Abstract

Mesothelioma is a highly malignant neoplasm with no effective treatment. Conditionally replicative adenoviruses (CRAds) represent a promising new modality for the treatment of cancer in general. A key contribution in this regard is the introduction of tumor-selective viral replication for amplification of the initial inoculum in the neoplastic cell population. Under ideal conditions following cellular infection, the viruses replicate selectively in the infected tumor cells and kill the cells by cytolysis, leaving normal cells unaffected. However, to date there have been two limitations to clinical application of these CRAd agents; viral infectivity and tumor specificity have been poor. Herein we report on two CRAd agents, CRAd-S.RGD and CRAd-S.F5/3, in which the tumor specificity is regulated by a tumor-specific promoter, the survivin promoter, and the viral infectivity is enhanced by incorporating a capsid modification (RGD or F5/3) in the adenovirus fiber region. These CRAd agents effectively target human mesothelioma cell lines, induce strong cytoxicity in these cells in vitro, and viral replication in a H226 murine xenograft model in vivo. In addition, the survivin promoter has extremely low activity both in the non-transformed cell line, HMEC, and in human liver tissue. Our results suggest that the survivin-based CRAds are promising agents for targeting mesothelioma with low host toxicity. These agents should provide important insights into the identification of novel therapeutic strategies for mesothelioma.

Keywords: Survivin gene, Tumor-specific promoter, Transcriptional targeting, Adenoviral vector and mesothelioma

Mesotheliomas are neoplasms of the serosal membranes of body cavities, arising principally from the pleura, peritoneum, and tunica vaginalis. Eighty percent of mesotheliomas involve the pleural space, and they represent the most common primary tumor of the pleural cavity. Despite its relative rarity in the United States, mesothelioma remains an area of special interest in pulmonary medicine because of its increasing frequency, dismal prognosis, and attendant medicolegal issues related to asbestos exposure. Mesotheliomas are classified into three general categories: diffuse malignant, localized benign, and localized malignant. Ten percent of localized mesotheliomas are malignant, but they are often low-grade and potentially resectable.1,2 Diffuse pleural mesothelioma account for the preponderance of primary pleural tumors. No particular therapy has proven reliably superior to supportive therapy alone in terms of survival. The median survival for patients without treatment is 6 to 8 months, quite similar to the survival for those who received therapy, including chemo- or radiotherapy and surgery.3-12 There is no widely accepted newer treatment strategy for patients with pleural mesothelioma. To that end, a novel therapeutic approach to pleural mesothelioma is warranted.

Gene therapy has shown potential for the treatment of other solid cancers. In a recent summary of gene therapy clinical trials worldwide (1989 to 2004), 66% of such trials addressed cancers.13 Strategies for anti-mesothelioma therapies by gene therapy include: (1) molecular chemotherapy based on the use of “suicide genes,” such as the herpes simplex thymidine kinase gene14,15 and cytosine deaminase,16 in which DNA that encodes an enzyme capable of generating a toxic metabolite is transferred to tumor cells followed by the administration of a nontoxic enzyme substrate; (2) genetic immunopotentiation based on the capacity to destroy tumor cells either via T lymphocytes, natural killer cells, or macrophages17 or by use of immunomodulators, such as IL-218 and TGF-β19; (3) mutation compensation based on correction of oncogenes or tumor-suppresser genes, such as K-ras, p53, P16 INK4A, P14, and NF2 genes.20-24 Thus, in this regard, a number of gene therapy approaches for mesothelioma have been developed. Furthermore, gene therapy of mesothelioma may be useful in combination with conventional therapies.

Recently, the use of replicative viral delivery represents a novel approach to such neoplastic diseases, including malignant mesothelioma.25 In this strategy, target tumor cell killing by the viral agent is achieved via direct consequence of the viral replication.26 It is apparent that the specificity of the viral agent for achieving tumor cell killing via replication (“oncolysis”) is the functional key to successful exploitation of these agents. To this end, an ideal viral agent would possess two characteristics: (1) high infectivity, in that viral vectors would have the capacity to infect tumor versus non-tumor cells; and (2) tumor specificity, in that viral vectors would possess a relative preference for replication in tumor versus non-tumor cells. However, both viral infectivity and specificity have been poor when using current applicable conditionally replicative viral vectors (CRAds). To develop infectivity enhanced and tumor-specific CRAd agents for mesotheliomas, better constructs are needed.

To overcome these two disadvantages of poor infectivity and specificity, many approaches have been described. Important in the consideration of efficient infection is the knowledge that cells may be resistant to Ad infection because of their lack of the Coxsackie adenovirus receptor (CAR) on their cell surfaces that result in poor infectivity.27 To circumvent this, genetic and immunologic alterations to the virus fiber that use CAR-independent pathways have been identified. An example of this is the use of the RGD motif in the fiber knob of the Ad. This capsid modification seems to facilitate Ad binding and entry into tumor cells via integrin receptors that are abundantly expressed on many solid tumor cells.27 Additional capsid modifications have been explored to obtain infectivity enhancement of Ads, including AdF5/3,28Ad5-pk7,29 and Ad5-CK.30 Alternately, transcriptional targeting exploits promoters that display preferentially in tumor cells but not in normal host cells.26 An ideal tumor-specific promoter (TSP) for transcriptional targeting exhibits selective high activity in tumor cells (termed a “tumor on” phenotype). To mitigate hepatoxicity on systemic delivery, candidate promoters additionally exhibit low activity in the liver (termed a “liver off” phenotype). To develop TSP-CRAds, one of the most widely used methods is to drive Ad E1 gene expression with a selected promoter, as Ad E1 is the main element that drives viral replication. In this method, a CRAd replicates only in tumor cells, killing cells by oncolysis, but not in normal host cells, thereby avoiding the toxicity of the CRAd agent. Many TSPs have been explored for specific cancers, such as the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for prostate cancer and the α-fetoprotein (AFP) promoter for hepatocarcinoma.31,32 Recently we reported a novel TSP, the survivin promoter, which exhibited a tumor on/liver off phenotype in vitro and in vivo in a wide range of neoplastic tumors.33 This promoter has also been reported to exhibit a radiation-responsive promoter and cisplatin-sensitive capabilities.34,35 Therefore, the survivin promoter is an excellent candidate to drive E1 expression in the development of a new CRAd agent.

In this study, we further constructed conditionally replicative adenoviral vectors, in which the Ad E1 gene was regulated by using the survivin promoter as a TSP and viral infectivity was enhanced with a capsid modification (RGD or F5/3) by which Ad vector target to mesothelioma cells occurred via a CAR-independent pathway. We verified that these infectivity enhanced and tumor-selected vectors, especially CRAD-S.F5/3, replicated in mesothelioma cells and in a H226 xenograft murine model. We also showed that the survivin promoter had very low activity compared with the other TSPs in human liver slices. Our data thus indicate that the CRAd-S.F5/3 is an excellent candidate for translation into a clinical trial for the treatment of malignant mesothelioma in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, Tissues, and Animals

Human mesothelioma cell lines, H226 (purchased from ATCC), H 2373, mmp4, and BC286-2b (gifts from Dr. J. Kolls, Pittsburgh, PA) were used in this study. All cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 complete medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment under humidified conditions. Non-transformed human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC), used as a survivin expression-negative control, were purchased from Cambrex BioScience Company (Walkersville, MD) and cultured in the medium specially purchased from the same company.

Human liver samples were obtained from hepatectomy remnants not needed for diagnostic purpose after liver transplantation after institutional review board approval. To generate liver tissue slices, tissue was cut in consecutive 0.5-mm slices using the Krumdieck tissue slicer (Alabama Research Development, Munford, AL). Sequential slices were then cultured in 24-well plates in RPMI supplemented with 10% bovine fetal serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 5 μg/ml insulin. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Three tissue slices were examined per group.

Female BALB/c nude mice, 6 to 8 weeks of age (Charles River, Wilmington, MA), were used for in vivo experiments. All animals received humane care based on the guidelines set by the American Veterinary Association. All of the experimental protocols involving live animals were reviewed and approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Recombinant Adenoviruses

Ad5-CMV, Ad5-Cox-2, Ad5-CXCR4, Ad5-EGP-2, Ad5-HPR, Ad5-SLPI, Ad5-MsLn, and Ad5-Survivin are replicative-defective Ads containing a luciferase reporter gene driven by the TSP—Cox-2, CXCR4, EGP-2, HPR, SLPI, MsLn, surviving, and a control CMV promoter, respectively—in the E1 region, as has been previously described.33,36-40 These Ads were used in this study for evaluating the transcriptional activities of the TSPs by means of the expression of a luciferase reporter gene in mesothelioma cells.

Ad5.RGD, Ad5.pk7, Ad5.F5/3, Ad.CK and Ad5.pk7.RGD are replicative-defective Ads containing a luciferase reporter gene driven by the CMV promoter in the E1 region and incorporating a capsid modification, RGD, pk7, F5/3, Ad.CN, and pk7.RGD, respectively, as described previously.28-30 These Ads also were used for evaluating the enhancement of viral infectivity by means of the expression of a luciferase reporter gene in mesothelioma cells.

All the Ads used are listed in Table 1. The viruses are all isogenic, propagated in 293 cells, and purified by double CsCl density centrifugation. The firefly luciferase gene incorporated into the Ads contains a modified coding region for firefly luciferase (pGL3; Promega) that has been optimized for monitoring transcriptional activity in transfected eukaryotic cells. The luciferase activity of the cells infected with each of Ads was normalized and reported as fold-activity of cells infected with Ad5.CMV.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Adenoviral Vectors Used in this Study

| Virus name | Promoter | Reporter | E1 | E3 | Modification | Replication competent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad5-CMV | CMV | Luciferase | No | No | No | No |

| Ad5-Cox-2 | Cox-2 | Luciferase | No | No | No | No |

| Ad5-CXCR4 | CXCR4 | Luciferase | No | No | No | No |

| Ad5-EGP-2 | EGP-2 | Luciferase | No | No | No | No |

| Ad5-HPR | HPR | Luciferase | No | No | No | No |

| Ad5-SLPI | SLPI | Luciferase | No | No | No | No |

| Ad5-Mk | Midkine | Luciferase | No | No | No | No |

| Ad5-Survivin (Ad5-S) | Survivin (S) | Luciferase | No | No | No | No |

| Ad5.RGD | CMV | Luciferase | No | No | RGD4C | No |

| Ad5.F5/3 | CMV | Luciferase | No | No | F5/3 | No |

| Ad5.pk7 | CMV | Luciferase | No | No | pk7 | No |

| Ad5.CN | CMV | Luciferase | No | No | CN (canine knob) | No |

| Ad5.CN.pk7 | CMV | Luciferase | No | No | CN.pk7 | No |

| Adwt | Native | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| CRAd-S.RGD | Survivin (S) | No | Yes | Yes | RGD4C | Yes |

| CRAd-S.F5/3 | Survivin (S) | No | Yes | Yes | F5/3 | Yes |

Physical particle concentration (vp/ml) was determined by OD 260 nm reading. All experiments were based on vp numbers, although a plaque assay was performed to ensure sufficient quality of the virus preparation. The ratios of vp/pfu (plaque forming units) were 3.9 to 60 among all Ad vectors tested.

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction for Detection of the Expression of the Survivin Gene, the Ad5 E1 Gene, and the E4 Gene

For survivin gene expression determinations, total cellular RNA was extracted from 5 × 105 mesothelioma cells (H226, H2373, Meso MMp4, and Meso BL286-2b) or from the non-transformed normal control, HMEC, by using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), followed by treatment with DNase to remove any possible contaminating DNA from the RNA samples. The fluorescent TaqMan probe (6FAM-TGACGACCCCATAGAGGAACATAAAAAGCAT) and the primer pair (forward primer TGGAAGGCTGGGAGCCA; reverse primer GAAAGCGCAACCGGACG) used for real-time PCR in the analysis of the survivin mRNA were designed using Primer Express 1.0 (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA) and synthesized by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the internal control. A negative control with no template was performed for each reaction series. RT-PCR reaction was performed using a LightCycler System (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). Thermal cycling conditions were subjected to 2 min at 50°C, 30 min at 60°C, 5 min at 95°C, then 40 cycles of 20 seconds at 94°C and 1 min at 62°C. Data were analyzed with Light Cycler software.

For quantification of the Ad E1 and E4 gene, total cellular RNA or DNA was extracted from cells or cell cultures in 12/24 well plates using the RNeasy mini RNA extraction kit or a blood DNA kit (Qiagen), respectively. Both RNA and DNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase and DNase-free RNase, respectively, to remove possible contamination. The Ad5 E1 gene was detected in RNA samples by using an oligo pair (forward primer-5′AACCAGTTGCCGTGAGAGTTG and reverse primer-5′CTDGTTAAGCAAGTCCTCG ATACA) and the probe (ORF6-CACAGCTGGCGACGCCCA); the Ad5 E4 gene was detected in DNA samples by using an oligo pair (forward primer-5′GGAGTGCGCCGAGACAAC and reverse primer-5′ACTACGTC CGGCGTTCCAT) and the probe (ORF6-TGGCATGACACTACGACCAACACGATCT).

Negative controls and an internal control were performed for each reaction series as described.

Transcriptional and Transductional Evaluations In Vitro

Mesothelioma cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were plated on 24-well plates in 1 ml of medium as described previously. The next day, cells were infected with recombinant Ads (Ad5-CMV, Ad5-Cox-2, Ad5-CXCR4, Ad5-EGP-2, Ad5-HPR, Ad5-SLPI, Ad5-MsLn, and Ad5-Survivin for transcription or Ad5.RGD, Ad5pk7, Ad5F5/3, and Ad5pk7.RG for transduction) at 100 vp/cell for 2 hours in 200 μl of the medium containing 2% fetal calf serum (FCS). The cells were then washed once with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 1 ml of the medium containing 10% FCS was added to each well. After 48 hours’ incubation, cells were washed with PBS, and luciferase activity was determined using the Reporter Lysis Buffer and Luciferase Assay System of Promega (Madison, WI) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and luciferase activities were standardized to relative light units (RLU) values of the CMV promoter (the CMV promoter activity being set to 100%). The transcriptional levels of the TSP in mesothelioma cells were evaluated by expression activity of the luciferase reporter gene in Ads under the control of these different TSPs. The transductional levels of Ads in mesothelioma cells were evaluated by the expression activity of the luciferase reporter gene driven by the same CMV promoter but incorporating a different capsid modification in the Ad fiber region.

Development of CRAd Agents

The CRAd genomes were constructed via homologous recombination in Escherichia coli (Fig. 1) as described previously.26 Briefly, DNA fragments containing nucleotides −230/+30 were cut with Bam HI and Hind III restriction endonucleases from the clone pLuc-cyc1.2 (from Dr. F. Li, Buffalo, NY) and subcloned into the plasmid pBSSK (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using the same restriction sites. A SV40 poly-A (PA) fragment was then cut with Xba I/Bam HI from a pGL3B vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and inserted into the pBSSK using the same restriction sites. A generated clone named pBSSK/PA/Survivin was used to create shuttle vectors. DNA fragments containing SV40 PA and survivin promoter were cut with Not I/Xho I and subcloned into a pScsE1 plasmid, which was a gift from Dr. D. Nettelbeck (Erlangen, Germany). It contains the E1 gene with the same restriction sites. The shuttle vectors pScs/PA/S were thus generated.

FIGURE 1.

Construction of the CRAd agents. A 260 bp of the survivin promoter was amplified from the clone pLuc-cyc1.2 and constructed in a pScE1 vector. A poly-A signal sequence was inserted between the ITR and Survivin promoter to terminate the transcription signal from the ITR. Constructed clones were recombinated with pVK503C or AdF5/3 vector which contain the E3 gene and a RGD4C or F5/3 fiber motif to generate the CRAd-S.RGD and CRAd-S.F5/3, respectively. Both capsid modifications are located in the region of the Ad fiber.

The Ad vector, pVK503c,25 was a kind gift from Dr. V. Krasnykh (M.D. Anderson, Houston, TX), and contains both the E3 gene and a capsid-modified RGD. After cleavage with Pme I, the shuttle vectors were recombined with Cla I linerized pVK503c to generate a CRAd genome with a RGD-modified fiber. The resultant plasmids encoding the surviving-promoter CRAds were linearized with Pac I and transfected into 911 cells using superfect (Qiagen). Generated viruses were propagated in D65 cells (a glioma cell line in which survivin gene is over-expressed) and purified by double CsCl density gradient centrifugation, followed by dialysis against PBS containing 10% glycerol. The viruses, CRAd-S.RGD, were titrated by a plaque assay, and vp number was determined spectrophotometrically based on absorbance at a wavelength of 260 nm. The viruses were stored at −80°C until use. The CRAd-S.F5/3 was generated by a similar method except that the Ad vectors pVK500F5/3,28 which contained a F5/3 capsid modification, were already stored in our laboratory. Wild-type Ad5 (Adwt) and Ad5.Survivin33 were used as replication-positive and -negative controls, respectively, in the CRAd agent analysis.

Analysis of Transduction of CRAd Agents in Tumor Cell Lines

Mesothelioma cells (1 × 105/well) were cultured as discussed, infected with 100 vp/cell Ad-S, CRAd-S.RGD, CRAd-S.F5/3, or Adwt in infection medium containing 2% FBS, and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment. After 3-hour incubation, the infection medium was removed, and the cells were washed three times to remove un-internalized viruses. DNA was isolated from cells derived from each well via the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen), and quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed. Ad E4 gene copy numbers were detected and normalized to the human actin gene.

Analysis of Replication of CRAd Agents in Tumor Cells

Mesothelioma cells (1 × 105/well) were cultured as discussed, infected with 100 vp/cell Ad-S, CRAd-S.RGD, CRAd-S.F5/3, or Adwt in infection medium containing 2% FBS, and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment. After 3-hour incubation, infection medium was removed, the cells were washed three times to remove un-internalized viruses, and cells were placed in fresh culture medium with 10% FBS. Media from triplicate wells were collected 1, 3, and 9 days later, and DNA was extracted from 200 μl of media with the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed as described above. Ad E4 gene copy numbers were detected.

In Vitro Analysis of Cytocidal Effects

The in vitro cytocidal effects of the CRAd agents were analyzed by determining the viability of the cells with crystal violet staining after infection. Briefly, 25,000 mesothelioma cells/well were plated on a 24-well plate; cells were infected at 500, 100, 20, 4, 0.8, and 0 vp/cell with Adwt, CRAd-S.F5/3, CRAd-S.RGD, or reAd-S in infection medium, respectively. Two hours later, the infection medium was replaced with the appropriate complete medium. After 10-day incubation, the cells were fixed with 10% buffered formalin for 10 minutes and stained with 1% crystal violet in 70% ethanol for 20 minutes, followed by washing three times with tap water and air drying. Trypan blue exclusion experiments were also performed as described elsewhere.

Replication of CRAd Agents on a H226 Murine Xenograft Model

The H226 tumor cells were verified to have 95% viability by Trypan blue exclusion. BALB/c nude mice were subcutaneously inoculated in their flanks with 5 × 106 viable H226 cells (n = 5 per group). When the tumor reached 5 mm in widest diameter, 5 × 108 vp of each viral vector (Adwt, Ad-S, CRAd-S.RGD, or CRAd-S.F5/3) were injected intratumorally. The mice were killed on day 1 or day 7, and the tumor samples were harvested. The DNA was isolated from the tumor samples as described previously. DNA samples from xenografts were stored at −80° C until use. E4 gene copy numbers were detected by RT-PCR and normalized against the human actin gene.

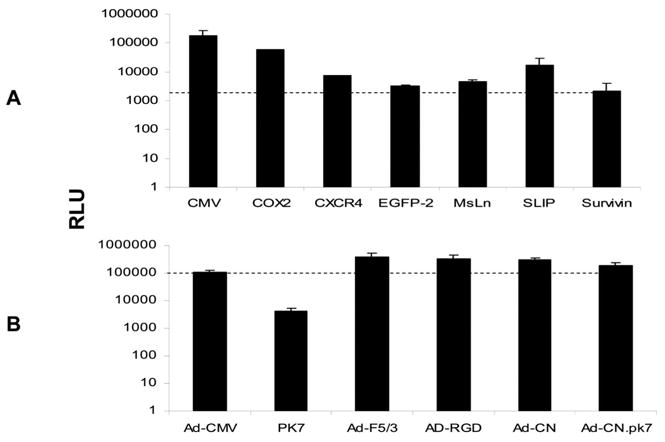

Analysis of Promoter and Transductional Activities in Human Liver Slices

Human liver was obtained from hepatectomy specimens after liver transplantation for evaluation of TSP activity. To generate liver tissue slices, tissue was cut in consecutive 0.5-mm slices using the Krumdieck tissue slicer. Sequential slices were then cultured in 24-well plates in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 5 μg/ml insulin. The tissue slices were infected with 500 vp/cell of Ad vector, Ad5-CMV, Ad5-Cox-2, Ad5-CXCR4, Ad5-EGF-2, Ad5-MsLn, Ad5-SLIP, or Ad5-Survivin with infection medium, respectively. After 3-hour infection, the liver slices were washed once with PBS, and 10% FBS was added for 48-hour incubation at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Two days after infection, luciferase activities were detected by conventional means and shown as RLU % (relative light units) of the luciferase activity of the CMV promoter.

Similar experiments were performed for transductional activity, except the vectors used were Ad5-CMV, Ad5.pk7, Ad5.F5/3, Ad5.RGD, Ad5.CN, and Ad5.CN.pk7, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

We used Student’s t test for statistical analysis, in which p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Evaluation of Tumor-Specific Promoters In Vitro

The activities of seven TSPs (the Cox-2, CXCR4, EGP-2, HPR, SLPI, MsLn, and survivin promoters) were evaluated in four human mesothelioma cell lines: H226, mmp4, H2373, and BC286-2b. The backbone structure of the Ad vectors was identical for all constructs, which additionally contained a luciferase reporter gene derived from a pGL3 plasmid (Promega) that specifically drove luciferase gene expression. The activities of the Ad vectors in tumor cells were normalized to an Ad5-CMV vector that had identical backbone but used the CMV promoter. The results are shown in Figure 2, A and B. Three of the seven TSPs (the survivin, CXCR4, and MsLn promoters) exhibited higher promoter activity than the other TSPs in the mesothelioma cell lines. The mean activities for the four cell lines were 8.9 % for the survivin promoter, 4.2 % for the CXCR4 promoter, and 3.3 % for the MsLn promoter compared with that of the CMV promoter. The mean activities of the remaining promoters were less than 2% in these same cell lines. These data show that these three promoters have a tumor-on phenotype. In addition, the survivin gene expression was 105 copies/ng RNA (SD ±7.8) in H226 cells, 55 copies/ng RNA (SD ±4.2) in H2372 cells, and undetectable (0) level in survivin expression-negative cell line, HMEC, as detected by RT-PCR (significant difference, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2 C). All of the survivin transcription levels in the different cell line were normalized to that of the housekeeping gene, GAPDH.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Comparison of promoter activities in mesothelioma cells. 5 × 104 cells mesothelioma cells (H226, mmp4, H2373, and BC286-2b) were plated on 24-well plates and infected at a MOI of 100 vp/cell with Ad5-CMV, Ad5-Cox-2, Ad5-CXCR4, Ad5-EGP-2, Ad5-HPR, Ad5-SLPI, Ad5-MsLn, or Ad5-Survivin, respectively. Luciferase activities were analyzed 48 hours later. Results are shown as relative light units (RLU) of luciferase activity. (B) RLU of promoter activities in mesothelioma cells. The percentage of luciferase activity = (RLU induced by TSP)/(RLU induced by the CMC promoter) × 100%. The mean value of four mesothioma cell lines (H226, mmp4, H2373, and BC286-2b) ± SD of triplicate samples is shown. (C) Survivin and GAPDH gene expression in mesothelioma cell lines and HMEC cells, as a survivin expression-negative control. Both mesothelioma and HMEC cells (5 × 104 cells) were plated on 24-well plates. After 48-hour incubation, the RNA was isolated from cells, and both survivin and GAPDH RNA copy numbers were determined by using RT-PCR. The mean value ± SD of triplicate samples is shown. **p < 0.01.

Evaluation of Capsid Modification In Vitro

Six capsid modifications, the pk7, pk7.RGD, RGD, F5/3, CN1, and CN.pk7, were generated for viral infectivity enhancement via a CAR-independent pathway, as described previously. All the Ad vectors had a similar backbone, as described, the difference being the incorporation of alternative modifications in the Ad fiber region (Figure 3). The activities of the modified Ad vectors in the mesothelioma tumor cells were normalized to an Ad5-CMV vector that had the same backbone as the native Ad5 fiber. The data are shown in Figure 3. The Ad vector with the F5/3 modification exhibited the highest reporter activities among the four mesothelioma cell lines tested. They were 184%, 585%, 449%, and 535% in H2373, Meso BC2862b, H226, and MesoMMP4 cell lines, respectively, compared with that of the Ad5-CMV with native fiber. These data show that the F5/3 capsid modifications should be excellent candidates for viral infectivity enhancement in mesothelioma-directed CRAd agents.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of transductional activity in mesothelioma cells with different capsidmodified adenovirus vectors. The mesothelioma cells (5 × 104 cells) were plated on 24-well plates and infected at a MOI of 100 vp/cell Ad5-CMV, Ad5.pk7, Ad5.RGD, Ad5.F5/3, Ad5.CN, or Ad5.CN.pk7, and luciferase activities were analyzed 48 hours later. Results are shown as relative light units (RLU) of luciferase activity. The percentage of luciferase activity = (RLU induced by TSP)/(RLU induced by the CMC promoter) × 100%. The mean value ± SD of triplicate samples is shown.

Transcriptional and Transductional Activities of Modified Ads in Human Liver Slices

Because Ad replication is species-specific and because the major Ad toxicity in gene therapy trials is hepatic, we tested six TSPs and one positive control, the CMV promoter, for activities in human liver specimens in organ culture. To indirectly evaluate viral replication under the control of the selected TSP, we measured luciferase expression after a 2-day infection period with Ad5-CMV, Ad5-Cox-2, Ad5-CXCR4, Ad5-EGP-2, Ad5-HPR, Ad5-SLPI, Ad5-MsLn, and Ad5-Survivin (Figure 4A). Compared with the CMV promoter, the survivin promoter activity was the lowest (1.2% of the activity of the CMV promoter) among the six TSPs. In other words, the activity of the CMV promoter was 83-fold higher than that of the survivin promoter in human liver slices. These data suggest that the survivin promoter has a liver-off phenotype that should result in low toxicity to the human host’s liver.

FIGURE 4.

Transcriptional (A) and transductional (B) activity of Ad vectors in human liver slices. Human liver slices were infected with 500 vp/cell Ad vector, Ad5-CMV, Ad5-Cox-2, Ad5-CXCR4, Ad5-EGPF-2, Ad5-MsLn, Ad5-SLIP, or Ad5-Survivin A and Ad5-CMV, Ad5.pk7, Ad5.F5/3, Ad5.RGD, Ad5.CN1, or Ad5.CN2 B. Two days after infection, luciferase activities were detected by conventional assays and shown as relative light units (RLU).

We also compared the transductional activities of four capsid modified Ad in human liver slices (Figure 4B). The experiments were performed as previously described, except that Ad5-CMV, Ad5.pk7, Ad5.F5/3, Ad5.RGD, Ad5.CN, and Ad5CN.pk7 were used in this experiment. The luciferase expression level served as a surrogate for the Ad transductional activity because the luciferase reporter gene was regulated by the same CMV promoter in all four Ad vectors. Among these Ad vectors, only the pk7 modification exhibited lower (2.6%) transduction activity compared with the CMV promoter in the human liver slices. The transductional activities of the F5/3 modification (RLU 379,297 ± 160,297) and RGD (RLU 322,405±123,050) were 2.3-fold and 2.0-fold higher than that of the CMV promoter (RLU = 160,893 ± 24983), respectively, in human liver slices.

Transductional Activities of Capsid-Modified CRAds in Mesothelioma Cells

Most human tumors contain only low levels of the CAR, the natural endogenous receptor for human adenovirus serotypes 2 and 5. We have previously shown that capsid modification enhances viral infectivity via a CAR-independent pathway. In this study, we compared two capsid modifications, which were incorporated into the fiber region in the CRAd agents and tested in the mesothelioma cell lines H226 and H2373. To avoid viral replication, we infected tumor cells for only 3 hours and immediately isolated DNA from them. We had previously developed evidence that 18 to 24 hours were required to detect Ad DNA in medium, which corresponds to the life cycle of Ad from its entry into the tumor cells to its release from them. The adenoviral copy number was determined by real-time PCR and normalized to the housekeeping gene, actin. The data are shown in Figure 5 A and B. We compared the transductional levels (including viral binding and internalization) of two CRAd agents carrying different capsid modification, the RGD and F5/3, in H226 and H2373 tumor cells. The results indicate that the CRAd-S.F5/3 enhanced the transduction between 2.5- and 3.3-fold in H226 cells and between 1.9- and 3.5-fold in H2373 cells, compared with non-modified Ad, Adwt, and Ad-S at a MOI of 1000 vp/cell. The CRAd-S.RGD enhanced the transduction between 1.6- and 2.2-fold in H226 cells and between 1.3-and 2.4-fold in H2373 cells, compared with non-modified Ad, Adwt, and Ad-S at a MOI of 1000 vp/cell. There are significant differences in CRAd-S.F5/3 compared with Ad-S and Adwt (p < 0.01 in two tested cell lines): CRAd-S.RGD compared with Ad-S (p < 0.01 in both cell lines) and with Adwt (p < 0.05) in the H226 cell line, but not in the H2373 cell line. These data show that the capsid modifications enhance the viral infectivity using either CRAd agent.

FIGURE 5.

Transductional activities of modified CRAd agents in mesothelioma cells. 5 × 104 cells of mesothelioma cells, H226 (A) and H2373 (B) were plated on 24-well plates and infected at a MOI of 1000 vp/cell Ad5-Survivin, CRAd-S.RGD, CRAd-S.F5/3, or Adwt. After 3-hour infection, the cells were washed three times with PBS to remove unbound free adenoviral vectors. The DNA was isolated from cells, and the Ad E4 gene was determined by using RT-PCR. An internal standard, the GAPDH gene, was used for normalizing the DNA amount and the E4 copy number. The ordinate is shown as E4 copies/ng DNA. The mean value ± SD of triplicate samples is shown. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01.

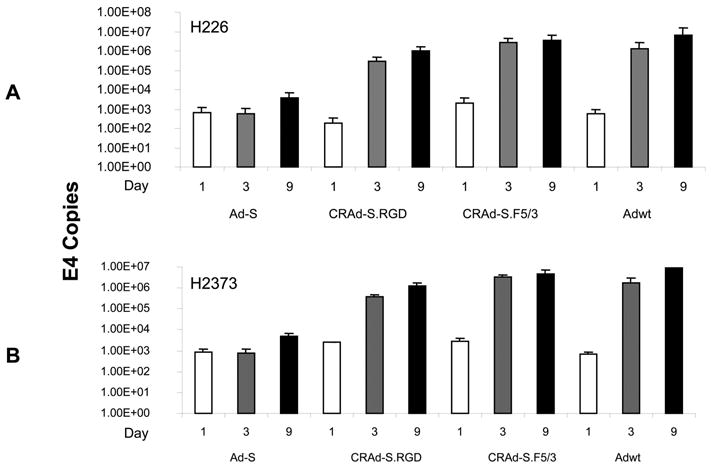

Replication of Survivin-CRAds in Mesothelioma Cell Lines

We used two CRAds, one negative control vector (Ad-S) and one positive control (Adwt), to infect the two tumor cell lines at 100 vp/cell in 24-well plates, as described in Materials and Methods. The 200 μl of medium was collected from each well and spun to remove the cells from medium. DNA was isolated from the medium, and Ad E4 copy numbers were detected by real-time PCR. The data shown in Figure 6 compares E4 copies of Ad vectors in the medium on days 1, 3, and 9 post-infection, as described previously. They exhibited a similar pattern in both H226 (Figure 6A) and H2373 (Figure 6B) cell lines. The replication ratios (calculated from the E4 copies at day 9/E4 copies at day 1) were 1.0, 68, 417, and 3698 for Ads, CRAd-S.RGD, CRAd-S.F5/3, and Adwt, respectively, in H226 cells; and 5.7, 507, 1703, and 11891 for Ads, CRAd-S.RGD, CRAd-S.F5/3, and Adwt, respectively, in H2372 cells. As we expected, the negative control, Ad-S, had no significant replication because of its non-replicative property. Not surprisingly, the positive (Adwt) control exhibited a higher replication rate compared with that of two CRAd agents.

FIGURE 6.

Replication rates of modified CRAd agents in mesothelioma cells, H226 (A) and H2373 (B). The mesothelioma cells (5 × 104 cells) were plated on 24-well plates and infected at a MOI of 100 vp/cell Ad5-Survivin, CRAd-S.RGD, CRAd-S.F5/3, or Adwt. On days 1, 3, and 9 post-infection, 200 μl of medium was collected and spun to remove the cell debris. The DNA was isolated from the medium, and the Ad E4 gene number was determined by using RT-PCR.

Survivin-CRAds Induce Cytotoxicity (Oncolysis) in Mesothelioma Cells

Conventional oncolysis analysis is one of best modalities for monitoring tumor cell killing. Encouraged by the tumor-specific activity of the survivin promoter, we used CRAd-S.RGD and CRAd-S.F5/3 as oncolytic anti-tumor agents. The oncolytic activities of the survivin-CRAds were evaluated for their cell-killing effect in H226, H2373, BC286-2b, and MMp4 cell lines. Cytotoxicity was evaluated after 10 days of incubation via crystal violet staining (Figure 7). Whereas the replication-incompetent Ad-S vector had no cytotoxic effect even at 100 vp/cell, the survivin-based CRAds induced strong cytotoxicity in all tumor cell lines tested. Almost 100% of cells were killed even at a small dose: 1 vp/cell for CRAd-S.F5/3 in H226 and MMp4 cell lines. CRAd-S.F5/3 had a 10-fold stronger killing effect in H226, H2373, and MMp4 cell lines compared with that of Adwt, the exception being BC286-2b cells, in which Adwt had a 10- to 100-fold stronger killing effect than CRAd-S.RGD.

FIGURE 7.

The oncolytic effect of CRAds in mesothelioma and HMEC cells. 5 × 104 cells of either mesothelioma or HMEC cells were plated onto 24-well plates and infected with Ad vector (Adwt, CRAd-S.F5/3, CRAd-S.RGD, or Ad5-Survivin) at the indicated MOIs (100, 10, 1, 0 vp/cell). After 10-day incubation, cells were stained with crystal violet as described in Materials and Methods.

Replication of the Survivin-CRAds In Vivo

The CRAd anti-tumor effect was analyzed in vivo using H226 cells injected subcutaneously in an athymic mouse xenograft model. After establishing and growing the tumor to 5 mm in diameter, 5 × 108 vp of Ad-S, CRAd-S.RGD, CRAd-S.F5/3, or Adwt was injected into the tumor. After day 1 or day 7, the mice were killed, the tumors were collected, and DNA was isolated from them. The Ad E4 copy number was determined by real-time PCR as described. The data shown in Figure 8 indicate that the replication rates are 45.4-, 56.9-, 0.9-, and 2838-fold for CRAd-S.RGD, CRAd-S.F5/3, Ad-S, and Adwt, respectively The viral replication was not seen (0.9-fold) in a non-replicative control, Ad-S, as expected. Of note, the replication-positive control, Adwt, had much higher replication rate (2838-fold) compared with the two CRAd agents (45.5- and 56.9-fold).

FIGURE 8.

Replication rates of CRAd agents in a H226 mesothelioma xenograft. H226 cells (2.5 × 106) in 200 μl of PBS were injected subcutaneously. When the tumor reached 5 mm in diameter, 5 × 108 vp of Ad agents were administered (Adwt, Ad5-Survivin, CRAd-S.RGD, or CRAd-S.F5/3) by an intratumoral injection. The mice (n = 5 per group) were killed on day 1 or day 7, and the tumors were removed. DNA was isolated from the tumor tissues, and Ad E4 and actin gene copy numbers were determined by using RT-PCR. The E4 copy number was normalized as E4 copies/ng DNA.

DISCUSSION

Malignant mesothelioma is an aggressive, treatment-resistant tumor that is increasing in frequency throughout the world. Although the main risk factor is asbestos exposure,41 simian virus 40 (SV40) could also play a role.42 Mesothelioma has an unusual molecular pathology with loss of tumor suppressor genes being the predominant theme, especially the P16INK4A, P14ARF, and NF2genes,23-25 rather than the more common p53 and Rb tumor suppressor genes.43,44 Median survival remains a dismal 6 to 8 months from diagnosis. Palliative chemotherapy is beneficial for mesothelioma patients with high performance status. The role of aggressive surgery remains controversial, and growth factor receptor blockade is still unproven. Gene therapy and immunotherapy are novel strategies for treatment of mesothelioma; however, they still are only used on an experimental basis. Some of these approaches include adenovirus-mediated p14(ARF) gene transfer to human mesothelioma cells,22 adenovirus-mediated HSVtk/GCV treatment of human malignant mesothelioma tumors growing within the peritoneal cavity of nude mice, with eradication of macroscopic tumor in 90% of animals after 30 days,14,15 TSP studies (calretinin promoter),45 and survivin-CRAd targeted to a mesothelioma cell line, H2373.25 Odaka et al. 46 reported that Ad-interferon beta had a high cure rate for mice with early mesothelioma lesions, but this decreased dramatically when tumor size increased. However, the major challenge remains inefficient gene delivery at both transductional and transcriptional targeting levels. In this study, we sought to overcome these limitations by using novel CRAd agents for targeting mesothelioma.

Replication competent adenoviruses have come into focus as promising novel anti-tumor agents for viral oncolysis and enhanced transfer of therapeutic genes.47,48 Tumor specificity and viral infectivity are the keys to CRAd therapy. The former limits the viral replication in normal host cells, but not in tumor cells; the later enhances the viral infectivity by targeting tumor cells via a CAR-independent pathway. We screened seven tumor-specific promoters and six capsid modifications in four mesothelioma cell lines. The mean promoter activity of the four established cell lines was 8.9% for the survivin promoter, 4.2% for the CXCR4 promoter, and 3.3% for the MsLn promoter compared with that of the CMV promoter. The mean activities of the remaining promoters were less than 2% for the four cell lines compared with that of the CMV promoter (Figure 2A). Bao et al.49 have described survivin protein as being undetected in most normal adult mouse tissues. Our data showed that the survivin promoter activity was only 0.07% the activity of the CMV promoter in mouse liver,25 and the survivin promoter exhibited the lowest promoter activity (1.2% activity of the CMV promoter) in human liver slices compared with that of other promoters (Figure 4A). Therefore, the survivin promoter has a tumor-on/liver-off phenotype and was chosen as a TSP to drive Ad E1 expression in CRAd agents against mesothelioma. Specifically, the liver-off status is a critical parameter for clinical application because wt adenoviruses mainly localize to the liver when systemically administered and lead to severe liver dysfunction.50

Adenovirus infection of cells is mediated by the attachment of its capsid fiber protein to the cell surface CAR,51,52 followed by interaction of the penton base with αv integrins that triggers the internalization of these viruses.50 However, most tumor cells express low levels of CAR, leading to poor infection rates.53 To circumvent this problem, the development of CAR-independent Ad vectors that enhance infectivity is critical. We constructed two survivin-CRAds incorporating the capsid modification RGD or F5/3 by which the CRAd agents target to αv integrins28 or Ad3 receptors CD80/CD86/CD4654,55 on the surfaces of tumor cells, respectively. As regards Ad3, we have found CD46 expression to be high in all mesothelioma lines tested, whereas CAR was low in most lines, and CD80 and CD86 generally seemed rather low (data not shown). Both CRAds that incorporated the capsid modification had higher transductional activities, especially CRAd-S.F5/3 versus the Ad5-Survivin, which contained a native fiber with no modification (Figure 4A). Specifically, there was a 3.3-fold and 2.2-fold increase of transductional activity in the H226 cell line and a 3.5-fold and 2.4-fold increase of transductional activity for CRAd-S.F5/3 and CRAd-S.RGD, respectively, in the H2373 cell line compared with the non-modified vector, Ad-Survivin, at 1000 vp/cell.

Survivin protein is a novel member of the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) protein family, which plays an important role in the survival of cancer cells and progression of malignancies.49 Recently, the survivin gene has been described as being selectively expressed in some of the most common human neoplasms, including cancer of the lung,56 pancreas,57 rectum,58 brain,59 and ovary.60 In addition, the survivin protein was undetectable in normal adult mouse tissue49, although trace amounts of survivin gene expression can be detected in human organs. Our data have previously shown that the survivin promoter has high activity in breast cancer, ovarian cancers, and melanoma but has low activity in mouse liver33 and human liver slices (Figure 4A). These data suggest that the survivin promoter has a tumor-on/liver-off phenotype and thus was a good candidate to drive the E1 gene of the CRAd agents in this study while restricting the replication of CRAd agents to mesothelioma cells. Furthermore, the survivin promoter is an excellent TSP to target mesothelioma cells because: (1) The survivin gene expression (105 survivin RNA copies/ng RNA ± 7.8 in H226 and 55 survivin RNA copies/ng RNA in H2373 cells) was detected in the mesothelioma cells but undetectable (0 copy) in the non-transformed normal epithelial cell line, HMEC, which was used in this study as a survivin-negative cell line (Figure 2C); (2) In oncolytic analysis, the CRAd agents exhibited strong cell killing in mesothelioma cells, especially CRAd-S.F5/3, which has at a log lower dose than that of Adwt, the same oncolytic activity in most of the tested cell lines, but no oncolytic effect in the HMEC cells (Figure 7); (3) The lowest activity was seen in the survivin promoter in human liver slices among the seven promoters tested (Figure 4B). Thus, the survivin promoter is an excellent TSP to restrict viral replication in mesothelioma cells and to minimize the toxicity to normal host cells.

Two capsid modifications, RGD and F5/3, were used in this study to enhance the viral infectivity of CRAd agents via a CAR-independent pathway. From transductional activity analysis (Figure 5), all three capsid modifications do enhance the infectivity in mesothelioma cells at an infection dose of 1000 vp/cell. The viral infectivity levels were enhanced two-to threefold compared with non-modified Ad5-Survivin as the control in H226 and H2373 cell lines. Specifically, the F5/3 modification had higher transductional levels than that of the RGD-modified CRAd in mesothelioma cells. However, Adwt had a much higher replication rate versus the two survivin-CRAds both in vitro and in vivo (Figure 6 and Figure 8). A possible explanation for this is that the capsid modification enhances the viral infectivity while harming the viral replication under the study conditions, although there is no independent evidence to verify this hypothesis. Identical results were seen using CRAd agents targeting cholangiocarcinoma (data not shown).

In conclusion, we identified that the human survivin promoter is a tumor-specific regulatory element for targeting mesothelioma. The CRAd agents armed with both the survivin promoter and a capsid modification increase tumor specificity and viral infectivity under in vitro and in vivo conditions. In addition, the survivin-CRAds replicate in H226 tumor cells in a murine xenograft model. The survivin promoter also had extremely low activity in a non-transformed normal epithelial cell line and in human liver tissue. The survivin-CRAds are potentially useful for future experimental clinical applications for human malignant mesothelioma.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. F. Li, D. Nettlbeck, V. Kranykh, and H.J. Wu for providing the vectors for this study.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institute of Health Grants: R01 CA83821, R01 CA 94084, K12 HD01261-02, R01 HL67962, R01 CA93796; the Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation, Inc.; a grant from the UAB Mesothelioma Center of the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center; and Medical Research and Compensation and MHMRC, Australia.

References

- 1.Robinson LA, Reilly RB. Localized pleural mesothelioma: the clinical spectrum. Chest. 1994;106:1611–1615. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.5.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obers VJ, Leiman G, Girdwood RW, et al. Primary malignant pleural tumors (mesotheliomas) presenting as localized masses: fine needle aspiration cytologic findings, clinical and radiologic features and review of the literature. Acta Cytol. 1988;32:567–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rusch VW, Venkatraman E. The importance of surgical staging in the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:815–825. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(96)70342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huncharek M, Kelsey K, Mark EJ, et al. Treatment and survival in diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma: a study of 83 cases from the Massachusetts General Hospital. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:1265–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falkson G, Alberts AS, Falkson HC, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma treatment: the current state of the art. Cancer Treat Rev. 1988;15:231–242. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(88)90023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alberts AS, Falkson G, Goedhals L, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: a disease unaffected by current therapeutic maneuvers. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:527–535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey JC, Erdman C, Pisch J, et al. Diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma: options in surgical treatment. Compr Ther. 1995;21:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antman KH. Clinical presentation and natural history of benign and malignant mesothelioma. Semin Oncol. 1981;8:313–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey JC, Fleischman EH, Kagan AR, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: a survival study. J Surg Oncol. 1990;45:40–42. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930450109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Law MR, Hodson ME, Tumer-Warwich M. Malignant mesothelioma of the pleura: clinical aspects and symptomatic treatment. Eur J Respir Dis. 1984;65:162–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chailleux E, Dabouis G, Pioche D, et al. Prognostic factors in diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma: a study of 167 patients. Chest. 1988;93:159–162. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruffie P, Feld R, Minkin S, et al. Diffuse malignant mesothelioma of the pleura in Ontario and Quebec: a retrospective study of 332 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1157–1168. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.8.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelstein ML, Abedi MR, Wixon J, et al. Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide 1989–2004: an overview. J Gene Med. 2004;6:597–602. doi: 10.1002/jgm.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smythe WR, Hwang HC, Elshami AA, et al. Treatment of experimental human mesothelioma using adenovirus transfer of the herpes simplex thymidine kinase gene. Ann Surg. 1995;222:78–86. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199507000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang HC, Smythe WR, Elshami AA, et al. Gene therapy using adenovirus carrying the herpes simplex-thymidine kinase gene to treat in vivo models of human malignant mesothelioma and lung cancer. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:7–16. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.1.7598939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber BE, Austin EA, Richards CA, et al. Metabolism of 5-fluorocytosine to 5-fluorouracil in human colorectal tumor cells transduced with the cytosine deaminase gene: significant antitumor effects when only a small percentage of tumor cells express cytosine deaminase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8302–8306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruyns C, Gerard C, Velu T. Cancer escape from immune surveillance: how can it be overcome by gene transfer? Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:1176–1181. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackaman C, Bundell CS, Kinnear BF, et al. IL-2 intratumoral immunotherapy enhances CD8+ T cells that mediate destruction of tumor cells and tumor-associated vasculature: a novel mechanism for IL-2. J Immunol. 2003;171:5051–5063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maeda J, Ueki N, Ohkawa T, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-beta 1)- and beta 2-like activities in malignant pleural effusions caused by malignant mesothelioma or primary lung cancer. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;98:319–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamoto M, Teramoto H, Matsumoto S, et al. K-ras and rho A mutations in malignant pleural effusion. Int J Oncol. 2001;19:971–976. doi: 10.3892/ijo.19.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitamura F, Araki S, Suzuki Y, et al. Assessment of the mutations of p53 suppressor gene and Ha- and Ki-ras oncogenes in malignant mesothelioma in relation to asbestos exposure: a study of 12 American patients. Ind Health. 2002;40:175–181. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.40.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang CT, You L, Lin CY, et al. A comparison analysis of anti-tumor efficacy of adenoviral gene replacement therapy (p14ARF and p16INK4A) in human mesothelioma cells. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao GH, Gallagher R, Shetler J, et al. The NF2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, inhibits cell proliferation and cell cycle progression by repressing cyclin D1 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;25:2384–2394. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2384-2394.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson BW, Musk AW, Lake RA. Malignant mesothelioma. Lancet. 2006;366:397–408. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu ZB, Makhija SK, Lu B, et al. Incorporating the survivin promoter in an infectivity enhanced CRAd-analysis of oncolysis and anti-tumor effects in vitro and in vivo. Int J Oncol. 2006;27:237–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curiel DT, Rancourt C. Conditionally replicative adenoviruses for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;27:67–81. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dmitriev I, Krasnykh V, Miller CR, et al. An adenovirus vector with genetically modified fibers demonstrates expanded tropism via utilization of a coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor-independent cell entry mechanism. J Virol. 1998;72:9706–9713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9706-9713.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takayama K, Reynolds PN, Short JJ, et al. A mosaic adenovirus possessing serotype Ad5 and serotype Ad3 knobs exhibits expanded tropism. Virology. 2003;309:282–293. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu H, Seki T, Dmitriev I, et al. Double modification of adenovirus fiber with RGD and polylysine motifs improves coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor-independent gene transfer efficiency. Human Gene Ther. 2002;13:1647–1653. doi: 10.1089/10430340260201734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glasgow JN, Kremer EJ, Hemminki A, et al. An adenovirus vector with a chimeric fiber derived from canine adenovirus type 2 displays novel tropism. Virology. 2004;324:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SE, Jin RJ, Lee SG, et al. Development of a new plasmid vector with PSA-promoter and enhancer expressing tissue-specificity in prostate carcinoma cell lines. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:417–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huber BE, Richards CA, Krenitsky TA. Retroviral-mediated gene therapy for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: an innovative approach for cancer therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8039–8043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.8039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu ZB, Makhija SK, Lu B, et al. Transcriptional targeting of tumors with a novel tumor-specific survivin promoter. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:256–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu B, Mu Y, Cao C, et al. Survivin as a therapeutic target for radiation sensitization in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2840–2845. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ikeguchi M, Liu J, Kaibara N. Expression of survivin mRNA and protein in gastric cancer cell line (MKN-45) during cisplatin treatment. Apoptosis. 2002;7:23–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1013556727182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto M, Davydova J, Wang M, et al. Infectivity enhanced, cyclooxygenase-2 promoter-based conditionally replicative adenovirus for pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1203–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu ZB, Makhija SK, Lu B, et al. Transcriptional targeting of adenoviral vector through the CXCR4 tumor-specific promoter. Gene Ther. 2004;11:645–648. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elkin M, Cohen I, Zcharia E, et al. Regulation of heparanase gene expression by estrogen in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8821–8826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barker SD, Coolidge CJ, Kanerva A, et al. The secretory leukoprotease inhibitor (SLPI) promoter for ovarian cancer gene therapy. J Gene Med. 2003;5:300–310. doi: 10.1002/jgm.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breidenbach M, Rein DT, Everts M, et al. Mesothelin-mediated targeting of adenoviral vectors for ovarian cancer gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2006;12:187–193. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kazan-Allen L. Asbestos and mesothelioma: worldwide trends. Lung Cancer. 2006;49 (Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vilchez RA, Butel JS. Emergent human pathogen simian virus 40 and its role in cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:495–508. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.3.495-508.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Isik R, Metintas M, Gibbs AR, et al. p53, p21 and metallothionein immunoreactivities in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: correlations with the epidemiological features and prognosis of mesotheliomas with environmental asbestos exposure. Respir Med. 2001;95:588–593. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamasaki L. Role of the RB tumor suppressor in cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2003;115:209–239. doi: 10.1007/0-306-48158-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inase N, Miyake S, Yoshizawa Y, et al. Calretinin promoter for suicide gene expression in malignant mesothelioma. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:1111–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Odaka M, Wiewrodt R, DeLong P, et al. Analysis of the immunologic response generated by Ad. IFN-beta during successful intraperitoneal tumor gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2002;6:210–218. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curiel DT. The development of conditionally replicative adenoviruses for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3395–3399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alemany R, Balague C, Curiel DT. Replicative adenoviruses for cancer therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:723–727. doi: 10.1038/77283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bao R, Connolly DC, Murphy M, et al. Activation of cancer-specific gene expression by the survivin promoter. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:522–528. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van der Eb MM, Cramer SJ, Vergouwe Y, et al. Severe hepatic dysfunction after adenovirus-mediated transfer of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene and ganciclovir administration. Gene Ther. 1998;5:451–458. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Philipson L, Lonberg-Holm K, Pettersson U, et al. Virus-receptor interaction in an adenovirus system. J Virol. 1968;2:1064–1075. doi: 10.1128/jvi.2.10.1064-1075.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bergelson JM, Cunningham JA, Drognett G, et al. Isolation of a common receptor for Coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science. 1997;275:1320–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wickham TJ, Mathias P, Cheresh DA, et al. Integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell. 1993;73:309–319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90231-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Short JJ, Pereboev AV, Kawakami Y, et al. Adenovirus serotype 3 utilizes CD80 (B7.1) and CD86 (B7.2) as cellular attachment receptors. Virology. 2004;322:349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sirena D, Lilienfeld B, Eisenhut M, et al. The human membrane cofactor CD46 is a receptor for species B adenovirus serotype 3. J Virol. 2004;78:4454–4462. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4454-4462.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Monzo M, Rosell R, Felip E, et al. A novel anti-apoptosis gene: Re-expression of survivin messenger RNA as a prognosis marker in non-small-cell lung cancers. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2100–2104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarela AI, Verbeke CS, Ramsdale J, et al. Expression of survivin, a novel inhibitor of apoptosis and cell cycle regulatory protein, in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:886–892. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodel F, Hoffmann J, Grabenbauer GG, et al. High survivin expression is associated with reduced apoptosis in rectal cancer and may predict disease-free survival after preoperative radiochemotherapy and surgical resection. Strahlenther Onkol. 2002;178:426–435. doi: 10.1007/s00066-002-1003-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Das A, Tan WL, Jeo J, et al. Expression of survivin in primary glioblastomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002;128:302–306. doi: 10.1007/s00432-002-0343-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Casado E, Nettelbeck DM, Gomez-Navarro J, et al. Transcriptional targeting for ovarian cancer gene therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:229–237. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]