Abstract

Somatic hypermutation (SHM) and class switch recombination (CSR) of immunoglobulin (Ig) genes require the cytosine deaminase AID, which deaminates cytosine to uracil in Ig gene DNA. Paradoxically, proteins involved normally in error-free base excision repair and mismatch repair, seem to be co-opted to facilitate SHM and CSR, by recruiting error-prone translesion polymerases to DNA sequences containing deoxy-uracils created by AID. Major evidence supports at least one mechanism whereby the uracil glycosylase Ung removes AID-generated uracils creating abasic sites which may be used either as uninformative templates for DNA synthesis, or processed to nicks and gaps that prime error-prone DNA synthesis. We investigated the possibility that deamination at adenines also initiates SHM. Adenosine deamination would generate hypoxanthine (Hx), a substrate for the alkyladenine DNA glycosylase (Aag). Aag would generate abasic sites which then are subject to error-prone repair as above for AID-deaminated cytosine processed by Ung. If the action of an adenosine deaminase followed by Aag were responsible for significant numbers of mutations at A, we would find a preponderance of A:T > G:C transition mutations during SHM in an Aag deleted background. However, this was not observed and we found that the frequencies of SHM and CSR were not significantly altered in Aag-/- mice. Paradoxically, we found that Aag is expressed in B lymphocytes undergoing SHM and CSR and that its activity is upregulated in activated B cells. Moreover, we did find a statistically significant, albeit low increase of T:A > C:G transition mutations in Aag-/- animals, suggesting that Aag may be involved in creating the SHM A>T bias seen in wild type mice.

1. Introduction

Somatic hypermutation (SHM) in mammals is a process of secondary diversification of immunoglobulin (Ig) genes in activated B cells during which point mutations, and occasional insertions and deletions, are introduced into DNA encoding the antibody variable (V) regions. SHM thereby alters the affinity of antibodies for cognate antigens, a hallmark of adaptive immunity. SHM requires AID, the most likely function of which is to deaminate cytosines in the promoter proximal region DNA of Ig genes (reviewed in [1]). Deamination of cytosine (C) in DNA creates a uracil (U) base mispaired with guanine (G) that, when present in DNA, is a substrate for DNA repair. During SHM, some of the DNA repair systems that would normally faithfully repair such U:G mismatches paradoxically appear to be co-opted to generate mutations. Proteins of two major systems co-opted for SHM are the uracil glycosylase Ung, and the mismatch repair proteins Msh2, Msh6 (which comprise the Msh2/6 heterodimer), Mlh1, Pms2 (reviewed in [1,2]) and Mlh3 [3,4].

Mice and humans deficient for Ung are proficient for SHM, but the pattern of SHM is altered characteristically in that mutations at C and G are mainly transitions, as if uracils left unrepaired serve as a template for DNA replication [5,6]. As a glycosylase, the function of Ung is to remove U from the DNA backbone, leaving an abasic (AP) site that is processed by concerted action of an AP endonuclease (APE1), and a deoxyribophosphodiesterase (dRPase activity of polymerase (pol) β to produce a single-strand gap [2]. Error-free filling-in of the gap is accomplished by pol β or the high-fidelity polymerase, δ [7]. However, to explain the SHM pattern shift due to Ung-deficiency, AID/Ung-mediated single-strand gaps are likely to be filled-in using one or more translesion polymerases to generate mutations from all four nucleotides. Of the many recently identified translesion polymerases, particularly polymerase, η, ι and θ have been implicated in SHM (reviewed by [8]).

Importantly, Ung-deficiency affects the SHM pattern at C (and G), but has less effect on mutations at A (and T). Mutations at A are at most 52% reduced in Ung-deficient mice [9], presumably, because Ung-dependent mutations at A can arise during long-patch base excision repair (BER) in which polymerases β or δ are replaced by translesion polymerases. In the absence of Ung, these mutations in part seem to depend on functional mismatch recognition by Msh2/6, because, although the pattern of mutations at A is not altered, their frequency is decreased from ~50% in wildtype mice to between 26% and as little as 2% of total mutations in both Msh2-/- and Msh6-/- mice (reviewed in [1,10]). This decrease in frequency suggests that recognition of the U:G mismatch by MutSα (the Msh2/6 heterodimer) inititates a process that ultimately leads to mutations at adenines, perhaps via recruitment of the error-prone pol η [11,12]. Polη deficiency in mice and humans also leads to a SHM pattern characterized by a low frequency of mutations at A [12-16].

Currently available data suggest that mutations at A can be explained by the activities of Ung and mismatch repair, and errors created by translesion DNA polymerases. However, the precise mechanism by which these mutations arise are not yet known and possibly there are unknown factors that are involved in DNA repair during SHM that could influence mutations at A. Like mutations at C, transition mutations at A are predominant in SHM. A:T -> G:C transitions could result from deamination of A to hypoxanthine (Hx), which codes as a G during DNA synthesis [17,18]. Adenosine deaminases exist, although currently are known to act only on RNA [19]. Yet, by analogy to AID, we questioned whether a DNA adenosine deaminase might be involved in SHM. The major DNA repair enzyme for Hx is alkyladenine DNA glycosylase (Aag) [20]. In order to determine whether adenosine deamination plays a role during SHM we examined the SHM pattern in Aag-/- mice. We report here that, while the mutational pattern at A is not changed in the Aag-deficient animal, activation of B cells leads to a significant induction of Hx glycosylase activity in wild type mice. Furthermore, we see a small yet significant bias towards T:A -> C:G transition mutations in the absence of Aag leading us to suggest that Aag glycosylase activity plays a role during SHM.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Aag-/- mice

The generation of the Aag-/- mice was previously described [20]. Aag-/- animals were backcrossed to a pure C57Bl/6J background (at least 12 backcrosses) and were 6 to 8 months old when received at the University of Chicago. Mice were analyzed soon after arrival, due to quarantine space constraints and institutional animal shipment regulations. Mice were genotyped as described [20]; genomic template DNA for PCR was derived from either PNA-low, sorted B cells from Peyer’s patches, or from kidney.

2.2 Ung-/- mice

Ung-/- mice were a gift of D. Barnes and T. Lindahl [21]. The original C57BL/6J-129SV background mice were maintained in our facility by breeding with C57BL/6J mice. Genotyping of these mice was as described [22].

2.3 Analysis of SHM in mice

(i) Cell isolation, staining and flow cytometry

Peyer’s patches were removed, strained, and rinsed twice with cold RPMI culture medium (Invitrogen) prior to staining with antibodies. Cells were stained with anti–mouse B220/CD45-PE (BD Biosciences), anti–mouse PNA-FITC (Sigma-Aldrich), and anti–mouse GL7-FITC (BD Biosciences) antibodies and sorted on a Mo-Flo or FACSAria (BD Biosciences) cell sorter at the Immunology Core Facility at the University of Chicago. PNA-low GL7-low B220+ (non-germinal center B cells) and PNA-high GL7+ B220+ (germinal center, mutating B cells) cells were collected for DNA extraction using DNeasy columns (QIAGEN). Mutations were analyzed in PNA-high B cells of Peyer’s patches. For investigating Aag and ADAR1 transcription in splenic cell subsets, spleen cells were additionally stained with anti-CD3 (APC-Cy7, BD Biosciences) and sorted as above. RNA was isolated from sorted cell populations using the RNAqueous-4PCR kit (Ambion).

(ii) PCR amplification and sequencing

VJ558-rearranged IgH genes were amplified as described previously [23,24] with the published primers, using ~10,000–20,000 cell equivalents of template DNA from germinal center B cells of Peyer’s patches, Pfu turbo polymerase (Stratagene), and PCR using 1 cycle at 95°C for 4 min, 95°C for 40 seconds, and 64–58°C for 40 seconds (touchdown annealing), 13 cycles at 72°C for 4 minutes, followed by 27 cycles at 95°C for 40 seconds, 57°C for 40 seconds, 72°C for 4 minutes, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes. J1, J2, J3, and J4 rearrangements were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, J4 bands were excised, and DNA was purified using a gel extraction kit (Qiaquick; QIAGEN). The actual J rearrangement was ultimately revealed by DNA sequencing. Only J4-rearranged sequences were analyzed. JCintronRseq (5’ CAGTTCTGAATAGGGTATGAGAGAGCC 3’), hybridizes to nucleotide +2,120 to +2,146 (relative to GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under accession #X53774) between the end of J4 and the 3’ primer used for PCR, which is complementary to nucleotide +2,429–2,458, located 3’ of the IgH intron enhancer [24]. JCintronRseq was used for sequencing.

PCR products were gel purified using the Qiaquick gel extraction kit and cloned using the Zero Blunt Topo PCR Cloning Kit (Invitrogen). Individual colonies were picked for automated DNA preparation and sequencing at the University of Chicago DNA Sequencing Core Facility.

iii) Mutation analyses

Mutations in a 585-basepair region downstream of J4 in J4-rearranged VHJ558 IgH genes were scored (between base pairs 1322-1906 according to numbering in GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession #X53774). Polymorphic base changes in the J4-C intron region (G/A-1566, G/A-1568, C/T-1650, C/T-1653, insertion/deletion of T-1687, A/G-1761, T/C-2047, A/G-2058, C/T-2086, C/A-2132, A/C-2173, where the base following the / is probably the C57BL/6J allele) were excluded. For mutation pattern analysis, duplicate mutations were either retained, or excluded, as indicated in the Table legends. Mutation frequencies were calculated based on the set with duplicate mutations excluded.

2.4 Analysis of CSR in mice

(i) Isolation of naïve, splenic B cells

Spleens were removed with sterile forceps and placed in sterile RPMI medium containing 10% FBS in a Petri dish on ice. Spleens were mashed through a sterile filter (0.45 μm, Nalgene) with the plunger of a tuberculin syringe into a 50-ml conical tube, and rinsed with 30-50 ml of RPMI. Pelleted cells were resuspended in a small volume (~1ml) of a 9:1 mixture of distilled water: serum-free RPMI, and placed on ice for 30 seconds to lyse red blood cells, whereupon RPMI was added immediately to rinse cells. The suspension was filtered once again, pelleted and resuspended to a cell density of 108 cells/ mL in cold RPMI 10% FBS or sterile PBS 0.5% BSA. Magnetic beads coated with anti-CD43 (cat# 130-049-801, Miltenyi Biotech) were added as recommended by the manufacturer (10 μl of bead suspension per 107 cells) and incubated in a refrigerator for 15 minutes. Cells were washed once with 50 ml of cold serum-free RPMI or PBS 0.5% BSA, resuspended to a cell density of ~108 cells/ml, and separated by magnetic sorting on an AutoMACs apparatus using the “Deplete-S” program to collect CD43- populations (saving the CD43+ bead-bound population as a control). Purity of CD43- populations was ~80-90% as assayed by staining a small portion of cells pre- and post-separation with anti-CD43 (biotinylated or PE-labeled, BD Biosciences), anti-CD19 (PE- or FITC-labeled, BD Biosciences) in the presence of Fc block (unlabeled anti-CD16/32, cat# 553142, BD Biosciences).

(ii) Activation of naïve splenic B cells for switch recombination

Purified CD43- naïve B cells were resuspended to 0.5-1 × 106 cells/ ml in RPMI 10% FBS (with L-glutamine, sodium-pyruvate, β-mercaptoethanol, penicillin/streptomycin) and stimulated for switch recombination with one or more of the following, as indicated: recombinant mouse interleukin-4 (cat# 404-ML, R&D systems) suspended in PBS 0.1% BSA, added to a final concentration of 25 ng/ml; anti-CD40 (HM40-3, BD Biosciences) to a final concentration of 1 μg/ml; lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma) to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml. Cells were cultured for 4-5 days, splitting with fresh medium containing stimulation factors as necessary based on the cell density.

(iii) RT-PCR analysis of switch-induced transcripts, and transcripts in splenic cell subsets

RNA was isolated from B cells pre- and post-activation either with the RNAqueous-4PCR kit (Ambion) or RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test Inc.). Template RNA of subsets to be compared were normalized for RNA concentration as measured by absorbance on a spectrophotometer (OD 260). First-strand cDNA was produced using the Superscript II cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Negative control templates were generated by identical first-strand synthesis reactions, but without addition of reverse transcriptase. Four-fold serial dilutions of first-strand cDNA were used as template for gene-specific PCR. Gene-specific primers and PCR conditions were as follows: AID was amplified with AID-118 (5’ GGCTGAGGTTAGGGTTCCATCTCAG 3’) and AID-119 (5’ GAGGGAGTCAAGAAAGTCACGCTGG 3’) [25] with PCR conditions of 1 cycle at 95°C for 5 minutes, 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds-57°C for 30 seconds-72°C for 50 seconds, followed by 1 cycle of 72°C for 7 minutes to generate a ~349-basepair product. GAPDH was amplified as house-keeping control gene with mGAPDH F (5’ ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC 3’) and mGAPDH R (5’ TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA 3’) [25] to amplify a ~400-basepair product using the same PCR cycling conditions as for AID primers. Aag transcripts were amplified with mAagF1 (5’ CAGAGCAGCAGCAGACCCC 3’) and mAag R1 (5’ CCTTGAGGGAACGGCCGACAGTGC 3’) to amplify a ~470-basepair product using the same PCR cycling conditions as for AID primers. ADAR1 transcripts were amplified with mADAR1F2 (5’ CACCAGGTGAGTTTCGAGCC 3’) and mADAR1R (5’ TCAGTCATTGGGTACTGGACGAG 3’) beginning with 1 cycle at 95°C for 4 minutes, touchdown cycling starting at 95°C for 30 seconds-58.5°C for 30 seconds-72°C for 3 minutes (decreasing the annealing temperature by 1°C for 8 cycles), then 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds-51°C for 30 seconds-72°C for 3 minutes, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes.

(iv) Flow cytometry for switched B cells

B cells cultured for 4-5 days in the presence of switching stimuli were harvested, rinsed in PBS and stained with antibodies against IgG1 (FITC-labeled, cat# 553443, BD Biosciences) or IgG3 (FITC-labeled, cat# 553403, BD Biosciences) and B220 (PE-labeled, BD Biosciences), or with B220 antibody alone. Flow cytometry was performed on a BD FACSCalibur instrument. Live cells were gated by forward- and side-scatter.

2.5 In vitro Alkyladenine DNA glycosylase assay

Cell extracts were made in glycosylase assay buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl pH7.6, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) from mouse B-cells that were stimulated or not with anti-CD40+IL-4 or LPS + IL-4, by sonication. Protein concentration was measured using micro BCA Kit (Pierce). Glycosylase assays were performed as previously published [20]. A [32P]γ labeled double-stranded 25mer oligonucleotide containing a single centrally located hypoxanthine residue [5’-GGATCATCGTTTTT(Hx)GCTACATCGC-3’] (Idenix) was incubated with 15 μg of extract (results with 15 μg of extract were found to be in the linear range for glycosylase activity measurement) at 37°C for 1h. The resulting abasic sites were cleaved by incubation with 0.1 N NaOH at 70 °C for 20 min. A phosphorimager was used both to visualize and quantitate Aag DNA glycosylase activity. Results are expressed as glycosylase activity per 100,000 cells.

3. Results

3.1 Expression of Aag in mutating and activated murine B cells

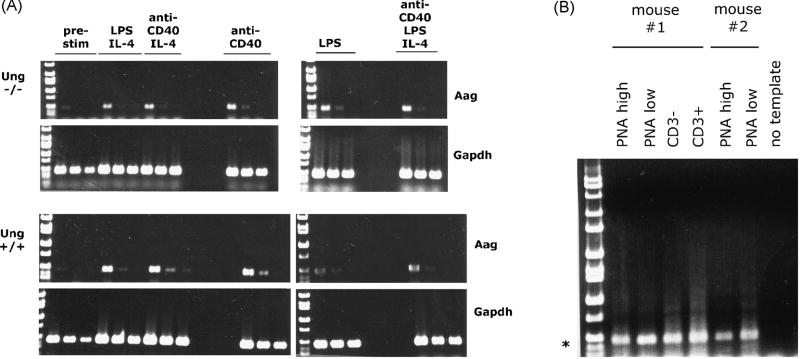

Aag is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues (NCBI Entrez Gene, GeneID: 26839), albeit at very different levels. However, in postulating a role for Aag in SHM that occurs specifically in a small subset of activated B cells during an immune response, expression of Aag was analyzed in germinal center activated B cells of immunized wildtype C57BL/6 mice. By RT-PCR, Aag is expressed in PNA-high, GL7+ (germinal center) B cells as well as other B220+ B cells, CD3+ cells (mainly T lymphocytes) and B200-, CD3- cells (eg., myeloid lineage cells) sorted by FACS from total spleen. The levels of Aag mRNAs appear to be roughly equivalent in all lymphocytes assayed (Fig. 1B). Similarly, splenic naïve B cells activated in vitro to perform class switch recombination (CSR) with a variety of stimuli (anti-CD40, IL-4, LPS, or combinations thereof) also express Aag, and the level of stable transcripts appears not to change significantly between stimulated and unstimulated controls, or between cells activated with different stimuli (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Alkyladenine DNA glycosylase (Aag) is expressed in activated B cells and other cells.

A. Naïve splenic B cells isolated from either Ung-/- or Ung+/+ mice were activated in vitro with the indicated stimuli (anti-CD40, IL-4 and/or LPS). After five days, RNA was isolated to provide a template for RT-PCR using primers specific for either Aag, or a control gene, Gapdh. The figure shows RT-PCR products using three serial diutions (1, 1/4, 1/16) for each sample as a template. B. Splenic B cells from two immunized Ung+/+ mice were sorted by FACS to obtain PNA high-germinal center B cells, PNA low B cells, CD3- non-B cells and CD3- lymphocytes. RNA isolated from these cell populations was used for RT-PCR using primers specific for Aag. PCR performed without the addition of template first strand cDNA was used as a negative control.

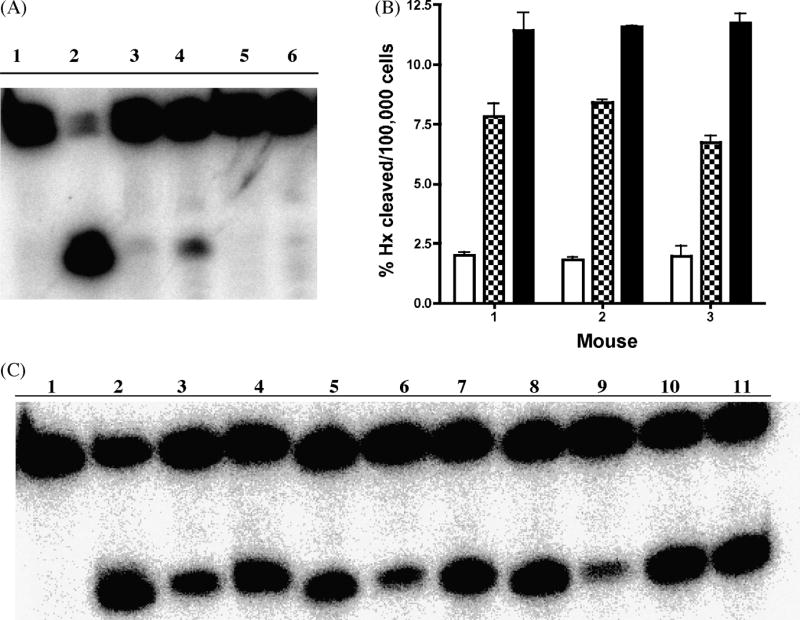

3.2 Aag glycosylase activity is induced in stimulated B-cells

Whole cell extracts prepared from mouse splenic B lymphocytes were tested for their glycosylase activity on Hx-containing DNA. Aag was shown to be the major if not the only activity to remove Hx in several mouse tissues including spleen [20,26] and unstimulated splenic B-lymphocytes (Fig. 2, panel A). Figure 2, panels B and C clearly demonstrate that Hx DNA glycosylase activity is dramatically induced in B-lymphocytes stimulated with anti-CD40 +IL-4 and with LPS +IL-4. Since transcript levels do nt change significantly, Aag activity appears to be upregulated post-transcriptionally.

Fig. 2. Hypoxanthine directed glycosylase activity is induced in stimulated splenic mouse cells.

A. Aag-/- deficient mouse splenic cells are devoid of Hx directed glycosylase activity. Hx containing DNA was incubated with no protein/extract (lane 1), 100 nM purified human AAG protein (lane 2), whole cell extract from unstimulated wild type (lanes 3 and 4) or Aag-/- (lanes 5 and 6) splenic lymphocytes. B. Hx directed glycosylase activity is induced in wild type splenic lymphocytes. Histogram graph showing quantification of two independent experiments using splenic cells from three wild type mice. Glycosylase activity for CD43- cells that are either unstimulated (open bars), stimulated with anti-CD40 +IL-4 (checkered bars) or stimulated with LPS +IL-4 (closed bars) is shown.

C. Representative gel (one out of two independent experiments) showing that Hx directed glycosylase activity is induced after antigenic stimulation in B-cells. Hx containing DNA was incubated with no protein (lane 1), 100 nM purified human AAG protein(lane 2), whole cell extracts from unstimulated cells (lanes 3, 6, and 9), whole cell extract from cells stimulated with anti-CD40 + IL-4 (lanes 4, 7, and 10) or stimulated with LPS +IL-4 (lanes 5, 8, and 11).

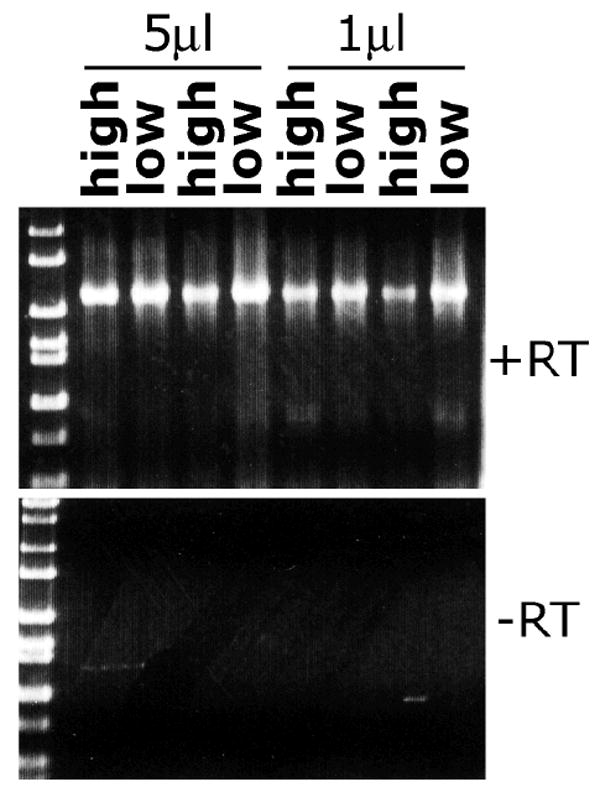

3.3 Expression of ADAR1 in activated B cells

ADAR1 is unique among the identified adenosine deaminases due to an N-terminal domain implicated in binding Z-DNA [27], an unusual DNA conformation of controversial, though increasingly intriguing in vivo relevance [28]. Interestingly, ADAR1 also possesses alternative splice forms in splenic cells that are induced by interferons (reviewed in [29], perhaps indicating an immune-specific isoform. Expression of ADAR1 was investigated by semi-quantitative RT-PCR in splenic PNA-high, GL7+ and PNA-low, GL7- B cells isolated by FACS from immunized C57BL/6 Ung+/+ and Ung-/- mice. ADAR1 is expressed in PNA-high and PNA-low B cells, and the expression levels appear similar, as assayed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

ADAR1 is expressed in PNA high germinal center and PNA low non-germinal center B cells. RNA isolated from PNA high GL7+ and PNA low GL7-low splenic B cells from two immunized wild type mice was used as a template (either 1μl or 5 μl of first-strand cDNA generated from ~0.2 μg RNA) for RT-PCR using primers specific for ADAR1. ADAR1 is expressed in both subsets, apparently to similar levels. Reverse transcriptase (RT) was excluded in a parallel first-strand cDNA synthesis reaction to generate template for the negative control PCR using ADAR1-specific primers.

3.4 Somatic hypermutation in Aag-deficient mice

Aag-/- mice were analyzed for their ability to perform SHM and for the pattern of SHM. Germinal center B cells from Peyer’s patches of unimmunized Aag-/- and Aag+/+ controls were sorted by FACS to obtain PNA-high, GL7+ germinal center B cells. Genomic DNA from sorted cells was isolated, and used as template DNA for PCR amplification of VJ558-J4 rearranged IgH genes. PCR products were cloned and sequenced. Mutations in a 585-basepair, unselected intronic region (see Materials and methods) just downstream of J4 were analyzed in four independent sets of mice. The results are presented in Tables 1 (all mutations included) and 2 (excluding duplicated mutations that might result in resampling of the same mutations in clonally related cells). Importantly, under the premise of an adenosine deaminase in SHM, Hx-T mispairs in the absence of Aag are expected to cause A:T > G:C and T:A > C:G transition mutations predominantly. In Aag+/+ mice the most common mutations from A and T are transitions. This tendency seems not to be altered drastically by absence of Aag, despite some variability in the mutation patterns between different experiments (Table 2). For example, A:T > G:C mutations are slightly more frequent in Aag- mice (23, 18 and 20% of the total) than Aag-/- mice (16, 11 and 17%) in experiments #1, #2 and #4, but slightly more frequent in Aag-/- mice (23% in Aag-/- versus 15% in Aag+/+) in experiment #3 (Table 2). These variations in mutation patterns are not statistically significant (p = 0.58 and 0.35, including or not including duplicated mutations, respectively). For bottom-strand mutations, the frequency of T:A > C :G is slightly elevated in all experiments in Aag-/- mice (14, 14, 12 and 13%) as compared with Aag+/+ mice (5.7, 8.1, 11, and 9.8%), and the elevation is statistically significant (p = 0.015 and 0.03, including or not including duplicated mutations, respectively). Nevertheless, neither A:T > G:C, nor T:A > C:G changes appear to be dramatically different in frequency between Aag+/+ and Aag-/- mice as would be expected if Hx bases generated by an adenosine deaminase were left totally unrepaired in Aag-/- mice. Finally, the frequency of all mutations in Aag+/+ and Aag-/- mice were similar (Table 2 legend).

Table 1.

Patterns of somatic mutations downstream of IgH J4 in Aag+/+ versus Aag-/- mice. Somatic hypermutations were analyzed in VHJ558-rearranged endogenous IgH genes from germinal center B cells in Peyer’s patches. The original base, according to Genbank accession # X53774, is indicated along the left column; the base to which it is mutated is on the horizontal axis. Four sets (Experiment #1-4) of Aag-/- mice (Peyer’s patches pooled from 2-3 mice of identical genotype) were analyzed in parallel with Aag+/+ control mice. The total number of mutations is indicated for each set. For each class of mutation, the raw number of mutations is provided, and the percent of the total indicated in brackets below. Numbers in mutation classes (A to G and T to C) where a change was expected in Aag-/- mice based on the hypothesis are in bold text. All mutations, including duplicated mutations, are included in this data set.

| Exp. | Duplicate mutations included | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | to | Aag+/+ | Total | Aag-/- | Total | |||||||

| from | A | C | G | T | 74 | A | C | G | T | 189 | ||

| A | 5 (6.8) | 18 (24) | 8 (11) | 31 (42) | A | 19 (10) | 31 (16) | 24 (13) | 74 (39) | |||

| C | 1 (1.4) | 4 (5.4) | 8 (11) | 13 (18) | C | 4 (2.1) | 3 (1.6) | 4 (2.1) | 11 (5.8) | |||

| G | 9 (12) | 5 (6.8) | 3 (4.1) | 17 (23) | G | 26 (14) | 10 (5.3) | 8 (4.2) | 44 (23) | |||

| T | 5 (6.8) | 4 (5.4) | 4 (5.4) | 13 (18) | T | 19 (9.5) | 27 (14) | 16 (7.9) | 60 (32) | |||

| #2 | A | C | G | T | 204 | A | C | G | T | 226 | ||

| A | 17 (8.3) | 34 (17) | 22 (11) | 73 (36) | A | 21 (9.3) | 26 (12) | 25 (11) | 72 (32) | |||

| C | 8 (3.9) | 6 (2.9) | 14 (6.9) | 28 (14) | C | 5 (2.2) | 7 (3.1) | 20 (8.8) | 32 (14) | |||

| G | 43 (21) | 14 (6.9) | 8 (3.9) | 65 (32) | G | 31 (14) | 22 (9.7) | 3 (2.2) | 56 (26) | |||

| T | 11 (5.4) | 13 (6.4) | 14 (6.9) | 38 (19) | T | 21 (9.3) | 30 (13) | 13 (5.8) | 64 (28) | |||

| #3 | A | C | G | T | 226 | A | C | G | T | 214 | ||

| A | 21 (9.3) | 33 (15) | 24 (11) | 78 (35) | A | 14 (6.5) | 48 (22) | 21 (9.8) | 83 (39) | |||

| C | 4 (1.8) | 2 (1) | 35 (16) | 41 (19) | C | 2 (1) | 9 (4.2) | 21 (9.8) | 32 (15) | |||

| G | 33 (15) | 12 (5.3) | 8 (3.5) | 53 (24) | G | 29 (14) | 9 (4.2) | 5 (2.3) | 43 (21) | |||

| T | 16 (7.1) | 25 (11) | 13 (5.8) | 54 (24) | T | 18 (8.4) | 22 (10) | 16 (7.5) | 56 (26) | |||

| #4 | A | C | G | T | 214 | A | C | G | T | 53 | ||

| A | 15 (7) | 44 (21) | 27 (13) | 86 (41) | A | 3 (5.7) | 9 (17) | 5 (9.4) | 17 (32) | |||

| C | 3 (1.4) | 5 (2.3) | 17 (7.9) | 25 (12) | C | 2 (3.8) | 2 (2.8) | 7 (13) | 11 (21) | |||

| G | 29 (14) | 9 (4.2) | 6 (2.8) | 44 (21) | G | 6 (11) | 2 (3.8) | 3 (5.7) | 11 (21) | |||

| T | 23 (11) | 19 (8.9) | 17 (7.9) | 59 (28) | T | 4 (7.5) | 7 (13) | 3 (5.7) | 14 (26) | |||

Table 2. Patterns of somatic mutations downstream of IgH J4 in Aag+/+ versus Aag-/- mice. Duplicated mutations are excluded in this data set. See legend to Table 1.

Mutation frequencies of this data set (duplicates excluded) for each experiment were calculated as the number of total mutations (point mutations plus insertions/deletions), divided by the number of basepairs sequenced in clones with mutations. Mutation frequencies for Aag+/+ were 0.95 × 10-2, 1.1 × 10-2, 2.2 × 10-2, 2.8 × 10-2; for Aag-/- : 2.9 × 10-2, 1.8 × 10-2, 2.1 × 10-2, 1.5 × 10-2 , for sets 1-4, respectively.

| Exp. | Duplicate mutations included | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | to | Aag+/+ | Total | Aag-/- | Total | |||||||

| from | A | C | G | T | 70 | A | C | G | T | 187 | ||

| A | 5 (7.1) | 16 (23) | 7 (10) | 28 (40) | A | 20 (12) | 31 (16) | 23 (11) | 74 (39) | |||

| C | 1 (1.4) | 4 (5.7) | 8 (11) | 13 (18) | C | 4 (2.1) | 3 (1.6) | 4 (2.1) | 11 (5.8) | |||

| G | 9 (13) | 5 (7) | 2 (2.9) | 16 (23) | G | 25 (13) | 10 (5.3) | 8 (4.3) | 43 (23) | |||

| T | 5 (7.1) | 4 (5.7) | 4 (5.7) | 13 (19) | T | 18 (9.6) | 26 (14) | 15 (8.0) | 59 (32) | |||

| #2 | A | C | G | T | 160 | A | C | G | T | 194 | ||

| A | 14 (8.7) | 29 (18) | 18 (11) | 61 (38) | A | 18 (9.3) | 21 (11) | 23 (12) | 62 (32) | |||

| C | 5 (3.1) | 5 (3.1) | 11 (6.8) | 21 (13) | C | 4 (2.1) | 6 (3.1) | 18 (9.3) | 28 (15) | |||

| G | 30 (19) | 8 (5.0) | 6 (3.7) | 44 (28) | G | 23 (12) | 18 (9.3) | 5 (2.6) | 46 (24) | |||

| T | 11 (6.8) | 13 (8.1) | 10 (6.2) | 34 (21) | T | 19 (9.8) | 28 (14) | 11 (5.7) | 58 (30) | |||

| #3 | A | C | G | T | 149 | A | C | G | T | 150 | ||

| A | 15 (10) | 23 (15) | 17 (11) | 55 (36) | A | 11 (7.7) | 33 (23) | 13 (9.1) | 57 (40) | |||

| C | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.3) | 19 (13) | 24 (16) | C | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.5) | 10 (7.0) | 17 (12) | |||

| G | 22 (15) | 7 (4.7) | 5 (3.4) | 34 (23) | G | 18 (13) | 6 (4.2) | 3 (2.1) | 27 (17) | |||

| T | 9 (6) | 17 (11) | 10 (6.7) | 36 (24) | T | 16 (11) | 17 (12) | 9 (6.3) | 42 (29) | |||

| #4 | A | C | G | T | 163 | A | C | G | T | 51 | ||

| A | 11 (6.7) | 32 (20) | 20 (12) | 63 (39) | A | 3 (5.7) | 9 (17) | 5 (9.4) | 17 (32) | |||

| C | 3 (1.8) | 5 (3.1) | 9 (5.5) | 17 (10) | C | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.8) | 7 (13) | 10 (19) | |||

| G | 24 (15) | 8 (4.9) | 5 (3.1) | 37 (23) | G | 5 (9.4) | 2 (3.8) | 3 (5.7) | 10 (19) | |||

| T | 16 (9.8) | 16 (9.8) | 14 (8.6) | 46 (28) | T | 4 (7.5) | 7 (13) | 3 (5.7) | 14 (26) | |||

The observed increase in T:A > C:G mutations in Aag-/- mice could be unrelated to SHM and happen due to a genome-wide event that would also be observed in non-mutating B cells. In order to assess whether Aag deletion has an effect on overall mutability, we sequenced the same Ig genes in PNA-lo, non-mutating B cells. Only two mutations were found in 37,700 nucleotides from Aag-/- mice (G to T and A to G) for a background mutation frequency of 5.3×10-5 (versus 4.8×10-5 in Aag+/+ mice). Thus, Aag-/- mice do not hypermutate and Aag may be involved in SHM (see Discussion).

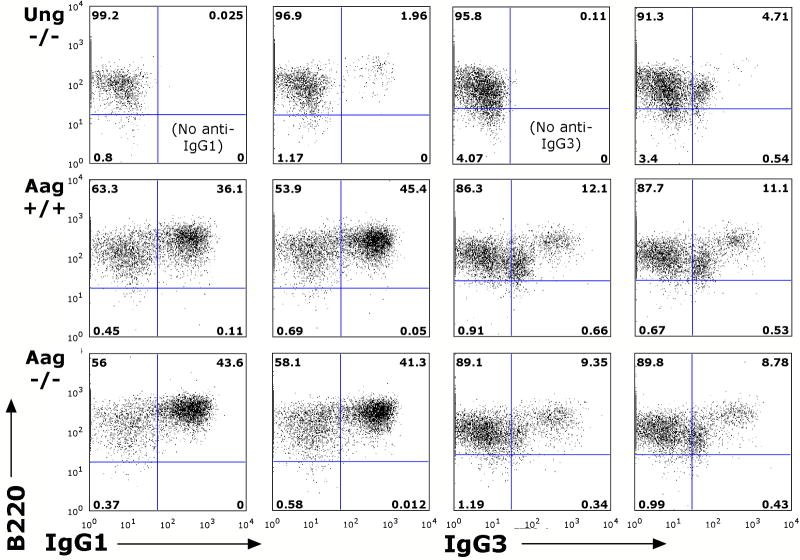

3.5 Class switch recombination in Aag-/- mice

Ung-deficient mice are impaired for CSR. To test whether Aag-/- mice are similarly deficient for class switching, naïve splenic B cells were isolated from spleens of the non-immunized Aag-/- and Aag+/+ mice, and stimulated in vitro with LPS, either with or without IL-4 co-stimulation, for five days. All switch-inducing stimuli tested resulted in the induction of AID transcription (data not shown), whereas treatment with IL-4 alone did not (and also did not promote healthy cell division). Stimulated cells were then stained with antibodies to IgG1, or IgG3 and analyzed by flow cytometry for the presence of switched B cells. Although Ung-/- B cells tested in parallel clearly produce fewer switched B cells, drastically so for IgG1, the Aag-/- B cells produce switched B cells of both isotypes in similar numbers to control Aag+/+ B cells (Fig. 4). Similarly, serum titers of switched isotypes in adult mice were reported not to be altered in Aag-/- mice [30].

Fig. 4.

Class switch recombination can be induced normally in Aag-/- B cells. Naïve splenic B cells were isolated from spleens of one Ung-/- mouse, two Aag+/+ and two Aag-/- mice, and induced in vitro with either LPS to induce switching to IgG1, or LPS and IL-4 to induce switching to IgG3. Whereas Ung-/- B cells (B220+) are impaired for switching to either isotype, Aag-/- cells are not, in comparison to the Aag+/+ B cells. Shown is one representative experiment of two.

4. Discussion

The findings in Aag-/- mice challenge the idea that an adenine DNA deaminase exists that operates in parallel with AID during somatic hypermutation. Aag possesses unusually broad substrate specificity for damaged DNA bases, in particular for alkylated purines, although Hx is a preferred substrate at least in vitro [31]. Moreover, Aag is reported to be the major mammalian glycosylase that functions to remove Hx from DNA in liver, testes, kidney and lung [20]. So, if deaminated A (Hx) is present in Ig DNA during SHM, Aag was the most logical suspect to be recruited for repair, or co-opted for SHM. Our analysis represents the first examination of sequence changes in DNA that might occur due to mammalian Aag-deficiency in any tissue.

The possibility exists that another Hx glycosylase is perhaps specific for mutating B cells and involved in SHM. An alternative candidate for removal of Hx in DNA is the recently identified mammalian homolog of Endonuclease V (EndoV) [32]. E.coli with mutations in nfi, the gene encoding Endo V, accumulate A:T > G:C transitions in response to nitrous acid, which largely causes deamination of A [33]. Perhaps, Endo V or another enzyme is specifically co-opted for mutations at A in SHM. By analogy, the functions of Ung and Smug uracil glycosylases are very similar, but both Smug expression and activity are low in activated B cells, whereas Ung expression and activity increase with time post-activation [34]. As such, only Ung is able to catalyze SHM and CSR efficiently in physiological conditions. Thus, potential roles of an unknown adenosine deaminase and EndoV in creating mutations from A in SHM cannot be laid to rest without further experiments.

We have observed a statistically significant increase in T to C mutations in the Aag-/- mice, while no significant difference in the frequency of A to G was observed between Aag-/- and Aag+/+ mice. Interestingly, in Aag+/+ mice, mutations at A are always more frequent on the non-transcribed strand than on the transcribed strand (Tables 1 and 2). Observing about twice as many mutations at A than T on the non-transcribed strand indicates that there must be both an A/T bias and a strand bias [35]. The A>T bias may be explained by the error-bias when copying T of translesion polymerases, such as η and ι [36,37]. We postulate, that there may also be an A > T bias because of spontaneous or even adenosine deaminase-induced deaminations of adenines at both DNA strands during SHM.

The strand bias may be partially due to transcription-coupled activity of the translesion polymerases [38]. In addition, there may be preferential targeting of Aag to the transcribed strand. Transcription-coupled repair of 7MeG and 3MeA was previously examined and no strand bias was detected on the repair of these lesions by Aag [39]. However, it is formally possible that Hx repair could be transcription-coupled (or become transcription-coupled in SHM) and this remains to be determined.

In this scenario and based on our findings, significant increases of spontaneous or even adenosine deaminase-induced deaminations at A only would occur during SHM. There was no increase in mutations in resting B cells from Aag-/- mice. In these cells that do not undergo SHM the Ig genes are expressed at similar rates as in the mutating B cells that do acquire A to G mutations in the transcribed strand when Aag is absent. The susceptibility of both DNA strands to whichever A deamination mechanisms, would parallel the equal susceptibility of both the transcribed and non-tanscribed strands to AID [40,41].

The reduced A > T bias in Aag-/- mice suggests that Aag may be partially responsible for creating this strand bias in wild type mice. This may correlate with the significantly upregulated activity of Aag in germinal center mutating B cells (Fig. 2). Models of how mutations may be linked to spontaneous or adenosine deaminase-induced A deaminations, DNA repair, and transcription may not be conclusively tested until a cell-free assay for SHM has been developed.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to D. Nicolae for statistical analysis and G. Bozek for excellent technical assistance. We thank Drs. D. Barnes and T. Lindahl for Ung-/- mice. Research was funded by grants AI047380 (NIH-NIAID) and AI053130 (NIH-NIAID) to US, and P30-ES02109 (NIH/NIEHS) and 7-RO1-CA75576 (NIH/NCI) to LDS. SL was supported by an American Association of University Women International Ph.D. Fellowship. LDS is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Longerich S, Basu U, Alt F, Storb U. AID in somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Z, Peled JU, Zhao C, Svetlanov A, Ronai D, Cohen PE, Scharff MD. A role for Mlh3 in somatic hypermutation. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu X, Tsai CY, Patam MB, Zan H, Chen JP, Lipkin SM, Casali P. A role for the MutL mismatch repair Mlh3 protein in immunoglobulin class switch DNA recombination and somatic hypermutation. J Immunol. 2006;176:5426–5437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rada C, Williams G, Nilsen H, Barnes D, Lindahl T, Neuberger M. Immunoglobulin isotype switching is inhibited and somatic hypermutation perturbed in UNG-deficient mice. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1748–1755. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai K, Slupphaug G, Lee WI, Revy P, Nonoyama S, Catalan N, Yel L, Forveille M, Kavli B, Krokan HE, Ochs HD, Fischer A, Durandy A. Human uracil-DNA glycosylase deficiency associated with profoundly impaired immunoglobulin class-switch recombination. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1023–1028. doi: 10.1038/ni974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klungland A, Lindahl T. Second pathway for completion of human DNA base excision -repair: reconstitution with purified proteins and requirement for DNase IV (FEN1) EMBO J. 1997;16:3341–3348. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seki M, PJ G, RD W. DNA polymerases and somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:1143–1148. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen H-S, Tanaka A, Bozek G, Nicolae D, Storb U. Somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination in Msh6-/-Ung-/- double-knockout mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:5386–5392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Z, Scherer S, R D, Iglesias-Ussel M, Peled J, Bardwell P, Zhuang M, Lee K, Martin A, Edelmann W, Scharff M. Examination of Msh6- and Msh3-deficient mice in class switching reveals overlapping distinct roles of MutS homologues in antibody diversification. J Exp Med. 2004;200:47–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neuberger MS, Di Noia JM, Beale RC, Williams GT, Yang Z, Rada C. Somatic hypermutation at A.T pairs: polymerase error versus dUTP incorporation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nri1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martomo SA, Yang WW, Wersto RP, Ohkumo T, Kondo Y, Yokoi M, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Gearhart PJ. Different mutation signatures in DNA polymerase eta- and MSH6-deficient mice suggest separate roles in antibody diversification. Proc Natl Acad. 2005;102:8656–8661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501852102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng X, Winter D, Kasmer C, Kraemer K, Lehmann A, Gearhart P. DNA polymerase eta is an A-T mutator in somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable genes. Nature Immunology. 2001;2:537–541. doi: 10.1038/88740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faili A, Aoufouchi S, Weller S, Vuillier F, Stary A, Sarasin A, Reynaud C, Weill J. DNA polymerase eta is involved in hypermutation occurring during immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J Exp Med. 2004;199:265–270. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng X, Negrete G, Kasmer C, Yang W, Gearhart P. Absence of DNA polymerase eta reveals targeting of C mutations on the nontranscribed strand in immunoglobulin switch regions. J Exp Med. 2004;199:917–924. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delbos F, De Smet A, Faili A, Aoufouchi S, Weill J-C, Reynaud C-A. Contribution of DNA polymerase eta to immunoglobulin gene hypermutation in the mouse. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1191–1196. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karran P, Lindahl T. Hypoxanthine in deoxyribonucleic acid: generation by heat-induced hydrolysis of adenine residues and release in free form by a deoxyribonucleic acid glycosylase from calf thymus. Biochemistry. 1980;19:6005–6011. doi: 10.1021/bi00567a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill-Perkins M, Jones MD, Karran P. Site-specific mutagenesis in vivo by single methylated or deaminated purine bases. Mutat Res. 1986;162:153–163. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(86)90081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maas S, Rich A, Nishikura K. A-to-I RNA editing: recent news and residual mysteries. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1391–1394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelward B, Weeda G, Wyatt M, Broekhof J, De Wit J, Donker I, Allan J, Gold B, Hoeijmakers J, Samson L. Base excision repair deficient mice lacking the Aag alkyladenine DNA glycosylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13087–13092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilsen H, Rosewell I, Robins P, Skjelbred C, Andersen S, Slupphaug G, Daly G, Krokan H, Lindahl T, Barnes D. Uracil-DNA glycosylase (UNG)-deficient mice reveal a primary role of the enzyme during DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2000;5:1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longerich S, Tanaka A, Bozek G, Nicolae D, Storb U. The very 5’ end and the constant region of Ig genes are spared from somatic mutation because AID does not access these regions. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1443–1454. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rada C, Milstein C. The intrinsic hypermutability of antibody heavy and light chain genes decays exponentially. Embo J. 2001;20:4570–4576. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jolly C, Klix N, Neuberger M. Rapid methods for the analysis of Ig gene hypermutation:application to transgenic and gene targeted mice. Nucleic Acids Rs. 1997;25:1913–19199. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.10.1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muramatsu M, Sankaranand VS, Anant S, Sugai M, Kinoshita K, Davidson NO, Honjo T. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18470–18476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth RB, Samson LD. 3-Methyladenine DNA glycosylase-deficient Aag null mice display unexpected bone marrow alkylation resistance. Cancer Res. 2002;62:656–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim YG, Lowenhaupt K, Maas S, Herbert A, Schwartz T, Rich A. The zab domain of the human RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 recognizes Z-DNA when surrounded by B-DNA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26828–26833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003477200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang G, Vasquez KM. Non-B DNA structure-induced genetic instability. Mutat Res. 2006;598:103–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keegan LP, Leroy A, Sproul D, O’Connell MA. Adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs): RNA-editing enzymes. Genome Biol. 2004;5:209. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobs H, Fujita Y, van der Horst G, de Boer J, Weeda G, Essers J, de Wind N, Engelward B, Samson L, Verbeek S, de Murcia J, de Murcia G, te Riele H, Rajewsky K. Hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes in memory B cells of DNA repair-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1735–1743. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.11.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Brien PJ, Ellenberger T. Dissecting the broad substrate specificity of human 3-methyladenine-DNA glycosylase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9750–9757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moe A, Ringvoll J, Nordstrand L, Eide L, Bjoras M, Seeberg E, Rognes T, Klungland A. Incision at hypoxanthine rsidues in DNA by a mammalian holologue of the E.coli antimutator enzyme endonuclease V. Nucl Acids Res. 2004;31:3893–3900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schouten KA, Weiss B. Endonuclease V protects Escherichia coli against specific mutations caused by nitrous acid. Mutat Res. 1999;435:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(99)00049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Noia JM, Rada C, Neuberger MS. SMUG1 is able to excise uracil from immunoglobulin genes: insight into mutation versus repair. Embo J. 2006;25:585–595. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Storb U, Peters A, Klotz E, Kim N, Shen HM, Kage K, Rogerson B. Somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes is linked to transcription. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol. 1998b;229:11–19. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71984-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunkel T, Pavlov Y, Bebenek K. Functions of human DNA polymerases eta, kappa, and iota. DNA Repair. 2003;2:135–149. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tissier A, McDonald JP, Frank EG, Woodgate R. pol iota, a remarkably error-prone human DNA polymerase. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1642–1650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delbos F, Aoufouchi S, Faili A, Weill JC, Reynaud CA. DNA polymerase eta is the sole contributor of A/T modifications during immunoglobulin gene hypermutation in the mouse. J Exp Med. 2007;204:17–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plosky B, Samson L, Engelward BP, Gold B, Schlaen B, Millas T, Magnotti M, Schor J, Scicchitano DA. Base excision repair and nucleotide excision repair contribute to the removal of N-methylpurines from active genes. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:683–696. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen HM, Storb U. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) can target both DNA strands when the DNA is supercoiled. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12997–13002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404974101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen H, Ratnam S, Storb U. Targeting of the activation-induced cytosine deaminase is strongly influenced by the sequence and structure of the targeted DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10815–10821. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10815-10821.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]