Abstract

In this report, we show that cross-presentation of self-antigens can lead to the peripheral deletion of autoreactive CD8+ T cells. We had previously shown that transfer of ovalbumin (OVA)-specific CD8+ T cells (OT-I cells) into rat insulin promoter–membrane-bound form of OVA transgenic mice, which express the model autoantigen OVA in the proximal tubular cells of the kidneys, the β cells of the pancreas, the thymus, and the testis of male mice, led to the activation of OT-I cells in the draining lymph nodes. This was due to class I–restricted cross-presentation of exogenous OVA on a bone marrow–derived antigen presenting cell (APC) population. Here, we show that adoptively transferred or thymically derived OT-I cells activated by cross-presentation are deleted from the peripheral pool of recirculating lymphocytes. Such deletion only required antigen recognition on a bone marrow–derived population, suggesting that cells of the professional APC class may be tolerogenic under these circumstances. Our results provide a mechanism by which the immune system can induce CD8+ T cell tolerance to autoantigens that are expressed outside the recirculation pathway of naive T cells.

Several mechanisms play a role in tolerance induction to extra thymic self-antigens. For class I–restricted CD8+ T cells, ignorance, anergy, and deletion can operate to render an animal tolerant to antigen expressed in peripheral tissues (1–14). However, the current dogma provides an interesting dilemma with regard to our understanding of how tolerance is achieved. Anergy and deletion both require interaction of T cells with the self-antigen, and naive T cells are thought not to recirculate through nonlymphoid tissue (15). Thus, those CD8+ T cells specific for antigens expressed only in nonlymphoid tissues, e.g., in the β cells of the pancreas, should not be susceptible to these forms of tolerance. This leaves ignorance as the only mechanism for avoiding autoimmunity to such antigens, a somewhat unsatisfactory situation because activated CD8+ T cells have wider recirculation pathways than naive cells (15), and can potentially cause autoimmune damage in tissues previously ignored (3, 4, 10). Consequently, we might expect autoimmunity to be more prevalent, or that additional tolerogenic mechanisms exist.

To date, many studies examining peripheral tolerance of CD8+ T cells have used MHC molecules as their model autoantigens (5–10, 14, 16). These molecules are seen only in an unprocessed form, and therefore only on those cells that themselves express the autoantigen. Although such studies have contributed to our understanding of the fate of autoreactive CD8+ T cells, they have not allowed for the possible effects of processing and presentation of tissue antigens by professional APCs.

Peptide antigens presented by MHC class I molecules are generally thought to be derived from intracellularly synthesized proteins (17–19). However, exogenous antigens can also be presented by class I MHC molecules under certain circumstances (20–26) and the induction of CTL via this exogenous pathway for class I–restricted presentation has been referred to as cross-priming. We have recently shown that such presentation, when applied to self-antigens, can lead to the activation of autoreactive CD8+ T cells (27). These studies used the rat insulin promoter (RIP)1–mOVA transgenic mouse model, where a membrane-bound form of ovalbumin (mOVA) was expressed by pancreatic β cells, kidney proximal tubular cells, the thymus, and in the testis of male mice. Transgenic OVA-specific CD8+ T cells (OT-I cells) adoptively transferred into RIP–mOVA mice were activated in the lymph nodes draining OVA-expressing tissues. This activation was due to class I–restricted presentation of exogenously derived OVA on a bone marrow–derived APC population. Here, we investigate the fate of autoreactive CD8+ T cells activated by this cross-presentation pathway and provide evidence that these cells are deleted.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

All mice were bred and maintained at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research. For all experiments, female mice between 8 and 16 wk of age were used. RIP–mOVA and OT-I transgenic mice were generated and screened as previously described (27, 28).

Adult Thymectomized, Thymus-grafted, Bone Marrow Chimeras.

Adult thymectomized, thymus-grafted, bone marrow chimeric RIP-mOVA mice (TG-RIP mice) and nontransgenic mice (TG-nontransgenic mice) were generated as described (9, 14). In brief, 2–6 wk after adult thymectomy RIP–mOVA mice and their nontransgenic littermates were lethally irradiated with 900 cGy and reconstituted with T cell–depleted bone marrow from OT-I mice. The next day, radioresistant T cells were depleted with 100 μl of T24 (anti-Thy-1) ascites intraperitoneally. 1–2 wk after irradiation, mice were grafted with a sex-matched 1,500 cGy irradiated thymus graft from a nontransgenic newborn B6 mouse under the kidney capsule. This approach ensured that OT-I cells were not deleted intrathymically due to aberrant expression of OVA in this tissue.

Preparation of OT-I Cells for Adoptive Transfer.

OT-I RAG-1−/− cells were prepared from LN and spleens of transgenic mice as described (27). In brief, erythrocytes and macrophages were removed by treatment with the anti-heat stable antigen mAb J11d and complement. OT-I cells from RAG-1−/− mice were of a naive phenotype (CD44lo, CD69−, IL-2R−). 0.25–6 × 106 cells were injected intravenously into recipient mice.

5,6-Carboxy-Succinimidyl-Fluoresceine-Ester Labeling of OT-I Cells.

5,6-carboxy-succinimidyl-fluoresceine-ester (CFSE) labeling was performed as previously described (29–31). OT-I cells were resuspended in PBS containing 0.1% BSA (Sigma Chem. Co., St. Louis, MO) at 10 × 106 cells/ml. For fluorescence labeling, 2 μl of a CFSE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon) stock solution (5 mM in DMSO) were incubated with 10 × 106 cells for 10 min at 37°C.

FACS® Analysis.

LN or spleen cells were stained for three-color FACS® analysis as described (10), using the following mAbs: PE-conjugated anti-CD8 (YTS 169.4) was from Caltag (San Francisco, CA). Biotinylated anti-CD69 (H1.SF3) and PE-labeled anti– L-selectin (Mel-14) were from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Anti-Vα2 TCR (B20.1) and anti-Vβ5.1/2 TCR (MR9-4) mAbs (27) were conjugated to biotin or to FITC. Biotin-labeled Abs were detected with Streptavidin (SAVP)–Tricolor (Caltag). Analysis was performed on a FACScan® using Lysis II software. Live gates were set on lymphocytes by forward and side scatter profiles. 10,000–20,000 live cells were collected for analysis. OT-I donor cells in the LNs from recipient mice were identified by staining for Vα2+ Vβ5+ CD8+ cells.

For analysis of fluorescent labeled cells, 50,000 CD8+ cells were collected and analyzed using WEASEL software (F. Battye, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Melbourne, Australia).

Histology.

Tissues were fixed in Bouin's solution and paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard methods.

Results

Activation of OVA-specific CD8+ T Cells by Cross-presentation in RIP–mOVA Mice.

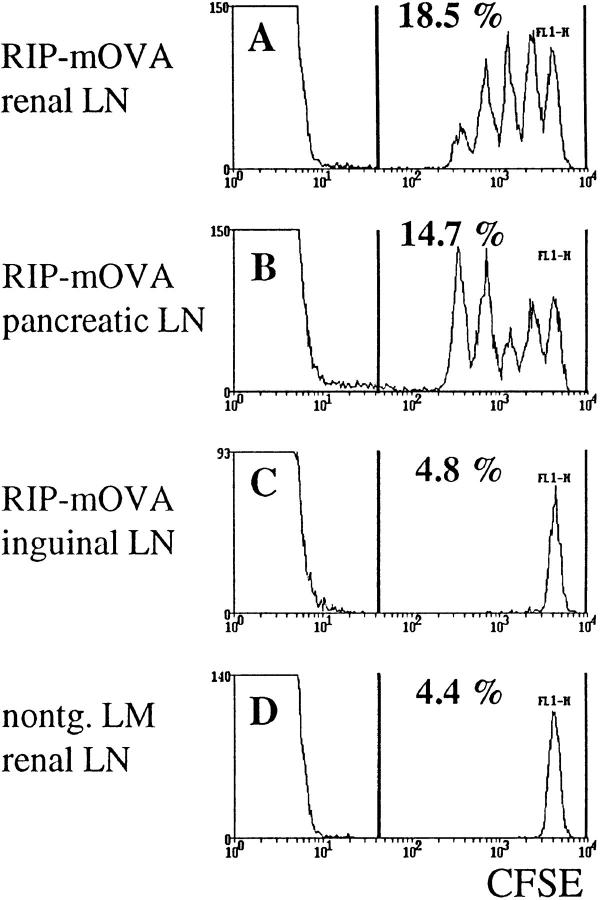

RIP–mOVA mice express a membrane-bound form of OVA in the β cells of the pancreas, the proximal tubular cells of the kidney, the thymus, and in the testis of male mice (27). When OVA-specific CD8+ T cells from the OT-I transgenic line (OT-I cells) were transferred into RIP–mOVA mice, they were activated in the draining lymph nodes of OVA-expressing tissues (27). In this report, we have used a novel and more sensitive method for the identification of proliferating cells in vivo (29–31). OT-I cells were labeled with the fluorescent dye CFSE and then transferred into RIP–mOVA mice. When CFSE-labeled cells divide, the two daughter cells receive approximately half of the original fluorescence, and their progeny a quarter, and so on. Thus, a cell that has divided n times will exhibit a 2n-fold reduced fluorescence intensity. Therefore, on a FACS® histogram, separate peaks appear for cells that have divided 1–8 times. After nine cell cycles, the fluorescent dye is diluted to background intensity. Fig. 1 shows the CFSE profiles of 5 × 106 OT-I cells transferred into RIP–mOVA mice 43 h earlier. Multiple peaks are seen only in the renal (Fig. 1 A) and pancreatic (Fig. 1 B) lymph nodes, confirming that OT-I cells were activated and proliferated only in these sites.

Figure 1.

Proliferation of OT-I cells in lymph nodes draining OVA-expressing tissues of RIP–mOVA mice. 5 × 106 CFSE-labeled OT-I cells were injected intravenously into RIP–mOVA mice and nontransgenic littermates. 43 h later, lymphocytes prepared from the renal (A), pancreatic (B), and inguinal (C) LN of RIP–mOVA mice, and from the renal LN of nontransgenic recipients were analyzed by flow cytometry. Profiles were gated on CD8+ cells.

Using the above technique, divided cells were first apparent at 25 h after transfer (data not shown). After 43 h, some OT-I cells had divided four times (Fig. 1), six times within 52 h (data not shown), greater than eight times within 68 h (Fig. 2). Therefore, one cell cycle required ∼4.5 h in vivo.

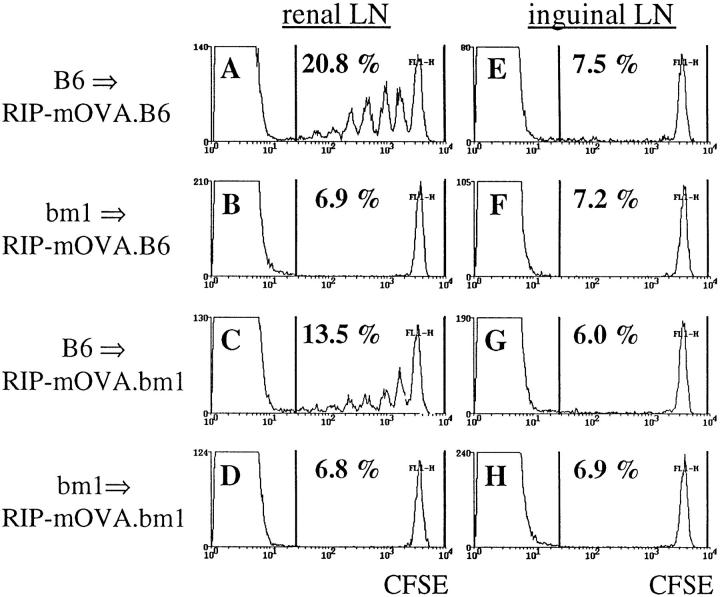

Figure 2.

Bone marrow–derived APC activate OT-I cells in the draining LN of RIP–mOVA mice. 5 × 106 CFSE labeled OT-I cells were transferred into RIP–mOVA mice backcrossed to B6 (A, B, E, F) or bm1 (C, D, G, H) and grafted with B6 (A, C, E, G) or bm1 (B, D, F, H) bone marrow. After 3 d, renal (A–D) and inguinal (E–H) lymph node cells were examined by flow cytometry. Profiles were gated for CD8+ cells.

These results indicate that OT-I cells were able to respond to antigen presented in the lymph nodes that drained OVA-expressing tissues. Previously, we showed that in the absence of a bone marrow–derived APC capable of presenting OVA to OT-I cells, no proliferation was observed (27). To determine whether OVA presentation by such bone marrow–derived APCs alone was sufficient to induce OT-I cell proliferation, we took advantage of bm1 mice, which express a mutation in the Kb molecule such that Kbm1 cannot present OVA to OT-I cells (32). RIP–mOVA mice, which were crossed onto the bm1 haplotype (RIP– mOVA.bm1), were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with B6 bone marrow (B6→ RIP–mOVA.bm1). In these chimeric mice, Kb is expressed by bone marrow–derived cells but not by peripheral tissue cells such as islet β cells or kidney proximal tubular cells. 5 × 106 CFSE-labeled OT-I cells were adoptively transferred into the chimeric RIP– mOVA mice and, 3 d later, lymphoid tissues were analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2). Proliferation of OT-I cells was observed in the renal (Fig. 2 C) and pancreatic (data not shown) nodes, but not in the inguinal lymph nodes of B6→ RIP–mOVA.bm1 chimeras (Fig. 2 G). This result showed that antigen presentation by bone marrow–derived cells was sufficient to induce proliferation of OT-I cells. The proliferation was not as intense as in normal RIP– mOVA mice (see Fig. 1), but was comparable to that seen in B6→ RIP–mOVA.B6 control chimeras that were entirely of the B6 haplotype (Fig. 2, A and E). This implied that the less vigorous response seen in chimeric mice may be the result of irradiation. As previously reported (27), OT-I cells were not activated when the bone marrow compartment was of the bm1 haplotype (bm1→ RIP–mOVA.B6 or bm1→ mOVA.bm1), indicating that antigen presentation by a bone marrow–derived cell was not only sufficient, but also essential for OT-I activation.

Deletion of Adoptively Transferred OT-I Cells in the Periphery of RIP–mOVA Mice.

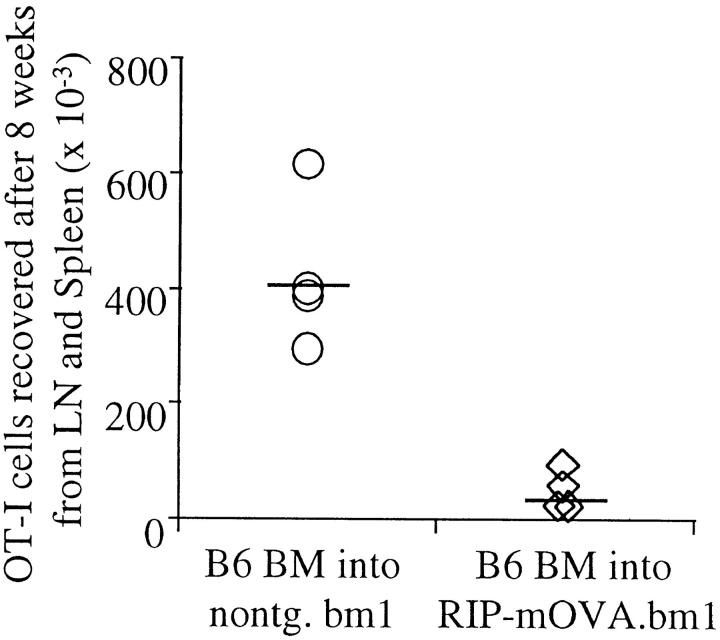

The above results indicate that a bone marrow–derived APC was capable of processing and presenting antigens expressed by peripheral tissues for activation of autoreactive CD8+ T cells. To determine how the immune system normally copes with such autoreactive cells, we examined the ultimate fate of these cells. To detect adoptively transferred OT-I cells in unirradiated recipients several weeks after transfer, it was necessary to inject at least 5 × 106 cells. However, under these circumstances OT-I cells infiltrated the pancreatic islets after day 3, and caused diabetes in 100% of 16 RIP–mOVA mice by day 9 (data not shown). Smaller numbers of cells, e.g., 0.25 × 106 cells, did not cause diabetes in 25 recipients, but detection of these few cells was not possible several weeks after transfer, even in nontransgenic controls. Presumably, OT-I cells were activated after transfer in both cases, but only the larger dose caused sufficient destruction to result in diabetes. To avoid the problem of β cell destruction, we transferred 6 × 106 OT-I cells into B6→ RIP–mOVA.bm1 chimeric mice, in which OT-I cells could recognize antigen on the cross-presenting bone marrow–derived APCs, but could not interact with OVA-expressing peripheral tissues of the bm1 haplotype. After 8 wk, far fewer OT-I cells were recovered from the lymphatic tissues of B6→ RIP– mOVA.bm1 mice than from nontransgenic B6→ bm1 mice (Fig. 3). These data suggest that OT-I cells were deleted after recognizing exogenously processed OVA on bone marrow–derived APC in the draining lymph nodes of OVA-expressing tissue.

Figure 3.

OT-I cells are deleted in response to recognition of antigen on cross-presenting APC. Bone marrow from B6 mice was grafted into RIP–mOVA.bm1 mice and nontransgenic littermates. 14 wk later, 6 × 106 OT-I cells were adoptively transferred, and after 8 wk the number of Vα2+Vβ5+CD8+ cells in the LN and spleen of the recipients was determined by flow cytometry. The proportion of Vα2+Vβ5+ cells in the CD8+ population was 7.5–10% in nontransgenic, and 1.4–3.5% in transgenic recipients. An average of 1.4% of CD8+ cells were Vα2+Vβ5+ in uninjected mice. To derive the total number of OT-I cells, this 1.4% was subtracted from the proportion of Vα2+Vβ5+ cells in the CD8+ cells in experimental mice and the difference was multiplied with the proportion of CD8+ T cells in the live cells and with the number of live cells. These results are representative for two such experiments consisting of four mice per group.

Deletion of Constitutively Produced OT-I Cells in the Periphery of RIP–mOVA Mice.

The adoptive transfer of 5 × 106 OT-I cells contrasts with the normal situation where small numbers of newly matured cells enter the periphery from the thymus each day. We reasoned that diabetes may have occurred because the normal tolerogenic mechanisms were unable to cope with such a large number of injected T cells.

To create a more physiological situation where OVA-specific CD8+ T cells would be generated continuously in the thymus, RIP–mOVA mice were manipulated to ensure that OVA could not be expressed in this compartment. This was achieved by thymectomizing RIP–mOVA mice and then grafting them with a nontransgenic B6 thymus. Such mice were then lethally irradiated and reconstituted with bone marrow from OT-I mice, and designated thymus-grafted RIP–mOVA mice (TG-RIP mice). This approach has been successfully used to exclude the effect of aberrant thymic antigen expression in other models (10, 14).

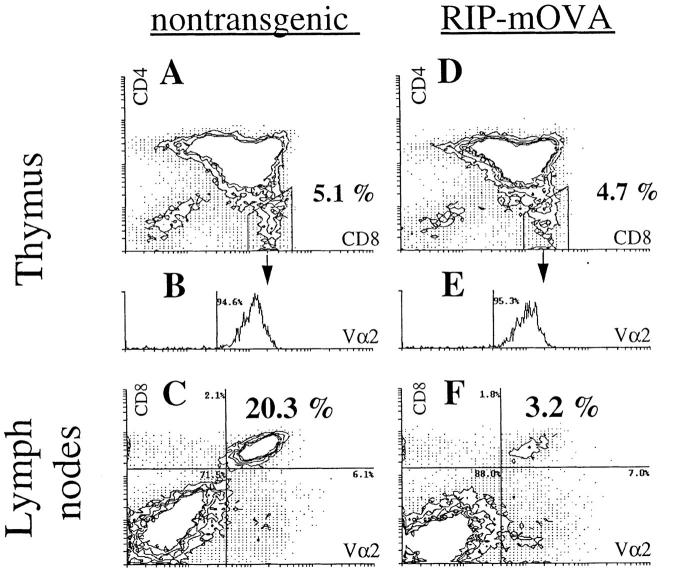

In contrast with the RIP–mOVA mice given large numbers of OT-I cells, which became diabetic within 9 d, only 1 of 12 TG-RIP mice developed the disease when followed for >116 d. Analysis of the thymus grafts 4 mo after implantation showed that OT-I cells (CD8+CD4−Vα2+ cells) were able to mature in TG-RIP mice (Fig. 4). The proportion of mature OT-I cells in the thymus was equivalent to that of nontransgenic controls (Fig. 4, A and D), supporting the view that the thymic deletion reported earlier for the double-transgenic mice (27) was the result of aberrant thymic expression of mOVA.

Figure 4.

Peripheral deletion of OT-I cells that mature in the thymus of TG-RIP mice. Thymus grafts from TG-littermate mice (A and B) and TG-RIP mice (D and E) were analyzed for CD4+, CD8+, and Vα2+ cells by flow cytometry 16 wk after bone marrow reconstitution. Expression of Vα2 by CD4−CD8+ cells is shown in the histograms B and E. LN cells of the same transgenic (C) and nontransgenic (F) mice were stained for CD8+ and Vα2+ expression. The same staining conditions for Vα2 were used for thymus and LN cells. The data shown here is representative for eight pairs of manipulated mice investigated.

Because OT-I cells matured in the thymus of TG-RIP mice, we could examine their fate after release into the peripheral immune system. Flow cytometric analysis of the lymph node populations of TG-RIP mice showed a significant reduction in the proportion of these cells relative to that seen in TG-nontransgenic mice (4.9 ± 2.4% versus 25.1 ± 8.2%, n = 8) (Fig. 4, C and F). Calculation of the total number of OT-I cells in the spleen and lymph node populations indicated that there was approximately a fivefold reduction of these cells in TG-RIP mice (2.28 ± 1.21 × 106 versus 12.06 ± 2.10 × 106; n = 8). The remaining OT-I cells in TG-RIP mice proliferated in vivo after restimulation with antigen, demonstrating that they were not anergic (data not shown). These data strongly suggest that OVA-specific CD8+ T cells were lost and probably deleted once they entered the periphery.

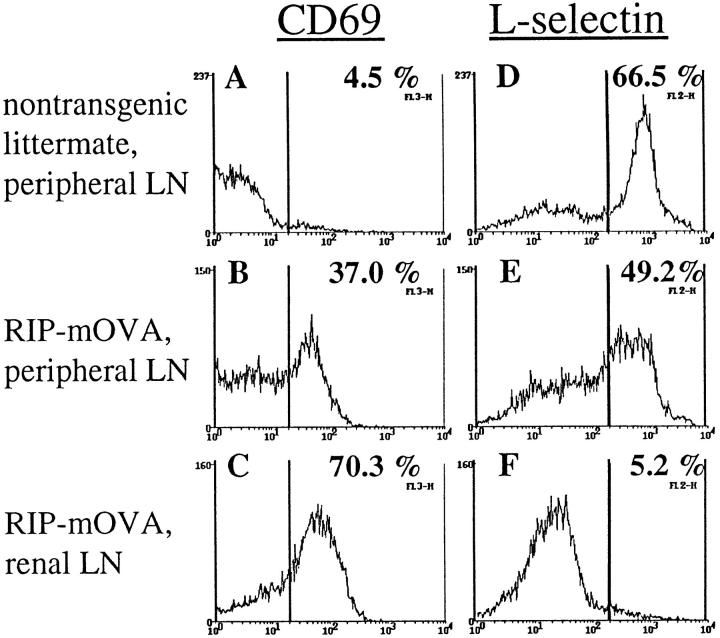

Consistent with an active deletional process occurring in these mice, OT-I cells from the peripheral lymphatic tissues of TG-RIP mice expressed elevated levels of the activation marker CD69 (Fig. 5, A–C) and decreased levels of L-selectin (Fig. 5, D–F) relative to that seen in TG-nontransgenic control mice. The proportion of activated OT-I cells was even higher in the lymph nodes draining OVA-expressing tissues (Fig. 5, C and F), suggesting that activation of OT-I cells in TG-RIP mice also occurred in these draining lymph nodes, presumably by the same cross-presentation mechanism that activates adoptively transferred OT-I cells.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the activation status of OT-I cells in TG-RIP mice. Expression of CD69 (A–C) and L-selectin (D–F) by Vα2+ lymphocytes from the peripheral LN of TG-nontransgenic mice (A and D) and the peripheral (B and E) and renal (C and F) LN of TG-RIP mice.

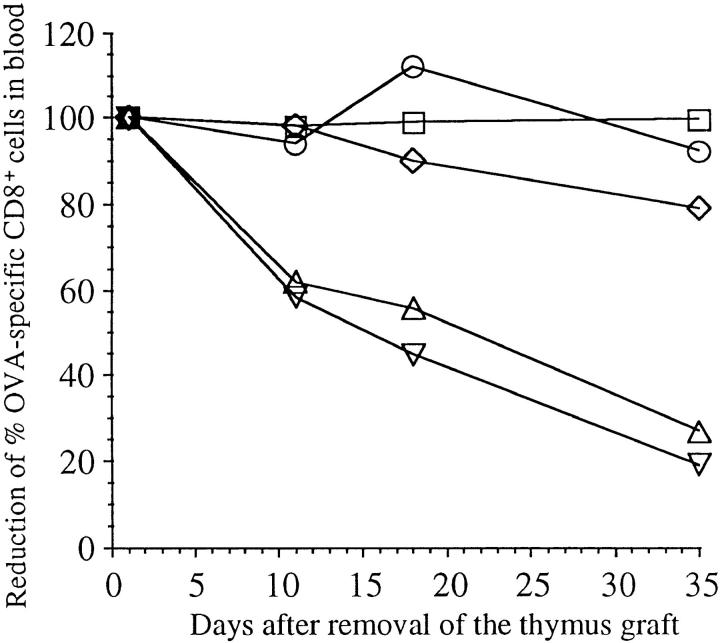

To determine the fate of those few activated OT-I cells remaining in the periphery of TG-RIP mice, the thymus grafts were removed 3 mo after implantation to stop further T cell production. The proportion of OT-I cells was then examined in the blood at various later timepoints. This revealed a continuous decline in the proportion of OT-I cells in TG-RIP mice (Fig. 6), consistent with the idea that a continuous deletion process was in operation. These few remaining cells were also able to proliferate upon restimulation with antigen in vivo (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Disappearance of OT-I cells in TG-RIP mice after removal of their thymus graft. Thymus graft was removed from TG-RIP mice and TG-nontransgenic controls 3 mo after implantation. The proportion of CD8+ peripheral blood cells that were Vα2+Vβ5+ was then determined by flow cytometry on days 2, 11, 18, and 35 after thymectomy. The proportion found at day 2 after removal of the thymus grafts was considered 100% in this particular mouse, and the following values were given as a percent of this starting value. TG-RIP, not operated (○); TG-RIP, thymus graft removed (▿); TG-RIP, thymus graft and left kidney removed (▵); TG-nontransgenic littermate, not operated (□); TG-nontransgenic littermate, thymus graft removed (⋄).

Discussion

There are now numerous reports showing that cross-presentation of exogenous antigen can prime class I–restricted CTL responses (33). It has also been shown to induce tolerance in the thymus (23). Here, we show that cross-presentation can induce peripheral tolerance that appears to operate via a deletional process.

Although our data strongly suggest that OT-I cells were deleted in TG-RIP mice, an alternative possibility is that these cells had relocated to extralymphoid sites. However, because few OT-I cells were seen in nonlymphatic tissues, apart from small numbers of cells in the pancreatic islets (data not shown), this possibility seems remote. It should be emphasized that the mild islet infiltration observed is unlikely to account for the loss of ∼107 cells from the secondary lymphoid organs of the TG-RIP mice.

Deletion has been reported as a likely mechanism of extrathymic tolerance for several introduced antigens, including superantigens (34, 35), viruses (36), soluble peptides (37, 38), and protein (39), and for some self-antigens in transgenic models (8, 14, 16, 40). The general belief is that this form of tolerance results from exhaustive differentiation (34). T cells are stimulated so extensively by antigen that they proceed to end-stage effectors with limited lifespan. Such a mechanism is consistent with the observed activation and proliferation that precedes deletion in the RIP–mOVA model.

Our findings provide a pathway whereby CD8+ T cells can be tolerized to self-antigens expressed in tissues outside the normal recirculation pathway for naive T cells. As long as the antigen can gain access to the exogenous cross-presentation pathway, host CD8+ T cells should be stimulated to die eventually. Thus, as newly derived autoreactive CD8+ T cells enter the peripheral pool, they will encounter their autoantigen on the cross-presenting APC in lymph nodes that drain the appropriate tissues. As a result, activation will follow and lead to deletion, thus limiting the accumulation of ignorant autoreactive cells in secondary lymphoid compartments. This model is at odds with the previously reported induction of diabetes in virus-primed transgenic mice expressing viral antigens in the islet β cells (3, 4), which suggests that ignorant naive CD8+ T cells remained in the peripheral circulation. However, the type and concentration of the antigen and the affinity of the TCR in the responding T cell population are likely to affect the efficacy of cross-presentation leading to deletion. In support of this conclusion, we have preliminary evidence using newly generated transgenic lines that the level of antigen expressed affects the extent of cross-presentation (our unpublished observations). In addition, data obtained using transgenic mice expressing hemagglutinin (HA) under the control of the rat insulin promoter (RIP–HA mice), support the idea that antigens expressed in the islets are not always ignored but can activate CD8+ T cells leading to tolerance induction. RIP–HA mice crossed to TCR transgenic mice, which produced large numbers of class I–restricted HA-specific T cells, became diabetic (41), indicating that HA-specific CD8+ T cells entered the periphery of RIP–HA mice, where they were activated by islet antigens, perhaps by cross-presentation. Despite this observation, RIP–HA single-transgenic mice showed HA-specific CTL tolerance (11), suggesting that the activation process seen in double-transgenic mice may lead to tolerance induction when the precursor frequency is low, as in a normal T cell repertoire.

It is not clear why this form of priming should lead to loss of activated cells when most other described cases of cross-priming result in immunization. Perhaps it relates to the continuous presence of the priming antigen, which provides repeated stimuli to the responding population to the point of exhaustion. Alternatively, because there is specific tolerance to OVA in the CD4+ T cell compartment in our model (our unpublished observations), deletion of CD8+ cells may relate to a lack of CD4+ T cell help, which appears to be necessary for the induction of some CD8+ T cell responses (42–44). Thus, when CD8+ T cells were confronted with antigen in the absence of CD4+ T cells, only a transient response followed after which all the antigen-specific T cells died (45).

Deletion of OT-I cells in TG-RIP mice is consistent with a model in which newly matured OT-I cells enter the periphery of RIP–mOVA mice, recirculate until they come into contact with antigen in the draining lymph nodes of OVA-expressing tissues, and are then activated and deleted. Such activation-induced deletion could occur in one of two ways: either directly as a result of activation on the bone marrow–derived cross-presenting APC, or indirectly because only activated OT-I cells are able to recirculate through nonlymphoid tissues where they can encounter OVA-expressing tissues and there be deleted. The observed deletion of OT-I cells adoptively transferred into B6→ RIP– mOVA.bm1 mice indicates that secondary encounter with antigen on peripheral tissues is not essential for deletion to occur. However, it is important to state that although presentation of OVA on the bone marrow–derived compartment was sufficient to lead to deletion, the additional ability to encounter antigen on peripheral tissue may enhance deletion. This will be examined in future studies.

Our results provide evidence for an extrathymic mechanism capable of inducing the loss of CD8+ T cell responding to self-antigens expressed in tissues outside the lymphoid compartment. Because such tissues are normally not directly accessible to naive CD8+ T cells, the absence of this deletion mechanism would allow accumulation of naive autoreactive CD8+ T cells. These could be primed to effector CTL with wider recirculation pathways after a strong environmental stimulus, thus leading to autoimmunity. We speculate that the continual activation and deletion of small numbers of autoreactive CD8+ T cells by cross-presentation will not result in significant autoimmune damage.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Hodgkin for help with the CFSE labeling technique; J. Falso, T. Banjanin, F. Karamalis, and P. Nathan for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

C. Kurts is supported by a fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Grant Ku1063/1-I). This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant AI-29385 and grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Australian Research Council.

1 Abbreviations used in this paper: HA, hemagglutinin; mOVA, membrane-bound form of ovalbumin; OT-I, OVA-specific CD8+ T cells; RIP, rat insulin promoter; TG, thymus grafted.

References

- 1.Wooley PH, Luthra HS, Stuart JM, David CS. Type II collagen-induced arthritis in mice. I. Major histocompatibility complex (I region) linkage and antibody correlates. J Exp Med. 1981;154:688–700. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.3.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zamvil SS, Steinman L. The T lymphocyte in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:579–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohashi PS, Oehen S, Buerki K, Pircher H, Ohashi CT, Odermatt B, Malissen B, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Ablation of “tolerance” and induction of diabetes by virus infection in viral antigen transgenic mice. Cell. 1991;65:305–317. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90164-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldstone MB, Nerenberg M, Southern P, Price J, Lewicki H. Virus infection triggers insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in a transgenic model: role of anti-self (virus) immune response. Cell. 1991;65:319–331. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90165-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schonrich G, Kalinke U, Momburg F, Malissen M, Schmitt-Verhulst AM, Malissen B, Hammerling GJ, Arnold B. Down-regulation of T cell receptors on self-reactive T cells as a novel mechanism for extrathymic tolerance induction. Cell. 1991;65:293–304. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90163-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schonrich G, Momburg F, Malissen M, Schmitt-Verhulst AM, Malissen B, Hammerling GJ, Arnold B. Distinct mechanisms of extrathymic T cell tolerance due to differential expression of self antigen. Int Immunol. 1992;4:581–590. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schonrich G, Alferink J, Klevenz A, Kublbeck G, Auphan N, Schmitt-Verhulst AM, Hammerling GJ, Arnold B. Tolerance induction as a multi-step process. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:285–293. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fields LE, Loh DY. Organ injury associated with extrathymic induction of immune tolerance in doubly transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5730–5734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heath WR, Allison J, Hoffmann MW, Schonrich G, Hammerling G, Arnold B, Miller JF. Autoimmune diabetes as a consequence of locally produced interleukin-2. Nature (Lond) 1992;359:547–549. doi: 10.1038/359547a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heath WR, Karamalis F, Donoghue J, Miller JF. Autoimmunity caused by ignorant CD8+T cells is transient and depends on avidity. J Immunol. 1995;155:2339–2349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lo D, Freedman J, Hesse S, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL, Sherman LA. Peripheral tolerance to an islet cell– specific hemagglutinin transgene affects both CD4+ and CD8+T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1013–1022. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowell D, Mason D. Evidence that the T cell repertoire of normal rats contains cells with the potential to cause diabetes. Characterization of the CD4+T cell subset that inhibits this autoimmune potential. J Exp Med. 1993;177:627–636. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerder S, Meyerhoff J, Flavell R. The role of the T cell costimulator B7-1 in autoimmunity and the induction and maintenance of tolerance to peripheral antigen. Immunity. 1994;1:155–166. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertolino P, Heath WR, Hardy CL, Morahan G, Miller JF. Peripheral deletion of autoreactive CD8+ T cells in transgenic mice expressing H-2Kbin the liver. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1932–1942. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackay CR. Homing of naive, memory and effector lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:423–427. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferber I, Schonrich G, Schenkel J, Mellor AL, Hammerling GJ, Arnold B. Levels of peripheral T cell tolerance induced by different doses of tolerogen. Science (Wash DC) 1994;263:674–676. doi: 10.1126/science.8303275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Germain RN. MHC-dependent antigen processing and peptide presentation: providing ligands for T lymphocyte activation. Cell. 1994;76:287–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bevan MJ. Antigen presentation to cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;182:639–641. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rock KL. A new foreign policy: MHC class I molecules monitor the outside world. Immunol Today. 1996;17:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bevan MJ. Cross-priming for a secondary cytotoxic response to minor H antigens with H-2 congenic cells which do not cross-react in the cytotoxic assay. J Exp Med. 1976;143:1283–1288. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.5.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon RD, Mathieson BJ, Samelson LE, Boyse EA, Simpson E. The effect of allogeneic presensitization on H-Y graft survival and in vitro cell-mediated responses to H-y antigen. J Exp Med. 1976;144:810–820. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.3.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gooding LR, Edwards CB. H-2 antigen requirements in the in vitro induction of SV40-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1980;124:1258–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Boehmer H, Hafen K. Minor but not major histocompatibility antigens of thymus epithelium tolerize precursors of cytolytic T cells. Nature (Lond) 1986;320:626–628. doi: 10.1038/320626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carbone FR, Bevan MJ. Class I–restricted processing and presentation of exogenous cell-associated antigen in vivo. J Exp Med. 1990;171:377–387. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang AY, Golumbek P, Ahmadzadeh M, Jaffee E, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. Role of bone marrow–derived cells in presenting MHC class I–restricted tumor antigens. Science (Wash DC) 1994;264:961–965. doi: 10.1126/science.7513904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnold D, Faath S, Rammensee H, Schild H. Cross-priming of minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells upon immunization with the heat shock protein gp96. J Exp Med. 1995;182:885–889. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurts C, Heath WR, Carbone FR, Allison J, Miller JFAP, Kosaka H. Constitutive class I–restricted exogenous presentation of self antigens in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;184:923–930. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 1994;76:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyons AB, Parish CR. Determination of lymphocyte division by flow cytometry. J Immunol Meth. 1994;171:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodgkin PD, Lee JH, Lyons AB. B cell differentiation and isotype switching is related to division cycle number. J Exp Med. 1996;184:277–281. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fulcher DA, Lyons AB, Korn SL, Cook MC, Koleda C, Parish C, Fazekas de St B, Groth, Basten A. The fate of self-reactive B cells depends primarily on the degree of antigen receptor engagement and availability of T cell help. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2313–2328. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikolic-Zugic J, Bevan MJ. Role of self-peptides in positively selecting the T-cell repertoire. Nature (Lond) 1990;344:65–67. doi: 10.1038/344065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jondel M, Schirmbeck R, Reimann J. MHC class I–restricted CTL responses to exogenous antigens. Immunity. 1996;5:295–302. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Webb S, Morris C, Sprent J. Extrathymic tolerance of mature T cells: clonal elimination as a consequence of immunity. Cell. 1990;63:1249–1256. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90420-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones LA, Chin LT, Longo DL, Kruisbeek AM. Peripheral clonal elimination of functional T cells. Science (Wash DC) 1990;250:1726–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.2125368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moskophidis D, Lechner F, Pircher H, Zinkernagel RM. Virus persistence in acutely infected immunocompetent mice by exhaustion of antiviral cytotoxic effector T cells (see erratum Nature (Lond.).1993. 364:262) Nature (Lond) 1993;362:758–761. doi: 10.1038/362758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kyburz D, Aichele P, Speiser DE, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM, Pircher H. T cell immunity after a viral infection versus T cell tolerance induced by soluble viral peptides. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1956–1962. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mamalaki C, Tanaka Y, Corbella P, Chandler P, Simpson E, Kioussis D. T cell deletion follows chronic antigen specific T cell activation in vivo. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1285–1292. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.10.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Critchfield JM, Racke MK, Zuniga PJ, Cannella B, Raine CS, Goverman J, Lenardo MJ. T cell deletion in high antigen dose therapy of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science (Wash DC) 1994;263:1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.7509084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forster I, Hirose R, Arbeit JM, Clausen BE, Hanahan D. Limited capacity for tolerization of CD4+T cells specific for a pancreatic beta cell neo-antigen. Immunity. 1995;2:573–585. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan DJ, Liblau R, Scott B, Fleck S, McDevitt HO, Sarvetnick N, Lo D, Sherman LA. CD8(+)T cell– mediated spontaneous diabetes in neonatal mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:978–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Husmann LA, Bevan MJ. Cooperation between helper T cells and cytotoxic T lymphocyte precursors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1988;532:158–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb36335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guerder S, Matzinger P. A fail-safe mechanism for maintaining self-tolerance. J Exp Med. 1992;176:553–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krieger NR, Yin DP, Fathman CG. CD4+ but not CD8+cells are essential for allorejection. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2013–2018. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirberg J, Bruno L, von Boehmer H. CD4+8− help prevents rapid deletion of CD8+cells after a transient response to antigen. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1963–1967. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]