Abstract

Coordination of mitotic exit with timely initiation of cytokinesis is critical to ensure completion of mitotic events before cell division. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae polo kinase Cdc5 functions in a pathway leading to the degradation of mitotic cyclin Clb2, thereby permitting mitotic exit. Here we provide evidence that Cdc5 also plays a role in regulating cytokinesis and that an intact polo-box, a conserved motif in the noncatalytic COOH-terminal domain of Cdc5, is required for this event. Depletion of Cdc5 function leads to an arrest in cytokinesis. Overexpression of the COOH-terminal domain of Cdc5 (cdc5ΔN), but not the corresponding polo-box mutant, resulted in connected cells. These cells shared cytoplasms with incomplete septa, and possessed aberrant septin ring structures. Provision of additional copies of endogenous CDC5 remedied this phenotype, suggesting a dominant-negative inhibition of cytokinesis. The polo-box–dependent interactions between Cdc5 and septins (Cdc11 and Cdc12) and genetic interactions between the dominant-negative cdc5ΔN and Cyk2/Hof1 or Myo1 suggest that direct interactions between cdc5ΔN and septins resulted in inhibition of Cyk2/Hof1- and Myo1-mediated cytokinetic pathways. Thus, we propose that Cdc5 may coordinate mitotic exit with cytokinesis by participating in both anaphase promoting complex activation and a polo-box–dependent cytokinetic pathway.

Keywords: Cdc5, polo-box, mitosis, cytokinesis, septin

Introduction

Members of the polo subfamily of protein kinases have been identified in various eucaryotic organisms. These kinases are known to play pivotal roles in cell division and proliferation. The polo subfamily members are characterized by the presence of a distinct region of homology in the COOH-terminal noncatalytic domain, termed the polo-box (Clay et al. 1993), which appears to be important for subcellular localization (Lee et al. 1998; Song et al. 2000). Studies in various organisms have shown that polo kinases regulate diverse cellular and biochemical events at multiple stages of M phase (for reviews, see Lane and Nigg 1997; Glover et al. 1998). These include centrosome maturation (Lane and Nigg 1996), bipolar spindle formation (Llamazares et al. 1991; Ohkura et al. 1995; Lane and Nigg 1996), and activation of anaphase promoting complex (APC) (Charles et al. 1998; Descombes and Nigg 1998; Kotani et al. 1998; Shirayama et al. 1998). In addition to these functions, a growing body of evidence suggests that polo kinases also play important roles in cytokinesis in various organisms (for reviews, see Fishkind and Wang 1995; Field et al. 1999).

Mammalian HeLa cells transfected with both wild-type and kinase-inactive Plk show an apparent cytokinetic defect with multiple nuclei, suggesting that overexpression of Plk interferes with cytokinesis in a manner independent of the kinase activity (Mundt et al. 1997). In Drosophila, a mutation in polo prevents the formation of a proper spindle midzone, and disturbs the relocalization of the cytokinetic motor protein Pav-KLP to the midzone, preventing contractile ring formation (Carmena et al. 1998). The interaction between Polo and Pav appears to be important in organizing the cytokinetic machinery (Adams et al. 1998). In fission yeast, the loss of plo1 + function results in a defect in F-actin ring formation and septal material deposition (Ohkura et al. 1995). Overexpression of Plo1 activates the pathway regulated by a small GTP-binding protein, Spg1, and induces multiple septa in any phase of the cell cycle (Ohkura et al. 1995; Mulvihill et al. 1999). In addition, Plo1 appears to regulate both the placement and organization of the medial contractile ring by directly interacting with Mid1, a contractile ring component required for the organization and positioning of the ring (Bahler et al. 1998).

In budding yeast, the cleavage plane is specified early in the cell cycle and cleavage is achieved by a concerted process of membrane constriction by an actomyosin-based contractile ring followed by septum formation (Bi et al. 1998; Lippincott and Li 1998b). Four septin proteins (Cdc3, Cdc10, Cdc11, and Cdc12) (for review, see Longtine et al. 1996) are the major structural components of the neck filaments (Frazier et al. 1998) encircling the mother-bud neck. Septin rings are thought to function as a scaffold for the recruitment of cytokinesis machinery to the mother-bud neck (for review, see Chant 1996). Before contraction, the septin ring disassembles and relocalizes to the future budding site (Longtine et al. 1996; Lippincott and Li 1998a). In addition to their role in cytokinesis (Bi et al. 1998; Lippincott and Li 1998a), septins also play a role in other cellular events such as chitin deposition (DeMarini et al. 1997), bud site selection (Chant et al. 1995), pheromone-induced morphogenesis (Giot and Konopka 1997), and septin-mediated Cdc28 activation pathway (Carroll et al. 1998; Barral et al. 1999; Edgington et al. 1999).

An actomyosin-based contractile ring forms in an ordered fashion in budding yeast (Epp and Chant 1997; Bi et al. 1998; Lippincott and Li 1998b). In a septin-dependent manner, Myo1 (Myosin II) assembles into a ring at the future budding site early in the cell cycle, whereas F-actin is recruited to the ring just before spindle disassembly and contraction (Bi et al. 1998; Lippincott and Li 1998a,Lippincott and Li 1998b). Besides actomyosins, additional components are also shown to play important roles in cytokinesis. Depletion of Cyk1 results in loss of actin accumulation at cytokinetic rings (Lippincott and Li 1998b; Osman and Cerione 1998), whereas its overexpression induces early induction of actin ring (Epp and Chant 1997), suggestive of its role in the recruitment of actin to the site of cell division. In addition, the Cyk2/Hof1 (hereafter referred to as Cyk2) ring appears to be important for the stability of the actomyosin ring during contraction and for the septum formation (Vallen et al. 2000). At the time of contraction, the Cyk2 ring becomes a single band and contracts, but regresses near the end of cytokinesis (Lippincott and Li 1998a).

In various organisms, it is widely appreciated that cytokinesis is preceded by inactivation of cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc2. In budding yeast, degradation of mitotic cyclins by the APC, thereby inactivating Cdc28 (functional homologue of Cdc2), is a prerequisite for cytokinesis, since cells overproducing mutant Clb2p lacking the destruction motif exhibit a mitotic exit defect with a telophase chromosome morphology (Surana et al. 1993). A growing body of evidence suggests that the budding yeast polo kinase, Cdc5, functions as a component of the mitotic exit network, which also includes a GTP-binding protein Tem1 (Shirayama et al. 1994) and protein kinases, Cdc15, Dbf2, and Dbf20 (Kitada et al. 1993; Shirayama et al. 1994; Jaspersen et al. 1998). Activation of this network is thought to liberate Cdc14 phosphatase from a Net1 complex in nucleolus, an event critical for activation of ubiquitin ligase activity of APC (Visintin et al. 1998, Visintin et al. 1999; Shou et al. 1999). Consistent with this notion, the cdc5-1 mutant at the restrictive temperature arrests at late mitosis with a high level of Clb2 due to a reduced APC activity, whereas overexpression of Cdc5 results in an increased APC activity (Charles et al. 1998; Jaspersen et al. 1998; Shirayama et al. 1998).

Although the role of Cdc5 in the mitotic exit pathway is well established, it is not known whether Cdc5 activity is required for cytokinesis. This could be largely due to the lack of additional cdc5 mutants that exhibit a cytokinetic defect without inhibiting mitotic exit. We have previously shown that, in addition to spindle poles, Cdc5 localizes at cytokinetic neck filaments (Song et al. 2000). The importance of the polo-box in cytokinesis has been suggested by the observation that overexpression of Cdc5 induces, and localizes to, additional nascent cytokinetic structures in a polo-box–dependent manner (Song et al. 2000).

In this study, we investigated whether or not Cdc5 has an important role in cytokinesis. We demonstrate that cells depleted of Cdc5 function arrest at multiple points of M phase, including an arrest in cytokinesis. Consistent with this observation, inhibition of Cdc5 function by overexpressing the COOH-terminal domain of Cdc5 (cdc5ΔN), but not the corresponding polo-box mutant, leads to a dominant-negative cytokinetic defect. Our data suggest that this defect is likely due to an inhibition of a direct interaction between endogenous Cdc5 and septins, Cdc11 and Cdc12, by the kinase activity–deficient cdc5ΔN. Remarkably, these cells appear to proceed through the cell cycle efficiently, as evidenced by cycling Cdc28/Clb2 activity, suggesting that an intact polo-box is critical for selective inhibition of cytokinesis without disturbing mitotic exit. Our data suggest that the polo-box–dependent localization of Cdc5 at cytokinetic neck filaments likely provides the temporal and spatial regulation of Cdc5, which may be important in coordinating the completion of mitosis with the initiation of cytokinesis.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Construction

All plasmids and yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table . To generate a GAL1-cdc5-1 construct, a PCR-amplified cdc5-1 allele from strain KKY921-2BY was digested with PpuMI and BstEII to generate pSK877 (Song et al. 2000). A Plk-expressing integration construct was generated by inserting a SpeI-SphI fragment of GAL1-HA-EGFP-Plk from YCplac111-GAL1-HA-EGFP-Plk (Lee et al. 1998) into a pUC19-TRP1 vector to yield pSK1267.

Table 1.

Yeast Strains and Plasmids Used in this Study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1783 | MATa leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 trp1-1 his4 can1r (isogenic of EG123) | I. Herskowitz, UCSF |

| KKY921-2B | MATa cdc5-1 leu2 trp1 ura1 | Kitada et al. 1993 |

| KKY902 | MATa/α leu2-3, 112 trp1-289 ura3-52 HIS7/his7-1 CAN1/can1 CDC5/cdc5Δ::LEU2 | Kitada et al. 1993 |

| KLY969 | MATa leu2 trp1 ura3 (a segregant of KKY902) | This work |

| KLY1046 | as KKY921-2B except cdc5Δ::KanMX6 TUB1-GFP::LEU2 GAL1-HA-EGFP-PLK::TRP1 | This work |

| KLY1047 | as KKY969 except cdc5Δ::KanMX6 TUB1-GFP::LEU2 [YCplac22-GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5-1] | This work |

| KLY1053 | as 1783 except GAL1-HA-GST-CDC5ΔN::URA3 | This work |

| KLY1069 | as 1783 except GAL1-HA-GST-CDC5ΔN::URA3 TUB1-GFP::LEU2 | This work |

| KLY1071 | as 1783 except GAL1-HA-GST-CDC5ΔN::URA3 CYK2-GFP::LEU2 | This work |

| KLY1073 | as 1783 except GAL1-HA-GST-CDC5ΔN::URA3 MYO1-GFP::LEU2 | This work |

| KLY1075 | as 1783 except GAL1-HA-GST-CDC5ΔN::URA3 YFP-CDC3::LEU2 | This work |

| KLY1080 | as 1783 except GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)::URA3 | This work |

| KLY1081 | as 1783 except GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5ΔN::URA3 | This work |

| KLY1082 | as 1783 except GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5ΔN/FAA::URA3 | This work |

| KLY1083 | as 1783 except 3X[GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5ΔN::URA3] | This work |

| KLY1229 | as 1783 except GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5ΔN/FAA::URA3 2X[GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5ΔN/FAA::TRP1] | This work |

| KLY1253 | as KKY921-2B except TUB1-GFP::LEU2 | This work |

| KLY1256 | as KKY921-2B except CYK2-GFP::LEU2 | This work |

| KLY1258 | as KKY921-2B except MYO1-GFP::LEU2 | This work |

| KLY1260 | as KKY921-2B except YFP-CDC3::LEU2 | This work |

| KLY1439 | as KLY1083 except swe1Δ::LEU2 | This work |

| KLY1589 | as KLY1083 except cdc10Δ::KanMX6 | This work |

| KLY1590 | as KLY1083 except cdc10Δ::KanMX6 | This work |

| KLY1591 | as KLY1083 except cyk2Δ::KanMX6 | This work |

| KLY1593 | as KLY1083 except myo1Δ::KanMX6 | This work |

| SKY1732 | as KLY1083 except CDC11-9myc | This work |

| SKY1734 | as KLY1229 except CDC11-9myc | This work |

| SKY1779 | as KLY1083 except GAL-SIC1 | This work |

| pSWE1-10g | pUC1180swe1Δ::LEU2 | Booher et al. 1993 |

| pSK615 | YCplac111-CDC5 | Song et al. 2000 |

| pSK772 | YCplac111-cdc5(N209A) | Song et al. 2000 |

| pSK785 | YCplac111-cdc5(W517F/V518A/L530A) | Song et al. 2000 |

| pSK856 | pUC19-GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5ΔN/FAA::TRP1 | This work |

| pSK877 | YCplac22-GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5-1(P511L) | This work |

| pSK983 | pUC19-GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5ΔN::URA3 | This work |

| pSK984 | pUC19-GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5ΔN/FAA::URA3 | This work |

| pSK986 | pUC19-GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)::URA3 | This work |

| pSK1041 | pUC19-GAL1-HA-GST-cdc5ΔN:URA3 | This work |

| pSK1050 | pUC19-TUB1-GFP::LEU2 | Derived from pAFS125 (Straight et al. 1997) |

| pSK1051 | pUC19-CYK2-GFP::LEU2 | Derived from pLP2 (Lippincott and Li 1998b) |

| pSK1052 | pUC19-MYO1-GFP::LEU2 | Derived from pLP8 (Lippincott and Li 1998a) |

| pSK1059 | pUC19-YFP-CDC3::LEU2 | This work |

| pSK1267 | pUC19-GAL-HA-EGFP-PLK::TRP1 | This work |

| pSK1330 | pUC19-cyk2Δ::KanMX6 | This work |

| pSK1332 | pUC19-cdc10Δ::KanMX6 | This work |

| pSK1348 | pUC19-myo1Δ::KanMX6 | This work |

| pSK1366 | pJG4-5-CDC3 | This work |

| pSK1367 | pJG4-5-CDC10 | This work |

| pSK1368 | pJG4-5-CDC11 | This work |

| pSK1369 | pJG4-5-CDC12 | This work |

| pSK1390 | pEG202-NLS-CDC5ΔN | This work |

| pSK1405 | pEG202-NLS-CDC5 | This work |

| pSK1407 | pEG202-NLS-CDC5ΔN/FAA | This work |

| pSK1408 | pEG202-NLS-CDC5ΔC | This work |

| pSK1996 | pRS305-GAL-SIC1 | Derived from pRDB608 |

To visualize the subcellular structures of spindle, septin, or contractile rings, green fluorescent protein (GFP)–tagged TUB1, CYK2, MYO1, or CDC3 constructs were integrated into the genome. To generate pUC19-TUB1-GFP::LEU2 (pSK1050) and pUC19-CYK2-GFP::LEU2 (pSK1051), KpnI-NotI fragments containing either TUB1-GFP (from pAFS125; a gift of Aaron F. Straight, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) or CYK2-GFP (from pLP2; a gift of Rong Li, Harvard Medical School) were inserted into YCplac111 vector digested with BglII and KpnI. The resulting constructs lack both ARS and CEN loci, but bear pUC19 backbone and LEU2 gene. pUC19-MYO1-GFP::LEU2 (pSK1052) was generated by inserting a PstI-NotI fragment of MYO1-GFP (from pLP8; a gift of Rong Li) into the PstI-BglII fragment of YCplac111 lacking both ARS and CEN loci. pUC19-YFP-CDC3::LEU2 (pSK1059) was created by inserting the SstI-SphI fragment of CDC3 tagged NH2 terminally with YFP (a yellow-green variant of GFP; CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) into a pUC19-LEU2 construct.

Gene disruption constructs for CYK2 (pSK1330), CDC10 (pSK1332), and MYO1 (pSK1348) were generated by inserting a 1.5-kb BglII-PmeI fragment of KanMX6 from pFA6a-13Myc-KanMX6 (Longtine et al. 1998) into the open reading frame of the corresponding genes in pLP1 (CYK2-Myc, a gift of Rong Li), pSK1060 (YFP-CDC10), or pSK1052 (MYO1-GFP), respectively.

Several dominant-negative cdc5ΔN constructs were used to inhibit the function of endogenous Cdc5. A fragment of GAL1-2X(EGFP)-cdc5ΔN or its FAA mutant (Song et al. 2000) was inserted into a pUC19-URA3 plasmid to generate pSK983 or pSK984, respectively. To generate a GST-tagged cdc5ΔN, a 0.75-kb SalI-XhoI fragment containing GST open reading frame was PCR amplified using pGEX-KG (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as a template. This fragment was inserted into pSK983 digested with XhoI digestion to replace GFP coding sequence.

To construct plasmids for two-hybrid analyses, CDC3, CDC10, CDC11, and CDC12 were PCR-amplified using genomic clones (gifts of John Chant, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA) as templates. The EcoRI-XhoI (artificially introduced restriction enzyme sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of each open reading frame) fragments were ligated into pJG4-5 plasmid digested with corresponding enzymes. This results in in-frame fusion of full-length septins to activation domain. To generate a LexA DNA binding domain–fused CDC5 construct, a 2-kb XbaI fragment from pSK1006 was inserted into EcoRI-digested, end-filled pEG202-NLS (Origene Technologies Inc.). Various forms of CDC5 mutants were constructed by PCR amplification or enzymatic deletion (see Table and Fig. 6 C). To construct LEU2-based GAL-SIC1 plasmid, pRDB608 (a gift of Raymond Deshaies, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA) was digested with NaeI and AatII to swap a URA3 fragment for a LEU2 fragment of pRS305. The resulting pSK1996 was digested with BstXI to achieve a targeted integration of GAL-SIC1 at the LEU2 locus.

Figure 6.

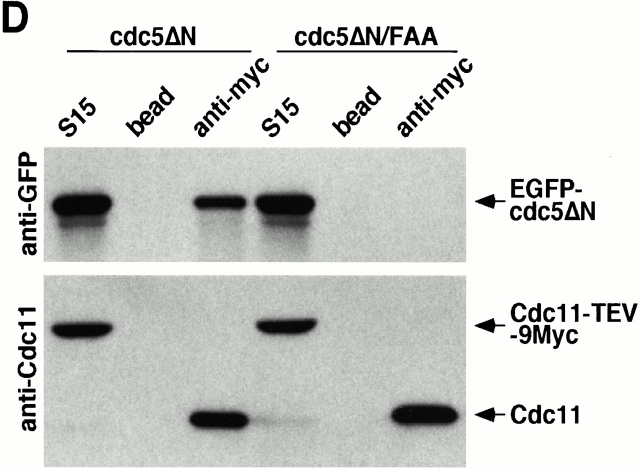

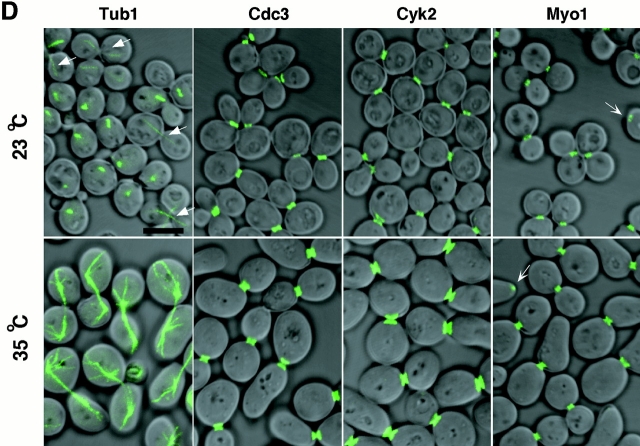

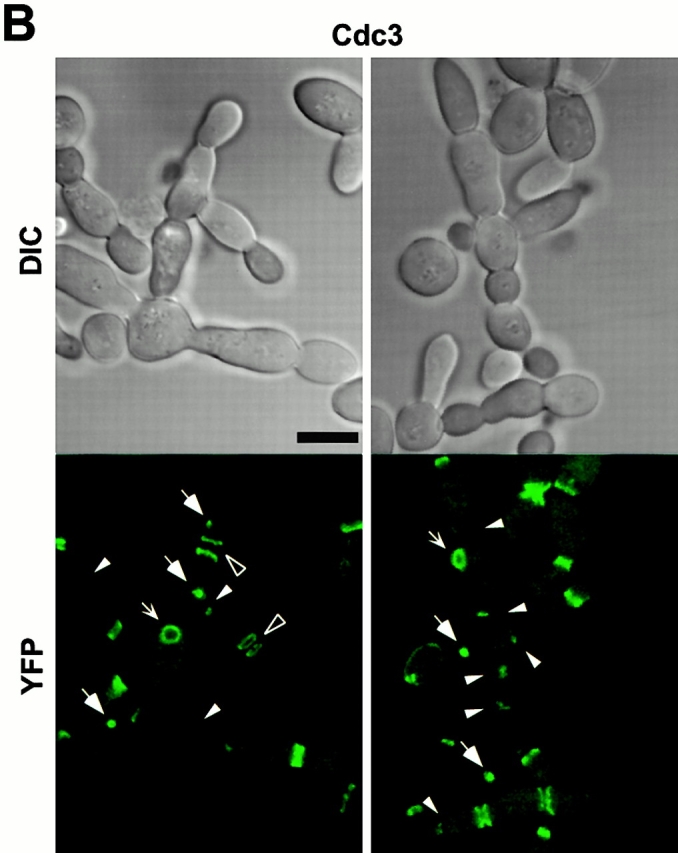

Direct interactions between cdc5ΔN and septins may lead to aberrant septin ring structures. Strain 1783 expressing a GST-cdc5ΔN under control of GAL1 promoter (KLY1053) were additionally integrated with TUB1-GFP (KLY1069), YFP-CDC3 (KLY1075), CYK2-GFP (KLY1071), or MYO1-GFP (KLY1073). These cells were cultured under the induction conditions for 12 h and subjected to microscopic examination. (A) Overexpression of GST-cdc5ΔN induces an apparent G1 arrest. Internal cell bodies possess disassembled spindles, whereas peripheral cell bodies possess elongated spindles, suggesting that only the cells at the edge continue to divide (see text). Bar: 5 μm. (B) Induction of various aberrant septin structures by overexpression of GST-cdc5ΔN. It appeared that a large fraction of septin double rings (visualized as YFP-Cdc3) were distantly placed from each other (open arrowheads) or that septin rings were disassembled with remnants of the YFP-Cdc3 signal present at the mother-bud neck (arrowheads). In addition, tiny septin ring structures (arrows) or abnormally large rings (barbed arrows) without an apparent bud formation were often present (see text for detail). Bar: 5 μm. (C) Two-hybrid interactions between Cdc5 and septins. Diagram shows structures of various Cdc5 constructs used in these analyses. To enhance the protein stability, a destruction-box–deficient form of Cdc5 (Song et al. 2000) was used in place of the wild-type Cdc5. Grey boxes indicate the kinase domain in the NH2 terminus of Cdc5. Closed boxes in the COOH-terminal domain indicate the polo-box, whereas the gray indicates the polo-box with FAA mutations. The numbers in the table indicate the Miller units of β-galactosidase activity averaged from two independent experiments. Cl, Cla I; RV, Eco RV; Sn, Sna BI; Cdc5, Cdc5 lacking the NH2-terminal residues 6–71 (Song et al. 2000); cdc5ΔC, COOH-terminal domain deletion; cdc5ΔN, NH2-terminal domain deletion; cdc5ΔN/FAA, NH2-terminal domain deletion with FAA mutations in the polo-box; a and b, control plasmids: pEG202-NLS (DNA binding domain fusion vector) and pJG4-5 (activation domain fusion vector). (D) Coimmunoprecipitation of cdc5ΔN with Cdc11. To examine in vivo interactions between cdc5ΔN and septins, cellular lysates (supernatant of 15,000 g; S15) were prepared from strains bearing CDC11-TEV-9myc at the CDC11 locus and expressing either GAL1-EGFP-cdc5ΔN (SKY1732) or GAL1-EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (SKY1734). Cdc11 was immunoprecipitated with an anti–Myc antibody cross linked to sepharose beads. To elute Cdc11 and its associated proteins, immunoprecipitates were digested with TEV protease. The resulting eluates were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses with either anti–GFP antibody or anti–Cdc11 antibody. To determine the efficiency of coprecipitation, a fraction of S15 before immunoprecipitation was also loaded. Due to the TEV cleavage, Cdc11 protein eluted from immunoprecipitates possesses a molecular size smaller than Cdc11-TEV-9Myc. cdc5ΔN, S15 lysates from SKY1732; cdc5ΔN/FAA, S15 lysates from SKY1734, S15, a fraction of S15 lysates; bead, anti–Flag antibody crossed linked to sepharose beads; anti–Myc, anti–Myc antibody crossed linked to sepharose.

Strain Construction

All strains constructed in this study were confirmed by PCR or Southern hybridization (data not shown). A cdc5Δ::KanMX6 mutation was introduced into strain 1783 harboring either pSK877(GAL1-cdc5-1) or pSK1267(GAL1-Plk) by a one-step gene disruption method described previously (Longtine et al. 1998). Overexpression of cdc5ΔN under GAL1 promoter control was achieved by the integrating pSK983, pSK984, or pSK1041 into strain 1783 at the URA3 locus.

Strain KLY1229 was generated by integrating two additional copies of GAL1-HA-2X(EGFP)-cdc5ΔN/FAA::TRP1 (pSK929) into strain KLY1081. To generate a swe1Δ strain (KLY1439), a 2.3-kb XbaI fragment from pSWE1-10g (Booher et al. 1993) was transformed into strain KLY1083. To disrupt CYK2, a 2-kb BamHI fragment from pSK1330 that contains the KanMX6 and flanking CYK2 sequences was transformed into strain KLY1083. To generate cdc10Δ and myo1Δ strains, 1.8- and 2-kb BamHI-SphI fragments from pSK1332 and pSK1348, respectively, were introduced into KLY1083 to yield KLY1589 and KLY1593, respectively.

To generate strains SKY1732 and SKY1734, the CDC11 locus in KLY1083 and KLY1229 strains, respectively, were COOH-terminally tagged with 9myc epitope that is bridged with a TEV protease (GIBCO BRL) cleavage site. To generate strain SKY1779 expressing GAL-SIC1, pSK1996 was digested with BstXI and integrated into the LEU2 locus in strain KLY1083.

Growth Conditions, Media, and Zymolyase Treatment

Yeast cell cultures and transformations were carried out by standard methods (Sherman et al. 1986). For cell cycle synchronization, MAT a cells were arrested with 5 μg/ml α-factor mating pheromone (Sigma-Aldrich). Treatment of the connected cells with zymolyase was performed as described previously (Frazier et al. 1998; Lippincott and Li 1998b). Loss of the refractile appearance was evident under the microscope, indicating that cell wall removal was efficient under these conditions.

Immunoprecipitation, Kinase Assays, and Western Analyses

Cell lysates were prepared in TED buffer (40 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 0.25 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM AEBSF) (Pefabloc; Boehringer), 10 μM/ml pepstatin A, 10 μM/ml leupeptin, and 10 μM/ml aprotinin) with an equal volume of glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich). To measure Clb2-associated Cdc28 kinase activity, the obtained lysates were spun at 15,000 g for 10 min, and the resulting supernatants were subjected to immune complex kinase assays using an anti–Clb2 antibody (a gift of David Morgan, University of California, San Francisco, CA) as described previously (Jaspersen et al. 1998). Western analyses were carried out with an anti–GFP antibody (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.), anti–Cdc28 antibody (a gift of Raymond Deshaies, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA), anti–Clb2 antibody, anti–Cdc11 antibody (a gift of Erica S. Johnson, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA), and anti–hemagglutinin (anti–HA) antibody as described previously (Tinker-Kulberg and Morgan 1999; Song et al. 2000). Proteins that interact with antibodies were detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence Western detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The blots were scanned and quantitated using Molecular Dynamics ImageQuant program.

To examine in vivo interactions between cdc5ΔN and septins, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were carried out using strains bearing CDC11-TEV-9myc at the CDC11 locus and expressing either GAL1-EGFP-cdc5ΔN (SKY1732) or GAL1-EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (SKY1734). An anti–Myc antibody cross linked to sepharose beads (BabCO) was used to precipitate Cdc11-TEV-9Myc. Immunoprecipitates were digested with TEV protease (GIBCO-BRL) according to the manufacturer's instruction, and the resulting supernatants were subjected to further analyses.

Cell Staining and Immunofluorescence Microscopy

To visualize plasma membranes, cells were stained with DiI (Molecular Probes) as described previously (Lippincott and Li 1998a). To determine whether septums are formed between the cell bodies, calcofluor staining was carried out as previously described (Pringle 1991; Lippincott and Li 1998a) with a fluorescent brightener 28 (Sigma-Aldrich), and then serial sections were obtained using a confocal microscope with 0.1-μm interval.

Indirect immunofluorescence was performed as described previously (Lee et al. 1998). In brief, cells cultured under induction conditions for the indicated time were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde. Actin was localized using rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probes). DNA was visualized with DAPI. Confocal fluorescent images were collected with a confocal scan head (MRC 1024; Bio-Rad Laboratories) mounted on a Nikon Optiphot microscope with a 60× planapochromat lens or with a Leica TCS spectrophotometer confocal microscope.

Two-Hybrid Analyses

Two-hybrid analyses were performed using a system described by Gyuris et al. 1993. Full-length CDC3, CDC10, CDC11, and CDC12 were fused to transcriptional activation domain in pJG-5, whereas various forms of CDC5 were fused to DNA binding domain in pEG202-NLS (Origene Technologies, Inc.). These constructs were cotransformed with a reporter plasmid pSH18-34 into yeast strains EGY48 and EGY194, respectively. After combinatorial matings, duplicate samples of each combination were subjected to quantitative β-galactosidase assays.

Results

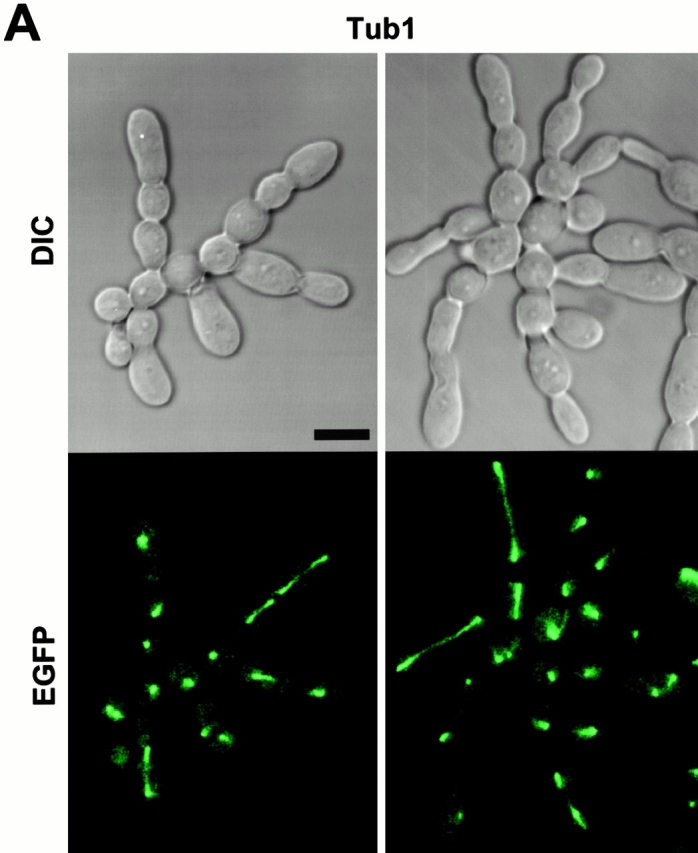

Loss of CDC5 Function Results in Arrests in Multiple Points of M Phase

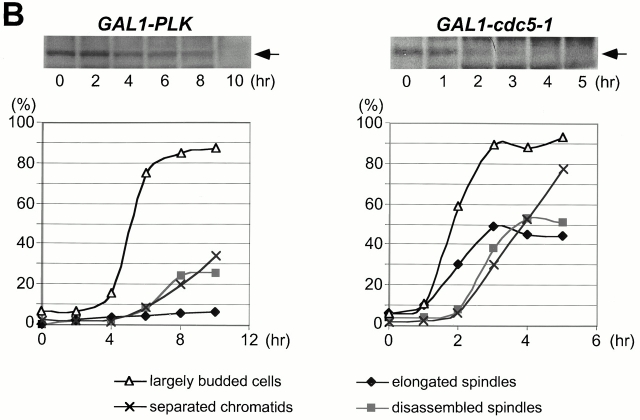

Although it has been shown that polo kinases play important roles in multiple stages of M phase in various eucaryotic organisms, it has not been clear whether budding yeast polo kinase Cdc5 has a role other than in the mitotic exit pathway. To address this issue, we investigated the terminal morphology of a cdc5Δ mutant. Since overexpression of Cdc5 inhibits cell growth (Kitada et al. 1993) and induces abnormal bud elongation (Song et al. 2000), cdc5Δ strains were generated that were kept viable by expressing either its murine functional homologue Plk (KLY1046) or the less-stable cdc5-1–encoded protein (Cheng et al. 1998) (KLY1047) under control of the GAL1 promoter. To reveal arrest phenotypes relating to dynamic spindle structures in mitosis, these strains possess an integrated copy of a GFP-fused TUB1 (Tub1-GFP) under control of its own promoter. Provision of a single copy of endogenous CDC5 into these strains complemented the growth defect associated with the cdc5Δ mutation (data not shown). Both strains grow well on YEP-galactose medium, but are unable to grow on YEP-glucose (Fig. 1 A). When exponentially growing cells were transferred to YEP-glucose medium, Plk was undetectable after 10 h, whereas the cdc5-1 protein disappeared after 3–4 h (Fig. 1 B). The fast removal of cdc5-1 protein, in comparison with Plk, may be due to the presence of two putative destruction boxes in the NH2-terminal sequence of Cdc5 (Shirayama et al. 1998). Consistent with the protein removal kinetics, large-budded cells become abundant ∼6 h after depletion of Plk or 3 h after depletion of cdc5-1. As with cells with separated chromatids, cells with disassembled spindles increased and reached plateau in 8 h for KLY1046 or 4 h for KLY1047 (Fig. 1 B). To determine the percentage of cells arrested at various phases of the cell cycle, both strains were depleted of the Plk or cdc5-1 proteins for 8 or 4 h, respectively, and counted using spindle structures as a cell-cycle marker. We observed that 65% of strain KLY1046 arrested at early anaphase with a short spindle elongated to, or extended just beyond, the mother-bud neck, whereas 25% of the population were arrested at cytokinesis with disassembled spindles (Fig. 1 C). In the case of strain KLY1047, 53% of the cells were arrested in cytokinesis, whereas 3 and 44% of the cell population were arrested at early anaphase and late anaphase/telophase, respectively (Fig. 1 C). The complete absence of unbudded (G1) cells suggests that cells were arrested in terminal phenotypes under these conditions. In contrast, consistent with a late mitosis arrest as reported previously (Kitada et al. 1993; Toczyski et al. 1997), the cdc5-1 mutant arrested homogeneously with elongated spindles (93% of the population) when cultured at 35°C for 3.5 h (Fig. 1 C). Since the contraction of cytokinetic rings occurs at the time of spindle breakdown (Lippincott and Li 1998a), a large population of cdc5Δ cells with disassembled spindles in both strain KLY1046 and strain KLY1047 suggests that Cdc5 activity is required at a step in cytokinesis. In addition, our data suggest that Cdc5 function is required at multiple points of M phase, including cytokinesis.

Figure 1.

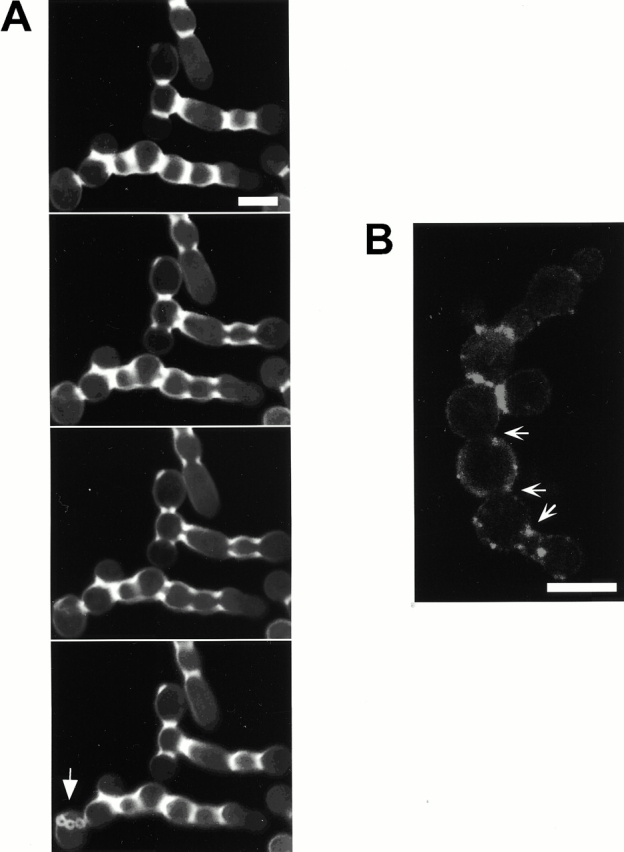

Cells depleted of Plk or cdc5-1 protein arrest at multiple points of M phase. (A) Growth of cdc5Δ mutant conditionally rescued by expressing either GAL1-HA-EGFP-PLK (KLY1046) or GAL1-HA-EGFP-cdc5-1 (KLY1047). Strains were streaked onto either YEP-galactose or YEP-glucose, and incubated for 3 d at 30°C. As a comparison, an isogenic wild-type strain, 1783, was also streaked. Wild-type, 1783 strain; GAL1-PLK, strain KLY1046;GAL1-cdc5-1, strain KLY1047. (B) Depletion of Plk or cdc5-1 protein revealed a large fraction of large-budded cells with disassembled spindles. Strains KLY1046 and KLY1047 growing exponentially in YEP-galactose medium were transferred into YEP-glucose to deplete Plk and cdc5-1 proteins. Upon transfer, samples were taken to analyze the levels of HA-EGFP-Plk and HA-EGFP-cdc5-1 proteins using an anti–HA antibody. Due to an apparent cell lysis phenotype after a prolonged incubation at the restricted temperature, cells were not taken beyond the last indicated time point. At the indicated time points, cells were harvested to determine chromosomal structures with DAPI staining. The same samples were used to examine spindle structures by GFP-tubulin fluorescent signals. Strain KLY1047, but not KLY1046, has accumulated a significant number of cells with elongated spindles (see text). (C) Terminal phenotypes of cdc5Δ or cdc5-1 cells. To determine terminal arresting phenotypes associated with depletion of Plk or cdc5-1 protein, strain KLY1046 was depleted of Plk for 10 h, whereas KLY1047 cells were depleted of cdc5-1 protein for 4 h. Cells arrested at different phases of the cell cycle were scored based on the spindle morphologies. Numbers shown are the average of two independent experiments. (D) Terminal morphology of the cdc5-1 mutant expressing TUB1-GFP (KLY1253), YFP-CDC3 (KLY 1260), CYK2-GFP (KLY1256), or MYO1-GFP (KLY1258). The cdc5-1 cells growing exponentially at 23°C were shifted to 35°C and cultured for an additional 3.5 h. Cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and harvested to examine the terminal arrest phenotype. The cdc5-1 mutant arrests as large-budded cells with two Cyk2-GFP rings and elongated spindles. Arrows in Tub1 indicate weakly visible elongated spindles, whereas the barbed arrows in Myo1 indicate Myo1-GFP localized at the future budding site. Bar: 5 μm.

The differences observed between cdc5-1 and Plk depletion may reflect the different capacity of these two proteins to replace the function of Cdc5. In addition, the relatively high percentage of cells arrested with elongated spindles in strain KLY1047 (44%), in comparison with that seen with KLY1046 (8%) (Fig. 1 C), may be attributable to the specific defect of the cdc5-1 allele at this stage of the cell cycle. It is noteworthy that the population exhibiting a cytokinetic arrest is likely underrepresented, since cells escaping earlier arrests can only achieve arrests at later points.

To closely compare the cdc5Δ phenotype with that of the cdc5-1 mutation, TUB1-GFP, CDC3-YFP, CYK2-GFP, and MYO1-GFP constructs were integrated into the cdc5-1 mutant strain. When these cells cultured at 35°C for 3.5 h, they exhibited homogeneous arrest at late anaphase/telophase, as indicated by elongated spindles (Fig. 1 D). In addition, Cdc3 was present as double rings at the mother-bud neck, before relocalization to the future budding sites. The Cyk2 ring was never seen as a single ring in these cells and the Myo1 ring appears to maintain normal size before contraction (Fig. 1 D). Since the Cyk2 double ring merges to a single ring after the completion of spindle elongation and the contraction of the Cyk2 ring follows during spindle breakdown (Lippincott and Li 1998a), our data suggest that these cells arrested at a point before contraction (∼10–15 min in the cell cycle between double Cyk2 ring stage with incompletely elongated spindle and initiation of contraction; see Lippincott and Li 1998a). Consistent with these observations, close examination revealed that spindles in these cells were not yet fully elongated (Fig. 1 D). These data indicate that, in contrast to the large fraction of cdc5Δ cells arrested in cytokinesis, the cdc5-1 mutant arrests in late mitosis at a step before the initiation of cytokinesis.

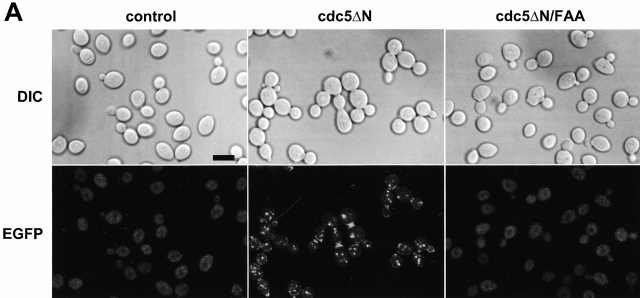

Induction of Connected Cells by Overexpression of the COOH-terminal Domain of Cdc5, but Not the corresponding Polo-Box Mutant

We have previously shown that Cdc5 localizes at spindle poles and cytokinetic neck-filaments (Song et al. 2000). The noncatalytic COOH-terminal domain of Cdc5, which contains the polo-box, is sufficient to localize at both mother-bud neck and spindle poles, whereas introduction of a triple W517F/V518A/L530A mutation (referred as FAA hereafter) in the polo-box abolishes localization (Song et al. 2000). In addition, overexpression of Cdc5, but not the FAA polo-box mutant, can induce ectopic septin ring structures in abnormally elongated buds (Song et al. 2000). These data suggest that the polo-box is critical in the localization and cytokinetic function of Cdc5. Thus, we attempted to inhibit the polo-box function by overexpression of the COOH-terminal domain of Cdc5 (cdc5ΔN). To this end, strain 1783 was integrated with a single copy of GAL1-EGFP, GAL1-EGFP-cdc5ΔN, or GAL1-EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA. These cells grow normally without any detectable morphological defect on YEP-glucose (data not shown). However, when grown in YEP-galactose, expression of EGFP-cdc5ΔN (KLY1082) resulted in connected cells. In contrast, cells expressing either control EGFP (KLY1080) or EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (KLY1081) did not yield any detectable morphological changes (Fig. 2 A, top). Microscopic examinations revealed that cells expressing cdc5ΔN yield two fluorescent bands at the mother-bud neck and fluorescent dots in the cytoplasm, whereas the EGFP control and the corresponding FAA mutant yielded only diffuse signals (Fig. 2 A, bottom). The apparent multiple dot signals in strain KLY1082 may be in part attributable to the ability of cdc5ΔN to induce multiple subcellular structures containing Spc42, a component of spindle pole bodies (Song et al. 2000). However, strains KLY1082 and KLY1083 (a strain expressing three copies of EGFP-cdc5ΔN; described below) do not possess any detectable growth defect in the presence of the antimicrotubule drug benomyl (data not shown), suggesting that these strains grow without a significant defect in the spindle checkpoint pathway. Both EGFP-cdc5ΔN and EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA were expressed at similar levels, indicating that the observed phenotype associated with EGFP-cdc5ΔN expression was not due to a difference in protein abundance (Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2.

Overexpression of cdc5ΔN, but not the FAA polo-box mutant (Song et al. 2000), induces a dominant-negative, connected cell morphology. (A) 1,783 (MAT a EG123) cells overexpressing either control EGFP (KLY1080), EGFP-cdc5ΔN (KLY1082), or EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (KLY1081) were cultured under the induction conditions for 12 h. Cells were fixed and examined using confocal microscopy. A similar chained cell phenotype was also observed in a W303-1A and S288C genetic background (data not shown). DIC, differential interference contrast; EGFP, EGFP-fusion proteins expressed; control, strain KLY1080; cdc5ΔN, strain KLY1082; cdc5ΔN/FAA, strain KLY1081. Bar: 5 μm. (B) The FAA mutations in the polo-box do not influence the level of cdc5ΔN expression. An equal amount (30 μg) of cell lysate prepared from various strains shown in A was loaded onto each lane. Control, strain 1080; cdc5ΔN, strain 1082; cdc5ΔN/FAA, strain 1081; EGFP-cdc5ΔN, EGFP-fused cdc5ΔN proteins expressed; EGFP, control EGFP lacking Cdc5. Cdc28 protein serves as a loading control for each lane. (C) Introduction of wild-type CDC5 in a low copy centromeric plasmid, but not the cdc5/FAA or the kinase-inactive cdc5/NA (Hardy and Pautz 1996), remedy the chained cell morphology induced by overexpression of cdc5ΔN. Strain KLY1082 transformed with various CDC5 constructs were cultured in YEP-glucose to exponential phase before morphological examination. Vector, YCplac111 vector; CDC5, YCplac111-CDC5; cdc5/FAA, YCplac111-cdc5/W517F/V518A/L530A; cdc5/NA, YCplac111-cdc5/N209A. (D) Quantitation of the reversion of connected cell phenotype by various CDC5 constructs. The same samples shown in C were also counted. Both the kinase activity and an intact polo-box appear to be required for reversing the chained cell morphology.

The Connected Cell Phenotype Is the Result of a Dominant-Negative Function of cdc5ΔN

The observed chained cell phenotype led us to speculate that overexpression of the kinase-activity–deficient COOH-terminal domain (cdc5ΔN) may have resulted in a dominant-negative inhibition of a cytokinetic event that is regulated by endogenous Cdc5. Thus, we examined whether provision of endogenous CDC5 in a low copy centromeric plasmid could alleviate the apparent chained cell phenotype. Cells expressing EGFP-cdc5ΔN under the control of GAL1 promoter (KLY1082) were transformed with wild-type and various mutant forms of Cdc5. When cultured under induction conditions for 12 h, KLY1082 cells transformed with control vector showed typical connected cell morphology in 48% of the total population (Fig. 2 C). In contrast, provision of wild-type CDC5 into strain KLY1082 efficiently restored this phenotype to a wild-type morphology. However, neither the polo-box mutated cdc5/FAA nor the kinase-inactive cdc5/NA (the N209A mutation that inactivates Cdc5 kinase activity; Hardy and Pautz 1996) were capable of alleviating this defect (Fig. 2C and Fig. D). These data indicate that the observed phenotype of EGFP-cdc5ΔN overexpression is due specifically to the inhibition of endogenous Cdc5 function, and both the kinase activity and the intact polo-box are required to remedy this phenotype. Thus, it appears that the observed connected cell phenotype is the result of dominant-negative inhibition of endogenous Cdc5 function important for normal cell division. In addition, cells possessing three copies of EGFP-cdc5ΔN (KLY1083) exhibited a uniformly connected cell morphology in almost all cells, whereas cells expressing the same three copies of EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (KLY1229) did not (see below). Provision of multiple copies of CDC5 into strain KLY1083 alleviated the chained cell morphology (data not shown). Thus, these cells were used for further characterization of the chained cell phenotype.

Inhibition of Cytokinesis by a Dominant-Negative COOH-Terminal Domain of Cdc5

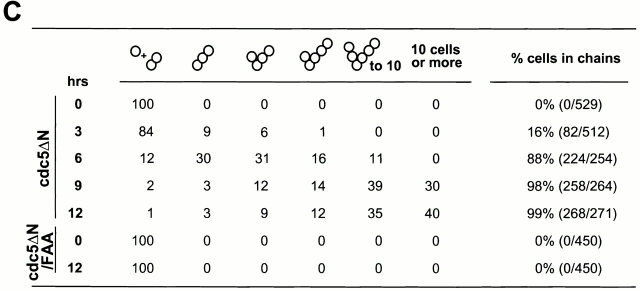

To examine the phenotype associated with the overexpression of EGFP-cdc5ΔN, strain KLY1083 was cultured under induction conditions in YEP-galactose. Control strains expressing either EGFP alone (KLY1080) or an equal dosage of EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (KLY1229) were grown under the same conditions. When induced, KLY 1083 cells yielded a connected cell phenotype in a time-dependent manner, whereas cells expressing the corresponding FAA mutant appear to divide normally with wild-type morphology (Fig. 3A and Fig. B). Upon inducing for 9 h, 98% of the population exhibited this phenotype, and 30% of them possess >10 connected cell bodies. In contrast, cells expressing the FAA mutant did not show this morphology (Fig. 3 C). In addition, the cell number of strain KLY1083 (when counting the connected cells as one cell) did not increase after shifting to the induction conditions (Fig. 3 D), indicating that cells remained unseparated. However, these cells continued to grow, although slowly, as indicated by an increase in optical density of the cell culture. Under the same conditions, cells expressing either control EGFP (KLY1080) or EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (KLY1229) exhibited a normal increase in both cell number and optical density (Fig. 3 D). Western analyses revealed that both EGFP-cdc5ΔN and EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA were expressed at similar levels, and that they were slightly more abundant than that of a single copy EGFP-cdc5ΔN integrant (Fig. 3 E).

Figure 3.

Time-dependent induction of connected cells by overexpression of cdc5ΔN. (A) Strain KLY1083 expressing three copies of GAL1-EGFP-cdc5ΔN homogeneously induced a chained cell phenotype. Typical cell morphologies (DIC images) were shown after culturing these cells under the induction conditions for 7 h (left), 12 h (middle), or 24 h (right). These cells continue to increase cell body numbers without an apparent cell division. Bar: 5 μm. (B) Strain KLY1229 expressing three copies of the corresponding FAA triple mutant failed to induce this phenotype even after 24 h induction. Bar: 5 μm. (C) Quantification of connected cells as a function of time. Percentage of cells in chains was determined by dividing the sum of cells in chains by the total number of cells. cdc5ΔN, strain KLY1083; cdc5ΔN/FAA, strain KLY1229. (D) Strain KLY1083 grows without increasing cell numbers under the induction conditions. Cells expressing control EGFP (KLY1080), EGFP-cdc5ΔN (KLY1083), or EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (KLY1229) were taken at the indicated time points upon transferring cultures into YEP-galactose. Cell number was determined by plating serial dilutions on YEP-glucose and counting the colony numbers. The number of cells at time 0 was 1.2 × 106 cells/ml with an OD600 of 0.05. The resulting cell number and OD600 at each time point were divided by those at time 0 to give relative cell number and OD600. (E) The FAA mutations do not influence the stability of EGFP-cdc5ΔN. EGFP-cdc5ΔN was detected by an anti–GFP antibody, whereas Cdc28 (loading control) was recognized by an anti–Cdc28 antibody. 1X, one copy of cdc5ΔN; 3X, three copies of cdc5ΔN.

The observed connected cell morphology could be achieved by various defects, such as a defect in cytokinesis, septum formation, or cell separation. To distinguish among these possibilities, KLY1083 cells cultured under induction conditions for 12 h were treated with zymolyase to remove the cell wall, and the cell number was counted. Even after an extensive zymolyase treatment, cells largely remained as clumps and unseparated cells without a significant increase in number (data not shown). These data suggest that the connected cell phenotype is the result of a cytokinetic defect, as defined by the criteria described previously (Hartwell 1971).

To confirm a cytokinetic defect in strain KLY1083, cells induced for 9 h were stained with calcofluor to examine chitin deposition in cell walls and septum. Strong calcofluor bands were observed between connected cell bodies (Fig. 4 A). To examine whether septum formation is completed in these cells, we performed serial optical sectioning using a confocal microscope. In most of the mother-bud necks examined, calcofluor signals were discontinuous in focal planes bisecting the cell bodies longitudinally, indicating that septa were not completely formed between the connected cell bodies (Fig. 4 A). Interestingly, among the connected cells examined (n = 56), only one cell body, either in center or at one edge of the chains, possessed bud scars (revealed as fluorescent chitin rings), indicating that other cell bodies did not generate daughter cells. Since these cells do not increase in number under the induction conditions (Fig. 3 D), the bud scars on the presumed mother cells are likely to be the result of previous budding events before transferring into induction conditions.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of cdc5ΔN results in an inhibition of septum formation between mother-bud necks. Strain KLY1083 was cultured under the induction conditions for 9 h, fixed with formaldehyde, and stained with calcofluor or DiI as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were then subjected to confocal microscopy with a series of 100-nm sections to investigate whether cytoplasms are connected between the chained cells. (A) Calcofluor signals were discontinuous in large fractions (∼70%) of mother-bud necks of the connected cell bodies, indicating a failure of septum formation. The arrow indicates a cell body with bud scars, suggesting that this is likely to be the mother cell responsible for generating other connected cell bodies. Bar: 5 μm. (B) Membrane closure is impaired in ∼50% of the necks examined. However, it was also apparent that heavy patches of DiI stain were present in other bud necks, suggesting that membrane closure was impaired but not completely inhibited by overexpression of cdc5ΔN. Barbed arrows indicate the necks with apparently connected cytoplasm. Bar: 5 μm.

To reveal cytoplasmic membrane structures of the connected cells, the same cells used for calcofluor staining were stained with DiI. We observed that most of connected cell bodies share cytoplasm. However, it was also apparent that a fraction of mother-bud necks have closed membranes (Fig. 4 B). These data suggest that some mother-bud necks overcame the cytokinetic defect imposed by overexpression of EGFP-cdc5ΔN, but failed to complete cell division.

Cell Cycle Is Not Significantly Affected in an Early Stage of Connected Cells

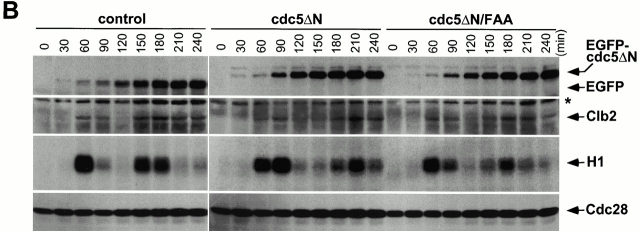

To investigate whether the cell cycle is altered in connected cells, flow cytometry analyses were carried out for the cells expressing control EGFP (KLY1080), EGFP-cdc5ΔN (KLY1083), or EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (KLY1229). Cells arrested with α-factor were transferred into YEP-galactose medium to induce protein expression upon release from a G1 arrest. Strains KLY1080 and KLY1229 appeared to progress through the cell cycle normally, regenerating the 1C DNA-containing (G1) population ∼120 min after release. In contrast, strain KLY1083 expressing EGFP-cdc5ΔN failed to regenerate a distinct 1C (G1) peak, and continued to accumulate a DNA content greater than 2C (G2/M) peak (Fig. 5 A). To further investigate whether these cells go through the cell cycle normally, the levels of Clb2 protein and Cdc28/Clb2-associated kinase activities were examined. Control strain KLY1080 achieved the maximum Cdc28/Clb2 activity (onset of M phase) in 60 and 150 min after release. Strain KLY1229 exhibited a slight delay in the cell cycle in comparison with EGFP control, whereas strain KLY1083 had a 20-min delay. However, in all cases, Clb2 protein levels and Clb2-associated kinase activities appeared to fluctuate normally with similar kinetics (Fig. 5 B), suggesting that overexpression of cdc5ΔN did not efficiently prevent endogenous Cdc5 from activating APC. Upon induction after release, approximately equal amounts of EGFP control, EGFP-cdc5ΔN, and EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA proteins were expressed in these cells (Fig. 5 B). These data suggest that overexpression of EGFP-cdc5ΔN appears to selectively inhibit cytokinesis without significantly perturbing the nuclear division cycle during the early stage of connected cells.

Figure 5.

Cdc28/Clb2 activity cycles during the early stages of connected cells. (A) Overexpression of EGFP-cdc5ΔN, but not the corresponding FAA mutant, accumulates cells with a DNA content >2C (G2/M). To carry out flow cytometric analyses, cells expressing control EGFP (KLY1080), EGFP-cdc5ΔN (KLY1083), or EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (KLY1229) were arrested with α-factor in YEP-raffinose for 3 h, washed, and transferred into YEP-galactose medium to an OD600 of 0.05. Samples were taken at the indicated time points, fixed, and subjected to flow cytometry analyses. Strain KLY1083 begins to accumulate cells with a DNA content >2C (120 min) as the first cycle completes, whereas both strains KLY1080 and KLY1299 complete the cell cycle normally. Accumulation of cells with higher DNA contents appears to be the result of induction of connected cells (see text for details). Control, strain KLY1080; cdc5ΔN, strain KLY1083; cdc5ΔN/FAA, strain KLY1229; 1C, 1C DNA content; 2C, 2C DNA content. (B) Cdc28/Clb2 activity appears to fluctuate normally in strain KLY1083 overexpressing EGFP-cdc5ΔN. To examine the cell cycle progression, cellular lysates prepared from the same cells harvested in A were subjected to Western blot analyses to examine changes in Clb2 and EGFP-cdc5ΔN levels upon release from a α-factor arrest. The level of Cdc28 was determined as a loading control for each lane. The same lysates were also used to carry out anti–Clb2 immune complex kinase assays to measure the Clb2-associated histone H1 kinase activities. The cycling Cdc28/Clb2 activities in KLY1083 strain indicate that the apparent G1 arrest (see Fig. 6a and Fig. d) observed with connected cells was not in effect in an early stage of chained cells. Samples beyond 240 min after release were not taken because of a lack of cell cycle synchrony. *Cross-reacting protein in the anti–Clb2 blot. Control, strain KLY1080; cdc5ΔN, strain KLY1083; cdc5ΔN/FAA, strain KLY1229; EGFP-cdc5ΔN, EGFP-fused cdc5ΔN proteins; EGFP, control EGFP lacking Cdc5; H1, histone H1 kinase activity.

Disturbed Septin Structures Leads to the Cytokinetic Defect in the Connected Cells

The chained cell phenotype could be achieved by continuous division of peripheral cells in the absence of cytokinesis. To reveal the cell cycle stage of individual cell bodies in the connected cells, a wild-type strain expressing a GST-fused cdc5ΔN (GST-cdc5ΔN) under control of the GAL1 promoter (KLY1053) was additionally integrated with a copy of a TUB1-GFP fusion to create strain KLY1069. Strain KLY1069 grew normally and exhibited normal spindle structures in YEP-glucose (data not shown). When these cells were cultured under induction conditions for 12 h, either a dot or short line of fluorescent signal was observed in most of internal cell bodies, indicating that these cell bodies were arrested at a point after spindle disassembly. In contrast, mitotic spindle structures were often observed in cell bodies present at the periphery of chained cells (Fig. 6 A), suggesting that cells at the edges are active in cell division. A similar observation was made when connected cells observed with strain KL1083 were immunostained with an antitubulin antibody (data not shown). The fact that most internal cell bodies possess disassembled spindles and do not bear buds suggests that a prolonged inhibition of cytokinesis in these cell bodies may have resulted in an inhibition of the next round of the cell cycle.

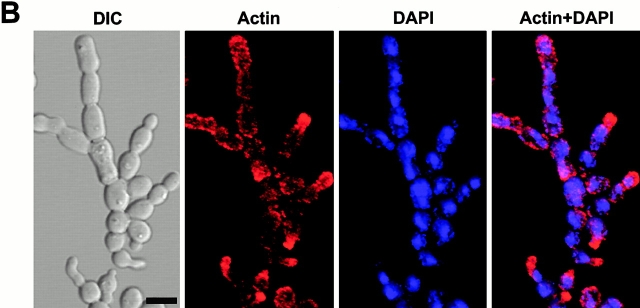

Inhibition of cytokinesis in connected cells could be the result of a failure either in recruitment of cytokinetic materials or in the function of cytokinetic structures. To investigate these possibilities, strain KLY1053 was additionally integrated with CDC3-YFP (KLY1075), CYK2-GFP (KLY1071), or MYO1-GFP (KLY1073) under control of their own promoters. These strains grew normally with apparently normal ring structures when cultured in YEP-glucose (data not shown). Upon induction of GST-cdc5ΔN, cells were then examined to determine whether these components formed normal ring structures. (Fig. 6 B and 7 A). At an early stage of induction, distinct septin ring structures were observed at all the mother-bud necks of connected cells, indicating that continuous budding events have occurred in the absence of cytokinesis at the previous mother-bud necks. Upon inducing for 12 h, double YFP-Cdc3 rings were found to be distantly placed at the mother-bud neck or remnants of YFP-Cdc3 were placed at one side of the mother-bud neck, suggesting a disturbance in maintaining properly organized septin ring structures or a defect in septin ring disassembly and relocalization. In addition, unusually wide or tiny rings of Cdc3 were occasionally observed at the axial position of incipient budding site without formation of a noticeable bud (Fig. 6 B), suggesting that a fraction of cell bodies were capable of relocalizing septins to the future budding sites but failed to assemble or maintain proper septin ring structures. Taken together, in the presence of dominant-negative cdc5ΔN, septin rings appear to be assembled normally at the growing edge of the connected cells, thereby permitting continuous budding events. However, these ring structures are cytokinesis incompetent, resulting in the generation of connected cell morphology. As with septin ring structures persisting at most of the mother-bud necks of connected cells, both Cyk2-GFP and Myo1-GFP ring structures were also remained at these sites (Fig. 7 A). This observation further supports the notion that cytokinetic processes have failed in these cells.

Figure 7.

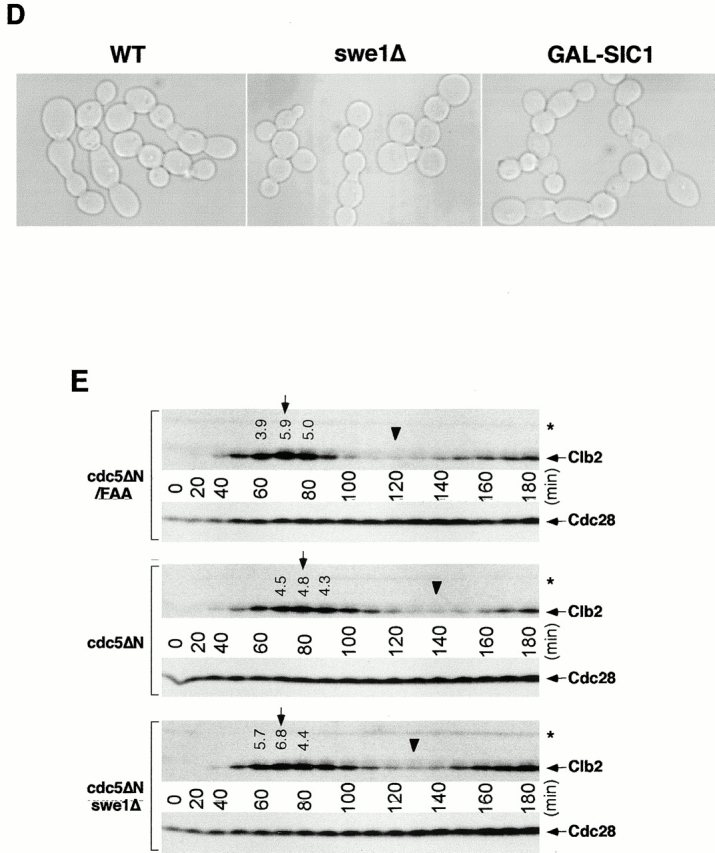

Genetic interactions between a dominant-negative cdc5ΔN mutant and cyk2Δ/myo1ΔΔ. (A) Cyk2 and Myo1 rings are largely normal in the connected cells. Often, the presence of enlarged Myo1 rings (arrows) and contraction size rings (barbed arrows) were also present. Bar: 5 μm. (B) Actin polarizes normally, but fails to relocalize to bud-necks. Strain KLY1083 cultured under the induction conditions for 12 h were fixed and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin and DAPI to visualize actin and nuclei, respectively. Bar: 5 μm. (C) Overexpression of EGFP-cdc5ΔN in cyk2Δ or myo1Δ mutants, but not in cdc10Δ or swe1Δ mutants, results in a synthetic cytokinetic defect. Strain KLY1083 carrying an additional cdc10Δ (KLY1589 and KLY1590) cyk2Δ (KLY1591), myo1Δ (KLY1593), or swe1Δ (KLY1439) mutation was generated. These strains were streaked onto YEP-glucose and YEP-galactose to examine synthetic growth defect with overexpression of EGFP-cdc5ΔN. Since both cdc10Δ and cyk2Δ mutants possess an apparent temperature sensitivity for growth, plates were incubated at 23°C for 4 d before photography. Two independently generated cdc10Δ mutants (KLY1589 and KLY1590) were used to confirm the absence of a synthetic defect with overexpression of EGFP-cdc5ΔN. (D) Introduction of swe1Δ or overexpression of GAL-SIC1 do not influence the chained-cell phenotype induced by overexpression of cdc5ΔN. Typical cell morphologies (DIC images) were shown after culturing strain KLY1083, strain KLY1439, and SKY1779 under the induction conditions for 10 h. The chained-cell phenotypes from these strains were undistinguishable. cdc5ΔN, strain KLY1083 cells; cdc5ΔN swe1Δ, strain KLY1439 cells; cdc5ΔN GAL-SIC1, strain SKY1779 cells. Bar: 5 μm. (E) Introduction of swe1Δ abolishes the cell-cycle delay induced by overexpression of cdc5ΔN. To carry out cell-cycle analyses, cells expressing control EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (KLY1229), EGFP-cdc5ΔN (KLY1083), or EGFP-cdc5ΔN, swe1Δ (KLY1439) were arrested with 5 μg of α-factor in YEP-raffinose for 3 h, washed, and transferred into YEP-galactose medium. Samples were taken at the indicated time points and subjected to Western analyses with an anti–Clb2 antibody. Deletion of swe1 abolishes a septin-checkpoint–dependent cell-cycle delay, but did not influence the chained-cell phenotype induced by overexpression of cdc5ΔN (see text for details). Arrows indicate the time point with maximum Clb2 levels, whereas arrowheads indicate the time point with the lowest level of Clb2. The level of Clb2 and Cdc28 proteins in the indicated lanes were determined using ImageQuant. The numbers are the relative levels (folds) of Clb2 in comparison to the lowest level (arrowheads). *Cross-reacting protein with the anti–Clb2 antibody. cdc5ΔN/FAA, strain KLY1229; cdc5ΔN, strain KLY1083; cdc5ΔN swe1Δ, strain KLY1439.

In contrast to double Cyk2-GFP rings observed with the cdc5-1 mutant at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 1 D), it was apparent that connected cells possess single Cyk2-GFP rings between cell bodies. Since double Cyk2 rings becomes a single ring structure at the time of cytokinesis (Lippincott and Li 1998a), this observation further supports the argument that these cells are defective in cytokinesis. Consistent with the occasional membrane closure observed with DiI staining, contraction-size rings of Myo1 and Cyk2 were at times evident (Fig. 7 A). Cyk1 and actin have been shown to form a ring after activation of the Cdc15 pathway (Lippincott and Li 1998b). Consistent with this, actin was rarely relocalized to mother-bud necks, although it was polarized normally to the tip of the peripheral cells (Fig. 7 B). These data suggest that some contractile components were recruited to these sites in the presence of aberrant septin ring structures and that these components were able, albeit poorly, to overcome the cytokinetic defect imposed by the overexpression of the COOH-terminal domain of Cdc5. However, it should be noted that completion of cell division does not appear to occur significantly within 12 h of the induction period, since cell number does not increase and nearly all the cells remain as connected cells (Fig. 3 D).

Polo-Box–dependent Interactions between Cdc5 and Septins

Since Cdc5 localizes at cytokinetic neck filaments and overexpression of cdc5ΔN induces aberrant septin ring structures with a connected cell morphology, we investigated whether Cdc5 directly interacts with septins in a yeast two-hybrid system. To increase protein stability, a destruction-box–deficient form of Cdc5 (Song et al. 2000) was used in place of the wild-type protein. We observed that the Cdc5 interacted with Cdc11 and Cdc12 strongly, whereas the corresponding polo-box mutant, cdc5/FAA, did not. Consistent with this observation, cdc5ΔN, but not the cdc5ΔN/FAA, interacted strongly with both Cdc11 and Cdc12 (Fig. 6 C). No interaction was detected between the NH2-terminal domain of Cdc5 (cdc5ΔC) and septins. Western blot analyses revealed that septins and various forms of Cdc5 were expressed at similar levels (data not shown).

To examine whether Cdc5 interacts with septins in vivo, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were carried out using strains bearing a TEV-9myc tag at the CDC11 locus and expressing either GAL1-EGFP-cdc5ΔN (SKY1732) or GAL1-EGFP-cdc5ΔN/FAA (SKY1734). Our data show that ∼30% of cdc5ΔN present in the S15 lysates were coimmunoprecipitated with Cdc11. However, no such interaction was observed with cdc5ΔN/FAA (Fig. 6 D). Similar results were also obtained with Cdc12-TEV-Myc precipitates (data not shown). These data along with two-hybrid interaction analyses strongly suggest that the polo-box domain is critical for the interactions between Cdc5 and the septins, Cdc11 and Cdc12. These observations further suggest that the connected cell morphology could be the result of a disturbance in septin ring structure through direct interactions between cdc5ΔN and septins.

Enhancement of Cytokinetic Defects by Overexpression of cdc5ΔN in cyk2Δ or myo1Δ Mutants

Although septin ring structures are largely disturbed in the connected cells, the presence of contraction size Cyk2 or Myo1 rings (Fig. 7 A) suggests that overexpression of cdc5ΔN did not completely eliminate the function of septin rings in these cells. Vallen et al. (2000) suggest that two cytokinetically important components, Myo1 and Cyk2, function in parallel pathways (see Discussion). Since both of these components localize at neck-filaments in a septin-dependent manner (Bi et al. 1998; Lippincott and Li 1998a) and overexpression of cdc5ΔN partially inhibits septin function, introduction of either the cyk2Δ or the myo1Δ mutation into the connected cells may enhance the severity of the chained cell phenotype. To test this idea, strain KLY1083 was modified with an additional cyk2Δ (KLY1591), myo1Δ (KLY1593), or cdc10Δ (KLY1589) mutation and examined under induction conditions. Introduction of additional cyk2Δ or myo1Δ into KLY1083 strain resulted in a synthetic growth defect. However, introduction of cdc10Δ did not reveal this phenomenon (Fig. 7 C), most likely because septin ring structures are already impaired by overexpression of cdc5ΔN. During the initial stage of induction (up to 6 h), both KLY1591 and KLY1593 cells yielded a significantly enhanced connected cell morphology, in comparison with those of the corresponding cyk2Δ or myo1Δ single mutants or the cells overexpressing cdc5ΔN alone (data not shown). These results indicate that the synthetic growth defect is the result of the synthetic cytokinetic defect between cdc5ΔN and either cyk2Δ or myo1Δ. In contrast, introduction of either cyk2Δ or myo1Δ mutation into the cdc5-1 mutant failed to reveal any synthetic defect under various conditions tested (data not shown). These data further support our notion that the dominant-negative cytokinetic defect observed with strain KLY1083 differs from the mitotic exit defect in cdc5-1 mutant. In addition, our data support the argument that the cytokinetic pathways regulated by Cyk2 and Myo1 are mediated by septins.

Induction of Cytokinetic Defects by a Dominant-Negative cdc5 Is Not the Result of a Swe1-dependent Cell Cycle Delay

It has been shown that defects in septin assembly cause a G2 delay in a Swe1-dependent manner, resulting in a filamentous phenotype (Barral et al. 1999; Edgington et al. 1999) due to the inability of buds to switch from polarized to isotropic growth. Hsl1 acts as a negative regulator of Swe1 (Ma et al. 1996), which is known to inhibit Cdc28 by phosphorylation of the conserved tyrosine at position 19 (Booher et al. 1993). In addition, the morphological defects resulting from the triple hsl1Δ, kcc4Δ, gin4Δ mutant require the Swe1 kinase (Barral et al. 1999). Since this mutant exhibits a morphological defect similar to the dominant-negative phenotype induced by septin disturbance in strain KLY1083, we examined whether Swe1 is also required for the latter. However, introduction of a swe1Δ into KLY1083 strain (KLY1439) did not influence cell growth or the chained cell phenotype associated with overexpression of cdc5ΔN (Fig. 7c and Fig. D). In addition, overexpression of cdc5ΔN induced a connected cell morphology in a strain possessing an activated CDC28 allele (CDC28/Y19F) as the sole CDC28 locus (data not shown). These observations indicate that the cytokinetic defect associated with overexpression of cdc5ΔN differs from the phenotype associated with Cdc28 inactivation.

When cultured under the induction conditions, strain KLY1083 exhibited defects in septin ring structure with a 20-min delay in the cell cycle (Fig. 5 B and 6 B). Since it is possible that this delay may have contributed to the cytokinetic defect induced by overexpression of cdc5ΔN, we closely monitored the cell cycle progression of strain KLY1083 and the corresponding swe1Δ strain (KLY1439) by analyzing the Clb2 levels. Control strain KLY1229, which expresses cdc5ΔN/FAA without cytokinetic defect, achieved the maximum Clb2 level ∼70 min after release from α-factor block, whereas the Clb2 level peaked at 80 min in strain KLY1083. Introduction of swe1Δ into strain KLY1083 (KLY1439) abolished the delay in Clb2 accumulation and restored the cell cycle to a degree similar to that of strain KLY1229 (Fig. 7 E). These data suggest that disruption of septin ring structures by overexpression of cdc5ΔN (Fig. 6 B) may have induced a Swe1-dependent cell cycle delay through activation of a septin assembly checkpoint pathway. However, restoration of the cell cycle by introducing swe1Δ did not influence the chained cell phenotype of strain KLY1083 [96% (153/160) after culturing under the induction conditions for 10 h; Fig. 7 D].

Since it is generally believed that inactivation of Cdc28/Clb2 is required for the initiation of cytokinesis, a delayed inactivation of Cdc28/Clb2 itself may have prevented the onset of cytokinesis or contributed to the cytokinetic defect induced by overexpression of cdc5ΔN. To eliminate this possibility, GAL-SIC1, a Cdc28/Clb2 inhibitor, was introduced at the LEU2 locus of strain KLY1083 (SKY1779), and cultured under the induction conditions. However, overexpression of GAL-SIC1 did not influence the capacity of cdc5ΔN to induce chained cells [97% (145/150) after culturing under the induction conditions for 10 h; Fig. 7 D]. Overexpression of GAL-SIC1 itself did not induce chained cell morphology in an isogenic wild-type strain (data not shown). The GAL-SIC1 appears to be functional since it inhibited the Cdc28/Clb2 activity of strain SKY1779 (40% inhibition after 4-h induction), as determined by anti–Clb2 immunocomplex kinase assays using cells arrested in M phase with nocodazole treatment for 4 h (data not shown). In addition, it was able to suppress the mitotic-exit defect associated with the cdc5-1 mutation (data not shown), as previously reported (Jaspersen, et al. 1998).

Taken together, the dominant-negative cytokinetic defect associated with overexpression of cdc5ΔN is apparently the result of a specific inhibition of cytokinesis, but not of the Swe1-dependent cell cycle delay or the delayed inactivation of Cdc28/Clb2 activity.

Discussion

The Role of Cdc5 in Cytokinesis

Cytokinesis is a highly coordinated cellular and biochemical process by which a eucaryotic cell assures the equipartition of its chromosomes and cytosolic contents. It comprises a complex set of motile events, such as reorganization of microtubules and formation of cytokinetic ring structures. Data obtained from Drosophila suggest that polo plays a role in cytokinesis (Adams et al. 1998; Carmena et al. 1998). In addition, genetic and biochemical analyses in Schizosaccharomyces pombe showed that Plo1 activates the Spg1 pathway and plays an important role in septum formation (Mulvihill et al. 1999). Although the role of Cdc5 in APC activation and mitotic exit pathway is well documented, it has not been clear whether Cdc5 has a role in cytokinesis.

Our data demonstrates that overexpression of cdc5ΔN, but not the corresponding polo-box mutant, results in dominant-negative inhibition of cytokinesis without interfering with mitotic exit. Overexpression of cdc5ΔN induces a disturbance in septin ring structures and Cdc5 interacts with two septins, Cdc11 and Cdc12, in a polo-box–dependent manner. In addition, in strain KLY1053 expressing GST-cdc5ΔN under the GAL1 control, the bud-neck localization of ADH1-EGFP-CDC5/N209A was greatly diminished (data not shown). Taken together, the dominant-negative cytokinetic defect is likely the result of overexpressed cdc5ΔN that may have prevented endogenous Cdc5 from interacting with septins and carrying out its cytokinetic function.

The septins are thought to be the major structural components of the neck filaments (Frazier et al. 1998). Thus, interactions between Cdc5 and septins suggest that localization of EGFP-cdc5ΔN at the mother-bud neck may require septins and higher-order cytokinetic neck filaments. Since a cdc10Δ mutant grows normally at 23°C, but does not possess detectable neck filaments (Frazier et al. 1998), a cdc10Δ mutation was introduced into KLY1083 strain (KLY1589). When strain KLY1589 was cultured under the induction conditions, localization of EGFP-cdc5ΔN was greatly diminished, but was not completely eliminated (data not shown). These data suggest that intact neck filaments are likely to be important for the localization of cdc5ΔN. Septins (Cdc3 and Cdc11) still localize at the mother-bud necks in the absence of Cdc10 (Fares et al. 1996; Frazier et al. 1998). Thus, a small fraction of EGFP-cdc5ΔN localized at these sites may reflect inefficient interactions with other septins or other components at the neck filaments in the absence of Cdc10. Although our data suggest that septins are likely the targets of cdc5ΔN binding, we cannot rule out the possibility that cdc5ΔN also interacts with additional component(s) other than septins at the mother-bud necks.

What role does Cdc5 play after localizing at cytokinetic neck filaments in a polo-box–dependent manner? Since Cdc5 is expressed in a late phase of the cell cycle and its kinase activity peaks in mitosis (Cheng et al. 1998; Shirayama et al. 1998), Cdc5 activity may not be required for initiation of septin ring formation. It has been shown that septin ring structures are weakened but not completely disassembled in a cdc5-1 mutant at the restrictive temperature (Kim et al. 1991). In addition, when cdc5Δ cells were depleted of Plk protein for 10 h, a large fraction of cells (51%, 227/442 cells counted) possessed severely disturbed septin rings. Taken together, Cdc5 activity may not be required for the assembly of septin rings into a higher-order structure (Byers and Goetsch 1976; Longtine et al. 1996), but rather it is likely to be important for maintaining or reinforcing cytokinetically competent structures. Our data shows that septin rings at the edges of connected cells appear to be relatively normal, as evidenced by continuous budding events. In addition, only the cells at the periphery possess polarized actin patches (Fig. 7b), suggesting that the septins at the peripheral cells were capable of providing spatial cues for actin polarization, thereby supporting continuous budding events in the absence of cytokinesis. In contrast, the internal rings appeared largely disturbed (Fig. 6 B). These data suggest that the septins formed a ring at the neck of growing buds, but failed to maintain a cytokinesis-competent structure in the presence of dominant-negative cdc5ΔN. Since remnants of septin materials are found between mother-bud necks without proper relocalization to the future budding sites, overexpression of cdc5ΔN may also have disturbed a step or steps important for disassembly of septin ring structures.

Our data suggest that overexpression of a dominant-negative cdc5ΔN induces a partial inhibition of cytokinesis as demonstrated by the presence of contractile ring size Cyk2 and Myo1 rings and occasional membrane closures. In budding yeast, cytokinesis is carried out by at least two separate pathways: an actomyosin ring-dependent pathway and an alternative pathway mediated by localized chitin depositions and cell-wall synthesis (Bi et al. 1998; Vallen et al. 2000). A recent paper suggested that Cyk2 functions in a pathway distinct from Myo1 and plays a role in septum formation (Vallen et al. 2000). Since both Myo1 and Cyk2 localizations depend on septin ring structures, it is likely that septins play a central role in regulating both cytokinetic pathways. We observed that introduction of either myo1Δ or cyk2Δ into the strain overexpressing cdc5ΔN results in enhanced cytokinetic defects (Fig. 7 C). These data strengthen the view that septins play a critical role in mediating both actomyosin-based and alternative cytokinetic pathways.

Dominant-Negative cdc5ΔN Mutant Versus Septin Mutants

Loss of septin function results in a cytokinetic defect with a chained-cell morphology (Cooper and Kiehart 1996; Longtine et al. 1996; Frazier et al. 1998), similar to that observed with overexpression of cdc5ΔN. However, these phenotypes differ from each other in several important aspects. At the restrictive temperature, septin mutants accumulate multinucleated cells with hyperpolarized buds (Hampsey 1997) due to the inability of buds to switch to isotropic growth in the absence of septin-ring–dependent Cdc28/Clb2 activation (Barral et al. 1999; Edgington et al. 1999). In addition, these cells do not sustain viability, most likely because septins play additional roles in other stages of the cell cycle. In contrast, cells overexpressing cdc5ΔN exhibit round cell bodies in connected cells and form colonies on YEP-galactose medium. These cells go through the cell cycle efficiently with cycling Cdc28/Clb2 activity. In the absence of cell division, these cells continue to increase the cell mass by continuous budding events at the periphery of the chained cells.

Mutations in septins have been shown to result in a defect in bud-site selection (Flescher et al. 1993; Chant et al. 1995; Yang et al. 1997). Similarly, the chained cells observed with strain KLY1083 (a-type haploid) exhibited a largely unipolar budding pattern (Fig. 3 A, 6, A and B, and 7, A, B, and D), whereas these cells develop a new bud at the proximal pole of a previous cytokinetic site in YEP-glucose medium (data not shown). These observations suggest that, in the absence of cytokinesis, the distal pole of the daughter cell is favored for subsequent budding event. Thus, changes in budding pattern may be attributable to the absence of proper septin relocalization to the future budding sites in the internal cell bodies while maintaining polar budding at the peripheral cells. Taken together, the disturbance in septin ring structures in the connected cells appears to result in a cytokinetic defect that is accompanied by a budding defect.

One interesting observation is that most internal cells possess short spindles (Fig. 6 A), indicating that cells arrested at a point after spindle disassembly. In addition, these cell bodies failed to generate buds, suggesting an arrest in G1. Our data also show that inactivation of Cdc28, thereby mitotic exit, occurs normally in these cells in an early stage of the cell cycle (Fig. 5 B and 7 E). Taken together, these observations allow for an intriguing possibility that a failure in cytokinesis may be detected by an unknown mechanism that leads to the cell cycle arrest in G1.

Temporal and Spatial Regulation of Mitotic Exit and Cytokinesis

Although a growing body of evidence suggests that members of the polo kinase subfamily play multiple roles such as centrosome maturation, bipolar spindle formation, activation of APC, and cytokinesis during M phase progression, it is also apparent that their roles are disparate in different organisms. For instance, studies with fission yeast Plo1 revealed that its function is important for bipolar spindle formation and cytokinesis. However, there is to date no indication of Plo1 function in the activation of APC. In budding yeast, even though polo kinase has a role in the mitotic exit pathway leading to the activation of APC, it is not known whether Cdc5 plays a role in spindle function or cytokinesis. These apparent discrepancies may be in part due to the specialization of polo kinase function among evolutionarily distant organisms, and their roles may have remained largely unchanged throughout evolution.

Our data suggest that Cdc5 plays dual roles in a late stage of M phase. We propose that, in addition to activation of APC, Cdc5 activity is required for proper function of septin ring structures during cytokinesis (Fig. 8). In this scenario, during or shortly after activation of APC, a fraction of Cdc5 relocalizes to bud-neck to carry out its cytokinetic function, an event that requires an intact polo-box. A dominant-negative cdc5ΔN, which localizes at the neck-filament, does not interfere with APC activation and mitotic exit pathway. However, it inhibits Cdc5 localization at the neck filaments, thereby impairing septin functions critical for cytokinesis. Our model also helps explain the phenotypes associated with overexpression of Cdc5 (Song et al. 2000) or an activated form of Plk (Lee et al. 1999). In both cases, unregulated Cdc5/Plk activity may have induced abnormally elongated buds by activation of APC, whereas ectopic septin rings may have arisen by reinforcing septin ring organization. Our data suggest that activation of the APC does not require a polo-box–dependent localization of Cdc5 at the septin rings, whereas overexpression of the polo-box domain is sufficient to inhibit cytokinesis. Thus, temporal and spatial regulation of Cdc5 may provide an important mechanism to coordinate mitotic exit pathway with initiation of cytokinesis.

Figure 8.

Model proposing the role of Cdc5 in coordinating the mitotic exit pathway and cytokinesis. At late anaphase/telophase, but before full spindle elongation and assembly of contractile ring, Cdc5 carries out two important functions. First, in a polo-box–independent manner, Cdc5 activates APC, which leads to inactivation of Cdc28/Clb2, thereby permitting mitotic exit. Second, in a polo-box–dependent manner, Cdc5 localizes at cytokinetic neck filaments and promotes the cytokinetic functions of septins.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Raymond Deshaies, Orna Cohen-Fix, Philip Lee, Rong Li, and Michael Lichten for critical reading of this manuscript, and Erie Lee and Dan Ilkovitch for technical support. We also thank Sue Jaspersen and David Morgan for the provision of anti–Clb2 antibody and Raymond Deshaies for anti–Cdc28 antibody and the GAL-SIC1 construct, Aaron Straight for a Tub1-GFP construct, Rong Li and John Lippincott for a GFP-Cyk2 and a GFP-Myo1 construct, and Mark Longtine for KanMX6 construct. We also acknowledge Susan Garfield for help with confocal microscopy and Jim McNally and Tatiana Kapova for processing confocal images obtained at the LRBGE Fluorescence Imaging Facility in NCI/DBS.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: APC, anaphase promoting complex; GFP, green fluorescent protein; HA, hemagglutinin.

References

- Adams R., Tavares A., Salzberg A., Bellen H., Glover D. pavarotti encodes a kinesin-like protein required to organize the central spindle and contractile ring for cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1483–1494. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler J., Steever A.B., Wheatley S., Wang Y.I., Pringle J.R., Gould K.L., McCollum D. Role of polo kinase and Mid1p in determining the site of cell division in fission yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:1603–1616. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral Y., Parra M., Bidlingmaier S., Snyder M. Nim1-related kinases coordinate cell cycle progression with the organization of the peripheral cytoskeleton in yeast. Genes Dev. 1999;13:176–187. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi E., Maddox P., Lew D.J., Salmon E.D., McMillan J.N., Yeh E., Pringle J.R. Involvement of an actomyosin contractile ring in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:1301–1312. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.5.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booher R.N., Deshaies R.J., Kirschner M.W. Properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae wee1 and its differential regulation of p34CDC28 in response to G1 and G2 cyclins. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1993;12:3417–3426. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers B., Goetsch L. A highly ordered ring of membrane-associated filaments in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1976;69:717–721. doi: 10.1083/jcb.69.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmena M., Riparbelli M.G., Minestrini G., Tavares A.M., Adams R., Callaini G., Glover D.M. Drosophila polo kinase is required for cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:659–671. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C.W., Altman R., Schieltz D., Yates J.R., Kellogg D. The septins are required for the mitosis-specific activation of the Gin4 kinase. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:709–717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chant J., Mischke M., Mitchell E., Herskowitz I., Pringle J.R. Role of Bud3p in producing the axial budding pattern of yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:767–778. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]