Abstract

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., indomethacin) inhibit and reduce the fluid secretion responses elicited by cholera toxin (CT), but it has not been conclusively determined which cyclooxygenase (COX) isoform is involved in CT's action. This study evaluated the role of the COX enzymes and their arachidonic acid metabolites in experimental cholera. Swiss-Webster mice were dosed with celecoxib and rofecoxib and challenged with CT in ligated small intestinal loops, and intestinal segments from mice deficient in COX-1 and COX-2 were challenged with CT. The effects of CT on fluid accumulation, prostaglandin E2 production, mucosal tissue injury, and markers of oxidative stress were measured. Celecoxib and rofecoxib given at 160 μg per mouse inhibited CT-induced fluid accumulation by 48% and 31%, respectively, but there was no significant difference among cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− mice in response to CT compared to wild-type controls. CT elevated tissue levels of oxidized glutathione and lipid peroxides and elicited small intestinal tissue injury in two of five cox-1−/− and four of five cox-2−/− mice. A role for COX-2 in CT's mechanism of action has previously been suggested by the effectiveness of COX-2 inhibitors in reducing CT-induced fluid secretion, but CT challenge of COX-1 and COX-2 knockout mice did not corroborate the pharmacological data. The results of this study show that CT induced oxidative stress in COX-deficient mice and suggest a tissue-protective role for arachidonic acid metabolites in the small intestine against oxidative stress.

Diarrheal disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in many developing and tropical areas of the world. One leading cause of diarrheal diseases in developing countries such as Bangladesh is Vibrio cholerae. Cholera is a potentially life-threatening secretory diarrhea characterized by numerous, voluminous watery stools. The organism is a gram-negative, highly motile curved rod with a single polar flagellum. V. cholerae is transmitted via the fecal/oral route through ingestion of contaminated water or food washed in contaminated water. Colonization of the intestinal mucosa by V. cholerae involves motility, mucinase production, and adherence factors that enable the bacteria to adhere to the crypt epithelial cells in the small intestine.

Cholera toxin (CT), secreted from the bacteria, acts on intestinal epithelial cells, mediating the loss of water and electrolytes from the mucosa, a process that leads to electrolyte imbalance, hypovolemic shock, and death in severe cases. The B subunit binds to its membrane receptor GM1-ganglioside, allowing the internalized enzymatic A subunit to ADP-ribosylate the Gsα regulatory protein of adenylate cyclase (26). The resulting activation of adenylyl cyclase increases the synthesis of 3′,5′-AMP (cyclic AMP) in the intestinal epithelial cells and consequential stimulation of the enteric nervous system with the release of 5-hydroxytryptamine (4, 6, 10, 26, 30, 33).

The mechanism of action of CT has previously been shown to include the stimulation and synthesis of mucosal prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (35) by upregulating the expression of phospholipase activating protein (36), a reported activator of phospholipase A2 (7). CT-induced mobilization of arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids by phospholipase enzymes creates a substrate pool for the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes (e.g., COX-1 and COX-2) to convert arachidonic acid into prostaglandins (e.g., PGH2) (46). COX-1 is generally considered a constitutive enzyme and has been implicated in normal cellular homeostasis (46). COX-2 is a mitogen (20, 55)- and cytokine (42)-induced form of the enzyme associated with inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (47) and inflammatory bowel disease (27, 45).

Recent reports established that under certain conditions COX-1 expression is inducible (23), and COX-2 is constitutively expressed in tissues such as brain (56), kidney (14), and trachea (53). Recently, each COX enzyme has been reported to have a distinct subcellular localization and a functional coupling to constitutive and inducible membrane-associated prostaglandin E2 synthase enzymes (19, 28, 49), the enzymes responsible for the terminal conversion of PGH2 to PGE2, a biologically active prostaglandin shown to be an important mediator of water and electrolyte secretion (2, 18, 50-52). Prostaglandins formed as a result of arachidonic acid metabolism were initially thought to be the intracellular mediators through which CT might exert its initial effect on adenylyl cyclase (34). PGE2, when injected into the mesenteric arteries or into the intestinal lumen of rats, elicited a secretory response similar to CT's response (3).

The importance of the COX enzymes involved in arachidonic acid metabolism and the generation of PGE2 in experimental cholera has not been clearly defined. Numerous reports have shown that PGE2 is an important regulator of water and electrolyte transport (2, 18, 50-52), as well as a potent stimulator of the immune response through its effects on transcription of genes encoding cytokines, e.g., interleukin-6 (15, 39, 54), interleukin-8 (57), and interleukin-10 (48). Furthermore, PGE2 also contributes to the generation of additional cyclic AMP by stimulating adenylyl cyclase in several cell types through an interaction with its serpentine prostanoid receptors (8, 31, 41). This interaction between PGE2 and its receptors has also been implicated in the further upregulation of both isoforms of COX by their products (e.g., PGE2) (16, 17, 23).

Since CT is known to elicit an increase in PGE2 and has recently been shown to posttranscriptionally upregulate COX-2 expression (5), it has been hypothesized that COX enzyme activation and the generation of PGE2 are involved and important in the fluid secretion response elicited by CT. This report describes the use of cox gene knockout mice and COX-2 enzyme inhibitors in an experimental model of cholera to elucidate the role of the COX isozymes and PGE2 generation in the fluid secretion response to CT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

CT from Vibrio cholerae Inaba 569B was purchased from List Biological Laboratories, Inc. (Campbell, Calif.), and stored at 4°C at a concentration of 5 mg/ml in a buffered solution containing 0.05 M Tris, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.001 M disodium EDTA, and 0.003 M NaN3 at pH 7.5. A freshly prepared solution of 0.01 mg/ml was prepared in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for injection (0.1 ml) into the mouse intestinal loops. CT B-subunit (CTB) and lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli O111:B4 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.) and used at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. CT and CTB were determined to be free of endotoxin as measured by the E-Toxate kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.). Sutupak, a sterile 2-0 silk nonabsorbable surgical suture, obtained from Ethicon, Inc. (Somerville, N.J.), was used to construct the mouse intestinal loops.

Drugs.

Celecoxib (32) was purchased from Pharmacia, Peapack, N.J. Rofecoxib (40) was purchased from Merck and Company, Inc., Whitehouse Station, N.J. The drugs were solubilized in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide at 20 mg/ml and diluted to the indicated final concentration in PBS just prior to the experiment. The final dimethyl sulfoxide concentration in any sample was less than 5% of the total volume in the dose given to the mice to prevent any nonspecific effects of the solvent. Drug and solvent controls were included as indicated.

Mice.

For use in the ligated intestinal loop assays, adult female Swiss-Webster outbred mice weighing 25 to 30 g and 6 to 8 weeks old were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, N.Y.) and housed in the animal resource facility at UTMB in Galveston, Tex.. For additional experiments, groups of 6- to 8-week-old female cox-1−/− [C57BL/6;129P2(Ola)-Ptgs1tml] and cox-2−/− [C57BL/6;129P2(Ola)-Ptgs2tml] mice and heterozygote wild-type controls [C57BL/6;129P2(Ola)] developed by Robert Langebach at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in 1995 by homologous recombination gene targeting (21, 22, 24) were also purchased from Taconic Farms and housed in specific-pathogen-free facilities at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. All of the mice were given free access to water and food until just prior to the experiment. After necropsy of the animals, protein from intestinal tissue sections was obtained for Western analysis to confirm the identity of the cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− and C57BL/6;129P2(Ola) wild-type mice.

Ligated intestinal loop assay.

In multiple, independent experiments, Swiss-Webster or cox gene knockout and wild-type control female mice were allowed free access to fresh water, but food was withheld overnight to reduce the food content of the intestinal lumen. The following day, mice underwent ileal loop ligation as described by several laboratories, including ours, in numerous earlier reports (4, 33, 44). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with ether before a ventral midline incision was made in the abdominal wall to expose the small intestine. The small intestine was removed from the abdominal cavity, and a 6- to 9-cm segment of ileum located 1 to 2 cm below the duodenum was ligated with a 2-0 silk suture. A 0.1-ml solution containing 1 μg of CT in sterile PBS was injected into the lumen of the ligated segment with a 0.5-inch, 28-gauge, 0.5-ml Lo-Dose U-100 insulin syringe (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, N.J.).

In experiments with celecoxib and rofecoxib, each drug was injected either into the intestinal lumen along with CT or by the intraperitoneal route at the time of challenge. The intestinal segment was returned to the abdominal cavity, and the peritoneal cavity wall was closed with 9-mm wound clips and the MikRon Autoclip wound closure system (Becton Dickinson Primary Care Diagnostics, Sparks, Md.). The mice were allowed to recover for 6 h and then sacrificed by cervical dislocation. At the time of necropsy, ligated loops were removed from the abdominal cavity for collection of luminal fluid. In negative control animals, phosphate-buffered saline (0.5 to 1.0 ml) was washed through the intestinal segment to collect luminal PGE2, leukotriene B4 (LTB4), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). Fluid accumulation data are shown as mean fluid concentration plus or minus one standard error and were analyzed by Dunnett's multiple group comparison test with SigmaStat statistical analysis software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill.).

Histopathology.

Ligated intestinal segments (1 cm) from CT-challenged and control cox gene knockout mice were removed from the abdominal cavity and preserved in a buffered 4% formaldehyde solution. Semithin tissue sections were mounted on glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (VelLab, Inc., Houston, Tex., or the Histopathology Core Facility at the University of Texas Medical Branch). CT-induced tissue injury was examined by light microscopy. Coded slides of CT-challenged and control tissues were independently examined by a pathologist for the presence of inflammation and injury.

Determination of luminal PGE2, LTB4, and TNF-α.

Luminal fluid from CT-challenged and control mice was immediately collected and stored at −20°C. PGE2 was determined with a monoclonal enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) commercially available from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, Mich.). Luminal LTB4 was measured by ELISA (Biotrak, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). TNF-α production in the luminal fluid was determined with a matched antibody pair specific for murine TNF-α in an ELISA available from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.).

Measurements for oxidative stress.

Tissue levels of oxidized glutathione and the lipid peroxidation metabolites malonaldehyde and 4-hydroxyalkenal (4HNE) were determined as indicators of oxidative stress. Intestinal tissue segments (1 cm) from CT-challenged cox-1−/−, cox-2−/−, and wild-type control mice were stored at −70°C until assay. Oxidized glutathione tissue levels were determined with the Bioxytech GSH/GSSG-412 colorimetric assay for oxidized glutathione as described by the manufacturer (Oxis International, Inc., Portland, Oreg.). Briefly, intestinal segments from control and CT-challenged cox-1−/−, cox-2−/−, and wild-type mice were homogenized in assay buffer (100 mM NaPO4, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.5), and the protein concentration was determined. Then 100 μl of sample was mixed with 10 μl of the reduced glutathione scavenger 1-methyl-2-vinylpyridinium trifluoromethanesulfonate. Cold (4°C) 5% metaphosphoric acid (290 μl) was added to the sample, vortexed, and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min. Equal volumes (100 μl) of sample mixture, 1.262 mM 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), and 15 U of glutathione reductase per ml were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Then 100 μl of NADPH was added to the reaction mixture, and absorbance was read at 412 nm for 6 min as a measure of tissue Oxidized glutathione levels.

Tissue levels of lipid peroxidation metabolites malonaldehyde and 4HNE were measured with the Bioxytech LPO-586 colorimetric assay purchased from Oxis International, Inc. (Portland, Oreg.). Briefly, tissue homogenates were prepared as described by the manufacturer. Aliquots (200 μl) of standards and sample were vortexed with 650 μl of diluted N-methyl-2-phenylindole (chromogenic reagent), and 150 μl of 15.4 M methanesulfonic acid was added. The mixture was incubated at 45°C for 45 min and centrifuged to obtain a clear solution. The supernatant was transferred to a cuvette, and absorbance was read at 586 nm on a spectrophotometer.

For immunohistochemical staining, sections of adjacent, nonchallenged and CT-challenged small intestine from wild-type, cox-1−/−, and cox-2−/− mice were dried and fixed in acetone-methanol (1:1, vol/vol). After exposure to a heterologous preimmune serum (0.1 μg in PBS-T [PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20]) for 30 min, tissue sections were incubated for 60 min at 37°C with a primary antibody specific for 4HNE-protein adducts (Alpha Diagnostic International, Inc., San Antonio, Tex.). After being washed three times for 10 min at room temperature, a fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, Calif.) was then applied to the sections for 60 min at 37°C in order to visualize primary antibody binding. After being washed three times for 10 min in PBS-T at room temperature, the sections were mounted in antifade medium (Dako Inc., Carpinteria, Calif.). Images of cellular fluorescence were acquired with a Nikon Eclips TE300 UV photomicroscope.

RESULTS

CT-induced fluid accumulation is decreased by the COX-2 inhibitors celecoxib and rofecoxib.

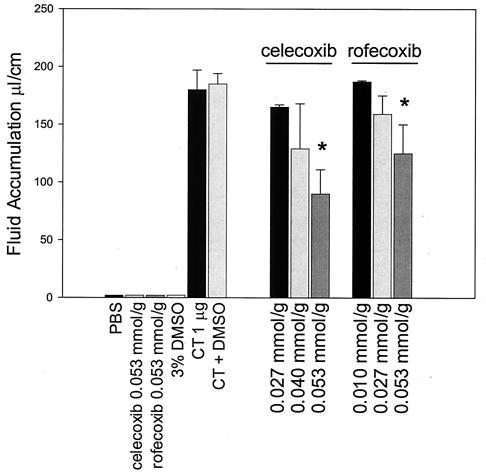

We tested the effect of specific COX-2 inhibitors on CT-induced fluid accumulation in a murine model of experimental cholera. Swiss-Webster mice underwent intestinal ligation, and CT (1 μg/loop) was instilled into the lumen of each 6- to 9-cm ligated small intestinal loop. Animals were treated with the COX-2-specific inhibitors celecoxib and rofecoxib at the time of CT challenge either by instillation into the lumen of the intestine or by intraperitoneal injection. After 6 h, intestinal loop fluid volume was measured. As shown in Fig. 1, CT induced an average of 180 ± 17 μl of fluid per cm of intestinal segment. A 0.053-mmol/g dose of celecoxib significantly reduced the CT-induced ratio of fluid to intestinal length down to 90 ± 21 μl/cm (P < 0.05, Dunnett's test), an approximately 48% reduction compared to CT challenge alone. In additional experiments, the effect of another specific COX-2 inhibitor, rofecoxib, on CT-induced fluid accumulation was determined. A single 0.053-mmol/g intraperitoneal dose of rofecoxib resulted in a 31% decrease in CT-induced fluid accumulation (Fig. 1). The dimethyl sulfoxide control (3% final concentration) showed that the concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide used to solubilize the celecoxib and rofecoxib did not significantly (P > 0.05) reduce CT-induced fluid accumulation.

FIG. 1.

Celecoxib and rofecoxib, selective inhibitors of COX-2, reduced fluid accumulation in CT-stimulated murine ligated intestinal loops. Groups (n = 6) of 6- to 8-week-old female Swiss-Webster mice underwent intestinal loop ligation. Loops were stimulated with CT (1 μg/loop). Celecoxib or rofecoxib was injected intraperitoneally at the time of challenge at the indicated doses. After a standard 6-h incubation period, mice were necropsied and fluid volume was determined. The vertical bars indicate one standard error above and below the arithmetic mean. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (P < 0.05) as determined by Dunnett's multiple-group comparison test.

To establish an optimal route of drug administration, animals were challenged with CT and dosed with an initial 0.027-mmol/g dose of celecoxib by either the luminal or the intraperitoneal route. In these experiments, all treated mice were given a subsequent 0.027-mmol/g dose of celecoxib by the intraperitoneal route after 2 h. The data showed that celecoxib reduced CT-induced fluid accumulation from the control response (125 ± 12 μl/cm) to 55 ± 13 μl/cm (56% reduction) and 40 ± 10 μl/cm (68% reduction) when the drug was given initially in the lumen and intraperitoneally, respectively.

CT equally induces fluid accumulation in cyclooxygenase gene-deficient mice.

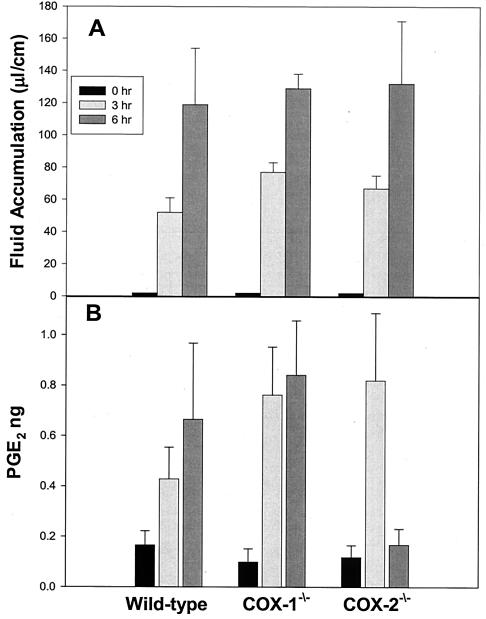

Groups of 10 cox-1−/− and 10 cox-2−/− and the 10 wild-type control cox+/+ mice [C57BL/6; 129P2(Ola)] underwent intestinal loop ligation. Challenge of all mice with CT resulted in a time-dependent increase in fluid accumulation (Fig. 2A). At 3 h, fluid levels in the ligated intestinal loops of wild-type, cox-1−/−, and cox-2−/− mice (n = 5) were 52 ± 9 μl/cm, 77 ± 6 μl/cm, and 67 ± 8 μl/cm, respectively. Fluid output in the intestinal loops of wild-type, cox-1−/−, and cox-2−/− mice (n = 5) increased to 119 ± 35 μl/cm, 129 ± 9 μl/cm, and 132 ± 39 μl/cm, respectively, after a 6-h incubation period. The values represent the average for five animals per group plus or minus one standard error. The difference between the groups was not significant (P > 0.05) at either the 3-h or the 6-h time point.

FIG. 2.

CT challenge of cox-1 and cox-2 gene-deficient mice. Groups of five 6- to 8-week-old cox-1−/−, cox-2−/−, and wild-type 129Ola/C57BL6 female mice underwent intestinal loop ligation. Loops were stimulated with cholera toxin (1 μg/loop) and returned to the peritoneal cavity. Fluid volume (A) and luminal PGE2 content (B) were determined upon necropsy after a 3- or 6-h incubation period. PGE2 content was determined by ELISA on clarified fluids. The vertical bars indicate one standard error above and below the arithmetic mean.

PGE2 levels were measured in unstimulated and CT-challenged intestinal tissue fluids from wild-type, cox-1−/−, and cox-2−/− mice (n = 5) at 3 and 6 h postchallenge. As shown in Fig. 2B, injection of CT into the ligated intestinal segments markedly increased PGE2 levels in the intestinal fluids of wild-type mice from 0.17 ± 0.06 pg to 0.43 ± 0.13 pg at 3 h and 0.67 ± 0.31 pg at 6 h. In cox-1−/− mice, CT increased PGE2 levels from 0.10 ± 0.05 pg to 0.76 ± 0.19 pg and 0.84 ± 0.22 pg at 3 and 6 h postchallenge, respectively. PGE2 levels measured in the intestinal fluids of cox-2−/− mice increased from 0.12 ± 0.05 pg to 0.82 ± 0.27 pg at 3 h but were only slightly elevated to 0.17 ± 0.06 pg at 6 h.

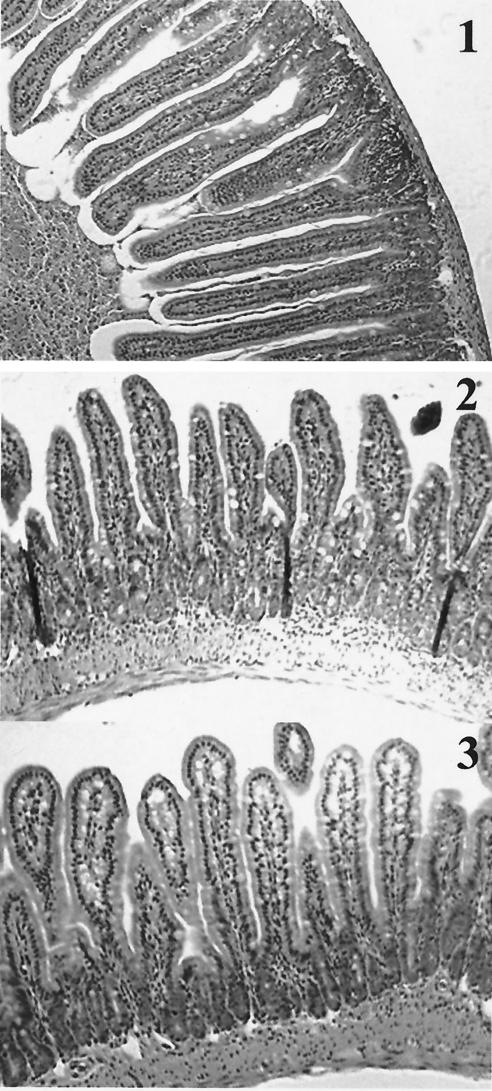

CT challenge results in small intestinal-tissue injury in ligated intestinal segments from cox-2−/− mice.

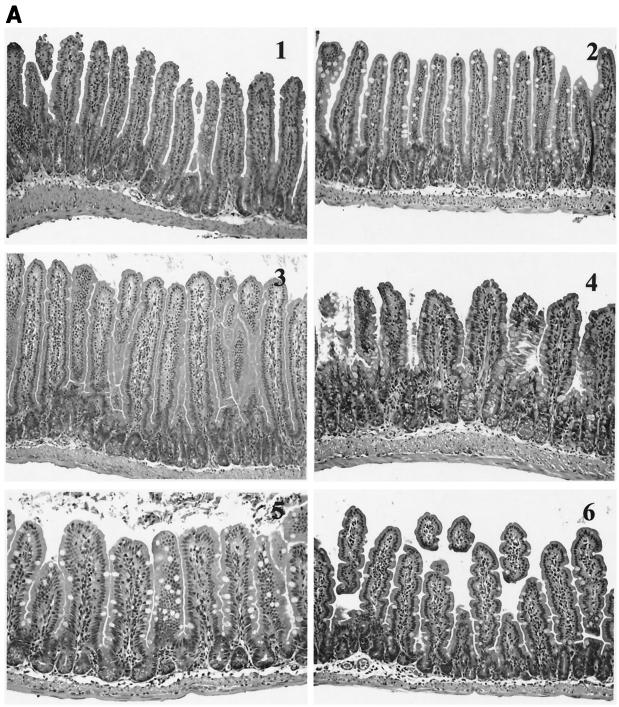

Intestinal tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin from wild-type, cox-1−/−, and cox-2−/− mice from both the 3-h and 6-h challenge experiments were examined for injury by light microscopy. In addition, sections were randomized and blindly evaluated by an independent pathologist. The evaluation of the tissue sections was based on the presence of villous edema, presence of inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, broadening of villi, and necrosis. Severe edema, inflammation, and necrosis were observed in cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− animals challenged with CT for 6 h compared to wild-type animals and animals challenged with PBS.

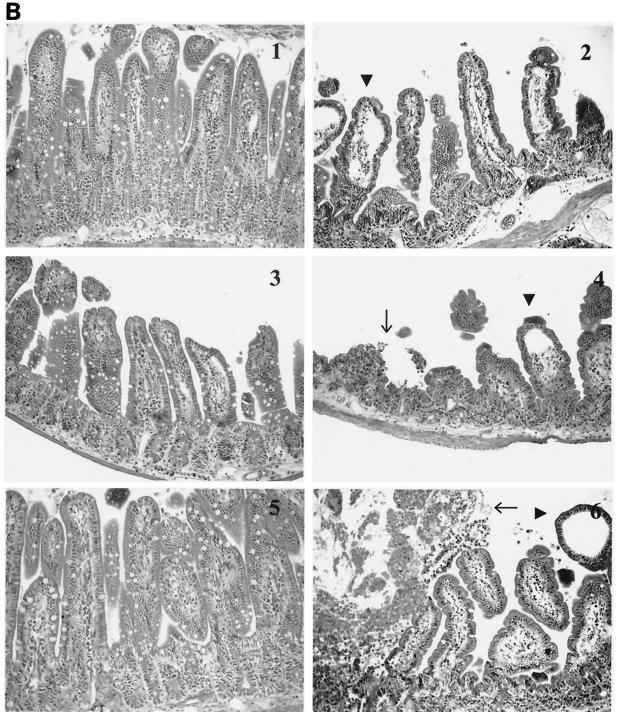

cox-2−/− mice revealed the presence of necrosis more frequently (four of five) than cox-1−/− animals (two of five) (Fig. 3A and B). At 3 h (Fig. 3A), the differences between the groups were minimal. Some of the histologic changes at 6 h (Fig. 3B) may have been due to the ligation procedure, as evidenced by the presence of mild to moderate villous edema and inflammation in tissue sections obtained from animals challenged with PBS. However, the histologic parameters were more severe in animals challenged with CT, and necrosis was only present in cox gene-deficient animals. To determine if the tissue injury observed in the cox-2−/− animals was due to CT's enzymatic activity, intestinal segments were challenged with heat-inactivated CT, the purified B subunit of CT, and lipopolysaccharide. As demonstrated in Fig. 4, the small intestinal sections did not exhibit tissue injury after challenge with heat-inactivated CT, the purified B subunit of CT, or lipopolysaccharide.

FIG. 3.

Intestinal architecture after a 3-h (A) and 6-h (B) CT challenge of wild-type, cox-1−/−, and cox-2−/− mice. Groups (n = 5) of 6- to 8-week-old cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− mice and wild-type 129Ola/C57BL6 female mice underwent intestinal loop ligation. Loops were then injected with CT (1 μg/loop) or PBS and returned to the peritoneal cavity. After 3 h (A) or 6 h (B), the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and intestinal loops were dissected and submitted for histochemistry (hematoxylin-eosin stains). (A) Wild-type mice after PBS (panel 1) and CT (panel 2) challenges. There is no alteration of the villous architecture or the intestinal wall. cox-1−/− mice after PBS (panel 3) and CT (panel 4) challenges. After CT challenge, there is mild broadening of intestinal villi. Inflammatory cells are slightly increased in both sections. No evidence of necrosis or edema is present. The same changes are also present in cox-2−/− mice after PBS (panel 5) and CT (panel 6) challenges. (B) Wild-type mice after PBS (panel 1) and CT (panel 2) challenges. The villi reveal mild to moderate edema and moderate inflammation of the lamina propria with villous broadening in animals challenged with PBS. These changes are most likely due to the ligation procedure. In animals challenged with CT, there is evidence of marked villous edema, inflammation, and broadening (arrowheads). No evidence of mucosal necrosis is present. In cox-1−/− mice after PBS (panel 3) and CT (panel 4) challenges and cox-2−/− mice after PBS (panel 5) and CT (panel 6) challenges, the intestinal mucosa revealed marked edema of villi with inflammation and focal villous necrosis (arrows) in animals challenged with CT. Animals challenged with PBS showed the same changes as described for wild-type animals challenged with PBS. Magnification, ×200.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of CT, inactive CT, CTB, and lipopolysaccharide challenges of cox-2−/− mice intestinal segments. Mice deficient in the cox-2 gene (n = 2) were challenged with 1 μg of heat-inactivated CT (panel 1), CT B subunit (panel 2), or lipopolysaccharide (panel 3). After a standard 6-h incubation, mice were sacrificed, and 1-cm small intestine sections were fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Intestinal sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined for tissue injury.

CT-induced small intestinal damage does not result from the production of the inflammatory mediators LTB4 and TNF-α.

Intestinal loop fluids were collected from the cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− mice after intestinal loop challenge with CT to determine whether the proinflammatory mediators LTB4 and TNF-α contributed to the tissue injury observed. Intestinal fluid was clarified by centrifugation for determination of LTB4 and TNF-α levels by ELISA. The levels of LTB4, an inflammatory mediator generated through arachidonic acid metabolism via lipooxygenase enzymes, were similar in all three groups. Wild-type levels were 41 ± 13.4 pg, compared to 14.9 ± 9.5 pg and 28 ± 20 pg in the cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− mice, respectively (P > 0.1). Likewise, the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α was not elevated in any of the groups (wild type, 3.95 ± 1.5 pg; cox-1−/−, 3.15 ± 1.8 pg; cox-2−/−, 3.3 ± 1.0 pg) (P > 0.1).

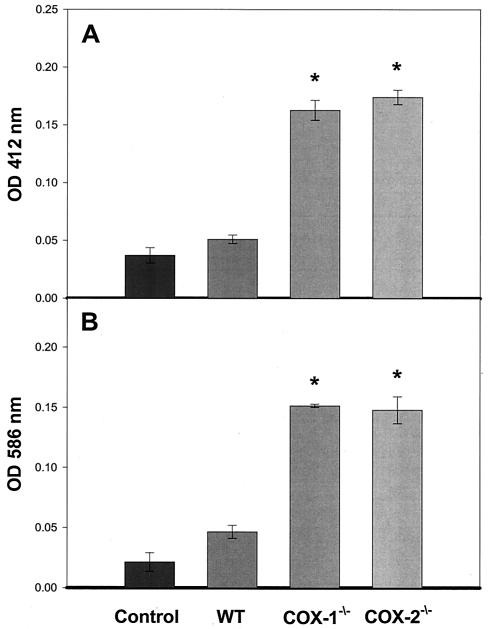

CT induced oxidized glutathione, malonaldehyde, and 4HNE, markers of oxidative stress, in cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− intestinal loop segments.

To determine if the tissue injury that we observed in the cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− mice was due to CT-induced oxidative stress, we determined the levels of oxidized glutathione and the lipid peroxidation markers malonaldehyde and 4HNE in the control and CT-challenged wild-type, cox-1−/−, and cox-2−/− intestinal segments. As shown in Fig. 5A, CT slightly increased the basal level of oxidized glutathione from 0.0371 ± 0.006 optical density unit in unstimulated control tissue to 0.0510 ± 0.003 optical density unit. Oxidized glutathione levels in CT-stimulated cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− tissue increased significantly to 0.1627 ± 0.008 optical density unit and 0.1740 ± 0.006 optical density unit, respectively. The lipid peroxidation markers (Fig. 5B) malonaldehyde and 4HNE increased significantly to 0.1514 ± 0.003 optical density unit in cox-1−/− mice and to 0.1478 ± 0.0112 optical density unit in cox-2−/− mice. CT challenge did not significantly increase malonaldehyde and 4HNE in wild-type tissue (0.0465 ± 0.005 optical density unit) compared to unchallenged control tissue (0.0214 ± 0.007 optical density unit). Significance was determined with the Tukey test for all pairwise multiple-group comparisons. To support the biochemical data, elevated levels of 4HNE-protein adducts in the tissue segments from CT-challenged and unchallenged wild-type, cox-1−/−, and cox-2−/− mice were observed by immunohistochemistry with an antibody specific for 4HNE-protein adducts (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Levels of oxidized glutathione and lipid peroxide metabolites in CT-challenged intestinal segments from cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− mice. Groups (n = 5) of 6- to 8-week-old cox-1−/−, cox-2−/−, and wild-type 129Ola/C57BL6 female mice underwent intestinal loop ligation. Loops were stimulated with cholera toxin (1 μg/loop) and returned to the peritoneal cavity. After a 6-h incubation period, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and 1-cm intestinal sections were removed from the peritoneal cavity and assayed for oxidized glutathione (A) and lipid peroxides (B). Error bars represent one standard error above the mean. Statistical significance was determined by the Tukey test.

DISCUSSION

It has long been known that inhibitors of the cyclooxygenase enzymes, such as indomethacin (9, 12, 13), are capable of inhibiting CT-induced fluid secretion responses. Due to the nonspecificity of these inhibitors, it was previously not possible to determine which of the COX enzymes, COX-1 or COX-2, played an important role in the fluid secretion response to CT. Here, we used a new class of reportedly specific COX-2 inhibitors (25, 29) that, when used at certain doses, do not inhibit the COX-1 enzyme. Furthermore, recent data indicate that celecoxib acts as a competitive inhibitor of adenylyl cyclase as well as COX-2 (43), which would indicate that the pharmacological inhibitors used in this study might also act as an inhibitor of CT's action on adenylyl cyclase.

In our study, celecoxib and rofecoxib were both shown to effectively inhibit CT-induced fluid accumulation in a murine model of experimental cholera. When comparing the inhibitory effectiveness of two COX-2 inhibitors on CT-induced fluid accumulation, we observed a greater inhibitory effect with celecoxib, which resulted in a 50% decrease, compared to the 31% decrease produced by rofecoxib. The dose used in these experiments was equivalent to the prescribed human dose of celecoxib (200 mg/75 kg twice daily) for rheumatoid arthritis. These results are quite interesting, because the prescribed effective dose of rofecoxib (25 mg/75 kg once daily) in the treatment of osteoarthritis is about one-fifth that of celecoxib. At this dose (25 mg/75 kg), rofecoxib was ineffective at reducing CT-induced fluid accumulation. It is possible that these results occurred due to structural differences in the drugs that allow different binding affinities to the active site of COX-2 or are due to different inhibitory capacities of each drug on cellular enzymes other than COX-2.

In light of recent data indicating an additional inhibitory action of selective COX-2 inhibitors on adenylyl cyclase activity (43), we used cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− and wild-type mice to further define the involvement of the COX isozymes and their subsequent product, PGE2, in the secretory response elicited by CT. The recent availability of mice lacking the COX-1 or COX-2 gene made it possible for us to independently evaluate the role of each isozyme in our experimental model. Interestingly, and in contrast to the selective inhibitor data, CT elicited a comparable volume of fluid accumulation in each line of the knockout mice compared to the wild-type animal controls. These data are consistent with the concept that the COX enzymes and PGE2 do not contribute to the sustained fluid secretion response elicited by CT and lend further support for CT's ability to cause fluid secretion through activation of adenylyl cyclase and stimulation of the enteric nervous system.

Alternatively, these data may suggest a possible mechanism by which either COX enzyme may function in a compensatory manner in the presence of available substrate (arachidonic acid) and the absence of the other enzyme. This conclusion is supported by measurements of similar PGE2 levels in CT-induced intestinal fluids of wild-type and cox-deficient mice (Fig. 2), with the exception of CT-challenged cox-2−/− mouse intestinal fluids from the 6-h challenge period, when a slight decrease in PGE2 content was observed. It is probable that the intestinal damage observed at 6 h led to the leakage of serum proteins into the intestinal lumen, which would bind PGE2 and prevent detection in our assay. These data were surprising because others have also shown that COX-2 is important in the fluid secretion response in a rat perfusion model with the reported specific COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 (3). The results may be the result of reciprocal compensation by either COX-1 or COX-2.

One interesting finding resulting from this study was the ability of CT to elicit mild small intestinal injury, evidenced by disrupted villar architecture and epithelial cell desquamation. Infections with V. cholerae and the subsequent production and action of CT in the small intestinal mucosa are known to cause secretory diarrhea without significant tissue injury, involvement of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α) (1), or neutrophil recruitment. In our 6-h challenge model, CT treatment caused significant destruction of the villar architecture in mice lacking the cox-2 gene and, to a lesser extent, in mice lacking the cox-1 gene. It is possible that the tissue injury occurring in these cox knockout mice resulted from ischemic necrosis and not as a direct result of CT's action on intestinal epithelial cells. In our 3-h challenge experiments of cox-2−/− mice with CT, intestinal loop distension was less than maximal. We observed that villar architecture was altered, with severe villar blunting and distortion. The effect observed was not attributed to endotoxin contamination of CT preparations or the B subunit of CT. This observation could suggest a direct effect of CT on the intestinal mucosa and a role for COX-2 and its metabolites in the protection and homeostatic maintenance of the intestinal mucosa.

It has been shown in another report that mice lacking either the cox-1 or cox-2 gene are more susceptible to colonic injury in a murine dextran sodium sulfate model of acute inflammation (25) and that both COX isozymes and their arachidonic acid metabolites are needed for mucosal protection. Newberry et al. (29) demonstrated the importance of functional COX-2 and its bioactive metabolites in the maintenance of normal intestinal mucosa and regulation of the intestinal mucosal immune response to dietary antigen. They used 3A9 transgenic mice lacking T-cell receptor alpha to examine the contribution of COX-2 metabolites in the absence of the cytokine milieu generated in mice possessing functional and specific αβ T-cell receptor-positive T helper lymphocytes, which are capable of responding to dietary antigens. In their model, animals dosed with NS-398 are susceptible to changes in intestinal architecture such as villar blunting and crypt expansion (29).

We were unable to implicate the proinflammatory mediators TNF-α and LTB4 as contributors to this tissue injury, which is consistent with unpublished findings in our laboratory and others regarding CT's inability to induce TNF-α in normal mice (1). In our model, the mediator of oxidative stress oxidized glutathione and the lipid peroxidation markers malonaldehyde and 4HNE were all increased after CT challenge of cox-1−/− and cox-2−/− intestinal loops. These data indicate that CT is capable of inducing oxidative stress without either the COX-1 or COX-2 enzyme. Further support of these data described by Pompeia et al. (38) indicates that arachidonic acid is a cytotoxic inducer of oxidative stress, as determined by measures of lipid peroxidation and glutathione/oxidized glutathione ratios, and that PGE2 was cytoprotective against arachidonic acid-induced oxidative stress.

The oxidative stress evoked by CT in the COX-2-deficient mice (and to a lesser extent in the COX-1-deficient mice) likely caused the injury to the intestinal tissue, as a result of CT's ability to release arachidonic acid (46). The oxidative metabolites (Fig. 5) could have originated from several resident intestinal cell types but were most probably released from polymorphonuclear leukocytes and mononuclear cells infiltrating the intestinal villi. Typically, CT does not evoke an inflammatory response; however, microscopic examination of hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections from the CT-challenged mouse intestinal loops showed increased inflammation in the COX-1- and COX-2-deficient mice. The infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and mononuclear cells was most notable in intestinal loops from the COX-2-deficient mice that had been challenged with CT, while tissue sections from loops obtained from unchallenged mice showed no signs of inflammation. Sections of intestinal loops from COX-2-deficient mice revealed that tissue injury correlated with cellular inflammation.

Taken together, these data and reports by others (38) reveal a protective role for arachidonic acid metabolites produced by the COX isozymes in the small intestinal mucosa and lend support for the hypothesis that eicosanoids (e.g., PGE2) act as anti-inflammatory mediators in the murine small intestine.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 1R01AI/DK50086 and by the James W. McLaughlin Fellowship Fund at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

Editor: A. D. O'Brien

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold, J. W., D. W. Niesel, C. R. Annable, C. B. Hess, M. Asuncion, Y. J. Cho, J. W. Peterson, and G. R. Klimpel. 1993. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates the early pathology in Salmonella infection of the gastrointestinal tract. Microb. Pathog. 14:217-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett, A. 1971. Cholera and prostaglandins. Nature 231:536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beubler, E., and G. Horina. 1990. 5-Hydroxytryptamine2 and 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor subtypes mediate cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion in the rat. Gastroenterology 99:83-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beubler, E., G. Kollar, A. Saria, K. Bukhave, and J. Rask-Madsen. 1989. Involvement of 5-hydroxytryptamine, prostaglandin E2, and cyclic adenosine monophosphate in cholera toxin-induced fluid secretion in the small intestine of the rat in vivo. Gastroenterology 96:368-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beubler, E., R. Schuligoi, A. K. Chopra, D. A. Ribardo, and B. A. Peskar. 2001. CT induces prostaglandin synthesis via post-transcriptional activation of cyclooxygenase-2 in the rat jejunum. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 297:940-945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassuto, J., M. Jodal, R. Tuttle, and O. Lundgren. 1982. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and cholera secretion. Physiological and pharmacological studies in cats and rats. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 17:695-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark, M. A., L. E. Ozgur, T. M. Conway, J. Dispoto, S. T. Crooke, and J. S. Bomalaski. 1991. Cloning of a phospholipase A2-activating protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5418-5422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crider, J. Y., B. W. Griffin, and N. A. Sharif. 1998. Prostaglandin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity via a pharmacologically defined EP2 receptor in human nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cells. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 14:293-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duebbert, I. E., and J. W. Peterson. 1985. Enterotoxin-induced fluid accumulation during experimental salmonellosis and cholera: involvement of prostaglandin synthesis by intestinal cells. Toxicon 23:157-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eklund, S., I. Brunsson, M. Jodal, and O. Lundgren. 1987. Changes in cyclic 3′5′-adenosine monophosphate tissue concentration and net fluid transport in the cat's small intestine elicited by cholera toxin, arachidonic acid, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and 5-hydroxytryptamine. Acta Physiol. Scand. 129:115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field, M., D. Fromm, Q. al-Awqati, and W. B. Greenough 3rd. 1972. Effect of cholera enterotoxin on ion transport across isolated ileal mucosa. J. Clin. Investig. 51:796-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Giannella, R. A., R. E. Gots, A. N. Charney, W. B. Greenough, 3rd, and S. B. Formal. 1975. Pathogenesis of Salmonella-mediated intestinal fluid secretion. Activation of adenylate cyclase and inhibition by indomethacin. Gastroenterology 69:1238-1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gots, R. E., S. B. Formal, and R. A. Giannella. 1974. Indomethacin inhibition of Salmonella typhimurium, Shigella flexneri, and cholera-mediated rabbit ileal secretion. J. Infect. Dis. 130:280-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris, R. C., J. A. McKanna, Y. Akai, H. R. Jacobson, R. N. Dubois, and M. D. Breyer. 1994. Cyclooxygenase-2 is associated with the macula densa of rat kidney and increases with salt restriction. J. Clin. Investig. 94:2504-2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinson, R. M., J. A. Williams, and E. Shacter. 1996. Elevated interleukin 6 is induced by prostaglandin E2 in a murine model of inflammation: possible role of cyclooxygenase-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:4885-4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hinz, B., K. Brune, and A. Pahl. 2000. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes is modulated by cyclic AMP, prostaglandin E(2), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 278:790-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinz, B., K. Brune, and A. Pahl. 2000. Prostaglandin E(2) upregulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 272:744-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacoby, H. I., and C. H. Marshall. 1972. Antagonism of cholera enterotoxin by anti-inflammatory agents in the rat. Nature 235:163-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jakobsson, P. J., S. Thoren, R. Morgenstern, and B. Samuelsson. 1999. Identification of human prostaglandin E synthase: a microsomal, glutathione-dependent, inducible enzyme, constituting a potential novel drug target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7220-7225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kujubu, D. A., B. S. Fletcher, B. C. Varnum, R. W. Lim, and H. R. Herschman. 1991. TIS10, a phorbol ester tumor promoter-inducible mRNA from Swiss 3T3 cells, encodes a novel prostaglandin synthase/cyclooxygenase homologue. J. Biol. Chem. 266:12866-12872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langenbach, R., S. G. Morham, H. F. Tiano, C. D. Loftin, B. I. Ghanayem, P. C. Chulada, J. F. Mahler, B. J. Davis, and C. A. Lee. 1997. Disruption of the mouse cyclooxygenase 1 gene. Characteristics of the mutant and areas of future study. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 407:87-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim, H., B. C. Paria, S. K. Das, J. E. Dinchuk, R. Langenbach, J. M. Trzaskos, and S. K. Dey. 1997. Multiple female reproductive failures in cyclooxygenase 2-deficient mice. Cell 91:197-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maldve, R. E., Y. Kim, S. J. Muga, and S. M. Fischer. 2000. Prostaglandin E(2) regulation of cyclooxygenase expression in keratinocytes is mediated via cyclic nucleotide-linked prostaglandin receptors. J. Lipid Res. 41:873-881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morham, S. G., R. Langenbach, J. Mahler, and O. Smithies. 1997. Characterization of prostaglandin H synthase 2 deficient mice and implications for mechanisms of NSAID action. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 407:131-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morteau, O., S. G. Morham, R. Sellon, L. A. Dieleman, R. Langenbach, O. Smithies, and R. B. Sartor. 2000. Impaired mucosal defense to acute colonic injury in mice lacking cyclooxygenase-1 or cyclooxygenase-2. J. Clin. Investig. 105:469-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moss, J., and M. Vaughn. 1988. CT and E. coli enterotoxins and their mechanisms of action, p. 39-87. In M. C. Hardegree and A. T. Tu (ed.), Handbook of natural toxins, vol. 4. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 27.Muller-Decker, K., C. Albert, T. Lukanov, G. Winde, F. Marks, and G. Furstenberger. 1999. Cellular localization of cyclo-oxygenase isozymes in Crohn's disease and colorectal cancer. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 14:212-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murakami, M., H. Naraba, T. Tanioka, N. Semmyo, Y. Nakatani, F. Kojima, T. Ikeda, M. Fueki, A. Ueno, S. Oh, and I. Kudo. 2000. Regulation of prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis by inducible membrane-associated prostaglandin E2 synthase that acts in concert with cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 275:32783-32792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newberry, R. D., W. F. Stenson, and R. G. Lorenz. 1999. Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent arachidonic acid metabolites are essential modulators of the intestinal immune response to dietary antigen. Nat. Med. 5:900-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilsson, O., J. Cassuto, P. A. Larsson, M. Jodal, P. Lidberg, H. Ahlman, A. Dahlstrom, and O. Lundgren. 1983. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and cholera secretion: a histochemical and physiological study in cats. Gut 24:542-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patrizio, M., M. Colucci, and G. Levi. 2000. Protein kinase C activation reduces microglial cyclic AMP response to prostaglandin E2 by interfering with EP2 receptors. J. Neurochem. 74:400-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penning, T. D., J. J. Talley, S. R. Bertenshaw, J. S. Carter, P. W. Collins, S. Docter, M. J. Graneto, L. F. Lee, J. W. Malecha, J. M. Miyashiro, R. S. Rogers, D. J. Rogier, S. S. Yu, AndersonGd, E. G. Burton, J. N. Cogburn, S. A. Gregory, C. M. Koboldt, W. E. Perkins, K. Seibert, A. W. Veenhuizen, Y. Y. Zhang, and P. C. Isakson. 1997. Synthesis and biological evaluation of the 1,5-diarylpyrazole class of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: identification of 4-[5-(4-methylphenyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazol-1-yl]benzenesulfonamide (SC-58635, celecoxib). J. Med. Chem. 40:1347-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson, J. W., J. Cantu, S. Duncan, and A. K. Chopra. 1993. Molecular mediators formed in the small intestine in response to cholera toxin. J. Diarrhoeal Dis. Res. 11:227-234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson, J. W., C. A. Jackson, and J. C. Reitmeyer. 1990. Synthesis of prostaglandins in cholera toxin-treated Chinese hamster ovary cells. Microb. Pathog. 9:345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson, J. W., and L. G. Ochoa. 1989. Role of prostaglandins and cyclic AMP in the secretory effects of cholera toxin. Science 245:857-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson, J. W., S. S. Saini, W. D. Dickey, G. R. Klimpel, J. S. Bomalaski, M. A. Clark, X. J. Xu, and A. K. Chopra. 1996. CT induces synthesis of phospholipase A2-activating protein. Infect. Immun. 64:2137-2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pierce, N. F., C. C. Carpenter, Jr., H. L. Elliott, and W. B. Greenough 3rd. 1971. Effects of prostaglandins, theophylline, and cholera exotoxin upon transmucosa water and electrolyte ovement in the canine jejunum. Gastroenterology 60:22-32. [PubMed]

- 38.Pompeia, C., J. J. S. Freitas, J. S. Kim, S. B. Zyngier, and R. Curi. 2002. Arachidonic acid cytotoxicity in leukocytes: implications of oxidative stress and eicosanoid synthesis. Biol. Cell 94:251-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Portanova, J. P., Y. Zhang, G. D. Anderson, S. D. Hauser, J. L. Masferrer, K. Seibert, S. A. Gregory, and P. C. Isakson. 1996. Selective neutralization of prostaglandin E2 blocks inflammation, hyperalgesia, and interleukin 6 production in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 184:883-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prasit, P., Z. Wang, C. Brideau, C. C. Chan, S. Charleson, W. Cromlish, D. Ethier, J. F. Evans, A. W. Ford-Hutchinson, J. Y. Gauthier, R. Gordon, J. Guay, M. Gresser, S. Kargman, B. Kennedy, Y. Leblanc, S. Leger, J. Mancini, G. P. O'Neill, M. Ouellet, M. D. Percival, H. Perrier, D. Riendeau, I. Rodger, R. Zamboni, et al. 1999. The discovery of rofecoxib, [MK 966, Vioxx, 4-(4′-methylsulfonylphenyl)-3-phenyl-2(5H)-furanone], an orally active cyclooxygenase-2-inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 9:1773-1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reimer, R., H. K. Heim, R. Muallem, H. S. Odes, and K. F. Sewing. 1992. Effects of EP-receptor subtype specific agonists and other prostanoids on adenylate cyclase activity of duodenal epithelial cells. Prostaglandins 44:485-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ristimaki, A., S. Garfinkel, J. Wessendorf, T. Maciag, and T. Hla. 1994. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 by interleukin-1 alpha. Evidence for post-transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 269:11769-11775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saini, S. S., D. L. Gessell-Lee, and J. W. Peterson. 2003. The COX-2 specific inhibitor celecoxib inhibits adenylyl cyclase. Inflammation 27:79-88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Serebro, H. A., F. L. Iber, J. H. Yardley, and T. R. Hendrix. 1969. Inhibition of cholera toxin action in the rabbit by cycloheximide. Gastroenterology 56:506-511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith, P. R., D. J. Dawson, and C. H. Swan. 1979. Prostaglandin synthetase activity in acute ulcerative colitis: effects of treatment with sulphasalazine, codeine phosphate and prednisolone. Gut 20:802-805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith, W. L., and D. L. Dewitt. 1996. Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases-1 and -2. Adv. Immunol. 62:167-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spangler, R. S. 1996. Cyclooxygenase 1 and 2 in rheumatic disease: implications for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 26:435-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strassmann, G., V. Patil-Koota, F. Finkelman, M. Fong, and T. Kambayashi. 1994. Evidence for the involvement of interleukin 10 in the differential deactivation of murine peritoneal macrophages by prostaglandin E2. J. Exp. Med. 180:2365-2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanioka, T., Y. Nakatani, N. Semmyo, M. Murakami, and I. Kudo. 2000. Molecular identification of cytosolic prostaglandin E2 synthase that is functionally coupled with cyclooxygenase-1 in immediate prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:32775-32782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tothill, A. 1976. Prostaglandin E2: a factor in the pathogenesis of cholera. Prostaglandins 11:925-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaisrub, S. 1972. Cholera, prostaglandins, and cyclic AMP. JAMA 219:213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Loon, F. P., G. H. Rabbani, K. Bukhave, and J. Rask-Madsen. 1992. Indomethacin decreases jejunal fluid secretion in addition to luminal release of prostaglandin E2 in patients with acute cholera. Gut 33:643-645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walenga, R. W., M. Kester, E. Coroneos, S. Butcher, R. Dwivedi, and C. Statt. 1996. Constitutive expression of prostaglandin endoperoxide G/H synthetase (PGHS)-2 but not PGHS-1 in human tracheal epithelial cells in vitro. Prostaglandins 52:341-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams, J. A., and E. Shacter. 1997. Regulation of macrophage cytokine production by prostaglandin E2. Distinct roles of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2. J. Biol. Chem. 272:25693-25699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie, W. L., J. G. Chipman, D. L. Robertson, R. L. Erikson, and D. L. Simmons. 1991. Expression of a mitogen-responsive gene encoding prostaglandin synthase is regulated by mRNA splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:2692-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamagata, K., K. I. Andreasson, W. E. Kaufmann, C. A. Barnes, and P. F. Worley. 1993. Expression of a mitogen-inducible cyclooxygenase in brain neurons: regulation by synaptic activity and glucocorticoids. Neuron 11:371-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu, Y., and K. Chadee. 1998. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates IL-8 gene expression in human colonic epithelial cells by a posttranscriptional mechanism. J. Immunol. 161:3746-3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]