Abstract

Recent clinical evidence demonstrated the importance of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in the development of Crohn's disease. A mouse model for this pathology has previously been established by engineering defects in the translational control of TNF mRNA (Tnf Δ AREmouse). Here, we show that development of intestinal pathology in this model depends on Th1-like cytokines such as interleukin 12 and interferon γ and requires the function of CD8+ T lymphocytes. Tissue-specific activation of the mutant TNF allele by Cre/loxP-mediated recombination indicated that either myeloid- or T cell–derived TNF can exhibit full pathogenic capacity. Moreover, reciprocal bone marrow transplantation experiments using TNF receptor–deficient mice revealed that TNF signals are equally pathogenic when directed independently to either bone marrow–derived or tissue stroma cell targets. Interestingly, TNF-mediated intestinal pathology was exacerbated in the absence of MAPKAP kinase 2, yet strongly attenuated in a Cot/Tpl2 or JNK2 kinase–deficient genetic background. Our data establish the existence of redundant cellular pathways operating downstream of TNF in inflammatory bowel disease, and demonstrate the therapeutic potential of selective kinase blockade in TNF-mediated intestinal pathology.

Keywords: MAPK/SAPK, targeted mutants, CD8+ lymphocytes, apoptosis, intestine

Introduction

The correlation between aberrant cytokine activity and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)*has been exemplified in several animal models for this disease via the use of specific neutralizing antibodies or cytokine gene knockouts (1). In the majority of IBD models, TNF appears as a common pathogenic denominator despite the variability of the instigating stimuli or genetic defects leading to the development of the disease (2–7). Recent clinical trials showed that anti-TNF antibodies provide marked clinical benefits in human Crohn's disease patients (8). However, despite such strong indications for a pathogenic relevance of TNF in IBD, the specific molecular and cellular mechanisms driving TNF-dependent disease remain poorly defined.

The activities of TNF in oligo-cellular systems and in modeled immunological responses are now well understood and the signals transduced by the two TNF receptors (TNFRI and TNFRII) have been sufficiently detailed (9). Current knowledge indicates that this molecule exhibits multiple in vivo activities. It might be predicted that TNF disturbs innate and adaptive immunoregulatory interplays in the intestine to alleviate the state of tolerance and lead to inappropriate responses to both nominal bacterial antigens and to self (10). The potent innate inflammatory activities of TNF appear central to disease induction and progression, particularly when sustained TNF overproduction is provoked. The activation of endothelial cells, induction of chemokines, and recruitment of neutrophils in the gut mucosa induced by TNF may directly affect intestinal homeostasis and provoke disease (11). The capacity of monocytes/macrophages from patients with IBD to hyper respond to bacterial products and to secrete inflammatory mediators, including TNF, correlates with disease progression (12), although evidence for the aetiopathogenic role of this response is currently missing. Evidence for direct effects of TNF on tissue stroma cell types, like intestinal epithelial cells (13), is also available and may offer alternative mechanisms for pathogenic contributions. Recent evidence indicated a role for proinflammatory cytokines, like IL-6 and IL-12, in inducing resistance of pathogenic lymphocytes to antigen-induced cell death and driving their accumulation in the intestine (14). TNF may also promote or suppress the adaptive immune response. Several studies suggest that TNF/TNFRs affect T cell proliferation, activation, cytotoxicity, the antigen-induced cell death of cytotoxic T cells, and the attenuation of TCR signaling (15). The capacity of TNF to modulate adaptive immune responses was most profoundly revealed by its role in suppressing organ-specific or systemic autoimmune disease (15, 16). Therefore, it is probable that TNF supports pathogenesis of IBD at multiple levels by not only targeting innate compartments or nonimmune cell types but also by modulating the adaptive immune response. The specific contribution of such mechanisms in the development of TNF-mediated IBD awaits detailed investigation.

Several existing animal models of mucosal inflammation have indicated the potential key role of an excessive Th1 cytokine response and of CD4+ effector T cells in the pathology of IBD (1). Amongst Th1-driven cytokine responses, those dependent on TNF have lately received much attention due to the success of anti-TNF treatments of IBD in humans. The recent generation of a mouse developing Crohn's-like IBD due to an induced intrinsic defect in the posttranscriptional regulation of TNF mRNA (Tnf Δ AREmouse) offered a unique animal model for the detailed study of TNF-driven disease mechanisms (5). In this study we aimed to establish cellular and molecular hierarchies operating during pathology in the Tnf Δ AREmouse with the ultimate goal to uncover disease mechanisms and indicate novel targets for therapy. We demonstrate that TNF initiates different and redundant cellular cascades that contribute to IBD development. Interestingly, the pathogenic capacity of these redundant cascades relies exclusively on the generation by TNF of an IL-12– and IFN-γ–driven Th1-like response and on the activation of a pathogenic CD8+ T cell compartment, the latter being an important feature of human Crohn's IBD represented uniquely in the Tnf Δ AREmouse model. Analysis of the potential pathogenic significance of effector kinase signals operating downstream of TNF in the Tnf Δ AREmodel identified Cot/Tpl2 and JNK2 kinases as dominant players in the pathogenesis of IBD and revealed an antiinflammatory role played by MAPKAP kinase 2 (MK2).

Materials and Methods

Mice.

The generation of Tnf Δ ARE, Tnf Δ AREneo, Tnf Δ ARE TnfRI−/−(5), MAPKAP K-2 (17), Jnk2 (18), Tpl-2 (19), and LysM Cre (20) mice has been previously described. TnfRI- (21), CD4- (22), β2M- (23), IL-12p40- (24), IFNγ- (25), μMT- (26), and TcRδ- (27) deficient mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Double TnfRI- and TnfRII-deficient mice (TnfRI/RII − / −), as well as triple compound mutants Tnf Δ ARETnfRI− / − TnfRII − / − (Tnf Δ ARETnfRI/II −/−), were generated by breeding TnfRI − / − and Tnf Δ ARETnfRI− / − into a TnfRII-deficient background (28). The transgenic Lck-Cre (29) mice were provided by J.D. Marth, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA. All mice were bred and maintained on a mixed C57BL/6J×129S6 genetic background in the animal facilities of the Biomedical Sciences Research Center “Alexander Fleming” under specific pathogen-free conditions.

Histological and Immunocytochemical Assessment of Inflammation.

Paraffin-embedded intestinal tissue samples were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and two 1.5-cm sections of ileum were histologically evaluated in a blinded fashion. Acute and chronic inflammation were assessed separately in a minimum of eight high power fields (hpf) using a semiquantitative (0–4+) scoring system as follows: acute inflammatory score, 0 = 0–1 polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells per hpf (PMN/hpf); 1 = 2–10 PMN/hpf within mucosa; 2 = 11–20 PMN/hpf within mucosa; 3 = 21–30 PMN/hpf within mucosa or 11–20 PMN/hpf with extension below muscularis mucosae; and 4 = >30 PMN/hpf within mucosa or >20 PMN/hpf with extension below muscularis mucosae. Chronic inflammatory score, 0 = 0–10 mononuclear leukocytes (ML) per hpf (ML/hpf) within mucosa; 1 = 11–20 ML/hpf within mucosa; 2 = 21–30 ML/hpf within mucosa or 11–20 ML/hpf with extension below muscularis mucosae; 3 = 31–40 ML/hpf within mucosa or 21–30 ML/hpf with extension below muscularis mucosa or follicular hyperplasia; and 4 = >40 ML/hpf within mucosa or >30 ML/hpf with extension below muscularis mucosae or follicular hyperplasia. Total disease score per mouse was calculated by the summation of the acute inflammatory or chronic inflammatory scores for each mouse (data represented as mean ± SD). For immunocytochemistry, frozen cryostat sections were fixed in acetone (BDH) and after rehydration were stained with anti–CD4-FITC, anti–CD8-PE, anti–CD11b FITC, anti–B220-PE, and anti–Gr-1 biotin followed by streptavidin-PE (BD Biosciences) and then analyzed via immunofluorescent microscopy.

In Situ Detection of Lamina Propria Mononuclear Cell (LPMC) Apoptosis via Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase–mediated, dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) Assay.

TUNEL assays were performed on paraffin-embedded ileal sections from 3-mo-old mice (n ≤ 3 mice/group). After deparaffinization and rehydration, sections were treated with pepsin-HCL (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min. Next, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated incorporation of digoxigenin-labeled dUTP (Roche) was performed by applying the reaction mixture in tailing buffer (Roche) for 1 hr at 60°C. Apoptotic cells were detected using alkaline phosphatase–conjugated sheep anti–digoxigenin Fab fragments (Roche) and the Vector ABC and Fast Blue kits (Vector Laboratories). Sections were counterstained with nuclear red (Vector Laboratories). For quantitation of LPMCs, four photomicrographs/section were acquired at hpf ×200 and were analyzed with the Corel Photopaint (Corel) software using a 4 × 5 grid. The area between the epithelial cells and the muscularis (as indicated by the nuclear red counter stain) was scanned for the total number of LPMCs present and the number of apoptotic cells per hpf were quantified. The apoptotic index was calculated from the corresponding values as the percentage of apoptotic cells per total number of LPMCs.

Immunostaining and Flow Cytometry.

Spleens were collected from 4- or 8-wk-old normal and mutant mice. After erythrocyte lysis, 106 single cell suspensions were stained at 4°C for 30 min with the corresponding antibodies in PBA (PBS, 3% FBS, 0.1% NaN2) and analyzed on a Coulter EPICS Elite flow cytometer. Anti–CD4-FITC, anti-CD4 CyChrome, anti–CD8-PE, anti-CD8 CyChrome, anti–CD25-PE, anti-CD69 biotin, anti–CD11b FITC, and anti-CD45RB biotin followed by streptavidin-PE (BD Biosciences) were used.

Cell Isolation and Culture.

All cultures were grown and maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2. Total exudate peritoneal macrophages were isolated by peritoneal lavage from ≤10-wk-old mice 3 d after a single peritoneal injection of aged 4% thioglycollate broth (1 ml; Difco Laboratories). Splenocytes were collected from 1-mo-old nondiseased Tnf Δ ARE/ + and littermate controls. After erythrocyte lysis, spleen cells were used as they were or enriched for T cells after nylon wool treatment, or enriched for B cells after anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 and complement lysis of T cells. For cytokine determination assays, cells were plated at 5 × 105 cells (for macrophages) or 5 × 106 cells (for lymphocytes) onto 24-well plates and stimulated with LPS (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-CD3 (BD Biosciences), or pockweed mitogen (Sigma-Aldrich). After a 12–24-h incubation, supernatants were collected and analyzed using specific ELISAs.

Cytokine and Nitric Oxide (NO) Determination Assays.

TNF and IL-6 levels in culture supernatants were determined using a sandwich TNF (5) and mIL-6 (Endogen) ELISAs. To evaluate NO, NO3 − and NO2 − were measured from cell culture supernatants using a standard Griess assay.

Mixed Lymphocyte Reactions and Assessment of CTL Activity.

The cytotoxic activity of spleen cells to lyse epithelial cells was evaluated using the syngeneic (H-2b) colonic epithelial cell line CMT-93 as target. CMT-93 cells were first pulsed with [3H]thymidine for 24 h in RPMI + 5% FBS medium and then treated with 2 μg/ml mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min to arrest cell growth. After washes, cells were plated onto 96-well tissue culture plates in triplicates (104 per well) and incubated with effector cells at different E/T ratios (1:1 to 100:1) in 0.2 ml complete medium. After incubation for 12 h, the plates were washed three times with PBS to remove nonadherent cells. The remaining radioactivity present in target cells was measured using a gamma counter.

Bone Marrow Transplantation.

Bone marrow from 8-wk-old mutant and wild-type (B6,129) female mice was obtained from femurs and tibia. 107 bone marrow cells in 200 μls were injected intravenously into lethally irradiated (1,000 rads) female (B6,129) mice. Mice were maintained in isolated/specific pathogen-free conditions and kept on an antibiotic regime for 2 wk. Reconstitution was assessed via specific staining for CD4/CD8, B220, CD11b, and Gr-1 antigens via FACS® analysis of heparinized blood samples. Mouse body weight was assessed weekly. At the end of the study, spleen cells were isolated for TNF measurements and DNA detection of the ΔARE mutation using Southern analysis. For the engraftment of Tnf + / + bone marrow into Tnf Δ ARE/ + hosts, 2-wk-old Tnf Δ ARE/ + female mice were treated weekly with 600 μg anti-TNF antibody (TN3. 9-12.γ1; Celltech) until the age of 7.5 wk old to prevent IBD development. Mice were irradiated and reconstituted with Tnf + / + bone marrow as described above and were kept with decreasing doses of antibody until reconstituting hemopoietic cells appeared in peripheral blood (3 wk). Mice were then left untreated for 9 more wk to assess for the development of the disease relative to nonirradiated Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice that followed the same antibody treatment regime.

Results

TNF-driven IBD Requires the Effector Function of Non-γδTCR CD8+ T Cells and Is Dependent on IL-12 and IFN-γ.

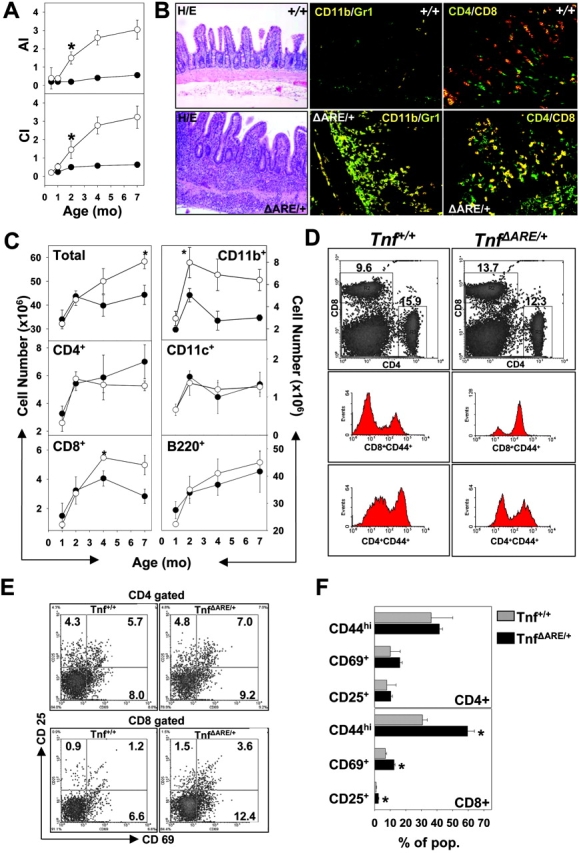

We have previously reported that a targeted mouse mutant bearing a deletion in the 3′ AU-rich elements (AREs) of TNF mRNA (Tnf Δ AREmice) overproduces TNF and develops a unique IBD phenotype with remarkable histopathological similarity to Crohn's disease (5). In this model, IBD develops between 4–8 wk of age (Fig. 1 A; reference 5) and is restricted to the terminal ileum (Fig. 1 B) and occasionally to the proximal colon (5). Its basic histopathological characteristics include villus blunting and submucosal inflammation with prevailing PMN/macrophage and lymphocytic exudates, proceeding to patchy transmural inflammation and the appearance of lymphoid aggregates and rudimentary granulomata (Fig. 1 B; reference 5). We have previously demonstrated that intestinal pathology in this model is dependent on the presence of mature lymphocytes (e.g., in Tnf ΔARE Rag-1 −/− mice; Table I and reference 5), which suggests that TNF deregulation perturbs adaptive immune responses to support the development of IBD. During the course of our analysis we noted that the development of the Tnf ΔARE IBD phenotype correlated with the development of mild splenomegaly, which follows the course of the disease (Fig. 1, A and C) and becomes significant at 4 mo of age. Flow immunocytometric analyses indicated that the increase in total splenocyte counts noted past the age of 2 mo correlated with significant increases in CD11b+ myeloid cells and CD8+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 1 C). Notably, expression of the CD44, CD69, and CD25 markers was enhanced in Tnf Δ ARE/ + CD8+ lymphocytes, indicating that these cells are in an activated/memory state (Fig. 1, D–F). In sharp contrast, the corresponding CD4+ T cell populations appeared similar to the control groups up to 4 mo of age (Fig. 1, D–F), although a slight increase in corresponding memory compartments was detected past the age of 7 mo (not depicted).

Figure 1.

Development of TNF-mediated IBD correlates with the systemic activation of CD8+ T cell effectors. (A) Graphical representation of acute (AI) and chronic (CI) inflammatory indices calculated from the histopathological evaluation of Tnf Δ ARE/ + (○) and Tnf + / + control (•) ileal sections, indicating the course of ileitis development. (B) Representative histological analysis for the detection of total exudates as well as immunocytochemical analysis for the detection of CD11b+/Gr-1+ (myeloid) and CD4+/CD8+ (T lymphocytic) cells in the ileal sections of 3-mo-old Tnf + / + and Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice. H/E, hematoxylin and eosin staining. ×100 and ×200, respectively. (C) Age-dependent variation of the splenocyte cellular content in lymphocytes, myeloid, and dendritic cells in Tnf Δ ARE/ + (○) and Tnf + / + control (•) after the flow cytometric detection of the corresponding populations. Data represents absolute values (± SD) collected from 5–15 mice per group. *, values with significant statistical differences (P < 0.05). (D) Representative density and histogram plots after the flow cytometric detection of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations (right) in the spleens of 4-mo-old Tnf + / + and Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice and detection of memory marker CD44 on CD4+/CD8+ gated lymphocytes. (E) Representative density plots for the activation markers CD69 and CD25 on CD4+/CD8+ gated Tnf Δ ARE/ + and control splenocytes. (F) Graphical representation of estimated percentages for CD44, CD69, and CD25 on CD4+/CD8+ gated Tnf Δ ARE/ + and control splenocytes. Histogram values derived from percentages of cells in the corresponding quadrants. Data (values ± SD) collected from 15 mice per group at the age of 4 mo. *, values with significant statistical differences (P < 0.05).

Table I.

Effect of Selective Deletion of Adaptive Mediators on the Incidence and Severity of TnfΔARE Crohn's Ileitis

| Mouse genotype

|

|

|

Disease Score DistributionaIleum

|

Mean disease scorea

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

0–0.5

|

0.5–1

|

1–2

|

2–3

|

|

| TnfΔARE/+ Rag-1+/− | n = 10b | AI | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1.67 ± 0.68 |

| CI | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1.60 ± 0.52 | ||

| TnfΔARE/+ Rag-1−/− | n = 10b | AI | 6 | 4 | 0.70 ± 0.25d | ||

| CI | 7 | 3 | 0.65 ± 0.24d | ||||

| TnfΔARE/+ mMT+/− | n = 9b | AI | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1.02 ± 0.90 | |

| CI | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1.22 ± 0.66 | ||

| TnfΔARE/+ mMT−/− | n = 10b | AI | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.12 ± 0.85 |

| CI | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1.45 ± 0.79 | ||

| TnfΔARE/+ CD4+/− | n = 8b | AI | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2.00 ± 0.83 |

| CI | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2.06 ± 1.11 | ||

| TnfΔARE/+ CD4−/− | n = 10b | AI | 1 | 9 | 3.00 ± 0.52d | ||

| CI | 1 | 9 | 2.80 ± 0.34d | ||||

| TnfΔARE/+ b2M+/− | n = 7c | AI | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.87 ± 0.46 |

| CI | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2.00 ± 0.89 | |||

| TnfΔARE/+ b2M−/− | n = 9c | AI | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0.74 ± 0.55d | |

| CI | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0.77 ± 0.46d | |||

| TnfΔARE/+ TcRδ1/2 | n = 7c | AI | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.64 ± 1.02 |

| CI | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1.82 ± 0.83 | |||

| TnfΔARE/+ TcRδ2/2 | n = 11b | AI | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1.84 ± 0.95 |

| CI | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 1.95 ± 0.82 | ||

| TnfΔARE/+ il-12+/− | n = 6c | AI | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.95 ± 0.55 | |

| CI | 5 | 1 | 2.08 ± 0.49 | ||||

| TnfΔARE/+ il-12−/− | n = 10c | AI | 5 | 5 | 0.67 ± 0.33d | ||

| CI | 1 | 8 | 1 | 0.90 ± 0.37d | |||

| TnfΔARE/+ Ifnγ1/2 | n = 6c | AI | 1 | 5 | 2.66 ± 0.40 | ||

| CI | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2.75 ± 0.41 | |||

| TnfΔARE/+ Ifnγ2/2 | n = 7c | AI | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.64 ± 0.74d | |

| CI | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 ± 0.57d | |||

AI, acute inflammatory index; CI, chronic inflammatory index.

Mean severity of inflammatory lesions (refer to Materials and Methods for a description of histologic analysis).

Mice and littermate controls at the age of

2–3 and

3–4 mo.

A significant difference to corresponding control group score (assessed by using unpaired Student's t test).

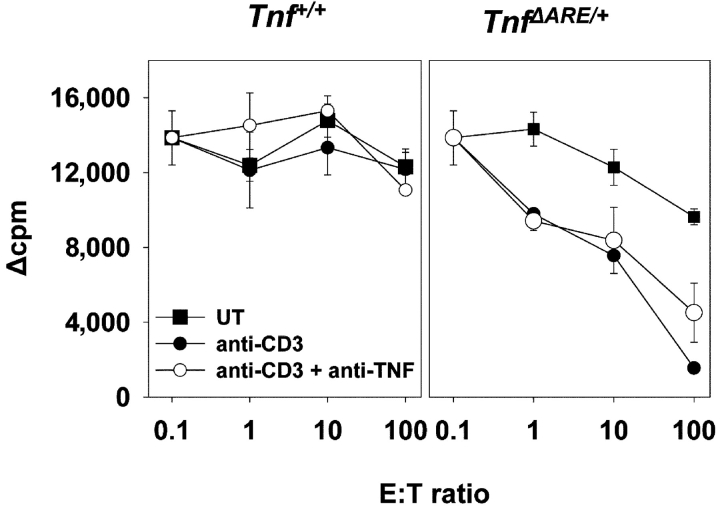

Examination of the CTL effector activity in Tnf ΔARE/+ cultures from inflamed animals by means of measuring the ability of Tnf Δ ARE/ + splenocytes to lyse syngeneic (H-2b) CMT-93 cell targets in vitro, revealed that Tnf Δ AREsplenocytes exhibited a high degree of target cell lysis at E/T ratios as low as 10 (Fig. 2 B). Interestingly, the observed target cytolysis was not mediated by TNF because it could not be blocked by anti-TNF antibody treatment (Fig. 2 B). When examined in allogeneic (BALB/c, H-2d) MLRs, Tnf Δ ARE/ + splenocytes (H-2b) from 4-wk-old, disease-free animals showed significantly enhanced proliferation compared to Tnf + / + controls, even at low doses of alloantigen (not depicted). The apparent hyperproliferation of Tnf Δ ARE/ + splenocytes in the MLRs correlated with a stimulus-dependent twofold increase in the number of activated CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells (not depicted). Taken together, these data indicate that chronic overproduction of TNF in Tnf ΔARE mice results in the selective accumulation of activated/memory CD8+ T cell subsets. This accumulation correlates with an increased reactivity to allogeneic and syngeneic targets, and may therefore bear direct pathogenic significance in the development of IBD.

Figure 2.

CTL activity of Tnf Δ AREsplenocytes in response to syngeneic stimulation. CTL assay on the syngeneic epithelial cell line CMT-93. Mitomycin C–treated, 3[H]thymidine-pulsed CMT-93 target (T) cells were cocultured with increasing numbers of wild-type (left) and Tnf Δ ARE/ + effector (right) in the presence or absence of anti-CD3 (2C11) or anti-TNF antibody (TN3). 3[H] label loss indicates target cell lysis.

To validate the potential involvement of specific lymphocyte subsets in the pathogenesis of TNF-driven IBD, we generated Tnf ΔARE mice congenitally lacking CD4+ or CD8+ T cells by crossing into CD4 or β2-microglobulin–deficient backgrounds, respectively (22, 23). Interestingly, elimination of CD4+ T cells resulted in disease exacerbation associated with high incidences of mortality in Tnf ΔARE/+ CD4 −/− groups by the age of 2–3 mo (Table I and unpublished data). In striking contrast, elimination of MHC-I/CD8+ T cell responses in Tnf ΔARE/+ mice resulted in the delayed development and significant attenuation of IBD (Table I). Interestingly, Tnf ΔARE/+ μMT −/− and Tnf ΔARE/+ TcRδ−/− mice, which are devoid of B cells and γδTcR T cells, respectively (26, 27), developed IBD with similar severity to the control groups, indicating that these lymphocyte subsets are not actively involved in the development of the disease (Table I). Finally, the introduction of the Tnf Δ AREallele into IL-12 p40 (24) or IFNγ- (25) deficient backgrounds attenuated the development of intestinal inflammation, indicating the importance of Th-1–like cytokines in TNF-induced IBD. In contrast, disease induction and progression remained unaltered in Tnf ΔARE/+ IL-4 − / − mice (30 and unpublished data). Collectively, these data demonstrate that chronic TNF over-production in Tnf ΔARE mice promotes a pathogenic Th1-like cytokine response, which, together with non-γδTCR, CD8+ effector T cells play an essential role in the development of chronic progressive inflammatory pathology in the intestine.

Redundancy in the Cellular Sources of TNF-driving IBD: Myeloid Cells or T Lymphocytes Are Sufficient in Providing Pathogenic TNF Loads.

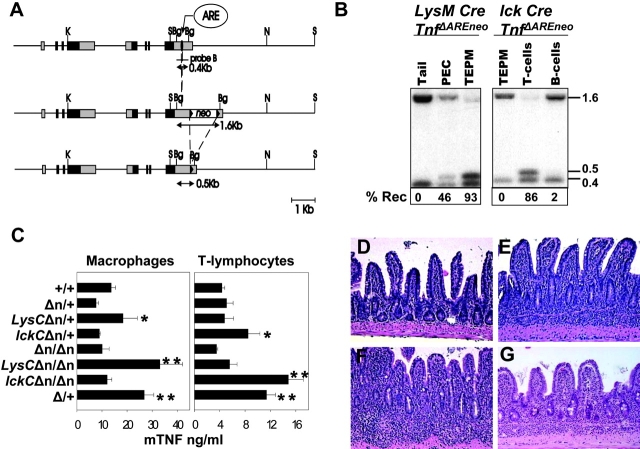

To identify the cellular source(s) of pathogenic TNF in our model, we set up a system of tissue-specific activation of the TnfΔAREallele. To this end, we used a targeted mutant mouse strain, which contains a “hypomorphic” TnfΔAREneoallele generated by the introduction of a neomycin acetyltransferase gene (neo r gene) flanked by loxP sequences next to the ΔARE mutation (Fig. 3 A; reference 5). Mice of the TnfΔAREneogenotype show a low to normal range of myeloid- and lymphoid-specific TNF production compared with Tnf +mice and do not develop any signs of intestinal pathology even at homozygosity (Fig. 3, C and D). After germ line or tissue-specific expression of Cre recombinase, the loxP sequences allow for the complete or tissue-specific removal of the “floxed” neorgene and the respective activation of the TnfΔAREallele (Fig. 3, A–C).

Figure 3.

Myeloid- and lymphoid-specific deregulation of TNF biosynthesis. (A) Structure of the TNF/LTα locus on mouse chromosome 17 and the strategy for the Cre-specific removal of floxed neo r allele. Filled boxes represent exons and gray shaded boxes represent untranslated regions. Filled arrowheads indicate the position of the loxP sequences. The positions of the TNF AU-rich element (ARE) and the floxed neo marker are indicated. The location of the 3′ 0.4-Kb BglII probe is also indicated. Restriction enzyme sites are Bg:BglII, K:KpnI, N:NotI, and S:SacI. (B) Southern blot analysis of BglII-digested DNA from tail, peritoneal cavity cells (PEC), total exudate peritoneal macrophages, and T and B lymphocytes from LysM-Cre or lck-Cre Tnf Δ AREneomice. Detected with the 3′ probe are the neo + (1.6 Kb), neo- (0.5 Kb), and wild-type (0.4 Kb) fragments. (C) TNF protein production as determined by ELISA in culture supernatants from peritoneal macrophages (left) or splenic T cells (right) isolated from individual LysM-Cre (LysC) or lck-Cre (lckC) Tnf Δ AREneo(Δn) mice and stimulated with LPS or anti-CD3, respectively. Data shown as mean ng/ml (± SD) per group. P < 0.02 relative to (*) Tnf Δ AREneo/ + or (*) Tnf Δ AREneo/ Δ AREneovalues with n = 3 mice/group. Histologic examination of ileal sections from 5-mo-old (D) Tnf Δ AREneo/ Δ AREneo, (E) LysM-Cre Tnf Δ AREneo/ +, (F) LysM-Cre Tnf Δ AREneo/ Δ AREneo, and 7-mo-old (G) lck-Cre Tnf Δ AREneo/ Δ AREneomutant mice. Paraffin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. ×100.

To restrict the production of TNF by the Tnf Δ AREallele in cells of the myeloid lineage, we crossed Tnf Δ AREneomice to mice expressing Cre under the control of the endogenous lysozyme M promoter (LysM-Cre mice; reference 20). Cre-specific recombination and TNF overproduction was confirmed to be restricted to the myeloid cell compartment. (Fig. 3, B and C). Both LysM-Cre/Tnf Δ AREneo/ + and LysM-Cre/Tnf Δ AREneo/ Δ AREneomice appeared grossly normal until the age of 4 mo. Past this age, both groups developed symptoms of weight loss, which were more severe in the LysM-Cre/Tnf ΔAREneo/ΔAREneo mice (unpublished data). Histological evaluation indicated the development of Crohn's-like IBD in both heterozygous and homozygous LysMCre/Tnf Δ AREneomice (Fig. 3, E and F).

To examine whether TNF hyperproduction by T lymphocytes suffices to elicit IBD we also generated Tnf Δ AREneomice carrying the Cre transgene under the control of the proximal lck promoter (29). In this case, Cre-specific recombination and TNF overproduction was found to be restricted to the lymphoid compartment. (Fig. 3, B and C). The lck-Cre/Tnf Δ AREneo/ + mice did not develop signs of intestinal pathology (not depicted). However, lck-Cre/Tnf Δ AREneo/ Δ AREneomice developed IBD past 5 mo of age, although with reduced severity relative to LysM-Cre/Tnf Δ AREneo/ Δ AREneoand Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice (Fig. 3 G). In contrast to myeloid and T cell compartments, TNF overproduction by the B cell lineage by means of Cre-mediated activation of the Tnf Δ AREneoallele in CD19+ B cells (31), did not result in the development of IBD even in CD19-Cre/Tnf Δ AREneo/ Δ AREneo mice past 15 mo old (unpublished data).

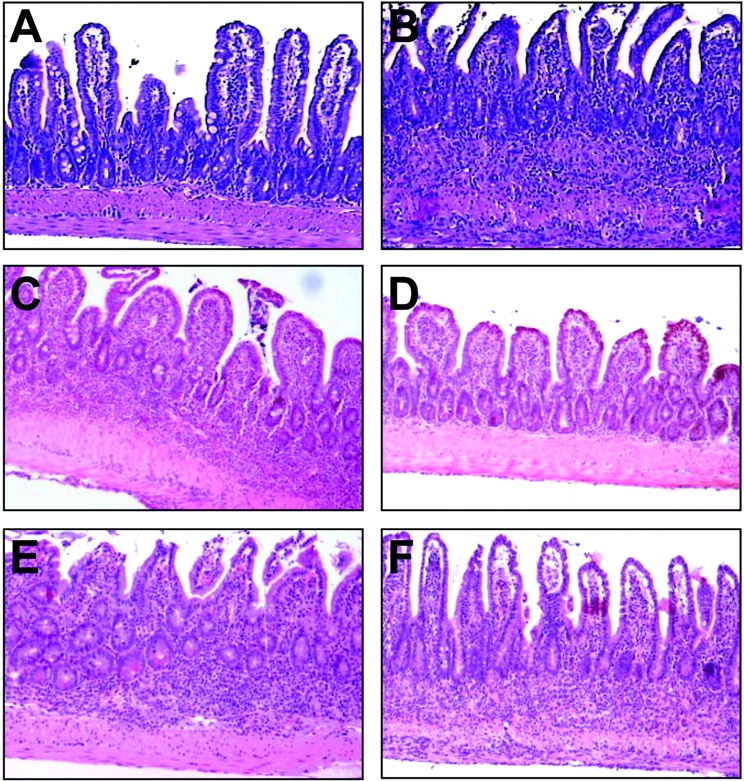

To confirm the tissue origin of TNF-producing cells that support the development of TNF-mediated IBD and to examine whether non-bone marrow–residing cells may also contribute pathogenic TNF loads, we performed a series of bone marrow engraftment experiments into lethally irradiated recipients. When bone marrow from Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice was transplanted into lethally irradiated (B6,129) Tnf + / + mice, the majority of the recipients exhibited weight loss 4–6 wk after transplantation (not depicted) and fully developed IBD 10–12 wk after transplantation. The disease borne all the pathological hallmarks of the donor's disease (Table II and Fig. 4 B), including the accumulation of activated CD8+ T cells (not depicted). In contrast, none of the Tnf + / + recipients of Tnf + / + bone marrow developed signs of intestinal pathology (Table II and Fig. 4 A). To examine whether radio-resistant Tnf Δ AREstromal cells suffice to induce IBD, we transplanted Tnf + / + bone marrow into irradiated Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice. In this case, and to prohibit the development of IBD in the host before transplantation, Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice were treated with anti-TNF antibody before irradiation and were kept without antibody administration after reconstitution (refer to Materials and Methods). Nonirradiated control groups treated with anti-TNF antibody until the age of reconstitution of the test groups developed full IBD 9 wk after the removal of the antibody (Fig. 4 C). In sharp contrast and at this same age, irradiated Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice reconstituted with Tnf + / + bone marrow showed mild signs of villus blunting but did not develop intestinal inflammation (Fig. 4 D). Taken together, these findings indicate that bone marrow–derived TNF producers such as myeloid cells and/or T lymphocytes, but not tissue stroma cells, constitute cellular sources of TNF with full independent capacity for inducing IBD.

Table II.

IBD Development after TnfΔARE Bone Marrow Reconstitution of Lethally Irradiated Recipientsc

| Donor genotypea | Recipientgenotypeb | IBDdevelopmentd |

|---|---|---|

| Tnf+/+ | Tnf+/+ | 0/10 |

| TnfΔARE/+ | Tnf+/+ | 9/11 |

| Tnf+/+ | TnfΔARE/+c | 0/5 |

| TnfΔARE/ΔARE TnfRI−/− | Tnf+/+ | 3/3 |

| TnfΔARE/ΔARE TnfRI/RII−/− | Tnf+/+ | 4/4 |

| TnfΔARE/+ | TnfRI−/− | 3/3 |

| TnfΔARE/+ | TnfR/,II−/− | 3/3 |

Bone marrow isolated from

2-mo-old female B6,129 mice was engrafted onto

6–8-wk-old syngeneic, lethally irradiated female mice.

Transfers onto TnfΔARE/+recipients were performed on anti-TNF–treated animals until the day of transfer to inhibit prior disease development.

Assessment based on histopathological evaluation of intestinal samples 12 wk after transfer.

Figure 4.

TNF individually targets hemopoietic and stromal components to induce IBD. Representative photomicrographs of ileal sections from bone marrow–reconstituted mice. (A) Tnf + / + bone marrow into Tnf + / + recipient, (B) Tnf Δ ARE/ + bone marrow into Tnf + / + recipient, (C) anti-TNF–treated control, (D) Tnf + / + bone marrow into Tnf Δ ARE/ + recipient (refer to Materials and Methods and text for details), (E) Tnf Δ / Δ TNFRI/II − / − bone marrow into Tnf + / + recipient, and (F) Tnf Δ ARE/ + bone marrow into TNFRI/II − / − recipient. Paraffin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. ×100.

Redundancy in the Cellular Targets of TNF Function in IBD: Bone Marrow– or Tissue Stroma–residing Cell Targets Are Equally Responsive to the Pathogenic Effects of TNF.

To gain insight on specific cellular targets of TNF function in the TnfΔAREmodel, we performed a series of additional reciprocal bone marrow transplantation experiments between wild-type, TnfΔARE, and TNF receptor–deficient mice. Transfer of TnfΔARE/+ TnfRI−/−or TnfΔARE /+ TnfRI,II − / − bone marrow into wild-type irradiated recipients readily resulted in an IBD phenotype similar to the TnfΔAREreconstituted mice, as indicated by the histopathological findings 12 wk after transfer (Table II and Fig. 4 E), suggesting that radiation-resistant, tissue stroma–residing cells are sufficient TNF targets for the induction of IBD. Remarkably, a similar disease profile 12 wk after engraftment was obtained in the reciprocal experiment, i.e., the transfer of TnfΔARE/ 1 bone marrow into TnfRI,II − / −or TnfRI − / −recipients (Table II and Fig. 4 F), indicating that radiation-sensitive, bone marrow–derived cells are equally important and sufficient targets for pathogenic TNF.

These findings clearly indicate the existence of independent, yet redundant, cellular pathways operating downstream of TNF in the pathogenesis of IBD.

Disease-promoting Signals via the tpl2 and JNK-2 Kinases and Opposing Signals by MK2 in IBD.

The redundancy of cellular interactions promoted by TNF in modeled IBD indicated the difficulty in targeting such mechanisms to inhibit the disease. Therefore, we aimed to genetically identify intracellular signaling pathways that could affect a pleiotropy of cellular responses to provide a therapeutic outcome. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase MAPK/SAPK-mediated intracellular signals have been numerously associated with immune pathologies (32). However, in most cases, blockade of these pathways lead to the biosynthetic blockade of several proinflammatory mediators including TNF, masking the role of these molecules in complex downstream cellular responses. We have previously shown that the SAPKs p38 and JNK, and the MKKK Cot/Tpl2 kinase, target the 3′ ARE sequences of TNF mRNA to modulate the biosynthesis of TNF (5, 7, 19, 33). Consequently, TNF production by the mutated Tnf Δ AREgene in the mouse should not be affected by the presence or absence of these specific kinases. This finding suggested that ablation of these kinases in Tnf ΔARE mice may provide clues on their role in the effector functions of TNF independent of their effects on TNF biosynthesis. Based on these considerations, we generated Tnf ΔARE mice deficient in the p38-activated MK2 (17, 33), the JNK2 kinase (18, 34), or the Tpl2 kinase (19). The absence of MK2, Tpl2, and JNK2 kinases did not reduce the production of TNF by LPS-stimulated Tnf ΔARE macrophages. In addition, the production of two other proinflammatory mediators, IL-6 and NO, by TNF and LPS-stimulated Tnf ΔARE macrophages was not compromised by the absence of MK2, JNK2, or Tpl2, whereas in contrast, in the latter two groups it was significantly higher (not depicted). This data indicates that the proinflammatory impetus can be maintained in Tnf Δ AREmice in the absence of these kinase signals.

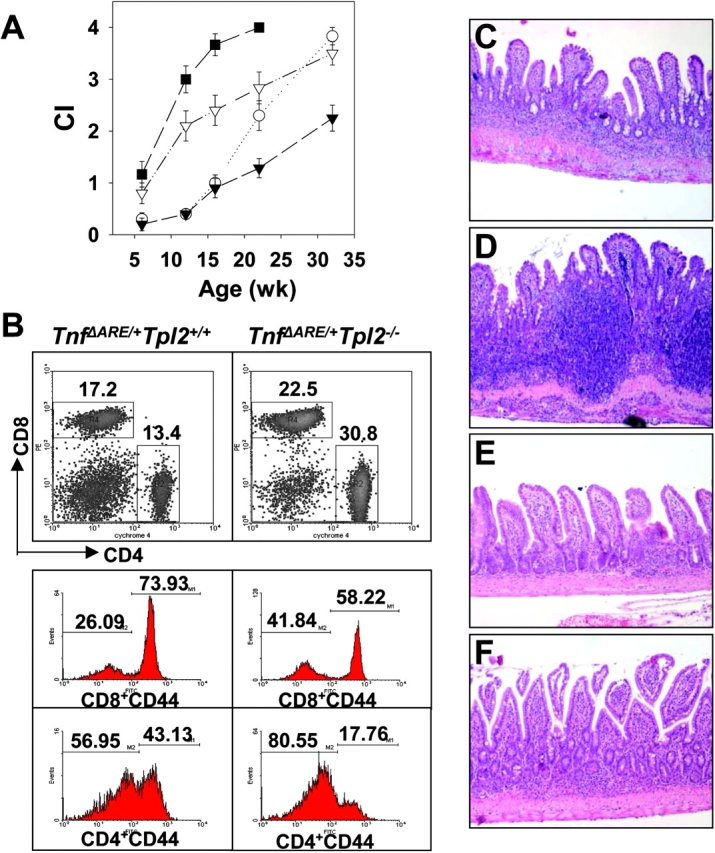

Contrary to its presumed requirement for the activation of proinflammatory programs, the absence of the MK2 signaling pathway resulted in the profound exacerbation of the Tnf Δ AREphenotype and was associated with high incidences of mortality from the age of 8 wk onwards (Fig. 5 A and unpublished data). IBD development in Tnf Δ ARE/ + mk2 −/− mice was associated with the early formation of multiple granulomas and extensive lymphocytic aggregates in the lamina propria (Fig. 5 D). In striking contrast, the absence of the JNK2 or the Tpl2 kinases resulted in a delayed onset and a significant attenuation in the development of IBD (Fig. 5, A, E, and F). In both cases, chronic intestinal inflammation (i.e., macrophage and lymphocytic exudates) was significantly reduced (Fig. 5 A). Flow immunocytometric analysis of splenocyte populations from the kinase-deficient animals at the age of 4 mo indicated that relative to control Tnf Δ AREpopulations, CD4+ to CD8+ lymphocyte ratios remained unaltered in MK2- and JNK2-deficient animals (not depicted) but not in Tpl2-deficient animals (Fig. 5 B). Despite the increased presence of CD11b+ and Gr1+ myeloid cells, indicating a persistent innate immune activation (not depicted), Tnf Δ ARE/ + tpl2 −/−–deficient splenocytes contained a higher content of T lymphocytes than Tnf Δ ARE/ + controls (not depicted), but a correct CD8/CD4 ratio (Fig. 5 B). Interestingly, this difference was attributed to a significant increase in total CD4+ counts, which primarily possessed a CD44lo phenotype indicating that they are mostly accumulating in a naive state (Fig. 5 B). Most importantly, the number of CD8+ CD44hi T cells was found to be significantly reduced in Tnf Δ ARE/ + tpl2 −/− splenocytes relative to Tnf Δ ARE/ + controls (Fig. 5 B), suggesting that the absence of Tpl2 affects the pathogenic lymphocytic responses.

Figure 5.

MK2, JNK2, and Tpl2 kinase–mediated signals in the development of TNF-mediated IBD. (A) Chronic inflammatory indices (CI) indicating the development of intestinal inflammation based on the histopathological assessment of Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice (▿) in MK2- (▪), Jnk2- (▾), and Tpl2- (○) deficient backgrounds. (B) Representative density and histogram plots indicating the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as their percentages of CD44+ marker in Tnf Δ ARE/ + and Tnf Δ ARE/ + Tpl2 − / − splenocytes after flow immunocytometric analysis. (C–F) Representative histology of 3-mo-old (C) Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice bred into (D) MK2-, (E) Jnk2-, or (F) Tpl2-deficient backgrounds. All paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. ×100.

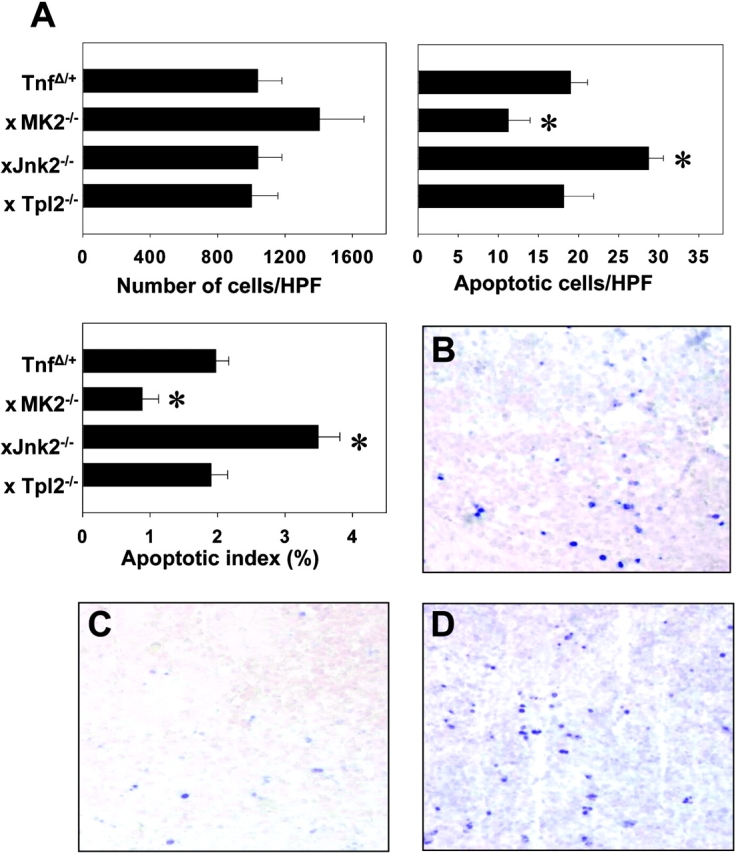

The absence of any significant alterations amongst the Tnf Δ ARE/ + peripheral lymphocytes in the presence or absence of MK2 and JNK2 kinases suggested that these signals may affect events in the locality of the intestine. Recent evidence indicated a strong correlation between the death of lymphocytic (or other) infiltrates in the intestine and the modulation of intestinal inflammation (14). Thus, we counted the number of apoptotic cells in inflamed ileal sections from Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice in the absence of MK2 and Jnk2, using a TUNEL Assay. To circumvent the problem of the difference in inflammation between these groups we selected ileal samples with similar inflammatory indices. More specifically, we compared the number of apoptotic cells in inflamed ilea from 3-mo-old Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice, 2-mo-old Tnf Δ ARE/ + mk2 − / − mice, and 7-mo-old Tnf Δ ARE/ + JNK2 −/− mice bearing comparable numbers of LPMCs (Fig. 6 A). A high incidence of apoptotic cells was observed in the compartment of the LPMCs in Tnf Δ ARE/ + ilea at the age of 3 mo. (Fig. 6, A and B). Strikingly, the number of positive apoptotic cells was significantly lower in Tnf Δ ARE/ + mk2 − / −–deficient ilea suggesting a significant inhibition of cell death in the absence of MK2 (Fig.6, A and C). In contrast, the number of apoptotic cells in Tnf Δ ARE/ + JNK2 −/− ilea was dramatically increased relative to the lower cell numbers in the infiltrate indicating an increased rate of apoptosis (Fig. 6, A and D). Comparison of the apoptotic indices between 3-mo-old Tnf Δ ARE/ + ilea and 6-mo-old Tnf Δ ARE/ + Tpl2 − / − did not reveal any significant differences (not depicted). Overall, our data suggest that Tpl2 and JNK2 kinases favor, whereas the MK2 kinase opposes, the development of IBD.

Figure 6.

MK2 and JNK2 kinase signals associate with the modulation of intestinal mononuclear apoptosis in the context of TNF-mediated IBD. (A) Quantitation of the infiltrating and apoptotic cells and the percentage of apoptotic cells in the infiltrate (apoptotic index) in the lamina propria of signaling-deficient Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice. *, values of statistical significance relative to the Tnf Δ ARE/ + group. Representative photomicrographs of paraffin-embedded ileal sections from (B) Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice bred into (C) MK2- or (D) Jnk2-deficient backgrounds followed by the in situ detection of apoptotic cells. Alkaline phosphatase–labeled apoptotic cells were visualized using Fast Blue substrate and counterstaining with Nuclear Fast Red. B–D, ×300.

Discussion

Regardless of the aetiopathogenic event(s) that initiate IBD, aberrant TNF production and function appear to be centrally involved in the pathogenesis of both the human disease and its animal models. TNF hyperproduction in the Tnf Δ AREmodel results from the loss of translational and stability controls on the TNF mRNA and the lack of antiinflammatory regulation of TNF production (5, 7, 19). From the data presented here, it is clear that the inflammatory impetus provided by this permutation impels multiple and overlapping cellular cascades that can be modulated by distinct intracellular signals.

The Cellular Interactions Governing TNF-mediated IBD.

The data presented here extend earlier observations suggesting a pathogenic role for TNF derived from innate effectors in supporting intestinal inflammation (35, 36). It seems that the intrinsic capacity of myelomonocytic cells to hyperproduce TNF due to the ARE defect coupled to their extensive presence in the anatomical site of the intestine, which is rich in lumenal bacterial products, can lead to the unrestricted presence of numerous proinflammatory mediators that besides TNF may include IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12. This pathogenic milieu can cause tissue damage, recruit inflammatory exudates from the periphery supporting chronic intestinal inflammation, and most importantly, increase antigen-presenting molecules on the surfaces of hemopoietic and stromal cells thus increasing their ability to present lumenal antigens and bacterial products (12). From our data it is clear that T lymphocyte–derived TNF is also sufficient, albeit less efficacious, to drive the pathogenic events leading to IBD. Although currently unclear, the pathogenic difference between myeloid and T cell–derived TNF may lie on differences in the tissue distribution of these cells, the mode of their activation by different stimuli, the amount of TNF they produce after stimulation, and the type of pathogenic cascades that they are capable of inducing on target cells. The action of TNF in IBD, as exemplified by our studies, does not seem to be solely of an innate proinflammatory character but may extend in the modulation of a specific lymphocytic response. Most animal models representing a Th1-driven mucosal inflammation seem to depend on aberrations either on the effector functions of CD4+ T cell subsets or defects in a CD4+-mediated counter response (1). In contrast, the aberrant TNF load in our model shapes up a hyperactive CD8+ lymphocytic response, which is detectable in the periphery of Tnf Δ AREmice even before the onset of IBD as suggested by our MLR assays. Most importantly, our data demonstrate a dominant role for Th1-driven CD8+ T cells as IBD effectors in Tnf ΔARE mice. Intriguingly, this unique property of the Tnf Δ AREmodel appears in line with its Crohn's-like ileal localization of mucosal inflammation, a characteristic that is different to the colonic localization of the mucosal lesions in the CD4+ T cell–dependent models (1). Interestingly, enhanced peripheral blood T cell cytotoxicity attributed to CD8+ lymphocytes has been detected in patients with Crohn's disease (37, 38). More recently, transgenic overexpression of IL-15 in the murine small intestine led to the local activation of TNF/IFNγ-producing CD8+ αβ T cells that supported the development of small intestinal inflammation (39). CD8+ T cells are numerously represented in the intestinal mucosal, intraepithelial and lamina propria, lymphocyte fractions and their cytotoxic T cell function supports a possible pathogenic role. There are many plausible scenarios by which TNF may interfere with CD8+ T cell responses (refer to Introduction). The effects of TNF on CD8+ T cells might be direct (e.g., via modulation of the thresholds of T cell activation or their rate of apoptosis) although evidence for such a mechanism is currently lacking. Alternatively, TNF may affect the nature of the innate signals that influence the character of the CD8+ response (40). The observation that effector TNF signaling on bone marrow–derived cells is fully sufficient to drive the development of pathology supports the hemopoietic origin of TNF targets in IBD. An additional interesting observation in this study is that deficiency in the CD4+ T cell compartment exacerbates IBD in Tnf ΔARE mice, suggesting that CD4+ T cells may regulate pathogenic CD8+ T cell responses in this model. Recently, it was demonstrated that CD4+ CD25+ were capable of suppressing CD8+ activation in vitro (41). Therefore, it is possible that such a form of modulation also exists in the Tnf ΔARE mice, although the efficiency and specificity of this interaction remain to be determined.

Our evidence indicates that TNF-dependent mechanisms driving the aberrant and pathogenic CD8+ T cell responses may not only be initiated by TNF targeting directly bone marrow–derived cell targets, but that also tissue stromal cells may constitute independent direct TNF targets with equal pathogenic capacity. TNF can induce a multiplicity of responses in stromal cells. For example, intestinal epithelial cells readily apoptose after the administration of TNF in vivo (13). In addition, TNF can increase the ability of epithelial and endothelial cells to secrete potent chemotactic cytokines, such as IL-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, which serve to increase the movement of macrophages and granulocytes from the circulation into the inflamed mucosa (42), supporting chronic intestinal inflammation. Finally, TNF can increase the presence of MHC class II antigen-presenting molecules on the surfaces of epithelial cells and endothelial cells thus increasing their ability to present lumenal antigens and bacterial products (43). This could result in the loss of mucosal tolerance to innocuous antigens or autoantigens (44) or even in the assault of the mucosal barrier and its attack by an activated lymphocytic response (45).

Signaling Requirements in TNF-driven IBD.

The absence of the ARE from the Tnf gene in the Tnf Δ AREmice provided us with the opportunity to examine the involvement of specific effector signals delivered by TNF in IBD in the absence of a parallel impact of such signals on TNF biosynthesis itself. We have previously shown that production of TNF from a Tnf Δ AREallele cannot be modulated by SAP kinase blockade (5, 7), nor by the genetic ablation of the Tpl2 kinase (19). In this study, analysis of the impact of genetic ablation of MK2, JNK2, or Tpl2 kinases in the IBD pathology developing in the Tnf Δ AREmice led to differential results on the development of intestinal inflammation.

In the absence of p38/MK2 signaling, TNF-dependent IBD is exacerbated. In general, the p38/MK2 signaling pathway is considered to be proinflammatory due to its potentiating effects on proinflammatory cytokine biosynthesis (17). Surprisingly, therefore, the effector role of this kinase in IBD is shown here to be antiinflammatory. The following evidence are in support of an effect of the p38 pathway on lymphocyte modulation and thus to the cellular cascades supporting IBD in Tnf Δ AREmice: (a) continuous MKK6/p38 signaling in lymphocytes has been shown to result in the selective killing of CD8+ peripheral lymphocytes (46), (b) genetic deficiency in the p38 activating kinases MKK3 or MKK6 blocks peripheral or thymic T lymphocyte apoptosis, respectively (47), and (c) inactivation of p38 by sodium salicylate blocks the antiapoptotic transcription factor, nuclear factor (NF)κB (48). In this study, disease exacerbation in the absence of MK2 correlated with decreased apoptosis in the LPMC fraction of the mucosa, indicating that regulation of LPMC survival might be an important mechanism of MK2 function in disease.

Development of IBD in the absence of JNK2 was significantly attenuated. In JNK2-deficient mice, stimulated lymphocytes hypoproliferate, produce less IL-2 and IFNγ, and are unable to establish a Th-1 response (18, 34). In addition, they are unable to mount correct innate responses to viral infections (49). Although not directly assessed in our system, it is plausible that incorrect innate activation and lack of a Th-1 response suppresses TNF-induced intestinal inflammation. Previous reports have failed to assign a role for this kinase in the modulation of peripheral T cell apoptosis (18, 34). We observed that in the absence of JNK2, the rate of LPMC apoptosis is increased, indicating that in the context of TNF-induced inflammation this kinase may promote antiapoptotic signals in the periphery.

Despite the wealth of information on the potential roles of MAPK/SAPK signaling in inflammation, the immune effector functions of the Tpl2 kinase have not been previously addressed. In terms of the adaptive immune response, Tpl2 may directly modulate the pathogenic lymphocytic response because its absence from Tnf Δ ARE/ + mice correlates with a reduction of activated/memory CD4+ and CD8+ peripheral T cells (Fig. 5). The activation of Tpl2 has been associated with the proliferative control of lymphocytes (50). In addition, peripheral T lymphocytes from Tpl2-deficient animals undergo rapid apoptosis in the presence of antigenic stimulation and IL-2 (unpublished data). On the other hand, Tpl2 can modulate the production of key innate effectors like COX-2 (51). Tpl2 has been demonstrated to activate a pleiotropy of downstream signals in vitro including MAPKs/SAPKs, NFκB, and caspase-mediated signals (52–54), although in vivo evidence for these responses is currently lacking. Recently, Tpl2 has been detected to interact with TNF receptor–associated factor 2 to promote the activation of NFκB (55), indicating that Tpl2 might be directly implicated into the diverse array of responses instigated by the TNF receptor superfamily. It is conceivable, therefore, that Tpl2 may affect both innate and adaptive immune responses to support the development of intestinal inflammation.

Concluding Remarks.

The data presented in this report suggest that, in cellular terms, a critical element in TNF-induced Crohn's-like IBD is the activation of a Th1-driven pathogenic CD8+ T cell response. This sensitizing effect of TNF on the adaptive immune response appears to be transduced by multiple and redundant signals that target bone marrow–derived and/or tissue stroma cells to finally converge in the critical production of IL-12 and IFN-γ and in the activation of the deleterious CD8+ T cell response. In molecular terms, genetic inactivation experiments revealed that at least two kinases, Tpl2 and JNK2, promote, whereas a third one, MK2, opposes the induction of IBD, indicating that regardless of pleiotropy of cellular processes that these signals modulate, they are likely candidates for pharmaceutical targeting. Although these kinases may directly transduce TNF receptor–instigated signals, the specific cell type(s) and the critical pathway(s) with which they interfere to modulate development of IBD remains to be elucidated. Our data provide new mechanistic insights into the pathophysiology of IBD and identify Tpl2 and JNK2 kinases as potential targets for therapy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Wim Buurman for the TNF-specific ELISAs and Mr. Spiros Lalos for technical assistance in histopathology. We are grateful to Michael Papamichael and Kostas Baxevanis (Ag. Savas Hospital) for allowing access to their γ irradiator.

This work was supported in part by European Commission grants QLG1-CT1999-00202, QLK6-1999-02203, QLRT-CT-2001-01407, and QLRT-2001-00422 to G. Kollias, United States Public Health Service grant CA38047 to P. Tsichlis, and the National Institutes of Health grant DK42191.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: ARE, AU-rich element; hpf, high power fields; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; LPMC, lamina propria mononuclear cell; MK2, MAPKAP kinase 2; ML, mononuclear leukocytes; NF, nuclear factor; NO, nitric oxide; PMN, polymorphonuclear; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated, dUTP nick end labeling.

References

- 1.Strober, W., I.J. Fuss, and R.S. Blumberg. 2002. The immunology of mucosal models of inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:495–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powrie, F., M.W. Leach, S. Mauze, S. Menon, L.B. Caddle, and R.L. Coffman. 1994. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1:553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neurath, M.F., I. Fuss, M. Pasparakis, L. Alexopoulou, S. Haralambous, K.H. Meyer zum Buschenfelde, W. Strober, and G. Kollias. 1997. Predominant pathogenic role of tumor necrosis factor in experimental colitis in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:1743–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kojouharoff, G., W. Hans, F. Obermeier, D.N. Mannel, T. Andus, J. Scholmerich, V. Gross, and W. Falk. 1997. Neutralization of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) but not of IL-1 reduces inflammation in chronic dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 107:353–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kontoyiannis, D., M. Pasparakis, T.T. Pizarro, F. Cominelli, and G. Kollias. 1999. Impaired on/off regulation of TNF biosynthesis in mice lacking TNF AU-rich elements: implications for joint and gut-associated immunopathologies. Immunity. 10:387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosiewicz, M.M., C.C. Nast, A. Krishnan, J. Rivera-Nieves, C.A. Moskaluk, S. Matsumoto, K. Kozaiwa, and F. Cominelli. 2001. Th1-type responses mediate spontaneous ileitis in a novel murine model of Crohn's disease. J. Clin. Invest. 107:695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kontoyiannis, D., A. Kotlyarov, E. Carballo, L. Alexopoulou, P.J. Blackshear, M. Gaestel, R. Davis, R. Flavell, and G. Kollias. 2001. Interleukin-10 targets p38 MAPK to modulate ARE-dependent TNF mRNA translation and limit intestinal pathology. EMBO J. 20:3760–3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papadakis, K.A., and S.R. Targan. 2000. Tumor necrosis factor: biology and therapeutic inhibitors. Gastroenterology. 119:1148–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Locksley, R.M., N. Killeen, and M.J. Lenardo. 2001. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 104:487–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Podolsky, D.K. 1991. Inflammatory bowel disease (1). N. Engl. J. Med. 325:928–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Deventer, S.J. 1997. Tumour necrosis factor and Crohn's disease. Gut. 40:443–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papadakis, K.A., and S.R. Targan. 2000. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 51:289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piguet, P.F., C. Vesin, J. Guo, Y. Donati, and C. Barazzone. 1998. TNF-induced enterocyte apoptosis in mice is mediated by the TNF receptor 1 and does not require p53. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:3499–3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neurath, M.F., S. Finotto, I. Fuss, M. Boirivant, P.R. Galle, and W. Strober. 2001. Regulation of T-cell apoptosis in inflammatory bowel disease: to die or not to die, that is the mucosal question. Trends. Immunol. 22:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kollias, G., E. Douni, G. Kassiotis, and D. Kontoyiannis. 1999. On the role of tumor necrosis factor and receptors in models of multiorgan failure, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol. Rev. 169:175–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kollias, G., and D. Kontoyiannis. 2002. Role of TNF/TNFR in autoimmunity: specific TNF receptor blockade may be advantageous to anti-TNF treatments. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 222:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotlyarov, A., A. Neininger, C. Schubert, R. Eckert, C. Birchmeier, H.D. Volk, and M. Gaestel. 1999. MAPKAP kinase 2 is essential for LPS-induced TNF-alpha biosynthesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:94–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang, D.D., D. Conze, A.J. Whitmarsh, T. Barrett, R.J. Davis, M. Rincon, and R.A. Flavell. 1998. Differentiation of CD4+ T cells to Th1 cells requires MAP kinase JNK2. Immunity. 9:575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dumitru, C.D., J.D. Ceci, C. Tsatsanis, D. Kontoyiannis, K. Stamatakis, J.H. Lin, C. Patriotis, N.A. Jenkins, N.G. Copeland, G. Kollias, et al. 2000. TNF-alpha induction by LPS is regulated posttranscriptionally via a Tpl2/ERK-dependent pathway. Cell. 103:1071–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clausen, B.E., C. Burkhardt, W. Reith, R. Renkawitz, and I. Forster. 1999. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res. 8:265–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothe, J., W. Lesslauer, H. Lotscher, Y. Lang, P. Koebel, F. Kontgen, A. Althage, R. Zinkernagel, M. Steinmetz, and H. Bluethmann. 1993. Mice lacking the tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 are resistant to TNF-mediated toxicity but highly susceptible to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Nature. 364:798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahemtulla, A., W.P. Fung-Leung, M.W. Schilham, T.M. Kundig, S.R. Sambhara, A. Narendran, A. Arabian, A. Wakeham, C.J. Paige, and R.M. Zinkernagel. 1991. Normal development and function of CD8+ cells but markedly decreased helper cell activity in mice lacking CD4. Nature. 353:180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zijlstra, M., E. Li, F. Sajjadi, S. Subramani, and R. Jaenisch. 1989. Germ-line transmission of a disrupted beta 2-microglobulin gene produced by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Nature. 342:435–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magram, J., S.E. Connaughton, R.R. Warrier, D.M. Carvajal, C.Y. Wu, J. Ferrante, C. Stewart, U. Sarmiento, D.A. Faherty, and M.K. Gately. 1996. IL-12-deficient mice are defective in IFN gamma production and type 1 cytokine responses. Immunity. 4:471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalton, D.K., S. Pitts-Meek, S. Keshav, I.S. Figari, A. Bradley, and T.A. Stewart. 1993. Multiple defects of immune cell function in mice with disrupted interferon-gamma genes. Science. 259:1739–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitamura, D., J. Roes, R. Kuhn, and K. Rajewsky. 1991. A B cell-deficient mouse by targeted disruption of the membrane exon of the immunoglobulin mu chain gene. Nature. 350:423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itohara, S., P. Mombaerts, J. Lafaille, J. Iacomini, A. Nelson, A.R. Clarke, M.L. Hooper, A. Farr, and S. Tonegawa. 1993. T cell receptor delta gene mutant mice: independent generation of alpha beta T cells and programmed rearrangements of gamma delta TCR genes. Cell. 72:337–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erickson, S.L., F.J. de Sauvage, K. Kikly, K. Carver-Moore, S. Pitts-Meek, N. Gillett, K.C. Sheehan, R.D. Schreiber, D.V. Goeddel, and M.W. Moore. 1994. Decreased sensitivity to tumour-necrosis factor but normal T-cell development in TNF receptor-2-deficient mice. Nature. 372:560–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orban, P.C., D. Chui, and J.D. Marth. 1992. Tissue- and site-specific DNA recombination in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:6861–6865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhn, R., K. Rajewsky, and W. Muller. 1991. Generation and analysis of interleukin-4 deficient mice. Science. 254:707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rickert, R.C., J. Roes, and K. Rajewsky. 1997. B lymphocyte-specific, Cre-mediated mutagenesis in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:1317–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong, C., R.J. Davis, and R.A. Flavell. 2002. MAP kinases in the immune response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:55–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neininger, A., D. Kontoyiannis, A. Kotlyarov, R. Winzen, R. Eckert, H.D. Volk, H. Holtmann, G. Kollias, and M. Gaestel. 2001. MK2 targets AU-rich elements and regulates biosynthesis of TNF and IL-6 independently at different post transcriptional levels. J. Biol. Chem. 277:3065–3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong, C., D.D. Yang, C. Tournier, A.J. Whitmarsh, J. Xu, R.J. Davis, and R.A. Flavell. 2000. JNK is required for effector T-cell function but not for T-cell activation. Nature. 405:91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corazza, N., S. Eichenberger, H.P. Eugster, and C. Mueller. 1999. Nonlymphocyte-derived tumor necrosis factor is required for induction of colitis in recombination activating gene (RAG)2−/− mice upon transfer of CD4+ CD45RBhi T cells. J. Exp. Med. 10:1479–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanahan, F., B. Leman, R. Deem, A. Niederlehner, M. Brogan, and S. Targan. 1989. Enhanced peripheral blood T-cell cytotoxicity in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Immunol. 9:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeda, K., B.E. Clausen, T. Kaisho, T. Tsujimura, N. Terada, I. Forster, and S. Akira. 1999. Enhanced Th1 activity and development of chronic enterocolitis in mice devoid of Stat3 in macrophages and neutrophils. Immunity. 10:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okazaki, K., Y. Yokoyama, Y. Yamamoto, M. Kobayashi, K. Araki, and T. Ogata. 1994. T cell cytotoxicity of autologous and allogeneic lymphocytes in a patient with Crohn's disease. J. Gastroenterol. 29:415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohta, N., T. Hiroi, M.N. Kweon, N. Kinoshita, M.H. Jang, T. Mashimo, J. Miyazaki, and H. Kiyono. 2002. IL-15-dependent activation-induced cell death-resistant Th1 type CD8alphabeta(+) NK1.1(+) T cells for the development of small intestinal inflammation. J. Immunol. 169:460–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green, E.A., F.S. Wong, K. Eshima, C. Mora, and R.A. Flavell. 2000. Neonatal tumor necrosis factor alpha promotes diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice by CD154-independent antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 191:225–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piccirillo, C.A., and E.M. Shevach. 2001. Cutting edge: control of CD8+ T cell activation by CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory cells. J. Immunol. 167:1137–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Deventer, S.J. 1997. Tumor necrosis factor and Crohn's disease. Gut. 40:443–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perdue, M.H. 1999. Mucosal immunity and inflammation. III. The mucosal antigen barrier: cross talk with mucosal cytokines. Am. J. Physiol. 277:G1–G5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinhoff, U., V. Brinkmann, U. Klemm, P. Aichele, P. Seiler, U. Brandt, P.W. Bland, I. Prinz, U. Zugel, and S.H. Kaufmann. 1999. Autoimmune intestinal pathology induced by hsp60-specific CD8 T cells. Immunity. 11:349–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vezys, V., S. Olson, and L. Lefrancois. 2000. Expression of intestine-specific antigen reveals novel pathways of CD8 T cell tolerance induction. Immunity. 12:505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merritt, C., H. Enslen, N. Diehl, D. Conze, R.J. Davis, and M. Rincon. 2000. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in vivo selectively induces apoptosis of CD8(+) but not CD4(+) T cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:936–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka, N., M. Kamanaka, H. Enslen, C. Dong, M. Wysk, R.J. Davis, and R.A. Flavell. 2002. Differential involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases MKK3 and MKK6 in T-cell apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 3:785–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwenger, P., D. Alpert, E.Y. Skolnik, and J. Vilcek. 1998. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase by sodium salicylate leads to inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-induced IkappaB alpha phosphorylation and degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chu, W.M., D. Ostertag, Z.W. Li, L. Chang, Y. Chen, Y. Hu, B. Williams, J. Perrault, and M. Karin. 1999. JNK2 and IKKbeta are required for activating the innate response to viral infection. Immunity. 11:721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salmeron, A., T.B. Ahmad, G.W. Carlile, D. Pappin, R.P. Narsimhan, and S.C. Ley. 1996. Activation of MEK-1 and SEK-1 by Tpl-2 proto-oncoprotein, a novel MAP kinase kinase kinase. EMBO J. 15:817–826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eliopoulos, A.G., C.D. Dumitru, C.C. Wang, J. Cho, and P.N. Tsichlis. 2002. Induction of COX-2 by LPS in macrophages is regulated by Tpl2-dependent CREB activation signals. EMBO J. 21:4831–4840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patriotis, C., M.G. Russeva, J.H. Lin, S.M. Srinivasula, D.Z. Markova, C. Tsatsanis, A. Makris, E.S. Alnemri, and P.N. Tsichlis. 2001. Tpl-2 induces apoptosis by promoting the assembly of protein complexes that contain caspase-9, the adapter protein Tvl-1, and procaspase-3. J. Cell. Physiol. 187:176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belich, M.P., A. Salmeron, L.H. Johnston, and S.C. Ley. 1999. TPL-2 kinase regulates the proteolysis of the NF-kappaB-inhibitory protein NF-kappaB1 p105. Nature. 397:363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsatsanis, C., C. Patriotis, S.E. Bear, and P.N. Tsichlis. 1998. The Tpl-2 protooncoprotein activates the nuclear factor of activated T cells and induces interleukin 2 expression in T cell lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:3827–3832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eliopoulos, A.G., C. Davies, S.S. Blake, P. Murray, S. Najafipour, P.N. Tsichlis, and L.S. Young. 2002. The oncogenic protein kinase Tpl-2/Cot contributes to Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent infection membrane protein 1-induced NF-kappaB signaling downstream of TRAF2. J. Virol. 76:4567–4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]