Clinical practice guidelines require continual reassessment in response to new information and changes in the pattern of disease. Challenges in Canada, as in all industrialized countries, include the increasing size of the elderly population and the rising prevalence of obesity and diabetes mellitus. More than 20% of Canadians will be over 65 years of age by 2011. Obesity, particularly abdominal adiposity, is associated with an increased prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and other features of the metabolic syndrome (hypertriglyceridemia, low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C] and insulin resistance). Currently, 31% of Canadian adults are obese (defined as a body mass index greater than 27 kg/m2). Type 2 diabetes is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease, and its prevalence is reaching epidemic proportions. The First Nations population, with a risk of diabetes 3 to 5 times higher than that of the general Canadian population, is at particular risk.

Because of the burden of cardiovascular disease and the high rate of death from out-of-hospital acute myocardial infarction, preventive measures are essential in order to reduce health care costs and improve the health of Canadians. The Working Group on Hypercholesterolemia and Other Dyslipidemias issued recommendations for the management and treatment of dyslipidemias in Canada in 2000.1 Since the publication of these Canadian guidelines and of the US National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel-III (NCEP ATP-III) report,2 in 2002, the findings from several important clinical trials have been reported, including those from the Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) Study,3 the Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial (VA-HIT)4 and the Heart Protection Study (HPS).5 As a result, the working group was reconvened to assess this new information and to address the increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its effect on the risk of cardiovascular disease. In this article, we summarize the working group's revised set of guidelines (see the appendix 1). (The full text of the updated recommendations is available online at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/169/9/921/DC1.) The main purpose of the guidelines is to provide primary care physicians and internists with a tool for evaluating a patient's risk of coronary artery disease as part of a routine health assessment.

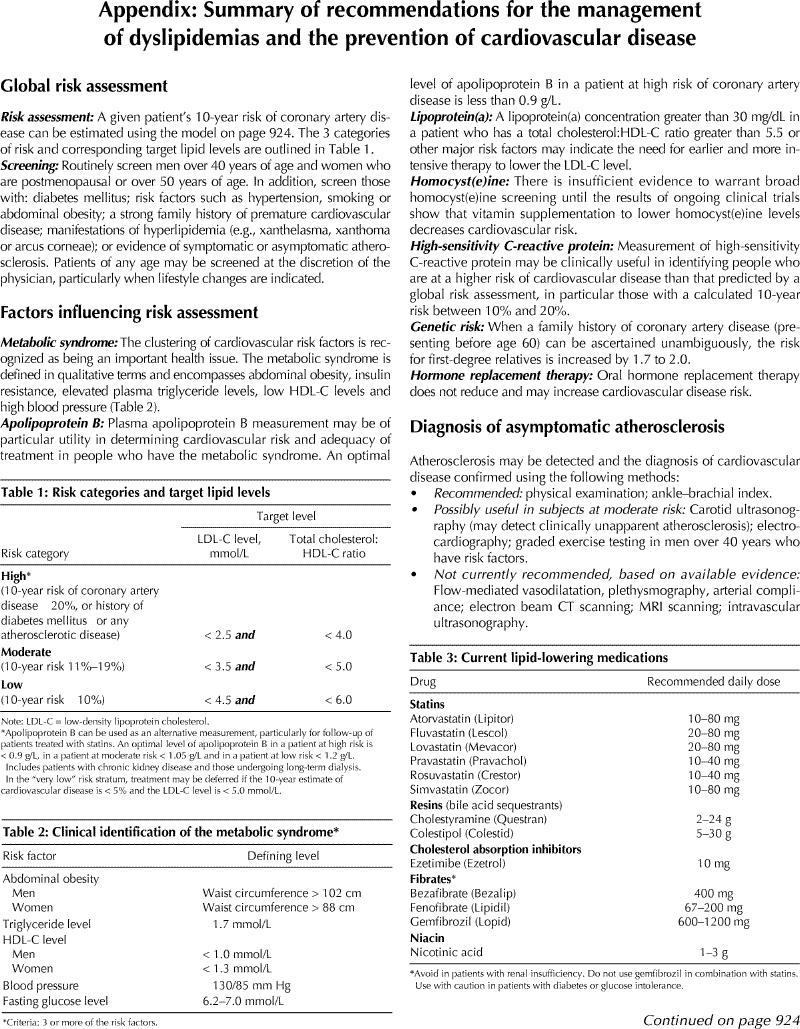

The revised guidelines have been simplified and include 3 levels of risk of coronary artery disease (high, moderate and low) and 2 treatment targets (the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C] level and the total cholesterol: HDL-C ratio). The US NCEP ATP-III guidelines also provide 3 levels of risk based on the Framingham Study equation but, in contrast to the Canadian guidelines, recommend the use of non-HDL-C levels (i.e., the sum of very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and LDL-C levels) as its secondary therapeutic goal, especially in patients with features of the metabolic syndrome. Because the total cholesterol:HDL-C ratio is a more sensitive and specific index of cardiovascular risk than total cholesterol, the working group has chosen this simple lipid ratio as a secondary goal of therapy. Topics specifically addressed in the revised guidelines include the management of patients at high risk of coronary artery disease who have an LDL-C level at target (2.5 mmol/L), the management of patients who have combined dyslipidemia and low HDL-C levels, and the noninvasive assessment of cardiovascular disease and other risk factors, including the metabolic syndrome and levels of apolipoprotein B, lipoprotein(a), homocyst(e)ine and C-reactive protein.

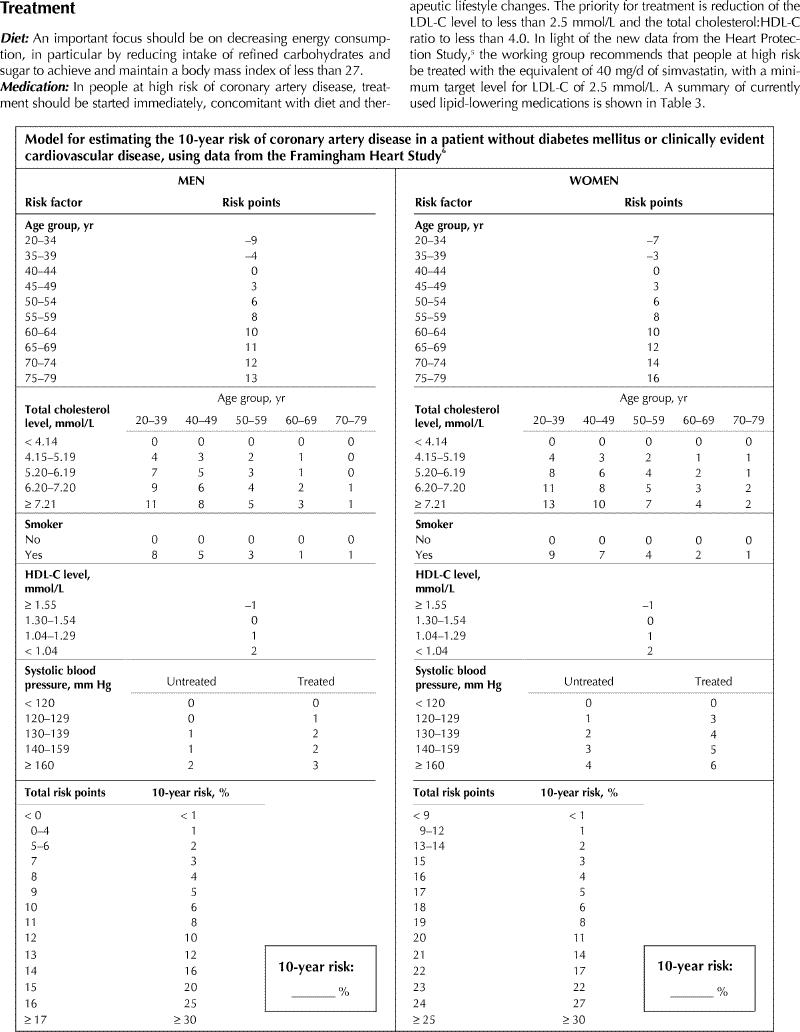

For the 2000 Canadian guidelines, the Framingham Study risk equations used by the working group were those published by Grundy and colleagues.6 The NCEP ATP-III used an adaptation of Framingham data based on the estimated 10-year risk of “hard cardiac endpoints.” These include death from coronary artery disease and nonfatal myocardial infarction. The NCEP ATP-III risk estimate tables also adjust certain risk factors (e.g., total cholesterol level and smoking status) for age and correct for the effect of treatment on blood pressure measurement. This represents a refinement to the previously published risk assessment tables. For these reasons and in order to harmonize cardiovascular risk assessment across North America, the working group has used the NCEP ATP-III risk estimation algorithm2 in the revised guidelines. The presence of diabetes is generally considered as a coronary artery disease risk equivalent.

In addition to their attempt to harmonize cardiovascular risk assessment across North America, the updated guidelines will provide a background recommendation for Canadian specialty organizations such as the Canadian Hypertension Society, the Canadian Diabetes Association, the Dietitians of Canada and the Canadian Society of Atherosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. The guidelines were reviewed by 2 expert panels that included recognized specialists in the areas of cardiovascular disease prevention, lipid metabolism and diabetes as well as primary care physicians. In addition, several medical professional associations had an opportunity to review and comment on this document.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the following for their advice and comments on the recommendations: Dr. Jean Bergeron, Laval, Que.; Dr. Ross Feldman, Robarts Research Institute, London, Ont.; Dr. Steven Grover, McGill University, Montréal, Que.; Dr. Milan Gupta, Hamilton, Ont.; Dr. Lawrence Leiter, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.; Dr. Garry Lewis, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.; Dr. G.B. John Mancini, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC; and Dr. Bruce Sussex, Memorial University, St. John's, Nfld. We also thank Dr. Helen Stokes, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ont., and Kristi Adamo and Penlope Turton, Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, Ont., for their help in writing the manuscript.

Appendix 1.

Appendix 1. Continued.

Footnotes

The full text of the updated recommendations is available online (www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/169/9/921/DC1)

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Each of the authors contributed substantially to the drafting and revising of the article. All approved the final version submitted for publication.

Competing interests: The authors did not receive financial support from pharmaceutical companies for their work in developing these recommendations and producing this report. All have received speaker fees from various drug companies, including those that manufacture drugs used to treat dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease; Drs. Genest, Frohlich and McPherson have been members of advisory boards of various drug companies; and Drs. Fodor, Frohlich and McPherson have received travel expenses from one or more drug companies to attend scientific meetings.

Correspondence to: Dr. Jacques Genest, Division of Cardiology, McGill University Health Centre, Royal Victoria Hospital, 687 Pine Ave. W, Montréal QC H3A 1A1; fax 514 843-2813; jacques.genest@muhc.mcgill.ca

References

- 1.Fodor JG, Frohlich JJ, Genest JJG Jr, McPherson PR, for the Working Group on Hypercholesterolemia and Other Dyslipidemias. Recommendations for the management and treatment of dyslipidemia: report of the Working Group on Hypercholesterolemia and Other Dyslipidemias. CMAJ 2000;162(10):1441-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Grundy SM, Becker D, Clark LT, on behalf of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health; 2002. Available: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/index.htm (accessed 2003 Sept 26).

- 3.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, Ganz P, Oliver MF, Waters D, et al, on behalf of the Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) Study Investigators. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285(13):1711-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Robins SJ, Collins D, Rubins HB. Relation of baseline lipids and lipid changes with gemfibrozil to cardiovascular endpoints in VA-High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial (VA-HIT). Circulation 1999;100(18)(Suppl I):I-238.

- 5.MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:7-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Grundy SM, Pasternak R, Greenland P, Smith S Jr, Fuster V. Assessment of cardiovascular risk by use of multiple-risk-factor assessment equations: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation 1999;100(13):1481-92. [DOI] [PubMed]