Abstract

The α/β T cell receptor (TCR) recognizes peptide fragments bound in the groove of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. We modified the TCR α chain from a mouse T cell hybridoma and tested its ability to reconstitute TCR expression and function in an α chain–deficient variant of the hybridoma. The modified α chain differed from wild type only in its leader peptide and mature NH2-terminal amino acid. Reconstituted cell surface TCR complexes reacted normally with anti-TCR and anti-CD3 antibodies. Although cross-linking of this TCR with an antibody to the TCR idiotype elicited vigorous T cell hybridoma activation, stimulation with its natural MHC + peptide ligand did not. We demonstrated that this phenotype could be reproduced simply by substituting the glutamic acid (E) at the mature NH2 terminus of the wild type TCR α chain with aspartic acid (D). The substitution also dramatically reduced the affinity of soluble α/β-TCR heterodimers for soluble MHC + peptide molecules in a cell-free system, suggesting that it did not exert its effect simply by disrupting TCR interactions with accessory molecules on the hybridoma. These results demonstrate for the first time that amino acids which are not in the canonical TCR complementarity determining regions can be critical in determining how the TCR engages MHC + peptide.

The structural basis of antigen recognition by antibody molecules has been intensely studied using x-ray crystallography. Crystal structures of a large array of antibodies and antibody–antigen complexes have demonstrated that the hypervariable regions of Ig genes encode solvent-exposed loops that cluster to form the antigen-binding site of the Ig V domains. These loops are known as CDRs. Analysis of Ig crystal structures and CDR sequences has shown that the spatial orientation and conformation of the loops is influenced by two factors.

The first concerns the CDR itself. Each of the CDR loops appears to adopt a limited range of main chain conformations despite their diverse amino acid sequences (1). These conformations are shaped by a small number of relatively well-conserved amino acid residues within the loops. The second factor is the V domain scaffolding upon which the CDRs rest. It consists of two β sheets packed face to face and anchored by a structurally conserved core of “framework” residues. The conformations of CDR loops are partially determined by the manner in which they pack with the side chains of certain framework residues (1, 2). An understanding of these factors has resulted in a limited ability to predict CDR loop conformations of Igs of unknown crystal structure from the sequences of their heavy and light chain genes (1). This is a first step towards the engineering of antibodies specific for antigens of interest.

The α/β-TCR recognizes peptide fragments bound in the groove of MHC molecules. The structural basis of this recognition is understood in far less detail than that for Igs, largely because soluble versions of these naturally membrane-bound structures have only recently been developed. Crystal structures of MHC class I (3–7) and class II (8–10) molecules with single peptides bound in their grooves have provided a detailed picture of the ligand with which TCRs interact. Crystal structures of one mouse TCR β chain (11), one mouse TCR Vα domain (12), and two α/β-TCRs bound to their class I MHC + peptide ligands (13, 14), verified predictions (15–17) that the ligand binding site of the TCR consists of Ig-like CDR loops supported by a dual β sheet framework, but has not yet provided enough information to allow the construction of detailed models of the CDR loop architecture or the examination of the role of TCR framework residues in shaping it.

In this paper, we describe a mutation in the NH2-terminal Vα amino acid of a mouse α/β-TCR that alters its ability to bind to its MHC + peptide ligand. We discuss how this non-CDR residue may play an important role in TCR specificity.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines.

The mouse T cell hybridoma used in these studies was 2B10.D2O-22.3 (22.3) specific for chicken OVA peptides 323–339 or 327–339 presented by IAd (IAd/OVA). It was generated by fusing the AKR thymoma fusion partner BW-1100. 129.237 (BWα−/β−; 18) to lymph node cells from a B10.D2 mouse immunized with OVA 327–339 (Kushnir, E., unpublished data). The TCR α and β chains of 22.3 are identical in amino acid sequence to those of DO-11.10, a previously described T cell hybridoma with the same specificity (19, 20). Therefore, these chains are designated DOα and DOβ in this paper. Unlike DO-11.10, however, 22.3 did not express any other functional TCR-α or -β genes. 22.3 was recloned to isolate two subclones, 22.3.111 and 22.3.145, which bear lower levels of surface TCR. In addition, a spontaneous TCR α chain loss variant of 22.3 was isolated, 22.3α−. This variant expresses DOβ mRNA, but does not contain DNA encoding DOα and therefore was useful as a recipient for ( chain transfection studies.

Two-color Flow Cytometry.

T cell hybridomas were stained for cell surface molecules and analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described (21) using the following mAbs: KJ1-26 (22) is specific for the idiotype of the TCR on DO-11.10 and 22.3, and H57-597 (23), 145-2C11 (24), and GK1.5 (25) are specific for mouse TCR Cβ, CD3ε, and CD4, respectively. In brief, 2–5 × 105 hybridoma cells were incubated with biotinylated KJ1-26 or H57-597 at 4°C for 20 min. Cells were washed three times and incubated at 4°C for 20 min with FITC-conjugated 145-2C11 or GK1.5 and streptavidin R–conjugated phycoerythrin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Finally, cells were washed three times and two-color fluorescence data was acquired on either an EPICS C or a Profile flow cytometer (Coulter Corp., Hialeah, FL).

T Cell Hybridoma Stimulation Assays.

T cell hybridoma activation in response to TCR ligation was assayed by measuring IL-2 secretion, as described previously (26). Stimulation assays were performed in 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plates. In peptide stimulations 105 IAd-expressing A20-1.11/B5 B cell lymphoma cells (27) were added per well with different concentrations of OVA 327–339. For anti-TCR mAb stimulation, Immulon-3 (Dynatech Labs. Inc., Chantilly, VA) microtiter plates were coated overnight at 4°C with serial dilutions of protein A–purified KJ126 in PBS. Peptide and antibody stimulations both used 105 hybridoma T cells/well and were incubated for 16–30 h at 37°C. IL-2 production was quantitated using the IL-2–dependent cell line HT-2 (28) and measurement of HT-2 survival by the oxidation of (dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (29).

Characterization of the Vα13.1 leader from 22.3.

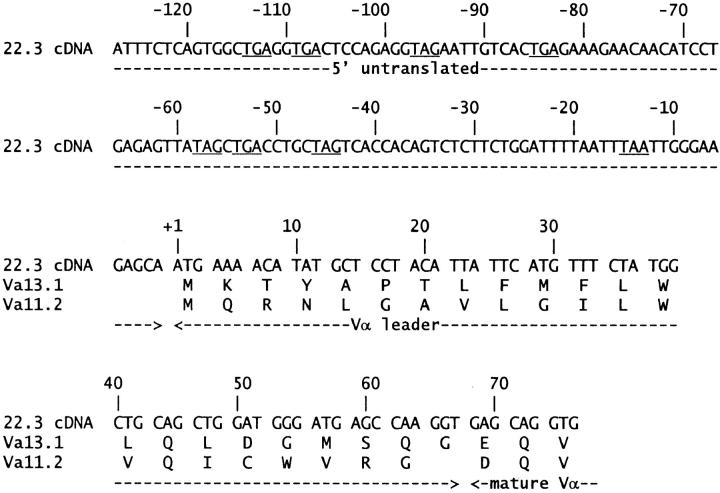

Using an anchored PCR strategy modified from Loh et al. (30), DNA encoding the Vα13.1 (AV13S1) leader was cloned to determine the unknown sequence of its 5′ end. Total RNA was prepared from the 22.3 hybridoma using the Ultraspec reagent (Biotecx Labs., Houston, TX). Oligo-dT-primed first strand cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript reverse transcriptase cDNA synthesis kit (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and was tailed at the 5′ end with dG residues using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (International Biotechnologies Inc., New Haven, CT). TCR α chain gene sequences were PCR amplified from tailed cDNA using the anchored sense primer 5′-ATCGAGTCGACGCCCCCCCC-3′ and the antisense primer 5′-CCCCAGACAGCCGTCTTGACG-3′, synthesized at the National Jewish Molecular Resource Center (Denver, CO). The latter primer anneals to an insertion in the 3′ untranslated region of TCR α chain transcripts that is present in C57 mouse strains, but not AKR or BALB/c strains (31, 32, and Seibel, J., unpublished data). This avoided amplification of the nonfunctional TCR α chain transcripts contributed to the 22.3 hybridoma by the AKR thymoma fusion partner BWα−/β− (33, 34). This anchored PCR product was reamplified using the same anchored sense primer and the antisense primer 5′-TCTCGAATTCAGGCAGAGGGTGCTGTCC-3′ (35), yielding a product that was digested with SalI and EcoRI and cloned into the pTZ18R vector (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) for sequencing. The complete cDNA sequence of the Vα13.1 leader and its 5′ untranslated region are presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Complete nucleotide sequence of the Vα13.1 leader and its 5′ untranslated region. The sequence of the Vα13.1 leader was assembled from six independently cloned PCR products of different lengths, which were obtained by anchored reverse transcriptase PCR from the B10.D2derived T cell hybridoma, 22.3. Deduced amino acid residues are shown. Underlined triplets in the 5′ untranslated region indicate stop codons, which are found in all three reading frames. The Vα11.2 leader is shown for comparison. Assignment of the boundary between the leaders and the mature variable domains is based on standard mouse TCR α chain sequence alignments (54).

DOα Chain Gene Constructs and Expression Vectors.

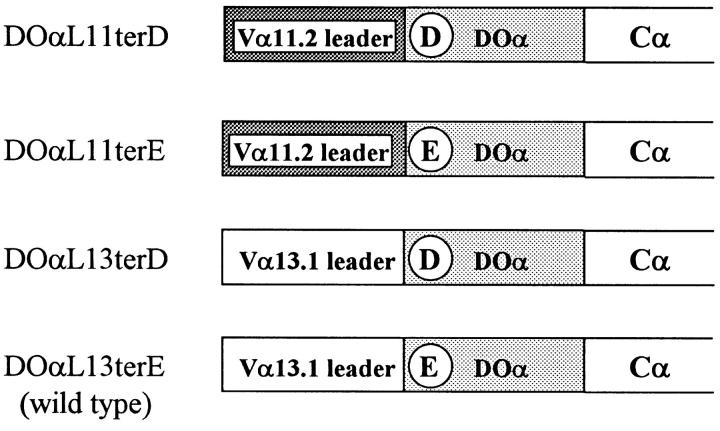

We used PCR techniques (36, 37) to construct four versions of the Vα portion of DOα chain gene using either the Vα11.2 (AV11S2) or Vα13.1 (AV13S1) leader peptide and having a predicted NH2terminal amino acid of either aspartic acid (D) or glutamic acid (E). These are designated DOαL11terD, DOαL11terE, DOαL13terD, and DO(L13terE (identical to wild-type DOα (Fig. 2). These were cloned in pTZ18R fused in frame to the mouse Cα gene using a XhoI site at the 5′-end of the Vα segment and an introduced AccIII site at the 5′-end of Cα (36), such that the final complete α chain was flanked by EcoRI sites. To express these variant DOα constructs in the 22.3α− hybridoma, the EcoRI fragments were isolated and cloned into the EcoRI site of the murine retrovirus–based vector, LXSN (38). Using methods modified from Miller et al. (38), DOα RNAs were packaged into retroviruses in the GP&env AM12 (39) and PA-317 (40) cell lines, and were introduced into the 22.3α− hybridoma by infection. Infectants with stably integrated DOα genes were selected and maintained with culture medium containing 1–1.2 mg/ml G418 (Geneticin; GIBCO BRL).

Figure 2.

DOα chain variant constructs. Circled letters indicate the predicted NH2-terminal amino acid of the mature α chain.

Production of Soluble TCRs and IAd Protein Covalently Bound to Chicken OVA 327–339.

XhoI/AccIII fragments of DOαL11terD and DOαL13terE were cloned in frame with a truncated gene for mouse Cα in a previously described baculovirus transfer vector that also encodes the soluble DO-11.10(Δ1,3) TCR β chain (36). Recombinant baculoviruses prepared from these vectors coexpressing the TCR-α and -β genes were used to infect Hi 5 insect cells (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). Soluble heterodimers were purified from cell supernatants by immunoaffinity chromatography on an antiidiotype column, followed by a HiLoad 26.60 Superdex200 size exclusion column (Pharmacia). The proteins were further purified to a single detectable species using Mono Q ion exchange chromatography (Pharmacia). IAd-OVA, a soluble ligand for the DOα/β-TCR that consists of a soluble IAd molecule genetically attached to the OVA peptide via a flexible peptide linker to the IAdβ chain NH2 terminus, was produced in baculovirus as previously described (41). It was purified by immunoaffinity chromatography on an anti-IAd mAb (M5/114, reference 42) column, and further purified on a HiLoad 26.60 Superdex 200 column. Gels revealed that these procedures yielded preparations of monomeric heterodimers of both the TCR and class II proteins with no detectable contamination of either protein with aggregates or homodimers.

BIAcore Measurements of TCR Binding to IAd-OVA.

The BIAcore system was used to assess soluble IAd-OVA binding to TCRs. The high affinity anti-Cβ mAb, H57-597, was immobilized in flow cells of a BIAcore biosensor CM-5 chip using standard amine coupling chemistry. Flow cells were injected with solutions of various soluble TCRs at 5 μg/ml until binding to the anti-Cβ antibody was saturated. This captured TCR increased surface plasmon resonance signals by ∼2,000 resonance units. Since the captured TCR dissociated very slowly, we could detect its binding to subsequently injected IAd-OVA. Solutions of IAdOVA (2.5, 5, or 10 μM in phosphate-buffered saline containing 5 mM azide and 0.005% P20 surfactant) were injected for 1 min at a flow rate of 20 μl/min. The TCR-bound IAd-OVA was then allowed to dissociate for several minutes. Between injections, the anti-Cβ mAb was resaturated with TCR. To control for signal due to the bulk refractive index of the IAd-OVA in solution, or for any differences in the refractive index of the buffers used, an identical set of injections were performed in a flow cell containing captured free DOβ chain, rather than α/β-TCR. On and off rates for binding of IAd-OVA were calculated using the BIAcore software.

Results

Expression of a TCR α Chain in an α Chain–deficient Mouse T Cell Hybridoma.

To study the effects of mutations in the TCR α chain on MHC + peptide recognition by T cells, we used a mouse T cell hybridoma, 22.3, which could be stimulated by either IAd class II MHC molecules bound to chicken OVA 327-339 (IAd/OVA) or by the anti-TCR idiotype mAb, KJ1-26 (22). In an initial experiment, receptor expression in an α loss variant of this hybridoma, 22.3α−, was restored by infection with a retrovirus carrying a version of the full-length Vα13.1 bearing DOα chain gene. This construction, DOαL11terD, differed from the natural DOα chain in two respects. First, it contained a Vα11.2 leader (L11) in lieu of the then unknown native Vα13.1 leader (L13). Second, after cleavage of its leader peptide, the mature NH2 terminus of the DOαL11terD chain was aspartic acid (terD), instead of the glutamic acid (terE) of wild-type DOα. This conservative substitution was introduced to maintain a convenient cloning site. It was not expected to affect TCR specificity, since we had previously shown that it had no detectable effect on the binding of a number of anti-TCR mAbs, including KJ1-26, an mAb specific for the receptor idiotype (Kappler, J., unpublished data).

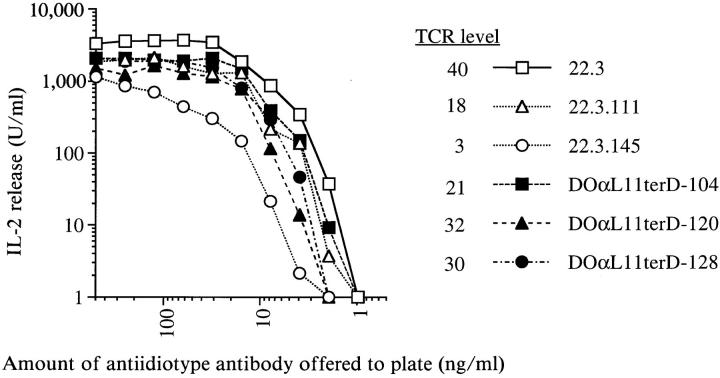

The infectants were screened for cell surface TCR expression by staining with mAbs to the DO TCR idiotype and CD3ε chain. Their levels of idiotype-reactive TCR were slightly lower than that of the parental hybridoma, 22.3, but were equal to or greater than those on two low TCR-expressing subclones of 22.3, 22.3.111, and 22.3.145 (Fig. 3). Cell surface levels of CD3ε suggested proper TCR association with CD3 components (data not shown). These staining results suggested that the DOαL11terD protein folded properly, associated normally with the TCR β chain and CD3 components, and reconstituted cell surface TCR complexes of normal structure.

Figure 3.

Infectants bearing the variant TCR α chain DOαL11terD respond to immobilized antiidiotype mAb as well as the parental hybridoma, 22.3, does. 22.3.111 and 22.3.145 are low TCR expressing subclones of 22.3. Data are representative of multiple experiments. TCR level indicates the mean linear fluorescence of antiidiotype mAb staining of the hybridomas.

To determine whether the structural integrity of the TCR complexes on the infectants was also reflected in functional competence, the infectants were cultured in plastic wells coated with antiidiotype mAb. In response to this TCR ligation and cross-linking stimulus, the infectants secreted IL-2 in a manner similar to that of the wild-type hybridoma, 22.3 (Fig. 3). This suggested that the TCR complexes containing the DOαL11terD chain were sufficient for normal ligation-induced signaling within the T cell hybridoma.

Replacement of the 22.3 α Chain with the DOαL11TerD Chain Resulted in a Hybridoma with Dramatically Reduced Ability to Respond to IAd/OVA.

Since DOαL11terD-containing TCR heterodimers mediated a vigorous IL-2 response to anti-TCR antibody stimulation, it was surprising that they did not reconstitute good IAd/OVA reactivity. As shown in Fig. 4, DOαL11terD infectants responded much more poorly to IAd/OVA than did the parental hybridoma, 22.3. Since the TCR α chain in these infectants differed from that of 22.3 only in its leader peptide and the substitution of D for E at the mature NH2 terminus, one or both of these changes must have caused the impaired responsiveness. The amino acid sequence of the leader might, for example, have altered the site at which the leader is trimmed from the mature protein. Such an effect has been described in several proteins (43–47), including an antidigoxin antibody in which single substitutions in the heavy chain leader peptide changed the length of the mature chain by up to 10 residues (48). Some of these length changes were sufficient to change the affinity of the antibody. An alternative hypothesis was that the NH2 terminus of the TCR chain influenced directly or indirectly TCR interaction with MHC + peptide.

Figure 4.

Infectants bearing the variant TCR α chain DOαL11terD respond poorly to IAd/OVA stimulation. cOVA 327–339 peptide was presented to the hybridomas by the IAd-expressing B cell lymphoma, A20. Data points indicate the means of duplicate wells in one representative experiment.

Responsiveness to IAd/OVA Was Restored in Infectants Expressing TCR α Chains with E at the Predicted NH2 Terminus, Regardless of Vα11.2 or Vα13.1 Leader Peptide Usage.

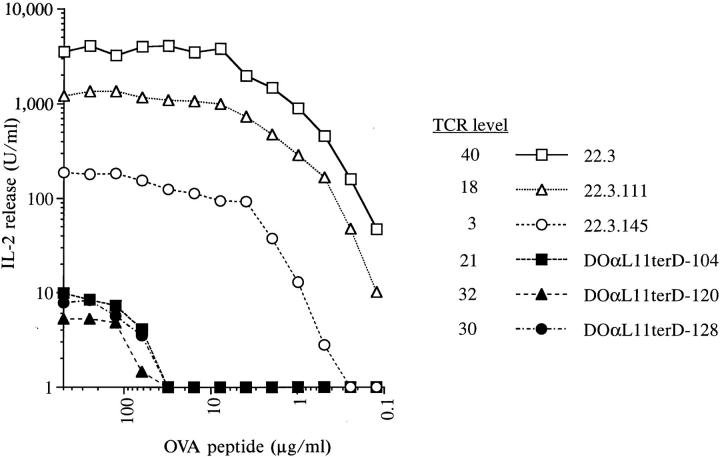

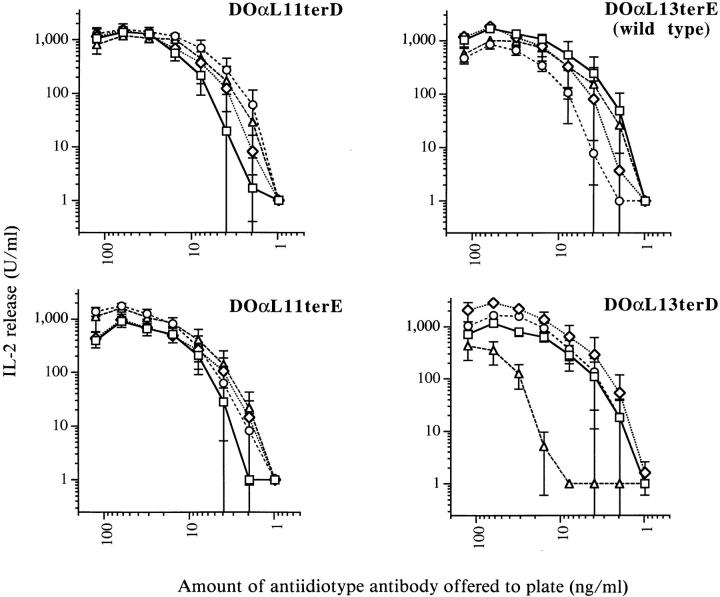

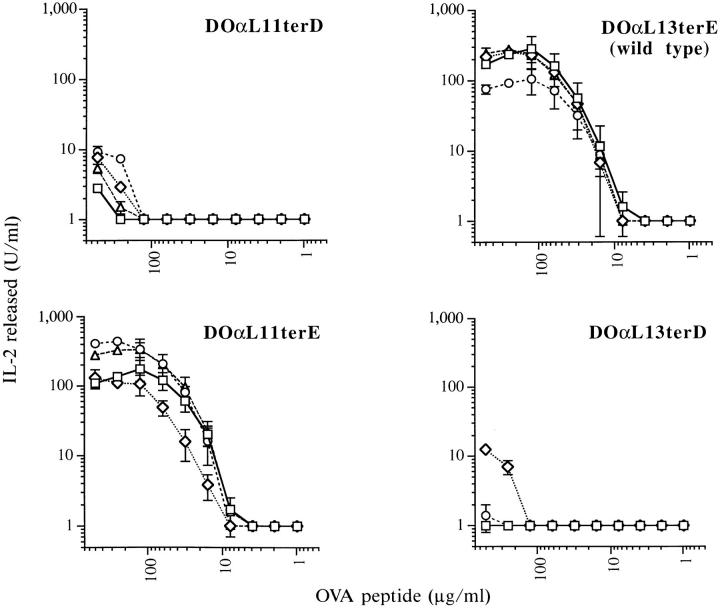

To identify individually the contributions of leader peptide and NH2 terminus to DOα chain function, we generated four types of 22.3α− infectants with each possible combination of L11, L13, terD, and terE (Fig. 2). The previously uncharacterized L13 leader was cloned from 22.3 (Fig. 1, Materials and Methods). Infectant clones that expressed comparable levels of cell surface TCR were selected by staining with antiidiotype mAb. Four clones of each type were tested for their ability to respond to antiidiotype antibody and to IAd/OVA. All four types of infectants possessed comparable signal transduction capacity, since they produced similar levels of IL-2 when stimulated with immobilized antiidiotype antibody (Fig. 5). We do not know why one DO(L13terD infectant responded more poorly than the other three.

Figure 5.

Infectants bearing any one of four DO TCR α chain variants respond equally well to immobilized antiidiotype mAb. Data points represent the means of two independent experiments with duplicate wells. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean. Four infectants of each variant type were tested. TCR levels of all infectants varied by less than twofold.

In contrast, the infectants were readily divided into two groups based on their ability to respond to IAd/OVA (Fig. 6). Regardless of the leader peptide they used, infectants expressing D at the NH2 terminus of their TCR α chains (DOαL11terD and DOαL13terD) responded very poorly. By contrast, infectants expressing NH2-terminal E (DOα L11terE and DOαL13terE) responded strongly.

Figure 6.

Infectants bearing variant DOα chains with D, but not E, at their predicted NH2 termini respond poorly to IAd/ OVA. Data points represent the means of three independent experiments with duplicate wells, except for those at 250 and 500 μg/ml OVA which represent only two such experiments. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean. Four infectants of each type were tested. TCR levels of all infectants varied by less than twofold.

The Mature NH2 Termini of Variant DOα Chains Produced as Soluble Proteins in Baculovirus Were as Predicted.

These experiments demonstrated that the leader peptide sequence did not affect the function of the DOα chain variants, and highlighted the importance of the predicted NH2 terminus of the mature protein for IAd/OVA responses. However, it was still formally possible that the E and D containing α chains might have had their signal peptides cleaved at different sites. This would have made the two types of chains different in length. Some structural aspect of the length disparity could have directly affected the interaction of the TCR with MHC + peptide, but not with anti-TCR antibodies.

To test this hypothesis, genes encoding soluble DOα chains with predicted NH2 termini of either E or D were coexpressed in insect cells with a gene encoding a soluble DOβ chain. Purified DOα/β heterodimers were sequenced by Edman degradation. Both DOα variants were found to bear the predicted NH2-terminal amino acid, E for DOαterE and D for DOαterD. Since insect signal peptidases typically cleave at the same site as their mammalian counterparts (49), we concluded that TCR α chains in our DOαterE and DOαterD infectant hybridomas were identical in length, differing only in the identity of the amino acid at their NH2 termini. This difference alone must have been responsible for their contrasting responses to IAd/OVA.

Substitution of the NH2-terminal Amino Acid of the DOα Chain Affects the Affinity of the DO TCR for MHC + peptide.

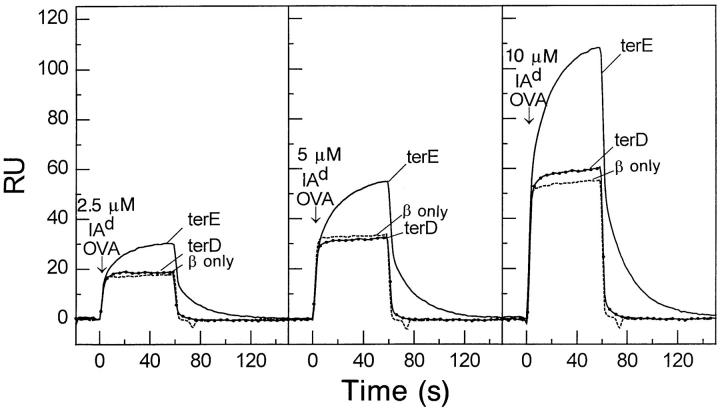

The simplest explanation for our results was that the substitution of D for E at the NH2 terminus of DOα directly altered the ability of the TCR to bind to IAd/OVA. However, it was also possible that the substitution acted indirectly. For example, it could have disrupted TCR interactions with a T cell accessory molecule such as CD4. Such an interaction may not have been required for activation of the hybridoma during stimulation with antiidiotype antibody, where large numbers of TCRs were ligated. However, it may have been critical for responses to IAd/OVA stimulation, where only a few TCRs on each hybridoma were engaged. To distinguish between these mechanisms, we used surface plasmon resonance to measure directly the binding of soluble IAd-OVA (40) to DOα/β heterodimers.

Anti-Cβ mAb was used to immobilize DOα/β heterodimers containing either DOαterE or DOαterD chains in separate flow cells of a biosensor chip. A flow cell in which the free DOβ chain was immobilized was used as a negative control. Various concentrations of IAd-OVA were passed through the flow cells and the binding kinetics followed (Fig. 7). Obvious binding of IAd-OVA to a TCR containing DOαterE was seen at all class II concentrations. The interaction had a relatively slow on rate, k a = 1.60 × 103 M−1s−1, and a fast off rate, k d = 0.05s−1, resulting in a dissociation constant (K D) of 31 μM. These kinetic and thermodynamic constants are similar to those observed for other TCRs binding to MHC class II + antigen complexes (50). In contrast, IAd-OVA bound very poorly to a TCR containing DOαterD. Very weak specific binding detected only at the highest concentration of IAd-OVA. This suggested a dissociation constant >300 μM. The results showed that the NH2 terminal E to D substitution in DOα disrupted TCR binding to class II + peptide in the absence of accessory molecules. We concluded that N terminal E must play a direct role in the interaction of this TCR with IAd/OVA.

Figure 7.

Substitution of D for E at the DOα chain NH2 terminus lowers the affinity of cell-free α/β-TCR for IAd-OVA. Various concentrations of IAd-OVA were injected in flow cells with immobilized DOα/β TCRs bearing DOα chains with either D or E at the NH2 terminus as described in the Materials and Methods. A flow cell with immobilized free β chain from this receptor was used as a control for signal from protein in solution and buffer differences.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that an E to D change in the NH2-terminal amino acid of a mouse TCR α chain significantly altered the affinity of the α/β-TCR heterodimer for its MHC + peptide ligand. This conservative change simply shortened the amino acid side chain by a single methylene group without changing its negative charge. This effect did not result in a gross alteration in TCR structure, since detection of the TCR complexes by anti-TCR mAbs was unaffected by the substitution. Moreover, overall TCRmediated signal transduction was not impaired by the substitution, since hybridomas bearing it responded normally to TCR cross-linking by immobilized antiidiotypic mAb.

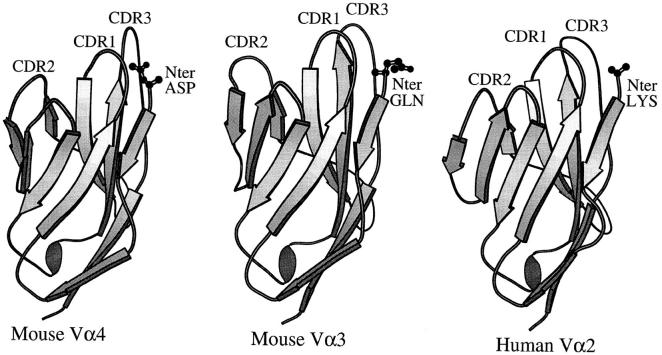

The E to D substitution could have affected MHC + peptide responsiveness either directly, by disrupting a contact between this amino acid and the ligand, or indirectly, by altering the shape or position of amino acids on one of the receptor CDR loops. The recent crystal structures of TCR Vαs both free and as part of TCR + MHC complexes suggest that either of these possibilities is feasible (Fig. 8, references 12–14). These structures include a free Vα domain, mouse Vα4(AV4S1), and two TCRs bound to their MHC class I/peptide ligands. These latter TCRs contained mouse Vα3 (AV3S1) and human Vα2(AV2S1).

Figure 8.

Position of the Vα NH2 terminus in three TCR crystal structures. The program Molscript was used to create a ribbon representation of three Vα elements based on their crystal structures. In each case, a wire frame representation of the NH2-terminal amino acid is shown. The mouse Vα4 structure (12) was of a Vα dimer in the absence of Vβ. The mouse Vα3 (13) and human Vα2 (14) structures were of complete α/βTCRs. The views are of the Vαs with their solvent exposed faces toward and their Vβ interaction surfaces facing away from the reader.

In all three structures, the Vα NH2-terminal amino acid is solvent exposed and in contact with the Vα β strands preceding Vα CDR1 and following Vα CDR3. It is easily conceivable that a mutation in this amino acid could alter CDR1 or CDR3 conformation. This is particularly evident in the mouse Vα4 structure (12), where the side chain carbonyl group of the NH2-terminal aspartic acid interacts intimately with both β strands.

Support for this notion comes from the study of Ig structures. One study comparing Ig crystal structures concluded that the conformation and position of CDR2 of the Ig heavy chain is largely shaped by the nature of the side chain on framework residue 71 (2). In another study, a spontaneous variant of an antidigoxin antibody with 580-fold less affinity for digoxin than wild type was found to have a substitution from S to R at position 94 in its heavy chain, a residue predicted to lie in the framework at the base of CDR3 (48, 51–53). Computer modeling suggested that the substitution increased hydrogen bonding between CDR3 of the heavy chain and CDR2 of the light chain so that the digoxin binding surface of the Ig was altered. Interestingly, most of the substitution's effect was reversed if two residues from the NH2 terminus of the heavy chain were removed. Modeling suggested that the deletion increased the solvent accessibility of R94, destabilizing the aberrant hydrogen bonding and returning the CDR loop structures to wild type.

In the two TCR + MHC class I crystal structures, the side chain of the Vα NH2-terminal amino acid does not appear to make direct contacts with the MHC ligand and, in fact, the side chain of the NH2-terminal lysine of human Vα2 appears disordered in the structure (14). However, the free NH2-terminal amino group of the Vα2 chain itself is connected by a salt bridge to a conserved glutamic acid in the α helical region of the MHC class I α1 domain (14). Such a salt bridge is not found in the TCR + MHC class I structure containing mouse Vα3 (13), and probably cannot be a general feature of TCR + MHC class II complexes since class II lacks the conserved glutamic acid residue in the α helix of its α1 domain. However, the overall positions of the Vα NH2-termini in the crystals suggest that depending on the exact orientation and pitch of the TCR on its MHC ligand, direct interaction between the Vα NH2terminal amino acid side chain and the MHC ligand may not be an infrequent feature of the complex.

Although further work will be necessary to confirm the generality of our results with this particular α/β-TCR, our findings suggest that gene constructs used to express soluble TCRs for use in binding assays and x-ray crystallography must be designed carefully. Substitutions at non-CDR residues must be introduced with the knowledge that they have the potential to disrupt MHC + peptide recognition. A detailed understanding of the role of TCR framework residues in MHC + peptide recognition will be difficult to attain until numerous TCR and TCR + MHC + peptide crystal structures have been solved.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Serge Candeias for assistance with the anchored PCR approach used to clone the Vα13.1 leader from 22.3. We thank Dr. Daved Fremont for helping us to interpret TCR crystal structures. We are grateful to Dr. Anthony Vella for advice and encouragement.

This work was supported by United States Public Service grants AI-17134, AI-18785, and AI-22295.

References

- 1.Chothia C, Lesk AM. Canonical structures for the hypervariable regions of immunoglobulins. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:901–910. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tramontano A, Chothia C, Lesk AM. Framework residue 71 is a major determinant of the position and conformation of the second hypervariable region in the VH domains of immunoglobulins. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:175–182. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fremont DH, Matsumura M, Stura EA, Peterson PA, Wilson IA. Crystal structures of two viral peptides in complex with murine MHC class I H-2Kb . Science (Wash DC) 1992;257:919–927. doi: 10.1126/science.1323877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W, Young AC, Imarai M, Nathenson SG, Sacchattini JC. Crystal structure of the major histocompatibility complex class I H-2Kbmolecule containing a single viral peptide: implications for peptide binding and T-cell receptor recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8403–8407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silver ML, Guo HC, Strominger JL, Wiley DC. Atomic structure of a human MHC molecule presenting an influenza virus peptide. Nature (Lond) 1992;360:367–369. doi: 10.1038/360367a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madden DR, Garboczi DN, Wiley DC. The antigenic identity of peptide–MHC complexes: a comparison of the conformations of five viral peptides presented by HLA-A2. Cell. 1993;75:693–708. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90490-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young AC, Zhang W, Sacchettini JC, Nathenson SG. The three-dimensional structure of H-2Db at 2.4 Å resolution: implications for antigen-determinant selection. Cell. 1994;76:39–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern L, Brown G, Jardetsky T, Gorga JM, Urban R, Strominger J, Wiley DC. Crystal structure of the human class II MHC protein HLA-DR1 complexed with an antigenic peptide from influenza virus. Nature (Lond) 1994;368:215–221. doi: 10.1038/368215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh P, Amaya M, Mellins E, Wiley DC. The structure of an intermediate in class II MHC maturation: CLIP bound to HLA-DR3. Nature (Lond) 1995;378:457–462. doi: 10.1038/378457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fremont DH, Hendrickson WA, Marrack P, Kappler JW. Structures of an MHC class II molecule with covalently bound single peptides. Science (Wash DC) 1996;272:1001–1004. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bentley GA, Boulot G, Karjalainen K, Mariuzza RA. Crystal structure of the β chain of a T cell antigen receptor. Science (Wash DC) 1995;267:1984–1987. doi: 10.1126/science.7701320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fields BA, Ober B, Malchiodi EL, Lebedeva MI, Braden BC, Ysern X, Kim J-K, Shao X, Ward ES, Mariuzza RA. Crystal structure of the Vα domain of a T cell antigen receptor. Science (Wash DC) 1995;270:1821–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia KC, Degano M, Stanfield RL, Brunmark A, Jackson MR, Peterson PA, Teyton L, Wilson IA. An αβ T cell receptor structure at 2.5 Å and its orientation in the TCR–MHC complex. Science (Wash DC) 1996;274:209–219. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garboczi DN, Ghosh P, Utz U, Fan QR, Biddison WE, Wiley DC. Structure of the complex between human T-cell receptor, viral peptide and HLA-A2. Nature (Lond) 1996;384:134–141. doi: 10.1038/384134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novotny J, Tonegawa S, Saito H, Kranz DM, Eisen HN. Secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure of the T-cell–specific immunoglobulin-like polypeptide chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:742–746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.3.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis MM, Bjorkman PJ. T-cell antigen receptor genes and T-cell recognition. Nature (Lond) 1988;334:395–402. doi: 10.1038/334395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chothia C, Boswell DR, Lesk AM. The outline structure of the T-cell αβ receptor. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1988;7:3745–3755. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White J, Blackman M, Bill J, Kappler J, Marrack P, Gold DP, Born W. Two better cell lines for making hybridomas expressing specific T cell epitopes. J Immunol. 1989;143:1822–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White J, Haskins KM, Marrack P, Kappler J. Use of I region–restricted, antigen-specific T cell hybridomas to produce idiotypically specific anti-receptor antibodies. J Immunol. 1983;130:1033–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yagüe J, White J, Coleclough C, Kappler J, Palmer E, Marrack P. The T cell receptor: the α and β chains define idiotype, and antigen and MHC specificity. Cell. 1985;42:81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White J, Herman A, Pullen AM, Kubo R, Kappler JW, Marrack P. The Vβ-specific superantigen Staphylococcal enterotoxin B: stimulation of mature T cells and clonal deletion in neonatal mice. Cell. 1989;56:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90980-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haskins K, Kubo R, White J, Pigeon M, Kappler J, Marrack P. The major histocompatibility complex– restricted antigen receptor in T cells. I. Isolation with a monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1149–1169. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.4.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubo RT, Born W, Kappler JW, Marrack P, Pigeon M. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody which detects all murine αβ T cell receptors. J Immunol. 1989;142:2736–2742. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leo O, Foo M, Sachs DH, Samelson LE, Bluestone JA. Identification of a monoclonal antibody specific for a murine T3 polypeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1374–1378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dialynas D, Quan Z, Wall K, Pierres A, Quintans J, Loken M, Pierres M, Fitch F. Characterization of the murine T cell surface molecule, designated L3T4, identified by monoclonal antibody GK-1.5: similarity of L3T4 to the human Leu 3/T4 molecule and the possible involvement of L3T3 in class II MHC antigen reactivity. J Immunol. 1983;133:2445–2451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kappler JW, Skidmore B, White J, Marrack P. Antigen-inducible, H-2–restricted, interleukin-2–producing T cell hybridomas: lack of independent antigen and H-2 recognition. J Exp Med. 1981;153:1198–1214. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.5.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker E, Warner N, Chestnut R, Kappler J, Marrack P. Antigen-specific, I region, restricted interactions between tumor cell lines and T cell hybridomas. J Immunol. 1982;128:2164–2169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watson J. Continuous proliferation of murine antigen-specific helper T lymphocytes in culture. J Exp Med. 1979;150:1510–1519. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.6.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mossman T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxic assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–57. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loh EY, Elliot JF, Cwirla S, Lanier LL, Davis MM. Polymerase chain reaction with single-sided specificity: analysis of T cell receptor δ chain. Science (Wash DC) 1989;243:217–220. doi: 10.1126/science.2463672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imai K, Kanno M, Kimoto H, Shigemoto K, Yamamoto S, Taniguchi M. Sequence and expression of transcripts of the T-cell antigen receptor α-chain gene in a functional, antigen-specific suppressor T-cell hybridoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8708–8712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borgulya P, Kishi H, Uematsu Y, von Boehmer H. Exclusion and inclusion of α and β T cell receptor alleles. Cell. 1992;69:529–537. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90453-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar V, Urban JL, Hood L. In individual T cells one productive α rearrangement does not appear to block rearrangement at the second allele. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2183–2188. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Letourneur F, Malissen B. Derivation of a T cell hybridoma variant deprived of functional T cell receptor α and β chain transcripts reveals a nonfunctional α-mRNA of BW5147 origin. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:2269–2274. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830191214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Candéias S, Katz J, Benoist C, Mathis D, Haskins K. Islet-specific T-cell clones from nonobese diabetic mice express heterogeneous T-cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6167–6170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kappler J, White J, Kozono H, Clements J, Marrack P. Binding of a soluble αβ T-cell receptor to superantigen/major histocompatibility complex ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8462–8466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller AD, Rosman GJ. Improved retroviral vectors for gene transfer. Biotechniques. 1989;7:980–990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markowitz D, Goff S, Bank A. Construction and use of a safe and efficient amphotropic packaging cell line. Virology. 1988;167:400–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller AD, Buttimore C. Redesign of retrovirus packaging cell lines to avoid recombination leading to helper virus production. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2895–2902. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.8.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kozono H, White J, Clements J, Marrack P, Kappler J. Production of soluble MHC class II proteins with covalently bound single peptides. Nature (Lond) 1994;369:151–154. doi: 10.1038/369151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhattacharya A, Dorf ME, Springer TA. A shared alloantigenic determinant on Ia antigens encoded by the I-A and I-E subregions: evidence for I region gene duplication. J Immunol. 1981;127:2488–2495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hortin G, Boime I. Miscleavage at the presequence of rat preprolactin synthesized in pituitary cells incubated with a threonine analog. Cell. 1981;24:453–461. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schauer I, Emr S, Gross C, Schekman R. Invertase signal and mature sequence substitutions that delay intercompartmental transport of active enzyme. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1664–1675. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagahora H, Fujisawa H, Jigami Y. Alterations in the cleavage site of the signal sequence for the secretion of human lysozyme by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . FEBS Lett. 1988;238:329–332. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80506-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nothwehr SF, Gordon JI. Eukaryotic signal peptide structure/function relationships. Identification of conformational features which influence the site and efficiency of co-translational proteolytic processing by site-directed mutagenesis of human pre (delta pro) apolipoprotein A-II. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3979–3987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fikes JD, Barkocy-Gallagher GA, Klapper DG, Bassford PJ., Jr Maturation of Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein by signal peptidase I in vivo. . J Biol Chem. 1990;265:3417–3423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ping J, Schildbach JF, Shaw S-Y, Quertermous T, Novotny J, Bruccoleri R, Margolies MN. Effect of heavy chain signal peptide mutations and NH2-terminal chain length on binding of anti-digoxin antibodies. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23000–23007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Reilly, D.R., L.K. Miller, and V.A. Luckow. 1992. Baculovirus Expression Vectors: A Laboratory Manual. W.H. Freeman and Co., New York. 217.

- 50.Fremont DH, Rees WA, Kozono H. Biophysical studies of T-cell receptors and their ligands. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson IA, Stanfield RL. Antibody–antigen interactions: new structures and new conformational changes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1994;4:857–867. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(94)90267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panka DJ, Mudgett-Hunter M, Parks DR, Peterson LL, Herzenberg LA, Haber E, Margolies MN. Variable region framework differences result in decreased or increased affinity of variant anti-digoxin antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3080–3084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaw S-Y, Margolies MN. A spontaneous variant of an antidigoxin hybridoma antibody with increased affinity arises from a heavy chain signal peptide mutation. Mol Immunol. 1992;29:525–529. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(92)90010-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arden B, Clark SP, Kalbelitz D, Mak TW. Mouse T-cell receptor variable gene segment families. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:501–530. doi: 10.1007/BF00172177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]