Abstract

This article was a preliminary report of prospective clinical trial of a group of patients with chronic discogenic low back pain who met the criteria for lumbar interbody fusion surgery but were treated instead with an intradiscal injection of methylene blue (MB) for the pain relief. Twenty-four patients with chronic discogenic low back pain underwent diagnostic discography with intradiscal injection of MB. The principal criteria to judge the effectiveness included alleviation of pain, assessed by visual analog scale (VAS), and improvement in disability, as assessed with the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) for functional recovery. The mean follow-up period was 18.2 months (range 12–23 months). Of the 24 patients, 21 (87%) reported a disappearance or marked alleviation of low back pain, and experienced a definite improvement in physical function. A statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in the changes in the ODI and the VAS scores were obtained in the patients with chronic discogenic low back pain (P=0.0001) after the treatment. The study suggests that the injection of MB into the painful disc may be a very effective alternative for the surgical treatment of chronic discogenic low back pain.

Keywords: Discogenic low back pain, Discography, Methylene blue, Injection

Introduction

Low back pain is one of the most common causes of disability. It is estimated that 80% of the population will experience back pain to a significant extent at some time during their lives [1]. The pain is generally thought to be the result of nerve root compression, but several clinical studies have showed that merely less than 30% of low back pain can be ascribed to nerve root compression [11]. Mooney [17] has placed this figure as low as 1%. Recent studies have found that the discogenic pain which is caused by annular disruption is the most common cause of chronic low back pain [11].

The treatment of discogenic low back pain is one of the most challenging clinical problems to the spinal surgeon. Undoubtedly, nonoperative treatment, including bed rest, exercise, traction, drug therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, manipulation, etc. may be effective for some patients. However, a substantial number of patients experience no improvement with these therapeutic attempts [25]. For these patients, surgical management may be necessary because of their poor response and functional limitations. A novel, valid, and minimally invasive method of management for discogenic low back pain is therefore desirable.

The pathogenesis of discogenic low back pain is extremely complicated and poorly understood. Our previous study discovered that the distinct pathological characteristic of the painful discs was the formation of a zone of vascularized granulation tissue with extensive innervation extending from the outer layer of the annulus fibrosus into the nucleus pulposus along a torn fissure as shown on CT discography [21]. Our findings suggested that the zone of granulation tissue may be the culprit responsible for causing the discogenic low back pain. With this assumption in mind, it is presumed that if the nerve fibers and nerve endings growing into the disc along the tear could be devitalized, discogenic pain would be alleviated or abated.

Ever since methylene blue (MB) was first synthesized in 1876, it has been used in many different areas of clinical medicine [31]. Its neurotropic effect enables it to block nerve conduction or destroy nerve endings; therefore, the local injection of it has been used for the treatment of various painful ailments and idiopathic pruritus ani [3, 5, 15, 24]. Having recognizance of its neurotropic action, we attempt to use intradiscal MB injection for the treatment of discogenic low back pain. This article is a summary of prospective clinical trial of a group of patients with discogenic low back pain, who met the criteria for interbody fusion surgery, but were treated instead with an intradiscal MB injection.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

From September, 2003 to October, 2004, we selected 52 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain and no radiculopathy who were preliminarily diagnosed as discogenic low back pain. Depending upon their histories, clinical examinations, and imaging, lumbar disc herniation, lumbar canal stenosis, neurologic disease, tumor, or infection were excluded. All patients poorly responded to various conservative therapies of more than 6 months including physical therapy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In addition, these patients had no previous lumbar surgery, and showed a normal or slightly decreased height of the disc space on lateral plain X-ray film. Therefore, these patients were considered eligible as candidates for lumbar interbody fusion. Before patients underwent routine discography, the alternative treatment modalities were discussed with them, inquiring them whether or not they would consent for intradiscal injection of MB instead of lumbar interbody fusion should there be positive provocation of pain during discography. Of the 52 patients, 47 accepted for intradiscal MB injection, and five preferred to lumbar fusion surgery if the diagnosis of discogenic low back pain should be confirmed.

Lumbar discography

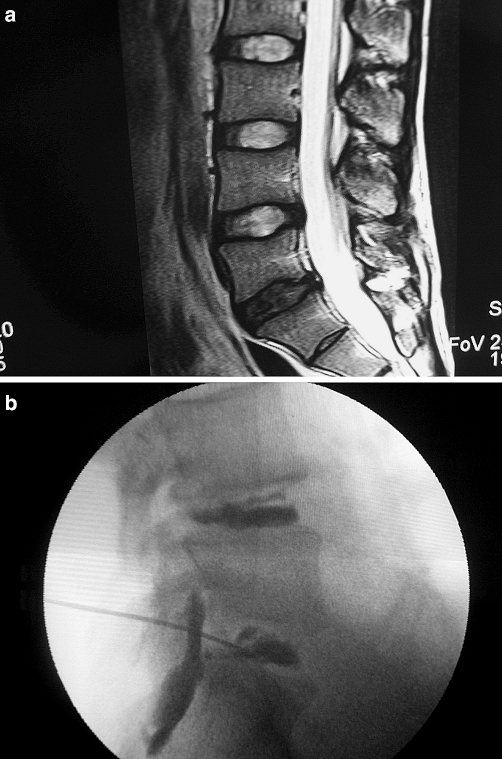

All discography was performed under guidance of fluoroscopy, using a standard posterolateral approach and a double-needle technique [11]. The original plan was to conduct the discography on each patient for the discs L3–L4, L4–L5, and L5–S1. In practice, it was not necessary to take images of all these discs. In some patients, L2–L3 disc was punctured when the discography was negative for the three lower ones. At least two discs were studied in each patient. The discographic needles were inserted on the contralateral side of painful area. Once the needle was accurately inserted into the center of the disc, nonionic contrast medium Isovist was instilled slowly into the nucleus (Fig. 1). A positive discography was defined if the patient experienced exact reproduction of his or her usual pain response pattern, and the posterior annular disruption was shown to extend into the outer annulus or beyond the confines of the outer annulus by the contrast medium. The diagnosis should be further affirmed by fulfilling the following criteria for discogenic low back pain: (1) pain was reproduced on provocative discography and (2) revelation of a posterior tear or fissure reaching the outer layer of the annulus fibrosus on discogram [30].

Fig. 1.

A 36-year-old man with a 3-year history of severe low back pain. a Sagittal T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan showed L5/S1 disc degeneration, with no disc herniation. b Discography showed L5/S1 disc disruption with concordant pain reproduction. Note the contrast media leaking out of posterior annulus through a tear. After discography, 10 mg MB was injected into disc through discographic needle. Three days after injection, low back pain was totally relieved. No recrudescence was observed at a 23-month follow-up interval after treatment

Intradiscal MB injection

Out of 47 patients with chronic low back pain, 24 were proved to be suffering from discogenic pain, and consented for intradiscal MB injection treatment. Through the discographic needle 1 ml of 1% MB (10 mg, Sujichuan Pharmaceutical Ltd, Jiangsu, China) was injected into the diseased disc proved by discogram, and followed by 1 ml of 2% Lidocaine hydrochloride was used for relieving pain postoperatively. After treatment, the patients were confined to bed for 24 h, and asked to avoid strenuous exercise for 3 weeks.

Among 24 patients who accepted intradiscal MB injection, there were 15 men and 9 women, with a mean age of 43.4 years (22–67). The mean duration of low back pain was 64 months (6–144). Eighteen of them were suffering of discogenic pain at a single level (L3/4: 2, L4/5: 6, L5/S1: 10), and 6 at two levels (L4/5 and L5/S1).

Outcome measures

An 11-point (0–10) visual analog scale (VAS) was used to measure the intensity of low back pain. The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI, 0–100) was used to evaluate the functional disability according to the Oswestry Low Back Pain Questionnaire [4], which describes back-related disability as a combination of physical and social restriction through ten questions covering different dimensions of daily living. A sum is calculated and presented as a percentage, where 0% represents no disability and 100% the worst possible disability. Scores of pre-treatment and post-treatment were tabulated and compared. A t test was used to determine whether the average difference between scores before and after treatment was statistically significant.

Results

The mean follow-up period for the patients who accepted intradiscal MB injection was 18.2 months (12–23 months, minimum follow-up was 12 months). On the basis of a minimum two-point change between pre- and post-treatment VAS scores [28], among the 24 patients, one obtained modest improvement but pain relapsed three months after the treatment, two showed no evident improvement (a reduction in VAS of less than 2 points). Among the rest (21, 87%), five patients declared complete relief, six dramatic improvement (VAS less than 2 points), and ten clinical important improvement (a reduction in VAS of at least 2 points compared with pre-treatment). Their median VAS was reduced from 7.52 to 2.18, with a mean reduction of 5.34 (P=0.000). On the ODI, in 21 (87%) of 24 patients there was significant improvement in function. A median improvement of 68% in disability was obtained (P=0.000). When the VAS and the ODI at 3 months were compared with those at 12 months (or more), no significant difference was found (VAS: P=0.642, t=−0.563; ODI: P=0.626, t=−0.481). The results indicated that the effectiveness of intradiscal MB injection for the treatment of discogenic low back pain was long lasting (Table 1).

Table 1.

VAS and the ODI in patients who underwent intradiscal MB injection (n=24, mean±SD)

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment (3 months) | Post-treatment (6 months) | Post-treatment (≥12 months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS (0–10) | 7.52±1.31 | 2.50±2.09* | 2.37±2.06* | 2.18±1.79* |

| ODI (0–100) | 48.71±5.28 | 17.42±14.76# | 16.79±15.02# | 15.38±13.63# |

VAS visual analog scale, ODI Oswestry Disability Index

P*<0.001

P#<0.001

The treatment efficacy of patients with a single level discogenic pain was compared with that of two levels. According to a minimum two-point change between pre- and post-treatment VAS scores, of the 24 patients treated with intradiscal MB injection, a successful result was achieved in 17 (94%) of 18 patients treated at a single level and four (67%) of six patients treated at two levels. The VAS scores in patients injected at a single level were improved by a mean reduction of 5.65 (t=12.511, P=0.000), and in patients injected at two levels by a mean reduction of 4.40 (t=4.439, P=0.007). The ODI changes in patients injected at single level was improved by a mean reduction of 35.72 (t=12.265, P=0.000), and in patients injected at two levels it was improved by a mean reduction of 24.50 (t=3.246, P=0.029) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparisons of efficacy between pain at single level and two levels (mean±SD)

| VAS | ODI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | |

| Single level (n=18) | 7.83±1.06 | 2.18±1.58* | 49.83±5.02 | 13.56±12.55* |

| Two level (n=6) | 6.58±1.65 | 2.18±2.53# | 45.33±4.93 | 20.83±16.47# |

VAS visual analog scale, ODI Oswestry Disability Index

P*<0.001

P#<0.05

In all 24 patients treated with intradiscal MB injection, no patients complained of symptoms of nerve root injury or back pain aggravation after the treatment. No side effects or complications occurred in these patients.

Discussion

The diagnosis and treatment of chronic low back pain is a very difficult clinical problem. Intractable low back pain that has lasted for 6 months and unresponsive to nonoperative interventions has a low probability of spontaneous resolution [28]. The current study reported the clinical outcome in a group of patients with chronic discogenic low back pain proved by discography who showed no response to various nonoperative treatments and met the criteria for interbody fusion surgery, were treated instead with an intradiscal MB injection. The preliminary results indicated that the result of intradiscal MB injection for the treatment of discogenic low back pain was relatively encouraging.

In recent decades, surgical fusion of the lumbar spine has been increasingly applied for chronic low back pain. However, the reported results vary considerably in different studies, and the complication rate after fusion surgery in the lumbar spine is not negligible [7–9, 14, 18, 22]. As an alternative treatment, intradiscal electrothermal annuloplasty (IDET) has recently been advocated [13, 19, 26–28]. This procedure involves the introduction of a flexible electrode into the disc to encircle the nucleus pulposus around the lateral and posterior annulus. Electric current is passed through the electrode to produce heat to coagulate collagen and nociceptive nerve fibers. However, the mechanism of relieving pain has been denied by a recent experimental study [6], though a successful outcome of IDET has been reported in 40–80% of patients [13, 19, 26–28].

The treatment results achieved in the current study were similar or superior to those obtained by fusion surgery or IDET [7–10, 14, 22], as shown by the difference between pre- and post-treatment VAS scores [7–10, 13, 14, 19, 22, 26–28]. In addition, based on the ODI, marked improvement was observed in 87% of the patients. Although the follow-up time in the current study was short, there was no difference in the VAS and the ODI scores between 3 months and those of 12 months (or more) after the treatment for all the patients. This observation suggests that the therapeutic efficacy of intradiscal MB injection is stable and credible.

The pathology responsible for chronic discogenic low back pain is within the disc property itself. The only feature of these painful discs that is distinctive from other asymptomatic degenerated discs is the positive pain response during discography [2, 10, 12, 16, 23, 29]. Mooney [17] maintained that the disc should be the primary structure responsible in producing low back pain. Our previous study found [21] that the pathologic features of discs obtained from the patients with discogenic low back pain were the formation of a zone of vascularized granulation tissue with extensive innervation in fissures extending from the outer part of the annulus into the nucleus pulposus. The study clearly demonstrated that in the zone of vascularized granulation tissue there were abundant SP-immunoreactive nerve fibers which had been thought to be nociceptive. Most likely the nociceptors within the granulation tissue could be excited by local inflammation to produce a painful response. Thus, the sharp painful sensation elicited during injection of contrast medium should be attributed to the innervation into the fissures within the disc structure. The sharp increase of intradiscal pressure following the injection of the contrast medium doubtlessly produces an abrupt irritation of the nociceptive nerve elements, hence excruciating pain, as evidenced by immediate subsidence of pain when pressure declines as the contrast medium leaks out of the disc from the tears [21].

According to the results of our previous study [21], theoretically, if a drug or chemical compound could destroy the nerve endings or nociceptors ingrown into the painful disc along the tear, the rational treatment of discogenic low back pain should be aimed at disrupting the pathway of nerve conduction. Intradermal MB injection has been shown by electron microscopy to be able to destroy dermal nerve endings [3, 5]. It led us to think that it is reasonable to use intradiscal MB injection for alleviating discogenic low back pain. A successful outcome has finally been achieved in relieving pain and improving disability. This result may indicate that MB indeed has devitalized the nerve endings or nociceptors in the painful discs. Theoretically, devitalized nerve fibers or nerve endings are able to regenerate under certain conditions, and consequently leading to the recurrence of symptoms. Practically, our observation revealed that the pain relief of intradiscal MB injection is long lasting. The underlying mechanisms of a prolonged effect may include that MB destroys nerve endings or nociceptors within discs, sustains action ascribed to the absence of blood vessels in the disc, and alleviates inflammatory response by inhibition of vasodilatation [20, 30]. Further evidences are required to clarify the accurate mechanisms of efficacy of intradiscal MB injection.

Although MB might leak into the spinal canal through annular tears, no side effects or complications were discovered in the group of patients treated with intradiscal MB injection. We presumed that MB may act only on nerve endings or nociceptors, because no evidence of nerve root injury was found. The exact mechanisms of the effect of intradiscal MB injection are not yet clearly understood. Because of high incidence and high disability rate of chronic discogenic low back pain, further clinical and experimental studies appear extremely necessary.

Our preliminary outcomes are encouraging. In the current study, we have tried an effective and minimally invasive method for the treatment of intractable and incapacitating discogenic low back pain, and its result seems to be superior to interbody fusion surgery or IDET [7–10, 14, 22, 26–28], in that it is less traumatic, lower cost, as well as it can be done immediately following discography. Doubtlessly, an interbody fusion surgery remains optional for the patients who do not respond to intradiscal MB injection.

Acknowledgement

Supported in part by a grant for scientific research of great project of clinical new technique from 304th Hospital of PLA. Also supported in part by the Foundation of capital medical development, Beijing, China.

References

- 1.Andersson GBJ. Epidemiology of low back pain. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69(Suppl 281):28–33. doi: 10.1080/17453674.1998.11744790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birski G, Silberstein M. The symptomatic lumbar disc in patients with low-back pain: magnetic resonance imaging appearances in both a symptomatic and control population. Spine. 1993;18:1808–1811. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eusebio EB, Graham J, Mody N. Treatment of intractable pruritus ani. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:770–772. doi: 10.1007/BF02052324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, et al. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66:271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farouk R, Lee WR. Intradermal methylene blue injection for the treatment of intractable idiopathic pruritus ani. Br J Surg. 1997;84:670. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800840524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman BJ, Walters RM, Moore RJ, Fraser RD (2003) Does intradiscal electrothermal therapy denervate and repair experimentally induced posterolateral annular tears in an animal model? Spine 28:2602–2608 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.FritzellP, Hagg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A. The Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. 2001 Volve award winner in clinical studies: lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain. A multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine. 2001;23:2521–2534. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A. The Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Chronic low back pain and fusion: a comparison of three surgical techniques. Spine. 2002;27:1131–1141. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanley EN, David SM. Lumbar arthrodesis for the treatment of back pain. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1999;81:716–730. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199905000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horton WC, Daftari TK. Which disc as visualized by magnetic resonance imaging is actually a source of pain? A correlation between magnetic resonance imaging and discography. Spine. 1992;17:S164–S171. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199206001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito M, Incorvaia KM, Yu SF, et al. Predictive signs of discogenic lumbar pain on magnetic resonance imaging with discography correlation. Spine. 1998;23:1252–1260. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199806010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kachael K, Bogduk N. Twelve-month follow-up of a controlled trial of intradiscal thermal anuloplasty for back pain due to internal disc disruption. Spine. 2000;25:2601–2607. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CK, Vessa P, Lee JY. Chronic disabling low back pain syndrome caused by internal disc derangements. The results of disc excision and posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine. 1995;20:356–361. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199502000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mentes BB, Akin M, Leventoglu S, Gultekin FA, Oguz M. Intradermal methylene blue injection for the treatment of intractable idiopathic pruritus ani: results of 30 cases. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8:11–14. doi: 10.1007/s10151-004-0043-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moneta GB, Videman T, Kaivanto K, et al. Reported pain during lumbar discography as a function of anular ruptures and disc degeneration: a re-analysis of 833 discograms. Spine. 1994;19:1968–1974. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199409000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mooney V. Where is the pain coming from? Spine. 1987;12:754–759. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198710000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore KR, Pinto MR, Butler LM. Degenerative disc disease treated with combined anterior and posterior arthrodesis and posterior instrumentation. Spine. 2002;27:1680–1686. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200208010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pauza KJ, Howell S, Dreyfuss P, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of intradiscal electrothermal therapy for the treatment of discogenic low back pain. Spine J. 2004;4:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearce WJ, Reynier-Rebuffel AM, Lee J, Aubineau P, Ignarro L, Seylaz J. Effects of methylene blue on hypoxic cerebral vasodilatation in the rabbit. J Pharmacol Exp. 1990;254:616–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng B, Wu W, Hou S, Zhang C, Li P, Yang Y. The pathogenesis of discogenic low back pain. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005;87:62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Penta M, Fraser RD. Anterior lumbar interbody fusion. A minimum 10-year follow-up. Spine. 1997;22:2429–2434. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199710150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell MC, Wilson M, Szypryt S, Symonds EM. Prevalence of lumbar disc degeneration observed by magnetic resonance in symptomless women. Lancet. 1986;2:1366–1367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)92008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren CP. Long-acting local analgesic antidyne in anal operation. Chin Med J. 1978;4:158–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhyne AL, Smith SE, Wood KE, Darden BV. Outcome of unoperated discogram-positive low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:1997–2001. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saal JA, Saal JS. Intradiscal electrothermal treatment for chronic discogenic low back pain: prospective outcome study with a minimum 1-year follow-up. Spine. 2000;25:2622–2627. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saal JS, Saal JA. Management of chronic discogenic low back pain with a thermal intradiscal catheter: a preliminary report. Spine. 2000;25:382–388. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200002010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saal JA, Saal JS. Intradiscal electrothermal treatment for chronic discogenic low back pain: prospective outcome study with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Spine. 2002;27:966–974. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200205010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saifuddin A, Braithwaite I, White J, Taylor BA, Renton P. The value of lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging in the demonstration of anular tears. Spine. 1998;23:453–457. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199802150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobey CG, Woodman OL, Dusting GJ. Inhibition of vasodilatation by methylene blue in large and small arteries of the dog hindlimb in vivo. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1988;15:401–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1988.tb01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wainwright M, Crossley KB. Methylene blue—a therapeutic dye for all seasons? J Chemother. 2002;14:431–443. doi: 10.1179/joc.2002.14.5.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]