Abstract

We conducted a review of the Leeds Regional Bone Tumour Registry for primary bone tumours of the spine since establishment in 1958 until year 2000. To analyse the incidence of primary tumours of the spine and to record the site of occurrence, sex distribution, survival and pathology of these tumours. Primary tumours of the spine are particularly rare, accounting for between 4 and 13% of published series of primary bone tumours. The Leeds Bone Tumour Registry was reviewed and a total of 2,750 cases of bone tumours and tumour-like cases were analysed. Consultants in orthopaedic surgery, neurosurgery, oncology and pathology in North and West Yorkshire and Humberside contribute to the Registry. Primary bone tumours of the osseous spine constitute only 126 of the 2,750 cases (4.6%). Chordoma was the most frequent tumour in the cervical and sacral regions, while the most common diagnosis overall was multiple myeloma and plasmacytoma. Osteosarcoma ranked third. The mean age of presentation was 42 years and pain was the most common presenting symptom, occurring in 95% of malignant and 76% of benign tumours. Neurological involvement occurred in 52% of malignant tumours and usually meant a poor prognosis. The establishment of Bone Tumour Registries is the only way that sufficient data on large numbers of these rare tumours can be accumulated to provide a valuable and otherwise unavailable source of information for research, education and clinical follow-up.

Keywords: Tumour, Spine, Registry

Introduction

Detection and treatment of primary tumours of the osseous spine has evolved over the last three decades and it is now possible to provide functional improvement and cure of the disease. Primary bone neoplasms of the spine are uncommon representing between 2.8 and 13% of all bone tumours [6]. Because of this rarity, the experience of an individual surgeon is limited and leads to non-uniform approach to diagnosis and treatment of the many different tumours of the spine. For this reason the establishment of a bone tumour registry provides a valuable source of information and facilitates early detection and treatment of these tumours. This paper describes the experience of the Leeds Regional Bone Tumour Registry over a period of 42 years.

Methods

The Leeds Regional Bone Tumour Registry was established at St James’ University Hospital, Leeds, in 1958. The geographic area covered by the registry includes North and West Yorkshire, Humberside and the East Riding of Yorkshire and includes the cities of Leeds, York, Bradford and Kingston-upon-Hull. In the 2001 census the population of this area was just in excess of 3.5 million. This represented a population growth of 0.5% from 1991. The unemployment rate for the area is approximately 3.7 and 20% of the population self-reported limiting long-term illness.

Two thousand seven hundred and fifty cases of primary bone tumour have been contributed by consultants of all disciplines within this region. Following a review of the clinical, radiological and histological data at monthly multi-disciplinary meetings a diagnosis for each case is determined. The panel consists of orthopaedic surgeons, neurosurgeons, oncologists and pathologists. Where necessary, referral to the National Bone Tumour Panel is made by one of the local panel members. Administration and updating of the Registry comes from the support panel that consists of a research assistant and two secretarial assistants. Long-term follow-up of Registry cases is made possible by this assistance. The meetings also provide an educational platform for the trainees in all the relevant specialties.

Results

One hundred and twenty-seven primary bone tumours arising in the spine (4.6% of all entries to the Register) have been recorded; 18 cervical, 48 thoracic, 21 lumbar and 40 sacral. One patient had bifocal chordoma involving the cervical spine and sacrum (Table 1). Of the 126 patients (66 male, 60 female) the mean age was 42 years (range 7–76 years). There were 20 children (0–18 years) with a mean age of 13 years (range 7–18 years). The mean age of the adults was 52 years (range 19–80 years). The majority of children had benign tumours (60%) in contrast to the majority of adults where 80% of the cases were malignant tumours. Aneurysmal bone cysts (three in children, three in adults), Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (one in a child, one in an adult) and osteoblastoma (four in children, two in adults) occurred in both groups.

Table 1.

Distribution of primary spinal tumours

| Tumour | Cervical | Thoracic | Lumbar | Sacral | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | |||||

| Osteochondroma | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Chondroma | 1 | 1 | |||

| Osteoblastoma | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 | |

| Osteoid osteoma | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Osteoclastoma | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Hemangioma | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Eosinophilic granuloma | 1 | 1 | |||

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Intermediate | |||||

| Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Malignant | |||||

| Chordoma | 6a | 2 | 3 | 17a | 28 |

| Osteosarcoma | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Fibrosarcoma | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Malignant giant cell tumour | 1 | 1 | |||

| Round cell sarcoma | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ewing’s sarcoma | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Reticulosarcoma | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Lymphoma | 1 | 8 | 2 | 11 | |

| Plasmacytoma/Myeloma | 3 | 24 | 4 | 2 | 33 |

| Total benign | 5 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 29 |

| Total malignant | 13a | 38 | 15 | 32a | 98a |

| Total number of tumours | 18a | 48 | 21 | 40a | 127a |

aOne case of cervical spine chordoma and sacral chordoma in the same patient

Clinical features

Pain was the most common presenting symptom, affecting 76% (22/29) of the benign and 95% (93/98) of the malignant tumours. In 7% (9/126) of patients a palpable lump was the major presenting feature (4 sacral chordoma, 2 cervical chordoma, 1 osteosarcoma, 1 lymphoma and 1 sacral epithelioid hemangioendothelioma). In 7% (9/126) of patients precipitous cord compression with or without pain was the major presenting feature (1 osteosarcoma, 1 chondrosarcoma, 1 fibrosarcoma, 5 myeloma and 1 lymphoma). In all, 22% (28/126) of patients had signs of subtotal or complete cord compression. A further 22% (28/126) of patients presented with symptoms of radiculopathy (Table 2). Neurological involvement was seen in 52% (51/98) of patients with malignant tumours and 17% (5/29) of those with benign lesions.

Table 2.

Presenting features of the axial skeleton tumours

| Feature at presentation | Malignant | Benign | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 93 | 22 | 115 |

| Mass | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| Cord compression | |||

| Acute | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Progressive | 17 | 2 | 19 |

| Radiculopathy | 25 | 3 | 28 |

Distribution of tumours

Malignant lesions predominated in the cervical (72%, 13/18), lumbar (71%, 15/21) and sacral regions (80%, 32/40). These include a case of bifocal chordoma affecting the cervical spine as well as the sacrum. The thoracic region exhibited the widest variety of diagnoses, showing 13 different tumour types. Only osteoblastoma (3 cases) occurred more than once in the benign variety whereas myeloma (24 cases) and lymphoma (8 cases) occurred frequently in this region. Once again malignant lesions predominated in the thoracic region (79%, 38/48).

Myeloma was the most common primary spinal tumour accounting for 26% (33/127) of all cases in our series. In the cervical spine the most common tumour comprising 33% (6/18) of cases was the chordoma. With the addition of the 17 sacral lesions, a total of 82% (23/28) of chordomas were found to arise predominantly at either end of the vertebral column. This was the second most common primary spinal neoplasm. Eleven cases of lymphoma (eight in the thoracic spine) were recorded in the registry, constituting a total of 44 tumours of lymphoreticular origin. Osteosarcoma was the third most frequent diagnosis with 50% (6/12) occurring in pre-existing Paget’s disease. The sacrum again was the main site of these tumours, contributing six cases. In the lumbar spine, osteosarcoma shared equal frequency of incidence (three cases) with chordoma. Osteoblastoma (three cases) was the most frequent benign tumour in the lumbar spine.

Benign tumours demonstrated no predilection for any part of the axial skeleton. The age range for their incidence overlapped with that of malignant tumours but they tended to occur at an earlier age. Aneurysmal bone cysts occurred in 4.7% (6/126) of patients, 50% of these occurred in the cervical spine.

Sex distribution

Fifty-two percent (66/127) tumours occurred in males. Malignant lesions affected males more commonly (57%, 56/98). (The bifocal sacral and cervical chordoma occurred in a female). Of 33 cases of myeloma, 23 cases (70%) occurred in males and 2/3 cases (66%) of Ewing’s tumours also occurred in males. This characteristic was reversed in benign tumours, where 66% (19/29) occurred in females. In our series, all seven cases of osteoclastoma occurred in females.

Survival

Sixty-two percent (78/126) of the patients died during the period of the study, 81% (63/78) of which had malignant lesions. The average interval from presentation to death of those with a malignant lesion was 6 years. Patients with chordoma and myeloma survived the longest amongst the malignant group. There appeared to be a relationship between outcome and the presence of neurological involvement. There were 28 cases of spinal cord compression, 18 of which died after a mean interval of 2.2 years. One patient remained paraplegic 24 years after a diagnosis of osteoclastoma. One patient with an aneurysmal bone cyst in the cervical spine presented with quadriplegia but following excision and grafting, the neurological improvement was complete. Six of the patients with benign lesions who died had neurological complications prior to death.

Pathology

In the majority of cases (116/126, 92%) the original pathologist, to whom the tissue had been sent for analysis, made the histological diagnosis. The pathology expert in the Registry panel subsequently confirmed these. However, in ten cases the definitive diagnosis reached by the registry differed from the original diagnosis (Table 3). In one case what had originally been called a malignant tumour was reclassified as benign and in two cases the reverse was true, with tumours being reclassified as malignant. Neither case of epithelioid haemangioendothelioma was diagnosed by the referring unit’s pathologist, reflecting the rare nature of this particular tumour.

Table 3.

Diagnosis changed by the tumour registry

| Initial diagnosis at referral | Definitive diagnosis of the Bone Tumour Registry |

|---|---|

| Ewing’s or metastatic neuroblastoma | Ewing’s |

| Ewing’s or lymphoma or metastatic neuroblastoma | Ewing’s |

| Osteosarcoma | Aggressive osteoblastomaa |

| Osteoid osteoma | Osteoblastoma |

| Unknown | Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma |

| Osteoclastoma | Osteosarcoma |

| Osteoblastoma | Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma |

| Hemangioma | Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma |

| Lymphoma | Plasmacytoma |

| Chondroblastic osteosarcoma | Chordoma |

aSchajowicz and Lemos [20]

Discussion

Whereas metastatic tumours of the spine are a frequent finding, primary bone tumours are uncommon. Apart from a few publications of large series of spinal bone tumours [5, 11, 22], most publications on the subject are no more than a series of case reports [12–14], and although interesting, their value is limited. An individual surgeon or even a specialist cancer centre will need to accumulate cases over several years to attain sufficient experience of these tumours to improve the accuracy of diagnosis and treatment.

Regional Bone Tumour Registries, first established by Codman in 1922 [12], have been set up in many centres in order that clinical, radiological and histological data may be amassed for larger numbers of patients. The aim of the registry is to improve diagnostic accuracy in individual cases although it can be difficult to calculate accurate incidence and prevalence rates for a region. This is because submission of information to a Registry is voluntary and it cannot be guaranteed that all cases in a particular region have been included. In addition, geographical and racial variations will influence the incidence of a particular condition in different series [9]. They also provide a review forum for complex cases. Information collated by tumour registries are useful to clinicians, epidemiologists, medical researchers and medical administrators.

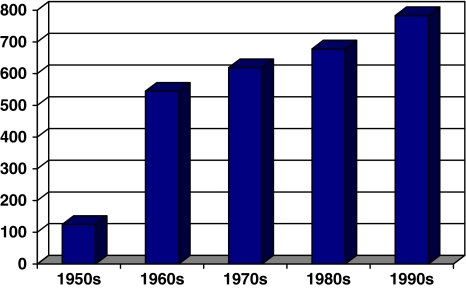

The arrangement of the bone tumour registry service in our region is such that significant numbers of primary malignant bone tumours are unlikely to be omitted from the register. Over the four decades this review spans, the numbers of tumours referred to the registry showed a gradual increase with each decade (Fig. 1). This is likely to be due to improved detection of tumours, with advances in medical imaging, particularly MRI being responsible. Benign tumours are likely to be under-represented in any tumour registry. When diagnosis is straight forward as suggested by obvious benign radiological features, the inclination to perform a biopsy and report it to the registry may be small. This may be one reason why the malignant tumours occur at more than three times the frequency as benign tumours. Nevertheless, there were differences observed in the relative frequency of various tumours recorded in published series and in our registry [4, 18]. Most notably, osteosarcoma was the third most common spinal tumour but fourth in Dahlin’s [4] and Schajowicz’s [19] series.

Fig. 1.

New referrals to Leeds Regional Bone Tumour Registry by decade

Chordoma was the second most frequent malignant tumour found in the axial skeleton and, as previously reported, the sites of predilection were the cranial and caudal ends [7, 12, 19]. Chordomas of the sacrum are more common than those of true vertebrae in both our series and previously [2, 17], although McMaster et al. [16] reported on 400 cases of chordoma over a 22 year period. Of these 131 occurred in the true vertebrae and 117 in the sacrum. Bohlman et al. [3] reported chordoma to constitute 40% of malignant tumours in the cervical spine compared to 46% identified here. The incidence of chordoma as a primary sacral tumour in this series was 42.5% (17/40), in contrast to Makely et al. [11] who have reported chordoma to account for 6% of the 17 primary sacral tumours in their series. Similar to the experience from Bristol, we had one multi-focal chordoma [17].

Myeloma is often quoted as the most common primary spinal neoplasm [4, 7, 19]. This was also the case in our study. In addition, 11 cases of lymphoma meant that the lymphoreticular malignant tumours amounted to 34% of all primary tumours. This differs from an earlier review from this registry [6] where solitary plasmacytoma accounted for 5 of 55 cases (9%). Multiple myeloma was not considered to be a primary bone malignancy in that publication [6]. Similarly, there were no cases of spinal lymphoma reported as again it was not considered a primary malignancy, although five cases of spinal lymphoma were reported in the series from the same period [10].

Hay et al. [8] reported that the aneurysmal bone cysts frequently affected the cervical spine (22%), whereas in this series 50% of all aneurysmal bone cysts in the axial skeleton occurred in the cervical spine.

Treatment of these tumours was undertaken at regional orthopaedic hospitals by many different surgeons. No consistent therapeutic programs were administered to the patients as a result, which is also partly attributable to the 42 year span over which they were seen, and to the heterogeneity of the tumour pathology and site. Nonetheless, it can be seen that the primary malignant spinal tumours are associated with very high mortality figures. The mean survival for osteosarcoma was less than 1 year, in keeping with the findings of previous studies [1].

The experience of the pathologist is an important factor in successful treatment of these tumours. Our study revealed that in ten cases (8%), the original diagnosis was changed following review of the histology, as well as relevant imaging, at the panel meetings. Obtaining biopsy is an inherently difficult procedure with a high degree of complications including misdiagnosis from unrepresentative sampling [15]. To minimize these complications, the panel encourages surgeons to consult the registry at the earliest opportunity. As newer investigative techniques become available tumours are often reclassified. Five-yearly review of cases, as practiced by the Leeds Bone Tumour Registry, enables recognition of new entities and allows new classification to be implemented. Epithelial hemangioendothelioma is one such new entity in the last decade. This tumour is easily confused with other vascular tumours and both immunochemistry and electron microscopy may provide the clues for differentiation, the same techniques that are used in establishing the diagnosis of Ewing’s sarcoma and some neural tumours [21]. In this study, we have grouped this epithelioid, angiocentric vascular tumour in the benign category, with the knowledge that some of these tumours exhibit malignant picture and metastasize.

Conclusions

It is our opinion that all primary bone tumours—not only those involved in the axial skeleton—should be recorded in regional registries. This is the only way in which reliable data can be collected about these rare neoplasms. Regular reviews, conducted by the panel, also form part of the core educational program for trainees in a number of specialties and furthers the development of knowledge in this rare and complex area.

References

- 1.Barwick KW, Havus AG, Smith J. Primary osteogenic sarcoma of the vertebral column: a clinicopathologic correlation in ten patients. Cancer. 1980;36:595–604. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800801)46:3<595::AID-CNCR2820460328>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackwell JB, Threlfall TJ, McCaul KA. Primary malignant bone tumours in Western Australia, 1972–1996. Pathology. 2005;37(4):278–283. doi: 10.1080/00313020500168737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohlman HH, Sachs BL, Carter JR, Riley L, Robinson RA. Primary neoplasms of the cervical spine: diagnosis and treatment of 23 patients. J Bone Joint Surg. 1986;86A:483–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlin DC. Bone tumours: general aspects and data on 6,221 cases. 3. Springfield: Charles C Thomas; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dilorenzo N, Guiffe H, Fortuna E. Primary spinal neoplasms in childhood: analysis of 1234 published cases (including 56 personal cases) by pathology, sex, age and site: Differences from the situation in adults. Neurochirugia. 1982;25:153–164. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1053982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dreghorn CR, Newman RJ, Hardy GJ, Dickson RA. Primary tumours of the axial skeleton. Experience of the Leeds regional tumour registry. Spine. 1990;15:137–140. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199002000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedlaender GE, Southwick WO. Tumours of the spine. In: Rothman RH, Simone FA, editors. The spine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders & Co; 1982. pp. 1022–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hay M, Paterson D, Taylor T. Aneurysmal bone cysts of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1978;60-B:406–411. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.60B3.681419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsson S-E, Lorentzon R. The incidence of malignant primary bone tumours in relation to age, sex and site: a study of osteogenic sarcoma, chondrosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma diagnosed in Sweden from 1958 to 1968. J Bone Joint Surg. 1974;56B:534–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Limb D, Dreghorn C, Murphy JK, Mannion R. Primary lymphoma of bone. Int Orthop. 1994;18:180–183. doi: 10.1007/BF00192476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu ZJ, Shiao LY, Huang CD. Analysis of pathological statistics on 1900 cases of bone tumours and tumour-like lesions. Clin J Orthop. 1982;1:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luck JV, Monsen DCG. Bone tumours and tumour-like lesions of vertebrae. In: Ruge D, Wiltse LL, editors. Spinal disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1970. pp. 274–286. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makley JT, Cohen AM, Boada E. Sacral tumours: a hidden problem. Orthopaedics. 1982;5:996–1003. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19820801-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maclellan DI, Wilson FA. Osteoid osteoma of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1987;49A:111–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mankin HJ, Mankine CJ, Simon MA. The hazards of the biopsy, revisited. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78-A:656–663. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMaster ML, Goldstein AM, Bromley CM, Ishibe N, Parry DM. Chordoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1973–1995. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:1–11. doi: 10.1023/A:1008947301735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price CHG, Jeffree GM. Incidence of bone sarcoma in SW England 1946–74, in relation to age, sex, tumour site and histology. Br J Cancer. 1977;36:511–522. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schajowicz F. Tumours and tumour-like lesions of bone and joints. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schajowicz F, Araujo EHS. Cysts and tumours of the musculo-skeletal system: Pathology. In: Harris NH, editor. Postgraduate textbook of clinical orthopaedics. Briston: Wright PSJ; 1983. pp. 605–639. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schajowicz F, Lemos C. Malignant osteoblastoma. J Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58B:202–211. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B2.932083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Triche T, Gavazzana A (1988) Bone tumours. In: Unni KK (ed) Contemporary issues in surgical pathology, vol 11. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone

- 22.Weinstein JN, Maclain RF. Primary tumours of the spine. Spine. 1987;12:843–851. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198711000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]