Abstract

We developed and evaluated real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays for detecting Wuchereria bancrofti DNA in human blood and in mosquitoes. An assay based on detection of the W. bancrofti “LDR” repeat DNA sequence was more sensitive than an assay for Wolbachia 16S rDNA. The LDR-based assay was sensitive for detecting microfilarial DNA on dried membrane filters or on filter paper. We also compared real-time PCR with conventional PCR (C-PCR) for detecting W. bancrofti DNA in mosquito samples collected in endemic areas in Egypt and Papua New Guinea. Although the two methods had comparable sensitivity for detecting filarial DNA in reference samples, real-time PCR was more sensitive than C-PCR in practice with field samples. Other advantages of real-time PCR include its high-throughput capacity and decreased risk of cross-contamination between test samples. We believe that real-time PCR has great potential as a tool for monitoring progress in large-scale filariasis elimination programs.

INTRODUCTION

Bancroftian filariasis (caused by the nematode parasite Wuchereria bancrofti) is a serious tropical disease that can lead to chronic, disabling conditions such as lymphedema, elephantiasis, and genital deformities. Microscopy has been used since the time of Manson in the 19th century to show microfilariae in human blood and to detect filarial larvae in mosquitoes.1 Recent diagnostic advances in lymphatic filariasis (LF) have included development of sensitive immunoassays for detecting parasite antigens or antibodies in human blood2,3 and methods for detecting parasite DNA in blood and mosquitoes.4–15 These advances are timely in view of the diagnostic needs of the Global Program for Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis (GPELF), which aims to eliminate filariasis as a public health problem in 83 countries by the year 2020.16–18 GPELF has relied heavily on antigen detection as a method for identifying and mapping areas to be targeted for mass drug administration (MDA). Other tools are needed to effectively monitor the effect of MDA programs and to determine whether filariasis transmission has been interrupted.

Preliminary studies have shown the potential value of molecular xenodiagnosis (MX, detection of parasite DNA in mosquitoes by polymerase chain reaction [PCR]) as a tool for assessing changes in parasite prevalence rates in endemic populations after MDA.13 This method requires collection of representative samples of mosquitoes, efficient isolation of total DNA from mosquito pools, amplification of parasite DNA sequences, and detection of the amplified product. A number of groups have reported success using species-specific primers and PCR to amplify a 188-bp non-coding DNA sequence in W. bancrofti (the “SspI” repeat DNA sequence).4–6 The amplified product can be detected by agarose gel electrophoresis, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), or by DNA test strips.4,13,19 Despite the potential value of this technology, MX has not been a practical choice for use by endemic countries for monitoring filariasis elimination programs; no government’s national filariasis elimination program uses this method for monitoring at this time. The main barrier to widespread adoption of this technology has been that the laboratory infrastructure required for the test is not widely available in filariasis-endemic countries. Technical barriers also should be mentioned. Current methods for MX are inefficient and labor-intensive, and in practice, testing is slow. Therefore, additional work is needed to further simplify MX for filariasis so that it can be a viable, practical tool for monitoring large filariasis elimination programs.

With these goals in mind, the purpose of this study was to explore the use of real-time PCR for detecting filarial DNA. We performed preliminary studies with several target sequences to optimize the real-time PCR assays, and we evaluated the performance of these tests with several types of field samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detection of microfilaremia and filarial antigenemia

Blood samples were collected in the Egyptian villages of Tahoria (TH, in Qalubyia governorate) and Kafr El Bahary (KB; Giza governorate). Approximately 10% of the households were studied each year in each village; different randomly selected household samples (~500 people per village) were studied each year. These repeated, cross-sectional surveys were performed before the first round of MDA and approximately 7–9 months after each round of MDA. Finger prick blood samples were collected for detection of W. bancrofti antigenemia with rapid-format card tests. Subjects with positive filariasis antigen tests were tested for microfilaremia by membrane filtration of 1 mL of venous blood collected between 9:00 pm and 1:00 am. The MF prevalence rate was defined as the number of people with microfilaremia divided by the number of people tested for filarial antigenemia.

DNA isolation

Wuchereria bancrofti DNA was recovered from dried nucleopore membranes (5-μm pore size; Nucleopore, Pleasanton, CA) that had been used to filter venous blood from humans with microfilaremia. DNA isolated from these filters is assumed to be largely parasite DNA with some human DNA from cells trapped on the filters. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted using Wizard Genomic DNA kits (Promega, Madison, WI) into 200 μL of water as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of gDNA was assessed by spectrophotometry (GeneQuant; Pharmacia Biotech, Cambridge, UK). The Wizard Kit was also used to isolate DNA from Dirofilaria immitis and Brugia malayi adult worms and from uninfected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

DNA was also extracted from dried blood in sample application pads from used filarial antigen card tests (ICT Filariasis; AMRAD ICT, French’s Forest, NSW, Australia; and Filariasis Now kits; Binax, Portland, ME). These cards were selected from tests performed in Egypt during the years 2000–2004. Sample application pads contain cells and microfilariae (when present) from 100-μL blood samples. All blood samples were collected between 9:00 pm and 1:00 am. We also studied sample application pads from cards that had been tested with plasma instead of whole blood. Individual pads were carefully lifted off of the cards with sterile surgical blades. To avoid contamination, new blades were used for each pad. Total gDNA was extracted from these pads using QIAamp DNA kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Mosquito collection and DNA extraction

Methods used for collection of blood-engorged Culex pipiens from randomly selected houses in filariasis-endemic areas in Egypt have been previously described.5,14,19 Cx. pipiens mosquitoes were collected from approximately 100 randomly selected houses per village in KB and TH villages in Egypt in 2000 and 2003. The 2000 collection was performed before any MDA for filariasis. The 2003 collection was performed approximately 9 months after the third annual round of the Egyptian government’s MDA program (single dose diethylcarbamazine and albendazole with coverage of ~85% of the eligible population, which excluded children less than 2 years of age and pregnant women). Mosquitoes were tested by household pool with 5 to 25 mosquitoes per pool.

Anopheles punctulatus mosquitoes were collected from villages in a filariasis-endemic area in Papua New Guinea (Usino-Bundi district in Madang province) using CDC light traps without CO2 placed inside houses. Mosquitoes were collected from three villages (Buksak, Iguruwe, and Naru). Female mosquitoes were sorted into two separate pools (engorged or gravid versus host-seeking) from each collection site. One hundred sixty-two mosquito pools from Papua New Guinea were tested in this study. The mean number of mosquitoes per pool was 7.4 (median, 4.5; range, 1–22).

Genomic DNA was isolated from mosquitoes in Egypt and Papua New Guinea as previously described.11 These samples were tested in the endemic country laboratories for W. bancrofti DNA with conventional PCR, and aliquots of the DNA samples were coded and sent to St. Louis for blinded testing by real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR assays for detection of W. bancrofti and Wolbachia DNA

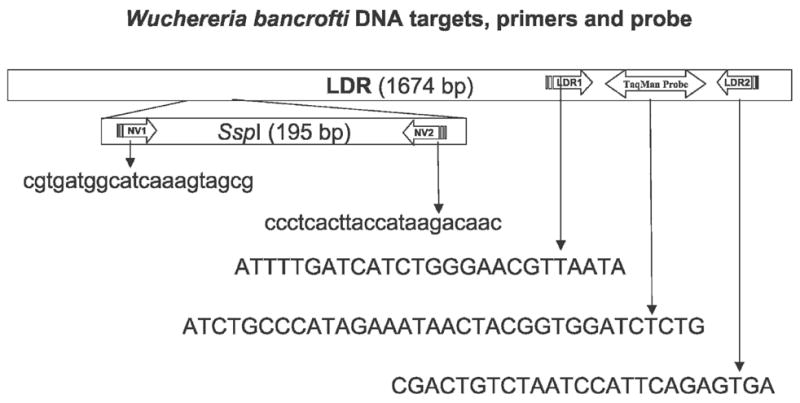

Preliminary studies showed that NV1 and NV2 primers used for amplification of the SspI target sequence by conventional PCR were not suitable for the real-time PCR assay.6 We proceeded to develop real-time PCR assays based on two other target sequences. The first of these, the “long DNA repeat” of W. bancrofti (LDR; GenBank accession no. AY297458) was used as a detection target with blood and mosquito gDNA templates. The second target studied was 16S rDNA (GenBank accession no. AF093510) from Wolbachia endosymbiont bacteria present in filarial worms.20 Conditions were optimized to amplify the LDR and Wolbachia 16S rDNA targets with primers and probes specific for these sequences. The primers (LDR1, LDR2) and TaqMan probe designed by Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for the LDR target sequence are shown in Figure 1. The following sequences were used to detect the Wolbachia 16S rDNA target sequence: forward primer, 5′-ccagcagccgcggtaat-3′; reverse primer, 5′-cgccctttacgcccaat-3′; probe, 5′-cggagagggctagcgttattcggaatt-3′. All primers and probes were synthesized commercially by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The probes were labeled with the reporter dye FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) at the 5′ end and the quencher dye TAMRA (6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine) at the 3′ end. Primers were unlabeled. Real-time PCR reactions were performed with 12.5 μL of TaqMan master mix (Applied Biosystems) along with 450 nmol/L of each primer and 125 nmol/L probe in a final volume of 25 μL. Two microliters of gDNA isolated from mosquitoes, from used nucleopore membranes, or from used filariasis card test sample application pads was mixed with PCR master mix in 96-well MicroAmp optical plates (Applied Biosystems). Extracted gDNA from D. immitis worms, B. malayi worms, Ae. aegypti (uninfected, laboratory reared) mosquitoes, Escherichia coli, and human DNA (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) were also tested (10 and 1 ng per reaction) to determine the specificity of the real-time PCR assay. Thermal cycling and data analysis were done with an ABI Prism 7000 instrument using SDS software (Applied Biosystems). Water was used as a negative control, and DNA from W. bancrofti microfilariae (MF) served as a positive control sample in all real-time PCR runs. All real-time PCR reactions were carried out in duplicate, and cycle threshold (Ct) values for each sample were determined according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All real-time PCR assays with DNA from dried human blood samples or from mosquito pools were performed blindly with coded samples, and results were compared later with results previously obtained by conventional PCR (C-PCR) in Egypt and PNG.

Figure 1.

This figure shows the 195 bp SspI repeat sequence of W. bancrofti within the LDR sequence and the species-specific sequences of primers selected for amplification of SspI (NV1, NV2) by C-PCR and LDR (LDR1, LDR2, TaqMan probe) by real-time PCR. Oligonucleotide sequences are shown in the 5′ to 3′ orientation.

C-PCR assay to detect Wuchereria bancrofti DNA in mosquitoes

C-PCR for detection of the SspI repeat DNA (Gen-Bank accession no. L20344) was performed in endemic country laboratories in Egypt and Papua New Guinea essentially as previously described.6 Briefly, this method uses primers NV1 and NV2 to amplify a 188-bp product in gDNA from W. bancrofti (Figure 1). C-PCR in the endemic country laboratories used a HotStar Taq PCR kit (Qiagen) with NV1 and NV2 primers. PCR thermal cycling conditions for HotStar PCR were 95°C for 15 minutes and 54°C 5 for minutes, followed by 72°C for 30 seconds, 94°C for 20 seconds, and 54°C for 30 seconds for 35 cycles with a 72°C 5-min extension step. Water and “no template” controls were used in all PCR runs. PCR products were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Detection of W. bancrofti microfilariae in night blood samples

Blood was collected by finger prick from consenting volunteers between 9:00 pm and 1:00 am. Microfilariae were detected by microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained 50-μL-thick smears. In some cases, MFs were detected by nucleopore membrane filtration of 1 mL venous blood.5

Ethical clearance

Studies involving human subjects were reviewed and approved by institutional review boards at Washington University School of Medicine and at Ain Shams University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data analysis

The relationship between MF counts by membrane filter and Ct values was assessed by the non-parametric Spearman rank correlation test.

RESULTS

Detection of W. bancrofti and Wolbachia DNA using real-time PCR

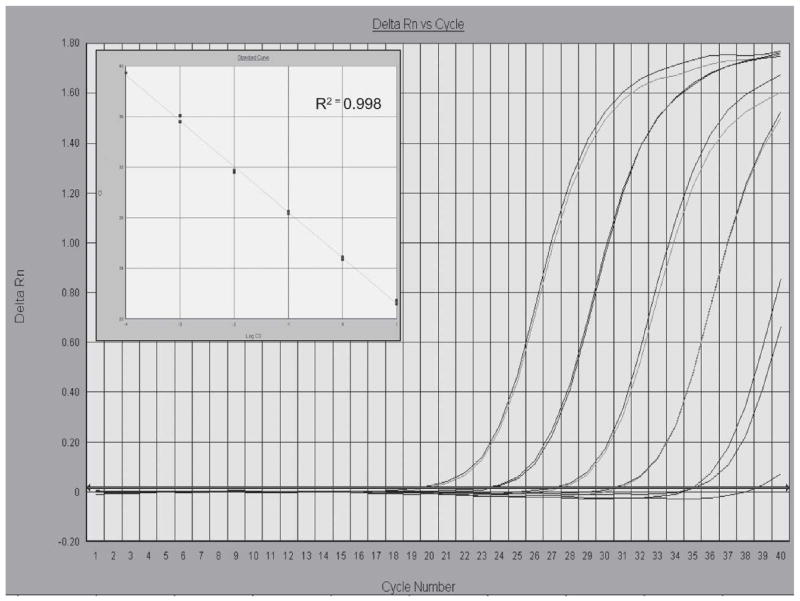

Preliminary technical studies were performed with serial dilutions of gDNA obtained from MF-positive membrane filters. Ct values obtained with the LDR primers and probe were inversely proportional to the amounts of DNA template tested, and reaction efficiencies were close to 100% (slope, −3.56; R2 = 0.98; Figure 2). Serial 10-fold dilutions of gDNA isolated from MF-positive membrane filters were tested by real-time PCR with LDR reagents and by C-PCR with SspI primers to compare the sensitivities of the two methods. The limit of detection (1.4 × 105 dilution factor) was the same for both methods.

Figure 2.

Amplification plots of fluorescence (y-axis) vs cycle number (x-axis) show the analytical sensitivity of the LDR real-time PCR for detecting W. bancrofti DNA. Genomic DNA template from W. bancrofti microfilariae (MF) isolated from membrane filters (10, 1, 0.1, 0.01, 0.001 ng) were tested in duplicate. Cycle threshold values (Ct) (y-axis) were plotted against Log template DNA (x-axis) concentrations (range, 1 pg to 10 ng) to generate a standard curve with reproducible linearity over five orders of magnitude (inset); 1 pg is approximately equivalent to 0.5% of the DNA found in a single W. bancrofti MF (S. Williams, unpublished data).

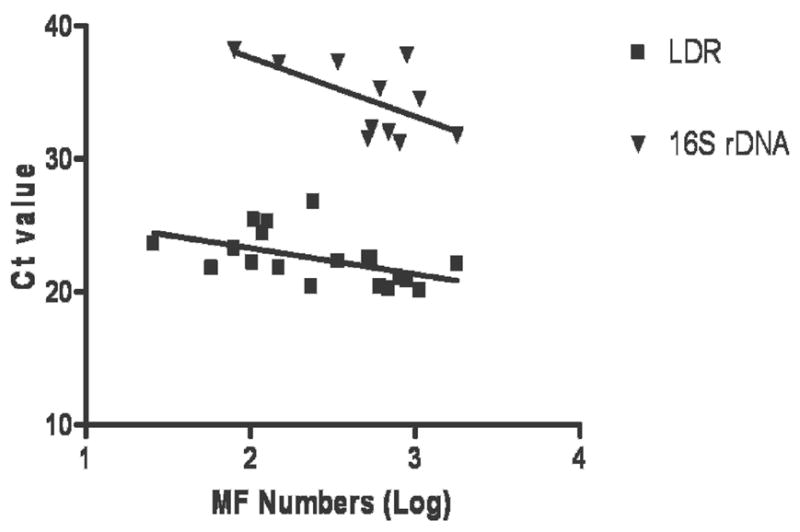

Real-time PCR results obtained with primers and probes specific for the LDR and Wolbachia 16S rDNA target sequences for template from 19 MF-positive membrane filters are shown in Figure 3. MF counts for these filters varied from 26 to 1,794 per mL blood (mean, 447; median, 241). The LDR assay was significantly more sensitive than the Wolbachia assay, both in terms of Ct values and the number of samples with positive signals. Ct values were inversely correlated with MF counts, as expected. However, the relationship was only statistically significant for the LDR assay.

Figure 3.

This graph compares the sensitivity of real-time PCR for detection of W. bancrofti DNA in blood for two target sequences: W. bancrofti LDR and Wolbachia 16S rDNA. Genomic DNA samples were isolated from nucleopore membrane filters containing microfilariae (MF) filtered from night blood samples. Ct values are plotted against Log MF counts (MF/ml). Samples that failed to reach the fluorescence threshold by 40 cycles were considered to be negative, and these were not plotted in the graph. The LDR assay was positive in 19 of 19 samples (100%); Ct values were significantly correlated with MF numbers (R = −0.560, P = 0.013). The 16S rDNA assay detected the target in 11 of 19 samples (56%; correlation between Ct and MF counts: R = −0.436, P = 0.180, not significant).

Specificity of W. bancrofti DNA detection by real-time PCR

To assess the specificity of real-time PCR, 10 and 1 ng of gDNA from human blood, Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, D. immitis adult worms, B. malayi adult worms, and W. bancrofti MF were used as templates for real-time PCR with the LDR primers and probe. Only the gDNA from W. bancrofti MF produced positive signals. Thus, this assay is specific for W. bancrofti DNA. Real-time PCR with primers and probe for Wolbachia 16S rDNA produced positive signals with templates containing W. bancrofti and B. malayi DNA but not E. coli DNA, indicating the assay is specific for Wolbachia DNA.

Sensitivity of real-time PCR for detecting W. bancrofti DNA in dried blood from filariasis antigen card tests

Forty-seven of 193 card test sample application pads with dried blood were positive for W. bancrofti DNA by real-time PCR with LDR reagents (Table 1). Parasite DNA was detected in all 33 samples from subjects with microfilaremia (100%) and in 14 of 70 (20%) sample pads from amicrofilaremic subjects with positive filarial antigen tests. Presumably, some of these subjects had low-level microfilaremia that was not detected by microscopic examination of stained thick blood smears. No parasite DNA was detected in 90 sample application pads from subjects with negative tests for microfilaremia and filarial antigenemia. In addition, no parasite DNA was detected in 12 sample application pads from MF-positive subjects whose antigen card tests had been performed with plasma instead of blood. Thus, we found no evidence of free parasite DNA in plasma from MF carriers.

Table 1.

Sensitivity of real-time PCR in detecting Wuchereria bancrofti (Wb) DNA in dried blood from sample application pads of used filariasis antigen detection cards*

| MF and antigen (Ag) results for ICT cards† | No. of cards tested | No. of ICT sample pads positive for Wb DNA | Percent of ICT sample pads positive for Wb DNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| MF+/Ag+ | 33 | 33 | 100 |

| MF−/Ag+ | 70 | 14 | 20 |

| MF−/Ag− | 90 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 193 | 47 | — |

Card tests used in this study were from human subjects in TH and KB villages in Egypt including persons with microfilaremia (MF) and positive antigen tests (MF+/Ag+), others with positive antigen tests who were amicrofilaremic (MF−/Ag+), and others who were MF and antigen-negative (MF−/Ag−). The card tests were performed at different times (some before and others after initiation of mass drug administration for elimination of lymphatic filariasis in Egypt).

Night blood samples were tested separately for microfilariae (MF, by microscopy) and circulating filarial antigenemia (by card test).

DNA from all of the dried blood samples that had W. bancrofti DNA (detected by real-time PCR with LDR reagents) were retested by real-time PCR with the Wolbachia 16S rDNA primers and probe. Only 7 of 47 (14.8%) of these samples were positive for Wolbachia DNA. This confirmed the lower sensitivity of the Wolbachia-based assay relative to the LDR assay.

Sensitivity of real-time PCR and C-PCR for detecting W. bancrofti DNA in Cx. pipiens and An. punctulatus mosquitoes

Mosquito results are shown in Table 2. Real-time PCR (with LDR reagents) detected many more positive pools than C-PCR. All samples with discordant results were retested by both methods. All real-time PCR results were confirmed. However, many samples that were initially scored as negative by C-PCR and positive by real-time PCR were found to be positive by C-PCR after repeat testing; agreement between the two methods was fairly good when results of repeat C-PCR are considered.

Table 2.

Comparison of real-time PCR and conventional-PCR (C-PCR) for detecting Wuchereria bancrofti (Wb) DNA in pools of Culex pipiens from Egypt and in pools of Anopheles punctulatus from Papua New Guinea

| Detection method | Number of Wb DNA positive pools | Number of Wb DNA negative pools | Percent pools positive for Wb DNA | Percent agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tahoria, Egypt* | ||||

| Real-time PCR | 42 | 180 | 18.9 | — |

| C-PCR | 29 | 193 | 13.1 | 94 |

| Repeat C-PCR | 36 | 186 | 16.2 | 97 |

| Kafr El Bahary, Egypt† | ||||

| Real-time PCR | 78 | 120 | 39.4 | — |

| C-PCR | 40 | 158 | 20.2 | 81 |

| Repeat C-PCR | 62 | 136 | 31.3 | 92 |

| Usino, Papua New Guinea‡ | ||||

| Real-time PCR | 60 | 102 | 37.0 | — |

| C-PCR | 52 | 110 | 32.1 | 95 |

| Repeat C-PCR | 62 | 100 | 38.2 | 99 |

DNA from 222 Cx. pipiens pools were tested.

DNA from 198 Cx. pipiens pools were tested.

DNA from 162 pools of An. punctulatus were tested.

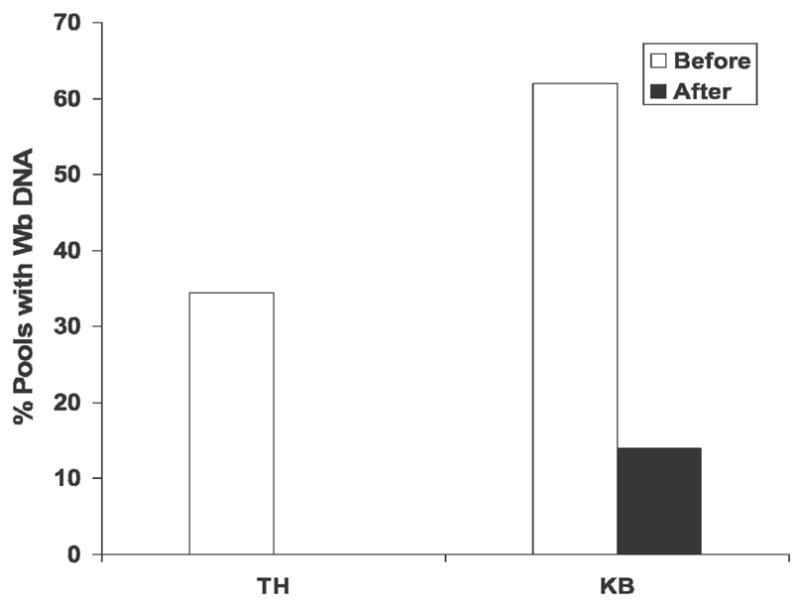

Effects of MDA on mosquito infection rates

Figure 4 shows effects of three rounds of MDA on mosquito pool infection rates for two Egyptian villages. Note that infection parameters were significantly higher in village KB than in TH before the initiation of MDA. MDA had dramatic effects on mosquito pool infection rates in both villages. No infected mosquito pools were detected after three annual rounds of MDA in TH, whereas infections persisted in KB with a 77.5% reduction in the percentage of positive mosquito pools relative to the pre-MDA baseline value. Moreover, percent agreements between LDR assay and C-PCR on mosquito samples after MDA were 100% (TH) and 98% (KB).

Figure 4.

This graph compares the percentage of mosquito pools with W. bancrofti DNA detected by real-time PCR in two sentinel Egyptian villages Tahoria (TH) and Kafr El Bahary (KB) before and after three rounds of MDA with antifilarial medication. Microfilaria prevalence rates as determined by membrane filtration in these villages at these time-points were 4.2% and 0% for TH and 10.4% and 1.4% for KB, respectively. The number of mosquito pools tested before and after MDA were 121 and 100 from TH and 105 and 93 from KB, respectively. No positive mosquito pools were detected in TH after the third round of MDA.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to explore the value of real-time PCR for detecting filarial DNA in field samples. A recent publication from Thailand showed that filarial DNA could be detected by real-time PCR with two probes and melting curve analysis.21 However, the authors did not report results of specificity testing or results obtained with field samples.

In contrast to results reported by Lulitanond et al.,21 our preliminary studies showed that real-time PCR did not work well with NV1 and NV2 primers and a TaqMan probe directed to the SspI target sequence used for C-PCR. Therefore, we focused on studies to optimize conditions for detecting parasite DNA using the LDR and Wolbachia 16S target sequences. Our results showed that the LDR assay was sensitive, specific, and efficient, with a dose–response curve that was linear over a range of five orders of magnitude. We then evaluated the LDR detection assay with a panel of DNA samples isolated from membrane filters with known numbers of W. bancrofti MF visualized by microscopy. It was impressive that all membranes produced positive DNA signals after storage for periods ranging from 6 months to 4 years. LDR Ct values were significantly (inversely) correlated with MF counts, but the correlation was only moderately strong. This may reflect partial degradation of parasite DNA on old membranes, variable recovery of parasite DNA from membranes, or the possible presence of PCR inhibitors on membranes.

The LDR real-time PCR assay was also sensitive for detecting parasite DNA in human blood dried on used ICT card sample application pads. Indeed, PCR detection was more sensitive for detecting infections than microscopy performed with blood from the same subjects, because some samples from amicrofilaremic subjects with positive filarial antigen tests had positive DNA tests. Specificity was excellent; positive tests were not seen with blood samples from amicrofilaremic subjects with negative antigen tests or with blood samples from MF carriers that was collected during the day. The latter result suggests that DNA detected by PCR is derived from intact MF and not from “free DNA” in plasma. The card test results suggest multiple new uses for these cards when they are tested with blood samples collected at times that correspond to peak MF levels. First, selected samples can be tested by real-time PCR to determine whether subjects with positive antigen tests have circulating MF. Second, used cards from different places and times provide a valuable archive of parasite DNA that may be useful for DNA-based studies of drug resistance or parasite polymorphism.

The sensitivity of real-time PCR for detection of Wolbachia 16S DNA was much lower than the LDR assay for detecting filarial DNA. If the two reactions are equally efficient, the difference in Ct values (~10 cycles) suggests at least a 1,000-fold difference in copy number per cell for the two target sequences. Differences in stability of eukaryotic and bacterial DNA sequences on dried filters or differences in efficiency of isolation of DNA template from the parasite and bacteria may have contributed to the difference in sensitivity.22–24 While the number of LDR repeats in W. bancrofti gDNA presumably is constant throughout the parasite life cycle, this may not be the case for the Wolbachia target sequence. Recently, it has been reported that microfilariae have fewer Wolbachia than other parasite stages.25 This would tend to limit the diagnostic value of Wolbachia DNA for detecting MF in blood samples.

Our project used large panels of mosquito DNA extracts from Egypt and Papua New Guinea to compare the sensitivity of real-time PCR (LDR target) with C-DNA (SspI target). The two methods had the same sensitivity with a standard template of isolated parasite DNA in our laboratory in St. Louis. However, the real-time PCR assay was more sensitive for detecting W. bancrofti DNA in field samples relative to C-PCR performed in endemic country laboratories. This evaluation provided a useful, real-world comparison of the two DNA detection methods. In practice, C-PCR requires subjective scoring of bands in agarose gels, and we found that technicians had been reluctant to score very faint or questionable bands as positives. Repeat C-PCR resolved discrepancies in most cases. However, there were a few cases where repeated testing verified discrepancies with some samples only positive by LDR real-time PCR and (a few) others only positive by C-PCR for the SspI sequence. Additional studies are needed to determine whether variability in LDR and SspI repeat sequences account for these discrepancies.

Beyond the technical comparison of the two DNA detection methods, the decreases in Egyptian mosquito pool infection rates documented by LDR real-time PCR after MDA were impressive and consistent with C-PCR results. These results suggest that MDA had a major effect on parasite prevalence rates in the Egyptian villages studied, and they show the potential value of real-time PCR for monitoring the impact of MDA in filariasis elimination programs.

Looking ahead to practicalities, we should point out that real-time PCR is comparable in cost to C-PCR (~$2 per mosquito pool including DNA isolation, target amplification, and detection of amplified product). Costs for the instrumentation and reagents for real-time PCR are decreasing over time; additional research is needed to further optimize methods to reduce costs. However, in terms of the data produced, MX by real-time PCR or C-PCR is far preferable (more sensitive and efficient) to traditional dissection with microscopy for detecting filarial infections in mosquito populations and as a tool for monitoring late stages of filariasis elimination programs. In comparing real-time PCR with C-PCR for this purpose, we favor real-time PCR because of its increased sensitivity with field samples, lower labor requirements, reduced potential for contamination in the laboratory (no need to separately analyze PCR products in the laboratory), and much higher throughput capability. Coupled with advances in mosquito collection methods and methods for DNA isolation, we believe that MX by real-time PCR (perhaps in regional reference laboratories) will prove to be a practical tool for monitoring filariasis elimination programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the efforts of field teams and technical staff at Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt, and at the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research in Madang. We thank K. Curtis for technical help.

Financial support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI 35855.

References

- 1.Grove DI, Warren KS, Mahmoud AA. Algorithms in the diagnosis and management of exotic diseases. VI. The filariases. J Infect Dis. 1975;132:340–352. doi: 10.1093/infdis/132.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weil GJ, Lammie PJ, Weiss N. The ICT filariasis test: a rapid-format antigen test for diagnosis of bancroftian filariasis. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:401–404. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lammie P, Weil G, Rahmah N, Kaliraj P, Steel C, Goodman D, Lakshmikanthan V, Ottesen E. Recombinant antigen based assays for the diagnosis and surveillance of lymphatic filariasis - a multicenter trial. Filaria J. 2004;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams S, Laney S, Bierwert L, Saunders L, Boakye D, Fischer P, Goodman D, Helmy H, Hoti S, Vasuki V, Lammie P, Plichart C, Ramzy R, Ottesen E. Development and standardization of a rapid PCR-based method for the detection of Wuchereria bancrofti in mosquitoes for xenomonitoring the human prevalence of bancroftian filariasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;96:S41–S46. doi: 10.1179/000349802125002356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramzy R, Farid H, Kamal H, Ibrahim G, Morsy Z, Faris R, Weil G. A polymerase chain reaction-based assay for detection of Wuchereria bancrofti in human blood and Culex pipiens. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:156–160. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong M, McCarthy J, Bierwert L, Lizotte-Waniewski M, Chanteau S, Nutman T, Ottesen E, Williams S. A polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of the parasite Wuchereria bancrofti in human blood samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:357–363. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy J, Zhong M, Gopinath R, Ottesen E, Williams S, Nutman T. Evaluation of a polymerase chain reaction-based assay for diagnosis of Wuchereria bancrofti infection. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1510–1514. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.6.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer P, Liu X, Lizotte-Waniewski M, Kamal I, Ramzy R, Williams S. Development of a quantitative, competitive polymerase chain reaction-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of Wuchereria bancrofti DNA. Parasit Res. 1999;85:176–183. doi: 10.1007/s004360050531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbasi I, Hamburger J, Githure J, Ochola J, Agure R, Koech D, Ramzy R, Gad A, Williams S. Detection of Wuchereria bancrofti DNA in patients sputum by the polymerase chain reaction. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:531–532. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kluber S, Supali T, Williams SA, Liebau E, Fischer P. Rapid PCR-based detection of Brugia malayi DNA from blood spots by DNA detection test strips. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:169–170. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bockarie MJ, Fischer P, Williams SA, Zimmerman PA, Griffin L, Alpers MP, Kazura JW. Application of a polymerase chain reaction-ELISA to detect Wuchereria bancrofti in pools of wild-caught Anopheles punctulatus in a filariasis control area in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:363–367. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chanteau S, Luquiaud P, Failloux AB, Williams SA. Detection of Wuchereria bancrofti larvae in pools of mosquitoes by the polymerase chain reaction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:665–666. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman DS, Orelus JN, Roberts JM, Lammie PJ, Streit TG. PCR and Mosquito dissection as tools to monitor filarial infection levels following mass treatment. Filaria J. 2003;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farid HA, Hammad RE, Hassan MM, Morsy ZS, Kamal IH, Weil GJ, Ramzy RM. Detection of Wuchereria bancrofti in mosquitoes by the polymerase chain reaction: a potentially useful tool for large-scale control programmes. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasuki V, Hoti SL, Sadanandane C, Jambulingam P. A simple and rapid DNA extraction method for the detection of Wuchereria bancrofti infection in the vector mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus by Ssp I PCR assay. Acta Trop. 2003;86:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molyneux D. Lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis) elimination: a public health success and development opportunity. Filaria J. 2003;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottesen EA. Major progress toward eliminating lymphatic filariasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1885–1886. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe020136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:202–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmy H, Fischer P, Farid HA, Bradley MH, Ramzy RM. Test strip detection of Wuchereria bancrofti amplified DNA in wild-caught Culex pipiens and estimation of infection rate by a PoolScreen algorithm. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:158–163. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor MJ, Bilo K, Cross HF, Archer JP, Underwood AP. 16S rDNA phylogeny and ultrastructural characterization of Wolbachia intracellular bacteria of the filarial nematode Brugia malayi, B. pahangi, and Wuchereria bancrofti. Exp Parasitol. 1999;91:356–361. doi: 10.1006/expr.1998.4383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lulitanond V, Intapan PM, Pipitgool V, Choochote W, Maleewong W. Rapid detection of Wuchereria bancrofti in mosquitoes by LightCycler polymerase chain reaction and melting curve analysis. Parasitol Res. 2004;94:337–341. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farkas DH, Drevon AM, Kiechle FL, DiCarlo RG, Heath EM, Crisan D. Specimen stability for DNA-based diagnostic testing. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1996;5:227–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon AW, Holland MJ, Burton MJ, West SK, Alexander ND, Aguirre A, Massae PA, Mkocha H, Munoz B, Johnson GJ, Peeling RW, Bailey RL, Foster A, Mabey DC. Strategies for control of trachoma: observational study with quantitative PCR. Lancet. 2003;362:198–204. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13909-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. 1993;362:709–715. doi: 10.1038/362709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGarry HF, Egerton GL, Taylor MJ. Population dynamics of Wolbachia bacterial endosymbionts in Brugia malayi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;135:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]