Abstract

In Leishmaniasis, as in many infectious diseases, clinical manifestations are determined by the interaction between the genetics of the host and of the parasite. Here we describe studies mapping two loci controlling resistance to murine cutaneous leishmaniasis. Mice infected with L. major show marked genetic differences in disease manifestations: BALB/c mice are susceptible, exhibiting enlarging lesions that progress to systemic disease and death, whereas C57BL/6 are resistant, developing small, self-healing lesions. F2 animals from a C57BL/6 × BALB/c cross showed a continuous distribution of lesion score. Quantitative trait loci (QTL) have been mapped after a non-parametric QTL analysis on a genome-wide scan on 199 animals. QTLs identified were confirmed in a second cross of 271 animals. Linkage was confirmed to a chromosome 9 locus (D9Mit67–D9Mit71) and to a region including the H2 locus on chromosome 17. These have been named lmr2 and lmr1, respectively.

Successful resolution of an infectious disease requires precise control of the delicate immunologic balance between eradication of the invading organism and self harm. The genetic interplay between microorganism and host determines the disease outcome, notably the elimination of microbes and associated immunopathologies. Leishmaniasis is an excellent example of a complex parasite–host interaction. Different Leishmania species cause clinically distinct diseases and the severity of disease caused by any given parasite can vary markedly between individual hosts (1, 2). This observation extends to the murine L. major model where the strain of inbred mouse determines the outcome of infection, C57BL/6 mice being uniformly resistant and BALB/c consistently susceptible (3).

While the genetic basis for resistance to parasitic infections is largely unknown, indirect evidence suggests that the induction of distinct CD4+ T cell responses modulates outcome and pathology (4). In leishmaniasis, resistant C57BL/6 mice infected with L. major produce an early CD4+ Th1 response (5). This results in IFN-γ production, macrophage activation, parasite killing and resolution of the lesion (reviewed in reference 6). In contrast, susceptible BALB/c mice mount an early Th2 response and progressive disseminating disease ensues (5, 7). As the CD4+ T cell responses in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice mirror their clinical course, it is tempting to speculate that genes regulating disease outcome may be involved in the early control of T helper response selection. Alternatively, it is possible that this response is merely reflective of some more fundamental phenomenon and that the genetic events underlying resistance to disease control some other process. By studying disease outcome in terms of clinical phenotype, assumptions of underlying mechanisms are avoided. These are more easily addressed once the genetics of resistance are understood. With this in mind, we have undertaken to map loci involved in resistance to L. major infection using large F2 intercrosses between C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice.

Genetic approaches to mapping murine responses to L. major, although previously reported, have been inconclusive. Recombinant inbred (RI) lines have been used to map a trait which, despite claims to the contrary (8), is obviously complex. These RI lines do not represent sufficient meioses for accurate or reliable mapping of a multigenic trait. Nevertheless, a disease response locus has been mapped to chromosome 11 (Scl1) (9). In a separate experiment, not involving L. major infection but rather in vitro responsiveness of CD4+ cells to IL-12, linkage was found to the same chromosome (10). While linking this locus to resistance to L. major is seductive, because it contains a host of conceivably relevant cytokines and their receptors, no definitive genetic study has been published (11). We present phenotype and genotype data from 470 F2 animals that demonstrate the complex genetic and environmental nature of resistance to L. major, and describe linkage to two chromosomal regions: one on chromosome 9 and the other at the H2 locus on chromosome 17.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

All mice were bred and maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment at The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research. The BALB/cAnBradleyWEHI and C57BL/6J strains were tested for genetic authenticity in July 1996. Two separate crosses were bred and independently challenged with L. major parasites at 5 wk of age. Experiment A consisted of 12 parental mice of each inbred strain (C57BL/6 and BALB/c), 24 F1 (parental cross), and 199 F2 (F1 intercross) mice. Experiment B comprised six C57BL/6, 16 BALB/c, 12 F1, and 271 F2 mice. Equal numbers of male and female F1 and F2 mice were used. F1 animals were generated from both BALB/c × C57BL/6 and C57BL/6 × BALB/c crosses and the F2 generation produced by intercrossing within each of these F1 groups.

Infection.

In Experiment A, each mouse was infected intradermally with 105 viable L. major V121 promastigotes at the base of the tail (12). The course of the infection was monitored weekly for 5 1/2 mo using the scoring system described previously (13). Individual scores describe the size of the lesion, 0 representing no lesion and 4 representing a lesion greater than 10 mm in diameter. A resistance score was assigned to individual mice by taking the average of its lesion scores between weeks 3 and 14. Animals with large progressive lesions and incipient systemic involvement were killed to minimize suffering. Weeks 1 and 2 were excluded because of the difficulty discriminating between a developing lesion and a healing injection site. For Experiment B, the parasites used were less virulent than for Experiment A. Therefore, 2 × 105 promastigotes were inoculated. Lesions were scored weekly for 14 wk.

The Parasite.

The L. major cloned line V121 was originally obtained from a patient with cutaneous leishmaniasis in Israel, and stabilates have been maintained in liquid nitrogen with periodic passage through nude mice. For infection of mice, the parasites were cultured in the biphasic blood agar medium NNN (14). A parasite clone of diminished virulence was used in these experiments and parasite inoculum was titrated against disease outcome. The parasite dose chosen ensures that resistance in the C57BL/6 mice is completely penetrant, however, a percentage of BALB/c mice were not totally susceptible. The use of a parasite of lower virulence allows more certainty when mapping loci in susceptible F2 animals.

Genotyping.

Genomic DNA was prepared from tail snips from each F2 mouse (15). DNA from all F2 animals from Experiment A were individually screened by PCR (16) against 126 simple sequence length polymorphic (SSLP) markers (17) chosen from the Whitehead Institute collection (18). This represents an average 12 cM density of markers across the genome. Genotyping was performed using an adaptation of the multiplex sequencing method of Church and Richterich (19, 20). Multiple PCR products were pooled, ethanol precipitated and loaded onto a 7% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. DNA was transferred onto nylon filters (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) fixed by UV light, and probed with biotinylated streptavidin alkaline–phosphatase conjugated oligonucleotides. The oligonucleotide probes were one of the pair used in the initial PCR assays. Bands were visualized by chemiluminescent autoradiography after washing and incubation in the alkaline phosphatase substrate CDP-Star (Boehringer Mannheim). Filters were probed multiple times and assays loaded so that several loci, differing in their allele size distribution could be seen simultaneously. Three regions identified as suggestive of linkage during the genome scan on the first 199 F2 animals in Experiment A were tested for linkage with 11 SSLP markers in the second 271 F2 animals (Experiment B).

Linkage Analysis.

Non-parametric quantitative trait locus (QTL) linkage analysis was performed using the MAPMAKER package: MAPMAKER/EXP 3.0B (21) and MAPMAKER/QTL 1.9 (obtained from M. Daly, mjdaly@genome.mit.edu) on all 199 F2 animals from Experiment A. Since the trait does not follow a normal distribution, the non-parametric statistic, Xw, was used. The ability of this test to account simultaneously for additive or dominance effects of the trait at a locus without significantly compromising its sensitivity to detect linkage makes it ideal for non-parametric genome scans (22). Xw values of 4.4 and above represent increasingly significant evidence for linkage and are equivalent to lod scores of 3.3 and above. Candidate regions identified from Experiment A were genotyped in the 271 F2 animals from Experiment B and linkage to candidate QTLs assessed using the non-parametric Xw statistic in MAPMAKER/QTL 1.9.

To address the issue of decreased penetrance for susceptibility (not all BALB/c mice were susceptible) a second linkage strategy was employed. The hypothesis that the most susceptible animals will be homozygous BALB/c at resistance loci was tested using a χ2 analysis. This was performed in all animals exhibiting a lesion score of 4 by week 14 (9% of F2s), and departure from the expected 25% of homozygous BALB/c genotypes and 75% of nonhomozygous BALB/c genotypes was calculated. Linkage to the candidate loci was then determined using a binomial model (23). A lod score of 3.3 or greater indicates strong support for linkage.

Results

Disease Phenotype.

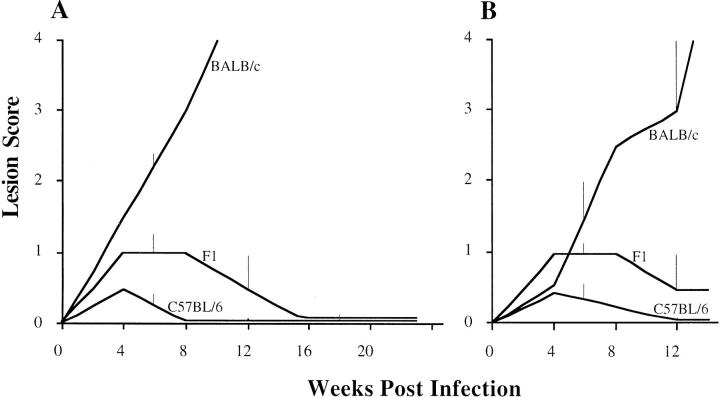

The pattern of disease after infection with L. major was similar in the two experiments (Figs. 1 and 2). The disease in the isogenic parental and F1 groups was as anticipated: BALB/c mice rapidly progressed to disseminated disease, F1 mice were intermediate in their resistance and C57BL/6 mice were uniformly resistant. All groups in the second experiment were slightly more resistant than the groups in the first experiment.

Figure 1.

The kinetics of lesion development after L. major infection in BALB/c, C57BL/6, and their F1 generation expressed as the median lesion score over time. A shows results from 12 BALB/c, 12 C57BL/6, and 24 F1 mice. B shows the second experiment with 16 BALB/c, 6 C57BL/6, and 12 F1 mice. The vertical bars represent the semi-interquartile ranges. As all C57BL/6 mice cure their lesions, resistance is fully penetrant.

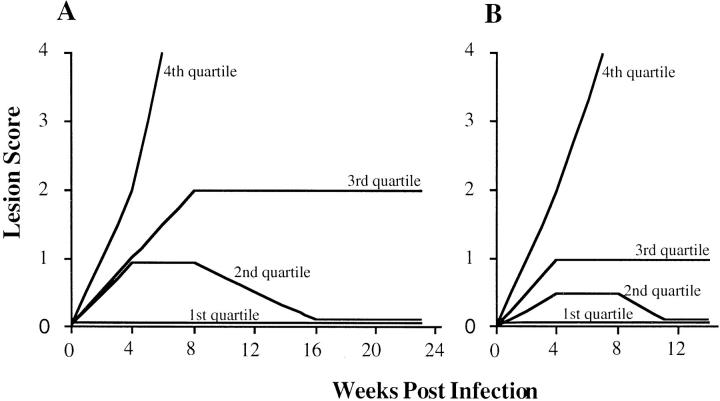

Figure 2.

The kinetics of lesion development after L. major infection in the F2 generation expressed as the lesion score over time. A and B represent two separate experiments with 199 and 271 F2 mice, respectively. The first quartile represents the lesion score of the animal at the 25th percentile, the second quartile represents the 50th percentile animal, etc. These data demonstrate a continuous distribution of this trait in the F2 generation. Animals were slightly more resistant in the second experiment compared to the first.

Resistance in the F2 generation was a continuum spread between the two parental extremes (Fig. 2). 25% of all F2 animals developed no lesion and only 9% of animals recapitulated the susceptible, BALB/c-like phenotype. The distribution was not normal, being skewed towards resistance. A novel intermediate phenotype was observed where lesions, which developed to a moderate size, persisted without progression or cure. After 23 wk, 12% of mice displayed this undifferentiated phenotype. The outcome at 23 wk was retrospectively predictable at 14 wk after inoculation.

Genetic Linkage.

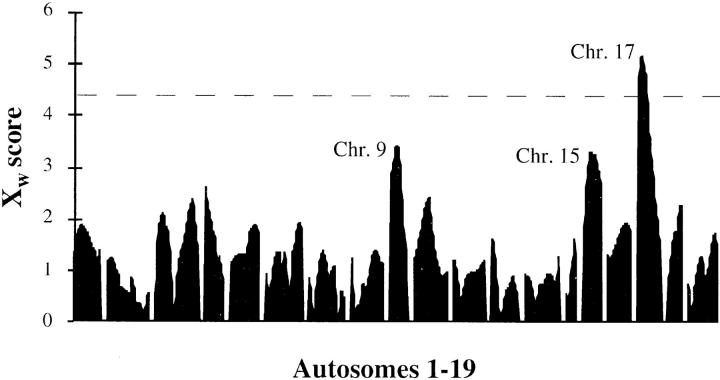

MAPMAKER/EXP 3.0B was used to build a genetic map from the genotypic data. This map order agreed with published marker order and distances (18). A QTL scan of the genome was performed using a nonparametric method as implemented in MAPMAKER/ QTL 1.9 (Fig. 3). A single region showing significant linkage was observed overlying the proximal end of chromosome 17 (Xw value = 5.3). Two further regions suggestive of linkage were detected on chromosomes 9 (Xw = 3.4) and 15 (Xw = 3.3). Markers from these regions were used to confirm linkage with the second set of 271 animals. The chromosome 9 and 17 results were sustained, whereas linkage was not confirmed for the chromosome 15 locus. The support for linkage from the two combined experiments was Xw = 4.4 for the chromosome 9 locus with the peak between D9Mit67 and D9Mit71, and Xw = 7.1 for the chromosome 17 locus, the peak being found between D17Mit11 and D17Mit115. The locus on chromosome 9 has been called lmr2, and the chromosome 17 locus, lmr1.

Figure 3.

A 12 cM density genome-wide non-parametric QTL scan for outcome of L. major infection in 199 F2 mice. The results are expressed as the non-parametric Xw score. Linkage is considered significant at the threshold of 4.4, which is equivalent to a lod score of 3.3. Chr. = Chromosome.

Susceptibility showed incomplete penetrance in the parental BALB/c animals whereas resistance was fully penetrant in the parental C57BL/6 mice, a situation likely to be reiterated in the F2 animals. Therefore, a χ2 analysis was performed on all susceptible animals (defined as those animals with a lesion score of 4 by week 14). A dominance model for resistance was assumed and loci implicated by the non-parametric scan were studied. The homozygous BALB/c genotype was significantly skewed toward susceptibility at the chromosome 9 and 17 locus (Tables 1 and 2). Lod scores were then calculated using a binomial model that revealed evidence for significant linkage for markers on chromosome 17 (lod = 7.2) and chromosome 9 (lod = 3.7). No segregation distortion is evident at these regions (Table 2). Given the previous literature linking resistance to chromosome 11, lod scores were calculated for all chromosome 11 markers for all of the 199 animals in Experiment A. The highest lod score obtained was 0.323 for D11Mit208 and lod scores for markers surrounding the putative gene encoding resistance were −0.01 (D11Mit212), 0.159 (D11Mit59), and 0.002 (D11Mit202).

Table 1.

Linkage of Susceptibility to Chromosomes 17 and 9

| Marker | Position | χ2 | p value | Lod score* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cM | ||||||||

| D17Mit11 | 11 | 36 | 1.8 × 10−9 | 6.6 | ||||

| D17Mit115 | 19 | 40 | 2.9 × 10−10 | 7.2 | ||||

| D17Mit66 | 25 | 30 | 2.1 × 10−8 | 5.8 | ||||

| D9Mit67 | 17 | 16 | 2.7 × 10−5 | 3.3 | ||||

| D9Mit71 | 29 | 19 | 5.4 × 10−6 | 3.7 | ||||

| D9Mit133 | 43 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 0.085 |

χ2 analysis and lod scores for linkage of susceptibility to markers surrounding the two QTLs in the most susceptible mice.

Lod scores were calculated using a binomial model. Scores of 3.3 and greater indicate significant linkage.

Table 2.

Relationship of Genotype to Susceptibility at Linked Markers

| Marker | Position | 4th quartile | 3rd quartile | 2nd quartile | 1st quartile | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c/c | b/b | b/c | c/c | b/b | b/c | c/c | b/b | b/c | c/c | b/b | b/c | |||||||||||||||

| cM | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| D17Mit11 | 11 | 54 | 13 | 37 | 18 | 29 | 58 | 15 | 27 | 50 | 17 | 37 | 50 | |||||||||||||

| D17Mit115 | 19 | 52 | 13 | 39 | 19 | 28 | 60 | 19 | 23 | 49 | 16 | 39 | 49 | |||||||||||||

| D17Mit66 | 25 | 55 | 17 | 39 | 25 | 29 | 59 | 25 | 28 | 55 | 18 | 40 | 53 | |||||||||||||

| D9Mit67 | 17 | 46 | 20 | 46 | 26 | 34 | 51 | 31 | 25 | 54 | 21 | 28 | 65 | |||||||||||||

| D9Mit71 | 29 | 44 | 22 | 44 | 26 | 31 | 54 | 29 | 19 | 66 | 21 | 27 | 61 | |||||||||||||

| D9Mit133 | 43 | 31 | 32 | 49 | 26 | 40 | 44 | 32 | 24 | 54 | 19 | 40 | 51 | |||||||||||||

Genotypes of F2 mice split into quartiles based on decreasing susceptibility score. Genotype b/b represents a mouse homozygous for C57BL/6 alleles, c/c homozygous for BALB/c, and b/c heterozygotes.

Discussion

Gene mapping of 470 F2 mice infected with L. major parasites led to the identification of two host loci controlling disease outcome. The phenotype was limited to the clinical outcome after promastigote infection at the base of the tail. No immunological or parasitological correlates of disease were studied. These would have interfered with the study of outcome and will be studied upon production of congenic mice. The strain of parasite and infection dose were chosen to optimize the measurement of susceptibility by ensuring that the major determinant of susceptibility was genetic. This resulted in a percentage of the BALB/c mice showing variable severity of disease indicating the action of either environmental or stochastic influences, an observation not unique to this study (24). Inter- and intraexperimental phenotypic variation was small, parental animals being either entirely resistant (C57BL/6) or largely susceptible (BALB/c), and the F2 progeny falling along a continuous distribution as expected of a quantitative trait. F1 animals were less resistant than the C57BL/6 mice. They do, however, cure their lesions indicating that susceptibility is a recessive trait.

Three loci were identified on an initial genome-wide scan performed on 199 F2 mice. Significant linkage was found for the peak on chromosome 17 (D17Mit11–D17Mit115), but the two other peaks on chromosomes 9 (D9Mit67– D9Mit71) and 15 (D15Mit58–D15Mit159) were only suggestive of linkage. Therefore, markers surrounding all three loci were tested on a second set of 271 animals. Linkage was confirmed for chromosomes 9 and 17 but not for the chromosome 15 locus. These findings were validated using a simple approach that linked susceptibility to markers surrounding the chromosomes 9 and 17 loci in only those most susceptible of animals. This test was possible due to the choice of a lower virulent parasite giving rise to a susceptibility phenotype in which virtually all phenotypic control is genetic.

At least two genes control the host response to L. major in a cross between BALB/c and C57BL/6. While linkage to chromosome 17 was significant in the initial 199 animals, the chromosome 9 locus required the full 940 meioses before the genome-wide significance threshold was reached. It is quite possible that other genes are involved in this cross and were not detected in the linkage analysis. This is in part inferred from the fact that not all the susceptible animals are homozygous for either the chromosome 9 or 17 loci (data not shown), indicating the activity of other genetic or environmental factors. Given that two genes have been identified in a cross representing the genetic diversity of only one outbred individual, it is likely that other naturally occurring polymorphisms will also influence outcome of L. major infection. These may be identified in other crosses and may explain the discordancies with previous mapping efforts (9, 24).

Although it is still early to speculate about candidate genes, it has not escaped our notice that the H2 locus lies directly beneath the peak of the QTL scan on chromosome 17. The role of H2 in resistance to L. major is far from clear. Studies using mice congenic for the H2 locus have shown no effect or little effect (8, 3). The small effect demonstrated by Howard et al. was a slowing of the rate of lesion expansion in BALB/K animals. A similar, but more pronounced effect was seen in BALB/c.H-2k animals where lesions healed (25). However, these were different congenic animals from those of Howard et al. Explanations for the discordant results may lie in the different mouse strains used for the experiments, the different origins of the H2 regions in the congenic mice, the number of generations of backcrossing, or the different size of the remaining donor region flanking H2 in the congenic mice. These issues may be resolved once fine mapping of the chromosome 17 region is completed and the precise location of lmr1 is determined. For completeness, the chromosome 9 locus overlies the IL-10 receptor, which makes it an attractive candidate considering the role of IL-10 in L. major infection (26).

Although no immunological measurements were made in these animals, there is abundant evidence that the CD4+ lymphocyte response is crucial in controlling the outcome of L. major infection. Therefore, it is possible that one or both loci described in this work contribute to the early establishment of this response. This matter will be more easily investigated in animals made congenic at these loci.

Mouse strain differences in terms of in vitro T helper cell responses have been mapped in the mouse to chromosome 11 (10), a chromosome to which L. major resistance has also been mapped (9, 24). Mock et al. used animals from seven RI lines generated from a C57BL/6 × BALB/c cross to map resistance to this region. Although they used too few animals to generate statistically significant linkage, their data are, in fact, also consistent with mapping to the H2 region. We find no linkage to any region of chromosome 11, implying that the locus mediating CD4+ lymphocyte response in the in vitro model reported by Gorham et al. (10) has no measurable effect on the progression of L. major–induced disease in our C57BL/6 × BALB/c cross. This may reflect the different phenotypes used and if so, it follows that the phenotype measured by Gorham et al. acts independently to outcome in L. major infection (10).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Jim Kazura for the critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions. The expert advice and technical assistance of Vikki Marshall and the technical assistance of Yvette Looby is appreciated. We thank Mark Daly for pre-release of MAPMAKER/QTL 1.9.

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Wellcome Trust (S.J. Foote).

References

- 1.Convit J, Pinardi ME, Rondon AJ. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis: a disease due to an immunological defect of the host. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1972;66:603–610. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(72)90306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley DJ. Genetic control of natural resistance to Leishmania donovani. . Nature (Lond) 1974;250:353. doi: 10.1038/250353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard JG, Hale C, Chan-Liew WL. Immunological regulation of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. I. Immunogenetic aspects of susceptibility to Leishmania tropicain mice. Parasite Immunol. 1980;2:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1980.tb00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLeod R, Buschman E, Arbuckle LD, Skamene E. Immunogenetics in the analysis of resistance to intracellular pathogens. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:539–552. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Locksley RM, Heinzel FP, Sadick MD, Holaday BJ, Gardner KD., Jr Murine cutaneous leishmaniasis: susceptibility correlates with differential expansion of helper T-cell subsets. Ann Inst Pasteur Immunol. 1987;138:744–749. doi: 10.1016/s0769-2625(87)80030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiner SL, Locksley RM. The regulation of immunity to Leishmania major. . Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:151–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris L, Troutt AB, McLeod KS, Kelso A, Handman E, Aebischer T. Interleukin-4 but not interferon-γ production correlates with the severity of disease in murine cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3459–3465. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3459-3465.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeTolla LJ, Scott PA, Farrell JP. Single gene control of resistance to cutaneous leishmaniasis in mice. Immunogenetics. 1981;14:29–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00344297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mock B, Blackwell J, Hilgers J, Potter M, Nacy C. Genetic control of Leishmania majorinfection in congenic, recombinant inbred and F2 populations of mice. Eur J Immunogen. 1993;20:335–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313x.1993.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorham JD, Guler ML, Steen RG, Mackey AJ, Daly MJ, Frederick K, Dietrich WF, Murphy KM. Genetic mapping of a murine locus controlling development of T helper 1/T helper 2 type responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12467–12472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demant P, Lipoldova M, Svobodova M. Resistance to Leishmania majorin mice. Science (Wash DC) 1996;274:1392–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell GF, Curtis JM, Handman E, McKenzie IFC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in mice: disease patterns in reconstituted nude mice of several genotypes infected with Leishmania tropica. . Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1980;58:521–532. doi: 10.1038/icb.1980.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell GF. Murine cutaneous leishmaniasis: resistance in reconstituted nude mice and several F1 hybrids infected with Leishmania tropica major. . J Immunogenetics. 1983;10:395–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313x.1983.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handman E, Hocking RE, Mitchell GF, Spithill TW. Isolation and characterization of infective and noninfective clones of Leishmania tropica. . Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1983;7:111–126. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(83)90039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laird PW, Zijderveld A, Linders K, Rudnicki MA, Jaenisch R, Berns A. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullis K, Faloona F, Scharf S, Saiki R, Horn G, Erlich H. Specific enzymatic amplification of DNA in vitro: the polymerase chain reaction. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1986;1:263–273. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1986.051.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber JL. Human DNA polymorphisms and methods of analysis. Curr Opin Biotech. 1990;1:166–171. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(90)90026-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietrich WF, Miller J, Steen R, Merchant MA, Damron-Boles D, Husain Z, Dredge R, Daly MJ, Ingalls KA, O'Connor TJ, et al. A comprehensive genetic map of the mouse genome. Nature (Lond) 1996;380:149–152. doi: 10.1038/380149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Church GM, Kieffer-Higgins S. Multiplex DNA sequencing. Science (Wash DC) 1988;240:185–188. doi: 10.1126/science.3353714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richterich P, Church GM. DNA sequencing with direct transfer electrophoresis and nonradioactive detection. Methods Enzymol. 1993;218:187–222. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)18016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lander ES, Green P, Abrahamson J, Barlow A, Daly MJ, Lincoln SE, Newburg L. MAPMAKER: an interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics. 1987;1:174–181. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(87)90010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruglyak L, Lander ES. A nonparametric approach for mapping quantitative trait loci. Genetics. 1995;139:1421–1428. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.3.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eicher EM, Washburn NJ, Schork NJ, Lee BK, Shown EP, Xu X, Dredge RD, Pringle MJ, Page DC. Sex-determining genes on mouse autosomes identified by linkage analysis of C57BL/6J-YPOSsex reversal. Nature Genet. 1996;14:206–209. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts M, Mock BA, Blackwell JM. Mapping of genes controlling Leishmania majorinfection in CXS recombinant inbred mice. Eur J Immunogen. 1993;20:349–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313x.1993.tb00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell GF, Curtis JM, Handman E. Resistance to cutaneous leishmaniasis in genetically-susceptible BALB/c mice. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1981;59:555–566. doi: 10.1038/icb.1981.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vieth M, Will A, Schroppel K, Rollinghoff M, Gessner A. Interleukin-10 inhibits antimicrobial activity against Leishmania majorin murine macrophages. Scand J Immunol. 1994;40:403–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1994.tb03481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]