Abstract

In this report, we have assessed the lineage relationships and cytokine dependency of natural killer (NK) T cells compared with mainstream TCR-αβ T cells and NK cells. For this purpose, we studied common γ chain (γc)-deficient mice, which demonstrate a selective defect in CD3− NK cell development relative to conventional TCR-αβ T cells. NK thymocytes differentiate in γc− mice as shown by the normal percentage of TCR Vβ8+ CD4−CD8− cells and the normal quantity of thymic Vα14–Jα281 mRNA that characterize the NK T repertoire. However, γc-deficient NK thymocytes fail to coexpress the NK-associated markers NKR-P1 or Ly49, yet retain characteristic expression of the cytokine receptors interleukin (IL)-7Rα and IL-2Rβ. Despite these phenotypic abnormalities, γc− NK thymocytes could produce normal amounts of IL-4. These results define a maturational progression of NK thymocyte differentiation where intrathymic selection and IL-4–producing capacity can be clearly dissociated from the acquisition of the NK phenotype. Moreover, these data suggest a closer ontogenic relationship of NK T cells to TCR-αβ T cells than to NK cells with respect to cytokine dependency. We also failed to detect peripheral NK T cells in these mice, demonstrating that γc-dependent interactions are required for export and/or survival of NK T cells from the thymus. These results suggest a stepwise pattern of differentiation for thymically derived NK T cells: primary selection via their invariant TCR to confer the IL-4–producing phenotype, followed by acquisition of NK-associated markers and maturation/export to the periphery.

NK T cells are a specialized subset of T cells that share surface markers with the NK cells and have unique properties with respect to their TCR diversity and specificity, as well as their ultimate biological functions (1–3). NK T cells comprise both CD4−CD8− (double negative, DN) and CD4+ TCR-αβ bearing T cells (4, 5), which coexpress a cluster of NK cell markers, including receptors of the C-lectin Ly49 and NKR-P1 (including the NK1.1 antigen) families (1–3, 6, 7). NK T cells express high levels of the IL-2Rβ molecule, a shared cytokine receptor chain used by IL-2 and IL-15, which is also found on NK cells and TCR-γδ T cells, but at low levels on conventional TCR-αβ T cells (8). Moreover, although the level of TCR expression on conventional T cells is high, NK T cells express intermediate TCR levels (TCR-αβint). The TCRαβ repertoire of NK T cells is markedly restricted: TCR-β chain usage includes Vβ8, Vβ7, and Vβ2, whereas the TCR-α chain is mostly an invariant α chain using the Vα14 and Jα281 segments with a conserved junctional sequence (9, 10). The limited TCR-αβ diversity of NK T cells suggested that these cells interact with a similarly nonpolymorphic ligand (4, 10). Studies using T cell hybridomas derived from NK T cells have clearly identified the nonpolymorphic MHC class Ib CD1 molecule as the ligand recognized by these peculiar TCR (11). NK T cells are remarkable for their ability to produce large amounts of cytokines after TCR stimulation (12), notably IL-4 (12, 13). This prompt IL-4 production by NK T cells has suggested a model in which these cells are one of the major determining factors influencing the final TH1/TH2 profile of immune responses (13, 14).

The potential to produce IL-4 and the NK phenotype are two characteristic properties of NK T cells that are likely acquired during their selection by CD1 at an early ontogenic stage (15). This hypothesis has been strengthened by recent studies of Vα14–Jα281 transgenic mice (16), which have increased numbers of NK T cells, increased IL-4 production and augmented baseline levels of IgE and IgG1 (16). Still, a role for the NK-associated molecules during the selection of NK T cells has not been excluded, and a coreceptor function for the NK1.1 molecule has been suggested (2) based on the presence of the amino acid Cys–X–Cys– Pro motif in the NK1.1 cytoplasmic domain (17). This motif was first identified in the CD4 and CD8-α coreceptors as the region that specifically interacts with p56lck, a tyrosine kinase whose association with the CD4 or CD8 coreceptors is important for optimal T cell activation (18).

A separate question in the development of NK T cells involves the role of cytokines. The common γ chain (γc)1, is a critical component of the receptors for IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15. γc-deficient mice have abnormal lymphoid development, with a complete absence of NK cells, TCR-γδ T cells, and gut-associated intraepithelial lymphocytes (19). In contrast, TCR-αβ T cells and B cells are present, albeit in reduced numbers. Therefore, γc− mice represent a useful system to assess lineage relationships between various lymphoid subpopulations. In this report, we have studied NK T cell development in γc− mice. The presence of NK thymocytes in γc− mice suggest a closer ontogenic relationship of NK T cells to mainstream TCR-αβ T cells than to NK cells with respect to cytokine dependency. Based on our phenotypic and functional analyses of γc− NK thymocytes, we propose and discuss a stepwise model of NK T cell differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Mice deficient for the common cytokine receptor γ chain, γc (initially identified as the IL-2 receptor γc, reference 19), were maintained in our conventional animal facility and were of a mixed background (129/Ola/BALB/c or 129/Ola/BL/6). For the analysis of NK-associated markers including NK1.1 and Ly49 members, female mice heterozygous for the X-linked γc mutation (from the fourth backcross to BL/6 with confirmed NK1.1 and Ly49 expression) were mated to normal BL/6 males and the subsequent γc+ or γc− male mice were analyzed for NK1.1 expression. Mice were analyzed between 4 and 10 wk of age.

Cell Preparation and FACS® Analysis.

Thymocyte and splenocyte (red cell–depleted) suspensions were prepared aseptically in HBSS after pressing through sterile mesh filters. Liver lymphocytes were isolated using discontinuous Percoll gradients (20) with minor modifications. Cells were stained using combinations of directly conjugated mAbs: FITC–anti-TCR-αβ (clone H57), biotin–anti-heat-stable antigen (HSA, clone J11d), and biotin– anti-Vβ8 (clone F23.1); FITC–anti-IL-7Rα chain (21) (purified and locally conjugated by standard methods), PE–anti-HSA, biotin–anti-TCR-αβ, FITC–anti-IL-2Rβ, FITC–anti-Ly49C, and PE–anti-NK1.1 (all from PharMingen, San Diego, CA); PE–antiCD4, FITC–anti-CD8, and Tricolor–streptavidin (Caltag Laboratories, San Francisco, CA). FITC–anti-Ly49A (JR9-319) was the gift of J. Roland (Institute Pasteur, Paris, France). Three-color immunofluorescence analysis was performed using a FACScan® flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson & Co., Mountain View, CA) and analyzed using CellQuest software.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted with acid– guanidinium (22) and ethanol-precipitated with the addition of 5 μg of glycogen before resuspension in 20 μl of DEPC water. Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR amplification were carried out as previously described (23) using oligonucleotides specific for Cα, Vα14, and Jα281 (10). It should be stressed that because there is no allelic exclusion for the α chain locus of the TCR (24), only enrichment for a certain VJ combination in a peculiar sample can be detected by PCR analysis using PCR primers specific for Vα and Jα segments. If the amount of starting material is high enough (more than ∼2 × 104 cell equivalents), in samples that do not contain Vα14–Jα281 invariant α chains (such as those from β2microglobulin [β2m]−/− mice), there is always a background signal related to the amplification of nonselected out of frame and/or polymorphic TCR-α chains using the same VJ combination. Indeed, polyclonal sequencing of such Vα14–Jα281 PCR products demonstrated their polymorphism (reference 10; data not shown). In the kinetic PCR method we are using, if one considers two samples containing the same amount of Cα, a shift of n cycles along the x axis of the two amplification curves represents an ∼1.8nfold difference in Vα14–Jα281 expression.

In Vivo and In Vitro IL-4 Production.

Administration of purified anti-CD3 (clone 145-2C11; 2 μg i.v.) and subsequent in vitro culture of splenocyte suspensions for IL-4 production were performed exactly as described (13). To evaluate cytokine production following stimulation in vitro, CD8− thymocytes were purified after a one-step killing with anti-CD8 mAb (TiB-211; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) plus low-toxic M rabbit complement (Cederlane Laboratories, Hornby, Canada). Viable cells were recovered by centrifugation over a density gradient. CD8− thymocytes (3 × 105) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium, 10% FBS, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM glutamine with 3 × 104 antigen-presenting cells and soluble anti-CD3 at 5 μg/ml in a total volume of 0.4 ml for 48 h, with or without exogenous cytokines (thymic stromal cell–derived lymphopoietin, TSLP [25], at 10 ng/ml). Supernatants were harvested and IL-4 content measured using the CT.4S cell line. Responses were compared with those elicited by known amounts of murine IL-4.

Results and Discussion

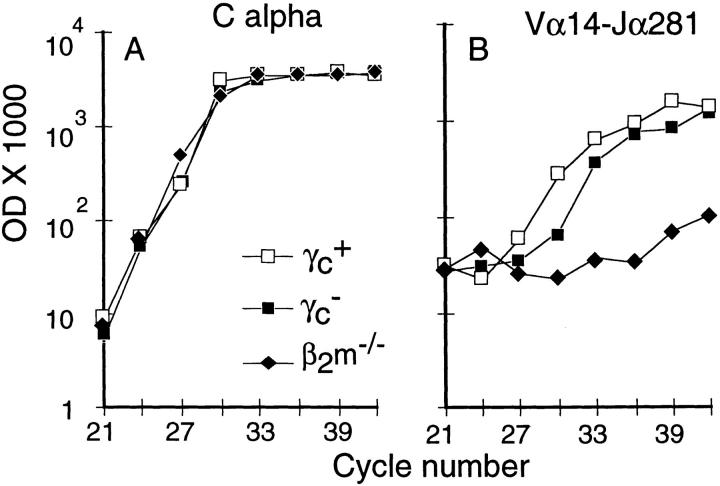

NK Thymocytes Develop in the Absence of γc.

A semiquantitative PCR approach (23) was used to enumerate NK T cells by exploiting the fact that these cells exhibit a restricted TCR-α chain repertoire, using the Vα14 segment joined to Jα281 (10). We quantitated the amounts of Vα14–Jα281 TCR-α chain in CD8− (CD4−CD8− [DN] and CD4+ single-positive [SP]) thymocytes from γc+, γc−, and β2m−/− mice. β2m−/− cells were used as control as it has been previously shown that NK T cells require the β2m-associated CD1 molecules in order to be selected efficiently (4, 5, 10, 11, 15). As shown in Fig. 1, Cα transcripts were found equally in all three cDNA preparations. The amount of Vα14–Jα281 mRNA was similar in both γc+ and γc− thymi (within threefold) and largely increased relative to β2m−/− thymi, which lack NK T thymocytes. Direct polyclonal sequencing the Vα14–Jα281 amplicons from γc+ and γc− thymi verified the presence of the canonical CDR3 motif, whereas β2m−/− amplicons were polymorphic (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Vα14–Jα281 invariant α chain is normally expressed in mature thymocytes of γc− mice. Duplicates samples of 5 × 105 CD8− thymocytes were obtained from the indicated mice and RNA extracted. After reverse transcription, the indicated genes were amplified and the amount of amplicons quantified at the indicated cycle. Averaged duplicate values are shown. Representative of three independent experiments.

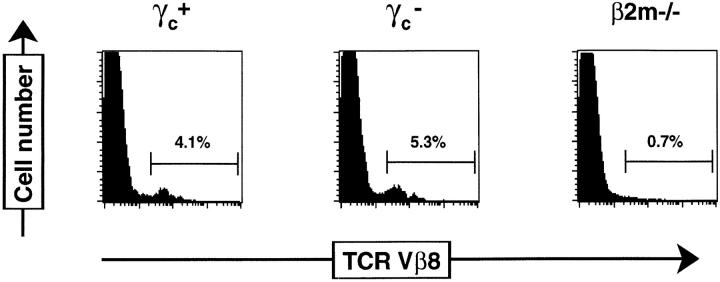

The presence of γc− NK T thymocytes was confirmed by analysis of DN thymocytes for the expression of Vβ8 (Fig. 2). The TCR-β repertoire of DN NK T cells is highly restricted, with ∼50% of cells using Vβ8 (4, 7, 10). DN thymocytes from both γc+ and γc− mice contained a population of Vβ8+ cells (∼5%), which was not detected in DN thymocytes from β2m−/− mice. Percentages of Vβ8+ cells amongst mature (HSAlo) DN thymocytes were also comparable between γc+ (30.3 ± 7.8%) and γc− (20.7 ± 4.7%) mice (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that NK T cells are found at the same relative frequency in γc− thymi as in γc+ thymi, although their absolute numbers are reduced by 20-fold in parallel with the overall decrease in thymopoiesis seen in γc− mice (19). These results suggest that generation of NK T cells after interactions with CD1 molecules can proceed in the absence of γc. In this way, selection of NK T cells parallels that of the conventional CD4+ and CD8+ TCR-αβ T cells, which can be generated independent of γc (19, 26; DiSanto, J.P., unpublished data). The ability of NK thymocytes to develop in the absence of γc clearly distinguishes this lymphoid subset from classical NK cells, which have an absolute requirement for γc-dependent interactions in their development (19).

Figure 2.

γ c − thymocytes contain normal proportions of DN TCR– Vβ8-expressing cells. Thymocytes from γc+, γc−, and β2m−/− mice were stained with CD8–FITC, CD4–PE, and F23.1–biotin followed by Tricolor streptavidin. Histograms show Vβ8 expression on gated DN (CD4−CD8−) thymocytes.

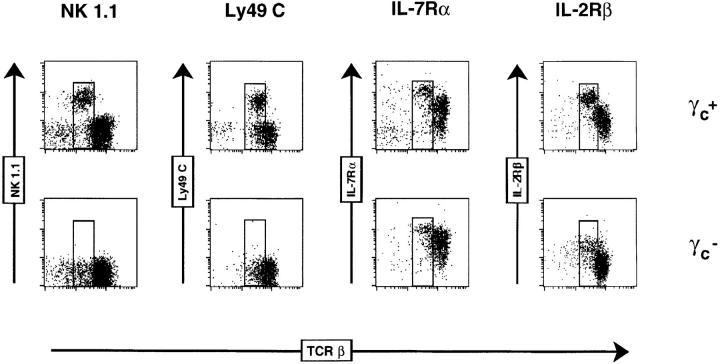

Dissociation Between Selection and Phenotype of NK T Cells in γc− Mice.

NK T thymocytes express a unique constellation of cell surface markers, including intermediate density TCR-αβ (TCR-αβint) and coexpression of NK-associated antigens, including members of the NKR-P1 and Ly49 families (1–3). Next, we investigated whether NK T thymocytes from γc− mice maintained this particular phenotype using mice on the C57BL/6 background. Mature thymocytes (expressing low levels of heat-stable antigen, HSAlo) were examined for a variety of markers in combination with TCR-β chain expression. Thymi from BL/6 γc+ mice contained a subpopulation of TCR-αβint cells expressing the NK1.1 marker (Fig. 3). In γc+ mice, a fraction of the NK1.1+ thymocytes coexpressed Ly49C or Ly49A, and all cells were positive for the IL-2Rβ and IL-7Rα chains (Fig. 3; data not shown). In contrast, no NK1.1+ or Ly49C+ cells were found in thymi from BL/6 γc− mice, although TCR-αβint cells were clearly detectable (Fig. 3). In γc− mice, these TCR-αβint cells expressed high levels of IL-7Rα (like their γc+ counterparts) and somewhat reduced levels of IL-2Rβ (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Phenotype of NK thymocytes. Dot plots show expression of NK1.1, Ly49C, IL-7Rα or IL-2β as a function of TCR-β chain expression on mature (HSAlo) thymocytes from γc+ or γc− BL/6 mice. Boxed regions indicate the NK thymocytes that have characteristic TCR-βint expression.

These results, together with the Vα14–Jα281-specific PCR data and expression of Vβ8 on DN thymocytes, demonstrate that NK T cells are present in the thymus of γc− mice, although they do not express the NK-associated markers. This suggests that the generation and selection of NK thymocytes can be dissociated from the acquisition of the NKR-P1 and Ly49 markers, and that the NK phenotype is a contingent phenomenon, which alone cannot be used to define a particular lineage. Concerning the potential function of NKR-P1 molecules as coreceptors for the recognition of CD1 during selection of NK T cells (2), our results show that NKR-P1 expression is not strictly required for positive selection of NK T cells on CD1, although we cannot rule out that additional interactions are afforded to the selection process by NKR-P1 molecules. The coabsence of Ly49 family molecules on γc− NK thymocytes is consistent with the NK-associated markers being encoded by their genetically linked loci or the NK gene complex (27), the regulation of which appears to ensure the simultaneous expression of negative (Ly49) and positive (NKR-P1) signaling molecules on NK cells and NK T cells.

Because NK T cells are selected to a similar degree in the thymus of γc− mice as in γc+ mice, and in the absence of NK-associated markers, the major determinant of NK T cell selection remains the invariant Vα14–Jα281 TCR-α chain paired with the restricted TCR-β chains (10, 16). Although we cannot rule out a lower avidity reaction in the absence of NKR-P1 or Ly49, we would suggest that the expression of NK-associated markers are probably the result of additional maturation events after selection, rather than being required for the selection process itself. This also argues against the hypothesis that would make of the NK T cells a peculiar lineage with a correlated expression of the NK markers together with the Vα14–Jα281 invariant α chain. Indeed, the invariant α chain appears selected at the protein level rather than being produced through a genetic program that selectively recombines Vα14 and Jα281 (10).

Production of IL-4 by γc− NK Thymocytes.

The unique ability of NK T cells to produce IL-4 after TCR triggering has been one main characteristic of this lymphoid subset (1, 13, 14). When CD8− thymocytes from γc+ or γc− mice were cultured in vitro with soluble CD3 and antigen-presenting cells, IL-4 release could be detected in the supernatants from γc+ and γc− cells (Table 1), although IL-4 production from γc− cells was relatively weak. We hypothesized that one reason for the low IL-4 production from γc− thymocytes might relate to poor cell viability during the culture period (48 h). We have recently identified a novel cytokine, TSLP, which shares many functional similarities to IL-7 (25), and uses the IL-7Rα chain, but not the γc chain for signaling, which can maintain γc+ and γc− thymocytes in vitro (Park et al., unpublished data). As both γc+ and γc− NK thymocytes expressed the IL-7Rα (Fig. 3), we added TSLP to maintain thymocytes during the in vitro assay of IL-4 production. Exogenous TSLP substantially increased the amount of IL-4 produced from γc− NK thymocytes, approximating the levels produced by γc+ cells under these conditions (Table 1). Addition of TSLP to control thymocyte cultures from β2m−/− mice did not result in the generation of IL-4. Therefore, TSLP can effectively substitute for IL-7 in stimulating NK thymocytes in vitro (28). These results are in accord with the recent observations in IL-7 knockout mice, in which NK thymocytes develop but demonstrate a functional defect in IL-4 production after CD3 stimulation (29). Exogenous IL-7 was able to restore the IL-4 response in vitro (29). NK thymocytes from γc− mice also manifest abnormal IL-4 production in vitro in the absence of IL-7Rα engagement; however, this can be restored with TSLP (Table 1).

Table 1.

IL-4 Production from NK T Cells: Production of IL-4 from In Vitro–stimulated Thymocytes

| Experiment | Cells | IL-4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3 + APC | CD3 + APC + TSLP | |||||

| U/ml | ||||||

| 1 | None | 0 | 0 | |||

| CD8− γc+ | 70 | 120 | ||||

| CD8− γc− | 20 | 110 | ||||

| 2 | CD8− β2m−/− | <5 | 20 | |||

| CD8− γc+ | 150 | 300 | ||||

| CD8− γc− | 20 | 150 | ||||

| 3 | CD8− β2m−/− | ND | 4 | |||

| CD8− γc+ | ND | 180 | ||||

| CD8− γc− | ND | 180 | ||||

NK thymocytes were isolated and stimulated as described in Materials and Methods. Mice received 2 μg of anti-CD3 intravenously and splenocytes were prepared as described (13). IL-4 bioactivity was assayed using the CT.4S indicator line.

The property of IL-4 production by NK T cells is likely related to the selection by CD1 at a particular early ontogenic stage through the invariant Vα14–Jα281 chain paired with Vβ2, Vβ7, or Vβ8. This concept is supported by recent observations using Vα14–Jα281 transgenic mice, which demonstrate an increased frequency of IL-4–producing NK T cells resulting in increased basal levels of serum IgG1 and IgE (16). Our results are consistent with the idea that positive selection of the Vα14–Jα281-bearing TCRs confers the IL-4–producing phenotype. Furthermore, we demonstrate that this unique ability of NK T cells to secrete IL-4 is not dependent on the expression (and therefore function) of the NK-related molecules.

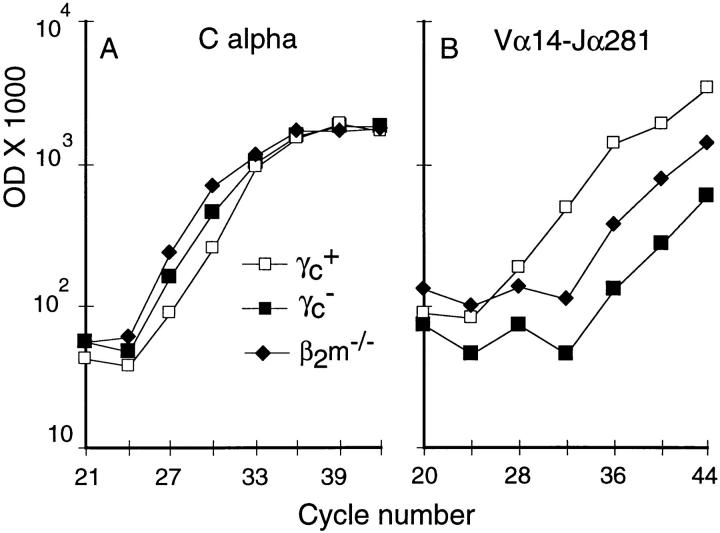

Absence of NK T Cells in the Periphery of γc− Mice.

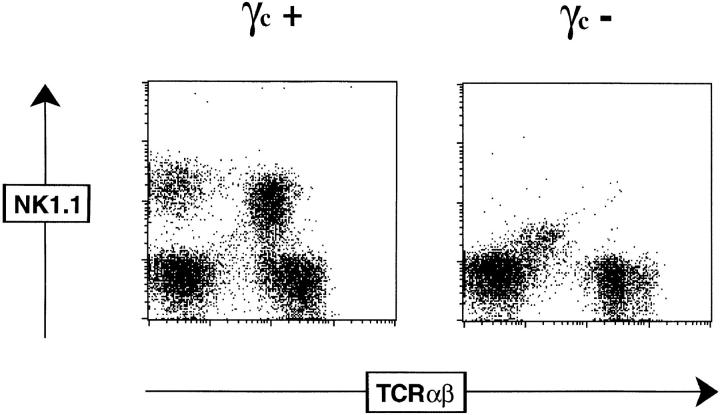

Next, we examined whether γc− NK thymocytes, despite their phenotypic abnormalities, would be able to attain their preferential localizations in the periphery. NK T cells normally comprise a small percentage of the lymphocytes present in the spleen and lymph nodes (1–3); however, these cells are abundant in the liver (20, 30). To quantitate peripheral NK T cells, lymphocytes from γc+, γc−, or β2m−/− mice were isolated from the liver and spleen and the amount of Vα14–Jα281 mRNA was determined. NK T cells were clearly present in the liver and spleens of γc+ mice (Fig. 4; data not shown) as evidenced by the presence of Vα14– Jα281+ mRNA. In contrast, levels of Vα14–Jα281+ mRNA from γc− liver and spleen preparations were at or below that of β2m−/− mice (which lack NK T cells) and well below that of γc+ controls (at least 200-fold less). Polyclonal sequencing of Vα14–Jα281 amplicons from γc+, γc−, or β2m−/− samples showed an invariant sequence only in the γc+ samples (data not shown). Flow cytometric analyses confirmed the presence of NK1.1+ TCR-αβint cells in intrahepatic lymphocytes from γc+ mice, which were not detected in preparations from γc− mice (Fig. 5). Lastly, in vivo administration of anti-CD3 antibodies stimulated IL-4 release from cultured γc+ splenocytes, whereas no IL-4 production could be detected in splenocyte cultures from γc− mice (Table 2). Taken together, these results demonstrate an absence of NK T cells in the liver and spleen of γc− mice.

Figure 4.

Vα14–Jα281 invariant α chain is absent from the liver of γc− mice. Duplicates samples of 3 × 105 liver lymphocytes were obtained from the indicated mice and processed as indicated in Fig. 1. It should be noticed that the amount of Cα is lower in the γc+ preps. The differences in Vα14–Jα281 amounts between γc+ and β2m−/− samples is at least 100-fold (5+3 cycles) and between γc+ and γc− at least 200-fold (7+2 cycles). Representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Phenotype of liver NK-T cells. Dot plots show expression of NK1.1 versus TCR-β expression on isolated liver lymphocytes from γc+ or γc− BL/6 mice.

Table 2.

IL-4 Production from NK T Cells: Production of IL-4 after CD3 Injection In Vivo

| Experiment | Mouse | IL-4 from cultured splenocytes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U/ml | ||||

| 1 | γc+ no.1 | 72 | ||

| γc+ no.2 | 64 | |||

| γc− no.1 | <5 | |||

| 2 | γc+ no.1 | 62 | ||

| γc+ no.2 | 50 | |||

| γc− no.1 | <5 | |||

| γc− no.2 | <5 |

Our results suggest that one or a combination of IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, or IL-15 is necessary for intrathymic maturation and the export/survival of the NK T cells to the peripheral lymphoid organs. The coexpression of IL-7Rα and IL-2Rβ chains on NK thymocytes suggest that IL-2, IL-7, and/or IL-15 may be important in the final differentiation of these cells. Although IL-2–deficient mice have reduced numbers of NK cells (31), NK thymocytes are present in IL-2−/− mice and have normal expression of the NKR-P1 and IL-2Rβ. (Bendelac, A., personal communication). Moreover, IL-7–deficient mice display normal percentage of thymic and splenic NK T cells with a normal phenotype (29), and we have not detected a decrease in Vα14–Jα281 transcripts in the thymus, spleen and liver of IL-2−/−, IL-4−/−, or IL-7−/− mice compared with wildtype controls (Lantz, O., and J.P. DiSanto, unpublished data). Taken together, these results fail to demonstrate the essential role of either IL-2, IL-4, or IL-7 in the final maturation and export of NK thymocytes. However, functional cytokine redundancy (the use of IL-15 in the absence of IL-2, or TSLP in the absence of IL-7) may allow these processes to occur. Further studies using IL-2Rβ–deficient mice (which can be considered as deficient in IL-2 and IL-15) (32) and IL-7Rα-deficient mice (which inactivate IL-7 and TSLP) (33) should help to elucidate the γc-dependent interactions required for induction of NKR-P1 and Ly49 antigens on NK T cells and their export into the periphery.

Lineage Relationships and Differentation of NK T Cells.

Our results suggest a stepwise differentiation of NK T cell which parallels that of mainstream TCR-αβ development. This is supported by the similarities between these two lymphoid subsets: (a) both derive from a pool of early precursors requiring γc-dependent cytokines, because both are reduced in absolute numbers by 20-fold in γc− mice; (b) although NK T cells are selected on CD1 molecules and conventional T cells by classical MHC molecules, both types of developing thymocytes exhibit TCR selection mechanisms that are independent of γc–cytokine interactions. Thus, in contrast with classical NK cells, which fail to develop in γc− mice, NK T cells appear more closely related to conventional TCR-αβ T cells. Complementary results from Arase et al. (34) showed that NK1.1+ TCR-αβ T cells, as well as mainstream αβ T cells, are absent in CD3-ζ-deficient mice, whereas NK cells were present.

Therefore, we favor a model of NK T cell development in which recognition of CD1 at a certain stage of thymic ontogeny (double-positive cortical thymocyte?) induces a particular development program with the ability to secrete IL-4 and the potential to express NK markers. The final acquisition of these NK markers (including members of the NKR-P1 and Ly49 families) would require additional intrathymic maturation involving γc-dependent cytokine interactions. We would hypothesize that induction of NK-associated markers on NK thymocytes might require signaling through the IL-2Rβ (either IL-2 or IL-15), which despite the expression of IL-2Rβ on γc− NK thymocytes would not proceed in the absence of γc. It is not known whether the absence of peripheral NK T cells in γc− mice is related to (a) the absence of the NK markers, which would prevent their export to the periphery, (b) incomplete maturation not related to the NK phenotype, or (c) to their nonsurvival in the periphery due to their inability to respond to γc-dependent lymphokines. Furthermore, the precise molecular mechanisms that allow a TCR-mediated signal to induce the acquisition of the NK markers or the ability to produce IL-4 only at a peculiar ontogenic stage remain to be defined.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Park (Immunex, Seattle, WA) for providing recombinant TSLP. We are indebted to D. GuyGrand and B. Rocha for discussions and for reviewing the manuscript, and to R. Murray (DNAX, Palo Alto, CA) and A. Bendelac for sharing unpublished results.

This work was supported by grants from the Association de la Recherche Contre la Cancer to O. Lantz and from the Ministère de la Recherche et de la Technologie (MRT) and the Institut National de la Santé de la Recherche Medicale (INSERM) to J.P DiSanto.

Footnotes

1 Abbreviations used in this paper: DN, double negative; γc, common γ chain; HSA, heat-stable antigen; TSLP, thymic stromal cell–derived lymphopoietin.

References

- 1.Bendelac A. Mouse NK1+T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:367–374. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald HR. NK1.1+ T cell receptor–alpha/ beta+cells: new clues to their origin, specificity and function. J Exp Med. 1995;182:633–638. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bix M, Losksley RM. Natural T cells: cells that co-express NKRP-1 and TCR. J Immunol. 1995;155:1020–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendelac A, Killeen N, Littman DR, Schwartz RH. A subset of CD4+thymocytes selected by MHC class I molecules. Science (Wash DC) 1994;263:1774–1778. doi: 10.1126/science.7907820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coles MC, Raulet DH. Class I dependence of the development of CD4+CD8− NK1.1+thymocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;180:395–399. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahama Y, Sharrow SO, Singer A. Expression of an unusual T cell receptor (TCR)–Vβ repertoire by Ly-6C+ subpopulations of CD4+ and/or CD8+ thymocytes. Evidence for a developmental relationship between Ly-6C+ thymocytes and CD4−CD8− TCR-αβ+thymocytes. J Immunol. 1991;147:2883–2891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arase H, Arase N, Ogasawara K, Good RA, Onoé K. An NK1.1+ CD4+8− single-positive thymocyte subpopulation that expresses a highly skewed T-cell antigen receptor Vβfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6506–6510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka T, Tsudo M, Karasuyama H, Kitamura F, Kono T, Hatakeyama M, Taniguchi T, Miyasaka M. A novel monoclonal antibody against murine IL-2 receptor beta-chain. Characterization of receptor expression in normal lymphoid cells and EL-4 cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:2222–2230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayakawa K, Lin BT, Hardy RR. Murine thymic CD4+ T cell subsets: a subset (Thy0) that secretes diverse cytokines and overexpresses the Vβ8 T cell receptor gene family. J Exp Med. 1992;176:269–274. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lantz O, Bendelac A. An invariant T cell receptor alpha chain is used by a unique subset of major histocompatibility complex class I–specific CD4+ and CD4−8−T cells in mice and humans. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1097–1106. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bendelac A, Lantz O, Quimby ME, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR, Brutkiewicz RR. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+T lymphocytes. Science (Wash DC) 1995;268:863–865. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zlotnik A, Godfrey DI, Fischer M, Suda T. Cytokine production by mature and immature CD4−CD8− T cells. Alpha beta–T cell receptor+ CD4−CD8−T cells produce IL-4. J Immunol. 1992;149:1211–1215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimoto T, Paul WE. CD4+ NK1-1+T cells promptly produced IL-4 in response to in vivo challenge with anti-CD3. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1285–1295. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshimoto T, Bendelac A, Watson C, Hu LJ, Paul WE. Role of NK1.1+T cells in a TH2 response and in immunoglobulin E production. Science (Wash DC) 1995;270:1845–1847. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendelac A. Positive selection of mouse NK1+T cells by CD1-expressing cortical thymocytes. J Exp Med. 1995;182:2091–2096. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bendelac A, Hunziker R, Lantz O. Increased IL-4 production and IgE levels in transgenic mice overexpressing NK1 T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1285–1293. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giorda R, Trucco M. Mouse NKR-P1: a family of genes selectively coexpressed in adherent lymphokineactivated killer cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:1701–1708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw AS, Chalupny J, Whitney JA, Hammond C, Amrein KE, Kavathas P, Sefton BM, Rose JK. Short related sequences in the cytoplasmic domains of CD4 and CD8 mediate binding to the amino-terminal domain of the p56lck tyrosine protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1853–1862. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiSanto JP, Müller W, Guy-Grand D, Fischer A, Rajewsky K. Lymphoid development in mice with a targeted deletion of the interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:377–381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otheki T, MacDonald HR. Major histocompatibility complex class I related molecules control the development of CD4+CD8− and CD4−CD8− subsets of natural killer 1.1+ T cell receptor-α/β+cells in liver of mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:699–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sudo T, Nishikawa S, Ohno N, Akiyama N, Tamakoshi M, Yoshida H, Nishikawa SI. Expression and function of the interleukin 7 receptor in murine lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9125–9129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol– chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alard P, Lantz O, Sebagh M, Calvo CF, Weill D, Chavanel G, Senik A, Charpentier B. A versatile ELISA–PCR assay for mRNA quantitation from a few cells. Biotechniques. 1993;15:730–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malissen M, Trucy J, Jouvin-Marche E, Cazenave PA, Scollay R, Malissen B. Regulation of TCR α and β gene allelic exclusion during T-cell development. Immunol Today. 1992;13:315–322. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friend SL, Hosier S, Nelson A, Foxworthe D, Williams DE, Farr A. A thymic stromal cell line supports in vitro development of surface IgM+B cells and produces a novel growth factor affecting B and T lineage cells. Exp Hematol. 1994;22:321–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiSanto JP, Guy-Grand D, Fisher A, Tarakhovsky A. Critical role for the common cytokine receptor gamma chain in intrathymic and peripheral T cell selection. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1111–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yokoyama WM. Natural killer cell receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:110–120. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vicari A, De Moraes MC, Gombert JM, Dy M, Penit C, Papiernik M. Interleukin 7 induces preferential expansion of Vβ 8.2+CD4−8− and Vβ 8.2+CD4+8−murine thymocytes positively selected by class I molecules. J Exp Med. 1994;180:653–661. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vicari AP, Herbelin A, Leite-de-Moraes MC, von Freeden-Jeffry U, Murray R, Zlotnik A. NK1.1+T cells from IL-7 deficient mice have a normal distribution and selection but exhibit impaired cytokine production. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1759–1766. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.11.1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seki S, Kono DH, Balderas RS, Theofilopoulos AN. V beta repertoire of murine hepatic T cells. Implication for selection of double negative alpha beta+T cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:637–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kundig TM, Schorle H, Bachmann MF, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM, Horak I. Immune responses in interleukin-2-deficient mice. Science (Wash DC) 1993;262:1059–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.8235625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki H, Kündig TM, Furlonger C, Wakeham A, Timms E, Matsuyama T, Schmits R, Simard JJ, Ohashi PS, Griesser H, Taniguchi T, Paige CJ, Mak TW. Deregulated T cell activation and autoimmunity in mice lacking interleukin-2 receptor beta. Science (Wash DC) 1995;268:1472–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.7770771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peschon JJ, Morrissey PJ, Grabstein KH, Ramsdell FJ, Maraskovsky E, Gliniak BC, Park LS, Ziegler SF, Williams DE, Ware CB, Meyer JD, Davison BL. Early lymphocyte expansion is severely impaired in interleukin 7 receptor–deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1955–1960. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arase H, Ono S, Arase N, Park SY, Wakizaka K, Watanabe H, Ohno H, Saito T. Developmental arrest of NK1.1+ T cell antigen receptor (TCR)-α/β+ T cells and expansion of NK1.1+ TCR-γ/δ+T cell development in CD3-ζ-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1995;182:891–895. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]