Abstract

Background

Malaria diagnosis is vital to efficient control programmes and the recent advent of malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) provides a reliable and simple diagnostic method. However a characterization of the efficiency of these tests and the proteins they detect is needed to maximize RDT sensitivity.

Methods

Plasmodial lactate dehydrogenase (pLDH) gene of wild isolates of the four human species of Plasmodium from a variety of malaria endemic settings were sequenced and analysed.

Results

No variation in nucleotide was found within Plasmodium falciparum, synonymous mutations were found for Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium. vivax; and three different types of amino acid sequence were found for Plasmodium ovale. Conserved and variable regions were identified within each species.

Conclusion

The results indicate that antigen variability is unlikely to explain variability in performance of RDTs detecting pLDH from cases of P. falciparum, P. vivax or P. malariae malaria, but may contribute to poor detection of P. ovale.

Background

Rapid and reliable diagnosis is one of the key factors in promoting malaria control. The gold standard for malaria diagnosis remains the examination of Giemsa-stained smears by light microscopy. Whilst this standard has a good sensitivity and specificity and allows species and stage differentiation, it does require the expertise of a trained and experienced microscopist, is time-consuming (30 minutes per diagnostic) and requires equipment not always available or maintainable in remote areas. The 1990's have seen the advent of a new rapid diagnostic method, the immunochromatography-based malaria Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs). These assays are fast (revealed in 15 minutes) and, for the most part, very simple to use. Moreover with the change of therapeutic practice towards relatively expensive artemisinin-based combination therapies [1], a good diagnostic has become essential to limit inappropriate treatment and the development of resistance. Although the use of RDTs has spread, their reliability is still questioned in numerous studies [2,3]. These assays detect one or several antigens, the most common are: histidine-rich protein-2 (HRP-2), aldolase and lactate dehydrogenase (pLDH).

Lactate dehydrogenase is an enzyme that catalyzes the inter-conversion of lactate into pyruvate. This enzyme is essential for energy production in Plasmodium [4]. The level of pLDH in the blood has been directly linked to the level of parasitaemia [5].

The genetic diversity of HRP2 has been examined and partly linked to RDT detection sensitivity [6], the genetic variability has also been assessed in aldolase, it has been ruled out as a possible cue for variation RDT sensitivity [7]. Here is the first study of Plasmodium LDH genetic variability as a possible cause of variation in sensitivity of RDTs.

Methods

A total of eight Plasmodium species (Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium. ovale, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium yoeli, Plasmodium chabaudi, Plasmodium berghei and Plasmodium. reichnowi), including the four human pathogens, from numerous origins (Figure 1) were examined with a nested-PCR assay amplifying a 543 bp fragment: corresponding to the 57 to 237 amino acid position of the reference P. falciparum LDH coding sequence (pf13_0141). All field samples analysed were diagnosed by microscopic examination and confirmed by PCR [8] and conserved from previous studies and approved at the time by respective National Ethics Committees. Two sets of PCR and nested primers were designed for this study based on the sequences available on GenBank (Table 1) one set use for P. vivax and P. falciparum, and the other for P. ovale and P. malariae.

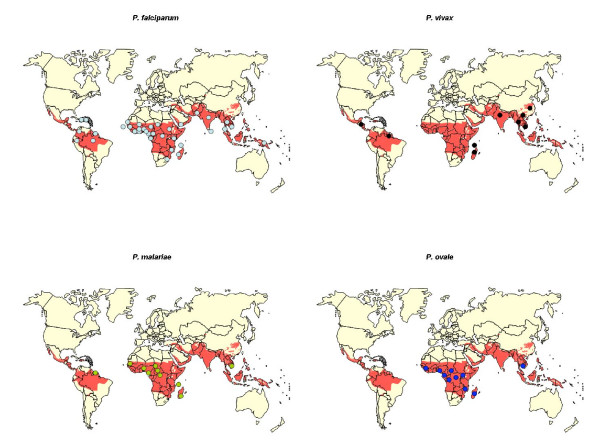

Figure 1.

Worldwide distribution of the isolate sequenced in the study, grouped by species. One dot corresponds to one isolate, in red the malaria endemic area.

Table 1.

PCR and nested-PCR primers used in the study

| PCR primers | Primer sequence 5' to 3' |

| Fv1 | ATGATYGGAGGMGTWATGGC |

| Fv2 | GCCTTCATYCTYTTMGTYTC |

| Mo1 | ATGATWGGAGGTGTTATGGC |

| Mo2 | TGTGTCCRTATTGDCCTTC |

| Nested Primers | |

| Fv1n | AATGTKATGGCWTATTCMAATTGC |

| Fv2n | AACRASAGGWGTACCACC |

| Mo1n | TAGGMGATGTTGTTATGTTYG |

| Mo2n | ATTTCRATAATAGCAGCAGC |

Forty PCR cycle were undertaken using 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 60 s and 72°C for 75 s; the same cycle was used for the nested-PCR but only repeated 35 times. Positive and negative controls were included in all amplification assays. The amplified products were purified using a Quiaquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and sequenced using Big Dye Terminator kit v1.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in an AbiPrism 3130 sequencing machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Results

No variability was observed in P. falciparum (n = 49) with a homology of 100% between all newly sequenced sequences (named F). A single reference sequence on GenBank (corresponding to the FCC1/HN strain) exhibited a different amino acid sequence (named F1). For P. vivax (n = 10), four different types of sequence were found, the mutations observed were all synonymous (named V); no geographic pattern was identified. P. malariae (n = 17) exhibited three different type of sequences, one for African and American isolates and the other two for the south-east Asian isolate and reference strain respectively. Those variations resulted in the same amino acid sequence (named M).

P. ovale (n = 13) exhibited three different types of nucleotide sequences, leading to three different types of amino acid sequences (named O1, O2 and O3). P. berghei and P. yoeli sequences exhibited synonymous mutations (named Y). P. chabaudi exhibited a nucleotide sequence (named C).P. reichnowi and P. falciparum sequences exhibited synonymous mutations.

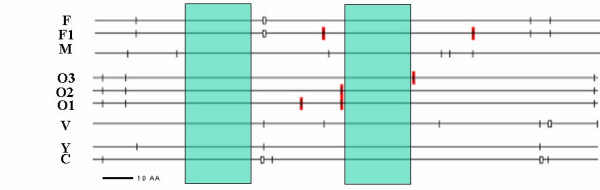

Interestingly a comparison of the sequences of different species reveals the existence of conserved regions and other very variable ones; this inter-specific variation is exhibited in Figure 2. Table 2 gives details of the analysed isolates.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the 181 amino acid sequence variation (each different marks correspond to one amino acid change). F, F1, M, V, O1, O2, O, Y and C correspond to the sequence identified in the study (see result). The conserved regions of the Plasmodium pLDH gene for all species are highlighted in green.

Table 2.

Result of the sequence analysis for the isolates tested in this paper.

| ID Code | Year | species | Origin | Seq | AA |

| 5353A | 2005 | PF | South Africa | F | F |

| 5353B | 2005 | PF | South Africa | F | F |

| 5421 | 2005 | PF | Benin | F | F |

| 5445 | 2005 | PF | Brazil | F | F |

| 4899 | 2004 | PF | Burkina Faso | F | F |

| CAMBF | 2001 | PF | Cambodia | F | F |

| 5203 | 2005 | PF | Cameroon | F | F |

| 5848 | 2005 | PF | Cap Verde | F | F |

| 5265 | 2005 | PF | Republic of Central Africa | F | F |

| 3414 | 2002 | PF | Colombia | F | F |

| 4682 | 2004 | PF | Comoros | F | F |

| 5405 | 2005 | PF | Congo | F | F |

| 4919 | 2004 | PF | Ivory Cost | F | F |

| 5600 | 2005 | PF | Dominican Republic | F | F |

| 1628 | 1999 | PF | Ecuador | F | F |

| 5648 | 2005 | PF | Gabon | F | F |

| 5083 | 2004 | PF | Gambia | F | F |

| 5094 | 2004 | PF | Ghana | F | F |

| 5898 | 2005 | PF | Guinea | F | F |

| 5339 | 2005 | PF | Equatorial Guinea | F | F |

| FguyF | 2003 | PF | French Guiana | F | F |

| 5555 | 2005 | PF | Haiti | F | F |

| 5745 | 2005 | PF | India | F | F |

| 2038 | 2000 | PF | Kenya | F | F |

| 4548 | 2004 | PF | Liberia | F | F |

| 4609 | 2004 | PF | Madagascar | F | F |

| 2686 | 2001 | PF | Malaysia | F | F |

| 5296 | 2005 | PF | Malawi | F | F |

| 5173 | 2004 | PF | Mali | F | F |

| 5793 | 2005 | PF | Mali | F | F |

| 4807 | 2004 | PF | Mauritania | F | F |

| 4629 | 2004 | PF | Mozambique | F | F |

| 5323 | 2005 | PF | Namibia | F | F |

| 5822 | 2005 | PF | Niger | F | F |

| 4582 | 2004 | PF | Nigeria | F | F |

| 5846 | 2005 | PF | Pakistan | F | F |

| 1317 | 1998 | PF | Papua New Guinea | F | F |

| 5225 | 2005 | PF | Sao Tome | F | F |

| 4838A | 2004 | PF | Senegal | F | F |

| 4512 | 2004 | PF | Sierra Leone | F | F |

| 4764 | 2004 | PF | Sir Lanka | F | F |

| 4562 | 2004 | PF | Sudan | F | F |

| 5224 | 2005 | PF | Tanzania | F | F |

| 5647 | 2005 | PF | Chad | F | F |

| 604 | 1997 | PF | Thailand | F | F |

| 4751A | 2004 | PF | Togo | F | F |

| 4751B | 2004 | PF | Togo | F | F |

| 542 | 1997 | PF | Yemen | F | F |

| 5197 | 2005 | PF | Congo Democratic Republic | F | F |

| ID Code | Year | species | Origin | Seq | AA |

| Plasmodium malariae | |||||

| CAMBM | 2001 | PM | Cambodia | M2 | M |

| 3413 | 2002 | PM | Cameroon | M3 | M |

| 4739 | 2004 | PM | Cameroon | M3 | M |

| 5990 | 2006 | PM | Cameroon | M3 | M |

| 1909 | 1999 | PM | Republic of Central Africa | M3 | M |

| 3670 | 2002 | PM | Comoros | M3 | M |

| 4014 | 2003 | PM | Comoros | M3 | M |

| 1548 | 1999 | PM | Congo | M3 | M |

| 2667 | 2001 | PM | Ivory Cost | M3 | M |

| 5041 | 2004 | PM | Ivory Cost | M3 | M |

| 4568 | 2004 | PM | French Guiana | M3 | M |

| 4774 | 2004 | PM | Madagascar | M3 | M |

| 516 | 1997 | PM | Senegal | M3 | M |

| 1018 | 1998 | PM | Togo | M3 | M |

| 2389 | 2000 | PM | Congo Democratic Republic | M3 | M |

| Plasmodium ovale | |||||

| 5894 | 2005 | PO | Angola | O2 | O2 |

| CAMBO | 2001 | PO | Cambodia | O2 | O2 |

| 3044 | 2001 | PO | Republic of Central Africa | O2 | O2 |

| 5979 | 2006 | PO | Ivory Cost | O2 | O2 |

| 3149 | 2002 | PO | Gabon | O2 | O2 |

| 4646 | 2004 | PO | Guinea | O2 | O2 |

| 3740 | 2002 | PO | Congo Democratic Republic | O2 | O2 |

| 4419 | 2003 | PO | Cameroon | O3 | O3 |

| 5401 | 2005 | PO | Madagascar | O3 | O3 |

| 2132 | 2000 | PO | Mali | O3 | O3 |

| 5994 | 2006 | PO | Mali | O3 | O3 |

| 2668 | 2001 | PO | Rwanda | O3 | O3 |

| 3043 | 2001 | PO | Zimbabwe | O3 | O3 |

| Plasmodium vivax | |||||

| 3019 | 2001 | PV | French Guiana | V1 | V |

| 1977 | 2000 | PV | India | V1 | V |

| 1866 | 1999 | PV | Nicaragua | V1 | V |

| 800 | 1997 | PV | Thailand | V1 | V |

| 2642 | 2001 | PV | Madagascar | V2 | V |

| 5315 | 2005 | PV | Chine | V3 | V |

| CAMBV | 2001 | PV | Cambodia | V4 | V |

| 5753 | 2005 | PV | Comoros | V4 | V |

| 1173 | 1998 | PV | Laos | V4 | V |

| ID Code | species | Origin | Seq | AA | |

| Reference strains | |||||

| 3D7 | PF | pf13_0141 | F | F | |

| FCC1/HN | PF | dq825436 | F1 | F | |

| EMBL | PM | ay486059 | M1 | M | |

| EMBL | PO | ay486058 | O1 | O1 | |

| EMBL | PV | ay486060 | V1 | V | |

| YOELII | PY | xm_719008 | Y | Y | |

| CHABAUDI | PC | xm_740087 | C | C | |

| BERGHEI | PB | ay437808 | B | Y | |

| REICHNOWII | PR | ab122147 | R | F | |

Seq = Nucleotide sequence, AA = aminoacid sequence

Discussion

Here is described, for the first time, the sequence variability of pLDH in the four human's species of malaria and four animal Plasmodium species and analysed them together with published sequences. The results indicate the existence of both variable and conserved regions in plasmodial lactate dehydrogenase.

The intra-specific geographic conservation of pLDH suggests that genetic variability may not be linked to disparities in sensitivities or specificities observed in the detection of P. falciparum [3] with anti-pan LDH antibodies. The falciparum-specific epitope detected by RDTs is probably situated in the inter-specific variable regions we have identified; whilst the pan-malarial epitope is more likely situated in a conserved region. However, Moody et al. [2] reported that one pan-specific monoclonal antibody used in a pLDH RDT has a lower affinity to P. malariae and P. ovale antigens, the attribution of this to a sequence divergence must not be neglected and should be further investigated.

Conclusion

The WHO states: "Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) offer the potential to provide accurate diagnosis to all at risk populations (...) The success of RDTs in malaria control will depend on good quality planning and implementation" [9]. Moreover a rapid diagnostic test needs to be reliable globally, to detect an antigen that mirrors accurately blood parasitaemia; therefore part of a good quality assurance is to monitor such factors.

As part of this quality assurance, we have identified that an intra-specific genetic variability is not a significant factor in the variation of efficiency observed in rapid diagnostic tests in the detection of P. falciparum, P vivax and P. malariae, although it may explain the poor sensitivity to P. ovale [7]. Similar findings of low variability have been demonstrated for plasmodial aldolase another target antigen of MRDTs [10] despite a bad sensitivity in the dectection of P. ovale infection [11] in contrast to HRP2, a target antigen of P. falciparum with high variability affecting MRDT sensitivity. In this regard, pLDH offers advantages as a target antigen for diagnosis. The identification of pan-specific and species-specific regions may help in development of more sensitive and specific monoclonal antibodies for MRDTs.

Authors' contributions

FA, DB, JLB and SH designed the study and contribute to the discussion. SH, JLB, EL and FA provide specimens for sequencing. SY, AMT, EL, VH and LD process samples and analysed the data. AMT write the first draft of the manuscript, then EL, SH, JLB, FA, DB critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This Work has been supported by a WHO grant and is part of the Modipop Project (Institut Pasteur de Paris).

Contributor Information

Arthur M Talman, Email: arthurtalman@yahoo.co.uk.

Linda Duval, Email: linda@pasteur-kh.org.

Eric Legrand, Email: elegrand@pasteur-cayenne.fr.

Véronique Hubert, Email: hubevero@yahoo.fr.

Seiha Yen, Email: seihayen@pasteur-kh.org.

David Bell, Email: belld@wpro.who.int.

Jacques Le Bras, Email: jacques.lebras@gmail.com.

Frédéric Ariey, Email: fariey@pasteur-kh.org.

Sandrine Houze, Email: sandrine.houze@bch.aphp.fr.

References

- Snow RW, Eckert E, Teklehaimanot A. Estimating the needs for artesunate-based combination therapy for malaria case-management in Africa. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:363–369. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(03)00168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody A, Hunt-Cooke A, Gabbett E, Chiodini P. Performance of the OptiMAL® malaria antigen capture dipstick for malaria diagnosis and treatment monitoring at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, London. Br J Haematol. 2000;109:891–894. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CK, Bell D, Gasser RA, Wongsrichanalai C. Rapid diagnostic testing for malaria. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:876–883. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WM, Yowell CA, Hoard A, Vander Jagt TA, Hunsaker LA, Deck LM, Royer RE, Piper RC, Dame JB, Makler MT, VanderJagt DL. Comparative structural analysis and kinetic properties of lactate dehydrogenases from the four species of human malarial parasites. Biochem. 2004;43:6219–6229. doi: 10.1021/bi049892w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper R, Lebras J, Wentworth L, Hunt-Cooke A, Houze S, Chiodini P, Makler M. Immunocapture diagnostic assays for malaria using Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase (pLDH) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:109–114. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J, McCarthy J, Gatton M, Kyle DE, Belizario V, Luchavez J, Bell D, Cheng Q. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 (PfHRP2) and its effect on the performance of PfHRP2-based rapid diagnostic tests. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:870–877. doi: 10.1086/432010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody A. Rapid diagnostic tests for malaria parasites. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:66–78. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.1.66-78.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snounou G. Detection and Identification of the four malaria parasite species Infecting humans by PCR amplification. Methods Mol Biol. 1996;50:263–291. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-323-6:263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Meeting Report Informal Consultation on Field Trials and Quality Assurance on Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Tests, WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Regional Office for the Western Pacific MALARIA RAPID DIAGNOSIS. 2003. http://www.who.int/malaria/rdt.html

- Lee N, Baker J, Bell D, McCarthy J, Cheng Q. Assessing the genetic diversity of the aldolase genes of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax and its potential effect on the performance of Aldolase-detecting Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4547–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01611-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigaillon C, Fontan E, Cavallo JD, Hernandez E. Ineffectiveness of the Binax NOW Malaria test for diagnosisof Plasmodium ovale Malaria. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;3:1011. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.1011.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]