Abstract

The treatment of thoracolumbar fractures remains controversial. A review of the literature showed that short-segment posterior fixation (SSPF) alone led to a high incidence of implant failure and correction loss. The aim of this retrospective study was to compare the outcomes of the SS- and long-segment posterior fixation (LSPF) in unstable thoracolumbar junction burst fractures (T12–L2) in Magerl Type A fractures. The patients were divided into two groups according to the number of instrumented levels. Group I included 32 patients treated by SSPF (four screws: one level above and below the fracture), and Group II included 31 patients treated by LSPF (eight screws: two levels above and below the fracture). Clinical outcomes and radiological parameters (sagittal index, SI; and canal compromise, CC) were compared according to demographic features, localizations, load-sharing classification (LSC) and Magerl subgroups, statistically. The fractures with more than 10° correction loss at sagittal plane were analyzed in each group. The groups were similar with regard to age, gender, LSC, SI, and CC preoperatively. The mean follow-ups were similar for both groups, 36 and 33 months, respectively. In Group II, the correction values of SI, and CC were more significant than in Group I. More than 10° correction loss occurred in six of the 32 fractures in Group I and in two of the 31 patients in Group II. SSPF was found inadequate in patients with high load sharing scores. Although radiological outcomes (SI and CC remodeling) were better in Group II for all fracture types and localizations, the clinical outcomes (according to Denis functional scores) were similar except Magerl type A33 fractures. We recommend that, especially in patients, who need more mobility, with LSC point 7 or less with Magerl Type A31 and A32 fractures (LSC point 6 or less in Magerl Type A3.3) without neurological deficit, SSPF achieves adequate fixation, without implant failure and correction loss. In Magerl Type A33 fractures with LSC point 7 or more (LSC points 8–9 in Magerl Type A31 and A32) without severe neurologic deficit, LSPF is more beneficial.

Keywords: Thoracolumbar fracture, Classification, Spinal instrumentation, Short/long

Introduction

The treatment of thoracolumbar fractures remains controversial [21, 22, 30, 35, 38]. Although most authors believe that surgical treatment is needed for unstable burst fractures, the choice for operative approaches remains disputed [2, 5, 9, 21, 30, 38]. Common opinion is to obtain the most stable fixation by fixating as few vertebrae as possible and neural canal decompression [1, 2, 5, 7, 21].

Short-segment posterior fixation (SSPF) is the most common and simple treatment, offering the advantage of incorporating fewer motion segments in the fusion [2, 26, 29, 30, 36, 37]. A review of the literature showed that SSPF alone led to a 9–54% incidence of implant failure and re-kyphosis in the long-term, and 50% of the patients with implant failure had moderate-to-severe pain [2, 5, 25, 33]. To prevent this, several techniques have been developed to augment the anterior column in burst fractures, such as transpedicular bone grafting [2, 13, 26, 27], placement of body augmenter [9, 30], polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) injection [10, 11, 40], anterior instrumentation and strut grafting [21, 24, 38], or long-segment posterior fixation (LSPF) [1, 19, 34].

There are few controlled studies explaining the reasons for implant failure and re-kyphosis for thoracolumbar fractures [2, 4, 7, 32, 36]. Most of these were retrospective studies including diverse patient groups, as well as all thoracal and lumbar fractures. In the current study, only patients with thoracolumbar junction (T12–L2), Magerl Type A fractures were included and patients were divided into two homogeneous groups according to short- and long-segment application. Comparisons of SI, CC and functional scores, taking into account age, sex, localization, Magerl subgroups [31], and LSC [32], were made within and between groups. Features of fractures with a loss of correction were determined. The aim of the present study was to examine LSC efficiency and to determine the proper treatment choice for thoracolumbar junction in Magerl Type A fractures. Detection of those fractures in which SSPF without supporting anterior column is sufficient and does not lead to implant failure and loss of correction was one of the goals of this study.

Material and methods

Between March 2001 and May 2004, 63 patients with acute, traumatic fractures of the thoracolumbar junction were treated with short- or long-segment posterior instrumentation and short level fusion in our department. Patients included in this retrospective study had: (a) a single-level burst fracture of more than 6 points as graded using the load-sharing score (LSS) described by McCormack et al.; (b) neurologic function limited to Grades C, D, or E using the grading system of Frankel et al.; (c) limited involvement of T12–L2; (d) <3 weeks from the time of injury (e) CT scan revealing a burst-type fracture with more than 25% retropulsion into the canal; and (f) SI of more than 15°. Furthermore, we eliminated: (a) 16 patients with serious neurological problems (Frankel Grades A and B), who were treated with anterior or combined surgeries; (b) ten patients who had Magerl Type B, and C fractures; (c) eight patients who were lost to follow-up; (d) two patients who died of unrelated medical illness; and (e) 18 patients who had inadequate follow-up period.

The patients were divided into two groups according to the number of instrumented levels. Group I included 32 patients treated by SSPF (four screws: one level above and below the fracture) and Group II included 31 patients treated by LSPF (eight screws: two levels above and below the fracture). All the operations were performed by one of the two authors (MA, BÖ), without any discriminations according to the fixation type. Since this is a retrospective study, the authors had decided to apply short- or long-segment posterior fixation during the operation, till 2004 January. After this time, the instrumentation type was selected considering the age of the patients with LSC and Magerl Classification. One of two spinal instrumentation systems—Alıcı (Hipokrat, Izmir, Turkey) or Xia (Stryker, Bordeaux, France)—was used in all patients. Screws were 40 or 45 mm long, depending on the level and size of the vertebra. At the tenth and eleventh thoracic levels, 5.5 or 6.5-mm-diameter multiaxial screws and at the twelfth thoracic level and caudally 6.5-mm-diameter multiaxial screws were used. The instrumentation was applied bilaterally, and cross-links were used to augment torsional rigidity. Reduction of the fracture and indirect decompression of the spinal canal were accomplished by the rod contouring and extension and compression-distraction forces before tightening the screws. No discectomy or laminectomy was performed. Posterolateral short level fusion (only fractured vertebra included the fusion area) with autogenous bone-graft taken from the iliac crest was performed in all patients. Patients in each group wore a thoracolumbar brace for 3 months.

Complete clinical and radiologic examinations were done on admission. SI was measured as described by Farcy et al. [16]. Computed tomography (CT) scans were taken preoperatively to classify the fracture type, to assess CC and comminution, and to see whether the pedicles of the neighboring vertebrae were intact and able to take the screws. Spinal CC was calculated with the formula adapted by Willen et al. [42]. CT scans were taken at least 1 year after the operation. A fracture severity score was constructed using the LSC described by McCormack et al. [32] to compare fracture severity. The fractures were classified according to the system developed by Magerl et al. [31].

Clinical and radiographic follow-up was at 2, 4, 6, and 12 months and every year thereafter. Data were collected concerning age, sex, localization, type and severity of injury according to LSC, presence of neurological deficits, pain and work status, complications and radiologic parameters (SI, and CC). Correction loss was defined as an increase of more than 10° in SI in the latest follow-up radiographs compared with the measurement on the initial postoperative radiographs.

Neurologic assessment was done using the grading scale of Frankel et al. [17]. Pain and work status at latest follow-up were recorded based on the scale of Denis et al. [15]. This is a five-level scale ranging from no pain (P1) to constant, severe pain (P5), and from return to heavy labor (W1) to completely disabled (W5).

The clinical and radiographic outcomes of treatment with the SSPF were compared with those of treatment with the LSPF using parametric and nonparametric analyses as appropriate for the data. The statistical analyses were performed with use of SPSS version-13.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA). A P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

The groups were similar with regard to age, sex, localization, LSC, SI, and CC preoperatively (P > 0.05). The mean follow-ups were similar for both groups. Patients’ demographics and distribution of fractures are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ demographics and distribution of fractures according to age, sex, localization, LSC, and Magerl classification

| Group I | Group II | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 32 | 31 | 63 |

| Mean age (years) | 42.6±14.9 | 44.8±14.9 | 43.7±14.9 |

| Gender (male/female) | 19/13 | 18/13 | 37/26, 58.7%/41.3% |

| Mechanism of injury | |||

| Motor vehicle accident | 17 | 23 | 40 (63.5%) |

| Falling | 15 | 8 | 23 (36.5%) |

| Fracture location | |||

| T12 | 9 (28.1%) | 9 (29%) | 18 (28.6%) |

| L1 | 13 (40.6%) | 16 (51.6%) | 29 (46%) |

| L2 | 10 (31.3%) | 6 (19.4%) | 16 (25.4%) |

| Magerl classification | |||

| A3.1 | 20 (62.5%) | 19 (61.3%) | 39 (61.9%) |

| A3.2 | 4 (12.5%) | 4 (12.9%) | 8 (12.7%) |

| A3.3 | 8 (25%) | 8 (25.8%) | 16 (25.4%) |

| Mean load sharing score | 6.5 | 6.8 | 6.65 |

| 6 | 19 (59.4%) | 13 (41.9%) | 32 (50.8%) |

| 7 | 9 (28.1%) | 12 (38.7%) | 21 (33.3%) |

| 8 | 4 (12.5%) | 6 (19.4%) | 10 (15.9%) |

| Frankel performance scale | |||

| C | – | 1 | 1 |

| D | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| E | 30 | 27 | 57 |

| Follow-up (month) | 36 (18–58) | 33 (18–58) | 34.4 (18–58) |

Restoration of SI, and CC were well maintained in each group, but were better in Group II. Correction loss in Group II (3.1±2.9°) was much less than in Group I (5.2±4.1°) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The changes in SI, and CC in the preoperative, postoperative, and follow-up periods

| Group I | Group II | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sagittal index | |||

| Preoperatively | 20.7±4.6 | 18.9±4.5 | 0.126 |

| Postoperatively | 7.8±5.3 | 5.0±3.6 | 0.017 |

| Correction (%) | 62.6±24.4 | 73.6±18.6 | 0.049 |

| Correction loss | 5.2±4.1 | 3.1±2.9 | 0.025 |

| Last follow-up | 13±6.2 | 8.1±4.3 | 0.001 |

| Last follow-up correction (%) | 38±26 | 56.1±24.8 | 0.006 |

| Canal compromise % | |||

| Preoperatively | 44.1±11.6 | 45.9±12.5 | 0.553 |

| Last follow-up | 25.6±9.9 | 22.2±11.8 | 0.220 |

| Remodeling | 42.7±13.7 | 53.8±19.1 | 0.010 |

*T test

There were no significant differences in SI and CC in Group I according to Magerl classification (P > 0.05). SI correction was better in Type A31 than Types A32 and A33 in Group II (P = 0.019). Between Groups I and II, for Type A31, there were significant differences in SI postoperative and last follow-up correction (P < 0.05), and for Type A33 in SI last follow-up correction and canal remodeling (P < 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3.

The changes in SI, and CC in the preoperative, postoperative, and follow-up periods according to Magerl classification

| A3.1 | A3.2 | A3.3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GroupI | Group II | GroupI | GroupII | Group I | Group II | |

| Sagittal index | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 20.4 | 17.9 | 18.0 | 18.3 | 23.0 | 21.8 |

| P = 0.061 | P = 0.888 | P = 0.681 | ||||

| Postoperatively | 6.7 | 3.8 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 10.3 | 6.1 |

| P* = 0.045 | P = 0.938 | P = 0.102 | ||||

| Correction % | 68.1 | 79.2 | 50.0 | 51.8 | 55.3 | 71.3 |

| P = 0.086 | P = 0.928 | P = 0.144 | ||||

| Correction loss | 5.7 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 5.1 | 1.9 |

| P = 0.143 | P = 0.620 | P = 0.064 | ||||

| Last follow-up | 12.4 | 7.6 | 11.3 | 10.5 | 15.4 | 8 |

| P = 0.014 | P = 0.812 | P = 0.008 | ||||

| Last follow-up correction % | 40.4 | 57.5 | 36.8 | 39.8 | 32.5 | 60.9 |

| P = 0.044 | P = 0.879 | P = 0.043 | ||||

| Canal compromise % | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 42.6 | 44.9 | 38.5 | 43.5 | 50.8 | 49.4 |

| P = 0.515 | P = 0.390 | P = 0.855 | ||||

| Last follow-up | 24.2 | 23.6 | 20.0 | 19.3 | 31.8 | 20.3 |

| P = 0.860 | P = 0.843 | P = 0.082 | ||||

| Remodeling | 43.2 | 50.4 | 48.5 | 54.8 | 38.5 | 61.5 |

| P = 0.221 | P = 0.424 | P = 0.007 | ||||

| LSC | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6 | 6.5 | 7 | 7.3 |

*Independent sample t test

Correction loss, and postoperative and last follow-up corrections were not significantly different between T12, L1 and L2 in both groups (P > 0.05). Last follow-up SI correction for L1 were more significant in Group II than in Group I (P < 0.01), and canal remodeling was better in Group II than in Group I for T12 (P < 0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

The changes in SI, and CC in the preoperative, postoperative, and follow-up periods according to localization

| T12 | L1 | L2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GroupI | Group II | GroupI | GroupII | Group I | Group II | |

| Sagittal index | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 21.0 | 18.1 | 18.9 | 18.7 | 22.8 | 20.8 |

| P* = 0.191 | P = 0.874 | P = 0.496 | ||||

| Postoperatively | 8.9 | 5.4 | 6.7 | 3.7 | 8.4 | 8.0 |

| P = 0.114 | P = 0.054 | P = 0.889 | ||||

| Correction % | 59.2 | 69.7 | 64.1 | 80.8 | 63.7 | 60.7 |

| P = 0.228 | P = 0.055 | P = 0.815 | ||||

| Correction loss | 4.9 | 3.7 | 5.4 | 3.1 | 5.1 | 2.3 |

| P = 0.565 | P = 0.059 | P = 0.164 | ||||

| Last follow-up | 13.8 | 9.0 | 12.1 | 6.8 | 13.5 | 10.3 |

| P = 0.146 | P = 0.005 | P = 0.248 | ||||

| Last follow-up correction % | 37.8 | 49.0 | 36.8 | 62.9 | 39.6 | 48.3 |

| P = 0.383 | P = 0.010 | P = 0.517 | ||||

| Canal compromise % | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 41.0 | 39.1 | 41.8 | 49.8 | 49.8 | 45.7 |

| P = 0.644 | P = 0.084 | P = 0.576 | ||||

| Last follow-up | 26.4 | 16.7 | 21.3 | 25.6 | 30.3 | 21.3 |

| P = 0.056 | P = 0.245 | P = 0.189 | ||||

| Remodeling | 36.8 | 60.3 | 48.4 | 49.6 | 40.5 | 55.3 |

| P = 0.005 | P = 0.857 | P = 0.087 | ||||

| LSC | 6.4 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.8 |

*Independent sample t test

In Group I, last follow-up SI was better in LSS 6 than LSS 7 and 8 (P = 0.022). In last follow-up, CC were significantly better for LSS 6 and 7 than LSS 8 (P < 0.001). In Group II, last follow-up CC were better LSS 6 and 7 than LSS 8 (P = 0.019). In comparison of two groups in LSS 6; canal remodeling, in LSS 7; SI last follow-up values and correction loss, in LSS 8, last follow-up values was significantly better in Group II (P < 0.01) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Changes in SI, and CC in the preoperative, postoperative, and follow-up periods according to LSC

| 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GroupI | Group II | GroupI | GroupII | Group I | Group II | |

| Sagittal index | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 19.2 | 17.5 | 22.8 | 18.8 | 23.3 | 22.5 |

| P* = 0.164 | P = 0.052 | P = 0.863 | ||||

| Postoperatively | 6.8 | 5.1 | 8.6 | 5.2 | 11.3 | 4.7 |

| P = 0.253 | P = 0.115 | P = 0.124 | ||||

| Correction % | 63.6 | 71.5 | 65.1 | 72.1 | 52.3 | 81.3 |

| P = 0.348 | P = 0.436 | P = 0.096 | ||||

| Correction loss | 3.8 | 3.2 | 7.6 | 3.1 | 6.3 | 3.0 |

| P = 0.568 | P = 0.009 | P = 0.302 | ||||

| Last follow-up | 10.6 | 8.2 | 16.1 | 8.2 | 17.5 | 7.7 |

| P = 0.159 | P = 0.009 | P = 0.005 | ||||

| Last follow-up correction % | 44.4 | 53.3 | 31.7 | 54.2 | 21.5 | 65.8 |

| P = 0.316 | P = 0.087 | P = 0.01 | ||||

| Canal compromise % | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 37.4 | 37.9 | 51.7 | 46.7 | 58.8 | 61.7 |

| P = 0.823 | P = 0.318 | P = 0.670 | ||||

| Last follow-up | 21.2 | 15.9 | 27.8 | 24.5 | 41.5 | 31.0 |

| P = 0.046 | P = 0.499 | P = 0.204 | ||||

| Remodeling | 43.8 | 59.9 | 45.8 | 48.7 | 30.0 | 50.8 |

| P = 0.004 | P = 0.740 | P = 0.052 | ||||

*Independent sample t test

The association between age and SI and CC were evaluated. The patients in both groups were divided to subgroups according to their age below or above 50 years. There was no significant difference between SI and correction loss preoperatively and early postoperatively, whereas there was significant difference between two groups at the last follow-ups (P = 0.002). There was significant difference between the patients who underwent LSPF and SSPF (with four screws), younger than 50 years (P = 0.048), also between two groups of the patients older than 50 years (P = 0.034) at the latest follow-up. Significant difference between the patients older than 50 years who underwent SSPF and the patients under than 50 years who underwent LSPF (P = 0.004) was observed. Also the last follow-up values were worst in the patients older than 50 years, treated with SSPF (Table 6).

Table 6.

Changes in SI, and CC in the preoperative, postoperative, and follow-up periods according to age (50 years)

| GroupI | Group II | P values* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 years↓ | 50 years↑ | 50 years↓ | 50 years↑ | ||

| Sagittal index | |||||

| Preoperatively | 21.2 | 20.6 | 19.4 | 17.5 | 0.154 |

| Postoperatively | 7.5 | 8.6 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 0.068 |

| Correction loss | 4.6 | 5.8 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 0.109 |

| Last follow-up | 12.1 | 14.7 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 0.002 |

| Canal compromise % | |||||

| Preoperatively | 43.7 | 44.1 | 49.8 | 41 | 0.208 |

| Last follow-up | 25.5 | 25.2 | 24.1 | 19.4 | 0.459 |

| Remodeling | 41.5 | 44.5 | 53.2 | 55.6 | 0.061 |

*ANOVA

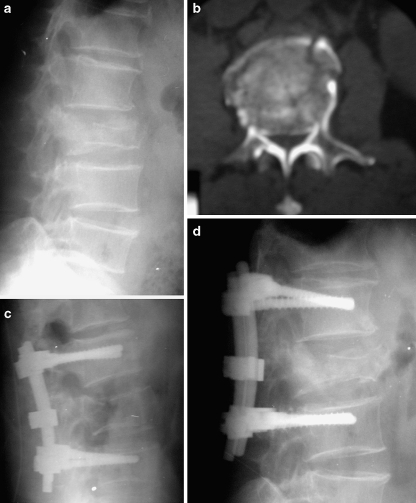

Postoperatively, kyphosis was corrected by more than 10° in 25 (78.1%) of the 32 patients in Group I, and in 26 (83.9%) of the 31 patients in Group II. Last follow-up values showed a correction of more than 10° in 10 (31.2%) patients in Group I and in 18 patients (58.1%) in Group II. Correction loss more than 10° was found in six patients (18.8%) in Group I and two (6.5%) in Group II (Table 7). Five of these eight patients were older than 50 years (four in Group I, one in Group II). One patient in Group I had a worse SI at last follow-up than preoperative value. Final SI did not exceed 30° in any case in either group. According to localization, the highest correction loss (5.4±3.7) was observed in SSPF performed on L1 vertebra fractures. Increased correction loss was observed with increased LSS’s in Group I (Fig. 1a–d). Adequate canal remodeling could be achieved also in the patients with inadequate sagittal contour correction (Fig. 2a–e).

Table 7.

More than 10° correction loss in Group I and in Group II according to localization, Magerl classification and LSC

| Group I | Group II | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Localization | |||

| T12 | 2/9 (22.2%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | 3/18 (16.7%) |

| L1 | 2/13 (15.4%) | 1/16 6.2%) | 3/29 (10.3%) |

| L2 | 2/10 (20%) | 0/6 (0%) | 2/16 (12.5%) |

| Magerl classification | |||

| A31 | 4/20 (20%) | 2/19 (10.5%) | 6/39 (15.4%) |

| A32 | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) |

| A33 | 2/8 (25%) | 0/8 (0%) | 2/16 (12.5%) |

| LSC | |||

| 6 | 1/19 (5.3%) | 0/13 (0%) | 1/32 (3.1%) |

| 7 | 4/9 (44.4%) | 1/12 (8.3%) | 5/21 (23.8%) |

| 8 | 1/4 (25%) | 1/6 (16.6%) | 2/10 (20%) |

Fig. 1.

a Lateral radiograph shows an L2 burst fracture in a 59-year-old man. b Axial CT image demonstrates 70% canal compromise. c Immediate postoperative lateral radiograph shows the application of SSPF and correction of the kyphotic deformity of the fractured vertebra. d Last follow-up lateral radiograph shows more than 10° correction loss and recollapse in fractured vertebra

Fig. 2.

a Lateral radiograph shows an L1 burst fracture in a 24-year-old man. b Axial CT image demonstrates 72% canal compromise. c, d Early and late postoperative lateral radiographs show inadequate correction in sagittal balance. e Last follow-up axial CT image shows excellent remodeling in canal compromise

All patients with incomplete neurologic injuries improved one Frankel grade. In the last follow-up visit, all 32 patients in Group I were Frankel Grade E, and in Group II, 31 patients Grade E, and one was Grade D. There were no implant failures, including no screw breakage, or loosening in either group.

In Group I, based on the pain scale of Denis, nine patients (28.1%) had no pain (P1); 14 patients (43.8%) had slight pain with no need for medication (P2); seven patients (21.9%) had moderate pain with a need for medication but no interruption of work or major change in activities of daily living (P3); and two patients (6.2%) had moderate-to-severe pain with a need for frequent medication and occasional absence from work or a major change in activities of daily living (P4). Postoperative work status was assessed as follows: return to previous activity (nine patients: 28.1%), return to less strenuous work (15 patients: 46.9%), disability after the injury (seven patients: 21.9%), and unemployed before the injury (one patient: 3.1%). In Group II, eight patients (25.8%) had P1; 16 patients P2 (51.6%); five patients (16.1%) P3; and two patients (6.5%) P4. Eight patients (25.8%) returned to previous activity, 13 patients (41.9%) returned to less strenuous work, nine patients (29%) disabled after the injury, and one patient (3.2%) unemployed before the injury. No patient in either group had constant or severe incapacitating pain and a chronic need for medication (Table 8).

Table 8.

Denis pain scale and work status according to Magerl classification, localization and LSC

| Denis pain scale | Denis work status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 (I/II) | P2 (I/II) | P3 (I/II) | P4 (I/II) | W1 (I/II) | W2 (I/II) | W3 (I/II) | W4 (I/II) | |

| Classification | ||||||||

| A3.1 | 7/5 | 9/8 | 3/4 | 1/2 | 7/5 | 8/6 | 5/7 | 0/1 |

| A3.2 | 2/1 | 2/3 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 0/1 | 0/0 |

| A3.3 | 0/2 | 3/5 | 4/1 | 1/0 | 0/2 | 5/5 | 2/1 | 1/0 |

| Location | ||||||||

| T12 | 3/4 | 4/3 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 3/4 | 4/3 | 2/1 | 0/1 |

| L1 | 5/3 | 7/10 | 1/2 | 0/1 | 5/3 | 5/8 | 3/5 | 0/0 |

| L2 | 1/1 | 3/3 | 5/2 | 1/0 | 1/1 | 6/2 | 2/3 | 1/0 |

| LSC | ||||||||

| 6 | 8/6 | 9/6 | 2/1 | 0/0 | 8/6 | 9/5 | 2/2 | 0/0 |

| 7 | 1/2 | 5/6 | 2/3 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 5/5 | 3/4 | 0/1 |

| 8 | 0/0 | 0/4 | 3/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 1/3 | 2/3 | 1/0 |

| Total | 17 | 30 | 12 | 4 | 17 | 28 | 16 | 2 |

| Percentage (%) | 27 | 47.6 | 19 | 6.3 | 27 | 44.4 | 25.4 | 3.2 |

In Group I, pain was excessive in Magerl Type A33, LSS 8, and L2 fractures, whereas in Group II, pain was more excessive in LSS 8, statistically (P < 0.05). In comparison of Group I and II, there was no difference between localization and LSC, but in Group I Magerl Type A33 fractures pain was evident (P < 0.05).

The functional outcome according to the scale of Denis was satisfactory in 23 of 32 patients (71.9%) in Group I and in 24 of 31 patients (77.4%) in Group II (Table 6).

Discussion

Selection of the surgical method in the treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures remains a matter of discussion [2, 5, 9, 11, 14, 21, 38, 43]. Multiple parameters have to be considered, such as the type and stability of the fracture, degree of CC, and neurological status [5, 7, 21, 35, 43]. SSPF is frequently regarded as the procedure of choice because it offers advantages such as incorporating fewer motion segments in the fusion, shorter operative time and fewer blood transfusions. But without body reconstruction, SSPF has a 9–54% incidence of implant failure and re-kyphosis [2, 5, 30, 33, 34]. To prevent this, several techniques have been developed to augment the anterior column in burst fractures. Transpedicular bone grafts have been used to reconstruct the vertebral body in addition to SSPF [2, 3, 13, 26]. Many authors believe that transpedicular bone grafts have not prevented early implant failure and correction loss, and may lead to low anterior interbody fusion rates in the long term [2, 26, 29]. To improve the anterior support, a body augmenter was proposed to be inserted into the collapsed vertebral body [9, 30]. The biomechanical analysis showed that the body augmenters combined with SSPF greatly increased the stability, but long-term results are not known and augmentation block application is technically demanding and sometimes impossible in certain fracture types [9]. Recently, PMMA was reported to strengthen the fractured body and prevent implant failure, but the long-term result is unknown [10, 11, 40]. Injection of PMMA into a fractured vertebral body may lead to cement extrusion into the spinal canal, particularly if the posterior longitudinal ligament is torn. Anterior instrumentation and strut grafting have proven to be effective [21, 24, 38], but require a more invasive approach, prolonged operation time, blood loss, and morbidity [25, 43].

The thoracolumbar junction constitutes the transition zone between the rigid thoracic and the mobile lumbar spine. Vertebral fractures in this area are usually extremely unstable and kyphotic deformity is often of significant degree [14, 33]. Therefore, inserting the screws only one level above and below the fractured segment might not have provided adequate stability. Gurr et al. [19] found that two levels above and below the injured level in an unstable calf spine model provided more stiffness than the intact spine. Katonis et al. [22] found that two levels above and one level below the fracture at the thoracolumbar junction and SSPF in the lumbar area provided stability and formed a rigid construct with no correction loss. Furthermore, Carl et al. [8] reported that segmental pedicular fixation two levels above the kyphosis should be used at the thoracolumbar junction, where compression forces act more anteriorly. In contrast, in the more lordotic middle and lower lumbar spine, where the compressive forces act more posteriorly, no implant failures occurred with the one above, one below construct. Use of four pairs of screws (two above and two below) to lengthen the level arm of the construct would probably not only have enhanced the stability but also allowed effective reduction of kyphotic deformity [5]. SSPF alone can give good clinical and radiological outcomes for certain fractures in the thoracolumbar junction. Detection of those fractures in which SSPF without supporting anterior column is sufficient and does not lead to implant failure and correction loss was one of the goals of this study.

Postoperative correction loss after posterior instrumentation has been reported by many authors (Table 9). The mean correction loss ranged from 0.3° to 15.4° in the reported series that we reviewed, whereas in our series was 5.2° in Group I and 3.1° in Group II. Correction loss was greater and more common in the SSPF group than in the LSPF group at last follow-up. Correction loss (>10°) developed in six (19.4%) of the 32 cases of SSPF, versus in only two (6.5%) of the 31 cases of LSPF. Alvine et al. [5] reported 39% screw breakage and 23% unplanned re-operation. McLain et al. [33] reported ten (54%) instrumentation failures among 19 fractures. In our series, no instrument failure occurred in either group.

Table 9.

Overview of the literature about implant failure and correction loss after posterior instrumentation with variable techniques

| Author | Age | No | Level of injury | Operation | Kyphotic angle | Canal comprom. | F-U | Implant failure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | a | c | |||||||

| Li [30] | 56 | 75 | T11–L2 | SSPF + TBA | 25 | 3.6 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 40 | 0 | ||

| 58 | 45 | SSPF | 24.8 | 4.2 | 19.6 | 15.4 | 37 | 20% | ||||

| Wood [43] | 42 | 18 | T10–L2 | PF | 10.7 | 4.5 | 12.5 | 8 | 36 | 18 | 43.5 | 4/18 |

| 39 | 20 | AF | 10.4 | 4.7 | 11 | 6.3 | 39 | 15 | 0/20 | |||

| Alvine [5] | 31 | 41 | T11–L5 | SSPF ± TBG | 12 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 61 | 32 | 52 | 39% |

| LSPF ± TBG | ||||||||||||

| Cho [11] | 43 | 20 | T12–L3 | SSPF + PMMA | 20.3 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 0.3 | 25 | 0 | ||

| 48 | 50 | SSPF | 18.3 | 5.7 | 11.9 | 6.2 | 30 | 22% | ||||

| Moon [34] | 34.5 | 24 | T12–L5 | LSPF:2HS–1SH | 20.3 | 7 | 11.4 | 4.4 | 32–72 | 3/24 | ||

| 18 | SSPF | 14.7 | 2.4 | 8.1 | 5.7 | 6/18 | ||||||

| Knop [26] | 46 | 29 | T12–L5 | SSPF + TBG | 15.2 | 3.4 | 11.2 | 7.8 | 42 | |||

| Leferink [29] | 32 | 183 | T9–L5 | SSPF + TBG | 9.9 | −0.3 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 24 | 20/183 | ||

| Alanay [2] | 35 | 10 | T11–L3 | SSPF + TBG | 20 | 3.6 | 8.3 | 4.7 | 32 | 50% | ||

| 34 | 10 | SSPF | 20 | 2.4 | 8.2 | 5.8 | 40% | |||||

| Knop [27] | 34 | 56 | T11–L5 | SSPF + TBG | −15.6 | 0.4 | −9.7 | 10.1 | ||||

| Sanderson [37] | 33.1 | 24 | T12–L2 | SSPF | 20.7 | 5.8 | 13.9 | 8.1 | 4 (14%) | |||

| Katonis [22] | 37.6 | 30 | T11–L5 | PF: 2SS–1S SSPF | 22.5 | 5 | 7.7 | 2.7 | 51 | 22 | 31 | 4/30 |

| Muller [35] | 33 | 20 | SSPF | 18 | 5.4 | 9 | 3.6 | 43 | 6.4 years | |||

| De Peretti [14] | 37 | 34 | T12–L2 | 2HS–1SH | 19.2 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 49 | |||

| McLain [33] | 29 | 19 | T12–L5 | SSPF | 53%>10 | 15 | 10/19 | |||||

| Current authors | 42.6 | 32 | T12–L2 | SSPF | 20.7 | 7.8 | 13.0 | 5.2 | 44 | 26 | 36 | – |

| 44.8 | 31 | LSPF | 18.9 | 5.0 | 8.1 | 3.1 | 46 | 22 | 33 | – | ||

a preoperatively, b postoperatively, c last follow-up, d loss of correction, F-U Follow-up, SSPF Short segment posterior fixation, TBA Transpedicular body augmenter, PF Posterior fixation, AF Anterior fixation, TBG transpedicular bone grafting, PMMA Polymethyl methacrylate, 2HS–1SH 2 Hook,Screw–1Screw,Hook, 2SS–1S 2 Screw,Screw–1Screw

We observed that radiological outcomes are affected especially by localization, fracture type and LSC. Although there was statistically significant improvement in all radiological parameters postoperatively in both groups, we observed more correction loss in L1 fractures treated by SSPF, and the fractures having high LSS’s. According to final values, correction percentages in these fractures were significantly less than in those treated by LSPF. SSPF should be performed safely without any anterior column support in any localization, in Type A31 and A32 fractures with a LSS of 6. In the same manner, in T12 or L2 Magerl Type A33 fractures with a LSS of 6 or less, SSPF should be preferred. LSPF may be performed for all types of fractures in the thoracolumbar junction despite incorporating more motion segments in the fusion. Although radiologic outcomes are better, functional outcomes do not differ from those achieved with SSPF except Magerl Type A33 fractures. The results of our study suggest that LSPF can provide more secure fixation and better correction than SSPF in unstable thoracolumbar burst fractures, thereby avoiding correction loss.

McCormack et al. [32] described an LSC to identify which unstable thoracolumbar fractures are likely to have poor anterior load-bearing capabilities resulting in correction loss and implant failure. In those instances, they recommended either a LSPF or two-stage anterior and posterior procedures. Because the screws tended to be highly prone to breakage at a total score of seven or more, McCormack and Parker et al. concluded that LSS 6 or less are likely to be good candidates for SSPF [32, 36]. Based on the LSC, the more comminution, wider displacement (>50% body cross-section), and increased kyphotic correction (>10°) will lead to implant failure [36]. Because the LSC only quantifies comminution, does not identify ligamentous disruption and is not related to the mechanism of injury, the authors never based their decisions regarding whether the patient is reliable enough for SSPF and fusion solely on its use [36]. In the present study, clinical and radiological outcomes of the patients with a LSS 6 treated by SSPF were satisfactory. We believe that LSC with Magerl classification may be used for burst fractures to decide whether patients need anterior augmentation procedures or whether LSPF should be performed. We think that LSC with Magerl classification is effective for detecting fractures that may lead to correction loss. A LSS 6 indicates adequate sharing of load along with the implant to permit only SSPF and fusion. A LSS more than 7 indicates poor transfer of load through most of the injured vertebra and points to the necessity for anterior support or lengthening of the construct, especially in Magerl Type A33 fractures.

Several authors have described spontaneous remodeling of the spinal canal during follow-up [11, 28, 39, 41, 44]. The relation between the canal diameter and its association with neurological sequelae after trauma has been cited numerous times in the literature. Some authors have found no relation [6, 12, 18], while others have identified varying levels of correlation [23, 39]. The conflicting reports are explained by the work of Hashimoto et al. [20], who found the probability of neurologic injury to be dependent on both the degree of CC and the level of fracture. A CC of 35% at T10–12 level, and of 45% at L1 and L2 levels can be tolerated without any neurological deficit. The present study shows that fracture reduction by angular correction and distraction is associated with a marked increase in the percentage of patients with a cleared spinal canal, from 55.9 to 74.4% in Group I and from 54.1 to 77.8% in Group II. Canal remodeling was observed at rates of 42.7 and 53.8%, respectively. We believe that there is a correlation between CC and the neurological deficit. CC was observed 68.8% in six patients with neurological deficits versus 43.8% in patients without neurological deficit.

Conclusion

The recent literature does not provide a gold standard for the treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures. Therefore, the choice of therapy should be made individually, considering the type and severity of fracture, the neurological status and the patient’s condition as well as the skills of the surgeon. The patients in this study showed a reduced quality of life, independent of the method of surgical treatment. In our opinion, the current study emphasizes that Magerl classification together with LSC is reliable for better fracture treatment and prognosis. We recommend that, especially in younger patients, who need more motion, with LSS of 7 or less with Magerl Type A3.1 and A3.2 (six or less in Magerl Type A3.3) fractures without neurological deficit, SSPF achieves adequate fixation, without implant failure and correction loss. In Magerl Type A3.3 fractures with LSS of 7 or more without severe neurologic deficit (Frankel C, D, E), LSPF is more beneficial.

References

- 1.Akbarnia BA, Crandall DG, Burkus K, et al. Use of long rods and a short arthrodesis for burst fractures of the thoracolumbar spine. A long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(11):1629–1635. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alanay A, Acaroglu E, Yazici M, et al. Short-segment pedicle instrumentation of thoracolumbar burst fractures: does transpedicular intracorporeal grafting prevent early failure. Spine. 2001;26(2):213–217. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alanay A, Acaroglu E, Yazici M, et al. The effect of transpedicular intracorporeal grafting in the treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures on canal remodeling. Eur Spine J. 2001;10(6):512–516. doi: 10.1007/s005860100305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aligizakis AC, Katonis PG, Sapkas G, et al. Gertzbein and load sharing classifications for unstable thoracolumbar fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;411:77–85. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000068187.83581.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvine GF, Swain JM, Asher MA, et al. Treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures with variable screw placement or Isola instrumentation and arthrodesis: case series and literature review. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17(4):251–264. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000095827.98982.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boerger TO, Dickson RA. Does canal clearance affect neurological outcome after thoracolumbar burst fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(5):629–635. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B5.11321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briem D, Lehmann W, Ruecker AH, et al. Factors influencing the quality of life after burst fractures of the thoracolumbar transition. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(7):461–468. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0710-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carl AL, Tromanhauser SG, Roger DJ. Pedicle screw instrumentation for thoracolumbar burst fractures and fracture-dislocations. A calf spine model. Spine. 1992;17:317–324. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199208001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen HH, Wang WK, Li KC, et al. Biomechanical effects of the body augmenter for reconstruction of the vertebral body. Spine. 2004;29(18):382–387. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000139308.65813.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen JF, Lee ST. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for treatment of thoracolumbar spine bursting fracture. Surg Neurol. 2004;62(6):494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2003.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho DY, Lee WY, Sheu PC. Treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures with polymethyl methacrylate vertebroplasty and short-segment pedicle screw fixation. Neurosurgery. 2003;53(6):1354–1360. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000093200.74828.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dall BE, Stauffer ES. Neurologic injury and recovery patterns in burst fractures at the T12 or L1 motion segment. Clin Orthop. 1988;233:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniaux H, Seykora P, Genelin A, et al. Application of posterior plating and modifications in thoracolumbar spine injuries: indication, techniques and results. Spine. 1991;16:125–133. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199103001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Peretti F, Howorka I, Cambas PM, et al. Short device fixation and early mobilization for burst fractures of the thoracolumbar junction. Eur Spine J. 1996;5:112–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00298390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denis F, Armstrong GWD, Searls K, et al. Acute thoracolumbar burst fractures in the absence of neurologic deficit: a comparison between operative and nonoperative treatment. Clin Orthop. 1984;189:142–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farcy JP, Weidenbaum M, Glassman SD. Sagittal index in management of thoracolumbar burst fractures. Spine. 1990;15(9):958–965. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199009000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frankel HL, Hancock DO, Hyslop G, et al. The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia. Paraplegia. 1969;7:179–192. doi: 10.1038/sc.1969.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gertzbein SD, Court-Brown CM, Marks P, et al. The neurologic outcome following surgery for spinal fractures. Spine. 1988;13:641–644. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurr KR, McAfee PC. Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation in adults. A preliminary report. Spine. 1988;13:510–520. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198805000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto T, Kaneda K, Abumi K. Relationship between traumatic spinal canal stenosis and neurological deficits in thoracolumbar burst fractures. Spine. 1988;13:1268–1272. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneda K, Taneichi H, Abumi K, et al. Anterior decompression and stabilization with the Kaneda device for thoracolumbar burst fractures associated with neurological deficits. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(1):69–83. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199701000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katonis PG, Kontakis GM, Loupasis GA, et al. Treatment of unstable thoracolumbar and lumbar spine injuries using Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation. Spine. 1999;24(22):2352–2357. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim NH, Lee HM, Chun IM. Neurologic injury and recovery in patients with burst fracture of the thoracolumbar spine. Spine. 1999;24:290–293. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199902010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirkpatrick JS, Wilber RG, Likavec M, et al. Anterior stabilization of thoracolumbar burst fractures using the Kaneda device: a preliminary report. Orthopedics. 1995;18:673–678. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19950701-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knop C, Bastian L, Lange U, et al. Complications in surgical treatment of thoracolumbar injuries. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(3):214–226. doi: 10.1007/s00586-001-0382-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knop C, Fabian HF, Bastian L, et al. Fate of the transpedicular intervertebral bone graft after posterior stabilisation of thoracolumbar fractures. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(3):251–257. doi: 10.1007/s00586-001-0360-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knop C, Fabian HF, Bastian L, et al. Late results of thoracolumbar fractures after posterior instrumentation and transpedicular bone grafting. Spine. 2001;26(1):88–99. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langrana NA, Harten RD, Lin DC, et al. Acute thoracolumbar burst fractures: a new view of loading mechanisms. Spine. 2002;27(5):498–508. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200203010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leferink VJ, Zimmerman KW, Veldhuis EF, et al. Thoracolumbar spinal fractures: radiological results of transpedicular fixation combined with transpedicular cancellous bone graft and posterior fusion in 183 patients. Eur Spine J. 2001;10(6):517–523. doi: 10.1007/s005860100319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li KC, Hsieh CH, Lee CY, et al. Transpedicle body augmenter: a further step in treating burst fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;436:119–125. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000158316.89886.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magerl F, Aebi M, Gertzbein SD, et al. A comprehensive classification of thoracic and lumbar injuries. Eur Spine J. 1994;3:184–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02221591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCormack T, Karaikovic E, Gaines RW. The load sharing classification of spine fractures. Spine. 1994;19(15):1741–1744. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199408000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLain RF, Sparling E, Benson DR. Early failure of short-segment pedicle instrumentation of thoracolumbar fractures. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(2):162–167. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moon MS, Choi WT, Moon YW, et al. Stabilisation of fractured thoracic and lumbar spine with Cotrel-Dubousset instrument. J Orthop Surg. 2003;11(1):59–66. doi: 10.1177/230949900301100113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Müller U, Berlemann U, Sledge J, et al. Treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurologic deficit by indirect reduction and posterior instrumentation: bisegmental stabilization with monosegmental fusion. Eur Spine J. 1999;8(4):284–289. doi: 10.1007/s005860050175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker JW, Lane JR, Karaikovic EE, et al. Successful short-segment instrumentation and fusion for thoracolumbar spine fractures: a consecutive 4 1/2-year series. Spine. 2000;25(9):1157–1170. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200005010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanderson PL, Fraser RD, Hall DJ, et al. Short segment fixation of thoracolumbar burst fractures without fusion. Eur Spine J. 1999;8(6):495–500. doi: 10.1007/s005860050212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasso RC, Best NM, Reilly TM, et al. Anterior-only stabilization of three-column thoracolumbar injuries. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:7–14. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000137157.82806.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaccaro AR, Nachwalter RS, Klein GR, et al. The significance of thoracolumbar spinal canal size in spinal cord injury patients. Spine. 2001;26(4):371–376. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verlaan JJ, Helden WH, Oner FC, et al. Balloon vertebroplasty with calcium phosphate cement augmentation for direct restoration of traumatic thoracolumbar vertebral fractures. Spine. 2002;27(5):543–548. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200203010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wessberg P, Wang Y, Irstam L, et al. The effect of surgery and remodelling on spinal canal measurements after thoracolumbar burst fractures. Eur Spine J. 2001;10(1):55–63. doi: 10.1007/s005860000194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willen JAG, Gaekwad UH, Kakulas BA. Burst fractures in the thoracic and lumbar spine: a clinico-neuropathologic analysis. Spine. 1989;14:1316–1323. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wood KB, Bohn D, Mehbod A. Anterior versus posterior treatment of stable thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurologic deficit: a prospective, randomized study. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:15–23. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000132287.65702.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yazici M, Atilla B, Tepe S, et al. Spinal canal remodeling in burst fractures of the thoracolumbar spine: a computerized tomographic comparison between operative and nonoperative treatment. J Spinal Disorders. 1996;9(5):409–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]