Abstract

Three lines of transgenic mice have been generated which express human CD25 under the control of the 722-base pair region located immediately 5′ of the precursor (pre)–B cell–specific λ5 gene. All three strains express human CD25 in parallel to endogenous λ5 on pre–B cells, but not on mature B lymphocytes or other blood cell lineages. High expression of human CD25 on B lineage cells of transgenic mice has allowed the identification of a new B220+CD19−λ5+ precursor of the B220+CD19+λ5+ c-kit+ pre-BI cells. Both types of precursors are clonable on stromal cells in the presence of interleukin-7. The CD19− precursors have a sizeable part of their immunoglobulin heavy chain gene loci in germline configuration, while the CD19+ pre–BI cells are predominantly DJH rearranged. The results indicate that random integration of the 722-bp 5′ region of the λ5 gene into the mouse genome confers tissue and differentiation stage–specific expression of a transgene.

Two genes, VpreB and λ5, encode the proteins that together make up the surrogate L chain (1, 2). Both genes are specifically expressed in precursor (pre)1–B cells, but not in immature and mature, surface Ig-positive B cells, nor in any other cell of mouse or human so far tested (for review see reference 3). The pre–B cell–specific control of λ5 gene expression has been analyzed in some detail (4, 5). Deletion analysis of a 722-bp 5′ region upstream of the λ5 gene has defined two parts of the upstream region, Aλ5 and Bλ5 (4). Aλ5, 154 bp directly 5′ of the λ5 gene, functions as a basal promoter in different types of cells. Bλ5, 568 bp 5′ of Aλ5, acts in concert with Aλ5 as a suppressor region in nonpre–B cells, but as an enhancer region on a heterologous promoter in pre–B cells (4, 5).

Differentially regulated gene expression has allowed to define, and separate by FACS®, B lymphocyte lineage subpopulations in mouse bone marrow (BM). Hardy et al. (6) have used the surface antigens heat stable antigen (HSA), BP-1 and leukosialin (CD43) to separate B220 (CD45R)+ pre–B cell populations from immature IgM+ and mature IgM+/IgD+ B cells. An analysis of the expression of VpreB, λ5, RAG-1 and RAG-2, TdT, mb-1 and bcl-2, and particularly the semiquantitation of DJH, VHDJH and VκJκ rearranged Ig genes in populations of these B lineage cells have allowed Li et al. (7) to propose an order of development of the subpopulations. The earliest population, called fraction A, which is CD43+, HSA−, BP-1− has low, if at all detectable, expression of VpreB, λ5, RAG-1 and RAG-2, TdT, and mb-1 and has low quantities of DJH rearranged IgH chain genes while VH(J558)DJH and VκJκ rearranged Ig genes remained below detection limits.

Rolink et al. ordered B220+ B lineage subpopulations in mouse BM by the analysis of the expression of c-kit, CD25, and surrogate L chain (8) and by a single cell PCR analysis of the IgH and L chain loci (9). Rolink et al. (10) then used the differential expression of B220+ and CD19 to define a B220+ CD19− cell population in BM, which could further be subdivided into three subpopulations, a NK1.1+ precursor population of NK cells, a CD4+ population of unknown function, and a marker-negative population. These cell populations are probably largely identical with Hardy's fraction A, since they were found to be CD43+, HSAlow, BP-1−. The marker negative CD19− B220+ cells were suspected to contain some early B lineage progenitors, since stromal cell/IL-7–reactive cells could be found in low frequencies (10).

In this paper we describe the generation of nine transgenic mouse lines in which the gene for the α chain of the human IL-2 receptor (human CD25; hu-CD25) is under the control of the 722-bp 5′ region of the λ5 gene (5′λ5). In three of the lines the 5′λ5 confers lineage and differentiation stage specific–expression of the hu-CD25 transgene in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Construction of the Transgene Vector, 5′λ5–hu-CD25 and Production of Transgenic Mice.

5′λ5 (4) was made by PCR (PCR 1) using the following primers: 5′ primer: 5′ ACGTCGACTTATATGTCACAGGCTGGCCTTGA 3′, 3′ primer: 5′ CATCAGCAGGTATGAATCCATTGACCCTCAAGTCCAAAGTC 3′. The hu-CD25 cDNA was made by PCR (PCR 2) using the following primers: 5′ primer: 5′ CTTGAGGGTCAATGGATTCATACCTGCTGATG 3′, 3′ primer: 5′ ACGGATCCCTAGATTGTTCTTCTACTCTTCCT 3′. The 5′λ5 3′ primer and the hu-CD25 5′ primer contain overlapping sequences (underlined) to facilitate the third PCR. This (PCR 3) was made by using the 5′λ5 5′ primer together with the hu-CD25 3′ primer and as template use a 1:1 mixture of PCR 1 and PCR 2. The 5′λ5 5′ primer contained a SalI site and the hu-CD25 3′ primer contained a BamHI site and some extra bases for protection of the respective restriction site. The PCR product (PCR 3) was cloned into the vector pSPex23pA as a SalI/BamHI fragment. The pSPex23pA vector contains human β-globin exon 2, intron 2, exon 3, and polyA site (1.6-kb SalI/PstI fragment) from the vector pHSE3′ (11) inserted into pSP73 (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) lacking a BamHI site. The final 5′λ5–hu-CD25 vector contained in 5′ to 3′ order the following: 5′λ5 as promoter/enhancer, human CD25 cDNA, human β-globin exon 2, intron 2, exon 3, and polyA site. This 3.2-kb SalI/XhoI fragment was purified and used for injections.

The purified 3.2-kb SalI/XhoI fragment was microinjected into (C57Bl/6 × DBA/2)F2 zygotes as described (12). Transgenic lines were maintained in pathogen-free conditions and backcrossed for three generations to C57Bl/6 mice. All experiments were done with transgenic hemizygotes and their wild-type littermates between 4 and 8 wk of age. For the determination of transgene copy numbers DNA isolated from tails was analyzed by slot and Southern blot using the hu-CD25 cDNA and β-actin as probes.

Antibodies, Flow Cytometric Analysis, and Cell Sorting.

The rat mAb ACK-4 (anti–mouse c-kit; provided by Dr. S. Nishikawa, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan; reference 13) the rat anti–mouse IgD mAb NIM-R9; (provided by Dr. R. Parkhouse; reference 14) and the rat anti–mouse CD19 mAb 1D3 (10) were conjugated with biotin using standard procedures. The following rat mAbs were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA) PE- and allophycocyanin-conjugated RA-6B2 (CD45R, B220), biotinylated 7D4 (anti–mouse CD25, TAC), PE-conjugated RM4-5 (anti– mouse CD4), PE-conjugated PK186 (anti–mouse NK1.1), and FITC- and PE-conjugated M-A251 (anti–human CD25). FITCconjugated goat anti–mouse IgM (μ chain specific) was obtained from Southern Biotechnology Associates (Birmingham, AL).

Single cell suspensions from BM were prepared by flushing out cells from femurs with either ice-cold staining buffer (PBS containing 2% FCS and 0.1% NaN3) or tissue culture medium (IMDM, 2% FCS). Cells were incubated with a combination of FITC-, PE-, biotin- or allophycocyanin-conjugated antibodies in staining buffer, washed with staining buffer, incubated for 15 min with PE-streptavidin (Southern Biotechnology Associates) to reveal the biotin reagent, and finally washed with staining buffer. Cells were analyzed on a FACScan® instrument (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). In double staining experiments propidium iodide was included in the staining buffer (1 μg/ml) to gate out dead cells. Cells present in the extended lymphocyte gate (low side scatter) were gated. Cell sorting was performed on a FACStar Plus® instrument. For the sorting of rare populations such as the B220+CD19− fractions in BM, a two step sorting protocol was used to obtain maximum purity. During the first sorting, the instrument was set on enrichment mode. The purity after the first round was generally >85%. After the second sorting of the enriched cells, the purity was generally >96% when reanalyzed with the instrument settings used for the sort.

Pre–B Cell Culture System.

Pre-B cell lines were established from fetal livers of individual day 17 embryos from pregnant transgenic mice. The pre-B cell lines and clones were cultivated as described (15). In brief, pre–B cells were cultured on a semiconfluent layer of γ-irradiated (30 Gy) ST-2 stromal cells (16) in IMDM containing 100 μg/ml kanamycin, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% heat-inactivated FCS (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and 100 U/ml IL-7. Culture supernatant of J558L cells transfected with the murine IL-7 cDNA in the BMG neo vector was used as a source of IL-7 (17). When stable pre–B cell lines were established, the cells were transduced with a retrovirus containing the mouse bcl-2 gene (a gift from Dr. M. Busslinger, Research Institute of Molecular Pathology, Vienna, Austria) and transduced cells were selected with 3 μg/ml puromycin on puromycin-resistant ST-2 cells. For the induction of differentiation of bcl-2 transfected pre–B cells, cells were harvested, washed three times in medium without IL-7, and cultured on a semi-confluent layer of γ-irradiated ST-2 stromal cells in medium without IL-7.

Limiting Dilution Analysis of Pre–B Cells Growth.

Cell suspensions from FACS® sorted cells were diluted by serial twofold dilutions in medium with IL-7 and were plated on a semi-confluent layer of γ-irradiated (30 Gy) ST-2 cells in 96-well flat-bottom plates. Cultures were scored on day 7 for pre–B cell colonies containing >50 cells, using an inverted microscope. On several occasions, the contents of individual wells with lymphoid colonies were removed and analyzed for B220 and CD19 expression by FACS®. In all cases, the cells uniformly expressed B220 and CD19.

Northern Blot Analysis.

Total cellular RNA was prepared using RNAzol B (Biotecx Laboratories, Inc., Houston, TX) according to the manufacturer's recommendations and analyzed as described (18). The complete cDNA of the hu-CD25 was used as a probe for the detection of hu-CD25 RNA.

Reverse Transcription–PCR.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was done exactly as described (19). The following primer-pairs were used: hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT): 5′ GCTGGTGAAAAG GACCTCT 3′, 5′ CACAGGACTAGAACACCTGC 3′; λ5: 5′ GAGATCTAGACTGCAAGTGAGGCTAGAG 3′, 5′ CTTGGGCTGACCTAGGATTG 3′; hu-CD25/β-globin: 5 AGACCAGTCAGTTTCCAGGTGAA 3′, 5′ AAGCGAGCTTAGTGATACTTGTG 3′. All PCRs were carried out with 1 cycle 94°C for 40 s, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 55°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 60 s. The probes specific for the HPRT, λ5, and hu-CD25 genes were generated by cloning PCR fragments into pBluescript and were used for PCR–Southern blot analysis.

PCR Analysis of IgH Gene Rearrangements.

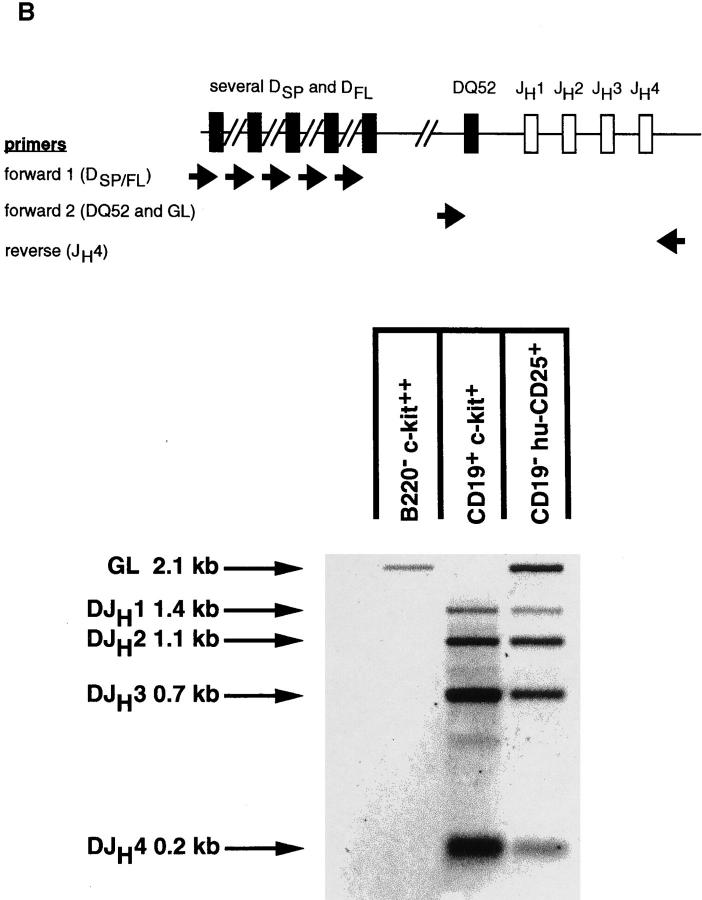

DJH rearrangements of the H chain locus were amplified and detected using PCR as outlined in Fig. 4. Two forward primers binding immediately upstream of DFL/DSP elements or the DQ52 element, respectively, were used in a mixture (DFS and DQ52 as described in reference 20) together with one reverse primer binding downstream of JH4 (JH4A in reference 16). In germline configuration, the DQ52 and JH4A primers will amplify the 2.15-kb germline fragment. DJH1, DJH2, DJH3, and DJH4 rearrangements involving either DFL, DSP, or DQ52 elements will be detected by the emergence of bands of 1.46, 1.15, 0.73, and 0.20 kb, respectively.

Figure 4.

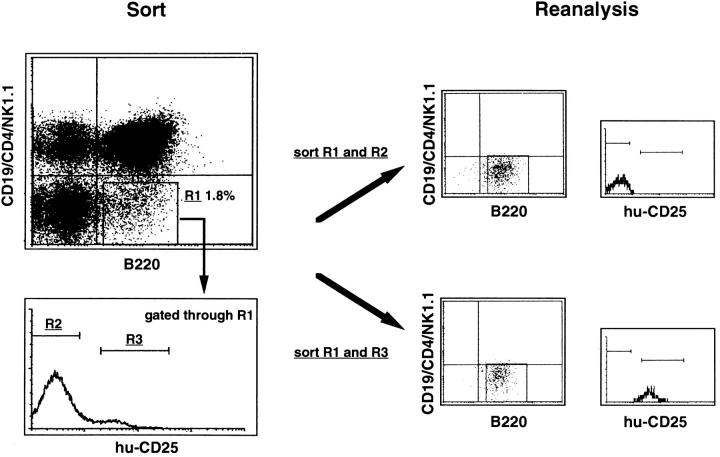

FACS® sorting procedure and reanalyzed data of transgenic BM cells analyzed for expression of B220, CD19, CD4, NK1.1, and hu-CD25. BM cells depleted of IgM+ cells (see Materials and Methods) were stained with anti–B220-APC, anti–CD19PE, anti–CD4-PE, anti–NK1.1PE, and anti–hu-CD25–FITC. B220+CD19−CD4−NK1.1− cells (gate R1) were gated and analyzed for hu-CD25 expression. Hu-CD25 positive (gate R3) and negative cells (gate R2) among the B220+CD19− CD4−NK1.1− population were sorted separately and the obtained fractions were reanalyzed after sorting.

Cells were sorted directly into 100 μl PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20 and proteinase K (0.2 mg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, FRG) and incubated at 55°C for 2 h. The preparations were boiled and DNA was precipitated in ethanol with glycogen as the carrier. The DNA pellet was dissolved in Tris-HCl, pH 8.3. The DNA equivalent of 50 sorted cells was subsequently used for PCR amplification. The amplification protocol was 35 cycles of 20 s at 94°C, 30 s at 65°C, and 2 min at 72°C. An oligonucleotide specific for the JH4 region (5′ AGGAACCTCAGTCACCGTC 3′) was used for PCR–Southern blot analysis.

Results

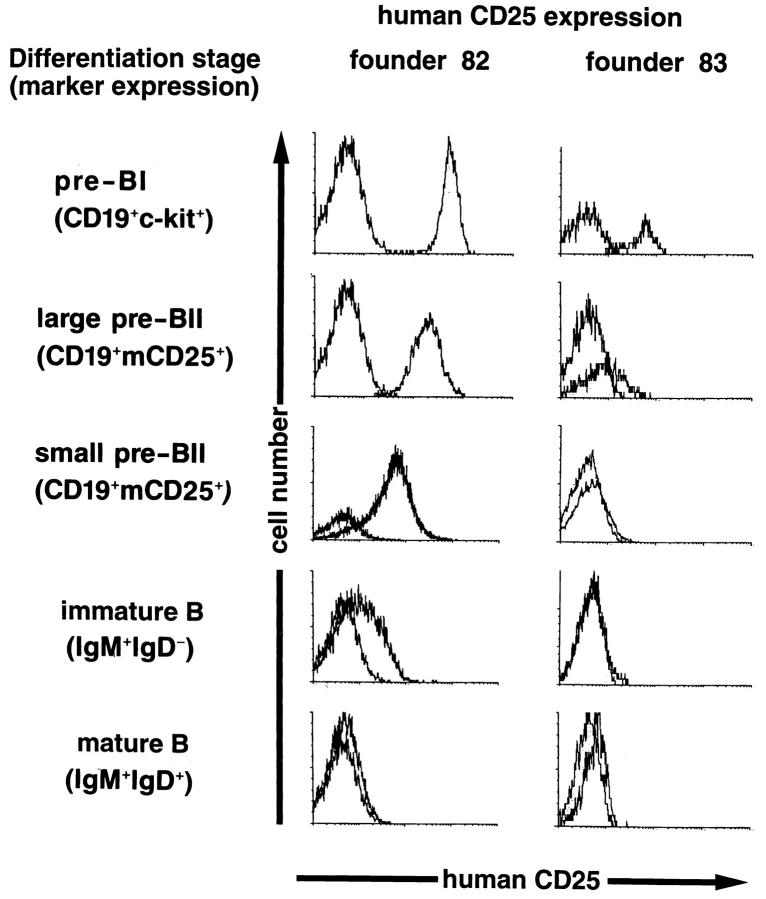

The 722-bp region of the λ5 upstream regulatory region (4) was inserted upstream of the hu-CD25 cDNA (21) and introduced as a transgene into the germline of mice. Cells from BM and spleen of nine founder strains carrying the transgene were analyzed by FACS® for hu-CD25 expression. Three of the nine strains were found to express surface hu-CD25. As determined by Southern and slot blot analyses (Table 1), transgene copy numbers varied between 10 and 30 in expressing and between 4 and 400 in nonexpressing strains. This indicates that expression of hu-CD25 was most likely influenced by integration sites.

Table 1.

Summary of Transgenic Founder Lines

| TG strain No. | Copy numbers | hu-CD25 expression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | 4 | − | ||

| 15 | 12 | − | ||

| 50 | 12 | − | ||

| 83 | 12 | + | ||

| 73 | 24 | + | ||

| 82 | 24 | + | ||

| 52 | 24 | − | ||

| 35 | 100 | − | ||

| 57 | 400 | − |

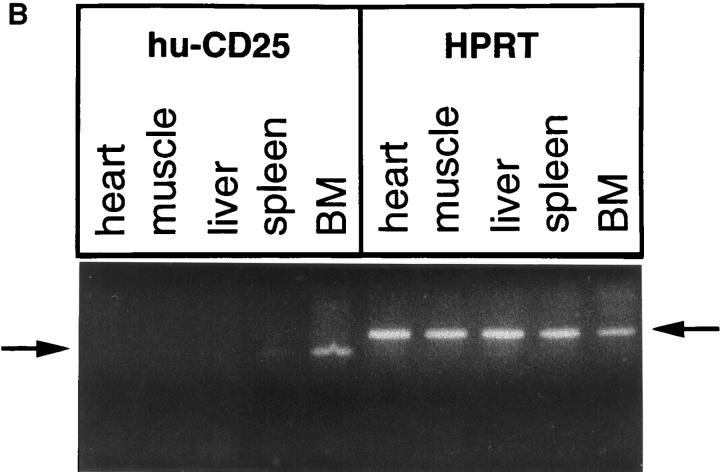

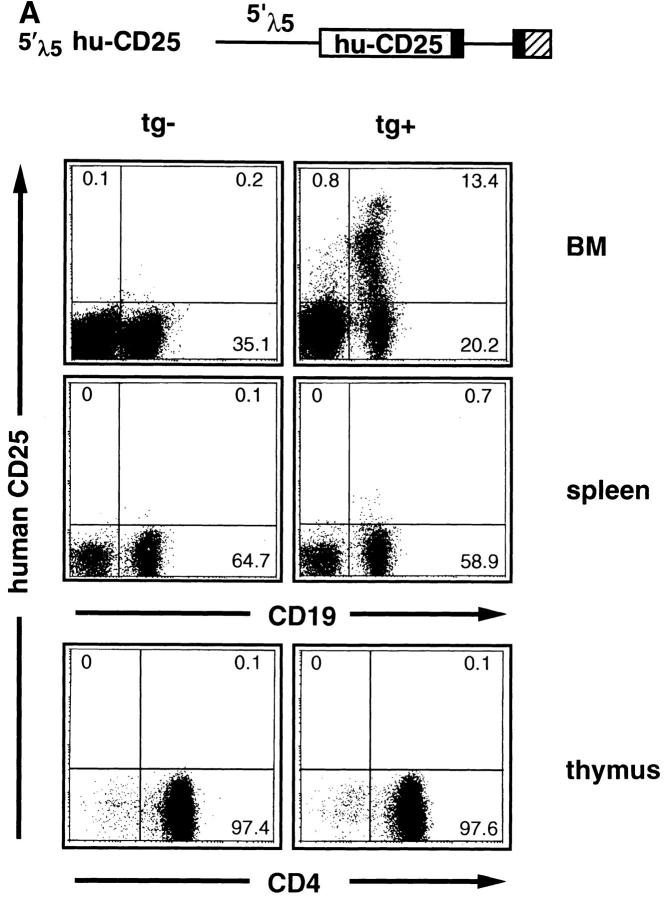

The analysis of the cellularity as well as the staining of the different B cell differentiation stages in BM and spleen (as described in detail previously in reference 15) revealed that in none of the transgenic lines was lymphocyte development disturbed by any means (Table 2) in agreement with other studies using hu-CD25 as transgene (22). All three founder strains expressing the transgene showed similar staining patterns in BM (as shown in Fig. 1 A for the founder 82). Several levels (high, intermediate, and low) of hu-CD25 expression were detected in B lineage cells in the BM, while spleen and thymus cells were practically negative (Fig. 1 A). The ∼0.5% of spleen cells which expressed very low levels of hu-CD25 were found to be IgM+IgD− immature B cells (data not shown). Most hu-CD25 positive BM cells expressed the B cell markers CD19 and CD45R (B220; Fig. 1 A, and data not shown). RT-PCR analysis of BM, spleen, liver, muscle, and heart readily detected huCD25 RNA in the BM and low levels in the spleen but no signal was found in the nonlymphoid samples, while the HPRT control primers detected HPRT RNA in all organs (Fig. 1 B). Thus, the 5′λ5 control region contains lineage– and differentiation stage–specific promoter/enhancer activity.

Table 2.

Phenotypic Characterization of BM Cells in 5′λ5 hu-CD25 Transgenic Mice and Normal Littermates

| Phenotypic markers | tg+ | tg− | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (percentage of nucleated BM cells) | ||||

| B220+CD19− | 3.6 | 4.0 | ||

| CD19+ c-kit+ | 3.4 | 3.3 | ||

| CD19+ mCD25+ large | 5.2 | 4.9 | ||

| CD19+ mCD25+ small | 20.7 | 22.3 | ||

| IgM+IgD− | 10.9 | 9.7 | ||

| IgM+IgD+ | 6.1 | 5.3 | ||

The data are average values of three 6-wk-old mice each. BM cellularity was normal in all mice (1.2–1.5 × 107 cells/femur).

Figure 1.

5′λ5 is active in BM but not in spleen, thymus, heart, muscle, or liver. 5′λ5 hu-CD25: 5′λ5 inserted upstream of the cDNA encoding human IL-2–R (hu-CD25; reference 21) followed by exon 2, intron 2, exon 3 (solid boxes), and polyA site (hatched box) from human β-globin (11). The 5′λ5 hu-CD25 was used to establish transgenic mice. (A) BM, spleen, and thymus cells were analyzed by FACS® using antibodies detecting mouse CD19 or CD4 and hu-CD25. Data from nontransgenic (tg−) and transgenic (tg+) littermates from founder 82 are shown. (B) Total RNA from heart, muscle, liver, spleen, and BM was isolated and analyzed for expression of hu-CD25 and HPRT by RT-PCR analysis. Arrows denote the 185 and 220-bp fragments of hu-CD25 or HPRT, respectively.

Three-color FACS® analysis of BM cells was performed in order to define the stages at which the transgene was expressed and to analyze if this correlated with expression of the endogenous λ5 gene. Fig. 2 shows the analyses of the expressor strains 82 and 83 in which cells expressing CD19 and a second marker were gated and the levels of hu-CD25 analyzed. Strain 73 showed virtually identical expression levels of transgenic hu-CD25 to strain 82 (data not shown). Strain 83 displayed ∼5–10-fold lower levels when compared with the other two strains. While strains 82 and 73 both contained about 30 transgene copies, strain 83 contained about 10 copies. In BM cells from line 82 and 73, high levels of hu-CD25 were found on c-kit+ pre–BI cells, intermediate levels were found on mouse CD25+ large pre– BII cells, low expression on mouse CD25+ small pre–BII cells, while very little or no expression was detected on immature (IgM+IgD−) and mature (IgM+IgD+) B lymphocytes. Expression of hu-CD25 protein correlated with transgenic RNA steady state levels were determined by RT-PCR analysis; high levels of transgenic RNA were detected in pre–BI cells, intermediate and low levels in large and small pre–BII cells, respectively, and very little or no transgenic RNA was detected in immature and mature B cells (not shown). Parallel analysis of endogenous λ5 gene transcript levels demonstrated that λ5 was expressed in a similar fashion, in agreement with previous analyses (19), with the exception that slightly lower relative amounts were detected in the later differentiation stages as compared to transgenic hu-CD25 RNA. Thus, in general, the expression of huCD25 protein and RNA correlated with that of endogenous λ5. Both the endogenous λ5 gene and the 5′λ5-controlled transgene generate transcripts which are expressed in pre–BI cells and begin to be downregulated as these cells differentiate into pre–BII cells.

Figure 2.

Expression of the transgene correlates with the stage of differentiation of B lineage cells in the BM. Three-color FACS® analysis of BM cells from founder 82 and 83. Cells were gated for CD19+ lymphocytes coexpressing the markers c-kit for pre–BI cells, murine CD25 for pre–BII cells (further subdivided into large and small pre–BII cells according to forward scatter characteristics), and IgM and IgD for immature and mature B cells. The level of hu-CD25 was then determined on gated cells.

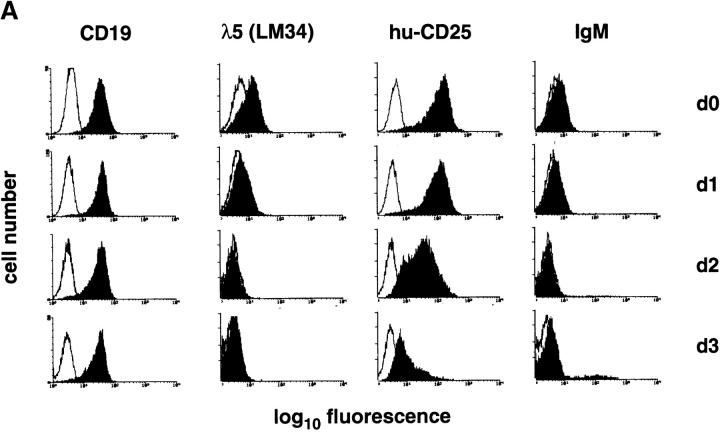

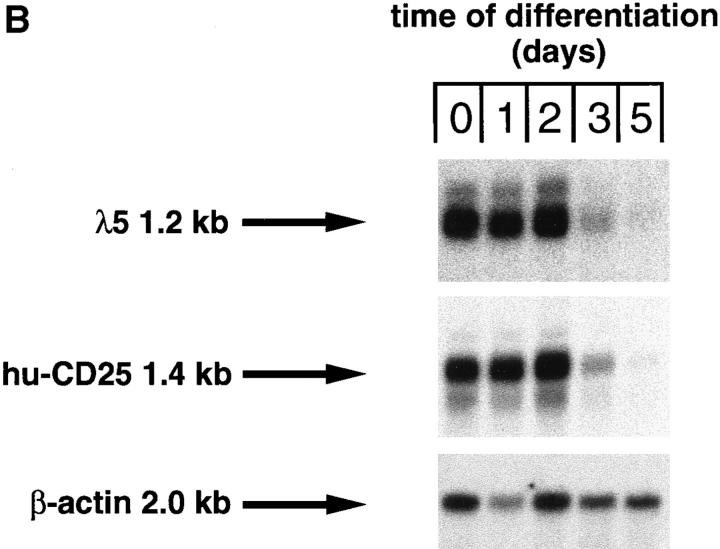

The developmental control of transgenic hu-CD25 expression in B lymphocyte development was further analyzed in differentiating pre–B cells in vitro. c-kit+ pre–BI cells can be expanded in vitro on stromal cells in the presence of IL-7 (15). Therefore, c-kit+ pre–BI cells from fetal liver of transgenic mice were cultured on ST-2 stromal cells in the presence of IL-7 and transduced with a retrovirus encoding the bcl-2 cDNA to inhibit apoptosis after removal of IL-7. As shown in Fig. 3 A, the cells in culture expressed CD19, λ5 protein (as detected by the LM34 antibody; reference 23) and high levels of hu-CD25, but no detectable IgM on the cell surface. Withdrawal of IL-7 and analysis 1, 2, and 3 d thereafter demonstrated that the level of CD19 expression remained constant while the surface expression of λ5 and hu-CD25 decreased with time. In addition, ∼10% of the cells started to express IgM on the cell surface at day 3 of differentiation. Furthermore, Northern blot analysis of these differentiating cells showed that the RNA steady state levels of hu-CD25 and λ5 decreased with time of differentiation (Fig. 3 B). Disappearance of hu-CD25 paralleled the disappearance of λ5 RNA (Fig. 3 B). Again, these results indicate that the hu-CD25 transgene, like endogenous λ5, is expressed in pre–BI cells. Expression of the endogenous λ5 and hu-CD25 transgene is downregulated as these pre–BI cells differentiate in vitro to sIgM+ immature B cells.

Figure 3.

Downregulation of transgene expression upon differentiation of in vitro cultivated pre–B cell lines. Pre–B cell lines were cultivated in the presence of IL-7 on ST-2 stromal cells as described (15), and differentiation was induced by withdrawal of IL-7. (A) After 0, 1, 2, and 3 d in the absence of IL-7, the cells were stained with antibodies specific for CD19, λ5 (as detected by the mAb LM34; reference 23), hu-CD25, and IgM, and analyzed by FACS®. Fluorescence intensities are displayed (solid histograms) and the fluorescence intensity of an irrelevant antibody is overlaid (open histograms). (B) After 0, 1, 2, 3, and 5 d in the absence of IL-7, the cells were harvested and RNA was prepared and subjected to Northern blot analysis using λ5, hu-CD25, and β-actin specific probes.

Analysis of BM cells for hu-CD25 expression detected a population of cells which did not express the B lineage marker CD19, but did express intermediate levels of huCD25 (Figs. 1 and 4). This population was found to be B220 positive (Fig. 4), and therefore, belongs to the mixture of B220+CD19− BM cells recently analyzed to be composed of NK1.1+ precursors to NK, CD4+, and markernegative cells (10). B cell precursor activity was found only in the marker-negative subpopulation. This marker-negative subpopulation amounts to approximately one-third of all B220+CD19− cells, i.e., 1–2% of all BM nucleated cells (10). In the 5′λ5–hu-CD25 transgenic mice the B220+ CD19− hu-CD25+ cells did not express NK1.1, or CD4 (Fig. 4), and are therefore found within the marker-negative subpopulation. This marker-negative hu-CD25+ subpopulation comprises 10–15% of all B220+CD19−NK1.1− CD4− cells (Fig. 4), i.e., 0.1–0.3% of all BM cells.

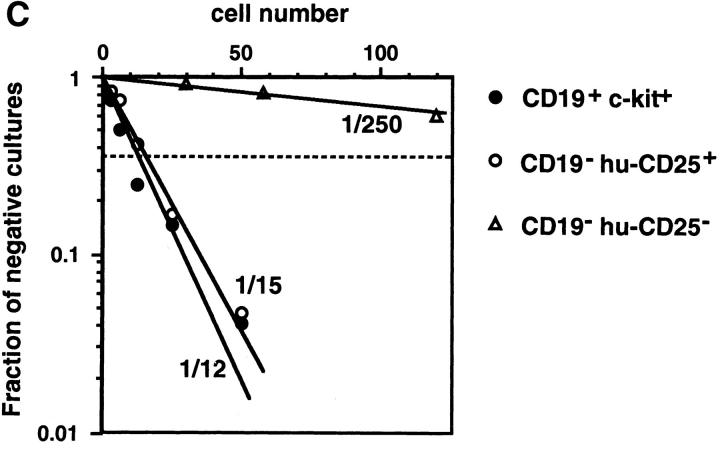

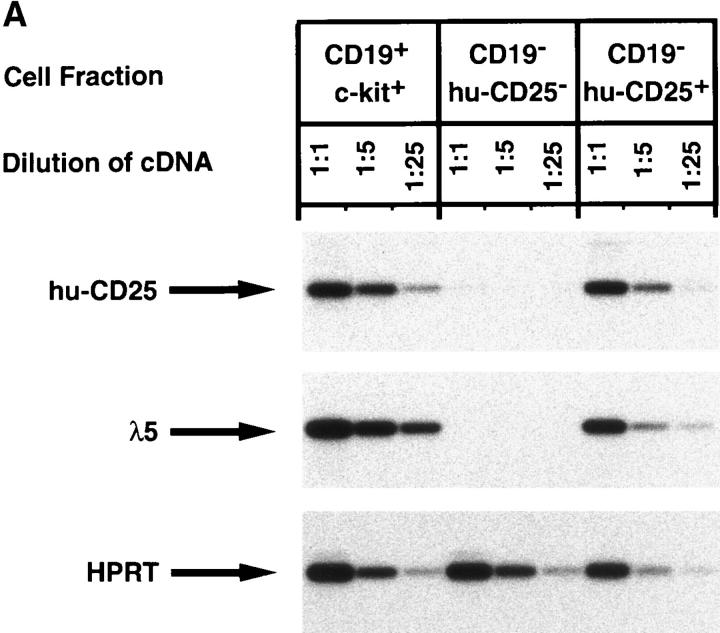

The marker-negative subpopulation was sorted into huCD25+ and hu-CD25− cells and analyzed for other markers, in particular for the expression of endogenous λ5. RTPCR analysis shown in Fig. 5 A revealed that these cells, like CD19+ pre–BI cells coexpressed hu-CD25 and endogenous λ5, whereas hu-CD25− sorted cells from the same B220+CD19− population contained no detectable λ5 or hu-CD25 message. The B220+CD19+ hu-CD25+ cells also expressed VpreB, sterile μ H chain, RAG-1, RAG-2, and B29 transcripts (data not shown). PCR analysis of the H chain gene loci of the B220+CD19− hu-CD25+ cells revealed that a sizeable fraction of all loci were still in germline configuration while the rest of these loci were DJH rearranged (Fig. 5 B, lane 3). VHDJH rearranged loci could not be detected (data not shown). In CD19+ c-kit+ pre–BI cells (lane 2) the H chain gene loci were found to be mostly DJH rearranged in agreement with previous analyses (9).

Figure 5.

Characterization of the B220+CD19− negative cell population in BM of mice expressing the hu-CD25 transgene under the control of the 5′λ5. (A) Expression of hu-CD25, endogenous λ5, and HPRT in sorted cell populations. BM cells were sorted by FACS® after triple labeling for B220, CD19, and hu-CD25, or double labeling for CD19 and c-kit, respectively. Fivefold dilutions of cDNA from sorted cells were subjected to PCR amplification of hu-CD25, λ5, and HPRT genes and PCR products detected by Southern blotting with specific probes. (B) PCR-mediated analysis of the rearrangement status of the IgH locus in sorted cell populations. DNA of sorted cells was subjected to PCR amplification as outlined in the top of the figure. After electrophoresis and Southern blotting, the PCR products were detected by hybridization with a JH4-specific oligonucleotide. Sorted cell populations are in lane 1, B220− c-kithigh; lane 2, CD19+ c-kit+, and lane 3, B220+CD19− hu-CD25+. (C) Limiting dilution analysis of FACS® sorted B220+ cells from BM on ST-2 stromal cells in the presence of IL-7. Growth of pre–B cell colonies consisting of >50 cells was scored on day 7 of culture. 24 replicate cultures for each cell number were initiated. According to Poisson distribution, one precursor is present in the cell suspension when 37% of the cultures do not show colonies.

We conclude from these analyses that the B220+CD19− NK1.1−CD4− hu-CD25+ cells contain early B lineage precursors. Since they have a considerable fraction of their H chain loci in germline configuration they might be precursors of the CD19+ pre–BI cells. The B220+CD19− huCD25− λ5− BM cells might not belong to the B lineage. These conclusions were further supported by an analysis of the proliferation and differentiation potential of these early B220+CD19− cell populations. Limiting dilution analyses on stromal cells in the presence of IL-7 (15) showed that the CD19+ hu-CD25high pre–BI cells (1 in 12) as well as the B220+CD19− hu-CD25+ B lineage precursors (1 in 15) contained a similarly high frequency of clonable cells (Fig. 5 C). This frequency of clonable cells in the B220+ CD19−NK1.1−CD4− hu-CD25+ cell population is, therefore, ∼10-fold higher than the frequency found previously by Rolink et al. (10) in the total B220+CD19−NK1.1− CD4− population. We therefore conclude that the huCD25 reporter transgene is preferentially expressed in early clonable B lineage precursors before the expression of CD19.

It should be noted that in comparison to the pre–BI– derived colonies, the B220+CD19− hu-CD25+–derived colonies were larger in size and contained more cells. After 7 d in tissue culture, the CD19− hu-CD25+ precursors became CD19 positive and the cells could be induced to differentiate to IgM+ immature B cells upon removal of IL-7 from the cultures (data not shown). The B220+CD19− hu-CD25− cells showed 20–30-fold lower frequency of clonable lymphoid cells in the above mentioned culture system (Fig. 5 C).

Collectively, these results show that the high expression of the transgenic hu-CD25 on the surface of BM cells has allowed the isolation and characterization of an early B lineage cell population that is likely to be precursors of pre–BI cells.

Discussion

The three transgenic strains of mice presented here carry the cDNA of the α chain of the human IL-2 receptor (CD25) under the control of the 722-bp 5′ regulatory region of the λ5 gene. The 5′λ5 regulatory region, consisting of Aλ5 and Bλ5, conveys lineage and differentiation stage specificity to the expression of the transgenic reporter gene, hu-CD25. This expression pattern in vivo confirms and extends previous results from the analysis of various cell lines representing different stages of B cell development (4, 5). In the previous experiments, however, a heterologous enhancer was used in the reporter gene constructs in addition to the 5′λ5 regulatory region to obtain measurable levels of reporter gene expression. We show here that the short stretch of the 722-bp 5′ regulatory region contains the essential cis-acting regulatory elements for lineage and differentiation stage specific expression. Our experiments do not provide any evidence for the need of additional enhancer elements for this specific expression. It will now be possible to study the function of the 5′λ5 regulatory region in greater detail.

It appears that the copy number of transgenes inserted into the mouse genome is not important for the specificity of expression. Furthermore, insertion of the transgene at different sites in the genome only determines the level, and not the specificity, of expression. These results indicate that it will be possible to express other transgenes in a pre–B cell–specific fashion without inserting them at the λ5 locus by homologous recombination.

Lineage- and tissue-specific expression conferred by a short 5′ region has also been reported for other genes. Among the earliest genes analyzed in this context was the rat insulin gene in which the 700-bp 5′ region was shown to drive the expression of the simian virus 40 large T antigen in β cells of the pancreas, and the transgenic mice developed β cell tumors (24). The insulin 5′ region has subsequently been used to direct β cell–specific expression of many genes. The insulin enhancer within these 700 bp, in the context of its own promoter, confers gene expression only in β cells, while in the presence of a heterologous promoter, the same enhancer is not as restricted and allows expression in the brain also (25). Another example is the 620-bp proximal promoter of the lck gene. It was shown to allow expression in thymocytes, but not in peripheral T cells, in agreement with lck proximal promoter driven transcription in T cell development (26), though the defined differentiation stages in the thymus were not analyzed.

Perhaps the most widely used system expressing a transgene within the lymphoid system takes advantage of the well characterized IgH intron enhancer (Eμ) (27–29), either in combination with an Ig promoter or with a heterologous promoter. Such combinations allow expression not only in B, but also in T lymphocytes. Since Eμ seems to overrule the specificity of even a locus control region (30), it appears not suited for transgene expression if a more narrow window of expression is preferred.

In general, expression of the hu-CD25 transgene paralleled that of the endogenous λ5 gene. In c-kit+ pre–BI cells and in large pre–BII cells, λ5 and transgene expression was highest. In these differentiation stages, using currently available reagents, λ5 protein is detectable either in the cytoplasm (8) or on the cell surface (31). Small differences can be seen in the small pre–BII/immature B cell compartments. The data shown in Fig. 2 indicate that the huCD25 is expressed as protein in small pre–BII cells, and at even lower levels in immature B cells in two of the three founder lines. Endogenous λ5 protein was not detectable at the later differentiation stages and λ5 mRNA was reduced about 20–30-fold when compared to pre–BI cells (reference 19 and unpublished observation). The hu-CD25 transgene contains human β-globin sequences which might prolong mRNA half-life as compared to endogenous λ5 and, hence, protein synthesis. In addition, hu-CD25 protein might be more resistant than λ5 to degradation which again could contribute to prolonged expression of hu-CD25 in differentiating B lineage cells in BM.

The easily detectable expression of the transgenic huCD25 protein on the surface of cells has permitted the identification of a CD19−B220+ hu-CD25+ cell population in the BM that are NK1.1− and CD4−. These novel cells were also found to express endogenous λ5, and as a population, to contain cells that have started to rearrange their IgH gene loci. A high proportion of these CD19− B220+ hu-CD25+ cells are clonable on stromal cells in the presence of IL-7. In fact, the frequency of clonable cells is as high as in the CD19+B220+ hu-CD25high c-kit+ pre–BI cell population. Given that the plating efficiency in these cultures is not 100% (32), the actual frequencies may be even higher. At present it can not be completely ruled out, however, that the CD19−B220+ hu-CD25+ cell population, which represents about 5% of all CD19−B220+ in the BM of transgenic mice, is nevertheless heterogeneous. The finding that the CD19− hu-CD25+ population contains much more of the IgH loci in germline configuration argues that the CD19− hu-CD25+ cells are the precursors of the CD19+ pre–BI cells. Our results agree with previous analyses of the configuration of IgH and L chain loci undertaken by Li et al. (7) for Hardy's fraction A of mouse BM, and suggest that the DJH rearranged IgH chain loci found by these authors are contributed by B220+CD19− NK1.1−CD4− cells, now further marked by the hu-CD25 reporter transgene.

To date, it is clear that cells expressing CD19 are committed to the B cell lineage. However, stages of hemopoiesis before B cell commitment are poorly understood. The hu-CD25 transgenic mice described in this paper may help to further characterize these early stages of B lineage development and commitment. In addition, they may help further in elucidating the early arrests in B cell development observed in mutant mice defective for, e.g., E2A (33, 34) or EBF (35).

Acknowledgments

We thank U. Müller and A. Werner for excellent technical assistance, M. Dessing for skillful cell sorting, and Drs. A. Rolink, R. Ceredig, K. Karjalainen, and H.-R. Rodewald for discussions and critically reading our manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the Swedish Medical Research Council, the Medical Faculty Lund, the Kungliga Fysiografiska Society, the Österlunds, the Kocks, the Crafoords, and the G. Danielssons Foundations (I.-L. Mårtensson). The Basel Institute for Immunology was founded and is supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. (Basel, Switzerland).

Footnotes

1 Abbreviations used in this paper: BM, bone marrow; HPRT, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase; HSA, heat stable antigen; hu-CD25, human CD25; pre, precursor; RT, reverse transcription.

References

- 1.Sakaguchi N, Melchers F. Lambda 5, a new light-chain–related locus selectively expressed in pre-B lymphocytes. Nature (Lond) 1986;324:579–582. doi: 10.1038/324579a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kudo A, Melchers F. A second gene, VpreB in the lambda 5 locus of the mouse, which appears to be selectively expressed in pre–B lymphocytes. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1987;6:2267–2272. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02500.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melchers F, Karasuyama H, Haasner D, Bauer S, Kudo A, Sakaguchi N, Jameson B, Rolink A. The surrogate light chain in B-cell development. Immunol Today. 1993;14:60–68. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90060-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martensson I-L, Melchers F. Pre-B cell specific λ5 gene expression due to suppression in non pre–B cells. Int Immunol. 1994;6:863–872. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.6.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Glozak MA, Blomberg BB. Identification and localization of a developmentally stage-specific promoter activity from the murine lambda 5 gene. J Immunol. 1995;155:2498–2514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardy RR, Carmack CE, Shinton SA, Kemp JD, Hayakawa K. Resolution and characterization of proB and pre–pro-B cell stages in normal mouse bone marrow. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1213–1225. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li YS, Hayakawa K, Hardy RR. The regulated expression of B lineage associated genes during B cell differentiation in bone marrow and fetal liver. J Exp Med. 1993;178:951–960. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolink A, Grawunder U, Winkler TH, Karasuyama H, Melchers F. IL-2 receptor α chain (CD25, TAC) expression defines a crucial stage in pre–B cell development. Int Immunol. 1994;6:1257–1264. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.8.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ten Boekel E, Melchers F, Rolink A. The status of Ig loci rearrangements in single cells from different stages of B cell development. Int Immunol. 1995;7:1013–1019. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.6.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rolink A, ten Boekel E, Melchers F, Fearon DT, Krop I, Andersson J. A subpopulation of B220+cells in murine bone marrow does not express CD19 and contains natural killer cell progenitors. J Exp Med. 1996;183:187–194. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pircher H, Mak TW, Lang R, Ballhausen W, Rüedi E, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM, Bürki K. T cell tolerance to Mlsa encoded antigens in T cell receptor Vβ8.1 chain transgenic mice. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1989;8:719–727. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucchini D, Reynaud CA, Ripoche MA, Grimal H, Jami J, Weill JC. Rearrangement of a chicken immunoglobulin gene occurs in the lymphoid lineage of transgenic mice. Nature (Lond) 1987;326:409–411. doi: 10.1038/326409a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa M, Matsuzaki Y, Nishikawa S, Hayashi SI, Kunisada T, Sudo T, Kina T, Nakauchi H, Nishikawa SI. Expression and function of c-kit in hemopoietic precursor cells. J Exp Med. 1991;174:63–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parkhouse RME, Preece G, Sutton R, Cordell JL, Mason DY. Relative expression of surface IgM, IgD and the Ig-associating α (mb-1) and β (B-29) polypeptide chains. Immunology. 1992;76:535–540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rolink A, Kudo A, Karasuyama H, Kikuchi Y, Melchers F. Long-term proliferating early pre B cell lines and clones with the potential to develop to surface Ig-positive, mitogen reactive B cells in vitro and in vivo. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1991;10:327–336. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogawa M, Nishikawa S, Ikuta K, Yamamura F, Naito M, Takahashi K, Nishikawa SI. B cell ontogeny in murine embryo studied by a culture system with the monolayer of a stromal cell clone, ST-2: B cell progenitor develops first in the embryonal body rather than in the yolk sac. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1988;7:1337–1343. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02949.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karasuyama H, Melchers F. Establishment of mouse cell lines which constitutively secrete large quantities of interleukin 2, 3, 4 or 5, using a modified cDNA expression vectors. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:97–104. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grawunder U, Melchers F, Rolink A. Interferon-γ arrests proliferation and causes apoptosis in stromal cell/interleukin-7–dependent normal murine pre–B cell lines and clones in vitro, but does not induce differentiation to surface immunoglobulin-positive B cells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:544–551. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grawunder U, Leu TMJ, Schatz DG, Werner A, Rolink AG, Melchers F, Winkler TH. Downregulation of RAG1 and RAG2 gene expression in preB cells after functional immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement. Immunity. 1995;3:601–608. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehlich A, Martin V, Müller W, Rajewsky K. Analysis of the B-cell progenitor compartment at the level of single cells. Curr Biol. 1994;4:573–593. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leonard WJ, Depper JM, Crabtree GR, Rudikoff S, Pumphrey J, Robb RJ, Krönke M, Svetlik PB, Peffer NJ, Waldmann TA, Greene WC. Molecular cloning and expression of cDNAs for the human interleukin-2 receptor. Nature (Lond) 1984;311:626–631. doi: 10.1038/311626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishi M, Ishida Y, Honjo T. Expression of functional interleukin-2 receptors in human light chain/Tac transgenic mice. Nature (Lond) 1988;331:267–269. doi: 10.1038/331267a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karasuyama H, Rolink A, Melchers F. A complex of glycoproteins is associated with VpreB/lambda 5 surrogate light chain on the surface of μ heavy chain–negative early precursor B cell lines. J Exp Med. 1993;178:469–478. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanahan D. Heritable formation of pancreatic β-cell tumours in transgenic mice expressing the recombinant insulin/simian virus 40 oncogenes. Nature (Lond) 1985;315:115–122. doi: 10.1038/315115a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dandoy-Dron F, Itier J-M, Monthioux E, Bucchini D, Jami J. Tissue-specific expression of a rat insulin 1 gene in vivo requires both the enhancer and the promotor regions. Differentiation. 1995;58:291–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1995.5840291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen JM, Forbush KA, Perlmutter RM. Functional dissection of the lck promotor. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2758–2768. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuberger MS. Expression and regulation of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene transfected into lymphoid cells. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1983;2:1373–1378. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillies SD, Morrison SL, Oi VT, Tonegawa S. A tissue-specific transcription enhancer element is located in the major intron of a rearranged immunoglobulin heavy chain gene. Cell. 1983;33:717–728. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banerji J, Olson L, Schaffner W. A lymphocytespecific cellular enhancer is located downstream of the joining region in immunoglobulin heavy chain genes. Cell. 1983;33:729–740. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elliot JI, Festenstein R, Tolaini M, Kioussis D. Random activation of a transgene under the control of a hybrid hCD2 locus control region/Ig enhancer regulatory element. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1995;14:575–584. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winkler TH, Rolink A, Melchers F, Karasuyama H. Precursor B cells of mouse bone marrow express two different complexes with the surrogate light chain on the surface. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:446–450. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rolink A, Haasner D, Nishikawa S, Melchers F. Changes in frequencies of clonable pre B cells during life in different lymphoid organs of mice. Blood. 1993;81:2290–2300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bain G, Maandag EC, Izon DJ, Amsen D, Kruisbeek AM, Weintraub BC, Krop I, Schlissel MS, Feeney AJ, van-Roon M, et al. E2A proteins are required for proper B cell development and initiation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements. Cell. 1994;79:885–892. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhuang Y, Soriano P, Weintraub H. The helixloop-helix gene E2A is required for B cell formation. Cell. 1994;79:875–884. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin H, Grosschedl R. Failure of B-cell differentiation in mice lacking the transcription factor EBF. Nature (Lond) 1995;376:263–267. doi: 10.1038/376263a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]