Abstract

We have identified platelet glycoprotein (GP) Ibα as a counterreceptor for P-selectin. GP Ibα is a component of the GP Ib-IX-V complex, which mediates platelet adhesion to subendothelium at sites of injury. Cells expressing P-selectin adhered to immobilized GP Ibα, and GP Ibα–expressing cells adhered to and rolled on P-selectin and on histamine-stimulated endothelium in a P-selectin–dependent manner. In like manner, platelets rolled on activated endothelium, a phenomenon inhibited by antibodies to both P-selectin and GP Ibα. Unlike the P-selectin interaction with its leukocyte ligand, PSGL-1 (P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1), the interaction with GP Ibα required neither calcium nor carbohydrate core-2 branching or α(1,3)-fucosylation. The interaction was inhibited by sulfated proteoglycans and by antibodies against GP Ibα, including one directed at a tyrosine-sulfated region of the polypeptide. Thus, the GP Ib-IX-V complex mediates platelet attachment to both subendothelium and activated endothelium.

Keywords: platelet adhesion, endothelium, platelet glycoproteins, selectins, PSGL-1

During inflammatory processes, endothelial selectins mediate the initial interaction of leukocytes with endothelium as the leukocytes make their way from the bloodstream into the tissues. The interaction of the selectins with leukocyte mucins, in particular a protein called P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1),1 is characterized by having rapid on and off rates, allowing the leukocytes in the flowing blood to roll along the endothelium. These leukocytes then undergo a tighter interaction with the vessel wall mediated by β2 integrins on the leukocytes and receptors of the Ig superfamily on the endothelial cells 1. P-selectin is the first selectin to be expressed on the endothelial surface in response to inflammatory stimuli such as thrombin and histamine, translocating from the membranes of storage granules (the Weibel-Palade bodies) to the plasma membrane within seconds. P-selectin and the other selectins, E- and L-selectin, are type I transmembrane proteins, each having an NH2-terminal C-type lectin domain followed by an epidermal growth factor domain and a series of short complement repeats that separate the lectin domain from the plasma membrane 2. The P-selectin interaction with PSGL-1 requires a number of posttranslational modifications in the latter molecule, including a branched, fucosylated structure on its O-linked carbohydrate side chains 3 and sulfated tyrosine residues within a cluster of acidic residues at its NH2 terminus 4 5 6 7.

Like leukocytes, unactivated platelets can roll on the surface of inflamed endothelium, in a process dependent on endothelial selectins 8. The process is independent of platelet selectins, as platelets from mice lacking P- and E-selectin roll as efficiently as platelets from normal mice 9. Unlike the interaction of the selectins with leukocytes, their interaction with platelets does not require fucosylation of the ligand, as no difference was observed between platelets from mice lacking both α(1,3)-fucosyl transferases (FucTs), FucT IV and FucT VII, and those of normal mice. These studies were the first to demonstrate that unactivated platelets interact with endothelial cells, which are generally considered nonthrombogenic. In marked contrast, it is well known that when the endothelium is removed, platelets interact rapidly with the exposed matrix, initially through the platelet glycoprotein (GP) Ib-IX-V complex and subendothelial von Willebrand factor 10. The GP Ib-IX-V complex comprises four polypeptides, GP Ibα, GP Ibβ, GP IX, and GP V, and can support the rolling of platelets 11 and transfected cells 12 13 on immobilized von Willebrand factor under flow, a process similar to the rolling interaction of platelets on inflamed endothelium, albeit at much higher shear rates. GP Ibα contains the von Willebrand factor–binding site and, like PSGL-1, it is a sialomucin with a cluster of O-linked carbohydrates separating the NH2-terminal ligand-binding region from the plasma membrane. In addition, it contains a region rich in anionic amino acids with sulfated tyrosines necessary for optimal ligand binding 14 15 16. A further parallel between GP Ibα and PSGL-1 is the site of synthesis of their ligands: von Willebrand factor and P-selectin are synthesized and stored only in the Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells and the α-granules of megakaryocytes and platelets. Given these similarities between the two molecules and the high surface density of GP Ibα on the platelet surface (25,000–50,000 copies per platelet), we sought to determine if the GP Ib-IX-V complex might constitute a P-selectin counterreceptor.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies.

Antibodies against P-selectin included affinity-purified polyclonal antiserum produced in rabbits immunized with P-selectin purified from platelet lysates 17 and the mAb WAPS 12.2 (Zymed Labs., Inc.). Anti-GP Ibα mAbs used were: WM23 and AK3, both of which bind within the mucin-like macroglycopeptide 18; SZ2, which recognizes an epitope within the anionic/sulfated tyrosine region of GP Ibα bounded by residues Tyr276 and Glu282 16; and AK2 (RDI Research Diagnostics), which binds within the GP Ibα NH2 terminus and inhibits ristocetin- and botrocetin-induced von Willebrand factor binding 16. Two von Willebrand factor mAbs were used in these studies: 6G1, which inhibits the von Willebrand factor–GP Ibα interaction (our unpublished data), and 2C9, which does not inhibit the binding of von Willebrand factor to GP Ibα and was used as a control mAb 18. HECA-452 is a rat mAb (IgM) that recognizes a FucT VII–dependent carbohydrate 19 20.

Glycocalicin Purification.

Glycocalicin was isolated from outdated human platelets by a method modified from that of Hess et al. 21. Erythrocyte-free platelets were isolated from 10 liters of outdated platelet-rich plasma (obtained from the Blood Transfusion Centre, Cambridge, England) by centrifugation and washed with buffer A (13 mM Na3 citrate, 120 mM NaCl, and 30 mM glucose, pH 7.0). After another centrifugation, the platelet pellet was suspended in 500 ml of buffer B (10 mM Tris/HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) and sonicated. The resultant suspension was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min to allow the calpain released from the platelets during sonication to cleave membrane-bound GP Ibα, releasing glycocalicin. After ultracentrifugation to remove cell components, the glycocalicin-containing supernatant was applied to a wheat germ Sepharose 4B column. Bound crude glycocalicin was eluted with 2.5% N-acetyl-d-glucosamine and 20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4. Further purification by ion exchange chromatography (on Q-Sepharose Fast-flow column; Pharmacia) was needed to remove residual contaminants. Glycocalicin was eluted with a linear salt gradient of 0–0.7 M NaCl in 20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4.

Cell Lines.

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing a phosphatidylinositol glycan–linked form of P-selectin were a gift from Dr. C. Wayne Smith (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) 22. These cells were grown in medium comprising equal parts DMEM and F12 medium (GIBCO BRL) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 U/ml streptomycin. CHO and L cells expressing the GP Ib-IX-V complex and its components have been described previously 23. In brief, CHO αβIX cells express GP Ibα, GP Ibβ, and GP IX, the three polypeptides that are minimally required for efficient cell surface expression of GP Ibα. L αβIXV cells additionally express GP V, and CHO and L βIX cells express GP Ibβ and GP IX but lack GP Ibα and GP V. The conditions for their growth have been described 23 24.

Flow Cytometry.

Before each experiment involving cells that express GP Ibα, the surface level of this polypeptide was first determined by flow cytometry using AK2 as previously described 25. In brief, cells grown in a monolayer were detached with 0.54 mM EDTA, washed with PBS, and resuspended in PBS containing 1% BSA. The cells were then incubated with AK2 (1 μg/ml) for 60 min at room temperature. After being washed to remove unbound antibody, the cells were incubated with an FITC-conjugated rabbit anti–mouse secondary antibody (Zymed Labs., Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were then analyzed on a FACScan™ flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) stimulating with laser light at 488 nm and collecting light emitted at >520 nm.

Transfections.

To induce core-2 branching and α(1,3)-fucosylation of the GP Ibα carbohydrates in CHO cells, the cells were cotransfected with plasmids containing cDNAs encoding C2GnT (core 2 β(1,6)-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase), (pCDNA1/C2GnT, a gift from Dr. Minoru Fukuda, La Jolla Cancer Research Foundation, La Jolla, CA) and FucT VII (provided for these studies by Dr. John Lowe, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) using a modified SRa vector containing a hygromycin resistance marker 19. Transfections were by liposome-mediated DNA delivery (LipofectAMINE; GIBCO BRL). A total of 1 μg of plasmid was used in each transfection, with the FucT VII plasmid transfected either alone or as an equal mixture with the plasmid containing the C2GnT cDNA. The cells were selected by growth in hygromycin-containing medium, for which a resistance marker is contained in the FucT VII plasmid. FucT VII expression was evaluated by flow cytometry with the antibody HECA-452, which recognizes a FucT VII–dependent epitope. Labeling and analysis were as described above for GP Ibα, except that an FITC-conjugated rabbit anti–rat antibody (Zymed Labs., Inc.) was used to label cell-bound HECA-452.

CHO-P Adhesion to Glycocalicin.

The wells of 96-well microtiter plates (Nunc Immulon, Inc.) were coated with 50 μl of purified glycocalicin (20 μg/ml in PBS, pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature. The wells were rinsed four times over 20 min with DMEM containing 1% BSA. CHO cells and CHO cells expressing P-selectin (CHO-P) were detached from culture dishes using 5 ml of 0.54 mM EDTA in PBS, washed once in PBS and once in DMEM, and then incubated at 37°C for 30 min in DMEM containing 0.5 mCi of 51Cr per 107 cells. Cells were then washed three times by centrifugation and resuspension and then resuspended to a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml in DMEM containing 1.0% BSA and preincubated at room temperature for 15 min with either 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, in 0.15 M NaCl (TS buffer) alone or with TS buffer containing appropriate amounts of sulfated glycans or other blocking reagents. Aliquots of 0.1 ml of the cell suspension were incubated at room temperature in four replicate microtiter wells for 15 min. The media and nonadherent cells were then removed, and the wells were rinsed three times with DMEM containing 1% BSA. 51Cr-labeled cells that remained adherent to the wells were lysed in a solution containing 1% Triton X-100, and their radioactivity was assayed in a gamma counter. For studies that included anti–GP Ibα blocking antibodies, the antibodies were incubated with the immobilized glycocalicin for 15 min at room temperature (each antibody at 40 μg/ml) before the addition of the radiolabeled cells. Each experiment was performed in triplicate; average counts from one representative experiment are reported.

Glycocalicin Inhibition of P-Selectin Antibody Binding to CHO-P.

CHO-P cells detached with EDTA were resuspended in α–minimal essential medium (α-MEM; GIBCO BRL) containing 1% BSA and aliquoted to a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml. Purified glycocalicin or soybean trypsin inhibitor were then added to the cell suspensions at various concentrations and shaken gently for 15 min. Polyclonal anti–P-selectin antibody was then added to each tube (final concentration, 2 μg/ml), and the cells were incubated for an additional 45 min. The cells were then washed twice in PBS, and FITC-conjugated goat anti–rabbit antibody was added to a concentration of 8 μg/ml and incubated for 45 min. Antibody binding was then assessed by flow cytometry.

CHO Cell Aggregation.

CHO cells were labeled with membrane dyes, CellTracker™ Orange (5-(and -6)-(((4 chloromethyl)benzoyl)amino)-tetramethylrhodamine) for CHO-P cells and CellTracker™ Green (5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate) for CHO αβIX and CHO βIX (both dyes from Molecular Probes, Inc.). For this, the cells were detached from the culture dishes with 0.54 mM EDTA, centrifuged, and resuspended in culture medium. The dyes were each added to the cell suspension at 12 μM and incubated at 25°C for 60 min in the dark, with gentle shaking. After labeling, the cells were washed twice in PBS and resuspended in α-MEM, 1% BSA to a concentration of 6 × 106 cells/ml. 500-μl aliquots of CHO-P cells were then mixed with equal volumes of the other cell lines, and the mixture was shaken on a table-top shaker at six cycles per second for 10 min. Heterotypic aggregates of green and orange cells were quantitated by fluorescence microscopy. These experiments were also done with CHO αβIX cells pretreated with mocarhagin, a metalloprotease from the venom of the South African spitting cobra, Naja mocambique mocambique. This protease selectively cleaves the GP Ibα NH2 terminus, including a region containing three sulfated tyrosine residues 16. Before the aggregation experiment, the CHO αβIX cells were incubated for 30 min with mocarhagin (20 μg/ml) and then washed twice with PBS.

Preparation of Purified P-Selectin and P-Selectin Matrix.

Human P-selectin was purified from outdated platelets as described previously 26. Detergent, Triton X-100, was removed from the P-selectin sample immediately before use by passage through an Extracti-Gel D column (Pierce Chemical Co.). To prepare the P-selectin matrix, glass coverslips (No. 1, 24 × 50 mm; Corning Glass Works) were coated with a solution containing 50 μg/ml P-selectin for 4 h at 37°C followed by an additional 1-h incubation with PBS containing 1% BSA to block nonspecific binding sites. The coated coverslips were then washed with 0.9% NaCl to remove unbound P-selectin.

Preparation of Primary Cultures of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells.

Human umbilical cords were collected and processed for primary endothelial cell culture as described previously 27. In brief, human umbilical cords were rinsed with PBS and then treated with collagenase type II (10 μg/50 ml PBS; Worthington Biochemical Corp.) for 40 min at room temperature. Enzymatically dissociated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were collected by centrifugation (10 min, 200 g) and then resuspended in M199 medium (GIBCO BRL) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% glutamine. The cells were then plated onto glass coverslips that had previously been coated with a 1% gelatin solution for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity and reached confluence in ∼4–5 d.

To induce surface expression of P-selectin, monolayers of confluent HUVECs were treated with 25 μM histamine (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 12 min at room temperature 27. Stimulated cells were used immediately.

Parallel Plate Flow Chamber.

The flow chamber system included a parallel plate flow chamber, an inverted stage phase-contrast microscope (DIAPHOT-TMD; Nikon Inc.), and an image recording system. The parallel plate flow chamber was composed of a polycarbonate slab, a silicon gasket, and a glass coverslip held together by vacuum in such a way that the coverslip forms the bottom of the chamber. The coverslips were first coated with either soluble P-selectin or a monolayer of HUVECs. The chamber was maintained at 37°C by an air curtain incubator attached to the microscope. The wall shear stress was created by drawing PBS through the chamber with a Harvard syringe pump and was proportional to the fluid viscosity and flow rate and inversely proportional to the width of the chamber and height of the gap created by the gasket 28.

In studies of GP Ib-IX-V–mediated cell rolling on P-selectin, 0.6 ml of a suspension of CHO αβIX, CHO βIX, L βIX, or L αβIXV cells (500,000 cells/ml) was injected into the chamber, and the cells were incubated for 1 min with immobilized P-selectin or 2 min with stimulated endothelial cells. At the end of the incubation, PBS was perfused through the chamber at a flow rate of 1.6 ml/min, generating a wall shear stress of 2 dynes/cm2 (shear rate ∼182/s). Cell rolling through a single view field was recorded in real time for 4–6 min on videotape. The video data were then analyzed off line using Inovision imaging software (IC-300, Modular Image Processing Workstation; Inovision Corp.) to quantify the number and velocities of the rolling cells 27 29. Cells considered to be rolling were those that translocated over the matrix or HUVECs while maintaining constant contact. The rolling velocity was defined as the distance a cell traveled during a defined period (μm/s).

To examine platelet rolling on activated HUVECs, platelets prepared as described below were resuspended to 2 × 108 cells/ml in PBS with 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 20% erythrocytes by volume. The HUVECs were stimulated as above, and the platelet suspension was allowed to incubate for 2 min at 37°C before perfusing the chamber with the platelet suspension at a flow rate of 1.6 ml/min, generating a wall shear stress of 2 dynes/cm2 (shear rate ∼120/s).

Platelet Preparation.

Blood was drawn from healthy human donors into 1/6 volume of acid citrate dextrose (85 mM Na3 citrate, 111 mM dextrose, and 71 mM citric acid). The blood was centrifuged at 170 g for 15 min at 25°C to separate platelet-rich plasma from erythrocytes and leukocytes. The platelets were then pelleted from platelet-rich plasma by centrifugation at 800 g for 10 min at 25°C. The platelets were then washed by suspension in CGS buffer (13 mM sodium citrate, 30 mM glucose, and 120 mM sodium chloride, pH 6.5), centrifuged again, and resuspended to 2 × 108 platelets/ml in PBS containing calcium and magnesium. All solutions except for the final resuspension buffer contained 1 μM prostaglandin E1 to prevent platelet activation.

Statistical Analysis.

The data were analyzed either by the unpaired Student's t test or by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), depending on the nature of the data.

Results

CHO Cells Expressing P-Selectin Adhere to Immobilized Soluble GP Ibα (Glycocalicin) in a Calcium-independent Manner.

As a first step in determining if the GP Ib-IX-V complex interacts with P-selectin, we examined the binding of CHO-P cells to the soluble extracellular portion of human GP Ibα (called glycocalicin) immobilized on plastic. Glycocalicin was purified from lysates of human platelets and therefore contained all of the posttranslational modifications potentially required to constitute a platelet P-selectin receptor. The binding of CHO-P cells to glycocalicin was approximately fivefold greater than the binding of untransfected cells (n = 4, P < 0.001, Student's t test), suggesting a specific interaction between P-selectin and GP Ibα (Fig. 1 A). We then tested the ability of different reagents to block this interaction. The P-selectin interaction with PSGL-1 is dependent on two structural modifications of PSGL-1: tyrosine sulfation within a negatively charged sequence at its mature NH2 terminus and fucosylation, sialylation, and core-2 branching of its O-linked carbohydrate. P-selectin interacts with the carbohydrate motif through its C-type lectin domain in a calcium-dependent fashion. We therefore tested whether EDTA would inhibit the interaction of P-selectin with GP Ibα. Surprisingly, and in contrast to the interaction with PSGL-1, it did not (n = 3, P = 0.20, Student's t test; Fig. 1 B). However, antibodies against both GP Ibα and P-selectin did inhibit the interaction. Of the GP Ibα antibodies, the greatest inhibition of binding was observed with SZ2 (∼55% inhibition; n = 3, P < 0.03, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's method). This antibody has been shown to recognize an epitope within the tyrosine-sulfated anionic region of GP Ibα 16, suggesting that this region plays an important role in the recognition of P-selectin. The other two GP Ibα mAbs, WM23 and AK3, directed against the GP Ibα mucin core 18, inhibited binding to a lesser extent. Binding was also almost completely inhibited by an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody against P-selectin (n = 3, P < 0.002, Student's t test).

Figure 1.

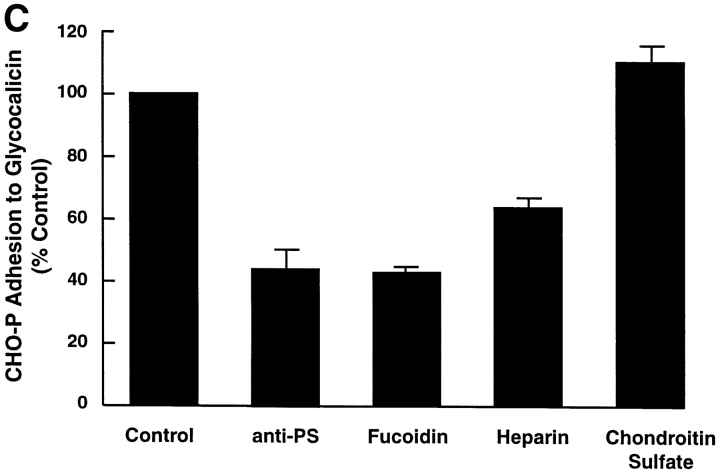

(A) Adhesion of CHO-P cells to glycocalicin. Glycocalicin, the soluble extracellular portion of GP Ibα, was immobilized on the wells of plastic microtiter plates. 51Cr-labeled CHO-P cells or untransfected CHO cells were then incubated in the wells under static conditions. After the wells were washed, the residual radioactivity was quantitated. (B) Inhibition of CHO-P adhesion to glycocalicin. The experiment was performed as in A, except that the relevant inhibitor or control was either preincubated with the bound glycocalicin (the anti-GP Ibα antibodies) or incubated with the cells during the adhesion assay. The adhesion is displayed as a percentage of the adhesion under control conditions after subtracting the background adhesion of untransfected CHO cells. Data are segregated into three sets. In the first set, the calcium dependence of the interaction was assessed by performing the assay either in the presence or absence of 5 mM EDTA; the second set depicts the effects of GP Ibα mAbs with an irrelevant antibody as a control; and the third set depicts the effect of an anti–P-selectin antibody, with nonimmune rabbit IgG serving as the control. The antibodies used are 2C9, an anti–von Willebrand factor antibody (control), and SZ2, WM23, and AK3, which are all directed against GP Ibα. SZ2 maps to the anionic sulfated region bounded by amino acid residues 276–282; WM23 and AK3 both bind within the mucin-like macroglycopeptide region that lies between the anionic sulfated region and the plasma membrane. The anti-PS antibody is an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody prepared against P-selectin purified from platelets. The experiment was performed three times in quadruplicate; data shown here are derived from one representative experiment and are presented as mean ± SE of the mean for that experiment. (C) Proteoglycan inhibition of CHO-P adhesion to glycocalicin. Different proteoglycans were tested for their ability to inhibit the adhesion of CHO-P to glycocalicin. The experimental conditions were as in A, except that the CHO-P cells were preincubated with the indicated proteoglycan at the following concentrations: 0.4 mg/ml fucoidin and chondroitin sulfate and 5 mg/ml heparin. As in B, the results are displayed as a percent of the adhesion of the control, untreated CHO-P cells, after subtracting the background adhesion of untransfected CHO cells. Experiments were performed twice in quadruplicate; the results of one representative experiment are shown.

P-Selectin's Interaction with GP Ibα Mimics Its Interaction with Heparin.

Two findings indicated a potential similarity between P-selectin's interaction with GP Ibα and its interaction with heparin: its calcium independence 17 30 and the involvement of the GP Ibα anionic/tyrosine sulfated region. This region of GP Ibα contains three sulfated tyrosine residues 14 16 and interacts with another of GP Ibα's ligands, thrombin, through thrombin's heparin-binding exosite 31 32. We therefore studied the effect of heparin and other proteoglycans on CHO-P adhesion to glycocalicin. Heparin and the related proteoglycan fucoidin both partially inhibited binding (n = 3, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test; Fig. 1 C). In contrast, chondroitin sulfate, a control proteoglycan that does not block the P-selectin–PSGL-1 interaction, similarly did not affect the P-selectin–GP Ibα interaction (P > 0.1).

Glycocalicin Blocks Antibody Binding to CHO-P Cells.

We next tested the ability of glycocalicin to interfere with the binding to CHO-P cells of a polyclonal antibody against human P-selectin. This antibody blocks the P-selectin–PSGL-1 interaction 17 and, as shown in Fig. 1 B, also blocks the adhesion of CHO-P to glycocalicin. Glycocalicin blocked antibody binding in a dose-dependent manner, with a 50% inhibiting concentration (IC50) of ∼25 μg/ml (n = 3, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test; Fig. 2). The results suggest that most of the binding determinants for the polyclonal antibody lie within a restricted region of P-selectin close to the GP Ibα binding site.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of antibody binding to P-selectin. CHO-P cells were incubated in increasing concentrations of glycocalicin or soybean trypsin inhibitor before the addition of anti–P-selectin polyclonal antibody. The binding of the antibody was evaluated by flow cytometry after incubation of the cells with an FITC-conjugated goat anti–rabbit secondary antibody. 100% binding is the binding in the absence of added protein. Glycocalicin inhibited antibody binding, with an IC50 of ∼25 μg/ml. Soybean trypsin inhibitor had no effect. Values reported are averaged from three experiments.

Posttranslational Core-2 Branching and α(1,3)-Fucosylation Are Not Required for GP Ibα Binding to P-Selectin.

CHO cells synthesize simple core-1 O-linked glycans 33 and are incapable of synthesizing PSGL-1 in a form competent to bind P-selectin unless the appropriate carbohydrate-modifying enzymes are also expressed 34. Thus, CHO cells provide a good cell system to test whether carbohydrate modification of GP Ibα is required for its interaction with P-selectin. The major carbohydrate structure of platelet GP Ibα 35 36 37 is very similar to that reported for PSGL-1 3, the only difference being the lack of an α(1,3)-fucosyl linkage in GP Ibα. We expressed the GP Ib-IX-V complex in CHO cells alone, with FucT VII, or with both FucT VII and the core-2 branching enzyme (C2GnT). We first assessed whether the cells carry the necessary modification by immunostaining with the antibody HECA-452, which recognizes FucT VII–dependent carbohydrate epitopes 19. Whereas the untransfected cells demonstrated only a low background fluorescence, all of the cell lines transfected with both C2GnT and FucT VII demonstrated high levels of the HECA-452 epitope (Fig. 3 A).

Figure 3.

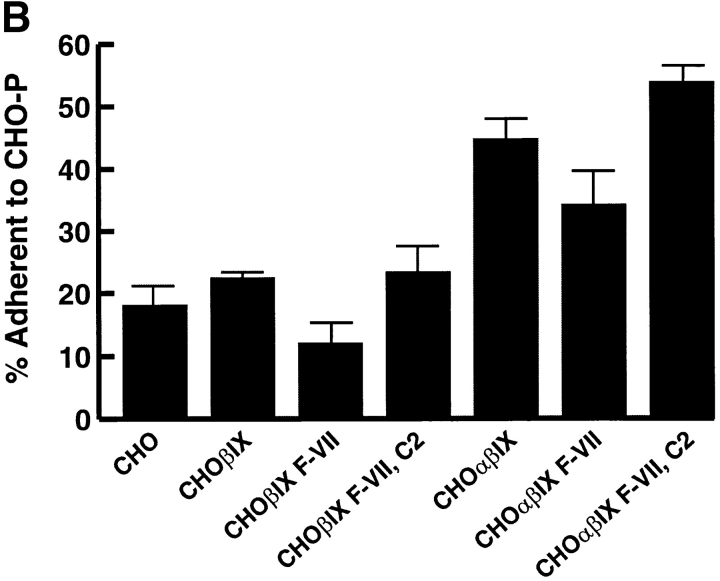

Assessment of the role of carbohydrate modification in the GP Ibα–P-selectin interaction. (A) Expression of the HECA-452 epitope in transfected cells. Cells transfected with cDNAs for FucT VII and C2GnT express the HECA-452 epitope. CHO βIX and CHO αβIX cells were transfected with either a FucT VII expression plasmid alone (F-VII) or together with the expression plasmid for C2GnT (C2). Sham-transfected CHO βIX and CHO αβIX served as negative controls. The appropriate carbohydrate modification was detected by cell surface binding of the antibody HECA-452, which recognizes a FucT VII–dependent epitope. Binding was determined by flow cytometry after labeling the cells with an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. The surface level is expressed as the geometric mean fluorescence of the cell population. HL60 cells served as positive controls for the presence of the carbohydrate modification. (B) Heterotypic aggregation of CHO αβIX and CHO-P cells. Aggregation of green-labeled CHO βIX or CHO αβIX cells with orange-labeled CHO-P cells was induced by coincubating the cells and shaking them on a table-top shaker. The ordinate represents the percentage of the green cells found in coaggregates with orange cells. (C) Inhibition of aggregation by mocarhagin. Before commencement of the aggregation assay, CHO αβIX cells were pretreated with mocarhagin, a cobra venom metalloprotease that selectively removes the GP Ibα NH2 terminus by cleavage between Glu282 and Asp283 16. Adherence of the cells to CHO-P was then determined as in B. Values are depicted as percentages of control binding after subtracting the background adhesion of CHO βIX cells.

We then evaluated the ability of these cells to form heterotypic aggregates with cells expressing P-selectin. Cells expressing the GP Ib-IX-V complex and its components were fluorescently labeled with the membrane-permeable dye CellTracker™ Green, and the CHO-P cells were labeled with CellTracker™ Orange. Equal quantities of the two cell types were mixed and incubated with gentle shaking, and the heterotypic aggregates containing both green and orange cells were quantitated. Cells expressing GP Ibα demonstrated much greater heterotypic aggregation than the control untransfected CHO cells or CHO cells expressing a partial complex lacking GP Ibα (CHO βIX cells) (n = 3, P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test; Fig. 3 B). Expression of the carbohydrate-modifying enzymes led to only a small further increment in the formation of heterotypic aggregates, indicating that carbohydrate modification of GP Ibα is less important to the interaction with P-selectin than is the modification of PSGL-1. This finding is consistent with the lack of calcium dependence of the interaction. Calcium is required for the interaction of P-selectin with certain carbohydrate ligands but not with sulfated glycans such as heparin sulfate and fucoidin, which apparently involves sulfated moieties 17 26 30.

The involvement of the GP Ibα NH2 terminus in binding P-selectin was further implicated by studies with the cobra venom metalloprotease mocarhagin (Fig. 3 C). This protease removes the GP Ibα NNH2 terminus to Glu282, including much of the anionic sulfated region 16. Mocarhagin pretreatment of CHO αβIX cells reduced heterotypic aggregation by ∼50% (n = 3, P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test).

Cells Expressing the GP Ib-IX-V Complex Roll on Immobilized P-Selectin.

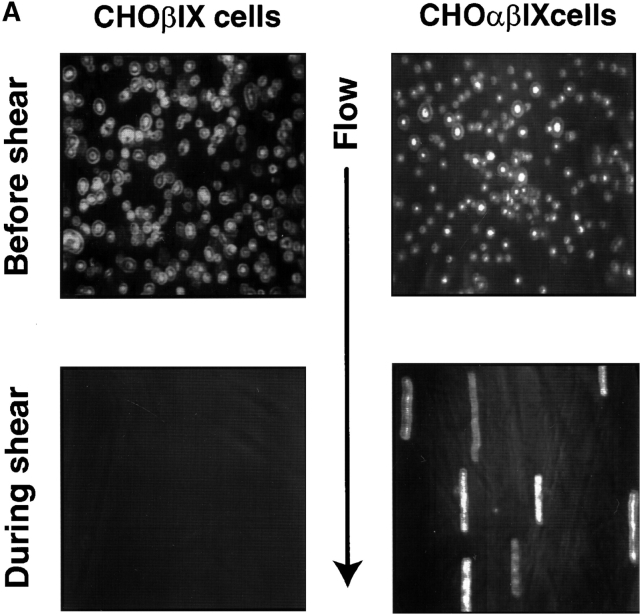

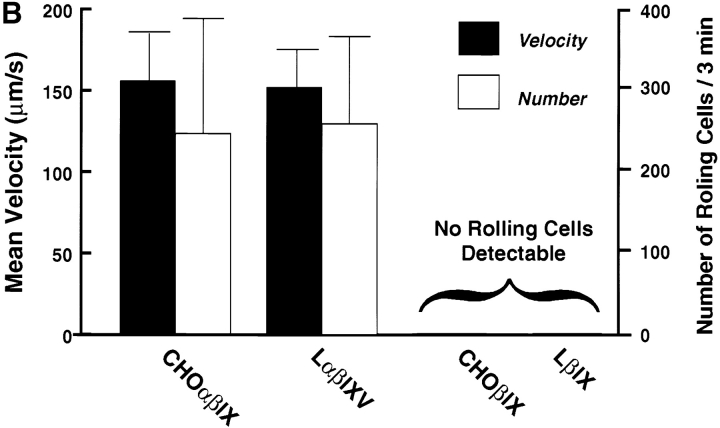

The P-selectin–mediated rolling of platelets on inflamed endothelium requires rapid on and off rates. Thus, for the GP Ib-IX-V complex to constitute a physiological counterreceptor for P-selectin, it should be able to support a similar rolling interaction. To test this possibility, we perfused cells expressing full or partial complexes over coverslips coated with P-selectin in a parallel plate flow chamber at a shear stress of 2 dynes/cm2. Cells were observed to adhere to and roll on P-selectin (Fig. 4 A). The rolling interaction was independent of cell type, as both CHO and L cells expressing the complex rolled at similar velocities, whereas control cells lacking GP Ibα did not adhere or roll (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Rolling of GP Ibα–expressing cells on immobilized P-selectin. (A) CHO cells expressing either the GP Ib-IX complex or only GP Ibβ and GP IX were allowed to settle onto coverslips coated with P-selectin in parallel plate flow chambers. After 1 min, the chambers were perfused with PBS at a constant flow rate to generate a shear stress of 2 dynes/cm2. The top panels show cells before application of shear stress, and the bottom panels show the same region during perfusion. The images in the bottom panels represent a compilation of a series of frames taken over 2 s. The linear blurs represent those cells that have adhered to the matrix and are rolling on it. (B) Velocity and numbers of cells rolling on immobilized P-selectin. Both L and CHO cells were studied, with no significant differences noted between the two in either velocity or number of rolling cells. The presence of GP V also did not influence rolling. No velocity is given for cells lacking GP Ibα because no rolling cells were observed. The number of cells rolling per field were counted during a 3-min interval from the start of the perfusion.

Cells Expressing the GP Ib-IX Complex and Platelets Roll on Histamine-activated Endothelium.

We next tested whether the GP Ib-IX-V complex could also support cell rolling on stimulated endothelial cells. Endothelial cells were collected from human umbilical veins and grown directly on gelatin-coated coverslips. When confluent, they were activated with 25 μM histamine and the coverslip was immediately placed in the parallel plate flow chamber. CHO αβIX cells were then perfused over the monolayer. Negative controls were CHO αβIX cells perfused over untreated endothelium and CHO βIX cells perfused over activated endothelium. CHO αβIX cells adhered to and rolled on the activated endothelial monolayer but not on the unstimulated endothelium (Fig. 5). A low level of CHO βIX adhesion to activated endothelium was noted, but this did not exceed the level of adhesion of these cells to the unstimulated endothelium. Adhesion of the CHO αβIX cells was blocked by the polyclonal antibody against P-selectin (Fig. 5 and Table ).

Figure 5.

Adhesion of GP Ibα–expressing cells to histamine-activated endothelium. HUVEC monolayers were activated by treatment with 25 μM histamine, and the coverslips were immediately placed in the parallel plate flow chamber. Cells were allowed to settle for 2 min, and the chambers were then perfused with PBS.

Table 1.

Number of CHO Cells Rolling on Human Umbilical Vein Endothelium

| Cell lines | Unstimulated | Stimulated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No antibody | Anti–P-selectin | ||

| CHO αβIX | 7.60 ± 1.33 | 33.30 ± 3.62 | 8.00 ± 2.07 |

| CHO βIX | N/A | 4.66 ± 2.03 | N/A |

N/A, not applicable.

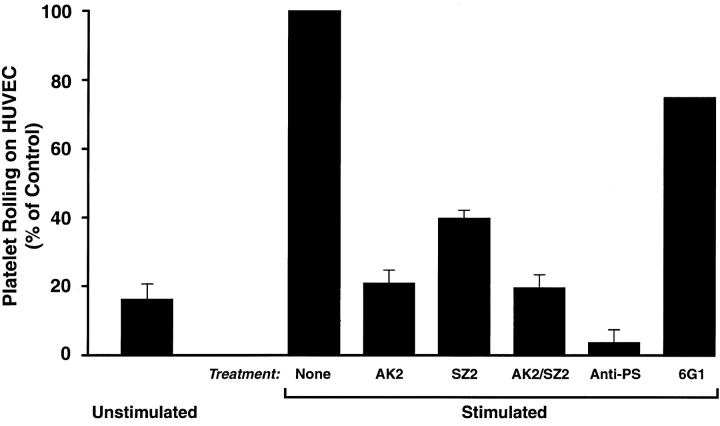

As a final, and more physiological, test of the GP Ib-IX-V complex–P-selectin interaction, we studied the effects of antibodies to GP Ibα and P-selectin on platelet rolling on stimulated endothelium (Fig. 6). Platelet suspensions (2 × 108 platelets/ml and 20% washed erythrocytes in PBS containing calcium and magnesium) were perfused over histamine-stimulated endothelium either without treatment or in the presence of antibodies against GP Ibα (SZ2 and AK2, alone and in combination), P-selectin (polyclonal anti–P-selectin), or von Willebrand factor (6G1). The number of platelets rolling was much greater on activated than on unactivated endothelium. Treatment with the two GP Ibα mAbs markedly inhibited adhesion and rolling of the platelets, with AK2 being a more potent inhibitor, reducing the number of rolling cells to the level seen on unstimulated endothelial cells. (We did not use AK2 in the experiments examining CHO-P adhesion to glycocalicin because it does not bind to immobilized glycocalicin.) Anti–P-selectin decreased platelet rolling to levels even below those of the unstimulated endothelial cells, suggesting a background level of endothelial cell activation. The anti–von Willebrand factor mAb, 6G1, did not significantly affect platelet rolling.

Figure 6.

Platelet rolling on activated endothelium. Platelet suspensions (600 μl at 2 × 108 platelets/ml in buffer containing 20% washed erythrocytes) were incubated with HUVEC monolayers (prepared as for Fig. 5) for 2 min and then perfused over the monolayer for an additional 3 min. Rolling platelets were counted per 60× field over the 3-min perfusion. The experiment was performed three times (except for the 6G1 inhibition, which was only performed once), and values are expressed as percentages of the numbers of cells rolling on the histamine-stimulated endothelium. 100% for the stimulated, untreated cells ranged from 16 to 21 cells/min. The decrease in rolling in cells treated with either GP Ibα or P-selectin antibodies was statistically significant (n = 3, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test).

Discussion

Here we demonstrate a specific interaction between a platelet adhesion receptor, the GP Ib-IX-V complex, and P-selectin. This interaction represents a potential new paradigm for platelet adhesion, where the same receptor (GP Ib-IX-V) can support platelet adhesion to endothelial cells under the appropriate conditions of endothelial activation and to the subendothelial matrix when the endothelial cells have been removed by injury. Several interesting parallels exist between GP Ibα and PSGL-1 as cell adhesion receptors. Both are membrane mucins with elongated structures formed by the presence of a heavily O-glycosylated region rich in threonine, serine, and proline residues 38 39. In both receptors, this mucin-like region separates the ligand-binding region from the plasma membrane 40 41, and in both it contains tandemly repeated sequences that account for polymorphism in the human population because of variable numbers of the tandem repeats 42 43. The major carbohydrate structures of the two receptors are very similar, with only a fucose in α(1,3) linkage in the major PSGL-1 carbohydrate chain differentiating it from the major carbohydrate species of GP Ibα. Furthermore, both receptors contain a highly acidic region with sulfated tyrosines that is important for ligand binding and lies immediately NH2-terminal to the mucin-like region 4 5 6 7 14 15 16. The major ligands for both receptors (von Willebrand factor and P-selectin) are synthesized only in megakaryocytes and endothelial cells and are stored in the same subcellular compartments, the α-granules of platelets and megakaryocytes and the Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells.

Despite all of these similarities, the interactions of the two mucins with P-selectin are quite different. Whereas PSGL-1 requires carbohydrate modification with core-2 branching and α(1,3)-fucosylation and the presence of calcium for its interaction with P-selectin, GP Ibα requires neither. This lack of a requirement for carbohydrate modification is consistent with the findings of Frenette et al. 8 that the platelet P-selectin counterreceptor does not require modification by FucTs for function.

The different carbohydrate requirements of the two P-selectin counterreceptors may not be absolute but rather may represent a difference in the relative importance of the two P-selectin binding determinants (carbohydrates and sulfated tyrosines). GP Ibα does not contain the fucosylated moiety that is so vital for PSGL-1; on the other hand, its anionic region has a much higher concentration of negative charge than does the analogous region of PSGL-1, as well as three tyrosines that are fully sulfated 14 16. This region of GP Ibα is known to bind tightly to thrombin and does so by interacting with the same region of thrombin that binds heparin 31 32. Thus, the anionic sulfated region of GP Ibα, with its high negative charge and sulfate groups, appears to resemble heparin. Several lines of evidence point to the importance of this heparin-like region of GP Ibα in the interaction with P-selectin. First, the calcium independence of the interaction resembles the interaction of P-selectin with heparin, as does the pattern of blockade with heparin and fucoidin, but not with chondroitin sulfate 17. Second, the interaction is inhibited by SZ2, an mAb that binds within the region and also partially blocks botrocetin-induced von Willebrand factor binding, a phenomenon known to be sensitive to the removal of tyrosine sulfates 15 16. Finally, mocarhagin, the cobra venom metalloprotease that removes most of the heparin-like region, also inhibits binding. Thus, the GP Ibα–P-selectin interaction is almost completely independent of carbohydrate, although the failure of SZ2 or mocarhagin to fully inhibit the interaction suggests that carbohydrate may have a minor role.

The possible involvement of other regions of GP Ibα in the interaction is also suggested by the inhibition by the mAb AK2 of platelet rolling on stimulated endothelial cells. This antibody binds within the leucine-rich repeats of GP Ibα 16. However, because the three-dimensional relationship of the leucine-rich repeats with the sulfated region in three dimensions is not known, we cannot definitively make a case for the involvement of the leucine-rich repeats in the interaction. The potential involvement of all of the regions of GP Ibα will have to await more definitive studies with mutant polypeptides.

The adhesion of platelets to regions of vessel wall injury mediated by von Willebrand factor can occur at very high shear stresses, approaching 100 dynes/cm2. The interaction between platelets and endothelium, on the other hand, seems to occur at much lower shear stresses, although evidence exists that platelets can interact with endothelium at shear stresses above those able to support the interaction of leukocytes with the endothelium 44. The studies reported here were carried out at venular shear stresses and do not address the possibility that the GP Ibα–P-selectin interaction may be able to support platelet rolling at shear stresses much higher than those that support leukocyte rolling.

The demonstration of an abundant receptor on the platelet surface for P-selectin brings into sharp focus the potential roles of this receptor–counterreceptor interaction in both physiological and pathological conditions. During hemostasis, the interface between the GP Ib-IX-V complex and P-selectin may be important in the interaction between activated and unactivated platelets. Activated platelets with surface-exposed P-selectin could associate with and activate previously unactivated platelets, thus providing a mechanism for propagation of platelet thrombi. Failure of this mechanism could explain the mild bleeding diathesis of P-selectin–deficient mice 45 and could contribute to the bleeding tendency in patients with Bernard-Soulier syndrome, the genetic disorder resulting from deficiency of the GP Ib-IX-V complex 46. Nevertheless, this mechanism is likely to be only of secondary importance, as no defect in aggregation has been found in the platelets of patients with Bernard-Soulier syndrome (although a subtle defect might not be detected by conventional methods of performing aggregation).

Under certain circumstances, platelets may help neutrophils and other white cells to exit the vasculature by providing an additional ligand for recognizing activated endothelial cells. Such a role has been demonstrated for platelets in lymphocyte trafficking, where activated platelets bound to the lymphocytes can provide a ligand (P-selectin) for the endothelial addressins of lymph nodes 47. Platelets interacting with activated endothelium may themselves become activated, releasing factors that may influence the behaviors of both the endothelial cells and underlying smooth muscle cells. When such a process is unchecked, such as during sepsis, the platelets may contribute to the deleterious effects of the underlying condition. In this regard, recent findings suggest that activated platelets also form stable attachments with endothelial cells mediated in part by other platelet GP receptors, such as the integrin GP IIb-IIIa 48. At this point, however, the potential biological consequences of platelet interaction with endothelium are speculative. Nevertheless, with the demonstration of such a specific interaction involving endothelial selectins 9 and the current identification of a platelet receptor for these selectins, the endothelium can no longer be considered refractory to the overtures of the platelet.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. John Lowe, Minoru Fukuda, and C. Wayne Smith for generously providing reagents and Dr. Robert Andrews for helpful discussions.

We also gratefully acknowledge grant support from the National Institutes of Health (grants HL54218 to J.A. López and HL18672 to L.V. McIntire) and the National Heart Foundation of Australia (to M.C. Berndt). J.A. López and G.S. Kansas are Established Investigators of the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

1used in this paper: ANOVA, analysis of variance; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; FucT, fucosyl transferase; GP, glycoprotein; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; PSGL-1, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1

References

- Springer T.A. Traffic signals on endothelium for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1995;57:827–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.004143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansas G.S. Selectins and their ligandscurrent concepts and controversies. Blood. 1996;88:3259–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins P.P., McEver R.P., Cummings R.D. Structures of the O-glycans on P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 from HL-60 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:18732–18742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako D., Comess K.M., Barone K.M., Camphausen R.T., Cumming D.A., Shaw G.D. A sulfated peptide segment at the amino terminus of PSGL-1 is critical for P-selectin binding. Cell. 1995;83:323–331. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouyani T., Seed B. PSGL-1 recognition of P-selectin is controlled by a tyrosine sulfation consensus at the PSGL-1 amino terminus. Cell. 1995;83:333–343. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins P.P., Moore K.L., McEver R.P., Cummings R.D. Tyrosine sulfation of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is required for high affinity binding to P-selectin. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:22677–22680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca M., Dunlop L.C., Andrews R.K., Flannery J.V., Ettling R., Cumming D.A., Veldman M., Berndt M.C. A novel cobra venom metalloproteinase, mocarhagin, cleaves a 10-amino acid peptide from the mature N terminus of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand receptor, PSGL-1, and abolishes P-selectin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:26734–26737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenette P.S., Johnson R.C., Hynes R.O., Wagner D.D. Platelets roll on stimulated endothelium in vivoan interaction mediated by endothelial P-selectin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:7450–7454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenette P.S., Moyna C., Hartwell D.W., Lowe J.B., Hynes R.O., Wagner D.D. Platelet-endothelial interactions in inflamed mesenteric venules. Blood. 1998;91:1318–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López J.A., Dong J.F. Structure and function of the glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 1997;4:323–329. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199704050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage B., Saldivar E., Ruggeri Z.M. Initiation of platelet adhesion by arrest onto fibrinogen or translocation on von Willebrand factor. Cell. 1996;84:289–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B.J., Dong J.F., McIntire L.V., López J.A. Shear-dependent rolling on von Willebrand factor of mammalian cells expressing the platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex. Blood. 1998;92:3684–3693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranmer S.L., Ulsemer P., Cooke B.M., Salem H.H., de La Salle C., Lanza F., Jackson S.P. Glycoprotein (GP) Ib-IX-transfected cells roll on a von Willebrand factor matrix under flow. Importance of the GPIb/actin-binding protein (ABP-280) interaction in maintaining adhesion under high shear. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:6097–6106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J.-F., Li C.Q., López J.A. Tyrosine sulfation of the GP Ib-IX complexidentification of sulfated residues and effect on ligand binding. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13946–13953. doi: 10.1021/bi00250a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese P., Murata M., Mazzucato M., Pradella P., De Marco L., Ware J., Ruggeri Z.M. Identification of three tyrosine residues of glycoprotein Ibα with distinct roles in von Willebrand factor and α-thrombin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:9571–9578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C.M., Andrews R.K., Smith A.I., Berndt M.C. Mocarhagin, a novel cobra venom metalloproteinase, cleaves the platelet von Willebrand factor receptor glycoprotein Ibα. Identification of the sulfated tyrosine/anionic sequence Tyr-276-Glu-282 of glycoprotein Ibα as a binding site for von Willebrand factor and α-thrombin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4929–4938. doi: 10.1021/bi952456c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner M.P., Lucas C.M., Burns G.F., Chesterman C.N., Berndt M.C. GMP-140 binding to neutrophils is inhibited by sulfated glycans. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:5371–5374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt M.C., Du X., Booth W.J. Ristocetin-dependent reconstitution of binding of von Willebrand factor to purified human platelet membrane glycoprotein Ib-IX complex. Biochemistry. 1988;27:633–640. doi: 10.1021/bi00402a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagers A.J., Stoolman L.M., Kannagi R., Craig R., Kansas G.S. Expression of leukocyte fucosyltransferases regulates binding to E-selectinrelationship to previously implicated carbohydrate epitopes. J. Immunol. 1997;159:1917–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagers A.J., Stoolman L.M., Craig R., Knibbs R.N., Kansas G.S. An sLex-deficient variant of HL60 cells exhibits high levels of adhesion to vascular selectinsfurther evidence that HECA-452 and CSLEX1 monoclonal antibody epitopes are not essential for high avidity binding to vascular selectins. J. Immunol. 1998;160:5122–5129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess D., Schaller J., Rickli E.E., Clemetson K.J. Identification of the disulphide bonds in human platelet glycocalicin. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991;199:389–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariscalco M.M., Tcharmtchi M.H., Smith C.W. P-selectin support of neonatal neutrophil adherence under flowcontribution of L-selectin, LFA-1, and ligand(s) for P-selectin. Blood. 1998;91:4776–4785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López J.A., Leung B., Reynolds C.C., Li C.Q., Fox J.E.B. Efficient plasma membrane expression of a functional platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX complex requires the presence of its three subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:12851–12859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López J.A., Weisman S., Sanan D.A., Sih T., Chambers M., Li C.Q. Glycoprotein (GP) Ibβ is the critical subunit linking GP Ibα and GP IX in the GP Ib-IX complex. Analysis of partial complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:23716–23721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J.-F., Li C.Q., Sae-Tung G., Hyun W., Afshar-Kharghan V., López J.A. The cytoplasmic domain of glycoprotein (GP) Ibα constrains the lateral diffusion of the GP Ib-IX complex and modulates von Willebrand factor binding. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12421–12427. doi: 10.1021/bi970636b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner M.P., Fournier D.J., Andrews R.K., Gorman J.J., Chesterman C.N., Berndt M.C. Characterization of human platelet GMP-140 as a heparin-binding protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989;164:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91821-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D.A., Abbassi O., McIntire L.V., McEver R.P., Smith C.W. P-selectin mediates neutrophil rolling on histamine-stimulated endothelial cells. Biophys. J. 1993;65:1560–1569. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence M.B., McIntire L.V., Eskin S.G. Effect of flow on polymorphonuclear leukocyte/endothelial cell adhesion. Blood. 1987;70:1284–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukreti S., Konstantopoulos K., Smith C.W., McIntire L.V. Molecular mechanisms of monocyte adhesion to interleukin-1β-stimulated endothelial cells under physiologic flow conditions. Blood. 1997;89:4104–4111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig A., Norgard-Sumnicht K., Linhardt R., Varki A. Differential interactions of heparin and heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans with the selectins. Implications for the use of unfractionated and low molecular weight heparins as therapeutic agents. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:877–889. doi: 10.1172/JCI1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Candia E., De Cristofaro R., De Marco L., Mazzucato M., Picozzi M., Landolfi R. Thrombin interaction with platelet GpIbrole of the heparin binding domain. Thromb. Haemost. 1997;77:735–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.Q., Vindigni A., Di Cera A., Sadler J.E., Wardell M.R. Thrombin binding to platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX is mediated by its anion binding exosite II and is largely electrostatic in nature. Blood. 1997;90:430a. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins N., Parekh R.B., James D.C. Getting the glycosylation rightimplications for the biotechnology industry. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996;14:975–981. doi: 10.1038/nbt0896-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Wilkins P.P., Crawley S., Weinstein J., Cummings R.D., McEver R.P. Post-translational modification of recombinant P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 required for binding to P- and E-selectin. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson P.A., Anstee D.J., Clamp J.R. Isolation and characterization of the major oligosaccharide of human platelet membrane glycoprotein GPIb. Biochem. J. 1982;205:81–90. doi: 10.1042/bj2050081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korrel S.A.M., Clemetson K.J., Van Halbeek H., Kamerling J.P., Sixma J.J., Vliegenthart J.F.G. Structural studies on the O-linked carbohydrate chains of human platelet glycocalicin. Eur. J. Biochem. 1984;140:571–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji T., Tsunehisa S., Watanabe Y., Yamamoto K., Tohyama H., Osawa T. The carbohydrate moiety of human platelet glycocalicin. The structure of the major ser/thr-linked chain. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:6335–6339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López J.A., Chung D.W., Fujikawa K., Hagen F.S., Papayannopoulou T., Roth G.J. Cloning of the α chain of human platelet glycoprotein Iba transmembrane protein with homology to leucine-rich α2-glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:5615–5619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako D., Chang X.-J., Barone K.M., Vachino G., White H.M., Shaw G., Veldman G.M., Bean K.M., Ahern T.J., Furie B. Expression cloning of a functional glycoprotein ligand for P-selectin. Cell. 1993;75:1179–1186. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90327-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J.E.B., Aggerbeck L.P., Berndt M.C. Structure of the glycoprotein Ib-IX complex from platelet membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:4882–4890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Erickson P., James J.A., Moore K.L., Cummings R.D., McEver R.P. Visualization of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 as a highly extended molecule and mapping of protein epitopes for monoclonal antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:6342–6348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López J.A., Ludwig E.H., McCarthy B.J. Polymorphism of human glycoprotein Ibα results from a variable number of tandem repeats of a 13-amino acid sequence in the mucin-like macroglycopeptide region. Structure/function implications. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:10055–10061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afshar-Kharghan V., Diz-Küçükaya R., Berndt M.C., López J.A. Polymorphism of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 in human populations based on the presence of variable numbers of tandem repeats in the mucin-like region. Blood. 1998;92:18a. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massberg S., Enders G., Leiderer R., Eisenmenger S., Vestweber D., Krombach F., Messmer K. Platelet-endothelial cell interactions during ischemia/reperfusionthe role of P-selectin. Blood. 1998;92:507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam M., Frenette P.S., Saffaripour S., Johnson R.C., Hynes R.O., Wagner D.D. Defects in hemostasis in P-selectin–deficient mice. Blood. 1996;87:1238–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López J.A., Andrews R.K., Afshar-Kharghan V., Berndt M.C. Bernard-Soulier syndrome. Blood. 1998;91:4397–4418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diacovo T.G., Puri K.D., Warnock R.A., Springer T.A., von Andrian U.H. Platelet-mediated lymphocyte delivery to high endothelial venules. Science. 1996;273:252–255. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombeli T., Schwartz B.R., Harlan J.M. Adhesion of activated platelets to endothelial cellsevidence for a GPIIbIIIa-dependent bridging mechanism and novel roles for endothelial intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), αvβ3 integrin, and GPIbα. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:329–339. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]