Abstract

Background

Despite growing public concern about child maltreatment, the scope and severity of this significant public health issue remains poorly understood. This article examines the nature and severity of the physical harm associated with reports of child maltreatment documented in the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS).

Methods

The CIS collected information directly from child welfare investigators about cases of reported child abuse or neglect. A multistage sampling design was used to track child-maltreatment investigations conducted at selected sites from October to December 1998. The analyses were based on the sample of 3780 cases in which child maltreatment was substantiated.

Results

Some type of physical harm was documented in 18% of substantiated cases; most of these involved bruises, cuts and scrapes. In 4% of substantiated cases, harm was severe enough to require medical attention, and in less than 1% of substantiated cases, medical attention was sought for broken bones or head trauma. Harm was noted most often in cases of physical abuse compared to other forms of maltreatment.

Interpretation

Rates of physical harm were lower than expected. Current emphasis on mandatory reporting, abuse investigations and risk assessment may need to be tempered for cases in which physical harm is not the central concern.

Since the term “battered child syndrome” was first coined by Dr. Kempe and his colleagues1 in 1962, professional and public awareness of the plight of maltreated children has expanded to include child sexual abuse, child neglect and, most recently, emotional maltreatment. Battered child syndrome was initially formulated to explain patterns of unexplained fractures in young children detected by x-ray and eventually included all forms of physical abuse of children by their caregivers. Kempe's initial formulation of this syndrome has shaped our response to this major public health problem. To prevent cases from leading to severe injury or death, we have developed a protection system that stresses early identification, mandatory reporting, investigation and risk assessment. This response reflects a perception that severe injuries are common in cases of child maltreatment. For example, in their recent article in the Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Kocher and Kasser state that “more than 1 million children each year are the victims of substantiated abuse or neglect,” that “fractures are the second most common presentation of physical abuse after skin lesions, and approximately one third of abused children will eventually be seen by an orthopaedic surgeon.”2

Although tragic cases involving severe injuries and deaths draw significant attention, the scope and severity of this public health issue remain poorly understood. Few studies have documented rates of injuries in cases of child maltreatment investigated by child protection authorities. Direct comparison of the 9 published studies3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 that compared injured and noninjured maltreated children is complicated by the variability in the populations studied (denominator) and in the definitions of injury (numerator).12 Two studies included US national probability samples;5,8 1 study, a national British sample;4 4 studies, city-wide to state- or province-wide samples;7,9,10,11 1 study, a US national army sample;6 and 1 study, a medical clinic sample.3 Most studies examined substantiated or registered child protection services (CPS) cases.4,7,9,10,11 Two included CPS-substantiated cases as well as cases identified by other community professionals;5,8 1 examined injuries documented in police investigations of physical and sexual abuse;10 1 included all CPS cases, regardless of case substantiation;6 and 1 reported on suspected child sexual abuse cases examined by a physician.3

Four studies defined injury severity on the basis of need for medical attention,5,8,9,10 whereas 3 classified injuries on the basis of their nature and location (e.g., soft tissues v. more severe injuries).4,7,11 Two studies did not indicate severity of injury;3,9 2 others aggregated physical and emotional harm data.5,8 Injury rates (the number of injured children per number of maltreated children) ranged from 34%5 to 63%11 for any type of documented harm, and from 3.8%7 to 20%8 for injuries classified as severe. The range of estimates was less dramatic when the 4 studies6,7,10,11 that used comparable denominators (substantiated maltreatment investigations) and numerators (moderate or severe physical injury) were compared: severe injury was documented in 3.8%–4.6% of substantiated cases and mild-to-moderate in 36%–63%.

Overall, research on injury caused by maltreatment is limited because of nonrepresentative sampling and inadequate measurement of injury. The purpose of this study was to describe the nature and severity of the physical harm caused by child abuse and neglect, as documented in a nationally representative sample of Canadian child protection cases that use measures describing both type and severity of injury. A secondary purpose was to estimate national rates of physical harm caused by substantiated child maltreatment.

Methods

The 1998 Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS) (the source of the data analyzed in this study) collected information directly from child welfare investigators about a national sample of children reported to child welfare authorities because of suspected child abuse or neglect.13 This 1998 study was the first wave of Health Canada's national child maltreatment surveillance program designed to be repeated in 5-year cycles (CIS-2 data will be collected from October 2003 to March 2004). A multistage sampling design was used, first to select a representative sample of 51 child welfare service areas from each province and territory across Canada and then to track child- maltreatment investigations conducted at the selected sites from October to December 1998. For each sampled case, child welfare workers reported the results of their investigations, details about the specific maltreatment incidents, and child and family characteristics. Although the CIS is the most comprehensive national child-maltreatment dataset available in Canada, the study did not track (1) incidents that were not reported to child welfare authorities, (2) reported cases that were screened out by child welfare authorities before being fully investigated, (3) new reports on cases already opened by child welfare authorities and (4) cases that were investigated only by the police.

Twenty-two forms of maltreatment subsumed into 4 categories (physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect and emotional maltreatment) were tracked by the CIS. This classification reflects a fairly broad definition of child maltreatment and includes several forms of maltreatment that are not specifically included in some provincial and territorial child welfare statutes (e.g., educational neglect and exposure to family violence). Cases were classified as substantiated if the balance of evidence indicated that a child was harmed or was at serious risk of harm as a result of a parent's action or failure to act, as specified by provincial and territorial statutes. Child welfare investigations typically included separate interviews with the alleged victim, siblings, parents and the person who made the report. If physical harm was suspected, the worker also conducted a physical examination. In cases of injuries that appeared serious or were difficult to interpret and in cases that involved suspected sexual abuse, a physician or a hospital-based child abuse team also completed a physical examination. Workers participating in the CIS received a half-day of training to ensure uniform application of study procedures and definitions. The estimated response rate for the CIS was 90% and the item completion rate was over 95% for all questions.14

Information about physical harm caused by maltreatment was collected from the answers to questions adapted from the nature and severity of injury scales developed in previous incidence studies.8,15 The nature of harm included injuries or health conditions visible for at least 48 hours and was classified into 5 categories: (1) bruises, cuts and scrapes, (2) burns and scalds, (3) broken bones, (4) head trauma and (5) other health conditions such as complications from untreated asthma or a sexually transmitted disease. The investigating workers judged the severity of harm according to the need for medical treatment: severe harm was defined as conditions that required medical treatment, and moderate harm as those in which physical harm was observed but not thought to require medical care.

The final study identified a sample of 7672 child-maltreatment investigations; 3780 (49%) of these investigations involved substantiated maltreatment. Analyses presented in this paper were limited to these 3780 substantiated cases.

Annualization and regionalization weights that reflect the sampling strategy used (see Trocmé and colleagues14 for details of weighting procedures) were used to calculate annual estimates. Confidence intervals were constructed with the replicate weights variance estimation method that uses the WesVar PC JKn jacknife procedure.8,16 Because the weighting procedure adjusted for the sampling design, direct comparisons could not be made between the unweighted data in Tables 1–3 and the weighted data in Table 4, and in other publications.

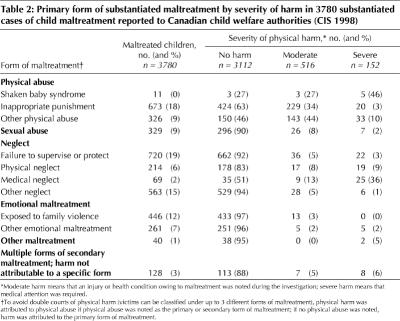

Table 1

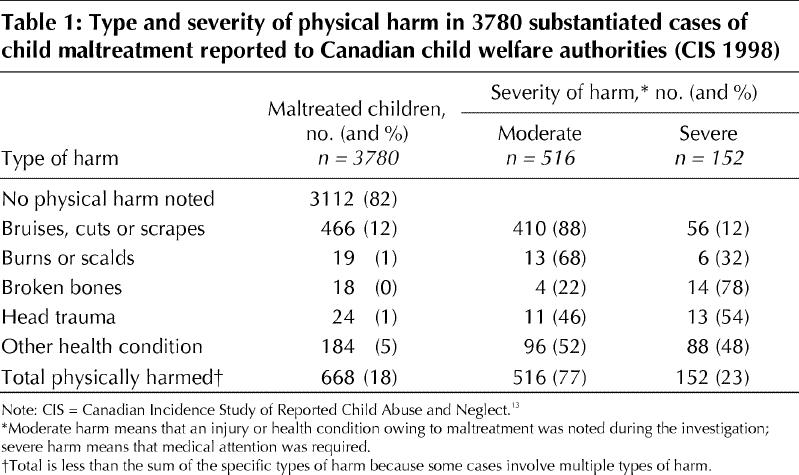

Table 2

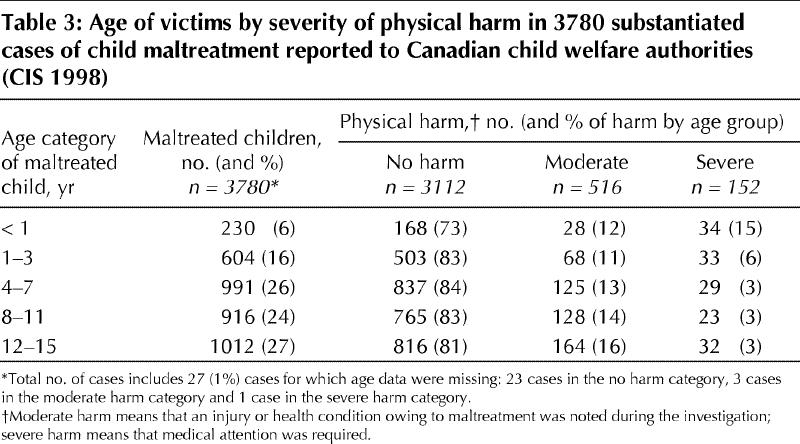

Table 3

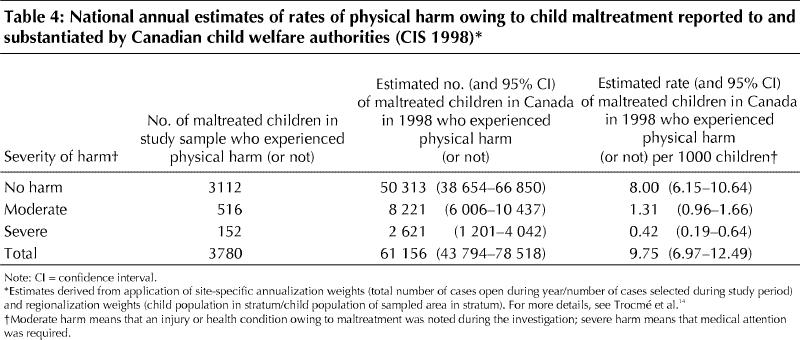

Table 4

Results

No physical harm was noted in most cases of substantiated maltreatment. When harm was noted it usually involved bruises, cuts and scrapes (Table 1). In the judgement of the investigating worker most (88%; 410 of 466 cases) of these injuries did not require treatment. Burns, broken bones and head trauma were documented more rarely (19, 18 and 24 cases respectively), but these injuries were much more often judged severe: 32%–78% of these injuries (6, 14 and 13 cases respectively) required medical care. Other health conditions were noted in 5% of substantiated cases (184 of 3780 cases); nearly half of these (88 cases) required medical treatment. No fatality estimates were provided because the small number of fatalities documented by the study was insufficient for the calculation of fatality estimates. In Canada police report fewer than 100 child homicides a year (less than 1.5 homicides per 100 000 children) to the Statistics Canada Child Homicide Survey.17

Table 2 presents the breakdown of the severity of physical harm by the primary form of substantiated maltreatment. In cases involving a combination of physical abuse and other forms of maltreatment, harm was attributed to the physical abuse and not counted under the other forms of maltreatment. Some type of physical harm was noted in 43% of all physical abuse cases (433 of 1010 cases). Proportionally, severe harm was noted most often in cases of shaken baby syndrome (45%; 5 of 11 cases). In cases involving inappropriate punishment or other physical abuse, documented harm primarily involved minor bruises, cuts or scrapes that did not require medical attention.

Physical harm was noted much less often in cases of sexual abuse, neglect and emotional maltreatment (8%; 220 of 2642 nonphysical abuse cases) than in cases of physical abuse (43%; 433 of 1010 physical abuse cases); however, physical harm was noted in 49% of cases of medical neglect (34 of 69 cases) for which some type of harm, primarily an untreated health condition, was noted. In cases of sexual abuse, harm involved bruising or health conditions such as a sexually transmitted disease. Although harm was not often noted in cases of neglect, cases of neglect involving harm nevertheless represented an important proportion (47%; 72 of 152 cases) of the severe harm situations documented in the study.

The CIS documented a large number (446) of cases in which exposure to family violence was the primary issue of concern. Although potential injury to the child is a concern in these situations, severe physical harm was documented in less than 1% of cases.

Table 3 presents the severity of harm by age category. Children under 1 year of age sustained more severe injuries as a result of maltreatment: 15% (34 of 230 children less than 1 year of age) sustained a severe injury as compared to 3% (117 of 3523 children 1–15 years) for older children (p = 0.001). In contrast, minor injuries increased with age: harm was reported more often for adolescents (16%; 164 of 1012 children 12–15 years) than children under 12 years of age (13%; 349 of 2741 children less than 12 years) (p = 0.006). There was no overall significant difference in victimization rates by sex: 19% of boys (363 of 1930) and 16% of girls (303 of 1837) (p = 0.628), although boys were moderately more often harmed in the 1- to 3-year-old category (20% boys; 67 of 333 children v. 13% girls; 35 of 270 children) (p < 0.020) than in the 8- to 11-year-old category (19% boys; 90 of 476 children v. 14% girls; 61 of 437 children) (p < 0.044).

Of the estimated 135 500 child-maltreatment investigations conducted in Canada in 1998, 61 156 cases involved substantiated maltreatment (Table 4).13 Of these substantiated cases, 13% involved moderate injuries or health conditions (8221 cases) and an additional 4% involved severe injuries or health conditions (2621 cases) that required medical attention. In total, some type of physical harm was noted in 668 cases in the current study sample, an estimated 10 842 substantiated investigations in Canada in 1998 and a rate of 1.73 injured maltreatment victims per 1000 children involved in cases of substantiated maltreatment.

Interpretation

The current study sample of the CIS documented some type of physical harm in 18% of substantiated investigations; 4% of substantiated investigations involved severe harm requiring medical treatment. Over two-thirds of injuries involved bruises, cuts and scrapes, few of which were severe enough to require medical attention. Although harm was noted most often in cases involving physical abuse, no harm was documented in more than half of all physical abuse cases. This somewhat surprising finding reflects the fact that physical abuse includes many situations in which parental use of force does not visibly injure the child, but the child is nevertheless considered to be at significant risk for injury. Other than medical neglect, physical harm was rarely noted for other types of maltreatment. Exposure to family violence was the primary issue of concern in a large number of cases. Despite concerns that children may be at risk for injury in such situations, physical harm was rarely noted in these cases.

Rates of severe harm tracked by the CIS are consistent with those of previous studies reporting severe harm (range 3.8%–4.6% of substantiated investigations), whereas rates of moderate-to-severe harm documented in these same studies were greater (range 36%–63% of cases).6,7,10,11 The difference in rates of moderate harm seems to be primarily due to differences in the populations studied. The study that found the highest overall rate of harm (63%) was limited to physical abuse cases only.11 In comparison, harm was noted in 43% of physical abuse cases in the CIS. In a second study that included abuse and neglect cases, physical abuse cases were counted as substantiated only if harm had been documented.7 Another possible explanation is that the proportion of cases involving moderate harm is lower in Canada than in the United States. Variations in reporting and investigation standards may explain such a difference. The reporting threshold may be lower in Canada than in the United States, and Canadian child welfare authorities may be more inclusive in what they are prepared to investigate and substantiate.

Some caution is required in interpreting the CIS findings. Ratings provided by investigating workers are based on information collected during their investigations. Although documentation of injuries is a priority in maltreatment investigations and often involves consultation with medical staff, the ratings could not be independently verified for accuracy. The CIS documented only those cases investigated by child welfare authorities; excluded from the study were unreported cases, cases reported only to the police, cases screened out before the investigation was complete, and reports on cases already open from earlier investigations. Further, this paper examines only physical harm. Emotional harm was documented in one-third of all substantiated investigations; 21% of victims had emotional problems that required some type of treatment (proportions are based on the annual CIS weighted estimates).13

The relatively low injury rates documented by the CIS raise questions about the investigative procedures that dominate the organization of child protective services and, in particular, the emphasis that has been placed on risk assessment. Many jurisdictions have developed increasingly strict investigation timelines and require the use of safety and risk assessment tools predicated on the concern that rapid intervention is required to ensure adequate protection of maltreated children. In cases of sexual abuse, in which concerns about further victimization and offenders pressuring victims to recant may exist, these response protocols seem adequately justified. Similarly, in cases in which forensic evidence requires an immediate response or there is clear evidence of risk of severe harm (e.g., shaking and battery), an emergency response is justified. However, because evidence that reported children are at high risk for severe injuries is limited — 96% of substantiated cases did not involve severe harm — some investigation priorities and procedures may need to be revised. Indeed, several jurisdictions are experimenting with differential response systems designed to transfer nonurgent cases to intake teams focusing on assessing longer-term service needs.18,19

β See related article page 919

Acknowledgments

Estimation of sampling error was completed with support from Tahany Gadalla, statistician at the Ontario Institute of Studies in Education. Editorial and research support was provided by Teresa Neves and Jasmine Siddiqi at the Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Nico Trocmé directed data collection and analysis, wrote the first draft of the article, and completed the revisions. Harriet MacMillan helped plan the analyses, co-wrote the discussion section and responded to all revisions. Barbara Fallon managed data collection, conducted the analyses, co-wrote the methodology section and responded to all revisions. Richard de Marco reviewed the data analyses, provided critical commentary on the methodology and discussion sections and responded to all revisions.

Funding for the Canadian Incidence Study was provided by Health Canada, the governments of Québec, Ontario, British Columbia and Newfoundland, and Bell Canada. Barbara Fallon is supported by a Bell Canada Child Welfare Research Unit Doctoral Fellowship. Dr. MacMillan is supported by the Wyeth-Ayerst Canada Inc. Canadian Institutes of Health Research Clinical Research Chair in Women's Mental Health, and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research on Gender and Health, Aging, Human Development, Child and Youth Health, Neuroscience, Mental Health and Addiction, and Population and Public Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Nico Trocmé, 246 Bloor St. W, Toronto ON M5S 1A1; fax 416 978-7072; nico.trocme@utoronto.ca

References

- 1.Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, Drogemueller W, Silver HK. The battered child syndrome. JAMA 1962;181(1):17-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Kocher MS, Kasser JR. Orthopaedic aspects of child abuse. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2000;8(1):10-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Claytor RN, Barth KL, Shubin CI. Evaluating child sexual abuse: observations regarding ano-genital injury. Clin Pediatr 1989;28(9):419-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Creighton SJ. An epidemiological study of abused children and their families in the United Kingdom between 1977 and 1982. Child Abuse Negl 1985;9(4):441-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hampton RL. Race, class and child maltreatment. J Comp Fam Stud 1987;18(1):113-226.

- 6.Raiha N, Soma DJ. Victims of child abuse and neglect in the US Army. Child Abuse Negl 1997;21(8):759-68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Rosenthal JA. Patterns of reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl 1988;12(2):263-71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Sedlak AJ, Broadhurst DD. Third national incidence study of child abuse and neglect. Washington: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

- 9.Sidebotham P. Patterns of child abuse in early childhood, a cohort study of the “children of the nineties.” Child Abuse Rev 2000;9(5):311-20.

- 10.Trocmé N, Brison R. Homicide and injuries due to assault and to abuse and neglect. In: For the safety of Canadian children and youth: from injury data to preventive measures. Ottawa: Health Canada; 1998. Catalogue No. H39-412-1997E.

- 11.Zuravin S, Orme J, Rebecca H. Predicting severity of child abuse injury: an empirical investigation using ordinal probit regression. Soc Work Res 1994;18(3):131-8.

- 12.Hennekens CH, Burning J. Epidemiology in medicine. Boston: Little, Brown; 1987.

- 13.Trocmé N, MacLaurin B, Fallon B, Daciuk J, Billingsley D, Tourigny M, et al. Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect. Ottawa: National Clearinghouse on Family Violence; 2001. Report no.: H49-151/2000E.

- 14.Trocmé N, Fallon B, Daciuk J, Tourigny M, Billingsley D. Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect: methodology. Can J Public Health 2001;92(4):259-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Trocmé N, McPhee D, Tam KK, Hay T. Ontario incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect. Toronto: Institute for the Prevention of Child Abuse; 1994.

- 16.Lehtonen R, Pahkinen EJ. Practical methods for design and analysis of complex surveys. Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons; 1995.

- 17.Fitzgerald R. Assaults against children and youth in the family, 1996. Juristat 1996;17(11) Ottawa: Statistics Canada; Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. Available: http://www.statcan.ca/english/IPS/Data/85-002-XIE1997011.htm (Accessed 2003 Jul 21).

- 18.English DJ, Wingard T, Marshall D, Orme M, Orme A. Alternative responses to child protective services: emerging issues and concerns. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24(3):375-88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Family and Children's Services Division. Guidelines for alternative response to treatment of child maltreatment. Minnesota: St Paul (MN): Minnesota Department of Human Services; 2000.