Abstract

Synthetic CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN), similar to DNA sequences found in certain microorganisms, have shown promise as adjuvants for humans by enhancing immune responses. Since antibodies are often indicators of successful vaccination, it is important to understand how CpG ODN affects human B cells and influences antibody production. Treatment of human B cells with synthetic CpG ODN sequences increased both steady-state Cox-2 mRNA levels and protein expression. B cell receptor stimulation in concert with CpG ODN treatment induced Cox-2 expression and production of prostaglandin E2, well above that seen with CpG ODN alone. Importantly, CpG-induced human B cell IgM and IgG production was attenuated by dual Cox-1/Cox-2 inhibitors and Cox-2 selective inhibitors. Our findings support a key role for CpG ODN-induced human B cell Cox-2 in the production of IgM and IgG antibodies, revealing that drugs that attenuate Cox-2 activity have the potential to reduce optimal antibody response to adjuvants/vaccination.

Keywords: B cells, Antibodies, Cyclooxygenase-2, CpG, NSAIDs and Cox-2 selective inhibitors

Introduction

Toll-like receptor ligands, such as hypomethylated CpG DNA commonly found in bacteria and DNA viruses, elicit innate immune responses. The ability of B lymphocytes to be stimulated by CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN), possibly through Toll-like Receptor 9 (TLR9), implicates their participation in innate immune responses. Exposure of human B cells to CpG DNA increases antigen presentation and costimulation, through the upregulation of class II MHC, CD80, CD86, CD40, and CD54 [1,2]. Stimulation of B cells with CpG ODN also induces increased expression of TLR9, increased production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α and leads to increased IgM and IgG production [1,2,3,4]. CpG ODN can bias immunity towards a type-1 cytokine response and attenuate IgG1 and IgE production, while promoting synthesis of IgM and IgG2a [5,6]. As antibody production is often a hallmark of efficacious vaccines, it is important to understand how an adjuvant such as CpG ODN influences B cell function. Due to problems that occur with other adjuvant strategies, such as those that act through CD40 stimulation [7], understanding the adjuvant activity of CpG ODN becomes increasingly important.

Cyclooxygenases (Cox) exist in two isoforms, Cox-1 and Cox-2, which metabolize arachidonic acid to produce Prostaglandin H2 (PGH2). Cox-1 is constitutively expressed by many types of cells and is important for optimal cell functioning and maintenance of homeostasis. In contrast, Cox-2 expression is induced by certain cytokines and growth factors [8]. Terminal synthases are responsible for conversion of the Cox product, PGH2, to bioactive prostanoids (e.g. prostaglandins and thromboxane). Prostanoids have diverse pro and anti-inflammatory characteristics and profoundly influence immune regulation.

Biphenotypic B/macrophage cells, as well as normal human B lymphocytes, can produce Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [9,10,11]. Cox-2 products such as PGE2 can enhance lymphocyte viability, promote Ig class switching and boost antibody production [11,12,13]. Our recent work has demonstrated that human B cells express Cox-2 and produce PGE2 upon activation through the BCR and via CD40 [10]. We postulated that exposing human B cells to certain microbial products, namely CpG ODN, would also induce Cox-2, and thereby reveal a new pathway for B cell activation. Herein, we demonstrate that human B lymphocyte Cox-2 is induced by CpG ODN stimulation and that its activity is crucial for optimal IgM and IgG production in vitro. These findings have important implications on the use of CpGs as adjuvants in humans and suggest that the use of Cox inhibitors (NSAIDs including Celebrex, indomethacin, etc.) will have dampening effects on antibody production enhanced by CpG DNA.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and culture conditions

Purified human B lymphocytes were cultured in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 5 × 105 M 2-ME, 10 mM HEPES, and 50 μg/mL gentamicin. ODN 2395 5′-TCGTCGTTTTCGGCGCGCGCCG-3′ and ODN 2137 5′-TGCTGCTTTTGTGCTTTTGTGCTT-3′, obtained from the Coley Pharmaceutical Group (Wellesley, MA), ODN c274 5′-TCGTCGAACGTTCGAGATGAT -3′ synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA) and ODN TTAGGG 5′-TTAGGGTTAGGGTTAGGGTTAGGG-3′, a mammalian telomere negative control sequence obtained from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA) were utilized at a concentration of 1 μg/mL for purified B cells and 10 or 20 μg/mL for PBMCs and diluted whole blood cultures. For stimulating B cells through the BCR, rabbit anti-human F(ab′)2 anti-IgM Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) was used at 2 or 10 μg/mL. Arachidonic acid (Nu-Chek Prep, Elysian, MN) was dissolved in 100% ethanol and used at 10 μM in all cultures. B cells were pretreated with 1 μM of choloroquine (InvivoGen), an inhibitor of endosomal acidification, one hour prior to ODN exposure.

B lymphocyte isolation

Peripheral blood was acquired from healthy donors under ethical permission provided by the Research Subjects Review Board at the University of Rochester. After centrifugation, the buffy coat was diluted 1:1 with 1× PBS and subjected to Ficoll-Paque (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) gradient centrifugation. PBMCs were then washed with 1× PBS and resuspended in RPMI 1640 media. Some were then set aside for cultures using only PBMCs. Leukocytes were incubated with anti-CD19 Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min at 4°C on an orbital shaker. CD19 Dynabead cell rosettes were captured using a magnet, while the negatively selected cells were removed. The cell-bead rosettes were washed and resuspended in 2 mL RPMI 1640 media with Detachabead CD19, a polyclonal anti-F(ab′)2 used to disrupt cell-bead interactions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Detachabead was used at 25% of the CD19 Dynabead volume used to capture the B cells. Rosettes were separated into two, 2 mL tubes and placed on an orbital shaker for 1 hr at 4°C. CD19+ cells were washed after removing beads with a magnet and cell number was assessed. By flow cytometry, B cells were found to be >98% CD19+, while <2% expressed CD3 or CD14. B cells were also isolated by negative selection using a MACS kit to the supplier’s specifications (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA). Whole blood was washed two times in 1× PBS, and cultured 1:3 in Iscove’s media (GIBCO/Invitrogen).

Flow cytometric analysis

Purified human B cells were surfaced stained with anti-human CD19 APC, CD27 PE, CD80 FITC or CD69 PE (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). PBMCs were stained with anti-human CD19, anti-human CD3 PE (BD Biosciences), anti-human CD4 FITC (BD Biosciences), anti-human CD14 FITC (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL ), or with anti-human CD56 biotin (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Streptavidin APC (Caltag Laboratories/Invitrogen, Burlingame, CA) was used for secondary detection. Staining was performed at room temperature in 1× PBS buffer supplemented with 0.3% BSA and 0.02% sodium azide for 20 min. For intracellular detection of Cox-2 we utilized anti-human Cox-2 conjugated to FITC or PE (Cayman Chemical) as previously described [10]. Purified human B cells were fixed and permeabilized using a kit (Caltag Laboratories/Invitrogen) according to the supplier’s specifications. Cell samples were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc).

Western blot analysis

Purified normal human B lymphocytes were lysed in NP-40 buffer: 1% IGEPAL, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 10% Protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to obtain whole cell lysate. Protein was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). SDS-PAGE gels (7.5%) were loaded with 10 or 25 μg of protein and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were then blocked with 10% nonfat powdered milk in 1× PBS/0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and incubated with mouse anti-human Cox-2 Ab (Cayman Chemical), mouse anti-human Cox-1 Ab (Cayman Chemical), or mouse anti-total actin (Oncogene Research Products/Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) as described [10]. Membranes were incubated with HRP conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) after washing with PBST. All antibody incubations and washes were performed at 20 °C. Protein on membranes was visualized by autoradiography after incubation with ECL (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences Inc., Boston MA).

Immunofluorescence

Purified human B cells were stained as described above for flow cytometric analysis with anti-human CD19 APC and anti-human Cox-2 FITC antibodies as described previously [10]. Cells were fixed with 0.1% paraformaldehyde and placed on glass microscope slides. B cells were visualized using an Olympus BX51 microscope. Images were collected with a SPOT camera and evaluated using SPOT RT Advanced software (SPOT Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Springs, MI).

Real time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from purified human B cells using a Qiagen RNAeasy mini kit according to the supplier’s protocol. RNA was quantified on a NanoDrop ND-1000 UV/Vis Spectrophotometer. Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) RT was used to reverse transcribe 0.5 to 1 μg of extracted RNA using an oligo (dT) primer. Real time PCR was performed using human Cox-1 sequences 5′-TGGAGACAATCTGGAGCGTCA-3′ and 5′-GGAACTGGACACCGAACAG-3′ and Cox-2 sequences 5′-TCACAGGCTTCCATTGACCAG-3′ and 5′-CCGAGGCTTTTCTACCAGA-3′ as previously described [10]. Human GAPDH sequences 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ and 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ were used as a control. iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used in the real time PCR assay and results were analyzed with Bio-Rad Icycler software as previously described [10]. Cox-1 and Cox-2 mRNA steady-state levels were normalized to GAPDH expression in human B cells. Fold induction was determined through comparison of treated to untreated B cells.

Measurement of prostaglandin production

Purified human B cells (5 × 106 cells/mL) were cultured in 96-well round-bottom plates for 36 hours in the presence of 5 μM of arachidonic acid. In addition to activating stimuli, the dual Cox-1/Cox-2 NSAID inhibitor, indomethacin (also known as Indocin) or a highly Cox-2 selective inhibitor, SC-58125 (a close analogue of Celebrex), was added at the onset of culture. Both drugs were diluted in ethanol, and ethanol was supplemented in media as a vehicle control. Media supernatants from purified human B cells were analyzed using the PGE2-specific enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Cayman Chemical). These assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Measurement of antibody production

Purified human B cells (5 × 105 cells/mL) were cultured in 96-well round-bottom plates for 6 or 7 days with selected stimuli. Arachidonic acid was added to cultures on day 0 at a concentration of 10 μM. Indomethacin was added every day for 6 days and SC-58125 was added on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 at 5, 10 or 20 μM. An ethanol control was included in both systems. Supernatants were harvested on day 6 or 7 and analyzed for the presence of IgM and IgG by ELISA (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) as previously described [10].

Results

CpG ODN induces Cox-2 protein expression in human B cells

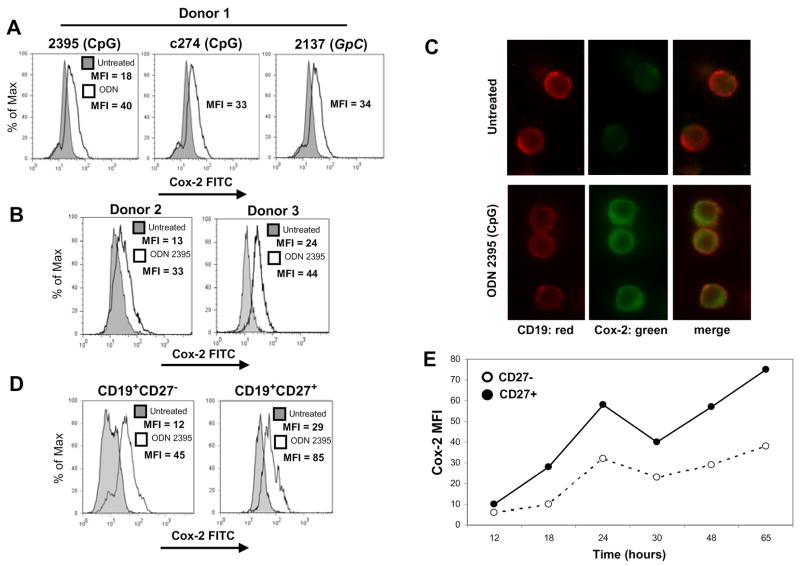

Synthetic CpG can act as an adjuvant, in part, by fueling B cell activation [1,14]. We hypothesized that as part of triggering an immune response, CpG ODN would not only activate human B cells, but would also induce Cox-2, a key immediate-early gene product important for B cell activation and antibody production [10,15]. We first determined whether or not CpG ODN could induce Cox-2 protein expression in human B cells. Several well-studied ODN sequences were tested for their ability to induce Cox-2. It was previously shown that different sequences vary in their capacity to induce proliferation and cytokine production in human B cells [1,16,17]. Purified B cells were cultured separately with two different CpG sequences, ODN 2395 and ODN c274, or with a non-CpG sequence, GpC ODN 2137. ODN 2137 was intended to be a negative control, as its sequence lacks cytosine-guanine repeats (contains GpC motifs). Cox-2 expression was measured at 48 hours by intracellular staining and flow cytometric analysis of CD19+ purified peripheral blood human B cells. Fig. 1A demonstrates that all three ODN sequences tested induced Cox-2 expression. The non-CpG sequence, GpC ODN 2137, also induced Cox-2, which was curious, as this sequence contains no cytosine-guanine repeats. Stimulation of CD19+ B lymphocytes from two other healthy donors with CpG ODN 2395 also induced Cox-2 (Fig. 1B), demonstrating that this was a favorable sequence for further investigation of Cox-2 induction.

Figure 1.

CpG ODN induces Cox-2 in human B lymphocytes. Human peripheral blood B cells were isolated and exposed to various ODN sequences for 48 hours. (A) B cells from donor 1 were incubated with CpG ODN 2395, CpG ODN c274, or GpC ODN 2137 (1 μg/mL). (B) Donor 2 and donor 3 B cells were stimulated only with CpG ODN 2395 (1 μg/mL). (C) Human B cells stimulated for 48 hours were stained for Cox-2 and CD19 and visualized by immunofluorescence. B cells were stained for surface CD19 (red) and for intracellular Cox-2 expression (green). Individual CD19 and Cox-2 stained cells are shown separately, as well as the merged image to illustrate coexpression. (D) B cells isolated from donor 4 were exposed to CpG ODN 2395 (1 μg/mL) and stained for surface expression of CD19 and CD27, as well as for intracellular Cox-2. Untreated B cells are represented as gray shaded histograms and ODN treatments are represented as open histograms. (E) Graphical representation of Cox-2 FITC mean fluorescence intensity values from B cells treated with CpG ODN 2395 (1 μg/mL).

Purification of B cells by positive selection utilizes magnetic beads conjugated to anti-human CD19 antibodies. Therefore, during isolation procedures, it is conceivable that B cells were stimulated through surface CD19. We evaluated whether or not positive selection influenced Cox-2 induction and compared CpG-induced Cox-2 expression in human B cells isolated by either positive or negative selection. Basal levels of Cox-2 expression in untreated B cells were indistinguishable no matter the selection procedures. In response to stimulation with ODN 2395, B cells isolated by positive selection increased Cox-2 by 302%, and those isolated by negative selection increased Cox-2 by 321% (data not shown). Since there were no significant differences in Cox-2 expression between B cells isolated by either technique, any brief CD19 stimulation during positive selection did not influence Cox-2 expression.

Induction of Cox-2 following ODN 2395 stimulation was further verified by immunofluorescence microscopy. Untreated B cells, stained for CD19 (red), expressed little to no Cox-2 (green), whereas cells stimulated with CpG ODN, expressed significant Cox-2 levels (Fig. 1C). The Cox-2 was located outside of the nucleus, most likely in the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope where it is found in other types of cells [18].

It was previously shown that naive B cells express very low levels of TLR9 in comparison to memory B cells, suggesting that B cell subsets may respond differently to CpG ODN [19]. Our flow cytometric analysis of CD27− naive and CD27+ memory B cells revealed that Cox-2 was induced in both subsets following exposure to CpG ODN (Fig. 1D & E).

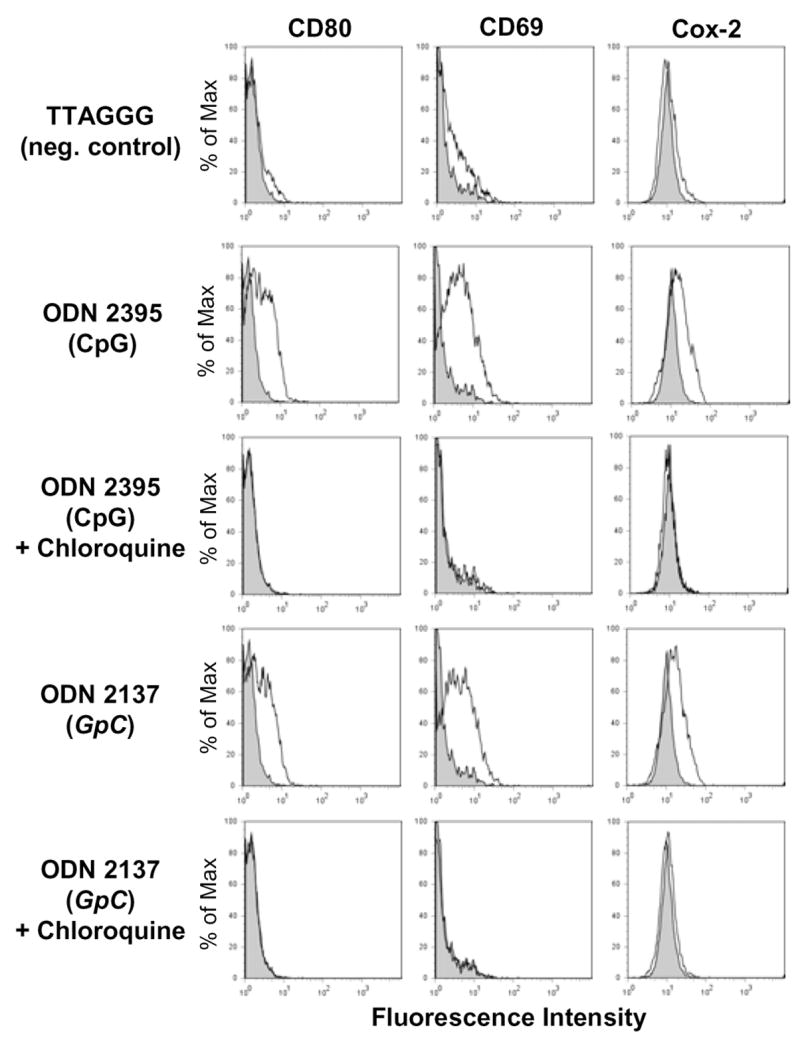

Chloroquine inhibits CpG ODN-induced Cox-2 expression

Our results demonstrated that CpG ODN and GpC ODN induced Cox-2 in B cells. To establish whether or not any ODN sequence influenced Cox-2 expression in human B cells, we tested the mammalian telomere ODN sequence TTAGGG. Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that this sequence did not activate B cells (see CD80, CD69 expression), nor did it affect Cox-2 protein levels (Fig. 2). To address whether CpG and GpC ODN acted via an endosomal/TLR9 mechanism, B cells were pre-treated with chloroquine, an inhibitor of endosomal acidification, which prevents the interaction of CpG ODN and TLR9 [20,21]. Chloroquine inhibited CpG-induced B cell activation as shown by lack of upregulation of CD80 and CD69 surface expression (Fig. 2). Intracellular Cox-2 expression was also inhibited by chloroquine treatment, supporting that both CpG and GpC ODN act via an acidified endosomal compartment.

Figure 2.

CpG and GpC ODN sequences induce Cox-2 in human B lymphocytes. B cells from a healthy donor were incubated with CpG ODN 2395, GpC ODN 2137 or TTAGGG, a negative control sequence (1 μg/mL). Cells were pretreated with Chloroquine (1μM) for 1 hour prior to addition of ODNs. Following a 48 hour culture, B cells were stained for surface expression of CD19, CD80, CD69 and intracellular Cox-2. Untreated B cells are represented as gray shaded histograms and ODN treatments are represented as open histograms.

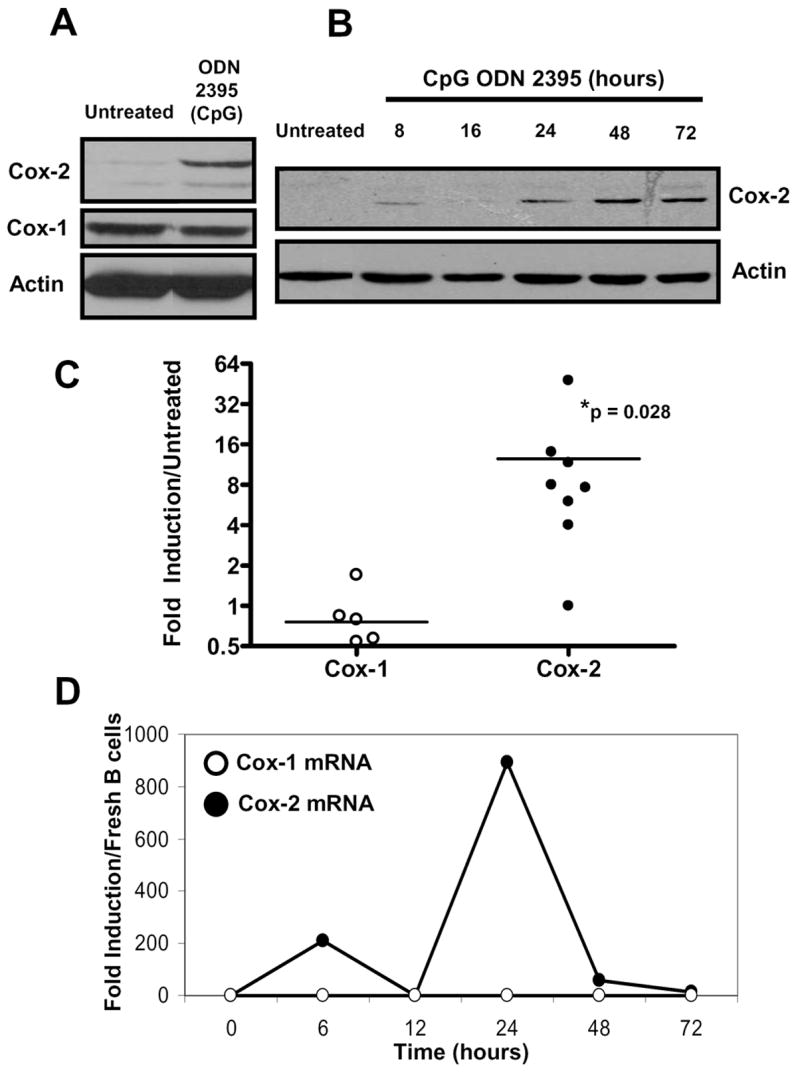

CpG ODN-induced Cox-2 protein expression correlates with steady-state mRNA levels

Further evaluation of the CpG containing ODN 2395 was performed to better characterize the effects on Cox-2 protein and mRNA expression. Fig. 3A demonstrates that ODN 2395 induced Cox-2 expression after 24 hours. Freshly isolated B cells typically fail to express Cox-2 ([10] and data not shown). Following stimulation with ODN 2395, Cox-1 protein levels were unchanged compared to untreated cells. Another western blot (Fig. 2B) shows Cox-2 expression over the course of a 72 hour culture from a representative donor. A slight induction of Cox-2 occurred at 8 hours post-CpG stimulation, which was typical of most donors. However, a much greater induction of Cox-2 was detected between 24 and 72 hours, which correlated well with flow cytometric data (Fig. 1) showing peak protein expression at 48 hours.

Figure 3.

CpG ODN induced Cox-2 protein and increased Cox-2 steady-state mRNA levels. Positively selected CD19+ human B lymphocytes were untreated or were stimulated with CpG ODN 2395 (1 μg/mL). (A) B cells were lysed after 24 hours and protein was evaluated by SDS-PAGE for Cox-2 protein levels. Lysates were also probed for Cox-1 and total actin. Cox-1 remained relatively unchanged after stimulation with CpG ODN 2395, whereas Cox-2 was induced. (B) Purified human B cells were untreated (48 hour time point) or were exposed to CpG ODN 2395 for 8, 16, 24, 48, and 72 hours. Lysates were probed for Cox-2 and total actin. (C) RNA was isolated from multiple human donor B cells and cultured with or without CpG ODN 2395 for 6 hours. cDNA was reverse transcribed and subjected to real-time PCR for Cox-1 (open circles), Cox-2 (closed circles), and the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Ct values were normalized to GAPDH and fold-induction calculated based on comparison of CpG-stimulated to untreated B cells. Statistical significance of CpG ODN treated to untreated B cells was determined by the Wilcoxon signed rank test (* p = 0.028). (D) A representative time-course of Cox-1 and Cox-2 mRNA expression levels. Fold-induction was calculated based on comparison of CpG-stimulated to freshly isolated B cells.

Due to the discovery that Cox-2 protein was induced in human B cells after stimulation with CpG ODN, we next wanted to determine if this effect occurred at the transcriptional level. Cox-1 and Cox-2 mRNA expression levels were assessed by real-time PCR through normalization to GAPDH and fold-induction calculated by comparison to untreated B cells. Compared to cells cultured in media alone, ODN 2395 significantly increased Cox-2 steady-state mRNA at six hours in multiple B cell donors (Fig. 3C). Conversely, Cox-1 mRNA levels were not significantly altered by CpG ODN exposure. Fig. 3D illustrates a common pattern of Cox-2 induction seen among human B cells treated with ODN 2395 over the course of 72 hours. Most donors showed a bi-modal course of Cox-2 mRNA steady-state level induction, while Cox-1 remained relatively unaffected. These data demonstrate that Cox-2 steady-state mRNA levels increased following CpG ODN treatment which is reflected through Cox-2 protein expression.

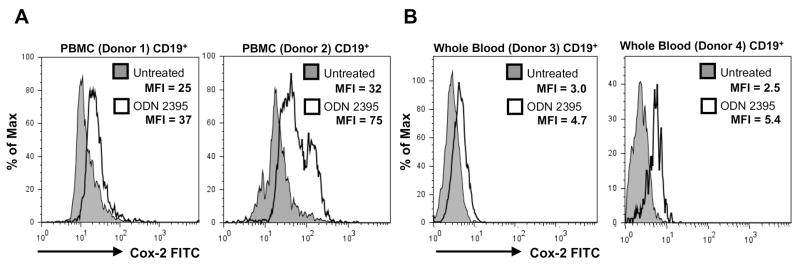

CpG ODN treated PBMC and whole blood B lymphocytes also induce Cox-2

We next wanted to study B cell Cox-2 expression in PBMC and whole blood cultures following stimulation with CpG ODN to reflect the complex cellular milieu in vivo. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from normal human donors and whole blood samples were cultured with or without ODN 2395 for 48 hours. Cells were stained for CD19, CD3, CD4, CD14, CD56 and intracellular Cox-2. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that Cox-2 was induced in CD19+ cells within PBMC populations from normal human donors upon stimulation with ODN 2395 (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, CD3+, CD4+, CD14+ and CD56+ cells failed to increase Cox-2 in response to ODN 2395 (data not shown). Cox-2 was also induced by ODN 2395 in CD19+ cells present within diluted whole blood cultures from both donors shown (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

CpG ODN induces Cox-2 in PBMCs and in whole blood CD19+ B lymphocytes. PBMCs were isolated from human peripheral blood using Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifugation. (A) Cells from donor 1 and 2 were stimulated with CpG ODN 2395 (10 μg/mL) for 48 hours. (B) Diluted whole blood from donor 3 and 4 was incubated with CpG ODN 2395 (10 or 20 μg/mL) for 48 hours. Cells from all donors were stained for surface CD19 and intracellular Cox-2. Histograms were gated on CD19+ events.

BCR signaling plus CpG ODN stimulation highly induce Cox-2 protein and PGE2 production in B cells

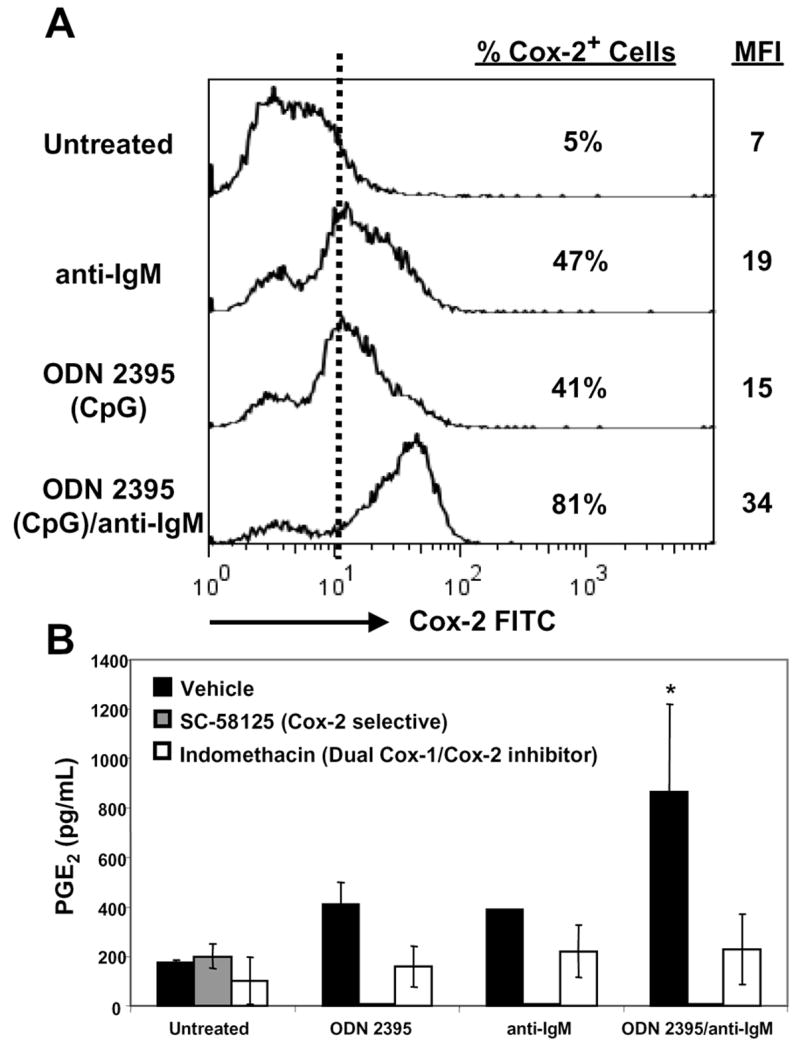

Human naive B cells require prolonged stimulation through the BCR and secondary signals through CD40L to become activated and proliferate [22]. Tertiary signals, such as CpG, can further promote survival and differentiation [23]. Vaccination promotes the expansion of naive antigen-specific B cells in part through BCR signaling. If adjuvants such as CpG ODN are used in vaccines, antigen-specific B cells could be stimulated through both the BCR and other receptors. Sites of microbial pathogen-induced inflammation could also provide similar signals to B cells. This concept encouraged us to determine whether triggering the BCR in concert with CpG ODN would lead to an even greater induction of Cox-2. Pilot data (not shown) revealed that Cox-2 mRNA steady-state levels were synergistically induced in B cells after stimulation with CpG ODN plus anti-IgM antibody, prompting us to investigate Cox-2 protein expression. Enhanced induction of Cox-2 protein was observed after BCR stimulation and exposure to CpG ODN. Using stained untreated B cells as a reference for Cox-2 expression, 47% of B cells expressed Cox-2 after treatment with anti-IgM and 41% expressed Cox-2 after CpG (Fig. 5A). Strikingly, when B cells were cultured with CpG ODN 2395 plus anti-IgM, 81% of B cells were positive for Cox-2. Furthermore, they also expressed higher levels of Cox-2 (see the MFI). Multiple healthy donors followed a similar Cox-2 induction profile upon stimulation with both anti-IgM plus CpG ODN. These data demonstrate that BCR stimulation plus CpG ODN, further increases Cox-2 expression in normal human B lymphocytes.

Figure 5.

B cell activation with anti-IgM plus CpG ODN highly induces Cox-2 and PGE2 synthesis. (A) Human B cells were cultured in media alone, ODN 2395 (1 μg/mL), anti-IgM (10 μg/mL) or ODN 2395 plus anti-IgM for 48 hours. Cells were stained for surface CD19 and intracellular Cox-2. Cells were gated on CD19+ events. Flow cytometric data are representative of one donor, however multiple donors screened showed a similar Cox-2 induction pattern at 48 hours. (B) Supernatants collected from B cells cultured for 36 hours were analyzed for PGE2. Cells were also incubated in the presence of ethanol (vehicle, black), a Cox-2 selective inhibitor (SC-58125, gray), or a dual Cox-1/Cox-2 inhibitor (indomethacin, white). Supernatants were analyzed by EIA. Statistical significance determined by Student’s t test (*p < 0.05).

Synthesis of prostanoids reveals that Coxs are enzymatically active. To determine if Cox-2 expressed by CpG-activated human B cells was functionally active, PGE2 was measured by enzyme immunoassay (Fig. 5B). B cells were cultured in media alone, with ODN 2395, anti-IgM, or ODN 2395 plus anti-IgM for 36 hours. CpG ODN 2395 and anti-IgM separately induced similar amounts of PGE2, approximately 2-fold over untreated. A significant 4-fold increase in PGE2 levels was observed when ODN 2395 plus anti-IgM were added to B cells. The dual Cox-1/Cox-2 inhibitor, indomethacin, or a Cox-2 selective inhibitor, SC-58125 (a close Celebrex analogue), were also added to cultures to determine if PGE2 production was Cox-2 dependent. PGE2 production was largely abrogated in the presence of either drug, demonstrating that the increased PGE2 production seen after ODN 2395 treatment was Cox-2 dependent.

Antibody production in response to CpG ODN is partially dependent on Cox-2

Optimal antibody production against specific pathogen-associated antigens is often a desired outcome of vaccination. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides are being tested as adjuvants due to their ability to augment antibody production [2,4,5]. Our laboratory previously demonstrated that small molecule Cox inhibitors attenuated both IgM and IgG antibody production in human B cells activated through CD40 and BCR stimulation [10]. It was important to determine whether attenuating Cox-2 activity would also decrease B lymphocyte antibody production induced by CpG ODN.

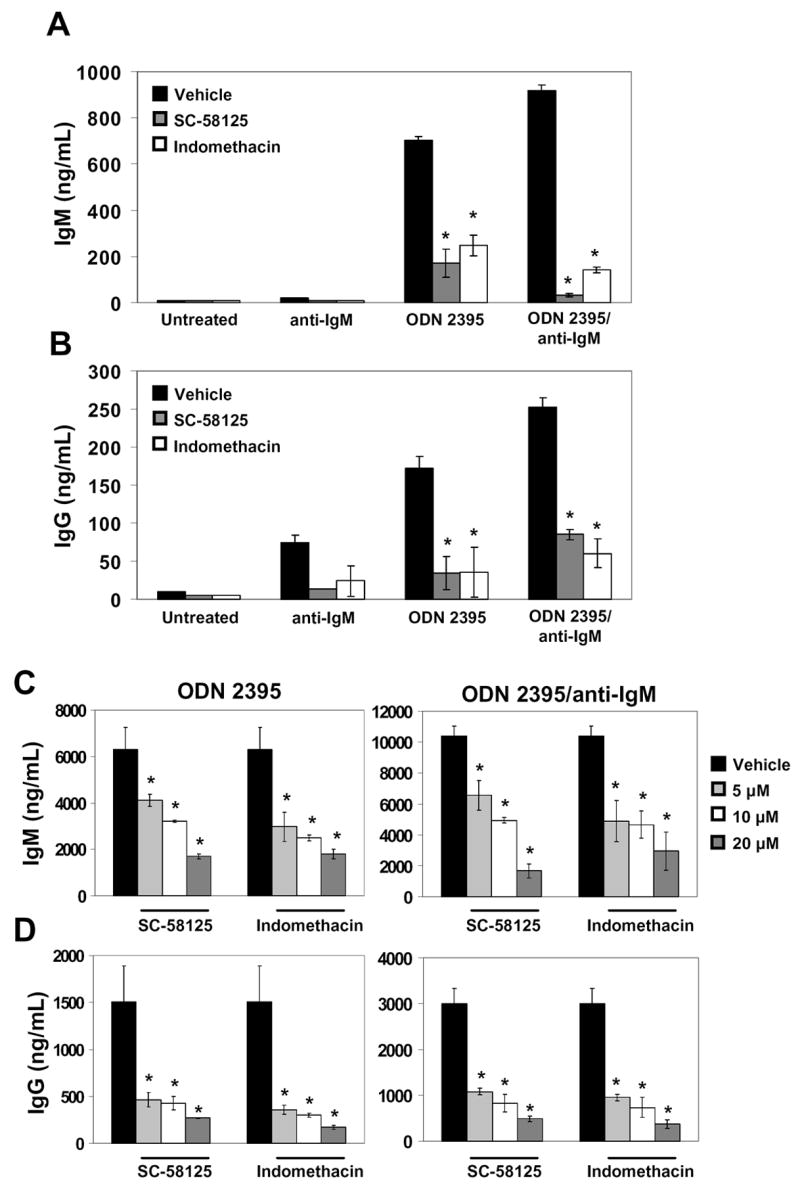

B cells were purified and cultured for 7 days in the presence of ODN 2395 and/or anti-IgM. Treatment with ODN 2395 plus anti-IgM significantly increased IgM and IgG levels above those seen when B cells were exposed to ODN 2395 or anti-IgM alone (Fig. 6A & B). Unstimulated B cells produced little to no IgM or IgG (Fig. 6A & B). Indomethacin, a non-selective Cox-1 and Cox-2 inhibitor, or SC-58125, a Cox-2 selective inhibitor, was added to the cultures to determine the effects of Cox inhibitors on CpG ODN-induced antibody production. Treatment of human B cells with dilutions of indomethacin or SC-58125 significantly reduced IgM and IgG levels (Fig. 6A–D). Following 7 days of exposure, CpG ODN treated cells produced 35%, 48%, and 73% less IgM with escalating doses of the Cox-2 selective inhibitor, SC-58125 (Fig. 6C). Addition of 5, 10, and 20 μM SC-58125 to B cells stimulated with both CpG ODN 2395 plus anti-IgM attenuated IgM production by 37%, 52%, and 84%, respectively. Production of IgG was influenced to a greater extent by SC-58125 exposure at the 5 μM low dose, where IgM and IgG levels were reduced by 69% and 64%, respectively (Fig. 6C & D). Similar reductions of IgM and IgG levels were observed following treatment with indomethacin. These findings reveal that small molecule Cox inhibitors blunt CpG ODN-induced IgM and IgG production.

Figure 6.

Cox-2 inhibitors attenuate CpG-induced IgM and IgG production. Human B cells were stimulated with ODN 2395 (1 μg/mL), anti-IgM (2 μg/mL), or ODN 2395 plus anti-IgM. Cells were also cultured in the presence of a Cox-2 selective inhibitor, SC-58125, or with the dual Cox-1/Cox-2 inhibitor, indomethacin. Supernatant levels of IgM (A) and IgG (B) from B cells cultured for 6 days in the presence of 20 μM indomethacin or SC-58125 were assessed by ELISA. IgM (C) and IgG (D) levels on day 7 were analyzed by ELISA from B cells cultured with indomethacin or SC-58125 (5, 10 or 20 μM). Statistical significance determined by Student’s t test (*p < 0.05).

Discussion

CpG ODN is postulated to act as an adjuvant by its capacity to elicit an innate immune response and also by its ability to directly influence cells of adaptive immunity [24]. Our new data demonstrate that CpG ODNs stimulate human B lymphocytes to express Cox-2. Subsequently, CpG-induced Cox-2 activity was shown to be responsible for optimal IgM and IgG production in vitro. We propose that the adjuvant activity of CpG ODN on human B cells is at least partially due to Cox-2 induction. One clinical study utilizing CpG ODN as adjuvants showed enhanced antibody response to Engerix B, the hepatitis B virus vaccine [24,25]. Recipients who were administered CpG ODN adjuvant with the vaccine had higher antibody titers and produced antibody more rapidly than those who received vaccine alone [25]. Herein, our data support a potentially significant role for Cox-2 in the ability of CpG to enhance immune responses during vaccination.

Several ODN sequences were tested for their ability to induce Cox-2 in normal human B cells in vitro. CpG ODN 2395 was a potent inducer of Cox-2 in both naive and memory B cell subsets. However, the non-CpG sequence, GpC ODN 2317 (contains guanine-cytosine motifs), was also capable of inducing Cox-2. This raised the question as to whether or not any random phosphorothioate modified sequence could induce Cox-2 in B cells, as the GpC ODN 2137 sequence was originally intended to be a negative control. Our study shows that Cox-2 was not induced when human B cells were stimulated with the mammalian telomere sequence TTAGGG ODN, which contains neither CpG nor GpC motifs. This demonstrated that random phosphorothioate modified sequences do not induce Cox-2 in normal human B cells.

It is generally believed that CpG DNA sequences stimulate cells through TLR9 found in the endosomal compartment [26]. Our data demonstrated that chloroquine, which increases the pH of endosomes, potently blocked the ability of CpG ODNs to induce the surface markers CD80, CD69 and Cox-2. This is consistent with CpG ODNs trafficking to endosomes and interacting with a TLR. Interestingly, GpC ODN 2137, a non-CpG sequence, which were previously thought by some not to interact with TLR9 [27,28] also potently induced human B cell expression of CD80, CD69 and Cox-2. This GpC ODN-induced activation was also potently inhibited by chloroquine. Recent studies reveal that phosphorothioate modified non-CpG ODN, which contain GpC motifs, trigger responses similar to CpG sequences and these responses are abrogated in TLR9 knockout mice [29,30]. In aggregate, our new findings coupled with these other studies, suggest that in humans, phosphorothioate modified GpC sequences could act through a TLR, however, further investigation will be necessary to confirm that this is a TLR-dependent mechanism. Of significant interest is that both CpG and GpC ODNs induce Cox-2 in human B cells and this suggests that non-CpG ODN may also prove useful as adjuvants for human B cells.

Analysis of Cox-2 mRNA and protein induction profiles demonstrated that CpG ODN induced a bi-modal expression pattern. Typically, Cox-2 protein was detected at 18 hours after CpG exposure. However, some donors showed slight induction of Cox-2 earlier than 12 hours (Fig. 3B), which correlated with early elevated Cox-2 mRNA levels. Although this early expression of Cox-2 may be important for an immediate-early response, our data showed strong Cox-2 protein expression at 24 and 48 hours. It is possible that each peak of the bi-modal expression pattern of Cox-2 was induced by different factors. CpG could be directly responsible for either or both inductions of Cox-2, or secondary effectors, elicited initially by CpG, could be responsible for the latter induction of Cox-2. Regardless, our data clearly shows that CpG induce Cox-2 in human B cells and that Cox-2 activity is necessary for the optimal production of antibody.

CpG ODN have the potential to strengthen the humoral immune response to vaccination. Administering vaccines with CpG ODN as an adjuvant would stimulate B cells through both the BCR and through CpG-ODN mediated pathways. As our results demonstrate, the strong dual signal from BCR stimulation and via CpG ODN increased the magnitude of Cox-2 expression in B cells above that seen with either ligand alone. Enhanced PGE2, IgM and IgG production resulting from dual receptor triggering was a result of Cox-2 induction, as shown by attenuation of production in response to Cox-2 selective inhibitors. Therefore, a strong dual signal received through CpG ODN and the BCR would further activate B cells, leading to elevated Cox-2 expression, and ultimately enhanced antibody production.

CpG ODN exposure was previously shown to induce Cox-2 in mouse splenocytes and in mouse macrophage-like cell lines [31,32]. Mice injected with CpG ODN showed increased plasma PGE2 levels, indicating that Cox-2 can be induced in vivo [33]. However, cell-type specific Cox-2 induction and whether or not CpG ODN influences human Cox expression has not been investigated. Our analysis of whole blood and PBMCs following CpG ODN stimulation for 48 hours demonstrated that only CD19+ B lymphocytes showed enhanced Cox-2 expression (Fig. 4 and data not shown). These data differ from findings in mice and illustrate the importance of studying Cox-2 expression in human B cells.

Our new findings show that a variety of ODN sequences induced Cox-2 in B lymphocytes, albeit to varying degrees. This not only reveals the range of responses between human subjects, but also that humans vary in their ability to be stimulated by different ODN sequences. This finding suggests that vaccine adjuvants such as various CpG ODN sequences may have to be individually tailored based upon sequences most stimulatory to a particular recipient. The magnitude of CpG-stimulated B cell Cox-2 induction could correlate with the adjuvant strength of each particular sequence. Future investigation will be needed to determine whether the adjuvant activity of CpG is related to the degree of B cell Cox-2 induction in humans.

Safety of adjuvants is of major concern for human vaccination and therapies. There has been increased interest in using adjuvants that act via CD40 in clinical trials [34]. Recently, investigators have demonstrated that supplying anti-CD40 antibody as an adjuvant depletes the memory T cell compartment [7]. By impairing long-term immune responses, this strategy counteracts the purpose of vaccination, which aims to enhance primary, as well as subsequent immune responses. This finding strengthens the importance of using other adjuvants, like CpG ODN, and understanding the effects that they may have on the human immune system. Our studies further the current knowledge of ODN and the role that they play in influencing human B cell biology.

The data presented herein illustrates that Cox-2 is necessary for optimal IgM and IgG production from B cells activated with CpG. This concept is supported by the fact that a Cox-1/Cox-2 dual enzymatic inhibitor or a Cox-2-selective inhibitor attenuated CpG-induced IgM and IgG production. Overall, Cox-2 expression is essential for CpG ODN stimulated B lymphocytes to optimally produce antibody. Administration of Cox inhibitors, such as the Cox-2 selective drug Celebrex or common NSAIDs that influence Cox-2, must be taken into consideration if CpG ODNs are to be used as vaccine adjuvants. Not only do these drugs have the potential to dampen antibody responses during vaccination, but may also attenuate the heightened antibody responses induced by adjuvants such as CpG ODN.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants DE011390, AI071064, the Training Program in Oral Infectious Diseases Grant T32-DE07165 and the Training Program in Oral Science T32-DE007202. The authors would like to thank Dr. Ignacio Sanz for providing reagents for isolation of B cells by negative selection and Dr. Neil Blumberg for advice pertaining to statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

- ODN

oligodeoxynucleotide

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- EIA

enzyme immunoassay

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Marshall JD, Fearon K, Abbate C, Subramanian S, Yee P, Gregorio J, Coffman RL, Van Nest G. Identification of a novel CpG DNA class and motif that optimally stimulate B cell and plasmacytoid dendritic cell functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:781–92. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1202630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang H, Nishioka Y, Reich CF, Pisetsky DS, Lipsky PE. Activation of human B cells by phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1119–29. doi: 10.1172/JCI118894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourke E, Bosisio D, Golay J, Polentarutti N, Mantovani A. The toll-like receptor repertoire of human B lymphocytes: inducible and selective expression of TLR9 and TLR10 in normal and transformed cells. Blood. 2003;102:956–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovarik J, Bozzotti P, Tougne C, Davis HL, Lambert PH, Krieg AM, Siegrist CA. Adjuvant effects of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides on responses against T-independent type 2 antigens. Immunology. 2001;102:67–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu N, Ohnishi N, Ni L, Akira S, Bacon KB. CpG directly induces T-bet expression and inhibits IgG1 and IgE switching in B cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:687–93. doi: 10.1038/ni941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He B, Qiao X, Cerutti A. CpG DNA induces IgG class switch DNA recombination by activating human B cells through an innate pathway that requires TLR9 and cooperates with IL-10. J Immunol. 2004;173:4479–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berner V, Liu H, Zhou Q, Alderson KL, Sun K, Weiss JM, Back TC, Longo DL, Blazar BR, Wiltrout RH, Welniak LA, Redelman D, Murphy WJ. IFN-gamma mediates CD4+ T-cell loss and impairs secondary antitumor responses after successful initial immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2007;13:354–60. doi: 10.1038/nm1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chun KS, Surh YJ. Signal transduction pathways regulating cyclooxygenase-2 expression: potential molecular targets for chemoprevention. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1089–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graf BA, Nazarenko DA, Borrello MA, Roberts LJ, Morrow JD, Palis J, Phipps RP. Biphenotypic B/macrophage cells express COX-1 and up-regulate COX-2 expression and prostaglandin E(2) production in response to pro-inflammatory signals. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3793–803. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199911)29:11<3793::AID-IMMU3793>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan EP, Pollock SJ, Murant TI, Bernstein SH, Felgar RE, Phipps RP. Activated human B lymphocytes express cyclooxygenase-2 and cyclooxygenase inhibitors attenuate antibody production. J Immunol. 2005;174:2619–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mongini PK, Inman JK, Han H, Fattah RJ, Abramson SB, Attur M. APRIL and BAFF promote increased viability of replicating human B2 cells via mechanism involving cyclooxygenase 2. J Immunol. 2006;176:6736–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris SG, Padilla J, Koumas L, Ray D, Phipps RP. Prostaglandins as modulators of immunity. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:144–50. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishihara Y, Zhang JB, Quinn SM, Schenkein HA, Best AM, Barbour SE, Tew JG. Regulation of immunoglobulin G2 production by prostaglandin E(2) and platelet-activating factor. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1563–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1563-1568.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klinman DM, Currie D, Gursel I, Verthelyi D. Use of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as immune adjuvants. Immunol Rev. 2004;199:201–16. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryan EP, Malboeuf CM, Bernard M, Rose RC, Phipps RP. Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibition Attenuates Antibody Responses against Human Papillomavirus-Like Particles. J Immunol. 2006;177:7811–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vollmer J, Weeratna R, Payette P, Jurk M, Schetter C, Laucht M, Wader T, Tluk S, Liu M, Davis HL, Krieg AM. Characterization of three CpG oligodeoxynucleotide classes with distinct immunostimulatory activities. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:251–62. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jurk M, Schulte B, Kritzler A, Noll B, Uhlmann E, Wader T, Schetter C, Krieg AM, Vollmer J. C-Class CpG ODN: sequence requirements and characterization of immunostimulatory activities on mRNA level. Immunobiology. 2004;209:141–54. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandrasekharan NV, Simmons DL. The cyclooxygenases. Genome Biol. 2004;5:241. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-9-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernasconi NL, Onai N, Lanzavecchia A. A role for Toll-like receptors in acquired immunity: up-regulation of TLR9 by BCR triggering in naive B cells and constitutive expression in memory B cells. Blood. 2003;101:4500–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutz M, Metzger J, Gellert T, Luppa P, Lipford GB, Wagner H, Bauer S. Toll-like receptor 9 binds single-stranded CpG-DNA in a sequence- and pH-dependent manner. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2541–50. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macfarlane DE, Manzel L. Antagonism of immunostimulatory CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides by quinacrine, chloroquine, and structurally related compounds. J Immunol. 1998;160:1122–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galibert L, Burdin N, Barthelemy C, Meffre G, Durand I, Garcia E, Garrone P, Rousset F, Banchereau J, Liu YJ. Negative selection of human germinal center B cells by prolonged BCR cross-linking. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2075–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruprecht CR, Lanzavecchia A. Toll-like receptor stimulation as a third signal required for activation of human naive B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:810–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klinman DM. Immunotherapeutic uses of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:249–58. doi: 10.1038/nri1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halperin SA, Van Nest G, Smith B, Abtahi S, Whiley H, Eiden JJ. A phase I study of the safety and immunogenicity of recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen co-administered with an immunostimulatory phosphorothioate oligonucleotide adjuvant. Vaccine. 2003;21:2461–7. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Kaisho T, Sato S, Sanjo H, Matsumoto M, Hoshino K, Wagner H, Takeda K, Akira S. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–5. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chuang TH, Lee J, Kline L, Mathison JC, Ulevitch RJ. Toll-like receptor 9 mediates CpG-DNA signaling. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:538–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeshita F, Leifer CA, Gursel I, Ishii KJ, Takeshita S, Gursel M, Klinman DM. Cutting edge: Role of Toll-like receptor 9 in CpG DNA-induced activation of human cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:3555–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts TL, Sweet MJ, Hume DA, Stacey KJ. Cutting edge: species-specific TLR9-mediated recognition of CpG and non-CpG phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotides. J Immunol. 2005;174:605–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vollmer J, Weeratna RD, Jurk M, Samulowitz U, McCluskie MJ, Payette P, Davis HL, Schetter C, Krieg AM. Oligodeoxynucleotides lacking CpG dinucleotides mediate Toll-like receptor 9 dependent T helper type 2 biased immune stimulation. Immunology. 2004;113:212–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Zhang J, Moore SA, Ballas ZK, Portanova JP, Krieg AM, Berg DJ. CpG DNA induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin production. Int Immunol. 2001;13:1013–20. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.8.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh DK, Misukonis MA, Reich C, Pisetsky DS, Weinberg JB. Host response to infection: the role of CpG DNA in induction of cyclooxygenase 2 and nitric oxide synthase 2 in murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7703–10. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7703-7710.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozak W, Wrotek S, Kozak A. Pyrogenicity of CpG-DNA in mice: role of interleukin-6, cyclooxygenases, and nuclear factor-kappaB. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R871–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00408.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melero I, Hervas-Stubbs S, Glennie M, Pardoll DM, Chen L. Immunostimulatory monoclonal antibodies for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:95–106. doi: 10.1038/nrc2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]