Abstract

We developed a novel experimental strategy to study T cell regeneration after bone marrow transplantation. We assessed the fraction of competent precursors required to repopulate the thymus and quantified the relationship between the size of the different T cell compartments during T cell maturation in the thymus. The contribution of the thymus to the establishment and maintenance of the peripheral T cell pools was also quantified. We found that the degree of thymus restoration is determined by the availability of competent precursors and that the number of double-positive thymus cells is not under homeostatic control. In contrast, the sizes of the peripheral CD4 and CD8 T cell pools are largely independent of the number of precursors and of the number of thymus cells. Peripheral “homeostatic” proliferation and increased export and/or survival of recent thymus emigrants compensate for reduced T cell production in the thymus. In spite of these reparatory processes, mice with a reduced number of mature T cells in the thymus have an increased probability of peripheral T cell deficiency, mainly in the naive compartment.

Keywords: CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, homeostasis, thymus regeneration, thymus export

Introduction

Regeneration of the immune system, in the adult, is one of the major challenges of today's cell therapy. T cell regeneration from hematopoietic stem cell precursors (HSCs) is required after HIV infection and after bone marrow (BM) transplantation after aggressive cancer therapies 1 2 3. It can also be used in other clinical applications, such as gene therapy 4. In spite of major progresses in the use of HSCs for T cell reconstitution, we still lack important information. Contrary to other blood cell lineages developing from HSCs, T cell progenitors must first migrate to the thymus to mature. In the adult, this may pose a problem, as the thymus is atrophic and may no longer be able to generate T cells 5. We do not know what fraction of competent precursor cells is needed to restore complete thymus function, or what are the quantitative aspects of the regeneration of the double-positive (DP) and single-positive (SP) thymus compartments. The mechanisms that determine the number of T lymphocytes in the peripheral lymphoid system are also poorly understood. In young adult mice there is a continuous seeding of the periphery by newly formed thymus migrants 6. Nevertheless, the number of peripheral T cells remains even 7. This implies that either (a) the migrant cells are rapidly lost without ever colonizing the periphery, or (b) there is a continuous replacement of the peripheral cells by recent thymus migrants. Most studies indicate that a part of the peripheral T cell pool can be maintained independently of thymus export, but do not allow a precise evaluation of the role of thymus T cell production in physiological conditions 8. We developed a novel strategy that allows (a) a quantitative assessment of the fraction of competent pre-T cell precursors required to restore thymus function and (b) the evaluation of the contribution of the thymus to the peripheral T cell pools.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

B6.Rag2−/− 9, B6.CD3ε−/− 10, B6.TCRα−/−(11), all Ly5b, and C57Bl/6.Ly5a mice were obtained from the Centre de Devélopment des Tecniques Avancées-Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CDTA-CNRS; Orléans, France).

BM Chimeras.

Host 8-wk-old recombination activating gene (Rag)2−/−B6 mice were lethally irradiated (900 rad) with a 137Ce source and received intravenously 2 to 4 × 106 T cell–depleted BM cells from different donor mice, mixed at different ratios. T cell depletion was done by 2–3 passages in a Dynal MPC6 or AutoMacs (Miltenyi Biotec) magnetic sorter after incubating the BM cells with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and anti-CD3 biotinylated antibodies followed by anti–rat IgG1 or Streptavidin-coated Dynabeads. Purity was tested by flow cytometry and the injected BM cells were found to contain <0.1% T mature cells. By using donor and host mice who differ according to Ly5 allotype markers, we were able to discriminate between the T cells originating from the different donors. 10 to 20 wk after reconstitution mice were killed and BM, thymus, spleen, and LN cells suspensions were prepared as described 12. The total number of peripheral T cells represents the number of T cells in the spleen added to twice the number of T cells present in the mesenteric and inguinal LNs to account for the total LN mass.

Thymus Cell Export.

Mice were anesthetized, the upper chest opened, and the thymus lobes exposed. One thymus lobe was injected with 10 μl of FITC (1 mg/ml) which resulted in the labeling of ∼50–70% of all thymocytes 6. Mice were killed 24 h later and the recent thymus emigrants present in the spleen and LNs were identified by flow cytometry as live FITC+ cells expressing Ly5a, CD3, and CD4 or CD8.

Flow Cytometry Analysis.

The following monoclonal antibodies were used: anti-CD8α (53–6.7), anti-CD3ε (145–2C11), anti-CD4 (L3T4/RM4–5), anti-CD25 (PC61), anti-CD45RB, anti-CD24/HSA (M1/69) from BD PharMingen, and anti-CD44 (IM781), anti-CD62L (MEL14) from Caltag. Cell surface four color staining was performed with the appropriate combinations of FITC, PE, TRI-Color, PerCP, biotin, and allophycocyanin (APC)-coupled antibodies. Biotin-coupled antibodies were secondary labeled with APC-, TRI-Color- (Caltag), or PerCP-coupled (Becton Dickinson) streptavidin. Dead cells were excluded during analysis according to their light-scattering characteristics. All acquisitions and data analyses were performed with a FACSCalibur™ (Becton Dickinson) interfaced to the Macintosh CELLQuest™ software.

Mathematical Analysis.

The relationship between the number of competent T cells (or thymus cells) T in a given compartment and the number of competent cells N in a previous compartment was modeled by the following differential equation:

|

1 |

where s denotes the rate at which cells transit from the N compartment into the T compartment, m represents the rate at which T cells exit from the T compartment due to mortality or differentiation into the next compartment, and p represents a homeostatic regulation term. As all compartments had reached steady-state levels at the times at which the mice were killed (similar T cell recoveries were obtained 8–20 wk after BM reconstitution), the experimental data were fitted to the steady-state level corresponding to : T = sN/m + p/m. The homeostatic regulation term was included only if it significantly (α = 0.005) improved the fit to the data; in all other cases the data were fitted to the line T = sN/m. The optimal fits of the steady-state functions to the experimental data were determined using a generalized Gauss-Newton method to minimize the sum of the squared residuals (SSRs) between the logarithms of the data and the model. The logarithmic transformation was made because the experimental errors were likely to be proportional to the cell numbers measured. Note, however, that the model that was fitted (see above) is linear.

Results and Discussion

Thymus Regeneration.

Thymus regeneration can be readily obtained by the injection of a very limited number of HSC precursor cells 13. The injected self-renewing pluripotential HSCs divide and completely restore the precursor cell pools in the BM and in the thymus. During clinical BM transplantation, however, newly injected competent precursors may be diluted among the host's incompetent cells. The quantitative relationship between the fraction of competent precursor cells able to colonize the thymus and the regeneration of DP and SP thymus cell compartments has never been studied in these conditions. Here, we evaluated the regeneration of the thymus by a limited fraction of competent precursor cells. Lethally irradiated lymphopenic B6.Rag2−/− mice were reconstituted with T cell–depleted BM cells from normal B6.Ly5a donors alone or from normal B6.Ly5a and T cell–deficient B6.Ly5b mice mixed at several ratios. This strategy should reduce the number of competent precursors available for thymus colonization and regeneration, as normal Ly5a competent precursor cells are diluted among Ly5b incompetent precursors from the mutant donors 14 15. 2 to 5 mo after BM reconstitution, when all T cell compartments had reached steady-state levels, we counted the number of cells from each donor type in the CD3−CD4−CD8− (double-negative [DN]), CD4+CD8+ (DP), and mature CD4+ CD8−/CD4−CD8+ (SP) compartments. We used three types of T cell–deficient BM donors: TCRα−/− mice with a block of T cell differentiation at the DP to SP transition, which have normal numbers of DP cells, but lack mature SP T cells 11, and CD3ε−/− or Rag2−/− mice with an earlier block of T cell differentiation at the DN to DP transition, which lack DP cells 9 10. Studying thymus regeneration in the chimeras obtained with BM cells from these different mutants allows comparing the restoration of the DP and SP thymus compartments from a limited number of competent DN precursors. This could be done in the absence or in the presence of incompetent DP cells, i.e., in CD3ε−/− or Rag2−/− and in TCRα−/− mixed chimeras, respectively.

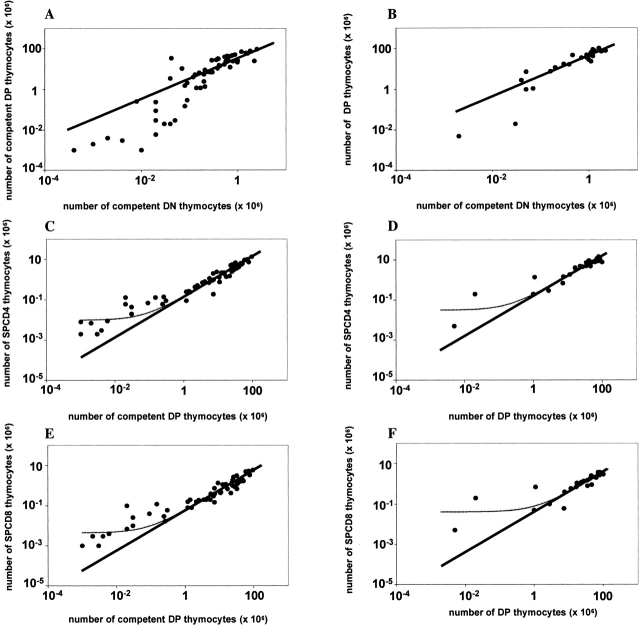

We found that the number of competent DP cells was proportional to the number of competent DN cells 15, i.e., a twofold lower number of competent DN cells resulted in a twofold reduction in the number of competent DP cells (Fig. 1A and Fig. B). This proportionality was observed both in B6.Ly5bTCRα−/−/B6.Ly5a chimeras (Fig. 1 A) whose TCRα−/− precursors can generate incompetent DP cells and in B6.Ly5bCD3ε−/−/B6.Ly5a (Fig. 1 B) or B6.Ly5bRag2−/−/B6.Ly5a chimeras (not shown), which both lack incompetent DP cells. Thus, limiting numbers of DP precursor cells do not accumulate and restore the thymus DP compartment even in the absence of competitor incompetent DP cells. These findings indicate that, when the number of precursors is fewer than normal, the total number of DP cells is not regulated by homeostatic control mechanisms, i.e., there is no increase in the rate of division or survival of DP cells in mice with small DP compartments. In steady-state conditions, the number of competent DP cells was roughly 40-fold higher than the number of competent cells in the DN compartment; i.e., ∼106 DN cells originated ∼40 × 106 DP cells. Interestingly, in mice with a very low number of competent DN cells (<105, i.e., <5% of normal) the number of competent DP cells was lower than expected from the otherwise proportional relationship between DN and DP cells (Fig. 1A and Fig. B). This may result from a limiting dilution effect due to the low frequency of competent precursors of which only 5/9 will make a productive TCRβ rearrangement and proceed in the T cell differentiation pathway. Alternatively, this could be due to a more efficient DP to SP transition at low cell numbers, which would cause depletion of the DP compartment (see below) 16. In conclusion, these findings indicate that in normal mice the number of competent DN precursor cells available strictly determines the number of DP cells.

Figure 1.

Thymus regeneration. Lethally irradiated Rag2−/− mice were reconstituted with BM cells from normal B6.Ly5a alone or diluted among incompetent BM cells from either B6.Ly5bTCRα−/− (A, C, and E) or B6.Ly5bCD3ε−/− (B, D, and F) donors. 8 to 20 wk after reconstitution the chimeras were killed and the number of competent Ly5a cells was evaluated in the different thymus cell compartments. For each chimera (•), the relationship between the number of competent cells in the CD3−CD4−CD8− (DN), CD4+CD8+ (DP) compartments is shown in A and B, between the DP and the SPCD4 compartments in C and D, and in the DP and the SPCD8 compartments in E and F. The curves show the relationships between DN, DP, SPCD4, and SPCD8 cells as predicted by the mathematical model (see Mathematical Analysis). All datasets were fitted twice: once including all data points (thin lines), and once excluding the mice with very low DN (<105) or DP (<106) cell numbers (thick lines). In A and B, both of the fits could not be significantly improved by adding a homeostatic term. Moreover, both fits predicted a too high number of competent DP cells in mice with very few competent DN cells, suggesting that an additional mechanism (not included in the model) is involved. The model we used was sufficient, however, to conclude that in mice with at least 5% of the normal number of competent DN cells, the number of competent cells in the DP compartment was proportional to the size of the DN compartment (see thick lines). Likewise, in C–F we found a proportionality between the numbers of competent DP cells and SP cells (see thick lines) in all mice except the ones with very low numbers of competent DP cells (<106). The addition of a small homeostatic term only helped to describe the relatively high SP cells numbers in the latter mice (see thin lines), while it did not improve the fits between the model and the data from all other mice. Except in very poorly reconstituted mice, the size of each thymus compartment is thus proportional to the size of the compartment that precedes it. The parameter values (see Mathematical Analysis) that gave the best fits to the data are: s/m = (A) 35, (B) 47, (C) 0.14, (D) 0.17, (E) 0.06, (F) 0.04 (thick lines), and p/m = (C) 0.01, (D) 0.03, (E) 0.005, and (F) 0.04 (thin lines).

In the thymus of the T cell–deficient/normal mixed BM chimeras the number of TCRhighSPCD4 (Fig. 1C and Fig. D) or TCRhighSPCD8 cells (Fig. 1E and Fig. F) was proportional to the number of competent DP cells. A twofold lower number of competent DP cells gave rise to a twofold lower number of TCRhigh mature SP cells recovered from the thymus. The number of CD4 and CD8 cells in the SP compartment were ∼15 and 5% of the number of competent DP cells, respectively, i.e., a DP compartment consisting of 107 cells gave rise to a SP compartment with 1.5 × 106 SPCD4 cells and 5 × 105 SPCD8 cells. At very low numbers of competent DP cells (<106) the number of SP cells was always higher than expected (see thick lines in Fig. 1). The data could therefore best be described by including a very small homeostatic term (see Mathematical Analysis). This increases the predicted number of SP cells in mice with very low numbers of competent DP cells, but does not affect the predicted number of SP cells in all other mice (see the thin lines in Fig. 1C–F). One interpretation is that there is an increased efficiency of the DP to SP transition in poorly reconstituted mice 16, probably reflecting the higher stromal cell to thymocyte cell ratio. This explanation would be consistent with the relatively small number of DP cells found in mice with few competent DN cells. However, in mice with low numbers of thymus cells we could expect that the probability of generating the correct TCR is lower, decreasing the chances of positive selection. Alternatively, a homeostatic compensation mechanism may induce the proliferation or prolonged survival of the rare SP cells. Finally, reentry of mature peripheral T cells, which is negligible in normal conditions (<0.1% of PBL), may also contribute to biases the number of SP cells in the chimeras with low thymus cell numbers. In conclusion, these results indicate that in the range of 5–100% of the normal number of thymus cells the sizes of the DP and SP cellular compartments are fully determined by the input of competent DN cells. When the fraction of competent thymus cells is below 5% of normal there is a less efficient DN to DP transition and/or a more efficient generation of mature SP T cells.

Peripheral T Cell Pool Restoration.

We showed that by decreasing the fraction of competent cells in the transplanted BM we were able to proportionally reduce the number of mature SP thymus cells. The experimental strategy employed thus allows for a quantitative correlation between T cell production in the thymus and the number of peripheral T cells. The relative contribution of the thymus to the maintenance of the peripheral T cell pool has been investigated either after thymus ablation 17 or by increasing the thymus mass with multiple ectopic transplants 18, procedures that strongly deviate from physiological conditions. Thymectomy in neonatal and adult mice results in a permanently reduced size of the peripheral T cell pool. In both cases, however, a significant number of T cells persist in absence of the thymus 19. Engraftment of multiple thymus lobes increases the functional thymus mass and the number of recent thymus emigrants. The peripheral T cell pool size, however, does not increase proportionally to the overall increase in thymus mass 20 21.

To evaluate the impact of reduced thymus mature T cell numbers on the size of the peripheral T cell pool we first examined whether a reduction in the number of SP cells matched with a reduced rate of thymus cell output. It was previously shown that the fraction of recent thymus emigrants is constant at ∼1–2% of thymocytes/day, independently of the number of thymus lobes and of an increase in the number of peripheral T cells 6 22 23. Thymus export in adult mice with diminished thymus T cell production and peripheral pools, however, has never been studied. We found here that, in chimeras with low numbers of SP cells, the sum of recent thymus emigrants (RTEs) in the peripheral lymphoid tissues was lower than in mice with normal numbers of SP cells. The relative thymus output in chimeras with low numbers of SP cells was, however, 3.2–3.4-fold higher than in control chimeras (Table ). Thus, the accessibility to thymus exit may be easier in the presence of reduced numbers of SP cells. Alternatively, RTEs may survive longer because of reduced competition in the periphery 24. These results indicate that the “efficiency” of thymus cell export increases with low numbers of thymus cells, but is insufficient to compensate for the reduced production of mature thymus cells. In conclusion, by using the mixed T cell–deficient/normal BM chimeras strategy we can reduce in a controlled fashion the production of mature SP T cells in the thymus and thereby the seeding of the peripheral tissues by thymus emigrants. Thus, this strategy indeed allows a quantitative assessment of the contribution of the thymus to the establishment and maintenance of the peripheral T cell pools.

Table 1.

Thymic Export in Mice with Reduced Thymus Function

| Recent thymus migrants (×104) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fraction of competent C57Bl6 Ly5 BM cells injected | CD4+ | CD8+ |

| 100% | 9.6 | 3.9 |

| 9.0 | 2.6 | |

| 8.6 | 4.9 | |

| 8.0 | 3.0 | |

| 6.5 | 2.5 | |

| 4.1 | 2.0 | |

| 4.9 | 2.7 | |

| 10% | 3.2 | 1.1 |

| 2.2 | 0.5 | |

| 1.2 | 0.4 | |

| 1.8 | 1.4 | |

| 1.4 | 0.8 | |

| 3.8 | 1.3 | |

| 2.3 | 0.9 | |

Thymus cell export varies according to the fraction of competent precursor cells. Rag2−/−B6 mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with BM cells from normal B6.Ly5a donors alone (100%) or from normal B6.Ly5a (10%) and T cell–deficient B6.TCRα−/−Ly5b (90%) mice. In these chimeras, the number of SP cells was proportional to the fraction of competent BM cells injected. Thymus export was evaluated 24 h after intrathymus injection of FITC.

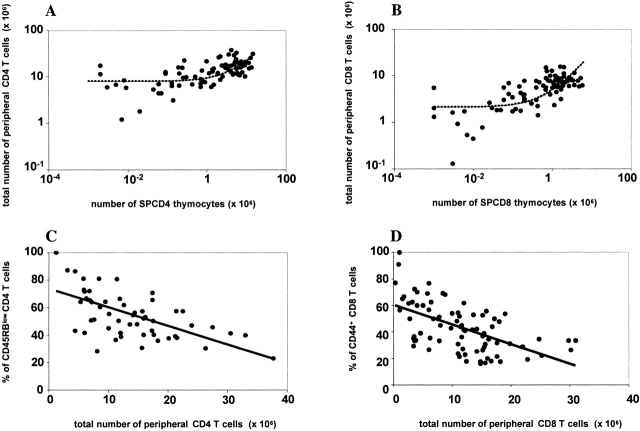

We studied the total number of peripheral CD8 and CD4 T cells in mice with reduced thymus T cell production and export. In contrast to what we reported in the thymus, we found that the total number of CD4 and CD8 cells in the periphery was not proportional to the number of cells in the previous progenitor compartment, i.e., thymus SPCD4 (Fig. 2 A) and SPCD8 cells (Fig. 2 A). In most chimeras with reduced numbers of thymus SP cells the sizes of the peripheral T cell compartments were similar to those in the chimeras with normal numbers of thymus SP cells. Mathematical analysis of the data suggests that a compensatory homeostatic mechanism be involved, even in mice with a nearly normal thymus output. We estimate that in mice in which only 1% of the normal numbers of SPCD4 cells and SPCD8 cells were present, the peripheral CD4 and CD8 compartments still contained 25 and 12.5% of the normal, respectively. Thus, in the presence of reduced thymus output, T cell survival and/or proliferation are favored 8 14 25 as to attain normal peripheral T cell numbers. In concordance, we found that the lower was the number of peripheral CD8+ or CD4+ T cells, the higher was the fraction of activated CD4+CD45RBlow (Fig. 2 C) and CD8+CD44+ (Fig. 2 D) T cells. These findings demonstrate that the numbers of peripheral CD4 and CD8 T cells are only partly determined by the rates of thymus cell production and export. In summary, these results show that chimeras with reduced numbers of SP thymocytes can have normal peripheral T cell numbers, suggesting that in normal mice thymus T cell production exceeds the quantitative requirements to replenish the number of T cells in the peripheral pool. Chimeras with very low numbers of SP thymus cells do, however, have an increased probability of not being able to fully reconstitute the CD4 and the CD8 peripheral compartments.

Figure 2.

Restoration of the total peripheral T cell pools. Panel A shows the relationship between the number of peripheral Ly5a CD4 T cells (SPL+LN) and the number of competent Ly5a SPCD4 cells in the thymus of each individual B6.Ly5a/B6.Ly5bTCRα−/− or B6.Ly5a/B6.CD3ε−/−Ly5b chimera. (B) The same but for CD8 T cells. The data were fitted to the steady-state level corresponding to including the homeostatic term (dashed lines), as this significantly improved the fits to the data, even if mice with very low SP numbers (<105) were not taken into account (not shown). Parameter results are: s/m = (A) 1.5, (B) 2.8, and p / m = (A) 8.0, (B) 2.1. Panel C shows the percentage of activated/memory CD45RBlowCD4+ T cells as a function of the total number of peripheral CD4 T cells, while D shows the percentage of activated/memory CD44+CD8+ cells as a function of the total number of peripheral CD8 T cells. The lines in C and D are linear regression lines with r = −0.6 in both cases.

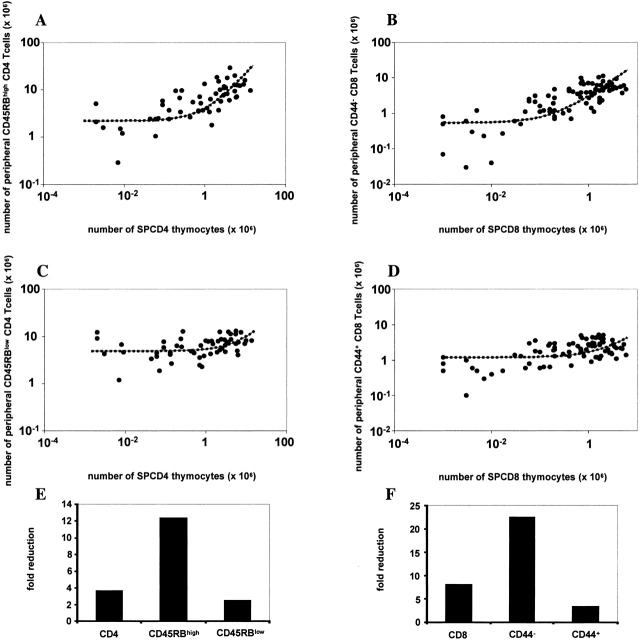

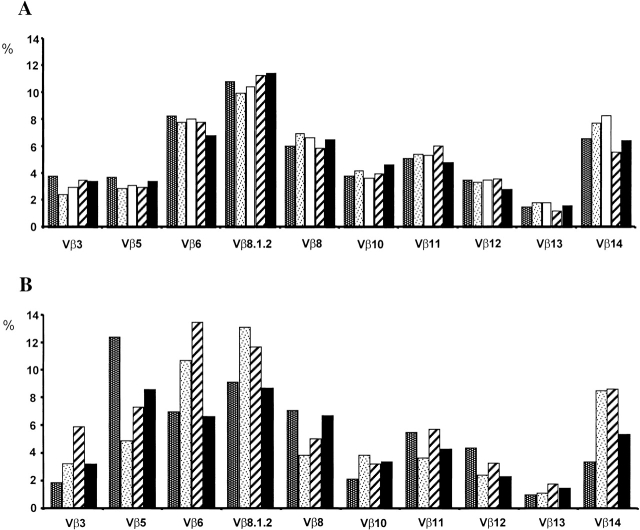

Previous observations have lead to the definition of two cellular compartments in the peripheral T cell pool, with independent homeostatic regulation 26. There is a pool of naive T cells which is dependent on thymus T cell production comprising all recent thymus emigrants 21 and a pool of activated/memory T cells capable of persisting in absence of thymus output 27. We define a naive T cell as a cell that does not express activation markers, i.e., in B6 mice, CD4 T cells that are CD45RBhigh, and CD8 T cells that are CD44−. We compared the effects of a reduced thymus output on the establishment of the naive (CD4+ CD45RBhigh and CD8+CD44−; Fig. 3A and Fig. B) and the memory/activated (CD4+CD45RBlow and CD8+CD44+; Fig. 3C and Fig. D) peripheral T cell compartments. We found that the numbers of both naive and memory/activated T cells were not proportional to the number of thymus SP mature T cells. Upon a 100-fold reduction in the SP thymus cells, i.e., in mice with 1% of the normal number, there was a threefold reduction of the activated/memory cells, while the naive CD4 and CD8 compartments decreased 12- and 23-fold, respectively (Fig. 3E and Fig. F). These results suggest the existence of a hierarchical organization that favors the replenishment of the activated/memory T cell pool in lymphopenic mice, as described previously for B cells 28. The size of the memory/activated compartment is thus indeed less dependent on thymus export than the size of the naive T cell pool. Still, the mice with very low thymus T cell production had an increased probability of not being able to fully reconstitute the peripheral memory/activated pools. Additionally, the diversity of the TCR repertoire in mice with very low T cell production was impaired. We studied the TCR Vβ chain expression by peripheral T cells in chimeras reconstituted with 100 or 1% competent BM cells. We found that while the patterns of Vβ chain usage in chimeras with normal thymus output were identical (Fig. 4 A), in mice with low thymus output they were unique in each individual mouse (Fig. 4 B). These findings suggest that in the presence of low thymus output the homeostatic proliferation of a few rare T cells lead to the establishment of an oligoclonal T cell repertoire 29. This may also explain the shift of peripheral T cell repertoires observed during aging, after thymus atrophy and reduced T cell production 5.

Figure 3.

Restoration of the naive and activated/memory T cell pools. Panel A shows the relationship between the number of SPCD4 cells and the number of peripheral naive CD45RBhighCD4+ T cells. (B) The relationship between the number of SPCD8 and the number of peripheral naive CD44−CD8+ T cells. (C) The relationship between the number of SPCD4 and the number of peripheral activated/memory CD45RBlowCD4+ T cells. (D) The relationship between the number of SPCD8 and the number of peripheral activated/memory CD44+CD8+ T cells in all B6.Ly5a/B6.Ly5bTCRα−/− and B6.Ly5a/B6.Ly5bCD3ε−/− chimeras. The data were fitted to the steady-state level corresponding to including the homeostatic term, as this significantly improved the fits to the data, even if mice with very low SP numbers (<105) were excluded (not shown). Parameter results are: s/m = (A) 2.0, (B) 2.6, (C) 0.5, (D) 0.5, and p / m = (A) 2.2, (B) 0.5, (C) 5.0, (D) 1.2. E and F show the fold reductions in the total, naive (CD45RBhighCD44−) and activated/memory (CD45RBlowCD44+) CD4 (E) and CD8 (F) peripheral compartments resulting from a 100-fold reduction (compared with fully reconstituted mice) in the thymus SPCD4 and SPCD8 compartments, respectively.

Figure 4.

Vβ TCR repertoires in chimeras with normal and low T cell numbers. Representation of the different Vβ TCR families by the spleen T cells of different BM chimeras. Mice were reconstituted with either 100% BM cells from normal B6.Ly5a mice (A) or with a mixture of 1% BM cells from normal B6.Ly5a mice and 99% BM cells from T cell–deficient B6.Ly5a/B6.Ly5bTCRα−/− donors (B). Each bar represents the percentage of CD3+CD4+ T cells expressing each Vβ family in individual mice as assessed by flow cytometry. Similar results were obtained with CD3+CD8+ spleen T cells. Note that although the representation of each Vβ family is identical in all mice reconstituted with 100% BM cells from normal donors, it shows individual variations in mice reconstituted with a limited fraction of competent BM cells.

Concluding Remarks.

We developed a novel experimental strategy to study T cell regeneration in mice with a limited fraction of competent precursor cells. The results obtained have major implications to the understanding of thymus regeneration after BM transplantation 1. We directly demonstrated that complete regeneration of the thymus DP and SP compartments is strictly determined by the availability of a sufficient fraction of competent DN precursors. This is due to the lack of compensatory homeostatic mechanisms that could increase the proliferation or survival of DP and SP thymus cells. Only when the number of thymus DN cell precursors is less than 5% of normal, reparatory mechanisms increase the efficiency of generation of mature SP T cells. These processes are nevertheless insufficient to overcome the deficit in precursor cell numbers. Our results suggest that complete thymus regeneration requires the complete elimination of incompetent precursor cells to prevent dilution of competent precursors and consequently the reduction of the fraction of competent DN cells present in the thymus.

These results also shed light on the mechanisms of peripheral T cell restoration after tri-therapy of HIV infected individuals 30 31 32. By studying the peripheral T cell pools in mice with reduced thymus function we show that the size of the total peripheral T cell pool is regulated largely independently of thymus output. At the periphery, several compensatory mechanisms operate to bypass the reduced production of mature T cells in the thymus. We show, for the first time, that in mice with smaller thymus SP cell numbers and peripheral T cell pools the efficiency of thymus cell export improves. More importantly, homeostasis induces preferential activation of rare naive T cells and proliferation in the memory/activated pool. In spite of all these redeeming processes, insufficient production of mature T cells resulted in an increased probability of peripheral T cell deficiency, mainly in the naive compartment. Proliferation of peripheral T cells in lymphopenic mice (“homeostatic” proliferation) was previously described either in thymectomized mice during T cell recovery following T cell elimination 12 or following the fate of T cells adoptively transferred into T cell deficient hosts 33 34 35 36 37 38 39. Here we used a different approach to study peripheral T cell restoration that allowed us to establish a direct quantitative relationship between thymus function and peripheral T cell numbers. In summary, our studies demonstrate that complete peripheral T cell recovery requires a minimally functional thymus, which can only be ensured with a minimal number of competent DN precursors. Thus, the incomplete peripheral T cell restoration that is observed in most HIV patients after tri-therapy may reflect thymus compromise, which should be taken in consideration in the development of new therapeutic approaches 2 3 40.

Finally, these results also bear interest on the mechanisms of immune deficiency developing with aging. We found that mice with <1% of the normal number of thymus SP cells have reduced numbers of naive T cells and develop oligoclonal repertoires, a situation that mimics the evolution of the immune system in aged individuals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. B. Rocha, A. McLean, R.J. de Boer, and C. Kesmir for kindly reviewing this manuscript, and F. Agenes for suggestions.

This work was supported by grants from the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida (ANRS), Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC), Ministére de L'Éducation Nationale de la Recherche et de la Technologie (MNERT), Sidaction, Centre National de la Recherche Medicale, and the Institut Pasteur. A. Almeida is supported by grant 13302/97 from the Fundação Ciência e Tecnologia, Praxis XXI, Portugal, and J. Borghans by a Marie Curie Fellowship of the EC program Quality of Life (contract 1999-01548).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: BM, bone marrow; DN, double negative; DP, double positive; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell precursor; Rag, recombination activating gene; SP, single positive.

References

- Mackall C.L., Hakim F.T., Gress R.E. Restoration of T-cell homeostasis after T-cell depletion. Semin. Immunol. 1997;9:339–346. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douek D.C., Vescio R.A., Betts M.R., Brenchley J.M., Hill B.J., Zhang L., Berenson J.R., Collins R.H., Koup R.A. Assessment of thymic output in adults after haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation and prediction of T-cell reconstitution. Lancet. 2000;355:1875–1881. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux E., Dumont-Girard F., Starobinski M., Siegrist C.A., Helg C., Chapuis B., Roosnek E. Recovery of immune reactivity after T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation depends on thymic activity. Blood. 2000;96:2299–2303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzana-Calvo M., Hacein-Bey S., de Saint Basile G., Gross F., Yvon E., Nusbaum P., Selz F., Hue C., Certain S., Casanova J.L. Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease. Science. 2000;288:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackall C.L., Gress R.E. Thymic aging and T-cell regeneration. Immunol. Rev. 1997;160:91–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollay R.G., Butcher E.C., Weissman I.L. Thymus cell migration. Quantitative aspects of cellular traffic from the thymus to the periphery in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 1980;10:210–218. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830100310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas A.A., Rocha B.B. Lymphocyte lifespanshomeostasis, selection and competition. Immunol. Today. 1993;14:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90320-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas A.A., Rocha B. Lymphocyte population biologythe flight for survival. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:83–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai Y., Rathbun G., Lam K.-P., Oltz E.M., Stewart V., Mendensohn M., Charron J., Datta M., Young F., Stall A.M., Alt F.W. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malissen M., Gillet A., Ardouin L., Bouvier G., Trucy J., Ferrier P., Vivier E., Malissen B. Altered T cell development in mice with a targeted mutation of the CD3-epsilon gene. EMBO J. 1995;14:4641–4653. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P., Clarke A.R., Rudnicki M.A., Iacomini J., Itohara S., Lafaille J.J., Wang L., Ichikawa Y., Jaenisch R., Hooper M.L. Mutations in T-cell antigen receptor genes alpha and beta block thymocyte development at different stages. Nature. 1992;360:225–231. doi: 10.1038/360225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha B., Freitas A.A., Coutinho A.A. Population dynamics of T lymphocytes. Renewal rate and expansion in the peripheral lymphoid organs. J. Immunol. 1983;131:2158–2164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezine S., Weissman I.L., Rouse R.V. Bone marrow cells give rise to distinct cell clones within the thymus. Nature. 1984;309:629–631. doi: 10.1038/309629a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agenes F., Rosado M.M., Freitas A.A. Independent homeostatic regulation of B cell compartments. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27:1801–1807. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meerwijk J.P., Marguerat S., MacDonald H.R. Homeostasis limits the development of mature CD8+ but not CD4+ thymocytes. J. Immunol. 1998;160:2730–2734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann M., Scott B., Kisielow P., von Boehmer H. Kinetics and efficacy of positive selection in the thymus of normal and T cell receptor transgenic mice. Cell. 1991;66:533–540. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.F. Effect of thymectomy in adult mice on immunological responsiveness. Nature. 1965;208:1337–1338. doi: 10.1038/2081337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf D. Multiple thymus grafts in aged mice. Nature. 1965;208:87–88. doi: 10.1038/208087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutman O. Postthymic T-cell development. Immunol. Rev. 1986;91:159–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1986.tb01488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuchars E., Wallis V.J., Doenhoff M.J., Davies A.J., Kruger J. Studies of hyperthymic mice. I. The influence of multiple thymus grafts on the size of the peripheral T cell pool and immunological performance. Immunology. 1978;35:801–809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzins S.P., Boyd R.L., Miller J.F. The role of the thymus and recent thymic migrants in the maintenance of the adult peripheral lymphocyte pool. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1839–1848. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.11.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabor M.J., Scollay R., Godfrey D.I. Thymic T cell export is not influenced by the peripheral T cell pool. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27:2986–2993. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzins S.P., Godfrey D.I., Miller J.F., Boyd R.L. A central role for thymic emigrants in peripheral T cell homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9787–9791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas A.A., Agenes F., Coutinho G.C. Cellular competition modulates survival and selection of CD8+ T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:2640–2649. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldrath A.W., Bogatzki L.Y., Bevan M.J. Naive T cells transiently acquire a memory-like phenotype during homeostasis-driven proliferation. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:557–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanchot C., Rocha B. The peripheral T cell repertoireindependent homeostatic regulation of virgin and activated CD8+ T cell pools. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:2127–2136. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanchot C., Rocha B. The organization of mature T-cell pools. Immunol. Today. 1998;19:575–579. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agenes F., Freitas A.A. Transfer of small resting B cells into immunodeficient hosts results in the selection of a self-renewing activated B cell population. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:319–330. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruta N.L., Driel I.R., Gleeson P.A. Peripheral T cell expansion in lymphopenic mice results in a restricted T cell repertoire. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:3380–3386. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2000012)30:12<3380::AID-IMMU3380>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autran B., Carcelain G., Li T.S., Blanc C., Mathez D., Tubiana R., Katlama C., Debre P., Leibowitch J. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science. 1997;277:112–116. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho D.D., Neumann A.U., Perelson A.S., Chen W., Leonard J.M., Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X., Ghosh S.K., Taylor M.E., Johnson V.A., Emini E.A., Deutsch P., Lifson J.D., Bonhoeffer S., Nowak M.A., Hahn B.H. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R.A., Stutman O. T cell repopulation from functionally restricted splenic progenitors10,000-fold expansion documented by using limiting dilution analyses. J. Immunol. 1984;133:2925–2932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas A.A., Rocha B., Coutinho A.A. Lymphocyte population kinetics in the mouse. Immunol. Rev. 1986;91:5–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1986.tb01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha B., Dautigny N., Pereira P. Peripheral T lymphocytesexpansion potential and homeostatic regulation of pool sizes and CD4/CD8 ratios in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 1989;19:905–911. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha B., von Boehmer H. Peripheral selection of the T cell repertoire. Science. 1991;251:1225–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1900951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender J., Mitchell T., Kappler J., Marrack P. CD4+ T cell division in irradiated mice requires peptides distinct from those responsible for thymic selection. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:367–374. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldrath A.W., Bevan M.J. Low-affinity ligands for the TCR drive proliferation of mature CD8+ T cells in lymphopenic hosts. Immunity. 1999;11:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80093-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.S., Ahn C., Ernst B., Sprent J., Surh C.D. Thymic selection by a single MHC/peptide ligandautoreactive T cells are low-affinity cells. Immunity. 1999;10:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry T.J., Connick E., Falloon J., Lederman M.M., Liewehr D.J., Spritzler J., Steinberg S.M., Wood L.V., Yarchoan R., Zuckerman J. A potential role for interleukin-7 in T-cell homeostasis. Blood. 2001;97:2983–2990. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]