Abstract

Reports from southern Africa, an area in which human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection is caused almost exclusively by subtype C (HIV-1C), have shown increased rates of anemia in HIV-infected populations compared with similar acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients in the United States, an area predominantly infected with subtype B (HIV-1B). Recent findings by our group demonstrated a direct association between HIV-1 infection and hematopoietic progenitor cell health in Botswana. Therefore, using a single-colony infection assay and quantitative proviral analysis, we examined whether HIV-1C could infect hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) and whether this phenotype was associated with the higher rates of anemia found in southern Africa. The results show that a significant number of HIV-1C, but not HIV-1B, isolates can infect HPCs in vitro (P < .05). In addition, a portion of HIV-1C–positive Africans had infected progenitor cell populations in vivo, which was associated with higher rates of anemia in these patients (P < .05). This represents a difference in cell tropism between 2 geographically separate and distinct HIV-1 subtypes. The association of this hematotropic phenotype with higher rates of anemia should be considered when examining anti-HIV drug treatment regimens in HIV-1C–predominant areas, such as southern Africa.

Introduction

Twenty-six million of the estimated 40 million people infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) worldwide are located in sub-Saharan Africa, with countries such as Botswana, South Africa, and Swaziland shouldering some of the worst HIV epidemics in the world.1 Southern Africa, an area almost exclusively plagued by HIV-1 subtype C (HIV-1C), contains 32% of all people living with HIV in the world.1 The higher anemia rates among HIV-infected individuals in southern Africa, compared with similar patients in the United States, make hematopoiesis and HIV-1C's effect on progenitor cell health an important area of investigation.2–4

Recent findings by our group demonstrated that HIV-1 infection was directly associated with hematopoiesis in HIV-infected patients in Botswana, a country in southern Africa.5 The study found direct positive associations between CD4+ and CD34+ cell levels, and between CD34+/CD4+ dual-positive cell levels and both hemoglobin counts and colony-forming ability, as well as negative correlations between circulating viral levels and all indicators of HIV infection and hematopoietic health tested.5 These results suggested a direct role for HIV-1C in the hematopoietic process that was not due to host population differences. We theorized that these associations, as well as the increased anemia rates seen in southern Africa, were related to an expansion of the cell tropism of HIV-1C to infect hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs).

In the past, the ability of HIV-1 to infect HPCs has been studied exclusively using HIV-1 subtype B (HIV-1B), which is found predominantly in Europe and North America (reviewed in Moses et al).6 Work from multiple groups has demonstrated that HIV-1B rarely if ever infects HPCs, and if it does these infections occur in the later stages of hematopoiesis.6–10

Due to the geographic separation of the subtypes B and C in the HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic, it is impossible to examine these differences in the same population. Therefore, a modified single-colony infection assay was used to demonstrate that these 2 subtypes differ in their ability to infect HPCs in vitro.11 The capacity of HIV-1C to infect HPCs in vivo was also observed. In addition, this hematotropic phenotype was found to associate with the higher rates of anemia seen in HIV-positive southern Africans.

Patients, materials, and methods

All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Botswana and the Harvard School of Public Health.

Virus preparation

All viruses were grown in peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) cultures and normalized for infection according to p24 antigen levels (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The clones used for the analysis were MJ4 (HIV-1C) and HXB2RU3CI (HIV-1B), the latter of which was modified to use CCR5 exclusively by mutating the V3 sequence to reflect the consensus for HIV-1B.12,13 The MHX-13 clone was made by replacing the entire envelope of MJ4 with the concurrent envelope segment of HXB2RU3CI. The resulting clones were screened by restriction digest and verified for accuracy and frameshifts by sequence analysis. The HIV-1C primary isolates used were BW-1841, BW-2031, BW-2036, BW-2041, and BW-5042 obtained from blood donors in Botswana.14,15 HIV-1B isolates were MN (laboratory-adapted strain) and 30165, 92US657, 92US712, 92US714, and 92US727 (primary) isolates (NIH AIDS Research & Reference Reagent Program, Bethesda, MD). All primary isolates were isolated during the asymptomatic stage of infection. All viral isolates were compared for their ability to infect PBMC cultures, and it was found that the HIV-1B isolates consistently infected at lower concentrations and grew to higher titers than the HIV-1C isolates.

Umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells (UCBMCs)

Umbilical cord blood was obtained from full-term newborns in the United States. The blood was separated on a Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient and the UCBMCs were removed and washed. The cells were then used immediately or frozen for later use.

Single-colony infection assay

HPC colony infection assays were performed according to a modified version of the protocol reported by Chelucci et al11 Briefly, umbilical cord blood from United States–based donors was separated on a Ficoll gradient. The mononuclear cells (UCBMCs) were removed, washed, and resuspended in 2 mL IMDM with 20 ng p24 of virus or mock treatment. The cells were incubated for 2.5 hours at 37°C. The cells were then extensively washed to remove residual virus, and plated in complete methylcellulose medium containing 1% methylcellulose, 30% FBS, 1% BSA, 10−4 M 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 ng/mL rh stem cell factor, 10 ng/mL rh granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), 10 ng/mL rh IL-3, and 3 units/mL rh erythropoietin at a concentration of approximately 103 cells/mL (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC). The methylcellulose mixture was plated into 96-well plates at a concentration of 200 cells/mL media and 100 μL media in each well. The plates were then incubated for 14 days. Colony growth and morphology were scored at 14 to 16 days for blast-forming units–erythrocytes (BFU-Es), colony-forming units–granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GMs), and colony-forming units–granulocyte-erythrocyte-megakaryocyte-macrophage (CFU-GEMMs). Wells containing only one colony per well were diluted in PBS and the total genomic DNA from the well was isolated (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). All isolates were tested in multiple donors, and multiple isolates were tested on each donor. Donor UCBMCs were not pooled. As a negative control for contaminating mature lymphocytes, wells that contained no colonies were isolated as blanks.

The ability of viral-infected colonies to produce viral proteins was tested using a standard p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA). Briefly, colonies were isolated directly from the methylcellulose media at day 16 or day 21 with a micropipette and diluted into 200 μL of media. This was then used directly in the p24 ELISA. A colony was considered to be positive if the diluted p24 reading was positive and higher than the minimum levels of the assay (3.5 pg/mL).

In vivo analysis

Viable peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples were obtained from 19 HIV-positive patients from our previous study at the Infectious Disease Care Clinic (IDCC) at Princess Marina Hospital in Gaborone, Botswana.5 All participants provided written informed consent and all study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Botswana and the Harvard School of Public Health. Each patient had one 10-mL tube of blood taken in a heparin tube. The whole blood was used for full blood counts and to obtain CD4 cell counts. PBMCs were isolated from all patients and frozen for later use.

CD34+ cells were isolated from frozen viable PBMC samples from patients using a positive selection magnetic bead cell separation system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The genomic DNA from the CD34+ cells and PBMC fractions was isolated and used in a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay to determine proviral load (Qiagen; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).16 This protocol was altered to accommodate the lower starting genomic DNA levels in these samples by decreasing the elution volume to 150 μL. A patient sample was determined to be positive if the raw viral load was consistently higher than 10 viral copies, and the calculated CD34+ proviral load (proviral copies/10 000 cells) was significantly higher than the PBMC proviral load (P < .05, t test). An extra aliquot of CD34+ cells from participant 13's frozen PBMC samples was isolated using a magnetic bead separation protocol (Invitrogen). The CD34+ cells were washed and mixed with methylcellulose at a concentration of 200 cells/mL and placed in a 96-well plate (Stem Cell Technologies). The plates were incubated for approximately 13 days and the colonies were scored. Single-colony wells were isolated and checked for infection using qPCR.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total genomic DNA of each colony and blank was tested for presence of proviral DNA and a housekeeping gene (β-globin or albumin). All primary isolates, MHX-13, patient 13, and approximately half of the MJ4 and HXB2RU3CI colonies were tested using an proviral analysis adapted for use with the ABI 7500 real-time PCR machine by changing the extension step to 60°C for one minute and removing the touch-down step (Applied Biosystems).16 This assay was verified to accurately predict HIV-1B proviral amounts by testing with 8E5 cellular DNA. The remaining MJ4 and HXB2RU3CI colonies were tested using a FRET hybridization probe setup. Briefly, 5 μL genomic DNA from colonies were mixed with corresponding primers and probes to measure either MJ4 (primers: 5′-ttagtcccgaggtaatacc-3′, 5′-gtggattgtgtgtcatcca-3′; probes: 5′-gcagggcctgttgcac-FITC-3′, 5′-lc640-ggccaaatgagagacccaagg-phosphate-3′) or HXB2RU3CI (primers: 5′-gaccagcggctacactag-3′, 5′-tagcctgtctctcagtaca-3′; probes: 5′-acagcatgtcagggagtagg-FITC-3′, 5′-lc640-gacccggccataaggca-phosphate-3′) gag levels, and primers and probes (primers: 5′-ggtgaacgtggatgaag-3′, 5′-gccaggccatcactaa-3′; probes: 5′-acccttggacccagagg-FITC-3′, 5′-lc705-ctttgagtcctttggggatctg-phosphate-3′) to monitor β-globin levels simultaneously (Roche, Palo Alto, CA). The samples were run at 95°C for 10 minutes, then 45 cycles at 95°C for 10 seconds, 57°C for 7 seconds with a fluorescent reading at the end, and 72°C for 12 seconds. Standards for the hybridization assay were determined by quantifying plasmid viral DNA and mixing with the appropriate level of uninfected host cell genomic DNA. All samples were compared for relative levels of proviral DNA copies to the housekeeping gene numbers. A colony was determined to be positive when the proviral value/housekeeping gene ratio was 0.4:0.6 in 2 separate runs with a raw quantitative proviral value of greater then 50 copies per run. This demonstrates an integrated proviral copy for every cell in the colony, and indicates that the colony was infected at the progenitor stage before the colony formed.

Integration was verified for select colonies using a modified SYBR Green analysis (Applied Biosystems).17 Briefly, the primers reported by Brussel and Sonigo17 were used for the first round for 15 cycles in a standard PCR. One five-hundredth of the first-round samples were used in a 50-μL reaction with 0.5 μM Lambda T, and AA55M-C (5′-gctagagattttccacact-3′) with SYBR Green for 40 cycles (Applied Biosystems).17 8E5 cellular DNA (cell line with one stably integrated HIV-1B provirus per cell) was used as the positive control. This approach was verified for accuracy using the same primers and annealing temperatures in a standard nested PCR setup (Figure 1).

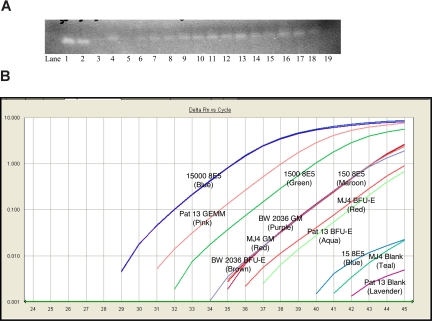

Figure 1.

Verification of HIV-1 infection of HPC-CFUs by Alu-LTR integration. (A) Infected colonies and blank wells were tested for integration using nested PCR.17 The resulting DNA product was approximately 150 bp in length. 8E5 cellular DNA (lanes 1-4: 50 000, 5000, 500, and 50 copies, respectively), a blank MJ4 well as the negative control (lane 5), MJ4-infected BFU-E colonies (lanes 6-8), MJ4-infected CFU-GM colonies (lanes 9-13), the MHX-infected CFU-GM colony (lane 14), BW-2036–infected BFU-E colonies (lanes 15, 16), BW-2036–infected CFU-GM colonies (lanes 17, 18), and H2O (lane 19) are shown. (B) Representative fluorescent curves of SYBR Green integration assay. Standards are indicated as copy number of 8E5 cellular DNA; positive colony types and negative blank wells from MJ4 and patient 13 are also shown with colors indicated in parentheses.

Results

A side-by-side single-colony infection assay using cloned viruses of HIV-1B and HIV-1C (HXB2RU3CI and MJ4, respectively) was performed to determine the ability of HIV-1C to infect HPC–colony-forming units (HPC-CFUs) derived from umbilical cord blood, with mock infection as a negative control (Table 1).12,18 Both of these viruses use CCR5 exclusively as their coreceptor for viral entry. In the past, several groups have used standard PCR analysis to explore HPC infection; however, this carries the risk of false positives due to lymphocyte contamination of the culture.6 Therefore, for this analysis a qPCR assay was used, which has been shown to be a more accurate method to measure HPC infection, to ensure sensitivity and specificity in our detection.18 Stable viral integration of the HIV genome using a modified SYBR Green integration assay was used to verify infection of select colonies (Figure 1).17 These results demonstrated that the HIV-1C clone could infect HPC-CFUs at a significantly higher rate then the HIV-1B clone (Table 1).

Table 1.

Infection rates of HPC-CFUs with cloned and laboratory-adapted HIV isolates

| Colony type | HXB2RU3CI (B) | MJ4 (C) | MHX-13 (B Env) | MN (B) | IIIB (B)19 | Ba-L (B)19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFU-E | 0/53 | 6/45 | 0/55 | 0/51 | 0/125* | 0/36* |

| CFU-GM | 3/112 | 11/92 | 1/36 | 1/37 | 0/88* | 0/56* |

| CFU-GEMM | 0/24 | 4/21 | 0/3 | 0/2 | N/A | N/A |

| Total (%) | 3/189 (1.6) | 21/158† (13.3) | 1/94 (1.1) | 1/90 (1.1) | 0/213* (0.0) | 0/92* (0.0) |

Data are numbers of colonies infected over numbers of single colonies tested. MJ4, HXB2RU3CI, MHX-13, and MN laboratory-adapted colonies were tested by quantitative real-time PCR techniques. Viral subtype is shown in parentheses in column head.

IIIB and Ba-L isolate data are adapted from Molina et al.19 All categories were compared with HXB2RU3CI for statistical significance by Fisher exact test.

P < .001.

Viral p24 analysis was used to confirm that the MJ4-infected colonies could functionally produce viral products. It was found that 1 of 25 BFU-E, 3 of 32 CFU-GM, and 5 of 19 CFU-GEMM colonies tested had positive p24 production. This confirmed that the MJ4-infected colonies could produce viral proteins.

The HIV-1B isolate MN was used to determine whether a laboratory-adapted strain could infect HPC-CFUs in our single-colony infection assay (Table 1). These results were compared with previously published reports, which used a similar approach to examine HIV-1B infection of HPC-CFUs (Table 1).19 In addition, 5 primary isolates of HIV-1B (30165, 92US657, 92US712, 92US714, and 92US727) were tested to examine whether this lack of tropism is found in HIV-1B circulating strains (Figure 2 and Table 2). Using this method, the HIV-1B viruses were unable to infect HPC-CFUs, which was similar to previous findings.6,8,19,20

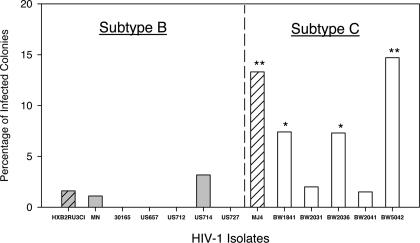

Figure 2.

Efficiency of single-colony infections using primary HIV-1 isolates. Total colonies infected are shown as percentage of colonies tested. All colonies were compared with HXB2RU3CI for significance. Cloned virus isolates are shown (▨). The percentage of HIV-1C isolates that infect progenitor cells differs significantly from the percentage of HIV-1B as determined by Fisher exact test, P < .05.

Table 2.

Efficiency of single-colony infections using primary HIV-1 isolates.

| Colony type | 30165 (B) | 92US657 (B) | 92US712 (B) | 92US714 (B) | 92US727 (B) | BW1841 (C) | BW2031 (C) | BW2036 (C) | BW2041 (C) | BW5042 (C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFU-E | 0/27 | 0/19 | 0/22 | 0/26 | 0/27 | 0/41 | 0/45 | 2/54 | 0/49 | 1/22 |

| CFU-GM | 0/37 | 0/23 | 0/27 | 2/34 | 0/35 | 7/52* | 2/48 | 7/61* | 2/76 | 8/31** |

| CFU-GEMM | 0/1 | 0/2 | N/A | 0/3 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 0/9 | 0/7 | 2/22 |

| Total (%) | 0/65 (0.0) | 0/44 (0.0) | 0/49 (0.0) | 2/63 (3.2) | 0/66 (0.0) | 7/95* (7.4) | 2/98 (2.0) | 9/124* (7.3) | 2/132 (1.5) | 11/75** (14.7) |

Data are numbers of infected colonies over numbers of single colonies tested. Primary isolate colonies were tested using hydrolysis probe technique.16 Viral subtype is shown in parentheses in column heads. All categories were compared with HXB2RU3CI for statistical significance by Fisher exact test.

P < .05,

P < .001.

To determine the breadth of the hematotropic phenotype, multiple HIV-1C primary viral isolates from southern Africa were examined using this assay (Figure 2 and Table 2). Three of 5 HIV-1C isolates (1841, 2036, and 5042) examined were found to infect at a significantly higher rate than HXB2RU3CI. These data demonstrate a significant difference in the ability of HIV-1B (0 of 7 tested) and HIV-1C (4 of 6 tested) isolates to infect HPC-CFUs (P < .05, Fisher exact test) (Figure 2A). However, these data also revealed that the hematotropic phenotype is not universally found in all HIV-1C isolates from southern Africa. The effects of the different viral isolates on total colony-forming ability were examined. No consistent difference in number of colonies formed was found among the viral isolates tested.

Previous groups have shown that viral entry is the controlling factor in the blocking of HIV-1B infection of HPCs.21,22 To verify the hypothesis that the viral envelope is necessary for the ability of the virus to infect HPCs, the MHX-13 clone was constructed to test for a loss of ability to infect HPC-CFUs. MHX-13 is a viral chimera that has the envelope of HXB2RU3CI in place of the MJ4 envelope. The virus was compared with both parental strains (MJ4 and HXB2RU3CI) and found to differ significantly from the HIV-1C parental clone but not the HIV-1B clone in its ability to infect HPC-CFUs (Table 1). This demonstrates that the ability to infect HPC-CFUs is reliant on the viral envelope, and verifies that the inability of HIV-1B to infect HPC-CFUs is at least partially due to a block in viral entry.21,22

Due to the ability of HIV-1C to infect HPC-CFUs in vitro and our previous findings from Botswana that demonstrated a direct connection between HIV-1 infection and hematopoiesis, the possibility that HIV-1C was infecting HPCs in vivo was examined.5 PBMC samples from 19 HIV-1C–infected patients in Gaborone, Botswana, were obtained from participants of our previous study (Table 3).5 All the patients recruited were identified as AIDS patients according to UNAIDS diagnostic criteria, and were enrolled in the study prior to beginning antiretroviral treatment. CD4+ cell levels, full blood counts, and PBMC samples were obtained from all patients. CD34+ progenitor populations from the frozen PBMC samples were purified via magnetic bead separation and tested for infection using a qPCR proviral load analysis.16 It was determined that 12 of 19 patients had detectable provirus in their CD34+ HPCs. Of particular interest, 11 of the 12 with detectable CD34+ HPCs had significantly higher levels of provirus in HPCs than in PBMCs, indicating that the result could not be due to contamination (Table 2). This suggests that at least a portion of AIDS patients in Botswana likely has infected HPC populations. In addition, when the 19 patients were separated according to the presence of anemia (HGB ≤ 10 g/dL), there was a significantly higher number of patients in the anemia group with infected CD34+ progenitor cell populations (P < .05, Fisher exact test) (Table 3). There was no evidence that the hematotropic phenotype was associated with other hematotropic abnormalities such as neutropenia or thrombocytopenia. In addition, the CD34+ proviral load did not correlate with viral load, CD4 count, or any of the progenitor cell markers tested. Taken with the higher rates of anemia found in southern Africa and our previous results, these data suggest that the hematotropic ability found in HIV-1C could be having an effect on the hematopoietic health of this population.2–5

Table 3.

Analysis of data from 19 HIV+ patients used for PBMC and CD34+ cell proviral analysis

| Patient no. | CD4, count/μL | Sex | HGB, g/dL | PBMC proviral, per 104 cells | CD34+ proviral, per 104 cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 153 | F | 11.7 | 34.8 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 94 | F | 13.9 | 7.3 | 0.0 |

| 3*† | 50 | M | 9.8 | 17.32 | 1262 |

| 4* | 104 | M | 15.6 | 77.0 | 5300 |

| 5* | 94 | M | 11.3 | 106 | 1034 |

| 6*† | 13 | F | 9.8 | 3.74 | 3800 |

| 7 | 44 | F | 11 | 78.0 | 0.0 |

| 8 | 226 | F | 11.9 | 47.6 | 145.4 |

| 9†‡ | 90 | F | 9.1 | 45 | 195.8 |

| 10 | 124 | M | 14.5 | 68.4 | 0.0 |

| 11 | 75 | F | 11.7 | 5.14 | 0.0 |

| 12 | 143 | M | 14.4 | 38.6 | 0.0 |

| 13*† | 113 | M | 7.7 | 36.8 | 354 |

| 14† | 10 | F | 9.6 | 146.6 | 0.0 |

| 15†‡ | 5 | M | 9 | 38.6 | 238 |

| 16* | 53 | M | 15.6 | 116.2 | 742 |

| 17*† | 54 | F | 10 | 66.8 | 2080 |

| 18*† | 71 | F | 8.3 | 101.2 | 4500 |

| 19*† | 186 | F | 4.8 | 142 | 2200 |

Samples were collected from HIV-positive patients beginning the national HAART regimen at the Infectious Disease Care Clinic in Gaborone, Botswana. All patients were antiretroviral drug–naive. CD34+ cells were isolated using a magnetic bead positive selection (Invitrogen). Patients with a CD34+ cell proviral load that was significantly higher than their respective PBMC proviral load are indicated *(t test, P < .005, ‡P < .05). Eight of 9 anemic patients (nos. 3, 6, 9, 13, 15, and 17-19) had positive CD34+ cell populations, a significantly higher portion than the 3 of 10 nonanemic patients (nos. 4, 5, and 16; Fisher exact test, P < .05).

Patients who had anemia (HGB ≤ 10 g/dL).

The CD34+ progenitor cells found in circulation represent a diverse group of HPCs, which includes the HPC-CFU population. Therefore, to determine whether the ability to infect HPC-CFUs was restricted to an in vitro setting or could be seen in vivo as well, an extra PBMC aliquot from a severely anemic AIDS patient from Botswana, patient 13, was examined in a single-colony growth assay. Previously, it had been found that patient 13's CD34+ cell proviral load was 354 proviral copies per 104 cells for an approximate infection rate of 3.5% (Table 3). The CD34+ cells from the remaining sample were purified and plated in a single-colony assay. Using qPCR, we tested the HPC colonies for presence of infection. It was found that 2 of 67 BFU-E, 0 of 22 CFU-GM, and 1 of 6 CFU-GEMM colonies were positive for infection. This demonstrates that the infected CD34+ cells were able to form colonies, and indicates that the hematotropic phenotype seen in the in vitro infection assays is similar to the one seen in vivo.

Discussion

The ability of HIV-1B to infect HPCs has been explored using multiple in vitro and in vivo systems.6,8,19,20,23 It is widely believed that although a portion of CD34+ HPCs contain CD4 and the coreceptors needed for infection, CCR5 and CXCR4, there remains an intrinsic block in viral entry.21,22 This block is rarely overcome naturally in HIV-1B infections, and infections occur only in late-stage progenitor cells.7,24 Although it is true that several groups have reported possible infections of HPCs by HIV-1B, these studies were beset with problems that could have led to the identification of false positives either from incomplete purification of the HPC population or by using standard PCR to identify infected colonies.6 The use of qPCR to examine infected colonies and the isolation of blank wells as a negative control eliminates this risk by providing an accurate way to compare colony cell number with integrated proviral levels in the same colony, and to compare that ratio to known background levels from the blank wells.

It has also been shown that HIV-1B can infect the stromal cell layer in the bone marrow.6,25–27 This infection causes a lowering of beneficial hematopoietic growth factors, and raises the levels of TNF-α, which was shown to adversely affect hematopoiesis.25,26,28 This disruption in the bone marrow microenvironment causes a loss of colony-forming cell growth, and disrupts proper hematopoietic lineage differentiation.25,29,30 Work by multiple groups has shown that hematopoietic function can be at least partially restored with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).31–37

The findings described here indicate that HIV-1C can infect HPC-CFUs and CD34+ HPCs in vitro and in vivo, and that this infection is associated with higher anemia rates in infected patients. Taken with our previous results, this indicates that the effect of HIV-1C infection on hematopoiesis could have serious public health ramifications. One problem with comparing HIV clinical and epidemiologic reports from the United States and Africa is the differential endemic disease load, and in particular the potential influence of parasitic gut disorders and malaria in many African nations.38 However, Gaborone, Botswana, does not have endemic malaria and has full access to clean drinking water, limiting the effect that parasitic infections would have on these results.39 In addition, a previous study by our group in Botswana found that only 11.7% of anemia cases in the HIV-positive population are associated with iron deficiencies, and all of the patients examined here are erythropoietin naive.40 It should be noted that all the HIV-1C isolates and clones used were from southern Africa exclusively, and it would be interesting to see whether this hematotropic phenotype is found in other areas where HIV-1C is predominant, such as India where a case of HIV-induced pediatric aplastic anemia was recently reported.41 It cannot be determined from these data whether the hematotropic phenotype is unique to subtype C in southern Africa, or is also found in other HIV variants in different geographic locations. For example, Stanley et al reported that 36.5% of patients in Zaire had infected CD34+ cells compared with only 14% of similar American patients.42 However, this report used standard PCR as a detection method, and it is possible that the viral infections seen are due to contamination from mature cells. It is possible that some isolates of HIV-1B or other subtypes could posses this phenotype and have yet to be tested. However, due to the amount of previous work on HIV-1B, and the significant differences between HIV-1C and HIV-1B isolates described here, it is likely that hematotropic isolates would be rare in HIV-1B in the United States or Europe.

These results suggest that HIV-1C's effects on hematopoiesis are at least partially caused by viral infection of the HPC population. The HPC population could serve as an ideal cellular reservoir for the virus because the cells are long-lived and constantly expanding as they develop into mature cells. Therefore, if a virus evolved the ability to infect the HPC population, it would have a significant advantage over other viral isolates in the same host. One question not answered by this work is when during the course of the disease does the hematotropic phenotype emerge, or is this phenotype transmitted from host to host? It should be possible to examine this question as well as to elucidate the exact effect this phenotype has on hematopoiesis, in a longitudinal study of HIV-1C–positive patients begun in the early stages of infection.

A longitudinal examination could also help to elucidate what effect infections of different myelopoietic lineages' progenitor cells have on their respective progeny cell levels. It is interesting to speculate that the increased rates of anemia seen in this study are due to the ability of HIV-1C to infect the BFU-E cells. We speculate that although the ability to infect CFU-GM colonies may be playing a role in the higher anemia rates, it is probably having a greater effect on the rates of neutropenia, which also seem to be higher in the HIV-positive southern African population.4,43 In addition, although the absolute numbers of HIV-1C–infected CFU-GEMM colonies are small, the percentage is the highest of the 3 colony types tested. Because CFU-GEMMs represent the earliest myelopoietic progenitor population, the ability to infect and possibly directly kill these cells could theoretically have the most potent effect on the system as a whole. However, it is impossible to determine whether this is the case with any certainty due to the cross-sectional nature of our study.

One of the interesting findings described here was the infection of CFU-GEMM colonies, which represent the earliest myelopoietic progenitor cells, by HIV-1C in vitro and in vivo. Taken with the verification that the viral envelope is necessary for the hematotropic phenotype, it is interesting to speculate that HIV-1C might be able to infect resting hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), which was shown not to occur with HIV-1B due to a block in entry.22,44 In addition, recent work by Zhang et al demonstrated that the inability of HIV-1B to infect HSCs might be more complicated due to a block in viral integration by the cellular protein p21.44 However, infected colonies discussed here were shown to fully integrate, suggesting that HIV-1C can at least partially overcome this block as well as other possible blocks in postentry steps (Figure 1).44 A more detailed analysis of the hematotropic isolates' ability to infect HSCs should clarify these questions.

With the increasing availability of antiretroviral treatment in the developing world, the hematotropic phenotype described here could have significant impact on treatment options in areas in which HIV-1C predominates, such as southern Africa. Work from multiple groups has shown that HAART can benefit hematopoiesis by reducing fas-mediated apoptosis of HPCs in HIV-infected patients.33,34 However, some antiretroviral nucleoside analog drugs, such as zidovudine, can cause anemia as a side effect to treatment.45 Conversely, protease inhibitors have been shown to stimulate hematopoiesis in treated patients.37 In planning drug treatment options for use in developing countries with HIV-1C epidemics, it may be important to factor in the issue of increased susceptibility to anemia. It might also be prudent to expand treatment options in these areas to combat this problem with increased use of prohematopoietic drugs such as erythropoietin or mineral supplements. It would be interesting to explore whether these options could help alleviate the extra burden that HIV-1C places on the hematopoietic system in areas such as southern Africa.

In conclusion, this work identifies an expansion of the cell tropism of HIV-1C to infect HPCs that is distinctly different from HIV-1B. This hematotropism was also found to be associated with higher rates of anemia in southern Africa. This indicates that hematotropic viral isolates are a serious public health concern that will need to be addressed to maximize the efficacy of current and future HIV/AIDS treatment options in areas with predominant HIV-1C epidemics such as southern and eastern Africa, India, and China.

Acknowledgments

A.A. received support from the National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center grant D43 TW000004.

We are grateful to all the study participants, the IDCC medical staff for their tireless work, and specifically Mpho Zwinila for all her assistance; we also thank the staff of the Botswana-Harvard School of Public Health Partnership Research Laboratory, Molly Pretorius-Holme, Lendsey Melton, and Kelesitse Phiri for helpful discussions and assistance, and Dr Michael Greene of Massachusetts General Hospital's Department of Fetal Maternal Medicine for umbilical cord blood samples.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: A.D.R. designed research, carried out recruitment, performed research, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; A.A. carried out recruitment and enrollment of patients, and was responsible for clinical management of the patients; and M.E. designed research, directed the study, and contributed to writing the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: M. Essex, Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard School of Public Health, FXB 402, 651 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: messex@hsph.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. 2006 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. p. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ssali F, Stöhr W, Munderi P, et al. Prevalence, incidence and predictors of severe anaemia with zidovudine-containing regimens in African adults with HIV infection within the DART trial. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:741–749. doi: 10.1177/135965350601100612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan PS, Hanson DL, Chu SY, Jones JL, Ward JW. Epidemiology of anemia in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons: results from the multistate adult and adolescent spectrum of HIV disease surveillance project. Blood. 1998;91:301–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adewuyi JO, Coutts AM, Latif AS, Smith H, Abayomi AE, Moyo AA. Haematologic features of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in adult Zimbabweans. Cent Afr J Med. 1999;45:26–30. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v45i2.8447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redd AD, Avalos A, Phiri K, Essex M. Effects of HIV-1 subtype C infection on hematopoiesis in Botswana. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:996–1003. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moses A, Nelson J, Bagby GC., Jr The influence of human immunodeficiency virus-1 on hematopoiesis. Blood. 1998;91:1479–1495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bannert N, Farzan M, Friend DS, et al. Human mast cell progenitors can be infected by macrophagetropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and retain virus with maturation in vitro. J Virol. 2001;75:10808–10814. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10808-10814.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis BR, Schwartz DH, Marx JC, et al. Absent or rare human immunodeficiency virus infection of bone marrow stem/progenitor cells in vivo. J Virol. 1991;65:1985–1990. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1985-1990.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine AM, Scadden DT, Zaia JA, Krishnan A. Hematologic aspects of HIV/AIDS. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2001:463–478. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2001.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louache F, Bettaieb A, Henri A, et al. Infection of megakaryocytes by human immunodeficiency virus in seropositive patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 1991;78:1697–1705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chelucci C, Hassan HJ, Locardi C, et al. In vitro human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection of purified hematopoietic progenitors in single-cell culture. Blood. 1995;85:1181–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ndung'u T, Renjifo B, Essex M. Construction and analysis of an infectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C molecular clone. J Virol. 2001;75:4964–4972. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.4964-4972.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trujillo JR, Wang WK, Lee TH, Essex M. Identification of the envelope V3 loop as a determinant of a CD4-negative neuronal cell tropism for HIV-1. Virology. 1996;217:613–617. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novitsky V, Cao H, Rybak N, et al. Magnitude and frequency of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses: identification of immunodominant regions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C. J Virol. 2002;76:10155–10168. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10155-10168.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novitsky V, Smith UR, Gilbert P, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C molecular phylogeny: consensus sequence for an AIDS vaccine design? J Virol. 2002;76:5435–5451. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5435-5451.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novitsky VA, Gilbert PB, Shea K, et al. Interactive association of proviral load and IFN-gamma-secreting T cell responses in HIV-1C infection. Virology. 2006;349:142–155. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brussel A, Sonigo P. Analysis of early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA synthesis by use of a new sensitive assay for quantifying integrated provirus. J Virol. 2003;77:10119–10124. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.10119-10124.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koka PS, Fraser JK, Bryson Y, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus inhibits multilineage hematopoiesis in vivo. J Virol. 1998;72:5121–5127. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5121-5127.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molina JM, Scadden DT, Sakaguchi M, Fuller B, Woon A, Groopman JE. Lack of evidence for infection of or effect on growth of hematopoietic progenitor cells after in vivo or in vitro exposure to human immunodeficiency virus. Blood. 1990;76:2476–2482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weichold FF, Zella D, Barabitskaja O, et al. Neither human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) nor HIV-2 infects most-primitive human hematopoietic stem cells as assessed in long-term bone marrow cultures. Blood. 1998;91:907–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Mukai T, Young D, Frankel S, Law P, Wong-Staal F. Transduction of CD34+ cells by a vesicular stomach virus protein G (VSV-G) pseudotyped HIV-1 vector: stable gene expression in progeny cells, including dendritic cells. J Hum Virol. 1998;1:346–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen H, Cheng T, Preffer FI, et al. Intrinsic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance of hematopoietic stem cells despite coreceptor expression. J Virol. 1999;73:728–737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.728-737.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koka PS, Jamieson BD, Brooks DG, Zack JA. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-induced hematopoietic inhibition is independent of productive infection of progenitor cells in vivo. J Virol. 1999;73:9089–9097. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9089-9097.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwan WH, Helt AM, Maranon C, et al. Dendritic cell precursors are permissive to dengue virus and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:7291–7299. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7291-7299.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maciejewski JP, Weichold FF, Young NS. HIV-1 suppression of hematopoiesis in vitro mediated by envelope glycoprotein and TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 1994;153:4303–4310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moses AV, Williams S, Heneveld ML, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of bone marrow endothelium reduces induction of stromal hematopoietic growth factors. Blood. 1996;87:919–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scadden DT, Zeira M, Woon A, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human bone marrow stromal fibroblasts. Blood. 1990;76:317–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broxmeyer HE, Williams DE, Lu L, et al. The suppressive influences of human tumor necrosis factors on bone marrow hematopoietic progenitor cells from normal donors and patients with leukemia: synergism of tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma. J Immunol. 1986;136:4487–4495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bahner I, Kearns K, Coutinho S, Leonard EH, Kohn DB. Infection of human marrow stroma by human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) is both required and sufficient for HIV-1-induced hematopoietic suppression in vitro: demonstration by gene modification of primary human stroma. Blood. 1997;90:1787–1798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibellini D, Vitone F, Buzzi M, et al. HIV-1 negatively affects the survival/maturation of cord blood CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells differentiated towards megakaryocytic lineage by HIV-1 gp120/CD4 membrane interaction. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:315–324. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams GB, Pym AS, Poznansky MC, McClure MO, Weber JN. The in vivo effects of combination antiretroviral drug therapy on peripheral blood CD34+ cell colony-forming units from HIV type 1-infected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15:551–559. doi: 10.1089/088922299311079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baillou C, Simon A, Leclercq V, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy corrects hematopoiesis in HIV-1 infected patients: interest for peripheral blood stem cell-based gene therapy. AIDS. 2003;17:563–574. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang SS, Barbour JD, Deeks SG, et al. Reversal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-associated hematosuppression by effective antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:504–510. doi: 10.1086/313714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Isgro A, Aiuti A, Mezzaroma I, et al. Improvement of interleukin 2 production, clonogenic capability and restoration of stromal cell function in human immunodeficiency virus-type-1 patients after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:864–874. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isgro A, Mezzaroma I, Aiuti A, et al. Decreased apoptosis of bone marrow progenitor cells in HIV-1-infected patients during highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2004;18:1335–1337. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406180-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarcletti M, Quirchmair G, Weiss G, Fuchs D, Zangerle R. Increase of haemoglobin levels by anti-retroviral therapy is associated with a decrease in immune activation. Eur J Haematol. 2003;70:17–25. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.02810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sloand EM, Maciejewski J, Kumar P, Kim S, Chaudhuri A, Young N. Protease inhibitors stimulate hematopoiesis and decrease apoptosis and ICE expression in CD34(+) cells. Blood. 2000;96:2735–2739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitworth J, Morgan D, Quigley M, et al. Effect of HIV-1 and increasing immunosuppression on malaria parasitaemia and clinical episodes in adults in rural Uganda: a cohort study. Lancet. 2000;356:1051–1056. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michaelsen KF. Hookworm infection in Kweneng District, Botswana: a prevalence survey and a controlled treatment trial. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1985;79:848–851. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sales S, Campa A, Essex M, et al. Anemia in Early Stages of HIV-1 Infection in adults in Botswana, Africa.. Oral abstract session AIDS 2006—XUI International AIDS Conference: Abstract no. THAc0205. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah I, Murthy AK. Aplastic anemia in an HIV infected child. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:359–361. doi: 10.1007/BF02724022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanley SK, Kessler SW, Justement JS, et al. CD34+ bone marrow cells are infected with HIV in a subset of seropositive individuals. J Immunol. 1992;149:689–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy MF, Metcalfe P, Waters AH, et al. Incidence and mechanism of neutropenia and thrombocytopenia in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Haematol. 1987;66:337–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb06920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang J, Scadden DT, Crumpacker CS. Primitive hematopoietic cells resist HIV-1 infection via p21. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:473–481. doi: 10.1172/JCI28971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carr A, Cooper DA. Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2000;356:1423–1430. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02854-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]