Abstract

Salmonella typhimurium is considered a facultative intracellular pathogen, but its intracellular location in vivo has not been demonstrated conclusively. Here we describe the development of a new method to study the course of the histopathological processes associated with murine salmonellosis using confocal laser scanning microscopy of immunostained sections of mouse liver. Confocal microscopy of 30-μm-thick sections was used to detect bacteria after injection of ∼100 CFU of S. typhimurium SL1344 intravenously into BALB/c mice, allowing salmonellosis to be studied in the murine model using more realistic small infectious doses. The appearance of bacteria in the mouse liver coincided in time and location with the infiltration of neutrophils in inflammatory foci. At later stages of disease the bacteria colocalized with macrophages and resided intracellularly inside these macrophages. Bacteria were cytotoxic for phagocytic cells, and apoptotic nuclei were detected immunofluorescently, whether phagocytes harbored intracellular bacteria or not. These data argue that Salmonella resides intracellularly inside macrophages in the liver and triggers cell death of phagocytes, processes which are involved in disease. This method is also applicable to other virulence models to examine infections at a cellular and subcellular level in vivo.

Murine salmonellosis has been used for decades as a model system for human typhoid fever because Salmonella typhimurium develop a systemic infection in mice reminiscent of human typhoid (1–3). The ability of S. typhimurium to successfully colonize and ultimately cause disease in susceptible mice is ascribed to numerous bacterial gene products essential for pathogenesis. Mutants of S. typhimurium have been characterized in vitro, and genes important for the entry process and intracellular survival in tissue culture cells have been identified (4, 5) and tested for virulence in the murine typhoid model. The involvement of these gene products in virulence is based on LD50 determinations and infection kinetics of organs such as liver and spleen, but the actual role these factors play in disease has not been examined due to the lack of appropriate methods to study host pathogen interactions in vivo. Tissue culture experiments showed that S. typhimurium is able to survive intracellularly in macrophages, suggesting that survival within host cells is an essential feature for S. typhimurium virulence. This is important for disease, since mutants which fail to do so are avirulent in the mouse model (6). However, evidence to support macrophages as the host cell in vivo is still indirect, and conflicting data exist regarding the location of S. typhimurium in the mouse, ranging from inside neutrophils (7), macrophages (8, 9), and hepatocytes (10, 11) to the extracellular space (12). In studies using light and electron microscopy, artificially high inoculums were used to visualize bacteria in the organs. Large doses of bacteria might trigger a septic shock response in the mouse which could further complicate the results.

Here, we use confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM)1 (13) and computerized image analysis techniques with immunostained sections of liver as a tool to extend the knowledge gained from in vitro studies to the in vivo situation. Unlike conventional microscopy, this method allowed us to infect mice with small infectious doses of S. typhimurium (100 CFU), to examine early time points in the infection, and to focus on a single bacterium in a large tissue area. The relative ease of detection of bacteria is facilitated by the use of thick sections (30 μm), which is 7–30 times the thickness used in conventional immunohistochemistry (1–4 μm) and 300–600 times that used in electron microscopy (50– 100 nm). Using this technology, we addressed the issue of Salmonella targeting in vivo. By using antibodies directed against different host cell types, we identified which cells Salmonella infects and whether bacteria are located inside host cells. This study demonstrates that confocal microscopy is a suitable technology to study Salmonella pathogenesis in vivo. Furthermore, this approach can be easily applied to other infection models of other pathogens in different tissues.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Condition.

S. typhimurium strain SL1344 (14) is a highly virulent strain of Salmonella with an LD50 <10 CFU when administered intraperitoneally or intravenously to susceptible BALB/c mice (reference 15 and Richter-Dahlfors, A., unpublished observation). SL1344 was grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C in standing overnight cultures. 1 ml of the bacterial culture was centrifuged and resuspended in 1 ml cold PBS. The OD600 was adjusted to 0.2 using cold PBS. From this suspension, a dilution series was made in cold PBS to yield ∼103, 104, and 105 CFU/ml. The mice were immediately infected with 0.1 ml of the diluted cell suspensions. To determine the exact number of live bacteria in the inoculums used to challenge the mice, 0.1 ml of the dilutions was plated on Luria-Bertani plates, incubated overnight at 37°C, and the colonies were counted. The size of the inoculum varied between 0.65–1.15 × 102 CFU, 0.87– 1.15 × 103 CFU, and 0.87–1.15 × 104 CFU, respectively.

Infection Kinetics and Preparation of Thick Cryosections of S. typhimurium–infected Mouse Liver.

Female BALB/c mice (Charles River Canada, St.-Constant, Quebec, Canada) 6–10 wk of age were used throughout the study. A minimum of four mice per dose and time point were challenged with 0.1 ml of the bacterial dilutions via intravenous injection in the tail vein. At different times after infection (days 1, 2, 3, and 5), the mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation in accordance to the policies of the protocol from the Canadian Council of Animal Care and the University of British Columbia. The livers and spleens were aseptically removed and prepared for infection kinetics determination (15) and immunohistochemistry. Livers were fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (BDH Chemicals Ltd., Poole, UK) in PBS, pH 7.4, for 1 h in room temperature, then washed three times in PBS followed by cryoprotection in 20% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4°C. Pieces of the organs were mounted in OCT Tissuetek (Miles Laboratories Inc., Elkhart, IN), then snap-frozen in cold (−50 to −60°C) 3-methyl-butane (Fisher Scientific Co., Pittsburgh, PA). The livers were cut in 30-μm sections on a cryostat. The sections were kept floating in PBS + 0.05% sodium-azide (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 4°C until analyzed.

Immunohistochemistry of Thick Cryosections.

Sections were incubated in 10% normal goat serum (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) in PBS for 10 min before immunostaining. The antibodies used were prepared in 0.2% saponin (Calbiochem Corp., San Diego, CA), 10% normal goat serum in PBS, pH 7.4, and the sections were incubated floating in 200 μl primary antibody solution per well in 48-wells plates overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed three times in PBS before and after 1 h of incubation in the secondary antibody mix. In the triple labeling experiments, which included the FITC-tagged antineutrophil antibody, the tissues were incubated in a mix containing the two unlabeled primary antibodies, washed, and incubated in the secondary antibodies as described, followed by an additional overnight incubation in the FITC-tagged antibody mix. Sections were washed and mounted directly onto coverslips (22 × 22 mm, 1 mm thickness) in a drop of PBS. Excess fluid was removed from the coverslip, and the tissue was covered with a minimal amount of mounting media (9 mM p-phenylenediamine [BDH Chemicals Ltd.] in 90% glycerol + 10% PBS, pH 8.8). Coverslips were inverted on a precleaned glass slide, and sealed with nail polish. The primary antibodies used in this study were: anti-Salmonella, Salmonella O Antiserum Group B Factors 1,4,5,12 (Difco Laboratories Inc., Detroit, MI), used at a dilution of 1:500; Texas Red (TxR)- phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), dilution of 1:50; antileukocytes, CD18 (clone M18/2.a.12.7) and antihepatocytes, TROMA-1 (the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD), dilution of 1:50; anti-Kupffer cells, MOMA-1 (Serotec Ltd., Kidlington, Oxford, UK), dilution of 1:25; anti–T lymphocytes, CD4 (GK1.5) and CD8 (53-6.72) (gift from Dr. I. Haidl, Biotechnology Lab, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), dilution of 1:10; anti–B cells, CD45R/B220 (RA3-6.B2) (gift from Dr. I. Haidl), dilution of 1:10; and antineutrophils, RB6-8C5 (Ly-6G) conjugated to FITC (PharMingen, San Diego, CA), dilution of 1:100. Secondary antibodies used were goat anti–rabbit-Cy2 (Amersham International, Little Chalfont, UK), dilution of 1:500; donkey anti–rat-Cy3, donkey anti– rabbit-Cy3, and donkey anti–rat-Cy5 (Jackson Immunoresearch Labs., West Grove, PA), dilution of 1:500; goat anti–rabbit-TxR (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs.), dilution of 1:50; and goat anti–rabbit-FITC (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs.), dilution of 1:50.

Detection of Apoptotic Cells in Sections of Mouse Liver.

Apoptotic cells in the liver sections were detected using the ApopTag in situ apoptosis detection kit (Oncor Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Briefly, the 3′-OH DNA ends generated by DNA fragmentation in apoptotic nuclei were catalytically extended with residues of digoxigenin-nucleotides using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. After an incubation with an FITC-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody, the apoptotic cells could be visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

Liver sections of 30 μm in thickness were post-fixed floating in ethanol/acetic acid (2:1) for 7 min at −20°C. After a wash in PBS, the apoptotic nuclei were labeled according to the manufacturer's protocol. Thereafter, the sections were labeled with different antibodies as described above.

CLSM and Image Analysis.

The images were collected on a Nikon Optiphot-2 Research Microscope attached to a confocal laser scanning microscope (MRC-600; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using COMOS software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The laser lines on the krypton/argon laser were 488 nm (FITC and Cy2), 568 nm (TxR and Cy3), and 647 nm (Cy5). Filterblock BHS was used to detect FITC and Cy2 (488 nm excitation, 515 nm emission), YHS was used to detect TxR and Cy3 (568 nm excitation, 585 nm emission), and RHS was used to detect Cy5 (647 nm excitation, 680 nm emission). The numerical aperture was 0.75 on the ×20 air objective and 1.4 on the ×60 oil objective. The images were captured such that the xyz dimensions were 0.4 μm cubed (×20) and 0.2 μm cubed (×60). NIH Image version 1.60 was used for image analysis, and all images were based on maximum intensity projection. The Bob component of the GVLware package (University of Minnesota, http://s1.arc.umn.edu/html/ gvl-software/gvl-software.html) was used when the data were analyzed using the volume rendering technique. Projections made in NIH Image were saved in TIFF format, then imported to Adobe Photoshop version 3.0.4 where the different fluorophore images were assigned to individual RGB channels and subsequently merged to provide the final image of the single or multiple immunostained sections.

Results

Development of a Method to study Murine Salmonella Infection Under Conditions Which More Closely Mimic a Natural Infection.

Naturally acquired systemic Salmonella infections presumably begin by the entry of a few bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract into tissues via systemic circulation (16). We developed a method to visualize bacteria in the liver at early times when the mouse was infected intravenously with only a few bacteria (∼100 CFU). 30-μm-thick sections of mouse liver were immunostained with primary antibodies which were localized by either direct or indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. The labeled sections were analyzed using epifluorescence and CLSM. One advantage of CLSM is the ability to use triple labelings of specimens with antibodies recognizing bacteria and different cell markers in the mouse liver. Furthermore, digitized images can subsequently be analyzed using image analysis software, and it is possible to study sub-volumes of the collected data set to create a three-dimensional image.

We chose the intravenous route of infection, as it is the most reproducible method of infection using small numbers of bacteria. Mice were killed at different times after infection and the livers were fixed and prepared for cryosectioning. Permeabilization of a thick section is essential to provide a homogenous labeling by antibodies throughout the entire tissue section. We found that 0.2% saponin in the antibody mix allowed full penetration of the section by antibodies, as did a post-fixation in cold ethanol/acetic acid before incubation with the antibody mix. To further improve the antibody labeling reaction, floating sections were incubated in 200 μl of antibody solution per well in a 48-well plate, which allowed the penetration of antibodies from both sides of the sections.

The thick sections had a relatively high background fluorescence due in part to the presence of autofluorescent substances in the liver (17). To provide a high signal to noise ratio, the cyanine fluorophores Cy2, Cy3, and Cy5 were chosen for the CLSM work. In addition to increased brightness the cyanine dyes are less sensitive to photobleaching (18). However, bacteria and apoptotic nuclei were readily detectable with TxR or FITC fluorophores. To further increase the signal to noise ratio, we found that a longer incubation time (∼15 h, 4°C) in a diluted primary antibody mix was preferable to a shorter time in a more concentrated antibody solution. The incubation time in the secondary antibody solutions was 1 h.

Characteristics of Primary Lesions in Mice Infected with Virulent S. typhimurium.

After an intravenous challenge of BALB/c mice with a dose of ∼100 virulent S. typhimurium strain SL1344, mice were killed at daily intervals. The liver and spleen are the two main sites for Salmonella proliferation in the host (19), and infection kinetic experiments showed a rapid increase of bacterial numbers in both these organs until death occurred at days 6–7 (Fig. 1). Postmortem examination at days 1, 2, and 3 revealed no macroscopic changes in the various organs of the reticuloendothelial system. However, at day 5 both the liver and spleen were grossly enlarged and swollen (hepatosplenomegaly), and numerous gray-white lesions were visible on both organs. Hypertrophy of the liver was accompanied by derangement of the liver parenchyma.

Figure 1.

Infection kinetics. Numbers of bacteria recovered from homogenized liver (white) and spleen (black) at different days after infection following an intravenous dose of 115 CFU SL 1344. The mice died at days 6–7. The data represent the average number of bacteria recovered from the organs of four mice per time point, and the error bars indicate the standard deviation.

Projections of 1.2-μm z-stacks collected on the confocal microscope demonstrate the changes in morphology which the liver undergoes during infection (Fig. 2). TxR-phalloidin was used to label the actin filaments in liver sections from controls and at different stages of infection (20). In the uninfected liver (Fig. 2 a) the intact polyhedral hepatocyte structure is apparent, showing the plates of hepatocytes separated by the sinusoids. The bile canaliculi are outlined as bright dots between adjacent hepatocytes due to the accumulation of actin in the cell-to-cell junctions. Similar results were seen at days 1 and 2 after infection. At day 3, although the mice did not show any symptoms of disease and hepatosplenomegaly had not yet occurred, morphological changes were observed. In some areas, the plates of hepatocytes were no longer intact due to the massive infiltration of phagocytes. One of these inflammatory foci is shown in Fig. 2 b. The structural disintegration of the hepatocytes was more pronounced at a late stage (day 5) of infection (Fig. 2 c). At this phase of infection, the mice were very sick and hepatosplenomegaly was apparent. The morphological changes of the hepatocytes were also observed when staining with TROMA-1, an antibody which specifically recognizes cytokeratin Endo-A present in the cell borders of the hepatocytes (21).

Disruption of the hepatic cells correlated with infiltration by leukocytes in the liver as the bacterial infection progressed. A general marker for the leukocyte population is CD18 (integrin β2 chain) (22). This marker was used to examine the time-dependent infiltration of the liver by leukocytes. Fig. 3, a–c are projections of 8-μm z-stacks showing the result of a triple labeling experiment of liver sections at different times after infection using CD18-Cy5 (pink), TxR-phalloidin (purple), and anti-Salmonella–FITC (green/yellow). The uninfected liver (Fig. 3 a) contains resident macrophages, the Kupffer cells. With a low infective dose, foci of CD18-positive cells appeared at day 3 (Fig. 3 b). The foci grew rapidly, becoming larger and more numerous at day 5 (Fig. 3 c). These areas of parenchymal necrosis appeared at any site in the hepatic lobule. It has been suggested that necrotic foci of the hepatocytes are caused by occlusion of the vascular sinusoids by masses of infiltrating mononuclear cells which may cut off the blood supply (19). Indeed, we observed infiltration by numerous leukocytes in the infected liver, not only in the foci but also the interstitial spaces (Fig. 3 c). Furthermore, some of the hepatic blood vessels (portal and central veins as well as sinusoids) contained masses of inflammatory CD18-positive cells which correlates with the observation that acute inflammation of the blood vessels causes thrombosis and infarcts (23).

When an inflammatory response is triggered, neutrophils rapidly extravasate from the vasculature into the tissue and accumulate at the infectious foci (23, 24). It is not until the infection has progressed to later stages that the mononuclear cells begin to appear while the neutrophils disintegrate at the center of the lesions. The antibody RB6-8C5 recognizes a differentiation antigen specific for neutrophils (25) and has been used extensively in vivo to deplete mice of this cell type (24, 26–29). We used the FITC-tagged antibody RB6-8C5 (blue) in a triple labeling experiment together with CD18-Cy5 (red) and anti-Salmonella–TxR (green) to differentiate the neutrophils from the total leukocytes (CD18-positive) present at different times after infection. Fig. 4 a shows that there is an absence of neutrophils in the uninfected liver which contains resident macrophages (Kupffer cells) (red). Similar results were obtained at day 1 after infection. A few neutrophils were occasionally found in veins at day 2, but the liver parenchyma otherwise looked normal. At day 3 a marked infiltration of neutrophils into the tissue occurred and most of the CD18-positive foci consisted of centrally located neutrophils (Fig. 4 b). However, in some foci the neutrophils had already disintegrated and were replaced by mononuclear cells. By day 5, infiltration of mononuclear phagocytes into the lesions and disappearance of the neutrophils was complete, as all necrotic foci had transformed into granulomas (Fig. 4 c).

Figure 4.

Neutrophils are present in the foci at an early stage of infection, while macrophages dominate the tissue at later stages. Mouse liver sections labeled with antineutrophil-FITC (purple), CD18-Cy5 (red), and anti-Salmonella–TxR (green/light blue/yellow) in (a) uninfected liver, (b) liver infected with 65 CFU SL1344 at day 3 after infection, and (c) the same dose at day 5 after infection showing that neutrophils extravasate into the liver as an early response, but disappear at a later stage of infection when the foci consists of macrophages. The bacteria colocalize to the phagocytes, not to the hepatocytes. Each image is a projection of an 8-μm z-stack collected through the ×20 objective on a Bio-Rad MRC-600 confocal microscope. Bar, 50 μm.

The mononuclear cells which constituted the granulomas contained predominately incoming phagocytes, not resident Kupffer cells. MOMA-1 is an antibody which reacts with a subpopulation of mature resident tissue macrophages. In the liver, this antibody specifically labels the Kupffer cells (30). However, in infected mice, the Kupffer cells were always interstitial and only accumulated at the periphery of the foci regardless of the stage of infection (data not shown).

We also looked for possible changes in the numbers of T and B lymphocytes in the mouse liver due to Salmonella infection. To this end, we used the antibodies GK1.5 (T helper) (31), 53-6.72 (T killer and a subset of NK cells) (32), and RA3-6.B2 (B cells) (33). We did not notice any increase in the number of T lymphocytes, while B cells were slightly increased (approximately threefold) at the later stages of infection. These results are not surprising, since the time frame of a Salmonella infection is too short for the host to mount a humoral or T cell–mediated immune response. Furthermore, these data clearly show that the key cells involved in the host defense against a Salmonella infection are the neutrophils and macrophages.

S. typhimurium Colocalizes to the Neutrophils and Macrophages in the Mouse Liver.

The primary lesions of S. typhimurium infection in mice have been well documented by conventional histological methods, and it was encouraging to find that our method reflected the sequential development of the histopathological processes described earlier (1, 19, 23). The advantage of our method was that we were able to locate the bacteria in the liver sections by adding a third, anti-Salmonella, antibody. In no other report has the location of the bacteria in the tissue been visualized with a dose <106 CFU injected either intravenously or intraperitoneally (10, 11, 24, 34–38). This is due to the limitations of the methods previously used (electron microscopy and light microscopy) in which only minute areas of the liver were studied, and accordingly, very high doses of bacteria were needed for visualization. Only one other report has used a similar low dose of bacteria, and although the histopathological lesions they describe were the same as those we report, they could not detect the bacteria, except from blood cultures (23).

The site where Salmonella resides and proliferates in vivo has been disputed and, depending on the methodology used, hepatocytes (10, 11), macrophages (Kupffer cells) (8, 9), neutrophils (7), as well as the extracellular space (12), have all been suggested as permissible compartments in the liver. These discrepancies might in part be explained by the overwhelming doses of bacteria used to infect the animal in these studies. Using our methodology, it was possible to detect a single bacterium in the liver when a low infective dose was administered, and thus we addressed the question as to where Salmonella resides in vivo.

When a small inoculum (65 CFU) of bacteria was injected intravenously, the bacteria could not be detected visually at days 1 or 2 after infection in thick sections, but from day 3 the bacteria were routinely visualized (Fig. 3 b). At this stage of infection the liver contained only 6.2 × 104 CFU bacteria (Fig. 1). The bacteria (green) were mainly restricted to the foci where they colocalized with the leukocyte marker CD18 (Fig. 3 b and 4 b). Occasionally, bacteria were found in other areas than the foci, but they always colocalized to CD18-positive cells. When the disease progressed to day 5, the bacteria were present not only in the foci, but had disseminated to interstitial areas as well (Fig. 3 c and 4 c), although they remained colocalized to CD18-positive cells which at this stage were mononuclear cells (predominantly infiltrating macrophages).

In an attempt to quantitate colocalization of the bacteria to the leukocytes, a ×60 objective on an epifluorescent microscope was used in a double labeling experiment to identify individual bacteria (anti-Salmonella–Cy2) and measure their colocalization to CD18-positive cells (CD18-Cy3) by focusing through 30-μm-thick sections. Table 1 shows that at days 3 and 5, 98 and 93% of the bacteria were colocalized to leukocytes, respectively. This is probably an underestimation, since it was sometimes difficult to outline the protrusions of the leukocytes and accordingly determine whether the bacteria colocalized or not.

Table 1.

Colocalization of S. typhimurium and Digoxigenin-labeled Nuclei to CD18-positive Cells in the Mouse Liver at Different Times After Infection

| Dose and days after infection | Percentage of colocalization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL1344/CD18 | ApopTag/CD18 | |||

| Uninfected | 0 | 24.3 ± 3.5 | ||

| 102 CFU, day 1 | 0 | 22.0 ± 3.6 | ||

| 102 CFU, day 2 | 0 | 68.6 ± 9.0 | ||

| 102 CFU, day 3 | 98.2 ± 1.3 | 89.5 ± 2.2 | ||

| 102 CFU, day 5 | 93.0 ± 2.7 | 96.4 ± 2.9 | ||

The numbers represent percentage of colocalization of the different markers±standard deviation from three separate experiments counting 100 bacteria or apoptotic nuclei per experiment.

We also performed experiments in which 10 and 100 times higher doses of S. typhimurium SL1344 were injected. By increasing the dose it was possible to detect the bacteria at earlier time points. When 104 CFU were used, the bacteria were routinely detected at day 1, and with 103 CFU, bacteria were visualized in the liver at day 2 after infection. In both cases, the presence of bacteria coincided with the infiltration of leukocytes into the tissue. Similar morphological changes were observed in the liver when comparing the effect of high and low doses. However, the disease progressed faster with high infective doses, and the mice died at days 3–4 and 5–6, respectively. We did not notice any difference in the frequency of bacterial colocalization to leukocytes at earlier time points, suggesting that S. typhimurium is mainly associated with the neutrophils and the macrophages during the typhoid-like Salmonella infection in mice.

S. typhimurium Resides Intracellularly in Macrophages of the Mouse Liver.

Because several studies have shown that Salmonella are able to invade and multiply in cultured macrophages, and many genes specific for macrophage survival in vitro have been isolated, it is a commonly held view that S. typhimurium survives intracellularly in macrophages as part of its pathogenesis (6, 39–44). However, evidence to support this concept is indirect, and the classification of S. typhimurium as a facultative intracellular pathogen has also been questioned (12).

Using sub-volumes of a z-stack collected on a confocal microscope, we found that S. typhimurium resides intracellularly in mononuclear cells at late stages of infection. Fig. 5 a is a projection of a 30-μm z-stack collected through the ×60 objective on the CLSM showing a mouse liver infected with 65 CFU SL1344 at day 5 after infection. The Salmonella (orange) colocalized to the macrophages (green) labeled with CD18-Cy5 (neutrophils are not present at this stage of infection). To verify that the bacteria were located intracellularly and not in a focal plane different from the macrophage, we used two different image analysis techniques. The boxed macrophage in Fig. 5 a was cropped and analyzed using the maximum intensity projection in NIH Image. The xy view in Fig. 5 b shows the same macrophage as outlined in Fig. 5 a. Using NIH Image, we resliced the stack vertically and horizontally to obtain the projections of the side view (yz) and the bottom view (xz). When combining the projections shown in Fig. 5 b it was apparent that all five bacteria reside inside the macrophage. We also analyzed the data using a volume rendering program to rule out surface localized bacteria. The reconstituted surface of the macrophage is shown in a three-dimensional view in Fig. 5 c. Note that there are no bacteria located on the outside surface. Instead, the bacteria are inside the macrophage, as shown by a cross-section of the image (Fig. 5 d). Within the sub-volume, represented by a tilted, 1.8-μm section of the original 30-μm stack, three out of the five bacteria present in this macrophage were visible. The remaining two bacteria were also intracellularly located but in a different section of the macrophage (not shown).

Figure 5.

S. typhimurium are located inside macrophages at late stages of infection. (a) Mouse liver infected with 65 CFU SL1344 at day 5 after infection labeled with anti-Salmonella–Cy3 (orange) and CD18-Cy5 (green). The image is a projection of a 30-μm z-stack collected through the ×60 objective on a Bio-Rad MRC-600 confocal microscope. The boxed macrophage is analyzed further in b–d. Bar, 25 μm. (b) NIH Image was used to project the side view (yz) and the bottom view (xz) of the boxed macrophage (represented by the xy view), which together demonstrate the intracellular location of the bacteria. (c) A three-dimensional reconstitution of a liver macrophage at day 5 after infection (the same cell as in b) using volume rendering. (d) A tilted, 1.8-μm section of the macrophage in c shows the intracellular location of three bacteria (red). Other bacteria present in b were also intracellularly located, but in a different section of the macrophage.

To determine the frequency with which the bacteria are located inside macrophages, 50 randomly chosen areas containing either single or clusters of bacteria were analyzed as above. The Cy5 fluorophore, which can only be detected on the confocal microscope and not by the human eye, was used to detect the CD18-positive cells, thereby assuring a nonbiased analysis. Of 50 areas studied, 44 (88%) showed an intracellular location while 6 were either extracellular or unclear. These numbers clearly suggest that most of the bacteria are intracellularly located in macrophages at late stages of infection.

S. typhimurium Induce Cell Death in Mouse Liver Neutrophils and Macrophages.

Although macrophages are known to mediate host defense responses against foreign microorganisms (45), our study suggested that in vivo the environment in which S. typhimurium is found is inside macrophages. In recent years several microorganisms have been shown to induce apoptosis in their host cells as part of their infectious process, probably as a mechanism to counteract host immune defense mechanisms or to promote host-cell proliferation, thereby securing a niche for bacterial proliferation (46). Very recently S. typhimurium was reported to be cytotoxic and to induce apoptosis in cultured and bone marrow–derived macrophages (47, 48). We thus investigated the role of cell death and apoptosis in vivo.

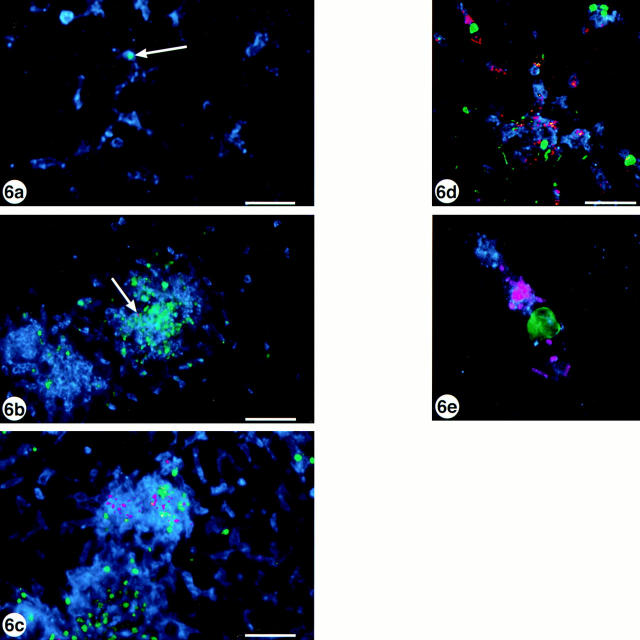

The method we used for microscopical detection of apoptosis in situ was based on detection of DNA fragments produced as a result of apoptotic activation of intracellular endonucleases (49). In addition to the FITC-labeling of apoptotic nuclei we labeled the same 30-μm liver sections with anti-Salmonella–TxR and CD18-Cy5 for further analysis using CLSM. Only occasionally could a positive cell be detected in the uninfected liver, otherwise the parenchyma was devoid of apoptotic nuclei (Fig. 6 a). After the injection of a low dose of SL1344, apoptotic nuclei started to appear en masse by day 3 after infection (Fig. 6 b) and increased further by day 5 (Fig. 6 c). Noteworthy was that the appearance of apoptotic nuclei coincided both in time and location with the infiltrating phagocytes, since tissues from days 1 and 2 were indistinguishable from control tissue, but from day 3 the FITC-labeled nuclei colocalized to the infectious foci. Data from colocalization experiments are presented in Table 1, showing that it is predominantly (89– 96%) the CD18-positive cells that undergo cell death and not hepatocytes. Using the ×60 objective on the confocal microscope, we found that the apoptotic macrophages sometimes harbored intracellular Salmonella, but uninfected cells also underwent apoptosis (Fig. 6 d). Fig. 6 e shows a single apoptotic macrophage (CD18-positive cell at late stage of infection) with intracellular bacteria. Based on the data presented in Fig. 6 we conclude that S. typhimurium infection exerts a cytotoxic effect, either direct or indirect, on the infiltrating phagocytes.

Figure 6.

S. typhimurium are cytotoxic for mouse liver phagocytes. Mouse liver sections labeled with anti-digoxigenin-FITC (green), anti- Salmonella–TxR (pink), and CD18-Cy5 (blue) in (a) uninfected liver, (b) liver infected with 65 CFU SL1344 at day 3 after infection, and (c) the same dose at day 5 after infection. The FITC labeling shows the cytotoxic effect of the bacteria on the phagocytes, while a single apoptotic cell in the uninfected tissue is indicated by the arrow in a. The images are projections of 8-μm z-stacks collected through the ×20 objective. Bar, 50 μm. (d) The same tissue and labeling as in c but the image is a projection of a 32-μm z-stack collected through the ×60 objective. Bar, 25 μm. (e) As d but focused on a single apoptotic cell with intracellular bacteria. Images in a–c were collected on a Bio-Rad MRC-600 confocal microscope, d–e were collected on a Bio-Rad 1024 confocal microscope.

Discussion

We describe here a novel method to study different aspects of Salmonella pathogenesis in vivo at a cellular level. The method is based on CLSM of immunostained objects in 30-μm cryosections of the mouse liver. The aim was to visualize bacteria in mouse liver when very low infective doses were administered (∼100 CFU). This was an attempt to mimic naturally acquired Salmonella infections where only a few of the orally ingested bacteria cross the epithelial lining of the small intestine, reach the blood stream, and disseminate further into the reticuloendothelial system of the host to cause disease (16). The high reproducibility of the intravenous injection route made this the technique of choice since very low numbers of bacteria were used as inoculums. Challenge via the oral and intraperitoneal routes of infection has been shown to cause similar histopathological changes in mouse liver (1).

Murine salmonellosis in susceptible mice is marked by a rapidly progressing systemic disease with an inevitably fatal outcome. We studied the histopathological development of lesions in the mouse liver after an intravenous injection of ∼100 CFU of S. typhimurium and confirmed most of the pathology already described for this disease (1, 8, 19, 23), indicating that this approach was appropriate. The initial lesions appeared at day 3 after infection when masses of infiltrating neutrophils accumulated in well defined necrotic foci in an otherwise unaffected liver parenchyma. During the following days, the number and size of these lesions increased. Macrophages began to appear in the periphery of the lesions, replacing the neutrophils. Neutrophils disappeared by day 5, and the lesions were granulomas. During the late stage of infection the macrophages were not only present in the foci, but also in large numbers in the interstitial area of the parenchyma causing leucostasis of the liver. Despite the massive influx of mononuclear cells into the infected organs, the course of the disease was fatal and the mice died at days 6–7.

The site of Salmonella proliferation in the mouse is a contentious issue addressed by several investigators over the years using high infectious doses (10, 11, 24, 34–38). There is a serious concern that the effects seen when a dose 2 × 105 times higher than the LD50 dose of a virulent bacteria is administered intraperitoneally to susceptible mice reflect those of a naturally occurring infection (10). Artifacts caused by a septic shock response due to the high levels of LPS and toxic cell wall components in the circulation may further complicate the results. Using confocal microscopy of immunostained thick sections of the mouse liver, we directly visualized the bacteria in the mouse liver after a dose of 65 CFU administered intravenously. At day 3 after infection, the bacteria appeared in the inflammatory foci and colocalized to the neutrophils and macrophages. As the disease progressed the number of bacteria in the tissue increased and by later stages of the infection (day 5) numerous bacteria appeared in the foci as well as in the interstitial areas, but remained colocalized with the macrophages. When higher doses were used to challenge the mice, we found that >95% of the bacteria colocalized to the neutrophils and macrophages at any time point examined. These results argue in favor of the neutrophils/macrophages as being the main site for Salmonella proliferation in the mouse.

The ability of Salmonella to survive after phagocytosis by macrophages has been shown in several tissue culture models (for reviews see references 50 and 51) but no convincing data exist regarding the in vivo situation. In this report we demonstrate that the bacteria reside intracellularly within macrophages, as at least 88% of the analyzed bacteria (or clusters of bacteria) were located intracellularly. This result strongly supports the classification of Salmonella as an intracellular pathogen. Some macrophages contained only a few (1–3) bacteria while others harbored several (>10). Occasionally we found bacteria that appeared to be dividing, an indication of intracellular bacterial replication. The fate of the phagosome in which S. typhimurium resides after phagocytosis by cultured macrophages is again contentious; data which support the fusion of the phagosome with the lysosomal compartment in the host cell as well as data describing the inhibition of phagosome/lysosome fusion have been published (41, 52–57). In preliminary experiments using our confocal approach, we occasionally saw colocalization of the bacteria with LAMP-1, a marker for the lysosomal membrane glycoproteins. We are currently using this method to study the intracellular compartments in which Salmonella and other intracellular pathogens survive inside host cells in vivo.

When higher doses of bacteria were administered, the bacteria were visualized in the liver at days 1 and 2 after infection. We looked for possible colocalization of the bacteria to the hepatocytes at these early time points since the hepatocytes have been suggested as the primary site for Salmonella proliferation during the early phase of the disease (10, 11). We found that the bacteria at both doses colocalized to the CD18-positive phagocytes, and we did not detect any bacteria inside hepatocytes. This is not surprising, since the few experiments showing S. typhimurium inside hepatocytes have used very high infective doses and treatment of the mice with antibodies that either depleted the mice of neutrophils or inhibited the neutrophils from accumulating at the infectious foci (10, 11, 24). Furthermore, studies using a murine hepatocyte cell line (58) showed that S. typhimurium invaded the cells poorly (0.3%). In addition, LPS- and cytokine-activated hepatocytes (used to mimic the in vivo situation) also displayed an antibacterial activity, results that argue against the hepatocytes as the primary site for Salmonella proliferation.

An interesting feature of several pathogenic bacteria is their capacity to induce apoptosis in mammalian cells as a part of their disease process (46). We found that infection with S. typhimurium exerts a cytotoxic effect on the neutrophils/macrophages in the mouse liver whether or not the dying phagocytes contained intracellular bacteria. If apoptosis is a direct effect due to the presence of bacteria or a secondary effect due to the inflammatory response (e.g., production of cytokines, nitric oxide, and oxidative burst) is unclear at present. Recently, it was shown that S. typhimurium induces apoptosis in cultured and bone marrow–derived macrophages in vitro (47, 48). We are currently determining the contribution in vivo of the invasion-associated type III secretion system and the bacterial outer membrane protein OmpR, both of which were necessary for cytotoxicity in vitro (44, 47). The relevance of apoptosis in Salmonella infections could relate to evasion of the host's immune response. Neutrophils have been shown to be important in the early anti-Salmonella defense in the liver (29). Induction of neutrophil cell death may allow bacterial survival and subsequent invasion of macrophages to establish an infection.

Although much knowledge about Salmonella's interactions with host cells has been gained from tissue culture models, little is known about the situation in vivo, mainly due to a shortage of relevant experimental methods. The method described in this report can be used to study the location of pathogenic bacteria in vivo as well as the morphological changes that occur. Thus, it should be a useful method to extend the data obtained from in vitro systems to study pathogenesis in vivo. Work in our laboratory is currently underway to characterize several of the previously described Salmonella mutants using this system. The CLSM method has broad applicability and can be used to address many different issues. Possible areas of research include studies of other pathogens in other organs (e.g., lung, spleen, and intestine), intracellular trafficking of pathogen-containing phagosomes, and liposome targeting in vivo. The major limitation is the availability of an antibody recognizing the object of interest, but many of these are available commercially as well as from within the research community.

Figure 2.

Destruction of the liver parenchyma due to a Salmonella infection. TxR-phalloidin labeling of (a) uninfected liver, (b) liver infected with 65 CFU SL1344 at day 3 after infection, and (c) the same dose at day 5 after infection showing disintegration of the liver parenchyma as the Salmonella infection proceeds. At day 3, small inflammatory foci appeared which rapidly enlarged and became more numerous resulting in loss of liver morphology. Each image is a projection of a 1.2-μm z-stack collected through the ×20 objective on a Bio-Rad MRC-600 confocal microscope. h, Hepatocyte; s, sinusoid; bc, bile canaliculi; f, foci of infection. Bar, 50 μm.

Figure 3.

The inflammatory foci consist of infiltrating leukocytes and bacteria. Mouse liver sections labeled with TxR-phalloidin (purple), CD18-Cy5 (pink), and anti-Salmonella–FITC (green/yellow) in (a) uninfected liver, (b) liver infected with 65 CFU SL1344 at day 3 after infection, and (c) the same dose at day 5 after infection. All images are projections of 8-μm z-stacks collected through the ×20 objective on a Bio-Rad MRC-600 confocal microscope. Red labeling in a shows the presence of the resident Kupffer cells, and the arrows in c indicate interstitial bacteria. Bar, 50 μm.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Ladic, M.A. Stein, and L. Matsuuchi for helpful discussions, L. Ladic for assisting in the production of Fig. 5, c and d, and I. Haidl for providing T cell and B cell specific antibodies.

Footnotes

A. Richter-Dahlfors is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Wenner-Gren Foundations, Stockholm, Sweden, and the work was supported by an operating grant to B.B. Finlay from the Medical Research Council of Canada. B.B. Finlay is an MRC Scientist and a Howard Hughes International Scholar.

Abbreviations used in this paper: CLSM, confocal laser scanning microscopy; TxR, Texas red.

Reference

- 1.Bakken K, Vogelsang TM. The pathogenesis of Salmonella typhimuriuminfection in mice. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1950;27:41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1950.tb05191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller CP, Bohnhoff M. Changes in the mouse's enteric microflora associated with enhanced susceptibility to Salmonellainfection following streptomycin treatment. J Infect Dis. 1963;113:59–66. doi: 10.1093/infdis/113.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins FM. Salmonellosis in orally infected specific pathogen-free C57Bl mice. Infect Immun. 1972;5:191–198. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.2.191-198.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlay BB. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of Salmonellapathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1994;192:163–185. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78624-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galan JE. Molecular and cellular bases of Salmonellaentry into non-phagocytic cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;209:43–60. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85216-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields PI, Swanson RV, Haidaris CG, Heffron F. Mutants of Salmonella typhimuriumthat cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5189–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunlap NE, Benjamin W, Jr, Berry AK, Eldridge JH, Briles DE. A ‘safe-site' for Salmonella typhimuriumis within splenic polymorphonuclear cells. Microb Pathog. 1992;13:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90019-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suter E. Interaction between phagocytes and pathogenic microorganisms. Bacteriol Rev. 1956;20:94–132. doi: 10.1128/br.20.2.94-132.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nnalue NA, Shnyra A, Hultenby K, Lindberg AA. Salmonella choleraesuis and Salmonella typhimuriumassociated with liver cells after intravenous inoculation of rats are localized mainly in Kupffer cells and multiply intracellularly. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2758–2768. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2758-2768.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin FR, Wang XM, Hsu HS, Mumaw VR, Nakoneczna I. Electron microscopic studies on the location of bacterial proliferation in the liver in murine salmonellosis. Br J Exp Pathol. 1987;68:539–550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conlan JW, North RJ. Early pathogenesis of infection in the liver with the facultative intracellular bacteria Listeria monocytogenes, Francisella tularensis, and Salmonella typhimuriuminvolves lysis of infected hepatocytes by leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5164–5171. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5164-5171.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu HS. Pathogenesis and immunity in murine salmonellosis. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:390–409. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.390-409.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawley, J.B. 1995. Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy. Plenum Press, New York/London. 632 pp.

- 14.Hoiseth SK, Stocker BA. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimuriumare non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature (Lond) 1981;291:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung KY, Finlay BB. Intracellular replication is essential for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11470–11474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter PB, Collins FM. The route of enteric infection in notmal mice. J Exp Med. 1974;139:1189–1203. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.5.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arias, I.M., J.L. Boyer, N. Fausto, W.B. Jakoby, D.A. Schachter, and D.A. Shafritz. 1994. The Liver: Biology and Pathobiology. Raven Press Ltd., New York. 1628 pp.

- 18.Wessendorf MW, Brelje TC. Which fluorophore is brightest? A comparison of staining obtained using Fluorescein, Tetramethylrhodamine Lissamine Rhodamine, Texas Red, and Cyanine 3.18. Histochemistry. 1992;98:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00716998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubin, R.H., and L. Weinstein. 1977. Salmonellosis: microbiologic, pathologic and clinical features. Stratton Intercontinental Medical Book Corp., New York. 137 pp.

- 20.Faulstich H, Zobeley S, Rinnerthaler G, Small JV. Fluorescent phallotoxins as probes for filamentous actin. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1988;9:370–383. doi: 10.1007/BF01774064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brulet P, Babinet C, Kemler R, Jacob F. Monoclonal antibodies against trophectoderm-specific markers during mouse blastocyst formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:4113–4117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez-Madrid F, Simon P, Thompson S, Springer TA. Mapping of antigenic and functional epitopes on the α- and β-subunits of two related mouse glycoproteins involved in cell interactions, LFA-I and Mac-l. J Exp Med. 1983;158:586–602. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.2.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakoneczna I, Hsu HS. The comparative histopathology of primary and secondary lesions in murine salmonellosis. Br J Exp Pathol. 1980;61:76–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conlan JW. Neutrophils prevent extracellular colonization of the liver microvasculature by Salmonella typhimurium. . Infect Immun. 1996;64:1043–1047. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.1043-1047.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hestdal K, Ruscetti FW, Ihle JN, Jacobsen SEW, Dubois CM, Kopp WC, Longo DL, Keller JR. Characterization and regulation of RB6-8C5 antigen expression on murine bone marrow cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tepper RI, Coffman RL, Leder P. An eosinophil-dependent mechanism for the anti-tumor effect of IL-4. Science (Wash DC) 1992;257:548–551. doi: 10.1126/science.1636093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sjöstedt A, Conlan JW, North RJ. Neutrophils are critical for host defense against primary infection with the facultative intracellular bacteria Francisella tularensisin mice and participate in defense against reinfection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2779–2783. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2779-2783.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conlan JW. Early pathogenesis of Listeria monocytogenesinfection in the mouse spleen. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:295–302. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-4-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conlan JW. Critical roles of neutrophils in host defense against experimental systemic infections of mice by Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella typhimurium, and Yersinia enterocolitica. . Infect Immun. 1997;65:630–635. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.630-635.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraal G, Janse M. Marginal metallophilic cells of the mouse spleen identified by a monoclonal antibody. Immunology. 1986;58:665–669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dialynas DP, Wilde DB, Marrack P, Pierres A, Wall KA, Havran W, Otten G, Loken MR, Pierres M, Kappler J, Fitch FW. Characterization of the murine antigenic determinant, designated L3T4a, recognized by monoclonal antibody GK1.5: expression of L3T4a by functional T cell clones appears to correlate primarily with class II MHC antigen-reactivity. Immunol Rev. 1983;74:29–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1983.tb01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ledbetter JA, Herzenberg LA. Xenogenic monoclonal antibodies to mouse lymphoid differentiation antigens. Immunol Rev. 1979;47:63–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1979.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coffman B. Surface antigen expression and immunoglobulin rearrangement during mouse pre–B cell development. Immunol Rev. 1982;69:5–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1983.tb00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo YN, Hsu HS, Mumaw VR, Nakoneczna I. Electronmicroscopy studies on the bactericidal action of inflammatory leukocytes in murine salmonellosis. J Med Microbiol. 1986;21:151–159. doi: 10.1099/00222615-21-2-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang XM, Lin FR, Hsu HS, Mumaw VR, Nakoneczna I. Electronmicroscopic studies on the location of Salmonellaproliferation in the murine spleen. J Med Microbiol. 1988;25:41–47. doi: 10.1099/00222615-25-1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin FR, Hsu HS, Mumaw VR, Moncure CW. Confirmation of destruction of salmonellae within murine peritoneal exudate cells by immunocytochemical technique. Immunology. 1989;67:394–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin FR, Hsu HS, Mumaw VR, Nakoneczna I. Intracellular destruction of salmonellae in genetically resistant mice. J Med Microbiol. 1989;30:79–87. doi: 10.1099/00222615-30-1-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunlap NE, Benjamin W, Jr, McCall R, Jr, Tilden AB, Briles DE. A ‘safe-site' for Salmonella typhimuriumis within splenic cells during the early phase of infection in mice. Microb Pathog. 1991;10:297–310. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90013-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fields PI, Groisman EA, Heffron F. A Salmonellalocus that controls resistance to microbicidal proteins from phagocytic cells. Science (Wash DC) 1989;243:1059–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.2646710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller SI, Kukral AM, Mekalanos JJ. A two-component regulatory system (phoP phoQ) controls Salmonella typhimuriumvirulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5054–5058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alpuche-Aranda CM, Swanson JA, Loomis WP, Miller SI. Salmonella typhimuriumactivates virulence gene transcription within acidified macrophage phagosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10079–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller SI, Mekalanos JJ. Constitutive expression of the phoP regulon attenuates Salmonellavirulence and survival within macrophages. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2485–2490. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2485-2490.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buchmeier NA, Heffron F. Intracellular survival of wild-type Salmonella typhimuriumand macrophage-sensitive mutants in diverse populations of macrophages. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.1-7.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindgren SW, Stojiljkovic I, Heffron F. Macrophage killing is an essential virulence mechanism of Salmonella typhimurium. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4197–4201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Densen, P., and G.L. Mandell. 1990. Granulocytic phagocytes. In Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. G.L. Mandell, R.G. Douglas, and J.E. Bennet, editors. Churchill Livingstone, New York. 81–101.

- 46.Chen Y, Zychlinsky A. Apoptosis induced by bacterial pathogens. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:203–212. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen LM, Kaniga K, Galan JE. Salmonellaspp. are cytotoxic for cultured macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1101–1115. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.471410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monack DM, Raupach B, Hromockyj AE, Falkow S. Salmonella typhimuriuminvasion induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9833–9838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker PR, Kokileva L, LeBlanc J, Sikorska M. Detection of the initial stages of DNA fragmentation in apoptosis. Biotechniques. 1993;15:1032–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richter-Dahlfors, A.A., and B.B. Finlay. 1997. Samonella interactions with host cells. In Host Response to Intracellular Pathogens. S.H.E. Kaufmann, editor. R.G. Landes Company, Austin, TX. 252–270.

- 51.Jones BD, Falkow S. Salmonellosis: host immune responses and bacterial virulence determinants. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:533–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carrol, M.E., P.S. Jackett, V.R. Aber, and D.B. Lowrie. 1979. Phagolysosome formation, cyclic adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate and the fate of Salmonella typhimurium within mouse peritoneal macrophages. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1 10:421–429. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Oh Y-K, Alpuche-Aranda C, Berthiaume E, Jinks T, Miller SI, Swanson JA. Rapid and complete fusion of macrophage lysosomes with phagosomes containing Salmonella typhimurium. . Infect Immun. 1996;64:3877–3883. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3877-3883.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buchmeier NA, Heffron F. Inhibition of macrophage phagosome-lysosome fusion by Salmonella typhimurium. . Infect Immun. 1991;59:2232–2238. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2232-2238.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ishibashi Y, Arai T. Specific inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion in murine macrophages mediated by Salmonella typhimuriuminfection. FEMS (Fed Eur Microbiol Soc) Microbiol Immunol. 1990;2:35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb03476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kagaya K, Watanabe K, Fukazawa Y. Capacity of recombinant gamma interferon to activate macrophages for Salmonella-killing activity. Infect Immun. 1989;57:609–615. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.609-615.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rathman M, Barker LP, Falkow S. The unique trafficking pattern of Salmonella typhimurium–containing phagosomes in murine macrophages is independent of the mechanism of bacterial entry. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1475–1485. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1475-1485.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lajarin F, Rubio G, Galvez J, Garcia-Penarrubia P. Adhesion, invasion and intracellular replication of Salmonella typhimuriumin a murine hepatocyte cell line. Effect of cytokines and LPS on antibacterial activity of hepatocytes. Microb Pathog. 1996;21:319–329. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]