Abstract

Nerve growth factor (NGF), a member of the neurotrophin family, has been identified as an essential growth factor supporting stem cell self-renewal outside the nervous system and was previously shown to stimulate corneal epithelial proliferation both in vivo and in vitro. In this study, we evaluated the expression of NGF and its corresponding receptors in the human corneal and limbal tissues, as well as in primary limbal epithelial cultures by immunofluorescent staining and relatively quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. We found that NGF was uniquely expressed in the human limbal basal epithelium, together with its two corresponding receptors: the high-affinity receptor TrkA and the low-affinity receptor p75NTR. TrkA was shown to preferentially localize to limbal basal epithelial cells. NGF and TrkA were also found co-localized with stem cell-associated molecular markers (drug-resistance transporter ABCG2 and p63), but not with the differentiation marker cytokeratin 3 in the human limbal basal epithelial layer. In cultured limbal epithelial cells, NGF and TrkA were found to be preferentially expressed by a small population of limbal epithelial cells. The NGF and TrkA immuno-positive subpopulations were enriched for certain properties (including ABCG2 and p63 expression) of putative limbal epithelial stem cells (P <0.01, compared with the entire cell population). Levels of NGF and TrkA transcripts were found to be much more abundant in limbal than in corneal tissues, and in young cultured cells in the proliferative stage than in air-lifted stratified cultures containing differentiated cells. The co-expression of NGF with its two corresponding receptors in limbal basal epithelial cells, but not in the cornea, suggests that NGF may function as a critical autocrine or paracrine factor supporting stem cell self-renewal in the limbal stem cell niche. The spatial expression of NGF and TrkA by small clusters of basal cells interspersed between negative cell patches suggests that they are potential markers for human corneal epithelial progenitor cells.

Keywords: cornea, epithelium, progenitor cell, nerve growth factor, nerve growth factor receptor, neurotrophin, TrkA, p75

1. Introduction

The basal epithelial cells in the limbal region of the cornea are not homogeneous, but consist of diverse populations of stem cells, transit amplifying cells (TACs) and terminally differentiated cells (TDCs) (Cotsarelis et al., 1989; Lehrer et al., 1998; Schermer et al., 1986; Tseng, 1996). During the last decade, progress has been made towards identifying molecular markers for distinguishing stem cells from TACs in situ. To date no definitive markers for these stem cells have been identified.

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is a member of the neurotrophin family (NT), which also comprise brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophin (NT) -3, NT-4/5 and NT-6 (Chao et al., 2006; Maness et al., 1994). NTs share the same low-affinity neurotrophin receptor p75NTR, but use different members of the tyrosine kinase (Trk) receptors: TrkA, TrkB, and TrkC (Huang and Reichardt, 2003) for high-affinity binding and signal transduction. NGF preferentially activates TrkA; BDNF and NT-4/5 preferentially bind to TrkB; and NT-3 signals through TrkC.

In addition to its general role as a growth and survival factor in the nervous system, NGF has been reported to possess diverse biological effects on stem cells outside the nervous system (Daiko et al., 2006). The expression of NGF and its receptors in the corneal epithelium has been investigated. TrkA has been shown to preferentially localize to limbal basal epithelial cells and was proposed as a potential marker for corneal limbal stem cells (Lambiase et al., 1998a; Stepp and Zieske, 2005; Touhami et al., 2002). Transcripts encoding NGF were detected in the corneal epithelium ex vivo, as well as in cultured corneal epithelium (You et al., 2000). Recent clinical reports demonstrated that murine NGF treatment promotes corneal wound healing in eyes with neurotrophic ulcers (Bonini et al., 2000; Lambiase et al., 1998b; Tan et al., 2006). Despite these findings, the spatial expression and localization of NGF in the stem cell-containing limbus has not been defined. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the expression of NGF with its receptors in human corneal and limbal epithelia, as well as in primary limbal epithelial cell cultures, with the intention of determining whether NGF and TrkA could serve as potential markers for the phenotype of human corneal epithelial stem cells.

2. Marerials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

Cell culture dishes, plates, centrifuge tubes and other plastic items were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Bedford, MA; http://www.bdbiosciences.com). Optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and cryomolds were from Sakura Finetek USA Inc (Torrance, CA; http://www.sakura-americas.com). Nunc Lab-Tek II eight-chamber slides were from VWR International (West Chester, PA; http://www.vwr.com). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Hyclone (Logan, UT; http://www.hyclone.com). Progenitor cell targeted corneal epithelium medium (CnT-20) and affinity-purified mouse monoclonal antibody against p75NTR were purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA; http://www.chemicon.com). Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) against NGF (M20), TrkA (763) and their antibody-specific blocking peptides were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA; http://www.scbt.com). Mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) against human p63 (4A4) was purchased from Lab Vision (Fremont, CA; http://www.labvision.com). Human ABCG2 mAb (BXP-21) was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA; http://www.calbiochem.com). Human AE5 mAb for cytokeratin 3 (K3) was from ICN Pharmaceuticals (Costa Mesa, CA; http://www.icnpharm.com). Fluorescein Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and 594 (red) conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG and 0.25% trypsin/0.03% EDTA solution were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA; http://www.invitrogen.com). Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide (PI) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO; http://www.sigmaaldrich.com). GeneAmp RNA-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit and Tagman Universal PCR master mix were from Applied BioSystems (Foster City, CA; http://www.appliedbiosystems.com). Ready-To-Go You-Prime First-Strand Beads were from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ; http://www.amersham.com).

2.2. Human Corneal and Limbal Tissue Preparation

Fresh normal human corneal tissues (less than 48 hours post mortem) for immunostaining were obtained from the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI, Philadelphia, PA) for this study. The corneal and limbal specimens were prepared using a previously described method (Chen et al., 2004). The limbal area was defined by the end of the Bowman’s layer, where vascularized connective tissue was noted. The peripheral cornea was defined as the region located 2 mm from this limbal landmark towards the cornea, where the underlying stroma was compact and avascular. The central cornea was defined as 4 mm from the limbal landmark towards the center of the button.

2.3. Primary Human Limbal Epithelial Culture

Fresh human corneoscleral tissues (preserved in less then 7 days) were obtained from the Lions Eye Bank of Texas (LEBT, Houston, TX). Primary human corneal epithelial cultures were established from limbal explants using a previously described method (Kim et al., 2004; Li and Tseng, 1995) with modification. In brief, each limbal rim was cut into 12 equal pieces (about 2×2 mm size each) and cultured in CnT-20 media. For immunofluorescent staining, sub-confluent primary cultures at days 18–21 were trypsinized and seeded into wells of 8-chamber culture slides (approximately 2×104 cells per chamber) overnight.

2.4. Immunofluorescent Staining and Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy (LSCM)

Immunofluorescent staining was performed to evaluate the expression and location of NGF (1:200) and its receptors TrkA (1:200), p75NTR (1:100) in human corneal and limbal frozen sections, as well as in primary limbal epithelial cultures, using a previously reported method (Chen et al., 2004; de Paiva et al., 2005; Li and Tseng, 1995) with modification. In brief, human corneal and limbal frozen sections were fixed in cold methanol:acetone (1:1) at −30°C for 3 minutes; cultured limbal epithelial cells were fixed in cold methanol at 4°C for 10 minutes. The staining was evaluated with an epifluorescent microscope (Eclipse 400; Nikon) and photographed with a digital camera (model DMX 1200; Nikon) or with a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with excitation at 488 and 543 nm, and using emission filters LP505 and LP560, respectively. The immuno-positive cells were assessed by point counting, using a previously reported method (Chen et al., 2006).

For double-staining of NGF and TrkA with stem cell and differentiation associated markers, one of the pAbs against NGF or TrkA and one of the mAbs against human p63 (1:600), ABCG2 (1:40) or K3 (1:200) were used in combination. Sections without primary antibodies applied, or those receiving the primary antibody pre-neutralized with 5 fold excess of its corresponding antibody-specific blocking peptides (NGF or TrkA) for 2 hours, were used as negative controls.

2.5. RNA Isolation and Relatively Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Fresh normal human limbal and corneal epithelia were obtained. Cells in primary limbal epithelial cultures were collected at different growth stages: 40% confluent, 90% confluent and 7 days post-airlifting after reaching confluence. Total RNA was isolated by acid guanidium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction using our previously described method (Chen et al., 2004; Li and Tseng, 1995). RNA concentration was quantified by its absorption at 260 nm and stored at −80°C before use. Relatively quantitative real-time PCR was performed by a previously described method (Chen et al., 2006; Luo et al., 2004) in a commercial thermocycling system (Mx3005PTM QPCR System; Stratagene, LA Jolla, CA). TaqMan primers are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. TaqMan gene expression assays used for relatively quantitative real-time PCR.

| Gene name | Symbol | Assay ID* |

|---|---|---|

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | Hs99999905_m1 |

| nerve growth factor, beta polypeptide | NGFB | Hs00171458_m1 |

| neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type 1 | NTRK1 | Hs00176787_m1 |

Identification number from Applied Biosystems (www.appliedbiosystems.com).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test was used to compare difference between two groups. One-way ANOVA was used to make comparisons among three groups, and the Dunnett’s test was further used to compare each treated group with the control group. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of NGF and its Receptors TrkA and p75NTR in Human Corneal Limbal Epithelial Tissue

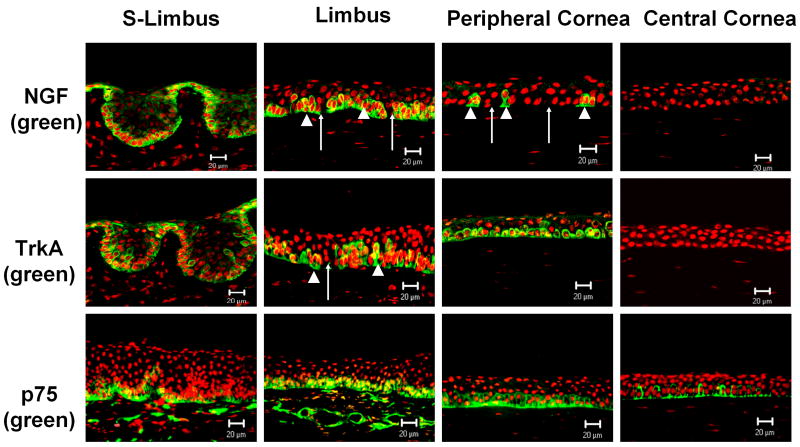

As shown in Figure 1, staining was evaluated in sections cut in two different orientations, cross sectional and meridional, as shown with PI counterstaining. The horizontal cross-section cut through the superior limbus (S-Limbus) showed the papilla-like limbal epithelial columns; the meridional sections cut from the limbus through the central cornea displayed a traditional view of the limbus (Limbus) with about 8–10 epithelial layers and the central cornea with about five epithelial layers (Central Cornea).

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescent staining of NGF, TrkA and p75 (green) in human corneoscleral tissue sections with propidium iodide nuclear counterstaining (red). S-Limbus, the horizontal cross-section cut through the superior limbus showed the papilla-like limbal epithelial columns; Limbus, the meridional sections cut from the limbus through the central cornea displayed a traditional view of the limbus. Arrow heads (▲) mark small clusters of immuno-positive basal cells; arrows (↑) mark negative cell patches. Scale bars, 20 μm.

NGF immuno-reactivity was found to be exclusively localized to a subset of the basal human limbal epithelial cells (Fig. 1, S-Limbus); the suprabasal layers of the limbal epithelium and the entire corneal epithelium were totally negative (Fig. 1). Clusters of NGF positive cells were interspersed between negative basal cells in the limbal palisades (Fig. 1, Limbus). Moving from limbus towards the peripheral cornea, the positive cell clusters were observed to be looser and smaller and were separated with more negatively stained cells till then they disappeared (Fig. 1, Peripheral cornea).The expression pattern of TrkA was consistent with the previous reports (Lambiase et al., 1998a; Touhami et al., 2002). It shared a similar expression pattern as its ligand, but extended to some suprabasal limbal epithelial cells and to the basal cells of the peripheral cornea. Central cornea showed no TrkA staining (Fig. 1). The specific immunoreactivity to NGF or TrkA was abolished in negative control sections where these antibodies were neutralized with their specific blocking peptides (data not shown). p75NTR was found to stain the basal and immediate suprabasal epithelial layers from the limbus to the central cornea. The superficial epithelial layers in the cornea and limbus were negative (Fig.1).

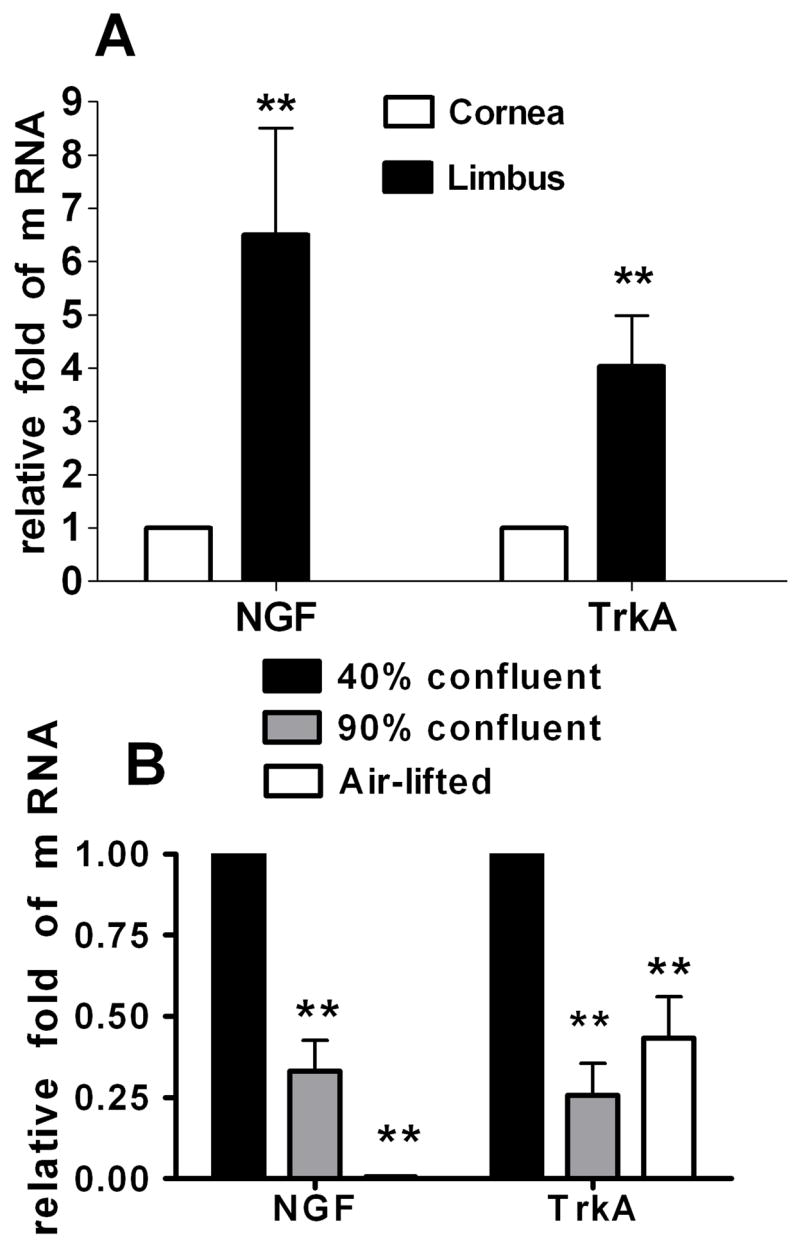

Real-time PCR showed that levels of NGF and TrkA mRNA transcripts were 4-6 folds higher in the limbal than in the corneal epithelia (Fig. 2A, Student’s t-test, P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Expression of NGF and TrkA mRNA in the human limbal epithelia (A) and in primary cell cultures at 40% confluent, 90% confluent and air-lifted stages (B) evaluated by relative quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Levels of NGF and TrkA mRNA transcripts were much higher in the limbal than in the corneal epithelia (A. n = 8; Student’s t-test, compared with corneal epithelium); both transcripts decreased more than half in 90% confluent cultures and in the airlifted stratified limbal epithelial cultures (B. n = 5; Dunnett’s test, compared with 40% confluent cells). NGF mRNA was barely detectable in the airlifted stratified limbal epithelial cultures. **, P < 0.01.

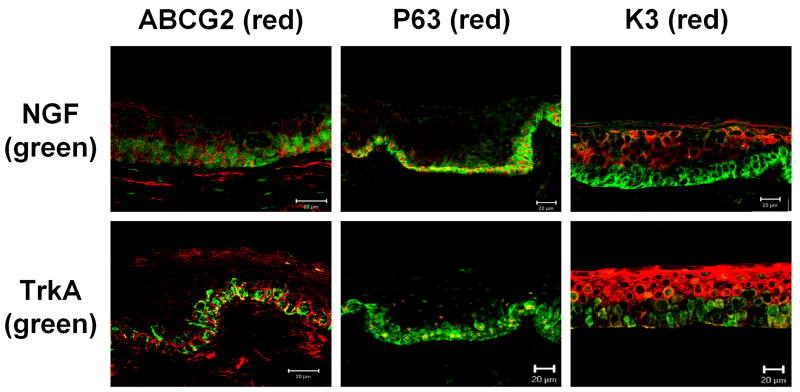

3.2. Co-expression of NGF and TrkA with Stem Cell Associated and Differentiation Marker in Human Limbal Epithelial Tissue

Our group has characterized three expression patterns of molecular markers by human limbal basal epithelial cells (Chen et al., 2004): (1) exclusively positive for p63, ABCG2 and integrin α9 by a subset of basal cells; (2) relatively higher expression of integrin β1, EGFR, K19 and α-enolase by most basal cells, and (3) lack of expression of nestin, E-cadherin, connexin 43, involucrin, K3 and K12. The first two groups are stem cell-associated markers and the third one is differentiation marker. In this study, we chose to evaluate the co-expression of NGF and TrkA with the stem cell-associated markers ABCG2 and p63 and with the differentiation marker K3 in the frozen sections of human limbal tissues.

The staining patterns for ABCG2, p63 and K3 were consistent with our previously report (Chen et al., 2004). As shown in Figure 3, ABCG2 was primarily immunodetected in the cell membranes of certain limbal basal epithelial cells, but not in most limbal suprabasal and corneal epithelial cells. p63 was immunodetected primarily in the nuclei of basal limbal epithelium, and of some suprabasal limbal epithelial cells. K3, a corneal specific keratin (Schermer et al., 1986), was strongly expressed by all corneal and the superficial limbal epithelia, but not by the basal and suprabasal layers of the limbal epithelium. NGF and TrkA were noted to be co-expressed by ABCG2 and p63 positive cells in the limbal basal layer. All NGF and TrkA positive cells were K3 negative (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Dual immunofluorescent staining of NGF and TrkA (green) with ABCG2, p63 and K3 (red) in human limbal tissue frozen sections. NGF and TrkA were co-expressed by ABCG2 (membrane) and p63 (nuclei) positive cells in the limbal basal layer. All NGF and TrkA positive cells were K3 negative (red). Scale bars, 20 μm.

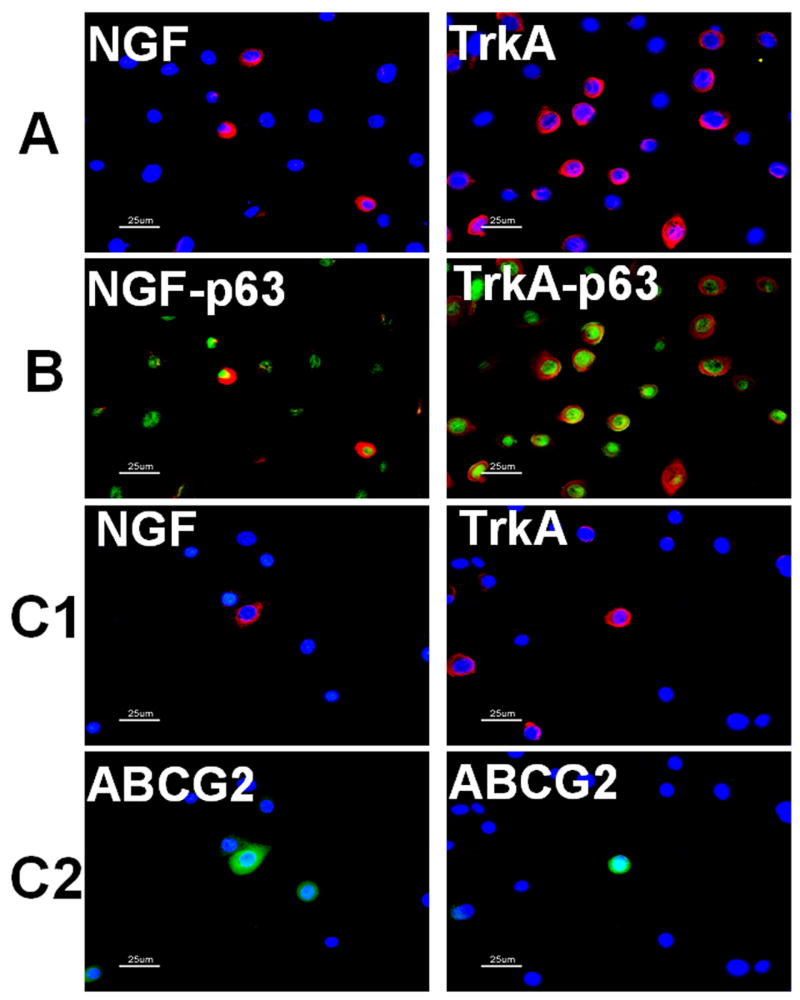

3.3. Expression of NGF and TrkA in Primary Human Limbal Epithelial Cultures

In cultured limbal epithelial cells, NGF and TrkA were expressed in the cell membranes or cytoplasm (Fig. 4A). Expressed as a percentage of the entire cell culture population evaluated in three separate experiments, 19.6±5.6% of cells were NGF positive, and 35.8±8.8% of cells were TrkA positive. Evaluated by real-time PCR, the expression levels of NGF and TrkA mRNA were significantly different among the cells in 3 stages of growth and differentiation (one-way ANOVA, NGF, P < 0.0001; TrkA, P < 0.001). Compared with 40% confluent limbal epithelium cultures, the transcription levels of NGF and TrkA mRNA were found to decrease more than half in both 90% confluent and in the airlifted stratified cultures (Fig. 2B, Dunnett’s test, P < 0.01). NGF mRNA was barely detectable in the airlifted stratified limbal epithelial cultures (Fig. 2B).

Figure 4.

Single immunofluorescent staining of NGF and TrkA (A), double staining of NGF and TrkA with p63 (B), ABCG2 (C) in human limbal epithelial cultures established from limbal explants with Hoechst 33342 nuclear counterstaining (blue). NGF and TrkA were preferentially expressed in the cytoplasm or membrane of small population of corneal epithelial cells (A, red). The NGF and TrkA immuno-positive subpopulations (B and C1, red) expressed higher levels of p63 (B, green) and ABCG2 (C2, green). Scale bars, 25 μm. These images are representative of the data summarized in Table 2.

3.4. The NGF and TrkA Immuno-Positive Subpopulations Expressed Higher Levels of ABCG2, p63 Protein in Primary Limbal Epithelial Cultures

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 4, double immunofluorescent staining in the limbal epithelial cultures showed that the numbers of p63 and ABCG2 positive were significantly different among NGF and TrkA immuno-positive subpopulations and entire cell population (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001 in all groups). Compared with the entire cell population, the NGF and TrkA positive subpopulations contained more p63 positive cells (Fig. 4B and Table 2, Dunnett’s test, P < 0.01). NGF positive subpopulation contained more ABCG2 positive cells (Fig. 4C and Table 2, Dunnett’s test, P < 0.01), while the TrkA positive subpopulation contained more, but not significantly, ABCG2 positive cells (Fig. 4C and Table 2, Dunnett’s test, P > 0.05).

Table 2. Percentage (Mean±SD) of ABCG2 and p63 positive cells in the entire cell population and in the NGF and TrkA immuno-positive subpopulations in human limbal epithelial cultures.

| ABCG2+ (%) | p63+ (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Entire cell population | 10.6±3.4 | 35.3±10.4 |

| NGF positive subpopulation | 48.6±14.7** | 84.8±10.2** |

| TrkA positive subpopulation | 19.8±8.2 | 60.2±15.1** |

, p <0.05

p <0.01 (n = 3; Dunnett’s test, compared with the entire cell population).

4. Discussion

Limbal epithelial stem cells exhibit unique characteristics that satisfy the widely accepted criteria for defining adult stem cells, which include 1) slow-cycling or long cell-cycle time during homeostasis in vivo; 2) small size and a poor state of differentiation with primitive cytoplasm; 3) high proliferative potential after wounding or placement in culture; and 4) the ability for self-renewal and functional tissue regeneration.

Although NGF is known as a neuronal survival factor, it has been previously shown to stimulate corneal epithelial proliferation both in vitro (You et al., 2000) and in vivo. Our study revealed the spatial expression pattern of NGF mimics the distribution of putative stem cell markers in the human limbal cornea.

4.1. NGF was Found to be Uniquely Expressed in the Human Limbal Epithelium

Using in situ immunolabeling, we found that NGF was uniquely expressed in the human limbal basal epithelium, together with its high-affinity receptor TrkA and its low-affinity receptor p75NTR. Additionally, NGF was only expressed by a small population of limbal epithelial cells in culture. The level of NGF transcripts was found to be much more abundant in limbal than in corneal epithelial tissues, and in young cultured cells in the proliferative stage than in more differentiated air-lifted stratified cultures. These studies indicate that NGF is uniquely expressed in the human limbal epithelium.

Corneal epithelial stem cells reside in the limbal palisades of Vogt, a unique stem cell niche microenvironment (Chen et al., 2004; Li et al., 2007; Stepp and Zieske, 2005). The stem cells are maintained by a combination of factors intrinsic to the stem cells themselves and extrinsic from their environment. p75NTR is a member of the tumor necrosis factor family and regulates the affinity of the Trk receptors for their NTs (Chao et al., 2006). It is believed that coexpression of p75NTR and Trk receptors leads to NT signaling through Trk receptors and promotion of cell survival (Carter and Lewin, 1997; Dechant and Barde, 1997), whereas expression of p75NTR alone without the Trk receptors promotes apoptosis of NT target cells (Seidl et al., 1998; Wexler et al., 1998). Our study showed that the co-expression of NGF with its two corresponding receptors in limbal basal epithelial cells, but not in the cornea, suggests that NGF may function as an autocrine or paracrine factor controlling limbal stem cell survival. Further studies are necessary to investigate the functional role of NGF in the human limbal stem cell niche.

4.2. NGF and TrkA May Serve as Potential Markers for Human Corneal Epithelial Progenitor Cells

Stem cells are believed to represent less than 10% of the total limbal basal cell population (Lavker et al., 1991), whereas the majority of the other cells are early TACs, which may display some stem cell characteristics (Lehrer et al., 1998). The spatial expression of NGF and TrkA by small clusters of basal cells interspersed between negative cell patches suggests they are potential candidate markers for human corneal epithelial progenitor cells.

4.2.1. NGF and TrkA was Co-Expressed with Stem Cell-Associated, but not with Differentiation Markers in the Human Limbal Basal Epithelial Layer

Although large discrepancies have been noted in p63 expression patterns in human corneal basal epithelial cells (Chen et al., 2004; Dua et al., 2003; Pellegrini et al., 2001), all studies concur that the basal p63-positive cell population does not represent and at best includes corneal epithelial stem cells. Rather, p63 identifies cells in a proliferative state, such as TACs (Schlotzer-Schrehardt and Kruse, 2005). ABCG2 is another marker that has been proposed to identify the putative limbal epithelial stem cells (Budak et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2004; de Paiva et al., 2005; Watanabe et al., 2004). Our study showed that NGF and TrkA were co-expressed with ABCG2 and p63, but not with K3 in the limbal basal epithelial layer. In primary limbal epithelial cultures, fewer cells expressed NGF (19.6±5.6%) than p63 (35.3±10.4%), almost as the same number of cells expressed TrkA (35.8±8.8%) as they expressed p63. This suggests that like ABCG2 and p63, NGF and TrkA might potentially serve as markers for human corneal epithelial progenitor cells.

4.2.2. NGF and TrkA Immuno-Positive Subpopulations were Enriched for Certain Properties of Putative Limbal Epithelial Stem Cells in Primary Limbal Epithelial Cultures

It is believed that limbal epithelial cultures contain stem cells, TACs, and TDCs, although some properties of the stem cells in vivo may be changed or lost in culture due to the different microenvironment. We previously reported (de Paiva et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2004) that ABCG2 and p63 antibodies mainly stained subpopulations of small cells, 10.62 ± 4.04% and 18.3±4.3% respectively, in primary human limbal epithelial cells cultured in SHEM. Limbal epithelial stem cells were considered to be included among these positive cells. Our current study found roughly the same percentage of ABCG2 (10.6±3.4%) positive cells and a higher percentage of p63 (35.3±10.4%) positive cells in CnT-20 cultured cells. This indicates that CnT-20 media may keep these progenitor cells more in a primitive undifferentiated state. Dual immunofluorescent staining showed that the NGF and TrkA immuno-positive subpopulations contained a greater percentage of p63 (P < 0.01) and ABCG2 (P < 0.01 in NGF immuno-positive subpopulation) positive cells than the entire cell population.

Stem cell-associated proteins presumably play a special role in maintaining the corneal epithelial stem cell niche: p63 is a marker of higher proliferative potential; ABCG2 may protect cell from damage by drugs and toxins (Chen et al., 2004; Schlotzer-Schrehardt and Kruse, 2005). Like these factors, NGF may play a unique role by supporting stem cell survival and self-renewal in the limbal stem cell niche.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Lions Eye Bank of Texas for kindly providing human corneoscleral tissues.

This study was supported by NIH Grants EY11915 (SCP), EY014553 (DQL) and NS35280 (HDS), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; a grant from Lions Eye Bank Foundation; an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, the Oshman Foundation and the William Stamps Farish Fund.

This study was presented in part as abstract at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, May 6–10, 2007, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bonini S, Lambiase A, Rama P, Caprioglio G, Aloe L. Topical treatment with nerve growth factor for neurotrophic keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1347–1351. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budak MT, Alpdogan OS, Zhou M, Lavker RM, Akinci MA, Wolosin JM. Ocular surface epithelia contain ABCG2-dependent side population cells exhibiting features associated with stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1715–1724. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BD, Lewin GR. Neurotrophins live or let die: does p75NTR decide? Neuron. 1997;18:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao MV, Rajagopal R, Lee FS. Neurotrophin signalling in health and disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110:167–173. doi: 10.1042/CS20050163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, de Paiva CS, Luo L, Kretzer FL, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. Characterization of putative stem cell phenotype in human limbal epithelia. Stem Cells. 2004;22:355–366. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-3-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Evans WH, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. Gap junction protein connexin 43 serves as a negative marker for a stem cell-containing population of human limbal epithelial cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1265–1273. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotsarelis G, Cheng SZ, Dong G, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Existence of slow-cycling limbal epithelial basal cells that can be preferentially stimulated to proliferate: implications on epithelial stem cells. Cell. 1989;57:201–209. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90958-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daiko H, Isohata N, Sano M, Aoyagi K, Ogawa K, Kameoka S, Yoshida T, Sasaki H. Molecular profiles of the mouse postnatal development of the esophageal epithelium showing delayed growth start. Int J Mol Med. 2006;18:1057–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paiva CS, Chen Z, Corrales RM, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. ABCG2 transporter identifies a population of clonogenic human limbal epithelial cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:63–73. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechant G, Barde YA. Signalling through the neurotrophin receptor p75NTR. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:413–418. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dua HS, Joseph A, Shanmuganathan VA, Jones RE. Stem cell differentiation and the effects of deficiency. Eye. 2003;17:877–885. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:609–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Jun SX, de Paiva CS, Chen Z, Pflugfelder SC, Li D-Q. Phenotypic characterization of human corneal epithelial cells expanded ex vivo from limbal explant and single cell cultures. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambiase A, Bonini S, Micera A, Rama P, Bonini S, Aloe L. Expression of nerve growth factor receptors on the ocular surface in healthy subjects and during manifestation of inflammatory diseases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998a;39:1272–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambiase A, Rama P, Bonini S, Caprioglio G, Aloe L. Topical treatment with nerve growth factor for corneal neurotrophic ulcers. N Engl J Med. 1998b;338:1174–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804233381702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavker RM, Dong G, Cheng SZ, Kudoh K, Cotsarelis G, Sun TT. Relative proliferative rates of limbal and corneal epithelia. Implications of corneal epithelial migration, circadian rhythm, and suprabasally located DNA-synthesizing keratinocytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:1864–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer MS, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Strategies of epithelial repair: modulation of stem cell and transit amplifying cell proliferation. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 19):2867–2875. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.19.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DQ, Tseng SC. Three patterns of cytokine expression potentially involved in epithelial-fibroblast interactions of human ocular surface. J Cell Physiol. 1995;163:61–79. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Hayashida Y, Chen YT, Tseng SC. Niche regulation of corneal epithelial stem cells at the limbus. Cell Res. 2007;17:26–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, Li D-Q, Doshi A, Farley W, Corrales RM, Pflugfelder SC. Experimental dry eye stimulates production of inflammatory cytokines and MMP-9 and activates MAPK signaling pathways on the ocular surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4293–4301. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maness LM, Kastin AJ, Weber JT, Banks WA, Beckman BS, Zadina JE. The neurotrophins and their receptors: structure, function, and neuropathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1994;18:143–159. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini G, Dellambra E, Golisano O, Martinelli E, Fantozzi I, Bondanza S, Ponzin D, McKeon F, De Luca M. p63 identifies keratinocyte stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3156–3161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061032098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermer A, Galvin S, Sun T-T. Differentiation-related expression of a major 64K corneal keratin in vivo and in culture suggests limbal location of corneal epithelial stem cells. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:49–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Kruse FE. Identification and characterization of limbal stem cells. Exp Eye Res. 2005;81:247–264. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidl K, Erck C, Buchberger A. Evidence for the participation of nerve growth factor and its low-affinity receptor (p75NTR) in the regulation of the myogenic program. J Cell Physiol. 1998;176:10–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199807)176:1<10::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp MA, Zieske JD. The corneal epithelial stem cell niche. Ocul Surf. 2005;3:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MH, Bryars J, Moore J. Use of nerve growth factor to treat congenital neurotrophic corneal ulceration. Cornea. 2006;25:352–355. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000176609.42838.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touhami A, Grueterich M, Tseng SC. The role of NGF signaling in human limbal epithelium expanded by amniotic membrane culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:987–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng SCG. Regulation and clinical implications of corneal epithelial stem cells. Mol Biol Rep. 1996;23:47–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00357072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Nishida K, Yamato M, Umemoto T, Sumide T, Yamamoto K, Maeda N, Watanabe H, Okano T, Tano Y. Human limbal epithelium contains side population cells expressing the ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2. FEBS Lett. 2004;565:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler EM, Berkovich O, Nawy S. Role of the low-affinity NGF receptor (p75) in survival of retinal bipolar cells. Vis Neurosci. 1998;15:211–218. doi: 10.1017/s095252389815201x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You L, Kruse FE, Volcker HE. Neurotrophic factors in the human cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:692–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]