Abstract

The efficiency of short-segment fixation with transpedicle body augmenter (a titanium spacer with bone-ingrowth porous surface, TpBA) to treat Kümmell’s disease with cord compression (stage III) was retrospectively evaluated. No laminectomy or instrumentation reduction was done. Inclusion criteria included Frankel CDE, single-level within T10–L2. FU rate was 88%, i.e. 21 cases were included. Frankel function classification was 6E9D6C. Mean age was 72±8 years. F:M was 16:5. FU period was 48 M (range, 30–76 M). The hospitalization was 4.5±2.2 days; operation time, 70.4±17.2 min; blood loss, 150±72 cc. Final Frankel class was 20E1D. Complications included two superficial infection and one pneumonia. Body height and kyphosis were all corrected significantly and well preserved at the final visit. No TpBA dislodgement or implant failure was noted; however, three cases developed new compression fractures. The clinical outcome showed 81% with P1 or P2 by Denis pain scale. This method can decompress spinal canal, maintain kyphosis correction and vertebral restoration, prevent implant failure, and attain good clinical results.

Keywords: Kümmell’s disease, Transpedicle body augmenter, Manual reduction, Osteoporosis, Compression fracture

Introduction

Kümmell’s disease is defined as delayed post-traumatic vertebral collapse [1–3], which often occurs in an osteoporotic spine. Currently, it can be treated by vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty [4–6]. However, Kümmell’s disease may have posterior cortex breakage with cord compression, i.e. stage III [7] (Table 1), which is a relative contraindication for cement usage. In such cases, it had been treated by posterior Egg-shell procedure [8, 9] with long segment fixation or anterior decompression and instrumentation [10]. The posterior Egg-shell procedure is technically demanding and highly risky. In addition, the long-segment fixation may limit spinal motion, increase adjacent segment disease, and cause complication rates reaching 70% [11]. The anterior approach usually involves a longer operation time and may injure the internal organs, in addition to the possibility of the prosthesis sinking into an osteoporotic spine [10]. As for burst fracture management, the posterior short-segment fixation is the most common and simple treatment [12, 13], but implant failure has been noted [14]. Therefore, the challenge lies in trying to increase the success rate of posterior short-segment fixation and prevent implant failure in the long term.

Table 1.

Staging system of Kümmell’s disease

| Items | Criteria | Symptoms | Radiological Finding | MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | Body height loss < 20% No Adjacent DDD | Back pain or No symptoma |  |

|

| Stage II | Body height loss > 20% usually with adjacent DDD Dynamic mobile fracture | Back pain with/withoutb radiculopathy |  |

|

| Stage III | Posterior cortex breakage with cord compression | Back pain with/without cord injuryc |  |

|

DDD Disc degenerative disease with disc space narrowing

aMRI for other reason with accidental finding of Stage I

bStage II: back pain is the major complaint, sometimes with radiculopathy, especially in middle and low thoracic spine

cStage III: even though MRI showed posterior cortex breakage with cord compression, the symptoms of cord injury sometimes are not significant. Probably due to the slow progression of Kümmell’s disease in some cases, the spinal cord can adapt the changes to prevent significant cord injury

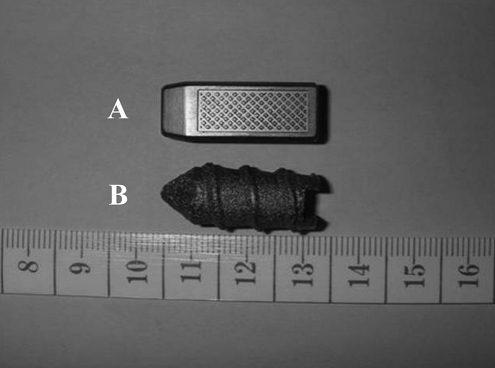

Manual reduction allowed safe reduction of the fractured vertebra and decompression of the spinal cord in acute non-osteoporotic burst fracture [15]. If manual reduction can succeed in chronic osteoporotic stage III Kümmell’s disease, subsequent decompression procedure and instrumentation reduction can be avoided. Transpedicle body augmenter (TpBA, a porous titanium spacer of various generations, Merries International Inc., Taipei, Taiwan) (Fig. 1) may reinforce the fractured vertebral body from a posterior approach with biomechanical advantages [16]. Therefore, TpBA and manual reduction may provide an answer to increase the success rate of posterior short-segment fixation for stage III Kümmell’s disease. This report attempts to explore optimal management of stage III Kümmell’s disease: manual reduction can succeed in restoring anatomic alignment and TpBA may maintain vertebral body restoration, prevent implant failure in osteoporotic spine, and improve clinical success.

Fig. 1.

The pictures showed the new (A) and old (B) generations of transpedicle body augmenters

Materials and methods

Between January 1999 and August 2003, 24 Kümmell’s disease patients with posterior wall collapse and cord compression (stage III) [7] were treated with manual reduction, short-segment posterior fixation (one above, one below), and reinforcement with autologous bone graft cum TpBA of varying sizes (7×9×20 mm3, 9×11×27 mm3, 10×13×27 mm3, etc.) Inclusion criteria required the following: function status limited to Frankel C, D, and E; single-level Kümmell’s disease; limited disease T10–L2, and primary osteoporosis. Follow-up rate was 88%. One patient died of unrelated medical illness and two patients were lost to follow-up. These three patients were excluded from this retrospective study. The demographics of the 21 patients are in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient demographics

| Items | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72±8 (61–91) |

| Female to male (ratio) | 16:5 |

| Etiology | 15 mild injury, 6 no memorized accident |

| Sympton duration (weeks) | 20 (4–100) |

| Follow-up (months) | 48 (30–76) |

| Fracture location | 1 T10, 2 T11, 8 T12, 7 L1, 3 L2 |

| Frankel performance scale | 6C, 9D, 6E |

| Denis pain scale | 3 P4, 18 P5 |

Kümmell’s disease was diagnosed by intravertebral cleft sign on CT scan or osteonecrosis with fluid signal on MRI. Preoperative evaluation protocols included anteroposterior (AP) and neutral lateral thoracolumbar radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to evaluate fracture sites and status of cord compression. The symptomatic segment was confirmed by matching clinical examination with MRI findings.

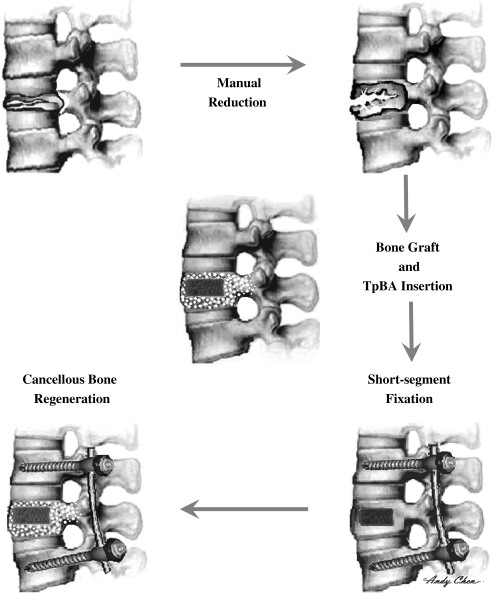

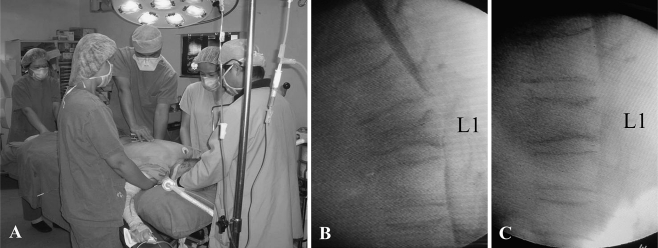

All the patients received manual reduction and short-segment fixation with posterior body reconstruction augmented by TpBA and bone graft (Fig. 2). Before anesthesia, myelogram was performed via L4/5 lumbar puncture using non-ionic contrast medium (Isovist-300, Schering AG, Berlin, Germany). If there was no allergic reaction after a 30-min observation, the patient received general anesthesia and was put in a prone position. There were no visible side effects of myelogram in this series. Then manual reduction was done: one anesthesiologist held the patient’s head, two assistants held the patient’s shoulders, one assistant held the patient’s legs, and the surgeon compressed the fractured vertebra (Fig. 3). Traction and elevation of the trunk was initiated by the shoulder assistants, and pushing force over involved level was given by the surgeon simultaneously to counter the elevation force. The success of decompression of spinal canal was confirmed by C-arm myelogram. After manual reduction, short-segment fixation followed without laminectomy or instrumentation reduction. Pedicle screws were placed at the level above and below the fractured vertebrae (two levels, four screws) using the rod screw system (Reduction–Fixation Spinal Pedicle screw system) (Advanced Spine Technology Inc. Oakland, CA, USA; UP spine system, TiTec Medical Co., Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan, Merries spine system, Merries International Inc., Taipei, Taiwan).

Fig. 2.

The flow chart shows the procedures of manual reduction, TpBA insertion, bone graft, and short segment fixation

Fig. 3.

The pictures showed the cooperation of five people to do manual reduction (a). The C-arm myelogram before manual reduction (b) showed body collapse with cord compression and post-procedure view (c) revealed the restoration of vertebral body and cord decompression

Bilateral pedicle tunnels to the vertebral body were made by an awl, followed by a guide pin, which should be checked under C-arm fluoroscopy. Then the pedicle tunnels were enlarged by serial custom-made dilators to the matched size. The pedicle size, different among individuals and at different spine levels [17, 18], should be measured preoperatively on CT or plain AP and lateral views. Because the superior and lateral cortex can be violated with no danger of neurological sequelae, the safe zone is large enough to pass the TpBA. The pedicle in this series is so osteoporotic and soft that it can be easily dilated without brittle breakage. The bony defect in the fractured vertebral body was filled through bilateral pedicle tunnels [15], with autologous bone graft mixed with calcium sulfate (OSTEOSET®, Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, TN, USA) if the autograft from the posterior iliac crest was insufficient. Then TpBA was inserted into the vertebral body through the pedicle tunnel under C-arm fluoroscopy and finally, bone graft was used to fill up the pedicle tunnel space. The posterior interlaminar fusion was done over the fixed segments. The transpedicle discectomy and intercorporeal bone graft as described by Daniaux et al. [19] was excluded. Patients wore a thoracolumbar brace for 3 months. After discharge from hospital, patients were followed up regularly. Operation time, blood loss, hospitalization, and complications were documented.

In the radiographic analysis, the cross-section area of spinal canal, anterior and posterior vertebral height, lateral Cobb’s angle, and wedge angle were measured. The cross-section area of spinal canal was measured at pre-operative and initial post-operative digital CT scan radiographs in the first 12 cases. Because the data showed highly significant differences, no more post-operative CT scan of the following patients was done. The lateral Cobb’s angle was measured, as described by Kuklo et al. [20] from the superior endplate of the vertebral body above the fracture to the inferior endplate of the vertebral body below the fracture level. Wedge angle of the index vertebra was measured as described previously by Verlaan et al. [21]. The radiographic parameters were measured on neutral thoracolumbar radiographs before the operation, initial follow-up, and at the final follow-up. All digitization of the radiographic measurements was done by the same experienced research assistant in EBM-viewer software (EBM technologies Inc., Taipei, Taiwan) with an accuracy of ±0.1 mm. Repeat measurements of the same vertebral levels after a 10-day interval with the same observer demonstrated an error of ±0.13 cm2 in cross-section area, 1.2 mm in height, 2.3° in lateral Cobb’s kyphosis and 2.2°in wedge angle. The radiographs at the final visit were analyzed in detail and recorded if there should be implant loosening, migration or failure of posterior instrumentation or TpBA were found. Clinical results were assessed by the Frankel Performance Scale (Grade A–E) [22] and Denis Pain Scale (Grade P1–P5) [23]. Denis Pain Scale shows results with P1 as no pain; P2, occasional, minimal pain with no need for medication; P3, moderate pain, occasional medications, no interruption in work or activities of daily living; P4, moderate to severe pain, occasional absence from work, significant change in activities of daily living; and P5, constant severe pain, chronic medications.

ANOVA was used for statistical analysis of lateral Cobb’s and wedge angles, posterior and anterior vertebral height among the data of pre-operative, immediate, and final follow-up. Significant differences were further assessed using Duncan’s multiple range tests. Paired t-test was done between the immediate and final corrections of lateral Cobb’s angle, wedge angle, posterior and anterior vertebral height, and between preoperative and postoperative cross-section area of the spinal canal. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze Denis Pain Scale data. All the data presented in this paper has been mean ± standard deviation. The level of statistical significance was chosen at P < 0.05.

Results

Operation time and hospitalization were short and blood loss was limited. The hospitalization interval was 4.5±2.2 days (range, 3–10 days), with operation time of 70.4±17.2 min (range, 45–90 min). The blood loss was 150±72 cc (range, 100–450 cc). No neurological deterioration was found. The clinical outcome showed ten P1, seven P2, one P3, two P4, and one P5 by Denis pain scale. At the final visit, significantly more patients reported absence of pain, or had only minimal or occasional pain (Grade P1 or P2) compared to their pre-operative status (81 vs. 0%, P < 0.001), and few had with severe or constant pain (Grade P4 and P5) (14 vs. 100%, P < 0.001). All the patients recovered to Frankel E except one patient with Frankel D due to untreated new compression fracture. The complications included one postoperative pneumonia and two superficial wound infection secondary to wound pressure sore. After medical care and debridment, all three cases recovered well. Cephalad rekyphosis detected by follow-up radiographs was noted in three cases due to adjacent compression fractures.

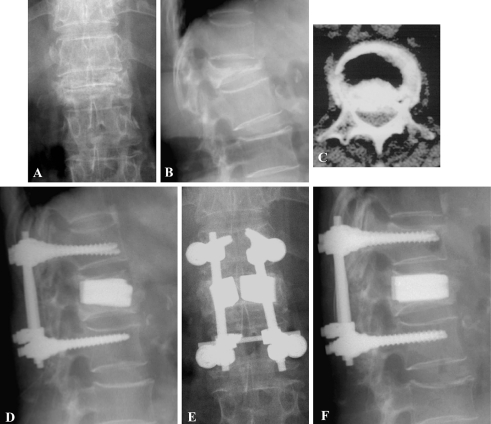

Anterior and posterior body heights and kyphotic deformity were all corrected and well preserved at the final visit (Table 3, Figs. 4, 5). The cross-section area at the involved spinal canal was 1.31±0.43 cm2 preoperatively and 2.53±0.78 cm2 postoperatively (P < 0.001). The final anterior and posterior body height corrections were 14.2±7.2 and 5.5±3.2 mm. The losses in anterior and posterior body height corrections at final visit were 2.3±1.3 mm (13.8%) and 0.3±0.1 mm (5.2%). The final correction was 18.4°±6.9° in lateral Cobb’s angle and 18.6°±9.7° in wedge angle.

Table 3.

Radiographic data and statistical comparisons

| Item | Pre-operative | Initial follow-up | Final follow-up | Initial correction | Final correction | Loss correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior body height (mm) | 12.3 ± 4.8ab | 28.9 ± 4.0ac | 26.5 ± 4.3bc | 16.6 ± 6.9 | 14.2 ± 7.2d | 2.3 ± 1.3 |

| Posterior body height (mm) | 24.8±3.1ab | 30.6±3.3a | 30.3±3.2b | 5.8±3.0 | 5.5±3.2 | 0.3±0.1 |

| Lateral Cobb’s angle | 28.6°±9.9°ab | 5.0°±3.0°ac | 10.1°±7.9°bc | 23.6°±8.5° | 18.4°±6.9°d | 5.1°±5.5° |

| Wedge angle | 22.6°±6.8°ab | 3.1°±4.1°a | 4.0±5.5°b | 19.5°±8.8° | 18.6°±9.7° | 0.8±2.0° |

Significant difference: apre-operative vs. initial follow-up; bpre-operative vs. final follow-up; cinitial follow-up vs. final follow-up

dSignificant difference between initial and final corrections

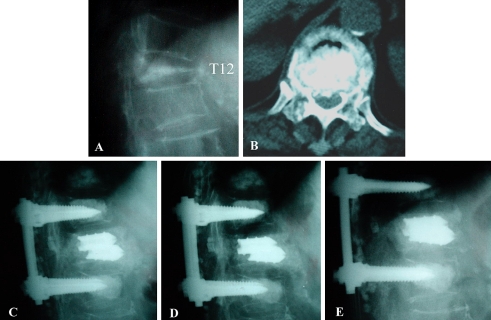

Fig. 4.

A 71-year-old female with L1 stage III Kümmell’s disease with Frankel C received manual reduction and TpBA with short segment posterior fixation. The preoperative plain anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) views show L1 Kümmell’s disease with kyphosis. The CT scan (c) shows canal encroachment. The d 1 month and e, f 24 months postoperative radiographs show good restoration. She was free of symptoms at the final visit with Frankel E

Fig. 5.

A 83-year-old female with T12 stage III Kümmell’s disease with Frankel C received manual reduction and TpBA with short segment posterior fixation. The preoperative plain lateral (a) and CT scan (b) views show T12 Kümmell’s disease cord compression. The initial (c), 1 month (d) and 75 months (e) postoperative lateral radiographs show good restoration. She walked independently at the final visit with Frankel E

Indirect evidence showed that stability of the construct was maintained well. Fusion rate of posterior fusion after short segment fixation was not reported because there was no second look. Throughout the examination of all the final radiographs, neither TpBA dislodgement nor posterior implant failure or migration was noted. No holo lucency sign around the TpBA was noted in any case.

Discussion

Stage III Kümmell’s disease was successfully treated via a posterior approach by manual reduction, short-segment fixation and body reconstruction with TpBA. Manual reduction and TpBA has been known to be successful in treating acute non-osteoporotic burst fractures [15]. In this study, manual reduction was successfully performed, and posterior body reinforcement with TpBA was applied to restore and maintain the vertebral height in chronic osteoporotic stage III Kümmell’s disease, and to prevent implant failure after short-segment fixation. Our series demonstrated a relatively low complication rate with no implant failures. Matched with 81% in P1–P2 group by Denis pain scale, the present method may be a new option to treat stage III Kümmell’s disease.

Because this present study derives from a retrospective analysis, its limitations should be mentioned. Limited case number in stage III Kümmell’s disease is the major reason not to do a prospective study and use a matched control group. Evaluation was not blinded in this study which would impart observer bias to the final report; however, since TpBA was clearly visible in radiograms, a completely blinded evaluation of radiographic parameters would be impossible. The clinical results were evaluated by the authors, which was not blinded.

After exclusion of case reports on just 1–4 patients and conference abstracts [24–35], studies in the English literature on surgical treatment of stage III Kümmell’s disease [9–11, 14, 36–38] have been summarized in Table 4. Operations using various fixation methods and body reconstruction tended to improve neurological defects. However, the complication rates varied from being negligible to as high as 60% by Rhee et al. [32] and 70% by Nguyen et al. [11]. Compared with literature reports, the present study shares many similarities, e.g. insidious development of neurologic symptoms, frequent location in the thoracolumbar junction, and post-operative recovery of neural function. The unique technique of the present report includes manual reduction and posterior body reconstruction with TpBA and short-segment fixation. No laminectomy is needed; no hook is used and the operation time and blood loss is relatively short compared to other reports. All preoperative kyphosis and anterior body height loss were corrected and well maintained.

Table 4.

Comparisons among various operations for stage III Kümmell’s disease

| Author | Case no. | Operation procedures | Mean follow-up | Levels | OP time (min) Blood loss (cc) | Kyphosis (°) (pre-op→initial→final) | Function Evaluation (pre-op → final) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shikata et al. [38] | 7 | PD + PI | 24.7 M | T11–L4 | ?? | 33° → ? → 13° | Frankel: 2B5C→2D5E |

| Kaneda et al. [10] | 22 | AD + AI | 34 M | T12–L3 | ?387 cc | 27.8°→13.3°→14.8° | ? |

| Baba et al. [36] | 27 | 7: AD + AI 20: PD + LSPF |

44 M | T11–L5 | AD + AI 270 min 530 cc PD + LSPF198 min 270 cc |

AD + AI 23°→13°→20° PD + LSPF 24°→9°→13° |

6: excellent 15: good 4: fair 2: poor |

| Mochida et al. [9] | 22 | 9: AD+AI13: PD + PI | 35 M | T7–L4 | ?? | ? → ? → ? | Frankel AD+AI 7C2D → 5D4E PD + PI? → 2C3D8E |

| Kim et al. [37] | 14 | PD + LSPF | 36 M | T12–L1 | 217 min 682 cc | 22.6°→4.4°→6.8° | Frankel: 7C11E→7D2D |

| Nguyen et al. [11] | 10 | 8: PD + LSF 1: AD + AI 1: AD + LSPF |

16 M | T8–L3 | ?? | 28°→11.9°→19.9° | Frankel: 3C 7D→1C6D3E |

| Matsuyama et al. [14] | 5 | PD + SSPF + CP | 30 M | T10–L4 | 120 min 181 cc |

? → ? → ? | JOA Score 17.8 → 26 |

| Current authors | 24 | Current method | 48 M | T10–L2 | 70 min 150 cc |

28.6°→ 5.0°→ 10.1° | Frankel: 6C9D6E→20E1D |

AD Anterior decompression; AI anterior instrumentation; CP biodegradable calcium phosphate; LSPF long-segment posterior fixation; PD posterior decompression; PI posterior instrumentation; SSPF short-segment posterior fixation

Kyphoplasty or open kyphoplasty were not tried by the authors. Because the surrounding vertebral cortex has already been compromised in stage III Kümmell’s disease, inserted cement can easily leak out of the vertebral body, including maybe into the spinal canal, which is potentially very dangerous. That is more likely if collapsed vertebral body was reduced by manual reduction, as in Figs. 4, 5. That’s why the authors hesitate to do kyphoplasty for stage III Kümmell’s disease.

Long-term adjacent compression fracture rate was 14.3% after TpBA reconstruction and short-segment fixation, which is close to the natural course documented for an osteoporotic spine. It has been reported that the new compression fracture rate in the subsequent year was 12% in patients with one previous compression fracture, and 24% in those with two previous fractures [39]. When kyphoplasty is performed, there is conflicting data reported for the incidence of subsequent fractures, ranging from 3 to 29% [40, 41]. Kaneda et al. [10] reported 18% subsequent fractures after anterior procedures with a mean 34-month follow-up. Compared to results reported for other procedures in the literature, TpBA reinforcement with short-segment fixation did not overly increase adjacent compression fractures.

Short-segment fixation with manual reduction and reinforcement of TpBA was an effective and safe method to treat stage III Kümmell’s disease. With an average 4-year follow-up, we showed that manual reduction could safely decompress the spinal canal and restore anatomic alignment and TpBA with short-segment fixation could ensure restoration of vertebral height, prevent implant failure, and lead to clinical success.

References

- 1.Brower AC, Downey EF. Kümmell disease: report of a case with serial radiographs. Radiology. 1981;141(2):363–364. doi: 10.1148/radiology.141.2.7291557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eenenaam DP, el-Khoury GY. Delayed post-traumatic vertebral collapse (Kümmell’s Disease): case report with serial radiographs, computed tomographic scans, and bone scans. Spine. 1993;18(9):1236–1241. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199307000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osterhouse MD, Kettner NW. Delayed posttraumatic vertebral collapse with intravertebral vacuum cleft. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25(4):270–275. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2002.123164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grados F, Depriester C, Cayrolle G, Hardy N, Deramond H, Fardellone P. Long-term observations of vertebral osteoporotic fractures treated by percutaneous vertebroplasty. Rheumatology. 2000;39(12):1410–1414. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.12.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen ME, Evans AJ, Mathis JM, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ, Dion JE. Percutaneous polymethylmethacrylate vertebroplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral body compression fractures: technical aspects. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(10):1897–1904. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieberman IH, Dudeney S, Reinhardt MK, Bell G. Initial outcome and efficacy of Kyphoplasty in the treatment of painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Spine. 2001;26(14):1631–1638. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200107150-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li KC, Wong TU, Kung FC. Staging of Kümmell’s disease. J Musculoskel Res. 2004;8:43–55. doi: 10.1142/S0218957704001181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehmer SM, Keppler L, Biscup RS, Enker P, Miller SD, Steffee AD. Posterior transvertebral osteotomy for adult thoracolumbar kyphosis. Spine. 1994;19(18):2060–2067. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199409150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mochida J, Toh E, Chiba M, Nishimura K. Treatment of osteoporotic late collapse of a vertebral body of thoracic and lumbar spine. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14(5):393–398. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneda K, Asano S, Hashimoto T, Satoh S, Fujiya M. The treatment of osteoporotic post-traumatic vertebral collapse using the Kaneda device and a bioactive ceramic vertebral prosthesis. Spine. 1992;17(8 Suppl):S295–S303. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199208001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen HV, Ludwig S, Gelb D. Osteoporotic vertebral burst fractures with neurologic compromise. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(1):10–19. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200302000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aebi M, Etter C, Kehl T, Thalgott J. The internal skeletal fixation system: a new treatment of thoracolumbar fractures and other spinal disorders. Clin Orthop. 1988;227:30–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer DL, Rodgers WB, Mansfield FL. Transpedicular instrumentation and short-segment fusion of thoracolumbar fractures: a prospective study using a single instrumentation system. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(6):499–506. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199509060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuyama Y, Goto M, Yoshihara H, Tsuji T, Sakai Y, Nakamura H, et al. Vertebral reconstruction with biodegradable calcium phosphate cement in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture using instrumentation. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17(4):291–296. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000097253.54459.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li KC, Hsieh CH, Lee CY, Chen TH. Transpedicle body augmenter: a further step in treating burst fractures. Clin Orthop. 2005;436:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen HH, Wang WK, Li KC, Chen TH. Biomechanical effects of the body augmenter for reconstruction of the vertebral body. Spine. 2004;29(18):E382–E387. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000139308.65813.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li KC, Chen HH, Li A, Hsieh CH. Safe zone for application of transpedicle body augmenter. J Orthop Surg Taiwan. 2004;21:125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rampersaud YR, Simon DA, Foley KT. Accuracy requirements for image-guided spinal pedicle screw placement. Spine. 2001;26(4):352–359. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniaux H, Seykora P, Genelin A, Lang T, Kathrein A. Application of posterior plating and modifications in thoracolumbar spine injuries: indication, techniques and results. Spine. 1991;16(3 Suppl):S125–S133. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199103001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuklo TR, Polly DW, Owens BD, Zeidman SM, Chang AS, Klemme WR. Measurement of thoracic and lumbar fracture kyphosis: evaluation of intraobserver, interobserver, and technique variability. Spine. 2001;26(1):61–65. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verlaan JJ, Kraats EB, Walsum T, Dhert WJ, Oner FC, Niessen WJ. Three-dimensional rotational X-ray imaging for spine surgery: a quantitative validation study comparing reconstructed images with corresponding anatomical sections. Spine. 2005;30(5):556–561. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000154650.31781.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frankel HL, Hancock DO, Hyslop G, Melzak J, Michaelis LS, Ungar GH, et al. The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia: Part I. Paraplegia. 1969;7(3):179–192. doi: 10.1038/sc.1969.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denis F, Armstrong GW, Searls K, Matta L. Acute thoracolumbar burst fractures in the absence of neurologic deficit: a comparison between operative and nonoperative treatment. Clin Orthop. 1984;189:142–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arciero R, Leung K, Pierce J. Spontaneous unstable burst fracture of the thoracolumbar spine in osteoporosis: a report of two cases. Spine. 1989;14(1):114–117. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198901000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasegawa K, Homma T, Uchiyama S, Takahashi HE. Osteosynthesis without instrumentation for vertebral pseudarthrosis in osteoporotic spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1997;79(3):452–456. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B3.7457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heggeness MH. Spine fracture with neurologic deficit in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3(4):215–221. doi: 10.1007/BF01623679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan PA, Orton DF, Asleson RJ. Osteoporosis with vertebral compression fractures, retropulsed fragments and neurologic compromise. Radiology. 1987;165(2):533–535. doi: 10.1148/radiology.165.2.3659378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kempinsky WH, Morgan PP, Boniface WR. Osteoporotic kyphosis with paraplegia. Neurology. 1958;8(3):181–186. doi: 10.1212/wnl.8.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korovessis P, Maraziotis T, Piperos G, Spyropoulos P. Spontaneous burst fracture of the thoracolumbar spine in osteoporosis associated with neurologic impairment: a report of seven cases and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 1994;3(5):286–288. doi: 10.1007/BF02226581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lafforgue P, Daumen-Legre V, Schiano A, Peragut JC, Acquaviva PC. Neurologic complications of osteoporotic vertebral compression: three new cases and critical analysis of the literature. Rev Rheum Mal Osteoartic. 1990;57(9):619–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maruo S, Tatekawa F, Nakano K. Paraplegia caused by vertebral compression fractures in senile osteoporosis. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1987;125(3):320–323. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1044733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhee JM, Hu SS, Beuff HU et al (1998) The results of spinal reconstructive surgery in the elderly (paper no. 16). Presented at the Scoliosis Research Society Meeting, St. Louis

- 33.Salomon C, Chopin D, Benoist M. Spinal cord compression: an exceptional complication of spinal osteoporosis. Spine. 1988;13(2):222–224. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198802000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka S, Kubota M, Fujimoto Y, Hayashi J, Nishikawa K. Conus medullaris syndrome secondary to an L1 burst fracture in osteoporosis. Spine. 1993;18(14):2131–2134. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310001-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoo J, Hillebrand A, Bohlman HH (1998) Functional recovery following surgical treatment of osteopenic vertebral body fractures with resulting neurologic deficit in elderly patients (paper no. 39). Presented at the Scoliosis Research Society Meeting, St. Louis

- 36.Baba H, Maezawa Y, Kamitani K, Furusawa N, Imura S, Tomita K. Osteoporotic vertebral collapse with late neurological complications. Paraplegia. 1995;33(5):281–289. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim KT, Suk KS, Kim JM, Lee SH. Delayed vertebral collapse with neurological deficits secondary to osteoporosis. Int Orthop. 2003;27(2):65–69. doi: 10.1007/s00264-002-0418-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shikata J, Yamamuro T, Iida H, Shimizu K, Yoshikawa J. Surgical treatment for paraplegia resulting from vertebral fractures in senile osteoporosis. Spine. 1990;15(6):485–489. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199006000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindsay R, Silverman SL, Cooper C, Hanley DA, Barton I, Broy SB, et al. Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA. 2001;285(3):320–323. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.3.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fribourg D, Tang C, Sra P, et al. Incidence of subsequent vertebral fracture after kyphoplasty. Spine. 2004;29:2270–2276. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000142469.41565.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin EP, Ekholm S, Hiwatashi A, Westesson PL. Vertebroplasty: cement leakage into the disc increases the risk of new fracture of adjacent vertebral body. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(2):175–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]