Abstract

HilA activates the transcription of genes on Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1), which encodes a type III secretion system (TTSS). Previous studies showed that transposon insertions in orgC, a gene located on SPI1, increase hilA expression. We characterize the orgC gene product and show that it is secreted via the SPI1 TTSS. We propose a model whereby OrgC functions as a secreted repressor of the SPI1 virulence genes.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium uses a type III secretion system (TTSS) encoded on Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1) to secrete and translocate virulence proteins into host cells during the intestinal phase of infection (12, 26, 40). Effector proteins secreted via the SPI1 TTSS are encoded both within SPI1 (AvrA, SptP, SipA, SipB, and SipC) (5, 11, 14, 20,) and outside of SPI1 (SopA, SopB, SopE, SopE2, SspH1, and SlrP) (16, 30, 32, 34, 35, 36). Members of a subset of these translocated effector proteins cause cytoskeletal rearrangements, membrane ruffling, and macropinocytosis in epithelial cells, resulting in bacterial uptake or invasion (10).

The SPI1 type III secretion (TTS) apparatus is composed of at least 15 different Inv, Spa, Prg, and Org proteins that are encoded in several large operons on SPI1 (23). Mutation of the corresponding inv, spa, prg, and org genes on SPI1 abolish secretion and translocation of the effector proteins (references 22 and 33 and references therein). Translocation of serovar Typhimurium effectors also requires the sipB, sipC, and sipD genes on SPI1 (20, 21). SipB, SipC, and SipD are secreted via the SPI1 TTS apparatus and are believed to form a translocation pore in the host cell membrane which allows effector proteins to pass directly into the host cell cytosol (5, 18, 35).

Production of the SPI1 TTSS and many of its secreted effectors requires several transcriptional regulators, such as HilA and InvF, that are encoded on SPI1 (2, 6, 28). HilA is an OmpR-ToxR family member that directly activates SPI1 genes encoding components of the TTS apparatus by binding upstream of the invF and prgH genes (27). InvF directly activates SPI1 and non-SPI1 genes that encode many of the effector proteins that are secreted via the SPI1 TTSS (6, 8). Oxygen, osmolarity, and pH have been shown to regulate expression of the SPI1 TTSS by modulating hilA transcription (28, 29).

orgC, a gene on SPI1, has been speculated to play a role in regulating hilA expression. Transposon insertions in orgC were reported to increase expression of a hilA-lacZ fusion (9). In this study, we confirm previous results showing that orgC is not required for protein secretion by the SPI1 TTSS (22) and further demonstrate that orgC is not required for translocation of SipA and SptP into HEp-2 cells. We identify the orgC gene product and show that it is secreted via the SPI1 TTSS. Furthermore, using the Elk tag reporter system, we did not detect the translocation of OrgC into HEp-2 cells.

Construction and phenotypic analysis of a serovar Typhimurium orgC deletion mutant.

The orgC gene, located on SPI1 immediately downstream of orgB in the prgHIJKorgABC operon (22), encodes a putative protein of 161 amino acids. OrgC has previously been shown to be dispensable for secretion of serovar Typhimurium effectors and for invasion of epithelial cells by serovar Typhimurium (22). In order to characterize additional phenotypes of an orgC mutant, we constructed an in-frame nonpolar deletion in orgC that eliminated the coding region for amino acids 16 to 103 using the PCR-ligation-PCR technique (1) and primers 5′-TTTTCTAGAGTCATAGGAAACTTCCAGTGA-3′, 5′-TTTGGTACCTGAGCAGCAAACGGCTATGCT-3′, 5′-TTTGGTACCAAACCCGGTATCACCTTATAA-3′, and 5′-TTTGATATCTACCGTCCCCGCTTTCGCCTG-3′. The amplified product containing the deletion within orgC was inserted into the XbaI and SalI sites of the suicide vector pMAK407 (13), generating plasmid pMAK-orgC. Plasmid pMAK-orgC was utilized to move the orgC deletion into the chromosome of serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344 (17). Briefly, pMAK-orgC was electroporated into SL1344, and bacteria that had integrated the plasmid into the chromosome by homologous recombination were selected for their resistance to chloramphenicol at 42°C. After passage under nonselective conditions, clones that had resolved the cointegrate by excision of the plasmid sequences were screened for by their sensitivity to chloramphenicol and were tested for the presence of the deletion by PCR and restriction endonuclease digestion. Serovar Typhimurium strain JD98 was determined to contain the correct deletion in orgC.

The secretion phenotype of the orgC deletion mutant JD98 was analyzed by measuring the secretion of epitope-tagged versions of SipA and SptP. Plasmid pSptP-Elk, which expresses the full-length SptP protein (amino acids 1 to 543) fused to the Elk tag, was constructed by PCR methods. The Elk tag, encoding the SV40 large tumor antigen nuclear localization signal fused in-frame to amino acids 375 to 392 of the Elk-1 eucaryotic transcription factor, was amplified using primers 5′-TTTATGCATGCGGAATTAATTCCCGAGCCT-3′ and 5′-TTTCTCGAGTGACTTGGCCGGGCTACGGGG-3′ carrying NsiI and XhoI sites (underlined), respectively (7). The resulting Elk tag fragment was digested with XhoI and inserted into EcoRV- and XhoI-digested plasmid pBluescript SK(−) (Stratagene), generating plasmid pELK6. The DNA fragment encoding the full-length SptP and its chaperone SicP were amplified using primers 5′-TTTGGATCCTTCAAGAGGAAAGTAAATTGC-3′ and 5′-TTTATGCATGCTTGCCGTCGTCATAAGCAA-3′, digested with BamHI and NsiI, and ligated in-frame into the BamHI and NsiI sites of pELK6, generating plasmid pSptP-Elk. Plasmid pSipA-Elk, which expresses the full-length SipA protein (amino acids 1 to 685) fused to the hemagglutinin and Elk tags, was constructed by PCR amplification of the DNA sequence encoding the Elk tag using primers 5′-TTTGAATTCTGCGGAATTAATTCCCGAG-3′ and 5′-TTTGAATTCTTCTTGGCCGGGCTACGGGG-3′. The Elk tag fragment was digested with EcoRI and inserted into the EcoRI site of pAJK68C (25), a derivative of pBH that encodes a hemagglutinin-tagged version of SipA expressed from the tac promoter, generating pSipA-Elk.

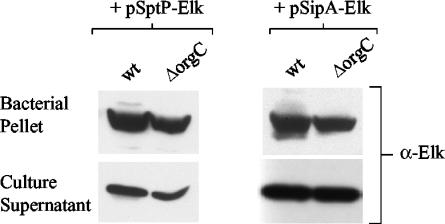

The serovar Typhimurium wild-type (wt) SL1344 strain and the orgC deletion mutant, JD98 (ΔorgC), carrying pSipA-Elk or pSptP-Elk, were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (0.5% Bacto-yeast extract, 1% Bacto-tryptone, 1% NaCl) under limited aeration conditions at 37°C, conditions previously shown to promote the induction of the SPI1 TTS genes (2, 28). Secretion of SipA-Elk and SptP-Elk into bacterial culture supernatants was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting using antiserum specific for the Elk tag (α-Elk) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, Mass.) (Fig. 1). The orgC deletion mutant secreted SipA-Elk and SptP-Elk at levels comparable to the those for the wt strain, confirming that OrgC is not required for the secretion of serovar Typhimurium effectors (22). These data also show that addition of the Elk tag to the carboxyl terminus of SipA or SptP did not disrupt the expression or secretion of these hybrid proteins.

FIG. 1.

Expression and secretion of SptP-Elk and SipA-Elk by the orgC deletion mutant. Bacterial cell pellet and culture supernatant fractions of serovar Typhimurium SL1344 (wt) and the orgC deletion mutant JD98 (ΔorgC) carrying pSptP-Elk or pSipA-Elk were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis using Elk-1 antipeptide antibodies (α-Elk).

Use of the ELK tag system to detect translocation of serovar Typhimurium effectors into HEp-2 cells.

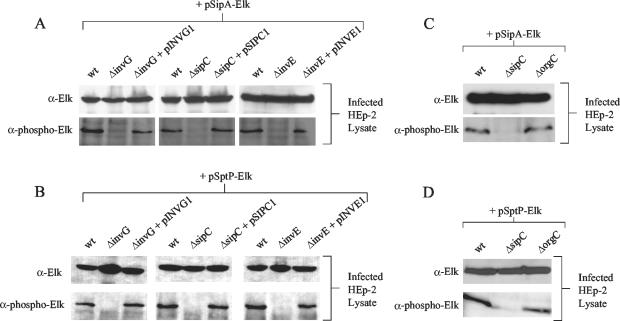

The ELK tag reporter system was originally developed to detect the translocation of Yersinia pestis proteins into mammalian cells (7). The reporter system utilizes a small bipartite phosphorylatable peptide tag, termed the Elk tag. Translocation of an Elk-tagged protein into eukaryotic cells results in host cell protein kinase-dependent phosphorylation of the tag at a specific serine residue, which can subsequently be detected with phospho-specific antibodies. To determine whether the Elk-tagged SipA and SptP hybrids could be translocated into HEp-2 cells and phosphorylated at Elk-1 serine 383, we infected HEp-2 monolayers with serovar Typhimurium SL1344 carrying pSipA-Elk or pSptP-Elk, essentially as described for infections of HeLa cells with Y. pestis, except that no phosphatase or protease inhibitors were used (7). Serovar Typhimurium cultures were grown for 3 h to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0 and used to infect HEp-2 cell monolayers at a multiplicity of infection of 30 bacteria per HEp-2 cell. After 3.5 h of infection at 37°C, the tissue culture medium was discarded, and the HEp-2 cell monolayer was lysed by the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Protein lysates from infected HEp-2 cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the Elk-1 and phospho-specific Elk-1 antibody preparations (Cell Signaling Technology). The Elk-1 antibody detects total Elk-tagged proteins, independent of their phosphorylation state, while the phospho-specific Elk-1 antibody detects only Elk-tagged proteins that are phosphorylated at Elk-1 serine 383. As shown in Fig. 2, the Elk-1 antibody (α-Elk) and the phospho-specific Elk-1 antibody (α-phospho-Elk) detected the SipA-Elk and SptP-Elk proteins in HEp-2 lysates infected with SL1344 (wt) carrying pSipA-Elk and pSptP-Elk, respectively. These results indicate that SipA-Elk and SptP-Elk were translocated and phosphorylated in the HEp-2 cells.

FIG. 2.

Translocation and phosphorylation of SipA-Elk and SptP-Elk during infections of HEp-2 cells. (A and B) The wt serovar Typhimurium SL1344 strain (wt), invG deletion mutant AJK61 (ΔinvG), sipC deletion mutant JD15 (ΔsipC), invE deletion mutant JD91 (ΔinvE), and each mutant complemented with pINVG1, pSIPC1, or pINVE1, respectively, were transformed with pSipA-Elk (A) or with pSptP-Elk (B) and used to infect HEp-2 cells. Infected HEp-2 cell lysates were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with Elk-1 antipeptide antibodies (α-Elk) and Elk-1 phospho-specific antibodies (α-phospho-Elk). (C and D) The wt serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344 (wt), the sipC deletion mutant JD15 (ΔsipC), and the orgC deletion mutant JD98 (ΔorgC) carrying pSipA-Elk (C) or pSptP-Elk (D) were used to infect HEp-2 cells, which were analyzed as described above.

In order to test whether phosphorylation of the Elk-tagged proteins depends on components of the SPI1 TTS apparatus and translocation pore, known to be required for secretion and translocation of SPI1 effector proteins, respectively, we measured SipA-Elk and SptP-Elk translocation in serovar Typhimurium strains defective in invG, sipC, and invE. invG encodes a component of the SPI1 TTS apparatus, and sipC encodes a component of the putative translocation pore (19, 21). InvE is required for translocation of serovar Typhimurium effectors into mammalian cells, although it is not thought to be a component of the TTS apparatus or translocation pore (24). In-frame deletions in sipC, eliminating the coding region for amino acids 1 to 251, and in invE, eliminating the coding region for amino acids 9 to 225, were constructed using the PCR-ligation-PCR technique (1) (details available upon request). An in-frame deletion in invG was constructed by removing the 517-bp HindIII fragment internal to invG, blunting the ends with Vent DNA polymerase, and ligating the blunt ends to form a 513-bp deletion in the invG open reading frame. The invG, sipC, and invE deletion mutations were introduced into the SL1344 chromosome using pMAK705 derivatives, as described above (13). Complementing plasmids pINVG1, pSIPC1, and pINVE1 were constructed, which express the full-length InvG, SipC, and InvE proteins, respectively, from an arabinose-inducible promoter (details available upon request).

As shown in Fig. 2A and B, the invG mutant (AJK61), sipC mutant (JD15), and invE mutant (JD91) expressed SipA-Elk and SptP-Elk at levels comparable to that of the wt strain; however, neither hybrid protein was detected using the phospho-specific Elk-1 antibody (α-phospho-Elk) in cells infected with any of the mutant strains. Complementation of the invG, sipC, and invE mutant defects with plasmids pINVG1, pSIPC1, and pINVE1 (Fig. 2A and B) demonstrate that the phosphorylation of SipA-Elk and SptP-Elk in HEp-2 cells requires that they be delivered from both secretion- and translocation-competent serovar Typhimurium.

Translocation phenotype of the orgC deletion mutant.

The translocation phenotype of the orgC deletion mutant JD98 (ΔorgC) was analyzed by measuring the translocation of Elk-tagged SipA and SptP into HEp-2 cells. The Elk-1 (α-Elk) antibody detected comparable amounts of both the SipA-Elk and SptP-Elk proteins in lysates of HEp-2 cells infected with SL1344 (wt) and the orgC deletion mutant JD98 (ΔorgC), indicating that the Elk-tagged proteins were expressed equally in these strains during the infection (Fig. 2C and D). The phospho-specific Elk-1 antibody (α-phospho-Elk) also detected SipA-Elk and SptP-Elk in lysates of HEp-2 cells infected with the orgC deletion mutant JD98 (ΔorgC) at levels comparable to that in lysates of cells infected with the wt strain (Fig. 2C and D). The sipC deletion mutant JD15 (ΔsipC) was used as a translocation-defective control. These data indicate that OrgC is not required for translocation of serovar Typhimurium effectors into HEp-2 cells.

Identification and localization of the OrgC-Elk protein.

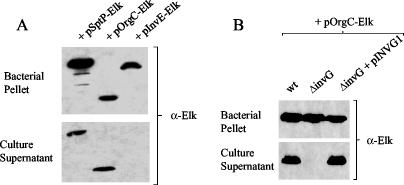

In order to identify and localize the OrgC protein, we constructed plasmid pOrgC-Elk, which expresses carboxyl-terminal Elk-tagged OrgC. Plasmid pOrgC-Elk was constructed by PCR amplification of the DNA fragment encoding full-length orgC using primers 5′-TTTGATATCTACCGTCCCCGCTTTCGCCTG-3′ and 5′-TTTGAATTCCCAGTCAATTGCCTCTTTGTT-3′. The amplified product was digested with PvuII and EcoRI and inserted into SmaI- and EcoRI-digested pELK6, generating pOrgC-Elk. SptP-Elk was used as a positive secretion control. InvE, a cytoplasmic protein, was used as a negative secretion control (24). Plasmid pInvE-Elk, which expresses a carboxyl-terminal Elk tag fused to full-length InvE, was constructed by amplification of the DNA fragment encoding full-length invE using primers 5′-TTTGGATCCCTGATTGGGGAACGTAATGTG-3′ and 5′-TTTGAATTCAGACAGCTTTTCAATAGTACG-3′. The amplified product was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and inserted into BamHI- and EcoRI-digested pELK6, generating pInvE-Elk.

Plasmids pSptP-Elk, pOrgC-Elk, and pInvE-Elk, encoding SptP-Elk, OrgC-Elk, and InvE-Elk, respectively, were transformed into wt serovar Typhimurium SL1344, and the expression and secretion of the Elk-tagged proteins were determined after 6 h of growth in LB medium at 37°C. The Elk-1 antibody (α-Elk) detected SptP-Elk, OrgC-Elk, and InvE-Elk in the bacterial cell pellet fraction in comparable amounts, indicating that each of the Elk-tagged proteins was efficiently expressed (Fig. 3A). As expected, the Elk-1 antibody failed to detect InvE-Elk in the culture supernatant fractions; however, OrgC-Elk was readily detected by the Elk-1 antibody in the culture supernatant fraction, as was SptP-Elk. These data suggest that OrgC is secreted by serovar Typhimurium.

FIG. 3.

(A) Identification and localization of Elk-tagged SptP, OrgC, and InvE. Bacterial cell pellet and culture supernatant fractions from serovar Typhimurium SL1344 carrying pSptP-Elk, pOrgC-Elk, or pInvE-Elk were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with Elk-1 antipeptide antibodies (α-Elk). (B) Requirement of invG for secretion of Elk-tagged OrgC. Bacterial cell pellet and culture supernatant fractions from serovar Typhimurium SL1344 (wt), the invG deletion mutant AJK61 (ΔinvG), and the invG deletion mutant (ΔinvG) complemented with pINVG1, all transformed with pOrgC-Elk, were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with Elk-1 antipeptide antibodies (α-Elk).

In order to determine whether OrgC secretion is dependent upon a functional serovar Typhimurium SPI1 TTSS, serovar Typhimurium SL1344 (wt), the TTS-defective invG deletion mutant AJK61 (ΔinvG) and the invG deletion mutant complemented with pINVG1 were transformed with plasmid pOrgC-Elk and grown in LB media containing 0.02% arabinose for 6 h at 37°C. The amount of Elk-tagged OrgC present in the bacterial cell pellet and culture supernatant fractions from each strain was determined by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the Elk-1 antibody (α-Elk) (Fig. 3B). The Elk-1 antibody detected OrgC-Elk in the bacterial cell pellet fraction from serovar Typhimurium SL1344 (wt), the invG deletion mutant AJK61 (ΔinvG), and the invG deletion mutant complemented with pINVG1 in comparable amounts, indicating that OrgC-Elk was efficiently expressed in each of these strains. The Elk-1 antibody readily detected OrgC-Elk in the culture supernatant fractions from serovar Typhimurium SL1344 (wt) and the invG deletion mutant complemented with pINVG1 but not in the invG deletion mutant (ΔinvG). These data indicate that OrgC is secreted via the serovar Typhimurium SPI1 TTS apparatus.

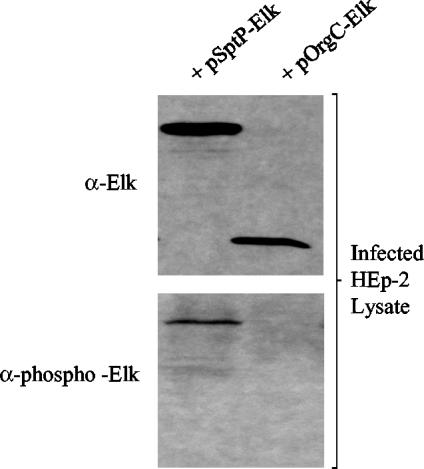

Translocation of OrgC-Elk into HEp-2 cells is not detectable.

Previous studies have shown that several SPI1-encoded proteins are not only secreted via the TTSS but are also translocated into mammalian cells (23, 26). To examine whether OrgC can be translocated by serovar Typhimurium into HEp-2 cells, we infected HEp-2 cell monolayers with wt serovar Typhimurium SL1344 carrying plasmids pSptP-Elk and pOrgC-Elk. As shown in Fig. 4, the Elk-1 antibody (α-Elk) detected both the SptP-Elk and OrgC-Elk proteins in the HEp-2 cell lysates, indicating that the Elk-tagged proteins were expressed during the infection. However, only SptP-Elk was detected in the HEp-2 cell lysates using the phospho-specific Elk-1 antibody (α-phospho-Elk). These data suggest that either OrgC is not translocated into HEp-2 cells or the Elk reporter system failed to detect the translocation of OrgC into HEp-2 cells.

FIG. 4.

Translocation and phosphorylation of SptP-Elk and OrgC-Elk during infections of HEp-2 cells. The wt Typhimurium strain SL1344 carrying either pSptP-Elk or pOrgC-Elk was used to infect HEp-2 cells, which were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with Elk-1 antipeptide antibodies (α-Elk) and Elk-1 phospho-specific antipeptide antibodies (α-phospho-Elk).

Possible functions of OrgC.

Previous studies using transposon mutations showed that orgC is not required for secretion of serovar Typhimurium effector proteins or for invasion of serovar Typhimurium into epithelial cells (22). We constructed an in-frame nonpolar deletion in the orgC gene in serovar Typhimurium SL1344 and confirmed the absence of an invasion phenotype in HEp-2 and RAW 264.7 cells (data not shown). Consistent with this phenotype, we also showed that Elk-tagged SipA and SptP are secreted and translocated into HEp-2 cells from the orgC deletion mutant in amounts comparable to those for the wt strain. By constructing and characterizing an Elk-tagged OrgC, we discovered that OrgC can be secreted via the SPI1 TTSS; however, we did not detect the translocation of OrgC-Elk into Hep-2 cells using the Elk reporter system.

Homology searches in databases have failed to uncover sequence similarities to the OrgC protein. However, the position of the orgC gene on SPI1, immediately downstream of orgA and orgB in the prgHIJKorgABC operon, corresponds to the position of the lcrQ gene in the yscBCDEFGHIJKLlcrQ operon of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis virulence plasmid, which lies immediately downstream of the orgA and orgB homologs, yscK and yscL, respectively. Interestingly, the lcrQ gene product has previously been shown to function as a transcriptional repressor of the Y. pseudotuberculosis yop genes (31). During bacterial contact with a mammalian cell, LcrQ is secreted via the Y. pseudotuberculosis Ysc TTSS, thereby decreasing the intracellular concentration of LcrQ and resulting in increased expression of the yop genes. Mutations in the lcrQ gene result in the constitutive expression of yop genes, even prior to contact with mammalian cells (31). The position of the orgC gene on SPI1, the increase in hilA expression in an orgC mutant (9), and our results showing the secretion of the orgC gene product all point to the possibility that OrgC may function similarly to the Y. pseudotuberculosis negative regulator LcrQ.

It is also conceivable that OrgC plays a role as an effector protein that acts in the extracellular environment. Examples of serovar Typhimurium effectors that function extracellularly include SipA, which has been hypothesized to mediate the induction of polymorphonuclear leukocyte transmigration to the site of infection in the host by interacting with receptors on the surfaces of epithelial cells (25). Alternatively, OrgC may be translocated into host cells, but in minute amounts which the Elk reporter system failed to detect. In fact, the Y. pseudotuberculosis LcrQ protein has been shown to be translocated into host cells (4). In this case, OrgC may also exert an intracellular function that is redundant or that is unrelated to the invasion phenotype. The lack of an invasion phenotype for mutants that lack individual effector proteins is not unprecedented. Indeed, SopB, SopE, SopE2, SipA, and SptP have all been shown to alter the actin cytoskeleton of epithelial cells but are all dispensable for the invasion phenotype (3, 11, 15, 32, 37, 38, 39).

Acknowledgments

We thank Sumita Jain for conducting invasion assays and Aaron J. Kelly for constructing strain AJK61.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI3344.

Editor: B. B. Finlay

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali, S. A., and A. Steinkasserer. 1995. PCR-ligation-PCR mutagenesis: a protocol for creating gene fusions and mutations. BioTechniques 18:746-750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajaj, V., R. L. Lucas, C. Hwang, and C. A. Lee. 1996. Coordinate regulation of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes by environmental and regulatory factors is mediated by control of hilA expression. Mol. Microbiol. 22:703-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakshi, C. S., V. P. Singh, M. W. Wood, P. W. Jones, T. S. Wallis, and E. E. Galyov. 2000. Identification of SopE2, a Salmonella secreted protein which is highly homologous to SopE and involved in bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 182:2341-2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cambronne, E. D., L. W. Cheng, and O. Schneewind. 2000. LcrQ/YscM1, regulators of the Yersinia yop virulon, are injected into host cells by a chaperone-dependent mechanism. Mol. Microbiol. 37:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collazo, C. M., and J. E. Galán. 1997. The invasion-associated type III secretion system of Salmonella typhimurium directs the translocation of Sip proteins into host cells. Mol. Microbiol. 24:747-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darwin, K. H., and V. L. Miller. 1999. InvF is required for expression of genes encoding proteins secreted by the SPI1 type III secretion apparatus in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 181:4949-4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day, J. B., F. Ferracci, and G. V. Plano. 2003. Translocation of YopE and YopN into eukaryotic cells by Yersinia pestis yopN, tyeA, sycN, yscB and lcrG deletion mutants measured using a phosphorylatable peptide tag and phospho-specific antibodies. Mol. Microbiol. 47:807-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichelberg, K., and J. E. Galán. 1999. Differential regulation of Salmonella typhimurium type III secreted proteins by pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1)-encoded transcriptional activators InvF and HilA. Infect. Immun. 67:4099-4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fahlen, T. F., N. Mathur, and B. D. Jones. 2000. Identification and characterization of mutants with increased expression of hilA, the invasion gene transcriptional activator of Salmonella typhimurium. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 28:25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis, C. L., T. A. Ryan, B. D. Jones, S. J. Smith, S. Falkow. 1993. Ruffles induced by Salmonella and other stimuli direct macropinocytosis of bacteria. Nature 364:639-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu, Y., and J. E. Galán. 1998. The Salmonella typhimurium tyrosine phosphatase SptP is translocated into host cells and disrupts the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Microbiol. 27:359-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galán, J. E. 1996. Molecular genetic bases of Salmonella entry into host cells. Mol. Microbiol. 20:263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton, C. M., M. Aldea, B. K. Washburn, P. Babitzke, and S. R. Kushner. 1989. New method for generating deletions and gene replacements in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:4617-4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardt, W. D., and J. E. Galán. 1997. A secreted Salmonella protein with homology to an avirulence determinant of plant pathogenic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:9887-9892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardt, W. D., L. M. Chen, K. E. Schuebel, X. R. Bustelo, and J. E. Galán. 1998. Salmonella typhimurium encodes an activator of Rho GTPases that induces membrane ruffling and nuclear responses in host cells. Cell 93:815-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong, K. H., and V. L. Miller. 1998. Identification of a novel Salmonella invasion locus homologous to Shigella ipgDE. J. Bacteriol. 180:1793-1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hueck, C. J., M. J. Hantman, V. Bajaj, C. Johnston, C. A. Lee, and S. I. Miller. 1995. Salmonella typhimurium secreted invasion determinants are homologous to Shigella Ipa proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 18:479-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hueck, C. J. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:379-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaniga, K., J. E. Bossio, and J. E. Galán. 1994. The Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes encode homologues of the AraC and PulD family of proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 13:555-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaniga, K., D. Trollinger, and J. E. Galán. 1995. Identification of two targets of the type III protein secretion system encoded by the inv and spa loci of Salmonella typhimurium that have homology to the Shigella IpaD and IpaA proteins. J. Bacteriol. 177:7078-7085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaniga, K., S. C. Tucker, D. Trollinger, and J. E. Galán. 1995. Homologues of Shigella IpaB and IpaC invasins are required for Salmonella typhimurium entry into cultured epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 177:3965-3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein, J. R., T. F. Fahlen, and B. D. Jones. 2000. Transcriptional organization and function of invasion genes within Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium pathogenicity island 1, including the prgH, prgI, prgJ, prgK, orgA, orgB and orgC genes. Infect. Immun. 68:3368-3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubori, T., A. Sukhan, S.-I. Aizawa, and J. E. Galán. 2000. Molecular characterization and assembly of the needle complex of the Salmonella type III protein secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10225-10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubori, T., and J. E. Galán. 2002. Salmonella type III secretion-associated protein InvE controls translocation of effector proteins into host cells. J. Bacteriol. 184:4699-4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, C. A., M. Silva, A. M. Siber, A. J. Kelly, E. Galyov, and B. A. McCormick. 2000. A secreted Salmonella protein induces a proinflammatory response in epithelial cells, which promotes neutrophil migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12283-12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lostroh, C. P., and C. A. Lee. 2001. The Salmonella pathogenicity island-1 type III secretion system. Microbes Infect. 3:1281-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lostroh, C. P., V. Bajaj, and C. A. Lee. 2000. The cis-requirements for transcriptional activation by HilA, a virulence determinant encoded on SPI1. Mol. Microbiol. 37:300-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas, R. L., and C. A. Lee. 2000. Unravelling the mysteries of virulence gene regulation in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1024-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucas, R. L., C. P. Lostroh, C. C. DiRusso, M. P. Spector, B. L. Wanner, and C. A. Lee. 2000. Multiple factors independently regulate hilA and invasion gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 182:1872-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miao, E. A., C. A. Scherer, R. M. Tsolis, R. A. Kingsley, L. G. Adams, A. J. Baumler, and S. I. Miller. 1999. Salmonella typhimurium leucine-rich repeat proteins are targeted to the SPI1 and SPI2 type III secretion systems. Mol. Microbiol. 34:850-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rimpilainen, M., A. Forsberg, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1992. A novel protein, LcrQ, involved in the low-calcium response of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis shows extensive homology to YopH. J. Bacteriol. 174:3355-3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stender, S., A. Friebel, S. Linder, M. Rohde, S. Mirold, and W. D. Hardt. 2000. Identification of SopE2 from Salmonella typhimurium, a conserved guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Cdc42 of the host cell. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1206-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sukhan, A., T. Kubori, J. Wilson, and J. E. Galán. 2001. Genetic analysis of assembly of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium type III secretion-associated needle complex. J. Bacteriol. 183:1159-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsolis, R. M., S. M. Townsend, E. A. Miao, S. I. Miller, T. A. Ficht, L. G. Adams, and A. J. Baumler. 1999. Identification of a putative Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium host range factor with homology to IpaH and YopM by signature-tagged mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 67:6385-6393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood, M. W., R. Rosqvist, P. B. Mullan, M. H. Edwards, and E. E. Galyov. 1996. SopE, a secreted protein of Salmonella dublin, is translocated into the target eucaryotic cell via a sip-dependent mechanism and promotes bacterial entry. Mol. Microbiol. 22:327-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood, M. W., M. A. Jones, A. M. Siber, B. A. McCormack, R. Rosqvist, T. S. Wallis, and E. E. Galyov. 2000. The secreted effector protein of Salmonella dublin, SopA, is translocated into eucaryotic cells and influences the induction of enteritis. Cell. Microbiol. 2:293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou, D., M. S. Mooseker, and J. E. Galán. 1999. Role of the S. typhimurium actin-binding protein SipA in bacterial internalization. Science 283:2092-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou, D., M. S. Mooseker, and J. E. Galán. 1999. An invasion-associated Salmonella protein modulates the actin-bundling activity of plastin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:10176-10181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou, D., L. L. H. Chen, B. S. Shears, and J. E. Galán. 2001. A Salmonella inositol polyphosphatase acts in conjunction with other bacterial effectors to promote host-cell actin cytoskeleton rearrangements and bacterial internalization. Mol. Microbiol. 39:248-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou, D., and J. E. Galán. 2001. Salmonella entry into host cells: the work in concert of type III secreted effector proteins. Microb. Infect. 3:1293-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]