Abstract

Previous studies have shown that integrin α chain tails make strong positive contributions to integrin-mediated cell adhesion. We now show here that integrin α4 tail deletion markedly impairs static cell adhesion by a mechanism that does not involve altered binding of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 ligand. Instead, truncation of the α4 cytoplasmic domain caused a severe deficiency in integrin accumulation into cell surface clusters, as induced by ligand and/ or antibodies. Furthermore, α4 tail deletion also significantly decreased the membrane diffusivity of α4β1, as determined by a single particle tracking technique. Notably, low doses of cytochalasin D partially restored the deficiency in cell adhesion seen upon α4 tail deletion. Together, these results suggest that α4 tail deletion exposes the β1 cytoplasmic domain, leading to cytoskeletal associations that apparently restrict integrin lateral diffusion and accumulation into clusters, thus causing reduced static cell adhesion. Our demonstration of integrin adhesive activity regulated through receptor diffusion/clustering (rather than through altered ligand binding affinity) may be highly relevant towards the understanding of inside–out signaling mechanisms for β1 integrins.

Cell adhesion is a critical event in the initiation and maintenance of a wide array of physiological processes, including embryogenesis, hematopoiesis, tumor cell metastasis, and the immune response. The integrin protein family, which consists of 22 distinct α and β heterodimers, mediates cell adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins, serum proteins, and counterreceptors on other cells (1). Through inside–out signaling, integrin adhesive activity can be triggered by multiple agonists, and integrins display multiple activation states within different cell types, independent of changes in integrin expression levels (2). Many studies of integrin regulation have focused on conformational changes, altered ligand binding affinity, and/or modulation of postligand binding events (e.g., cell spreading) (3–6). However, a novel mechanism was recently put forth, suggesting that activation of adhesion may involve release of cytoskeletal constraints, leading to increased integrin lateral mobility (7, 8). Implicit is the assumption that increased mobility is proadhesive because it leads to increased integrin accumulation at an adhesive site, and thus greater adhesion strengthening.

Here, we have used an α4 integrin cytoplasmic domain mutant to provide strong evidence for this hypothesis. Upon truncation of the α4 cytoplasmic domain, the α4β1 integrin shows severe impairments in both constitutive and phorbol ester–induced static cell adhesion (9, 10), and also shows deficient adhesion strengthening under shear (11, 12). However, the reason for these defects was not previously understood. Because other integrin cytoplasmic domain mutations cause altered ligand binding (3, 13, 14), we closely examined binding of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-11 (15) to mutant and wild-type α4β1 integrin. Not finding any alterations in ligand binding, we then examined receptor accumulation into cell surface clusters, and integrin lateral mobility. The results strongly support the hypothesis that integrin diffusion/clustering, independent of alterations in ligand binding, can play a major role in regulating integrin adhesive functions.

Materials and Methods

Cells.

K562 erythroleukemia cells and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with cDNAs representing the wild-type human α4 integrin (−α4wt), chimeric α4 containing the extracellular and transmembrane domains of α4 with the cytoplasmic domain of α2 (-X4C2), and a truncated α4 integrin lacking a cytoplasmic domain (-X4C0), have been described elsewhere (9). Untransfected or mock-transfected K562 and/or CHO cells were used as negative controls. K562 transfectants were maintained in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 mg/ml G418 sulfate (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), and antibiotics, whereas CHO transfectants were maintained in MEMα− media containing 10% dialyzed FBS, 0.5 mg/ml G418 sulfate, and antibiotics.

Reagents and Antibodies.

The antibodies used in this study include anti-α4, B5G10 (16), and A4-PUJ1 (17); anti-CD32 (anti-FcγRII), 4.6.19 (18); fluorescein-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG (Cappel, Westchester, PA); fluorescein-conjugated goat anti– mouse κ (Caltag, San Francisco, CA); negative control mAb J-2A2 (19); and mAb 15/7, recognizing a β1 epitope induced by manganese or ligand (20). Fluoresceinated B5G10 was produced using N-hydroxy succinimide (NHS)–fluorescein (Pierce, Rockford, IL), as described by the manufacturer. Recombinant soluble VCAM (rsVCAM) and alkaline phosphatase (AP)–conjugated VCAM–Ig (VCAM–Ig–AP) were a gift from Dr. Roy Lobb (Biogen, Inc., Cambridge, MA) and prepared as described elsewhere (15). The VCAM–Ig–AP contains the two NH2-terminal domains of human VCAM fused to the hinge, CH2, and CH3 domains of human IgG1. A purified VCAM–mouse C κ chain fusion protein (VCAM-κ) was a gift from Dr. Philip Lake (Sandoz Co., East Hanover, NJ). VCAM-κ was produced as a soluble protein from sf 9 cells and contains all seven human VCAM domains, except the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains, which have been replaced by a 100–amino acid mouse C κ segment. The CS-1 peptide (GPEILDVPST) derived from fibronectin was synthesized at the Dana-Farber Molecular Biology Core facility (Boston, MA).

Flow Cytometry.

Flow cytometric assays were performed as described (21). For determination of 15/7 epitope expression, K562 cells were preincubated (10 min) with 2 mM EDTA (in PBS), washed and suspended in assay buffer (24 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4 [Tris-buffered saline; TBS], 5% BSA, 0.02% NaN3) with or without MnCl2 and/or CS-1 peptide. Then, mAb 15/7 or negative control mAb J-2A2 was added and mean fluorescence intensities were determined. Results for 15/7 expression are given as a percent of α4β1 levels (% 15/7 = [15/7 − J2A2]/[A4-PUJ1 − J2A2] × 100). Untransfected K562 cells (expressing the α5β1 integrin) showed no constitutive or divalent cation-induced 15/7 expression.

VCAM–Ig–AP Direct Ligand Binding Assay.

A detailed description of a high sensitivity, direct ligand binding assay has been described elsewhere (15). In brief, cells in 96-well porous plates were incubated with a VCAM–Ig fusion protein conjugated with AP (VCAM–Ig–AP), and then washed using a Millipore Multiscreen filtration manifold. Bound VCAM–Ig–AP was then detected by colorimetric assay using p-nitrophenyl phosphate.

VCAM-κ Indirect Ligand Binding Assay.

Transfected K562 cells were incubated for 10 min on ice with TBS containing 2 mM EDTA, washed three times with assay buffer (TBS, 2% BSA), and resuspended in assay buffer containing the desired concentrations of VCAM-κ and either MnCl2 or 5 mM EDTA. Cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 min, washed two times in assay buffer containing 2 mM MnCl2, and subsequently incubated for 30 min at 4°C with assay buffer containing fluorescein-conjugated goat anti–mouse κ antibodies. Cells were washed two times and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde. VCAM-κ binding on K562 cells was analyzed using a FACScan® flow cytometer to give mean fluorescence intensity units. Background binding of VCAM-κ (i.e., VCAM-κ binding in the presence of 5 mM EDTA) was subtracted and data were also corrected for α4 surface expression, if applicable.

Cell Adhesion.

The effects of cytochalasin D on cell adhesion were performed as previously described (7), with minor modifications. In brief, BCECF-AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) –labeled cells were pretreated with various doses of cytochalasin D (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were added to 96-well plates previously coated overnight with α4 ligands and blocked with 0.1% heat-denatured BSA for 45 min at 37°C. Plates were centrifuged at 500 rpm for 2 min and analyzed in a Cytofluor 2300 measurement system (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA). Plates were incubated for an additional 15 min at 37°C, washed 3–4 times with adhesion media, and fluorescence was reanalyzed. Background binding to heat-denatured BSA alone was typically <5% and was subtracted from experimental values. Data is expressed as fold induction in cell adhesion, and calculated (adhesion in the presence of cytochalasin D/adhesion in the absence of cytochalasin D) from triplicate cultures.

Confocal Microscopy.

K562 cells were incubated on ice for 10 min in PBS containing 2 mM EDTA, washed, and resuspended in assay buffer (TBS, 5% BSA, 0.02% NaN3). For examination of VCAM-induced clustering of α4, cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml of mAb 4.6.19 to block FcγRII sites, and then with 500 nM rsVCAM and 2 mM MnCl2 in assay buffer for 45 min. Cells were washed two times in assay buffer containing 2 mM MnCl2, incubated an additional 30 min in assay buffer containing fluoresceinated B5G10 mAb, washed, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. For detection of α4 clustering induced by secondary antibodies, K562 cells were incubated for 30 min in assay buffer (PBS substituted for TBS) containing purified B5G10, washed, incubated an additional 30 min with fluorescein-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG, washed, and fixed as above. All procedures were done at 4°C in the presence of 0.02% NaN3 to prevent internalization. Fixed cells were resuspended in Fluorosave reagent (Calbiochem Novabiochem, La Jolla, CA), mounted onto slides, and fluorescence was analyzed using a Zeiss model LSM4 confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with an external argon–krypton laser (488 nm). To evaluate cell surface fluorescence, optical sections of 0.5-μm thickness were taken at the center and at the cell membrane of representative cells. Images of 512 × 512 pixels were digitally recorded within 4 s and printed with a Kodak 8650 PS color printer, using Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

Analysis of α4β1 Diffusion.

40-nm colloidal gold particles (EY Laboratories, San Mateo, CA) were coated with antibody using a biotin–avidin linkage as described (22). In brief, gold particles were coated with ovalbumin (20 μg/ml gold suspension) at pH 4.7, followed by blocking with 0.05% PEG 20K. After washing (three times with 0.05% PEG 20K/PBS; 16.5K g for 10 min), particles were reacted with NHS–LC–biotin (20 μg/ml gold; Pierce) overnight on ice. Particles were subsequently washed three times (0.05% PEG 20K in PBS) and incubated with avidin neutralite (Molecular Probes; 1 mg/ml gold, starting volume) for 3 h on ice. The gold solution was then washed three times as described above and incubated for 3 h with biotin–B5G10 (60 μg/ ml gold, starting volume) and blocked with 1 mg BSA biotinamido caproyl (Sigma) overnight on ice.

CHO cells were cultured on silane-blocked coverslips (23) coated with vitronectin (5 μg/ml). Video experiments were carried out in phenol red–free MEM α supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 10% FCS, and 20 mM Hepes. Gold particles were added to cell-conditioned culture medium and culture dishes were sealed before mounting on a Zeiss Axiovert 100 TV inverted microscope equipped with Nomarski optics and a NA 1.3 100× plan neofluar objective. Serial, recorded video frames were digitized and analyzed for particle centroid position using previously published nanometer-resolution techniques (24).

Mean square displacement (MSD) with respect to time was calculated for each particle centroid trace and two-dimensional diffusion coefficients were calculated by fitting MSD curves with the equation MSD = 4Dt + v2t2 or by linear regression of the first 0.5 s of the MSD curve (25). P values were calculated using Student's t test.

Results

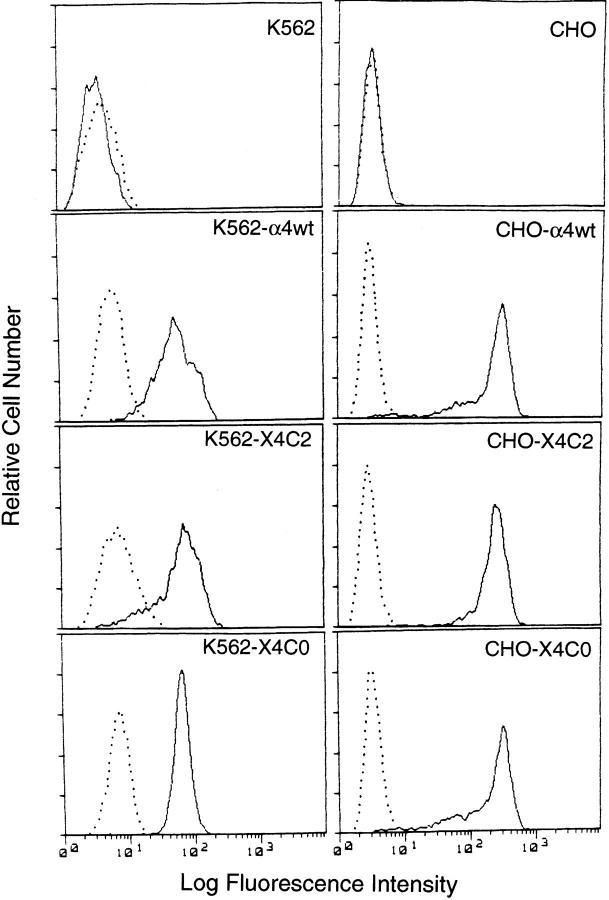

Previously, it was shown that deletion of the α4 cytoplasmic domain markedly decreased α4β1–dependent adhesion of several cell types to multiple ligands (9–12). Here, we sought to determine whether this mutation also altered the ability of α4β1 to bind soluble ligand. Wild-type α4 (-α4 wt), truncated α4 (-X4C0), and a chimeric α4 containing the cytoplasmic domain of α2 (-X4C2) were stably expressed at comparable levels on the surface of both K562 erythroleukemia and CHO cells (Fig. 1). In a direct ligand binding assay (Fig. 2 A), comparable binding of an AP-conjugated VCAM–Ig fusion protein was seen for cells expressing wild-type α4, truncated α4, or chimeric α4. The concentration of VCAM–Ig–AP yielding half-maximal direct ligand binding activity (ED50) was 1–1.5 nM for all three K562 transfectants, consistent with previously published results showing ED50 values of ∼1 nM (15). Again, no essential difference between wild-type and mutant α4 was obtained in an indirect binding assay, using fluorescein-conjugated goat anti–mouse κ antibodies to detect bound VCAM-κ (Fig. 2 B). Minimal nonspecific binding of either VCAM–Ig–AP or VCAM-κ was detected on mock-transfected K562 cells, confirming that binding is α4 integrin-dependent (Fig. 2, A and B).

Figure 1.

Expression of α4 cytoplasmic tail mutants on K562 and CHO cells. Cells transfected with vector alone (top row) or with wild-type α4, -X4C2, or -X4C0 were stained with a negative control mAb, P3 (dotted line), or with anti-α4 mAb, A4-PUJ1 (solid line). Mean fluorescence intensity shown in logarithmic scale was determined by flow cytometry, as described in Materials and Methods. Heterodimer assembly was not altered by α4 tail deletion or substitution (9).

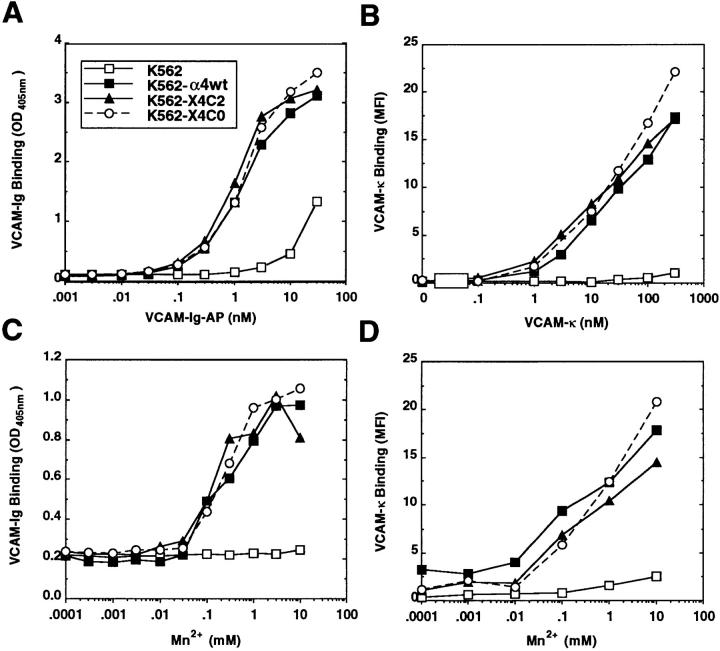

Figure 2.

Analysis of VCAM binding to K562 α4 transfectants by direct (A and C) and indirect (B and D) ligand binding assays. Recombinant VCAM fusion proteins were cultured with mock-transfected or various α4-transfected K562 cells at 4°C, as described in Materials and Methods. Direct binding of VCAM–Ig–AP was determined while varying ligand (A) in the presence of 2 mM MnCl2, or by varying Mn2+ (C) in the presence of 4 nM VCAM–Ig–AP. Bound VCAM was determined from AP activity, measured at OD405. Indirect VCAM-κ binding was analyzed by varying ligand (B) in the presence of 2 mM MnCl2 and by varying divalent cation (D) in the presence of 500 nM VCAM-κ. Fluorescein-conjugated goat anti–mouse κ IgG was used to determine the level of VCAM-κ bound and results are expressed as mean fluorescence intensities (MFI). The combined data are representative of six individual experiments.

Ligand binding was carried out in 2 mM manganese, because calcium and magnesium (either alone, or together, at ∼ 1–2 mM) fail to support binding of soluble VCAM (15, 26). To alleviate concern that manganese might mask differences in VCAM binding by inducing high affinity α4β1 (15, 26, 27), manganese was titrated over a range of concentrations, whereas VCAM was held constant at 4 nM VCAM–Ig–AP (Fig. 2 C), or 500 nM VCAM-κ (Fig. 2 D). Manganese stimulated VCAM binding that was dose-dependent and α4-specific, but again no differences were apparent between K562–α4wt, K562–X4C2 and, K562– X4C0 cells (Fig. 2, C and D).

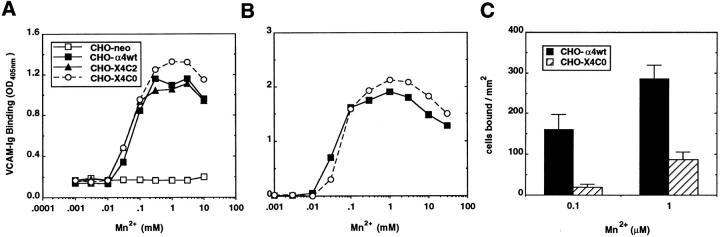

In CHO cells, compared with K562 cells, α4β1 is constitutively more active with respect to mediating cell adhesion (9, 10). Nonetheless, in the CHO cellular environment, there were again no differences in direct VCAM binding to α4wt and X4C0 integrins at either optimal (Fig. 3 A; 4 nM VCAM–Ig–AP) or suboptimal (Fig. 3 B; 1 nM VCAM– Ig–AP) doses of ligand. Half-maximal direct VCAM–Ig– AP binding occurred at ∼100 μM manganese for all transfectants examined, consistent with previously published manganese ED50 values for VCAM–α4β1 binding (15). In contrast with ligand binding, cell adhesion to immobilized VCAM was markedly diminished for CHO–X4C0 cells, compared with α4wt cells (Fig. 3 C). For example, adhesion at 0.1 and 1 μM Mn2+ was reduced by 88 and 69%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Effect of Mn2+ on binding of soluble VCAM (A and B) and adhesion to immobilized VCAM (C) in CHO α4 transfectants. Direct binding of VCAM–Ig–AP to α4-transfected CHO cells was determined while varying the divalent cation concentration in the presence of an optimal (A; 4 nM VCAM–Ig–AP) or suboptimal (B; 1 nM VCAM–Ig–AP) dose of ligand, as described in Fig. 2. OD405 nm values were higher in B due to longer substrate development times. The data are representative of four experiments. The adhesion of CHO cell transfectants to rsVCAM, coated at 2 μg/ml (C), was carried out as described previously (9, 10).

To examine α4 tail deletion effects on very late antigen 4 conformation, we used the mAb 15/7, which recognizes a β1 integrin conformation induced by ligand occupancy or manganese. When 15/7 epitope is induced by manganese, it correlates with increased ligand binding affinity (20). However, the 15/7 epitope also appears when the β1 cytoplasmic domain is deleted, and ligand binding is diminished (28). Notably, 15/7 epitope expression is most readily induced on α4β1, as compared with other β1 integrins (Bazzoni, G., L. Ma, M.L. Blue, and M.E. Hemler, manuscript submitted for publication), and thus is an especially useful tool for evaluating altered α4β1 conformations.

Negligible 15/7 epitope expression was seen for α4wt and mutant α4 integrins in K562 cells in the absence of stimulation (Table 1). However, the percentage of α4β1 molecules expressing the 15/7 epitope increased dramatically upon addition of CS-1 peptide or manganese or both together to the K562–α4wt and K562–X4C2 cells. Importantly, stimulation with manganese and/or CS-1 peptide also resulted in comparably increased 15/7 epitope on K562–X4C0 cells (Table 1). No 15/7 epitope was detected in mock-transfected K562 cells (stimulated or unstimulated), demonstrating that 15/7 was specifically reporting α4β1 conformational changes.

Table 1.

15/7 Epitope Expression on K562 Transfectants

| Percent of α4β1 expressing 15/7* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell line | No stimulation | CS-1 | Mn2+ | CS-1 + Mn2+ | ||||

| K562 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| K562–α4wt | 0 | 36 | 45 | 64 | ||||

| K562–X4C2 | 3.6 | 62 | 69 | 71 | ||||

| K562–X4C0 | 0 | 56 | 64 | 70 | ||||

15/7 expression was determined in the presence of no divalent cations or ligand (no stimulation), 100 μM CS-1 peptide, 5 mM MnCl2, or 5 mM MnCl2 + 100 μM CS-1. Results are presented as the percent of α4β1 expressing the 15/7 epitope, as described in Materials and Methods.

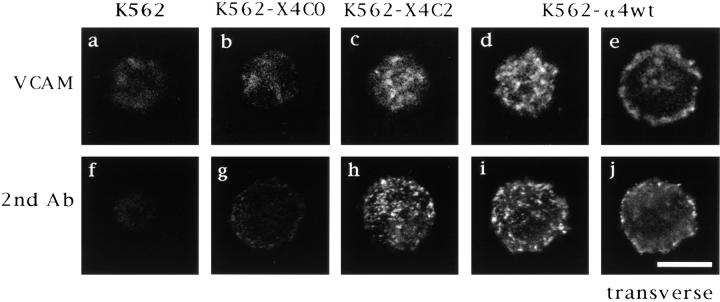

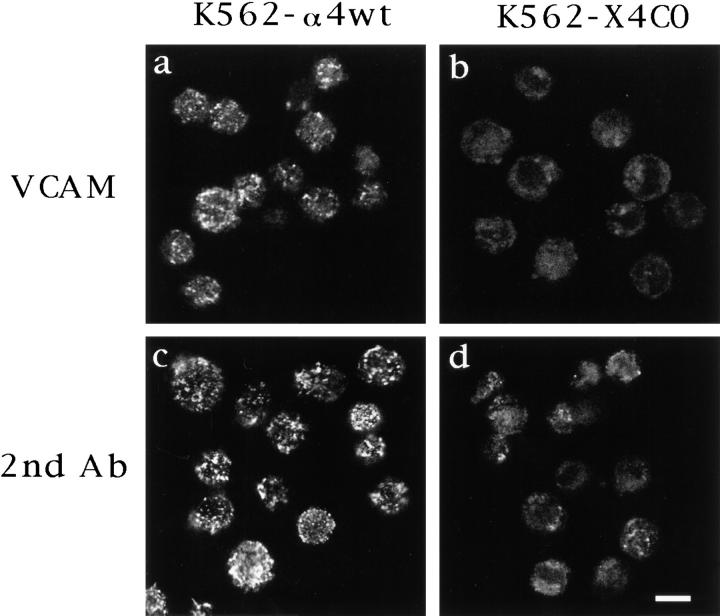

Having found that α4 tail deletion does not alter ligand binding or integrin conformation, we then sought alternative explanations for why tail deletion impairs cell adhesion. To this end, confocal laser microscopy was used to examine α4 tail deletion effects on accumulation of α4β1 in clusters. As illustrated, wild-type α4 (Fig. 4 d) and X4C2 (Fig. 4 c) were detected in clusters on the surface of K562 cells after addition of recombinant soluble VCAM in the presence of manganese. In sharp contrast, X4C0 showed hardly any VCAM-induced accumulation in clusters (Fig. 4 b). The X4C0 subunit was present on the cell surface at levels comparable to α4wt and X4C2 (see Fig. 1), suggesting that differences in signal strength reflect aggregated receptor and not differences in total receptor number. Cell surface staining was specific for α4, as shown by the lack of staining on mock-transfected K562 cells (Fig. 4 a). The distribution of α4 into clusters was dependent upon the addition of VCAM, because manganese alone (at 2 mM) did not induce clustering of α4 (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Clustering of α4 on the surface of K562 cells as examined by confocal microscopy. (a–e) Mock-transfected and α4-transfected K562 cells were pretreated with antibodies to FcγRII and subsequently incubated at 4°C with 500 nM rsVCAM in the presence of 2 mM MnCl2. Then, ligand-induced α4 distribution was determined by adding fluorescein-conjugated anti-α4 mAb B5G10, followed by confocal microscopy. The data are representative of four individual experiments. (f–j) Untransfected and α4-transfected K562 cells were incubated at 4°C with the anti-α4 mAb B5G10, and then clustering was induced by adding a secondary fluorescein-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG. The data are representative of six individual experiments. e and j represent transverse sections, whereas all other images represent surface sections. Bar, 10 μm.

Experiments were carried out at 4°C in the presence of sodium azide to prevent receptor internalization. Transverse sections of K562–α4wt cells (Fig. 4 e) showed peripheral, but not intracellular staining, consistent with cell surface clustering without receptor internalization. Also, transverse sections of K562–X4C0 cells showed no evidence for intracellular staining (data not shown). Furthermore, levels of cell surface α4 (X4C0) were unaltered after incubation with VCAM, as determined by flow cytometry (data not shown).

To extend our findings, we also examined α4 clustering induced by anti-α4 mAb, followed by polyclonal secondary antibody (Fig. 4, f–j). As indicated, clustering was again pronounced on K562–α4wt (Fig. 4, i and j) and K562– X4C2 (Fig. 4 h) cells, whereas minimal clustering was observed when the α4 tail was deleted (K562–X4C0 cells; Fig. 4 g) or when no α4 was present (Fig. 4 f ). Results in Fig. 5, showing 9–15 cells/panel, confirm the single cell results shown in Fig. 4. As indicated, nearly all of the K562– α4wt cells exhibit pronounced clustering, induced either by VCAM (Fig. 5 a) or by antibody (Fig. 5 c). In contrast, the X4C0 mutant was much less clustered (Fig. 5, b and d ), despite being expressed on the cell surface at levels nearly equivalent to α4wt (see Fig. 1).

Figure 5.

Distribution of α4 on multiple K562–α4wt and K562–X4C0 cells. Confocal microscopy was used to examine the cell surface distribution of α4 upon treatment of K562–α4wt (a and c) and K562–X4C0 (b and d ) transfectants with soluble VCAM (a and b) or with secondary antibodies (c and d ), as described in Fig. 4. Bar, 10 μm.

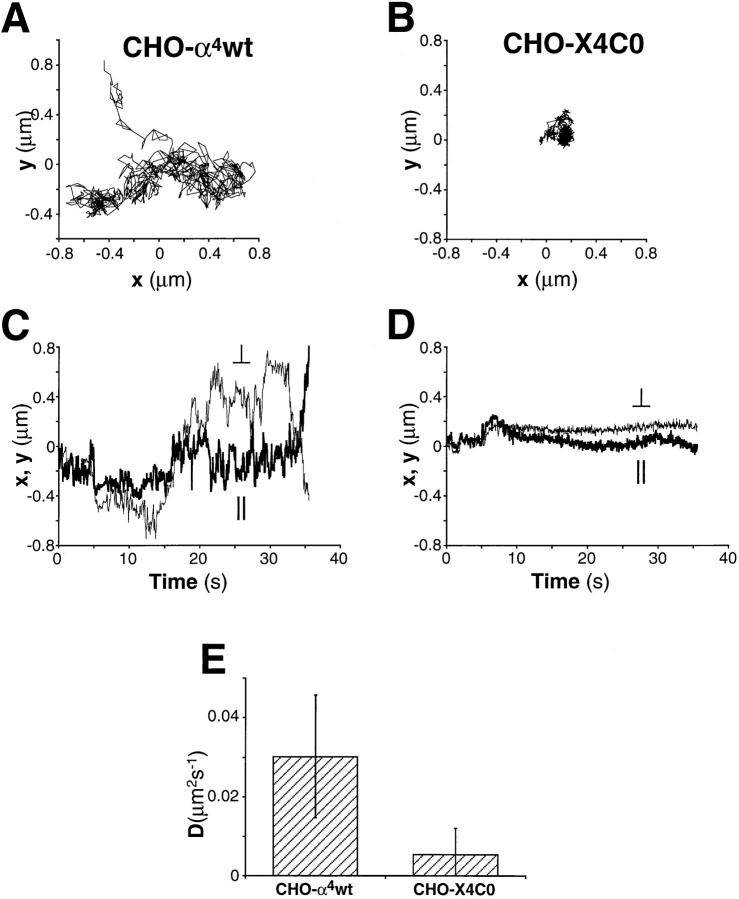

The failure of truncated α4 to form cell surface clusters raises the possibility that increased or altered associations with the underlying cytoskeleton may impair the lateral mobility of truncated α4, restricting its redistribution into a cluster. Because restricted lateral movement of integrin receptors will likely be reflected by a lower integrin diffusion rate (22, 23), next we directly measured the diffusion coefficients of wild-type and truncated α4 in CHO transfectants at 37°C. The two-dimensional diffusivity of 40-nm gold particles, coated with anti-α4 mAb, was measured on the lamellipodia of CHO–α4wt and CHO–X4C0 cells spread on an α4-independent substrate, vitronectin. Movement of gold particles was viewed by high magnification, video-enhanced differential interference contrast microscopy and particles were tracked by computer with nanometer-level accuracy (23). A nonperturbing anti-α4 mAb, B5G10, was used because this mAb neither blocks nor stimulates α4β1-mediated functions (29). It was shown elsewhere that nonperturbing antibodies coupled to 40-nm gold can report the random diffusion of integrins without stimulating the cross-linking and directed movement of these receptors (22).

As illustrated in Fig. 6, A and C, gold particles bound to the lamella of CHO–α4wt cells diffused freely with a mean diffusion coefficient of 0.03 μm2/s (Fig. 6 E), consistent with the diffusion rate observed for other β1 integrins (22), as well as other cell surface glycoproteins (30). However, truncation of the α4 cytoplasmic domain resulted in a significant decrease in the α4β1 diffusion rate (P <0.01). Particles bound to CHO–X4C0 cells exhibited reduced lateral mobility (Fig. 6, B and D), with a diffusion coefficient that was sixfold lower (0.005 μm2/s) than wild-type α4β1. No binding of gold particles was detected on mock-transfected CHO cells, demonstrating that the binding is α4β1 specific (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Analysis of α4 integrin diffusivity in α4-transfected CHO cells. 40-nm gold particles coated with nonperturbing, anti-α4 mAb (B5G10) were bound to the surface of α4-transfected CHO cells and tracked in the plane of the membrane at 37°C, as described in Materials and Methods. Representative tracks (x versus y; μm) are shown for particles on CHO– α4wt (A) and CHO–X4C0 (B). All tracks were rotated to orient cell with leading edge facing left. Also, x and y coordinates with respect to time are shown for CHO–α4wt (C ) and CHO–X4C0 (D) cells (x coordinates, fine line, ⊥; y coordinates, bold line, ∥). (E) Two-dimensional diffusivity (D; μm2/s) determined from a plot of MSD versus time of particles tracked on CHO–α4wt (n = 6) and CHO–X4C0 (n = 9) transfectants (P <0.01). Data are represented as mean deviation ± SD. No binding of anti-α4-coated particles was detected on mock-transfected CHO cells.

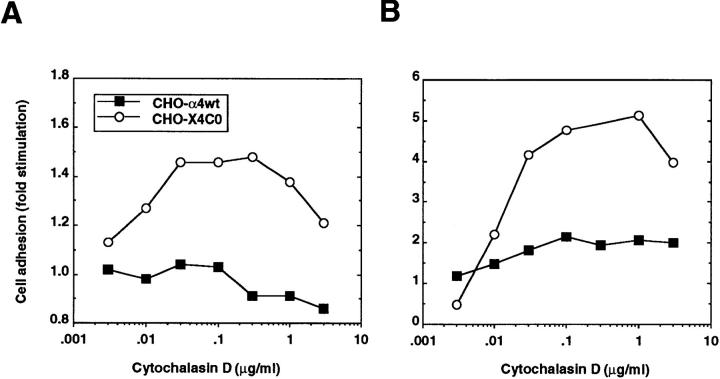

The association of integrins with cytoskeletal elements can restrain the random diffusivity of integrins and thus contribute to a diminished adhesive state (7). To examine whether the actin cytoskeleton may contribute to the deficiency in adhesion mediated by truncated α4, we disrupted actin filament organization with cytochalasin D and measured its effect on α4β1–mediated adhesion. At high doses (>10 μg/ml) of cytochalasin D, adhesion of both CHO– α4wt and CHO–X4C0 to α4 ligands was dramatically reduced (data not shown), as seen many times previously. However, at low doses, cytochalasin D stimulated markedly the adhesion of CHO–X4C0 cells to two different α4 ligands, FN40 (Fig. 7 A) and VCAM (Fig. 7 B), without much increasing the adhesion of wild-type α4 transfectants. Adhesion was α4 specific, as mock-transfected CHO cells did not adhere under these conditions (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Effect of cytochalasin D on adhesion of α4-transfected CHO cells to α4 ligands. BCECF-AM–labeled CHO–α4wt (closed squares) or CHO–X4C0 (open circles) were pretreated with various concentrations of cytochalasin D for 15 min at 37°C and subsequently allowed to adhere to surfaces coated at 4 μg/ml of FN40 (A) or 2 μg/ml of rsVCAM (B), as described in Materials and Methods. Results are presented as fold increases in adhesion calculated due to the presence of cytochalasin D. Actual adhesion values in the absence of cytochalasin D were 104.2 cells bound/mm2 for CHO–α4wt and 22.8 cells bound/mm2 for CHO–X4C0 on VCAM, respectively.

Discussion

Although α4 tail deletion has a profound negative effect on cell adhesion (9, 10; Fig. 3 C ), and on adhesion strengthening under shear conditions (11, 12), we show here that it does not alter ligand binding. Ligand binding was unaltered by α4 tail deletion (a) as measured either directly or indirectly, (b) as measured on either K562 cells or CHO cells, and (c) as shown either by manganese titration (at constant ligand) or by ligand titration (at constant manganese). Previous results also suggested that α4 tail deletion did not alter ligand binding, but that study was done only indirectly, and under single cation conditions, on a single cell line (18). In addition, α4 tail deletion was shown previously not to alter cell tethering in hydrodynamic flow (11, 12), a function that is likely dependent on univalent integrin–ligand bond formation. Thus, our results argue strongly against affinity modulation as a mechanism for α4 tail regulation of cellular adhesion. Consistent with these findings, α4 tail deletion also did not decrease the ability of divalent cations or ligand to induce α4β1 conformations detected by mAb 15/7. Similarly, α4 tail deletion was shown previously to have no effect on induction of an epitope defined by mAb 9EG7 (10), that maps to a β1 site distinct from the 15/7 site (28, 31).

It is, perhaps, not surprising that replacement of the α4 tail with the α2 tail had no effect on ligand binding or integrin conformation, because previously that mutation had no effect on cell adhesion, or tethering under flow (9, 12). Notably, replacement of the αIIb cytoplasmic domain with that of α2 did cause an increase in αIIbβ3 integrin ligand binding (14), suggesting that different rules may apply to regulation of the αIIbβ3 integrin.

The defect in cell adhesion seen for the X4C0 mutant is not due to altered ligand binding, but rather appears to arise from a reduced diffusion rate. Presumably, a lower rate of diffusion prevents the passive accumulation of integrin receptors into clusters. After initial cell contact with immobilized ligand, a dynamic, diffusion-dependent accumulation of clustered integrins may be needed to augment the overall cellular avidity for the ligand-coated surface. Notably, clustering deficiencies for the X4C0 integrin, directly measured here at 4°C, are consistent with an indirectly measured deficiency in X4C0 clustering seen previously at 37°C (18). In that case, X4C0 was defective in mediating antibody-redirected cell adhesion, a process dependent on mAb bridging between Fc receptors and clustered integrins (18).

How might α tail deletion cause decreased diffusivity leading to reduced clustering? We propose that the α chain cytoplasmic domain covers a negative site in the integrin β chain tail. Consistent with this model, it was previously shown that various integrin α chain tails can shield β chain tails from critical interactions with cytoskeletal proteins (32–34), whereas at the same time, α chains tails often make positive contributions to cell adhesion (9, 10, 35–37). Most likely, the unshielded and unregulated interactions of β tails with cytoskeletal proteins may lead to increased constitutive cytoskeletal anchoring, and thus diminished diffusion and clustering at adhesive sites. Supporting this notion, low doses of cytochalasin D markedly increased adhesion of truncated α4β1, but not wild-type α4β1. The range of cytochalasin D concentrations that promoted X4C0 adhesion (0.01–1 μg/ml) is consistent with previously published cytochalasin D concentrations that stimulated αLβ2–mediated adhesion (7).

The overall importance of both diffusion and clustering to cell adhesion has been noted previously. For example, increases in the diffusion and lateral mobility of αLβ2 (7) and LFA-3 (38) correlate with increases in cell adhesion and adhesion strengthening, respectively. Furthermore, integrin clustering is necessary for full integrin signaling (39), and clustering of αMβ2 and αLβ2 integrins promoted by phorbol ester or calcium also correlates with increased integrin-mediated adhesion (40, 41).

Regulation of integrin diffusion/clustering may be highly relevant towards the understanding of inside–out signaling mechanisms for β1 and β2 integrins, especially when affinity modulation is not involved. For example, stimulation of α4β1–mediated adhesion with macrophage inflammatory protein-1β or with anti-CD3 or anti-CD31 antibodies did not detectably induce binding of soluble VCAM (26), and phorbol esters stimulated adhesion mediated by α5β1, αMβ2, and αLβ2 without affecting soluble ligand binding (42–45). Notably, the effects of phorbol ester stimulation and integrin α4 tail deletion show a striking parallel. Like α4 tail deletion, phorbol esters also (a) fail to alter integrin affinity for ligand, (b) fail to alter α4β1–dependent tethering under shear (11, 12), but (c) markedly regulate static cell adhesion and adhesion strengthening under hydrodynamic flow (11), and (d) regulate integrin diffusion rates (7). However, whereas α4 tail deletion leads to increased cytoskeletal restraints and diminished lateral diffusion, phorbol ester appears to release active cytoskeletal restraints, thereby increasing lateral diffusion of the αLβ2 integrin (7). Together, these results emphasize that a diffusion/clustering mechanism may be of general importance for regulating adhesion, especially in the absence of changes in ligand binding (26). Also, impaired integrin diffusion/clustering may at least partly explain loss of cell adhesion observed upon the deletion of other integrin α chain cytoplasmic domains (35–37).

In conclusion, this report demonstrates that an integrin mutation can alter cell adhesion by a selective effect on receptor diffusion and clustering. In addition, the results strongly suggest that integrin cytoplasmic domains are critical for control of integrin diffusivity and clustering. We propose that control of cell adhesion at the level of integrin clustering is likely to be an important component of inside–out signaling, especially in cases when ligand binding is not altered.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Roy Lobb (Biogen, Inc., Cambridge, MA) for providing recombinant soluble VCAM and VCAM–Ig–AP, Dr. Philip Lake (Sandoz Co., East Hanover, NJ) for providing VCAM-κ, and Dr. Ted Yednock (Athena Neurosciences, San Francisco, CA) for providing mAb 15/7.

This work was supported by a research grant (GM46526 to M.E. Hemler) and a postdoctoral fellowship (AI09490 to R.L. Yauch) from the National Institutes of Health. D.P. Felsenfeld was supported by the Cancer Research Fund of the Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Foundation Fellowship.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: AP, alkaline phosphatase; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; FBS, fetal bovine serum; MSD, mean square displacement; rsVCAM, recombinant soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule; TBS, Tris-buffered saline; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule.

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation and signalling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz MA, Schaller MD, Ginsberg MH. Integrins: emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:549–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes PE, Diaz-Gonzalez F, Leong L, Wu C, McDonald JA, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. Breaking the integrin hinge: a defined structural constraint regulates integrin signaling. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6571–6574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peter K, O'Toole TE. Modulation of cell adhesion by changes in αLβ2 (LFA-1, CD11A/CD18) cytoplasmic domain/cytoskeletal interaction. J Exp Med. 1995;181:315–326. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faull RJ, Ginsberg MH. Dynamic regulation of integrins. Stem Cells. 1995;13:38–46. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530130106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart M, Hogg N. Regulation of leukocyte integrin function: affinity vs. avidity. J Cell Biochem. 1996;61:554–561. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19960616)61:4<554::aid-jcb8>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kucik DF, Dustin ML, Miller JM, Brown EJ. Adhesion-activating phorbol ester increases the mobility of leukocyte integrin LFA-1 in cultured lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2139–2144. doi: 10.1172/JCI118651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lub M, Van Kooyk Y, Figdor CG. Ins and outs of LFA-1. Immunol Today. 1995;16:479–483. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassner PD, Hemler ME. Interchangeable α chain cytoplasmic domains play a positive role in control of cell adhesion mediated by VLA-4, a β1-integrin. J Exp Med. 1993;178:649–660. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassner PD, Kawaguchi S, Hemler ME. Minimum α chain sequence needed to support integrin-mediated adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19859–19867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alon R, Kassner PD, Carr MW, Finger EB, Hemler ME, Springer TA. The integrin VLA-4 supports tethering and rolling in flow on VCAM-1. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:1243–1253. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kassner PD, Alon R, Springer TA, Hemler ME. Specialized functional roles for the integrin α4cytoplasmic domain. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:661–674. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.6.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Toole TE, Ylänne J, Culley BM. Regulation of integrin affinity states through an NPXY motif in the β subunit cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8553–8558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Toole TE, Katagiri Y, Faull RJ, Peter K, Tamura RN, Quaranta V, Loftus JC, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. Integrin cytoplasmic domains mediate inside–out signal transduction. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:1047–1059. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.6.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobb RR, Antognetti G, Pepinsky RB, Burkly LC, Leone DR, Whitty A. A direct binding assay for the vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM1) interaction with α4 integrins. Cell Adhesion & Commun. 1995;3:385–397. doi: 10.3109/15419069509081293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemler ME, Huang C, Takada Y, Schwarz L, Strominger JL, Clabby ML. Characterization of the cell surface heterodimer VLA-4 and related peptides. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:11478–11485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pujades C, Teixidó J, Bazzoni G, Hemler ME. Integrin cysteines 278 and 717 modulate VLA-4 ligand binding and also contribute to α4/180formation. Biochem J. 1996;313:899–908. doi: 10.1042/bj3130899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weitzman JB, Pujades C, Hemler ME. Integrin α chain cytoplasmic tails regulate “antibody-redirected” cell adhesion, independent of ligand binding. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:78–84. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemler ME, Strominger JL. Monoclonal antibodies reacting with immunogenic mycoplasma proteins present in human hematopoietic cell lines. J Immunol. 1982;129:2734–2738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yednock TA, Cannon C, Vandevert C, Goldbach EG, Shaw G, Ellis DK, Liaw C, Fritz LC, Tanner IL. α4β1integrin-dependent cell adhesion is regulated by a low affinity receptor pool that is conformationally responsive to ligand. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28740–28750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elices MJ, Osborn L, Takada Y, Crouse C, Luhowskyj S, Hemler ME, Lobb RR. VCAM-1 on activated endothelium interacts with the leukocyte integrin VLA-4 at a site distinct from the VLA-4/fibronectin binding site. Cell. 1990;60:577–584. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90661-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felsenfeld DP, Choquet D, Sheetz MP. Ligand binding regulates the directed movement of β1 integrins on fibroblasts. Nature (Lond) 1996;383:438–440. doi: 10.1038/383438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt CE, Horwitz AF, Lauffenburger DA, Sheetz MP. Integrin–cytoskeletal interactions in migrating fibroblasts are dynamic, asymmetric, and regulated. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:977–991. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelles J, Schnapp BJ, Sheetz MP. Tracking kinesin-driven movements with nanometre-scale precision. Nature (Lond) 1988;331:450–453. doi: 10.1038/331450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian H, Sheetz MP, Elson EL. Single particle tracking. Analysis of diffusion and flow in two-dimensional systems. Biophys J. 1997;60:910–921. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82125-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakubowski A, Rosa MD, Bixler S, Lobb R, Burkly LC. Vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)–Ig fusion protein defines distinct affinity states of the very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) receptor. Cell Adhesion Commun. 1995;3:131–142. doi: 10.3109/15419069509081282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masumoto A, Hemler ME. Multiple activation states of VLA-4: mechanistic differences between adhesion to CS1/fibronectin and to VCAM-1. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puzon-Mclaughlin W, Yednock TA, Takada Y. Regulation of conformation and ligand binding function of integrin α5β1 by the β1 cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16580–16585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pulido R, Elices MJ, Campanero MR, Osborn L, Schiffer S, García-Pardo A, Lobb R, Hemler ME, Sánchez-Madrid F. Functional evidence for three distinct and independently inhibitable adhesion activities mediated by the human integrin VLA-4: correlation with distinct α4 epitopes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10241–10245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kucik DF, Elson EL, Sheetz MP. Forward transport of glycoproteins on leading lamellipodia in locomoting cells. Nature (Lond) 1989;340:315–317. doi: 10.1038/340315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bazzoni G, Shih D-T, Buck CA, Hemler ME. mAb 9EG7 defines a novel β1integrin epitope induced by soluble ligand and manganese, but inhibited by calcium. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25570–25577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaFlamme SE, Akiyama SK, Yamada KM. Regulation of fibronectin receptor distribution. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:437–447. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.2.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Briesewitz R, Kern A, Marcantonio EE. Ligand-dependent and -independent integrin focal contact localization: the role of the α chain cytoplasmic domain. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:593–604. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.6.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ylänne J, Chen Y, O'Toole TE, Loftus JC, Takada Y, Ginsberg MH. Distinct functions of integrin α and β subunit cytoplasmic domains in cell spreading and formation of focal adhesions. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:223–233. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawaguchi S, Hemler ME. Role of the α subunit cytoplasmic domain in regulation of adhesive activity mediated by the integrin VLA-2. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16279–16285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw LM, Mercurio AM. Regulation of α6β1 integrin laminin receptor function by the cytoplasmic domain of the α6 subunit. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1017–1025. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filardo EJ, Cheresh DA. A β turn in the cytoplasmic tail of the integrin αv subunit influences conformation and ligand binding of αvβ3. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4641–4647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan P-Y, Lawrence MB, Dustin ML, Ferguson LM, Golan DE, Springer TA. Influence of receptor lateral mobility on adhesion strengthening between membranes containing LFA-3 and CD2. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:245–255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyamoto S, Akiyama SK, Yamada KM. Synergistic roles for receptor occupancy and aggregation in integrin transmembrane function. Science (Wash DC) 1995;267:883–885. doi: 10.1126/science.7846531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Detmers PA, Wright SD, Olsen E, Kimball B, Cohn ZA. Aggregation of complement receptors on human neutrophils in the absence of ligand. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:1137–1145. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.3.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Kooyk Y, Weder P, Heije K, Figdor CG. Extracellular Ca2+ modulates leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 cell surface distribution on T lymphocytes and consequently affects cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:1061–1070. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.6.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Danilov YN, Juliano RL. Phorbol ester modulation of integrin-mediated cell adhesion: a postreceptor event. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1925–1933. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faull RJ, Kovach NL, Harlan JM, Ginsberg MH. Stimulation of integrin-mediated adhesion of T lymphocytes and monocytes: two mechanisms with divergent biological consequences. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1307–1316. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altieri DC, Edgington TS. The saturable high affinity association of factor X to ADP-stimulated monocytes defines a novel function of the Mac-1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7007–7015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart MP, Cabañas C, Hogg N. T cell adhesion to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) is controlled by cell spreading and the activation of integrin LFA-1. J Immunol. 1996;156:1810–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]