Abstract

Brucella abortus S19 is the vaccine most frequently used against bovine brucellosis. Although it induces good protection levels, it cannot be administered to pregnant cattle, revaccination is not advised due to interference in the discrimination between infected and vaccinated animals during immune-screening procedures, and the vaccine is virulent for humans. Due to these reasons, there is a continuous search for new bovine vaccine candidates that may confer protection levels comparable to those conferred by S19 but without its disadvantages. A previous study characterized the phenotype associated with the phosphoglucomutase (pgm) gene disruption in Brucella abortus S2308, as well as the possible role for the smooth lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in virulence and intracellular multiplication in HeLa cells (J. E. Ugalde, C. Czibener, M. F. Feldman, and R. A. Ugalde, Infect. Immun. 68:5716-5723, 2000). In this report, we analyze the protection, proliferative response, and cytokine production induced in BALB/c mice by a Δpgm deletion strain. We show that this strain synthesizes O antigen with a size of approximately 45 kDa but is rough. This is due to the fact that the Δpgm strain is unable to assemble the O side chain in the complete LPS. Vaccination with the Δpgm strain induced protection levels comparable to those induced by S19 and generated a proliferative splenocyte response and a cytokine profile typical of a Th1 response. On the other hand, we were unable to detect a specific anti-O-antigen antibody response by using the fluorescence polarization assay. In view of these results, the possibility that the Δpgm mutant could be used as a vaccination strain is discussed.

Brucella spp. are gram-negative, facultative intracellular bacteria that cause a chronic zoonotic disease worldwide known as brucellosis. Brucella abortus, the etiological agent of bovine brucellosis, causes abortion and infertility in cattle and undulant fever in humans (4). The human disease is also caused by Brucella melitensis, Brucella suis, and Brucella canis.

Brucella spp. are intracellular pathogens that invade and proliferate within host cells; virulence is associated with the ability to multiply inside professional and nonprofessional phagocytic cells. Due to the intracellular localization, control of the infection requires a cell-mediated immune response, in which the Th1 arm is relevant for protection (8).

As in many other gram-negative bacteria, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is an important component of the outer membrane. LPS has three domains: the lipid A, the core oligosaccharide, and the O antigen or O side chain. The complete structure of Brucella LPS has not been elucidated yet, but it was reported that lipid A is composed of glucosamine, n-tetradecanoic acid, n-hexadecanoic acid, 3-hydroxytetradecanoic acid, and 3-hydroxyhexa-decanoic acid (3). The O side chain is a linear homopolymer of α-1,2-linked 4,6-dideoxy-4-formamido-α-d-mannopyranosyl (perosamine) subunits usually with a degree of polymerization averaging between 96 and 100 subunits (3). The complete structure of B. abortus core LPS has not been determined yet. Previous reports have shown that it is formed by 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid (KDO), glucosamine, and glucose, although the exact amounts of these sugars have not been determined (10).

The precise role of the LPS in the biology of Brucella is still an unsolved issue. In the past few years, a considerable number of reports have appeared assigning different roles to the LPS; for example, it has been suggested that the LPS is a key molecule for invasion and intracellular multiplication (15) and that it acts as an antiapoptotic effector (6).

B. abortus S19 is the most commonly used attenuated live vaccine for the prevention of bovine brucellosis. The vaccine induces good levels of protection in cattle, preventing premature abortion (11). Although B. abortus S19 is the vaccine most widely used in eradication campaigns worldwide, it has two major problems. (i) It produces abortion when administered to pregnant cattle and is fully virulent for humans (22), and (ii) the presence of smooth LPS interferes with the discrimination between infected and vaccinated animals during immune-screening procedures (23). In order to avoid these problems, several strategies for the development of alternative vaccines have been described. One of them is the isolation of avirulent or attenuated strains lacking the O antigen (rough strains). These strains are unable to induce antibodies that interfere with the diagnosis. One of the most studied rough vaccine strains is B. abortus RB51, a spontaneous mutant isolated by screening for the rough phenotype after a series of passages in selective media (19). B. abortus RB51 is avirulent in mice and cattle, retains the capacity to induce protection and cellular immunity, and does not interfere with diagnosis (20). Although RB51 is currently being used in the United States, efforts to improve the vaccine have been made. A recent study reported that wboA, involved in the polymerization of the O antigen, is one of the mutated loci in strain RB51. The authors demonstrated that this gene is not responsible for the rough phenotype (since RB51 complemented with wboA remains rough); however, they showed that the recombinant RB51 wboA strain contains detectable O antigen localized in the cytoplasm (25). Protection studies with mice showed that the RB51 wboA strain has a better protection efficiency than the parental RB51 strain. In accordance with these results, the authors speculate that this improvement may be due to the cytoplasmic presence of O antigen (25).

In our laboratory, we have previously cloned, sequenced, and disrupted the gene coding for the enzyme phosphoglucomutase (pgm), which is responsible for the interconversion of glucose-6-phosphate to glucose-1-phosphate. The mutant does not synthesize the sugar-nucleotide UDP-glucose and thus is unable to form any polysaccharide containing glucose, galactose, or any other sugars whose synthesis proceeds through a glucose-nucleotide intermediate (24). The mutant has a rough phenotype and is avirulent in mice but retains the ability to multiply inside HeLa cells, although it shows a delay of exponential intracellular replication (24). These characteristics prompted us to evaluate the potential use of this strain as a live rough-phenotype vaccine.

In this report, we describe the construction of a B. abortus S2308 Δpgm deletion strain and evaluate the humoral and cellular immune responses in mice as well as the induction of protection against challenge with the virulent strain B. abortus S2308.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth or Terrific broth (17). Brucella strains were grown at 37°C in tryptic soy broth. If necessary, media were supplemented with the appropriated antibiotics: ampicillin at 100 μg/ml for E. coli and 50 μg/ml for B. abortus and gentamicin at 20 μg/ml for E. coli and 2.5 μg/ml for B. abortus.

Construction of the pgm deletion mutant.

In order to obtain a clean deletion of the pgm gene, plasmid pUB22 (24), which has a 4.3-kb fragment containing the pgm gene, was digested with EcoRV and ligated to a dicistronic cassette, sacB-accI, digested with the same enzyme. The resulting plasmid, named pUB22SG, has the pgm gene interrupted by the cassette. This plasmid was electroporated into B. abortus S2308; gentamicin-resistant, ampicillin-sensitive, and sucrose-sensitive colonies were selected; and double recombination events were confirmed by PCR. The resulting strain was designated B2212. On the other hand, plasmid pKB43 was constructed by cloning the 4.3-kb fragment into vector pK18mob (18). pKB43 was digested with HindIII, which digests two times in the coding region, and religated in order to obtain plasmid pΚP201, which has a deleted copy of the pgm gene. This plasmid was conjugated into strain B2212, and sucrose-resistant and gentamicin- and ampicillin-sensitive colonies were selected. Double recombination events were confirmed by PCR using appropriate oligonucleotides which amplify fragments of 1,414 bp in the wild-type strain and 320 bp in the deletion strain. Mutant Δpgm was selected for further studies. The insertion of the gentamicin resistance cassette into the wild-type strain was performed in order to generate an intermediate strain that was used to obtain a clean deletion of pgm. Afterward, the intermediate gentamicin-resistant strain B2212 was destroyed.

LPS analysis.

LPS was isolated by the hot-phenol-water extraction procedure as described previously (24). To detect the presence of O polysaccharide in LPS, whole-cell extract and extracted LPS from the Δpgm mutant or the virulent parental strain S2308 were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as previously described (24) and analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-O-polysaccharide monoclonal antibody M84 (13) (kindly provided by K. Nielsen) and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (DAKO Corp., Carpinteria, Calif.) developed with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Serological test.

To detect the presence of specific anti-O antibodies in sera of inoculated mice, a homogeneous fluorescence polarization assay (FPA) using purified B. abortus O polysaccharide conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (9) was used as previously described (12). Sera from mice inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 5× 105 CFU of strain Δpgm or S2308 (six mice per group) or with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (three mice) were collected by retro-orbital punction at 3, 5, 7, and 9 weeks postinoculation (p.i.). Sera were diluted 1:50 with 2 ml of 0.01 M PBS, pH 7.2, with 0.5% lithium lauryl sulfate. The fluorescence polarization of the tracer was determined (with the blank subtracted) in duplicate in a fluorescence polarization analyzer (FPM-1; Jolley Consulting and Research, Round Lake, Ill.). Titers of antibody are expressed as millipolarization units (mP). A buffered antigen plate agglutination test (BPAT) was performed as described in reference 1 by using acidified stained antigen (ISG, Buenos Aires, Argentina).

Survival of Δpgm strain in mice.

Survival of the Δpgm strain was determined by quantitating the numbers of CFU of the strains in the spleens at different intervals of time. Groups of five 9-week-old female BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with 107 CFU of strain Δpgm or S2308 in 0.1 ml of 150 mM NaCl. At 1, 3, 5, and 8 weeks p.i., animals were sacrificed; spleens were removed and homogenized in 150 mM NaCl. Tissue homogenates were serially diluted with PBS and plated onto tryptic soy broth-agar with the appropriate antibiotics to determine the number of CFU per spleen.

Protection experiments.

Protection experiments were carried out as described previously (2). Groups of 10 mice were vaccinated i.p. with 107 CFU of strain Δpgm, 5× 105 CFU of B. abortus S19, or PBS (unvaccinated control). The exact dose was determined retrospectively. Eight weeks postvaccination, both groups were challenged i.p. with 5× 105 CFU of virulent B. abortus S2308 per mouse. Two and 4 weeks postchallenge, five mice per group were sacrificed and the numbers of CFU recovered from spleens were determined.

Splenocyte proliferation assay and cytokine induction.

Eight weeks p.i., spleens from mice inoculated with strain Δpgm or PBS were obtained under aseptic conditions. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the spleens by disgregation in cell culture medium (RPMI 1640-10% fetal bovine serum; GIBCO-BRL), and erythrocytes were lysed with Tris-buffered ammonium chloride solution (Sigma). Splenocytes at 5 × 105 cells per well were cultured in 96-well flat-bottom plates in the presence of S2308 heat-inactivated whole cells in an amount equivalent to 106 CFU, concanavalin A (ConA; 2 μg/ml in PBS), or PBS (nonstimulated control). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2 for 3 days and pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (New England Nuclear) per well for 16 h. Cells were harvested onto glass filter strips (Nunc), and radioactivity incorporation was measured by liquid scintillation spectroscopy in a 1414 Winspectral Beta counter (Wallac Oy, Turku, Finland). The mean number of counts per minute and the standard error of the mean for each quadruplicate set of cells were determined. Levels of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and interleukin-4 (IL-4) were determined in murine splenocyte culture supernatants after 72 h of incubation with heat-killed S2308 cells or mitogen as follows. IFN-γ was assayed in triplicate by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using microplates (Maxisorp; Nunc) coated with purified rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone R4-6A2; Pharmingen). Biotinylated rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2; Pharmingen) and recombinant mouse IFN-γ (Pharmingen) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. IL-4 was assayed in triplicate by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using microplates coated with purified rat anti-mouse IL-4 (clone 11B11; Pharmingen). Biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-4 (clone BVD6-24G2; Pharmingen) and recombinant mouse IL-4 (Pharmingen) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Captured biotinylated monoclonal antibodies were evaluated by the addition of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Pharmingen) followed by 2,2′-azino-bis(-ethylbenzthiazoline)-6-sulfonic acid (Roche Diagnostics). Plates were read at 405 nm in a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The concentrations of cytokines were calculated using a linear-regression equation obtained from the absorbance values of standards.

RESULTS

Construction of a Δpgm strain.

A problem in developing new live vaccines with mutant strains obtained by genetic engineering is the introduction of antibiotic resistant markers. Usually the strategy to develop deletion strains lacking antibiotic resistance involves the generation of an insertional mutation in the desired gene and subsequent replacement with a deletion copy. The success of this strategy requires testing of a high number of colonies due to the low frequency of double recombination events, making the technique very laborious. In order to reduce the number of colonies to be tested, we constructed a dicistronic cassette with a promoterless sacB gene from Bacillus subtilis (16) and the accI gene coding for resistance to gentamicin (see Materials and Methods). The cassette was introduced into a unique EcoRV site of the pgm gene cloned into pUC19, creating plasmid pUB22SG. Strain B2212 was generated by introducing plasmid pUB22SG into B. abortus S2308 and screening for gentamicin resistance and lack of growth in 10% sucrose. Plasmid pKP201, which had a deleted pgm gene in a mobilized suicide vector (see Materials and Methods), was conjugated into strain B2212, and exoconjugants were selected in a medium containing 10% sucrose and nalidixic acid at 5 μg/ml. Selected colonies were tested for sensitivity to gentamicin, and the frequency of genetic replacement as confirmed by PCR was 6.6 × 10−3 (4 out of 600 screened colonies were found to be sensitive, indicating that genetic replacement had occurred). The genetic replacement events were confirmed by PCR as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting strain, named Δpgm, had behavior in HeLa cells identical to that described for strain B2211 (24) (data not shown). Strain Δpgm was used for further studies.

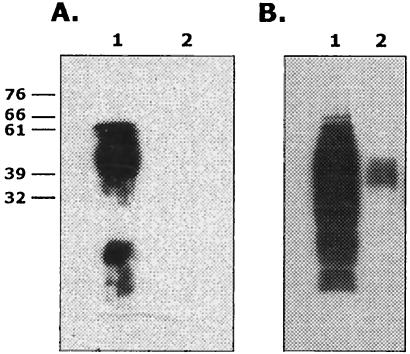

The rough strain Δpgm is able to synthesize O antigen.

As previously described (24), B. abortus S2308 lacking pgm activity is rough due to the incapacity to synthesize a complete LPS. In order to analyze the presence of O antigen, whole-cell extracts and extracted LPS were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blots were developed with an anti-O monoclonal antibody. As shown in Fig. 1, extracted LPS from Δpgm cells did not show any detectable signal, thus indicating that it is devoid of O antigen. However, Δpgm whole-cell extracts contained detectable amounts of O antigen that migrated as a 45-kDa molecule. It can be observed that both LPS fractions and whole-cell extracts from B. abortus S2308 wild type yielded the pattern characteristic of O antigen presence. These results indicate that Δpgm is able to synthesize O antigen but is incapable of assembling a complete LPS, probably due to the presence of an altered core structure. It is interesting that the size of the O antigen synthesized by the mutant is similar to that reported to be present in whole-cell extracts of the RB51 wboA strain (25). It was also reported that a 45-kDa O-antigen fragment interacting with major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecules can be recovered from B lymphocytes exposed to B. abortus LPS (7).

FIG. 1.

Western blot analysis of extracted LPS (A) and crude extracts (B) with nonoclonal anti-O-antigen antibodies. Lanes 1, wild type; lanes 2, Δpgm. Molecular mass markers in kilodaltons are shown on the left of panel A. SDS-PAGE and Western blot were carried out as described in Materials and Methods.

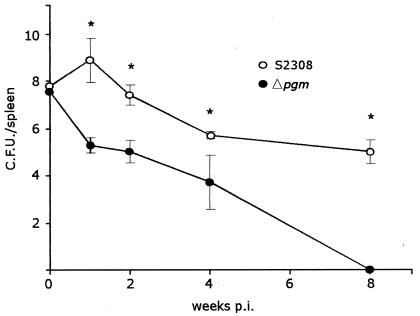

Strain Δpgm is avirulent in mice.

In order to analyze the virulence of strain Δpgm, high doses (107 CFU) of B. abortus S2308 and Δpgm strains were inoculated i.p. into mice. At 1, 3, 5, and 8 weeks p.i., groups of five mice were sacrificed, spleens were removed, and the number of viable Brucella organisms was examined. Two mice inoculated with wild-type virulent S2308 died within the first week. As shown in Fig. 2, the numbers of viable bacteria recovered from spleens of mice inoculated with Δpgm were, at all times tested, significantly lower than those from mice inoculated with strain S2308, and strain Δpgm was completely cleared at 8 weeks p.i., thus indicating a severe virulence reduction. These results indicate that even at high doses (vaccine dose) strain Δpgm is cleared from the animal in a short period of time.

FIG. 2.

Virulence in mice. Mice were infected i.p. with 107 CFU of the wild-type or Δpgm strain, and numbers of CFU recovered from spleens at different times postinfection were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Bars represent the means ± standard deviations (SD). *, P < 0.001.

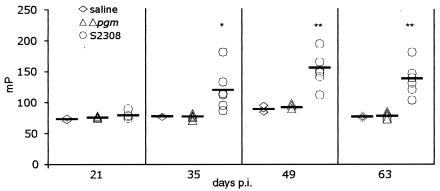

Antibody response against O antigen.

The presence in the mutant whole-cell extracts of O-antigen molecules not assembled into the LPS prompted us to study the antibody response against O antigen in mice inoculated with 5× 105 CFU of the Δpgm or B. abortus S2308 strain. The presence of specific anti-O antibodies was detected by the FPA as described previously (12). Figure 3 shows that mice receiving B. abortus S2308 raised antibodies against the O antigen that reached their maximal titer (152.71 ± 27.65 mP) at 49 days p.i. In contrast to B. abortus S2308-inoculated mice, Δpgm-vaccinated mice failed, as the saline-vaccinated control mice, to elicit antibodies against O antigen at any time tested (these groups had antibody titers of 92.33 ± 3.66 and 92.2 ± 7.10 mP at 49 p.i., respectively). These results indicate that the O antigen present in strain Δpgm is incapable of eliciting a detectable specific antibody response. Moreover, sera from Δpgm-inoculated animals subjected to a BPAT failed to agglutinate at a 1:25 dilution. In contrast, fast and strong agglutination was observed with sera from the infected animals with 1:25 and 1:250 dilutions. In a Western blot analysis with a purified LPS fraction from S2308, no reactivity with the Δpgm sera was observed, while a 1:500 dilution of the S2308 sera gave strong reactivity (data not shown). Due to the fact the Δpgm strain harbors small amounts of a truncated O antigen form as revealed in Fig. 1, the nature of this lack of response remains to be established.

FIG. 3.

Elicitation of anti-O-antigen antibodies. Groups of six mice were inoculated with 5 × 105 CFU, and sera were collected at different times postinfection. Titers of specific anti-O-antigen antibodies were determined by FPA as described in Materials and Methods. Horizontal bars represent the average values for the group. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001 compared with control S2308-inoculated mice.

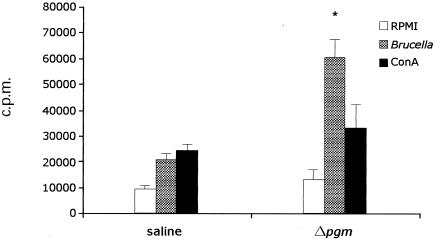

Proliferative splenocyte response in mice vaccinated with Δpgm.

To investigate the cellular immune response induced by the Δpgm strain, we analyzed the proliferative splenocyte responses of vaccinated and nonvaccinated mice upon stimulation with heat-inactivated B. abortus S2308 whole cells. As shown in Fig. 4, at 8 weeks p.i., splenocytes recovered from mice vaccinated with Δpgm proliferated in a specific manner upon stimulation, in contrast to those from the nonvaccinated control group (60,142 ± 7,443 versus 20,855 ± 2,541 cpm; P < 0.001). All immunized animals responded to the nonspecific mitogen ConA (positive control). These results indicate that vaccination with Δpgm is able to induce a cellular proliferative response.

FIG. 4.

Lymphocyte proliferation assay. Mice were inoculated with 107 CFU of the Δpgm mutant or with PBS. Eight weeks after inoculation, spleen lymphocytes were recovered and stimulated with heat-inactivated B. abortus S2308, RPMI 1640, or ConA, and proliferation assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Bars represent the means ± SD of results for quadruplicate sets of cells. *, P < 0.001.

IFN-γ and IL-4 cytokine induction.

The cytokine profile from splenocyte culture supernatants of immunized mice was analyzed upon stimulation with 107 CFU of heat-inactivated B. abortus S2308 whole cells. Eight weeks after immunization, splenocytes were obtained and the levels of IFN-γ and IL-4 in culture supernatants were determined in triplicate. As a positive control, the nonspecific mitogen ConA was used. Spleen cells from Δpgm-vaccinated animals were induced to secrete high levels of IFN-γ (112.0 ng/ml) after stimulation. A significant induction was also observed upon stimulation with ConA (53.8 ng/ml). In contrast, the splenocytes from PBS-inoculated control animals released IFN-γ (36.43 ng/ml) upon stimulation with ConA. The level of IFN-γ in supernatants of splenocytes from these animals was 16.6 ng/ml upon stimulation with heat-inactivated S2308. Levels of IFN-γ were below the detection limit of the assay (30 pg/ml) for both groups of supernatants upon stimulation with RPMI 1640, and IL-4 was not detected in the supernatants of splenocytes obtained from immunized or nonimmunized animals (data not shown). These results indicate that immunization with strain Δpgm elicits a classical Th1 response.

Strain Δpgm induces immune protection against challenge with virulent B. abortus S2308.

In order to examine the protection induced by Δpgm, a vaccine challenge experiment was performed. Mice were vaccinated i.p. with 107 CFU of Δpgm, with PBS, or with 105 CFU of B. abortus S19. Eight weeks postvaccination, animals were challenged with 5× 105 CFU of strain B. abortus S2308. Protection was defined as the difference between the numbers of viable bacteria recovered from spleens of immunized mice and those recovered from spleens of mice receiving saline; results are summarized in Table 1. Vaccine efficacy was expressed as log10 units of protection. Δpgm generated significant protection 2 and 4 weeks postchallenge, with 2.25 and 1.93 protection units, respectively. As expected, B. abortus strain S19 also induced significant protection at 4 weeks (1.78 protection units). These results, together with the inability of the mutant to elicit specific O-antigen antibodies, emphasize the potential of this mutant for use as a live vaccine for cattle.

TABLE 1.

Protection against B. abortus S2308

| Treatment group (n = 5) receiving: | Mean log10 of the no. of brucellae ± SD in spleens on postchallenge day:

|

Log10 of protectiona on day:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 28 | 14 | 28 | |

| Saline | 5.35 ± 0.14 | 4.73 ± 0.41 | ||

| Δpgm | 3.10 ± 0.37 | 2.80 ± 0.87 | 2.25b | 1.93b |

| S19 | NDc | 2.95 ± 0.48 | ND | 1.78b |

Log10 of protection is defined as the difference between the mean log of the numbers of CFU from immunized mice and that of the numbers of CFU from mice receiving saline.

P < 0.05 (significant) compared with value for control mice.

ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

A variety of strategies are being used for developing new Brucella vaccines, with most of these strategies aiming at obtaining either attenuated strains, cell extracts, or recombinant proteins. B. abortus recombinant proteins expressed in either bacterial or eukaryotic vectors (DNA vaccines) showed, until now, limited success in inducing protection compared to B. abortus S19 or B. abortus RB51 live vaccines. One of the drawbacks for the rational development of new Brucella vaccines is the limited knowledge of virulence factors and pathogenesis. The recent deciphering of the complete genome sequences of B. melitensis and B. suis will help to identify genes involved in virulence and to obtain recombinant proteins or avirulent mutant candidates to be used as vaccines (5, 14).

It is well established that for intracellular pathogens, like brucellae, cellular immunity plays a central role in protection (8). Thus, searching for attenuated strains capable of inducing cellular immunity and protection is a valid strategy. The ideal live Brucella vaccine must fulfill a number of conditions: it must (i) be nonvirulent for the host, (ii) induce protection but not antibody response against LPS in order to avoid interference with serological diagnosis, and (iii) be genetically defined, preferably a deletion mutant with no antibiotic resistance and stability under field conditions. Several attempts to find the ideal live attenuated vaccine strain have been carried out; however, until now none of the candidates fulfill all these conditions. The B. abortus S19 strain is the live vaccine most used to prevent bovine brucellosis; it induces good protection, but it must be administered to calves younger than 4 months in order to prevent the persistence of serum antibodies that may interfere with the detection of the disease (11). The vaccine cannot be administered to pregnant cows since it may induce abortion, and no revaccination is recommended, mainly due to the induction of persistent anti-LPS antibodies.

In this work, we describe the construction of a B. abortus phosphoglucomutase deletion mutant and its protection properties in mice. The absence of phosphoglucomutase impairs the biosynthesis of glucose-1-phosphate, which prevents the generation of the activated sugar-nucleotide needed in all biosynthetic reactions requiring glucose (mainly synthesis of polysaccharides, glycoproteins, and glycolipids). In consequence, Δpgm has a rough phenotype but is able to synthesize the O antigen (a polymer of N-formylperosamine), as is shown in Fig. 1. Although Δpgm has a detectable level of O antigen, it is not capable of inducing detectable specific antibodies as determined by the FPA. On the other hand, the cell-mediated immune response induced by this strain was characterized by analyzing the splenocyte proliferative response and the cytokines produced after immunization. The specific splenocyte proliferation upon stimulation with heat-inactivated brucellae, the high-level induction of IFN-γ, and the absence of IL-4 secretion strongly suggest that this strain induces a strong cellular Th1 response reported to be essential for controlling intracellular pathogens (21). We finally analyzed the virulence at high doses and the protection properties of Δpgm in the BALB/c mouse model. The data show that this strain induces protection levels equivalent to those induced by S19 (approximately 2 log units) but has a severe reduction in virulence as estimated by the number of viable bacteria in the spleens at all tested times p.i.

B. abortus rough mutants have been used as live vaccines. The spontaneously rough mutant strain 45/20 isolated in 1922 has the disadvantage of reverting to a smooth virulent phenotype, and thus the strain is no longer used as a live vaccine. Another spontaneously rough mutant, strain RB51, was isolated as a rifampin-resistant mutant of B. abortus S2308. The strain was used as a live vaccine in the United States, Chile, and Mexico. Recently, the disruption of the putative glycosyl-transferase wboA gene in RB51 was described; however, complementation with wboA did not cause reversion to the smooth phenotype, thus indicating that another mutation(s) may account for the lack of smooth LPS and/or attenuation. Interestingly, the complemented strain RB51 wboA accumulated cytoplasmic O antigen of 45 kDa and in mice it induced the production of anti-O-antigen immunoglobulin G antibodies as well as higher levels of IFN-γ than the parental RB51 strain (25). As we show in this work, Δpgm has a rough LPS and a 45-kDa O-antigen reactive molecule was detected with a specific O-antigen monoclonal antibody in whole-cell extracts, which is reminiscent of what was observed with RB51 wboA. However, the sera from mice inoculated with Δpgm failed to react against the O antigen as determined by FPA, BPAT, and Western blot analysis. It is interesting that protection in mice was improved when animals were vaccinated with strain RB51 wboA. In this regard, Δpgm is similar to the RB51 wboA strain.

It was reported that B. abortus smooth LPS and its O antigen form stable complexes with mouse MHC-II molecules, raising the possibility that B. abortus LPS may play a role in T-cell activation. It was also demonstrated that only B. abortus LPS O antigen of a specific size of 45 kDa forms stable complexes with MHC-II (7). Considering these observations, it will be important to analyze the relationship between the presence of a 45-kDa O antigen and the level of protection conferred.

Preliminary results showed that once Δpgm was inoculated into previously B. abortus S19-vaccinated calves, it failed to induce antibody responses against smooth LPS, as detected by routine agglutination assays, thus suggesting that O antigen from Δpgm failed to elicit a humoral memory response in cattle. These characteristics suggest that Δpgm may be a useful vaccine strain to improve the livestock immunological status by revaccination under specially designed eradication campaigns in countries with large cattle populations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants PICT99 no. 01-06565 and PICT2000 no. 01-09194 from the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica, SECyT, Buenos Aires, Argentina. J.E.U. is a fellow of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina. D.J.C. is a researcher from the National Atomic Comission. R.A.U. is a member of the research carrier of the CONICET.

We acknowledge Fabio Fraga, University of General San Martín, for technical assistance and Patricia Silvapaulo for providing FPA reagents.

J.E.U. and D.J.C. contributed equally to this work.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angus, R. D., and C. E. Barton. 1984. The production and evaluation of a buffered plate antigen for use in a presumptive test for brucellosis. Dev. Biol. Stand. 56:349-356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briones, G., N. Inon de Iannino, M. Roset, A. Vigliocco, P. S. Paulo, and R. A. Ugalde. 2001. Brucella abortus cyclic beta-1,2-glucan mutants have reduced virulence in mice and are defective in intracellular replication in HeLa cells. Infect. Immun. 69:4528-4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caroff, M., D. R. Bundle, M. B. Perry, J. W. Cherwonogrodzky, and J. R. Duncan. 1984. Antigenic S-type lipopolysaccharide of Brucella abortus 1119-3. Infect. Immun. 46:384-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corbel, M. J. 1997. Brucellosis: an overview. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:213-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DelVecchio, V. G., V. Kapatral, R. J. Redkar, G. Patra, C. Mujer, T. Los, N. Ivanova, I. Anderson, A. Bhattacharyya, A. Lykidis, G. Reznik, L. Jablonski, N. Larsen, M. D'Souza, A. Bernal, M. Mazur, E. Goltsman, E. Selkov, P. H. Elzer, S. Hagius, D. O'Callaghan, J. J. Letesson, R. Haselkorn, N. Kyrpides, and R. Overbeek. 2002. The genome sequence of the facultative intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:443-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez-Prada, C. M., E. B. Zelazowska, M. Nikolich, T. L. Hadfield, R. M. Roop II, G. L. Robertson, and D. L. Hoover. 2003. Interactions between Brucella melitensis and human phagocytes: bacterial surface O-polysaccharide inhibits phagocytosis, bacterial killing, and subsequent host cell apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 71:2110-2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forestier, C., E. Moreno, J. Pizarro-Cerda, and J. P. Gorvel. 1999. Lysosomal accumulation and recycling of lipopolysaccharide to the cell surface of murine macrophages, an in vitro and in vivo study. J. Immunol. 162:6784-6791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang, X., and C. L. Baldwin. 1993. Effects of cytokines on intracellular growth of Brucella abortus. Infect. Immun. 61:124-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin, M., and K. Nielsen. 1997. Binding of the Brucella abortus lipopolysaccharide O-chain fragment to a monoclonal antibody. Quantitative analysis by fluorescence quenching and polarization. J. Biol. Chem. 272:2821-2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreno, E., S. L. Speth, L. M. Jones, and D. T. Berman. 1981. Immunochemical characterization of Brucella lipopolysaccharides and polysaccharides. Infect. Immun. 31:214-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicoletti, P. 1990. Vaccination, p. 283-300. In K. A. D. Nielsen and J. R. Duncan (ed.), Animal brucellosis. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 12.Nielsen, K., D. Gall, M. Lin, C. Massangill, L. Samartino, B. Perez, M. Coats, S. Hennager, A. Dajer, P. Nicoletti, and F. Thomas. 1998. Diagnosis of bovine brucellosis using a homogeneous fluorescence polarization assay. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 66:321-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen, K. H., L. Kelly, D. Gall, P. Nicoletti, and W. Kelly. 1995. Improved competitive enzyme immunoassay for the diagnosis of bovine brucellosis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 46:285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paulsen, I. T., R. Seshadri, K. E. Nelson, J. A. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, T. D. Read, R. J. Dodson, L. Umayam, L. M. Brinkac, M. J. Beanan, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. Deboy, A. S. Durkin, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, B. Ayodeji, M. Kraul, J. Shetty, J. Malek, S. E. Van Aken, S. Riedmuller, H. Tettelin, S. R. Gill, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, D. L. Hoover, L. E. Lindler, S. M. Halling, S. M. Boyle, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. The Brucella suis genome reveals fundamental similarities between animal and plant pathogens and symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13148-13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porte, F., A. Naroeni, S. Ouahrani-Bettache, and J. P. Liautard. 2003. Role of the Brucella suis lipopolysaccharide O antigen in phagosomal genesis and in inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 71:1481-1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ried, J. L., and A. Collmer. 1987. An nptI-sacB-sacR cartridge for constructing directed, unmarked mutations in gram-negative bacteria by marker exchange-eviction mutagenesis. Gene 57:239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 18.Schafer, A., A. Tauch, W. Jager, J. Kalinowski, G. Thierbach, and A. Puhler. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schurig, G. G., R. M. D. Roop, T. Bagchi, S. Boyle, D. Buhrman, and N. Sriranganathan. 1991. Biological properties of RB51; a stable rough strain of Brucella abortus. Vet. Microbiol. 28:171-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schurig, G. G., N. Sriranganathan, and M. J. Corbel. 2002. Brucellosis vaccines: past, present and future. Vet. Microbiol. 90:479-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seder, R. A., and A. V. Hill. 2000. Vaccines against intracellular infections requiring cellular immunity. Nature 406:793-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith, L. D., and T. A. Ficht. 1990. Pathogenesis of Brucella. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 17:209-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutherland, S. S., and J. Searson. 1990. The immune response to Brucella abortus: the humoral immune response, p. 65-81. In K. A. D. Nielsen and J. R. Duncan (ed.), Animal brucellosis. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 24.Ugalde, J. E., C. Czibener, M. F. Feldman, and R. A. Ugalde. 2000. Identification and characterization of the Brucella abortus phosphoglucomutase gene: role of lipopolysaccharide in virulence and intracellular multiplication. Infect. Immun. 68:5716-5723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vemulapalli, R., Y. He, L. S. Buccolo, S. M. Boyle, N. Sriranganathan, and G. G. Schurig. 2000. Complementation of Brucella abortus RB51 with a functional wboA gene results in O-antigen synthesis and enhanced vaccine efficacy but no change in rough phenotype and attenuation. Infect. Immun. 68:3927-3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]