Abstract

The cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) of Haemophilus ducreyi is comprised of the CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC proteins, with the CdtB protein having demonstrated enzymatic (i.e., DNase) activity. Using a single recombinant Escherichia coli strain with two plasmids individually containing the H. ducreyi cdtA and cdtC genes, we purified a noncovalent CdtA-CdtC complex. Incubation of this CdtA-CdtC complex with HeLa cells blocked killing of these cells by CDT holotoxin. Furthermore, the addition of purified recombinant CdtB to HeLa cells preincubated with the CdtA-CdtC complex resulted in the killing of these human epithelial cells.

Haemophilus ducreyi is the etiologic agent of chancroid, a sexually transmitted genital ulcer disease prevalent in some developing countries (33). While the mechanism(s) by which this gram-negative bacterium causes genital ulceration remains to be determined (31), it has been established that this pathogen produces at least two toxins. The first of these is a cytotoxin with hemolytic activity (20, 21); killing of human cells in vitro by this hemolysin requires direct contact between the bacterium and the eukaryotic cells (2, 19). The other toxin can be detected by its activity in H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid (26) and is a member of the cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) family (4, 24).

The protein constituents of H. ducreyi CDT are encoded by the chromosomal cdtABC genes (4). First described by Johnson and Lior as being present in culture supernatant fluids from clinical isolates of Escherichia coli (12) and Campylobacter species (11), all CDTs have in common the fact that they are encoded by three-gene clusters and can kill a variety of human epithelial cells as well as other cell types (24). The CDT of H. ducreyi was first described phenotypically by Purven and Lagergard (26). Similar to the CDT of other pathogens (22-24, 28), all three cdt gene products must be present for CDT activity to be detected in H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid (16). The protein products of the individual cdt genes of H. ducreyi are most similar (i.e., >90% identity) to those of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (18). The calculated molecular weights of the mature form of these three proteins are as follows: CdtA, 22,855; CdtB, 28,955; and CdtC, 18,356.

There is now considerable evidence to indicate that the CDT holotoxin, at least for H. ducreyi (9), Campylobacter jejuni (14), and A. actinomycetemcomitans (1, 17, 27), is comprised of CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC bound together to form a tripartite toxin. Determination of the function of the individual cdt gene products has proven challenging, however. The CdtB protein from several different bacterial pathogens has been shown to possess DNase activity (7, 8, 10, 13, 17) when introduced into or expressed within eukaryotic cells, and there seems to be a reasonable consensus that a functional CdtB molecule is essential for expression of toxicity by CDT (15). This property of DNase activity inherent in the CdtB protein is consistent with reports of CDT causing arrest of different cell types in the G2/M or G1 and G2 phases of the cell cycle (3, 5, 10, 15, 24, 29, 30).

In contrast, information about the function of the CdtA and CdtC proteins is limited and, in the case of the latter macromolecule, conflicting. No cytotoxicity has been attributed to the CdtA protein to date, regardless of the organism from which it was cloned or purified (1, 9, 9, 14, 17, 27). However, it was recently reported that CdtA from A. actinomycetemcomitans binds to the surface of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, and it was suggested that this protein works alone to bind the CDT holotoxin to the eukaryotic cell surface (17), although it has also been proposed that CdtA and CdtC form a complex which is required for the delivery of CdtB into the eukaryotic cell (14, 15). The actual function of the CdtC protein is unresolved, with one recent report (17) indicating that recombinant CdtC from A. actinomycetemcomitans has toxic activity when introduced into CHO cells, whereas another group found that recombinant CdtC from C. jejuni was not toxic when expressed in Henle-407 intestinal epithelial cells (13). Prior to these reports, laboratories working with H. ducreyi CDT (4, 25) and A. actinomycetemcomitans CDT (18) indicated that antibody to the CdtC protein was protective against cytotoxic activity, although there were no data available to indicate whether these antibodies prevented toxin binding directly or neutralized cytotoxic activity by another mechanism. In the present report, we describe our finding that the H. ducreyi CdtA and CdtC proteins form a noncovalent complex which can prevent killing by CDT holotoxin and which will also facilitate killing of HeLa cells by purified CdtB.

The H. ducreyi CdtA and CdtC proteins form a noncovalent complex.

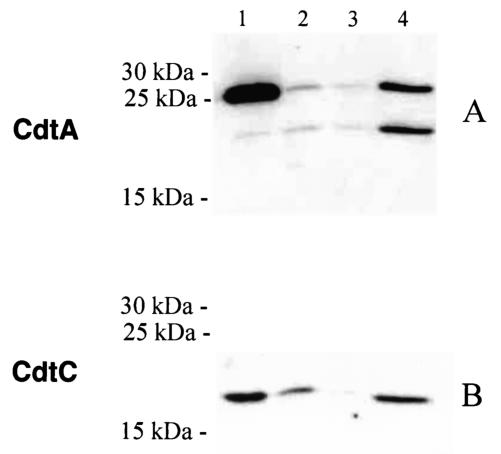

To determine whether H. ducreyi CdtA and CdtC might form a complex essential for binding of the CDT holotoxin to the cell surface, we first prepared a periplasmic extract from E. coli strain XL1-Blue(pDL20-A pJL300-C) (Table 1) that contained the H. ducreyi cdtA and cdtC genes on two separate plasmids as described previously (6, 16). Western blot analysis of this periplasmic extract using the H. ducreyi CdtA-reactive monoclonal antibody (MAb) 1G8 (Fig. 1A, lane 2) and the H. ducreyi CdtC-reactive MAb 8C9 (Fig. 1B, lane 2) confirmed that both of these proteins were expressed by this recombinant strain. This periplasmic extract was then subjected to immunoaffinity chromatography using the H. ducreyi CdtC-reactive MAb 8C9 covalently coupled to Affi-Gel Hz hydrazide (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) as described previously (6); proteins were eluted from this column using 0.1 M glycine-HCl (pH 2.5) containing 0.5 M NaCl, and the eluted fractions (1 ml each) were immediately neutralized with 50 μl of 1.0 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.5). A complex containing both CdtA (Fig. 1A, lane 4) and CdtC (Fig. 1B, lane 4) bound to this immunoaffinity column; this result indicated that a noncovalent CdtA-CdtC complex can be formed in the absence of the CdtB protein.

TABLE 1.

Recombinant plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pJL300 | pBR322 with a 3-kb H. ducreyi 35000 DNA insert containing the cdtABC gene cluster | 32 |

| pDL20-A | Modified pBR322 with a 1.1-kb PCR-derived PstI-EcoRI DNA fragment containing the H. ducreyi cdtA gene | 16 |

| pLDC101 | pRSET (Invitrogen) expressing a His-tagged CdtA protein | 4 |

| pQE-b | pQE-60 (Qiagen) expressing a His-tagged CdtB protein | 6 |

| pJL300-C | pLS88 with a 813-bp PCR-derived fragment containing the H. ducreyi cdtC gene | 32 |

FIG. 1.

Purification of a CdtA-CdtC complex by immunoaffinity chromatography. A periplasmic extract from E. coli DH5α(pJL300) (i.e., contains the H. ducreyi cdtABC gene cluster) (32) was used here as a positive control for MAb reactivity (lane 1). A periplasmic extract from E. coli XL1-Blue(pDL20-A pJL300-C) (lane 2) was subjected to immunoaffinity chromatography with the H. ducreyi CdtC-reactive MAb 8C9. These periplasmic fractions as well as the unbound effluent from the column (lane 3) and the protein eluted from the column (lane 4) were probed with the H. ducreyi CdtA-reactive MAb 1G8 (A) and the H. ducreyi CdtC-reactive MAb 8C9 (B) in Western blot analysis. The lower band (i.e., faster-migrating) of the pair of MAb 1G8-reactive antigens in panel A represents a processing or degradation product derived from the 25-kDa CdtA protein and has been described previously by this laboratory and others (6, 9). Molecular mass markers are provided on the left side of each panel.

The CdtA-CdtC complex blocks killing by CDT holotoxin.

We next determined whether this CdtA-CdtC complex might affect the killing of human cells by H. ducreyi CDT. HeLa cells (ATCC CRL 7923) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1% (vol/vol) GlutaMAX I, and both penicillin and streptomycin. These cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells in 0.5 ml of growth medium per well in a 24-well tissue culture plate and incubated in an atmosphere of 95% air-5% CO2 at 37°C. After overnight growth of these HeLa cells, they were exposed to 2 ml of H. ducreyi strain 35000HP culture supernatant fluid prepared as described previously (16) and diluted 1:1 with tissue culture medium. After 3 h, the culture supernatant fluid was removed and 2 ml of fresh tissue culture medium was added. After 72 h, the cells were either stained with Giemsa and photographed at ×40 magnification on an OLYMPUS inverted research microscope as described previously (16) or used in the Cell Titer 96Aqueous One Solution cell proliferation assay (Promega, Madison, Wis.) to determine the extent of cytotoxicity as described previously (16).

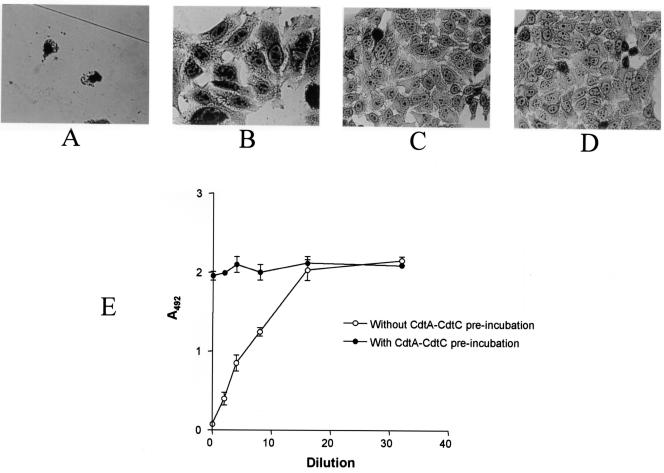

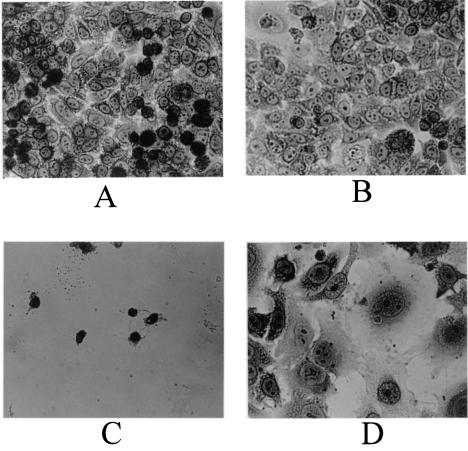

Exposure of the HeLa cells to the H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid resulted in complete killing (Fig. 2A). To determine whether the CdtA-CdtC complex would affect killing of these cells by the CDT holotoxin, purified CdtA-CdtC complex (10 μg) in 0.5 ml of tissue culture medium was incubated with the HeLa cells for 30 min at 37°C prior to the addition of H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid. Exposure of the HeLa cells to this CdtA-CdtC complex protected the HeLa cells against killing, with the surviving cells being somewhat distended (Fig. 2B). HeLa cells incubated with only the CdtA-CdtC complex (Fig. 2D) followed by uninoculated, sterile H. ducreyi growth medium were not killed and resembled control cells (Fig. 2C) not exposed to either the CdtA-CdtC complex or H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid.

FIG. 2.

Preincubation of HeLa cells with the purified CdtA-CdtC complex inhibits killing by the H. ducreyi CDT holotoxin. (A) HeLa cells incubated with buffer for 30 min prior to exposure to H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid. (B) HeLa cells incubated with the purified CdtA-CdtC complex for 30 min prior to exposure to H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid. (C) HeLa cells not exposed to either purified CdtA-CdtC complex or H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid (negative control). (D) HeLa cells incubated with purified CdtA-CdtC complex for 30 min prior to exposure to sterile, uninoculated H. ducreyi culture medium. (E) HeLa cells exposed to serial dilutions of H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid with or without preincubation with the purified CdtA-CdtC complex. Viability of these cells was determined by measuring the reduction of a tetrazolium compound into a colored formazan product at 492 nm as described previously (16). The results depicted in Fig. 2E represent the mean for two experiments.

Serial dilution of the H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid prior to its use in this HeLa cell killing assay revealed that with increasing dilution, the proportion of distended HeLa cells increased while the number of dead (i.e., rounded) HeLa cells decreased up to a dilution factor of 1:16 (data not shown). The latter amount of CDT holotoxin caused the majority of the HeLa cells to be simply distended, but these cells were still viable as determined by the use of the cytotoxicity assay (Fig. 2E). However, when the HeLa cells were preincubated with the purified CdtA-CdtC complex, even exposure to undiluted H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid did not cause cell death within the assay period (Fig. 2E). This experiment and all of the other HeLa cell killing experiments in this study were performed at least twice.

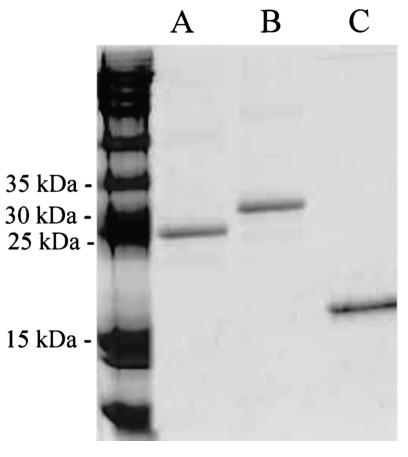

To determine whether CdtA or CdtC could individually block the killing of HeLa cells by the CDT holotoxin, we used a previously described immunoaffinity-based purification scheme (6) to purify recombinant CdtC from periplasmic extracts from E. coli XL1-Blue(pJL300-C) (Fig. 3, lane C). The pJL300-C plasmid contains the H. ducreyi strain 35000 cdtC gene (32). A His-tagged CdtA protein was purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) (pLDC101) using metal affinity chromatography. The pLDC101 plasmid contains DNA encoding the mature form of the H. ducreyi strain 35000 CdtA protein together with an N-terminal His tag (4). Briefly, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside-induced cells of this recombinant strain were harvested from a 1-liter broth culture and suspended in 80 ml of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0] containing 8 M urea and 100 mM NaCl). The resultant suspension was agitated gently for 1.5 h at 4°C. After centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 20 min, the supernatant was mixed with 8 ml of TALON beads (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) previously equilibrated with lysis buffer, and the mixture was agitated gently for 20 min at room temperature. The TALON beads were then packed in a column and washed five times with 80 ml of lysis buffer followed by five washes with 80 ml of lysis buffer containing 10 mM imidazole. The His-tagged CdtA protein bound to the column was eluted with 8 ml of lysis buffer containing 100 mM imidazole. This eluate was dialyzed in stepwise fashion against 4, 2, and 0 M urea in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 100 mM NaCl to obtain purified, His-tagged CdtA (Fig. 3, lane A). Recombinant His-tagged H. ducreyi CdtB (Fig. 3, lane B) was purified from E. coli M15(pQE-b pREP4) as described previously (6).

FIG. 3.

Detection of purified, recombinant H. ducreyi CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC proteins. Each purified protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lanes: A, His-tagged CdtA; B, His-tagged CdtB; C, CdtC. Molecular size markers are present on the left.

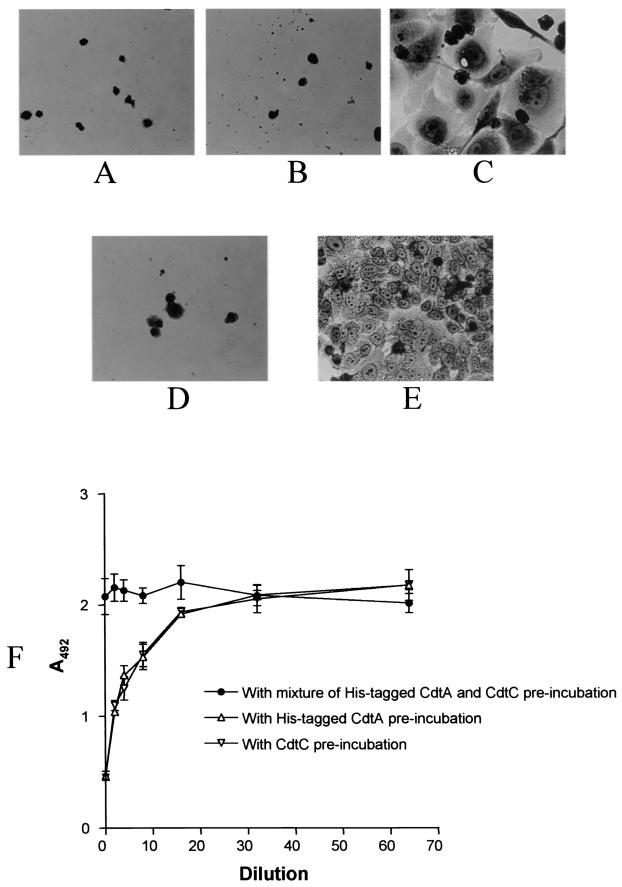

When either 5 μg of His-tagged CdtA (Fig. 4A) or 5 μg of purified CdtC (Fig. 4B) in 0.5 ml of tissue culture medium was incubated with the HeLa cells for 30 min at 37°C prior to addition of the H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid, the HeLa cells were killed as readily as HeLa cells that were not preincubated with either purified protein (Fig. 4D). When both His-tagged CdtA and purified CdtC (5 μg each) were incubated with the HeLa cells for 30 min prior to addition of the H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid, their combined presence did have some protective effect against killing (Fig. 4C). The use of the quantitative cytotoxicity assay (Fig. 4F) confirmed this protective effect, indicating that the presence of both CdtA and CdtC is required for blocking of the killing of HeLa cells by the CDT holotoxin.

FIG.4.

Effect of purified, His-tagged CdtA and purified CdtC on killing of HeLa cells by H. ducreyi CDT. HeLa cells were incubated with 5 μg of His-tagged CdtA (A), 5 μg of CdtC (B), 5 μg each of His-tagged CdtA and CdtC (C), or buffer (D) for 30 min prior to exposure to H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid. Panel E contains HeLa cells not exposed to H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid. Panel F shows viability of HeLa cells exposed to serial dilutions of H. ducreyi culture supernatant fluid after preincubation with both purified His-tagged CdtA and purified CdtC, with only purified His-tagged CdtA (open triangle), or with only purified CdtC (open inverted triangle). Viability of these cells was determined by measuring the reduction of a tetrazolium compound into a colored formazan product at 492 nm as described previously (16). These results are the mean from two experiments.

The CdtA-CdtC complex facilitates killing of HeLa cells by the CdtB protein.

The apparent ability of the CdtA-CdtC complex to block killing by CDT holotoxin raised the possibility that this complex, once bound to the eukaryotic cell surface, might also interact with the CdtB protein to promote killing of HeLa cells. To investigate this possibility, HeLa cells in 24-well plates were cooled to 4°C before 10 μg of purified CdtA-CdtC complex was added. The HeLa cells were then incubated with the CdtA-CdtC complex at 4°C for 30 min, after which the monolayers were washed three times with 2 ml of cold tissue culture medium. Then, 5 μg of CdtB in 0.5 ml of tissue culture medium was added and incubated with the HeLa cells for 3 h at 37°C. Subsequently, unbound CdtB was washed away with 2 ml of fresh medium, and the cells were incubated with fresh medium for 72 h before being photographed. This sequence of events resulted in killing of the HeLa cells (Fig. 5C). This last result indicated that the CdtA-CdtC complex which bound the HeLa cells at 4°C was functional and able to bind CdtB and presumably cause internalization of the CdtB protein. In contrast, if this experiment was modified such that buffer was substituted for the CdtA-CdtC complex (Fig. 5B) or CdtB (Fig. 5A), then there was no apparent effect on the HeLa cells. If the purified CdtA-CdtC complex was preincubated with the CdtC-reactive MAb 8C9 before this complex was added to the HeLa cells, only cell distension was observed after the HeLa cells were treated with His-tagged CdtB as described above (Fig. 5D).

FIG. 5.

Addition of purified CdtB to HeLa cells preincubated with the CdtA-CdtC complex causes killing. Purified CdtA-CdtC complex (10 μg) or buffer was incubated with the HeLa cells at 4°C for 30 min. The liquid in each well was then aspirated, and the monolayer was washed gently three times with 2 ml of cold tissue culture medium. A 0.5-ml portion of cold tissue culture medium was then added to each well, followed by the addition of 5 μg of His-tagged CdtB or buffer. The tissue culture plate was then incubated at 37°C for 3 h, at which time the medium was aspirated and the monolayer was washed once. Fresh tissue culture medium (2 ml) was added to each well, and then the plate was incubated for 72 h at 37°C. (A) HeLa cells preincubated with the purified CdtA-CdtC complex and then incubated with buffer instead of His-tagged CdtB. (B) HeLa cells preincubated with buffer instead of CdtA-CdtC complex and then incubated with His-tagged CdtB. (C) HeLa cells preincubated with CdtA-CdtC complex and then incubated with His-tagged CdtB. (D) HeLa cells preincubated with a CdtA-CdtC complex that was itself preincubated with the CdtC-reactive MAb 8C9 and then incubated with His-tagged CdtB.

Detection of CdtA and CdtC on HeLa cells.

The experiments described above did not allow us to eliminate the possibility that either CdtA or CdtC is modified by the other protein and then only that single modified protein binds the surface of the HeLa cell to form the binding component of CDT. To address this possibility, we determined whether both CdtA and CdtC were bound to the HeLa cells after these cells were incubated with the CdtA-CdtC complex. HeLa cells were grown in a 75-cm2 tissue culture flask to 80% confluency and then cooled to 4°C. His-tagged CdtA (100 μg) or purified CdtC (100 μg) or 100 μg of each of these purified proteins in 5 ml of tissue culture medium was incubated with the precooled HeLa cells at 4°C for 3 h. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with 50 ml of cold tissue culture medium. The cells were then scraped into 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline, subjected to centrifugation at 153 × g for 10 min, and suspended in 0.5 ml of 3% (wt/vol) 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate in phosphate-buffered saline. The suspended cells were gently agitated at room temperature for 1 h to facilitate lysis and then subjected to centrifugation at 27,000 × g for 15 min. The resultant supernatant was probed in Western blot analysis with CdtA- and CdtC-reactive MAbs.

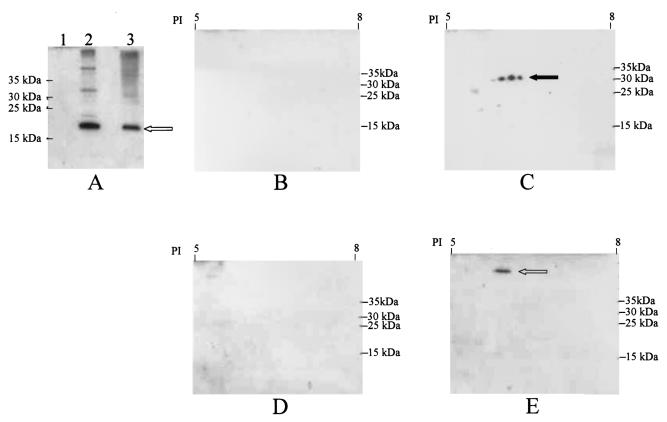

CdtC was readily detectable in the extract of the HeLa cells that had been incubated with the mixture of His-tagged CdtA and CdtC (Fig. 6A, lane 2). However, CdtC could not be detected in the extract of the HeLa cells that had been incubated with only CdtC (Fig. 6A, lane 1). When the CdtA-reactive MAb 1G8 was used to probe these same HeLa cell extracts, it was found to react with at least one HeLa cell protein that migrated to the same position in one-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as did purified His-tagged CdtA protein (data not shown). To circumvent this problem, the HeLa cell extracts were subjected to two-dimensional SDS-PAGE prior to Western blot analysis. To accomplish this, the HeLa cell extracts were desalted by using the Perfect-FOCUS protein sample preparation kit (Gene Technology, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.). The resultant preparations were solubilized with 8 M urea, 4% (wt/vol) 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate, 10 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.2% (vol/vol) Bio-lytes (pH 3 to 10) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The isoelectrofocusing step was carried out using immobilized pH gradient strips (pH 5 to 8) (Bio-Rad) in a Bio-Rad PROTEAN IEF Cell. The strips were prepared according to recommendations of the supplier. Isoelectrofocusing was initially carried out at 250 V for 70 V · h and then at 3,000 V for 30,000 V · hr. After isoelectrofocusing, the strips were incubated for 10 min in a solution containing 6 M urea, 2% (wt/vol) dithiothreitol, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, and 0.375 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8) and for another 10 min in a solution containing 6 M urea, 2.5% (wt/vol) iodoacetamide, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, and 0.375 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8). For the separation of proteins in the second dimension, a 15% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel was used.

FIG. 6.

Western blot-based detection of CdtA and CdtC proteins bound to HeLa cells. After incubation with CdtA, CdtC, or a mixture of CdtA and CdtC, HeLa cells were washed and then solubilized as described in the text. (A) Western blot analysis using one-dimensional SDS-PAGE and the CdtC-reactive MAb 8C9. Lane 1, HeLa cells incubated with only CdtC; lane 2, HeLa cells incubated with both CdtA and CdtC; lane 3, purified CdtC (control). (B to E) Western blot analysis using two-dimensional SDS-PAGE and the CdtA-reactive MAb 1G8 (B and C) or the CdtC-reactive MAb 8C9 (D and E). (B) HeLa cells incubated with only CdtA; (C) HeLa cells incubated with both CdtA and CdtC; (D) HeLa cells incubated with only CdtC; (E) HeLa cells incubated with both CdtA and CdtC. Open arrow in panels A and E indicates CdtC; closed arrow in panel C indicates CdtA.

Using this methodology, CdtA was readily detectable, as a cluster of three immunoreactive spots, in the extract of the HeLa cells that had been incubated with the mixture of His-tagged CdtA and CdtC (Fig. 6C, closed arrow), but this same protein could not be detected in the extract of the HeLa cells that had been incubated with only His-tagged CdtA (Fig. 6B). We do not know the basis for the origin of these three immunoreactive species of CdtA; however, purified His-tagged CdtA alone exhibited a similar pattern of multiple immunoreactive spots in two-dimensional SDS-PAGE (data not shown). The HeLa cell antigen(s) that bound MAb 1G8 in Western blot analysis using one-dimensional SDS-PAGE (data not shown) was not apparent in this two-dimensional Western blot analysis; it is possible that this antigen(s) was either lost during the desalting step or not resolved by the isoelectric focusing step. Interestingly, when the same sample of HeLa cell lysate that was used in Fig. 6A, lane 2, was probed in this two-dimensional Western blot system with the CdtC-reactive MAb 8C9, the CdtC protein (Fig. 6E, open arrow) was observed to migrate with an apparent molecular weight that was much greater than that observed for the majority of the CdtC protein detected in Fig. 6A, lane 2. As expected, the sample from the HeLa cells incubated with only CdtC protein (Fig. 6A, lane 1) did not yield any MAb-reactive antigen when used in two-dimensional Western blot analysis (Fig. 6D). It should be noted that the aberrant migration characteristic of the CdtC protein seen in Fig. 6E is an artifact of sample processing, because the same result was obtained when purified CdtC protein was processed for two-dimensional SDS-PAGE (data not shown).

The results described above indicate that the CdtA-CdtC complex, once bound to HeLa cells, will prevent or delay killing of these cells by the CDT holotoxin. This same CdtA-CdtC complex will also facilitate killing of the HeLa cells when the CdtB protein is added to cells preincubated with this two-protein complex. These results are consistent with the hypothesis advanced by Lara-Tejero and Galan (14) in which the CdtA and CdtC proteins form a heterodimeric binding component in the CDT holotoxin which allows delivery of the enzymatically active CdtB protein to the eukaryotic cell. At this time, we cannot rule out the possibility that only one of these two proteins (i.e., CdtA or CdtC) in the CdtA-CdtC complex that is bound to the HeLa cells is actually the binding component of the CDT holotoxin and that the other protein is not functional in this regard. Alternatively, the preparation of the individual CdtA and CdtC proteins could have rendered either of these macromolecules incapable of binding to HeLa cells in the absence of the other protein. For example, the presence of the His tag in CdtA could have somehow interfered with binding of this protein by itself to the HeLa cells. Similarly, it is also possible that the renaturing of the purified His-tagged CdtA protein did not fully restore native function to this molecule or that the acid-based elution of CdtC from the immunoaffinity column adversely affected this latter protein. However, our inability to separate the CdtA-CdtC complex formed in vivo into its two component proteins has precluded testing of these possibilities to date.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI32011 to E.J.H.

We thank Leon Eidels for invaluable advice and discussions.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Akifusa, S., S. Poole, J. Lewthwaite, B. Henderson, and S. P. Nair. 2001. Recombinant Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans cytolethal distending toxin proteins are required to interact to inhibit human cell cycle progression and to stimulate human leukocyte cytokine synthesis. Infect. Immun. 69:5925-5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfa, M. J., P. Degagne, and P. A. Totten. 1996. Haemophilus ducreyi hemolysin acts as a contact cytotoxin and damages human foreskin fibroblasts in cell culture. Infect. Immun. 64:2349-2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aragon, V., K. Chao, and L. A. Dreyfus. 1997. Effect of cytolethal distending toxin on F-actin assembly and cell division in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Infect. Immun. 65:3774-3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cope, L. D., S. R. Lumbley, J. L. Latimer, J. Klesney-Tait, M. K. Stevens, L. S. Johnson, M. Purven, R. S. Munson, Jr., T. Lagergard, J. D. Radolf, and E. J. Hansen. 1997. A diffusible cytotoxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:4056-4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortes-Bratti, X., C. Karlsson, T. Lagergard, M. Thelestam, and T. Frisan. 2001. The Haemophilus ducreyi cytolethal distending toxin induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via the DNA damage checkpoint pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 276:5296-5302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng, K., J. L. Latimer, D. A. Lewis, and E. J. Hansen. 2001. Investigation of the interaction among the components of the cytolethal distending toxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 285:609-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elwell, C., K. Chao, K. Patel, and L. Dreyfus. 2001. Escherichia coli CdtB mediates cytolethal distending toxin cell cycle arrest. Infect. Immun. 69:3418-3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elwell, C. A., and L. A. Dreyfus. 2000. DNase I homologous residues in CdtB are critical for cytolethal distending toxin-mediated cell cycle arrest. Mol. Microbiol. 37:952-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frisk, A., M. Lebens, C. Johansson, H. Ahmed, L. Svensson, K. Ahlman, and T. Lagergard. 2001. The role of different protein components from the Haemophilus ducreyi cytolethal distending toxin in the generation of cell toxicity. Microb. Pathog. 30:313-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassane, D. C., R. B. Lee, M. D. Mendenhall, and C. L. Pickett. 2001. Cytolethal distending toxin demonstrates genotoxic activity in a yeast model. Infect. Immun. 69:5752-5759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson, W. M., and H. Lior. 1988. A new heat-labile cytolethal distending toxin (CLDT) produced by Campylobacter spp. Microb. Pathog. 4:115-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson, W. M., and H. Lior. 1988. A new heat-labile cytolethal distending toxin (CLDT) produced by Escherichia coli isolates from clinical material. Microb. Pathog. 4:103-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lara-Tejero, M., and J. E. Galan. 2000. A bacterial toxin that controls cell cycle progression as a deoxyribonuclease I-like protein. Science 290:354-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lara-Tejero, M., and J. E. Galan. 2001. CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC form a tripartite complex that is required for cytolethal distending toxin activity. Infect. Immun. 69:4358-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara-Tejero, M., and J. E. Galan. 2002. Cytolethal distending toxin: limited damage as a strategy to modulate cellular functions. Trends Microbiol. 10:147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis, D. A., M. K. Stevens, J. L. Latimer, C. K. Ward, K. Deng, R. Blick, S. R. Lumbley, C. A. Ison, and E. J. Hansen. 2001. Characterization of Haemophilus ducreyi cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC mutants in in vitro and in vivo systems. Infect. Immun. 69:5626-5634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mao, X., and J. M. DiRienzo. 2002. Functional studies of the recombinant subunits of a cytolethal distending holotoxin. Cell Microbiol. 4:245-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer, M. P. A., L. C. Bueno, E. J. Hansen, and J. M. DiRienzo. 1999. Identification of a cytolethal distending toxin gene locus and features of a virulence-associated region in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 67:1227-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer, K. L., W. E. Goldman, and R. S. Munson, Jr. 1996. An isogenic haemolysin-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi lacks the ability to produce cytopathic effects on human foreskin fibroblasts. Mol. Microbiol. 21:13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer, K. L., S. Grass, and R. S. Munson, Jr. 1994. Identification of a hemolytic activity elaborated by Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect. Immun. 62:3041-3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer, K. L., and R. S. Munson, Jr. 1995. Cloning and characterization of the genes encoding the haemolysin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Mol. Microbiol. 18:821-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickett, C. L., D. L. Cottle, E. C. Pesci, and G. Bikah. 1994. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin genes. Infect. Immun. 62:1046-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickett, C. L., E. C. Pesci, D. L. Cottle, G. Russell, A. N. Erdem, and H. Zeytin. 1996. Prevalence of cytolethal distending toxin production in Campylobacter jejuni and relatedness of Campylobacter sp. cdtB genes. Infect. Immun. 64:2070-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickett, C. L., and C. A. Whitehouse. 1999. The cytolethal distending toxin family. Trends Microbiol. 7:292-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purven, M., A. Frisk, I. Lonnroth, and T. Lagergard. 1997. Purification and identification of Haemophilus ducreyi cytotoxin by use of a neutralizing monoclonal antibody. Infect. Immun. 65:3496-3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purven, M., and T. Lagergard. 1992. Haemophilus ducreyi, a cytotoxin-producing bacterium. Infect. Immun. 60:1156-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saiki, K., K. Konishi, T. Gomi, T. Nishihara, and M. Yoshikawa. 2001. Reconstitution and purification of cytolethal distending toxin of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Microbiol. Immunol. 45:497-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott, D. A., and J. B. Kaper. 1994. Cloning and sequencing of the genes encoding Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin. Infect. Immun. 62:244-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sert, V., C. Cans, C. Tasca, L. Bret-Bennis, E. Oswald, B. Ducommun, and J. De Rycke. 1999. The bacterial cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) triggers a G2 cell cycle checkpoint in mammalian cells without preliminary induction of DNA strand breaks. Oncogene 18:6296-6304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shenker, B. J., R. H. Hoffmaster, T. L. McKay, and D. R. Demuth. 2000. Expression of the cytolethal distending toxin (Cdt) operon in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: evidence that the CdtB protein is responsible for G2 arrest of the cell cycle in human T cells. J. Immunol. 165:2612-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spinola, S. M., M. E. Bauer, and R. S. Munson, Jr. 2002. Immunopathogenesis of Haemophilus ducreyi infection (chancroid). Infect. Immun. 70:1667-1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevens, M. K., J. L. Latimer, S. R. Lumbley, C. K. Ward, L. D. Cope, T. Lagergard, and E. J. Hansen. 1999. Characterization of a Haemophilus ducreyi mutant deficient in expression of cytolethal distending toxin. Infect. Immun. 67:3900-3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trees, D. L., and S. A. Morse. 1995. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi: an update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:357-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]