Abstract

Aggressive surgical management of spinal metastatic disease can provide improvement of neurological function and significant pain relief. However, there is limited literature analyzing such management as is pertains to individual histopathology of the primary tumor, which may be linked to overall prognosis for the patient. In this study, clinical outcomes were reviewed for patients undergoing spinal surgery for metastatic breast cancer. Respective review was done to identify all patients with breast cancer over an eight-year period at a major cancer center and then to select those with symptomatic spinal metastatic disease who underwent spinal surgery. Pre- and postoperative pain levels (visual analog scale [VAS]), analgesic medication usage, and modifed Frankel grade scores were compared on all patients who underwent surgery. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to assess risks for complications. A total of 16,977 patients were diagnosed with breast cancer, and 479 patients (2.8%) were diagnosed with spinal metastases from breast cancer. Of these patients, 87 patients (18%) underwent 125 spinal surgeries. Of the 76 patients (87%) who were ambulatory preoperatively, the majority (98%) were still ambulatory. Of the 11 patients (13%) who were nonambulatory preoperatively, four patients were alive at 3 months postoperatively, three of which (75%) regained ambulation. The preoperative median VAS of six was significantly reduced to a median score of two at the time of discharge and at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively (P < 0.001 for all time points). A total of 39% of patients experienced complications; 87% were early (within 30 days of surgery), and 13% were late. Early major surgical complications were significantly greater when five or more levels were instrumented. In patients with spinal metastases specifically from breast cancer, aggressive surgical management provides significant pain relief and preservation or improvement of neurological function with an acceptably low rate of complications.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Estrogen, Metastases, Prognosis, Spine surgery

Introduction

In North American and Western European women, carcinoma of the breast is the most common malignancy and the second most common cause of cancer-related death [7, 12, 21]. In women with metastatic breast cancer, skeletal involvement is very frequent, with reported incidences between 47 and 85% in autopsy series and 69–80% when defined radiographically [7, 12, 16, 21, 31]. About one-third of these spinal metastases become symptomatic, causing intractable pain, neurological deficits, and/or biomechanical instability requiring surgical treatment [19, 34]. In patients with metastatic spinal tumors, the histopathology of the primary cancer has frequently been shown to have significant prognostic value [2, 3, 26, 28, 34, 37]. However, despite the paramount importance of primary tumor histopathology, few studies in the literature on spinal metastases are pathology specific. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to review the outcomes of a large number of patients undergoing spinal surgery for metastatic breast cancer at a major cancer center.

Methods

Patient population and selection criteria

A retrospective review was performed of all patients treated at, The University of Texas, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center from June 1, 1993 to June 30, 2001 for histologically confirmed breast cancer with metastases to the spine. During this period, a total of 16,977 patients were diagnosed with breast cancer at the institution, as identified through a search of the tumor registry. During the same time period, there were 2,641 patients diagnosed with spinal metastases from a variety of primary cancer types, 479 of which were from breast cancer. Eighty-seven of these patients (18%) underwent surgery for spinal metastases.

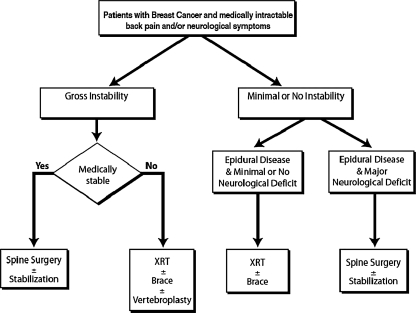

The selection criteria for undergoing surgical intervention for spinal metastases from breast cancer required all patients to be deemed medically stable enough to undergo the proposed surgery and to have at least one of the following conditions: (1) obvious spinal deformity with intractable pain, (2) retropulsed bone or disc fragment in the spinal canal causing significant spinal cord compression or (3) prior irradiation of the site of progressive spinal involvement with cord compression or (4) medically intractable mechanical, local, or radicular pain. Patients excluded from surgery were those with end-stage disease (e.g., estimated survival <3 months), absence of biomechanical instability, significant spinal deformity, or major neurological deficit, and those who refused surgery (Fig. 1). Life expectancy was estimated by the medical oncology service using multiple characteristics of the individual patient, including but not limited to: histopathology, age, functional status, concomitant comorbidities, presence of untreatable visceral metastases, hormone receptor status, response to adjuvant therapy, quality of life issues, and presence of psychosocial problems. These patients, when treated, underwent radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy/hormonal therapy. Patients not undergoing surgery, when opting for additional treatment, underwent radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy/hormonal therapy. Eighty-seven patients met the above criteria and constituted the study group for this paper. These patients underwent a total of 125 spinal operations over the duration of follow up.

Fig. 1.

Proposed algorithm for treatment of patients with symptomatic spinal metastases from breast cancer

Data collection

Medical records were retrospectively reviewed for demographic, clinical, radiographic, and histological data. Data collected regarding the primary breast cancer included dates of initial diagnosis, surgery, radiation and/or chemotherapy/hormonal therapy and the presence of other metastases at the time of spinal surgery. Clinical data collected regarding the spinal metastases included the presenting neurological signs and symptoms as quantified by the Frankel grading system [15, 20]. Also, the severity of pain was assessed using a numerical pain rating scale (0–10), which is a modification of the visual analog scale (VAS) [10, 42]. The type of pain medication used was classified from 1 to 5, as previously reported by the senior author (Table 1) [20].

Table 1.

Classification of analgesic medications used in 87 patients with breast cancer metastases to the spine

| Category | Medication |

|---|---|

| 1 | None |

| 2 | Acetamionophen, nonsteroidal antiinflammatories |

| 3 | Codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, propoxyphene hydrochloride |

| 4 | Morphine SR/IR, fentanyl TD, oxycodone SR/IR |

| 5 | Intravenous narcotics |

IR instant release, SR slow release, TD transdermal

Neuroanatomy and neuroimaging

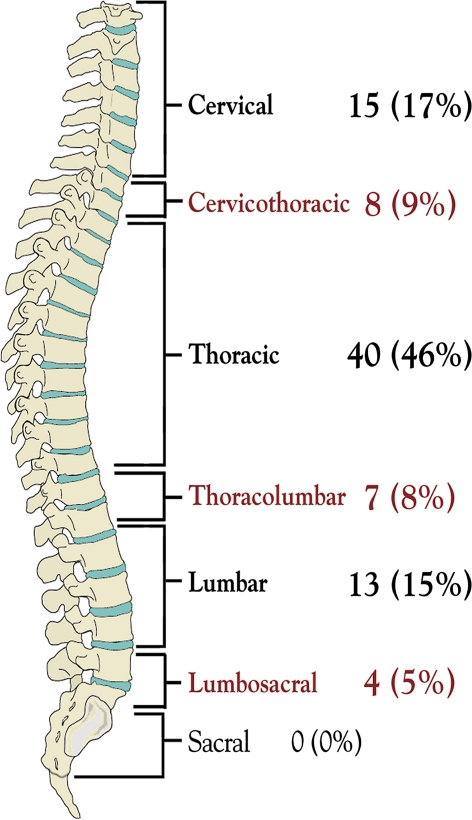

The anatomical location of the spinal lesions was assessed using magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and plain X-rays. The total number of vertebral segments involved with tumor was noted and grouped into categories (e.g., single lesion, two lesions, and three or more lesions) for analysis of survival and complications. Metastatic spinal lesions requiring surgery were classified as follows: cervical (C, C1-6), cervicothoracic (CT, C7-T1), thoracic (T, T2-11), thoracolumbar (TL, T12-L1), lumbar (L, L2-4), or lumbosacral (LS, L5-S1). Lesions encompassing two or more of these regions such as cervicothoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbosacral regions were considered to be at a junctional level.

Pathological data

All patients had histologically verified breast cancer treated at M. D. Anderson. The original diagnosis was often made at a referring institution. All available pathology slides from outside hospitals were reviewed at M. D. Anderson to confirm the diagnosis. A review of the hospital charts and pathology reports for each patient was performed to determine the original histopathological tumor type, the degree of involvement of lymph nodes by the tumor, and whether the tumor expressed estrogen or progesterone receptors.

Perioperative data and surgical approach

Operative data included the type of surgical approach, anatomical levels of disease and levels of instrumentation, type and presence of fusion or instrumentation, estimated blood loss, and amount of blood transfused. No patient received preoperative arterial embolization.

The anatomical location and extent of disease dictated the surgical approach with intention to remove all tumorous tissue when possible, as previously published by Fourney and Gokaslan (Fig. 2) [13]. An anterior or anterolateral approach was used if the disease was primarily located anteriorly in the vertebral body. A posterior or posterolateral approach was used when the disease was primarily posterior or posterolateral. A bipedicular approach was used for circumferential tumors or in regions of the spine that were difficult to access anteriorly (C1-2, T2-4, and L5-S1). A combined anterior–posterior simultaneous approach was used if the disease involved the lateral elements of the spinal column with significant paraspinal extension. An anterior–posterior staged approach was used for disease located at junctional zones with preexisting spinal deformity. Laminectomy for palliative treatment of anterior spinal cord decompression was not offered to patients.

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of tumor growth patterns and the indicated surgical approaches: anterior or anterolateral approach (a), posterior (b-i) or posterolateral (b-ii) approach, posterior bipedicular approach (c), combined anterior–posterior simultaneous approach (d). Borrowed with permission from Journal of Neurosurgery

In patients with tumor-related spinal instability, posterior arthrodesis was performed using allograft bone, and posterior stabilization was achieved by implanting instrumentation. The method of posterior stabilization varied depending on the anatomical location of the tumor. Lateral mass screws and plate or rod constructs were used in the cervical spine. Rods with either pedicle screws or hooks were used in the thoracic and lumbar spine. In tumors involving the lumbosacral junction, posterior stabilization was performed using the modified Galveston spinopelvic fixation technique as previously described [25]. Extensive tumors involving both the anterior and posterior aspects of the spine were approached and stabilized either from both anterior and posterior or by using a lone posterior transpedicular vertebrectomy technique as previously described [1]. In the cervical and upper thoracic spine, anterior stabilization was achieved by using the coaxial double-lumen methylmethacrylate technique (with anterior plating) as previously described [35]. Anterior stabilization of the mid- and lower thoracic and lumbar spine was achieved by using methylmethacrylate or titanium spacers with an anterolateral plate.

All intraoperative complications and those that occurred within the first 30 days postoperatively were considered early complications. Those that occurred after 30 days were considered late complications. Complications were classified as major or minor according to McDonnell et al. [33]. The postoperative length of hospital stay (LOS) was recorded for each patient and included time spent on the rehabilitation service.

Postoperative (follow-up) data

Details of patient evaluation at the time of discharge and at around 1, 3, 6 months, and 1 year after surgery were reviewed. Comparisons were made between preoperative and postoperative Frankel grade, VAS pain scores, and pain medication usage. Follow-up spine MR images and plain X-rays were also evaluated. Clinical or radiographic evidence of local or distant metastatic tumor recurrence in the spine was noted. Tumor growth at the operation site was considered local recurrence, and tumor growth at another site in the spine was considered distant recurrence.

Statistical methods

The frequencies and descriptive statistics of demographic and clinical variables were recorded for the patients in this study. The chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables, and Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney test were used for continuous and ordinal variables, as appropriate. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the paired outcomes at various follow-up points. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate postoperative survival and survival time after primary breast cancer diagnosis [27]. Univariate and multivariate predictors of overall survival were assessed using the Cox proportional hazards model. Variables significant at P < 0.25 in the univariate analysis were tested through a backward stepwise selection process for their independent effect on overall survival. Rate ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed. The logistic regression model was used to determine factors associated with the development of major early postoperative complications. Odds ratios and their 95% CIs were computed. A P value ≤0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of 87 patients with breast cancer who underwent surgery for spinal metastases

| Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 53 years | |

| Range | 35–84 years | |

| Median time between primary breast cancer diagnosis and first metastatic spine surgery | 3.9 years | |

| Original breast cancer histopathology | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 74 (85) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 13 (15) | |

| Original hormone receptor statusa | ||

| ER positive | 46 (72) | |

| PR positive | 32 (56) | |

| Original lymph node statusa | ||

| Positive | 44 (68) | |

| Other sites of metastases at time of spine surgery | ||

| No other metastases (spine only) | 29 (33) | |

| Skeletal (skull, ribs, pelvis, longbones) | 53 (61) | |

| Liver | 17 (19) | |

| Lungs | 12 (14) | |

| Brain | 6 (7) | |

| Pre-op visual analog pain score median (range) | 6 (1–10) | |

| Pre-op pain medication score median (range) | 4 (1–5) | |

| Radicular | 34 (39) | |

| Axial | 31 (36) | |

| Local | 22 (25) | |

| Frankel grade at presentation | ||

| E | 52 (60) | |

| D | 24 (28) | |

| C | 8 (9) | |

| B | 1 (1) | |

| A | 2 (2) | |

| Pre-op adjuvant spine treatment | ||

| Both chemotheraphy and radiation | 40 (46) | |

| Chemo/hormonal only | 39 (45) | |

| None | 5 (6) | |

| Spinal radiation alone | 3 (3) | |

| Post-op adjuvant spine treatment | ||

| Chemotherapy only | 43 (50) | |

| Both radiation and chemotherapy | 26 (30) | |

| None | 8 (9) | |

| Spinal radiation only | 1 (1) | |

| Unknown | 9 (10) | |

aAmong patients with available information

Number and location of spinal metastases

Twenty-six patients (30%) had tumor involvement of one vertebral body, as diagnosed by MR imaging criteria. The remaining 61 patients (70%) had multiple locations of metastases within the spinal column. Twenty-two (25%) had 2, 23 (26%) had 3, and 16 (18%) had 4 or more vertebral bodies involved with tumor material. The anatomical distribution of spinal metastases requiring surgical treatment is illustrated in Fig. 3. Figure 4 demonstrates the pre- and postoperative imaging of a selected patient undergoing such surgery.

Fig. 3.

Anatomical distribution of spinal metastases requiring surgical treatment

Fig. 4.

Images of patient with breast cancer metastatic to T9, T10 and T11. Preoperative sagittal T2-weighted (a) and axial T1-weighted (b) MR images illustrate metastatic disease with spinal cord compression. Anterior–posterior (c) and lateral (d) plain films showing spinal reconstruction following decompressive surgery

Surgical procedures

The details of all surgical procedures are shown in Table 3. A total of 125 procedures were performed in 87 patients. The median EBL was 475 ml (range, 50–6,000 ml) for the “anterior-only” approach, 500 ml (range, 50–3,500 ml) for the “posterior-only” approach, 1,350 ml (range, 200–4,000 ml) for the “combined simultaneous anterior–posterior” approach, and 2,500 ml (range, 550–5,500 ml) for the “combined staged anterior–posterior” approach. For the combined staged procedures, the EBLs of each stage were added together. The EBL for the anterior-only approach was not significantly different from the posterior-only approach (P > 0.35). However, EBL was significantly higher during the combined approaches compared with either the anterior or posterior approaches alone (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Surgical procedures performed on 87 patients with breast cancer spinal metastasis (n = 125)

| Surgical approach for all procedures | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior only | 47 | (38) |

| Posterior only | 44 | (35) |

| Combined anterior-posterior simultaneous | 8 | (6) |

| Anterior or posterior portion of staged procedure | 26 | (21) |

| Instrumentation of all procedures | ||

| Incidence of any instrumentation | 115 | (92) |

| Incidence of PMMA (Polymethylmethacrylate) usage | 75 | (60) |

| Blood loss for all procedures | ||

| Median estimated blood loss (ml), (range) | 700 | (50–6,000) |

| Median number of blood transfusions, (range) | 1 | (0–16) |

| Number of vertebral bodies removed per patient | ||

| 0 | 19 | (22) |

| 1 | 43 | (49) |

| 2 or more | 25 | (29) |

| Number of levels instrumented per patient | ||

| 0 | 4 | (5) |

| 3–5 | 53 | (61) |

| 6–10 | 23 | (26) |

| 11–15 | 7 | (8) |

| Indications for subsequent surgery by patient | ||

| Second part of staged surgery | 13 | (15) |

| Tumor recurrence (local or distant) | 20 | (23) |

| Surgical revision of instrumentation | 12 | (14) |

Postoperative neurological function

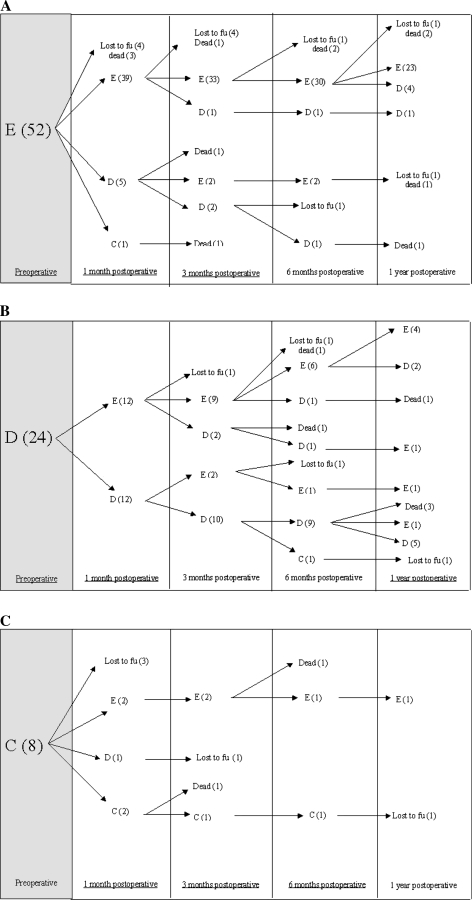

Of the 76 patients (87%) who were ambulatory preoperatively, the majority (98%) were still ambulatory. Of the 11 patients (13%) who were nonambulatory preoperatively, four patients were alive at 3 months postoperatively, three of which (75%) regained ambulation. Tables 4, 5 provide postoperative neurologic function of patients during follow up. Figure 5a–c provides a more detailed account of neurological changes over time. Of note, the majority of patients (85%) maintained or improved their Frankel scores from preoperative to both immediately and up to 1 year after surgery. Two patients with a preoperative Frankel Grade of A died or were lost to follow-up before 1 month postoperative. One patient with a preoperative Frankel grade of B improved to grade C at 1 month postoperative, then was at grade D thereafter.

Table 4.

Frankel grade at l-month postoperative compared with preoperative Frankel grade

| Pre-op Frankel | Post-op Frankel | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | E | D | C | B | A | |

| 45 | E | 39 | 6 | |||

| 24 | D | 12 | 12 | |||

| 5 | C | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 1 | B | 1 | ||||

| 0 | A | |||||

| Total 75 | ||||||

There were 75 patients available to review at 1 month

Table 5.

Frankel grade over time

| Timing from surgery | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-op n (%) | Discharge n (%) | 1 month n (%) | 3 months n (%) | 6 months n (%) | 1 Year n (%) | ||

| Frankel grade | E | 52(60) | 54(64) | 53(71) | 48(74) | 40(71) | 32(71) |

| D | 24(28) | 24(28) | 18(24) | 16(25) | 14(25) | 13(29) | |

| C | 8(9) | 5(6) | 4(5) | 1(2) | 2(4) | 0(0) | |

| B | 1(1) | 1(1) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| A | 2(2) | 1(1) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Total patients | 87(100) | 85(100) | 75(100) | 65(100) | 56(100) | 45(100) | |

Fig. 5.

Detailed postoperative neurological changes over time for patients with Frankel grades E (a), D (b), and C (c), respectively

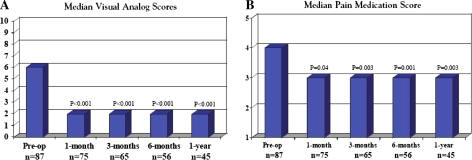

Postoperative pain

A comparison of preoperative and postoperative median VAS scores is illustrated in Fig. 6. The preoperative median VAS was six, whereas the postoperative median VAS was two. This was significantly lower than preoperative pain scores at all time points (P < 0.001). The preoperative median pain medication score was 4 and had dropped to 3 at discharge, where it remained at 1, 3, 6 months, and 1 year after surgery (P < 0.05 for all postoperative time points compared with preoperative).

Fig. 6.

Pre- and postoperative median VAS and pain medication scores during 1 year of follow-up, statistically significant at all time points

Hospital course and complications

The patients’ median length of hospital stay was 11 days (range 1–54 days). Twenty-nine patients (33%) required postoperative rehabilitation. All complications observed in these patients are illustrated in Table 6. Thirty-four of the 87 patients (39%) experienced a total of 39 complications, 26% had major complications and 24% had minor complications, as described by McDonnell [33]. Thirty-four complications occurred early (within 30 days of surgery), whereas five complications occurred late. One patient died within 24 h of surgery due to an intraoperative hypotensive cardiac arrest.

Table 6.

Complications of surgery for spinal metastases in 87 patients (patients can have more than one complication)

| Major complications | Number of patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation failure | 14 (16) | |

| Infection requiring surgery | 3 (3) | |

| Pneumonia | 2 (2) | |

| Othera | 4 (5) | |

| Minor complications | Number of patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| UTI | 7 (8) | |

| Superficial wound infection | 4 (5) | |

| CSF leak requiring lumbar drain | 5 (6) | |

| Otherb | 5 (6) | |

| Major complications by surgical approach | n | Complication (n, %) |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior only | 35 | 4 (11) |

| Posterior only | 31 | 4 (13) |

| Combined-simultaneous | 8 | 2 (25) |

| Combined-staged | 13 | 5 (38) |

| TOTAL | 87 | 15 (17) |

aOther major complications included one patient with deep venous thrombosis, one patient with pulmonary embolism, one patient with myocardial infarction and one patient with acute tubular necrosis

bOther minor complications included one transient confusion, one supraventricular tachycardia, and three pleural effusions

Preoperative irradiation of the operative site was not associated with postoperative wound infection. Instrumentation failure was caused by local and/or distant spinal tumor recurrence in 43% [6] of these patients. Deep wound infections caused instrumentation failure in 21% [3] of these patients, and the remaining five patients (36%) had failure for nonspecific or unclear reasons.

Multiple variables were assessed to determine risk factors for major early complications (Table 6). The only significant factor at the multivariate analysis level was the instrumentation of five or more spinal levels (risk ratio 7.2, 95% CI, 1.5–35.5, P = 0.01) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Univariate and multivariate predictors of major postoperative complications. Data from 87 patients with breast metastasis to the spine

| Variable | Major Complications | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Odds ratioa | 95% CI | P value | Odds ratioa | 95% CI | P value | |

| N (%) | N (%) | |||||||

| Age < 65c | 62 (82) | 14 (18) | 1.0 | – | – | |||

| ≥65 | 10 (91) | 1 (9) | 0.4 | 0.0–3.8 | 0.46 | NI | ||

| Frankle grade | ||||||||

| Ambulatory Eb | 44 (85) | 8 (15) | 1.0 | – | – | |||

| Ambulatory D | 20 (83) | 4 (17) | 1.1 | 0.3–4.1 | 0.89 | |||

| Non- ambulatory (A–C) | 8 (73) | 3 (27) | 2.1 | 0.05–9.5 | 0.35 | NI | ||

| Extent of metastatic disease | ||||||||

| Spine onlyb | 22 (76) | 7 (24) | 1.0 | – | – | NS | ||

| Plus Visceral | 25 (83) | 5 (17) | 0.6 | 0.2–2.3 | 0.05 | |||

| Plus Non-visceral | 25 (89) | 3 (11) | 0.4 | 0.1–1.6 | 0.19 | |||

| Number of spine lesions by MRI | ||||||||

| 1b | 23 (88) | 3 (12) | 1.0 | – | – | |||

| 2 | 17 (77) | 5 (23) | 2.3 | 0.5–10.8 | 0.31 | NI | ||

| 3 or more | 32 (82) | 7 (18) | 1.7 | 0.4–7.2 | 0.49 | |||

| Spine tumor at junctional level | ||||||||

| Nob | 56 (82) | 12 (18) | 1.0 | – | ||||

| Yes | 16 (84) | 3 (16) | 0.9 | 0.2–3.5 | 0.85 | NI | ||

| Spinal tumor location | ||||||||

| Non-cervicalb | 51 (80) | 13 (20) | 1.0 | – | – | |||

| Cervical | 21 (91) | 2 (9) | 0.4 | 0.1–1.8 | 0.22 | NS | ||

| Preoperative irradiation to operative site | ||||||||

| Nob | 39 (80) | 10 (20) | 1.0 | – | – | |||

| Yes | 33 (87) | 5 (13) | 0.6 | 0.2–1.9 | 0.38 | NI | ||

| Surgical approach | ||||||||

| Single (Ant or post)b | 58 (88) | 8 (12) | 1.0 | – | – | |||

| Combined | 14 (67) | 7 (33) | 3.6 | 1.1–11.7 | 0.03 | NS | ||

| Use of spinal instrumentation | ||||||||

| Nob | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | – | – | |||

| Yes | 67 (82) | 15 (18) | 817.2 | Wide | 0.80 | NI | ||

| Estimated blood loss | ||||||||

| <750b | 44 (94) | 3 (6) | 1.0 | – | – | |||

| 750–2,500 | 21 (81) | 5 (19) | 3.5 | 0.8–16.0 | 0.11 | |||

| ≥2,500 | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | 9.8 | 1.7–54.7 | 0.01 | NS | ||

| Number of vertebral bodies removed | ||||||||

| 0 or 1c | 55 (89) | 7 (11) | 1.0 | – | – | |||

| 2 or more | 17 (68) | 8 (32) | 3.7 | 1.2–11.7 | 0.03 | NS | ||

| Use of PMMA | ||||||||

| Nob | 23 (92) | 2 (8) | 1.0 | – | – | |||

| Yes | 49 (79) | 13 (21) | 3.0 | 0.6–14.6 | 0.16 | NS | ||

| Maximum number of spinal levels instrumented | ||||||||

| <5b | 43 (94) | 3 (6) | 1.0 | |||||

| ≥5 | 29 (71) | 12 (29) | 5.9 | 1.5–22.9 | 0.01 | 7.2 | 1.5–35.5 | 0.01 |

CI confidence interval, NI not included, NS not significant

aOdds ratio > 1.0 indicates a higher risk of complications, <1.0 indicates a lower risk of major complications, odds ratio of 1.0 indicates a similar risk of major complications. Logistic regression analysis used

bReferent group (group than others are compared to)

Tumor recurrence

The median overall duration of follow up was 13 months (range < 1–70 months). Patients remaining alive were followed for a median of 10 months (range < 1–70 months). A total of 20 patients experienced tumor recurrences: seven were local, ten were distant, and three patients had both local and distant recurrences. Treatment for recurrence included surgery in 11 patients and radiation therapy in nine patients.

Survival

The median survival interval of patients after the original breast cancer diagnosis was 80 months (6.6 years; 95% CI 5.4–7.7 years). The patient survival rate after the date of primary breast cancer diagnosis was 96% at 1 year, 81% at 3 years, and 69% at 5 years. The patients’ median survival time after their first spinal surgery was 21 months (95% CI 16–27 months). The survival rate of patients after their first spinal surgery was 62% at 1 year, 44, 33% at 3 years and 24% at 5 years.

Discussion

The incidence of breast cancer has continued to rise in the United States over the last few decades. In patients with metastatic breast cancer, skeletal involvement is very frequent, with an incidence of 47–85% in autopsy series and 69–80% when defined radiographically [7, 12, 16, 21, 31, 43]. Among reported clinical series of spinal epidural metastases, breast cancer is again common, accounting for 9–40% of all cases [11, 20, 22, 24, 28, 44–47, 49, 50]. Despite the high incidence of breast cancer metastases to the spine, few series in the literature on metastatic spinal disease deal specifically with metastases from breast cancer. The histopathology of the primary cancer has significant implications for treatment and defines the tumor’s radiosensitivity, chemosensitivity, vascularity, growth pattern as well as the prognosis [2, 3, 26, 28, 34, 37]. Because of the large number of cancer patients treated at M. D. Anderson, a pathology-specific study of a large number of patients is feasible. Although spinal metastases are most often clinically silent, they can often cause significant morbidity, pain, and neurological dysfunction that may adversely affect quality of life.

The ideal treatment of breast metastasis requires a multidisciplinary approach and treatments including medical treatment, radiotherapy, and surgery [3, 34]. Medical therapies include systemic chemotherapy/hormonal therapy and medications specific for spinal metastases, such as steroids, analgesics, and bisphosphonates [6, 12, 31, 34, 41]. Bisphosphonates are highly effective in reducing bone pain, hypercalcemia and pathological fractures, and they are frequently used at our institutions [23, 30, 31]. For patients with localized bone pain that has not responded to systemic therapy and analgesics, external beam irradiation (30 Gy in ten fractions) is the treatment of choice and usually provides good pain relief [29, 31, 32, 40]. Spinal stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is a relatively new radiation treatment option for spinal metastases that not undergone rigorous, long-term investigation, but may have advantages over conventional XRT for the treatment of metastatic spine disease. Interestingly, a number of studies involving SRS for metastatic spine disease have provided encouraging results in relation to pain control and improvement in neurological function [9, 17]. In addition, percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty have been shown to be safe and effective techniques for treating intractable pain secondary to pathological vertebral fractures of metastatic spine disease [14].

Indications for surgery

The exact indications for surgery in patients with metastatic spine disease from breast cancer are controversial [8], although it is generally agreed that the surgery is palliative, not curative. Despite the efficacy of spinal radiotherapy, there are clinical situations in which surgical intervention should take precedence. Assuming the overall medical condition of the patient is suitable to tolerate the proposed operation and the patient does not have a limited life expectancy (<3 months) (Fig. 1), patients may benefit significantly from surgery, as has been shown in a prospective, randomized clinical trial by Patchell et al. [39]. Generally, surgical indications include: progressive neurological deficits due to significant bone or disc fragment in the spinal canal, mechanical instability, deformity, radiation resistant tumors or tumors that progress despite undergoing maximal radiation dosages, and medically intractable pain [29].

One of the most important reasons surgical resection of spinal metastases in patients with breast cancer has been promoted is as a means to preserve or restore neurological function (Table 8) [5, 20, 25, 35–37, 45, 46, 50, 52]. Because patients with breast cancer have a relatively long life expectancy compared with patients who have other types of cancer, they form a subset in which aggressive surgical intervention should be strongly considered. As evident within this series, a large proportion of patients maintained and even improved their Frankel grade postoperatively with preservation of this benefit up to 1 year or until death (Fig. 5a–c). There are likely multiple factors that contribute to maintenance or improvement of Frankel grade in such patients, but two possible explanations seem most plausible. Firstly, it is likely that neurological function improved or was maintained in cases where surgical decompression directly alleviated neural compression by mass lesions, retropulsed bone, or tumor-induced deformity. Secondly, in patients with mechanical pain due to tumor-induced instability, internal fixation may have allowed a greater proportion of patients to ambulate by decreasing pain with movement, functioning improving their Frankel grades. Such explanations are merely speculative in such a retrospective study. However, our outcomes do mirror the results of the surgical arm in the study by Patchel et al., which showed a lasting maintenance or regained ability to ambulate in patients with decompressive surgery for vertebral metastases that was significantly better than for similar patients undergoing XRT alone.

Table 8.

Results of treatment of metastatic spine disease by vertebral body resection and stabilization

| Author | Year | Total patients | Patients with breast CA primary | Percentage of all patients with postoperative neurological improvement | Percentage of all patients with post-op reduction in pain | Complication rate | Mortality rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sundaresan [50]a | 1985 | 101 | 14 (14%) | 70% | 85%, not quatified | 10% | 8% |

| Siegal [47]b | 1985 | 54 | 7 (13%) | 80% were ambulatory post-op compared to 28% pre-op 93% were continent post-op compared to 51% pre-op | 91% | 11% | 7% |

| Sundaresan [49]c | 1991 | 54 | 5 (9%) | 100% | 90% | 15% | 6% |

| Hosono [23] | 1995 | 84 | 12 (14%) | 81% | 94% | ||

| Enkaoua [13] | 1997 | 71 | 0 (0%) | ||||

| Klekamp [27] | 1998 | 101 | 17 (17%) | 46.8% improved gait and motor power for 3 months | 68% | 16% | 13%, 4.4%d |

| Gokaslan [19] | 1998 | 72 | 10 (14%) | 78% | 92% | ||

| Weigel [50] | 1999 | 76 | 16 (21%) | 58% improved by at least 1 Frankel grade | 89% | 19% | |

| Sinardet [48] | 2000 | 152 | 28 (18%) | 56% increased motor ability, 51% of patients with sphincter dysfunction improved | 65%e | N/R | 9%,1 month |

| Hatrick [21] | 2000 | 42 | 17 (40%) | 69% gained improvement in neurological deficit 78% improved their abilty to ambulate | 90% | ||

| Tomita [52] | 2001 | 61 | 16 (26%) | 74% improved by at least 1 Frankel grade 60% of patients with bladder dysfunction regained voluntary control | 80% | N/R | N/R |

aIncluded nine patients with primary bone tumors

b54 Patients in series underwent vertebral body resections. Another 24 patients in this series underwent laminectomy only and were not included

cIncluded six patients with primary bone tumors

d4.4% Mortality rate in patients with breast, thyroid and prostate cancer

eOf 74 patients who had quantified measurements of analgesia

Another chief indication for surgery includes treatment of metastatic cancer pain, which is often medically intractable and unresponsive to radiotherapy. Treatment of metastatic spinal lesions with vertebrectomy and stabilization has been shown to provide significant and sustained improvement in pain control (Table 8) [4, 5, 20, 24, 25, 35, 37, 47, 50, 52]. Similar pain relief was achieved in our series, as evidenced by decreases in VAS and pain medication scale scores that lasted for at least 1 year. This reduction in pain and narcotics usage (with concomitant reduction in side effects) may significantly improve the patients’ quality of life, regardless of whether the effect is secondary to pain-relieving vertebrectomy, decompression, and/or stabilization [36].

Several schemes, systems, and algorithms have been proposed in the past to determine which patients with spinal metastases in general, would benefit most from surgery [48, 49]. However, they fall short of determining factors that affect outcome in pathology-specific subgroups. Tokuhashi et al. [48] proposed a preoperative scoring system consisting of six parameters that typically affect prognosis: (1) general condition of the patient, (2) number of extraspinal bone metastases, (3) number of metastases in vertebral bodies, (4) number of metastases in major internal organs, (5) primary site of the cancer, and (6) severity of spinal cord injury. In this scheme, each parameter is given equal weight, and the scores are added together. However, the scoring system was based on only 64 patients with a wide variety of tumor histopathologies (at least 11 types) and included only 13 patients with breast cancer. More recently, Tomita et al. [49] also proposed a prognostic scoring system and surgical strategy for patients with spinal metastases. This system also recognizes the prognostic importance of the histological grade of malignancy of the primary tumor, the presence of visceral metastases to vital organs, and the extent of bone metastases. However, it also is not pathology specific, including nine different cancer histologies in 61 patients, only 16 of which possessed breast cancer. Thus, although these scoring systems may provide a useful guide to managing spinal metastases in general, they are not entirely applicable for all histological types of tumors, in particular, spinal metastases from breast cancer. Another criticism of these two scoring systems is the fact that neither takes into account medically intractable pain as an indication for surgery. However, in looking at the subset including breast cancer patients, our study supports their observations that spinal metastases arising from breast cancer carry a relatively favorable prognosis.

Once the decision is made as to which patients should undergo surgery, a surgical approach and technique must be chosen. The rationale for choosing a surgical approach must take into account the anatomical location and extent of spinal disease. In this study, we have illustrated our algorithm for surgical approaches based on the location of disease in the spine (Fig. 2). Almost one-third (29%) of the patients in our series required multilevel vertebrectomies and had results quite similar to those undergoing single-level procedures. This lends support for a somewhat more aggressive surgical approach, when necessary, to adequately decompress the neural elements and create a biomechanically sound construct.

Complications

A review of multiple series on surgical treatment of metastatic spine disease shows complication rates ranging from 10 to 52% [3, 38]. In a study of 145 patients undergoing surgery for vertebral metastasis, including 39 patients with primary breast cancer, there was 18.6% postoperative complication rate [38]. In our study, the risk of major and minor complications was comparable to those reported by others. However, we note a few differences compared with previous studies on complications for spinal surgery [33]. According to McDonnell et al. [33], age greater than 61-years-old was a risk factor for complications during anterior spinal surgery. In our series, age as a continuous or categorical variable was not associated with risk of complications. Secondly, in the series of McDonnell et al. blood loss of greater than 520 ml was a risk factor for complications. In our series, only blood losses greater than 2,500 ml were significantly associated with complications. There was a significantly higher blood loss when using a combined surgical approach relative to employing the anterior or posterior approaches alone. Similar to the series of McDonnell et al., we found a higher incidence of complications when using a combined approach, but this did not hold true in the multivariate analysis. It has been reported that preoperative radiotherapy increases wound infection and tissue breakdown rate, particularly after surgery by a posterior approach [18, 38, 51]. In our series, prior history of spinal irradiation was not a risk factor for the development of wound infections.

Conclusions

Spinal surgery for metastatic breast cancer significantly reduces pain and is efficacious in preserving neurological function over short-term follow up with acceptably low morbidity. Future reports on surgical outcomes for patients with metastatic spinal disease should be pathology-specific whenever possible, considering its paramount implications for optimal treatment and prognostication. In addition, future studies should also seek to quantify the contributions to patient outcome that may be provided by concomitant adjuvant therapy given in the peri-operative setting.

References

- 1.Akeyson EW, McCutcheon IE. Single-stage posterior vertebrectomy and replacement combined with posterior instrumentation for spinal metastasis. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:211–220. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.2.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barcena A, Lobato RD, Rivas JJ, Cordobes F, Castro S, Cabrera A, Lamas E. Spinal metastatic disease: analysis of factors determining functional prognosis and the choice of treatment. Neurosurgery. 1984;15:820–827. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198412000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilsky MH, Lis E, Raizer J, Lee H, Boland P. The diagnosis and treatment of metastatic spinal tumor. Oncologist. 1999;4:459–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chataigner H, Onimus M (2000) Surgery in spinal metastasis without spinal cord compression indications and strategy related to the risk of recurrence. Eur Spine J 9:523–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Chen LH, Chen WJ, Niu CC, Shih CH. Anterior reconstructive spinal surgery with Zielke instrumentation for metastatic malignancies of the spine. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120:27–31. doi: 10.1007/pl00021238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciray I, Lindman H, Astrom KG, Bergh J, Ahlstrom KH. Early response of breast cancer bone metastases to chemotherapy evaluated with MR imaging. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:198–206. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0455.2001.042002198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman RE, Rubens RD. The clinical course of bone metastases from breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1987;55:61–66. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coraddu M, Nurchi GC, Floris F, Meleddu V. Surgical treatment of extradural spinal cord compression due to metastatic tumours. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1991;111:18–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01402508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Degen JW, Gagnon GJ, Voyadzis JM, McRae DA, Lunsden M, Dieterich S, Molzahn I, Henderson FC. CyberKnife stereotactic radiosurgical treatment of spinal tumors for pain control and quality of life. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:540–549. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.5.0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLoach LJ, Higgins MS, Caplan AB, Stiff JL. The visual analog scale in the immediate postoperative period: intrasubject variability and correlation with a numeric scale. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:102–106. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199801000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enkaoua EA, Doursounian L, Chatellier G, Mabesoone F, Aimard T, Saillant G. Vertebral metastases: a critical appreciation of the preoperative prognostic tokuhashi score in a series of 71 cases. Spine. 1997;22:2293–2298. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199710010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esteva FJ, Valero V, Pusztai L, Boehnke-Michaud L, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN. Chemotherapy of metastatic breast cancer: what to expect in 2001 and beyond. Oncologist. 2001;6:133–146. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-2-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fourney DR, Gokaslan ZL. Use of “MAPs” for determining the optimal surgical approach to metastatic disease of the thoracolumbar spine: anterior, posterior, or combined. Invited submission from the joint section meeting on disorders of the spine and peripheral nerves, March 2004. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:40–49. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.1.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fourney DR, Schomer DF, Nader R, Chlan-Fourney J, Suki D, Ahrar K, Rhines LD, Gokaslan ZL. Percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for painful vertebral body fractures in cancer patients. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:21–30. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.98.1.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frankel HL, Hancock DO, Hyslop G, Melzak J, Michaelis LS, Ungar GH, Vernon JD, Walsh JJ. The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia. I. Paraplegia. 1969;7:179–192. doi: 10.1038/sc.1969.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galasko CS. Skeletal metastases and mammary cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1972;50:3–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerszten PC, Welch WC. Cyberknife radiosurgery for metastatic spine tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2004;15:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghogawala Z, Mansfield FL, Borges LF. Spinal radiation before surgical decompression adversely affects outcomes of surgery for symptomatic metastatic spinal cord compression. Spine. 2001;26:818–824. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200104010-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gokaslan ZL. Spine surgery for cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1996;8:178–181. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199605000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gokaslan ZL, York JE, Walsh GL, McCutcheon IE, Lang FF, Putnam JB, Jr, Wildrick DM, Swisher SG, Abi-Said D, Sawaya R. Transthoracic vertebrectomy for metastatic spinal tumors. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:599–609. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.4.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison KM, Muss HB, Ball MR, McWhorter M, Case D. Spinal cord compression in breast cancer. Cancer. 1985;55:2839–2844. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850615)55:12<2839::AID-CNCR2820551222>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatrick NC, Lucas JD, Timothy AR, Smith MA. The surgical treatment of metastatic disease of the spine. Radiother Oncol. 2000;56:335–339. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(00)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hortobagyi GN, Theriault RL, Porter L, Blayney D, Lipton A, Sinoff C, Wheeler H, Simeone JF, Seaman J, Knight RD. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal complications in patients with breast cancer and lytic bone metastases. Protocol 19 aredia breast cancer study group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1785–1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612123352401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosono N, Yonenobu K, Fuji T, Ebara S, Yamashita K, Ono K. Vertebral body replacement with a ceramic prosthesis for metastatic spinal tumors. Spine. 1995;20:2454–2462. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199511001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson RJ, Gokaslan ZL. Spinal-pelvic fixation in patients with lumbosacral neoplasms. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:61–70. doi: 10.3171/spi.2000.92.1.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonsson B, Petren-Mallmin M, Jonsson H, Jr, Andreasson I, Rauschning W. Pathoanatomical and radiographic findings in spinal breast cancer metastases. J Spinal Disord. 1995;8:26–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan E, Meier P. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. doi: 10.2307/2281868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klekamp J, Samii H. Surgical results for spinal metastases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998;140:957–967. doi: 10.1007/s007010050199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landreneau FE, Landreneau RJ, Keenan RJ, Ferson PF. Diagnosis and management of spinal metastases from breast cancer. J Neurooncol. 1995;23:121–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01053417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipton A, Theriault RL, Hortobagyi GN, Simeone J, Knight RD, Mellars K, Reitsma DJ, Heffernan M, Seaman JJ. Pamidronate prevents skeletal complications and is effective palliative treatment in women with breast carcinoma and osteolytic bone metastases: long term follow-up of two randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Cancer. 2000;88:1082–1090. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000301)88:5<1082::AID-CNCR20>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LoRusso P. Analysis of skeletal-related events in breast cancer and response to therapy. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:22–27. doi: 10.1016/S0093-7754(01)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maranzano E, Latini P. Effectiveness of radiation therapy without surgery in metastatic spinal cord compression: final results from a prospective trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:959–967. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00572-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonnell MF, Glassman SD, Dimar JR, 2nd, Puno RM, Johnson JR. Perioperative complications of anterior procedures on the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:839–847. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199606000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mercadante S. Malignant bone pain: pathophysiology and treatment. Pain. 1997;69:1–18. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller DJ, Lang FF, Walsh GL, Abi-Said D, Wildrick DM, Gokaslan ZL. Coaxial double-lumen methylmethacrylate reconstruction in the anterior cervical and upper thoracic spine after tumor resection. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:181–190. doi: 10.3171/spi.2000.92.2.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okuyama T, Korenaga D, Tamura S, Maekawa S, Kurose S, Ikeda T, Sugimachi K. Quality of life following surgery for vertebral metastases from breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1999;70:60–63. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199901)70:1<60::AID-JSO11>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onimus M, Papin P, Gangloff S. Results of surgical treatment of spinal thoracic and lumbar metastases. Eur Spine J. 1996;5:407–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00301969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pascal-Moussellard H, Broc G, Pointillart V, Simeon F, Vital JM, Senegas J. Complications of vertebral metastasis surgery. Eur Spine J. 1998;7:438–444. doi: 10.1007/s005860050105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, Payne R, Saris S, Kryscio RJ, Mohiuddin M, Young B. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:643–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66954-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prie L, Lagarde P, Palussiere J, el Ayoubi S, Dilhuydy JM, Durand M, Vital JM, Kantor G. Radiotherapy of spinal metastases in breast cancer. Apropos of a series of 108 patients. Cancer Radiother. 1997;1:234–239. doi: 10.1016/s1278-3218(97)89770-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheid V, Buzdar AU, Smith TL, Hortobagyi GN. Clinical course of breast cancer patients with osseous metastasis treated with combination chemotherapy. Cancer. 1986;58:2589–2593. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19861215)58:12<2589::AID-CNCR2820581206>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott J, Huskisson EC. Graphic representation of pain. Pain. 1976;2:175–184. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(76)90113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherry MM, Greco FA, Johnson DH, Hainsworth JD. Breast cancer with skeletal metastases at initial diagnosis. Distinctive clinical characteristics and favorable prognosis. Cancer. 1986;58:178–182. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860701)58:1<178::AID-CNCR2820580130>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siegal T. Surgical decompression of anterior and posterior malignant epidural tumors compressing the spinal cord: a prospective study. Neurosurgery. 1985;17:424–432. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sinardet D, Chabane A, Khalil T, Seigneuret E, Sankari F, Lemaire JJ, Chazal J, Irthum B. [Neurological outcome of 152 surgical patients with spinal metastasis] Neurochirurgie. 2000;46:4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sundaresan N, Digiacinto GV, Hughes JE, Cafferty M, Vallejo A. Treatment of neoplastic spinal cord compression: results of a prospective study. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:645–650. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199111000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sundaresan N, Galicich JH, Lane JM, Bains MS, McCormack P. Treatment of neoplastic epidural cord compression by vertebral body resection and stabilization. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:676–684. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.63.5.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Toriyama S, Kawano H, Ohsaka S. Scoring system for the preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine. 1990;15:1110–1113. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199011010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomita K, Kawahara N, Kobayashi T, Yoshida A, Murakami H, Akamaru T. Surgical strategy for spinal metastases. Spine. 2001;26:298–306. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weigel B, Maghsudi M, Neumann C, Kretschmer R, Muller FJ, Nerlich M. Surgical management of symptomatic spinal metastases. Postoperative outcome and quality of life. Spine. 1999;24:2240–2246. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wise JJ, Fischgrund JS, Herkowitz HN, Montgomery D, Kurz LT. Complication, survival rates, and risk factors of surgery for metastatic disease of the spine. Spine. 1999;24:1943–1951. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199909150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.York JE, Gokaslan ZL. Instrumentation of the spine in metastatic disease. Spine State Art Rev. 1999;13:335–350. [Google Scholar]