Abstract

The majority of lymphomas induced in Rag-deficient mice by Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMuLV) infection express the CD4 and/or CD8 markers, indicating that proviral insertions cause activation of genes affecting the development from CD4−8− pro-T cells into CD4+8+ pre-T cells. Similar to MoMuLV wild-type tumors, 50% of CD4+8+ Rag-deficient tumors carry a provirus near the Pim1 protooncogene. To study the function of PIM proteins in T cell development in a more controlled setting, a Pim1 transgene was crossed into mice deficient in either cytokine or T cell receptor (TCR) signal transduction pathways. Pim1 reconstitutes thymic cellularity in interleukin (IL)-7– and common γ chain–deficient mice. In Pim1-transgenic Rag-deficient mice but notably not in CD3γ-deficient mice, we observed slow expansion of the CD4+8+ thymic compartment to almost normal size. Based on these results, we propose that PIM1 functions as an efficient effector of the IL-7 pathway, thereby enabling Rag-deficient pro-T cells to bypass the pre-TCR–controlled checkpoint in T cell development.

Keywords: common γ chain, IL-7, Rag, proviral tagging, lymphomagenesis, pre-T cell development

Intrathymic development of lymphoid precursors into mature α/β T cells takes place in a series of distinct maturation steps that depend on the signaling pathways of antigen and cytokine receptors (for review see references 1 and 2). Each stage is defined by a unique pattern of gene expression and specific surface markers. For the differentiation and expansion of CD4−8− (double negative [DN])1 pro-T cells that have their TCR genes in germline configuration, the IL-7R appears to be most critical. The IL-7R comprises the IL-7Rα chain (CD127) and the common cytokine receptor γ chain (γc, CD132). The latter is also a constituent of the IL-2, IL-4, IL-9, and IL-15 receptors 3 4. Although α/β T cell development is observed in IL-7–, IL-7Rα–, or γc-mutant mice, the number of thymocytes is significantly reduced 5 6 7 8 9 10, implying a signal of cytokine receptors in controlling the size of the thymic T cell compartment.

Pro-T cell development is characterized by the differential expression of CD25 (IL-2Rα chain) and CD44 (Pgp-1) markers: from CD25−44hi to CD25+44hi and finally into CD25+44−/lo. The latter rearrange TCR-β genes. The subsequent formation and expression of pre-TCR–CD3 complexes at the surfaces of these early pre-T cells represents a second checkpoint of T cell development. This allows development to continue through a CD4−8−25−44−, CD4−8+25−44− (immature single positive [ISP]), and finally a CD4+8+ (double positive [DP]) CD25−44− stage of development 2. Pre-T cell development is accompanied by an exponential increase in the number of α/β T cell precursors ,as well as the onset of TCR-α germline transcription. This allows efficient rearrangement at the TCR-α gene locus, leading to further development of immature DP α/β T cells. As this process of differentiation and proliferation is initiated in thymocytes with a functionally rearranged TCR-β gene, it has collectively been termed “β-selection” 11. Consequently, β-selection is lacking in recombination-deficient SCID or Rag-deficient mice, resulting in a differentiation block at the CD4−8−25+44− stage of α/β T cell development 12 13 14.

Several lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinases are critical for pre-TCR signaling. In the absence of functional Lck 15 or in the presence of high levels of catalytically inactive LckR273 16, differentiation of most T cells is arrested at the CD4−8−25+44− stage. Accordingly, a constitutive active mutant of p56lckF505 (LckF) can bypass the pre-TCR–dependent checkpoint and β-selection in Rag1-deficient mice 17. In summary, the above data indicate the importance of intact cytokine- and TCR–CD3-signaling pathways for normal β-selection.

Transformation by the lymphotropic Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMuLV), a slow-transforming retrovirus, is a multistep process. Proviral activation of a protooncogene can provide a selective advantage to the target cell and cause its clonal expansion. Subsequent reinfections and provirus insertions near other protooncogenes can lead to the malignant outgrowth of monoclonal or oligoclonal tumors 18. Independent tumors that harbor a provirus insertion in the same locus share a so-called “common proviral insertion site.” Characterization of these common proviral insertion sites led to the discovery of a large number of protooncogenes. In most instances, the protooncogenes are activated through promoter or enhancer insertion. These genes appear to fulfill key roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival 19.

The Pim1 protooncogene encodes a serine/threonine protein kinase and was found as a frequent “common proviral insertion site” in MoMuLV-induced B and T cell lymphomas. Pim1 is a member of a small family of highly homologous kinases, including Pim1, Pim2 20, and Pim3 (also named Kid1) 21, and all members are expressed in the thymus. Overexpression of each of these members can promote lymphomagenesis in mice (22; our unpublished results). Pim1 was shown to be a particularly efficient collaborator of the Myc oncogene in tumor induction. Mice transgenic for both Myc and Pim1 succumbed from tumors around birth 23. However, Pim1-deficient mice did not show obvious abnormalities except an impairment of cytokine-mediated proliferation of mast cells and pre-B cells 24 25 26, which might be explained by a functional redundancy of the Pim proteins. Recently, Schmidt et al. reported evidence implicating a role for PIM1 in promoting β-selection 27.

In this report, we have studied the capacity of Pim1 28 29 to compensate for the T cell differentiation and expansion defects in various immunodeficient mouse strains.

Materials and Methods

Generation of γc-Mutant Mice.

Phage clones representing the γc locus were isolated from a 129/SV library (Stratagene Inc.) using a γc cDNA probe. The SalI inserts of the phage were inserted into pGEM11Zf and further characterized. A 4-kbp BamHI fragment carrying all coding exons of the γc gene was replaced by the pgk-hygromycin selection cassette to generate the targeting construct. Homologous recombination results in the deletion of the complete coding region of the γc gene. The resulting SalI targeting fragment was excised from the pGEM11 vector and electroporated into 129/Ola (E14) ES cells as described 30. Hygromycin-resistant colonies were analyzed for homologous recombination by Southern blot. Targeted ES cell clones were used for injection into B6 blastocysts as described 31. Chimeric males were mated to B6 or FVB/N females to obtain γc heterozygous female offspring. Mice deficient for γc were obtained by subsequent intercrosses.

Mice.

The generation and typing of Rag2-deficient mice 14, CD3γ-deficient mice 32, and Eμ-Pim1– 33 and Bcl2-Ig–transgenic 34 mice have been described elsewhere. Transgenic mice were crossed with Rag2-deficient mice. Transgenic offspring was further crossed with Rag2 knockout mice. The resulting transgenic and nontransgenic heterozygous and homozygous Rag2-mutant mice were used for analysis. Mice were kept in isolators under specific pathogen–free conditions.

MoMuLV Infection.

200 one- to three-day-old Rag2-deficient mice were injected with 2.5 × 105 MoMuLV 35, and 185 mice were monitored two to three times weekly over a period of 200 d for the development of tumors. Mice were killed when moribund and single-cell suspensions of lymphomas were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry.

Upon euthanasia, thymi were dissected and single-cell suspensions were prepared by mincing the lymphoid tissues through a nylon mesh (Cell Strainer; Becton Dickinson). Lymphocyte counts were performed in a Sysmex Toa F800 microcell counter or in a Coulter Counter (Coulter Electronics Ltd.). Single cells were kept at 4°C in PBA (1× PBS, 0.5% BSA, and 0.05% sodium azide). The mAbs anti-CD3∈ (clone 145-2C11), anti-CD4 (clone RM-4-5), anti-CD5 (clone 53-7.3), anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7), anti-CD24 (heat-stable antigen, clone M1/69), anti-CD25 (clone 7D4), anti-CD44 (Pgp1, Ly-24, clone IM7), anti-CD90.2 (Thy1.2, clone 53-2.1), anti-Nk1.1, and anti–TCR-β (H57-597) were purchased from PharMingen. FITC, PE, and/or biotin conjugates thereof were used for immunofluorescence. Cells (106) were incubated in 96-well U-bottom plates for 20 min at 4°C in 20 μl PBA and saturating amounts of mAbs. Cells were washed twice with PBA. Cells incubated with biotin-conjugated mAb were subsequently either stained by incubation with PE-conjugated streptavidin (double stainings) or by incubation with Cy-Chrome–conjugated streptavidin (triple stainings). After washing twice, flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCalibur™ (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using CellQuest™ software.

Anti-CD3 Treatment and Sorting of Pre-T Cell Subsets.

CD4−8−25+44− thymocytes were identified and sorted directly from Rag2-deficient thymi by four-color staining using anti-CD4 (APC-conjugated), anti-CD8 (PE-conjugated), anti-CD25 (biotinylated), and anti-CD44 (FITC-conjugated) mAbs. The biotinylated CD25-specific mAb was indirectly stained with streptavidin–Red613. To induce pre-T cell development in Rag2-deficient mice, Rag2-deficient mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 100 μg of HPLC-purified, CD3∈-specific mAb 145-2C11 in 200 μl PBS. CD4−8−25−44− (quadruple negative), CD4−8+25−44− (ISP), and CD4+8+25−44− (DP) thymocytes were sorted 2–4 d after treatment with anti-CD3. The sorted thymocyte fractions were pelleted and kept at −70°C. Total RNA was isolated using RNA-easy anion exchange columns (QIAGEN Inc.).

Reverse Transcriptase–PCR Analysis.

10 ng of total RNA from each thymocyte fraction was used to analyze the expression of Pim1, Pim2, c-myc, N-myc, and β-actin by reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR. For this purpose, we used the SuperScript™ One-Step™ RT-PCR System (GIBCO Life Technologies) in combination with one of the following gene-specific primer sets: β-actin, GCACCACAACCTTCTACAATGAGCTG (sense) and CACGCTCGGTCAGGATCTTCATGAG (antisense); Pim1, GACTTCTGGACTGGTTCGAGAGG (sense) and CCCTTGATGATCTCTTCATCGTGC (antisense); Pim2, TTGCGCTGCTGTGG-AAGGTGGG (sense) and GGGAGACATGAGCAGGGAAGTG (antisense); N-myc, AGAGTCGGCGTCGGTGCCCGC (sense) and GGGCGTGGAGAAGCCTCGCTC (antisense); and c-myc, CCGCTCAACGACAGCAGCTCG (sense) and CCAATTCAGGGATCTGGTCACGC (antisense).

The PCR program was as follows: 50°C for 30 min and 94°C for 2 min, followed by 30 or 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s. One-fifth of each reaction was analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel. Very similar results were obtained with total RNA isolated from independent sorts.

DNA and RNA Analysis.

The analysis of proviral integrations was performed as described 36. Total RNA was isolated from frozen tissue samples using anion exchange columns (QIAGEN Inc.). TCR-α germline transcripts were identified by Northern blot analysis as described in 37.

Results

Pre-TCR–independent Differentiation in MoMuLV-infected Rag-deficient T Cell Tumors.

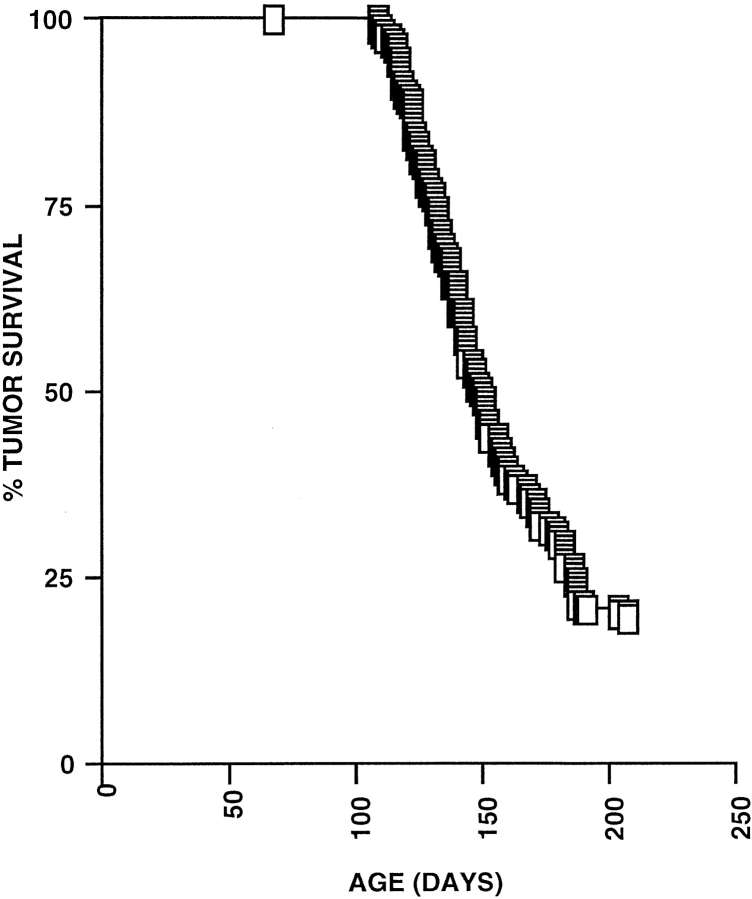

Previously, we have shown that provirus tagging in Rag-deficient mice might be a suitable technique to identify genes involved in the control of early T cell development 38. Therefore, 185 Rag2-deficient newborn mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with MoMuLV. Thymic lymphomas developed at very high incidence. The average latency period was 150 d (Fig. 1). Within 200 d, 81% (150/185) of the mice had developed lymphomas. The tumor incidence of MoMuLV-infected Rag-mutant mice was comparable to that observed previously in wild-type mice 35. These data further indicate that (a) MoMuLV infects and transforms pro-T cells of Rag-mutant mice and (b) MoMuLV-induced lymphomagenesis does not depend on a functional V(D)J recombinase nor on the presence of mature lymphocytes.

Figure 1.

Incidence of T cell lymphomas in MoMuLV-infected Rag2-deficient mice. MoMuLV-infected Rag2-deficient newborn mice develop T cell lymphomas at a very high incidence, with an average latency period of 150 d. Within 200 d, 81% (150/185) of the mice had developed lymphomas. The tumor incidence and LD50 (150 d) of MoMuLV-infected Rag-mutant mice are comparable to those observed previously in MoMuLV-infected wild-type mice 35.

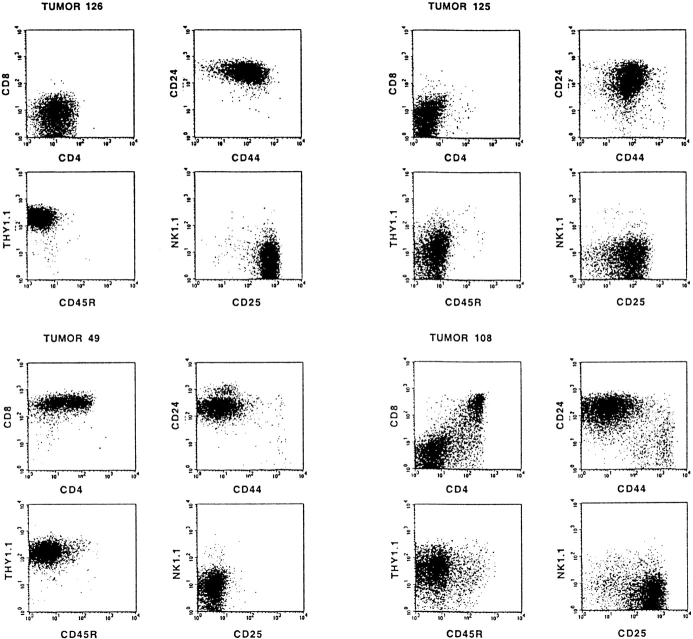

The differentiation stage of each tumor was determined by flow cytometry using mAbs specific for CD4, CD8, CD25, CD24 (heat-stable antigen), CD44, CD45R (B220), CD90 (Thy1.2), and NK1.1. Interestingly, in addition to the expected phenotype of differentiation-arrested DN Rag-mutant thymocytes, the phenotype of most tumors (87%) resembled that of further matured T cell precursors. Representative examples showing the differentiation spectrum of these tumors from DN, ISP/DP, DN/DP, and DP and differentiating DN/ISP/DP tumors are depicted in Fig. 2. These results indicate that proviral activation of host gene(s), rather than the MoMuLV infection itself, can compensate for the lack of a pre-TCR signal in Rag-mutant mice. However, the identification of DN tumors indicates that transformation of the CD25+ DN thymocyte subset can also occur independent of differentiation.

Figure 2.

Most T cell tumors in MoMuLV-infected Rag2-deficient mice bypass the Rag2-mediated differentiation arrest. Typical examples of FACS™ analysis of MoMuLV-induced T cell lymphomas in Rag2-deficient mice are shown. In Rag-deficient mice, differentiation of thymocytes is arrested at the CD4−8−24+25+44low DN stage of α/β T cell development. Whereas tumors 125 and 126 are representative examples for DN tumors, most lymphomas bypass this differentiation arrest and develop into DP or combined DN/DP immature T cell lymphomas. For example, tumor 49 represents a “transitional tumor” from the ISP to DP stage, tumor 108 is a DN/DP tumor, tumors 103 and 118 are DP, and tumors 130 and 136 are “differentiating tumors” from DN to ISP to DP. The tumors with a mixed phenotype, like 49, 130, and 136, are clonal, as the genomes of sorted fractions carry identical proviral insertions (data not shown).

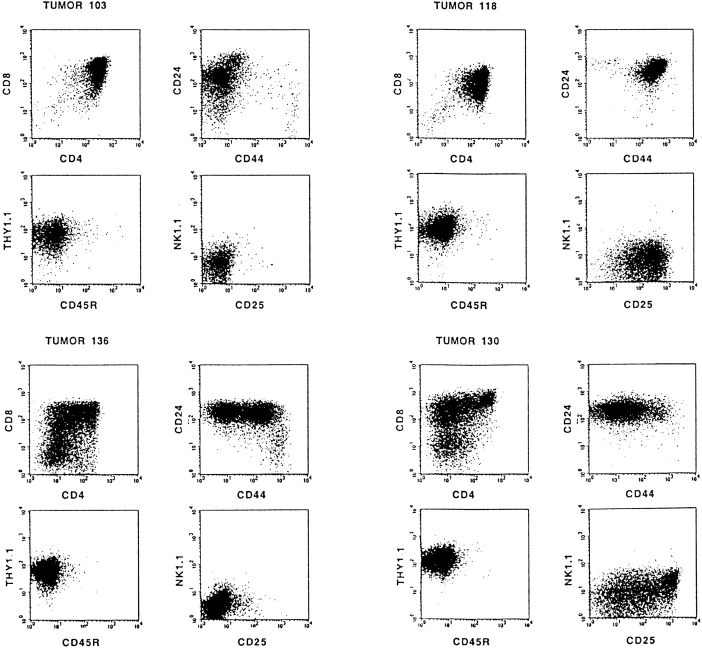

Proviral Insertion into the Pim1 Locus in T Cell Lymphomas at All Developmental Stages.

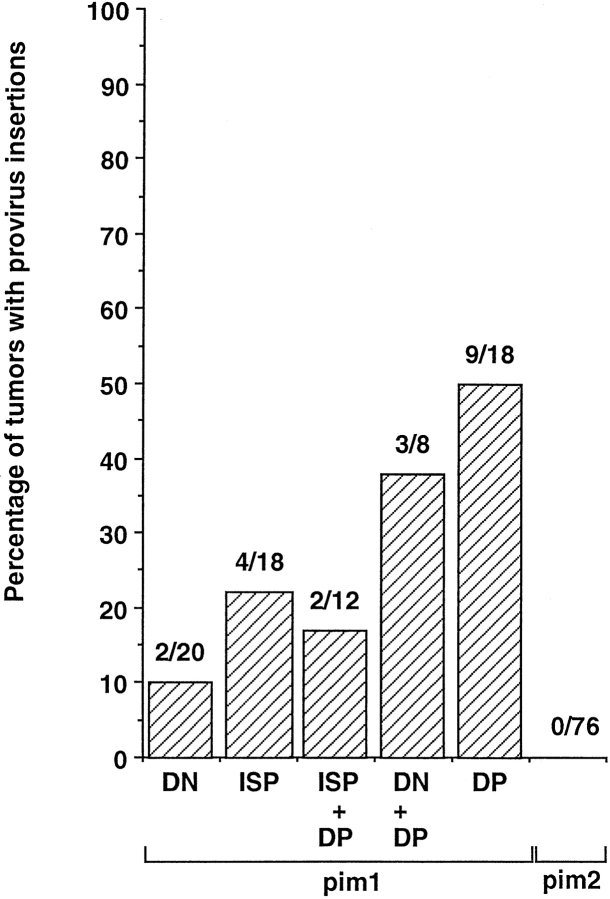

To identify the genes responsible for pre-TCR–independent differentiation in MoMuLV-induced Rag-deficient tumors, the presence of proviral insertions in the loci of known protooncogenes was determined. This was performed for 76 selected tumors that were classified according to the expression of CD4 and CD8 markers. Fig. 3 A summarizes the analysis of proviral insertions into the Pim1 and Pim2 loci of these tumors. 27% (15/56) of the tumors that expressed CD4 and/or CD8 (i.e., differentiated tumors) harbored a proviral insertion near Pim1, as compared with only 10% (2/20) in CD4−8− (undifferentiated) tumors. The differentiation markers of these tumors (79 and 116) displayed a very similar marker spectrum: CD4−8−25lo44hi90lo and CD24− in the case of tumor 79, and CD24+ in the case of tumor 116. Possibly, these tumors are derived from very early thymocytes, where PIM1 is placed in a signaling context able to amplify growth factor receptor signals, which control differentiation and proliferation of DN thymocytes 39. Of the 18 DP tumors, 50% (9/18) carry an insertion near Pim1. As β-selection is associated with an induction of TCR-α germline transcription, the identification of these transcripts in the majority of differentiated tumors supports the differentiation to immature DP T cells (data not shown). No proviral integrations in the Pim2 locus were found in the 76 tumors analyzed from Rag-deficient mice (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Tumor differentiation of MoMuLV-induced Rag-deficient tumors correlates with proviral insertion into the Pim1 locus. 76 selected tumors were classified according to the expression of CD4 and CD8 markers into CD4−8− (DN), CD4−8+24+ or CD4+8−24+ immature single positive (ISP), and CD4+8+ (DP) tumors, as well as tumors with a mixed phenotype, being either ISP and (+) DP or DN and (+) DP. Proviral insertions into the Pim1 and Pim2 loci of these tumors are given as percentages. 27% (15/56) of the tumors that expressed CD4 and/or CD8 (i.e., differentiated tumors) harbor a proviral insertion near Pim1, as compared with only 10% (2/20) in DN (undifferentiated) tumors. In the DP tumors, 50% (9/18) carry an insertion near Pim1. No proviral integrations in the Pim2 locus were found in the 76 tumors analyzed from Rag-deficient mice.

PIM1 Restores Thymus Cellularity in γc- and IL-7–deficient Mice.

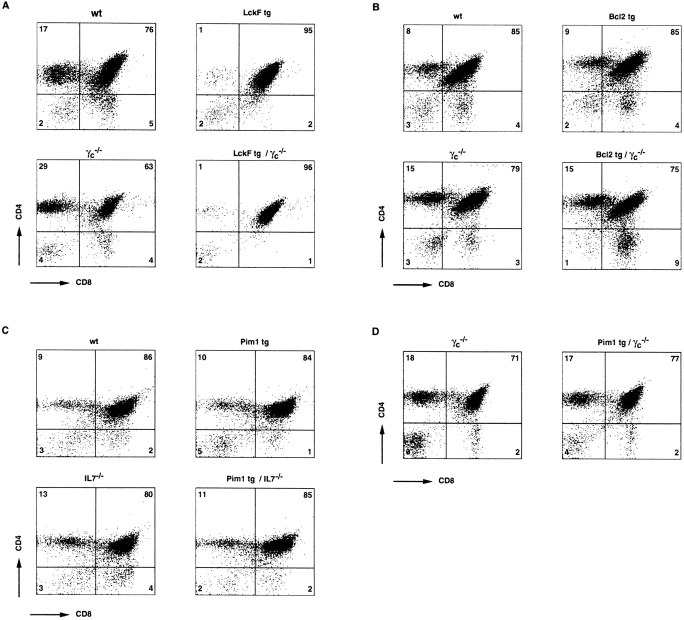

As proviral integrations in the Pim1 locus were found in T cell lymphomas at all developmental stages, albeit at different frequencies, we wanted to address the function of PIM in early T cell development in a more controlled setting. Previous studies on the function of PIM1 implied that this kinase acts downstream of several cytokine receptors expressed on different hematopoietic cell lineages 24 25 26 40 41. As the IL-7–IL-7R complex is critical in controlling the cellularity of the pro-T cell compartment, we crossed Eμ-Pim1–transgenic mice 33 to γc- and IL-7–deficient mice. For comparison, we also introduced the Bcl-2-Ig 34 and LckF transgenes 17 into the γc-mutant background. Although these transgenes are expressed in DN thymocytes (data not shown), only Pim1 was capable of restoring the thymus cellularity to an appreciable extent (Table ), whereas the relative distribution of CD4/CD8 subsets in these thymi was unaltered (Fig. 4 A). These data indicate that Pim1 can compensate to a significant extent for the lack of cytokine signaling, allowing Pim1-transgenic, γc- or IL-7–deficient thymocytes to expand. In line with a recent report 42 but in contrast to data reported by others 43, Bcl2 was only very marginally if at all capable of compensating for the lack of cytokine signaling in the γc-deficient background (Table ), resulting in an unaltered number of thymocytes in these mice (Table and Fig. 4 A). The failure of transgenic TCR and LckF (reference 6 and data not shown) to restore thymic cellularity in γc-deficient thymocytes further supports an important role of cytokine signaling in controlling thymic cellularity independent of pre-TCR signaling. Taken together, these data suggest a role for PIM kinases in T cell cytokine signaling.

Table 1.

PIM1 Compensates for the Lack of Cytokine and Pre-TCR Signaling

| Genotype | No. mice analyzed | No. thymocytes |

|---|---|---|

| ×10−6 | ||

| wt | 4 | 200–300 |

| wt + Bcl2 | 3 | 150–250 |

| wt + LckF | 3 | 200–300 |

| wt + Pim1 | 3 | 250–350 |

| γc −/− | 5 | 10–25 |

| γc −/− + Bcl2 | 3 | 10–20 |

| γc −/− + LckF | 3 | 5–15 |

| γc −/− + Pim1 | 4 | 70–100 |

| γc −/− + Bcl2, LckF | 2 | 5–20 |

| IL-7−/− | 4 | 10–25 |

| IL-7−/− + Pim1 | 3 | 70–100 |

| CD3γ2/− | 5 | 1–2 |

| CD3γ2/− + Pim1 | 3 | 1–2 |

| CD3γ2/− + LckF | 5 | 110–200 (5–8 wk old) |

| Rag2−/− | 4 | 1–3 |

| Rag2−/− + Pim1 | 4 | 150–250 (8–9 wk old) |

| Rag2−/− + Pim1 | 2 | 5–15 (4–5 wk old) |

Figure 4.

CD4/CD8 subsets in the thymi of Pim1-transgenic mice lacking either γc (D) or the IL-7 (C) cytokine. Thymocytes from the indicated mice were analyzed for the relative size of CD4- and/or CD8-expressing thymocyte fractions. For comparison, the LckF (A) and Bcl2 (B) transgenes were also introduced into the γc-deficient background. Whereas LckF promotes differentiation of DN into DP thymocytes irrespective of cytokine signaling, only PIM1 was capable of increasing the absolute numbers of thymocytes in the absence of IL-7– or γc-dependent cytokine signaling (see Table ). wt, wild type.

Pre-T Cell Development in Rag- but not CD3γ-deficient Pim1-transgenic Mice.

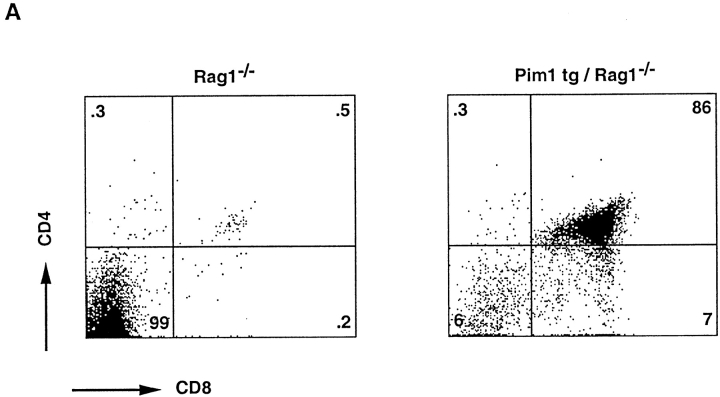

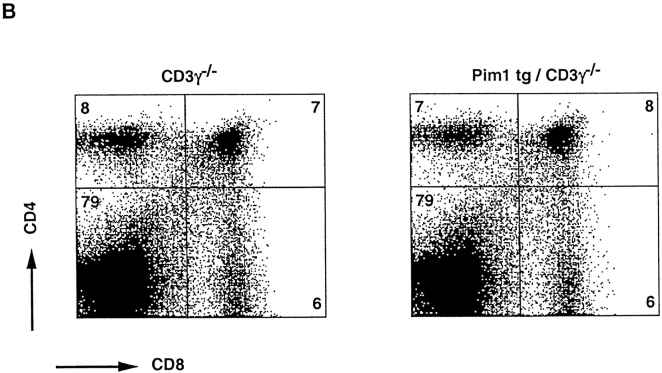

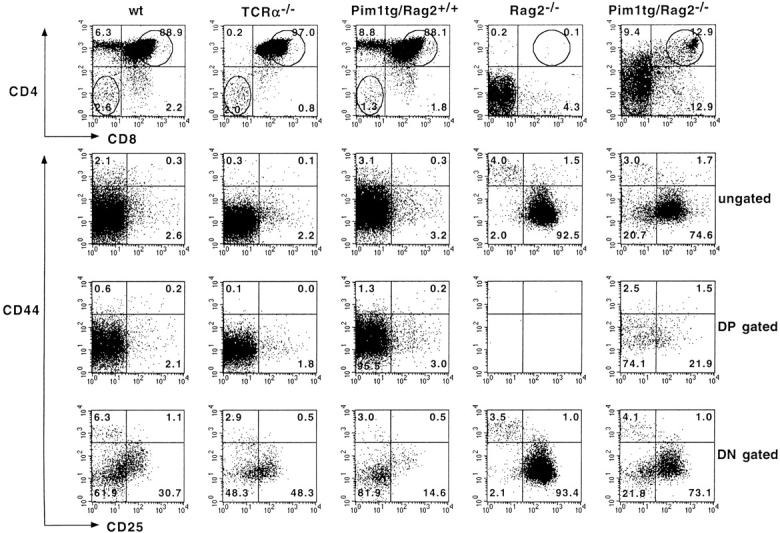

The high incidence of proviral insertions into the Pim1 locus, 50% (9/18) in DP tumors as compared with 10% (2/20) in DN tumors, suggests a potential of PIM1 to facilitate the generation of DP thymocytes. The question of whether the frequent proviral insertions into the Pim1 locus of DP tumors were causally involved in the differentiation into pre-T cell–like tumors was addressed by introducing the Eμ-Pim1 transgene into the Rag-deficient background. Indeed, in Eμ-Pim1–transgenic Rag-deficient mice, we observed differentiation and slow expansion of large DN, CD25+ thymocytes into small resting DP CD25− pre-T cells (Fig. 5 and Table ). The PIM1-mediated differentiation is age dependent. Only 1–2 million DP thymocytes are found at an age of 4–5 wk, but the numbers increase to normal levels (100–200 million) at an age of 8–9 wk (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6 A). This is in contrast to the transgenic expression of LckF in the Rag-deficient background, which results in a normally sized thymus at birth. Both the reduction in cell size, as measured by forward scatter analysis, and the reproducible number of DP thymocytes at a given age argue against transformed DP cells, which is also in line with the slow transforming activity seen in Pim1-transgenic mice 23. These data suggest that PIM kinases synergize with TCR signaling in generating DP thymocytes. As differentiation-arrested Rag-deficient thymocytes still have residual CD3 signaling capacity 44 on the basis of γ∈ modules, we questioned whether differentiation of DN pre-T cells in Eμ-Pim1–transgenic Rag-deficient mice still requires particular CD3 components on the surfaces of pro-T cells of Rag-deficient thymocytes 44 45 46. As a first approach to addressing this question, the Eμ-Pim1 transgene was introduced into the CD3γ-deficient background, in which most thymocytes are blocked at the CD25+ DN stage 32. Strikingly, independent of the age of the mouse, no further differentiation and expansion of Pim1-transgenic CD3γ-deficient pro-T cells was found, which is in strong contrast to Pim1-transgenic Rag-deficient mice (Fig. 6a and Fig. b and Table ). These data suggest that PIM1 cannot act on its own but requires CD3-mediated signals to overcome the T cell differentiation arrest seen in Rag- and CD3γ-deficient mice. In contrast, introduction of the LckF transgene into the CD3γ-deficient background results in restoring the number of thymocytes in these mice (Table ). The constitutively active LckF kinase is capable of bypassing CD3γ deficiency.

Figure 5.

PIM1 induces β-selection in Rag-deficient mice. Four-color FACS™ analysis on Pim1-transgenic thymocytes. Genotypes are given above each dot plot. Numbers within the quadrants indicate percentages. The lower half reveals the CD44/CD25 expression pattern of DP (third panel from left) and DN (fourth panel from left) thymocytes. Circles in the top panels indicate the gating on DN and DP thymocytes. In Rag2-deficient mice, Pim1 induces β-selection, giving rise to a subset of CD25−44− DN thymocytes, which develop into small CD25−44− DP thymocytes.

Figure 6.

PIM1-induced β-selection in Rag-deficient mice is age dependent and lacking in CD3γ-mutant mice. (A) At an age of 8–9 wk, Pim1-transgenic/Rag2-mutant mice have formed a normally sized DP thymocyte compartment. (B) In CD3γ-mutant mice, however, even after 8 wk, Pim1 was incapable of increasing the number of DP thymocytes. Genotypes are indicated above each dot plot. Numbers within the quadrants indicate percentages. See also Table for absolute numbers.

Discussion

Proviral Tagging to Identify Genes Controlling T Cell Development.

Differentiation and proliferation of DN to DP thymocytes is regulated by the expression of a pre-TCR–CD3 complex 2. The exponential expansion of precursor thymocytes during β-selection accounts for a 100-fold increase in the number of precursor T cells. As only a minority of thymocytes will finally fulfill the thymic selection criteria and mature into functional immunocompetent T cells, the expansion of precursor thymocytes during β-selection is a prerequisite for the efficient formation of a diverse peripheral α/β T cell repertoire. Specific growth and/or differentiation signals are required for this expansion and could also play a role in malignant transformation. However, the observation that ∼10% of the T cell lymphomas isolated from MoMuLV-infected Rag-deficient mice had retained a DN phenotype indicates that transformation of the DN thymocyte subset can occur, i.e., the induction of proliferation per se does not necessarily imply differentiation of DN thymocytes.

Almost 90% of the T cell lymphomas isolated from MoMuLV-infected Rag2-deficient mice had bypassed the block in T cell differentiation, as indicated by the expression of either CD4 and/or CD8. Given this fact, we reasoned that the analysis of common proviral insertions in a large panel of these tumors, and specifically in DP tumors, might allow us to identify genes with a function in early T cell development. Subsequently, this function can be tested by expressing these gene(s) in thymocytes of compound recombination-deficient mice.

The Pim1 Transgene Rescues Cytokine Signaling Deficiency.

150 lymphomas derived from MoMuLV-infected Rag2-deficient mice were characterized for the presence of CD4, CD8, CD24, CD25, CD44, CD45R, CD90, or NK1.1 surface markers and were classified according to the expression of CD4 and/or CD8 markers. The Pim1 locus was identified as a proviral integration site in T cell lymphomas at all developmental stages from MoMuLV-infected Rag-deficient mice. Two tumors with a provirus in the Pim1 locus had retained the DN marker profile. Interestingly, both tumors displayed a very similar marker profile specific for very early thymocytes 47: CD4−8−25lo44hi90lo and CD24− in the case of tumor 79, and CD24+ in the case of tumor 116. Possibly, PIM1 is placed in a signaling context able to amplify other growth factor receptor signals, which control proliferation of early DN pro-T cells 39. These data suggested that PIM1 can support growth of pro-T cells. As previous functional studies on PIM1 indicated a role in cytokine signaling and proliferation of B cell progenitors 24 and mast cells 25, we further investigated whether PIM1 fulfills a similar role in the T cell lineage. Indeed, elevated PIM1 levels can rescue to a significant extent the thymic proliferation defect of γc- and IL-7–mutant strains. This effect is specific for PIM, as a range of other oncogenes, such as Bcl2 and LckF, failed to do so.

PIM1 Enables Accumulation of DP Thymocytes in Rag-mutant but not in CD3γ-mutant Mice: Synergism between CD3 and PIM1 Signaling.

The high frequency of proviral insertions into the Pim1 locus of DP tumors suggested that PIM1 can also be involved in compensation of defective β-selection in Rag-deficient thymocytes. A subsequent independent gain of function analysis making use of Pim1-transgenic Rag-deficient mice directly confirmed this involvement. We observed further development of DN, differentiation-arrested, Rag-deficient thymocytes into small DP CD25− thymocytes in a time-dependent fashion. The DP thymocytes show a reduced cell size, arguing against the possibility that these cells are transformed by PIM1 or have become a target of a secondary transforming event. These and recently described data 27 indicate that PIM1 kinase can compensate for defective pre-TCR–CD3 signaling. A potential PIM1 target that might mediate this effect has been reported recently 48. PIM1 binds and phosphorylates the ubiquitously expressed transcriptional coactivator p100 and thereby stimulates the transcriptional activity of c-Myb in a p100-dependent manner 48. In this respect, it would be of interest to investigate whether Myb plays a role in thymic expansion.

To elaborate further on the role of PIM kinases in T cell signaling pathways, the same Eμ-Pim1 transgene was crossed into the CD3γ-mutant background. Similar to the situation in Rag-deficient mice, T cell development is arrested at the CD4−8−25+44− in CD3γ-mutant mice 32. Rag-deficient thymocytes express CD3∈-containing complexes at the cell surface that permit β-selection upon cross-linking with CD3∈-specific mAbs in fetal thymic organ cultures as well as in vivo 44 45 46. These data are in line with other observations indicating that the cytoplasmic domain of CD3∈ suffices in signaling β-selection 49. However, in PIM1-transgenic CD3γ-deficient mice, we did not observe any expansion of the DP compartment. Two models can explain the apparent requirement for CD3γ in PIM1-mediated T cell differentiation of Rag-deficient thymocytes.

First, PIM1 might directly function in the CD3γ pathway in addition to its role in cytokine signaling. Second, and in our view more likely, PIM1 might act in the cross-talk between cytokine and TCR signaling in which the effect of PIM1 depends on CD3 signaling. It is possible that in Rag-deficient mutant mice, occasional dimerization of CD3γ∈ modules provides a weak signal in DN pro-T cells. The frequency of dimerization might be too low and, consequently, this signal might normally fall below a critical threshold required to signal β-selection in DN thymocytes. However, in the presence of higher PIM1 levels, as is the case in Eμ-Pim1–transgenic Rag-deficient mice, the proliferating DN population would be larger and occasional dimerization could occur in sufficient frequency to permit β-selection in some of the cells in Pim1-transgenic Rag-deficient mice. The rare occurrence of this CD3 signal might explain the correlation between the numbers of DP thymocytes and the age of the Pim1-transgenic Rag-deficient animals. In this model, PIM functions as an integrator of cytokine and TCR signaling. The concept of integrated signaling pathways is also supported by data obtained from crosses between mice deficient for the γc and pre-T cell α genes 50 and between mice deficient for γc and c-kit genes 51. The phenotype of the compound mutant mice is far more severe than would be expected on the basis of the additive effects of the single knockouts. Future experiments will address the biochemical basis of this synergistic interaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge H.J. Fehling, T. Göbel, J. Jonkers, H. Mikkers, and R. Torres for critically reading the manuscript and the help of K. Hafen during MoMuLV infections.

This work was supported by grants from The Dutch Cancer Society and the Netherlands Organization for Pure Research (NWO) to P. Krimpenfort and The Leukemia Society of America to J. Allen. The Basel Institute for Immunology was founded and is supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland.

Footnotes

1used in this paper: DN, double negative; DP, double positive; ISP, immature single positive; MoMuLV, Moloney murine leukemia virus; RT, reverse transcriptase

H. Jacobs and P. Krimpenfort contributed equally to this work.

References

- Rodewald H.R., Fehling H.J. Molecular and cellular events in early thymocyte development. Adv. Immunol. 1998;69:1–112. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60606-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehling H.J., von Boehmer H. Early alpha beta T cell development in the thymus of normal and genetically manipulated mice. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1997;9:263–275. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard W.J., Shores E.W., Love P.E. Role of the cytokine receptor γ chain in cytokine signaling and lymphoid development. Immunol. Rev. 1995;148:97–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugamura K., Asao H., Kondo M., Tanaka N., Ishii N., Nakamura M., Takeshita T. The common gamma-chain for multiple cytokine receptors. Adv. Immunol. 1995;59:225–277. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60632-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Shores E.W., Hu-Li J., Anver M.R., Kelsall B.L., Russell S.M., Drago J., Noguchi M., Grinberg A., Bloom E.T. Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking expression of the common cytokine receptor gamma chain. Immunity. 1995;2:223–238. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiSanto J.P., Müller W., Guy Grand D., Fischer A., Rajewsky K. Lymphoid development in mice with a targeted deletion of the interleukin 2 receptor gamma chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:377–381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki K., Sunaga S., Komagata Y., Kodaira Y., Mabuchi A., Karasuyama H., Yokomuro K., Miyazaki J.I., Ikuta K. Interleukin 7 receptor-deficient mice lack γδ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:7172–7177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohbo K., Suda T., Hashiyama M., Mantani A., Ikebe M., Miyakawa K., Moriyama M., Nakamura M., Katsuki M., Takahashi K. Modulation of hematopoiesis in mice with a truncated mutant of the interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain. Blood. 1996;87:956–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschon J.J., Morrissey P.J., Grabstein K.H., Ramsdell F.J., Maraskovsky E., Gliniak B.C., Park L.S., Siegler S.F., Williams D.E., Ware C.B. Early lymphocyte expansion is severely impaired in interleukin 7 receptor–deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:1955–1960. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Freeden-Jeffry U., Vieira P., Lucian L.A., McNeil T., Burdach S.E., Murray R. Lymphopenia in interleukin (IL)-7 gene-deleted mice identifies IL-7 as a nonredundant cytokine. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1519–1526. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick C.A., Dudley E.C., Viney J.L., Owen M.J., Hayday A.C. Rearrangement and diversity of T cell receptor β chain genes in thymocytesa critical role for the β chain in development. Cell. 1993;73:513–519. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90138-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Boehmer H. Developmental biology of T cells in T cell receptor transgenic mice. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1990;8:531–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.002531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P., Iacomini J., Johnson R.S., Herrup K., Tonegawa S., Papaioannou V.E. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai Y., Rathbum G., Lam K.P., Oltz E.M., Stewart V., Mendelsohn M., Charron J., Datta M., Young F., Stall A.M. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina T.J., Kishihara K., Siderovski D.P., van Ewijk W., Narendran A., Timms E., Wakeham A., Paige C.J., Hartmann K.U., Veillette A. Profound block in thymocyte development in mice lacking p56lck. Nature. 1992;357:161–164. doi: 10.1038/357161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin S.D., Anderson S.J., Forbush K.A., Perlmutter R.M. A dominant-negative transgene defines a role for p56lck in thymopoiesis. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1993;12:1671–1680. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05812.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P., Anderson S.J., Perlmutter R.M., Mak T.W., Tonegawa S. An activated lck transgene promotes thymocyte development in RAG-1 mutant mice. Immunity. 1994;1:261–267. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berns A., Breuer M., Verbeek S., van Lohuizen M. Transgenic mice as a means to study synergism between oncogenes. Int. J. Cancer Suppl. 1989;4:22–25. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910440706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers J., Berns A. Retroviral insertional mutagenesis as a strategy to identify cancer genes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1996;1287:29–57. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(95)00020-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Lugt N.M.T., Domen J., Verhoeven E., Linders K., van der Gulden H., Allen J., Berns A. Proviral tagging in Eμ-myc transgenic mice lacking the Pim-1 proto-oncogene leads to compensatory activation of Pim-2. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1995;14:2536–2544. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman J.D., Vician D., Crispino M., Tocco G., Marcheselli V.L., Bazan N.G., Baudry M., Herschmann H.R. KID-1, a protein kinase induced by depolarization in brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16535–16543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J.D., Verhoeven E., Domen J., van der Valk M., Berns A. Pim-2 transgene induces lymphoid tumors, exhibiting potent synergy with c-myc. Oncogene. 1997;15:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek S., van Lohuizen M., van der Valk M., Domen J., Kraal G., Berns A. Mice bearing the Eμ-myc and Eμ-pim-1 transgenes develop pre-B-cell leukemia prenatally. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:1176–1179. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domen J., van der Lugt N.M., Acton D., Laird P.W., Linders K., Berns A. Pim-1 levels determine the size of early B lymphoid compartments in bone marrow. J. Exp. Med. 1993;178:1665–1673. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domen J., van der Lugt N.M., Laird P.W., Saris C.J., Clarke A.R., Hooper M.L., Berns A. Impaired interleukin-3 response in Pim-1-deficient bone marrow-derived mast cells. Blood. 1993;82:1445–1452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domen J., van der Lugt N.M., Laird P.W., Saris C.J., Berns A. Analysis of Pim-1 function in mutant mice. Leukemia. 1993;7:108–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T., Karsunky H., Rödel B., Zevnik B., Elsässer H.-P., Möröy T. Evidence implicating Gfi-1 and Pim-1 in pre-T-cell differentiation steps associated with β-selection. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1998;17:5349–5369. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten G., Cuypers H.T., Berns A. Proviral activation of the putative oncogene Pim-1 in MuLV induced T-cell lymphomas. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1985;4:1793–1798. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten G., Cuypers H.T., Boelens W., Robanus-Maandag E., Verbeek J., Domen J., van Beveren C., Berns A. The primary structure of the putative oncogene pim-1 shows extensive homology with protein kinases. Cell. 1986;46:603–611. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90886-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper M.L. Embryonal stem cells. In: Evans H.J., editor. Modern Genetics. Hatwood Academics Publishers GmbH; Switzerland: 1992. p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Robanus-Maandag E.C., van der Valk M., Vlaar M., Feltkamp C., O'Brien J., van Roon M., van der Lugt N.M., Berns A., Riele H. Developmental rescue of an embryonic-lethal mutation in the retinoblastoma gene in chimeric mice. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1994;13:4260–4268. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haks M.C., Krimpenfort P., Borst J., Kruisbeek A.M. The CD3γ chain is essential for development of both the TCRαβ and TCRγδ lineages. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1998;17:1871–1882. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lohuizen M., Verbeek S., Krimpenfort P., Domen J., Saris C., Radaszkiewicz T., Berns A. Predisposition to lymphomagenesis in pim-1 transgenic micecooperation in murine leukemia virus-induced tumors. Cell. 1989;56:673–682. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell T.J., Deane N., Platt F.M., Nunez G., Jaeger U., McKearn J.P., Korsmeyer S.J. Bcl-2-immunoglobulin transgenic mice demonstrate extended B cell survival and follicular lymphoproliferation. Cell. 1989;57:79–88. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten G., Cuypers H.T., Zijlstra M., Melief C., Berns A. Involvement of c-myc in MuLV-induced T cell lymphomas in micefrequency and mechanisms of activation. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1984;3:3215–3222. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheijen B., Jonkers J., Acton D., Berns A. Characterization of pal-1, a common proviral insertion site in murine leukemia virus induced lymphomas of c-myc and pim-1 transgenic mice. J. Virol. 1997;7:9–16. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.9-16.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs H., Iacomini J., van de Ven M., Tonegawa S., Berns A. Domains of the TCR beta-chain required for early thymocyte development. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:1833–1843. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs H. Control of T Cell Development in TCR Mutant Mice. Thesis in Medical Science 1996. University of Amsterdam; The Netherlands: pp. 196 [Google Scholar]

- Malissen B., Malissen M. Functions of TCR and pre-TCR subunitslessons from gene ablation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1996;8:383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohwer F., Todd S., McGuire K.L. The effect of IL-2 treatment on transcriptional attenuation in proto-oncogenes pim-1 and c-myb in human thymic blasts. J. Immunol. 1996;157:643–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muli A.L., Wakao H., Kinoshita T., Kitamura T., Miyajima A. Suppression of interleukin-3 induced gene expression by a C-terminal truncated Stat5role of Stat5 in proliferation. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1996;15:2425–2433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Santo J.P., Rodewald H.-R. In vivo roles of receptor tyrosine kinases and cytokine receptors in early thymocyte development. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1998;10:196–207. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M., Akashi K., Domen J., Sugamura K., Weissman I.L. Bcl-2 rescues T lymphopoiesis, but not B or NK cell development, in common gamma chain deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;7:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs H., Vandeputte D., Tolkamp L., de Vries E., Borst J., Berns A. CD3 components at the surface of pro-T cells can mediate pre-T cell development in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:934–939. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levelt C.N., Mombaerts P., Iglesias A., Tonegawa S., Eichmann K. Restoration of early thymocyte differentiation in T-cell receptor beta-chain-deficient mutant mice by transmembrane signaling through CD3 epsilon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:11401–11405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai Y., Alt F.W. CD3 epsilon-mediated signals rescue the development of CD4+CD8+ thymocytes in RAG-2− /− mice in the absence of TCR beta chain expression. Int. Immunol. 1994;6:995–1001. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.7.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortman K., Wu L. Early T lymphocyte progenitors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1996;14:29–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverson J.D., Koskinen P.J., Orrico F.C., Rainio E.-M., Jalkanen K.J., Dash A.B., Eisenman R.N., Ness S.A. Pim-1 kinase and p100 cooperate to enhance c-Myb activity. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:417–425. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai Y., Ma A., Cheng H.L., Alt F.W. CD3 epsilon and CD3 zeta cytoplasmic domains can independently generate signals for T cell development and function. Immunity. 1995;2:401–411. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Santo J.P., Aifantis I., Rosmaraki E., Garcia C., Feinberg J., Fehling H.J., Fischer A., von Boehmer H., Rocha B. The common cytokine receptor γ chain and the pre-T cell receptor provide independent but critically overlapping signals in early α/β T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:563–574. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.3.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodewald H.R., Ogawa M., Haller C., Waskow C., DiSanto J.P. Pro-thymocyte expansion by c-kit and the common cytokine receptor gamma chain is essential for repertoire formation. Immunity. 1997;6:265–272. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80329-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]