Abstract

BNIP3, a BH3 domain only Bcl-2 protein, has been identified as a mitochrondrial mediator of hypoxia-induced cell death. Since cyanide produces histotoxic anoxia (chemical hypoxia), the present study was undertaken in primary cortical cells to determine involvement of the BNIP3 signaling pathway in cyanide-induced death. Over a 20 h exposure KCN increased BNIP3 expression, followed by a concentration-related apoptotic death. To determine if BNIP3 plays a role in the cell death, expression was either overexpressed with BNIP3 cDNA (BNIP3+) or knocked down with small interfering RNA (RNAi). In BNIP3+ cells, cyanide-induced apoptotic death was markedly enhanced and preceded by reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and elevated caspase 3 and 7 activity. Pretreatment with the pan caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk suppressed BNIP3+-mediated cell death, thus confirming a caspase-dependent apoptosis. On the other hand, BNIP3 knock down by RNAi or antagonism of BNIP3 by a transmembrane-deleted dominant-negative mutant (BNIP3ΔTM) markedly reduced cell death. Immunohistochemical imaging showed that cyanide stimulated translocation of BNIP3 from cytosol to mitochondria and displacement studies with BNIP3ΔTM showed that integration of BNIP3 into the mitochondrial outer membrane was necessary for the cell death. In BNIP3+ cells, cyclosporin-A, an inhibitor of mitochondrial pore transition, blocked the cyanide-induced reduction of Δψm and decreased the apoptotic death. These results demonstrate in cortical cells that cyanide induces a rapid upregulation of BNIP3 expression, followed by translocation to the mitochondrial outer membrane to reduceΔψm This was followed by mitochondrial release of cytochrome c to execute a caspase-dependent cell death.

Keywords: cyanide, BNIP3, apoptosis, neurotoxicity

INTRODUCTION

BNIP3 (Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein 3) is a member of the Bcl-2 mitochondrial protein family that has a single Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3) domain and is a pro-death factor (Lee and Paik, 2006). Under control conditions BNIP3 is expressed at low levels in a variety of tissues, including brain where it is primarily localized to the cytosol (Vande Velde et al., 2000; Lee and Paik, 2006). BNIP3 appears to be a key regulator of hypoxia-ischemic cell death and activation can initiate either apoptotic or non-apoptotic modes of cell death, depending on cell type and stimulus (Crow, 2002; Regula et al., 2002). In hypoxia, BNIP3 undergoes a rapid up-regulation, followed by translocation from cytosol to mitochondria for initiation of the cell death cascade. BNIP3 is inserted in the outer mitochondrial membrane via its C-terminus, with the N-terminus remaining in the cytosol (Ray et al., 2000). Following membrane insertion, BNIP3 mediates mitochondrial dysfunction to induce cell death (Chen et al., 1997; Vande Velde et al., 2000; Yan et al., 2006).

Following hypoxia, BNIP3 may mediate either necrotic or apoptotic deaths of cardiac myocytes and brain cells (Graham et al., 2004). The overexpression of BNIP3 induces apoptotic cell death (Chen et al., 1997; Chen et al., 1999; Vande Velde et al., 2000). Over-expression opens the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) pore which disrupts the Δψm and activates the cell death cascade (Vande Velde et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2002). It has been postulated that BNIP3 may exert an effect through either functional or physical interaction with multiple death factors at mitochondrial and extra-mitochondrial sites. BNIP3 can induce a caspase-dependent apoptosis by heterodimerizing with Bcl-2/Bcl-XL through binding to the BH3 domain, thus neutralizing the anti-apoptotic activity (Chen et al., 1997; Ray et al., 2000). On the other hand, BNIP3-mediated cell death can be caspase-independent producing an atypical cell death exhibiting necrotic morphological features (Vande Velde et al., 2000). The mode of death activated by BNIP3 is dependent on level of expression, functional interaction with Bcl-2 and/or non-Bcl-2 proteins and the level of mitochondrial dysfunction (dissipation of Δ ψm and MPT pore opening) (Itoh et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003).

Cyanide is a rapid-acting neurotoxicant that inhibits cytochrome oxidase (complex IV) to block mitochondrial respiration, leading to lowering of ΔΨm, reduced ATP levels and enhanced intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (Jones et al., 2003). Cyanide can produce two distinct modes of death in the nervous system, depending on cell type and level of oxidative insult (Mills et al., 1999; Prabhakaran et al., 2002). In primary rat cortical cells, cyanide induces predominately apoptotic death, whereas mesencephalic cells undergo necrotic death. Cyanide-induced apoptosis of cortical cells is caspase-dependent and involves loss of Δψm and MPT pore opening (Shou et al., 2000; Prabhakaran et al., 2002). Pharmacological inhibition of either the caspases or the MPT pore blocked cyanide-induced cortical cell death, thus establishing a link between mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. Subsequent studies have shown that the Bcl-2 protein family is involved in regulation of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and activation of the caspase cascade in cyanide-induced cortical cell death (Shou et al., 2002).

Since we have previously shown in mice that cyanide produces apoptotic death of brain cortical cells (Mills et al., 1999), the present study was undertaken to examine the role of BNIP3 in cyanide-induced death of primary rat cortical cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell culture

Primary cortical cells were prepared from embryonic day 16 Sprague-Dawley rats as previously described (Prabhakaran et al., 2002). In brief, cerebral cortices were dissected and cells dissociated in 0.025% trypsin at 37°C for 15 min. Digestion was stopped by adding trypsin inhibitor and DNase I. Cells were passed through a Pasteur pipette several times and plated at a density of 5 × 105 cells/cm2 onto 6-well culture plates or 75 mm2 culture flasks pre-coated with 10 μg/ml poly-L-lysine. Cells were grown in high glucose Delbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10% horse serum, 2 mM glutamine and 1 ml penicillin/streptomycin (5000 U/ml) at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. Cytosine arabinofuranoside (10 μM) was added at 6 days in vitro for 24 h to limit growth of glial cells. Medium was changed twice a week until experiments were carried out at 10–12 days in vitro. At the time of experimentation, the percent astrocytes in the culture was approximately 30% as estimated by immunostaining of the astrocyte specific marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and 70% neurons as determined by immunostaining of the neuron-specific marker microtubule associated protein-2 (MAP2).

Transient transfection of primary cortical cells

The BNIP3 cDNA was cloned into the expression vector pCDNA3.1 as previously described [10]. Transient transfections of BNIP3 plasmid or BNIP3ΔTM containing the transmembrane-deleted BNIP3 cDNA or siRNA were performed with Lipofectamine 2000™ (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as described by Krichevsky and Kosik (2002). Lipofectamine diluted in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was applied to the plasmids or dsRNA and incubated for 45 min. To each microtiter plate well containing cells, 1 μg of plasmid or 0.2 μg of 21-bp dsRNA (siRNA) containing Lipofectamine 2000™ was applied in a final volume of 1 ml. The medium was changed to regular cortical cell culture medium (previously described in the cell culture section) 5 h after transfection, and cells were treated with KCN 24 h after transfection. The overall transfection efficiency, as assessed by GFP positive cells, was estimated to be 10–12%.

siRNA preparation and transient transfection

siRNA corresponding to the BNIP3 was synthesized by Ambion, Inc. (Austin, TX, USA) with 5′ phosphate, 3′ hydroxyl, and two base overhangs on each strand. The gene-specific sequences used for BNIP3 interference were: sense 5′-GCUGCCCUGCUACCUCUCAtt-3′ and antisense 5′-UGAGAGGUAGCAGGGCAGCtt-3′ annealing for duplex siRNA formation was performed as described by the manufacturer. Lipofectamine 2000™ was used to transfect siRNA or negative control RNAi containing a 21-base mRNA sequence starting with the AA dinucleotide into cortical cells (Krichevsky and Kosik, 2002).

Cytotoxicity analysis

Cortical cells were incubated with 100–400 μM KCN for 24 h and cell death was determined by the 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Kitazawa et al., 2001). After treatment with KCN, cells were incubated in serum-free medium containing 0.25 mg/ml MTT for 3 h at 37°C. Formation of formazan from tetrazolium was measured at 570 nm with a reference wavelength at 630 nm using a microplate reader.

TUNEL assay for apoptosis

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) was performed on paraformaldehyde (4% in phosphate buffered saline)-fixed cells using the Apoptag™ in situ apoptosis detection kit (Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Briefly, cells were pre-incubated in equilibration buffer containing 0.1 M potassium cacodylate (pH 7.2), 2 mM CaCl2, and 0.2 mM dithiothreitol for 10 min at room temperature and then incubated in TUNEL reaction mixture (containing 200 mM potassium cacodylate (pH 7.2), 4 mM MgCl2, 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 30 μM biotin-16-dUTP, and 300 U/ml TdT) in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 1 h. After incubating in stop/wash buffer for 10 min, the elongated digoxigenin-labeled DNA fragments were visualized using anti-digoxigenin peroxidase antibody solution followed by staining with DAB/H2O2 (0.2 mg/ml diaminobenzidine tetrachloride and 0.005% H2O2 in PBS, pH 7.4). Cells were then counterstained with hematoxylin. The selectivity of the assay is based on the presence of 3-OH DNA fragment ends in apoptotic cells. Based on morphology, astrocytic cells were excluded from counting. The percent of non-astrocytic cells that were TUNEL positive were determined from four randomly selected fields for the estimation of apoptosis. To verify apoptosis cells were stained with Hoechst 33258 and examined with a fluorescence microscope. Apoptotic cells were identified on the basis of changes in nuclear morphology, such as chromatin condensation and fragmentation.

Subcellular fractionation

After different treatments, cortical cells were harvested in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 500 g (Shou et al., 2003). Cell pellets were resuspended in isotonic mitochondrial buffer (MB: 210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5), supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, CA, USA) and homogenized with a polytron homogenizer. Samples were centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min at 4ºC and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4ºC to obtain the heavy membrane pellet (HM) enriched for mitochondria. The 10,000 g supernatant was used as crude cytosol and the HM pellet resuspended in 50 μl MB buffer.

To assess whether BNIP3 integrates into mitochondrial membranes, the mitochondrial fractions were subjected to alkali extraction using freshly prepared 0.01 MNa2CO3 (pH 11.5) to dissociate and solubilize proteins that are not integrated into the membrane (Goping et al., 1998).

Whole cell extraction

Control and cyanide-treated cells were prepared by washing the cells three times with PBS and harvested by centrifugation at 500×g for 5 min. Cell pellets were lysed in a buffer containing 220 mM mannitol, 68 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% Triton-X100 and protease inhibitors on ice for 15 min. After centrifugation, supernatants were taken as whole cell protein extraction.

Western blot analysis

Western analysis was performed according to the protocol supplied with the ECF Western blot kit (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The protein content in the extractions was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The samples containing 30–50 μg protein were boiled in Laemmli buffer for 5 min and subjected to electrophoresis in 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, followed by transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with PBS containing 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20, the membrane was exposed to primary antibody for 3 h at room temperature on a shaker. Reactions were detected with a fluorescein-linked anti-mouse IgG (second antibody) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase using enhanced chemiluminescence. Primary antibodies used were mouse monoclonal anti-BNIP3 antibody, mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-cytochrome c antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and bovine monoclonal anti-cytochrome oxidase subunit IV antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Immunocytochemistry

Cortical neurons were grown on poly-L-lysine coated coverslips and after treatment, cells were labeled with 500 nM Mitotracker (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 30 min at 37ºC. After washing three times with PBS, cells were fixed for 15 min with 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature. Cultures were then washed with PBS and exposed to blocking solution (5% goat serum in PBS). After PBS washing, cells were incubated with monoclonal anti-BNIP3 antibody (1:200 diluted in PBS) at room temperature for 3 h. Cells were washed twice in PBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjucated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Coverslips were then mounted onto glass slides and images were acquired and analyzed using a BioRad MRC 1024ES laser scanning confocal microscope (Hercules, CA, USA).

Caspase activity

The generation of 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) from the caspase tetrapeptide substrate DEVD-AMC (Bachem Bioscience, King of Prussia, PA, USA) was used as an index of caspase 3 and 7 activity (See and Loeffler, 2001). Briefly, cells grown in 6 well culture dishes were washed with PBS and lysed with 100 μl of lysis buffer [0.05% Igepal NP-40 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5] on ice. 50 μl of lysate were added to a reaction mixture containing 100 μl of 2 X reaction buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol), 40 μl of H2O, and 10 μl of DEVD-AMC (final concentration 50 μM) and incubated for 1 h at 37ºC. The reaction was stopped by a 10 X dilution with ice-cold lysis buffer. Fluorescence of free AMC was measured (excitation and emission wavelengths: 360 and 465 nm, respectively) using a plate reader.

Mitochondrial membrane potential

The relative Δψm was monitored with rhodamine 123 (R123) as previously described(Prabhakaran et al., 2002). After treatment, cells were loaded with 10 μM R123 and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. Uptake of R123 into mitochondria is a direct reflection of its permeability; an increase of R123 fluorescence reflects a lowering of Δψm. Loaded cells were washed twice with Krebs-Ringer buffer, and changes in R123 fluorescence were monitored using a fluorescence plate reader at 498 nm excitation and 525 nm emission.

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM and statistical significance was assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey-Kramer multiple range test. Differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Cyanide-induced apoptosis correlates with increased BNIP3 expression

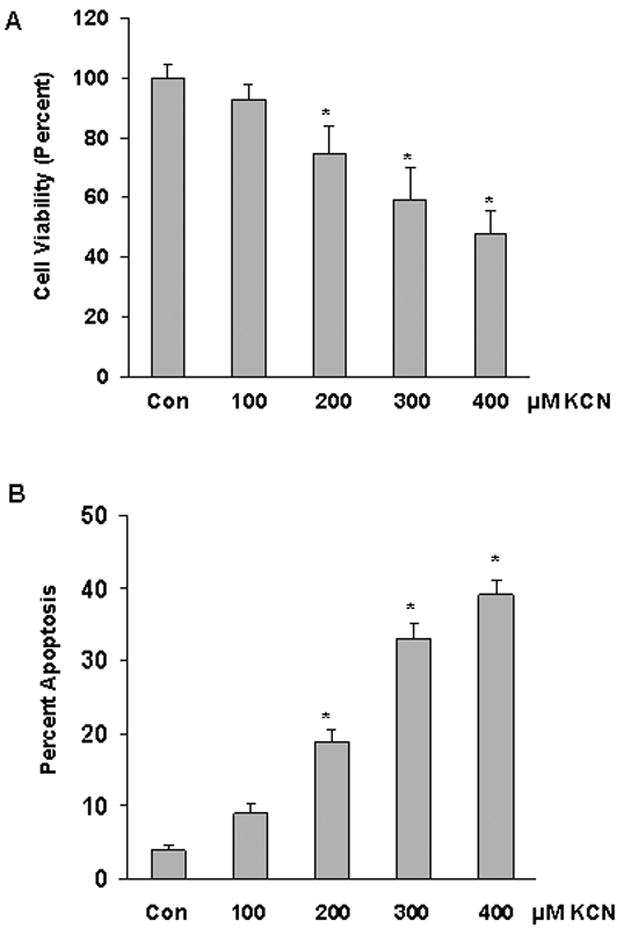

A concentration-dependent decrease in cell viability was detected in cortical cells exposed to 100–400 μM KCN (Figure 1A). As determined by TUNEL assay, the mode of death was predominantly apoptotic, consistent with previous studies on cyanide-induced death in primary cortical cells (Figure 1B) (Li et al., 2002; Prabhakaran et al., 2002). Apoptosis was confirmed by cell staining with Hoechst 33258 to visualize nuclear changes (data not shown). It should be noted that in these studies mixed cultures or cell composed of neurons and astrocytes were used and the contribution of astrocytes to the cytotoxic response was minimal. We have observed that astrocytic cells are resistant to the cytotoxic action of cyanide and at the concentrations used, minimal astrocytic cell damage or death was detectable. On the other hand, pure neuronal cultures (grown in serume free neurobasal-B27 medium yielding >95% neurons) were very sensitive to cyanide (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Cyanide-induced cell death in cortical cells. Cells were exposed to cyanide (100–400 μM) for 24 h and cell death quantitated. A) Cell viability determined by MTT assay. B) Apoptotic death determined by TUNEL assay. Data represents mean ±SE of three or more experiments. *Significantly difference from control (P<0.05).

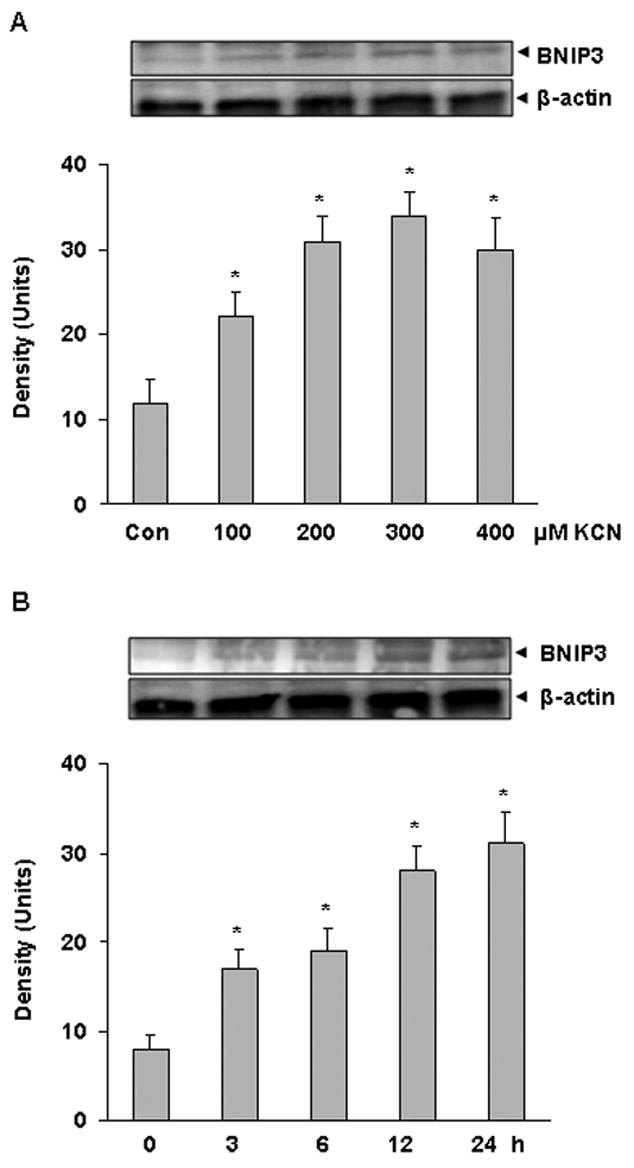

To establish whether cyanide could alter BNIP3 expression, cells were exposed to KCN (100–400 μM) for 20 h and expression analyzed by Western blotting. Cyanide induced a concentration- and time- dependent increase of BNIP3 expression (Figure 2), paralleling the cell death response. BNIP3 was expressed at a low level under control conditions, whereas cyanide rapidly increased expression with enhanced levels noted within 3 h and continued to increase over the 24 h observation period.

Figure 2.

Cyanide-induced expression of BNIP3 in cortical cells. A) Western blot analysis of cells treated with KCN (100–400 μM) for 20 h. B) Western blot of cells treated with KCN (400 μM) for 3–24 h. Densitometric analysis was by Scion Image software. *Significantly difference from control (P<0.05).

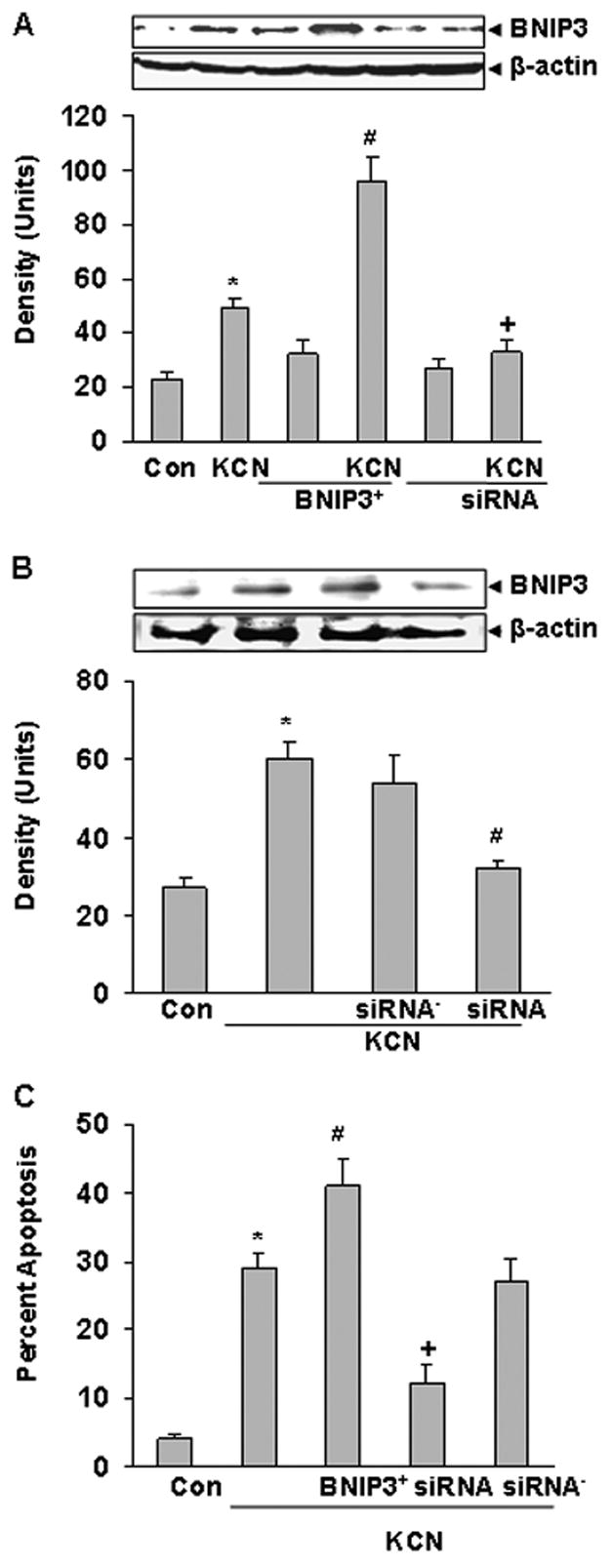

Altered BNIP3 expression modulates cyanide-induced apoptosis

To link BNIP3 to apoptosis, cells were transiently transfected with BNIP3 cDNA(BNIP3+) for forced overexpression or siRNA (RNAi) to knockdown BNIP3 (Vande Velde et al., 2000; Kubasiak et al., 2002), and then 24 h later treated with cyanide (400 μM). In BNIP3+ cells cyanide produced a marked up-regulation of BNIP3 expression that was accompanied by an increased apoptotic death (Figure 3A,C). RNAi blocked the KCN-induced up-regulation of BNIP3 and reduced cell death to control levels. Interestingly constitutive expression of BNIP3 did not change after transfection with RNAi, suggesting a low turnover rate and/or a very low basal expression of BNIP3 in the wild type cells. To confirm that RNAi selectively knocked down BNIP3, transfection with a negative control RNAi did not alter either BNIP3 expression or the level of cell death induced by cyanide (Figure 3B,C). It was concluded that the RNAi sequences were specific for BNIP3.

Figure 3.

Effect of transfection on BNIP3 expresssion and apoptosis. A) Cells were transfected with BNIP3 expression plasmid or BNIP3 siRNA (knockdown) and 24 h later treated with KCN (400 μM) for 12 h. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with an anti-BNIP3 antibody. B) Cells were transfected with BNIP3 siRNA or BNIP3 siRNA− (negative control) prior to Western analysis. Densitometric analysis was by Scion Image software. C) Percent apoptotic (TUNEL positive) cells were determined after 24 h of KCN exposure in tranfected cells. Data represents mean ± SE of three or more experiments. *Significantly difference from control; #significantly different from KCN; +significant different from KCN alone and BNIP3+ + KCN group, (P<0.05).

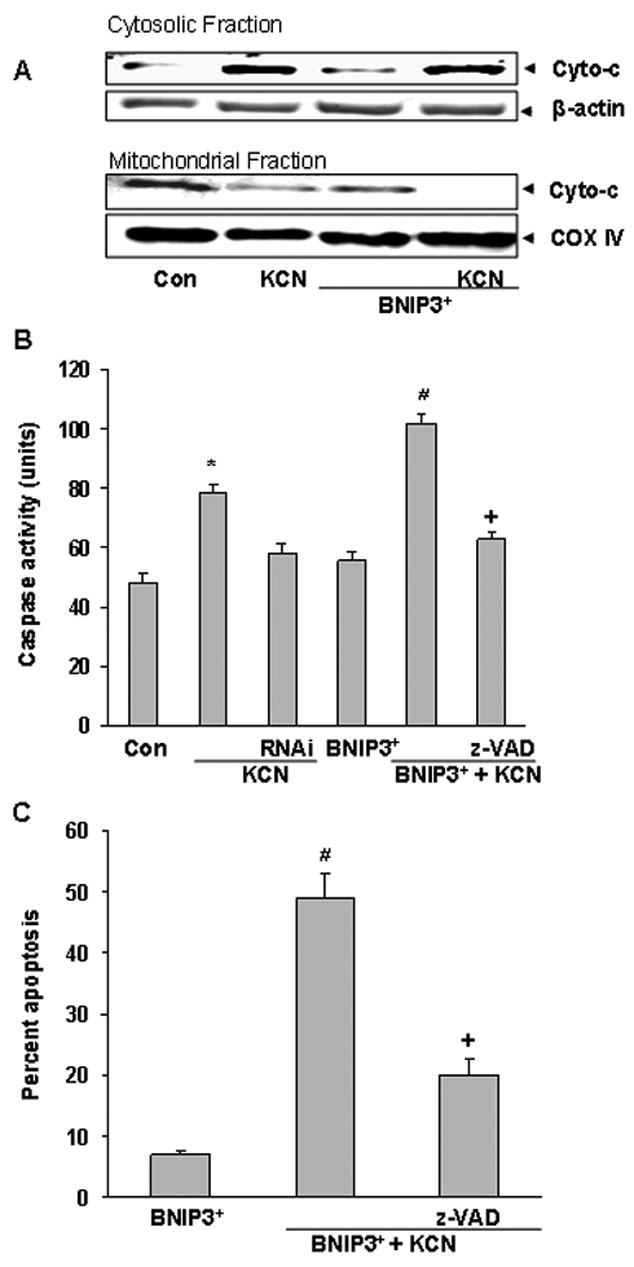

BNIP3 upregulation produces cytochrome c release and caspase activation

Release of the mitochondrial protein, cytochrome c, into the cytosol regulates apoptotic death by promoting caspase activation, followed by execution of apoptosis (Li et al, 1997). To determine whether BNIP3 overexpression stimulates cytochrome c release from mitochondria, expression of BNIP3 was increased by tranfection (BNIP3+) and subcellular distribution of cytochrome c examined. Cyanide released cytochrome c into the cytosol in both BNIP3+ and wildtype cells (Figure 4A). To determine if the cell death was caspase-dependent, expression of BNIP3 was altered by tranfection (BNIP3+ or RNAi) and caspase activity determined following cyanide. In BNIP3+ cells, cyanide increased caspase 3 and 7 activity and zVAD-fmk significantly reduced cell death (Figure 4C), thus linking caspase activity and apoptosis in BNIP3+ cells. Also, RNAi knock down of BNIP3 decreased cyanide-induced caspase activation in wildtype cells, in parallel with the reduction of apoptosis (Figure 4B,C). zVAD-fmk blocked both the increase of caspase 3 and 7 activity and apoptotic death, establishing that the cyanide-induced apoptosis was caspase-dependent.

Figure 4.

Expression of BNIP3 promotes cytochrome c release, caspase activation and apoptosis. Cells were transfected with BNIP3 expression plasmid or BNIP3 siRNA for 24 h and then treated with KCN (400 μM). A) Six h after KCN, mitochondrial and cytosolic extracts were subjected to Western blotting with an anti-cytochrome c antibody. B) Transfected cells were pre-treated with z-VAD-fmk for 1 h before addition of KCN (400 μM) for 6 h, followed by determination of caspase activity. C) Percent apoptotic (TUNEL positive) cells following 24 h of KCN exposure. Data represent mean ± SE of three or more experiments. *Significantly different from control; #significantly different from KCN; +significantly different from BNIP3+ + KCN group, (P<0.05).

BNIP3-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death

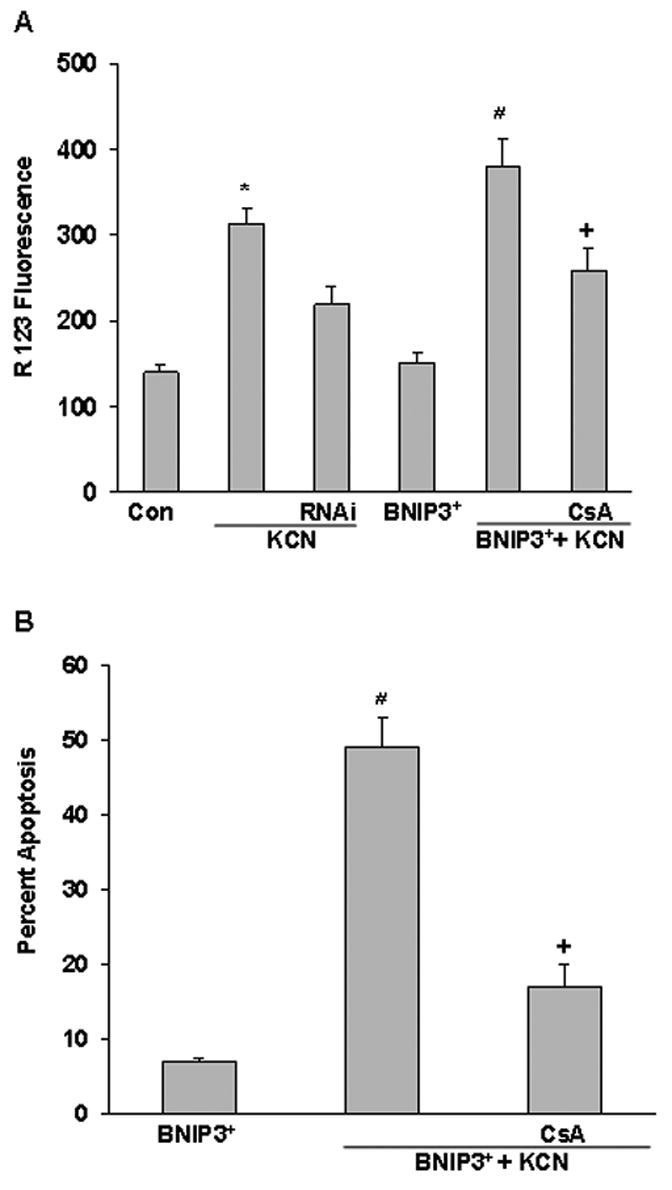

To determine the effect of BNIP3 expression on mitochondrial function, cells were transfected with BNIP3 or RNAi prior to cyanide and then the relative Δψm was monitored using rhodamine-123. Cyanide significantly reduced Δψm as reflected by increased R-123 fluorescence and the reduction was enhanced in BNIP3+ cells (Figure 5A). On the other hand the KCN-induced reduction of Δψm was blocked by RNAi knockdown of BNIP3. Pretreatment with CsA (MPT pore inhibitor) blocked the cyanide-induced reduction in Δψm and apoptotic death in BNIP3+ cells (Figure 5A,B). These observations establish an association between cyanide-induced apoptosis and BNIP3-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction.

Figure 5.

Effect of BNIP3 on ΔΨm and apoptosis. A) Cells were transfected with a BNIP3+ plasmid or BNIP3 siRNA for 24 h and then treated with CsA for 1 h before addition of KCN (400 μM). Two h later the ΔΨm was monitored by the R123 method. B) Percent apoptotic (TUNEL positive) cells was determined 24 h after treatments. Data represent mean ± SE of six or more experiments. *Significantly different from control; # significantly different from KCN; +significantly different from BNIP3+ + KCN group, (P<0.05).

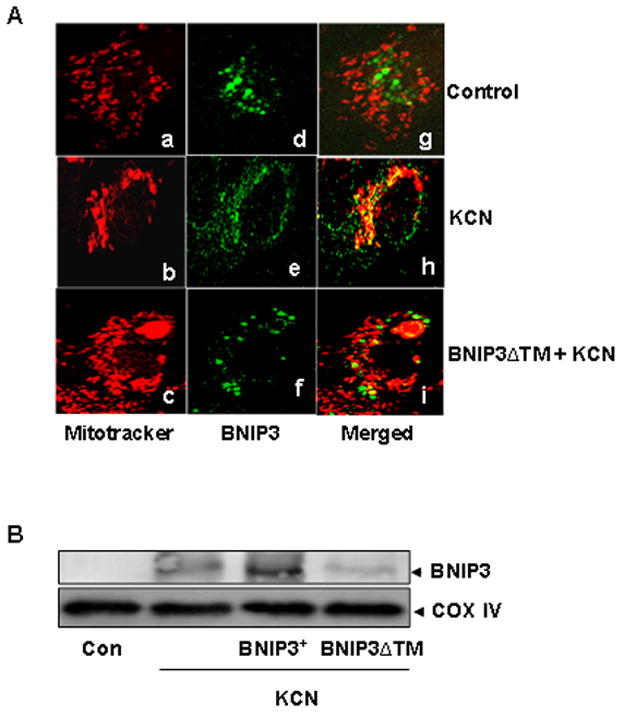

Cyanide stimulates translocation and integration of BNIP3 into mitochondria

The initial step in BNIP3-mediated cell death is translocation of the protein to mitochondria, followed by insertion into the outer membrane (Chen et al., 1997). To determine if cyanide stimulated BNIP3 translocation, confocal imaging of BNIP3 was conducted by use of a fluoresence labeled anti-BNIP3 antibody and mitochondria were imaged with Mitotracker Red. In KCN treated cells, BNIP3 was localized to mitochondria, whereas in wildtype control cells the protein remained localized in the cytosolic compartment (Figure 6A). Integration of BNIP3 into the outer mitochondrial membrane was determined by Western blot analysis of isolated mitochondria from control and cyanide treated cells. Isolated mitochondria were subjected to alkali extraction to dissociate and solubilize loosely associated membrane proteins (Goping et al., 1998). Western blots of alkali extracted mitochondria showed that BNIP3 was readily stripped from mitochondrial membranes of control wildtype cells, whereas BNIP3 remained at high levels in the mitochondrial fraction of cyanide treated cells, showing that the protein had integrated into mitochondrial membranes after exposure to cyanide (figure 6B). Transfection with a carboxyl terminal transmembrane deletion mutant of BNIP3 (BNIP3ΔTM) blocked insertion of BNIP3.

Figure 6.

Cyanide-induced mitochondrial translocation and membrane integration of BNIP3. A) Immunofluorescence imaging of the subcellular distribution of BNIP3. After transfection and KCN treatment for 12 h, cells were exposed to a fluorescent labeled anti-BNIP3 antibody (green) and with Mitotracker red which localizes in mitochondria. Confocal microscopy illustrates localization of mitochondria (a–c) and BNIP3 (d–f). Co-localization of BNIP3 and mitochondria is shown as yellow in merged images (g–i). B) Alkali extracts of mitochondria from control and treated cells were subjected to Western blotting with an anti-BNIP3 antibody.

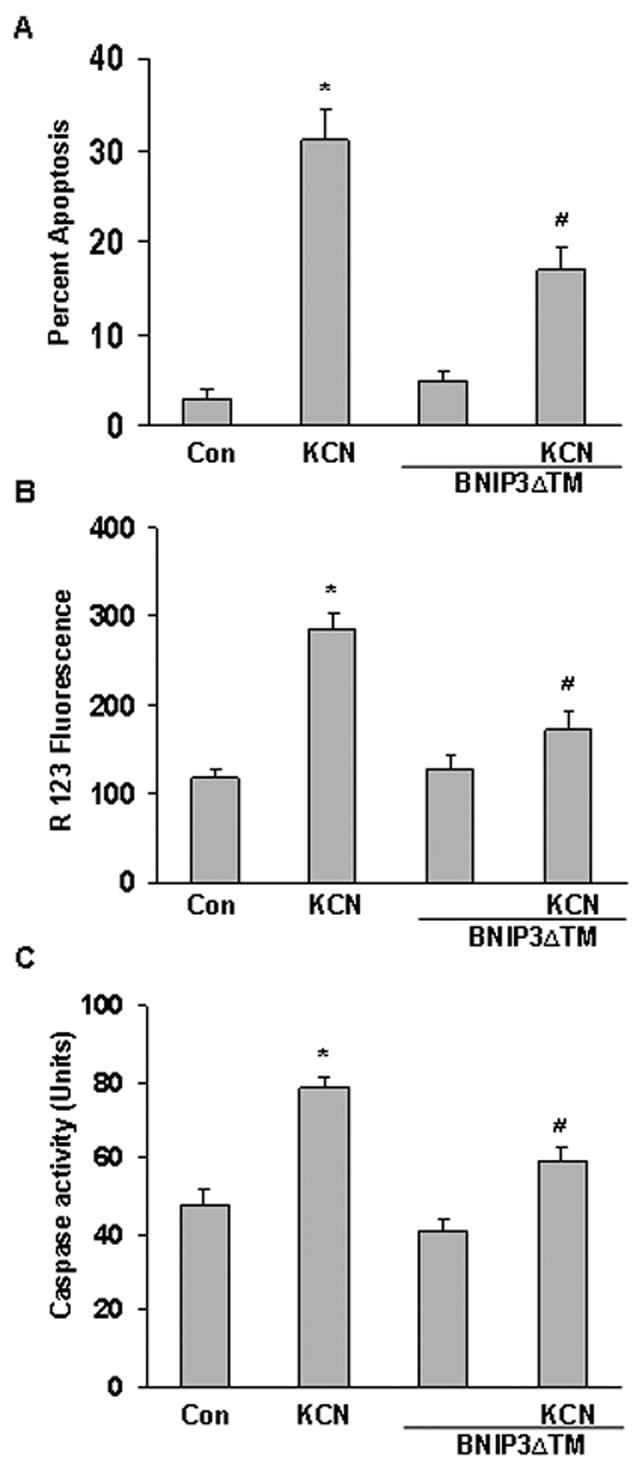

To demonstrate that integration of BNIP3 into mitochondrial membrane is necessary for cell death, cytotoxicity was assessed in BNIP3ΔTM+ cells. Cyanide-induced cell death was significantly reduced in BNIP3ΔTM+ cells as compared to wild type cells treated with KCN (Figure 7A). The magnitude of the reduction of cell death was comparable to that produced by RNAi (Figure 3C). BNIP3ΔTM+ also blocked the KCN-induced caspase activation and dissipation of Δ ψm (Figure 7B,C). Western blot analysis showed that the mutant blocked mitochondrial release of cytochrome c (data not shown). As compared to control cells, BNIP3ΔTM+ did not produce mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death, thus it was apparent that the mutant was not toxic under control conditions. It was concluded that in primary cortical cells, BNIP3ΔTM reduces cyanide cytotoxicity by a dominant negative antagonism of BNIP3 translocation and insertion into mitochondrial outer membrane.

Figure 7.

Expression of BNIP3 TM reduces KCN-induced cytotoxicity. Cells were transfected with BNIP3 TM for 24 h before cyanide treatment. A) Percent apoptotic (TUNEL positive) cells. B) ΔΨm was monitored by the R123 fluorescence method. C) Caspase activity was determined in cellular lysates following the specific treatments. Data represent mean ± SEM of six or more experiments. *Significantly different from control; #significantly different from KCN, (P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

BNIP3 is a unique pro-death factor that is a member of the BH3-only subfamily of Bcl-2 proteins that regulates cell death. BNIP3 lacks the BH1 and BH2 domains characteristic of the Bcl-2 family, but has a common BH3 interaction domain (Chen et al., 1997; Webster et al., 2005). BNIP3 expression is regulated transcriptionally and when induced, protein levels rise rapidly, followed by translocation to mitochondria and insertion of the C-terminal domain into the outer mitochondrial membrane (Kubasiak et al., 2002). The mode of cell death initiated by BNIP3 is stimulus and cell type specific. In a number of cell models a caspase-dependent apoptosis has been reported, whereas a caspase-independent necrosis-like death has been observed following hypoxia (Vande Velde et al., 2000; Kubasiak et al., 2002).

In the present study, it was shown in primary cortical cells that cyanide-induced a caspase dependent, apoptotic death linked to induction of BNIP3 expression. The apoptotic cell death was mediated by mitochondrial release of cytochrome c which then activated the caspase apoptotic death cascade. Knockdown studies with BNIP3 RNAi demonstrated that up-regulation of BNIP3 was directly linked with apoptosis. Also, forced overexpression of BNIP3 sensitized the cells to cyanide. After up-regulation, BNIP3 translocated from the cytosol and integrated into the mitochondrial outer membrane to induce MPT pore opening. Temporally this was followed by dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane proton electrochemical gradient and release of cytochrome c to initiate caspase activation, the execution step of the cell death.

The mechanism by which BNIP3 initiates mitochondria-mediated cell death is not clear and may be different from the typical cell death cascade mediated by the Bcl-2 family. Following insertion into the outer membrane, BNIP3 can heterodimerize with Bcl-2 and Bcl-X(L) to neutralize their anti-apoptotic properties to initiate cell death (Goping et al., 1998). This mode of death is caspase-dependent and mediated by secretion of cytochrome c from mitochondria. Additionally, BNIP3 can produce rapid mitochondrial dysfunction by directly interacting with VDAC/porin and ANT to stimulate opening of the MPT pore, thereby dissipating Δψm (Shimizu et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2003). The rapid loss of Δψm can lead to ATP depletion, calcium ion imbalance and eventually loss of plasma membrane intregrity to produce a necrosis-like morphology. Similarly, cyanide induced a rapid loss of mitochondrial function as reflected by the loss of Δψm. This is accompanied by a catastrophic decrease of cellular ATP, elevation of cytosolic calcium and then execution of cell death (Sun et al., 1997; Prabhakaran et al., 2005)

In the nervous system, BNIP3 expression is normally not detectable or expressed at low levels. However the protein may play a role in brain cell death under select conditions. Following global brain ischemia, expression is rapidly induced in CA1 neurons and undergoes nuclear localization, suggesting a novel role in regulating cell death (Schmidt-Kastner et al., 2004). A recent study indicates that BNIP3 may be a mediator of brain developmental apoptosis (Sandau et al., 2006). In situ hybridization analysis of BNIP3 mRNA showed that a transient increase in mRNA expression correlated with developmental cell death in neonatal rat cortex and hippocampus. Involvement of BNIP3 in cyanides action on the nervous system is of interest since exposure can produce a unique region-specific neurodegeneration (Mills et al., 1999). Cyanide produces a pattern of cell death in the brain in which the mesencephalic areas undergo a necrotic death, whereas in the cortex apoptosis has been observed (Prabhakaran et al., 2002). Based on the present study, it is concluded that BNIP3 induction and translocation to mitochondria plays a role in the cortical apoptosis, whereas a different cell signaling system or execution cascade may be activated in mesencephalic necrosis.

The mode of cortical cell death observed with cyanide is similar to that produced by hypoxia, however the initiation signal may be different (Tanaka et al., 1994; Halterman and Federoff, 1999). Cell hypoxia increases BNIP3 expression by activating hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α), thus stimulating BNIP3 gene transcription by binding to the hypoxia-response element (HRE) present in the BNIP3 promoter. In hypoxia, low cellular oxygen directly stimulates an increased HIF-1α activity and its DNA binding to increase BNIP3 transcription (Guo et al., 2001). On the other hand, cyanide induces histotoxic anoxia in which cellular concentration of oxygen is normal, only oxygen utilization in oxidative phosphorylation is inhibited (Way, 1984), thus the initiation pathway for BNIP3 induction in cyanide-induced apoptosis may be independent of the normal HIF-1α pathway. Other studies have shown that BNIP3 induction can be activated by non-hypoxia pathways by activating HIF-1α signaling by non-oxygen mediated pathways involving kinase signaling pathways perhaps stimulated by oxidative stress (Yook et al., 2004; Kanzawa et al., 2005; An et al., 2006). The intense oxidative stress produced by cyanide as a result of complex IV inhibition may be the BNIP3 activation stimulus (Jones et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2003).

In order for BNIP3 to initiate mitochondrial dysfunction, the protein must be integrated into the outer mitochondrial membrane (Chen et al., 1999; Ray et al., 2002). It was observed that under basal conditions (controls) BNIP3 was loosely associated with mitochondria, but following addition of cyanide the protein could not be stripped from the mitochondrial surface by alkali treatment. This “tight” binding or integration into the membrane apparently may have led to an intra-membrane interaction necessary for initiation of mitochondrial dysfunction. This is supported by the observation that expression of BNIP3ΔTM, a mutant lacking the transmembrane insertion domain, blocked BNIP3 translocation and integration into the mitochondrial outer membrane to block apoptosis. Previous studies have shown that BNIP3ΔTM functions as a dominant negative mutant that blocks translocation to mitochondria (Kubasiak et al., 2002; Regula et al., 2002). These observations provide evidence that in cortical cells, cyanide induces a mitochondria-mediated apoptosis by up-regulating BNIP3 and stimulating its translocation.

In summary, cyanide produces an apoptotic cell death in primary cortical cells by a BNIP3 inducible pathway. This potent neurotoxin rapidly stimulates up-regulation of BNIP3 expression which in turn translocates to the mitochondrial outer membrane, followed by mitochondrial dysfunction, release of cytochrome c and then execution of a caspase dependent apoptosis. It is likely that a unique initiation signal is stimulated by cyanide since cellular oxygen levels are not altered by the histotoxic anoxia.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant ES04140.

Abbreviations

- AMC

7-amino-4-methylcoumarin

- BNIP3

Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein 3

- BNIP3ΔTM

BNIP3 protein with deletion of transmembrane domain

- BH3

Bcl-2 homology domain 3

- CsA

cyclosporin A

- Δ ψm

mitochondrial membrane potential

- DEVD-AMC

caspase tetrapeptide substrate

- HIF-1α

hypoxiainducible factor 1 alpha

- HM

heavy membrane pellet

- MTP

mitochondrial transition pore

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

- R123

rhodamine 123

- siRNA (RNAi)

small interfering RNA

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling

- zVAD-fmk

N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Ala-Asp-fluoromethyl ketone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- An HJ, Maeng O, Kang KH, Lee JO, Kim YS, Paik SG, Lee H. Activation of Ras up-regulates pro-apoptotic BNIP3 in nitric oxide-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33939–33948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GR, Ray R, Dubik D, Shi LF, Cizeau J, Bleakley RC, Saxena S, Gietz RD, Greenberg AH. The E1B 19K Bcl-2 binding protein Nip3 is a dimeric mitochondrial protein that activates apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1975–1983. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GR, Cizeau J, Vande Velde C, Park JH, Bozek G, Bolton J, Shi L, Dubik D, Greenberg A. Nix and Nip3 form a subfamily of pro-apoptotic mitochondrial proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: Central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36027–36031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow MT. Hypoxia, BNip3 proteins, and the mitochondrial death pathway in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:183–185. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000030195.38795.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goping IS, Gross A, Lavoie JN, Nguyen M, Jemmerson R, Roth K, Korsmeyer SJ, Shore GC. Regulated targeting of BAX to mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:207–215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham RM, Frazier DP, Thompson JW, Haliko S, Li H, Wasserlauf BJ, Spiga MG, Bishopric NH. A unique pathway of cardiac myocyte death caused by hypoxia-acidosis. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:3189–3200. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K, Searfos G, Krolikowski DY, Pagnoni M, Franks C, Clark K, Yu KT, Jaye M, Ivashchenko Y. Hypoxia induces the expression of the pro-apoptotic gene BNIP3. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:367–376. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halterman NW, Federoff HJ. HIP-1α and p53 promote hypoxia-induced delayed neuronal death in models of CNS ischemia. Exp Neurol. 1999;159:65–72. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Itoh A, Pleasure D. Bcl-2 related protein family gene expression during oligodendroglial differentiation. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1500–1521. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DC, Prabhakaran K, Li L, Gunasekar PG, Shou Y, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. Cyanide enhancement of dopamine-induced apoptosis in mesencephalic cells involves mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Neurotoxicol. 2003;24:333–342. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzawa T, Zhang L, Xiao L, Germano IM, Kondo Y, Kondo S. Arsenic trioxide induces autophagic cell death in malignant glioma cells by upregulation of mitochondrial cell death protein BNIP3. Oncogene. 2005;24:980–991. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YC, Shim JW, Oh YJ, Son H, Lee YS, Lee SH. Co-transfection with cDNA encoding the Bcl family of anti-apoptotic proteins improves the efficiency of transfection in primary fetal neural stem cells. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;117:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa M, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy AG. Dieldrin-induced oxidative stress and neurochemical changes contribute to apoptotic cell death in dopaminergic cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1473–1485. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky AM, Kosik K. RNAi functions in cultured mammalian neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:11926–11929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182272699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubasiak LA, Hernandez OM, Bishopric NH, Webster KA. Hypoxia and acidosis activate cardiac myocyte death through the Bcl-2 family protein BNip3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12825–12830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202474099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Paik SG. Regulation of BNIP3 in normal and cancer cells. Mol Cells. 2006;2:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Srinivasan A, Wang Y, Armstrong RC, Tomaselli KJ, Fritz LC. Cell specific induction of apoptosis by microinjection of cytochrome c. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30299–30305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Prabhakaran K, Shou Y, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. Oxidative stress and cyclooxygenase-2 induction mediate cyanide-induced apoptosis of cortical cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2002;185:55–63. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills EM, Gunasekar PG, Li L, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. Differential susceptibility of brain areas to cyanide involves different modes of cell death. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;156:6–16. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran K, Li L, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. Cyanide induces different modes of death in cortical and mesencephalic cells. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 2002;303:510–519. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.039453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran K, Li L, Mills EM, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. Upregulation of uncoupling protein 2 by cyanide is linked with cytotoxicity in mesencephalic cells. J Pharmacol Expl Therap. 2005;314:1338–1345. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Chen G, Vande Velde C, Cizeau J, Park JH, Reed JC, Gietz RD, Greenberg AH. BNIP3 heterodimerizes with Bcl-2/BclXL and induces cell death independent of a Bcl-2 homology3 (BH3) domain at both mitochondrial and nonmitochondrial sites. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1439–1448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regula KM, Ens K, Krishenbaum LA. Inducible expression of BNIP3 provokes mitochondrial defects and hypoxia mediated cell death of ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:226–231. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000029232.42227.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandau US, Handa J. Localization and developmental ontogeny of the pro-apoptotic Bnip3 mRNA in the postnatal rat cortex and hippocampus. Brain Res. 2006;1100:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Kastner R, Aguirre-Chen C, Kietzmann T, Saul I, Busto R, Ginsberg MD. Nuclear localization of the hypoxia-regulated pro-apoptotic protein BNIP3 after global brain ischemia in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2004;1001:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See V, Loeffler JP. Oxidative stress induces neuronal death by recruiting a protease and phosphatase-gated mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35049–35059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S, Konishi A, Kodama T, Tsujimoto Y. BH4 domain of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members closes voltage-dependent anion channel and inhibits apoptotic mitochondrial changes and cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3100–3105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou Y, Gunasekar PG, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. Cyanide-induced apoptosis involves oxidative-stress-activated NF-kappaB in cortical neurons. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;164:196–205. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.8900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou Y, Li N, Li L, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. NF-kappaB-mediated up-regulation of Bcl-X(S) and Bax contributes to cytochrome c release in cyanide-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2002;81:842–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou Y, Li L, Prabhakaran K, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates Bax translocation in cyanide-induced apoptosis. Toxicol Sci. 2003;75:99–107. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Rane SG, Gunasekar PG, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. Modulation of the NMDA receptor by cyanide: Enhancement of receptor mediated responses. J Pharmacol Expl Therap. 1997;280:1341–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Ito H, Adachi S, Akimoto H, Nishikawa T, Kasjima T, Marumo F, Hiroe M. Hypoxia induces apoptosis with enhanced expression of Fas antigen messenger RNA in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Cir Res. 1994;75:426–433. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Velde C, Cizeau J, Dubik D, Alimonti J, Brown T, Israels S, Hakem R, Greenberg AH. BNIP3 and genetic control of necrosis-like cell death through the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5454–5468. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5454-5468.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way JL. Cyanide intoxication and its mechanism of antagonism. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1984;24:451–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.24.040184.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster KA, Graham RM, Bishopric NH. BNip3 and signal-specific programmed death in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Yun H, Yang Y, Jing B, Feng C, Song-bin F. Upregulation of BNIP3 promotes apoptosis of lung cancer cells that were induced by p53. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yook YH, Kang KW, Maeng O. Nitric oxide induces BNIP3 expression that causes cell death in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HM, Cheung P, Yanagawa B, McManus BM, Yang DC. BNips: A group of pro-apoptotic proteins in the Bcl-2 family. Apoptosis. 2003;8:229–236. doi: 10.1023/a:1023616620970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]