Abstract

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are important pathogen recognition molecules and are key to epithelial immune responses to microbial infection. However, the molecular mechanisms that regulate TLR expression in epithelia are obscure. Micro-RNAs play important roles in a wide range of biological events through post-transcriptional suppression of target mRNAs. Here we report that human biliary epithelial cells (cholangiocytes) express let-7 family members, micro-RNAs with complementarity to TLR4 mRNA. We found that let-7 regulates TLR4 expression via post-transcriptional suppression in cultured human cholangiocytes. Infection of cultured human cholangiocytes with Cryptosporidium parvum, a parasite that causes intestinal and biliary disease, results in decreased expression of primary let-7i and mature let-7 in a MyD88/NF-κB-dependent manner. The decreased let-7 expression is associated with C. parvum-induced up-regulation of TLR4 in infected cells. Moreover, experimentally induced suppression or forced expression of let-7i causes reciprocal alterations in C. parvum-induced TLR4 protein expression, and consequently, infection dynamics of C. parvum in vitro. These results indicate that let-7i regulates TLR4 expression in cholangiocytes and contributes to epithelial immune responses against C. parvum infection. Furthermore, the data raise the possibility that micro-RNA-mediated post-transcriptional pathways may be critical to host-cell regulatory responses to microbial infection in general.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs)4 are an evolutionarily conserved family of cell surface pattern recognition molecules that play a key role in host immunity through detection of pathogens (1, 2). Most TLRs, upon recognition of discrete pathogen-associated molecular patterns, activate a set of adaptor proteins (e.g. myeloid differentiation protein 88 (MyD88)) leading to the nuclear translocation of transcription factors, such as NF-κB and AP-1, and thus transcriptionally regulate host-cell responses to pathogens, including parasites (3–5). TLRs may also recognize endogenous ligands induced during the inflammatory response (1–4). Evidence is accumulating that the signaling pathways associated with TLRs not only mediate host innate immunity but are also important to adaptive immune responses to microbial infection (6). Epithelial cells express TLRs and activation of TLRs triggers an array of epithelial defense responses, including production and release of cytokines/chemokines and anti-microbial peptides (1–8). Expression of TLRs by epithelia is tightly regulated, reflecting the specific microenvironment and function of each epithelial cell type. This cell specificity is critically important to assure that an epithelium will recognize invading pathogens but not elicit an inappropriate immune response to endogenous ligands or commensal microorganisms (4).

Human bile is thought to be sterile under physiological conditions (9). Nevertheless, the biliary tract is connected and open to the intestinal tract and therefore, is potentially exposed to microorganisms from the gut. For example, duodenal microorganisms are believed to be a major source of bacterial infection in several biliary diseases (9, 10). Indeed, Cryptosporidium parvum, a coccidian parasite of the phylum Apicomplexa, preferentially infects the small intestine yet can infect biliary epithelial cells (i.e. cholangiocytes) causing biliary tract disease. We and others previously reported that human cholangiocytes express all 10 known TLRs and produce a variety of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and antimicrobial peptides in response to microbial infection, suggesting a key but poorly understood role for cholangiocytes in epithelial defense (9–14). We also previously demonstrated that TLR2 and TLR4 signals mediate cholangiocyte responses including production of human β-defensin 2 against C. parvum via TLR-associated activation of NF-κB (11). Dominant negative TLR/MyD88 expressing cholangiocytes have diminished defenses against C. parvum infection in vitro (11). Thus, TLRs and the mechanisms involved in their regulation are key elements for cholangiocyte defense against C. parvum infection.

Micro-RNAs (miRNAs) are a newly identified class of endogenous small regulatory RNAs (15–17). In the cytoplasm, they associate with messenger RNAs (mRNAs) based on complementarity between the miRNAs and the target mRNAs. This binding causes either mRNA degradation or translational suppression resulting in gene suppression at a post-transcriptional level (15–17). Micro-RNAs exhibit tissue-specific or developmental stage-specific expression, indicating that their cellular expression is tightly regulated (15–17). Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms underlying cellular regulation of miRNA expression are unclear. Recent studies have indicated that transcription factors, such as c-Myc and C/EBPα, appear to be involved in the expression of miRNAs, suggesting a role for transcription factors in regulation of miRNA expression (18, 19). It has become clear that miRNAs play essential roles in several biological processes, including development, differentiation, and apoptotic cell death (15–27). Also, an antiviral role for miRNAs has been described in plants (15). Direct evidence of the importance of miRNAs in vertebrates to control viral invasion has also recently emerged from studies using human retroviruses (20); a host-cell miRNA, miR-32, has been identified that can effectively suppress primate foamy virus type 1 replication (20). Conversely, a primate foamy virus type 1-derived protein, Tas, alters host-cell miRNA expression (20). Thus, host-pathogen interactions can influence host-cell miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional suppression, a process potentially involved in the regulation of epithelial defenses in response to microbial infection.

In work described here, we found that human cholangiocytes express members of the let-7 family. We demonstrate that at least one of these, let-7i, directly regulates TLR4 expression. We also show that C. parvum infection of cholangiocytes decreases let-7i expression via a MyD88/NF-κB-dependent mechanism. Moreover, a decrease of let-7i expression is associated with C. parvum-induced up-regulation of TLR4 in infected cells, and consequently, the infection dynamics of C. parvum in vitro. Thus, a novel let-7-mediated regulatory pathway for TLR4 expression has been identified in cholangiocytes, a process that is involved in epithelial responses against microbial infection.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

C. parvum and Cholangiocyte Cell Lines

C. parvum oocysts of the Iowa strain were purchased from a commercial source (Bunch Grass Farm, Deary, ID). Before infecting cells, oocysts were excysted to release infective sporozoites as previously described (11, 28). Freshly excysted sporozoites were tested for lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activity using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate test kit (Bio-Whittaker, Walkersville, MD) as reported by others (29) and only Limulus Amebocyte Lysate-negative sporozoites were used in the study. H69 cells are SV40-transformed normal human cholangiocytes originally derived from normal liver harvested for transplant. These cholangiocytes continue to express biliary epithelial cell markers, including cytokeratin 19, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase and ion transporters consistent with biliary function and have been extensively characterized (11, 28).

In Vitro Infection Model

An in vitro model of human biliary cryptosporidiosis using H69 cells was employed as previously described (11, 28). Before infecting cells, oocysts were excysted to release infective sporozoites (11, 28). Infection was done in a culture medium consisting of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F-12, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin and freshly excysted sporozoites (1 × 106 sporozoites/per slide well or culture plate). Inactivated organisms (treated at 65 °C for 30 min) were used for sham infection controls. For some experiments, H69 cells were exposed to LPS (100 ng/ml, Invivogen) for 12 h. For the inhibitory experiments, SN50, one specific inhibitor of NF-κB, was added in the medium at the same time as C. parvum. A concentration of 50 µg/ml, which showed no cytotoxic effects on H69 cells or on C. parvum sporozoites, was selected for the study. All the experiments were performed in triplicate.

Immunofluorescent Microscopy

After exposure to C. parvum as described above, cells were fixed with 2% paraform-aldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline. For double-immunofluorescent labeling of TLR4 with C. parvum, fixed cells were incubated with a monoclonal antibody TLR4 (Imgenex) mixed with a polyclonal antibody against C. parvum (a gift from Dr. Guan Zhu, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX) followed by anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) as we previously reported (11, 28). In some experiments, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (5 µm) was used to stain cell nuclei. Labeled cells were assessed by confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Western Blot

A previously reported semi-quantitative Western blot approach was used to assess TLR4 expression in cells (11). Briefly, total cell lysates were obtained from the cells after exposure to C. parvum and blotted for TLR4 and actin. Antibodies to TLR4 (Imgenex) and actin (Sigma) were used. TLR4 levels were expressed as their ratio to actin (11).

Microarray Analysis of Endogenous miRNA Expression

H69 cells were grown to confluence and total RNAs were isolated using the TRIzol kit (Invitrogen). Micro-RNA expression profile in H69 cells was performed with a recently developed semi-quantitative microarray approach with the GenoExplorer™ micro-RNA Biochips by Genosensor (Tempe, AZ). 5S rRNA was detected as the control and data were analyzed with the software provided (Genosensor).

let-7i Precursor and Antisense Oligonucleotide

To manipulate cellular function of let-7i in H69 cells, we utilized an antisense approach to inhibit let-7i function and precursor transfection to increase let-7i expression. For experiments, H69 cells were grown to subconfluence and then incubated in culture medium containing let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide (Ambion, 20 ng/ml) for 12 h. For let-7i precursor transfection, H69 cells were grown to 60–70% confluence and transfected with the let-7i precursor (Ambion, 20 ng/ml) using the NeoFx transfection agent (Ambion). Those cells were usually used for experiments 12 h after transfection.

Northern Blot

Total RNA from cultured cells was isolated using the conventional method of acid phenol:chloroform extraction using TRI Reagent (Sigma) and subsequent alcohol precipitation. The total RNA was then used as the starting material for the enrichment of miRNAs. Micro-RNAs were enriched using the mirVana miRNA Isolation kit (Ambion).

For Northern blot detection, 1 µg of miRNAs was separated on a 15% polyacrylamide gel in 1× TBE. Following electrophoresis, miRNAs were transferred to nylon membrane using a semi-dry transfer and then UV cross-linked to the membrane using 120 mJ for 30 s. The probes for the detection of miRNAs and the 5S rRNA were synthesized using an in vitro transcription approach with [α-32P]UTP. The templates for the in vitro transcription of let-7i were: let-7i (5′-TGAGGTAGTAGTTTGTGCTGTCCTGTCTC-3′) and 5S rRNA (5′-GTTAGTACTTGGATGGGAGACCGCCCTGTCTC-3′). The membranes were incubated with 2.5 × 106 cpm per blot overnight at 42 °C. Subsequently, stringent washes were performed and the membranes were exposed to autoradiography film for 24–48 h.

In Situ Hybridization

Cells were grown on 4-well chamber slides and fixed with 4% formaldehyde, 5% acetic acid for 15 min after a short washing with phosphate-buffered saline. After treatment with pepsin (0.1% in 10mm HCl) for 1 min, cells were dehydrated through 70, 90, and 100% ethanol. Treated cells were then hybridized with the fluorescent probes (10 µm) in probe dilution (EXIQON, Vedbaek, Denmark) for 30 min at 37 °C followed by confocal microscopy (LSM 510, Carl Zeiss). FITC-tagged antisense probe specific to let-7i was obtained from Ambion. Fluorescent intensity in the cytoplasm of cells was measured and calculated with an analysis system of the LSM 510 provided by Carl Zeiss, Inc.

Luciferase Reporter Constructs and Luciferase Assay

Complementary 59-mer DNA oligonucleotides containing the putative let-7 target site within the 3′-UTR of human TLR4 mRNA were synthesized with flanking SpeI and HindIII restriction enzyme digestion sites (sense, 5′-GATACTAGTATCGGGCCCAAGAAAGTCATTTCAACTCTTACCTCATCAAGTAAGCTTACA-3′; antisense, 5′-TGTAAGCTTACTTGATGAGGTAAGAGTTGAAATGACTTTCTTGGGCCCGATACTAGTATC). The sense and antisense strands of the oligonucleotides were annealed by adding 2 µg of each oligonucleotide to 46 µl of annealing solution (100 mm potassium acetate, 30 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, and 2 mm magnesium acetate) and incubated at 90 °C for 5 min and then at 37 °C for 1 h. The annealed oligonucleotides were digested with SpeI and HindIII and ligated into the multiple cloning site of the pMIR-REPORT Luciferase vector (Ambion, Inc.). In this vector, the post-transcriptional regulation of luciferase was potentially regulated by miRNA interactions with the TLR4 3′-UTR. Another pMIR-REPORT Luciferase construct containing TLR4 mRNA 3′-UTR with a mutant (ACCTCAT to ACCGAAT) at the putative seed region for let-7 binding was also generated as a control. We then transfected cultured cholangiocytes with each reporter construct, as well as let-7i antisense oligonucleotide or precursor, followed by assessment of luciferase activity 24 h after transfection. Luciferase activity was then measured and normalized to the expression of the control TK Renilla construct as previously reported (11).

Quantitative RT-PCR

A quantitative RT-PCR approach (LightCycler) to measure C. parvum infection was established by modification of a previous report (11). Briefly, total RNA was harvested from the cells after exposure to C. parvum and reversed transcribed to cDNA and amplified using Amplitaq Gold PCR master mixture (Roche). Primers specific for C. parvum 18S ribosomal RNA (forward, 5′-TAGAGATTGGAGGTTGTTCCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTCCACCAACTAAGAACGGCC-3′) were used to amplify the cDNA specific to the parasite. Primers specific for human plus C. parvum 18S (11) were used to determine total 18S cDNA. Data were expressed as copies of C. parvum 18S versus total 18S. Similarly, primers specific for human TLR4 (forward: 5′-TACTCACACCAGAGTTGCTTTCA-3′ and reverse: 5′-AGTTGACACTGAGAGAGGTCCAG-3′) and let-7i primary transcript (Pri-let-7i) (forward, 5′-CCTAGAAGGAATTGAGGGGAGT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGGCATTTAACTGCTGAAAGAA-3′) were used to amplify the cDNA specific to TLR4 and Pri-let-7i. Data of quantitative RT-PCR analysis were expressed as copies of targets versus 18S.

RESULTS

Human Cholangiocytes Express let-7 Family Members, miRNAs That Mediate TLR4 Expression

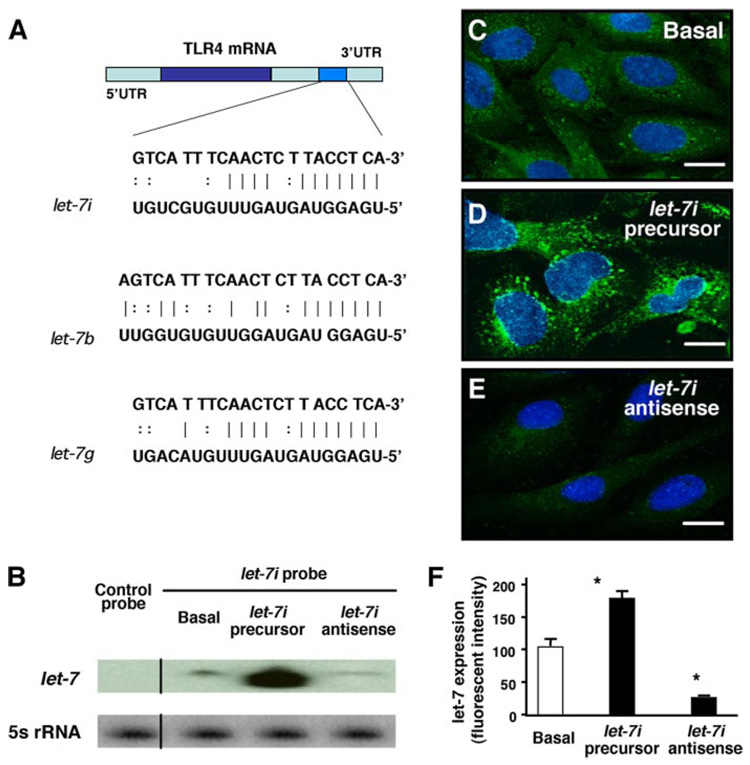

H69 cells, SV40-transformed human cholangiocytes derived from normal liver harvested for transplantation (10), were used to test the miRNA expression profile in human cholangiocytes. Employing a recently developed semiquantitative microarray approach that detects 385 human miRNAs provided and performed by Genosensor, we detected a distinct expression profile of miRNAs in our cells (Table 1). Using in silico computational target prediction analysis, we identified that of those miRNAs expressed in H69 cells, at least three of the let-7 family, let-7b, let-7i, and let-7g, have complementarity to TLR4 mRNA within the 3′-UTR (Fig. 1A). let-7b and -7g are contained within known expressed sequence tags (EST), let-7i is also potentially within an intron of an EST (DA092355). However, we were unable to amplify this EST from H69 cells (forward, 5′-GGTCACGTGGTGAGGAGTAGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CATTCTTGTCATATTGAAAATACGC-3′), whereas the EST was amplified from human cerebellum (data not shown). Additionally, let-7i has promoter elements immediately upstream of the precursor transcript (30), suggesting that let-7i expression is potentially regulated independent of EST DA092355. We therefore selected let-7i to test a potential role of miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional suppression in regulated TLR4 expression. To further confirm the expression of let-7 in H69 cells, we used an antisense probe complementary to let-7i (Mayo DNA core facility) for Northern blot analysis. Using this technique, we cannot eliminate the possibility that other let-7 family members are detected. However, the pattern of expression of the let-7 family can be discerned. let-7 miRNAs were detected in our cells by Northern blot analysis, whereas a scrambled control probe showed no signal (Fig. 1B). To further assess the expression and intracellular distribution of let-7 miRNAs in H69 cells, we used a FITC-tagged antisense oligonucleotide complementary to let-7i (Ambion) for in situ hybridization analysis followed by confocal microscopy. The antisense probe complementary to let-7i was visualized predominantly in the cytoplasm with smaller amounts in the nuclei of cells (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, cells transfected with a let-7i precursor (Ambion) showed a significantly increased let-7 signal as assessed by both Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1B) and in situ hybridization (Fig. 1, D and F). Cells transfected with a let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide (Ambion) showed a significant decrease of let-7 signal by in situ hybridization (Fig. 1, E and F) and a mild decrease by Northern blot (Fig. 1B).

TABLE 1. Micro-RNAs detected in H69 cells by microarray analysis.

Expression of miRNAs in H69 cells as assessed by microarray analysis. H69 cells were grown to confluence and total RNAs isolated for miRNA microarray analysis with the GenoExplorer™ micro-RNA Biochips by Genosensor. Data were expressed as the fluorescent intensity for each miRNA, representing the mean values from three independent analyses. Expression of 5S rRNA was used as the control.

| miRNAs | Fluorescent intensity |

|---|---|

| miR-001 | 730 ± 120 |

| miR-009 | 140 ± 9.1 |

| miR-15a | 218 ± 8.7 |

| miR-15b | 188 ± 7.0 |

| miR-24 | 230 ± 2.1 |

| miR-27b | 232 ± 1.7 |

| miR-29a | 178 ± 3.6 |

| miR-29b | 146 ± 3.6 |

| miR-93 | 141 ± 3.6 |

| miR-100 | 211 ± 2.3 |

| miR-103 | 151 ± 1.5 |

| miR-122a | 158 ± 3.2 |

| miR-124a | 710 ± 230 |

| miR-125a | 193 ± 4.6 |

| miR-125b | 3490 ± 120 |

| miR-128a | 330 ± 40 |

| miR-130a | 165 ± 9.8 |

| miR-130b | 202 ± 7.5 |

| miR-133a | 1880 ± 120 |

| miR-149 | 181 ± 11 |

| miR-154 | 161 ± 4.0 |

| miR-181b | 174 ± 2.1 |

| miR-194 | 153 ± 2.5 |

| miR-197 | 174 ± 4.6 |

| miR-199a | 152 ± 2.7 |

| miR-214 | 864 ± 16 |

| miR-216 | 163 ± 2.0 |

| miR-296 | 169 ± 4.5 |

| miR-299 | 171 ± 5.5 |

| miR-302a | 186 ± 10 |

| miR-302d | 164 ± 5.6 |

| miR-324-3p | 150 ± 1.7 |

| miR-337 | 155 ± 3.6 |

| miR-338 | 251 ± 9.6 |

| miR-339 | 182 ± 10 |

| miR-340 | 172 ± 8.0 |

| miR-342 | 164 ± 7.0 |

| miR-368 | 162 ± 11 |

| miR-370 | 175 ± 1.2 |

| miR-371 | 168 ± 7.4 |

| miR-372 | 298 ± 19 |

| miR-373 | 322 ± 18 |

| miRNA373* | 205 ± 21 |

| miR-374 | 720 ± 80 |

| let-7b | 388 ± 8.5 |

| let-7i | 161 ± 11 |

| let-7g | 172 ± 4.0 |

| rRNA-5s | 210 ± 30 |

FIGURE 1. Complementarity of let-7 family miRNAs expressed in cholangiocytes to the 3′-UTR of TLR4 mRNA and manipulation of let-7i expression in cultured human cholangiocytes.

A, complementarity of let-7 family miRNAs detected in H69 cells to the 3′-UTR of TLR4 mRNA. Using in silico computational target prediction analysis, we identified that the expressed let-7 family members, let-7b, let-7i, and let-7g, have complementarity to the 3′-UTR of TLR4 mRNA. B–F, manipulation of let-7i expression in H69 cells with specific let-7i precursor or antisense oligonucleotide as assessed by Northern blot analysis (B) or by in situ hybridization (C–F). let-7 miRNAs were detected in H69 cells by Northern blot analysis using a probe complementary to let-7i (B). The control probe showed no signal. Whereas cells treated with a let-7i precursor (Ambion) showed an increased signal indicating an increase of let-7, cells treated with a let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide (Ambion) showed a mild decrease of let-7 signal (B). 5S rRNA was probed to confirm equal loading of mRNA. A FITC-tagged antisense oligonucleotide complementary to let-7i was used to visualize let-7 miRNAs. The antisense probe was visualized predominantly in the cytoplasm with a limited detection in the nucleus (C). Furthermore, cells treated with the precursor showed an increased fluorescence (D), whereas cells treated with the antisense oligonucleotide showed a significant decrease of fluorescent signal (E). F, quantitative analysis of fluorescent intensity of the FITC-tagged let-7i antisense oligonucleotide. A total of about 200 cells were randomly selected for each group and each data bar represents mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, ANOVA versus basal non-transfected control cells (Basal). Bars, 5 µm.

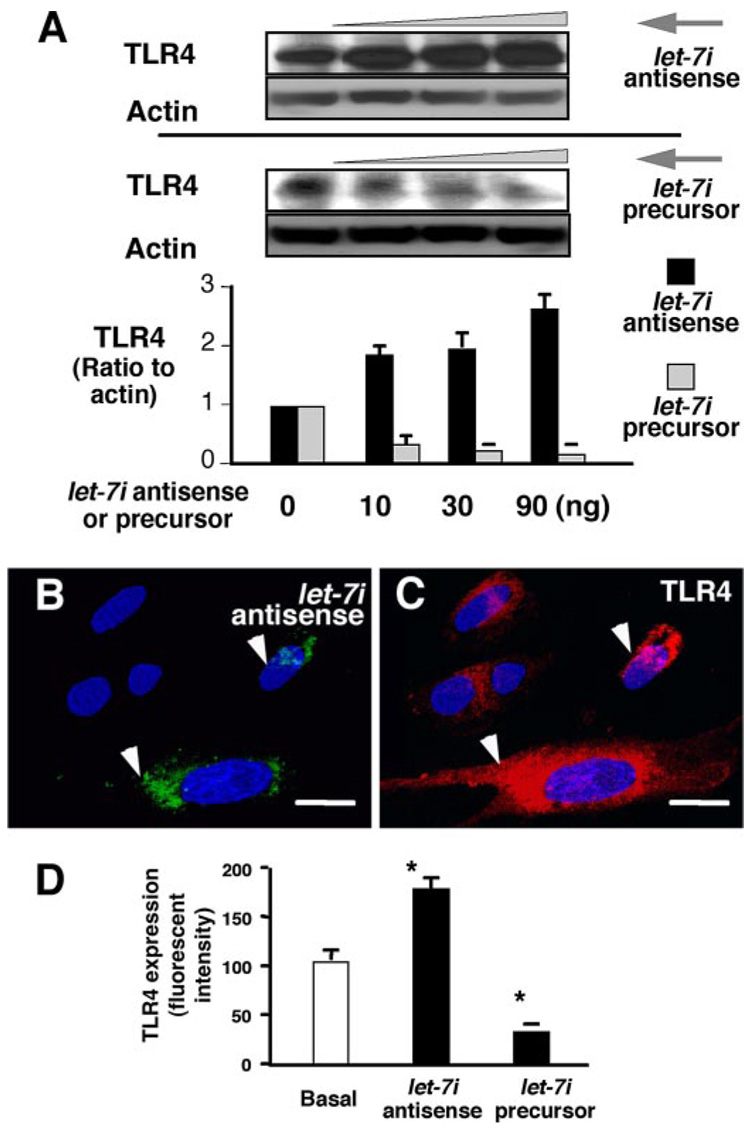

Having established the approaches to manipulate intracellular let-7 levels in cholangiocytes, we next tested whether alteration of let-7 cellular levels affects TLR4 protein content in H69 cells. We transfected cells with the let-7i precursor or the let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide for 12 h and then measured TLR4 protein expression in cells by quantitative Western blotting. We found a dose-dependent increase of TLR4 protein content in cultured cholangiocytes after treatment with the let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide (Fig. 2A). In contrast, overexpression of let-7i with the precursor decreased TLR4 protein content in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Because transfection of let-7i precursor and antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide is limited to a portion of the cell population, we tested whether alteration of TLR4 protein content occurs only in directly transfected cells. To accomplish this, the let-7i precursor or antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide was tagged with FITC using the mirVana miRNA Probe Construction kit (Ambion) to label transfected cells. Expression of TLR4 in cultured cells was visualized by immunofluorescent microscopy. As shown in Fig. 2, B and C, an increase of TLR4 protein (Fig. 2C, in red) was detected only in cells directly transfected with let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide (Fig. 2B, in green) compared with non-transfected cells. Quantitative analysis showed a significant increase of TLR4-specific fluorescence in cells transfected with let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide and a significant decrease of TLR4 specific fluorescence in cells treated with the let-7i precursor compared with nontransfected control cells, respectively (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these data reveal that human cholangiocytes express multiple endogenous miRNAs, including members of the let-7 family, which have complementarity to TLR4 mRNA, and that modulation of at least one of these, let-7i, can mediate TLR4 protein expression in cholangiocytes in vitro.

FIGURE 2. let-7i mediates TLR4 expression in cultured cholangiocytes.

A, effects of let-7i on TLR4 protein expression by Western analysis. H69 cells were transfected with a let-7i precursor or let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide for 12 h followed by Western blot for TLR4. A dose-dependent increase of TLR4 protein content was detected after treatment with let-7i antisense oligonucleotide. In contrast, overexpression of let-7i with the let-7i precursor decreased TLR4 protein content in a dose-dependent manner. B and C, TLR4 expression in cells transfected with a let-7i antisense oligonucleotide as assessed by immunofluorescence. H69 cells were transfected with a FITC-conjugated antisense oligonucleotide complementary to let-7i for 12 h followed by immunofluorescent staining for TLR4. An increased expression of TLR4 protein (in red, C) was detected in directly transfected cells (arrows, in green, B) compared with non-transfected cells. D, effects of let-7i on TLR4 protein expression by quantitative fluorescent analysis. H69 cells were transfected with either let-7i precursor or let-7i antisense oligonucleotide for 12 h followed by quantitative analysis of immunofluorescent signals for TLR4. A total of about 200 cells were randomly selected for each group and each data bar represents mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, ANOVA versus with non-transfected control cells (Basal). Bars, 5 µm.

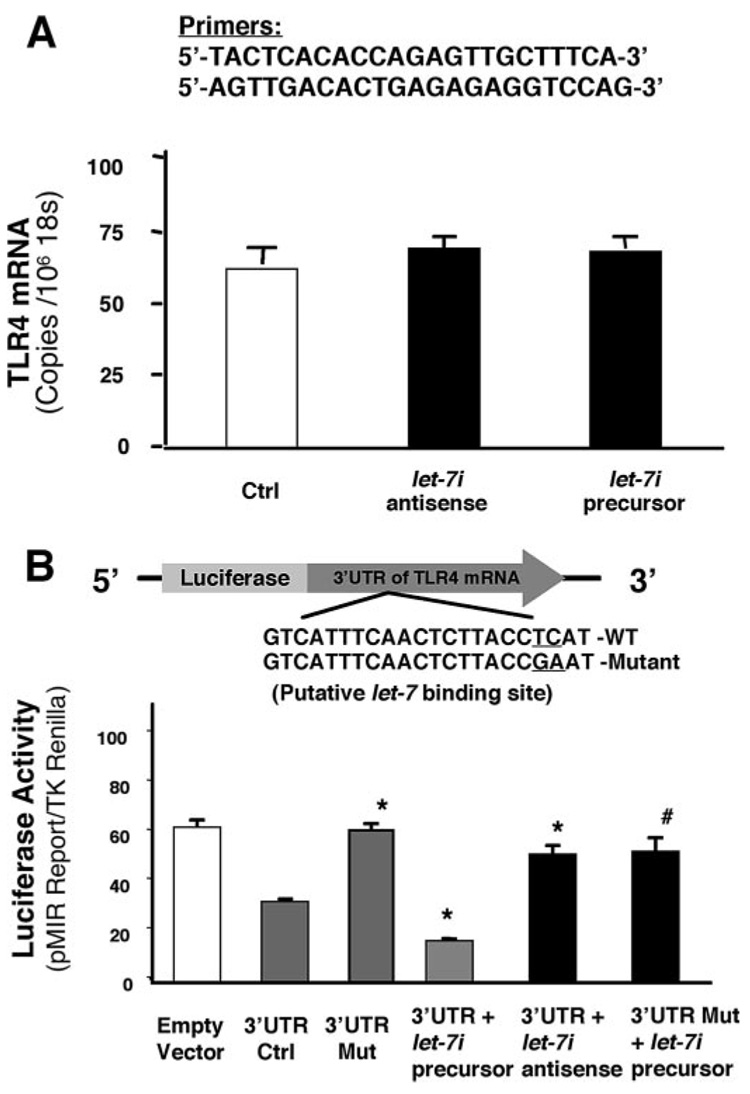

let-7i Mediates TLR4 Expression via Translational Suppression

Micro-RNAs mediate post-transcriptional suppression via either mRNA cleavage or translational suppression. To test whether let-7i can induce cleavage of TLR4 mRNA, we measured the mRNA level of TLR4 in cultured cholangiocytes transfected with either let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide or let-7i precursor by quantitative RT-PCR. No significant difference of TLR4 mRNA was found in cells transfected with either let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide or let-7i precursor (Fig. 3A). To directly address whether let-7i binds to the 3′-UTR of TLR4 mRNA resulting in a translational suppression, we generated a pMIR-REPORT luciferase construct containing the TLR4 mRNA 3′-UTR with the putative let-7 binding site (Fig. 3B). In addition, another pMIR-REPORT luciferase construct containing the TLR4 mRNA 3′-UTR with a mutation at the putative let-7 binding site (ACCTCAT to ACCGAAT) was generated as a control (Fig. 3B). We then transfected cultured cholangiocytes with each reporter construct, as well as let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide or precursor, followed by assessment of luciferase activity 24 h after transfection. As shown in Fig. 3B, a significant decrease of luciferase activity was detected in cells transfected with the TLR4 3′-UTR construct under basal conditions (i.e. no antisense or precursor treatment). No change of luciferase was observed in cells transfected with the mutant TLR4 3′-UTR construct. Importantly, let-7i precursor significantly decreased luciferase reporter translation and in contrast, let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide markedly increased luciferase reporter translation. A mutation in the binding sequence eliminated the let-7i precursor-induced decrease of reporter translation. Taken together, the above data suggest that the seed region for let-7 binding within the TLR4 3′-UTR is critical for TLR4 translational regulation in H69 cells. Furthermore, manipulation of cellular levels of let-7i results in alterations of TLR4 protein expression by suppressing translation via interactions with the 3′-UTR of TLR4 mRNA rather than mRNA cleavage.

FIGURE 3. let-7i mediates TLR4 protein expression via post-transcriptional suppression.

A, effects of let-7i on TLR4 mRNA content. H69 cells were transfected with either let-7i precursor or let-7i antisense oligonucleotide for 12 h followed by quantitative RT-PCR for TLR4 mRNA. Data were normalized to the 18S rRNA level and expressed as copies of TLR4 mRNA/106 copies 18S rRNA. B, targeting of let-7i to the 3′-UTR of TLR4 mRNA. A reporter construct with the potential binding site for let-7 in the 3′-UTR of TLR4 was generated. H69 cells were transiently co-transfected for 24 h with the reporter construct and either let-7i antisense oligonucleotide or let-7i precursor. Luciferase activities were measured and normalized to the control TK Renilla luciferase level. Bars represent the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, ANOVA versus cells transfected only with the reporter construct (3′-UTR Ctrl); #, p < 0.05, ANOVA versus cells transfected with the reporter construct plus let-7i precursor (3′ UTR + let-7i precursor).

LPS Stimulation and C. parvum Infection Decrease let-7i Expression in Cholangiocytes via a MyD88/NF-κB Signaling-dependent Mechanism

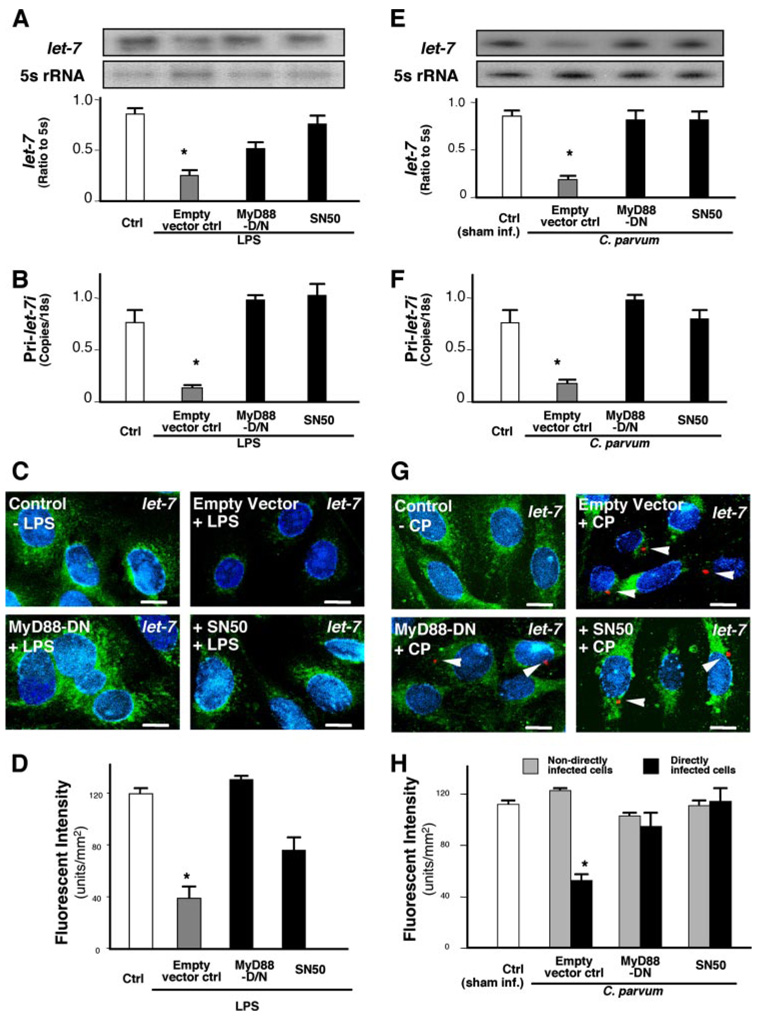

Having demonstrated that let-7i mediates TLR4 translation in cholangiocytes, we then tested whether this regulation is of physiological or pathophysiological significance. Expression of TLR4 protein in epithelial cells is finely regulated and alterations of TLR4 expression have been reported in intestinal and airway epithelial cells following microbial infection (1, 31). Therefore, we measured let-7i expression in cholangiocytes upon LPS stimulation and following infection by C. parvum, a parasite that infects both intestinal and biliary epithelium. We previously demonstrated that C. parvum infection activates TLR signals in infected cholangiocytes in culture, including activation of the adaptor protein, MyD88, and nuclear translocation of NF-κB in directly infected cells (28). Here, a probe complementary to let-7i detected significantly less signal by Northern blot analysis following LPS stimulation (Fig. 4A) or following C. parvum infection (Fig. 4E). However, given the sequence similarities between mature let-7 transcripts, we could not definitively differentiate between family members. Therefore, to further demonstrate let-7i modulation following C. parvum infection and LPS stimulation, we performed quantitative RT-PCR for the primary transcript of let-7i using primers based on the 3′ sequence of the primary let-7i transcript obtained from 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (data not shown). A decrease of Pri-let-7i expression was confirmed in cells upon LPS stimulation (Fig. 4B) or following C. parvum infection (Fig. 4F). No change for miR-24, a randomly selected miRNA expressed in cholangiocytes (Table 1) as a control, was detected after infection (data not shown).

FIGURE 4. LPS stimulation and C. parvum infection decrease let-7i expression in cholangiocytes in a NF-κB dependent manner.

A–H, expression of let-7i in cholangiocytes after treatment with LPS (A–D) or infection by C. parvum (E–H). H69 cells, as well as cells stably transfected with a MyD88 functionally deficient dominant negative mutant construct (MyD88-DN) or an empty control vector, were exposed to LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h or C. parvum for 12 h followed by Northern blot (A and E), quantitative RT-PCR (B and F) or in situ hybridization (C and G) analysis for let-7i. For Northern blot analysis, 5S rRNA was blotted to confirm that an equal amount of total RNA was used. let-7 signals, detected with the let-7i antisense probe, from three independent experiments were measured using a densitometric analysis and expressed as the ratio to 5S rRNA (A and E). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed with specific primers to let-7i primary transcript and expressed as copies/18S rRNA (B and F). For in situ hybridization analysis, an FITC-tagged antisense probe complementary to let-7i (Ambion) was used to detect let-7 family miRNAs. Cells were also stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole to label the nuclei in blue. Representative confocal images are shown in C and G. C. parvum was stained red using a specific antibody (arrowheads in G). D and H are quantitative analyses of let-7 expression detected with the fluorescently tagged antisense oligonucleotide complementary to let-7i in the cytoplasm of cultured cells by in situ hybridization after treatment with LPS (D) or infection by C. parvum (H), respectively. A total of about 200 cells were randomly selected for each group and each data bar represents mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, ANOVA versus no-LPS treated control cells (Ctrl, in A, B, and D) or sham infected cells (Sham Inf. Ctrl, in E, F, and H). Bars, 5 µm.

To test whether MyD88 or NF-κB are involved in the C. parvum-induced decrease of let-7 expression in cholangiocytes, we measured expression of let-7 in cells either stably transfected with a functionally deficient dominant negative (DN) mutant of MyD88 or treated with a specific NF-κB inhibitor, SN50, after exposure to C. parvum. Transfection of cells with MyD88-DN and inhibition of NF-κB with the inhibitor, SN50, partially inhibited the LPS or C. parvum-induced decrease of let-7 expression (Fig. 4, A and E). Decreased let-7 expression in cholangiocytes upon LPS stimulation was further confirmed by in situ hybridization using a FITC-tagged probe complementary to let-7i (Fig. 4C, in green). Transfection of cells with MyD88-DN and inhibition of NF-κB with SN50 inhibited the LPS-induced decrease of let-7 expression (Fig. 4, C and D).

Activation of MyD88/NF-κB signals in cholangiocytes following C. parvum infection is limited to directly infected cells (28). If C. parvum infection decreases let-7 expression via activation of the MyD88/NF-κB signals, decrease of let-7 expression should be limited to directly infected cells. Indeed, a decrease of let-7 signal as visualized by in situ hybridization was detected only in cells directly infected by C. parvum, not in bystander non-infected cells (Fig. 4, G and H). Transfection of cells with MyD88-DN and inhibition of NF-κB with SN50 inhibited the C. parvum-induced decrease of let-7 expression (Fig. 4, G and H). Equally important, these results exclude LPS contamination in our C. parvum sporozoite preparation because decreased expression of let-7 induced by C. parvum is limited only to directly infected cells (Fig. 4G), whereas in the control experiment LPS decreases let-7 expression in all cells (Fig. 4C). Taken together, the above data suggest that LPS and C. parvum infection cause decreased let-7 expression in infected cholangiocytes via a MyD88/NF-κB-dependent mechanism.

Decrease of let-7i Is Involved in Expression of TLR4 in Cholangiocytes following C. parvum Infection or LPS Stimulation

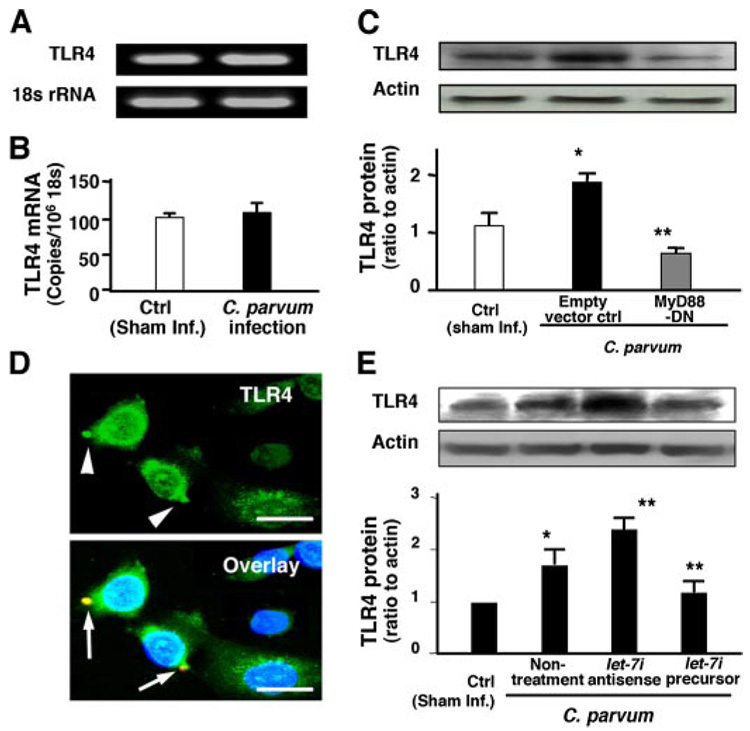

To test whether let-7i-mediated TLR4 expression occurs during microbial infection of cholangiocytes, we first measured TLR4 mRNA and protein expression in cells after exposure to C. parvum for 12 h. Expression of TLR4 mRNA was not different in sham-infected cells compared with C. parvum-infected cells as assessed by both RT-PCR (Fig. 5A) and quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5B). In contrast, protein expression of TLR4 was significantly increased in cells exposed to C. parvum (Fig. 5C), and this effect was abrogated in cells stably transfected with MyD88-DN after exposure to C. parvum (Fig. 5C). To further clarify the relationship between C. parvum infection and TLR4 expression, we measured TLR4 expression in C. parvum-infected cells by immunofluorescent microscopy. Consistent with activation of MyD88/NF-κB signals in directly infected cells, increased expression of TLR4 (arrowheads in Fig. 5D) was found only in cells directly infected by the parasite (arrows in Fig. 5D) not in bystander non-infected cells.

FIGURE 5. let-7i is involved in C. parvum-induced up-regulation of TLR4 in cholangiocytes.

A and B, TLR4 mRNA expression in cells after exposure to C. parvum for 12 h by RT-PCR (A) and quantitative RT-PCR (B). No significant difference in TLR4 mRNA levels was detected between the sham-infected cells and cells exposed to C. parvum. C, up-regulation of TLR4 protein in cells following C. parvum infection. Whereas a low expression of TLR4 protein was detected in control sham-infected cells, a significant increase of TLR4 protein was found in cells exposed to the parasite. A decreased expression of TLR4 was found in cells transfected with MyD88-DN after exposure to C. parvum. D, up-regulation of TLR4 protein in directly infected cells by immunofluorescent microscopy. TLR4 was stained in green, C. parvum in red, and the nuclei in blue. Increased expression of TLR4 protein (arrowheads) was found only in cells directly infected by the parasite (arrows), not in bystander non-infected cells. E, effects of manipulation of let-7i levels on C. parvum-induced TLR4 up-regulation in cholangiocytes as assessed by Western blot and quantitative densitometric analysis. Cells treated with let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide showed a further increase of TLR4 protein content following C. parvum infection compared with infection control cells. In contrast, transfection of cells with the let-7i precursor diminished the C. parvum-induced increase of TLR4 protein. *, p < 0.05 compared with sham infected cells (Sham inf. Ctrl). **, p < 0.05, ANOVA versus with cells transfected with the empty vector (C) or cells without oligonucleotide or precursor treatment (E). Bars, 5 µm.

To test the potential role of let-7i in C. parvum-induced up-regulation of TLR4 protein in infected cells, we assessed the effects of experimentally manipulated let-7i cellular levels on C. parvum-induced TLR4 up-regulation in cholangiocytes. Cells were first transfected with let-7i precursor or antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide, respectively, and then exposed to C. parvum. We found a significant increase of TLR4 protein content in infected cells compared with control cells (Fig. 5E). Cells treated with let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide showed a further increase of TLR4 protein content following C. parvum infection (Fig. 5E). In contrast, transfection of cells with the let-7i precursor diminished the C. parvum-induced increase of TLR4 protein (Fig. 5E). Similarly, a significant increase of TLR4 protein content was found in LPS-treated cells. Cells pre-treated with let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide showed a further increase of TLR4 protein content and transfection of cells with the let-7i precursor diminished the LPS-induced increase of TLR4 protein (data not shown).

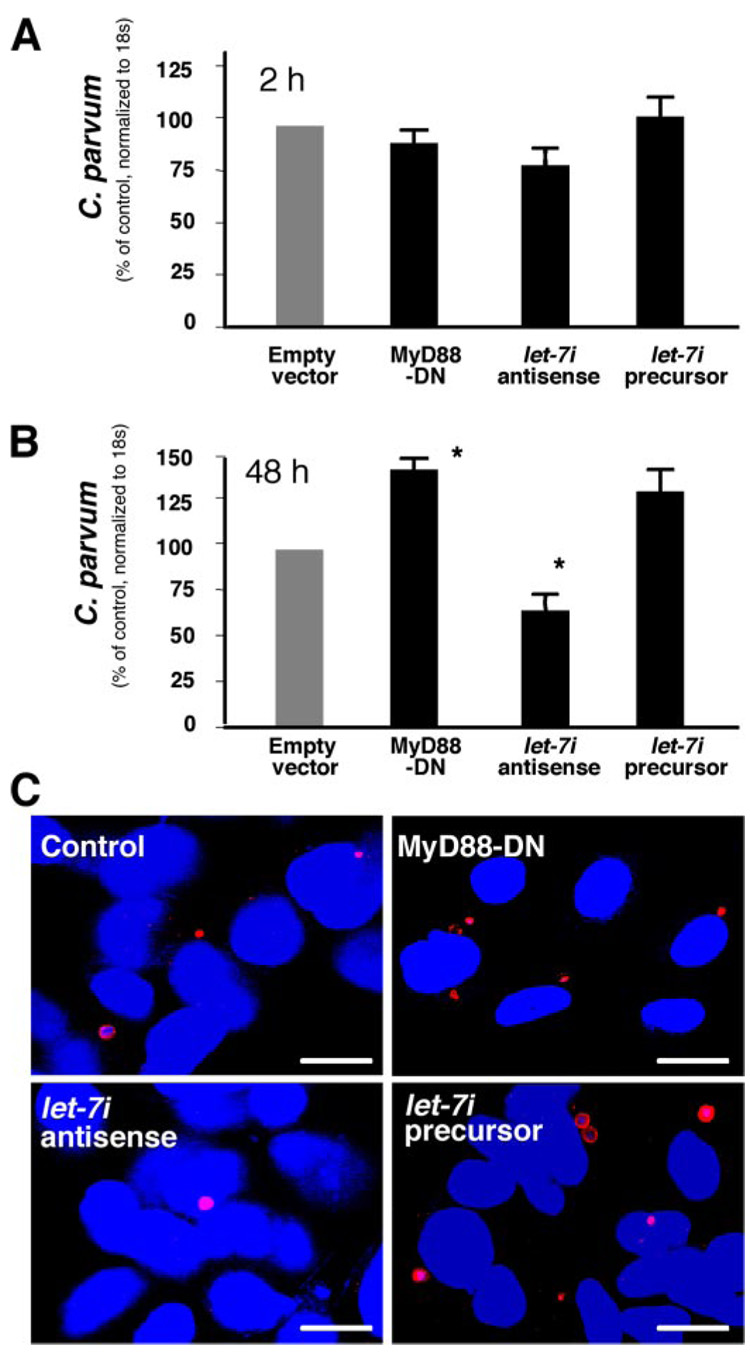

let-7i and Associated TLR4 Protein Expression Are Involved in Cholangiocyte Immune Responses against C. parvum Infection

To test directly whether let-7i and let-7i-associated TLR4 regulation are involved in cholangiocyte defense responses against C. parvum infection, we then assessed the number of parasites detected over time in cultured cholangiocytes transfected with let-7i precursor or antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide. Cells were first transfected with let-7i precursor or antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide and then exposed to C. parvum. After incubation with the same number of C. parvum sporozoites for 2 h to allow sufficient host-cell attachment and cellular invasion (28), cells were washed with culture medium to remove non-attached and non-internalized parasites. Cells were then harvested for RNA isolation to measure initial parasite host-cell attachment and invasion in cholangiocytes using a quantitative RT-PCR approach we previously reported (11). Some cells were also further cultured for an additional 48 h to assess parasite propagation/survival in cells. We found that the parasite burden detected after initial exposure to C. parvum for 2 h were similar in all the cells, including those transfected with let-7i precursor or antisense oligonucleotide, suggesting that let-7i does not affect parasite initial host-cell attachment and cellular invasion (Fig. 6A). Consistent with our previous studies (11), a significant increase in parasite burden was found in MyD88-DN stably transfected cells 48 h after initial infection. Interestingly, we also detected a significantly higher parasite burden in let-7i precursor-treated cells than in the control cells. In contrast, a significantly lower parasite burden was detected in let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide-treated cells (Fig. 6B). An increased parasite burden was further confirmed by immunofluorescent microscopy in MyD88-DN stably transfected cells or cells transfected with the let-7i precursor (Fig. 6C). A decreased parasite burden was confirmed in let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide-treated cells (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that the machinery for miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation exists in cholangiocytes and is potentially involved in C. parvum-induced epithelial innate immune responses.

FIGURE 6. let-7i is involved in cholangiocyte immune responses against C. parvum infection in vitro.

A, effects of manipulation of let-7i levels on C. parvum attachment and invasion of cholangiocytes in vitro as assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. H69 cells stably transfected with a control empty vector or MyD88-DN construct, as well as let-7i antisense or precursor, were exposed to an equal number of C. parvum for 2 h followed by extensive washing and continued culture. A similar number of parasites was detected as assessed by quantitative RT-PCR in all the cells, including those transfected with let-7i precursor or antisense oligonucleotide, after initial exposure to C. parvum for 2 h. *, p < 0.05, ANOVA versus cells transfected with an empty vector control. B, effects of manipulation of let-7i levels on C. parvum burden in cholangiocytes in vitro 48 h after initial exposure to the parasite by quantitative RT-PCR. A significant increase in parasite number was found in MyD88-DN stably transfected cells and cells transfected with the let-7i precursor 48 h after the initial infection. In contrast, a significantly lower number of parasites were detected in let-7i antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide-treated cells. C, effects of manipulation of let-7i levels on C. parvum burden in cholangiocytes in vitro 48 h after initial exposure to the parasite as assessed by immunofluorescent microscopy. C. parvum parasites were stained in red and nuclei in blue. Bars, 5 µm.

DISCUSSION

The key findings in this report are: (i) let-7 family members are expressed in cholangiocytes and mediate TLR4 expression via translational regulation; (ii) C. parvum infection and LPS stimulation decrease let-7 expression in cholangiocytes via a MyD88/NF-κB-dependent mechanism; (iii) the C. parvum-induced decrease of let-7 expression is associated with up-regulation of TLR4 in cholangiocytes; and (iv) experimentally induced suppression or induction of let-7i causes reciprocal alterations in cholangiocyte immune response to C. parvum infection in vitro. These data suggest that let-7 regulates C. parvum-induced up-regulation of TLR4 in cholangiocytes and contributes to epithelial defense responses against C. parvum.

One of the important observations in our study is that let-7i regulates TLR4 expression via translational suppression in human cholangiocytes. Expression of let-7 family members in cultured normal human cholangiocytes was evident by microarray, and Northern blot analyses, whereas specific detection of let-7i was evidenced by PCR. By in situ hybridization, let-7 is seen in the nuclei and to a greater extent in the cytoplasm of cultured cholangiocytes, similar to the intracellular distribution of other miRNAs (32). Experimentally induced suppression or induction of let-7i caused reciprocal alterations in TLR4 protein, respectively. Importantly, the change in TLR4 protein levels was limited to cells directly transfected with either the antisense or precursor. Whereas no significant difference of TLR4 mRNA levels in cells transfected with either let-7i antisense or precursor was found, let-7i precursor significantly decreased luciferase reporter translation using a luciferase reporter plasmid containing the 3′-UTR of TLR4 mRNA with the putative let-7 binding site. Additionally, let-7i antisense markedly increased luciferase reporter translation and a mutation in the binding sequence blocked the let-7i precursor-induced decrease of luciferase reporter translation. Taken together, our data indicate that let-7i is expressed in cholangiocytes and regulates TLR4 expression via translational suppression. It is likely that other members of the let-7 family, in particular, let-7b and let-7g, also regulate TLR4 expression in cholangiocytes, however, the specific expression profiles, based on primary, precursor, and mature transcript expression, need further investigation.

Expression of TLRs by epithelia is tightly regulated to assure that an epithelium will recognize invading pathogens but not elicit an inappropriate immune response to endogenous ligands or commensal microorganisms (4). Up-regulation of TLRs, such as TLR4, has recently been reported in intestinal and airway epithelial cells in response to microbial infection with Helicobacter pylori and Salmonella enterica (31, 33). Here, we found that C. parvum infection decreases let-7i expression and more importantly, this process is involved in C. parvum-induced up-regulation of TLR4 in infected cholangiocytes. When cultured human cholangiocytes were exposed to C. parvum, we found a significant increase of TLR4 protein content in infected cells compared with control cells. A decrease of let-7 expression in infected cells was confirmed by multiple approaches including Northern blot and in situ hybridization analyses, as well as specific analysis of Pri-let-7i expression with PCR. Importantly, manipulation of let-7i levels significantly altered C. parvum-induced TLR4 expression. Cells treated with let-7i antisense oligonucleotide showed a further increase of TLR4 protein expression following C. parvum infection. In contrast, increasing let-7i cellular levels with the precursor reduced the C. parvum-induced increase of TLR4 protein. Furthermore, let-7i associated TLR4 expression appears to be involved in LPS-stimulated TLR4 expression in cholangiocytes. Expression of TLRs upon LPS stimulation differs in cell types (34, 35). We found that at an early time point, LPS stimulation increases the TLR4 protein level in cultured cholangiocytes. Manipulation of let-7i levels influences LPS-stimulated TLR4 expression. Thus, let-7i-mediated post-transcriptional regulation may be involved in host-cell responses to microbial infection in general, including but not limited to C. parvum biliary infection.

Micro-RNAs have distinct expression patterns in different cell types, suggesting that cellular expression of miRNAs is tightly regulated (15–17). The role of transcription factors in miRNA expression is still unclear. c-Myc appears to be involved in the expression of the miR-17 cluster (18). It has been reported that C/EBPα regulates miR-223 during human granulocytic differentiation (19). More recently, the NF-κB signaling pathway has been implicated in the induction of miR-146 expression in human monocytes upon LPS stimulation (36). Here, we found that NF-κB may play a critical role in C. parvum-induced let-7i suppression in cholangiocytes. We previously demonstrated nuclear translocation of NF-κB components via TLR-mediated pathogen recognition in C. parvum-infected cells (11). Knock-out of MyD88 or inhibition of NF-κB by specific inhibition partially blocked the C. parvum-induced let-7i decrease, suggesting that TLR/NF-κB signals are involved in C. parvum-induced decreased expression of let-7i. This is further supported by the observation that a decrease of let-7i is limited to directly infected cells, consistent with the nuclear translocation of NF-κB in directly infected cells (28). Whereas in most cases, NF-κB binding to a DNA element drives transcription of associated genes, recent studies indicated that various genes are also down-regulated by NF-κB binding (37, 38). Thus, TLR/NF-κB signals may be involved in C. parvum-induced let-7i suppression in cholangiocytes.

TLRs are key to epithelial innate immunity through detection of invading pathogens and subsequent activation of associated intracellular signaling pathways leading to the release of cytokines/chemokines and anti-microbial peptides (1, 2). We previously demonstrated that TLR2 and TLR4 are involved in the cholangiocyte immune response to C. parvum infection via activation of NF-κB and subsequent secretion of antimicrobial peptides, such as human β-defensin 2 (11). To determine whether let-7i-mediated TLR4 expression is involved in cholangiocyte immune responses against C. parvum infection, we tested C. parvum infection dynamics in cultured cholangiocytes transfected with either let-7i antisense oligonucleotide or precursor. No change of C. parvum initial host-cell attachment and cellular invasion was detected in both let-7i antisense and precursor transfected cells, suggesting that initial parasite attachment/invasion may not be associated with basal let-7i levels. In contrast, a significantly higher parasite burden was detected in cells transfected with let-7i precursor than in the control cells at 48–96 h after initial exposure to an equal number of parasites. A decreased parasite burden was detected in cells transfected with the let-7i antisense oligonucleotide. These data suggest that let-7i and associated TLR4 expression are involved in cholangiocyte immune responses against C. parvum infection.

In conclusion, our data indicate that human cholangiocytes express let-7i, a cellular miRNA that directly regulates TLR4 expression and contributes to epithelial immune responses against C. parvum infection. It will be of interest to extend these studies to other members of the let-7 family, as well as to determine the mechanisms by which TLR/NF-κB signals regulate let-7i miRNA expression and the role of miRNAs in epithelial innate immunity in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. H. D. Dong, D. D. Billadeau, A. H. Limper, A. D. Badley, G. J. Gores, M. A. McNiven, D. K. Podolsky, H. D. Ward, and G. Zhu for helpful and stimulating discussions and D. Hintz for secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI071321 (to X.-M. C.), DK57993 and DK24031 (to N. F. L.) and the Mayo Foundation.

The abbreviations used are: TLRs, Toll-like receptors; miRNAs, micro-RNAs; MyD88, myeloid differentiation protein 88; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; UTR, untranslated region; RT, reverse transcriptase; DN, dominant negative; EST, expressed sequence tag; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira S, Takeda K. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modlin RL, Cheng G. Nat. Med. 2004;10:1173–1174. doi: 10.1038/nm1104-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strober W. Nat. Med. 2004;10:898–900. doi: 10.1038/nm0904-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campos MA, Campos MA, Closel M, Valente EP, Cardoso JE, Akira S, Alvarez-Leite JI, Ropert C, Gazzinelli RT. J. Immunol. 2004;172:1711–1718. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sansonetti PJ. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckmann L, Kagnoff MF. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 2005;27:181–196. doi: 10.1007/s00281-005-0207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harada K, Ohba K, Ozaki S, Isse K, Hirayama T, Wada A, Nakanuma Y. Hepatology. 2004;40:925–932. doi: 10.1002/hep.20379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jo YJ, Choi HS, No NY, Lee OY, Han DS, Hahm JS, Back SS, Savard CE, Lee SP. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:A171–A171. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen XM, Nelson JB, O’Hara SP, Splinter PL, Small AJ, Tietz PS, Limper AH, LaRusso NF. J. Immunol. 2005;175:7447–7456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen XM, Keithly JS, Paya CV, LaRusso NF. N. Eng. J. Med. 2002;346:1723–1731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra013170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzipori S, Ward H. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerrant RL. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1997;3:51–57. doi: 10.3201/eid0301.970106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartel DP. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM. Nature. 2005;433:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ambros V. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT. Nature. 2005;435:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fazi F, Rosa A, Fatica A, Gelmetti V, De Marchis ML, Nervi C, Bozzoni I. Cell. 2005;123:819–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lecellier CH, Dunoyer P, Arar K, Lehmann-Che J, Eyquem S, Himber C, Saib A, Voinnet O. Science. 2005;308:557–560. doi: 10.1126/science.1108784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, Macdonald PE, Pfeffer S, Tuschl T, Rajewsky N, Rorsman P, Stoffel M. Nature. 2004;432:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature03076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatfield SD, Shcherbata HR, Fischer KA, Nakahara K, Carthew RW, Ruohola-Baker H. Nature. 2005;435:974–978. doi: 10.1038/nature03816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu P, Guo M, Hay BA. Trends Genet. 2004;20:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai X, Lu S, Zhang Z, Gonzalez CM, Damania B, Cullen BR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:5570–5575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408192102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, Labourier E, Reinert KL, Brown D, Slack FJ. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. Science. 2004;303:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P. Science. 2005;309:1577–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1113329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen XM, Levine SA, Splinter PL, Tietz PS, Ganong AL, Jobin C, Gores GJ, Paya CV, LaRusso NF. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1774–1783. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brandenburg K, Wagner F, Muller M, Heine H, Andra J, Koch MH, Zahringer U, Seydel U. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:3271–3279. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou X, Ruan J, Wang G, Zhang W. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e37. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmausser B, Andrulis M, Endrich S, Lee SK, Josenhans C, Muller-Hermelink HK, Eck M. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004;136:521–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kloosterman WP, Wienholds E, de Bruijn E, Kauppinen S, Plasterk RH. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:27–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viswanathan VK, Sharma R, Hecht G. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004;56:727–762. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gatti G, Rivero V, Motrich RD, Maccioni M. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2006;79:989–998. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1005597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eun CS, Han DS, Lee SH, Paik CH, Chung YW, Lee J, Hahm JS. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2006;51:693–697. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:12481–12486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poppelmann B, Klimmek K, Strozyk E, Voss R, Schwarz T, Kulms D. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:15635–15643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S, Domon-Dell C, Kang J, Chung DH, Freund JN, Evers BM. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:4285–4291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]