Abstract

Interleukin (IL)-4 is the most potent factor that causes naive CD4+ T cells to differentiate to the T helper cell (Th) 2 phenotype, while IL-12 and interferon γ trigger the differentiation of Th1 cells. However, the source of the initial polarizing IL-4 remains unclear. Here, we show that IL-6, probably secreted by antigen-presenting cells, is able to polarize naive CD4+ T cells to effector Th2 cells by inducing the initial production of IL-4 in CD4+ T cells. These results show that the nature of the cytokine (IL-12 or IL-6), which is produced by antigen-presenting cells in response to a particular pathogen, is a key factor in determining the nature of the immune response.

In response to pathogens, naive CD4+ T cells differentiate into effector Th1 and Th2 cells. Th1 cells produce IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-β, which are involved in cellmediated inflammatory reactions. Th2 cells secrete mainly IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-13, which mediate B cell activation, antibody production, and the regulation of Th1 responses (for review see reference 1). In general, a Th1 response helps eradicate intracellular microorganisms, whereas a Th2 response can control extracellular pathogens. Development of an inappropriate response can lead to ineffective immunity and may even be pathogenic. Thus, the factors that regulate the polarization to either a Th1 or Th2 immune response are critical, but remain unclear. The dose of antigen and the type of APC, and/or the co-stimulatory pathways (2–6), have been postulated to be some of the polarizing factors. However, the most effective inducer of CD4+ T cell differentiation appears to be the local cytokine environment. It is clear that the cytokine IL-12 directs differentiation to a Th1 phenotype (7, 8), while IL-4 can drive differentiation to a Th2 phenotype (9, 10).

If cytokines are indeed the driving force behind CD4+ T cell differentiation, where does the initial polarizing cytokine come from? Several findings suggest that during the initiation of a Th1 response, IL-12 is produced particularly by macrophages in response to certain microbial antigens, while NK cells are the main source of IFN-γ in response to IL-12 (7, 11). In the case of a Th2 response, the initial source of IL-4 is less clear, since none of the classical APCs make IL-4. Some non-APCs, such as mast cells and basophils, can produce IL-4, but these cells are not abundant in the lymphoid organs where T cell priming occurs (12). Recently, it has been shown that IL-4 is also produced by a minor subpopulation of T cells, the CD3+CD4+NK1.1+ cells, which may therefore have a role (13). However, the production of IL-4 by mast cells and basophils is a late event and it is not yet clear how the CD4+NK1.1+ cells become activated. An alternative possibility, however, is that other cytokines may induce the initial production of IL-4 by the CD4+ T cells; after this initial stimulus, the secreted IL-4 could act in an autocrine fashion, upregulating IL-4 production and inhibiting IFN-γ production, thereby polarizing the differentiation of Th2 cells.

In an attempt to find potential cytokines that, like IL-12, could be produced by classical APCs and could trigger the initial IL-4 production by CD4+ T cells, we analyzed the modulatory effects of IL-6, a cytokine involved in different aspects of the immune response and acute phase response (for review see references 14 and 15). Here we show that IL-6 is able to initiate the polarization of naive CD4+ T cells to effector Th2 cells by inducing the production of endogenous IL-4. In addition, IL-6 also antagonizes the IL-12– mediated differentiation of Th1 cells. We postulate that IL-6 is a key factor in the choice between a Th1 or Th2 immune response.

Materials and Methods

Cell Preparation and Reagents.

Total CD4+ T cells were isolated from spleen and lymph nodes from either wild-type B10.BR, wild-type C57BL/6J, or C57BL/6J-backcrossed IL-6–deficient mice by negative selection as previously described (16). The naive population (CD4+CD45RBhighCD44low) was purified from total CD4+ T cells obtained from cytochrome (Cyt)1 c TCR transgenic mice by staining with a red613-conjugated anti-CD4 mAb, a biotinylated anti-CD44 mAb, FITC-conjugated anti-CD45RB mAb, and PE-conjugated streptavidin (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) and cell sorting by using a FACSPLUS®. Mitomycin C-treated (50 μg/ml) syngeneic splenocytes were used as source of APCs.

Total or naive CD4+ T cells were cultured at 106 cells/ml in the presence of syngeneic APCs (5 × 105 cells/ml) with Con A (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) or synthetic moth Cyt c peptide (Yale University, New Haven, CT) plus IL-6 (R&D Sys., Inc., Minneapolis, MN), IL-12 (provided by Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA), or IL-4 (provided by DNAX, Palo Alto, CA). After 4 d, a 40–60% increase in the number of cells was observed in the different conditions. Effector Th cells were exhaustively washed, counted, and restimulated at 106 cells/ml with Con A (in the absence of APCs) or Cyt c peptide plus APCs (5 × 105 cells/ml). Anti-CD3 mAb (2C11) was immobilized on plastic at 5 μg/ml and anti-CD28 (PharMingen) was used in a soluble form (1 μg/ml).

Cell Surface Staining.

Expression of IL-6Rα was analyzed by FACS® by double staining with a FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 mAb and a biotinylated anti–IL-6Rα mAb (PharMingen) in combination with PE-conjugated streptavidin.

Competitive Reverse Transcriptase-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted as described (17) from 2 × 105 cells mixed with 104 Raji cells which were added at harvest as an internal control, and the amount of human MHC class II HLA-DR cDNA from Raji cells was used as an internal standard. In brief, after dilution (1/2) of reverse transcription reaction mixture, 5 μl was assayed for levels of DR cDNA by PCR using DR-specific primers in the presence of DR competitor construct (50 pg) to confirm the efficiency of RNA extraction and reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR procedure in each group. IL-4 transcript levels in the 5 μl of diluted (1/2) reverse transcription reaction mixture was semi-quantitated using the competitor (167 fg) in the presence of specific primers as described (18). DR primers used were (5′-CGAGTTCTATACTGAATCCTG, and 3′-GTTCTGCTGCATTGCTTTTGC). Competitor amounts shown (competition cDNA, fg or pg) are corrected to represent the amount of IL-4 or DR gene and not as the total plasmid amount. A multiple cytokine-containing competitor construct was a gift from R.M. Locksley (University of California, San Francisco, CA).

Cytokine Production.

ELISA assays were performed using purified anti–IL-4, anti–IL-12, and anti–IL-6 mAbs (3 μg/ml) as primary antibodies, the corresponding biotinylated anti–IL-4, anti–IL-12 and anti–IL-6 mAbs (1 μg/ml; PharMingen), and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated avidin D (2.5 μg/ml) (Vector Labs., Inc., Burlingame, CA), the TMB microwell peroxidase substrate and stop solution (Kirkegaard & Perry Labs., Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), using the recommended protocol (PharMingen). Recombinant IL-4 (DNAX) and IFN-γ (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) were used as standards. The specific activity of the IL-4 and the IFN-γ that were used as standards for the ELISA assays were 108 U/mg for IL-4 and 107 U/mg for IFN-γ.

Results and Discussion

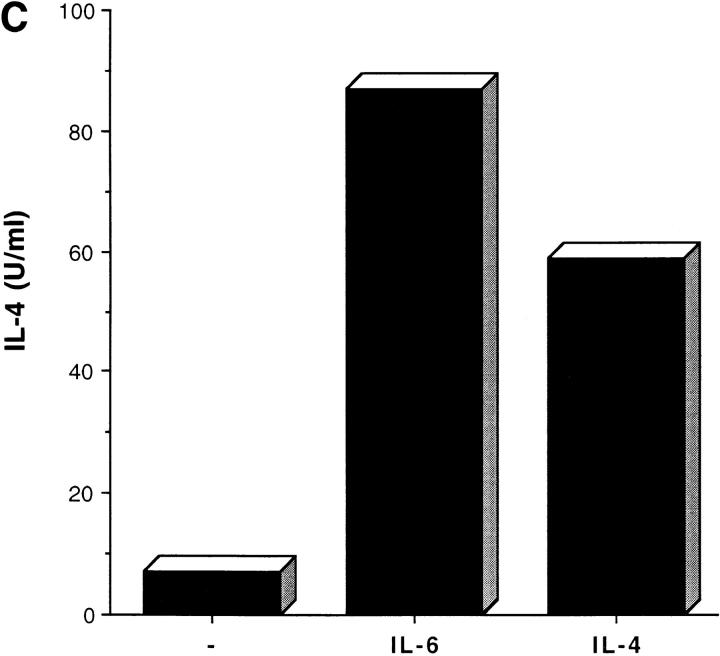

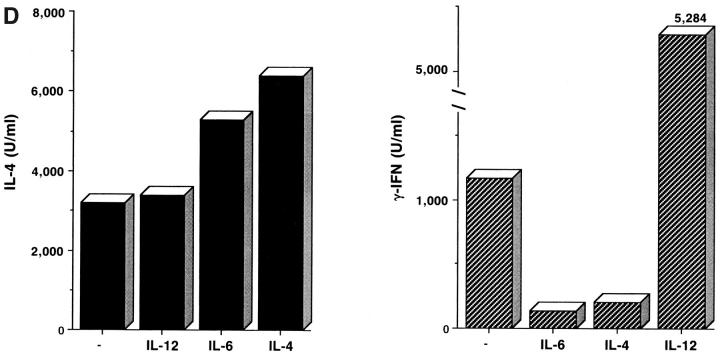

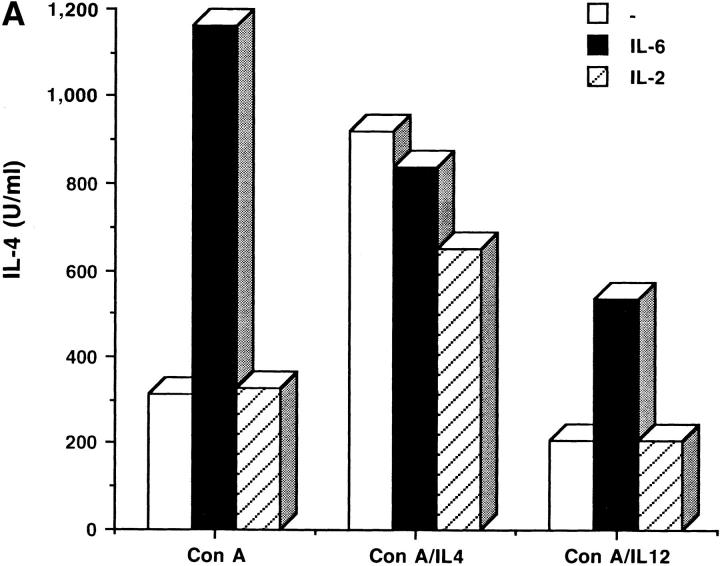

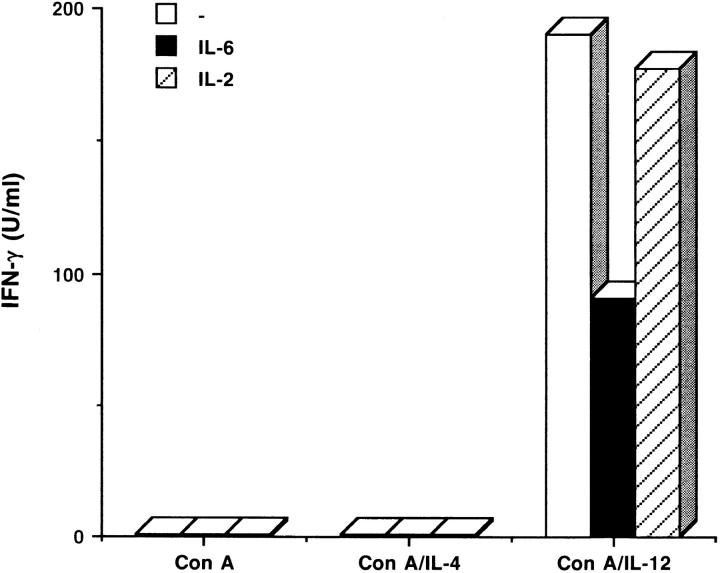

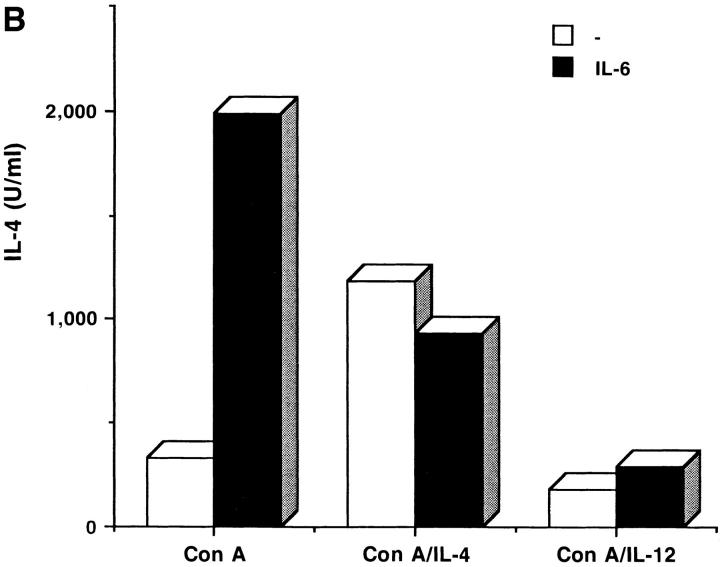

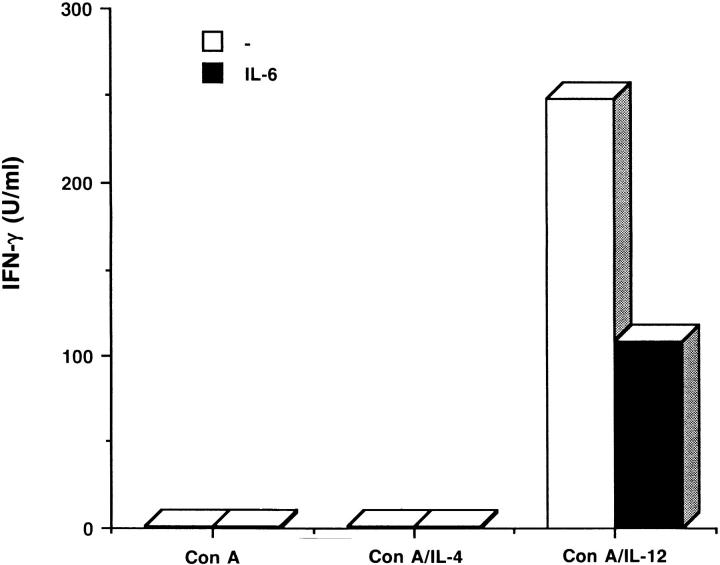

IL-6 is produced by a wide spectrum of cells including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, neuronal cells, macrophages, mast cells, tumor cell lines, and CD4+ Th2 cells, but from an immunological point of view, APCs represent the major source of IL-6 (14, 19). To determine the potential role of IL-6 in differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into effector Th1 and Th2 cells, we first analyzed the effect of exogenous IL-6. Total mouse CD4+ T cells were isolated (16) and stimulated to differentiate with Con A with or without IL-4 (Th2) or IL-12 (Th1) in the presence or absence of exogenous IL-6. After 4 d, the effector Th1 or Th2 cells were exhaustively washed, counted, and equal number of cells were restimulated with Con A for 24 h before harvesting the supernatant which was then analyzed for cytokine production. Interestingly, even in the absence of any polarizing cytokine, IL-6 directed the differentiation of the CD4+ cells to a Th2 phenotype, since the cells produce high amounts of IL-4, but not IFN-γ (Fig. 1 A). IL-6 did not modify the differentiation of the Th2 cells directed by IL-4. However, differentiation into Th1 cells by IL-12, was impaired in the presence of IL-6. Thus, Th1 cells differentiated with Con A and IL-12 in the presence of IL-6, produced less IFN-γ, and more IL-4 (Fig. 1 A). IL-6, like IL-2, has been described to be a growth factor for a number of cells (14, 15). However, only IL-6, but not IL-2, was able to modify the polarization of the CD4+ cells to Th2 phenotype (Fig. 1 A), indicating that IL-6 is involved in differentiation rather than growth of T cells. To eliminate the possibility that IL-6 could favor the expansion or IL-4 secretion of the CD4+ memory subpopulation, which has been described to display a Th2 phenotype (20), we analyzed the role of IL-6 in the differentiation of purified naive CD4+ T cells. Thus, we used CD4+ T cells from TCR transgenic mice (21), which express the α and β chain of the TCR that recognizes a pigeon Cyt c peptide; before further purification, 90–95% of the CD4+ T cells express the naive phenotype. Total CD4+ T cells were stained with anti-CD44 and anti-CD45RB mAbs and the naive CD4+ CD44lowCD45RBhigh population was isolated by cell sorting and activated with the same polyclonal stimulus, Con A, in the presence or absence of different cytokines. We observed that IL-6, in the absence of any other cytokine, was able to promote the differentiation of naive CD4+ cells to IL-4–producing cells (Fig. 1 B). In addition, we also analyzed the effect of IL-6 in the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells stimulated by specific antigen. The presence of IL-6 during the activation with Cyt c peptide drove differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into IL-4–producing effector Th2 cells as well or better than IL-4 (Fig. 1 C). Therefore, the modulatory effect of IL-6 in T cell differentiation is not a consequence of an expansion of the memory subpopulation.

Figure 1.

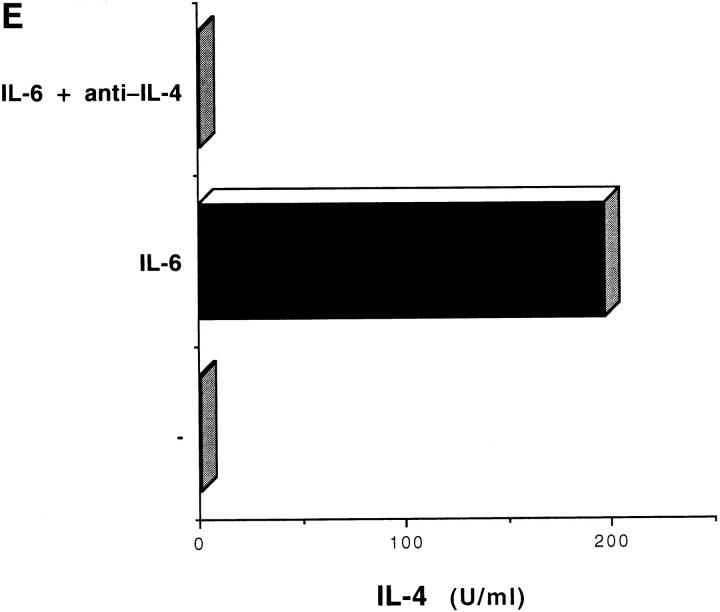

IL-6 directs differentiation of CD4+ T cells into Th2 cells. (A) Total CD4+ T cells (106/ml) were purified from normal B10.BR mice and stimulated (in the presence of 5 × 105 cell/ml syngeneic APCs) with Con A (2.5 μg/ml) alone, Con A plus IL-4 (103 U/ml) or Con A plus IL-12 (3.5 ng/ml), in the absence (−) or presence of IL-6 (100 ng/ml) or IL-2 (50 U/ml). After 4 d, cells were exhaustively washed and restimulated (106 cells/ml) with Con A alone (2.5 μg/ml) in the absence of APCs or additional cytokines. Supernatants were harvested 24 h later and analyzed for IL-4 and IFN-γ production by ELISA. (B) Total CD4+ population was isolated from Cyt c TCR transgenic mice, and the naive CD4+ CD45RBhighCD44low subpopulation was purified by cell sorting. Naive CD4+ T cells were then stimulated with Con A alone, Con A plus IL-4, or Con A plus IL-12, and APCs, in the presence or absence of IL-6. After 4 d, cells were exhaustively washed and restimulated (106 cell/ ml) with Con A alone for 24 h before harvesting the supernatants for cytokine measurement. (C) Naive CD4+CD45RBhighCD44low CD4+ T cells isolated from Cyt c TCR transgenic mice were stimulated with Cyt c peptide and APCs, in the presence of medium, IL-6 (100 ng/ml), or IL-4, (103 U/ml). After 4 d, cells were exhaustively washed and restimulated (106 cell/ml) with Cyt c peptide and APCs for 24 h. (D) Total CD4+ T cells from normal B10.BR mice were stimulated with immobilized anti– CD3 mAb (5 μg/ml) and soluble anti–CD28 (1 μg/ml) in the presence of medium (−), IL-6 (100 ng/ml), or IL-4 (103 U/ml) and, after 4 d, they were restimulated with immobilized anti–CD3 mAb. (E) Total CD4+ T cells from normal B10.BR mice were stimulated with Con A and APCs in the presence of medium (−), IL-6 (100 ng/ml) (IL-6), or IL-6 (100 ng/ml) plus anti–IL-4 mAb (10 μg/ml) (IL-6 + anti–IL-4), for 4 d. Cells were then restimulated (106 cells/ml) with Con A alone as described in A.

Other cytokines have also been described to indirectly modulate the polarization towards Th1 and Th2. IL-10, a Th2 cytokine, promotes Th2 and inhibits Th1 cells, their cytokines, and related immune phenomena. Although the mechanism is not clear yet, several lines of evidence indicate that IL-10 reduces the Th1 response by an inhibitory effect on the IL-12 expression by APCs such as macrophages (22–24). In contrast, the immunoregulatory role of IL-6 in the polarization of Th1 and Th2 is not an indirect effect on the APCs. Thus, IL-6 inhibited IFN-γ production and stimulated IL-4 synthesis by Th1 cells that have been differentiated in the presence of exogenous IL-12 (Fig. 1, A and B), eliminating the possibility of inhibiting the production of IL-12 by APCs. In addition, IL-6 did not affect the expression on the APCs of co-stimulatory molecules such as B7.1 and B7.1, which have also been involved in the differentiation of Th1 and Th2 cells (5, 6; data not shown). To further prove that the effect of IL-6 was on T cells directly, rather than APCs, we differentiated CD4+ T cells with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb plus anti-CD28 mAb in the complete absence of APCs, and then restimulated these cells with anti-CD3 mAb alone. The presence of IL-6 (or IL-4 as a control) during the first culture resulted in an increase of IL-4 production and a dramatic reduction of IFN-γ production (Fig. 1 D) by the cells that were elicited, showing that IL-6 directly favors the polarization of naive CD4+ T cells to Th2 cells via the T cell.

IL-4 is the most effective differentiation factor for Th2 cells; it acts by promoting the secretion of more IL-4 and inhibiting the production of IFN-γ by T cells (9, 10). It was therefore possible that IL-6 could directly upregulate the synthesis of IL-4 by T cells and, consequently, that the IL-6 effect was mediated through IL-4, which would be responsible for the suppression of Th1 differentiation, while favoring a Th2 response. To address this hypothesis, CD4+ T cells were differentiated with Con A and IL-6 in the presence or absence of neutralizing anti–IL-4 mAb, and after 4 d, the cells were washed and restimulated with Con A. The ability of IL-6 to polarize CD4+ T cells toward the Th2 phenotype was blocked by anti–IL-4 mAbs, since the cells were unable to produce IL-4 upon restimulation (Fig. 1 E). These results indicated that the differentiation of Th2 cells by IL-6 is dependent on the endogenous production of IL-4. It was therefore possible that IL-6 may trigger the Th2 pathway by inducing small amounts of IL-4, which in turn would act as an autocrine differentiation factor for the Th2 cells.

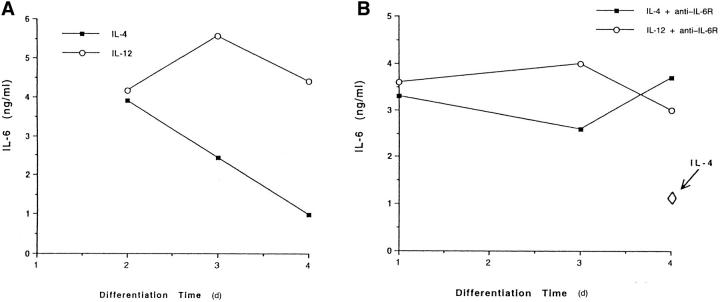

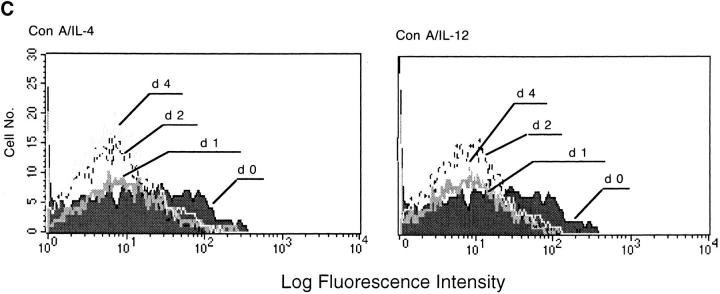

As mentioned above, APCs represent the major source of IL-6 early in the immune response. To examine the physiological role of IL-6 in T cell differentiation, we first measured the production of IL-6 during the differentiation of Th1 and Th2 cells. CD4+ T cells were stimulated with Con A and IL-4 or IL-12 in the presence of APCs, and supernatants were harvested after different periods of time to measure IL-6 secretion. After 2 d of culture, identical levels of IL-6 were detected in the IL-4 and IL-12 cultures (Fig. 2 A). However, while the IL-6 level in the presence of IL-12 was sustained during the course of T cell differentiation, it decayed dramatically during the differentiation of Th2 cells in the presence of IL-4. No IL-6 was detected after restimulation of either Th1 or Th2 cells with Con A in the absence of APCs (data not shown), suggesting that the IL-6 that we detected during the first stimulation was secreted mainly by the APCs. The difference in the kinetics of IL-6 synthesis during the differentiation of Th1 and Th2 could, therefore, be due either to upregulation of IL-6 on the APCs in the presence of IL-12, or greater IL-6 consumption by Th2 cells than by Th1 cells. To test this, we examined IL-6 production during the differentiation of Th1 and Th2 in the presence of an anti–IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) mAb, to block IL-6 consumption. In the presence of anti– IL-6R mAb IL-6 did not diminish during the differentiation of Th2 cells (Fig. 2 B). These data indicate that the IL-6 produced by APCs was consumed during the differentiation of Th2 cells, but not during differentiation of Th1 cells, supporting the idea that IL-6 plays a role during Th2 polarization by acting directly on T cells. IL-6R is a heterodimer of the signal transducer gp130 (which is also a component of the IL-11, ciliary neurotrophic factor, leukemia inhibitory factor, and onconstatin M receptors) and the specific IL-6Rα chain (25–30). IL-6R has been found in both unstimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets and its expression is downregulated upon activation (31). Differential expression of the IL-6Rα chain during Th1 or Th2 differentiation could explain the higher IL-6 consumption by the Th2 cells. We also analyzed, therefore, the expression of IL-6Rα during the differentiation of CD4+ T cells in effector Th1 or Th2 cells. However, the expression of cell surface IL-6Rα was regulated similarly during the differentiation of Th1 or Th2 cells in the presence of either IL-4 or -12 (Fig. 2 C). Low levels of IL-6Rα were present on unstimulated CD4+ T cells, and downmodulation occurred after the first day of stimulation, remaining at almost undetectable levels during the differentiation of both Th1 and Th2 cells. These results indicated that the effects of IL-6 in the differentiation of Th2 cells were not due to a differential distribution of the IL-6Rα.

Figure 2.

Regulation of IL-6 secretion by APCs during the differentiation of Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cells. (A) Total CD4+ T cells (B10.BR) were stimulated with Con A (2.5 μg/ml) plus IL-4 (103 U/ml) or IL-12 (3.5 ng/ml) in the presence of APCs. Supernatants were harvested at different times of stimulation (day 2, 3, or 4) and IL-6 secretion was analyzed. (B) Total CD4+ T cells were stimulated as described in A, but in the presence of anti–IL-6Rα chain mAb (10 μg/ml). The arrow indicates the production of IL-6 after 4 d of stimulation with Con A and IL-4, in the absence of anti–IL6Rα mAb. (C) Expression of IL6Rα during the differentiation of Th1 and Th2 cells. CD4+ T cells unstimulated (day 0) or stimulated in the presence of APCs, with Con A plus IL-4 (Con A/IL-4) or IL-12 (Con A/ IL-12) for different periods of time (day 1, 2, or 4) were harvested, stained with anti-CD4 and anti–IL-6Rα mAbs, and analyzed by FACS®. Fluorescence profiles show the expression of IL-6Rα in the CD4+ population.

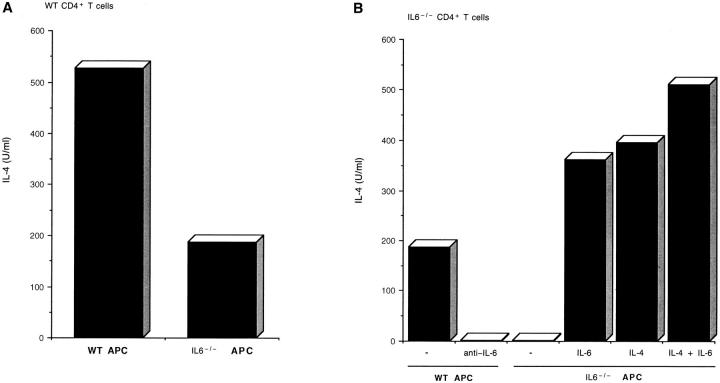

If IL-6 was required for Th2 cell differentiation in vitro, it would follow that T cells from IL-6−/− mice should be incapable of developing Th2 effector cells. The experiments described below show that this appears to be true. In correlation with the previous characterization of IL-6−/− mice (32, 33), analysis of cellular populations in the spleen and thymus did not show any differences between wildtype (WT) and IL-6−/− mice (data not shown), and IL-6−/− mice developed normally. We therefore used splenocytes from IL-6−/− mice as APCs to further establish that the production of endogenous IL-6 by the APC plays a critical role in the polarization of the CD4+ T cells to effector Th2 cells. We purified CD4+ T cells from WT mice and stimulated them for 4 d with Con A in the presence of APCs from WT mice or IL-6−/− mice in the absence of any added exogenous cytokines. Restimulation with Con A resulted in significantly less IL-4 production in cells differentiated in the presence of IL-6−/− than in WT APCs (Fig. 3 A). Although the production of IFN-γ under these conditions (absence of exogenous IL-12) was low, the levels of IFN-γ produced by CD4 cells differentiated in the presence of IL-6−/− APCs were higher than those produced by cells stimulated in the presence of WT APCs (data not shown).

Figure 3.

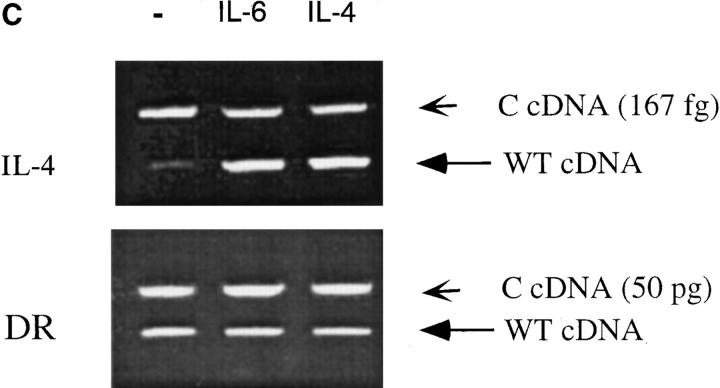

IL-6–producing APCs are required for the differentiation of Th2 cells. (A) Total CD4+ T cells (106/ml) were isolated from WT mice and stimulated with Con A (2.5 μg/ml) alone in the presence of APCs (5 × 105 cells/ml) from WT (WT APC) or IL-6–deficient (IL-6− /− APC) mice. After 4 d, CD4+ T cells were washed and restimulated (106 cells/ml) with Con A in the absence of APCs, and supernatants were collected after 24 h. (B) Total CD4+ T cells were isolated from IL-6–deficient (IL-6− /−) mice and stimulated with Con A plus medium (−), neutralizing anti–IL-6 mAb (10 μg/ml) (anti–IL-6), IL-6 (100 ng/ml), IL-4 (103 U/ml), or both (IL-4 + IL-6), in the presence of APCs from WT (WT APC) or IL-6– deficient (IL-6− /−) mice. After 4 d, cells were washed and restimulated (106 cells/ml) with Con A alone for 24 h. Only in the case where all cells (both CD4 T cells and APCs) were from IL-6−/− mice did we observe a slightly lower recovery (70–80% of the recovery from other conditions) after 4 d of primary culture. Nevertheless, cell number was normalized (106 cells/ml) before restimulation. (C) Induction of IL-4 gene expression in CD4+ Th2 cells differentiated in the presence of IL-6. Naive CD4+ T cells (12) from Cyt c TCR transgenic mice were primary cultured with moth Cyt c peptide (5 μg/ml) and APCs in the absence (−) or the presence of IL-6 (100 ng/ml) or IL-4 (103 U/ml) for 4 d. Cells were then washed and stimulated with Cyt c peptide and APCs. After 20 h, 2 × 105 cells were harvested and used for the quantitation of IL-4 mRNA by competitive RT-PCR. (Top) The expression of IL-4 transcripts. (Bottom) The expression of DR transcripts. Small arrow, the competitor DNA.

In vivo experiments have showed an impaired immune response in IL-6−/− mice. These mice fail to control infection with Listeria monocytogenes and have a diminished T cell– dependent body response against vesicular stomatitis virus (32–34). In addition, CD4+ cells from WT mice infected with Candida albicans express IL-4, but reduced IgE and IL-4 mRNA was observed in IL-6−/− mice (35). Nevertheless, due to the numerous effects of IL-6 in vivo, it is difficult to study by which mechanism IL-6 affects the immunopathology of infection and whether this is mediated by a modification in T cell differentiation. We examined, therefore, the in vitro differentiation of CD4+ T cells from IL-6–deficient mice. IL-6−/− CD4+ T cells stimulated with Con A in the presence of WT APCs, which can provide the IL-6 required, produced IL-4, but this IL-4 production was impaired when the IL-6 pathway was blocked by the addition of anti–IL-6 mAbs (Fig. 3 B). Most significantly, however, was that in the complete absence of IL-6, when IL-6−/− CD4+ T cells were stimulated in the presence of IL-6−/− APCs, no in vitro Th2 response was obtained (Fig. 3 B). The difference between complete absence of IL-4 production when IL-6−/− APCs were used with IL-6−/− T cells compared with IL-6−/− APCs and WT T cells may have been the result of either IL-6 production from contaminating WT APCs in the T cells or a contribution of IL-6 from the WT T cells. Moreover, high IL-4 production was restored in cells that were differentiated in the presence of IL-6−/− APCs together with an exogenous source of IL-6 (Fig. 3 B). Similar levels of IL-4 were detected when CD4+ T cells were differentiated in the presence of IL-4, and no significant additional increase was observed when both IL-4 and IL-6 were present during the differentiation, indicating again that both IL-4 and IL-6 were using the same pathway.

To demonstrate whether the upregulation of IL-4 production by IL-6 was due to an induction of IL-4 gene expression rather than a posttranslational mechanism, e.g., increasing IL-4 secretion, we examined the levels of IL-4 mRNA. Naive CD4+ T cells were isolated from Cyt c TCR transgenic mice (see above) and stimulated with specific Cyt c peptide in the absence or presence of IL-6 or IL-4. After 4 d, cells were washed and restimulated with Cyt c peptide, and total RNA was isolated 20 h later. The expression of the IL-4 gene was determined by competitive RT-PCR of IL-4–specific transcripts (18). The presence of exogenous IL-6 or IL-4 during the differentiation (Th2 cells) resulted in the induction of high levels of IL-4 mRNA upon antigen restimulation (Fig. 3 C). Quantitation of IL-4 transcripts in cells differentiated in the presence of IL-6 or IL-4 were 100-fold higher than in the absence of cytokines (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that IL-6 causes the differentiation of Th2 cells by upregulating IL-4 gene expression. The transcriptional regulation of the IL-4 gene has not yet been characterized as extensively as the regulation of the IL-2 gene. Several positive and negative regulatory elements in the 5′ flanking region of the IL-4 gene have been described (36–39). Among five different nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) binding elements, one located between −90 and −60 is important for the activation of the IL-4 gene expression. Like the distal NFAT site in the IL-2 promoter (40–42), this element binds NFAT (either NFATp or NFATc) in association with AP-1 components (37, 43). In addition, recently three functional binding sites for the C/EBP family of transcriptional factors have been identified in the IL-4 promoter (44), which might be regulated by IL-6 since members of this family (NF-IL6) have already been described as having been activated by IL-6 in other systems (45–50). Whether IL-6 acts through these sites will be the subject of future studies.

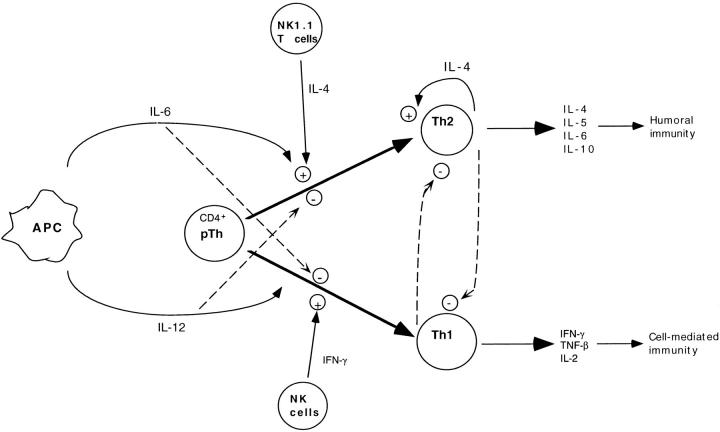

Both in vivo and in vitro experiments support the idea that, although other factors can play immunomodulatory roles, IL-4 and IL-12 are both necessary and sufficient for the polarization of Th1 and Th2 during the response to different pathogens. Considerable interest in the initial source of the IL-4 that drives Th2 cell differentiation has been expressed and recent attention has focused on mast cells or NK1.1+ CD4 T cells. We propose here that IL-6 is one of the stimuli in the initial production of IL-4 which provides a new mechanism to initiate Th2 CD4+ T cell differentiation. The levels of IL-6 that we used in these experiments are relatively high, just as the levels of IL-4 that also must be used to direct Th2 differentiation in vitro are (500– 1,000 U/ml IL-4). Presumably, for both IL-4 and IL-6 produced endogenously, lower levels produced in a local microenvironment suffice. Consistent with this idea, although the IL-6 effect is mediated through IL-4 (since it is blocked by anti–IL-4), the levels of IL-4 that can be detected are very low, presumably because of local consumption, but are sufficient to direct Th2 cell differentiation. Our data suggest a model (Fig. 4) for Th2 differentiation that is strikingly similar to the mechanism used for Th1 differentiation. In both cases, the source of the polarizing cytokine is the APC, IL-12 in the case of Th1 cells and IL-6 in the case of Th2 cells. Although APCs are the major source of IL-6 in vitro, other cell types that produce IL-6, such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, keratinocytes or others, could also contribute to the overall in vivo IL-6 production. In our in vitro model, activation of the APC is proposed to result in the secretion of IL-6 which, in combination with the antigen, will participate in the induction of IL-4 gene expression in naive CD4+ T cells. In the second step, the low levels of IL-4 secreted by the T cells is sufficient to induce upregulation of the IL-4 and IL-4 receptor genes in an autocrine manner, while it inhibits the expression of the IFN-γ gene. Cells are therefore subsequently polarized to a Th2 phenotype using their own source of IL-4.

Figure 4.

Schematic model for the differentiation of precursors Th cells (pTh) into effector Th1 and Th2 cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Samanta for technical assistance and F. Manzo for assistance with manuscript preparation. We also thank Genetics Institute for providing the IL-12 and DNAX Institute for a gift of IL-4.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA65861 and 1-P01-AI30548. R.A. Flavell is an investigator and T. Nakamura was an associate of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. E. Fikrig is a Pew Scholar.

1 Abbreviations used in this paper: Cyt, cytochrome; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; RT, reverse transcriptase; WT, wild type.

References

- 1.Paul WE, Seder RA. Lymphocyte response and cytokines. Cell. 1994;76:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bretscher PA, Wei G, Menon JN, BielefeldtOhmann H. Establishment of stable, cell-mediated immunity that makes “susceptible” mice resistant to Leishmania major . Science (Wash DC) 1992;257:539–542. doi: 10.1126/science.1636090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Constant S, Pfeiffer C, Woodard A, Pasqualini T, Bottomly K. Extent of T cell receptor ligation can determine the functional differentiation of naive CD4+T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1591–1596. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfeiffer C, Stein J, Southwood S, Keterlaar H, Sette A, Bottomly K. Altered peptide ligands can control CD4 T lymphocyte differentiation in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1569–1574. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuchroo VK, Das MP, Brown JA, Ranger AM, Zamvil SS, Sobel RA, Weiner HL, Nabavi N, Glimcher LH. B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory molecules activate differentially the Th1/Th2 developmental pathways: application to autoimmune disease therapy. Cell. 1995;80:707–718. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenschow DJ, Ho SC, Sattar H, Rhee L, Gray G, Nabavi N, Herold KC, Bluestone JA. Differential effects of B7-1 and anti-B7-2 monoclonal antibody treatment on the development of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1145–1155. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh CS, Macatonia SE, Tripp CS, Wolf SF, O'Garra A, Murphy KM. Development of Th1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science (Wash DC) 1993;260:547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.8097338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seder RA, Gazzinelli R, Sher A, Paul WE. IL-12 acts directly on CD4+T cells to enhance priming for IFNγ production and diminish IL-4 inhibition of such priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10188–10192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Gros G, Ben-Sasson SZ, Seder R, Finkelman FD, Paul WE. Generation of interleukin 4 (IL-4)-producing cells in vivo and in vitro: IL-2 and IL-4 are required for in vitro generation of IL-4 producing cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:921–929. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swain SL, Weinberg AD, English M, Huston G. IL-4 directs the development of Th2-like helper effectors. J Immunol. 1990;145:3796–3806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Andrea A, Rengarayu M, Valginte NM, Chemini J, Kibin M, Aste M, Chan SH, Kobayashi M, Young D, Nichbarg E. Production of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (interleukin 12) by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1387–1398. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seder RA, Plaut M, Barvieri S, Urban J, Fenkelman FD, Paul WE. Mouse splenic and bone marrow cell populations that express high affinity Fc epsilon receptors and produce interleukin 4 are highly enriched in basophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2835–2839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimoto T, Paul WE. CD4+NK1.1+T cells promptly produce interleukin-4 in response to in vivo challenge with anti-CD3. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1285–1295. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Snick J. Interleukin-6: an overview. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:253–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kishimoto T, Akira S, Taga T. Interleukin-6 and its receptor: a paradigm for cytokines. Science (Wash DC) 1992;258:593–597. doi: 10.1126/science.1411569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamogawa Y, Minasi L-AE, Carding S, Bottomly K, Flavell RA. The relationship of IL-4 and IFNγproducing T cells studied by lineage ablation of IL-4–producing cells. Cell. 1993;75:985–995. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA extraction by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenolchloroform. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiner SL, Zheng S, Corry DB, Locksley RM. Constructing polycompetitor cDNAs for quantitative PCR. J Immunol Methods. 1993;165:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90104-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aarden LA, De Groot ER, Schaap OL, Lansdorp PM. Production of hybridoma growth factor by monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1411–1416. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley LM, Duncan DD, Yoshimoto K, Swain S. Memory effectors: a potent, IL-4–secreting helper T cell population that develops in vivo after restimulation with antigen. J Immunol. 1993;150:3119–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaye J, Hsu M-L, Sauron M-E, Jameson SC, Gascoigne NRJ, Hedrick SM. Selective development of CD4+ T cells in transgenic mice expressing a class II MHC–restricted antigen receptor. Nature (Lond) 1989;341:746–749. doi: 10.1038/341746a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O'Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tripp CS, Wolf SF, Unanue ER. Interleukin 12 and tumor necrosis factor α are costimulators of interferon γ production by natural killer cells in severe combined immunodeficiency mice with listeriosis, and interleukin 10 is a physiologic antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3725–3729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Andrea A, Aste-Amezaga M, Ma X, Kubin M, Trinchieri G. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits human lymphocyte interferon γ-production by suppressing natural killer cell stimulatory factor/IL-12 synthesis in accessory cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1041–1048. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamasaki K, Taga T, Hirata Y, Yawata H, Kawanishi Y, See B, Tanaiguchi T, Hirano T, Kishimoto T. Cloning and expression of human interleukin-6. Science (Wash DC) 1988;241:825–828. doi: 10.1126/science.3136546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taga T, Hibi M, Hirata Y, Yamasaki K, Yasukawa K, Matsuda T, Hirano T, Kishimoto T. Interleukin-6 triggers the association of its receptor with a possible signal transducer, gp 130. Cell. 1989;58:573–581. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hibi M, Murakami M, Saito M, Hirano T, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Molecular cloning and expression of an IL-6 signal transducer, gp 130. Cell. 1990;63:1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gearing DP, Comeau MR, Friend DJ, Gimpel SD, Thut CJ, McGourty J, Brasher KK, King JA, Gillis S, Mosley B, Ziegler SF, Cosman D. The IL-6 signal transducer, gp 130: an oncostatin M receptor and affinity converter for the LIF receptor. Science (Wash DC) 1992;255:1434–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.1542794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taga T, Narazaki M, Yasukawa K, Saito T, Miki D, Hamaguchi M, Davis S, Shoyab M, Yancopoulos GD, Kishimoto T. Functional inhibition of hematopoietic and neurotrophic cytokines by blocking the interleukin-6 signal transducer gp 130. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10998–11001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin T, Taga T, Tsang ML-S, Yasukawa T, Kishimoto T, Yang Y-C. Involvement of interleukin-6 signal transducer gp 130 in interleukin-11–mediated signal transduction. J Immunol. 1993;151:2555–2561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coulie PG, Stevens M, Van Snick J. High and low affinity receptors for murine interleukin 6. Distinct distribution on B and T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:2107–2114. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830191121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kopf M, Baumann H, Freer G, Freudenberg M, Lamers M, Kishimoto T, Zinkernagel R, Bluethmann H, Köhler G. Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6–deficient mice. Nature (Lond) 1994;368:339–342. doi: 10.1038/368339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poli V, Balena R, Fattori E, Markatos A, Yamamoto M, Tanaka H, Ciliberto G, Rodan GA, Constantini F. Interleukin-6 deficient mice are protected from bone loss caused by estrogen depletion. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1994;13:1189–1196. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dalrymple SA, Lucian LA, Slattery R, McNeil T, Aud DM, Fuchino S, Lee F, Murray R. Interleukin-6– deficient mice are highly susceptible to Listeria monocytogenesinfection: correlation with inefficient neutrophilia. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2262–2268. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2262-2268.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romani, L., A. Mencacci, E. Cenci, R. Spaccapelo, C. Toniatti, P. Puccetti, F. Bistoni, and V. Poli. 1996. Impaired neutrophil response and CD4+ T helper cell 1 development in interleukin 6–deficient mice infected with Candida albicans. <JNL>J. Exp. Med. 183:1345–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Bruhn KW, Nelms K, Boulay JL, Paul WE, Lenardo MJ. Molecular dissection of the mouse interleukin-4 promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9707–9711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chuvpilo S, Schomberg C, Gerwing R, Heinfling A, Reeves R, Grummt F, Serfling E. Multiple closelylinked NFAT/octamer and HMG I(Y) binding sites are part of interleukin-4 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5694–5704. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.24.5694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szabo SJ, Gold JS, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Identification of cis-acting regulatory elements controlling interleukin-4 gene expression in T cells: roles for NF-Y and NF-ATc. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4793–4805. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Todd MD, Grusby MJ, Lederer JA, Lacy E, Lichtman AH, Glimcher LH. Transcription of interleukin-4 gene is regulated by multiple promoter elements. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1663–1674. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boise LH, Petrynyak B, Mao X, June CH, Wang C-Y, Lindsten T, Bravo R, Kovary K, Leiden JM, Thompson CB. The NFAT-1 DNA binding complex in activated T cells contains Fra-1 and JunB. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1911–1919. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jain J, McCaffrey PG, Valge-Archer VE, Rao A. Nuclear factor of activated T cells contains Fos and Jun. Nature (Lond) 1992;356:801–804. doi: 10.1038/356801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Northrop JP, Ullman KS, Crabtree GR. Characterization of nuclear and cytoplasmic components of the lymphoid-specific nuclear factor of activated T cells (NF-AT) J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2917–2923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rooney JW, Hoey T, Glimcher LH. Coordinate and cooperative roles for NFAT and AP-1 in the regulation of murine IL-4 gene. Immunity. 1995;2:473–483. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davydov IV, Krammer PH, Li-Weber M. Nuclear factor–IL-6 activates the human IL-4 promoter in T cells. J Immunol. 1995;155:5273–5279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akira S, Issihiki H, Sugita T, Tanabe O, Kinoshita S, Nishio Y, Nakajima T, Hirano T, Kishimoto T. A nuclear factor for IL-6 expression (NF-IL6) is a member of a C/EBP family. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1990;9:1897–1906. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao Z, Umek RM, McKnight SL. Regulated expression of three C/EBP isoforms during adipose conversion of 3T3-L1 cells. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1538–1552. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang CJ, Chen TT, Lei HY, Chen DS, Lee SC. Molecular cloning of a transcription factor, AGP/EBP, that belongs to members of the C/EBP family. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6642–6653. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Descombes P, Chojkier M, Lichtsteiner S, Falvey E, Schibler U. LAP, a novel member of C/EBP gene family, encodes a liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1541–1551. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.9.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poli V, Mancini FP, Cortese R. IL-6DBP, a nuclear protein involved in interleukin-6 signal transduction, defines a new family of leucine zipper proteins related to C/EBP. Cell. 1990;63:643–653. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90459-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakajima T, Kinoshita S, Sasagawa T, Sasaki K, Naruto M, Kishimoto T, Akira S. Phosphorylation at threonine-235 by a ras-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade is essential for transcription factor NF-IL6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2207–2211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]