Abstract

Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a Caspase recruitment domain (ASC) belongs to a large family of proteins that contain a Pyrin, AIM, ASC, and death domain-like (PAAD) domain (also known as PYRIN, DAPIN, Pyk). Recent data have suggested that ASC functions as an adaptor protein linking various PAAD-family proteins to pathways involved in nuclear factor (NF)-κB and pro-Caspase-1 activation. We present evidence here that the role of ASC in modulating NF-κB activation pathways is much broader than previously suspected, as it can either inhibit or activate NF-κB, depending on cellular context. While coexpression of ASC with certain PAAD-family proteins such as Pyrin and Cryopyrin increases NF-κB activity, ASC has an inhibitory influence on NF-κB activation by various proinflammatory stimuli, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α, interleukin 1β, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Elevations in ASC protein levels or of the PAAD domain of ASC suppressed activation of IκB kinases in cells exposed to pro-inflammatory stimuli. Conversely, reducing endogenous levels of ASC using siRNA enhanced TNF- and LPS-induced degradation of the IKK substrate, IκBα. Our findings suggest that ASC modulates diverse NF-κB induction pathways by acting upon the IKK complex, implying a broad role for this and similar proteins containing PAAD domains in regulation of inflammatory responses.

Keywords: inflammation, signal transduction, IκB kinase, monocytes, NF-κB

Introduction

Proteins containing the death domain fold (DDF)* play pivotal roles in apoptosis and inflammatory responses. The DDF represents a protein interaction motif consisting of a bundle of (usually) six antiparallel α-helices. This core structure comprises four families of evolutionarily conserved and closely related domain families, including the death domains (DDs), death effector domains (DEDs), caspase recruitment domains (CARDs), and Pyrin, AIM, Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a Caspase recruitment domain (ASC), and death domain like (PAAD; also known as PYRIN, DAPIN, Pyk) domains (1–7).

Several DDF proteins are also known to participate in activation of transcription factor nuclear factor (NF)-κB, a family of dimeric transcription factors containing the Rel-homology domain. In mammals, NF-κB family members play critical roles in regulating expression of genes involved in inflammatory and immune responses, including certain cytokines, lymphokines, immunoglobulins, and leukocyte adhesion proteins (for a review, see reference 8). NF-κBs exist in the cytoplasm in inactive form sequestered by inhibitory proteins called inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB). Proteasome-dependent degradation of IκBs is linked to their phosphorylation by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which consists of two related kinases, IKKα and IKKβ, and a scaffold subunit IKKγ (Nemo; for a review, see reference 9). Phosphorylation of IκBs triggers their poly-ubiquitination and degradation, thus freeing NF-κB-family transcription factors to enter the nucleus and transactivate promoters of various target genes.

PAADs are found in diverse proteins implicated in apoptosis, inflammation, and cancer, though their molecular mechanisms of action are largely unknown. The founding member of the PAAD-family proteins, Pyrin, is mutated in families with Familial Mediterranean Fever, a hereditary hyperinflammatory response syndrome (10). Mutant alleles of a gene encoding another PAAD-family protein, Cryopyrin (PYPAF-1, NALP3) have been associated with familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome, Muckle-Wells syndrome, and Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome providing further hints of a role for PAADs in control of inflammatory responses (11, 12). A role for some PAAD-containing proteins in regulation of apoptosis has also been suggested (13–16).

ASC consists of a NH2-terminal PAAD followed by a COOH-terminal CARD, representing one of only two genes in the human genome that encodes proteins combining these two protein interaction domains. ASC derives its name, “apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD” from its reported ability to trigger apoptosis when overexpressed in some tumor cell lines and from its localization to punctuate cytosolic structures (specks; reference 15). ASC is also known as TMS1 (target of methylation-induced silencing), and becomes inactive in ∼40% of breast cancers (16). Expression of ASC is found predominantly in monocytes and mucosal epithelial cells (17). Recently, it has been reported that, in transient transfection overexpression assays, coexpression of ASC with certain other PAAD-family proteins (Cryopyrin, PYPAF-7) activates NF-κB. However, the role of endogenous ASC has heretofore not been explored. We report here that the PAAD of ASC associates with the IKK complex, modulating activation of IKKα and IKKβ by cytokines and LPS. Moreover, ASC has dual properties as either an enhancer or suppressor of NF-κB, depending on which pathways for NF-κB activation are stimulated.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids.

The complete open reading frame of ASC cDNA and segments corresponding to ASC-PAAD or -CARD were amplified by RT-PCR (Stratagene) from HL-60 cells and subcloned in sense and antisense orientation into pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) containing a NH2-terminal Myc epitope tag. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion-protein vectors were generated by subcloning into pEGFP (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.). Authenticity of all constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Plasmids encoding IKKα, IKKα (K44M), IKKβ, IKKβ (K44A), and IKKγ were gifts of Michael Karin (University of California, San Diego, CA), while IKKi, and TBK1 were gifts from Shizuo Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan).

RT-PCR.

HEK293N Neo- or ASC-PAAD stable expressing cells were treated with 20 ng ml−1 TNFα for 4 h, lysed in Trizol reagent (GIBCO BRL), and total RNA was isolated according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. DNase I–treated RNA (1 μg) was transcribed into single-stranded cDNA using Superscript II (GIBCO BRL) and amplified for 30 cycles using Amplitaq (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) with either TRAF1 or GAPDH specific primers.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Reporter Gene Assays.

HEK293N, HEK293T, and MCF7 cells were cultured in DMEM, while THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. When indicated, cells were treated with 10 to 20 ng ml−1 TNFα or IL-1β, or 600 ng ml−1 LPS for various times. Transfection of HEK293 cells was accomplished using Superfect (QIAGEN), while THP-1 (107) cells were transfected with Lipofectamine Plus (Life Technologies), holding total DNA content constant. At 48 h after transfection, stable THP-1 cells or 293N cells were selected in 650 or 800 μg ml−1 G418 (Calbiochem), respectively. MCF7 and THP-1 cells were transfected with double-strand siRNAs on two consecutive days using Oligofectamine (Life Technologies). siRNA1: 5′-UCAUCCUGAAUCUGAUCUUdTdT-3′, 5′-AAGAUCAGAUUCAGGAUGAdTdT-3′, siRNA2: 5′-GAUGCGGAAGCUCUUCAGUdTdT-3′, 5′-ACUGAAGAGCUUCCGCAUCdTdT-3′, siRNAcntr: 5′-CAAGUAUUUGACGACCGAGdTdT-3′, 5-CUCGGUCGUCAAAUACUUGdTdT-3′.

For NF-κB reporter gene assays, typically, 105 cells cultured in 24-well plates in 5% serum were transfected with a total of 1 μg plasmid DNA (normalized for total DNA), including 100 ng of pNF-κB-LUC, pAP1-LUC, or p53-LUC (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) and 6 ng of a Renilla luciferase gene driven by a constitutive TK promoter (pRL-TK; Promega). Lysates were analyzed using the Dual Luciferase kit (Promega).

Coimmunoprecipitations.

For immunoprecipitations, cells were lysed in isotonic lysis buffer (150 or 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris/HCl [pH 7.4], 0.2% NP-40, 12.5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM NaF, 200 μM to 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, and 1× protease inhibitor mix [Roche]), using 2–8 × 107 cells for endogenous proteins. Clarified lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using agarose-conjugated anti-c-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), or protein-G–conjugated anti-IKKβ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-IKKα (BD Biosciences), or anti-ASC antibodies (17). After incubation at 4°C for 4–12 h, immune-complexes were washed three times in lysis buffer, separated by SDS/PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblotting using various antibodies as above in conjunction with ECL detection system (Amersham Biosciences). Alternatively, lysates were directly analyzed by immunoblotting after normalization for total protein content. Anti-Tubulin and anti-β-Actin antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and anti–ICAM-1 and anti-GFP antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Kinase Assays.

IKKα or IKKβ were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, using 5 × 105 cells for IKK transfectants and 106 cells for endogenous IKKs. Immune-complexes were washed twice in lysis buffer (as above), once in lysis buffer containing 2 M urea followed by two washes in kinase buffer (20 mM Hepes [pH 7.6], 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.5 mM DTT), equilibrated for 5 min in kinase buffer, adjusted to 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT, and finally incubated in 20 μl kinase buffer supplemented with 35 μM ATP, 5 μCi γ[32P] ATP and 1 μg glutathionine-S-transferase (GST)-IκBα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at 30°C for 30 min (18).

NF-κB DNA-binding Activity Assays.

Electromobility gel-shift assays (EMSA) were used to measure NF-κB DNA-binding activity, essentially as described (19). Briefly, 106 cells, either untreated or treated with TNFα for 20 min were lysed in buffer A (10 mM Hepes, pH 8.0, 0.5% NP-40, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, and 200 mM sucrose), washed twice in buffer A, and pelleted nuclei were incubated in 1× packed cell volume of buffer B (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 420 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT) overnight, clarified supernatants diluted 1:1 in buffer C (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT). Protease and phosphatase inhibitors were added to all buffers. Nuclear extracts (2 μg) were incubated with 10 fmole of a 32P-end-labeled double-strand consensus NF-κB oligonucleotide (Promega) probe with or without 2 μg of anti-p65 antibody or control IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). For competition assays, a 50× molar excess of unlabeled oligonucleotide was added. DNA–protein complexes were separated by nondenaturing PAGE, and analyzed by autoradiography.

Immunofluorescence Analysis.

Cells were transferred to 4-well polylysine-coated chamber slides (LabTec), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with 0.4 μg ml−1 of the indicated antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), followed by 4 μg ml−1 FITC and TRITC labeled secondary antibodies (DakoCytomation/Molecular Probes). Both secondary antibodies were combined and used for each well in 0.1% BSA and 1% serum. Cells were analyzed by confocal laser-scanning microscopy (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Results

ASC Differentially Modulates NF-κB Activity, Depending on the Stimulus.

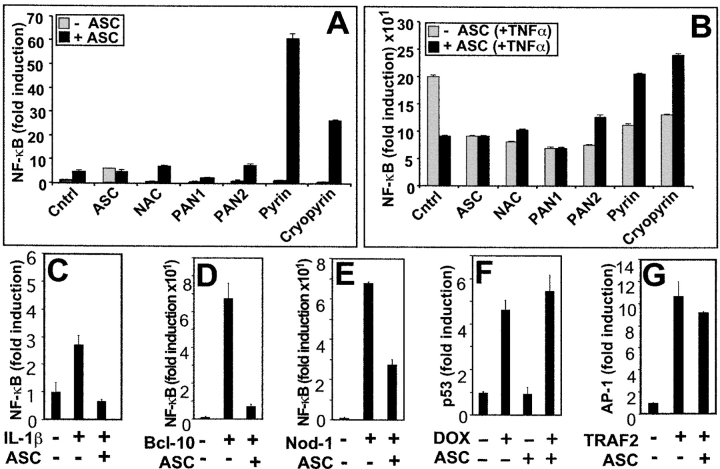

Recently, it was reported that coexpression of ASC with Cryopyrin (PYPAF-1/NALP3) or PYPAF-7 (PAN6) induces NF-κB activity in transient transfection reporter gene assays performed in HEK293T cells (20, 21). These cells contain essentially no detectable ASC (unpublished data), thus avoiding contributions of the endogenous ASC protein. Similar to previous reports, we observed 20–70-fold inductions in NF-κB activity, when ASC was coexpressed with Cryopyrin or Pyrin in HEK293T cells, as measured by reporter gene assays in HEK293T cells (Fig. 1 A). In contrast, neither ASC, nor Pyrin or Cryopyrin alone induced significant NF-κB activity. The ability of ASC to collaborate with other PAAD-containing proteins in NF-κB induction was selective, as coexpression with NAC (NALP1, DEFCAP, CARD7), PAN1 (PYPAF-2, NALP2, NBS1), or PAN2 (PYPAF-4, NALP4) did not result in significant NF-κB activity.

Figure 1.

Differential effects of ASC on NF-κB activation. (A and B) HEK293T cells were transfected with either 200 ng of control plasmid or 200 ng of various plasmids encoding PAAD-family members (ASC, NAC, PAN1, PAN2, Pyrin, or Cryopyrin) alone (gray bars) or in combination with 200 ng of ASC-encoding plasmid (black bars). Transfections also included 100 ng of pNF-κB and 6 ng of pRL-TK, maintaining the total DNA of transfections at 1 μg. At 36 h after transfection, cells were either left untreated (A) or stimulated with TNFα for 8 h (B) and analyzed for NF-κB activity by reporter gene assay. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3) and are expressed as fold-induction relative to cells transfected with pcDNA3 control plasmid without TNFα stimulation, and are representative of several experiments. (C) HEK293N cells, transfected as above, were cotransfected with IL-1RI and IL-1RAcP and induced with IL-1β for 8 h. (D and E) Cells were transfected with plasmids encoding Bcl-10 (D) or Nod (E) alone or in combination with ASC, and NF-κB activity was measured. (F and G) To assess specificity of NF-κB reporter gene assays in HEK293N cells, p53 transcriptional activity was determined after transfection with p53-responsive luciferase reporter plasmid pRL-p53 and stimulation the next day with DNA-damaging drug doxorubicin (DOX) (40 ng ml−1) (F), or AP-1 transcriptional activity was determined after transfection with control or TRAF2-encoding plasmids with or without ASC and the AP-1–responsive plasmid pRL-AP1 (G). Transcriptional activity was measured 1 d later by reporter gene assay (fold induction, mean ± SD; n = 3).

During studies of the effects of ASC on NF-κB induction, we noticed that expression of this protein reduced NF-κB activity in HEK293N and HEK293T (Fig. 1) and other cell lines (unpublished data) after stimulation with cytokine TNFα. For example, TNFα-induced increases in NF-κB activity were reduced by approximately half in ASC-transfected compared with control transfected HEK293T cells (Fig. 1 B). Not only ASC, but all proteins which contain PAAD-domains were found to have an inhibitory influence on TNFα-mediated induction of NF-κB activity in these reporter gene assay experiments, including NAC, PAN1, PAN2, and to a lesser extent Pyrin, and Cryopyrin. When ASC was coexpressed with Pyrin or Cryopyrin (but not NAC, PAN1, or PAN2), the net levels of NF-κB activity returned to control levels seen in TNFα-stimulated cells (Fig. 1 B).

To extend these studies to other types of stimuli known to induce NF-κB activity, we performed similar reporter gene assays, stimulating cells with the cytokine IL-1β or transfecting cells with NF-κB–inducing proteins such as Bcl-10 (which has been implicated in NF-κB induction by B cell and T cell antigen receptors; reference 22) and Nod-1 (a putative intracellular sensor of LPS; reference 23). In every case examined, transient overexpression of ASC suppressed NF-κB activity (Fig. 1, C–E). Similar results were obtained for several cell lines, including HEK293T, HEK293N, HeLa, Cos7, and HT1080 cells (unpublished data). The effects of ASC on NF-κB induction were specific, in as much as overexpression of ASC did not interfere with transcriptional activation of p53, AP-1, β-Catenin/Tcf, as measured by reporter gene assays (Fig. 1, F and G; and unpublished data). Immunoblotting experiments confirmed production of all plasmid-derived proteins, excluding a general effect of ASC on protein synthesis or stability (see below).

ASC Inhibits NF-κB Induction via Its PAAD.

To map the domain in ASC responsible for modulation of NF-κB activity, we compared the effects of full-length ASC to truncation mutants containing only the PAAD or CARD domains. Neither the PAAD nor the CARD of ASC induced NF-κB activity when expressed by transient transfection in cell lines such as HEK293N (Fig. 2 A), consistent with a previous report (24). In TNFα-stimulated cells, both full-length ASC and the PAAD of ASC profoundly suppressed NF-κB activity, while the CARD of ASC did not (Fig. 2 B). Inhibition of TNFα-induced NF-κB activity by the PAAD of ASC was dose-dependent (Fig. 2 C). NF-κB DNA binding activity was also reduced by overexpression of the PAAD of ASC, as measured by EMSAs using a DNA probe containing NF-κB binding sites (Fig. 2 D), and correlated with reduced translocation of the p65 subunit of NF-κB into the nuclei of TNFα-stimulated cells, as visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy analysis (unpublished data).

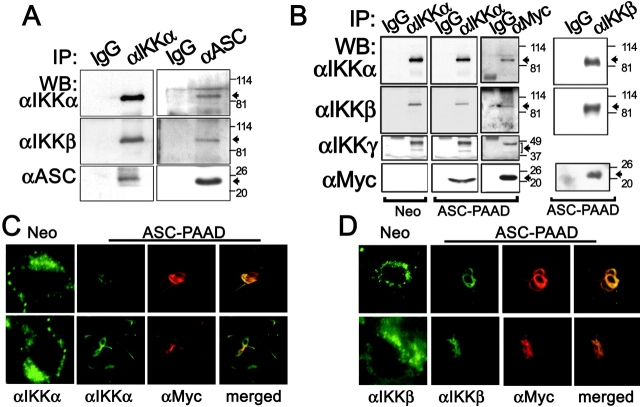

Figure 2.

The PAAD of ASC regulates NF-κB activity, NF-κB DNA-binding activity, and expression of endogenous NF-κB target genes. (A–C) NF-κB activity as measured by reporter gene assays. Data represent fold induction (mean ± SD; n = 3) and are representative of several experiments. (A) NF-κB activity data are presented for HEK293N cells transfected with plasmids as indicated. (B) HEK293N cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated and NF-κB activity was measured after TNFα stimulation for 8 h. (C) Dose dependence of ASC-mediated inhibition of NF-κB activity, shown by transfecting increasing amounts of ASC-PAAD plasmid into HEK293N cells and measuring TNFα-induced NF-κB activity by reporter gene assay 1 d later. (D) NF-κB DNA-binding activity was measured by EMSA in nuclear lysates prepared from HEK293T cells that had been transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids. NIK(KK429,430AA) served as a control inhibiting TNF induction of NF-κB DNA-binding activity. As indicated, either IgG or anti-p65 antibodies were added for producing “super-shifted” DNA–protein complexes, or in lane 2 unlabeled NF-κB–binding DNA probe was included as a competitor for demonstrating binding specificity: band-shift (BS); super-shift (SS); free probe (FP). (E; top panel) Expression of ASC protein was measured by immunoblotting in THP-1 cells treated for the indicated times with 600 ng ml−1 LPS. Data represent quantification of scanned bands on blots using densitometry, normalized for Tubulin expression, and presented as a fold-increase relative to untreated cells. (Middle panel) HEK293N Myc-ASC-PAAD or Neo stable transfectants were assayed for NF-κB reporter gene activity at 8 h after stimulation with TNFα (mean ± SD; n = 3). (Bottom panel) Expression of Neo, ASC-PAAD in transient (trans.) and stable transfected HEK293N cells was compared with endogenous ASC in THP-1 cells untreated (−) or treated (+) for 6 h with LPS, by immunoblotting. Expression in the stable cell line was 1.5 times that of LPS stimulated and 2.9 times that of resting THP-1 cells. (F) HEK293N-Neo and Myc-ASC-PAAD stable transfectants were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding GFP or GFP-antisense ASC together with a NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmid and NF-κB activity was measured 8 h after TNFα stimulation. Alternatively, lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-GFP and anti-Myc antibodies. Note that the shift in molecular weight of GFP in antisense ASC-transfected cells is due to an artificial open reading frame, created by insertion of the antisense cDNA into pEGFP. (G) HEK293N cells were transiently transfected with either Neo control or Myc-ASC-PAAD plasmids, treated with TNFα for 4 h where indicated and lysates were SDS-PAGE/immunoblotted using anti-TRAF1, anti-TRAF2, and anti-Tubulin antibodies to measure expression of the endogenous proteins. (H) Alternatively, total RNA was isolated from stably transfected HEK293N cells and analyzed by RT-PCR for TRAF1 and GAPDH. Lanes represent: HEK293N-Neo cells (1) untreated and (2) treated for 4 h with TNFα; and HEK293N-ASC-PAAD cells (3) untreated and (4) treated for 4 h with TNFα; (M) molecular size marker. (I) THP-1 cells that had been stably transfected with plasmids encoding GFP or GFP-ASC-PAAD were treated with LPS as indicated and lysates were subject to SDS-PAGE/immunoblotting using anti- ICAM-1, anti-GFP, and anti-βActin antibodies.

To further explore the role of the PAAD of ASC in modulating NF-κB activity, we generated stable transfectants of HEK293N cell expressing the ASC-PAAD protein. The levels of ASC-PAAD protein produced in the stable transfectants were determined to be comparable to the levels of ASC found endogenously in some types of cells, such as THP-1 monocytic cells in which we have observed that LPS stimulates expression of endogenous ASC mRNA and protein (Fig. 2 E). Clones of HEK293N stably expressing ASC-PAAD demonstrated ∼80% reduced activation of a transfected NF-κB reporter gene in response to TNFα (Fig. 2 E), consistent with expectations from transient transfection experiments. Moreover, this effect on NF-κB activity in ASC-PAAD expressing HEK293N cells was confirmed to be ASC-dependent by introducing of an ASC-antisense plasmid, in which a cDNA fragment corresponding to ASC-PAAD was subcloned in reverse orientation downstream of a GFP open reading frame (Fig. 2 F). Transfection of various amounts of this ASC-antisense plasmid induced concentration-dependent decreases in the amount of Myc-ASC-PAAD protein, correlating with dose-dependent restoration of NF-κB activity after TNFα stimulation.

Next, we evaluated whether stable expression of ASC-PAAD interfered with TNFα-induced expression of an endogenous NF-κB target gene, TRAF1, which contains several NF-κB binding sites in its promoter (25). While TNFα increased TRAF1 protein and mRNA, this response was markedly blunted in ASC-PAAD–expressing cells (Fig. 2, G and H). Analysis of control proteins (TRAF2, Tubulin) and control mRNA (GAPDH) demonstrated the specificity of these results.

To extend these studies yet to another cell line, THP-1 monocytic cells were stably transfected with plasmids encoding either GFP or GFP fused to ASC-PAAD. LPS induced expression of endogenous NF-κB–inducible gene, ICAM-1 (26), in control GFP-expressing THP-1 cells, producing a >20-fold increase in ICAM-1 protein within 10 h (Fig. 2 I). In contrast, ICAM-1 was markedly reduced in ASC-PAAD–expressing cells. Comparable expression of GFP-ASC-PAAD and GFP was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 2 I). Taken together, these data indicate that ASC is capable of suppressing TNFα- and LPS-induced expression of endogenous NF-κB target genes through its PAAD.

ASC-PAAD Modulates NF-κB Induction at the Level of the IKK Complex.

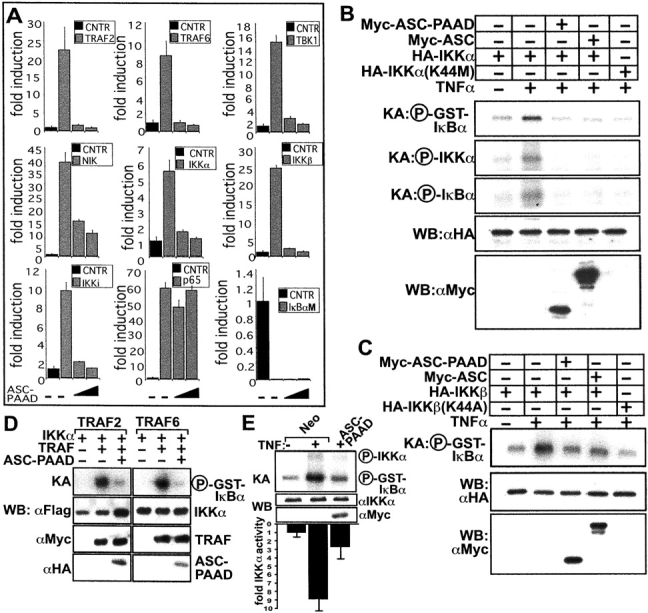

To map where the PAAD of ASC affects the NF-κB activation pathway, NF-κB activity was induced by transient transfection of plasmids encoding various intracellular signal-transducers that operate within cytokine receptor pathways leading to phosphorylation of IκB, a key event required for NF-κB release. Coexpression of ASC blocked induction of NF-κB activity by the adaptor proteins TRAF2 and TRAF6, the TRAF-binding kinases TBK1 and NIK, the IKK complex constituents IKKα and IKKβ, and the related kinase IKKi (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, coexpression of ASC did not suppress reporter gene activation induced by NF-κB-p65. Thus, ASC blocks upstream of NF-κB, apparently at the level of the IKK complex.

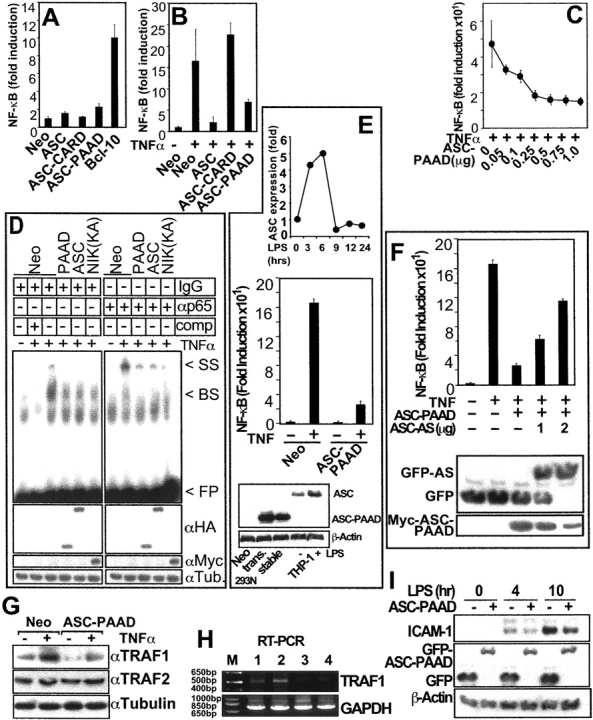

Figure 3.

ASC inhibits NF-κB induction at the level of the IKK complex. (A) HEK293N cells were transfected with 200 ng of plasmids encoding various NF-κB–inducing proteins, as indicated, and either 200 or 400 ng of ASC-encoding plasmid. NF-κB activity was measured 1 d later by reporter gene assays as described above, and data presented as fold-induction relative to cells not transfected with effector plasmids (mean ± SD; n = 3). The IκBαM (S32, 36A) mutant served as a negative control. (B) IKKα in vitro kinase activity toward GST-IκBα in transient transfected HEK293N cells in response to TNFα. Kinase dead IKKα (K44M) was used as a control for blocking TNFα induction of IKK activity. Shown are phosphorylated GST-IκBα, as well as auto-phosphorylated IKKα and phosphorylated endogenous IκBα, which associates with the IKK complex. (C) In vitro kinase assays as above were performed using HA-IKKβ and HA-IKKβ (K44A). (D) HEK293N cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding effectors of the TNFα (TRAF2) and IL-1β (TRAF6) pathways and in vitro kinase assays were performed, measuring IKKα kinase activity on GST-IκBα. (E) Endogenous IKKα kinase activity was measured by in vitro kinase assay in HEK293N-ASC-PAAD or -Neo stable transfectants. The IKKα kinase assay data from five experiments were quantified by scanning-densitometry analysis of the autoradiograms, and are presented below the gel as a bar graph showing fold-activity compared with uninduced HEK293N-Neo cells, normalized to IKKα expression as determined by immunoblotting (mean ± SD). KA, kinase assay; WB, Western blot.

To directly evaluate the effects of ASC on IKK activity, in vitro kinase assays were performed. For initial experiments, either HA-epitope tagged IKKα (Fig. 3 B) or IKKβ (Fig. 3 C) was expressed alone or in combination with ASC or ASC-PAAD. Then HA-IKKα or HA-IKKβ was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, and in vitro phosphorylation of GST-IκBα substrate was measured. As negative control, kinase-dead IKKs were used. TNFα induced ∼5–10-fold increases in IKKα and IKKβ activity, while ASC or ASC-PAAD expression suppressed IKKα and IKKβ activity to essentially baseline levels (Fig. 3, B and C). This inhibitory effect of ASC and ASC-PAAD on IKKα and IKKβ activity was not attributable to a difference in the total levels of the IKKα or IKKβ proteins, as determined by immunoblot analysis, thus confirming that ASC suppresses activation of the IKK complex. ASC also suppressed autophosphorylation of IKKα (Fig. 3 B) and IKKβ (unpublished data), as well as phosphorylation of associated endogenous IκBα, in these kinase assays. Similar results were obtained when IKKα or IKKβ was activated in cells by transient transfection of plasmids encoding intracellular signaling proteins such as TRAF2 and TRAF6 (Fig. 3 D, and unpublished data).

To extend these studies involving expression of epitope-tagged proteins by transient transfection, the activity of endogenous IKKα was evaluated using HEK293N cells stably transfected with either control or Myc-ASC-PAAD (Fig. 3 E). ASC-PAAD potently suppressed TNFα-induced activation of endogenous IKKα in these cells, as determined by kinase assays where immunoprecipitated IKKα was tested for ability to phosphorylate GST-IκBα substrate in vitro. Autophosphorylation of IKKα was also suppressed in ASC-PAAD–expressing cells. These differences in IKKα activity were not due to differences in the total levels of IKKα protein, as determined by immunoblotting (Fig. 3 E).

ASC Associates with IKKα and IKKβ.

Having mapped the site of action of ASC to the IKK complex, we performed experiments to explore whether ASC associated with these protein kinases. In the course of our studies of ASC, we observed that expression of ASC is induced in myeloid-lineage hematopoietic cells such as THP-1 monocytic or HL-60 monomyelocytic leukemia cell lines by LPS and TNFα (Fig. 2 E, and unpublished data). We therefore asked whether endogenous ASC protein could be found associated with endogenous IKK complex components after LPS- or TNFα-stimulation in these cells. Co-IP experiments provided evidence of association of ASC with both IKKα and IKKβ in LPS-stimulated THP-1 and TNFα-treated HL-60 cells (Fig. 4 A, and unpublished data). These protein interactions were reciprocally demonstrable, regardless of whether immune-complexes were prepared using anti-IKKα and anti-IKKβ antibodies (followed by immunoblotting with anti-ASC antiserum) or using anti-ASC antiserum (followed by immunoblotting with anti-IKKα or anti-IKKβ antibodies; Fig. 4 A, and unpublished data). We also analyzed the HEK293N-ASC-PAAD stable transfectants to determine whether the PAAD is sufficient for association with the endogenous IKK complex. Again, coimmunoprecipitation (coIP) experiments demonstrated specific interaction of ASC-PAAD with the endogenous IKK complex, as indicated by the association of ASC with IKKα, IKKβ, as well as IKKγ (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

ASC associates with IKKα and IKKβ. (A and B) CoIP assays were performed using THP-1 cells that had been treated with LPS for 30 min. Cleared lysates were subject to coIP using either IgG, anti-IKKα, or anti-ASC antibodies and the resulting immune-complexes were analyzed by WB using various antibodies, as indicated. (B) Cleared lysates from stable HEK293N-Neo and HEK293N-ASC-PAAD cells were subjected to coIP using either IgG, anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ, or anti-Myc antibodies and the resulting immune-complexes were analyzed by WB. (C and D) Immunofluorescence analysis of stably transfected HEK293N-Neo and HEK293N-ASC-PAAD cells was performed, using either anti-IKKα (C) or anti-IKKβ (D) polyclonal rabbit and goat antibodies, respectively, in combination with mouse monoclonal anti-Myc epitope antibody for detection of Myc-ASC-PAAD protein. From left to right: Localization of FITC-labeled IKKα or IKKβ is shown for Neo cells and ASC-PAAD–expressing cells, followed by localization of TRITC-labeled Myc-ASC-PAAD, and then two-color fluorescence analysis (merge).

In addition, immunofluorescence microscopy was used to examine the intracellular location of IKKα and IKKβ in HEK293-Neo and -ASC-PAAD cells (Fig. 4, C and D). In HEK293-Neo cells, endogenous IKKα and IKKβ were diffusely distributed throughout the cytosol. In contrast, IKKα and IKKβ relocated to filament-like structures in HEK293N-ASC-PAAD cells, colocalizing with the ASC-PAAD proteins. Treatment of these cells with TNFα did not affect the colocalization of ASC-PAAD with IKKs, nor did it affect the location of IKKs in control cells lacking ASC-PAAD (unpublished data). We conclude therefore that the PAAD of ASC associates with endogenous IKKα- and IKKβ-containing protein complexes, altering their intracellular location and suppressing cytokine- and LPS-mediated activation of these protein kinases involved in NF-κB induction.

Suppression of Endogenous ASC Expression Enhances IκBα Degradation.

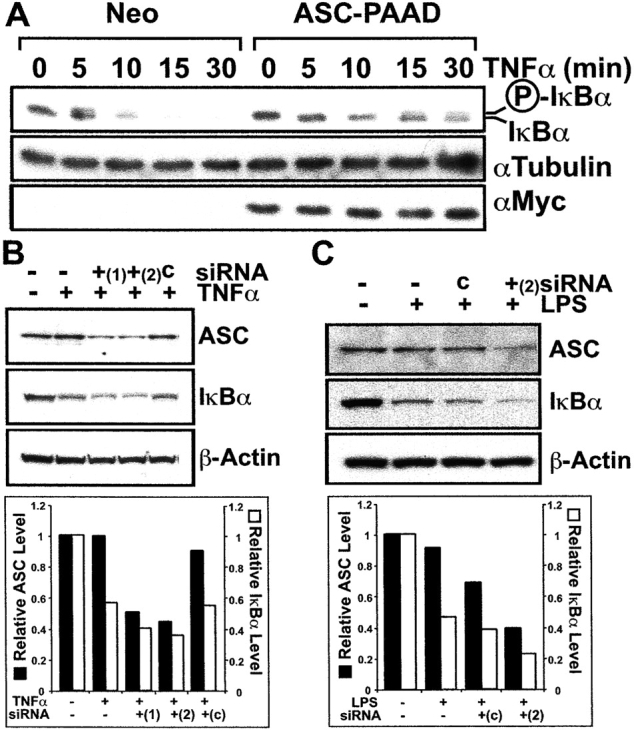

As IKK activity induces phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκB-family proteins, we evaluated the effects of the PAAD of ASC on levels of endogenous IκBα in these stably transfected cells, before and at various times after TNFα stimulation. Immunoblot analysis of lysates from HEK293N-Neo cells using anti-IκBα antibody demonstrated the appearance of a doublet band (indicative of phosphorylation of IκBα) within 5 min after TNFα simulation, followed by disappearance of IκBα protein. In contrast, IκBα protein levels were sustained at detectable levels in ASC-PAAD–expressing HEK293N cells despite TNFα treatment. Furthermore, the IκBα doublet band indicative of phosphorylation was not observed until much later, at 15–30 min after stimulation (Fig. 5 A), thus demonstrating a marked delay relative to control cells.

Figure 5.

ASC regulates IκBα levels. (A) Endogenous IκBα expression was analyzed by immunoblotting in stably transfected HEK293N-Neo or ASC-PAAD cells at various times following stimulation with TNFα. The position of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated IκBα proteins are indicated. (B) MCF7 cells were transfected on two consecutive days with two different double-strand ASC siRNAs (ASC nucleotides 721–741 [+1]; and nucleotides 474–494 [+2]) or control (c) siRNA using Oligofectamine. After 24 h, cells were either left untreated (−) or treated with 10 ng ml−1 TNFα for 10 min (+). Cell lysates were prepared, normalized for protein content, and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for ASC (top), IκBα (middle), or βActin (bottom). (C) TPA-differentiated THP-1 cells were transfected with ASC (ASC nucleotides 474–494 [+2]) or control (c) siRNA on two consecutive days, then stimulated the following day for 30 min with LPS. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting for ASC (top), IκBα (middle), or βActin (bottom). (B and C) Blots were also quantified by scanning-densitometry analysis of the autoradiograms, and are presented below the gel as a bar graph showing fold expression compared with uninduced cells, normalized to βActin expression as determined by immunoblotting.

Though the expression of the PAAD domain of ASC in cells interfered with IKK activation (Fig. 3) and IκBα degradation (Fig. 5 A) in response to proinflammatory stimuli, these results could reflect a dominant-negative effect of this protein domain. Consequently, the full-length ASC protein might operate as an agonist rather than antagonist of IKK activation. To explore the role of endogenous ASC, we used the technique of small interfering RNA (siRNA) to reduce ASC expression in cells, assessing the impact on TNFα- and LPS-mediated degradation of endogenous IκBα by immunoblotting (for a review, see reference 27). For these experiments, either a 19 bp double-strand RNA corresponding to ASC nucleotides 721–741, or to nucleotides 474–494 was introduced into either MCF7 epithelial cells or THP-1 monocytic cells. Both siRNAs directed against ASC mRNA substantially reduced ASC protein levels in MCF7 cells and siRNA (474–494) also to a lesser extent in differentiated THP-1 cells, while a control siRNA molecule (c) did not (Fig. 5, B and C). These experiments revealed that an average siRNA-mediated reduction in endogenous ASC protein levels of ∼60% was associated with enhanced IκBα degradation in cells stimulated with TNFα or LPS averaging ∼23% compared with control siRNA transfected cells. Thus, reductions of ASC were associated with enhanced signaling by TNFα and LPS, allowing us to conclude that endogenous ASC functions as a suppressor of the NF-κB pathway, at least in some cellular contexts.

Discussion

PAAD (PYRIN, Dapin) domains are found in multiple genes within the human genome, including several implicated in hereditary hyperinflammation syndromes, interferon responses, cancer suppression, and apoptosis induction (3). Certain PAADs are capable of homotypic interactions with themselves or other members of the PAAD family (20, 28, 29), suggesting opportunities for creating protein interaction networks that link various signaling pathways and permit fine-tuning of responses. Recently, the PAAD of ASC has been reported to bind the corresponding PAADs of Pyrin and Cryopyrin, which are encoded by the causative genes involved in Familial Mediterranean Fever and Familial Cold Autoinflammatory Syndrome, Muckle-Wells syndrome, and Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome, respectively (20, 28). Furthermore, ASC reportedly collaborates with Cyropyrin and PYPAF-7 in inducing NF-κB activity, at least in transient transfection experiments in HEK293T cells (20, 21), requiring overexpression of both ASC and these other PAAD-family proteins. However, as shown here, ASC does not collaborate with all PAAD-family proteins in inducing NF-κB activity, and its overexpression is associated with suppression rather than enhancement of NF-κB activity in cells stimulated with proinflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β) or LPS. Given our observation that the PAAD of ASC associates with and suppresses components of the IKK complex, it is possible that Cryopyrin interaction with ASC dislodges ASC from the IKKs, relieving endogenous suppression of these kinases, and permitting NF-κB activation. Alternatively, PAAD-containing proteins such as Cryopyrin, which are thought to self-oligomerize via a nucleotide-binding NACHT domain (30), might employ ASC as an adaptor for bridging to the IKK complex, achieving kinase activation through an induced proximity mechanism (31). The ultimate impact of ASC interactions with other PAAD-family proteins may therefore depend on their relative ratios, where ASC can function as either an inhibitor or activator of IKK, depending on cell context and on the stimulus used to engage pathways leading to the IKK complex.

We propose therefore that ASC is a dual modulator of NF-κB activation, which by virtue of its association with IKKs, acts at a point of convergence of multiple pathways leading to NF-κB induction. The ability of ASC to either enhance or inhibit NF-κB induction, depending presumably on the ratio of its levels relative to other ASC-binding proteins, is reminiscent of proteins such as c-FLIPL, which can function as either a pro-Caspase-8 activator or inhibitor, dependent on cell context (32). Similarly, some IAP-family proteins can either enhance or inhibit NF-κB induction by TNFα, depending apparently on whether they induce degradation of certain associated proteins (33, 34), but a combination of both stimulatory and inhibitory properties has not been attributed thus far to a single protein (e.g., cIAP1 inhibits; cIAP2 enhances). Thus, ASC may represent the first identified protein that has dual properties as both an inhibitor and enhancer of NF-κB induction. Though other interpretations are possible, this two-sided nature of ASC is entirely consistent with its hypothesized role as a molecular bridge involved in assembly of multiprotein complexes (molecular machines), in which the correct stoichiometry of components would be necessary for activity and where either insufficiency or excess of ASC could interfere with complex assembly.

Evidence is presented here that ASC associates with components of the IKK complex, the kinase complex responsible for phosphorylation of the IκB family proteins that sequester NF-κB in the cytosol (for a review, see reference 35). In pilot experiments, we could not demonstrate interaction of ASC with constituents of the IKK complex by ectopic overexpression of ASC with epitope-tagged IKKα, IKKβ, or IKKγ individually, as determined by coIP experiments (unpublished data). Thus, we favor the idea that ASC associates directly or indirectly with the assembled IKK complex. However, ectopic overexpression of single components of the IKK complex might disrupt the complex because of changes in protein stoichometry, thus preventing ASC binding. Interestingly, Chen et al. recently demonstrated the existence of several additional proteins associated with endogenous IKK complexes (36). It remains to be determined whether ASC associates with IKK complexes through one of these proteins. Also, the molecular events that govern physical and functional interactions of ASC with the IKK complex remain to be clarified, including the possible role of posttranslational modifications of ASC or other associated proteins. Thus, it is unclear at present how the PAAD of ASC suppresses IKK activation in response to proinflammatory stimuli.

Recently, we determined that another PAAD-family protein, PAN2, can also associate with IKKα and suppress IKKα activation by TNFα (19). Interestingly, however, PAN2 does not appear to associate with IKKβ or IKKγ, suggesting the possibility of differences in interactions with IKK complex components compared with ASC, which could be coimmunoprecipitated with either anti-IKKα or anti-IKKβ antibodies. Similar to ASC, however, the PAAD of PAN2 is sufficient for interactions with and suppression of IKKα (19).

Though we used the PAAD domain of ASC as a probe to demonstrate the ability of this region of ASC to functionally and physically interact with IKK complex components, it should be noted that the human genome contains at least two genes predicted to encode PAAD-only proteins (reference 3, and unpublished data), which are analogous to the ASC-PAAD protein employed here in our studies. Furthermore, we have observed that these proteins function very similar to the PAAD of ASC in their effects on IKK and NF-κB induction (unpublished data). Some poxviruses also contain potential ORFs encoding proteins with significant sequence similarity to cellular PAADs, such as the rabbit myxoma virus. Thus, endogenous and viral proteins consisting of only the PAAD domain may operate as negative regulators of IKK activation, analogous to our studies of a fragment of ASC comprising only the PAAD domain. Just as the mechanism by which ASC suppresses IKK activation induced by proinflammatory stimuli is presently unknown, similarly, it remains unclear how ASC enhances NF-κB induction when coexpressed with PAAD-family proteins such as Pyrin, (this paper), Cyropyrin (20), and PYPAF-7 (21). ASC has been reported to recruit Pyrin, Cryopyrin, and PYPAF-7 into cytosolic specks (20, 21, 28), suggesting a role for these intracellular bodies in the process of NF-κB induction, but the location of IKK complex proteins under these circumstances has not been assessed. Future studies should therefore address the consequences of Pyrin, Cryopyrin, and PYPAF-7 protein interactions with ASC with regards to association with and regulation of the IKK complex.

Interestingly, ASC associates with uncharacterized structures in the cytosol of cells, forming specks. The formation of speck-like structures is not merely an artifact of protein overexpression, because they can be identified by immunohistochemical techniques in normal tissue (17), and because certain treatments of cultured cells can induce speck formation by endogenous ASC (15). Indeed, the endogenous ASC protein was first discovered because of its association with Triton X-100–insoluble aggregates in HL-60 cells pretreated with retinoic acid (15). The targeting of ASC to these locations requires the combination of PAAD and CARD (unpublished data), and truncation mutants of ASC containing only the PAAD form filament-like structures in the cytosol of cells, but fail to produce the speck-like morphology for which this protein was named. In ASC-PAAD–expressing cells, IKK components colocalized with these filaments, which form in a manner reminiscent of previously identified NF-κB regulators, such as TRADD, RIP, and Bcl-10 (37, 38). Given recent suggestions that the ASC-binding protein Pyrin associates with cytoskeletal proteins, it is tempting to speculate the ASC may associate with or coordinate formation of a specialized site on the cytoskeleton (39). The fate of proteins recruited to these uncharacterized complexes where ASC localizes is unknown. We have seen no evidence that ASC overexpression results in degradation of ASC-interacting proteins. Possibly speck-like structures targeted by ASC are sites for posttranslation protein modifications or simply providing a location for sequestering certain proteins.

ASC was originally reported to induce apoptosis when overexpressed in certain tumor lines (15, 24). However, at the doses of ASC-encoding plasmid employed and levels of ASC expression attained in our experiments, we did not observe apoptosis. Based on our findings, we propose that ASC might modulate apoptosis under some circumstances where NF-κB is important for avoiding cell death, given that NF-κB can regulate expression of apoptosis-relevant genes such as A20, Bcl-XL, Bfl-1, cIAP2, and others (for a review, see reference 40). In this regard, inhibition of IKKs is known to sensitize cells to apoptosis induction by TNF-family death ligands (41). These effects of ASC on apoptosis might account for the observation that this gene is commonly silenced in breast cancers by gene methylation (16).

Because expression of ASC is initially low but inducible by LPS and TNFα in THP-1 monocytic cells, we speculate that ASC may be involved in a negative feedback suppression of pathways that induce NF-κB. This inducible expression in response to a variety of proinflammatory stimuli was also recently demonstrated in neutrophils (42). In this way, ASC could play a role in terminating inflammatory responses, thus ensuring that only a short burst of NF-κB activity activation occurs. This scenario is consistent with our siRNA results where reductions in ASC were correlated with enhanced IκBα degradation. An alternative but not mutually exclusive possibility is that antagonism of the TNFα, IL-1β, and LPS pathways for NF-κB induction by ASC reflects a competition between alternative pathways for access to IKK or IKK-associated proteins. In this regard, the physiological or pathogenic stimuli that normally engage ASC and other PAAD-family proteins in NF-κB induction are unknown, but at least 14 members of the PAAD family have been identified that contain leucine rich repeats (LRRs) similar to those found in the extracellular domains of Toll-related receptors (TLRs) and in the CARD-family proteins Nod1 and Nod2, which are known to bind bacterial LPS or other molecules made by microbial pathogens. Thus, while speculative, many PAAD-family proteins may participate in a pathway that senses intracellular bacteria. Cross talk between this pathway and other NF-κB activation pathways, such as those triggered by TNFα, IL-1β, TLRs, and antigen receptors (TCR, BCR), may play important roles in steering innate and acquired immune responses toward different ultimate outcomes. Future studies, including targeted ablation of the gene encoding ASC in mice, will reveal the overall importance of ASC in inflammation and innate immunity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. H. Chan, J.S. Damiano, Y. Kim, and J.M. Zapata for discussions, A. Stassinopoulos for excellent technical support, D. Chaplin, M. Karin, J. Tschopp, and J. Yuan for valuable reagents, and acknowledge J. Valois and R. Cornell for manuscript preparation.

C. Stehlik and L. Fiorentino are recipients of fellowships from the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF, J1809-Gen/J1990-Gen), Department of Defense (DOD) Breast Cancer Research Program (DAMD17-01-1-0171), and the American-Italian Cancer Foundation, respectively.

C. Stehlik and L. Fiorentino contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a Caspase recruitment domain; coIP, coimmunoprecipitation; CARD, Caspase-recruitment domain; DDF, death domain fold; EMSA, electromobility gel-shift assays; GFP, green fluorescent protein, GST, glutathionine-S-transferase; IκB, inhibitor of NF-κB; IKK, IκB kinase; NF, nuclear factor; PAAD, Pyrin, AIM, ASC, and death domain like; PAN, PAAD and NACHT containing protein.

References

- 1.Aravind, L., V.M. Dixit, and E.V. Koonin. 1999. The domains of death: evolution of the apoptosis machinery. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber, C.H., and C. Vincenz. 2001. The death domain superfamily: a tale of two interfaces? Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawlowski, K., F. Pio, Z.-L. Chu, J.C. Reed, and A. Godzik. 2001. PAAD-a new protein domain associated with apoptosis, cancer and autoimmune diseases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:85–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertin, J., and P.S. DiStefano. 2000. The PYRIN domain: a novel motif found in apoptosis and inflammation proteins. Cell Death Differ. 7:1273–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairbrother, W.J., N.C. Gordon, E.W. Humke, K.M. O'Rourke, M.A. Starovasnik, J.-P. Yin, and V.M. Dixit. 2001. The PYRIN domain: a member of the death domain-fold superfamily. Protein Sci. 10:1911–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Staub, E., E. Dahl, and A. Rosenthal. 2001. The DAPIN family: a novel domain links apoptotic and interferon response proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinon, F., K. Hofmann, and J. Tschopp. 2001. The pyrin domain: a possible member of the death domain-fold family implicated in apoptosis and inflammation. Curr. Biol. 11:R118–R120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karin, M., and M. Delhase. 2000. The I kappa B kinase (IKK) and NF-kappa B: key elements of proinflammatory signalling. Semin. Immunol. 12:85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman, N., and T. Maniatis. 2001. NF-κB signaling pathways in mammalian and insect innate immunity. Genes Dev. 15:2321–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Consortium, T.F.F. 1997. A candidate gene for familial mediterranean fever. Nat. Genet. 17:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman, H.M., J.L. Mueller, D.H. Broide, A.A. Wanderer, and R.D. Kolodner. 2001. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat. Genet. 29:301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldmann, J., A.M. Prieur, P. Quartier, P. Berquin, E. Cortis, D. Teillac-Hamel, and A. Fischer. 2002. Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome is caused by mutations in CIAS1, a gene highly expressed in polymorphonuclear cells and chondrocytes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71:198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu, Z.-L. F. Pio, Z. Xie, K. Welsh, M. Krajewska, S. Krajewski, A. Godzik, and J.C. Reed. 2001. A novel enhancer of the Apaf1 apoptosome involved in cytochrome c-dependent caspase activation and apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 276:9239–9245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hlaing, T., R.F. Guo, K.A. Dilley, J.M. Loussia, T.A. Morrish, M.M. Shi, C. Vincenz, and P.A. Ward. 2001. Molecular cloning and characterization of DEFCAP-L and -S, two isoforms of a novel member of the mammalian Ced-4 family of apoptosis proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 276:9230–9238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masumoto, J., S. Taniguchi, K. Ayukawa, H. Sarvotham, T. Kishino, N. Niikawa, E. Hidaka, T. Katsuyama, T. Higuchi, and J. Sagara. 1999. ASC, a novel 22-kDa protein, aggregates during apoptosis of human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33835–33838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conway, K.E., B.B. McConnell, C.E. Bowring, C.D. Donald, S.T. Warren, and P.M. Vertino. 2000. TMS1, a novel proapoptotic caspase recruitment domain protein, is a target of methylation-induced gene silencing in human breast cancers. Cancer Res. 60:6236–6242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masumoto, J., S.-I. Taniguchi, J. Nakayama, M. Shiohara, E. Hidaka, T. Katsuyama, S. Murase, and J. Sagara. 2001. Expression of apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain, a Pyrin N-terminal homology domain-containing protein, in normal human tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 49:1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiDonato, J.A. 2000. Assaying for I kappa B kinase activity. Methods of Enzymology. J.C. Reed, editor. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. 393–400. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Fiorentino, L., C. Stehlik, V. Oliveira, M.E. Ariza, A. Godzik, and J.C. Reed. 2002. A novel PAAD-containing protein that modulates NF-κB induction by cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 277:35333–35340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manji, G.A., L. Wang, B.J. Geddes, M. Brown, S. Merriam, A. Al-Garawi, S. Mak, J.M. Lora, M. Briskin, M. Jurman, et al. 2002. PYPAF1: A PYRIN-containing Apaf1-like protein that assembles with ASC and regulates activation of NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 277:11570–11575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, L., G.A. Manji, J.M. Grenier, A. Al-Garawi, S. Merriam, J.M. Lora, B.J. Geddes, M. Briskin, P.S. DiStefano, and J. Bertin. 2002. PYPAF7: a novel PRYIN-containing Apaf1-like protien that regulates activation of NF-κB and Caspase-1-dependent cytokine processing. J. Biol. Chem. 277:29874–29880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruland, J., G.S. Duncan, A. Elia, I. del Barco Barrantes, L. Nguyen, S. Plyte, D.G. Millar, D. Bouchard, A. Wakeham, P.S. Ohashi, and T.W. Mak. 2002. Bcl10 is a positive regulator of antigen receptor-induced activation of NF-κB and neural tube closure. Cell. 104:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inohara, N., Y. Ogura, F.F. Chen, A. Muto, and G. Nuñez. 2000. Human Nod1 confers responsiveness to bacterial lipopolysaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 275:27823–27831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McConnell, B.B., and P.M. Vertino. 2000. Activation of a caspase-9-mediated apoptotic pathway by subcellular redistribution of the novel caspase recruitment domain protein TMS1. Cancer Res. 60:6243–6247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpentier, I., and R. Beyaert. 1999. TRAF1 is a TNF inducible regulator of NF-kappaB activation. FEBS Lett. 460:246–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voraberger, G., R. Schafer, and C. Stratowa. 1991. Cloning of the human gene for intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and analysis of its 5′-regulatory region. Induction by cytokines and phorbol ester. J. Immunol. 147:2777–2786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannon, G.J. 2002. RNA interference. Nature. 418:244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richards, N., P. Schaner, A. Diaz, J. Stcukey, E. Shelden, A. Wadhwa, and D.L. Gumucio. 2001. Interaction between Pyrin and the apoptotic speck protein (ASC) modulates ASC-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 276:39320–39329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masumoto, J., S. Taniguchi, and J. Sagara. 2001. Pyrin N-terminal homology domain- and caspase recruitment domain-dependent oligomerization of ASC. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 280:652–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koonin, E.V., and L. Aravind. 2000. The NACHT family-a new group of predicted NTPases implicated in apoptosis and MHC transcription activation. Trends Biol. Sci. 25:223–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulze-Osthoff, K., and C. Stroh. 2000. Induced proximity model attracts NF-kappaB researchers. Cell Death Differ. 7:1025–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang, D.W., Z. Xing, Y. Pan, A. Algeciras-Schimnich, B.C. Barnhart, S. Yaish-Ohad, M.E. Peter, and X. Yang. 2002. c-FLIPL is a dual function regulator for caspase-8 activation and CD95-mediated apoptosis. EMBO J. 21:3704–3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, X., Y. Yang, and J.D. Ashwell. 2002. TNF-RII and c-IAP1 mediate ubiquitination and degradation of TRAF2. Nature. 416:345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu, Z.L., T.A. McKinsey, L. Liu, J.J. Gentry, M.H. Malim, and D.W. Ballard. 1997. Suppression of tumor necrosis factor-induced cell death by inhibitor of apoptosis c-IAP2 is under NF-κB control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:10057–10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karin, M., and A. Lin. 2002. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat. Immunol. 3:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen, G., P. Cao, and D.V. Goeddel. 2002. TNF-induced recruitment and activation of the IKK complex require Cdc37 and Hsp90. Mol. Cell. 9:401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guiet, C., and P. Vito. 2000. Caspase recruitment domain (CARD)-dependent cytoplasmic filaments mediate bcl10-induced NF-kappaB activation. J. Cell Biol. 148:1131–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inada, H., I. Izawa, M. Nishizawa, E. Fujita, T. Kiyono, T. Takahashi, T. Momoi, and M. Inagaki. 2001. Keratin attenuates tumor necrosis factor-induced cytotoxicity through association with TRADD. J. Cell Biol. 155:415–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mansfield, E., J.J. Chae, H.D. Komarow, T.M. Brotz, D.M. Frucht, I. Aksentijevich, and D.L. Kastner. 2001. The familial Mediterranean fever protein, pyrin, associates with microtubules and colocalizes with actin filaments. Blood. 98:851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reed, J.C. 2002. Apoptosis-based therapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1:111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Antwerp, D.J., S.J. Martin, I.M. Verma, and D.R. Green. 1998. Inhibition of TNF-induced apoptosis by NF-kappa B. Trends Cell Biol. 8:107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiohara, M., S. Taniguchi, J. Masumoto, K. Yasui, K. Koike, A. Komiyama, and J. Sagara. 2002. ASC, which is composed of a PYD and a CARD, is up-regulated by inflammation and apoptosis in human neutrophils. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293:1314–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]