Abstract

The developmental commitment to a T helper 1 (Th1)- or Th2-type response can significantly influence host immunity to pathogens. Extinction of the IL-12 signaling pathway during early Th2 development provides a mechanism that allows stable phenotype commitment. In this report we demonstrate that extinction of IL-12 signaling in early Th2 cells results from a selective loss of IL-12 receptor (IL-12R) β2 subunit expression. To determine the basis for this selective loss, we examined IL-12R β2 subunit expression during Th cell development in response to T cell treatment with different cytokines. IL-12R β2 is not expressed by naive resting CD4+ T cells, but is induced upon antigen activation through the T cell receptor. Importantly, IL-4 and IFN-γ were found to significantly modify IL-12 receptor β2 expression after T cell activation. IL-4 inhibited IL-12R β2 expression leading to the loss of IL-12 signaling, providing an important point of regulation to promote commitment to the Th2 pathway. IFN-γ treatment of early developing Th2 cells maintained IL-12R β2 expression and restored the ability of these cells to functionally respond to IL-12, but did not directly inhibit IL-4 or induce IFN-γ production. Thus, IFN-γ may prevent early Th cells from premature commitment to the Th2 pathway. Controlling the expression of the IL-12R β2 subunit could be an important therapeutic target for the redirection of ongoing Th cell responses.

In chronic immune responses, cytokine production by CD4+ T cells may polarize toward either a Th1 or Th2 response (1). Th1 cytokines, such as IFN-γ and lymphotoxin, promote phagocytic and inflammatory responses, whereas Th2 cytokines like IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6 promote allergic and eosinophilic responses and provide specific B cell help associated with IgE isotype switching (1–4). Cytokines present in the early stages of antigen driven CD4+ T cell activation help to determine the specific pattern of Th phenotype that develops (4). Th1 development is enhanced when naive T cells are activated in the presence of IL-12 (5, 6). IFN-γ assists Th1 development initially through a mechanism consistent with promoting the ability of naive T cells to respond to IL-12 (7, 8). Conversely, Th2 cells develop when IL-4 but not IL-12 is present during activation of naive T cells (5, 9). In addition, cross regulation between these subsets takes place, so that development of one subset is inhibited by cytokines produced by the other (2, 4). This mechanism provides one way for responses to become self-reinforcing and helps to stabilize the emergence of polarized phenotypes. For example, the Th2 cytokines interleukin 4 (IL-4) and IL-10 suppress Th1 development by inhibiting production of IFN-γ and IL-12 (10), whereas IFN-γ has been thought to selectively limit the outgrowth of Th2 cells (11–13).

Recently, reversibility of Th2 responses has been examined both in vivo and in vitro (14–18). Th2 responses developing during infection by Leishmania major of susceptible BALB/c mice were found to revert to healing Th1-type responses upon treatment with IL-12 and the antibiotic compound Pentostam (14) or under certain conditions in models employing T cell transfers into scid mice (15). These studies suggest that emerging Th2 responses may be reversible. In vitro analysis of TCR-transgenic naive T cells showed that emergent Th2 responses become unresponsive to IL-12 and effectively resist reversal to Th1 phenotype (16, 17). We partially characterized the mechanism of in vitro resistance of Th2 cells to IL-12 as a defect in proximal IL-12 signaling (17). T cells activated in vitro for 3 d under strongly polarizing conditions (IL-4 and anti–IL-12) were unable to phosphorylate Jak2, Stat1, Stat3, and Stat4 in response to IL-12 (17). Expression of the IL-12R β1 subunit was similar in Th1 and Th2 cells, suggesting that this receptor subunit was not responsible for lack of IL-12 signaling in Th2 cells. Also, both Th1 and Th2 cells expressed similar levels of the relevant kinases, Jak2 and Tyk2 and the STAT proteins Stat1, Stat3, and Stat4 (17). Thus, the precise molecular basis for the signaling defect remained unclear. We also compared loss of IL-12 responsiveness in T cells from Balb/c (L. major susceptible) and B10.D2 (L. major resistant) strains and found a correlation between resistance and the maintenance of T cell IL-12 responsiveness. Thus, when stimulated without addition of cytokines or anti-cytokine antibodies, B10.D2 T cells maintained IL-12 responsiveness whereas Balb/c T cells lost IL-12 responsiveness (19). We suggested that prolonging the period of IL-12 responsiveness in an emerging T cell response may allow resistant strains to reverse the early Th2-type response toward a protective Th1 response due to the action of IL-12 generated during the later stages of infection (19, 20). However, the precise molecular basis for the defect in IL-12 signaling still remained unclear (19).

Recently, a second component of the IL-12 receptor (IL-12R)1 was identified and cloned. This component, the IL-12 receptor β2 subunit, is necessary for IL-12 signaling through the Jak/STAT pathway. In the present report, we now show that the basis for the IL-12 signaling defect in Th2 cells is the specific down regulation of this newly identified IL-12 receptor component, the IL-12R β2 subunit. To determine the basis for this selective loss, we examined IL-12R β2 subunit expression in response to T cell treatment with cytokines. IFN-γ treatment of Th cells developing in Th2-inducing conditions induced the expression of IL-12R β2 mRNA and restored the ability of these T cells to functionally respond to IL-12. IFN-γ may thus prevent early Th cells from premature commitment to the Th2 pathway. These results help to resolve some of the discrepancies reported regarding the reversibility of ongoing murine Th2 responses in vivo and in vitro. They may also help to explain some of the differences observed between murine and human Th2 cells.

Materials and Methods

Cytokines and Antibodies.

Recombinant human IL-2 was provided by Takeda (Osaka, Japan), recombinant murine IL-4 by Genzyme (Cambridge, MA), recombinant murine IL-12 by Hoffmann-La Roche (Nutley, NJ), and recombinant murine IFN-γ by Genentech (South San Francisco, CA). Anti–IL-12 mAb (TOSH) was supplied by Drs. C.S. Tripp and E.R. Unanue (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO) (22), anti–IFN-γ mAb (H22) by Dr. R.D. Schreiber (23), and polyclonal rabbit antiserum specific for Stat4 was provided by Dr. James Darnell (Rockefeller University, New York, NY) (24, 25). The anti-phosphotyrosine reagent RC20 was purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). Anti–IL-4 mAb 11B11 has been described (26).

Medium and Peptides.

T cells were maintained in IMDM (Washington University Tissue Culture Support Center, St. Louis, MO) supplemented as described (17). OVA peptide from chicken ovalbumin (residues 323-339) was synthesized on an Applied Biosystems model 430 peptide synthesizer (Foster City, CA).

Animals.

Mice transgenic for the DO11.10 αβ-TCR (27) were maintained on the BALB/c background. Female BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN).

T Cell Purification and T Cell Cultures.

Mel-14hi/CD4+ T cells were isolated from spleens of 4–6 wk old unimmunized DO11.10 TCR-transgenic mice on a FACS® Vantage cell sorter as described (28) yielding purities of >98%. 2.5 × 105 FACS®-sorted Mel14hi/CD4+ DO11.10 T cells were stimulated in 2 ml cultures with 0.3 μM OVA peptide presented by irradiated BALB/c splenocytes (2,000 rads, 6 × 106/well) in the presence of 10 U/ml IL-12 and 10 μg/ml anti–IL-4 (11B11) to promote Th1 phenotype development, 200 U/ml IL-4 and 3 μg/ml anti–IL-12 (TOSH) to promote Th2 phenotype development, or the combination of 10 U/ml IL-12 and 200 U/ml IL-4. At 72 h the cells were expanded threefold in fresh medium. These differentiated Th cells were harvested on day 7, washed, and counted. 1.25 × 105 T cells were restimulated with OVA peptide and BALB/c splenocytes with or without addition of cytokines or anti-cytokine antibodies as indicated in the figure legends. Supernatants were collected after 48 h and analyzed by capture ELISA for IFN-γ and IL-4 (29).

For immunoprecipitations from primary stimulations, 1 × 106 Mel-14hi/CD4+ DO11.10 T cells were stimulated in 10 ml cultures with OVA peptide (0.3 μM) and irradiated BALB/c splenocytes (4 × 107) under the indicated primary culture conditions. At 72 h the cells were expanded 10-fold in fresh medium containing 40 U/ml IL-2. On day 5 after primary stimulation, the Th cells were washed and incubated in complete media containing 10% FCS for 3–12 h before incubation with cytokines.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis.

Analysis of Stat4 tyrosine phosphorylation was performed as described (30). In brief, total cellular lysates of 1.5–2.5 × 107 T cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-Stat4 antisera and resolved by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, blots were probed with RC20 (1:2,500). Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-Stat4 antisera (1:3,000).

Northern Blot Analysis.

Total T cell RNA was isolated from Th1 and Th2 cells using RNAzol RNA isolation solvent (TelTest, Friendswood, TX). Northern blot analysis was performed with 15 μg of total RNA per lane, and membranes were sequentially probed with the full-length murine IL-12 receptor β1 subunit cDNA (31), the full-length murine IL-12 receptor β2 subunit cDNA and the cDNAs for GAPDH (32) or pHE7 (33).

Results

The IL-12R β2 Subunit Is Expressed in Th1, but not in Th2 Cells.

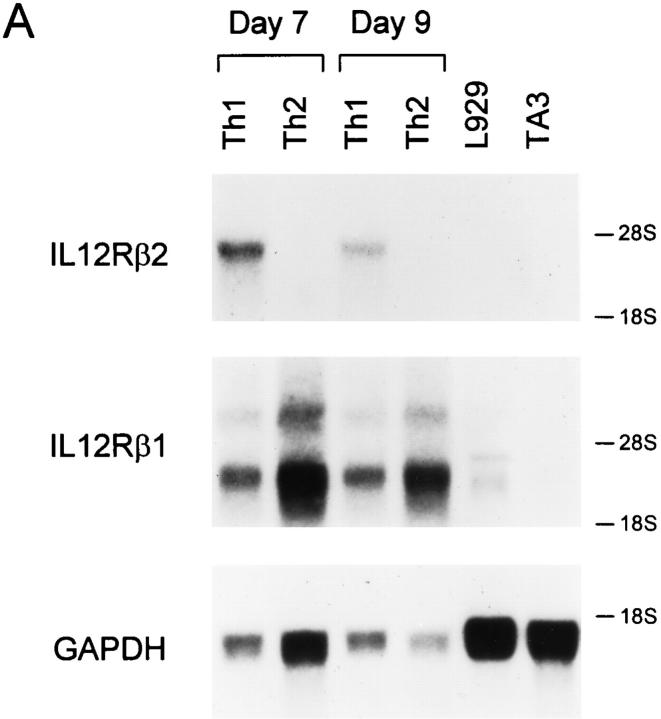

Mel-14hi CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 TCRtransgenic mice were purified and activated with antigen in the presence of IL-12 and antibodies to IL-4, or IL-4 and antibodies to IL-12, for 7 d to generate polarized Th1 or Th2 populations (17). Subsequently, IL-12R expression was analyzed by Northern blotting on day 7 and 9 after secondary activation (Fig. 1 A). Th1 cells expressed the IL-12R β2 mRNA at high levels on these days. In contrast, IL-12R β2 mRNA was completely absent in Th2 cells harvested at these same time points. As we previously observed (17), IL-12R β1 mRNA was present in both Th1 and Th2 cells (Fig. 1 A, top).

Figure 1.

IL-12R β2 subunit mRNA is detected in Th1 but not Th2 cells. (A) Naive CD4+ T cells were purified by FACS® from unimmunized DO11.10 TCR-transgenic mice as described in Materials and Methods (5), activated with OVA peptide and APCs under either Th1- or Th2-inducing conditions and allowed to develop for 7 days. On day 7, the Th1 and Th2 cells were washed, restimulated and allowed to proliferate for 7 or 9 d when cells were harvested and total cellular RNA was isolated. As tissue controls, total cellular RNA was isolated from the B cell hybridoma TA3 and the fibroblast cell line L929. Northern blot analysis was performed using as probes the full-length murine IL-12R β2 subunit cDNA (top), the full-length murine IL-12R β1 subunit cDNA (middle), and the GAPDH cDNA (bottom). (B and C). Total cellular RNA was isolated from naive T cells after purification by FACS®. Naive T cells isolated by cell sorting were activated to induce Th1 or Th2 development, and harvested on days 3, 5, and 7 after primary antigen activation. Total cellular RNA was examined by Northern analysis as described above for IL-12R β2 subunit cDNA (top), the IL-12R β1 subunit cDNA (middle), or pHE7 cDNA (bottom).

To determine how rapidly expression of IL-12R β2 mRNA subsided during Th2 development, we induced Th1 and Th2 differentiation from naive CD4+ T cells and analyzed IL-12R β2 expression on days 3, 5, and 7 after primary activation. To test expression in naive T cells, we obtained naive CD4+ T cells by cell sorting and prepared mRNA for Northern analysis (Fig. 1 B). Neither IL-12R β1 nor IL-12R β2 mRNA was detectable in naive T cells (Fig. 1 B). On days 3, 5, and 7 after primary activation, developing Th1 cells expressed high levels of both the IL-12R β1 and IL-12R β2 mRNA (Fig. 1, B and C). On day 3, Th2 cells expressed IL-12R β1 mRNA at comparable or slightly higher levels than Th1 cells, but expressed only very low levels of IL-12R β2 mRNA (Fig. 1 C). By days 5 and 7 after primary activation IL-12R β2 mRNA was undetectable in Th2 cells (Fig, 1 C).

IL-4 and IFN-γ Regulate Functional Responsiveness to IL-12.

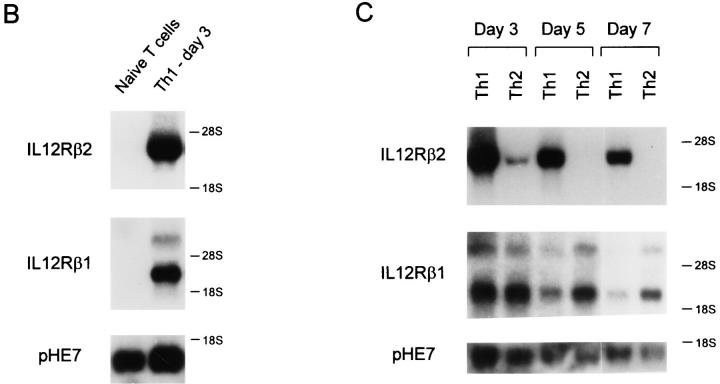

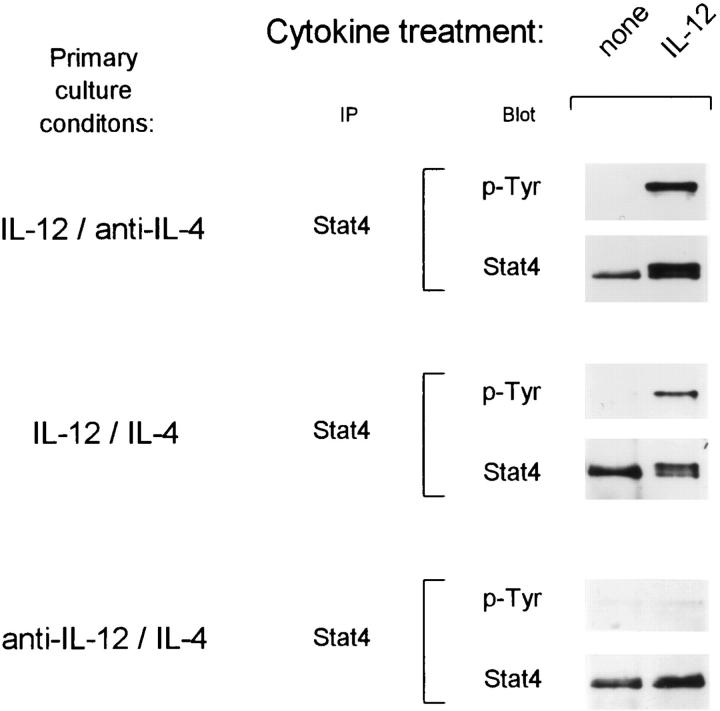

We next asked what conditions controlled the maintenance of IL-12 signaling in developing Th cells. IL-4 was thought to dominate IL-12 for effects on T helper phenotype development (5, 34), since the addition of IL-4 and IL-12 together led to Th2 development both in TCR-transgenic and anti-CD3 driven systems (5, 34). We first wished to determine if it was the lack of IL-4 in primary cultures that allowed the maintenance of IL-12 responsiveness in developing Th1 cells. Thus, we activated naive T cells in the presence of IL-4 and IL-12 together in the primary culture and assessed IL-12 responsiveness on day 5 after primary stimulation (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, these T cells were able to phosphorylate Stat4 upon IL-12 treatment (Fig. 2, middle), similar to Th1 cells (Fig. 2, top), but unlike IL-12 unresponsive Th2 cells (Fig. 2, bottom). This maintenance of Stat4 phosphorylation correlated with functional IL-12 responses in these T cells as measured by IL-12–induced IFN-γ production (Fig. 3). T cells arising from stimulation in IL-4 and IL-12 together showed significant IL-12 induced IFN-γ production during restimulation (Fig. 3, top). Restimulation of these cells without exogenously added IL-12 led to production of 180 U/ml IFN-γ, while addition of IL-12 increased IFN-γ production to 400 U/ml. Because these T cells arose in IL-4, they acquired the Th2-type property of producing IL-4 and IL-10, two cytokines which inhibit IFN-γ production (35, 36). In this system, IL-10 could also be produced by other cells used as APCs. Neutralization of IL-4 and IL-10 revealed a significantly increased IL-12– mediated induction of IFN-γ, from less than 50 U/ml of IFN-γ produced upon restimulation in the absence of IL-12 to 1,300 U/ml of IFN-γ produced in the presence of IL-12 (Fig. 3, top). In contrast, the control Th2 cells produced very low amounts of IFN-γ (20 U/ml) upon restimulation in the presence of IL-12, a level which was not increased by neutralization of IL-4 and IL-10 (Fig. 3, bottom). Taken together, these results therefore suggest that the presence of IL-12 during primary T cell activation, not the absence of IL-4, was responsible for maintenance of functional responsiveness to IL-12.

Figure 2.

Activation in the presence of IL-4 and IL-12 results in the maintenance of the IL-12 signaling pathway. FACS®-sorted naive CD4+ DO11.10 T cells were cultured with OVA peptide and irradiated BALB/c splenocytes in the presence of 10 U/ml IL-12 and 10 μg/ml anti–IL-4 to promote Th1 differentiation (upper), 10 U/ml IL-12 and 200 U/ml IL-4 (middle), or 200 U/ml IL-4 and 3 μg/ml anti–IL-12 to promote Th2 differentiation (bottom). After 72 h the cells were expanded 10-fold in fresh medium containing 40 U/ml IL-2. On day 5 after primary antigen activation whole cell lysates from developing T cells (1.5–2.0 × 107) were prepared after incubation for 25 min with medium alone or with 10 U/ml IL-12. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with Stat4 antiserum, separated by SDS-PAGE (7% gel), transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with the anti-phosphotyrosine reagent RC20 as described (30). After exposure, blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-Stat4 antisera.

Figure 3.

Activation in the presence of IL-4 and IL-12 results in the maintenance of functional IL-12 responsiveness. FACS®-sorted naive CD4+ DO11.10 T cells were cultured for seven days with OVA peptide and irradiated BALB/c splenocytes under the indicated primary culture conditions. Cultures were harvested on day 7, washed, and restimulated at 1.25 × 105 T cells/well with OVA peptide and BALB/c splenocytes in the presence of the indicated cytokines or anti-cytokine antibodies. Supernatants collected after 48 h were analyzed by ELISA for IFN-γ.

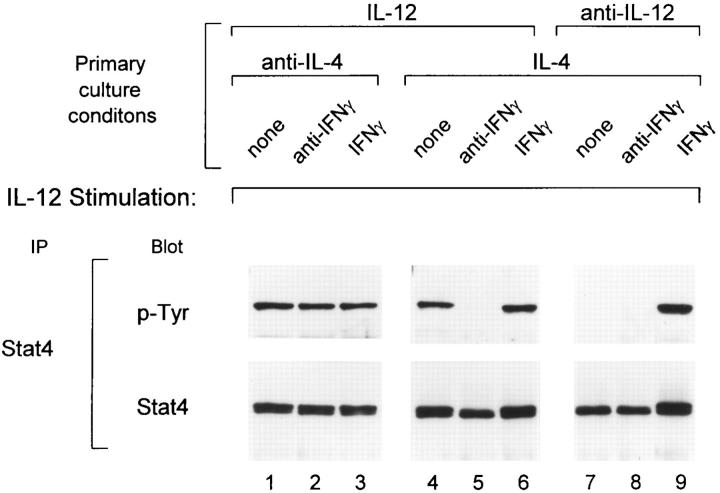

We suspected that IL-12 was not the primary stimulus for induction of the IL-12R β2 subunit, since a cytokine cannot signal unless its receptor is already expressed at some level on the cell surface. Previously, IFN-γ has been shown to be required for IL-12–induced Th1 development from naive BALB/c T cells (7, 34). IL-12 is known to induce IFN-γ production from CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as NK cells. Since these cells are present in the irradiated splenocytes used as APCs, we suspected that IFN-γ could be inducing the expression of the IL-12R β2 subunit. To test this possibility, combinations of IL-12, IFN-γ and IL-4, or the corresponding neutralizing antibodies were added during primary T cell activation and the IL-12 responsiveness of these developing Th cells was analyzed by measuring IL-12–induced Stat4-phosphorylation on day 5 after activation (Fig. 4). Th cells activated in the presence of both IL-12 and IL-4 maintained IL-12-induced Stat4 phosphorylation (Fig. 4, lane 4). The maintenance of IL-12 responsiveness on these cells was completely dependent on the production of endogenous IFN-γ during primary activation, since neutralization of IFN-γ abolished IL-12–induced Stat4 phosphorylation (Fig. 4, lane 5). Under Th2 inducing conditions (IL-4 and anti–IL-12), Th2 cells lost the ability to phosphorylate Stat4 in response to IL-12 (Fig. 4, lane 7). However, addition of IFN-γ to this culture restored IL-12induced Stat4 phosphorylation (Fig. 4, lane 9). Finally, under Th1 inducing conditions (IL-12 and anti–IL-4), T cells retained the ability to phosphorylate Stat4 in response to IL-12 in a manner that was independent of IFN-γ (Fig. 4, lanes 1–3). In summary, (a) the presence of IL-4 during primary activation inhibits IL-12 signaling in developing Th cells, and (b) IFN-γ is able to override this inhibition and restore IL-12 signaling in early Th cells.

Figure 4.

IFN-γ restores the IL-12 signaling pathway in developing Th2 cells. FACS®-sorted naive CD4+ DO11.10 T cells were cultured with OVA peptide and irradiated BALB/c splenocytes under the conditions indicated. In the primary cultures, IFN-γ levels were either unaltered (none), neutralized with 30 μg/ml of the anti–IFN-γ mAb H22 (anti–IFN-γ) or 100 U/ml of IFN-γ (IFN-γ) were added as indicated. On day 5 after primary antigen activation whole cell lysates from developing T cells (20 × 106) were prepared after incubation for 25 min with 10 U/ml IL-12. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with Stat4 antiserum, separated by SDS-PAGE (7% gel), transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with the anti-phosphotyrosine reagent RC20. After exposure, blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-Stat4 antisera.

IL-4 and IFN-γ Regulate Expression of the IL-12R β2 Subunit.

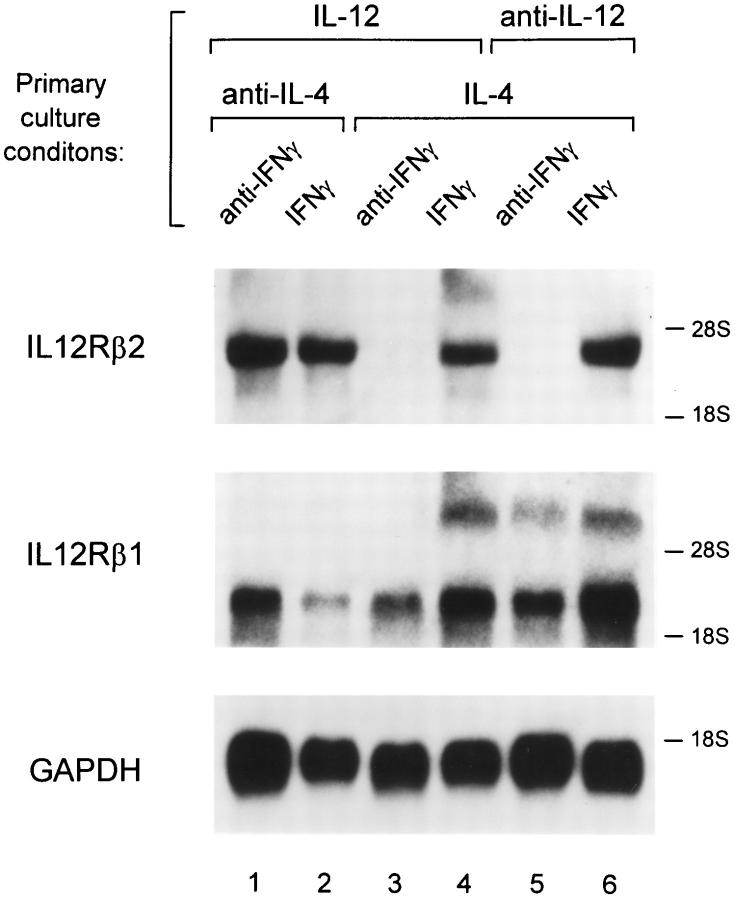

To test whether IFN-γ–induced restoration of IL-12 signaling involved induction of the IL-12R β2 subunit, we performed Northern blot analysis of Th cells derived under the various conditions described in Fig. 4. T cells activated in the presence of both IL-4 and IL-12 expressed the IL-12R β2 mRNA (Fig. 5, lane 4). This expression was dependent on endogenous IFN-γ production, since neutralization of IFN-γ in the primary culture led to the disappearance of IL-12R β2 mRNA (Fig. 5, lane 3). T cells arising from stimulation in the presence of IL-4, anti–IL-12 mAb and exogenous IFN-γ added during primary activation expressed high levels of the IL-12R β2 mRNA (Fig. 5, lane 6). Addition of anti–IFN-γ mAb blocked expression of IL-12R β2 mRNA (Fig. 5, lane 5). Th1 cells, arising from stimulation in the presence of IL-12 plus anti–IL-4 mAb, expressed IL-12R β2 mRNA independently of IFN-γ (Fig. 5, lanes 1 and 2). Thus, in each case, IL-12-inducible Stat4 phosphorylation (Fig. 4) correlated with expression of the IL-12R β2 mRNA (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Regulation of IL-12R β2 subunit mRNA expression by IFN-γ. FACS®-sorted naive CD4+ DO11.10 T cells were cultured with OVA peptide and irradiated BALB/c splenocytes under conditions indicated. On day 5 after primary antigen activation total cellular RNA was isolated from the developing Th cells. Sequential Northern blot analysis was performed using as probes the full-length murine IL-12R β2 subunit cDNA (top), the full-length murine IL-12R β1 subunit cDNA (middle), and the GAPDH cDNA (bottom).

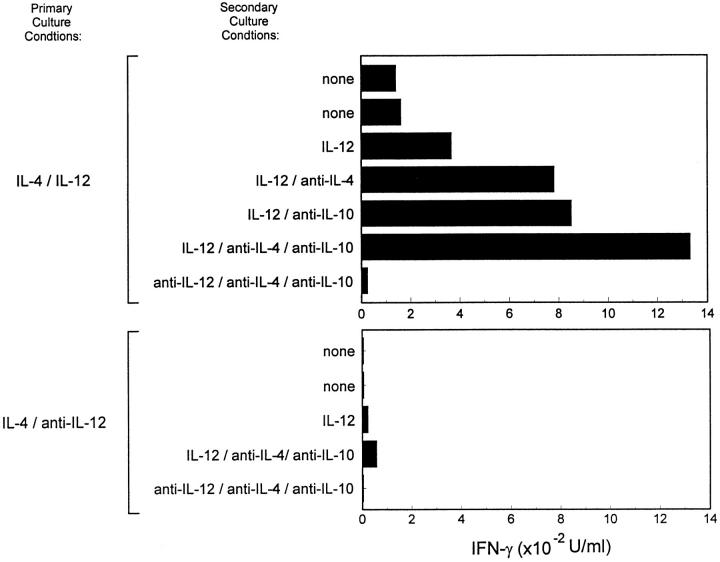

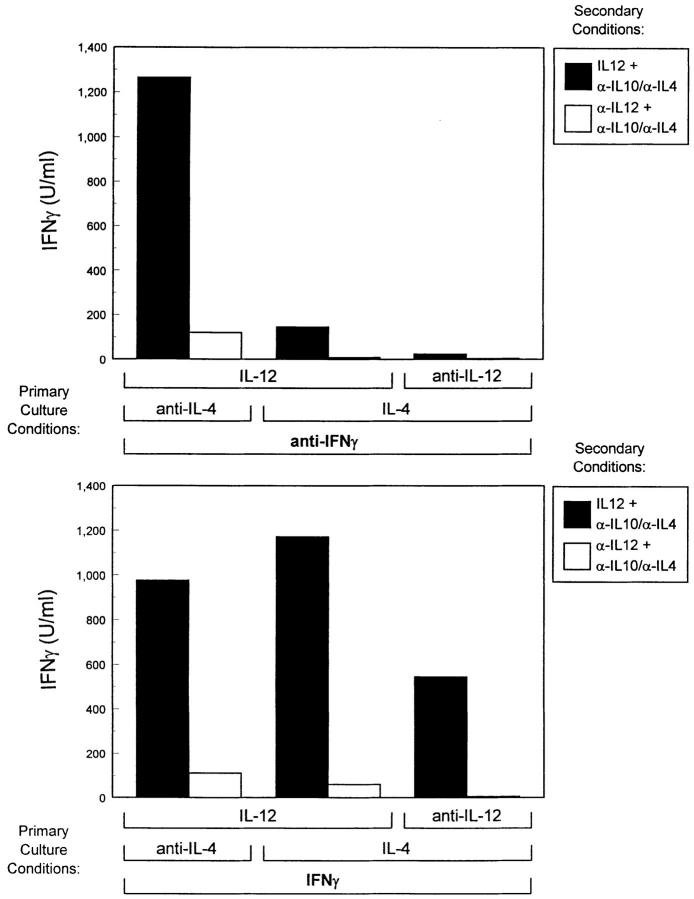

To examine whether IFN-γ treatment of developing Th cells during primary culture altered functional responses to IL-12, we measured the IL-12–dependent IFN-γ production in developing Th cells derived under the same conditions used in Fig. 5. Additionally, since production of endogenous IL-4 and IL-10 production by these cells directly inhibits IFN-γ production, we neutralized these cytokines to more clearly assess the true potential of these cells for IL-12 induced IFN-γ production. T cells arising from stimulation in IL-4 plus anti–IL-12 plus IFN-γ responded to IL-12 by producing 550 U/ml of IFN-γ in the secondary stimulation (Fig. 6, top), whereas addition of anti–IFN-γ mAb led to cells producing less than 50 U/ml of IFN-γ upon restimulation (Fig. 6, bottom). For T cells treated with IL-4 and IL-12 during primary activation, IFN-γ in the primary culture was required for IL-12 induced IFN-γ production upon secondary stimulation (Fig. 6, compare column 3 in top and bottom). For Th1 cells, arising from stimulation in the presence of IL-12 and anti–IL-4 mAbs, IFN-γ was not required for subsequent development of IL-12 responsiveness (Fig. 6, compare column 1 in top and bottom). Thus, IFN-γ regulates IL-12 responsiveness with the same pattern as it regulates IL-12R β2 expression in developing Th cells (Fig. 5).

Figure 6.

Examination of the functional IL-12 responses of developing Th cells. FACS®-sorted naive CD4+ DO11.10 T cells were cultured with OVA peptide and irradiated BALB/c splenocytes in the presence of the primary culture conditions indicated. Cultures were harvested on day 7, washed, and restimulated at 1.25 × 105 T cells/well with OVA peptide and BALB/c splenocytes in the presence of anti–IL-4 mAb (10 μg/ml 11B11) and anti IL-10 (20 μg/ml 2A5) and either IL-12 (10 U/ml) or anti–IL-12 (3 μg/ml TOSH). Supernatants collected after 48 h were analyzed by ELISA for IFN-γ.

Discussion

The data presented in this report provide a molecular basis for the previously described IL-12 unresponsiveness of Th2 cells and help explain several discrepancies that become apparent when comparing murine and human Th2 cells. Expression of the IL-12R β2 subunit is required for recruitment and activation of the STAT proteins involved in IL-12 signaling (37). When IL-4 is neutralized by antibodies, TCR-activation alone is sufficient for inducing IL-12R β2 expression. However, when even low levels of IL-4 are present, expression of the IL-12R β2 is inhibited. Thus, during in vitro Th2 development, IL-12R β2 expression is strongly inhibited by the IL-4 that is added to induce Th2 development. This inhibition leads to loss of IL-12 signaling capacity and helps to stabilize the emergent Th2 response against reversal of phenotype upon subsequent IL-12 exposure. Loss of IL-12 responsiveness may thus be an early step in the commitment of T cells to the Th2 pathway.

Regarding the role of IFN-γ in Th development, we find that IFN-γ overrides the IL-4–induced inhibition of IL-12R β2 expression. Thus, in T cells arising from stimulation with IL-4 and anti–IL-12 mAbs (i.e., fully Th2 inducing conditions), IFN-γ treatment during primary activation restored IL-12R β2 expression and functional IL-12 responsiveness. These T cells could produce IL-4 and IL-10 but retained the capacity for IL-12–induced IFN-γ production. The ability of Th2 cells to respond to IL-12 has previously been described for human (38, 39), but not murine Th2 cells (16, 17). This discrepancy can now be explained as follows. Murine Th2 cells lose expression of the IL-12R β2 due to the absence of IFN-γ in Th2 cultures. Human Th2 cells, on the other hand, express low but functional levels of the IL-12R β2 subunit, and human IL-12 R β2 expression is induced by IFN-α rather than IFN-γ (Francesco Sinigaglia, personal communication). Elucidation of the molecular basis for this distinct form of regulation between these two species will require the direct examination of the promoter/enhancer regions of the respective IL-12R β2 gene.

Our data also further clarify the role of IFN-γ in Th1 development. Results from several previous reports (7, 40) indicated that IFN-γ, although by itself not sufficient, was clearly required for IL-12–induced Th1 development from naive T cells. Other studies however did not identify such a requirement, even though similar TCR-transgenic experimental systems were used (41). This apparent discrepancy can now be explained by the established difference in IL-4 production that occurs in the two experimental mouse strains used. Studies that did not identify this requirement used TCR-transgenic mice on the C57/BL6 background in which very little IL-4 is produced (19, 28). The substantial amount of IL-4 produced by the BALB/c strain inhibits expression of IL-12R β2 and imposes the observed requirement for IFN-γ that allows IL-12R β2 expression (Guler, M., N. Jacobson, U. Gubler, K. Murphy, manuscript in preparation). In the C57 or B10 backgrounds, the absence of IL-4 allows IL-12R β2 expression to occur independently of IFN-γ.

In this report IFN-γ was not required for the expression of the IL-12 receptor β2 subunit on T cells differentiated to the Th1 phenotype with IL-12 and anti–IL-4. This result may be due to the complete absence of IL-4 in these primary cultures, thus artificially creating C57/BL6 or B10-like conditions. Moreover, when Th1 differentiation was induced using either IL-12 alone or IL-12 plus a low level of IL-4 (2–5 U/ml) in the primary stimulation, a requirement for IFN-γ during the primary activation for Th1 development was observed (data not shown). Thus a requirement for IFN-γ during Th1 development may only be evident in situations where low levels of IL-4 are present. In contrast, when IL-4 is absent during primary stimulation IFN-γ is not required for maintenance of the IL-12R β2 subunit on developing Th cells.

Finally, our results may be relevant for understanding responses to certain intracellular pathogens. For example, resistance to L. major in various strains of mice is complex and probably controlled by several genetic loci. The present study implies that cytokines could act to promote either susceptibility or resistance to pathogens by their distinct actions on IL-12R β2 expression. IL-4 inhibits expression of the IL-12R β2 subunit and imposes a requirement for IFN-γ to maintain IL-12 responsiveness. Thus, when IFN-γ production is limited, IL-4 production in early responses may critically inhibit IL-12R β2 expression, with significant impact on development of protective responses. In strains that produce IL-4 early, IFN-γ production may be critical for inducing IL-12R β2 expression on T helper cells to allow for IL-12–induced Th1 differentiation. NK cells may be an important in vivo source of such early IFN-γ production, since IFN-γ can be induced by the action of IL-12 and TNF on NK cells (42). As suggested by studies of the development of resistance to L. major (43, 44), NK cells may thus play an important role in Th1 development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. E. Unanue and R. Schreiber for helpful discussions and reagents. We thank Dr. J. Darnell for his gift of anti-Stat antiserum.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI34580, AI31238, and AI39676 and a grant from the American Cancer Society. S.J. Szabo was supported by training grant CA09547.

Footnotes

1 Abbreviation used in this paper: IL-2R, IL-12 receptor.

References

- 1.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. Heterogeneity of cytokine secretion patterns and functions of helper T cells. Adv Immunol. 1989;46:111–147. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60652-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sher A, Coffman RL. Regulation of immunity to parasites by T cells and T cell-derived lymphokines. Ann Rev Immunol. 1992;10:385–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiorentino DF, Bond MW, Mosmann TR. Two types of mouse T helper cell. IV. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by Th1 clones. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2081–2095. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seder RA, Paul WE. Acquisition of lymphokineproducing phenotype by CD4+T cells. Ann Rev Immunol. 1994;12:635–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsieh C-S, Macatonia SE, Tripp CS, Wolf SF, O'Garra A, Murphy KM. Development of Th1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science (Wash DC) 1993;260:547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.8097338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manetti R, Parronchi P, Giudizi MG, Piccinni M-P, Maggi E, Trinchieri G, Romagnani S. Natural killer cell stimulatory factor (interleukin 12 [IL-12]) induces T helper type 1 (Th1)-specific immune responses and inhibits the development of IL-4-producing Th cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1199–1204. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macatonia SE, Hsieh CS, Murphy KM, O'Garra A. Dendritic cells and macrophages are required for Th1 development of CD4+T cells from alpha beta TCR transgenic mice: IL-12 substitution for macrophages to stimulate IFN-gamma production is IFN-gamma-dependent. Intl Immunol. 1993;5:1119–1128. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.9.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenner CA, Guler ML, Macatonia SE, O'Garra A, Murphy KM. Roles of IFN-gamma and IFN-alpha in IL-12-induced T helper cell-1 development. J Immunol. 1996;156:1442–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Gros G, Ben-Sasson SZ, Seder RA, Finkelman FD, Paul WE. Generation of interleukin 4 (IL-4)- producing cells in vivo and in vitro: IL-2 and IL-4 are required for in vitro generation of IL-4-producing cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:921–929. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O'Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gajewski TF, Fitch FW. Anti-proliferative effect of IFN-gamma in immune regulation. I. IFN-gamma inhibits the proliferation of Th2 but not Th1 murine helper T lymphocyte clones. J Immunol. 1988;140:4245–4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pernis A, Gupta S, Gollob KJ, Garfein E, Coffman RL, Schindler C, Rothman P. Lack of interferongamma receptor β chain and the prevention of interferongamma signaling in Th1 cells. Science (Wash DC) 1995;269:245–247. doi: 10.1126/science.7618088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bach EA, Szabo SJ, Dighe AS, Ashkenazi A, Aguet M, Murphy KM, Schreiber RD. Ligand-induced autoregulation of IFN-gamma receptor β chain expression in T helper cell subsets. Science (Wash DC) 1995;270:1215–1218. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nabors GS, Afonso LC, Farrell JP, Scott P. Switch from a type 2 to a type 1 T helper cell response and cure of established Leishmania major infection in mice is induced by combined therapy with interleukin 12 and Pentostam. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3142–3146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holaday BJ, Sadick MD, Wang ZE, Reiner SL, Heinzel FP, Parslow TG, Locksley RM. Reconstitution of Leishmania immunity in severe combined immunodeficient mice using Th1- and Th2-like cell lines. J Immunol. 1991;147:1653–1658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez VL, Lederer JA, Lichtman AH, Abbas AK. Stability of Th1 and Th2 populations. Int Immunol. 1995;7:869–875. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabo SJ, Jacobson NG, Dighe AS, Gubler U, Murphy KM. Developmental commitment to the Th2 lineage by extinction of IL-12 signaling. Immunity. 1995;2:665–675. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy E, Shibuya K, Hosken N, Openshaw P, Maino V, Davis K, Murphy K, O'Garra A. Reversibility of T helper 1 and 2 populations is lost after longterm stimulation. J Exp Med. 1996;183:901–913. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guler ML, Gorham JD, Hsieh C, Mackey AJ, Steen RG, Dietrich WF, Murphy KM. Genetic susceptibility to Leishmania: IL-12 responsiveness in Th1 development. Science (Wash DC) 1996;271:984–987. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reiner SL, Zheng S, Wang Z-E, Stowring L, Locksley RM. Leishmania promastigotes evade interleukin 12 (IL-12) induction by macrophages and stimulate a broad range of cytokines from CD4+T cells curing initiation of infection. J Exp Med. 1994;179:447–456. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deleted in proof.

- 22.Tripp CS, Gately MK, Hakimi J, Ling P, Unanue ER. Neutralization of IL-12 decreases resistance to Listeria in SCID and C.B-17 mice. Reversal by IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 1994;152:1883–1887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiber RD, Hicks LJ, Celada A, Buchmeier NA, Gray PW. Monoclonal antibodies to murine gammainterferon which differentially modulate macrophage activation and antiviral activity. J Immunol. 1985;134:1609–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong Z, Wen Z, Darnell JE., Jr Stat3: a STAT family member activated by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to epidermal growth factor and interleukin-6. Science (Wash DC) 1994;264:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.8140422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong Z, Wen Z, Darnell JE., Jr Stat3 and Stat4: members of the family of signal transducers and activators of transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4806–4810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohara J, Paul WE. Production of a monoclonal antibody to and molecular characterization of B-cell stimulatory factor-1. Nature (Lond) 1985;315:333–336. doi: 10.1038/315333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy KM, Heimberger AB, Loh DY. Induction by antigen of intrathymic apoptosis of CD4+ CD8+TCR-lo thymocytes in vivo. Science (Wash DC) 1990;250:1720–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.2125367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsieh C, Macatonia SE, O'Garra A, Murphy KM. T cell genetic background determines default T helper phenotype development in vitro. J Exp Med. 1995;181:713–721. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urban JF, Madden KB, Svetic A, Cheever A, Trotta PP, Gause WC, Katona IM, Finkelman FD. The importance of Th2 cytokines in protective immunity to nematodes. Immunol Rev. 1992;127:205–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobson NG, Szabo SJ, Weber-Nordt RM, Zhong Z, Schreiber RD, Darnell JEJ, Murphy KM. Interleukin 12 signaling in T helper type 1 (Th1) cells involves tyrosine phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)3 and Stat4. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1755–1762. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chua AO, Wilkinson VL, Presky DH, Gubler U. Cloning and characterization of a mouse IL-12 receptor-beta component. J Immunol. 1995;155:4286–4294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tokunaga K, Nakamura Y, Sakata K, Fujimori K, Ohkubo M, Sawada K, Sakiyama S. Enhanced expression of a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 1987;47:5616–5619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao X, Kozak CA, Liu YJ, Noguchi M, O'Connell E, Leonard W J. Characterization of cDNAs encoding the murine interleukin 2 receptor (IL-2R) gamma chain: chromosomal mapping and tissue specificity of IL-2R gamma chain expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8464–8468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmitt E, Hoehn P, Huels C, Goedert S, Palm N, Rude E, Germann T. T helper type 1 development of naive CD4+T cells requires the coordinate action of interleukin-12 and interferon-gamma and is inhibited by transforming growth factor-beta. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:793–798. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore KW, O'Garra A, De Waal R, Malefyt, Vieira P, Mosmann TR. Interleukin-10. Ann Rev Immunol. 1993;11:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nielsch U, Zimmer SG, Babiss LE. Changes in NF-kappa B and ISGF3 DNA binding activities are responsible for differences in MHC and beta-IFN gene expression in Ad5- versus Ad12-transformed cells. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1991;10:4169–4175. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Presky DH, Yang H, Minetti LJ, Chua AO, Nabavi N, Wu CY, Gately MK, Gubler U. A functional interleukin 12 receptor complex is composed of two betatype cytokine receptor subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14002–14007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manetti R, Gerosa F, Giudizi MG, Biagiotti R, Parronchi P, Piccinni MP, Sampognaro S, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Trinchieri G, et al. Interleukin 12 induces stable priming for interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) production during differentiation of human T helper (Th) cells and transient IFN-gamma production in established Th2 cell clones. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1273–1283. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yssel H, Fasler S, de Vries JE, De Waal R, Malefyt IL-12 transiently induces IFN-gamma transcription and protein synthesis in human CD4+allergen-specific Th2 T cell clones. Intl Immunol. 1994;6:1091–1096. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.7.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsieh C-S, Macatonia SE, O'Garra A, Murphy KM. Pathogen induced Th1 phenotype development in CD4+alpha-beta-TCR trangenic T cells is macrophage dependent. Int Immunol. 1993;5:371–382. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seder RA, Gazzinelli R, Sher A, Paul WE. Interleukin 12 acts directly on CD4+T cells to enhance priming for interferon gamma production and diminishes interleukin 4 inhibition of such priming. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10188–10192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tripp CS, Wolf SF, Unanue ER. Interleukin 12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha are costimulators of interferon gamma production by natural killer cells in severe combined immunodeficiency mice with listeriosis, and interleukin 10 is a physiologic antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3725–3729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott P. IFN-gamma modulates the early development of Th1 and Th2 responses in a murine model of cutaneous Leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1991;147:3149–3155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scharton TM, Scott P. Natural killer cells are a source of interferon gamma that drives differentiation of CD4+T cell subsets and induces early resistance ot Leishmania major in mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:567–577. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]