Abstract

The pre-B cell receptor is a key checkpoint regulator in developing B cells. Early events that are controlled by the pre-B cell receptor include positive selection for cells express membrane immunoglobulin heavy chains and negative selection against cells expressing truncated immunoglobulins that lack a complete variable region (Dμ). Positive selection is known to be mediated by membrane immunoglobulin heavy chains through Igα-Igβ, whereas the mechanism for counterselection against Dμ has not been determined. We have examined the role of the Igα-Igβ signal transducers in counterselection against Dμ using mice that lack Igβ. We found that Dμ expression is not selected against in developing B cells in Igβ mutant mice. Thus, the molecular mechanism for counterselection against Dμ in pre-B cells resembles positive selection in that it requires interaction between mDμ and Igα-Igβ.

The object of B lymphocyte development is to produce cells with a diverse group of clonally restricted antigen receptors that are not self reactive (1). Antigen receptor diversification is achieved through regulated genomic rearrangements that result in the random assembly of Ig gene segments into productive transcription units (2, 3). These gene rearrangements are in large part regulated by the preB cell receptor (BCR)1.

B cells undergoing Ig heavy chain gene rearrangements (pre-B) can express at least two types of BCRs. One form of the receptor is composed of membrane immunoglobulin heavy chain (mIgμ), λ5, V–pre-B, and Igα-Igβ, and is referred to as the pre-BCR (4–6). A second form of the preB cell receptor, known as the Dμ pre-BCR (7), is found only in pre-B1 cells (8) and contains truncated mIgμ chains lacking a VH domain (mDμ). mDμ is produced by Ig genes that have rearranged DJH gene segments in reading frame (RF) 2 producing an in-frame start codon and a truncated transcription unit (7). Like authentic mIgμ, mDμ is a membrane protein that forms a complex with λ5, V–pre-B, and Igα-Igβ, and in tissue culture cell lines the Dμ pre-BCR can activate cellular signaling responses (9–14). But despite its ability to activate nonreceptor tyrosine kinases, Dμ preBCR producing pre-B cells are selected against by a process that is mediated through the transmembrane domain of the mDμ protein (15). In contrast, pre-B cells that express intact mIgμ containing pre-BCRs are positively selected. Counterselection is reflected in the relative lack of mature B cells that express mIgμ in RF2 (15–17). The mechanism by which mDμ activates counterselection has not been defined, but is known to require expression of syk (18). Here we report on experiments showing that Igβ is essential for counterselection against mDμ in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Igβ−/−, mIgμ, and Bcl-2 transgenic strains have been previously described and were maintained by backcrossing with BALB/c mice under specific pathogen-free conditions (19–21). All experiments were performed with 4–8-wk-old female mice.

Fluorescence Analysis and Cell Sorting.

Single cell suspensions prepared from bone marrow or spleen were stained with PE-labeled anti-B220 and FITC-labeled anti-CD43 (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) or FITC-labeled anti-IgM, and analyzed on a FACScan®. For cell sorting, bone marrow cells from four to six mice were stained with the same reagents and separated on a FACSvantage®. CD43+B220− and CD43+B220+ cells were collected based on gating with RAG-1−/− controls.

DNA and PCR.

Total bone marrow DNA was prepared for PCR as previously described (22). DNA from sorted cells was prepared for PCR in agarose plugs (23). Primers for VH–DJH and DH–JH rearrangement were as in reference 22; these primers are mouse specific and do not detect the human Igμ transgene. All experiments were performed a minimum of three times with two independently derived DNA samples. Nonrearranging Ig gene intervening sequences were amplified in parallel with other reactions and used as a loading control (22). Amplified DNA was visualized after transfer to nylon membranes by hybridization with a 6-kb EcoR1 fragment that spans the mouse JH region.

Isolation and Sequencing of VH–DJH and DH–JH Joints.

A JH4 primer was combined with either a DH primer or a VHJ558L primer to amplify DJH and VDJH rearrangements, respectively. The primers were: (a) JH4, ACGGATCCGGTGACTGAGGTTCCT; (b) DH, ACAAGCTTCAAAGCACAATGCCTGGCT; and (c) VHJ558L, GCGAAGCTTA(A,G)GCCTGGG(A,G)CTTCAGTGAAG. PCR amplification for DJH joints was for 35 cycles of 0.5 min at 94°C, and 2 min at 72°C; for VDJH joints, it was for 0.5 min at 94°C, 1 min at 68°C, and 1.5 min at 72°C. PCR products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, subcloned into pBluescript, sequenced using an Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) DNA sequencing kit, and analyzed on a genetic analyzer (ABI-310; Applied Biosystems).

Results

mIgM Cannot Induce the Pre-B Cell Transition or Allelic Exclusion in the Absence of Igβ.

Expression of Igβ is required for B cells to efficiently complete Ig VH to DJH gene rearrangements (19). B cells in Igβ−/− mice fail to express normal levels of mIgμ, and B cell development is arrested at the CD43+B220+ pre-B1 stage (19). A similar celltype specific developmental arrest is also found in mice that carry a mutation in the transmembrane domain of mIgμ (24), and mice that fail to complete Ig V(D)J recombination (25–29). In view of the abnormally low levels of mIgμ in Igβ−/− mice, failed pre-B cell development might simply be due to lack of Ig expression.

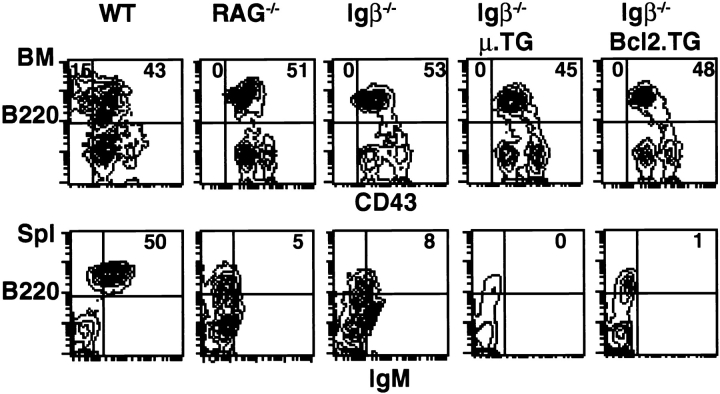

To determine whether mIgμ could induce the pre-B cell transition in the absence of Igβ, we introduced a productively rearranged immunoglobulin gene (20) into the Igβ−/− background (TG.mμ Igβ−/−). We then measured B cell development by staining bone marrow cells with antiCD43 and anti-B220 monoclonal antibodies (30). We found that expression of a pre-rearranged Ig transgene was not sufficient to activate the pre-B cell transition in the absence of Igβ (Fig. 1). TG.mμ Igβ−/− B cells did not develop past the CD43+B220+ pre-B cell stage (Fig. 1). In control experiments, the same mIgμ transgene did induce the appearance of more mature CD43−B220+ pre-B cells in a RAG−/− mutant background where B cell development was similarly arrested at the CD43+B220+ stage (20, 25, 26; data not shown). We conclude that in the absence of Igβ, a productively rearranged mIgμ is unable to activate the pre-B cell transition.

Figure 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of spleen (Spl) and bone marrow cells (BM) from Igβ−/−, transgenic, and wild-type mice. Single-cell suspensions from lymphoid organs of 6-wkold mice were prepared and analyzed on FACScan®. Bone marrow cells were stained with PE–anti-B220 and FITC–anti-CD43. Spleen cells were stained with FITC–anti-IgM and PE– anti-B220. The lymphocyte population was gated according to standard forward- and side-scatter values. The numbers in each quadrant represent the percentages of gated lymphocytes. WT, wild type; RAG −/−, RAG-1 mutant; Igβ −/−, Igβ mutant; Igβ −/− μ.TG, Igβ mutant, mIgμ, transgenic.

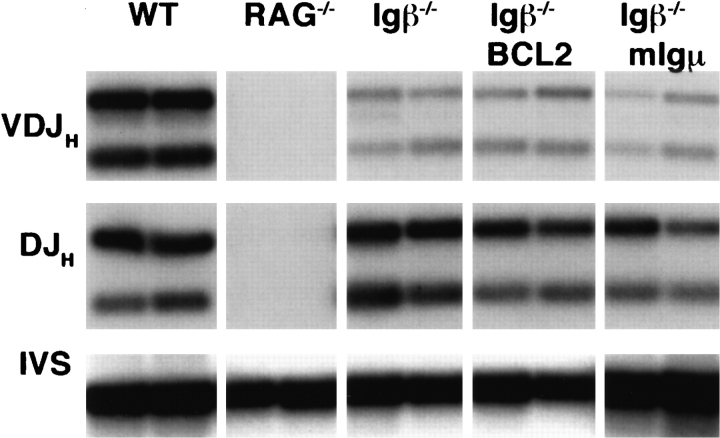

Allelic exclusion is established as early as the CD43+ B220+ stage of B cell development (31–33). This early stage of development is found in the bone marrow of Igβ−/− mice (19). However, we were initially unable to measure allelic exclusion in Igβ mutant mice due to the low efficiency of complete Ig VH to DJH gene rearrangements and absence of surface Igμ expression (19). To determine whether expression of mIgμ could activate allelic exclusion in TG.mμ Igβ−/− mice, we measured inhibition of VH to DJH gene rearrangements by PCR (34). In controls, the mIgμ transgene inhibited VH to DJH gene rearrangement (22), but the same transgene had no effect in the Igβ−/− background (Fig. 2). We had previously shown that the cytoplasmic domains of Igα and Igβ are sufficient to activate allelic exclusion (20, 35). The finding that mIgμ is unable to induce allelic exclusion in the absence of Igβ suggests that Igβ is essential for allelic exclusion.

Figure 2.

Ig gene rearrangements in Igβ−/−, transgenic, and wild-type mice. Bone marrow DNA from 6-wk-old mice was amplified with VH558L, VH7183 (not shown), or DH and JH2 primers. Control primers were from the J-CH1 intervening sequence (IVS) (22).

Igβ Is Required for RF2 Counterselection.

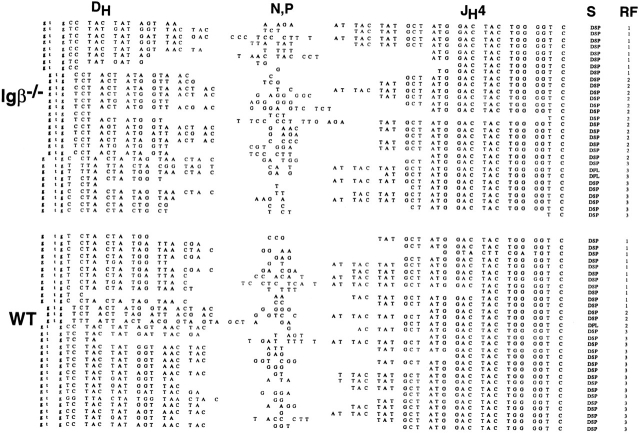

Igs with DH joined to JH in RF2 are rarely found in mature B cells (15–17). Genetic experiments in mice have shown that counterselection against RF2 requires the transmembrane domain of mIgμ and the syk tyrosine kinase (15, 18). To determine whether counterselection is mediated through Igβ, we sequenced DJH joints amplified from sorted CD43+B220+ pre-B cells from Igβ−/− mice and controls. In control samples, only 10% of the DJH joints were in RF2 (Fig. 3), which is in agreement with similar measurements performed in other laboratories (15–17, 31–33). In contrast, there was no counterselection in the bone marrow cells of Igβ−/− mice; 13 out of 30 DJH joints were in RF2 with the remainder being distributed in RF1 and 3 (Fig. 3). Thus, in the absence of Igβ, there was no RF2 counterselection at the level of DJH rearrangements in CD43+B220+ cells in the bone marrow.

Figure 3.

Nucleotide sequences of DH–JH joints from Igβ−/− and wild-type sorted bone marrow B cells. DH segment, N or P nucleotides, and JH4 segment sequences are shown. The number of DJH4 joints in DH RF 1, 2, or 3 are noted. Stop codons in DH segments are underlined.

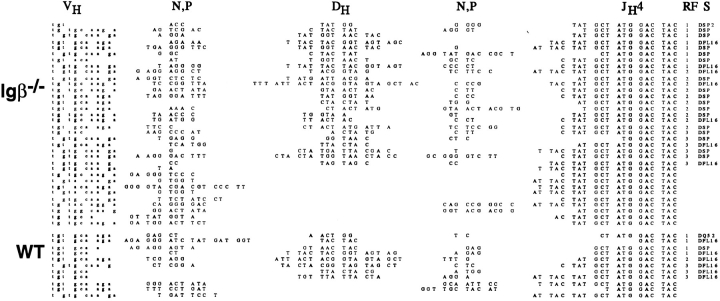

VH to DJH joining and counterselection are normally completed in CD43+B220+ pre-B cells (31–33), but in Igβ−/− mice, VH to DJH joining is inefficient (19). To determine whether RF2 was counterselected in the few Igβ mutant B cells that completed VH to DJH rearrangements, we amplified and sequenced VHJ558L-DJH4 joints from unfractionated bone marrow cells (Fig. 4). As with the DJH joints, we found no evidence for counterselection against RF2 in VDJH joints in Igβ−/− B cells. 10/33 VHJ558LDJH4 joints sequenced from Igβ−/− mice were in RF2. By contrast, RF2 was only found in 1 of 11 mature Ig's in the controls. The VDJH and DJH Igβ−/− joints otherwise resembled the wild type in the number of N and P nucleotides as well as in the extent of nucleotide deletion (Figs. 3 and 4). We conclude that there was no selection against RF2 in the absence of Igβ, and that the absence of Igβ has no significant impact on the mechanics of recombination as measured by the variability of the joints.

Figure 4.

Nucleotide sequences of V(D)J (VH558L to DJH4) joints from Igβ−/− and wild-type bone marrow B cells. DH segment, N or P nucleotides, and JH4 segment sequences are shown. The number of DJH4 joints in DH RF 1, 2, or 3 are noted. Stop codons in DH segments are underlined, and the DH segments used (S) are indicated.

Discussion

The transmembrane domain of mIgμ is required to produce the signals that mediate several antigen-independent events in developing B cells, including allelic exclusion and the pre-B cell transition (24, 36–39). However, mIgμ itself is insufficient for signal transduction (40), and it requires the Igα and Igβ signaling proteins to activate B cell responses in vitro and in vivo.

The earliest developmental checkpoint regulated by IgαIgβ appears to involve either activation of cellular competence to complete VH to DJH rearrangements, or positive selection for cells that express mIgμ (19). In the next phase of the B cell pathway, the same transducers are necessary (Fig. 2) and sufficient to produce the signals that activate allelic exclusion and the pre-B cell transition (19, 20, 35, 41). In the present report, we show that in addition to these functions, Igα-Igβ transducers are also necessary for negative selection against Dμ.

Two models have been proposed to explain counterselection against mDμ. The first model states that mDμ is toxic, and that cells expressing this protein are deleted by a mechanism that involves inhibition of proliferation (31). A second theory postulates that Dμ proteins produce the signal for heavy chain allelic exclusion and block the completion of productive heavy chain gene rearrangements (15). According to this second model, cells expressing mDμ are then unable to continue along the B cell pathway. Support for the active signaling model comes from three sets of observations: (a) that there is no counterselection in the absence of a Igμ transmembrane exon (15); (b) that there is no RF counterselection in the absence of syk (18); and (c) that there is no counterselection in early CD43+B220+ B cell precursors in the absence of λ5 (33). These experiments partially define the receptor structure for counterselection as composed of mDμ associated with λ5. Our observation that negative selection against Dμ does not occur in the absence of Igβ supports the signaling model, and identifies Igα-Igβ as the transducers that activate counterselection possibly by linking mDμ to nonreceptor tyrosine kinases.

Why does the expression of the Dμ pre-BCR lead to arrested development, whereas mature mIgμ in the same complex activates positive selection in early B cells? Both signals are produced in CD43+B220+ pre-B cells, both require λ5 (33, 39, 42), and the Igα-Igβ coreceptors (19, 41), and both are transmitted through a cascade that induces syk (18, 43). One way to explain the difference between the cellular response to mDμ pre-BCR and mIgμ pre-BCR expression might be an inability of Dμ to pair with conventional κ or λ Ig light chains (14). According to this model, cells expressing mDμ should be trapped in the CD43−B220+ preB cell compartment since B cell development can progress to the CD43−B220+ stage in the absence of conventional light chains (44, 45). However, elegant single cell sorting experiments have shown that mDμ-producing cells are selected against before this stage in CD43+B220+ pre-B cells (33, 42). Thus, the idea that abnormal pairing of mDμ with light chains is responsible for counterselection fails to take into account the observation that counterselection normally occurs independently of light chain gene rearrangements.

Two alternative explanations for the disparate cellular responses to the Dμ pre-BCR and the mIgμ pre-BCR are: (a) that there are qualitative differences between signals generated by a mDμ and a mIgμ receptor complex, and (b) pre-B-I cells that contain DJH rearrangements are in a different stage of differentiation than pre-B-II cells that have completed VDJH and express mIgμ (8). An example of two qualitatively distinct signals resulting in alternative biologic responses has been found in the highly homologous TCR receptor (46, 47). TCR interaction with ligand can produce either anergy or activation, depending on the affinity of the TCR for the peptide-MHC complex (48). High affinity ligands that produce T cell responses fully activate CD3 tyrosine phosphorylation, whereas peptides that induce anergy bind with low affinity and induce a reduced level of CD3 phosphorylation. The low level CD3 phosphorylation induced by the anergizing peptides is associated with less than optimal ZAP-70 kinase activation (46, 47).

Less is known about the physiologic responses activated by Igα-Igβ in developing B cells, but experiments in transgenic mice have shown that early B cell development requires tyrosine phosphorylation of Igβ (20), and by inference, receptor cross-linking. Although the cytoplasmic domains Igα and Igβ appear to have redundant functions in allelic exclusion and the pre-B cell transition (20, 35), neither Igα, (41) nor Igβ (Papavasiliou, N., and M.C. Nussenzweig, manuscript in preparation) alone are able to fully restore B cell development in the bone marrow, suggesting that there are specific functions for Igα and Igβ, or the IgαIgβ heterodimer. Biochemical support for the idea that individual coreceptors could have unique biologic functions also comes from transfection experiments in B cell lines (49–51) and from the observation that the cytoplasmic domains of Igα and Igβ bind to different sets of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases (52).

We would like to propose that positive and negative selection in developing B cells, like activation and anergy in T cells, may be mediated by differential phosphorylation of Igα and Igβ in the pre-BCR. Given the requirement for cross-linking in pre-BCR activation, the mechanism that produces the proposed differential phosphorylation of the mDμ and mIgμ pre-BCRs may be a function of their affinities for the cross-linker.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Nussenzweig laboratory for their helpful suggestions and advice.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and by National Institutes of Health grants to Dr. Nussenzweig.

1 Abbreviations used in this paper: BCR, B cell receptor; mIgμ, membrane immunoglobulin heavy chain; RF, reading frame.

References

- 1.Rajewsky K. Clonal selection and learning in the antibody system. Nature (Lond) 1996;381:751–758. doi: 10.1038/381751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature (Lond) 1983;302:575–581. doi: 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alt FW, Yancopoulos GD, Blackwell KT, Wood E, Boss M, Coffman R, Rosenberg N, Tonegawa S, Baltimore D. Ordered rearrangements of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region segments. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1984;3:1209–1219. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pillai S, Baltimore D. Formation of disulfide linked μ2ω2 tetramers by the 18 KD ω-immunoglobulin light chain. Nature (Lond) 1987;329:172–174. doi: 10.1038/329172a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karasuyama H, Kudo A, Melchers F. The proteins encoded by V pre-B and λ5 pre–B cell specific genes can associate with each other and with μ heavy chain. J Exp Med. 1990;172:969–972. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsubata T, Reth MG. The products of the pre–B cell specific genes (λ5 and V pre-B) and the immunoglobulin μ chain form a complex that is transported to the cell surface. J Exp Med. 1990;172:973–976. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reth MG, Alt FW. Novel immunoglobulin heavy chains are produced from DJHgene segment rearrangements in lymphoid cells. Nature (Lond) 1984;312:418–423. doi: 10.1038/312418a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolink A, Melchers F. Molecular and cellular origins of B lymphocyte diversity. Cell. 1991;66:1081–1094. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90032-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nomura J, Matsuo T, Kubola F, Kimoto M, Sakaguchi N. Signal transmission through the B cell specific MB-1 molecule at the pre–B cell stage. Int Immunol. 1991;3:117–126. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Misener V, Downey GP, Jongstra J. The immunoglobulin light chain related protein λ5 is expressed on the surface of pre–B cell lines and can function as a signaling molecule. Int Immunol. 1991;3:1–8. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.11.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takemori T, Mizuguchi J, Miyazoe I, Nakanishi M, Shigemoto K, Kimoto H, Shirasawa T, Maruyama N, Taniguchi M. Two types of μ chain complexes are expressed during differentiation from pre–B to mature B cells. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1990;9:2493–2500. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsubata T, Tsubata R, Reth MG. Cross-linking of the cell surface immunoglobulin (μ surrogate light chain complex) on pre–B cells induces activation of V gene rearrangements at the immunoglobulin κ locus. Int Immunol. 1992;4:637–641. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsutsumi A, Terajima J, Jung W, Ransom J. Surface μ heavy chain expressed on pre–B lymphomas transduces Ca++signals but fails to cause arrest of pre–B cell lymphomas. Cell Immunol. 1992;139:44–57. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90098-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horne MC, Roth PE, DeFranco AL. Assembly of the truncated immunoglobulin heavy chain Dμ into antigen receptor-like complexes in pre–B cells but not in B cells. Immunity. 1996;4:145–158. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80679-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu H, Kitamura D, Rajewsky K. B cell development regulated by gene rearrangement: arrest of maturation by membrane-bound Dμ protein and selection of DHelement reading frames. Cell. 1991;65:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90406-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meek K. Analysis of junctional diversity during B lymphocyte development. Science (Wash DC) 1990;250:820–823. doi: 10.1126/science.2237433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaartinen M, Makela O. Reading of D genes in variable frames as a source of antibody diversity. Immunol Today. 1985;6:324–330. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(85)90127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng AM, Rowley B, Pao W, Hayday A, Bolen JB, Pawson T. Syk tyrosine kinase required for mouse viability and B cell development. Nature (Lond) 1995;378:303–306. doi: 10.1038/378303a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong S, Nussenzweig MC. Regulation of an early developmental checkpoint in the B cell pathway by Igβ. Science (Wash DC) 1996;272:411–414. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papavasiliou F, Misulovin Z, Suh H, Nussenzweig MC. The role of Igβ in precursor B cell transition and allelic exclusion. Science (Wash DC) 1995;268:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.7716544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaux DL, Cory S, Adams J. Bcl-2 gene promotes haemopoietic cell survival and cooperates with c-myc to immortalize pre–B cells. Nature (Lond) 1988;335:440–442. doi: 10.1038/335440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costa TEF, Suh H, Nussenzweig MC. Chromosomal position of rearranging gene segments influences allelic exclusion in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2205–2208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petree HP, Livak F, Burtrum D, Mazel S. T cell receptor gene recombination patterns and mechanisms: cell death, rescue, and T cell production. J Exp Med. 1995;182:121–127. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. A B cell deficient mouse by targeted disruption of the membrane exons of the immunoglobulin μ chain gene. Nature (Lond) 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson RS, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou VE. RAG-1 deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam K-P, Oltz EM, Stewart V, Mendelsohn M, Charron J, Datta M, Young F, Stall AM, Alt FW. RAG-2 deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ehlich A, Schaal S, Gu H, Kitamura D, Muller W, Rajewsky K. Immunoglobulin heavy and light chain genes rearrange independently at early stages of B cell development. Cell. 1993;72:695–704. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90398-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nussenzweig A, Chen C, Soares V, Sanchez M, Sokol K, Nussenzweig MC, Li GC. Requirement for Ku80 in growth and immunoglobulin V(D)J recombination. Nature (Lond) 1996;383:551–555. doi: 10.1038/382551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu C, Bogue MA, Lim D, Hasty P, Roth DB. Ku86-deficient mice exhibit severe combined immunodeficiency and defective processing of V(D)J recombination intermediates. Cell. 1996;86:379–389. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardy RR, Carmack CE, Shinton SA, Kemp JD, Hayakawa K. Resolution and characterization of proB and pre–pro-B cell stages in normal mouse bone marrow. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1213–1225. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haasner D, Rolink A, Melchers F. Influence of surrogate light chain on DHJH-reading frame 2 suppression in mouse precursor B cells. Int Immunol. 1994;6:21–30. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehlich A, Martin V, Muller W, Rajewsky K. Analysis of the B cell progenitor compartment at the level of single cells. Curr Biol. 1994;4:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loffert D, Ehlich A, Muller W, Rajewsky K. Surrogate light chain expression is required to establish immunoglobulin heavy chain allelic exclusion during early B cell development. Immunity. 1996;4:133–144. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80678-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlissel MS, Corcoran LM, Baltimore D. Virus-transformed pre–B cells show ordered activation but not inactivation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and transcription. J Exp Med. 1991;173:711–720. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papavasiliou F, Jancovic M, Suh H, Nussenzweig MC. The cytoplasmic domains of Igα and Igβ can independently induce the pre–B cell transition and allelic exclusion. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1389–1394. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nussenzweig MC, Schmidt EV, Shaw AC, Sinn E, Campos-Torres J, Mathew-Prevot B, Pattengale PK, Leder P. A human immunoglobulin gene reduces the incidence of lymphomas in c-Myc–bearing transgenic mice. Nature (Lond) 1988;336:446–450. doi: 10.1038/336446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nussenzweig MC, Shaw AC, Sinn E, Danner DB, Holmes KL, Morse HC, Leder P. Allelic exclusion in transgenic mice that express the membrane form of immunoglobulin μ. Science (Wash DC) 1987;236:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.3107126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manz J, Denis K, Witte O, Brinster R, Storb U. Feedback inhibition of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement by membrane mu, but not by secreted mu heavy chains (erratum published 169:2269) J Exp Med. 1988;168:1363–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitamura D, Rajewsky K. Targeted disruption of mu chain membrane exon causes loss of heavy-chain allelic exclusion. Nature (Lond) 1992;356:154–156. doi: 10.1038/356154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costa TE, Franke RR, Sanchez M, Misulovin Z, Nussenzweig MC. Functional reconstitution of an immunoglobulin antigen receptor in T cells. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1669–1676. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.6.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torres RM, Flaswinkiel H, Reth M, Rajewsky K. Aberrant B cell development and immune response in mice with a compromised BCR complex. Science (Wash DC) 1996;272:1804–1808. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loffert D, Schaal S, Ehlich A, Hardy RR, Zou YR, Muller W, Rajewsky R. Early B-cell development in the mouse: insights from mutations introduced by gene targeting. Immunol Rev. 1994;137:135–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1994.tb00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner M, Mee PJ, Costello PS, Williams O, Price AA, Duddy LP, Furlong MT, Geahlen RL, Tybulewicz VL. Perinatal lethality and blocked B-cell development in mice lacking the tyrosine kinase Syk. Nature (Lond) 1995;378:298–302. doi: 10.1038/378298a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spanopoulou E, Roman CAJ, Corcoran LM, Schlissel MS, Silver DP, Nemazee D, Nussenzweig MC, Shinton SA, Hardy RR, Baltimore D. Functional immunoglobulin transgenes guide ordered B-cell differentiation in Rag-1–deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1030–1042. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young F, Ardman B, Shinkai Y, Lansford R, Blackwell TK, Mendelsohn M, Rolink A, Melchers F, Alt FW. Influence of Immunoglobulin heavy- and light-chain expression on B-cell differentiation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1043–1057. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sloan-Lancaster J, Shaw AS, Rothbard JB, Allen PM. Partial T cell signaling: altered phospho-zeta and lack of zap-70 recruitment in APL induced T cell anergy. Cell. 1994;79:913–922. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madrenas J, Wange RL, Wang JL, Isakov N, Samelson LE, Germain RN. Zeta phosphorylation without ZAP-70 activation induced by TCR antagonists or partial agonists. Science (Wash DC) 1995;267:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.7824949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyons DS, Lieberman SA, Hampl J, Boniface JJ, Chien Y, Berg LJ, Davis MM. A TCR binds to antagonist ligands with lower affinities and faster dissociation rates than to agonists. Immunity. 1996;5:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim K-M, Alber G, Weiser P, Reth M. Differential signaling through the Ig-α and Ig-β components of the B cell antigen receptor. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:911–916. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanchez M, Misulovin Z, Burkhardt AL, Mahajan S, Costa T, Franke R, Bolen JB, Nussenzweig M. Signal transduction by immunoglobulin is mediated through Igα and Igβ. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1049–1056. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luisiri P, Lee YJ, Eisfelder BJ, Clark MR. Cooperativity and segregation of function within the Ig-alpha/ beta heterodimer of the B cell antigen receptor complex. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5158–5163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark MR, Campbell KS, Kazlauskas A, Johnson SA, Hertz M, Potter TA, Pleiman C, Cambier JC. The B cell antigen receptor complex: association of Ig-alpha and Ig-beta with distinct cytoplasmic effectors. Science (Wash DC) 1992;258:123–126. doi: 10.1126/science.1439759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]