Abstract

Oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL) is a key factor in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and its thrombotic complications, such as stroke and myocardial infarction. It activates endothelial cells and platelets through mechanisms that are largely unknown. Here, we show that lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) was formed during mild oxidation of LDL and was the active compound in mildly oxidized LDL and minimally modified LDL, initiating platelet activation and stimulating endothelial cell stress-fiber and gap formation. Antagonists of the LPA receptor prevented platelet and endothelial cell activation by mildly oxidized LDL. We also found that LPA accumulated in and was the primary platelet-activating lipid of atherosclerotic plaques. Notably, the amount of LPA within the human carotid atherosclerotic lesion was highest in the lipid-rich core, the region most thrombogenic and most prone to rupture. Given the potent biological activity of LPA on platelets and on cells of the vessel wall, our study identifies LPA as an atherothrombogenic molecule and suggests a possible strategy to prevent and treat atherosclerosis and cardiocerebrovascular diseases.

Dysfunction of the endothelium is a hallmark of the early atherosclerotic lesion, and oxidatively modified low density lipoprotein (LDL) activates endothelial cells, leading to an alteration of the functional and structural integrity of the endothelial barrier (1–3). Oxidized LDL causes an increased permeability of the endothelium (4), and mildly oxidized LDL (mox-LDL) or minimally modified LDL (mm-LDL) stimulates the expression of adhesion molecules on the endothelial surface, allowing monocytes to attach and, subsequently, to transmigrate into the subendothelial space (3, 5). Progression of atherosclerosis is characterized by further lipid accumulation, platelet attachment to lesion-prone sites with retracted endothelial cells, and subsequent mural thrombus formation. Interestingly, experimental evidence indicates that the lipid-rich atheromatous core and not the exposed collagen is thrombogenic (6). Lipid-rich plaques are vulnerable and, on rupture, might expose thrombogenic LDL particles that activate circulating platelets, causing them to aggregate and form an intravascular plug that eventually leads to stroke and myocardial infarction (7). Indeed, previous studies indicate that oxidatively modified LDL stimulates platelets, mox-LDL being more active than heavily oxidized LDL (8, 9).

The mechanisms by which oxidized LDL activates platelets and endothelial cells are poorly understood. Although heavily oxidized LDL often has toxic effects on cells, mm-LDL and mox-LDL seem to alter the function of cells through a mechanism that involves the stimulation of receptor-mediated signal transduction pathways (1–3, 9). The biologically active components of mm-LDL, mox-LDL, and their receptors on the cell surface are largely unknown. One of the active principles of mm-LDL has been attributed to certain oxidized phosphatidylcholine molecules that have platelet-activating factor (PAF)-like activity and induce monocyte–endothelial interactions after long-term treatment of endothelial cells (3, 5). Other biologically active lipids found in oxidized LDL are lysophosphatidylcholine, F2–isoprostanes, and 4-hydroxy-2,3-trans-nonenal (see refs. 2, 9, 10, and references therein). Because our group has previously excluded these substances as the active components responsible for platelet activation by mox-LDL (ref. 9; unpublished data), we designed the present study to identify the components in mox-LDL that induce platelet activation and to investigate whether these components also activate human endothelial cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of Native LDL (nat-LDL), mox-LDL, and mm-LDL.

LDL was isolated in the continuous presence of EDTA as described (11). LDL was dialyzed at 4°C by using a N2-saturated buffer (9) containing EDTA (1 mM) and then stored at 4°C in darkness under N2. mox-LDL was prepared from EDTA-free LDL by Cu2+-triggered oxidation as described (9). mm-LDL was obtained by spontaneous oxidation of nat-LDL, either in the presence of EDTA during prolonged storage at 4°C for 2–4 months (5) or after removal of EDTA by incubation at 37°C for 1–2 days under gentle agitation.

Surgical Specimens of Normal and Atherosclerotic Human Arteries.

Atherosclerotic tissue specimens were obtained from 10 patients who underwent operations for high-grade carotid stenosis, from 1 patient for stenosis of the femoral artery, and 1 patient for dissection of an aortic aneurysm. Normal arterial tissue (carotid, renal, and hepatic arteries) was obtained from one patient who underwent an operation for a tumor of the glomus caroticum or from patients undergoing abdominal surgery or kidney transplantation. The informed consent of the patients as well as the approval of the protocol by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine were obtained. Intraoperatively, the carotid plaque tissue was removed by a careful operative endarterectomy, which preserved the en bloc plaque structure (12). The samples were dissected longitudinally in the bifurcation level to obtain two homologous halves, one used for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) determination and the other used for histological analysis. Some of the samples were further cut horizontally into four intimal regions: distal region, shoulder region, core region, and proximal region (12). For LPA analysis, the specimens were washed in PBS containing EDTA (1 mM), weighed, frozen with liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80°C until lipid extraction.

Measurement of Platelet Shape Change.

Shape change of human platelets treated with acetylsalicylate was measured as described (13). To determine desensitization, the activated sample was incubated further at 37°C in the presence or absence of stirring and then exposed to the second agonist. Platelet shape change was also examined after fixation of the samples with glutaraldehyde by phase–contrast microscopy.

Determination of LPA in nat-LDL, mox-LDL, mm-LDL, Atherosclerotic, and Normal Arterial Tissue.

For LPA analysis of atherosclerotic and normal arterial tissue, the frozen specimens weighing from 10 mg to 70 mg were cut into small pieces, and homogenized in ice-cold N2-saturated buffer containing NaCl (150 mM) and EDTA (10 mM) with a glass pestle and potter. nat-LDL and mox-LDL were adjusted to identical concentrations of protein (ranging from 0.5 mg/ml to 3 mg/ml) and EDTA (10 mM). Samples were spiked with [oleoyl-9,10-3H]LPA (NEN; specific activity = 30–60 Ci/mmol) for recovery determinations. LPA was extracted by a two-step procedure (14). First, by using a modified method of Bligh and Dyer (ref. 14 and refs. therein), neutral lipids and the bulk of phospholipids were extracted into the lower chloroform/methanol phase containing 0.01% butylated hydroxytoluene as antioxidant. Second, the remaining upper water/methanol phase and interface that contained 90–95% of [3H]LPA were acidified to pH 4.5 and extracted with 1-butanol (14–16). The extract was separated by two one-dimensional TLC systems alternatively (15–17). In some experiments, biologically active LPA was purified further by two-dimensional TLC (18, 19). LPA was localized by cochromatography with authentic 1-oleoyl LPA, which was visualized by iodine vapor, and by radioactivity of [3H]LPA, which was detected with an automatic TLC linear analyzer (EG & G Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany). The respective silica gel areas were scraped off the TLC plate, and LPA was eluted with butanol, dissolved in ethanol/Hepes buffer (9:1, vol/vol; pH 7.4), and applied to platelet suspensions for measurement of shape change. Endogenous LPA was quantified against a standard curve of 1-palmitoyl LPA. Measurements were done in triplicate and performed at least twice by using platelets from different donors.

In some experiments, lipids of the lower chloroform/methanol phase were separated by two-dimensional TLC. Lipids were localized by exposure to iodine vapor, eluted, and applied to platelet suspensions for measurement of shape change or used for phosphorus determination according to the method described by Bartlett (20).

Endothelial Cells.

Staining of F-actin and fluorescence microscopy of cultured human umbilical venous endothelial cells were performed as described (21).

RESULTS

mox-LDL Stimulates Platelets Through Activation of the LPA-Receptor(s).

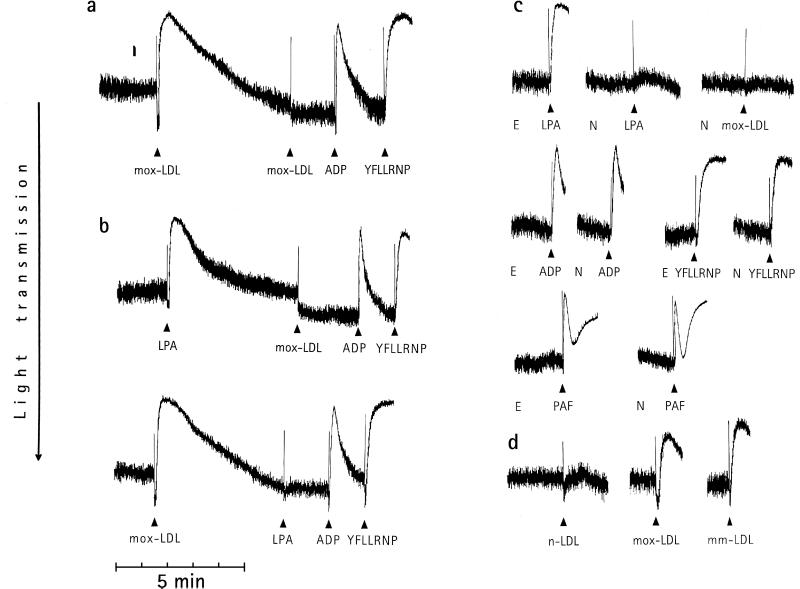

Previously, we established a method of preparing mox-LDL, which might resemble the LDL formed during the early steps of in vivo oxidation of LDL (3, 5, 9). To assay for direct and rapid effects of mox-LDL on platelets, we measured the initial platelet response, i.e., shape change. Amplification mechanisms and positive feedback loops mediated by ADP and thromboxane A2 leading to platelet aggregation and secretion were blocked (22). We observed that shape change induced by mox-LDL was reversible and could not be induced by a subsequent addition of mox-LDL (Fig. 1a). We reasoned that mox-LDL (or a substance therein) might activate a G protein-coupled receptor, because this type of receptor shows a rapid homologous desensitization in platelets (22). Consequently, we used the desensitization response as an assay system to search for molecules mediating the effect of mox-LDL. Of several compounds tested, we found that stimulation of platelets with LPA showed a rapid homologous desensitization of the shape change response and that only LPA desensitized the shape change response to mox-LDL; shape change induced by ADP or the thrombin receptor-activating peptide YFLLRNP (Fig. 1b) was not affected. Also—vice versa—when platelet shape change was induced by mox-LDL, platelets were desensitized to subsequent stimulation by LPA but not to ADP or YFLLRNP (Fig. 1b). NPTyrPA and N-palmitoyl serine phosphoric acid (NPSerPA) are LPA-receptor antagonists that specifically inhibit the action of LPA on platelets and other cells (17, 23, 24). Preincubation of platelets with NPTyrPA completely prevented shape change induced by mox-LDL or LPA but not by ADP, YFLLRNP, or PAF (Fig. 1c). NPSerPA had the same effects as NPTyrPA (data not shown). These results indicate that mox-LDL stimulates platelets through activation of the LPA-receptor(s). It is unclear at present whether the platelet LPA receptor(s) belong(s) to the three putative seven-transmembrane-domain receptors for LPA that have been cloned recently (25–27).

Figure 1.

Platelet shape change induced by mox-LDL is mediated by activation of the LPA receptor. The decrease of light transmission and the disappearance of oscillations are indicative of shape change (13). (a) Homologous desensitization of shape change to mox-LDL (0.2 mg/ml). Subsequent addition of ADP (2 μM) and the peptide YFLLRNP (300 μM), a partial thrombin-receptor agonist (13), still induces shape change. (b) LPA (0.5 μM) desensitizes platelets to subsequent stimulation by mox-LDL (0.2 mg/ml) and vice versa. (c) Platelets were preincubated for 5 min with 0.1% ethanol (E) or 10 μM the specific LPA-receptor antagonist N-palmitoyl tyrosine phosphoric acid (NPTyrPA) dissolved in ethanol (N) before stimulation with LPA, mox-LDL, ADP, YFLLRNP, or PAF (100 nM). (d) Comparison of shape change induced by nat-LDL (n-LDL), mox-LDL, and mm-LDL (0.2 mg/ml each). Tracings shown are representative of 15–20 experiments that gave similar results.

LPA Is Formed by Mild Oxidation of LDL.

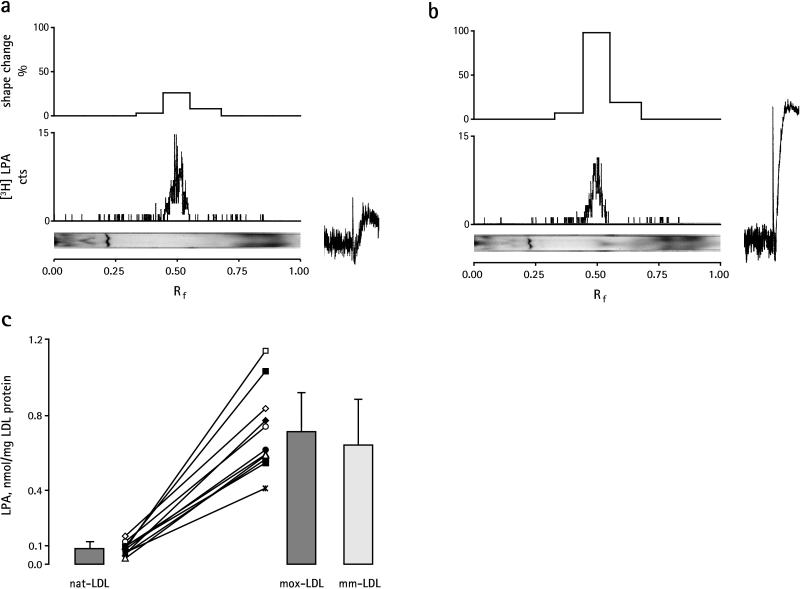

In contrast to mox-LDL, nat-LDL induced only a weak platelet response (Fig. 1d). Therefore, we considered the possibility that LPA is formed during mild oxidation of LDL. nat-LDL and mox-LDL were extracted by a two-step procedure: first, the bulk of neutral lipids and phospholipids was extracted into chloroform/methanol, and, subsequently, the remaining aqueous phase and interface that contained LPA were extracted with butanol. In contrast to the butanol extract, phospholipids and neutral lipids of the lower chloroform/methanol phase did not show any significant biological activity (data not shown). The butanol extract therefore was separated further by TLC and analyzed for biological activity (Fig. 2 a and b). Only one major peak of biological activity comigrating with [3H]LPA was found in nat-LDL and mox-LDL. The biological activity also comigrated with [3H]LPA after subsequent separation on two-dimensional TLC, which separates other lipid phosphoric acids, such as 1-alkenyl LPA, sphingosine 1-phosphate, and cyclic phosphatidic acid, from 1-acyl LPA (refs. 18 and 19 and data not shown). As expected, shape change induced by the LPA extract of nat-LDL and mox-LDL was inhibited by the LPA-receptor antagonists NPTyrPA and NPSerPA (data not shown). Apparently, mild oxidation of nat-LDL increased the content of biologically active LPA (compare shape change tracings in Fig. 2 a and b). LPA therefore was quantified in 11 different LDL preparations before and after mild oxidation by measurement of its biological activity. The mean level of LPA increased 8-fold in mox-LDL (Fig. 2c). We also observed that mm-LDL (obtained by spontaneous oxidation) induced shape change (Fig. 1d) through activation of the LPA receptor (data not shown) and contained an elevated amount of biologically active LPA similar to mox-LDL (Fig. 2c). Both mox-LDL and mm-LDL show a low degree of lipid peroxidation and no change of apolipoprotein B (3, 5, 9). These results indicate that mild oxidation of LDL (independently of the oxidation method used) produces biologically active LPA and establish a nonenzymatic pathway for the formation of LPA.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the butanolic extract of nat-LDL (a) and mox-LDL (b). Extracts were separated by TLC (15, 16), visualized by exposure to iodine vapor (Bottom), and scanned for radioactivity of [3H]LPA added as tracer to nat-LDL and mox-LDL before extraction (Middle). Areas of silica gel of equal length from the origin to the top of the TLC plate were scraped off, eluted, and assayed for shape change (Top). Shape change tracings of LPA eluates from nat-LDL and mox-LDL are shown to the right of a and b. The experiment is representative of three others. (c) Biologically active LPA increases in mox-LDL and mm-LDL. LPA from nat-LDL, mox-LDL, and mm-LDL was extracted and separated by TLC, and shape change was quantified against a standard curve of 1-palmitoyl LPA. Values are mean ± SD from 11 individual LDL preparations (represented by different symbols) before (nat-LDL) and after (mox-LDL) mild oxidation and from 8 preparations of LDL after spontaneous oxidation (mm-LDL).

Lipids from nat-LDL and mox-LDL were also fractionated to explore whether other platelet-activating substances might be formed during mild oxidation of LDL. Lipids of the chloroform/methanol extract were separated by two-dimensional TLC (Table 1). Apart from a small increase of biological activity in the lysophosphatidylcholine fraction of mox-LDL, we could not detect any other lipid with significant platelet activity in mox-LDL (Table 1). Further experiments were directed to find out whether the increase of biological active LPA in mox-LDL was sufficient to mediate its biological effect. As can be seen from the data in Table 2, spiking of nat-LDL with the respective LPA extract of mox-LDL produced LDL-particles with a biological activity similar to that of mox-LDL. Collectively, the data show that LPA is the main platelet-activating lipid in mox-LDL.

Table 1.

LPA is the main platelet shape change-inducing lipid in mox-LDL and atherosclerotic plaques

| Lipid fractions | Shape change; %

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| nat-LDL | mox-LDL | Plaques | |

| Chloroform extract | |||

| Neutral lipids | 3 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 4 ± 2 |

| Sphingomyelin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Phosphatidylcholine | 0 | 0 | 3 ± 2 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine | 2 ± 1 | 7 ± 3 | 10 ± 3 |

| Butanol extract | |||

| LPA | 13 ± 5 | 100 | 100 |

Lipids were extracted from nat-LDL, mox-LDL, and human atherosclerotic plaques by a two-step procedure and separated by TLC. Lipids equivalent to 0.1 mg of protein were added to platelet suspensions for measurement of platelet shape change. The absolute amounts of lipids that were added varied according to the different LDL preparations and plaque specimens and ranged for phospholipids in mox-LDL (in nmol): sphingomyelin, 14–40; phosphatidylcholine, 30–60; phosphatidylethanolamine, 0.2–0.8; lysophosphatidylcholine, 3–6; LPA, 0.04–0.1. The highest activity was found in the LPA fractions of mox-LDL and plaque, which were set to 100%. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of shape change induced by mox-LDL and by native LDL spiked with LPA extracted from mox-LDL

| Shape change, % | |

|---|---|

| LPA extract of mox-LDL | 100 |

| mox-LDL | 32 ± 14 |

| LPA extract of mox-LDL + nat-LDL | 27 ± 10 |

| nat-LDL | 4 ± 2 |

| Blank extract + nat-LDL | 5 ± 2 |

The biological activity of LPA extracted from mox-LDL was compared with the biological activity of the respective mox-LDL. The amount of LPA extracts added to the platelet suspension ranged from 3 pmol to 12 pmol and was equivalent to the amount of mox-LDL from which LPA was extracted. For spiking of nat-LDL with the LPA extract of mox-LDL, ethanol of the LPA extract was evaporated and incubated for 10–15 min at 37°C with the respective native LDL from which mox-LDL has been prepared. Incorporation of LPA into nat-LDL was >90% as measured by radioactivity of [3H]LPA. The same amount of nat-LDL and mox-LDL (5–15 μg of LDL protein) was added to the platelet suspension. The activity of the LPA extract of mox-LDL in individual experiments was set to 100%. Values are mean ± SD of nine experiments with different LDL preparations. Blank extract is eluate from blank silica gel.

LPA in mox-LDL Stimulates Actin Stress-Fiber Formation in Endothelial Cells.

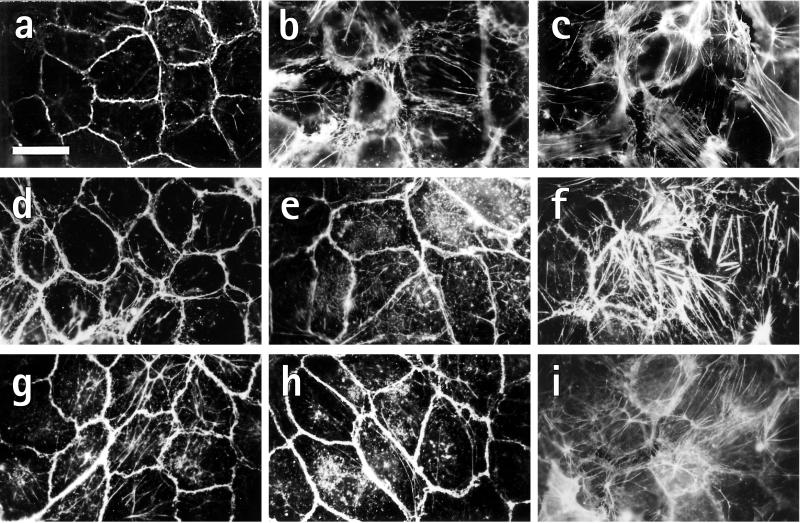

LPA elicits multiple biological functions in addition to platelet activation, such as cell proliferation, monocyte chemotaxis, and contraction of fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells (28). We found that exposure of a confluent human endothelial cell layer to mox-LDL (Fig. 3b) or LPA (Fig. 3c) for 2 min dramatically changed the shape and cytoarchitecture of the endothelial cells from a cobblestone-like pattern with a dense peripheral actin ring in resting cells (Fig. 3a) to a pattern of round cells, dissolution of the peripheral actin ring, stress-fiber formation, and intercellular gaps. Similar morphological changes of endothelial cells were observed after incubation with LPA extracted from mox-LDL (Fig. 3f) but not with nat-LDL (Fig. 3d) or LPA-extracts from nat-LDL (Fig. 3e). The LPA-receptor antagonist NPTyrPA completely blocked the morphological changes induced by mox-LDL (Fig. 3g) and LPA (Fig. 3h) but not thrombin (Fig. 3i). The data indicate that LPA is the substance in mox-LDL that rapidly induces cell rounding, stress-fiber formation, and gap formation in endothelial cells.

Figure 3.

mox-LDL induces cell rounding and actin stress-fiber formation in confluent human endothelial cells through activation of the LPA receptor. Cells were incubated for 2 min at 37°C with 0.1% ethanol (a; control), 250 μg/ml mox-LDL (b), 1 μM LPA (c), 250 μg/ml nat-LDL (d), LPA eluate from 250 μg of nat-LDL (e), or LPA eluate from 250 μg of mox-LDL (f). (g–i) Cells were also pretreated with NPTyrPA (10 μM) for 60 min before incubation with mox-LDL (g), LPA (h), or thrombin (i; 1 unit/ml). Cells were stained for F-actin with rhodamine phalloidine. The experiment is representative of four others that gave similar results. (Bar = 30 μm.)

LPA Accumulates in Atherosclerotic Lesions.

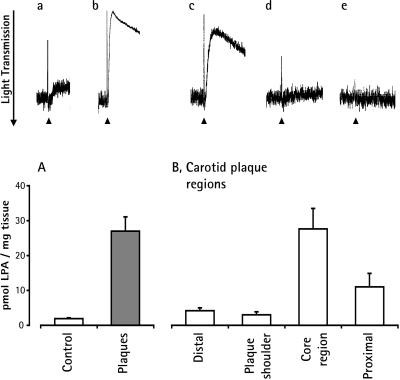

To determine whether LPA was present in atherosclerotic lesions in vivo, we analyzed LPA in surgical endarterectomy specimens of human carotid and femoral atherosclerotic arteries and an atheromatous aorta. LPA extracted from atherosclerotic plaques induced platelet shape change, which was inhibited by preincubation of platelets with the LPA-receptor antagonists NPTyrPA and NPSerPA. LPA extracted from arterial intima devoid of atherosclerosis contained only a small amount of biologically active LPA (Fig. 4 Upper). Only one major peak of biological activity comigrating with [3H]LPA was found in the butanol extract of plaques. The biological activity also comigrated with [3H]LPA after subsequent separation on two-dimensional TLC (data not shown). All atherosclerotic specimens—except one fibrosclerotic, heavily calcified carotid plaque—contained an increased amount of LPA. The levels of LPA ranged from 10 pmol/mg to 49 pmol/mg in atheromatous plaques and from 1.2 pmol/mg to 2.8 pmol/mg in normal arterial tissue. The mean level of LPA increased 13-fold in atheromatous plaques as compared with normal arterial tissue (Fig. 4 Lower A). LPA was the primary platelet-activating lipid in atherosclerotic plaques. Other lipid fractions contained minor biological activity as compared with LPA (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Analysis of LPA in human atherosclerotic plaques and normal arterial tissue. (Upper) Shape change induced by equivalent amounts of LPA extracts of carotid arterial tissue devoid of atherosclerosis (a), the lipid-rich core of a carotid plaque (b), femoral plaque (c), preincubation of platelets with NPTyrPA (10 μM) plus LPA extract of femoral plaque (d), and preincubation of platelets with NPSerPA (5 μM) plus LPA extract of femoral plaque (e). (Lower A) Determination of biologically active LPA in surgical specimens of normal arterial tissue (n = 6; control) and lipid-rich atherosclerotic plaques (n = 10). (Lower B) Determination of biologically active LPA in different regions of carotid atherosclerotic lesions (n = 4). Values are mean ± SEM.

The histopathology of carotid endarterectomy specimens shows marked differences in the various regions, which can be assigned to different stages of atherosclerosis (12). We measured the LPA content in four regions to correlate the LPA content with the plaque morphology. We found that the amount of LPA was highest in the lipid-rich core and the proximal region (Fig. 4 Lower B). The lipid-rich core region was characterized histologically by large extracellular lipid deposits and beds of foam cells. The proximal region contained connective tissue, foam cells, and small pools of lipid deposits. In the shoulder region, collagen fibers and connective tissue predominated; the distal region was mainly normal intima. These two regions contained little LPA. Therefore, LPA accumulated mainly in the regions that were rich in extracellular lipid deposits and foam cells, structures known to contain oxidized lipoproteins and their degradation products.

DISCUSSION

At present, two pathways for the cellular formation of LPA are known. LPA is formed by and released from activated platelets (16, 29, 30) and increases during blood clotting where it becomes bound to serum albumin (18). LPA can also be generated by the action of secretory phospholipase A2 on microvesicles shed from blood cells challenged with inflammatory stimuli (31). Our results show that mild or minimal oxidation of LDL generates biologically active LPA and indicate a pathway for the production of LPA, which might be significant for the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and cardiocerebrovascular diseases for several reasons.

Oxidation of LDL occurs in the intima of atherosclerotic lesions, and mox-LDL and mm-LDL are considered to be of pathophysiological importance during the early steps of atherogenesis. In confluent endothelial cells, LPA in mox-LDL induced a rapid structural alteration of endothelial integrity, one key event in the formation of the early lesion. Dissolution of the endothelial dense peripheral actin band, cell contraction, actin stress-fiber formation, and intercellular gap formation increase endothelial permeability (21, 32), eventually leading to an insudation of plasma proteins such as LDL. Indeed, oxidized LDL and LPA stimulate endothelial permeability (4, 33), and endothelial stress-fiber formation and subendothelial retention of LDL occur during early lesion development in vivo (1, 34).

The advanced atherosclerotic lesion becomes life-threatening through sudden plaque disruption with superimposed thrombosis (7). We found that LPA accumulated in human atherosclerotic plaques in vivo and was the main platelet-activating lipid of plaques. The region of the carotid atherosclerotic lesion that had the highest content of LPA was the lipid-rich core. Sudden rupture of the cap covering the lipid-rich core will expose LPA, thereby triggering platelet activation with the eventually fatal consequences of an occluding arterial thrombus.

Besides the rapid activation of platelets and endothelial cells shown in the present study, it is likely that LPA in mm-LDL or mox-LDL also stimulates the contraction and proliferation of smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts (28). Furthermore, because LPA is chemotactic for monocytes (35), the possibility exists that subendothelial LPA in oxidized LDL attracts monocytes into the vessel wall. Thus, LPA present in oxidized LDL is a potentially atherothrombogenic molecule that may initiate as well as sustain the formation of atherosclerotic plaques and arterial thrombi. Inhibition of the LPA receptor(s) could be used in the prevention and therapy of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease and merits further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank U. Wielert and C. Meister for expert technical assistance. Some of the experiments are part of the thesis of K.J.Z. at the University of Munich. G.T. was supported by National Institutes of Health/U.S. Public Health Service Grant HL 61469 and is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association. R.B. was supported by NIH HL-16660. This work was supported by the Ernst und Berta Grimmke-Stiftung, by the August-Lenz-Stiftung, and by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants Si 274/6, GRK 438, Ae 11, and SFB 413.

ABBREVIATIONS

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- mox-LDL

mildly oxidized LDL

- mm-LDL

minimally modified LDL

- nat-LDL

native LDL

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- PAF

platelet-activating factor

- NPTyrPA

N-palmitoyl tyrosine phosphoric acid

- NPSerPA

N-palmitoyl serine phosphoric acid

References

- 1.Ross R. Nature (London) 1993;362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinberg D. Circulation. 1997;95:1062–1071. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berliner J A, Navab M M, Fogelman A M, Frank J S, Demer L L, Edwards P A, Watson A D, Lusis A J. Circulation. 1995;91:2488–2496. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rangaswamy S, Penn M S, Saidel G M, Chisolm G M. Circ Res. 1997;80:37–44. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berliner J A, Territo M C, Sevanian A, Ramin S, Kim J A, Bamshad B, Esterson M, Fogelman A M. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1260–1266. doi: 10.1172/JCI114562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez-Ortiz A, Badimon J J, Erling F, Fuster V, Meyer B, Mailhac A, Weng D, Shah P K, Badimon L. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1562–1569. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90657-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falk E, Shah P K, Fuster V. Circulation. 1995;92:657–671. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meraji S, Moore C E, Skinner V O, Bruckdorfer K R. Platelets. 1992;3:155–162. doi: 10.3109/09537109209013176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weidtmann A, Scheithe R, Hroboticky N, Lorenz R, Siess W. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1131–1138. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.8.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrono C, FitzGerald G A. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2309–2315. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulz T, Schiffl H, Scheithe R, Hrboticky N, Lorenz R. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:564–571. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandl R, Richter T, Haug K, Wilhelm M G, Maurer P C, Nathrath W. Circulation. 1997;96:3360–3368. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Negrescu E V, Luber de Quintana K, Siess W. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1057–1061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjerve K S, Daae L N W, Bremer J. Anal Biochem. 1974;58:238–245. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90463-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerrard J M, Robinson P. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;795:487–492. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(84)90177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson S P, McConnel R T, Lapetina E G. Biochem J. 1985;232:61–66. doi: 10.1042/bj2320061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugiura T, Tokumura A, Gregory L, Nouchi T, Weintraub S T, Hanahan D J. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;311:358–368. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tigyi G, Miledi R. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21360–21367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liliom K, Guan Z, Tseng J-L, Desiderio D M, Tigyi G, Watsky M A. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1065–C1074. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.4.C1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartlett G R. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:466–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Essler M, Amano M, Kruse H-J, Kaibuchi K, Weber P C, Aepfelbacher M. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21867–21874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siess W. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:58–178. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bittman R, Swords B, Lilioms K, Tigyi G. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:391–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liliom K, Bittman R, Swords B, Tigyi G. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:616–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo Z, Liliom K, Fischer D J, Bathurst I C, Tomei D, Kiefer M C, Tigyi G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14367–14372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukushima N, Kimura Y, Chun J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6151–6156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An S, Bleu T, Hallmark O G, Goetzel E J. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7906–7910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moolenaar W H. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12949–12952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Billah M M, Lapetina E G, Cuatrecasas P. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:5399–5403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eichholtz T, Jalink K, Fahrenfort I, Moolenaar W H. Biochem J. 1993;291:677–680. doi: 10.1042/bj2910677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fourcade O, Simon M-F, Viodé, Rugani N, Leballe F, Ragab A, Fournié B, Sarda L, Chap H. Cell. 1995;80:919–927. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia J G N, Davis H W, Patterson C E. J Cell Physiol. 1995;163:510–522. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulze C, Smales C, Rubin L L, Staddon J M. J Neurochem. 1997;68:991–1000. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68030991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colangelo S, Langille B L, Steiner G, Gottlieb A. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:52–56. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou D, Luini W, Bernasconi S, Diomede L, Salmona M, Mantovani A, Sozzani S. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25549–25556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]