Abstract

Background

Phthalate esters like n-butyl benzyl phthalate (BBP) are widely used plasticizers. BBP has shown endocrine-disrupting properties, thus having a potential effect on hormone-sensitive tissues. The aim of this study is to determine the effect of neonatal/prepubertal exposure (post-natal days 2–20) to BBP on maturation parameters and on the morphology, proliferative index and genomic signature of the rat mammary gland at different ages of development (21, 35, 50 and 100 days).

Results

Here we show that exposure to BBP increased the uterine weight/body weight ratio at 21 days and decreased the body weight at time of vaginal opening. BBP did not induce significant changes on the morphology of the mammary gland, but increased proliferative index in terminal end buds at 35 days and in lobules 1 at several ages. Moreover, BBP had an effect on the genomic profile of the mammary gland mainly at the end of the exposure (21 days), becoming less prominent thereafter. By this age a significant number of genes related to proliferation and differentiation, communication and signal transduction were up-regulated in the glands of the exposed animals.

Conclusion

These results suggest that BBP has an effect in the gene expression profile of the mammary gland.

Background

Butyl benzyl phthalate (BBP) is a plasticizer commonly used in pipes, vinyl floor tiles, vinyl foams, and carpet backing, and to a minor extent, in cellulose plastics and polyurethane [1]. This compound has shown to be weakly estrogenic [2], and to induce adverse effects on the development of male reproductive system [3-5], thus acting as an endocrine disruptor. Adult BBP intake has been estimated at 2 μg/kg body weight/day and it has been stated that exposure to infants and children could be up to three-fold higher [1]. Environmental endocrine disruptors are of growing concern due to the potential impact on human health. Actually, BBP is one of the phthalates selected by the National Toxicology Program (NTP) Center for the Evaluation of Risks to Human Reproduction (CERHR), because of its high production volume, potential for human exposure from their widespread use and occurrence within the environment, concern to the public, and published evidence of reproductive or developmental toxicity [6]. The evaluation concluded that there was negligible concern for adverse reproductive effects in exposed men, but data was insufficient to reach conclusions on possible reproductive effects in exposed women [6]. Nevertheless, the European Commission has banned BBP from toys and child care items at concentrations of greater than 0,1% by mass of the plasticized material [7] and new data is providing demonstration of possible developmental effects in humans [8]. Urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites in pregnant mothers, including the major BBP metabolite monobenzyl phthalate, have been inversely correlated to anogenital distance among male infants [8]. Moreover an etiological association of serum BBP concentration with endometriosis has been suggested, as severity of endometriosis was strongly correlated with BBP concentration in blood [9]. Although more data is needed regarding the possible effects of this compound on human health, experimental studies have given evidence of an antiandrogenic effect of BBP and monobenzyl phthalate. Prenatal and prepubertal exposure of rats to such compounds induced significant alterations on reproductive system of males, like undescended testes, decrease in the anogenital distance and other malformations of the external genitalia, sex accessory glands, epididymis and testes [3-5]. It has also been reported a decrease in the weight of the ovaries in females exposed during adulthood, as well as changes in the offspring of exposed rats, including a decrease of the body weight of male and female at birth and an increase in the anogenital distance in females [10]. All these changes are compatible with an endocrine disrupting action of BBP.

Endocrine disruptors have also been suggested to contribute to the development of hormone-dependent cancers [11]. Although the risk for cancer is multifactorial, there is substantial contribution of environmental factors, including diet and environmental chemicals. Breast cancer is an estrogen-dependent malignancy with a significant mortality in women worldwide [12]. Changes in the hormonal environment during critical stages of development can modify the architecture and biological characteristics of the mammary gland and thus affect the future susceptibility to develop breast cancer [13,14]. The effects of environmental endocrine disruptors seem to be dependent on the time when the exposure occurs. Diethylstilbestrol has been associated to increased or decreased susceptibility for chemically-induced mammary cancer in rats depending on the period of exposure [15,16].

The present study is designed to determine the effects of neonatal and prepubertal exposure to BBP on rat mammary gland at different stages of development using morphological parameters of gland differentiation [13,14], proliferative index and the genomic expression profile. Here we report that BBP has an effect on the gene expression profile of the mammary gland.

Results

Maturation parameters

Neonatal/prepubertal exposure to BBP did not affect body weight, uterine weight or day at vaginal opening. The uterine to body weight ratios were significantly increased in the exposed animals at 21 days of age (Table 1). BBP exposure did not modify the day at vaginal opening (control group: 30.46 ± 0.13 days; BBP group: 30.44 ± 0.11 days), but decreased significantly (p < 0.05) the body weight at that day (control group: 101.96 ± 1.09 g; BBP group: 97.26 ± 1.49 g).

Table 1.

Parameters for post-natal maturation and development

| 21 days | 35 days | 50 days | 100 days | |

| Uterine weight (mg) | ||||

| Control | 30.0 ± 1.4 | 167 ± 27 | 288 ± 17 | 409 ± 20 |

| BBP | 36.0 ± 2.1 | 207 ± 16 | 319 ± 24 | 429 ± 19 |

| Uterine weight/BW (mg/g) | ||||

| Control | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 1.27 ± 0.20 | 1.48 ± 0.08 | 1.31 ± 0.07 |

| BBP | 0.65 ± 0.04* | 1.56 ± 0.13 | 1.65 ± 0.10 | 1.39 ± 0.04 |

| Development of the mammary gland | ||||

| Number of TEB | ||||

| Control | 39.5 ± 2.32 | 30.4 ± 5.22 | 18.3 ± 3.71 | 0.22 ± 0.22 |

| BBP | 40.0 ± 4.68 | 30.2 ± 5.78 | 22.7 ± 3.16 | 0.40 ± 0.40 |

| Number of TD | ||||

| Control | 24.5 ± 1.65 | 38.2 ± 4.17 | 41.1 ± 3.40 | 57.3 ± 5.21 |

| BBP | 25.9 ± 2.52 | 33.5 ± 4.08 | 46.6 ± 7.31 | 61.8 ± 5.41 |

| Number of AB | ||||

| Control | 8.0 ± 1.87 | 14.9 ± 1.08 | 10.1 ± 2.04 | 0.2 ± 0.22 |

| BBP | 5.7 ± 1.20 | 13.7 ± 1.65 | 8.9 ± 1.05 | 0.2 ± 0.20 |

| Number of Lob1 | ||||

| Control | 0 | 30.1 ± 4.58 | 43.4 ± 5.74 | 42.7 ± 6.41 |

| BBP | 0 | 39.0 ± 7.29 | 42.9 ± 4.43 | 46.2 ± 8.64 |

Maturation parameters and histoarchitectural study of the mammary gland for controls and rats exposed neonatally/prepubertally to BBP. Results are indicated as mean ± SEM. BW: body weight. *: significantly different compared to control group (p < 0.05).

Mammary gland architecture

Histoarchitectural analysis of the mammary gland was performed by determining the number of specific epithelial structures at 21, 35, 50 and 100 days. The number of undifferentiated TEB decreased from 21 to 100 days in both control and BBP treated animals, while the TDs and Lob1 increased over time. Neonatal/prepubertal exposure to BBP did not modify significantly the number of these epithelial structures when compared to control groups (Table 1).

Proliferative index of the mammary gland

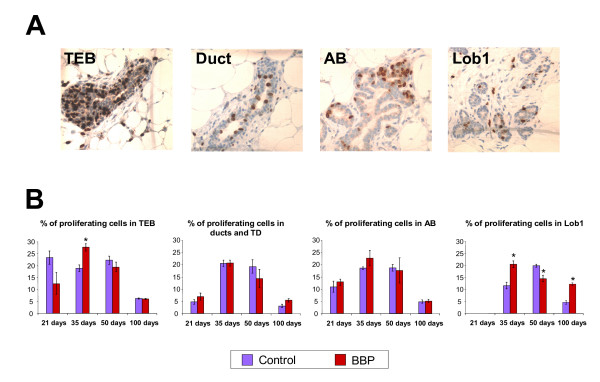

BrdU incorporation into the DNA was used as an index of cell proliferation (Figure 1). TEB from BBP exposed rats had significantly (p < 0.05) higher proliferation index than controls by 35 days, whereas in TD and AB the differences were not significant. The proliferative index of Lob1 from controls increased from 35 to 50 days and decreased at 100 days, while in BBP exposed rats this structure showed maximum index of proliferation at 35 days and decreased thereafter, showing significant differences when compared to controls at all these ages (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proliferative index analyses of the mammary gland. A: Immunohistochemical detection of BrdU incorporation in proliferating cells (brown cells) in the epithelial structures TEB, TD and ducts, AB and Lob1. Olympus BX40 microscope with 40× objective. B: Proliferative index (mean ± SEM) in each epithelial structure at 21, 35, 50 and 100 days of age. *: significantly different compared to control group (p < 0.05).

Gene expression analysis by microarrays

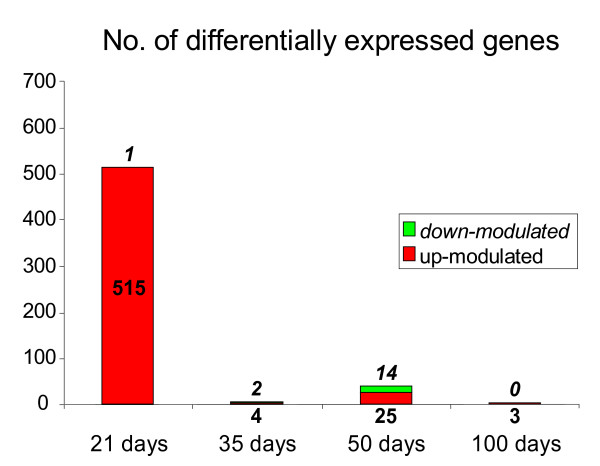

Neonatal/prepubertal exposure to BBP induced changes in the gene expression pattern of the mammary gland mainly by 21 days, just after the end of the treatment, and the number of modulated genes was low thereafter (Figure 2). In 21 days-old rats, BBP exposure resulted in the up-regulation of 515 genes, 141 of which were known, and included genes related to morphogenesis and cell differentiation, transcription factors, cell proliferation, response to stress, signal transduction, metabolism, transport and cell organization (Table 2). There was only one down-regulated gene (gad1). At 35 days of age the number of up-regulated genes decreased significantly to four unknown; two genes were down-regulated (one known -gad1-). By 50 days of age, 25 genes were up-regulated (10 known), and 14 genes were down-regulated (eight known). In the 100 day-old group, two known and one unknown genes were up-modulated (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Genomic changes induced by BBP. Number of differentially expressed genes in the mammary glands of rats exposed neonatally/prepubertally to BBP when compared to controls at different ages. Genes were obtained by confident analysis of microarrays data at p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Microarrays results

| Gene name | Symbol | Fold change BBP/Control | Gene ID |

| 21 days | |||

| Up-regulated genes | |||

| Morphogenesis, organogenesis and cell differentiation | |||

| Cadherin 1 | Cdh1 | 2.21 | NM_031334 |

| Cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 3 | Celsr3 | 2.16 | NM_031320 |

| Cardiotrophin 1 | Ctf1 | 1.98 | NM_017129 |

| Early growth response 2 | Egr2 | 2.03 | NM_053633 |

| Endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 | Esm1 | 1.91 | NM_022604 |

| Forkhead box G1 | Foxg1 | 2.21 | NM_012560 |

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) B receptor 1 | Gabbr1 | 2.14 | AA817879 |

| Glutamate receptor, metabotropic 5 | Grm5 | 2.52 | NM_017012 |

| Glypican 2 (cerebroglycan) | Gpc2 | 1.83 | NM_138511 |

| NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 2 | Nqo2 | 1.94 | AW918463 |

| Odd Oz/ten-m homolog 2 (Drosophila) | Odz2 | 2.15 | NM_020088 |

| Parathyroid hormone-like peptide | Pthlh | 2.03 | NM_012636 |

| Pregnancy-induced growth inhibitor | Okl38 | 2.29 | NM_138504 |

| RAS-like family 11 member B | Rasl11b | 1.96 | BQ202027 |

| Tenascin R | Tnr | 1.93 | NM_013045 |

| Wilms tumor 1 | Wt1 | 2.77 | NM_031534 |

| Other transcription factors | |||

| CUG triplet repeat, RNA-binding protein 2 | Cugbp2 | 2.00 | BE112513 |

| Forkhead box A1 (Hnf3a) | Foxa1 | 2.24 | NM_012742 |

| HNF-3/forkhead homolog-1 (Hfh1) | Hfh1 | 2.08 | NM_022858 |

| Jun dimerization protein 2 | Jundp2 | 2.05 | NM_053894 |

| Nuclear transcription factor-Y gamma | Nfyc | 2.26 | NM_012866 |

| TEA domain family member 2 | Tead2 | 1.87 | AI043589 |

| Transcription elongation factor A (SII), 2 | Tcea2 | 1.99 | NM_057098 |

| Transcription factor 2 | Tcf2 | 2.04 | NM_013103 |

| Transcription factor 4 | Tcf4 | 2.13 | BF398507 |

| Cell proliferation | |||

| Alpha-2-glycoprotein 1, zinc | Azgp1 | 2.08 | NM_012826 |

| Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II beta subunit | Camk2b | 1.83 | NM_021739 |

| Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | Cxcl10 | 1.84 | NM_139089 |

| Insulin receptor substrate 2 | Irs2 | 2.28 | CB547418 |

| Neutrophil cytosolic factor 1 | Ncf1 | 2.64 | NM_053734 |

| Platelet-derived growth factor, C polypeptide | Pdgfc | 1.94 | NM_031317 |

| Upregulated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3 | Txnip | 2.58 | CB548021 |

| Response to stress | |||

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor | Ahr | 1.95 | NM_013149 |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 | Ccl5 | 2.05 | NM_031116 |

| Fc receptor, IgE, low affinity II, alpha polypeptide | Fcer2a | 1.94 | NM_133550 |

| Heat shock 27 kD protein family, member 7 | Hspb7 | 2.20 | CB606395 |

| Heat shock factor 2 | Hsf2 | 2.43 | NM_031694 |

| Myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 | Mcl1 | 1.84 | BF553322 |

| Nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible | Nos2 | 1.83 | NM_012611 |

| Oxidized low density lipoprotein (lectin-like) receptor 1 | Oldlr1 | 2.09 | NM_133306 |

| Peptidoglycan recognition protein 1 | Pglyrp1 | 1.99 | NM_053373 |

| Thioredoxin reductase 1 | Txnrd1 | 2.24 | NM_031614 |

| Signal transduction | |||

| 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2A | Htr2a | 1.96 | NM_017254 |

| Activin receptor interacting protein 1 | Acvrip1 | 2.24 | NM_053621 |

| Agouti | A | 2.18 | NM_052979 |

| Angiotensin receptor-like 1 | Agtrl1 | 2.06 | NM_031349 |

| Growth factor receptor bound protein 2-associated protein 2 | Gab2 | 1.92 | NM_053417 |

| Growth hormone releasing hormone | Ghrh | 1.98 | NM_031577 |

| Guanylate cyclase 1, soluble, beta 2 | Gucy1b2 | 1.91 | NM_012770 |

| MAS-related G-protein coupled receptor, member G | Mrgprg | 2.80 | CB545776 |

| Mcf.2 transforming sequence-like | Mcf2l | 2.24 | NM_053951 |

| Membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 2 | Ms4a2 | 1.88 | NM_012845 |

| Protein kinase, cAMP-dependent, regulatory, type 2, alpha | Prkar2a | 2.01 | AW919085 |

| Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 1 | Arhgef1 | 2.09 | NM_021694 |

| Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 7 | Arhgef7 | 1.88 | CA512056 |

| Cell-cell signaling | |||

| 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase | Abat | 1.85 | BF393840 |

| Discs, large (Drosophila) homolog-associated protein 2 | Dlgap2 | 2.38 | NM_053901 |

| Gap junction membrane channel protein beta 5 | Gjb5 | 1.89 | NM_019241 |

| Metabolism | |||

| 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | 11-HSDIB | 1.93 | M77835.1 |

| Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase alpha | Acaca | 2.09 | NM_022193 |

| Aldehyde oxidase 1 | Aox1 | 2.39 | NM_019363 |

| Alpha 1,2-fucosyltransferase C gene | Ftc | 1.98 | NM_020541 |

| Apolipoprotein A-I | Apoa1 | 2.50 | NM_012738 |

| Cholinergic receptor, muscarinic 3 | Chrm3 | 2.08 | NM_012527 |

| Diazepam binding inhibitor-like 5 | Dbil5 | 1.84 | NM_021596 |

| Elastase 2 | Ela2 | 2.03 | NM_012553 |

| Fatty acid binding protein 3 | Fabp3 | 2.14 | NM_024162 |

| FK506 binding protein 1b | Fkbp1b | 2.01 | NM_022675 |

| Glucosidase, alpha; acid (glycogen storage disease type II) | Gaa | 2.30 | CB544857 |

| Hydroxy-delta-5-steroid dehydrogenase, 3 beta- and steroid delta-isomerase 1 | Hsd3b1 | 1.94 | AI060276 |

| NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex 5 | Ndufa5 | 2.03 | BQ210630 |

| Nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase | Nnt | 1.95 | CB544867 |

| Peptide/histidine transporter PHT2 | Slc15a3 | 1.92 | NM_139341 |

| Phosphate cytidylyltransferase 1, choline, alpha isoform | Pcyt1a | 2.49 | NM_078622 |

| Procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 1 | Plod1 | 2.43 | AA944202 |

| Proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, ATPase 3 | Psmc3 | 1.90 | NM_031595 |

| Protein kinase C, gamma | Prkcc | 2.04 | NM_012628 |

| Serine/threonine kinase 2 | Slk | 1.89 | AA955942 |

| Small glutamine rich protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 | Sgtb | 2.03 | CB545680 |

| Succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 1.93 | L34821.1 | |

| Transmembrane protease, serine 8 (intestinal) | Tmprss8 | 1.88 | CB544856 |

| Valosin-containing protein | Vcp | 2.44 | CB546610 |

| Transport | |||

| Adducin 1 (alpha) | Add1 | 2.65 | NM_016990 |

| Apolipoprotein A-V | Apoa5 | 2.00 | NM_080576 |

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha polypept. 1 | Chrna1 | 1.88 | NM_024485 |

| CUB and zona pellucida-like domains 1 | Cuzd1 | 2.25 | NM_054005 |

| Epidermal growth factor | Egf | 2.05 | NM_012842 |

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor, gamma 2 | Gabrg2 | 1.87 | AW523484 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, kainate 4 | Grik4 | 2.00 | NM_012572 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDA2D | Grin2d | 1.91 | NM_022797 |

| Olfactory receptor 226 | Olfr41 | 1.90 | NM_031710 |

| Potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 6 | Kcnj6 | 1.84 | NM_013192 |

| RAB10, member RAS oncogene family | Rab10 | 2.33 | CB547865 |

| Rabaptin, RAB GTPase binding effector protein 2 | Rabep2 | 2.07 | NM_058213 |

| Sodium channel, voltage-gated, type II, beta polypeptide | Scn2b | 2.01 | NM_012877 |

| Solute carrier family 12, member 4 | Slc12a4 | 2.38 | BI295055 |

| Solute carrier family 13, member 1 | Slc13a1 | 1.89 | AA818620 |

| Synaptotagmin 8 | Syt8 | 2.48 | NM_053325 |

| Cell organization | |||

| Adaptor-related protein complex 3, mu 2 subunit | Ap3m2 | 2.00 | NM_133305 |

| ATP-dependent, RNA helicase | Ddx52 | 1.84 | NM_053525 |

| Bassoon | Bsn | 1.94 | NM_019146 |

| Cadherin-8 | Cdh8 | 2.42 | AB010436.1 |

| Integrin alpha 5 | Itga5 | 1.94 | CB546515 |

| Myoglobin | Mb | 2.13 | AA964911 |

| Synaptotagmin 1 | Syt1 | 2.14 | AW141251 |

| Trans-golgi network protein 1 | Tgoln2 | 1.93 | NM_138840 |

| Other | |||

| Alpha-1-B glycoprotein | A1bg | 1.84 | NM_022258 |

| Aortic preferentially expressed gene 1 | Apeg1 | 2.53 | CB547339 |

| Arfaptin 1 | LOC60382 | 2.00 | NM_021763 |

| CDC91 cell division cycle 91-like 1 (S.cerevisiae) | Cdc91l1 | 2.57 | BQ193826 |

| Delta-like 1 homolog (Drosophila) | Dlk1 | 2.30 | NM_053744 |

| Glycoprotein, synaptic 2 | Gpsn2 | 1.87 | |

| Guanylate cyclase activator 2A | Guca2a | 2.43 | NM_013118 |

| Heparan sulfate proteoglycan, perlecan domain I | Cd44 | 2.20 | U56859.1 |

| Heat-responsive protein 12 | Hrsp12 | 1.92 | NM_031714 |

| Insulin-like 6 | Insl6 | 1.95 | NM_022583 |

| Kinesin-related protein KRP5 | KRP5 | 1.99 | AF035954.1 |

| Luteinizing hormone beta | Lhb | 1.99 | U25802 |

| Ly6-C antigen | Ly6c | 2.02 | NM_020103 |

| Mitochondrial capsule selenoprotein | Mcsp | 2.46 | NM_031536 |

| Neural visinin-like Ca2+-binding protein type 2 | Nvjp2 | 1.95 | NM_017357 |

| NIMA related kinase 2 | Nek2 | 1.86 | AF352021.1 |

| Nuclear GTPase PIKE | PIKE | 1.84 | NM_023026 |

| Nucleoporin 98 | Nup98 | 2.18 | NM_031074 |

| Oxytocin receptor | Oxtr | 2.11 | AF380129.1 |

| Olfactory-specific cytochrome P-450 | P-450olf1 | 2.03 | M33296.1 |

| Potassium channel tetramerisation domain containing 13 | Kctd13 | 2.33 | AI045333 |

| Proline-rich protein 15 | Prp15 | 2.24 | NM_012632 |

| RAB8A, member RAS oncogene family | Mel | 2.12 | BC087584 |

| Regucalcin gene promotor region related protein | Rgpr | 2.05 | AB060653 |

| Ribonuclease L (2',5'-oligoisoadenylate synthetase-dependent) | Rnasel | 2.05 | CB546885 |

| Ring finger protein 38 | Oip1 | 1.85 | NM_134467 |

| Serine protease inhibitor | Spin2b | 2.67 | NM_012657 |

| Signal recognition particle 54 kDa | Srp54 | 1.97 | BC079117 |

| Sodium-cotransporter rkST1 | rkST1 | 1.95 | U47673.1 |

| Synaptosomal-associated protein, 91 kDa homolog (mouse) | Snap91 | 2.23 | NM_031728 |

| Telomerase catalytic subunit | 2.61 | AF247818.1 | |

| Titin | Ttn | 1.88 | AF059344.1 |

| Ubiquitin specific protease 11 | Usp11 | 2.51 | CB546595 |

| Zinc finger protein 14 (DZF14) | DZF14 | 1.87 | U78142.1 |

| Zinc finger, DHHC domain containing 7 | Zdhhc7 | 1.83 | AY040615 |

| Down-regulated genes | |||

| Glutamate decarboxylase 1 | Gad1 | -3.65 | NM_017007 |

| 35 days | |||

| Glutamate decarboxylase 1 | Gad1 | -2.69 | NM_017007 |

| 50 days | |||

| Up-regulated genes | |||

| Carboxylesterase 1 | Ces1 | 1.79 | NM_031565 |

| Carboxypeptidase A1 (pancreatic) | Cpa1 | 1.74 | NM_016998 |

| Corticotropin releasing hormone 1 | Crhr1 | 1.79 | NM_030999 |

| Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 5 | Enpp5 | 2.00 | CB544850 |

| Glucagon receptor, transcript variant 2 | Gcgr | 1.74 | NM_172091 |

| Glycoprotein 2 (zymogen granule membrane) | Gp2 | 1.80 | NM_134418 |

| Malic enzyme 1 | Me1 | 1.74 | NM_012600 |

| Nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 1 | Nr4a1 | 2.06 | NM_024388 |

| Transcription elongation factor A2 | Tcea2 | 1.75 | NM_057098 |

| Tryptophan hydroxylase | Tph | 1.93 | X53501.1 |

| Down-regulated genes | |||

| Actinin alpha 3 | Actn3 | -2.76 | NM_133424 |

| Creatine kinase, muscle form | Ckm | -3.64 | NM_012530 |

| Glutamate decarboxylase 1 | Gad1 | -2.69 | NM_017007 |

| Myosin, light polypeptide 2 | Myl2 | -4.90 | NM_012605 |

| Parvalbumin (calcium binding protein) | Pvalb | -2.38 | NM_022499 |

| Titin | Ttn | -2.51 | AF059344.1 |

| Troponin I, skeletal, fast 2 | Tnni2 | -2.46 | NM_017185 |

| Troponin-c | Tnnc2 | -4.77 | AI639532 |

| 100 days | |||

| Translin | Tsn | 2.40 | NM_021762 |

| Whey acidic protein | Wap | 2.87 | NM_053751 |

List of known genes down- and up-regulated in mammary glands of BBP treated rats at 21, 35, 50 and 100 days. Average fold change related to control mammary glands is indicated. Up-regulated genes at 21 days have been sorted by function according to level 4 of Gene Ontology.

Functional analysis of the genes found up-regulated in 21 days-old rats showed some categories that were significantly (p < 0.05) over-represented: cell proliferation and differentiation, signal transduction (TGF-beta signaling pathway, metabotropic glutamate receptor group I pathway, PI3 kinase pathway, endothelin signaling pathway and interleukin signaling pathway) and cell communication, (neuronal activities, anterior/posterior patterning). We also found over-representation of genes coding for cytoskeletal proteins among the down-modulated by 50 days.

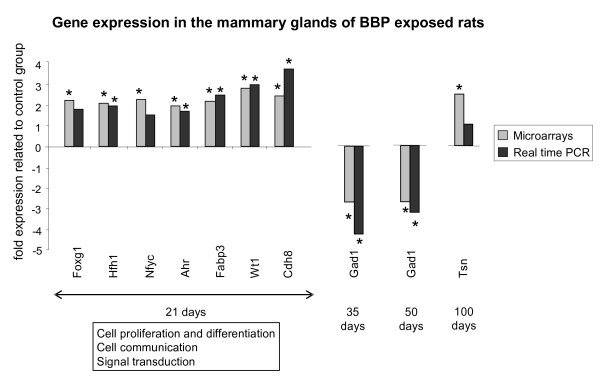

Validation of microarrays by real time RT-PCR

To validate the results from microarrays we have chosen several genes that were differentially expressed in the mammary glands from BBP treated rats: transcription factors related to proliferation and differentiation (Foxg1, Hfh1, Nfyc, Ahr, Wt1, Tsn), other genes related to differentiation (Fabp3), adhesion (Cdh8) and communication (Gad1). We analyzed the gene expression of those genes by real time RT-PCR. Results of the validation are shown in Figure 3. In the BBP exposed animals Foxg1, Hfh1, Nfyc and Ahr were between 1.6- and 2-fold up-regulated in comparison to their gene expression in untreated animals. These differences, although discrete, were statistically significant for Hfh1 and Ahr, and close to significance for the other genes. We also obtained statistically significant increases in the expression of Fabp3, Wt1 and Cadh8. By 35 and 50 days, BBP exposure induced a significant decrease in the expression of Gad1. The decrease of this gene found by microarrays at 21 days as well as the increase in Tsn observed by 100 days of age was not confirmed by real time PCR.

Figure 3.

Comparative expression analyses of selected genes. Gene expression analyses by real time RT-PCR in comparison with results from microarrays. Grey bars represent results obtained in the microarrays, black bars represent results obtained in the real time RT-PCR. Results show the mean fold expression of the treated group related to control group. The functional categories significantly over-represented are indicated (21 days). *: significant differences compared to control group (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to investigate the effects of neonatal/prepubertal exposure to BBP in the rat mammary gland at different times of development. We have characterized the genomic signature of the mammary gland, observing modifications in the gene expression profile mainly at the end of the exposure and fewer changes thereafter. We also studied maturation parameters, finding also alterations compatible with a transitory effect of this environmental compound.

Although it is difficult to determine doses for experimental studies, the dose chosen for this study was based on the work of Singletary et al. [17], where they reported that treatment of female rats with BBP for 7 days prior to dosing with DMBA decreased mammary tumor incidence by 37%. The number of palpable tumors per rat at week 15 was significantly inhibited by 58% and 71% for animals administered BBP at 250 and 500 mg/kg, respectively, compared to controls. Our goal was to determine if neonatal and prepubertal only exposure to BBP would have a direct effect at day 21 and if this treatment would leave permanent alterations on mammary gland maturation, cell proliferation and gene expression at later time points. The offspring were exposed to the BBP via the mother's milk. Considering that the lactating dams were treated with 500 mg BBP/kg BW and this is dissipated in the mother before it makes its way via the milk to the 10 offspring, hence it is estimated that they receive 1/100 to 1/1000 of the mother's dose, i.e. 0,5–5 mg BBP/kg BW/day. This approximation places the rat BBP exposure near the EPA safe dose for humans of 0.2 mg/kg/day [18] and similar to a 2 μg/kg BW/day for adults, and lower than estimated exposure to infants and children (6 μg/kg BW/day) [1].

Neonatal/prepubertal exposure to BBP increased the relative uterine weight at 21 days but not thereafter, and decreased the body weight at day of vaginal opening (approximately day 30). In the literature there are conflicting results regarding the effect of BBP because it showed estrogenic effects in vitro but did not modify the estrogen-modulated gene calbindin-D9k in vivo [19]. However, BBP has also shown to increase the expression of progesterone receptor mRNA, a gene regulated by estrogens, in the preoptic area of adult ovariectomized rats [20]. Exposure to BBP in other phases of development induced alterations in the onset of puberty. Ashby et al. reported advanced vaginal opening by 1.1 days without modifications on uterine weight in rats by effect of prenatal plus prepubertal exposure to BBP, although the authors considered that this result could be related to the variability of the observation or, more interestingly, to an increase in the weight of the BBP treated animals [21]. In two generational studies, Aso et al. reported changes in anogenital distance of female offspring of rats treated with more than 100 mg/kg [22].

Little is known on the effects of BBP on mammary gland, another target of sexual maturity, and the present work indicates that BBP did not induce significant changes in the morphology of that gland, but changed the proliferative index of TEB by 35 days and in Lob1 at 35, 50 and 100 days. Although these modifications are subtle, we cannot rule out that they may have an effect if the mammary gland susceptibility to carcinogenesis, since TEB are the most susceptible epithelial structures to malignant transformation [23] and prevention of chemically-induced mammary carcinomas is accompanied by inhibition of cell proliferation [13,14]. Changes in the proliferative index of Lob1 in BBP exposed animals in comparison to control group can be associated with subtle alterations in mammary development. The proliferation of Lob1 is related to the differentiation of these structures to lobules type 2 [23]. Control group had the highest proliferative index in Lob1 by 50 days, concomitantly with the highest number of Lob1, at the age of profound changes that the mammary gland faces as a result of an intense hormonal activity [13,14]. BBP exposed animals had the maximum mitotic index in Lob1 by 35 days, decreasing by 50 days. In addition, the reduction of proliferation in Lob1 of BBP group by 100 days was not as important as in control group. The significant changes observed are compatible with slight changes in the timing of the breast tissue development by effect of BBP exposure.

We are the first to report that neonatal/prepubertal exposure to BBP induced modifications in the gene expression of the mammary tissue. Whereas the full relevance of these findings requires tumorigenesis studies, the characterization of the genomic signature of the mammary gland could be used as a predictor of the susceptibility to carcinogenesis. This statement is based on previous works in which changes in susceptibility to DMBA-induced carcinogenesis are accompanied by the induction of a specific genomic profile [13,14,24]. Neonatal/prepubertal exposure to BBP induced changes in the genomic profile of the mammary gland, mainly at the end of treatment (21 days) with a focus on genes involved in cell proliferation/differentiation, communication and signal transduction. Some of those genes related to differentiation were validated by real time RT-PCR, as Fabp3 and Wt1. Fabp3 belongs to the family of the fatty acid binding proteins, which have a role in fatty acid transport or metabolism. This member, however, is considered an identical homologue of the mammary-derived growth inhibitor (MDGI), with a role in the differentiation of the mammary gland [25]. MDGI is a suppressor of tumor growth and an inhibitor of tumor cell proliferation [26]. We have previously observed that this gene is up-regulated in the most differentiated structures of the mammary gland (lobules type 4) and silenced in breast cancer progression [27]. Another gene found significantly up-regulated by 21 days is Wt1, which has also been related to development of the mammary gland although its specific function is not well known [28,29]. This gene is essential for the development of the urogenital system but its role in the breast tissue is controversial. Wt1 presents a developmental pattern of expression in normal mammary gland, and changes observed in cell lines and tumors may be indicative of breast-tumor-related perturbations of Wt1 expression [29]. Cadherin 8 (cdh8), also found up-regulated in the exposed animals, is an adhesion molecule with an important role in brain and kidney development and differentiation [30,31]. We have also observed transitional changes in the expression of these three genes by effect of prepubertal exposure to other endocrine disruptor, bisphenol A [32]. Moreover, we also observed changes in the expression of Fabp3 when this endocrine disruptor was administered in utero. Thus, the exposure during the prenatal period to bisphenol A induced up-regulation or down-regulation of Fabp3 depending on the age tested, suggesting a "shift" in the normal development of the mammary gland, while prepubertal exposure to this endocrine disruptor induced a transient up-regulation just at the end of the treatment [32]. Fabp3 mRNA has also been reported as sensitive to the action of other hormone interfering agents, since the antiestrogens tamoxifen and ICI up-regulate its expression by stabilization of the mRNA [33]. These evidences suggest that genes related to differentiation of the mammary gland can be very sensitive to the effects of several compounds that may interfere with hormonal action, suggesting that, even if the effects are not strong enough to modify mammary histoarchitecture, they may change the molecular milieu of the gland.

By 21 days of age we also found a moderate increase in the expression of the transcription factors Foxg1, Hfh1 and Ahr. Foxg1 and Hfh1 have a role in the development and differentiation of several tissues, but to date their function in the mammary gland is unknown [34,35]. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) belongs to the PAS (per-arnt-sim) family of transcription factors. PAS proteins control important physiological processes, as toxicant metabolism, circadian rhythms and hormone signaling [36]. We have previously reported a role of Ahr in mammary differentiation, as an increased expression in primary cultures of Lob3 from parous women compared to primary cultures of Lob1 from nulliparous women breast was observed [37]. Ahr is known to interact with signaling pathways that are mediated by estrogen receptor and other hormone receptors. The mechanisms of Ahr-estrogen receptor crosstalk seem to be complex, and recent studies suggest direct activation of estrogen-regulated target genes by Ahr [38]. Thus, our results suggest that the increase in Ahr could be one of the mechanisms by which BBP treatment exerts the observed transitory effects at 21 days.

We also observed and validated down-regulation of Gad1 by 35 and 50 days of age. This gene codes for the protein Gad67, which catalyzes the production of the neurotransmitter GABA. Gad1 can be regulated by estrogens in rat brain [39,40], and expression changes in discrete regions of the rostral preoptic area during estrous cycle and with age has been described [41]. In addition, Gad1 has also a role in the control of puberty in nonhuman primates [42]. Modifications in the expression of Gad1 has been investigated in relation to some brain disorders, since Gad1 mRNA decreased in prefrontal cortex and other brain areas of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients with psychosis [43]. Experiments in rats have found down-modulation of Gad1 accompanied by hypermethylation of Gad1 promoter very likely mediated by the overexpression of DNA methyltransferase 1 in cortical GABAergic interneurons [44]. Thus, we can consider the possibility that the observed changes in Gad1 are due to an effect of BBP on the methylation of Gad1 promoter. BBP has also shown an effect on the methylation status of other genes in vitro, as the reported demethylation of ERα promoter-associated CpG islands in MCF-7 cells [45]. The GABA-ergic system has been involved in hormonal regulation and pathogenesis of breast cancer, since human and mouse tumors have shown higher GABA level and GAD activity than normal tissue [46]. Hence, although prepubertal exposure to BBP seems to have mainly a transitory effect on the genomic profile of the mammary gland, we cannot discard that subtle changes in the gland may have an effect later in life. Finally, very few genes were regulated by BBP exposure in the oldest age tested (100 days).

Conclusion

In summary, neonatal/prepubertal exposure to BBP had a transitory effect by increasing the relative uterine weight only at the end of exposure. This compound also changed the gene expression profile of the mammary gland mainly at the same age, although long-term subtle alterations can not be ruled out.

Methods

Animals and experimental design

Animals were housed in 12 hour light/dark cycle and controlled temperature in the University of Alabama at Birmingham animal facility. Pregnant Sprague Dawley CD rats (Charles River, Raleigh NC) were bred and maintained on phytoestrogen-free AIN-93G diet (Harlan Teklad, Madison WI). After parturition, litters were adjusted to 10 offspring per mother, and the lactating dams (10 dams per group) were gavaged with 500 mg BBP/kg body weight or an equivalent volume of sesame oil on days 2–20 (Mondays-Fridays only). We used a stock solution of 200 mg BBP/ml sesame oil, and dams were gastric intubated with 2,5 μl BBP/g BW (0.5 ml for a dam of 200 g) each day, preferable each late afternoon. The offspring were weaned at day 21 and continued on AIN-93G diet until day 70 where they were switched to AIN-93M diet. Vaginal opening was assessed as an index of maturation and body weight was recorded from a minimum of 27 female offsprings/group.

Female offspring were processed at 21, 35 ± 1, 50 ± 1 and 100 ± 2 days. For the cycling animals (the latter 3 ages), all females were killed in the estrus phase of the estrous cycle. The day of euthanasia the animals were anesthetized with ketamine (10 mg/100 g)/xylazine (1.5 mg/100 g), the fourth mammary glands were rapidly dissected and frozen for microarrays analysis (1 female offspring from each litter at each time point). Transsection of the aorta was performed after the tissues were properly collected. From another set of females from each litter, mammary glands were dissected for whole mount preparation and gland differentiation analysis, and the contralateral mammary glands were paraffin-blocked for cell proliferations studies. Ten glands representing all litters per group at each time point were used for each of the molecular, morphological and proliferation analyses. Uterine weight was also recorded at day of sacrifice and uterine weight/body weight ratios were calculated for each animal. Differences among groups were analyzed using Tukey's Test (p < 0.05). All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the University of Alabama at Birmingham Guidelines for Animal Use and Care.

Mammary whole mounts analysis

The excised mammary glands were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin followed by de-fatting in acetone. The tissues were stained in alum carmine overnight and dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol. The glands were cleared in xylene and coverslipped with mounting media. Analysis of mammary epithelial structures (terminal end buds -TEBs-, terminal ducts -TDs-, alveolar buds -ABs- and lobules type 1 -Lob1-) was made through visual evaluation and computer-assisted image analysis using MetaMorph Imaging System (Universal Imaging Corporation, Downingtown PA). The outer 5-mm margin of the mammary whole mount was examined by light microscopy using the criteria of Russo and Russo [23]. This area represents the location of most actively proliferating TEB structures of the mammary gland for a young virgin rat [47], The total number of each epithelial structure was determined under an Olympus microscope using a 40× magnification objective. The collected data were analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t-tests.

Proliferative index analysis

Two hours before euthanasia animals were weighed and injected i.p. with 100 mg bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) per kg body weight. The fourth abdominal mammary glands were excised and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 4 μm thickness. Tissue sections were mounted on positively charged slides and immunocytochemically reacted with anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) using an automatic slide stainer (BioGenex). The incorporation of BrdU in the mammary glands was visualized using the streptavidin-biotin labeling system with 3, 3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as a color reaction substrate (BioGenex). The proliferative index was determined quantitatively using an Olympus BX40 microscope (60× magnification objective) as the percentage of DAB positive cells within each specific epithelial structure, i.e., TEBs, TD and ducts, ABs and Lob1. All cells in each structure were counted blinded to the groups. A minimum of 1,000 cells per tissue sample was examined. Data from different groups were analyzed by unpaired t-tests.

Characterization of the genomic profile

Gene expression profile was determined from total RNA using Agilent 60-mer oligo-microarrays slides containing 22,000 sequences. RNAs from the mammary glands were extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). The quantity and purity of each RNA sample was determined from the 260- and 280-nm absorbance, and its integrity was determined (2100 BioAnalyzer; Agilent Technologies Inc., Palo Alto, CA). Only high quality RNA, with absorbance 260/280 greater than 1.8 and RNA integrity number (RIN) greater than 8 were considered for further analysis. 250 ng of pooled RNA from two-three different mammary glands were fluorescent labeled with Agilent Low Input RNA Fluorescent Linear Amplification Kit (Agilent Technologies) in the presence of Cy3-dCTP or Cy5-dCTP (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA), and purified using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA).

Four separate experiments, each including two to three mammary gland cRNA pool were performed at each time point studied. 750 ng of Cy3 labeled control cRNA and 750 ng of Cy5 labeled BBP group cRNA were used to hybridize each slide at 60°C for 18 hours. Slides were washed and fluorescence images were captured with a laser scanner (Agilent Technologies). The obtained images were analyzed with Feature extraction software (Agilent Technologies) to verify the quality of the hybridization by the report of the outlier data.

Feature extraction software automatically flagged non-uniform features and population outliers, considering acceptable outlier numbers lower than 5% of total feature number on the array. Intensity of each fluorescent signal was quantified by ImaGene 5.6 software (BioDiscovery Inc., El Segundo, CA) and statistically analyzed using GeneSight 4.1.6 software (BioDiscovery) with Lowess normalization considering the arrays per group as replicates. We determined the genes with ≥ 1.4-fold differences by confidence analyses at p < 0.05 following manufacturer's recommendations. We performed functional analysis of the genes obtained as modulated by BBP exposure using PANTHER (Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships). Genes were annotated according to known biological process, molecular function and biological pathways. The number of genes in each category was statistically compared to NCBI: R. norvegicus genes database to look for under- and over-represented functional categories using the binomial test [48] and the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Genes with known function were also classified using Gene Ontology database.

Gene expression analysis by real-time RT-PCR

Several genes found differentially expressed in the mammary glands of rats exposed to BBP were chosen for confirmation by real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). Beta-actin was used as a control. All RT-PCR reactions were performed on the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the fluorescent TaqMan methodology (TaqMan One Step RT-PCR Master Mix Reagents, Applied Biosytems) following manufacturer's protocol. 100 ng of total RNA in 50 μl of final volume was reverse-transcribed (30 min at 48°C) and amplified following 1 cycle of 10 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 15 s denaturation at 95°C and 60 s annealing at 60°C. Each gene was normalized to beta-actin and data was analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Abbreviations

AB: alveolar bud;

BBP: butyl benzyl phthalate;

Lob1: lobule type 1;

PCR: polymerase chain reaction;

RT: reverse transcription;

TD: terminal duct;

TEB: terminal end bud.

Authors' contributions

RM performed the molecular experiments and contributed in the writing of the manuscript. RW carried out the morphological and proliferative index analyses. IHR participated in the design and coordination of the study, and helped in the writing of the manuscript. DAM and GAB participated in the analysis of the microarrays. CAL participated in the coordination of the study and performed the animal assays. JR conceived of the study, coordinated the work and helped in the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This research work was supported by the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Centers grant number U01 ES/CA 12771 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), and the National Cancer Institute (NCI), NIH, DHHS. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS or NCI, NIH.

Contributor Information

Raquel Moral, Email: Raquel.Moral@uab.es.

Richard Wang, Email: rwang50290@aol.com.

Irma H Russo, Email: Irma.Russo@fccc.edu.

Daniel A Mailo, Email: dmailo@yahoo.com.

Coral A Lamartiniere, Email: Coral@uab.edu.

Jose Russo, Email: J_russo@fccc.edu.

References

- IPCS . In: Concise international chemical assessment document 17 - Butyl benzyl phthalate. WHO , editor. Geneva, Switzerland ; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Okubo T, Suzuki T, Yokoyama Y, Kano K, Kano I. Estimation of estrogenic and anti-estrogenic activities of some phthalate diesters and monoesters by MCF-7 cell proliferation assay in vitro. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26:1219–1224. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M, Miyawaki E. Effects on development of the reproductive system in male offspring of rats given butyl benzyl phthalate during late pregnancy. Reprod Toxicol. 2002;16:71–76. doi: 10.1016/S0890-6238(01)00200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M, Miyawaki E, Hirose A, Kamata E. Decreased anogenital distance and increased incidence of undescended testes in fetuses of rats given monobenzyl phthalate, a major metabolite of butyl benzyl phthalate. Reprod Toxicol. 2003;17:407–412. doi: 10.1016/S0890-6238(03)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray LE, Jr., Ostby J, Furr J, Price M, Veeramachaneni DN, Parks L. Perinatal exposure to the phthalates DEHP, BBP, and DINP, but not DEP, DMP, or DOTP, alters sexual differentiation of the male rat. Toxicol Sci. 2000;58:350–365. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/58.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NTP NTP-CERHR Monograph on the Potential Human Reproductive and Developmental Effects of Butyl Benzyl Phthalate (BBP) NTP CERHR MON. 2003. pp. i–III90. [PubMed]

- European-Commission Directive 2005/84/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2005. Official Journal of the European Union. 2005.

- Swan SH, Main KM, Liu F, Stewart SL, Kruse RL, Calafat AM, Mao CS, Redmon JB, Ternand CL, Sullivan S, Teague JL. Decrease in anogenital distance among male infants with prenatal phthalate exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1056–1061. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy BS, Rozati R, Reddy BV, Raman NV. Association of phthalate esters with endometriosis in Indian women. Bjog. 2006;113:515–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao T, Ohta R, Marumo H, Shindo T, Yoshimura S, Ono H. Effect of butyl benzyl phthalate in Sprague-Dawley rats after gavage administration: a two-generation reproductive study. Reprod Toxicol. 2000;14:513–532. doi: 10.1016/S0890-6238(00)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum LS, Fenton SE. Cancer and developmental exposure to endocrine disruptors. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:389–394. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althuis MD, Dozier JM, Anderson WF, Devesa SS, Brinton LA. Global trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality 1973-1997. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:405–412. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo IH, Russo J. Role of hormones in cancer initiation and progression. J Mam Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1998;3:49–61. doi: 10.1023/A:1018770218022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo J, Russo IH. Role of differentiation in pathogenesis and prevention of breast cancer. Endrocr Related Cancer. 1997;4:7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Boylan ES, Calhoon RE. Mammary tumorigenesis in the rat following prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol and postnatal treatment with 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1979;5:1059–1071. doi: 10.1080/15287397909529814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamartiniere CA, Holland MB. Neonatal diethylstilbestrol prevents spontaneously developing mammary tumors. In: Li JJ, Nandi S, Li SA, editor. Proceed First Intern Symp Hormonal Carcinogenesis. New York , Springer-Verlag; 1992 . pp. 305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Singletary K, MacDonald C, Wallig M. The plasticizer benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP) inhibits 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced rat mammary DNA adduct formation and tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1669–1673. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.8.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US-EPA . Butyl benzyl phthalate (CASRN 85-68-7) Washington, DC , U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2003. p. http://www.epa.gov/iris/subst/0293.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Hong EJ, Ji YK, Choi KC, Manabe N, Jeung EB. Conflict of estrogenic activity by various phthalates between in vitro and in vivo models related to the expression of Calbindin-D9k. J Reprod Dev. 2005;51:253–263. doi: 10.1262/jrd.16075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabashi T, Kawaguchi M, Kimura F. The endocrine disrupters butyl benzyl phthalate and bisphenol A increase the expression of progesterone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in the preoptic area of adult ovariectomized rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2001;74:77–81. doi: 10.1159/000054672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby J, Tinwell H, Lefevre PA, Odum J, Paton D, Millward SW, Tittensor S, Brooks AN. Normal sexual development of rats exposed to butyl benzyl phthalate from conception to weaning. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1997;26:102–118. doi: 10.1006/rtph.1997.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aso S, Ehara H, Miyata K, Hosyuyama S, Shiraishi K, Umano T, Minobe Y. A two-generation reproductive toxicity study of butyl benzyl phthalate in rats. J Toxicol Sci. 2005;30 Spec No.:39–58. doi: 10.2131/jts.30.S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo J, Russo IH. DNA labeling index and structure of the rat mammary gland as determinants of its susceptibility to carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1978;61:1451–1459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balogh GA, Heulings R, Mailo DA, Russo PA, Sheriff F, Russo IH, Moral R, Russo J. Genomic signature induced by pregnancy in the human breast. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:399–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Spitzer E, Kenney N, Zschiesche W, Li M, Kromminga A, Muller T, Spener F, Lezius A, Veerkamp JH, et al. Members of the fatty acid binding protein family are differentiation factors for the mammary gland. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1097–1109. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.4.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh HT, Larsson C, Narod S, Pollak M. Tumor suppressor activity of the gene encoding mammary-derived growth inhibitor. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2225–2231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YF, Russo IH, Ao X, Russo J. Mammary derived growth inhibitor (MDGI) cloned from human breast epithelial cells is expressed in fully differentiated lobular structures. Int J Oncol. 1997;11:5–11. doi: 10.3892/ijo.11.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb DM, Evron E, Patel CB, Sharma PM, Niranjan B, Buluwela L, Weitzman SA, Korz D, Sukumar S. Wilms' tumor suppressor gene (WT1) is expressed in primary breast tumors despite tumor-specific promoter methylation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:921–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein GB, Van Horn K, Strickland P, Roberts CT, Jr., Daniel CW. Altered expression of the WT1 wilms tumor suppressor gene in human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8132–8137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke S, Mueller CA, Markovic-Lipkovski J, Puch S, Miosge N, Becker V, Mueller GA, Klein G. Expression of cadherin-8 in renal cell carcinoma and fetal kidney. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:327–334. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korematsu K, Nishi T, Okamura A, Goto S, Morioka M, Hamada J, Ushio Y. Cadherin-8 protein expression in gray matter structures and nerve fibers of the neonatal and adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1998;87:303–315. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moral R, Balogh GA, Mailo D, Russo IH, Lamartiniere C, Russo J. Effect of the contaminant bisphenol A (BPA) on the genomic signature of the rat mammary gland. Proc Amer Assoc Cancer Res. 2005;46:491–492. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh H, Pollak M. Stabilization of mammary-derived growth inhibitor messenger RNA by antiestrogens. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:2151–2156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong HK, Noveroske JK, Headon DJ, Liu T, Sy MS, Justice MJ, Chakravarti A. The winged helix/forkhead transcription factor Foxq1 regulates differentiation of hair in satin mice. Genesis. 2001;29:163–171. doi: 10.1002/gene.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martynoga B, Morrison H, Price DJ, Mason JO. Foxg1 is required for specification of ventral telencephalon and region-specific regulation of dorsal telencephalic precursor proliferation and apoptosis. Dev Biol. 2005;283:113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu YZ, Hogenesch JB, Bradfield CA. The PAS superfamily: sensors of environmental and developmental signals. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:519–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Russo IH, Russo J. Difference in gene expression profile in breast epithelial cells from women with different reproductive history. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:933–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman A. Oestrogen-receptors (ER) are likely to be promiscuous: wider role for oestrogens and mimics. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65:760–765. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura NH, Rosell DR, Akama KT, McEwen BS. Estrogen and ovariectomy regulate mRNA and protein of glutamic acid decarboxylases and cation-chloride cotransporters in the adult rat hippocampus. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80:308–323. doi: 10.1159/000083657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EJ, Ronnekleiv OK, Bosch MA, Kelly MJ. Estrogen biphasically modifies hypothalamic GABAergic function concomitantly with negative and positive control of luteinizing hormone release. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2085–2093. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-02085.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashion AB, Smith MJ, Wise PM. Glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 (GAD67) gene expression in discrete regions of the rostral preoptic area change during the oestrous cycle and with age. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:711–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya E, Nyberg CL, Mogi K, Terasawa E. A role of gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) and glutamate in control of puberty in female rhesus monkeys: effect of an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide for GAD67 messenger ribonucleic acid and MK801 on luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone release. Endocrinology. 1999;140:705–712. doi: 10.1210/en.140.2.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM, Di-Giorgi-Gerevini V, Dwivedi Y, Grayson DR, Impagnatiello F, Pandey G, Pesold C, Sharma R, Uzunov D, Costa E. Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a postmortem brain study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E, Agis-Balboa RC, Simonini MV, Grayson DR, Costa E, Guidotti A. Reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 promoter remodeling in an epigenetic methionine-induced mouse model of schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12578–12583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505394102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SC, Lee BM. DNA methylation of estrogen receptor alpha gene by phthalates. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2005;68:1995–2003. doi: 10.1080/15287390491008913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opolski A, Mazurkiewicz M, Wietrzyk J, Kleinrok Z, Radzikowski C. The role of GABA-ergic system in human mammary gland pathology and in growth of transplantable murine mammary cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2000;19:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo IH, Russo J. Mammary gland neoplasia in long-term rodent studies. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104:938–967. doi: 10.2307/3433143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho RJ, Campbell MJ. Transcription, genomes, function. Trends Genet. 2000;16:409–415. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]