Abstract

The binding of immunoglobulin E (IgE) to high affinity IgE receptors (FcεRI) expressed on the surface of mast cells primes these cells to secrete, upon subsequent exposure to specific antigen, a panel of proinflammatory mediators, which includes cytokines that can also have immunoregulatory activities. This IgE- and antigen-specific mast cell activation and mediator production is thought to be critical to the pathogenesis of allergic disorders, such as anaphylaxis and asthma, and also contributes to host defense against parasites. We now report that exposure to IgE results in a striking (up to 32-fold) upregulation of surface expression of FcεRI on mouse mast cells in vitro or in vivo. Moreover, baseline levels of FcεRI expression on peritoneal mast cells from genetically IgE-deficient (IgE −/−) mice are dramatically reduced (by ∼83%) compared with those on cells from the corresponding normal mice. In vitro studies indicate that the IgE-dependent upregulation of mouse mast cell FcεRI expression has two components: an early cycloheximide-insensitive phase, followed by a later and more sustained component that is highly sensitive to inhibition by cycloheximide. In turn, IgE-dependent upregulation of FcεRI expression significantly enhances the ability of mouse mast cells to release serotonin, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-4 in response to challenge with IgE and specific antigen. The demonstration that IgE-dependent enhancement of mast cell FcεRI expression permits mast cells to respond to antigen challenge with increased production of proinflammatory and immunoregulatory mediators provides new insights into both the pathogenesis of allergic diseases and the regulation of protective host responses to parasites.

Mast cells are widely distributed in vascularized tissues and serosal cavities, where they can function as effector cells in IgE-dependent immune responses (1–8). Indeed, IgE- and antigen-dependent activation of mast cell mediator secretion is thought to contribute significantly to both the pathogenesis of allergic diseases (1, 4–8) and the expression of acquired immunity to infection with certain parasites (1, 3).

Several lines of evidence, including the phenotype of mice genetically engineered to lack expression of either the FcεRI α chain (9) or the FcR γ chain (10), indicate that mast cells (and basophils, circulating granulocytes that can produce many of the same mediators as mast cells; references 1–8) must display high affinity IgE receptors (FcεRI) on their surface in order to express significant IgE- and antigen-specific effector function. Yet the factors that regulate the expression of FcεRI on the surface of these effector cells are incompletely understood (5, 6). Two groups independently demonstrated that the level of FcεRI expression on circulating human basophils can exhibit a positive correlation with the serum concentration of IgE (11–13). However, the basis for this association was not determined. Malveaux et al. (13) proposed two possible explanations for their findings, i.e., a genetic association between serum IgE and the number of basophil IgE receptors or, more likely, in their view, the modulation of basophil receptor number by the serum IgE concentration. Another possibility is that some common factor (or factors), such as immunoregulatory cytokines, can influence both IgE levels and basophil FcεRI expression.

There have been no reports that circulating levels of IgE can influence the expression of FcεRI on mast cells. However, two studies demonstrated that short-term incubation of the rat basophilic leukemia cell line (RBL-2H3) with IgE in vitro can result roughly in a doubling of the cells' surface expression of FcεRI (14, 15). Based on an analysis of several of its phenotypic characteristics, the RBL-2H3 cell line probably should be regarded as of mast cell, rather than basophil, origin (16). The findings of Furuichi et al. (14) and Quarto et al. (15) thus indicate that exposure to monomeric IgE in vitro can result in a modest increase in FcεRI expression in a long-term malignant mast cell line. These studies also showed that this effect, which was insensitive to inhibition by cycloheximide (14), probably largely reflected IgE-dependent suppression of the elimination of FcεRI from the cell surface (14, 15). However, the relevance of these observations to normal mast cells was not clear. More importantly, it was not established whether IgE-induced increases in FcεRI expression resulted in enhanced responsiveness to IgE-dependent release of proinflammatory mediators.

In this report, we used in vitro, in vivo, and genetic approaches to examine whether IgE can directly regulate FcεRI expression on the surface of mouse mast cells. We found that IgE can substantially upregulate FcεRI expression on mouse mast cells in vitro or in vivo, and showed that this IgE-dependent enhancement of mouse mast cell FcεRI expression, in turn, can significantly increase the ability of these cells to release proinflammatory and immunoregulatory mediators in response to IgE-dependent activation.

Materials and Methods

Flow Cytometry of Mouse Peritoneal Mast Cells and In Vitro-derived Mouse Mast Cells.

In the mouse, mast cells express two surface receptors that can bind IgE, the high affinity receptor that binds IgE monomers, FcεRI, and FcγRII/III, which can bind IgE immune complexes (17, 18). By contrast, the low affinity IgE receptor, CD23, appears to be restricted to cells other than mast cells (e.g., B cells) in the mouse (18, 19). Because our studies employed monomeric IgE, IgE binding to mouse mast cells under the conditions of our experiments reflects largely, if not entirely, binding of IgE to FcεRI (18). Nevertheless, for flow cytometric analysis of unfractionated freshly isolated mouse peritoneal cells (20), we preincubated the cells with B3B4 (21) and 2.4G2 (18, 22) mAbs for 15 min to block low affinity binding of IgE or other subsequent antibodies to CD23 (on B cells, reference 19) or FcγRII/III (on mast cells or monocytes/macrophages, references 18, 22), respectively. The cells were then incubated at 4°C with a mouse IgE anti-DNP mAb (reference 23, 10 μg/ml) for 50 min, to saturate fully any FcεRI expressed by these cells (18), and then, simultaneously, for the last 25 min, with a biotinylated rat anti– mouse c-kit antibody (PharMingen, San Diego, CA, at 15 μg/ml). After washing once in DMEM (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersberg, MD) supplemented with 5% FCS (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), cells were stained with FITC–rat anti–mouse IgE antibody (PharMingen, at 10 μg/ml) and PE–streptavidin (Sigma Chemical Co., at 14 μg/ml) for 25 min at 4°C. Stained cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur® (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Autofluorescent cells (primarily macrophages) were rejected to identify mast cells (IgE+, c-kit+) clearly. 20,000 peritoneal cells in each sample were analyzed, and at least 100 mast cells were studied to calculate the median value of fluorescence intensity. We confirmed that the gated IgE+, c-kit+ cells were exclusively mast cells by staining cytocentrifuge preparations of the sorted cells with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain and then examining them by light microscopy at ×400.

An instrument setting of the flow cytometer that was appropriate for analysis of peritoneal cells was determined in the first experiment and was used for all such analyses throughout this study. The median values of fluorescence intensity of mast cells were converted to the numbers of molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome units (MESF)1 using Quantum 25 microbeads (Flow Cytometry Standards Co., San Juan, PR) on each day an experiment was performed, as per the specifications of the manufacturer.

For cell culture before flow cytometry, unfractionated peritoneal cells (purity of mast cells assessed by May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain 3–5%) were cultured at 5 × 105 cells/ml in DMEM (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% FCS, 50 ng/ml rat recombinant stem cell factor (rrSCF) (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, reference 20), 2 mM L-glutamine, and antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin).

Bone marrow–derived cultured mouse mast cells (BMCMCs) were generated by culturing femoral bone marrow cells of BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratory, Wilmington, MA) or genetically engineered IgE −/− mice (reference 24, third generation backcross into BALB/c) or corresponding normal (IgE +/+) BALB/c mice, or WBB6F1 +/+ mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), in 20% WEHI-3 cell supernatant–conditioned medium for 4 to 6 wk (25). For flow cytometry, cells were preincubated with 2.4G2 antibody (as above) and then with ascites IgE mAb (as above) or affinity-purified mouse anti-DNP IgE mAb (clone SPE-7; Sigma), at 10 μg/ml, for an additional 50 min at 4°C. After washing, cells were stained with FITC–anti-IgE antibody for 25 min. At least 10,000 BMCMCs were analyzed to obtain each MESF value. The flow cytometry setting for BMCMCs was not changed throughout this study.

Preparations of peritoneal mast cells or bone marrow–derived mast cells were incubated for up to 4–6 d with various concentrations of ascites containing mouse IgE anti-DNP (stock concentration = 506 μg IgE/ml) (23) or IgG2a (Sigma) mAbs, or affinitypurified mouse IgE or IgG2a mAbs (clones SPE-7 and UPC 10, respectively; Sigma), before flow cytometry or analysis of mediator release, as described in Results. Before being used for flow cytometric analysis (see above), cells that had been incubated with IgE or IgG2a mAbs for up to 4 d were washed (in DMEM with 5% FCS) once if they had been incubated in concentrations of mAb of ⩽5.0 μg/ml and twice if they had been incubated with concentrations of mAb of >5.0 μg/ml.

Western Blot Analysis of FcεRI β Chain in Mouse Mast Cells.

For Western blot analysis, 2.5 × 107 of the same BMCMCs used for flow cytometry (i.e., just before analysis, the cells were incubated with excess IgE at 4°C to saturate their FcεRI, see above) were extracted in 0.2 M borate buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and proteinase inhibitors (26) and postnuclear extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with noncoated beads (preclear) and then two times with anti-IgE–coated beads (10 μg affinity-purified rabbit anti-IgE per precipitation), to isolate surface-expressed FcεRI that had bound IgE. Immunoprecipitates were pooled, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, and immunoblotted to Immubilon P (Millipore, Bedford, MA). No antibodies suitable for selectively identifying the mouse FcεRI α chain have been described. Accordingly, Western blotting was performed with the JRK anti-mouse FcεRI β chain mAb (26).

Quantification of Mouse Mast Cell Mediator Release.

For measurements of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) release, BMCMCs (>95% purity) or peritoneal cells were incubated with ascites IgE at 10 μg/ml and [3H]5-HT (NEN, Boston, MA) at 2 μCi/ml for 2 h at 37°C, washed, and 5-HT serotonin release was calculated as the percentage of total incorporated [3H]5-HT present in the cell supernatant 10 min after stimulation with DNP human serum albumin (DNP–HSA) (Sigma), the calcium ionophore A23187 (Sigma), or vehicle at 37°C (27). For IL-6 or IL-4 release, BMCMCs were sensitized with ascites IgE at 10 μg/ml for 50 min at 4°C, and stimulated with DNP–HSA for 4 h at 37°C. IL-6 or IL-4 in the supernatants was measured using ELISA kits (Endogen, Cambridge, MA).

Assessment of the Effect of Administration of IgE In Vivo on Mouse Mast Cell FcεRI Expression.

12–22-wk-old mice were used in four separate in vivo experiments, two with BALB/c mice (data combined in Fig. 7 A), one with untreated IgE −/− and corresponding IgE +/+ mice (Fig. 7 B), and one with antibodytreated IgE −/− mice (Fig. 7 C). Purified mouse IgG2a mAb (Sigma, clone UPC 10) and mouse anti-DNP IgE mAb (Sigma, clone SPE-7) were dialyzed to remove NaN3, centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C, and filtered before use. For i.v. treatment, IgG2a or IgE (100 μg in 0.24 ml PBS) or 0.24 ml of PBS alone was administered to each mouse daily by tail vein. Blood was obtained at time of death (∼18 h after the last i.v. injection) for measurement of total serum IgE concentration by ELISA (28). For assay of serotonin release, peritoneal cells were incubated for 20 h in DMEM containing 10% FCS (27) and then sensitized with IgE, labeled with [3H]5-HT, and stimulated with DNP– HSA as described above.

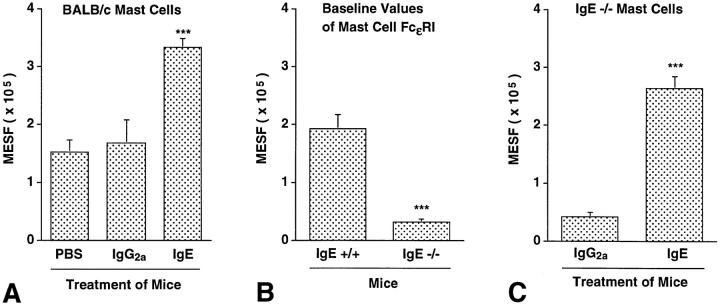

Figure 7.

IgE can regulate levels of peritoneal mast cell FcεRI expression in vivo. (A) FcεRI expression in peritoneal mast cells from BALB/c mice that had been treated for 4 d with a daily i.v. injection of 100 μg of affinity-purified IgE (n = 7) or IgG2a (n = 6) mAb, or vehicle (PBS) alone (n = 4). ***P <0.0001 or <0.005 versus values for PBS- or IgG2atreated mice, respectively. (B) Baseline levels of FcεRI expression on peritoneal mast cells from IgE +/+ (n = 8) and IgE −/− (n = 7) mice. ***P <0.0001 versus values for IgE +/+ cells. (C) FcεRI expression in peritoneal mast cells from IgE −/− mice treated with purified IgE mAb (n = 5) or purified IgG2a mAb (n = 4) as in (A). ***P <0.0001 versus values for cells from IgG2a-treated mice. All values in (A–C) are mean ± SEM.

Statistics.

Unless otherwise specified, all data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and all differences between values were compared by the two-tailed Student's t test (unpaired).

Results

IgE Enhances FcεRI Expression in Mouse Peritoneal Mast Cells In Vitro.

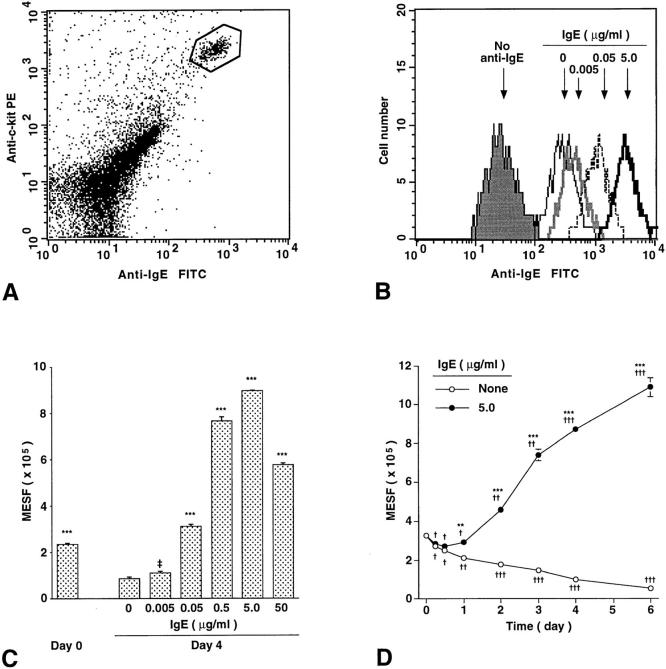

As assessed by flow cytometry to detect binding of IgE (see Materials and Methods), we found that the baseline levels of FcεRI expression on the surface of BALB/c mouse peritoneal mast cells, identified as an IgE+, c-kit+ subpopulation of unfractionated peritoneal cells (Fig. 1 A), were greatly enhanced, in a concentration- (Fig. 1, B and C) and time- (Fig. 1 D) dependent manner, upon incubation of the cells in vitro with a mouse monoclonal IgE antibody. Moreover, FcεRI expression progressively diminished when peritoneal mast cells were incubated in vitro without added IgE (Fig. 1 D). As a result, levels of FcεRI expression in peritoneal mast cells incubated for 6 d with IgE at 5 μg/ml (i.e., in the range observed in the serum of parasite-infected mice, reference 28) were 20-fold higher than those in cells incubated for 6 d without IgE (Fig. 1 D). And mast cells incubated for 4 d with a concentration of IgE (0.05 μg/ml) comparable to that present in the serum of normal mice (28, 29) had levels of FcεRI expression that were 3.6-fold those in cells incubated for 4 d without IgE (Fig. 1 C).

Figure 1.

IgE enhances mouse peritoneal mast cell FcεRI expression in vitro in a time- and dose-dependent manner. (A) Identification of peritoneal mast cells (gated, in box) by flow cytometry. Freshly isolated peritoneal cells of retired breeder BALB/c mice were stained for the expression of surface IgE receptor and c-kit. The gated cells were sorted and confirmed microscopically as 100% mast cells. (B–D) Regulation of surface FcεRI expression on peritoneal mast cells by ascites IgE ex vivo. (B) Peritoneal cells isolated from BALB/c mice were cultured for 4 d without IgE or with IgE at 0.005, 0.05, or 5.0 μg/ml, incubated with excess IgE at 4°C for 50 min to saturate mast cell FcεRI, and then mast cell surface FcεRI expression was analyzed by flow cytometry. The background fluorescence intensity of mast cells stained only for c-kit is also shown (no anti-IgE). (C) Dose-dependent effect of IgE on surface FcεRI expression on peritoneal mast cells. Peritoneal cells from 5 BALB/c mice were combined, cultured with or without IgE for 4 d, and analyzed by flow cytometry for surface FcεRI. MESF, molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome units (see Materials and Methods). All data are mean ± SEM (n = 3); ‡P = 0.076, ***P <0.0001 versus values for cells cultured without IgE for 4 d. (D) Time course of changes in mast cell surface FcεRI expression in peritoneal cells (combined from 8 BALB/c mice) cultured with or without IgE (5.0 μg/ml). All data are mean ± SEM (n = 3); **P <0.001, ***P <0.0001 versus values at the same time point for cells cultured without IgE; † P <0.05, †† P <0.001, ††† P <0.0001 versus baseline (day 0) value.

IgE Enhances FcεRI Expression in Mouse Bone Marrow– derived Cultured Mast Cells (BMCMCs) In Vitro.

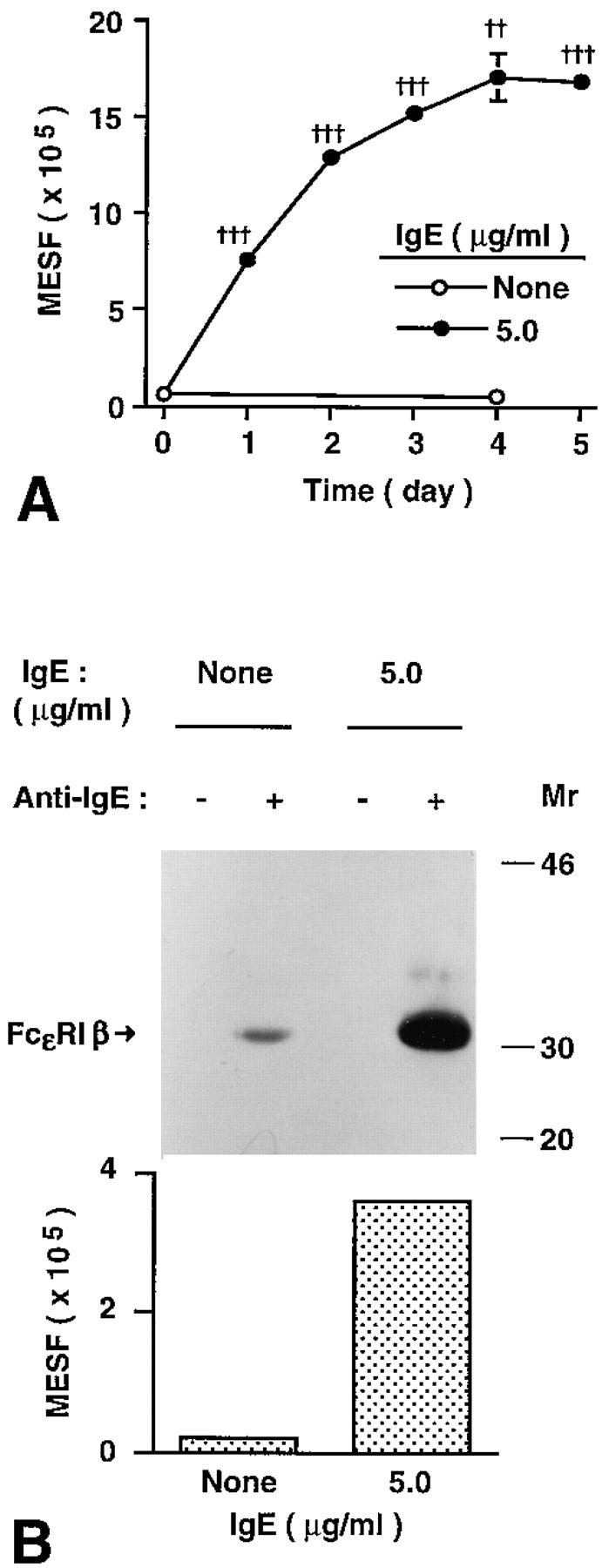

Unfractionated peritoneal cells contain cells other than mast cells, some of which may have influenced the effect of IgE on peritoneal mast cell FcεRI expression. Therefore, we next assessed whether IgE also enhanced surface expression of FcεRI in essentially pure populations of immature mouse mast cells derived in vitro from the bone marrow cells of IgE null mice (IgE −/− mice) or the corresponding normal (IgE +/+) BALB/c mice (24). Incubation with IgE (at 5 μg/ml) resulted in a marked elevation (32-fold at day 4) in FcεRI expression in BMCMCs from IgE +/+ mice (Fig. 2 A). Essentially identical results were obtained in two additional experiments with BMCMCs derived from IgE −/− mice (data not shown), cell preparations which could not have contained any source of endogenous mouse IgE (i.e., small numbers of contaminating B cells).

Figure 2.

IgE enhances FcεRI expression in mouse bone marrow–derived cultured mast cells (BMCMCs) in vitro. (A) Kinetics of IgE-induced changes in surface FcεRI expression in BMCMCs. BMCMCs (always >95% purity at 4–5 wk of culture) from BALB/c (IgE +/+) mice were cultured with or without ascites IgE (at 5.0 μg/ml) for the indicated times. BMCMCs were stained only for FcεRI (with FITC–IgE) and were analyzed by flow cytometry using a different instrument setting from that in Fig. 1. All data are mean ± SEM (n = 3); †† P <0.001, ††† P <0.0001 versus value at day 0. (B) Upregulation of surface FcεRI protein by IgE. BMCMCs from IgE −/− mice were cultured with or without ascites IgE at 5 μg/ml for 21 h. After sensitization with IgE at 10 μg/ ml for 30 min at 4°C to saturate surface FcεRI, cells (n = 2) were analyzed by flow cytometry for FcεRI expression (see Materials and Methods) and by immunoprecipitation with anti-IgE and Western blot (2.5 × 107 BMCMCs per lane) to assess levels of surface-expressed FcεRI β chain. The difference of detected FcεRI expression between cells incubated with or without IgE was 14fold (by flow cytometry) and 17-fold (by Western blot), respectively.

Studies of cells transfected with either mouse FcεRI, FcγRII, or FcγRIII indicate that washing of the cells prior to flow cytometric analysis does not significantly remove IgE from FcεRI, but can largely eliminate IgE or IgG from FcγRII/FcγRIII (18). Accordingly, under the conditions of our experiments, the IgE binding that we assessed by flow cytometry reflected largely, if not entirely, the binding of IgE to FcεRI. Nevertheless, we used Western blotting to assess directly the extent to which the β chain of the FcεRI was associated with the BMCMC surface receptors that bound IgE in our experiments. We found that the increase in IgE binding that was detected by flow cytometry after incubation of BMCMCs with IgE (at 5.0 μg/ml) for 21 h (∼14-fold increase versus BMCMCs that had not been incubated with IgE) directly paralleled the amount of FcεRI β chain obtained from anti-IgE immunoprecipitates of these cells (an increase of ∼17-fold versus control BMCMCs that had not been incubated with IgE) (Fig. 2 B). These data provide further evidence that the increased IgE-binding ability, which we detected on the surface of mast cells that had been incubated with IgE, indeed reflected increased surface expression of FcεRI.

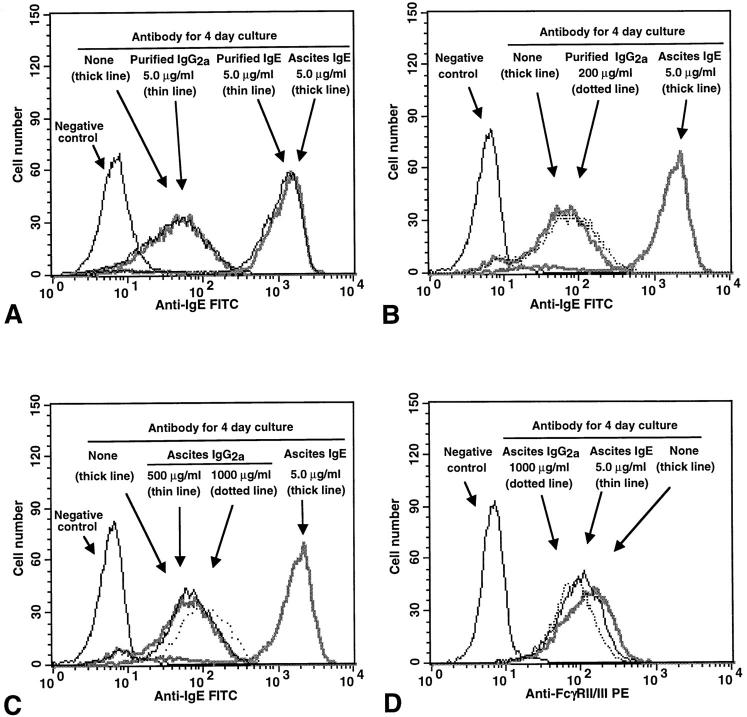

The mast cells that were incubated with the highest concentration of ascites IgE that was used routinely in our experiments (i.e., 5 μg IgE/ml) were exposed to an ∼100-fold dilution of the stock preparation of ascites. However, this ascites-derived IgE preparation also significantly enhanced mast cell FcεRI expression even when tested at dilutions of 10,000- to 100,000-fold (to yield IgE concentrations of 0.05 or 0.005 μg/ml, respectively, e.g., see Fig. 1 C). Nevertheless, to rule out the possibility that some constituent of the ascites preparation other than IgE might have significantly influenced our results, we incubated aliquots of the same population of BALB/c BMCMCs for 4 d with either ascites or affinity-purified IgE at 5 μg IgE/ml. We found that either preparation of IgE markedly increased the FcεRI expression of the cells, and to essentially equivalent levels (Fig. 3 A). Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments. By contrast, incubation of such BMCMCs for 4 d with a mouse IgG2a mAb at 5 μg/ml had no detectable effect on the cells' surface expression of FcεRI (Fig. 3 A). A separate experiment gave the same result.

Figure 3.

Effects of various mouse IgE or IgG2a mAb preparations on surface expression of (A–C) FcεRI or (D) FcγRII/III in BMCMCs. BALB/c BMCMCs were cultured with or without various concentrations of mouse IgE or IgG2a mAb, either as diluted ascites preparations (Ascites IgE or IgG2a) or as affinity-purified mAb preparations (Purified IgE or IgG2a), for 4 d. Negative control in (A–C), cells cultured for 4 d without IgE or IgG2a and then incubated with FITC–anti-IgE without prior sensitization with IgE. (A) Incubation with either purified or ascites IgE mAb (at 5.0 μg IgE/ml) resulted in an equivalent increase in the FcεRI expression of the cells, whereas cells incubated with either purified IgG2a (at 5.0 μg/ml) or no antibody (none) exhibited similar low levels of staining. (B and C) Incubation with high concentrations of purified (B) or ascites (C) IgG2a resulted in little or no increase in BMCMC FcεRI expression, in comparison with positive control BMCMCs that had been incubated with IgE at 5.0 μg/ml. (D) Incubation for 4 d with IgE or IgG2a had little or no effect on the expression of FcγRII/III by BMCMCs. Negative control in (D), cells cultured for 4 d without IgE or IgG2a and then incubated with a rat IgG2b mAb of irrelevant specificity, instead of the rat 2.4G2 anti–mouse FcγRII/III mAb, before staining with the PE– anti-rat IgG antibody. The same results were obtained with ascites IgE (shown) or purified IgE (not shown).

We also tested the effects of a 4-d incubation of BALB/c BMCMCs with IgG2a at 5–1000 μg/ml. As expected, we found that incubation with ascites IgE at 5 μg/ml markedly increased BMCMC expression of FcεRI (Fig. 3 B), whereas either affinity-purified IgG2a, at 5 or 100 μg/ml (data not shown) or 200 μg/ml (Fig. 3 B), or ascites IgG2a, at 5 or 100 μg/ml (data not shown) or 500 or 1,000 μg/ml (Fig. 3 C), had little or no effect on FcεRI expression.

The effect of IgE on BMCMC FcεRI expression appeared to be specific, in that cells incubated for 4 d with IgE at 5 μg/ml exhibited no detectable change in their surface expression of FcγRII/III, as assessed by flow cytometry with the 2.4G2 antibody (Fig. 3 D). A 4-d incubation of BMCMCs with purified IgG2a mAb (at 5 or 200 μg/ ml, data not shown) or ascites IgG2a mAb (at 1,000 μg/ml; Fig. 3 D) also had little or no effect on the cells' surface expression of FcγRII/III, as assessed by flow cytometry.

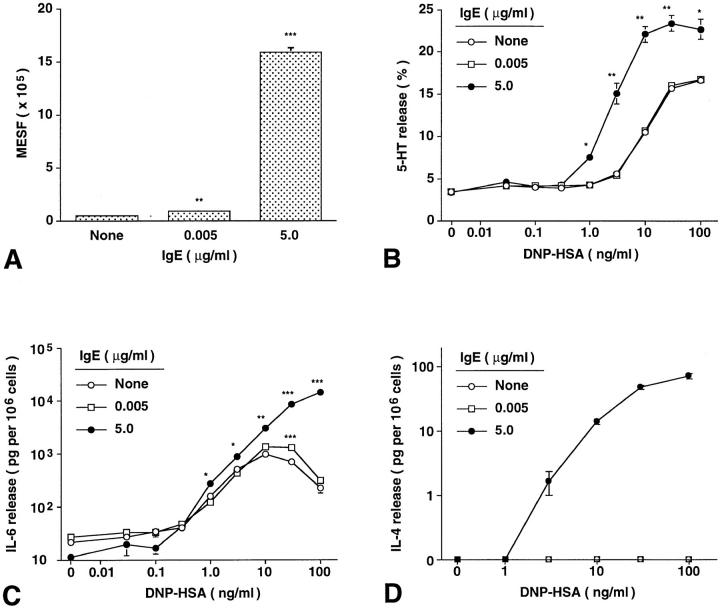

IgE-dependent Enhancement of Mast Cell FcεRI Expression Results in Enhancement of IgE-dependent Mast Cell Mediator Release.

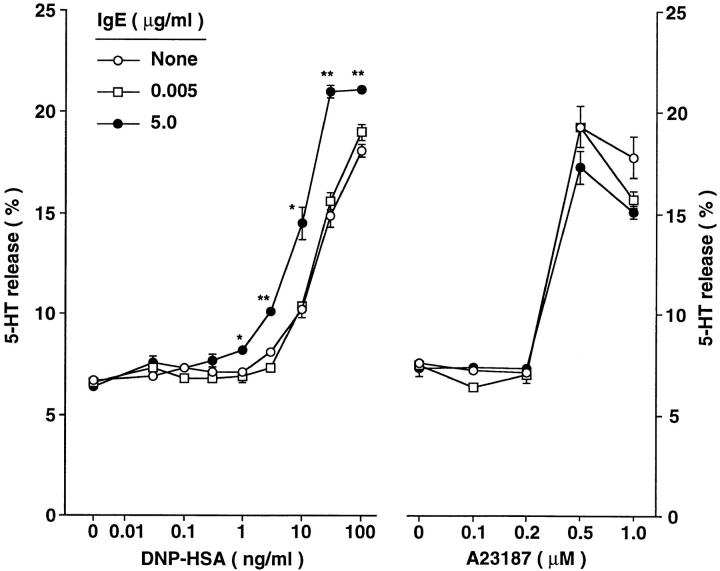

To assess the functional significance of IgE-dependent upregulation of mast cell FcεRI expression, we incubated BALB/c BMCMCs with 0, 0.005, or 5 μg/ml of IgE for 4 d, then passively sensitized the cells with excess monoclonal anti-DNP IgE (10 μg/ml) for 2 h, and then challenged the cells with various concentrations of specific antigen (DNP–HSA) and measured release of the cytoplasmic granule-associated mediator serotonin (5-HT) and the cytokines, IL-6 and IL-4. As shown in Fig. 4, the IgE-induced enhancement of FcεRI expression (Fig. 4 A) was associated with a significantly enhanced functional responsiveness to antigen stimulation, as assessed either by 5-HT release (Fig. 4 B) or IL-6 (Fig. 4 C) or IL-4 (Fig. 4 D) production. The results shown in Fig. 4 are representative of those obtained in three other experiments in which we assessed 5-HT release and one other experiment in which we assessed IL-6 and IL-4 release.

Figure 4.

IgE-induced enhancement of mouse BMCMC FcεRI expression increases the ability of these cells to release mediators in response to IgE and specific antigen. Effects of IgE-induced changes in BMCMC FcεRI expression (A) on IgE- and antigen-dependent release of (B) serotonin (5-HT), (C) IL-6, and (D) IL-4. BALB/c BMCMCs were cultured without IgE or with ascites IgE at 0.005 or 5.0 μg/ml for 4 d. All values are mean ± SEM (n = 3). (A–D) *P <0.05, **P <0.005, ***P <0.0001 versus corresponding values for cells cultured without IgE. Compared with values at 0 DNP–HSA for cells that had been incubated with the same concentration of IgE for 4 d, significant (P <0.01) release of 5-HT first occurred at 1.0 versus 3 ng/ml DNP–HSA for cells incubated with IgE at 5.0 versus 0.005 or 0 ng/ml, respectively. For IL-6 release, the corresponding values were 0.3 ng/ml DNP–HSA for cells incubated with IgE at 5.0 or 0.005 μg/ml versus 1 ng/ml DNP–HSA for cells incubated without IgE. Detectable release of IL–4 occurred at 3.0 ng/ml DNP– HSA for cells incubated with IgE at 5.0 μg/ml, but not at all in cells incubated with IgE at 0.005 or 0 ng/ml. Similar results were observed in another experiment using IgE −/− BMCMCs.

Notably, IgE-dependent enhancement of mast cell FcεRI expression both decreased the concentration of antigen required to elicit IgE-dependent mediator release and markedly increased mediator secretion at a given antigen concentration (Fig. 4, B–D). For example, when challenged with antigen at 30 ng/ml, BMCMCs that had been incubated for 4 d with IgE at 5.0 μg/ml exhibited ∼60% greater specific release of 5-HT (Fig. 4 B) and ∼6-fold greater release of IL-6 (Fig. 4 C) than did mast cells which had been incubated for 4 d with IgE at 0.005 μg/ml. The effect on IL-4 production was especially striking, in that the only cells which exhibited detectable release of IL-4 upon challenge with specific antigen were those which had been incubated for 4 d with IgE at 5.0 μg/ml (Fig. 4 D). The same finding was obtained in an additional experiment with BMCMCs derived from IgE −/− mice (data not shown).

The effect of a 4-d incubation with IgE on the ability of BMCMCs to release mediators in response to challenge with IgE and antigen did not reflect a general enhancement of the secretory responsiveness of the cells, in that there was no significant parallel increase in the ability of the cells to release 5-HT in response to stimulation with the calcium ionophore A23187 (Fig. 5). The results shown in Fig. 5 are representative of those obtained in two separate experiments with BMCMCs and one with peritoneal mast cells.

Figure 5.

Serotonin (5-HT) release from BMCMCs exhibiting different levels of surface expression of FcεRI, after challenge with various concentrations of either specific antigen (DNP–HSA) or the calcium ionophore, A23187. WBB6F1 +/+ BMCMCs were cultured without IgE or with ascites IgE at 0.005 or 5.0 μg/ml for 4 d before passive sensitization and antigen challenge or challenge with A23187. Zero in the A23187 experiment refers to cells incubated without A23187 but in the highest concentration of vehicle used for these studies (DMSO at 0.1%). *P <0.05, **P <0.001, versus corresponding values for cells cultured without IgE. The data shown (mean ± SEM; n = 3 per point) are representative of the results obtained in two separate experiments using WBB6F1 +/+ BMCMCs.

The IgE-dependent Increase in Mast Cell FcεRI Expression Has Cycloheximide-sensitive and Cycloheximide-insensitive Components.

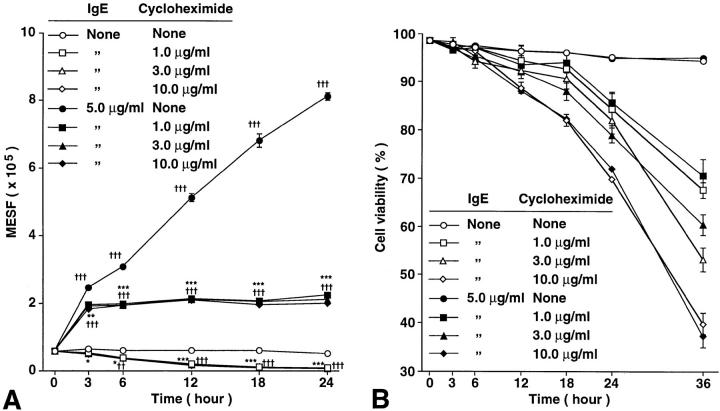

In RBL cells, the ∼50–90% increase in FcεRI surface expression that occurs as a result of incubation of the cells with IgE for 4 h is insensitive to inhibition with cycloheximide at 10 μg/ml (14). This, and other lines of evidence, support the hypothesis that the modest change in FcεRI surface expression observed in this setting does not require protein synthesis but instead largely or entirely reflects the reduced loss from the cell surface of FcεRI that are occupied by IgE (14, 15). In confirmation of these observations with rat basophilic leukemia (RBL) cells, we found that incubation of BMCMCs with cycloheximide (at 1, 3, or 10 μg/ml) had little or no effect on the roughly fourfold increase in FcεRI surface expression that occurred in the first 3 h after incubation of the cells with IgE at 5 μg/ml (Fig. 6 A). However, cycloheximide treatment profoundly suppressed the subsequent, more sustained, increase in FcεRI expression by these cells (Fig. 6 A). Cycloheximide treatment also resulted in a significant reduction in surface expression of FcεRI in BMCMCs that were maintained in culture without added IgE (Fig. 6 A). Similar results were obtained in a second experiment.

Figure 6.

Time course of changes in (A) the baseline or IgE-induced levels of FcεRI expression, and (B) cell viability, as assessed by Trypan blue staining, of WBB6F1+/+ BMCMCs cultured with or without mouse IgE mAb (at 5.0 μg/ml) and with or without various concentrations of cycloheximide (see Materials and Methods). All data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). (A) *P <0.05, **P <0.001, ***P <0.0001 versus values at the same timepoint for cells cultured with the same concentration of IgE, but without cycloheximide; † P <0.05, †† P <0.001, ††† P <0.0001 versus initial baseline (zero h) value. (B) Compared with values at the same timepoint for cells cultured with the same concentration of IgE, but without cycloheximide, a significant (P <0.05) reduction in cell viability first occurred at 18, 12, or 6 h for cells cultured with cycloheximide at 1, 3, or 10 μg/ml, respectively. Similar results were observed in two experiments using BALB/c BMCMCs or Cl.MC/C57.1 cloned mast cells (18).

Note that the cycloheximide-insensitive and cycloheximide-sensitive components of the IgE-induced enhanced surface expression of FcεRI were detectable at relatively early intervals after addition of IgE (3 h or 6–12 h, respectively; Fig. 6 A), before the cells treated with cycloheximide began to exhibit substantially diminished viability, as revealed by staining with Trypan blue (Fig. 6 B). Moreover, the effects of cycloheximide on FcεRI surface expression were essentially identical in BMCMCs treated with the drug at 1, 3, or 10 μg/ml (Fig. 6 A), whereas, as expected, cells treated with higher concentrations of the agent exhibited more toxicity at late intervals of culture than did those treated with cycloheximide at 1 μg/ml (Fig. 6 B).

IgE Regulates the Expression of Mouse Mast Cell FcεRI In Vivo.

We performed four experiments to investigate whether IgE is an important regulator of mast cell FcεRI expression in vivo. In two experiments, affinity-purified mouse IgE mAb (100 μg/day), or either affinity-purified mouse IgG2a mAb (100 μg/day) or vehicle (PBS) alone, were administered to BALB/c mice intravenously daily for 4 d, and peritoneal mast cells were analyzed for FcεRI by flow cytometry ∼18 h after the last injection. Administration of IgE, but not IgG2a, resulted in a greater than twofold enhancement of peritoneal mast cell expression of FcεRI (Fig. 7 A), whereas neither IgE nor IgG2a had any significant effect on mast cell expression of FcγRII/III (data not shown).

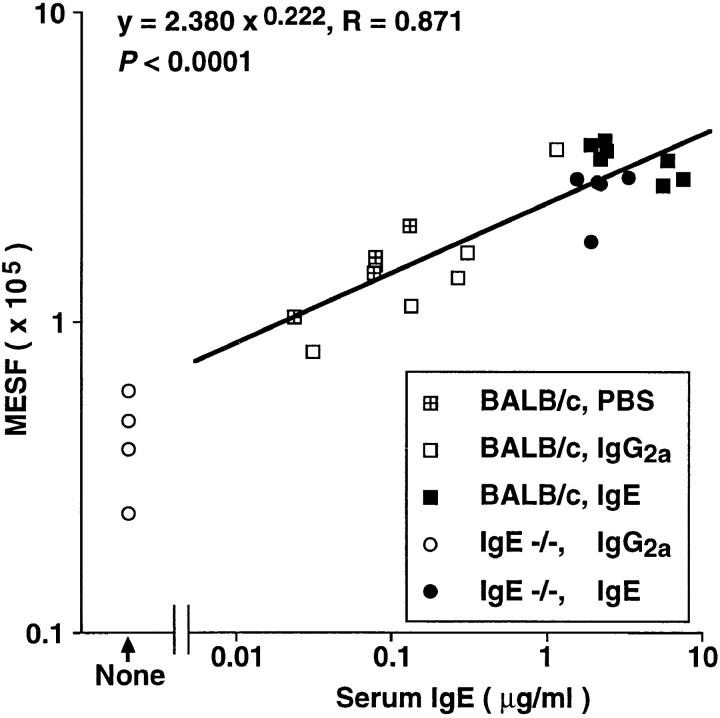

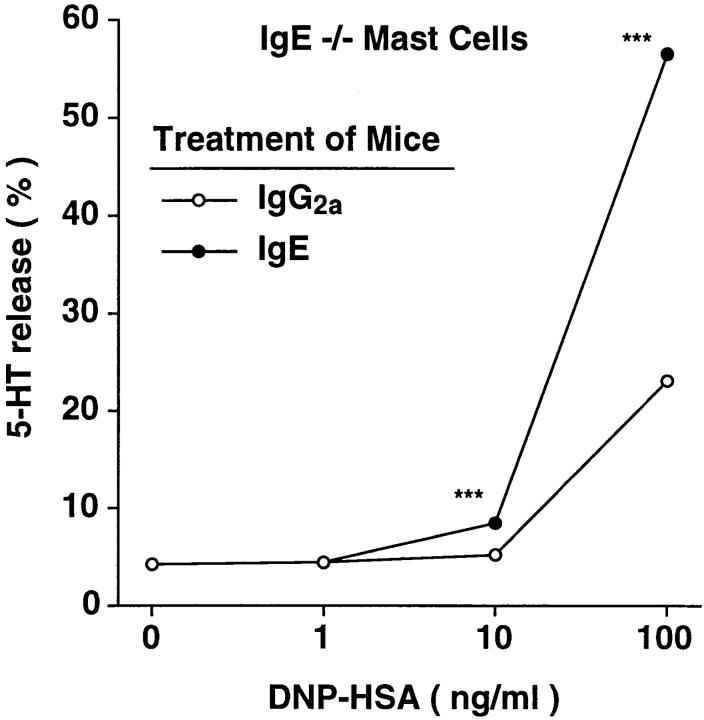

Next, we assessed baseline levels of FcεRI expression in peritoneal mast cells of untreated IgE −/− versus IgE +/+ mice, and found that FcεRI expression was reduced by ∼83% in mast cells from IgE −/− mice as compared with those from wild-type mice (Fig. 7 B). We also found that administration of IgE (but not IgG2a) antibody resulted in a marked increase in FcεRI expression by IgE −/− mouse peritoneal mast cells (compare Fig. 7, B and C), whereas treatment with either antibody had no significant effect on mast cell FcγRII/III expression (data not shown). Moreover, there was a strong positive correlation, in the mice shown in Fig. 7, A and C, between the log10 of the serum IgE concentration at sacrifice and levels of mast cell FcεRI expression (R = 0.871, P <0.0001) (Fig. 8). And when the peritoneal mast cells removed from the mice shown in Fig. 7 C were tested for their ability to release 5-HT upon antigen challenge in vitro, the response of mast cells from mice that had been injected with IgE was markedly enhanced compared with that of the control cells from the IgG2a-treated mice (Fig. 9).

Figure 8.

Correlation of serum IgE concentration at sacrifice and surface FcεRI expression of peritoneal mast cells in the mice from the experiments depicted in Fig. 7 (A and C). The genotypes of the mice, and the treatment which they received (PBS, IgE, or IgG2a, i.v. daily for 4 d) are depicted in the symbol key in the figure. Note that the correlation coefficient was calculated based on all data except those from IgG2a-treated IgE −/− mice, which were devoid of serum IgE; as a result, n = 22.

Figure 9.

Upregulation of secretory function of IgE −/− peritoneal mast cells after administration of IgE in vivo. Peritoneal cells were combined from two of the IgE −/− mice that had been treated with affinity-purified IgG2a mAb and four of the IgE −/− mice that had been treated with purified IgE mAb from Fig. 7 C. IgE- and antigen-induced 5-HT release was determined for each group of cells (n = 3 per point) as in Fig. 4 B. ***P <0.0001 versus corresponding values for cells from IgG2atreated mice.

Discussion

Exposure to monomeric IgE in vitro markedly upregulated the ability of mature mouse peritoneal mast cells or mouse BMCMCs or cloned mast cells to bind IgE. Two separate lines of evidence indicate that this response largely, if not entirely, reflected the increased surface expression of FcεRI. First, while mouse mast cells also express FcγRII/ III (17, 18), which can bind IgE immune complexes (18), virtually all of the binding of monomeric IgE to mouse mast cells that is detectable under the conditions used in our experiments reflects binding of the ligand to a single class of high affinity binding sites, i.e., FcεRI (18). Second, we used anti-IgE to immunoprecipitate surface-bound IgE, and associated IgE receptors, from lysates of BMCMCs that had been first incubated with or without IgE at 5 μg/ml for 21 h and then exposed briefly to excess IgE just before recovery for flow cytometry and Western blot analysis. We found that, in comparison to aliquots of the same mast cell population that had been incubated without IgE, mast cells that had been incubated for 21 h with IgE exhibited an ∼14-fold increase in IgE binding by flow cytometry and an ∼17-fold increase in IgE- and cell surface–associated FcεRI β chain by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2 B). Thus, the IgEinduced increase in IgE binding that was detected in BMCMCs by flow cytometry was directly proportional to the amount of FcεRI β chain obtained from anti-IgE immunoprecipitates of the same cells.

The IgE-induced changes in levels of mast cell FcεRI surface expression that were detected in our experiments reflect the operation of two processes, which can be distinguished by their sensitivity to inhibition by cycloheximide. In confirmation of the findings of Furuichi et al. with RBL cells (14), we found that the earliest component of the IgEdependent increase in BMCMC FcεRI expression (which occurred within 3 h of addition of IgE) was largely resistant to inhibition by cycloheximide. By contrast, virtually all of the subsequent sustained, and striking, upregulation of FcεRI expression in these cells was ablated by cycloheximide. The most straightforward interpretation of these findings, which we favor, is that the initial, cycloheximide-insensitive, component of the response reflects IgE-dependent suppression of the loss of preformed FcεRI expressed on the cell surface (14, 15), whereas the sustained, cycloheximide-sensitive component is more dependent on protein synthesis, e.g., of new receptors.

To address the in vivo relevance of our findings, we performed experiments in normal mice and mice that had been rendered genetically IgE deficient. IgE −/− mice expressed baseline levels of FcεRI that were 83% reduced compared with those of normal (IgE +/+) mice. Furthermore, both IgE −/− and normal mice exhibited significant increases in the levels of peritoneal mast cell FcεRI expression after i.v. treatment with IgE. These findings demonstrate that IgE is a major regulator of mouse mast cell FcεRI expression in vivo. Indeed, analysis of data from the IgE-treated IgE −/− mice and the IgE +/+ mice that had been treated with IgE, IgG2a, or PBS revealed a striking positive correlation between the log10 of the serum IgE concentration at sacrifice and the log10 of the molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome (MESF) values for FcεRI expression by peritoneal mast cells from the same mice (R = 0.871, P <0.0001). Thus, our findings in mice directly support the general form of the hypothesis that was originally proposed by Malveaux et al. with respect to human basophils (13), namely, that circulating levels of IgE can influence levels of effector cell surface expression of FcεRI.

Nevertheless, mast cells from IgE −/− mice exhibited detectable, albeit greatly reduced, levels of FcεRI on their surface (Fig. 7 C), indicating that factors other than IgE must also contribute to the regulation of mouse mast cell FcεRI expression. IL-4 has multiple effects that augment IgE-dependent immune responses in mice; it is required for normal IgE responses (30, 31) and can also promote the expansion of certain mouse mast cell populations (32, 33). Moreover, peritoneal mast cells of IL-4 −/− mice exhibit fewer FcεRI than do those of IL-4 +/+ mice (34). IL-4 can also upregulate levels of mRNA for the FcεRI α chain in human eosinophils (35). We found that recombinant mouse IL-4 (at 10 ng/ml) slightly enhanced peritoneal mast cell FcεRI expression over that induced by IgE alone, but had little or no effect in the absence of IgE (data not shown). In light of this finding, one may speculate that the reduction in mast cell FcεRI expression in IL-4 −/− mice might reflect, at least in part, the low levels of IgE in these animals (31, 34).

One of the most significant aspects of our study is the observation that changes in the concentration of IgE antibody not only can regulate the level of cell surface expression of FcεRI on mouse mast cells, but that this IgE-dependent upregulation of mast cell FcεRI expression is functionally significant. This result was, in some respects, unexpected. In their studies of human basophils derived from patients with different concentrations of circulating IgE, Conroy et al. (11) detected no significant differences in the histamine release responses induced by different concentrations of antiIgE in basophils from nonatopic donors, which expressed as few as 3,900 IgE molecules/basophil, or allergic donors, which expressed up to 500,000 IgE molecules/basophil. Moreover, basophils from donors whose cells expressed approximately the same amounts of cell-bound IgE varied greatly in their sensitivity to anti-IgE–induced histamine release, perhaps reflecting a wide spectrum of intrinsic releasability of human basophils derived from different individuals (11).

By contrast, we found that IgE concentrations can regulate the expression of FcεRI by mouse mast cells within a range that has significant consequences with respect to IgEdependent effector cell function. Compared with mast cells that had been incubated with levels of monomeric IgE similar to those present in the sera of some normal mice (i.e., 0.005 μg/ml), mast cells that had been incubated with concentrations of IgE in the range observed in the sera of parasite-infected mice (i.e., 5.0 μg/ml) exhibited significant mediator release at lower concentrations of antigen and also gave significantly greater release of mediators at given higher concentrations of antigen. Thus, IgE-dependent upregulation of mast cell FcεRI expression significantly enhanced both the sensitivity and the intensity of the secretory response of the cells to antigen challenge.

This effect was especially remarkable with respect to cytokine production. Thus, in comparison with cells that had been incubated for 4 d with IgE at 0.005 μg/ml, BMCMCs that had been incubated for 4 d with IgE at 5.0 μg/ml exhibited ∼60% greater maximal release of the preformed mediator, serotonin, but ∼6-fold greater release of the cytokine IL-6 (Fig. 4, B and C). The effect of IgE incubation on the ability of BMCMCs to produce IL-4 was even more striking. Substantial IL-4 production in response to antigen challenge was detected in BMCMCs that had been incubated for 4 d with IgE at 5.0 μg/ml, but was not detectable at all in cells that had been incubated for 4 d before antigen challenge either without IgE or with IgE at 0.005 μg/ml. The ELISA assay used for our studies has a lower limit of detection of <5 pg/ml of IL-4. It is possible (and perhaps likely) that different conditions of passive sensitization before antigen challenge, or the use of more sensitive indices of IL-4 production, may have permitted us to detect IgEdependent IL-4 production by BMCMCs that had not been incubated with high concentrations of IgE for 4 d before further passive sensitization and antigen challenge (7, 36, 37). However, under the conditions employed in our experiments, incubation of BMCMCs with IgE at 5.0 μg/ml for 4 d clearly markedly enhanced the ability of these cells to release IL-4 in response to challenge with IgE and specific antigen.

Taken together, our observations identify a novel and potentially important mechanism for enhancing both the sensitivity and intensity of IgE-dependent immune responses. Indeed, because IL-4 can markedly enhance the generation of IgE responses in mice (30, 31), it is even possible that IgE-dependent upregulation of FcεRI expression by mouse mast cells, and subsequent enhancement of IgE- and antigen-dependent mast cell IL-4 production, may constitute a previously unrecognized positive feedback loop in the expression of IgE-dependent immune responses.

While the regulation of IgE production is complex, potentially involving multiple genetic and environmental factors, serum levels of IgE typically are greatly increased during parasite infections and are also elevated in most patients with allergic diseases (38–42). Our findings suggest that any mechanism that results in the substantial elevation of IgE levels may also result in significantly enhanced IgE-dependent effector cell function. Furthermore, no matter what may be the precise minimum number of cross-linked FcεRI that are required to trigger mast cell or basophil mediator release (43, 44), cells that express increased numbers of FcεRI on their surface can be sensitized adequately with larger numbers of different IgE species of distinct antigen specificities. Thus, increased expression of FcεRI by mast cells would also permit each cell to be simultaneously sensitized to respond to a larger number of different antigens.

In the context of acquired immune responses to parasites, IgE-dependent enhancement of mast cell FcεRI expression would be expected to benefit the host. Unfortunately, the same mechanisms might also increase the severity of allergic diseases. Our preliminary experiments indicate that IgE can also increase surface expression of FcεRI on in vitro-derived human mast cells (45). Accordingly, it will be of great interest to assess to what extent IgE-dependent upregulation of FcεRI expression, as here identified in mouse mast cells, also occurs in human FcεRI+ cells, and, if so, to determine whether the ability of IgE to regulate FcεRI can be exploited therapeutically in the management of allergic disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Fox, S. Fish, and H.-Y. Park for technical assistance, F.-T. Liu and D.H. Katz for H-1-DNPε-26 hybridoma cells, K.E. Langley and AMGEN Inc. for rrSCF164, D.H. Conrad for B3B4 antibody, and J.J. Costa, M. Tsai, and B.K. Wershil for a critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI/CA-23990 and CA/AI-72074 (S.J. Galli), GM-53950 (J.-P. Kinet), K08 AI-01253 (H.C. Oettgen) and AI-26150 (I.M. Katona), and Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Protocol RO 86AB (to I.M. Katona).

Footnotes

Note added in proof: While this manuscript was in preparation, an in vitro study of mouse BMCMCs was published which contains results similar to some of the findings reported herein (Hsu, C., and D. MacGlashan, Jr. 1996. IgE antibody up-regulates high affinity IgE binding on murine bone marrow derived mast cells. Immunol. Lett. 52:129–134).

M. Yamaguchi and C.S. Lantz are co-first authors.

1 Abbreviations used in this paper: BMCMCs, mouse bone marrow–derived cultured mast cells; DNP-HSA, DNP human serum albumin; MESF, molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome units; RBL cells, rat basophilic leukemia cells; rrSCF, recombinant rat stem cell factor164; SCF, stem cell factor.

References

- 1.Ishizaka T, Ishizaka K. Activation of mast cells for mediator release through IgE receptors. Prog Allergy. 1984;34:188–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarrett, E.E.E., and H.R.P. Miller. 1982. Production and activities of IgE in helminth infection. In Progress in Allergy. Vol. 31: Immunity and Concomitant Immunity in Infectious Diseases. P. Kallós, volume editor. S. Karger, Basel. 178–233. [PubMed]

- 3.Matsuda H, Watanabe N, Kiso Y, Hirota S, Ushio H, Kannan Y, Azuma M, Koyama H, Kitamura Y. Necessity of IgE antibodies and mast cells for manifestation of resistance against larval Haemaphysalis longicornisticks in mice. J Immunol. 1990;144:259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bochner BS, Lichtenstein LM. Anaphylaxis. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1785–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106203242506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravetch JV, Kinet J-P. Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:457–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaven MA, Metzger H. Signal transduction by Fc receptors: the FcεRI case. Immunol Today. 1993;14:222–226. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90167-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul WE, Seder RA, Plaut M. Lymphokine and cytokine production by FcεRI+ cells. Adv Immunol. 1993;53:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saxon, A., D. Diaz-Sanchez, and K. Zhang. 1996. The allergic response in host defense. In Clinical Immunology: Principles and Practice. Vol. 1. R.R. Rich, T.A. Fleisher, B.D. Schwartz, W.T. Shearer, and W. Strober, editors. Mosby— Year Book, Inc., St. Louis. 847–862.

- 9.Dombrowicz D, Flamand V, Brigmann KK, Koller BH, Kinet J-P. Abolition of anaphylaxis by targeted disruption of the high affinity immunoglobulin E receptor FcεRI α chain gene. Cell. 1993;75:969–975. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90540-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takai T, Li M, Sylvestre D, Clynes R, Ravetch JV. FcγR γ chain deletion results in pleiotropic effector cell defects. Cell. 1994;76:519–529. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conroy MC, Adkinson NF, Jr, Lichtenstein LM. Measurements of IgE on human basophils: relation to serum IgE and anti-IgE-induced histamine release. J Immunol. 1977;118:1317–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stallman PJ, Aalberse RC, Bruhl PC, Van Elven EH. Experiments on the passive sensitization of human basophils, using quantitative immunofluorescence microscopy. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1977;54:364–373. doi: 10.1159/000231849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malveaux FJ, Conroy MC, Adkinson NF, Jr, Lichtenstein LM. IgE receptors on human basophils. Relationship to serum IgE concentration. J Clin Invest. 1978;62:176–181. doi: 10.1172/JCI109103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuichi K, Rivera J, Isersky C. The receptor for immunoglobulin E on rat basophilic leukemia cells: Effect of ligand binding on receptor expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1522–1525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.5.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quarto R, Kinet J-P, Metzger H. Coordinate synthesis and degradation of the α-, β-, and γ-subunits of the receptor for immunoglobulin E. Mol Immunol. 1985;22:1045–1051. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(85)90107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seldin DC, Adelman S, Austen KF, Stevens RL, Hein A, Caulfield JP, Woodbury RG. Homology of the rat basophilic leukemia cell and the rat mucosal mast cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3871–3875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benhamou M, Bonnerot C, Fridman WH, Daëron M. Molecular heterogeneity of murine mast cell Fcγ receptors. J Immunol. 1990;123:3071–3077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takizawa F, Adamczewski M, Kinet J-P. Identification of the low affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E on mouse mast cells and macrophages as FcγRII and FcγRIII. J Exp Med. 1992;176:469–476. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conrad DH. FcεRII/CD23: The low affinity receptor for IgE. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:623–645. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai M, Takeishi T, Thompson H, Langley KE, Zsebo KM, Metcalfe DD, Geissler EN, Galli SJ. Induction of mast cell proliferation, maturation, and heparin synthesis by the rat c-kit ligand, stem cell factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6382–6386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao M, Lee W, Conrad D. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody directed against the murine B lymphocyte receptor for IgE. J Immunol. 1987;138:1845–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unkeless JC. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody directed against mouse macrophage and lymphocyte Fc receptors. J Exp Med. 1979;150:580–596. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.3.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu F-T, Bohn JW, Ferry EL, Yamamoto H, Molinaro CA, Sherman LA, Klinman NR, Katz DH. Monoclonal dinitrophenyl-specific murine IgE antibody: preparation, isolation, and characterization. J Immunol. 1980;124:2728–2737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oettgen HC, Martin TR, Wynshaw-Boris A, Deng C, Drazen JM, Leder P. Active anaphylaxis in IgEdeficient mice. Nature (Lond) 1994;370:367–370. doi: 10.1038/370367a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai M, Miyamoto M, Tam S-Y, Wang Z-S, Galli SJ. Detection of mouse mast cell–associated protease mRNA: Heparinase treatment greatly improves RT-PCR of tissues containing mast cell heparin. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:335–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin S, Cicala C, Scharenberg AM, Kinet J-P. The FcεRI-β subunit functions as an amplifier of FcεRI-γ mediated cell activation signals. Cell. 1996;85:985–995. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coleman JW, Holliday MR, Kimber I, Zsebo KM, Galli SJ. Regulation of mouse peritoneal mast cell secretory function by stem cell factor, IL-3 or IL-4. J Immunol. 1993;150:556–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finkelman FD, Snapper CM, Mountz JD, Katona IM. Polyclonal activation of the murine immune system by a goat antibody to mouse IgD. IX. Induction of a polyclonal IgE response. J Immunol. 1987;138:2826–2830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeishi T, Martin TR, Katona IM, Finkelman FD, Galli SJ. Differences in the expression of the cardiopulmonary alterations associated with anti-immunoglobulin E–induced or active anaphylaxis in mast cell–deficient and normal mice. Mast cells are not required for the cardiopulmonary changes associated with certain fatal anaphylactic responses. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:598–608. doi: 10.1172/JCI115344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkelman FD, Katona IM, Urban JF, Jr, Holmes J, Ohara J, Tung AS, Sample JVG, Paul WE. IL-4 is required to generate and sustain in vivoIgE responses. J Immunol. 1988;141:2335–2341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kühn R, Rajewsky K, Müller W. Generation and analysis of interleukin-4 deficient mice. Science (Wash DC) 1991;254:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1948049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamaguchi Y, Kanakura Y, Fujita J, Takeda S-I, Nakano T, Tarui S, Honjo T, Kitamura Y. Interleukin 4 as an essential factor for in vitro clonal growth of murine connective tissue–type mast cells. J Exp Med. 1987;165:268–273. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.1.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madden KB, Urban JF, Jr, Ziltener HJ, Schrader JW, Finkelman FD, Katona IM. Antibodies to IL-3 and IL-4 suppress helminth-induced intestinal mastocytosis. J Immunol. 1991;147:1387–1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banks EMS, Coleman JW. A comparative study of peritoneal mast cells from mutant IL-4 deficient and normal mice: evidence that IL-4 is not essential for mast cell development but enhances secretion via control of IgE binding and passive sensitization. Cytokine. 1996;8:190–196. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1996.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terada N, Konno A, Terada Y, Fukuda S, Yamashita T, Abe T, Shimada H, Ishida K, Yoshimura K, Tanaka Y, Ra C, Ishikawa K, Togawa K. IL-4 upregulates FcεRI α-chain messenger RNA in eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96:1161–1169. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plaut M, Pierce JH, Watson CJ, Hanley-Hyde J, Nordan RP, Paul WE. Mast cell lines produce lymphokines in response to cross-linkage of FcεRI or to calcium ionophores. Nature (Lond) 1989;339:64–67. doi: 10.1038/339064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burd PR, Rogers HW, Gordon JR, Martin CA, Jayaraman S, Wilson SD, Dvorak AM, Galli SJ, Dorf ME. Interleukin 3-dependent and -independent mast cells stimulated with IgE and antigen express multiple cytokines. J Exp Med. 1989;170:245–57. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Vries JE, Punnonen J, Cocks BG, Aversa G. The role of T/B cell interactions and cytokines in the regulation of human IgE synthesis. Semin Immunol. 1993;5:431–439. doi: 10.1006/smim.1993.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ownby, D.R. 1993. Clinical significance of IgE. In Allergy. Principles and Practice. Vol. I. Fourth Edition. E. Middleton, Jr., C.E. Reed, E.F. Ellis, N.F. Adkinson, Jr., J.W. Yunginger, and W.W. Busse, editors. Mosby—Year Book, Inc., St. Louis. 1059–1076.

- 40.Sutton BJ, Gould HJ. The human IgE network. Nature (Lond) 1993;366:421–428. doi: 10.1038/366421a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vercelli, D., and R.S. Geha. 1993. Control of IgE synthesis. In Allergy. Principles and Practice. Vol. I. Fourth Edition. E. Middleton, Jr., C.E. Reed, E.F. Ellis, N.F. Adkinson, Jr., J.W. Yunginger, and W.W. Busse, editors. Mosby—Year Book, Inc., St. Louis. 93–104.

- 42.Marsh DG, Neely JD, Breazeale DR, Ghosh B, Freidhoff LR, Schou C, Beaty TH. Genetic basis of IgE responsiveness: relevance to the atopic diseases. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1995;107:25–28. doi: 10.1159/000236920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeLisi C, Siraganian RP. Receptor cross-linking and histamine release: the quantitative dependence of basophil degranulation on the number of receptor doublets. J Immunol. 1979;122:2286–2292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dembo M, Goldstein B, Sobotka AK, Lichtenstein LM. Degranulation of human basophils: quantitative analysis of histamine release and desensitization due to a bivalent penicilloyl hapten. J Immunol. 1979;123:1864–1872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamaguchi, M., C.S. Lantz, H.C. Oettgen, I.M. Katona, T. Fleming, K. Yano, I. Miyajima, J.-P. Kinet, and S.J. Galli. IgE enhances mouse and human mast cell FcεRI expression, which in turn enhances IgE-dependent mast cell mediator release. (abstr.) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. In press.