

| Na2HPO4 b | 114 | 114 |

| KH2PO4 b | 51 | 51 |

| FeSO4 b | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| ZnSO4 b | 6.0 | 6.0 |

| CuSO4 b | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| MnSO4 b | 0.075 | 0.075 |

| NaF b | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| KI b | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| K2SO4 b | 163.1 | 163.1 |

| Na2SeO4 b | 0.036 | 0.036 |

| (NH4)2MoO4 b | 0.028 | 0.028 |

| Na2O3Si 9H2O b | 5.075 | 5.075 |

| CrK(SO4)2 12H2O b | 0.963 | 0.963 |

| LiCl b | 0.061 | 0.061 |

| H3BO3 b | 0.285 | 0.285 |

| NiCO3 b | 0.111 | 0.111 |

| NH4VO3 b | 0.023 | 0.023 |

| Others (g) | ||

| Carnitine b | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| Picolinate b | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Ethanolamine b | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| Taurine b | 0.015 | 0.015 |

| Serine b | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Cystine b | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Tryptophan b | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Methionine b | 0.005 | 0.005 |

Component sources were as follows: NZMP (North America) Inc, Santa Rosa, CA;

Sigma-Aldrich Corp. St. Louis, MO;

Harlan, Madison, WI;

Novartis Medical Nutrition, Fremont, MI;

Dyets, Bethlehem, PA;

Nu-Chek Prep. Inc., Elysian, MN;

Chicago Sweeteners, Chicago, IL.

Behavioral testing

Behavioral testing started at 7 wk of age. Mice in both experiments were subjected to the open field test and the elevated plus maze. In the first experiment, the reference-memory version of the Barnes maze test was implemented and in the second experiment, the working-memory and cued versions of the Barnes maze were used.

Open Field Test

To assess spontaneous locomotor activity, mice were placed into the center of an open field apparatus (56 × 56 cm; Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN). The open field apparatus was supplied with 32 infrared photo beams in the walls and 9 holes in the floor (also equipped with photo beams) which allowed the automated registry of different ambulation parameters (locomotor activity), rearing and the holes searched (exploratory activity). These parameters were recorded over a 60 min period.

Elevated Plus-Maze

In order to measure anxiety-related behavior, an elevated plus-maze was used (Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN). The plus-maze was elevated 70 cm above the floor and consisted of two open and two closed arms of the same size (35 × 5 cm); closed arms were surrounded by walls 15 cm high. The arms were constructed of black acrylic slabs radiating from a central platform (5 × 5 cm) to form a plus sign. The maze was equipped with 36 infrared photo beams, which allowed measuring time spent on open and closed arms and the number of entries into open and closed arms. Beams mounted on the edge of the open arms captured the subject hanging its head over the edge.

Barnes Circular Maze

Measures of locomotor activity and the elevated plus-maze parameters served as controls for the key endpoint of spatial task performance in the Barnes circular maze. The Barnes maze uses a white, brightly lit circular platform 122 cm in diameter and raised 50 cm above the floor with 40 holes, 5 cm in diameter, evenly spaced around the circumference (Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN). Animals were trained to locate a black escape tunnel beneath one of the holes in response to aversive light stimuli and remember its position using extra-maze cues (spatial version) or intra-maze cues (cued version). The latencies to enter the escape box and the number of errors (defined as visits to any non-target hole) were recorded by a video camera mounted directly over the center of the maze. A Video Tracking System (ViewPoint Life Sciences, Otterburn Park, QC, Canada) was used to analyze all parameters mentioned above as well as the distance an animal moved and the amount of time the animal spent ambulating and freezing. In the cued version of the Barnes maze, the location of the tunnel was indicated by a prominent visual cue above the hole leading to the tunnel. A difference in the performance on this task would be indicative of alterations in the sensory, motor or motivational attributes of the animal [23]. In the spatial version, the animal developed a spatial map of the extra-maze cues, which was then used to locate the hidden tunnel. A spatial learning ability test may address working memory, i.e., memory for the specific details of a particular session, or reference memory, which refers to learning the rules associated with a task. In the case of the Barnes circular maze, the location of the escape tunnel remained the same between testing sessions, or the entire testing time, when the reference memory was addressed. When working memory was assessed, the position of the tunnel remained the same within a session (one session consisted of four trials given in one day), but moved to a different location between testing days. In the working memory test, the performance was evaluated as an improvement in the animal’s ability to locate the target hole between the first and the last trial of the session.

In order to familiarize mice with the maze and the existence of the escape tunnel, they were subjected to one habituation session prior to the beginning of testing. The habituation trial was started by placing the animal in the center of the maze under a bucket in a room that was brightly lit and rich in consistently located spatial cues. After 1-min, the bucket was lifted and the mouse was allowed to explore the maze. If during the subsequent 3 min it failed to find the escape tunnel, it was guided there. After entering the escape tunnel, the animal was allowed to remain in the tunnel for 1 min.

Reference-memory version (experiment 1)

On the day following the habituation session, actual test trials were carried out under identical conditions, except that the mice needed to locate the escape tunnel by themselves. Animals were given two trials a day with a 3-min interval between trials. Each trial ended when the mouse entered the goal tunnel or after 3 min had elapsed. Scores for each animal were averaged daily between the two trials. All surfaces were routinely cleaned with a soap solution after each trail to eliminate possible olfactory cues from the preceding animals. Mice were trained to locate the escape tunnel for 16 consecutive days. Ten days after the last training trial, mice were retested to evaluate memory retention. The position of the target hole was the same as during the training period.

In the working-memory version (experiment 2) of the maze, mice were given 4 trials per day to learn the position of the tunnel, but on the following day it was changed to a new location. There was a 15-min inter-trial interval for each animal. Mice were tested for 6 days in this version of the maze and the results were averaged for each trial between testing days. The results (latencies and errors) were expressed as a percentage of the initial trial for each individual and then group averages were computed for each experimental group.

Cued version (experiment 2)

After one week interval from the end of the working memory testing, mice were tested on the cued version of the maze (5 days of training). In this case, the maze was surrounded by a white poster-board (20 cm high) and the location of the escape tunnel was indicated by a black vertical stripe 3 cm wide drawn on the board. There were other intra-maze cues drawn on the board – a circle, a triangle and a square, the positions of which remained constant during the experiment. The location of the stripe changed from day to day as it indicated the new position of the tunnel. As in the reference-memory version, the mice were given two trials a day with a 3-min inter-trail interval. Scores for each animal were averaged daily for the two trials.

Fatty Acid Analysis

The mice were decapitated at the end of the study (20 wk of age); brains were rapidly removed and subjected to total lipid extraction by a modification of the Folch method [24]. The total lipid extract was transmethylated with 14% BF3- methanol at 100° C for 60 min by a modification of the method of Morrison and Smith and the methyl esters analyzed by gas chromatography as previously described [25].

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by using Statistica 7 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK) to perform repeated measures ANOVA with Diet as a between-groups factor and Days (Blocks) as a within-groups (repeated) factor. Tukey’s test was used to conduct further post-hoc comparisons among the experimental groups where indicated.

Results

N-3 Def mice did not differ significantly from the n-3 Adq animals in appearance or body weight. All experimental groups were the same in their body weight until 13 wks of age. Beginning at 13 wks of age, dam-reared mice had a lower body weight than did the two AR groups. This body weight difference was observed until the end of experiment, when mice were killed and their tissues were collected for fatty acid analysis (20 wks).

There were significant differences in total n-6, total n-3, and total monounsaturated fatty acid content in the brain among the three dietary groups but no significant differences in total saturates (Table 2). The artificial rearing method was useful in rapidly producing an animal with a low brain DHA level in mice fed the n-3 Def milk probably due to a reduction of DHA accumulation in the developmental period. There was a marked difference in brain DHA among the three groups [F (2, 41) = 202, p < 0.0001]. Mice fed the n-3 Def diet exhibited about a 51 and 47% lower content of brain DHA compared with the n-3 Adq, and dam-reared groups, respectively. Brain DHA in the n-3 Def group was largely substituted for by a marked increase in the percentage of brain DPAn-6 [F (2, 41) = 1142, p <0.0001], but the brain DPAn-6 level was not significantly different between the n-3 Adq and dam-reared groups. There were statistically significant differences in the ratio of DPAn-6/ DHA and n-6/n-3 between the dam-reared versus the n-3 Def group [F (2,41) = 603, p < 0.0001 for DPAn-6/ DHA; F (2,41) = 711, p < 0.0001 for the n-6/n-3], but DPAn-6/ DHA and n-6/n-3 were not significantly different between the n-3 Adq and dam-reared groups.

Table 2.

Brain fatty acid composition of the two artificially reared groups and a dam-reared reference group (Wt% of total fatty acids)*

| Dietary Group

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dam-reared (n = 16) | n-3 Adq (n = 14) | n-3 Def (n = 14) | |

| Fatty Acids | |||

| Total Saturates | 40.8 ± 0.2 | 41.9 ± 0.56 | 41.8 ± 0.25 |

| Total Monounsaturates | 25.8 ± 0.4a | 23.4 ± 0.74b | 23.4 ± 0.40b |

| 18:2n6 | 0.5 ± 0.01a | 0.5 ± 0.02a | 0.4 ± 0.02b |

| 20:4n6 | 7.1 ± 0.12a | 7.9 ± 0.16b | 9.0 ± 0.14c |

| 22:4n6 | 2.2 ± 0.05a | 2.4 ± 0.04b | 3.7 ± 0.04c |

| 22:5n6 | 0.2 ± 0.01a | 0.3 ± 0.01a | 6.5 ± 0.19b |

| Total n-6 PUFA | 10.7 ± 0.14a | 11.7 ± 0.17b | 19.9 ± 0.26c |

| 18:3n3 | 0.1 ± 0.003a | 0.1 ± 0.004a | 0.04 ± 0.003b |

| 20:5n3 | 0.1 ± 0.004a | 0.1 ± 0.01b | NDc |

| 22:5n3 | 0.3 ± 0.01a | 0.2 ± 0.01a | 0.1 ± 0.02b |

| 22:6n3 | 14.6 ± 0.32a | 15.7 ± 0.35b | 7.7 ± 0.20c |

| Total n-3 PUFA | 15.0 ± 0.32a | 16.1 ± 0.36b | 7.9 ± 0.20c |

| 22:5n6/22:6n3 | 0.01 ± 0.001a | 0.02 ± 0.001a | 0.8 ± 0.03b |

| n-6/n-3 | 0.7 ± 0.01a | 0.7 ± 0.01a | 2.5 ± 0.07b |

| Total fatty acids (μg/mg) | 41.3 ± 0.46 | 39.2 ± 0.49 | 41.0 ± 0.44 |

Each parameter is presented as the mean (± SEM) for n = 14–16 mice. Different alphabetical superscripts indicate significant differences by Tukey’s HSD at p < 0.05. ND, not detected (i.e., <0.01%).

Analysis of liver fatty acid composition indicated that liver DHA in the n-3 Def group was 95 and 91% lower compared with the dam-reared and n-3 Adq groups, respectively (p < 0.0001). The DHA was largely replaced by an increased percentage of DPAn-6 (p < 0.0001). The percentage of arachidonic acid was greater in the n-3 Def group compared with those of the dam-reared and n-3 Adq groups (p < 0.01). There were significant differences in the ratio of DPAn-6/DHA and n-6/n-3 in the n-3 Def group compared with those of the dam-reared and n-3 Adq groups (p < 0.0001) for DPAn-6/DHA; (p < 0.0001 for n-6/n-3).

To examine spontaneous locomotor activity and response to a novel environment, mice were assayed in an open-field test. The total number of movements made over a 1h period did not differ significantly between the n-3 Adq and n-3 Def groups, although an elevation of locomotion in the dam-reared group was observed compare to the AR groups (n-3 Adq: 6034 ± 333; n-3 Def: 6333 ± 387; Dam-reared: 7319 ± 456; p<0.05).

To study whether the lack of n-3 fatty acids in the diet affected anxiety-related behavior, mice were evaluated in the elevated plus maze test. The n-3 Def group spent the same amount of time on the open arms and made the same number of entries into the open arms as the n-3 Adq and dam-reared groups (data not presented). Dietary groups did not differ also in the number of head dips made from the open arms of the maze. The dam-reared group made more entries into the closed arms than the two AR groups (p<0.05, one-way ANOVA): n-3 Adq: 11.8 ± 1.4; n-3 Def: 11.6 ± 1.1; Dam-reared: 16.3 ± 1.7.

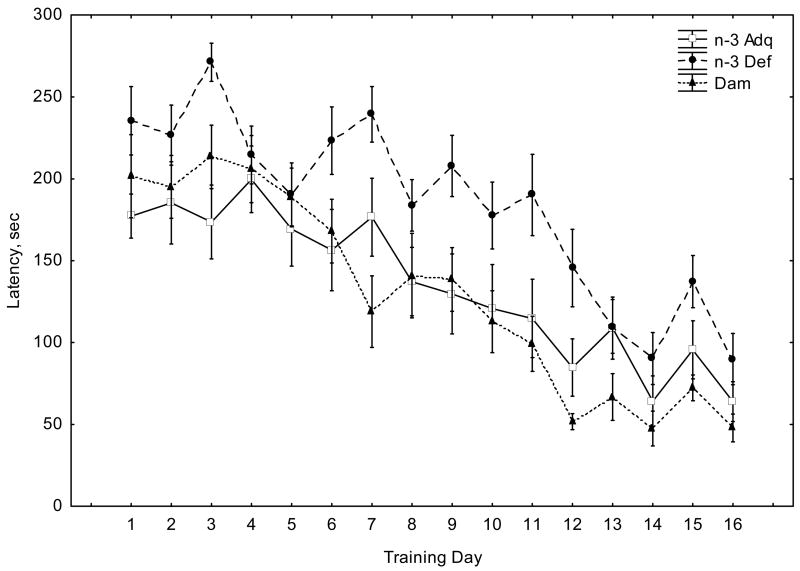

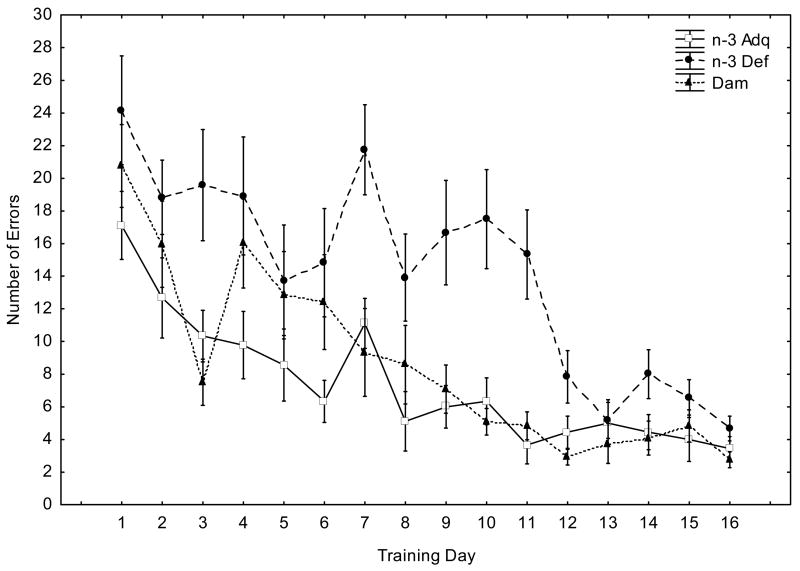

We next studied the performance of mice in the spatial version of the Barnes circular maze. Figure 1 shows that all mice learned to locate the escape tunnel during the course of the training period (days 1–16), as indicated by a progressive reduction in escape latencies and the number of errors. However, the n-3 Def mice did not perform as well as the n-3 Adq and Dam-reared groups: they required longer times to enter the escape hole (Figure 1A) and this was accompanied by a significant increase in the error rate (Figure 1B). Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Diet (F(2, 256)=46.6, p<0.0001) and Days (F(15, 128)=11.8, p<0.0001) in escape latency (Figure 1A). There was no Diet X Days interaction (F(30, )=1.40, p>0.05). ANOVA analysis of error rate (Figure 1B) indicated a significant effect of Diet (F(2, 256)=37.27, p<0.0001), Days (F(15, 128)=11.13, p<0.0001) and a Diet X Days interaction (F(30, 256)=1.74, p<0.05). Post-hoc comparisons among the three experimental groups using Tukey’s test indicated that the n-3 Def group was significantly different from the n-3 Adq and Dam-reared groups in terms of both the escape latency and number of errors made (p<0.01).

Figure 1.

Fig. 1A. Latency to find the escape tunnel in the Barnes maze reference memory test. Values are given as means + SEM (n-3 Adq, n=9; n-3 Def, n=12; Dam, n=12). Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Diet (F(2,256)=46.58, p<0.0001) and Days (F(15,128)=11.83, p<0.0001). There was no significant Diet X Days interaction (F(30,256)=1.40, p>0.05). Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey's test supported that the n-3 Def group was different from the n-3 Adq and Dam-reared groups (p<0.05).

Fig. 1B. Errors made in the Barnes maze reference memory test. Values are given as means + SEM (n-3 Adq, n=9; n-3 Def, n=12; Dam, n=12). Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Diet (F(2,256)=37.27, p<0.0001), Days (F(15,128)=11.13, p<0.0001) and a Diet X Days interaction (F(30,256)=1.74, p<0.05). Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey's test supported that the n-3 Def group was different from the n-3 Adq and Dam-reared groups (p<0.05).

To evaluate memory retention, mice were retested in the Barnes maze 10 days after the last training session. During retention testing, n-3 Def mice did not differ from the n-3 Adq and Dam-reared groups in escape latencies (n-3 Adq: 53.1 ± 6.1 sec; n-3 Def: 51.4 ± 7.4 sec; Dam-reared: 41.7 ± 5.2 sec) or in the number of errors made before finding the target hole (n-3 Adq: 4.8 ± 0.6; n-3 Def: 5.3 ± 1.2; Dam-reared: 5.0 ± 0.7).

In the cued version of the Barnes maze, all mice were able to learn the position of the escape tunnel (data not shown). The n-3 Def and n-3 Adq groups did not differ in the escape latencies while the Dam-reared group was faster than both AR groups (p<0.05, Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons test). No differences were observed between dietary groups in the number of errors made during the search for the escape tunnel.

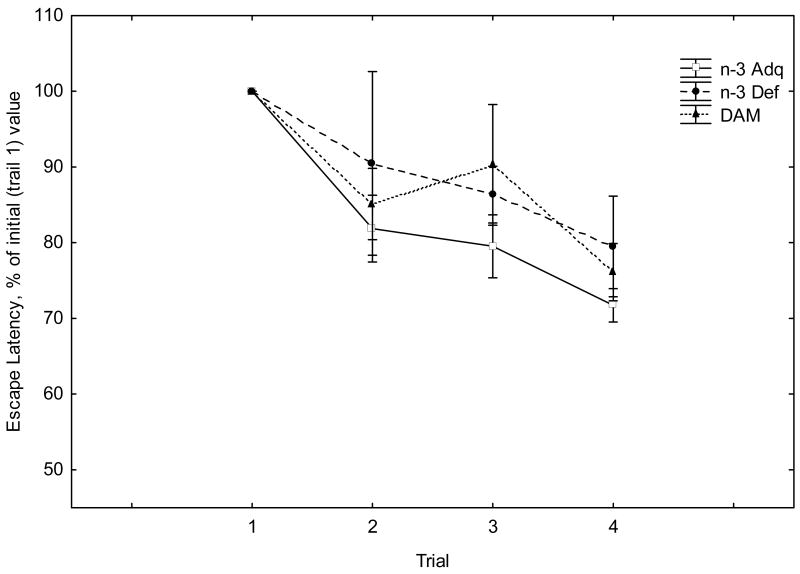

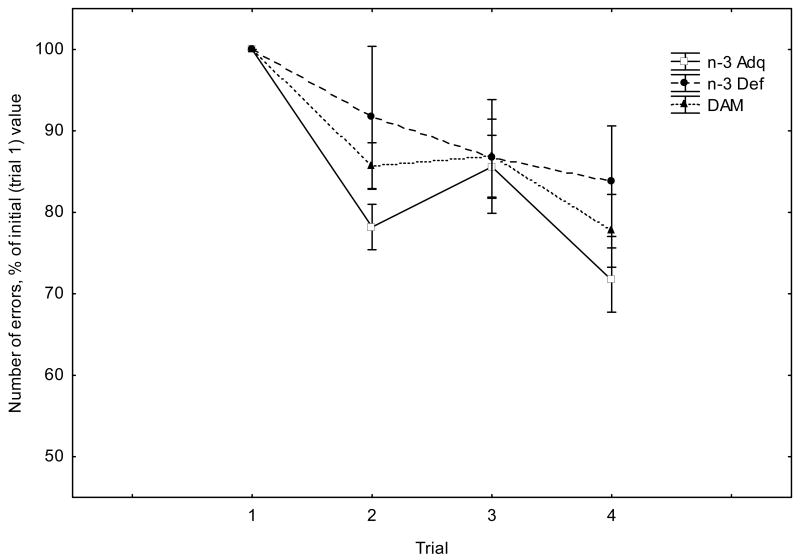

In the working memory version of the Barnes Maze, the escape latency and number of errors made during the search for the escape tunnel decreased over the test sessions (Figure 2). Repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of Trial for escape latency (F(3,20)=6.90, p<0.01) and error rate (F(3,20)=8.33, p<0.001). However, there was no significant effect of Diet nor a significant Diet X Trial interaction for both latency and error rates (F values given in the legend to Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fig. 2A. Escape latency (average across all training days) in the working memory version of the Barnes maze. Values are given as means + SEM, where individual values are expressed as a percentage of the average trial 1value. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Trial (F(3,20)=6.90, p<0.01). There was neither a significant effect of Diet (F(2,40)=1.42, p>0.05) nor a significant Diet x Trial interaction (F(6,40)=0.33, p>0.05).

Fig. 2B. Error rates (average across all training days) in the working memory version of the Barnes maze. Values are given as means + SEM, where individual values are expressed as a percentage of the average trial 1value. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Trial (F(3,20)=8.33, p<0.001). There was neither a significant effect of Diet (F(2,40)=2.169, p>0.05) nor a significant Diet x Trial interaction (F(6,40)=0.62, p>0.05).

Discussion

N-3 Adq and n-3 Def mice did not differ in body weight or locomotor parameters, while dam-reared mice demonstrated lower body weight and increased locomotion compare to both artificially reared groups. The differences in body weight of the dam-reared group compared to the AR groups may have been related to the higher locomotor activity of the dam-reared group or related to developmental stress in the AR groups due to maternal deprivation. Another possible explanation is a different compartmentalization of adipose versus lean body mass.

Our results indicated that n-3 fatty acid deficiency affects spatial learning in the Barnes maze. Moreover it was noteworthy that there was also a significant Diet X Days interaction, indicating that the speed of learning in the deficient mice was decreased. The Barnes maze is similar to the Morris water maze in that it is a hippocampus-dependent cognitive task that requires spatial reference memory [19, 20]. These findings confirm and extend previous observations that depletion of brain DHA leads to poor performance in the Morris water maze [15, 16, 17, 18]. Interestingly, a positive correlation between brain DHA content and performance in the Morris water maze was found [16].

Although the Barnes maze is somewhat similar to the Morris water maze, the Barnes maze offers the advantage that it is less stressful and physically less taxing than the Morris water maze. Choosing a less stressful test to study these dietary groups was indicated since there is some evidence for involvement of DHA in stress responses [26, 27]. We previously demonstrated that n-3 Def mice were more vulnerable to stress in that they behaved similarly to n-3 adequate mice under normal conditions but were significantly more anxious under stressful conditions in the elevated plus maze [27]. If an elevated anxiety level and emotional reactivity are in fact responsible, at least in part, for the poor learning in the Morris water maze, then this effect should be attenuated in a less stressful test, e.g., in the Barnes circular maze. The observation that there remains a deficit in spatial task performance in this less stressful measure suggests that the brain DHA loss also alters cognition.

When mice were retested in the Barnes maze 10 days after the last training session, all experimental groups performed equally well, indicating that n-3 fatty acid status did not alter the retention of spatial memory.

To examine whether the performance deficit observed in n-3 Def mice could be related to sensory, motor or motivational attributes of the animals, mice were tested in the cued version of the Barnes Maze. In this task, n-3 Adq and n-3 Def mice required the same amount of time to find the escape tunnel, while dam-reared mice were faster than both artificially-reared groups. The shorter escape latencies of the dam reared group may have been related to their higher locomotor activity and thus may not represent a real improvement in learning. This interpretation is consistent with the lack of differences in the error rates. The similarity of the n-3 Adq and Def groups in the cued version of the Barnes maze allows us to rule out sensory, locomotor or motivational components from the possible reasons accounting for the spatial learning deficit observed in the n-3 Def mice.

Our data indicated no differences between n-3 Adq, n-3 Def and the dam-reared mice in the working-memory version of the Barnes maze in spite of the marked differences in brain DHA status. This finding is consistent with a previous report concerning the Morris water maze performance of artificially-reared rats in the working-memory version of the task where the investigators found no relationship of the behavior with a wide range of forebrain DHA and arachidonic acid levels [23]. It was somewhat puzzling however that a deficit in performance on the working-memory task of the Morris water maze was observed after two generations of n-3 fatty acid dietary restriction [28]. These tasks only indicate that there is no gross disturbance of working memory but more sensitive methodology may be required to more fully assess working memory.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated for the first time a deficit in spatial learning of n-3 fatty acid deficient mice using the reference-memory version of the Barnes circular maze. No impact of n-3 fatty acid restriction was observed on the cued version of the Barnes maze suggesting that motivational, sensory and motor factors were not critical in medicating the effects on reference memory.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, NIAAA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Salem N., Jr . Omega-3 fatty acids: molecular and biochemical aspects. In: Spiller GA, Scala J, editors. Current Topics in Nutrition and Disease: New Protective Roles for Selected Nutrients. Alan R Liss; New York: 1989. pp. 109–228. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohrhauer H, Holman RT. Alteration of the fatty acid composition of brain lipids by varying levels of dietary essential fatty acids. J Neurochem. 1963;10:523–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1963.tb09855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galli C, Trzeciak HI, Paoletti R. Effects of dietary fatty acids on the fatty acid composition of brain ethanolamine phosphoglyceride: Reciprocal replacement of n-6 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;248:449–454. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto N, Saitoh M, Moriguchi A, Nomura M, Okuyama H. Effect of dietary alpha-linolenate/linoleate balance on brain lipid compositions and learning ability of rats. J Lipid Res. 1987;28:144–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourre JM, Francois M, Youyou A, Dumont O, Piciotti M, Pascal G, Durand G. The effects of dietary alpha-linolenic acid on the composition of nerve membranes, enzymatic activity, amplitude of electrophysiological parameters, resistance to poisons and performance of learning tasks in rats. J Nutr. 1989;119:1880–1892. doi: 10.1093/jn/119.12.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakashima Y, Yuasa S, Hukamizu Y, Okuyama H, Ohara T, Kameyama T, Nabeshima T. Effect of a high linoleate and a high alpha-linolenate diet on general behavior and drug sensitivity in mice. J Lipid Res. 1993;34:239–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benolken RM, Anderson RE, Wheeler TG. Membrane fatty acids associated with the electrical response in visual excitation. Science. 1973;182:1253–1254. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4118.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuringer M, Connor WE, Lin DS, Barstad L, Luck S. Biochemical and functional effects of prenatal and postnatal omega 3 fatty acid deficiency on retina and brain in rhesus monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4021–4025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weisinger HS, Vingrys AJ, Bui BV, Sinclair AJ. Effects of dietary n-3 fatty acid deficiency and repletion in the guinea pig retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:327–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi T, Fukumoto Y, Harada E. Influence of a dietary n-3 fatty acid deficiency on the cerebral catecholamine contents, EEG and learning ability in rat. Behav Brain Res. 2002;131:193–203. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Calatayud S, Redondo C, Martin E, Ruiz JI, Garcia-Fuenties M, Sanjurjo P. Brain docosahexaenoic acid status and learning in young rats submitted to dietary long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid deficiency and supplementation limited to lactation. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:719–723. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000156506.03057.AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greiner RS, Moriguchi T, Hutton A, Slotnik B, Salem N., Jr Rats with low levels of brain docosahexaenoic acid show impaired performance in olfactory-based and spatial learning tasks. Lipids. 1999;34:239–243. doi: 10.1007/BF02562305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greiner RS, Catalan J, Moriguchi T, Salem N., Jr Docosapentaenoic acid does not completely replace DHA in n-3 FA-deficient rats during early development. Lipids. 2003;38:431–435. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalan J, Moriguchi T, Slotnick B, Murthy M, Greiner RS, Salem N., Jr Cognitive deficits in docosahexaenoic acid-deficient rats. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:1022–1031. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.6.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moriguchi T, Greiner RS, Salem N., Jr Behavioral deficits associated with dietary induction of decreased brain docosahexaenoic acid concentration. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2563–2573. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moriguchi T, Salem N., Jr Recovery of brain docosahexaenoate leads to recovery of spatial task performance. J Neurochem. 2003;87:297–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim S-Y, Hoshiba J, Moriguchi T, Salem N., Jr N-3 fatty acid deficiency induced by a modified artificial rearing method leads to poorer performance in spatial learning tasks. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:741–748. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000180547.46725.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim S-Y, Hoshiba J, Salem N., Jr An extraordinary degree of structural specificity is required in neural phospholipids for optimal brain function: n-6 docosapentaenoic acid substitution for docosahexaenoic acid leads to a loss in spatial task performance. J Neurochem. 2005;95:848–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes CA. Memory deficits associated with senescence: a neurophysiological and behavioral study in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1979;93:74–104. doi: 10.1037/h0077579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bach ME, Hawkins RD, Osman M, Kandel ER, Mayford M. Impairment of spatial but not contextual memory in CaMKII mutant mice with a selective loss of hippocampal LTP in the range of the theta frequency. Cell. 1995;81:905–915. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoshiba J. Method for hand-feeding mouse pups with nursing bottles. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2004;43:50–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yajima M, Kanno T, Yajima T. A chemically derived milk substitute that is compatible with mouse milk for artificial rearing of mouse pups. Exp Anim. 2006;55:391–397. doi: 10.1538/expanim.55.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wainwright PE, Xing HC, Ward GR, Huang Y-S, Bobik E, Auestad N, Montalto M. Water maze performance is unaffected in artificially reared rats fed diets supplemented with arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid. J Nutr. 1999;129:1079–1089. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane-Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salem N, Jr, Reyzer M, Karanian J. Losses of arachidonic acid in rat liver after alcohol inhalation. Lipids. 1996;31(Suppl):S153–S156. doi: 10.1007/BF02637068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeuchi T, Iwanaga M, Harada E. Possible regulatory mechanism of DHA- induced anti-stress reaction in rats. Brain Res. 2003;964:136–143. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fedorova I, Salem N., Jr Omega-3 fatty acids and rodent behavior. Special Issue: The emerging role of omega-3 fatty acids in psychiatry. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:271–289. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wainwright PE, Xing HC, Girard T, Parker L, Ward GR. Effects of dietary n-3 fatty acid deficiency on Morris water-maze performance and amphetamine-induced conditioned place preference in rats. Nutr Neurosci. 1998;1:281–293. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.1998.11747238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]