Summary

The enzyme triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) is a model of catalytic efficiency. The 11-residue loop 6 at the TIM active site plays a major role in this enzymatic prowess. The loop moves between open and closed states, which facilitate substrate access and catalysis, respectively. The N- and C-terminal hinges of loop 6 control this motion. Here, we detail flexibility requirements for hinges in a comparative solution NMR study of wild-type (WT) TIM and a quintuple mutant (PGG/GGG). The latter contained glycine substitutions in the N-terminal hinge at Val167 and Trp168, which follow the essential Pro166, and in the C-terminal hinge at Lys174, Thr175, and Ala176. Previous work demonstrated that PGG/GGG has a 10-fold higher Km value and 103-fold reduced kcat relative to WT with either [D]-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate or dihyrdroxyacetone phosphate as substrate. Our NMR results explain this in terms of altered loop-6 dynamics in PGG/GGG. In the mutant, loop 6 exhibits conformational heterogeneity with corresponding motional rates < 750 s−1 that are an order of magnitude slower than the natural WT loop-6 motion. At the same time, ns-timescale motions of loop 6 are greatly enhanced in the mutant relative to WT. These differences from WT behavior occur in both apo PGG/GGG and in the form bound to the reaction-intermediate analog, 2-phosphoglycolate (2-PGA). In addition, as indicated by 1H, 15N and 13CO chemical-shifts, the glycine substitutions (a) diminished the enzyme’s response to ligand, and (b) induced structural perturbations in apo and 2-PGA-bound forms of TIM that are atypical of those observed in WT. Altogether, these data show that PGG/GGG exists in multiple conformations that are not fully competent for ligand binding or catalysis. These experiments elucidate an important principle of catalytic hinge design in proteins: structural rigidity is essential for focused motional freedom of active-site loops.

Keywords: Enzyme catalysis, Loop motion, Protein hinge, NMR spectroscopy, Protein dynamics, Triosephosphate isomerase

Introduction

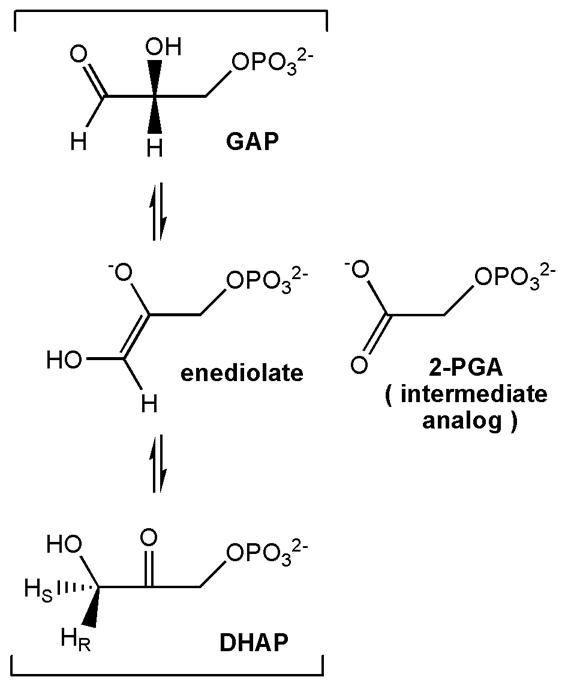

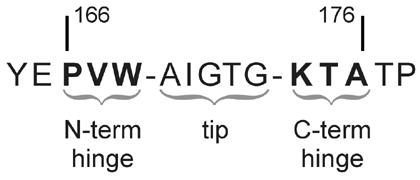

Enzymes make extensive use of conformational changes throughout their catalytic cycle that in many cases are essential to their function. Triosephosphate isomerase (TIM, EC 5.3.1.1) is an important case in which motion plays a significant role in the rate-limiting catalytic step. TIM is a very efficient and faithful catalyst of the interconversion (Scheme 1) between dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP), enabling isomerization near the diffusion-limited rate1 while limiting formation of the toxic side product, methylglyoxal, to only 1 molecule per 105 catalytic cycles.2 A critical aspect of TIM catalysis is the participation of a highly conserved active-site Ω loop, the 11-residue loop 6, which consists of three-residue N- and C-terminal hinges and an intervening five-residue tip (Scheme 2). Ω loops typically reside on the surface of proteins and consist of 6 – 20 amino acids with a short distance (≤ 10 Å) between the N- and C-terminal residues, yielding a resemblance to the Greek letter Ω.3,4

In TIM, loop 6 plays a functional role via its motion between two major conformational states: open and closed (Figure 1). In the open conformation, the substrate has ready access to both the active site and the bulk solvent. The closed conformation is observed in X-ray crystallographic studies in which ligand is bound in the TIM active site. Closure of loop 6 involves an approximately 7 Å movement at its tip (Cα of Thr172). This closed form is stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the amide-NH of loop-6 residue Ala176 and the hydroxyl of Tyr208 within loop 7 (residues 208 – 211) and between the Ala176 carbonyl and the Ser211 hydroxyl.a Notably, loop-6 closure is accompanied by significant structural changes in loop 7 that allows repositioning of the carboxylate of Glu165, which is the catalytic base, into its functionally competent position.5–7 In addition, the central five residues of loop 6 have been shown to be important for preventing unwanted production of methylglyoxal,2 yet the only direct contact of loop 6 with ligand is a single hydrogen bond between the ligand phosphate and the backbone NH of Gly171. This stabilization of an intermediate state and the possible coordination of loop-6 motion with that of loop 7 and Glu165 facilitate the enzymatic reaction, and physically allows passage of the ligand between the active site and solvent. Thus, motion of loop 6 is essential to overall function in TIM.

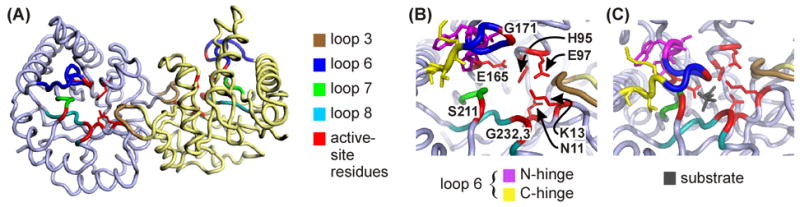

Figure 1.

(A) cTIM dimer (open, 1TIM25) with color coding of selected secondary structure elements. Residues participating in the active site are colored red, and include Asn11, Lys13, His95, Glu97, Glu165, Gly171, Ser211, Gly232 and Gly233. Among these, directly relevant side chains are shown for Asn11, Lys13, His95, Glu97 and Glu165. Active-site coloration trumps colors of other structural elements. (B) Close-up view with labeled active-site residues and additional coloration of N- and C- terminal hinges. (C) Active site in closed, liganded structure (1TPH26). Structural representations here and in Figures 2 and 4 were prepared using PyMOL,57 and PDB coordinates 1TIM25 and 1TPH26 for apo and bound forms of cTIM.

Several lines of evidence support the notion that loop-6 motion is limiting to the reaction rate in the direction of the DHAP to GAP interconversion,1 each placing loop motion on the order of 103–104 s−1 in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) TIM. Computational studies have long suggested that loop 6 moves on this μs timescale with rate-limiting effect.8,9 Solid-state NMR relaxation studies10,11 of 2H-labeled Trp168 and solution-state NMR studies12 of 19F-labeled Trp168 also indicate that loop 6 moves at a rate of 104 s−1 and in a manner that is likely rate-limiting to catalysis. Furthermore, these rates were confirmed by temperature-jump relaxation spectroscopy utilizing Trp168 fluorescence,13 and supported by a study revealing that conformational motion on this timescale enhances 15N spin-relaxation rates within loop 6 and other sites vicinal to it.14,15 In addition, the solid-10 and solution-state14,15 NMR experiments indicate that loop 6 moves in both apo and bound enzyme forms and, therefore, that loop motion is not ligand gated.

The interconversion between opened and closed conformations of loop 6 is a rigid-body motion in which only residues in the N- and C-terminal hinges experience changes in backbone dihedral angles.16,17 Hydrogen bonds involving loop-6 residues are another prominent feature of the open-close motion. Upon closure, the amide NH of Gly171 in the tip of the loop comes within 2.8 Å of the O3 oxygen atom in the substrate phosphate, whereas the NH of Ala176 in the C-terminal hinge forms a critical hydrogen bond with the Tyr208 hydroxyl in loop 7.8,18,19 Upon closure, tight intra-loop hydrogen bonding also occurs between the amides of Ala169 and Ile170 in the loop-6 center and carbonyls of Pro166 and Val167 in the N-terminal hinge respectively. Not surprisingly, all residues in loop 6 are highly conserved in over 130 TIM sequences, as described by Sampson, Wierenga and coworkers,20 and as investigated by genetic,21,22 kinetic23,24 and crystallographic20 means. In the loop-6 center, sequence conservation is driven by a structure that (1) encapsulates the active site during catalysis, (2) facilitates the Gly171 backbone hydrogen bond to substrate and the intra-enzyme hydrogen bonds of Ala169 and Ile170, and (3) positions the Ile170 side chain to shield substrate-enzyme interaction from bulk solvent. In the hinge regions of loop 6, conservation reflects (1) the backbone hydrogen-bonding constraints at Pro166, Val167 and Ala176, and (2) the requirements for functional loop-6 motion.

Packing is a prominent factor for both of the loop-6 hinges, as depicted in Figure 2. Analysis of these interactions provides insight into significant features relevant to their conformational motion. For the first two residues (C1 and C2) of the C-terminal hinge,21 the side chains are loosely positioned and only require compatibility with solvent exposure in both the open and closed conformations. In contrast, the third residue (C3) is selected for important packing interactions in the apo (on-average open) form of the loop. The open conformation requires the C3 side chain to fit into a small hydrophobic pocket or else destabilize the open form, thus blocking access to the active site. This explains the evolutionary preference for alanine at C3. Meanwhile, among the three N-terminal hinge sites (N1 – N3), the PXW sequence is dominant (with 98% X = I/V/L).20 This consensus is likely driven (1) by structural and dynamic constraints on the catalytic Glu165 at position (N1 – 1), and (2) by packing constraints on the N1 and N3 sites, and, to a lesser extent, on N2.22 It has also been noted that the few observed deviations of the N-hinge from PXW retain the N1 proline and are correlated with changes in the otherwise strictly conserved YGGS motif of loop 7.20

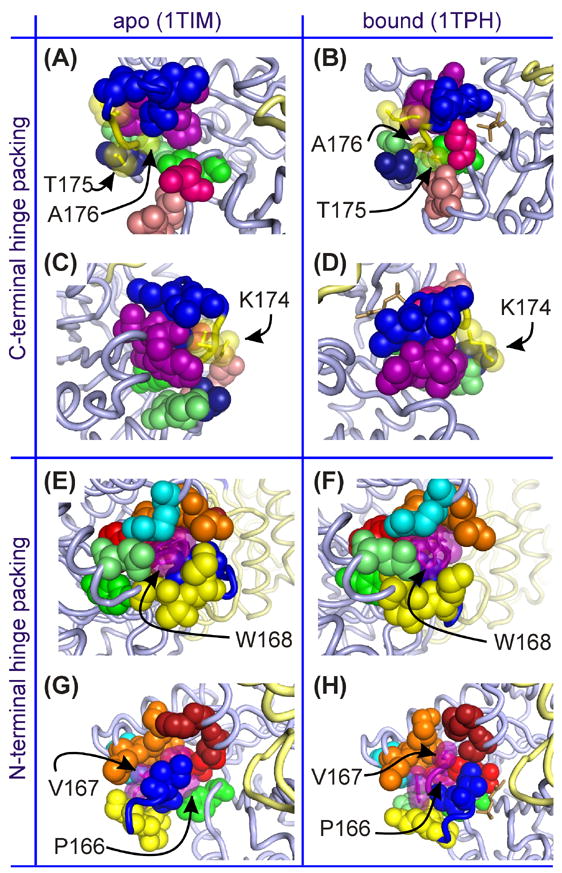

Figure 2.

Various views of the packing of loop-6 hinge side chains for the apo and bound forms of WT chicken TIM. (A)–(D) Packing of the C-terminal hinge (Lys174, Thr175, Ala176), with hinge side chains represented by translucent space-filling yellow spheres, while solid spheres represent atoms of surrounding residues. (E)–(F) Packing of the N-terminal hinge (Pro166, Val167, Trp168), with translucent purple spheres for hinge side chains and solid spheres for surrounding groups. In all parts, blue spheres belong to central residues of loop 6, while purple and yellow (solid or translucent) belong to its N- and C-terminal hinges, respectively. In (A)-(D), light pink are Asn216 and Leu220, hot pink is Ser211, lime green are Gln180 and Ala181, green is Tyr208 and dark blue is Thr177. In (E)-(H), cyan is Arg134, orange are Glu129 - Leu131, lime green is Gln180, green is Tyr208, maroon are Ser96 and His100 and red are Tyr164 and Glu165. In the bound forms (at right) the substrate is shown as in brown stick representation. For all parts, the light gray cartoon backbone is the monomer containing the highlighted loop-6 region, while the second monomer is light yellow.

Sampson and coworkers investigated the requirements for functional hinge sequences in TIM using genetic library approaches.21–23 These studies revealed that some C-hinge sequence variability can be tolerated in the context of catalytic activity, while the amino-acid sequence requirements at the N-terminal hinge are much more stringent. An additional result from these studies was the interdependence of the N- and C-terminal hinge sequences, which results in non-additive effects on catalytic activity. Curiously, these library experiments did not yield a single semi-active mutant (>10% of wild-type activity) with glycine in the N-terminal hinge. Likewise, only 4 of 86 semi-active C-hinge mutants included a glycine substitution (none with multiple glycines). Furthermore, glycine is not observed at any hinge positions in all of the sequenced, naturally occurring TIM enzymes to date. All of this is in spite of the fact that glycine does not conflict with any of the noted factors influencing hinge conservation and design: glycine substitution would not sterically destabilize the open or closed forms of loop 6, nor would it alter the capability for backbone hydrogen bonding at the C3 and N1 and N2 hinge sites. A remaining possibility is that dynamic factors necessitate glycine deselection, namely that, in spite of the motional role of the hinges, proper enzyme function requires that they exhibit a degree of rigidity not provided by the smallest of amino acids, glycine.

To explore this hypothesis, Xiang et al.24 characterized glycine-containing hinge mutants of chicken TIM (cTIM): PGG, with hinge sequences P166/V167G/W168G at the N-terminal hinge, GGG with K174G/T175G/A176G mutations the C-terminal hinge, and PGG/GGG, the combination of the N- and C-hinge mutants. Pro166 was always retained due to the absolute conservation at N1. Biochemical characterization revealed a 200-fold reduction in kcat for the PGG and GGG mutations, and a 2500-fold drop in kcat for PGG/GGG. The substrate Km value for all three mutants was elevated 10-fold relative to wild type (WT), indicating equivalent reductions of affinity for substrate. Additionally, 31P NMR spectroscopy of the reaction intermediate analogue, 2-phosphoglycolate (2-PGA) (Scheme 1) indicated that, when bound to PGG/GGG, the phosphorus moiety experiences a solvent-like environment unlike that observed in WT. In spite of these differences from WT, none of the mutants exhibited an increase in the rate of methylglyoxal production, indicating that loop 6 does not prematurely open (nor fail to close) during catalysis. Furthermore, each mutant exhibits primary deuterium kinetic isotope effects in the DHAP to GAP direction similar to that of WT, suggesting that enolization is partially rate-limiting regardless of mutation.24 Altogether, these data suggest that the decreased enzymatic activity of PGG/GGG is a result of relatively infrequent closure of loop 6 and continued, if diminished, coupling of that motion with rearrangement of the catalytic base into its competent position.

The action of loop 6 appears to require a carefully balanced combination of motional freedom and structural rigidity that demands further study to understand its functional role. Here, we use solution NMR experiments to investigate the dynamics of loop 6 for WT and PGG/GGG cTIM in the apo and 2-PGA-bound forms, which are the on-average opened and closed WT conformations, respectively. These studies illuminate the significant glycine-induced alteration of loop dynamics and provide convincing evidence for conformational heterogeneity and increased configurational entropy in the mutant. Finally, our analysis of biochemical data in the context of these NMR results allows construction of a kinetic model that explains the large drop in PGG/GGG catalytic activity via the presence of additional equilibria that yield multiple non-productive conformations, E* and E#S, of the apo enzyme and enzyme substrate complex, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Evaluation of hinge packing in loop 6

Much of the conservation of amino acid types in loop 6, and particularly at its hinge sites, is due to functional constraints on van der Waals packing, hydrogen bonding, and backbone dynamics. Figure 2 shows the packing interactions of the C- and N- terminal hinge side chains for both open and closed forms of the protein. In the C-terminal hinge,21 sites C1 and C2 must be compatible with solvent exposure in both open and closed conformations. This is depicted in Figure 2(A) – (D) using apo and ligand-bound structures of cTIM (PDB entries 1TIM25 and 1TPH26) with the C-terminal hinge sequence Lys174-Thr175-Ala176. Parts (A) and (B) show how the Thr175 side chain is fully exposed to solvent in the open form and only slightly more packed, but still solvent accessible, in the closed form. There, the Thr175 side chain abuts the Asn216 and Leu220 side chains and the protein backbone at Ser211. Additionally, the Lys174 side chain exhibits similar loose packing and high solvent exposure in both apo and bound forms [Figure 2 (C) and (D)]. However, in both cases, its side chain is in close vicinity to that of Trp168 in the N-terminal hinge, while the Thr172 side chain is nearer Lys174 in the open form than in the closed form. In contrast to the C1 and C2 positions, the packing interactions are significant for the residue at C3 [Figure 2(A) and (B)]. The open form requires its side chain to fit into a compact hydrophobic pocket or else destabilize that form and ultimately alter the open/close equilibrium. The pocket consists of the Pro166 and Trp168 side chains from the N-terminal hinge, as well as the Tyr208 side chain and the protein backbone at Thr177. In the closed form, the pocket less severely encapsulates the Ala176 side chain, in spite of the close closed-form vicinity of backbone and side-chain atoms from Gln180 and Ala181. The consequence at C3 is that the open form cannot accommodate a larger side chain. Evolution has enforced that principle in order to avoid shifting the equilibrium to the more accommodating closed from. However, glycine substitution does not obviously run counter to this design.

For the N-terminal hinge, the PXW sequence consensus is driven in part by structural and dynamic constraints on the adjacent, catalytic Glu165. Packing constraints on the N1 and N3 sites are also significant,22 as depicted in Figure 2(E) – (H) using cTIM structures. There, parts (E) and (F) show the tight fit of the Trp168 side chain within a pocket formed by (1) hydrophobic portions of the Glu129, Leu131, Arg134, Tyr164, Ala169 and Gln180 side chains, (2) C-terminal hinge sites, including the Lys174 side chain and the backbone of Ala176, and (3) the side chains of fellow N-terminal hinge member Pro166. Packing of the Trp168 side chain is significantly less restrictive in the bound form, as shown in Figure 2(F). In the apo form of the enzyme, the side chain of site N1 (Pro166) resides in a very tight pocket formed by side chains of Tyr164, Glu165, Trp168, Ala169, Ala176 and Tyr208, and by the backbone at glycines 209 and 210. In the bound form, this pocket opens with displacement of loop 7 residues Tyr208 through Ser211. However, the newly available space is filled by concurrent closure of loop 6, which repositions Glu165, Ala169 and Ile170, leaving a pocket for Pro166 that is only slightly less restrictive than in the apo form. As noted in the Introduction, the few observed deviations from the PXW N-terminal hinge consensus are always correlated with changes in the otherwise perfectly conserved YGGS motif of loop 7. Interestingly, the N1 proline is retained even in these deviants, while N2 and N3 typically convert to proline and glutamate in spite of their relative separation from loop 7 in both apo and bound cTIM structures. Finally, parts (G) and (H) of Figure 2 show packing of the N2 (Val167 in cTIM) side chain in the pocket formed by Ser96, His100, Lys130 and Glu165 side chains and by the backbone atoms of Glu129 and Lys130. Relative to the other N-hinge sites, this packing is less restrictive in the open form of the enzyme and especially less so in the closed form. This explains the potential of N2 to accommodate larger Ile or Leu residues in place of Val.

It is clear from this analysis that glycine substitution, while obviously easy to accommodate in terms of available space, would provide significant non-natural flexibility in the hinges. Consequent alteration of the evolutionarily optimized intra-protein and protein-substrate interactions may thus be expected. In the following, we detail the biophysical consequences of glycine mutations within the loop-6 hinges. This analysis includes investigation of structural variation evidenced by NMR chemical-shift changes and of dynamic changes probed by NMR spin-relaxation.

Assignment of NMR resonances

Because cTIM is a large protein (53.2 kDa homodimer), TROSY-based triple-resonance NMR experiments27,28 were necessary for assignment of backbone amino-acid sites in WT and PGG/GGG. Resulting levels of assignment for apo and 2-PGA-bound forms of both WT and PGG/GGG cTIM are provided in Table 1. In both forms of the WT protein, we achieved approximately 90% assignment levels for nuclei along the backbone and side chains (1HN, 15NH, 13Cα, 13Cβ, and 13C′). For PGG/GGG cTIM, a somewhat reduced overall assignment level was obtained: about 80 and 75% for the apo and 2-PGA-bound forms. Reasons for these reductions are discussed in Materials and Methods. An exception to the 90% levels in WT cTIM is the 10.5% level for 13Cα resonances in the 2-PGA-bound form. This value reflects only the assignment of 26 of 27 glycines. These were made using an HN(CA)CB experiment, while 13Cα assignment for other amino-acid types requires an HNCA-type experiment. The latter was not performed on the bound WT because it was deemed unnecessary for thorough assignment of our primary target, the amide (1H,15N) shifts. Similarly, carbonyl- and Cβ-targeted triple-resonance spectra were not collected for apo and bound forms, respectively, of PGG/GGG. Thus, no assignments were made for these resonances, again, to little effect on the target (1H,15N) shifts. A selection of assignments in 2D 1H-15N TROSY HSQC of apo and bound forms of WT and PGG/GGG TIM are shown in Figure 3.

Table 1.

Percent assignments for apo and 2-PGA-bound forms of WT and PGG/GGG cTIM.

| WT | PGG/GGG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| site | apo | bound | apo | bound |

| (1H,15N)a | 94 | 91 | 80 | 73 |

| 13Cα | 97 | 11 | 88 | 80 |

| 13Cβ | 85 | 82 | 75 | --- |

| 13C′ | 96 | 88 | --- | 79 |

Backbone amide assignments are given as a percent of 241 non-proline residues in cTIM (WT or PGG/GGG). Other values reflect the full count of 248 amino acids.

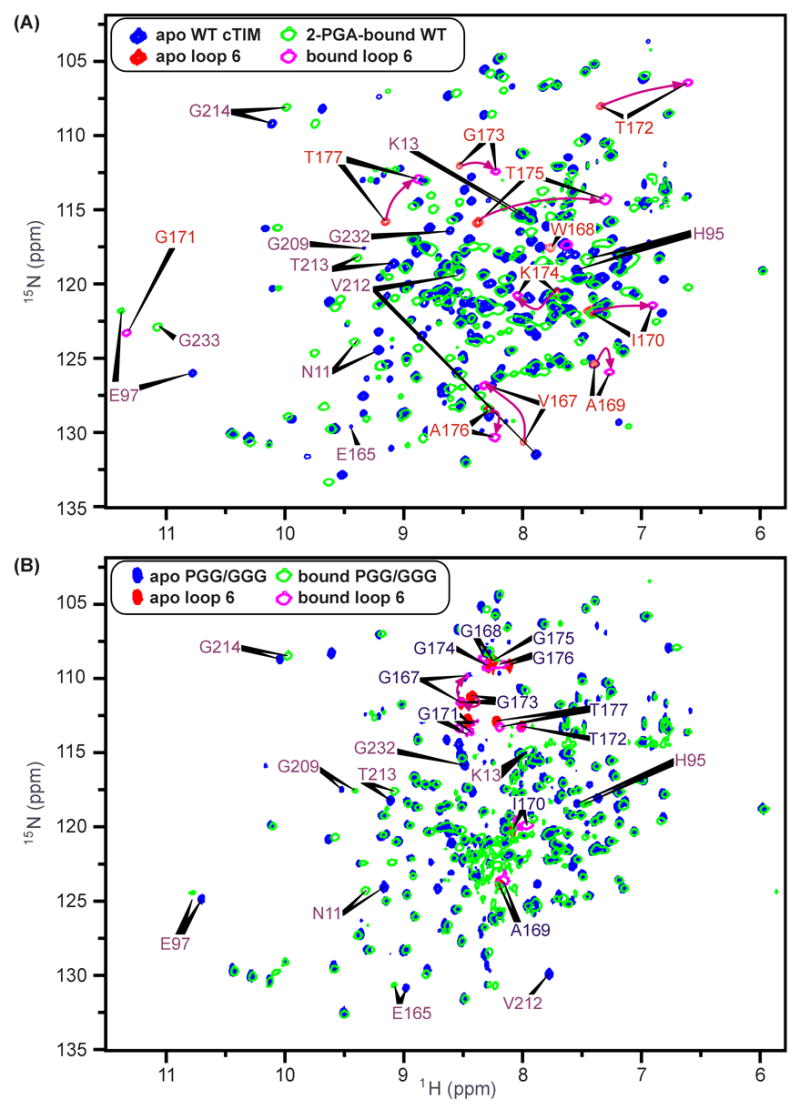

Figure 3.

1H-15N HSQCs of (A) apo WT cTIM (blue, loop-6 sites in red) with overlaid 2-PGA-bound WT spectrum (green, open contours, loop 6 sites in magenta) and (B) apo and 2-PGA-bound PGG/GGG spectra with color and contour schemes as in (A). For WT spectra in (A), purple arrows highlight each loop-6 apo-to-bound chemical-shift trajectory, though within loop 6, apo-form Gly171 and bound-form Trp168 resonances have not been identified. Additional residues indicated include the catalytic residue, Glu165 (not identified in the bound form), and other active-site participants.

NMR chemical-shift responses to binding and glycine mutation

Figure 3(A) and (B) show 1H-15N HSQC spectra of apo WT and PGG/GGG cTIM, each overlaid with their respective 2-PGA-bound spectra. These highlight several binding-induced chemical-shift changes in both WT and the mutant protein, while also showing the general identity between the WT and PGG/GGG spectra. The latter indicates that both forms of the protein have the same general structure, while pinpointing sites of localized differences due to glycine substitutions in the loop-6 hinges. Also of interest are the differential chemical-shift changes in each protein in response to 2-PGA binding. Individual chemical-shift changes for WT and PGG/GGG are depicted in Figure 3(A) and (B), where distinct coloration highlights peaks corresponding to residues within loop 6. Additionally, several peaks with noteworthy binding-induced alterations of chemical shift are marked by indicators of the apo and bound peak positions.

One striking difference between the responses of WT and PGG/GGG to the binding of 2-PGA is that loop-6 and other sites in PGG/GGG typically exhibit small-to-negligible changes in the (1H,15N) shift, whereas large responses are observed in WT. Another difference is that the positions of non-mutated loop-6 peaks are distinct from their WT counterparts. Table 2 compares loop-6 peak positions in apo and bound forms of both WT and PGG/GGG to the values expected for a disordered, “random-coil” polypeptide conformation.29,30 Loop-6 resonances in PGG/GGG are generally nearer their random-coil positions than in WT, as evidenced by their clustering between 7.8 and 8.4 ppm in the 1H dimension of the HSQC spectrum in Figure 3(B). For Gly171, the (1H,15N) differences, ΔδRC, from random-coil shifts are of the same sign as in WT, possibly indicating a moderate retention of WT structure. The same is true of 1H shifts for Ala169, Ile170 and Thr172, and the 15N shift of Gly173. However, the other amide shifts for each of these residues exhibits significant ΔδRC values that are of opposite sign relative to those in WT apo and bound forms. This suggests that the hinge mutations yield non-native structures at all central loop-6 sites other than Gly171.

Table 2.

Deviation (ΔδRC) of amide (1H,15N) chemical shifts from random-coil values for loop-6 (and neighboring) residues that are common to WT and PGG/GGG cTIM.

| residue | random-coil shifta (1H,15N) (ppm) | WT-apo ΔδRC (ppm) | WT-bound ΔδRC (ppm) | PGG/GGG-apo ΔδRC (ppm) | PGG/GGG-bound ΔδRC (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Loop-6 Residues

|

|||||

| A169 | (8.35, 125.04) | (−0.96, 0.4) | (−1.08, 0.9) | (−0.14, −1.2) | (−0.19, −1.4) |

| I170 | (8.17, 120.35) | (−0.74, 1.5) | (−1.27, 1.1) | (−0.08, −0.2) | (−0.20, −0.4) |

| G171 | (8.41, 107.47) | --- | (2.91, 15.8) | (0.05, 5.5) | (0.02, 6.2) |

| T172 | (8.25, 111.96) | (−0.91, −4.0) | (−1.64, −5.5) | (−0.24, 1.3) | (−0.23, 1.4) |

| G173 | (8.41, 107.47) | (0.13, 4.6) | (−0.19, 4.9) | (0.02, 3.7) | (0.12, 4.2) |

| T177 | (8.25, 111.96) | (0.90, 3.9) | (0.62, 0.9) | (−0.02, 1.0) | (−0.05, 1.4) |

|

Active-Site Residues and Loop-7 Neighbors

|

|||||

| H95 | (8.56, 118.09) | (−1.01, 0.99) | (−1.10, 0.1) | (−1.01, 0.4) | (−1.06, 0.4) |

| E97 | (8.40, 120.23) | (2.38, 5.8) | (2.97, 1.5) | (2.31, 4.7) | (2.38, 4.7) |

| E165 | (8.40, 120.23) | (1.04, 9.4) | --- | (0.59, 10.7) | (0.69, 10.5) |

| V212 | (8.16, 119.31) | (−0.28, 12.2) | (0.38, 0.0) | (−0.38, 10.7) | --- |

| T213 | (8.25, 111.96) | (0.83, 6.7) | (1.14, 6.3) | (0.87, 6.3) | (0.84, 5.7) |

| G214 | (8.41, 107.47) | (1.70, 1.7) | (1.57, 0.6) | (1.64, 1.2) | (1.57, 1.1) |

RC shifts of Schwarzinger, et al.29,30 from BioMagResBank (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu).

The N- and C- terminal glycine hinges of PGG/GGG also have random-coil-like chemical shifts. Gly168 and Gly174 – Gly176 have clustered (1H,15N) shifts that differ from random-coil values by a nearly uniform ~(−0.15, 1.5) ppm in both apo and bound forms. In contrast, Gly167 exhibits larger ΔδRC in both apo and bound forms, (0.11, 4.2) and (0.07, 2.4) ppm, respectively, along with a significant response to binding. This exception among the five substituted glycines is explicable due to the adjacency of Gly167 to the retained and well-packed Pro166. That Gly167 shifts are responsive to ligand binding may indicate that the N-terminal hinge maintains some functional capacity in PGG/GGG. The structure of the WT hinges is clearly more well-defined, with generally large apo and bound (3 – 11 ppm for 15N) ΔδRC values. The exception is Lys174, which, as shown in Figure 2(C) and (D), is the most loosely packed hinge site.

A distinct effect of the glycine mutations is apparent from analysis of selected active-site residues and (Val212 – Gly214), which neighbor loop 7, for which direct chemical-shift data is unavailable. Each of the residues in these sets exhibits a sizeable binding-induced shift change in the WT protein, but null-to-small changes in PGG/GGG. A possible exception is Val212, which disappears on binding in the mutant. Differences from random-coil shifts for these sites are shown in Table 2. Unlike loop 6, these mutations do not convert any residue in this active-site group to a random-coil-like conformation. This might be expected as a result of the more subtle interaction of these residues with the mutation sites and the loop-6 center. Nonetheless, the active-site residues clearly do suffer from the sub-optimal structure and dynamics of loop 6. Residues His95, Glu97, Val212, Thr213 and Gly214 each have apo-form amide shifts in PGG/GGG that are very close to the apo WT values. However, in the bound form, the PGG/GGG shifts fall between the apo and bound WT values. This likely indicates that they exist in a reduced-competency conformation(s) between those associated with the open and closed forms of loop 6. Thus we characterize the mutation-induced perturbation to these sites as being on the catalytic pathway, i.e., these conformations are intermediate between open/closed based on the direction of ligand-induced chemical- shift changes. Similarly, the catalytic residue, Glu165, exhibits the apo-form WT shift in both apo and bound forms of PGG/GGG, whereas its NMR resonance is absent or unassigned in 2-PGA-bound WT. The latter observation likely indicates that the natural response is a large chemical-shift change at Glu165, which is not seen with PGG/GGG. Because mutant enzyme does retain slight activity, the small amide shift changes observed among these active-site participants in PGG/GGG is likely due to an unfavorable shift of the equilibrium between the open and catalytically competent states of cTIM.

Quantification of binding-induced (1H,15N) chemical-shift variation

A broader quantitative view of intra-protein environmental changes upon 2-PGA binding is available from structural maps of amide 1H-15N chemical-shift differences between apo and bound forms of both WT and PGG/GGG. These are based on the 1H-15N HSQC spectra shown in Figure 3. Chemical-shift changes at the ith residue were quantified with a single, weighted average,

| (1) |

as suggested by Grzesiek, et al.,31 in which ΔδHN, i and ΔδN, i are the changes in 1H and 15N chemical shifts, δHN, i and δN, i at the ith residue. Figure 1 provides structural reference to the maps of ΔNH provided in Figure 4. The former displays cTIM with the same viewpoint, but without ΔNH information and with highlight to structural elements of particular interest in this analysis, including residues participating in the active site [Figure 1(B) and (C)].

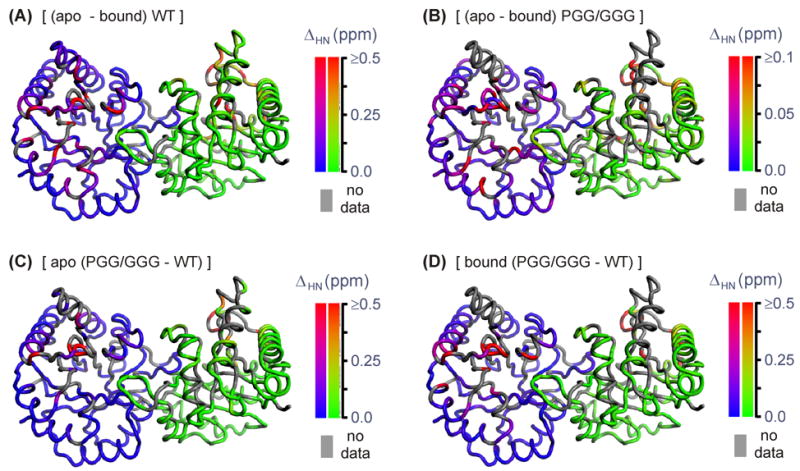

Figure 4.

False-color representations of (1H,15N) chemical-shift differences mapped onto the cTIM dimer. (A) ΔHN WT (apo – 2-PGA-bound), (B) ΔHN PGG/GGG (apo – 2-PGA-bound), (C) ΔδHN (apo PGG/GGG – apo WT), and (D) ΔHN (bound PGG/GGG – bound WT). Gray coloration indicates a residue unassigned in one or both of the compared forms. To facilitate comparison, apo-cTIM coordinates (1TIM25) were used in (A) –(D), regardless of binding state or mutation. Note, the scale in (B) is 5 times smaller than in (A), (C), or (D).

As shown in Figure 4(A), 2-PGA binding to the WT enzyme yields significant ΔNH only at sites within or near the active site, including in loop 6. Negligible changes are observed at structurally distant sites on the monomer face that is opposite loop 6 and the active site. This is conveniently seen in the dimeric views of Figure 4, in which each monomer displays an opposite face. The absence of distal chemical-shift responses is consistent with X-ray crystallographic data, which similarly localizes major binding-induced conformational changes in TIM.5–7 For the WT protein, the averages of (1H,15N) chemical-shift changes among loop-6 and active-site residues are 0.37 ppm (rmsd = 0.22, n = 7) and 0.26 ppm (rmsd = 0.28, n = 4), where rmsd values reflect the distribution within each n-element set. The protein-wide average excluding these residues is 0.074 ppm (rmsd = 0.096, n = 203). For the PGG/GGG mutant, the pattern of 2-PGA-induced chemical-shift changes [Figure 4(B)] is similar to that in WT. However, the magnitude of the scale defining the coloration scheme for PGG/GGG is a factor of 5 smaller than that used for WT, indicating PGG/GGG’s damped response to ligand binding. In some regions of Figure 4(B), this gives the false appearance of a larger PGG/GGG response, such as in loop 3, which intercalates its twin monomer near the active site and which actually exhibits ~3× reduction in average ΔNH relative to WT. PGG/GGG’s generally reduced structural response to binding is quantified by averages among loop-6 and active-site residues of 0.074 ppm (rmsd = 0.069, n = 10) and 0.070 ppm (rmsd = 0.032, n = 6), along with the exclusive protein-wide average of 0.022 ppm (rmsd = 0.028, n = 160).

Quantification of mutation-induced (1H,15N) chemical-shift variation

We extended this analysis to directly explore differences between WT and PGG/GGG chemical shifts. Mutation-induced 1H-15N chemical-shift changes are mapped to the cTIM structure for ΔHN (apo PGG/GGG – apo wt) and ΔHN (bound PGG/GGG – bound wt) in Figure 4(C) and (D). For the apo forms, significant ΔHN occurs within loop 6, the active site and surrounding residues with a distribution of magnitudes comparable to the binding-induced ΔHN values in WT. The apo-form mutation-induced averages for loop-6 and active-site residues are 0.54 ppm (rmsd = 0.26, n = 4) and 0.14 ppm (rmsd = 0.11, n = 6), and the exclusive protein-wide average is 0.064 ppm (rmsd = 0.067, n = 172). These values suggest that the PGG/GGG mutations yield a similar degree of structural perturbation in apo cTIM as 2-PGA binding does in the WT enzyme. Similarly, the mutation-induced ΔHN observed in 2-PGA-bound cTIM has a distribution and intensity that mimics the WT binding-induced result, with loop-6, active-site and exclusive protein-wide averages of 1.11 ppm (rmsd = 0.76, n = 5), 0.66 ppm (rmsd = 0.92, n = 5) and 0.077 ppm (rmsd = 0.074, n = 159).

These chemical-shift responses suggest that loop 6 and active site residues in both the apo and bound forms of PGG/GGG do not adopt the optimal structures of the WT enzyme. Because (a) the open form influences substrate binding and release, and (b) the closed form is activated for catalysis, the implied patterns of mutation-induced structural changes within both apo and bound PGG/GGG are consistent with its sub-optimal Km and kcat. Finally, we note that the average mutation-induced responses within loop 6 of apo- or bound-form PGG/GGG are significantly larger than the WT binding-induced change. The converse is true among active-site residues. The changes in loop 6 in excess of the natural WT response to binding indicate that the mutation-induced perturbations yield structural conformations of loop 6 that are outside of the normal range of states accessed in the WT enzyme. This off-pathway characterization of the loop-6 response is consistent with our noted observation of an unnatural, random-coil like structure among loop-6 residues.

Binding- and mutation-induced 13C′ chemical-shift variation

Structural changes in cTIM were also probed by variation in 13C′ chemical shifts obtained from HNCO and HN(CA)CO spectra. Importantly, this data set includes information on loop-7 residues Tyr208 and Ser211, which are absent in the (1H,15N) study due to incomplete assignment, but which are available here via the (i–1) resonances of Gly209 and Val212. Similarly, the Pro166 response is uniquely probed by the 13C′ (i–1) resonance of residue 167. The changes, ΔδC′WT (apo – bound), observed upon 2-PGA binding to WT (data not shown) appear in a pattern very similar to that observed with their amide counterparts. Ser211 exhibits the largest response in the WT protein, with ΔδC′WT = 5.16 ppm well above the exclusive protein-wide average of absolute responses, (rmsd = 0.34, n = 202, with loops 6, 7 and the active site omitted). The values for Tyr208 (ΔδC′WT = 1.26 ppm) and loop-7 neighbor Val212 (−1.33 ppm) also differ significantly from the average response. These changes are consistent with the known large structural perturbation of loop 7 that is concurrent with binding or loop-6 closure. Ser211 is the most extreme case, with (φ,ψ) angles of (−80°, 120°) in the open form changing to (65°, 30°) when loop 6 is closed.32 Averages of |ΔδC′WT| for loop 6 (2.0 ppm, rmsd = 1.7, n = 10) and active-site (1.1 ppm, rmsd = 1.8, n = 6) residues are also significantly higher than the overall average.

For PGG/GGG, 13C′ shifts were collected on the 2-PGA-bound form. We used these to explore mutation-induced structural changes evidenced by ΔδC′bound (PGG/GGG – WT). Here, the exclusive protein-wide average was (rmsd = 0.35, n = 167), while loop-6 and active-site averages were 1.5 ppm (rmsd = 1.3, n = 6) and 1.3 ppm (rmsd = 1.8, n = 4). Concerning loop 7, data was available for Tyr208 (ΔδC′bound = 0.77 ppm) and loop-7 neighbor Val212 (ΔδC′bound = −1.10 ppm), revealing changes of the same sign, but reduced magnitude compared to ΔδC′WT of binding. This suggests that, in bound PGG/GGG, Tyr208 and Val212 undergo a partial reversion to an apo-like conformation of the WT enzyme. Thus, the loop-7 response to mutation appears to be on the catalytic pathway. A similar result is apparent for the residues with the largest mutation-induced changes, including Pro166, Gly173 and Gln179 with ΔδC′bound = −1.91, −4.07, and 3.08 ppm, all diminished responses relative to the binding-induced changes ΔδC′WT = −4.26, −4.73, and 3.55 ppm. Indeed, the protein-wide pattern of mutation-induced changes (data not shown) suggests the same result: that the difference of bound PGG/GGG from bound WT is similar to that of apo WT from 2-PGA-bound WT.

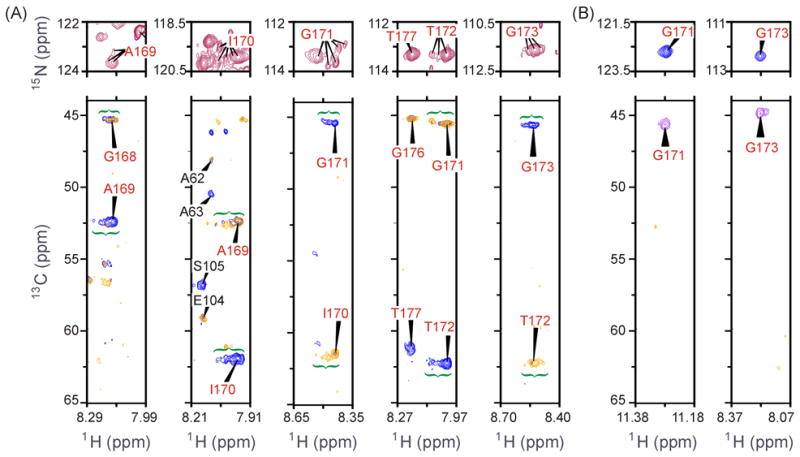

Spectral evidence of loop-6 conformational heterogeneity in PGG/GGG

The above chemical-shift analyses demonstrated the random-coil-like character of several loop-6 residues in PGG/GGG and the failure of the active site and nearby residues to attain a closed-loop conformation upon ligand binding. An explicit view of counterproductive structural heterogeneity within PGG/GGG’s loop 6 is given in Figure 5. In part (A), (1H,15N) HSQC and HNCA-type spectra are shown with individual-residue focus for the 2-PGA-bound form of PGG/GGG. In the HSQCs, each of the central loop-6 residues in PGG/GGG exhibits resonance multiplicity. Identities of individual resonances are confirmed and the conformational heterogeneity emphasized by the accompanying (1H,13C) slices through triple-resonance HNCA and HN(CO)CA spectra. Within the loop center, Ile170 and Gly171 are particularly striking for the large number of resonance positions confirmed for each. Among the mutated glycine hinge residues, such proof of conformational heterogeneity is difficult due to their close (1H,15N,13Cα) spectral vicinity. From the theory of slow exchange in NMR,33 we know that loop 6 residues with multiple peaks move relative to surrounding structural elements (or the ligand) with rates that are slower [< 750 s−1] than their typical spread of peak intensity, Δω ~ (2π × 120 Hz). A resulting hypothesis is that this slow exchange occurs among non-productive conformations.

Figure 5.

(A) 2-PGA-bound PGG/GGG mutant spectra of loop-6 residues: (top) 1H-15N HSQC and (bottom) 1HN-13C HNCA spectral slices (blue) with HN(CO)CA slice overlay (gold), both at fixed 15N. Conformational heterogeneity is evidenced by multiple HSQC peaks per residue, assigned by the corresponding distribution of intensity in triple-resonance spectra. Gly171 and Ile170 show particularly striking heterogeneity, while Thr177, the +1 residue of the C-terminal hinge, is apparently uniform. Fixed 15N shifts for HNCA slices are at 123.4 ppm (Ala169), 119.7 ppm (Ile170), 113.4 ppm (Gly171), 113.0 ppm (Thr172, Thr177) and 111.2 ppm (Gly173). Not all resonances associated with a given site appear in the 1H-13C strips at discrete 15N chemical shift. In (1H,15N) HSQCs, resonances from sites outside of loop 6 are not labeled. (B) 2-PGA-bound wt cTIM spectra loop-6 glycine residues: (top) (1H,15N) HSQC and (bottom) (1HN,13C) HN(CA)CB spectral slices at fixed 15N. Only an HN(CA)CB spectrum was collected for the bound WT, thus only glycines, which reveal their Cα resonance in this Cβ-directed experiment, are shown to simplify comparison with (A). Fixed 15N shifts for HN(CA)CB slices are at 122.9 ppm (Gly171) and 112.1 ppm (Gly173).

This heterogeneity in PGG/GGG is unlike anything observed in 2-PGA-bound WT, where, for contrasting example, an unusually high degree of Ile170 order has been noted in a previous crystallographic study.7 Figure 5(B) shows the HSQC and triple-resonance spectra of WT loop-6 residues Gly171 and Gly173. Neither residue in WT exhibits intensity distributions like those in PGG/GGG. Similarly, the remaining WT loop-6 residues reveal a single resonance in the HSQC and triple-resonance spectra (data not shown). This is consistent with well-defined endpoint structures in the open/close equilibrium of loop 6.

Backbone spin-relaxation NMR

Protein-wide averages of the longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) 15N spin-relaxation rates and the steady state (1H,15N) nuclear Overhauser effect (ssNOE) are presented in Table 3. The reported data were obtained at T = 20 °C and both 14.1 and 18.8 T for the apo and 2-PGA-bound forms of both WT and PGG/GGG cTIM. Each value presented in Table 3 is the mean of the data set trimmed of the highest and lowest 5% of individual-residue values, leaving 163 values contributing in the R1, R2, ssNOE and (R2/R1) sets for the apo WT protein at both 14.1 and 18.8 T. This number is less than the total of assigned resonances, as we excluded sites in overlapping peaks or those resonances with a very poor signal-to-noise ratio (S/N). As described in Materials and Methods, the 99% 2H level in samples used for relaxation experiments decreases the S/N of some peaks in spite of sufficient S/N to assign them from triple-resonance spectra on 70% 2H samples. For bound WT, 194 sites contributed to the averages at both fields, while we used 171 and 154 sites for apo and bound PGG/GGG.

Table 3.

Trimmed means of 15N R1 and R2 and the (1H,15N) ssNOE, excluding the lowest and highest 5% of values. Distribution widths are reflected by the rmsd from the trimmed mean in parentheses. Subscripted digits are the first non-significant digit.

| 14.1 T (600 MHz 1H frequency)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT-apo | WT-bound | PGG/GGG-apo | PGG/GGG-bound | |

|

|

||||

| 0.399 (0.034) | 0.412 (0.033) | 0.443 (0.082) | 0.426 (0.069) | |

| 41.4 (3.6) | 40.8 (3.3) | 40.4 (4.5) | 39.0 (5.0) | |

| 0.802 (0.079) | 0.817 (0.075) | 0.78 (0.12) | 0.80 (0.15) | |

| 105.5 (16.2) | 100.0 (14.6) | 95.0 (19.9) | 94.6 (20.8) | |

| τm (ns)(a) | 33.2 (2.6) | 32.3 (2.4) | 31.5 (3.3) | 31.4 (3.5) |

| 18.8 T (800 MHz 1H frequency)

|

||||

| 0.281 (0.026) | 0.346 (0.032) | 0.332 (0.060) | --- | |

| 52.2 (4.7) | 52.2 (4.7) | 47.0 (5.1) | --- | |

| 0.787 (0.078) | 0.876 (0.051) | 0.77 (0.12) | --- | |

| 189.0 (30.5) | 152.0 (21.4) | 147.9 (31.6) | --- | |

| τm (ns)(a) | 33.4 (2.7) | 30.8 (2.1) | 29.5 (3.2) | --- |

Values of τm, the correlation time for global molecular tumbling were calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

The ssNOE averages for all forms of the protein are ~0.8, indicating a stable well-structured protein. These are less than the 14.1 and 18.8 T averages of 0.91 and 0.93, respectively, calculated for both apo and bound forms of cTIM using the program HydroNMR,34,35 as described in Materials and Methods. The lower observed average ssNOEs indicate significant local NH bond-vector motion on the ps – ns timescale throughout both WT and PGG/GGG proteins. Such motions are not accounted for in the calculation. We further used HydroNMR to calculate individual-residue R1 and R2 values, from which we obtained (rmsd = 18.6) and 206.9 (rmsd = 33.2) for the apo WT protein at 14.1 and 18.8 T, and (rmsd = 8.8) and 204.8 (rmsd = 33.5) for 2-PGA-bound WT at 14.1 and 18.8 T. Noted rmsd values reflect the wide variation in R1 and R2 values due to individual orientations of the NH bond vector. The consistency of these predictions with the measured values reported in Table 3 supports the accuracy of our spin-relaxation data.

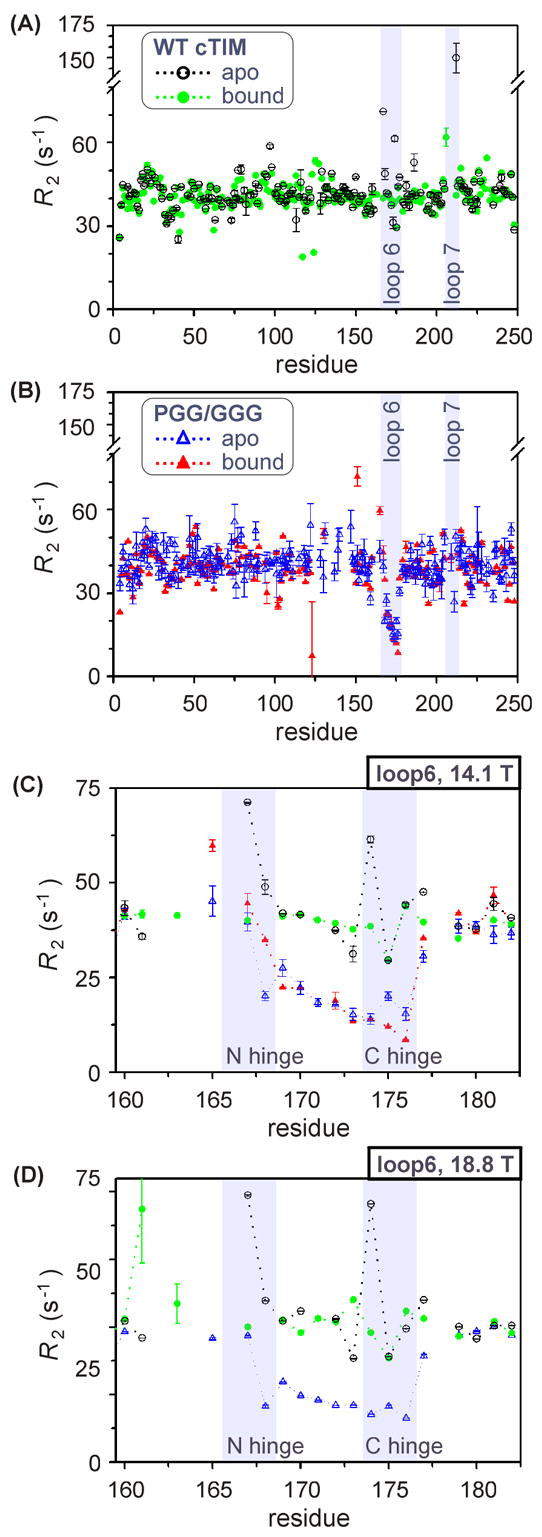

Dynamics on μs-ms timescale from R2

Residue-specific values of R2 for apo and bound forms of cTIM are shown in Figure 6(A) and (B) for WT and PGG/GGG, respectively, at 14.1 T. Data sets collected at 18.8 T (not shown) are consistent with these results. In WT, elevated values within loop 6 and in residues neighboring loop 7 indicate sensitivity to the μs – ms conformational motion of these loops. The absence of data on loop-7 residues Tyr208 – Ser211 is probably due to signal loss brought on by their conformational motions. In the apo form of WT cTIM adjacent to loop 7, the residue Val212 exhibits particularly large R2apo = (150 ± 11) s−1, while its 2-PGA-bound-form value, R22PGA = (41.02 ± 0.02) s−1 matches the protein-wide average in Table 3. In addition to the possible effects of its adjacency to the large (φ,ψ) change at Ser211, the Val212 amide NH also senses the motion via chemical-shift changes expected from its exchange between open- and closed-form hydrogen bonds with Oγ of Ser211 and the carbonyl of Gly210, respectively. At the other end of loop 7, Ile206 has elevated R22PGA = (62 ± 3) s−1, but no data in the apo form. In PGG/GGG, more data is available on loop-7 sites, including R2apo = (51 ± 3), (27 ± 4) and (43 ± 4) s−1 for Val212, Ser211, and Gly209, and R22PGA = (43 ± 2) s−1 for Gly209. Remarkably, these values are only significantly elevated at Val212 in the apo form of PGG/GGG and that by not nearly so much as the WT result. This indicates that loop 7 of PGG/GGG either lacks the μs – ms timescale motions that are vital to natural catalytic function, or that such motions exist without the naturally corresponding structural changes that would otherwise yield measurable Δω and, in turn, elevated R2. This alteration of loop-7 behavior by mutation of loop 6 supports the existence of cooperativity predicted to occur between these elements.5–8,18,19

Figure 6.

R2 values by residue at 14.1 T for (A) WT cTIM in apo and 2-PGA-bound forms, (B) apo and bound PGG/GGG cTIM, and (C) in and adjacent to loop 6 for apo and bound WT and PGG/GGG. (D) is as (C), but at 18.8 T and lacking bound-form PGG/GGG. Shaded areas are provided to highlight labeled elements.

Transverse relaxation in loop 6 provides still more distinction between PGG/GGG and WT enzymes, while also yielding a more complete set for comparative analysis than with loop 7. Figure 6(C) highlights apo and bound R2 variation within loop 6 for both WT and mutant. In WT, elevated R2apo values appear in both hinges: Val167, Trp168 and Lys174 at (71.2 ± 0.1), (49 ± 2) and (61 ± 1) s−1 and in Thr177 at (47.5 ± 0.1) s−1, consistent with previous observations in WT yeast TIM.14,15 However, each of these enhanced rates returns to the protein-wide average upon binding to the 2-PGA intermediate-state analog. A possible exception is Trp168, which is unassigned in the bound form. Also in the WT, Gly173 and Thr175 exhibit depressed R2apo and R22PGA values of ~30 s−1, which can be attributed to decreased sensitivity to the open-to-close exchange process (ΔωN ~ 0) among these sites. Results at 18.8 T are shown in Figure 6(D) and reveal the same pattern.

Meanwhile, in PGG/GGG, no elevated loop-6 R2 values are observed in apo or 2-PGA forms, suggesting the absence of μs – ms motion at these sites. We confirmed this result using (1) TROSY-based Rex14 and rcCPMG36 experiments, where Rex is the contribution to transverse spin relaxation due to μs – ms conformational exchange, and (2) the TROSY (R1ρ – R1) experiment,37 which is sensitive to somewhat faster motions (up to 50,000 s−1). Beyond this absence of elevated transverse relaxation rates, the PGG/GGG loop-6 averages of R2apo and R22PGA of 21.0 and 21.2 s−1 (rmsd = 7.6 and 11.7) are substantially lower than the protein-wide averages of ~40 s−1 (Table 3), as well as the WT loop-6 averages of 45.2 and 39.0 s−1 (rmsd = 13.6 and 3.9). This large depression of rate constants is consistent with a highly mobile loop 6, in which the distribution of motion is shifted from the zero and low-frequency (~1,000 – 10,000 s−1) motions that would drive transverse relaxation and towards the ps – ns timescale, where R1 and the ssNOE measurements are sensitive. The altered timescale of loop-6 motion is expected to be detrimental to catalysis due to the critical coordination of loop 6 and 7 motions near the catalytic rate of ~103 s−1. Meanwhile, the additional configurational entropy anticipated from motions on faster timescales reflects the reduced likelihoods that free or ligand bound PGG/GGG populate functional conformational states.

Finally, we consider another interesting aspect of the spin-relaxation observed in the WT protein. The elevated R2apo values we measured within and about the loop 6 hinges at Val167, Trp168 and Lys174 and Thr177 reproduce the exact pattern observed in an earlier study of WT yeast TIM by Wang, et al.14,15 A difference is that the yeast protein used in that study was bound by the substrate analog glycerol 3-phosphate (G3P). In our work, with the intermediate analog 2-PGA as the WT cTIM binding partner, the pattern of elevated rates vanished. This suggests a ligand-gated alteration of the loop-6 open-close equilibrium that differs with G3P as the substrate analog used in previous work and with 2-PGA as intermediate analog used here. However, McDermott and co-workers demonstrated that the occurrence of loop-6 motion is not ligand gated, as similar timescale motion was apparent from 2H spin relaxation at Trp168 in the apo, G3P-bound and 2-PGA-bound forms of yeast TIM.10 Nonetheless, the differential in R2apo and R22PGA observed here indicates subtle changes in the open-close equilibrium that are specific to the type of bound ligand. These results may indicate that TIM alters the loop-6 equilibrium as the ES complex moves along the reaction coordinate towards the transition state, as with 2-PGA relative to G3P. For example, preferential stabilization of the closed-loop form by 2-PGA might facilitate completion of catalysis without escape and subsequent conversion of the activated substrate to methylglyoxal.

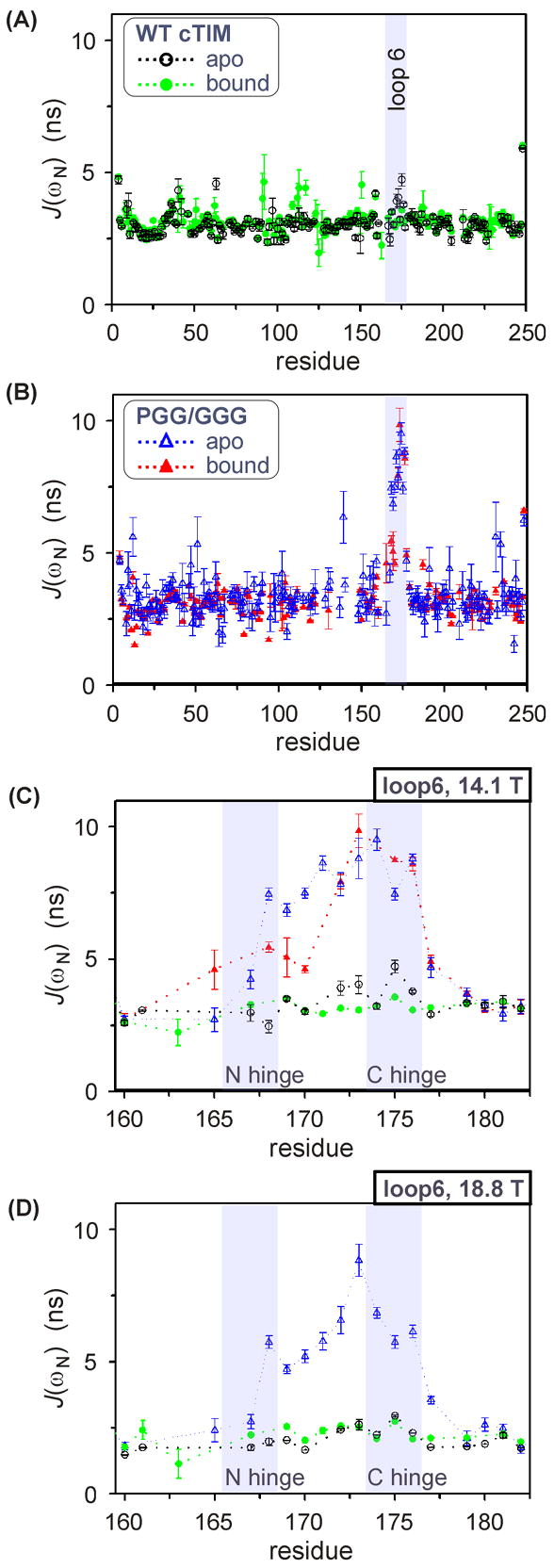

Dynamics on ns timescale from R1, the ssNOE and J(ωN)

In PGG/GGG, the large reductions of R2 within loop 6 suggest not only an absence of critical μs – ms dynamics, but also an increase in ps – ns motions. Characterization of the latter can illuminate additional effects that are detrimental to catalysis. We have assessed ns dynamics in apo and 2-PGA-bound forms of WT and PGG/GGG cTIM using reduced spectral density mapping with 15N R1 and the 1H-15N ssNOE.38 These are sensitive to motions with correlation times near the sums and differences of the 1H and 15N Larmor frequencies, ωH and ωN, and may be used to calculate J(ωN), the spectral density of motion at (ωN/2π)−1 ~ 16.4 ns or 12.3 ns for fields of 14.1 or 18.8 T. The reduced spectral-density calculation that yields J(ωN) from R1 and the ssNOE is described in Materials and Methods. Spectral densities at 14.1 T are plotted vs the amino-acid residues of apo and 2-PGA-bound WT and PGG/GGG cTIM in Figure 7(A) and (B). The overall response was assessed via average J(ωN) values for these sets. Excluding loop-6 residues and Thr177 next to the C-hinge, the apo and bound forms of WT cTIM exhibit (rmsd = 0.24, n = 153) and 3.09 ns (rmsd = 0.25, n = 182), where data were trimmed of the lowest and highest 5%. For apo and bound PGG/GGG, we found (rmsd = 0.43, n = 153) and 3.06 ns (rmsd = 0.33, n = 143). Thus, WT exhibits an overall average +3.7% change in J(ωN) upon binding, while PGG/GGG has a −5.3% difference.

Figure 7.

J(ωN) values by residue at 14.1 T for (A) WT cTIM in apo and 2-PGA-bound forms, (B) apo and bound PGG/GGG cTIM, and (C) in and adjacent to loop 6 for apo and bound WT and PGG/GGG. (D) is as (C), but at 18.8 T and lacking bound-form PGG/GGG. Shaded areas are provided to highlight labeled elements.

To evaluate local ns-scale behavior, we begin with analysis of active-site residues exclusive of loop 6. Among these, only a few provide sufficiently good data in the apo and bound forms to analyze the effect of 2-PGA binding. In WT, His95, Lys13 and Asn11 yielded (bound – apo) ΔJ(ωN)bind = (0.2 ± 0.1), (0.2 ± 0.1) and (0.1 ± 0.2) ns, indicating increased disorder upon binding, while Glu97 showed increased order with ΔJ(ωN)bind = (−0.6 ± 0.5) ns. In spite of the noted significant uncertainties in these values, the pattern in the former group contrasts with the notion of active-site rigidification upon ligand binding39,40 However, while backbone disorder may be a reliable measure of protein-wide behavior, one must be careful to draw conclusions on individual-residue behaviors without also characterizing side chain dynamics. This is a particular concern for these active-site residues, all of which form new side-chain hydrogen bonds upon 2-PGA binding. For His95, Lys13 and Asn11, the new interactions are with the substrate, while Glu97 forms intra-protein hydrogen bonds with both its side chain and its amide NH. The latter likely accounts for Glu97’s uniquely negative ΔJ(ωN)bind.

Evaluation of the active-site group for PGG/GGG revealed ΔJ(ωN)bind at His95, Lys13 and Asn11 of (0.8 ± 0.7), (−1.2 ± 0.3) and (−0.7 ± 0.3) ns. Given the uncertainty, the His95 response must be considered similar to WT, while Lys13 and Asn11 clearly oppose WT behavior. Glu97 data was unavailable for the 2-PGA bound-form of PGG/GGG due to poor S/N. However, PGG/GGG data was available on the catalytic residue, Glu165, where ΔJ(ωN)bind = (1.9 ± 0.9) indicates increased motion at this site and reflecting increased disorder that is likely detrimental to enzymatic function. Again, the side-chain response is needed for the complete story at these sites in PGG/GGG. It is clear, however, that ns-scale dynamics of PGG/GGG active-site residues diverge from the evolutionary optimum represented by the WT enzyme.

The most striking differences between WT and PGG/GGG ns motions are within loop 6. Expanded views of J(ωN) for loop 6 and surrounding residues are provided for all forms of the protein in Figure 7(C). There, loop 6 exhibits large J(ωN) increases relative to the protein-wide average in both apo and bound forms of PGG/GGG, while the WT loop 6 shows relatively slight changes. The general patterns are reproduced at 18.8 T in Figure 7(D). In WT, only apo-form sites Thr172 and Gly173 from the loop center, and Lys174 and Thr175 in the C-terminal hinge have J(ωN) significantly elevated above the protein-wide average, with the largest deviation of +1.72 ns at Thr175. One WT site, Trp168 is 0.52 ns below the average in apo form and unassigned in the bound WT. The low apo-form value for Trp168 is consistent with the restrictive packing at this site. Meanwhile, all loop-6 residues of PGG/GGG exhibit J(ωN) differing from that protein’s averages by no less than +1.0 ns. The apo and bound averages for PGG/GGG, (rmsd = 1.59, n = 9) and 6.90 ns (rmsd = 1.96, n = 8), are +4.21 and +3.84 ns greater than average PGG/GGG behavior and well above the apo and bound WT results, (rmsd = 0.64, n = 10) and 3.20 ns (rmsd = 0.19, n = 10). On average, both the WT and the PGG/GGG loop 6 rigidify somewhat upon 2-PGA binding, but the still-large ns-scale disorder in the bound-form PGG/GGG loop 6 is likely detrimental to catalysis.

The residue-by-residue pattern of J(ωN) within loop 6 of PGG/GGG correlates with known structural features of the loop and its hinges. A general trend of increasing disorder is apparent upon moving from the N- to the C-terminal hinge. This pattern appears to be present regardless of mutation, though it is less regular and less pronounced in WT than in PGG/GGG. The trend is explicable by the higher degree of packing at the N-terminal hinge. Additionally, residues Ala169 – Ile170 neighboring the N-terminal hinge exhibit a significant binding-induced reduction in ns-scale motion in PGG/GGG [ΔJ(ωN)bind = −2.3 ns average], but no measurable difference in WT. The absence of change in WT is consistent with (a) the tight packing of its N-terminal hinge in the apo form [Figure 2(E),(G)], and (b) augmentation of its nearly-as-tight bound-form packing by hydrogen bonds between the carbonyls of N-hinge sites Pro166 and Val167 and the amide protons of Ala169 and Ile170. The binding-induced order of Ala169 and Ile170 in PGG/GGG is consistent with a partial restoration of WT-like structure upon 2-PGA binding. A potential reason is that the mutant’s retention of Pro166 may restrict the N-terminal hinge enough to allow the noted closed-form hydrogen bonds with Ala169 and Ile170. Contrasting behavior occurs in C-terminal hinge. Therein, residue 175 shows increased disorder on 2-PGA binding to PGG/GGG [ΔJ(ωN)bind = 1.3 ± 0.2 ns], and the opposite for WT [−1.2 ± 0.2 ns]. This indicates that the fully mutated C-terminal hinge of PGG/GGG cannot form the two backbone hydrogen bonds of residue 176 that stabilize the closed form of the WT protein.

Dynamic and Kinetic Conclusions

We have presented a broad array of structural and dynamic data demonstrating the presence of unnatural backbone disorder in the PGG/GGG mutant enzyme. This includes the slow (< 750 s−1) motions apparent in the conformationally heterogeneous central residues of loop 6 (Figure 5), as well as the large increases in ns-scale motion observed in all loop 6 residues of PGG/GGG (Figure 7). In addition to these unnatural motions, loop 6 and its neighbor, loop 7, apparently lack the essential μs – ms open-close conformational motion that was observed in WT here (Figure 6) and in numerous earlier studies.8,10–15 Perturbations introduced by the glycine hinge mutations extend beyond loops 6 and 7 to include several vicinal sites, including residues that participate in the active site (Figure 4). The mutation-induced conformational changes are generally characterized as off-pathway for loop-6 residues, while on-pathway perturbations were typical among residues participating in the active site.

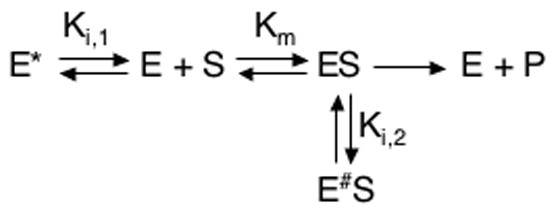

The observed disorder in loop 6 and nearby elements of PGG/GGG is implicated in the loss of catalytic function. Results here detail why a balance of structural rigidity and flexibility is essential, as excessive flexibility provides access to conformational states that may be expected to be sub-optimal for enzymatic activity and/or enzyme-substrate interactions. Our data clearly show the existence of unnatural conformational states in PGG/GGG, as well as motion on timescales not evident in WT. In order to relate these NMR results to the demonstration by Xiang, et al.24 that PGG/GGG exhibits a 103-fold decrease in kcat and a 10-fold increase in Km relative to WT, we have formulated a modified Michaelis-Menten (MM) model that incorporates non-productive conformations (E* and E#S) of the free and bound enzyme. The proposed kinetic model is given in Scheme 3 and, assuming rapid equilibrium, yields the reaction velocity profile

| (2) |

which matches the standard MM expression except for modifications to the constants

| (3) |

and

| (4) |

by the inhibitory equilibrium constants, Ki, 1 = [E]/[E*] and Ki, 2 = [ES]/[(E#S)]. Thus, Vm,eff and Km,eff describe PGG/GGG kinetics in relation to the WT constants, Vm and Km. This model yields (1) Vm,eff < Vm and (2) if Ki, 1 < Ki, 2, then Km,eff > Km. These effective changes qualitatively match the PGG/GGG kinetics observed by Xiang, et al.

The success of our model in reproducing observed PGG/GGG kinetic behavior (Vm,eff > Vm and Km,eff > Km) requires consideration of both inhibitory equilibria. In contrast, if only the E ↔ E* process is taken to be kinetically relevant (e.g., Ki,2 → ∞), then Km,eff > Km results,41 partially matching PGG/GGG behavior, but no change in Vm occurs, in conflict with the mutant’s 103-fold observed reduction in kcat. Alternatively, incorporating only ES ↔ E#S (e.g., Ki,1 → ∞) yields the anticipated velocity decrease, but gives , in opposition to observed behavior. The relative significance of the two inhibitory equilibria may be estimated from fits of equation (2) to observed PGG/GGG profiles from Xiang, et al. and subsequent solution of equations (3) and (4) for Ki,1 and Ki,2. With DHAP as substrate, fits yielded (Km,eff, Vm,eff) = (3.4 ± 0.3 mM, 0.37 ± 0.01 μM·s−1), where Km,eff was corrected for the presence of arsenate,24 and calculation from equations (3) and (4) yielded (Ki,1/Ki,2)DHAP = (0.28 ± 0.03). With GAP as substrate, we obtained (Km,eff, Vm,eff) = (4.0 ± 0.3 mM, 2.68 ± 0.07 μM·s−1), and in turn (Ki, 1/Ki, 2)GAP = (0.12 ± 0.01).

In conclusion, these studies indicate that the strict set of loop-6 residues in TIM are maintained by evolutionary selection that ensures a balance of dynamic and restrictive features in the N and C-terminal hinge sequences. This design places movement on the timescale of the catalytic turnover to allow effective substrate binding and facilitate catalysis with minimal side-product formation. Previous, structural design principles have not fully explained the evolutionary deselection of glycine among loop-6 hinge sites. Our structural and dynamic characterization of WT cTIM and the glycine hinge mutant, PGG/GGG, demonstrates that the small size of this amino acid provides detrimental motional freedom. This leads to (1) non-productive (off-pathway) conformations of both the apo and substrate-bound mutant enzyme, and (2) a shift of loop-6 dynamics in PGG/GGG from the μs timescale, where they are normally integral to the catalytic process, and towards the ps – ns regime with corresponding increases in configurational entropy of the free and bound enzyme that reflect increased access to non-functional conformations. Finally, PGG/GGG’s infrequent population of the closed form of loop 6 yields perturbed loop-7 and active-site conformations that are on the catalytic pathway, but which exhibit reduced competency for catalysis.

Materials and Methods

Chemical reagents were obtained by purchase from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted.

Protein Growth and Expression

Cultures were successively grown in Luria broth (LB) rich medium and then M9 minimal medium. with 0.4% (w/v) glucose in various ratios of D2O. For uniform 15N labeling, 99% 15N ammonium chloride was used in the M9, and, for uniform (13C,15N), 99% 13C6 glucose was additionally used, both from Cambridge Isotope Labs (Andover, MA). All LB and M9 cultures were prepared with initial concentrations of 100 μg/mL of carbenicillin.

WT and mutant PGG/GGG expression plasmids for isotopic labeling and for expression of protein quantities sufficient for NMR samples were derived from the expression plasmids prepared by Xiang, et al.24 The WT cTIM and PGG/GGG cTIM genes were subcloned into a pET15b vector (Invitrogen) by PCR using the 5′-NcoI site and introducing a BamH I site at the 3′ end of the cTIM gene. pET15b/cTIM, for WT cTIM, or pET15b/PGG/GGG for PGG/GGG cTIM, was transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3). Transformed cells were plated to LB-agar containing 100 μg/mL carbenicillin and grown at 37 °C for ~12 hrs. A single colony was used to inoculate a 25 mL LB culture grown overnight in a baffled 125 mL Erlenmeyer shake flask at 37 °C and 225 rpm (i.e., standard growth conditions). From this, 1 mL was taken to inoculate a 25 mL culture in M9 with 50% D2O, which was grown to OD600 ~ 0.6 under standard conditions. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation then resuspended and divided equally into 4 × 250 mL of 99% D2O M9. Note that 99% deuteration at this stage was used for all (2H,15N)-labeled samples, while for (2H,13C,15N) labeling 70% D2O is recommended and was applied as discussed in the subsection on NMR samples. These final-stage cultures were grown under standard conditions to OD600 ~ 0.7, at which point the temperature was adjusted to 30 °C and cTIM expression was induced by addition of IPTG to 0.4 mM final concentration. Carbenicillin concentration was boosted by 50 μg/mL one h post induction and again 9 h post induction. Approximately 18 h post induction, the cells were pelleted by spinning for 20 min at 4 °C and 5,000 g. Expression of PGG/GGG cTIM, which preceded that for the WT, employed a slightly modified protocol wherein the final M9 expression culture was only 300 mL and was incubated post induction at T = 26 °C for 24 h. Total cTIM production appears to have been lower in that case, as we obtained post-purification yields of 85 mg WT and ~25 mg PGG/GGG per L of M9.

Protein Purification

Cell paste from an M9 expression culture was resuspended in buffer C [pH 7.5, 10 mM tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (Tris)], and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) protease inhibitor was added to a concentration of 0.4 mM. To lyse the cells, this suspension was sonicated twice. The cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 50,000 g and the filtered (0.45 μm) supernatant applied to a 20 mL DEAE-FF weak anion-exchange column (Amersham Biosciences/GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) that was pre-equilibrated with buffer C. Chromatographic separation consisted of a gradient from 1:0 to 0:1 of buffer C:D over 340 mL at 2 mL/min, where buffer D is 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5 with 150 mM KCl. cTIM containing fractions were pooled and concentrated with Centriprep and Centricon centrifugal filter devices (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) with 10,000 Da molecular-weight cutoffs. Concentrated samples were judged at >95% cTIM purity by SDS-PAGE. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was used to estimate levels of 2H incorporation. Finally, we note that expression in the tpi− E. coli strain DF502 as described by Xiang, et al.,24 is necessary to avoid contamination with native E. coli TIM when kinetics experiments are of interest.

NMR Samples

NMR samples contained 10 mM MES, pH = 6.5, 10 mM NaCl, 7.5% D2O and 0.02% (w/v) NaN3. For NMR spin-relaxation experiments, sample concentrations were limited to no more than 950 μM cTIM dimer, above which an elevated average R2 was observed, indicating possible aggregation. WT cTIM concentrations were determined using the 280-nm extinction coefficient of ε280 = 44,400 M−1cm−1 ( ) determined by Furth, et al.42 For the PGG/GGG dimer, which is missing Trp168, we used ε280= 36,800 ( ), obtained by scaling the WT value with the ratio of PGG/GGG to WT coefficients calculated from their primary sequences on ExPASy. (See http://us.expasy.org/tools/protparam-doc.html.) Interestingly, we independently validated the WT ε280 of Furth, et al. using our titration of 2-PGA to WT cTIM described in the following segment on 2-PGA titration. Finally, bound-form samples included saturating concentrations of 2-PGA specific to WT and PGG/GGG. Appropriate substrate concentrations are known from previous binding studies,24 and were confirmed here by NMR monitoring of the 2-PGA titration.

Samples for spin relaxation were uniformly (2H, 15N) labeled with 99% 15N and 2H levels for both WT and PGG/GGG. Samples for assignment were uniformly (2H, 13C, 15N) labeled with 99% 15N and 13C incorporation and 2H levels at 70% for WT and 99% for PGG/GGG. As reported in Table 1, reduced assignment levels were obtained for the more highly deuterated PGG/GGG sample. While such high-level deuteration is generally advantageous for spectral resolution and sensitivity, it can greatly reduce the S/N at sites where the amide hydrogen (with 2H/1H ratio matching that of the expression medium) exchanges very slowly with the 90%-protonated H2O solvent. For example, this is likely responsible for the poor signal from sites in the tight β barrel of cTIM. In hindsight, we found that lower deuteration levels (~70%) were better for triple-resonance experiments. These can tolerate poorer resolution that would cause severe overlap in lower-dimensional spectra. WT-assignment experiments were performed following those on PGG/GGG and utilized 70% deuteration level in the (2H,13C,15N)-labeled expression medium, resulting in higher assignment levels.

2-PGA Titration

2-PGA was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). We determined the concentration of our 127.0 mM, pH 6.5 stock 2-PGA solution using the method of Fiske and Subarrow.43 Consistent sample pH was maintained during the titration experiment.

The on/off 2-PGA binding equilibrium was characterized by NMR monitoring of the titration at T = 20 °C. For WT cTIM, we measured (1H,15N)-HSQC peak volumes of affected resonances that were duplicated by the observed slow-exchange effects. For PGG/GGG, fast-to-intermediate exchange was apparent during the 2-PGA titration, averaging apo and bound peaks to a single population-weighted resonance position. We determined the fraction of bound protein (pb) assuming a linear model for two-site exchange, where

| (5) |

in the slow-exchange WT case, where Ia and Ib are the apo and 2-PGA-bound peak intensities, and

| (6) |

in the fast-exchange PGG/GGG case, where ν is the 2-PGA-dependent peak position and νa and νb are the fixed apo and bound positions. In the case of PGG/GGG, the resulting curve of pb vs equivalents of 2-PGA was fit to a nonlinear expression with the binding dissociation constant, KD = ([E] [ES]/[E]) as the only free parameter. A simultaneous fit to data from the residues Lys18, Val123, Thr177, Val212 and Thr213 yielded KD = (1.04 ± 0.13 mM) with uncertainty reported as the 95% confidence interval. This is similar to the value of (0.26 ± 0.19) mM determined by Xiang, et al.24 using fluorescence to monitor 2-PGA binding. For the WT protein, the collected pb vs 2-PGA data was too linear to allow meaningful assessment of KD, which is (21 ± 4) μM according to previous determination.44 The WT analysis did, however, clearly identify the saturation point for this tight-binding substrate at 2 equivalents of 2-PGA per cTIM dimer, confirming the ε280 from Furth, et al.

Finally, the rate of 2-PGA dissociation (koff) was determined by fitting NMR line shapes from the same titration series that was used above to obtain KD. We again assumed a response resulting from two-site exchange. The fitted one-dimensional 1H line shapes were pre-integrated along the 15N dimension using home-written scripts interfaced with NMRPipe, while the ultimate line-shape analysis was done with home-written Matlab code (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA) and algorithms described previously.45 For PGG/GGG cTIM, the analysis yielded koff = 1800 ± 300 s−1. Tighter binding of 2-PGA to the WT cTIM enzyme prevented determination of koffWT by this method. However, koffPGG/GGG is similar to koffW T ~ 1000 s−1 for yeast TIM.12 This suggests that the cTIM koff is at most weakly perturbed by glycine hinge substitution, as the yeast and chicken enzymes have the same overall secondary structure, 100% sequence identity in the active site and loop 7 and 87% identity in loop 6 and surrounding residues.

NMR Experiments

Resonance assignments were determined from data collected on a Varian Inova 600 MHz (14.1 T) spectrometer. Spin-relaxation experiments were performed both on this 600 MHz system and on either Varian Inova or Bruker Avance 800 MHz spectrometers. All Varian instruments were located at Yale and were equipped with conventional triple-resonance probes, while the Bruker system is at the New York Structural Biology Center and utilized a cryogenically cooled 1H coil and pre-amplifier for improved signal-to-noise. In all NMR experiments, the sample temperature was calibrated using 100% methanol as a standard and T = 20 °C was used. Data sets were processed using NMRPipe,46 while analysis was performed using Sparky47 and home-written Mathematica (Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL) programs. Details or exceptions are noted below.

NMR Assignment Experiments

Resonance assignments were determined using modified TROSY-based HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HN(CA)CB, HN(CO)(CA)CB, HNCO, and HN(CA)CO experiments27,28 performed at T = 20 °C and 14.1 T (600 MHz 1H frequency). Typically, we used a 1H spectral width of 20 ppm centered at the 4.82 ppm position of the 1H2O resonance at T = 20 °C, and a 96 ms acquisition time. The 15N spectral widths were 40 ppm about the 119 ppm center of the amide region with 40 complex acquisition points. For HNCA-type experiments, the 13C carrier was centered at 56 ppm with 31 ppm spectral width and 64 complex points. HN(CA)CB-type experiments, used a 44 ppm carrier with spectral width 61 ppm and 64 complex points. HNCO-type experiments utilized a 174 ppm carrier with 22 ppm spectral width and 48 complex points. Constant-time acquisition was used for the 13C dimension, excepting HNCO-type experiments. Shifts for 13C and 15N were referenced indirectly using the 1H2O resonance. 2H decoupling via the lock channel was employed for HNCA- and HN(CA)CB-type experiments. These 3D data sets were typically processed using a digital 1H2O suppression algorithm and Lorentzian-to-Gaussian apodization for the direct (1H) dimension and Kaiser or sine-bell window functions for the indirect (15N, 13C) dimensions. A linear prediction (LP) algorithm was utilized to improve resolution in both 13C and 15N dimensions.

Analysis of Assignment Experiments

NMRPipe-processed data were converted to Sparky format for analysis of connectivities established by triple-resonance experiments. A combination of approaches was employed: (1) manual searches for connectivities with Sparky followed by probabilistic assignment of amino-acid types and sequence identity with programs from Grzesiek and Bax,48 and (2) fully automated assignment using the PISTACHIO49 program (National Magnetic Resonance Facility in Madison, WI, USA). Cross checking the results corrected ~10% erroneous assignments from PISTACHIO. Finally, two other tools were used for assignment. For 2-PGA-bound forms, the process was facilitated by following peak shifts during successive steps in the titration of the enzyme to saturation with 2-PGA. Ambiguities were resolved by acquiring a subset of the noted triple-resonance experiments on the bound form. For PGG/GGG cTIM, it was possible to increase assignment levels by further comparing spectra to those of the WT protein.

Spin-Relaxation Experiments

All experiments were performed on perdeuterated, 15N-labeled enzyme. TROSY-detected longitudinal and transverse 15N spin-relaxation experiments measuring rates R1 and R2 as well as the TROSY-detected steady state (1H,15N) nuclear Overhauser effect (ssNOE) experiment were modeled after those of Zhu, et al.50 In cases where multiple peaks are observed for a single residue, only the relaxation rates for the major conformation (largest peak) were measured. These three constants were measured for apo and 2-PGA-bound forms of both WT and PGG/GGG cTIM at two fields: 14.1 and 18.8 T (600 and 800 MHz 1H frequencies). An exception is that no 18.8 T relaxation data was collected for 2-PGA-bound PGG/GGG cTIM. The R1, R2 and ssNOE experiments were collected using a 1H spectral width of 20 ppm centered at the 4.82 ppm position of the 1H2O resonance at T = 20 °C, and a 96 ms acquisition time. For R1 and R2, 16 to 32 transients were averaged per phase-modulated increment in 15N evolution, while 64 transients were obtained for the ssNOE. A recycle delay of 2.0 s was used for R1 and R2, and of 0.25 s for the ssNOE. In the 15N dimension, 170 complex points were acquired using a spectral width of 50 ppm about the 119 ppm center of the amide region. The larger spectral width prevented overlap of the target backbone resonances with inverted side-chain peaks. R1 and R2 values were determined from the mono-exponential decay of peak amplitudes over the relaxation time series 0.0, 0.29, 0.59, 0.91, 1.26, 1.64, 2.05, 2.50 with duplicate points at 0.29, 1.26 s for R1, and 3 × 0 ms and 7 × ~19ms for R2. Exact R2 delays varied according the width of the 180° 15N pulses in a spin-echo train with 1.1 ms inter-pulse delays. Peak amplitudes were measured with a modified Sparky ‘rh’ macro that uses an averaged value taken over a 3×3 grid about the peak center. Monte Carlo analysis provided with the macro was used to assess uncertainty in the resulting rates. The (1H,15N) ssNOE was obtained from the ratio of peak heights in experiments with and without 1H saturation prior to initiation of 15N evolution. HSQC spectra corresponding to saturated and unsaturated 1H magnetization were acquired in interleaved fashion. The duration of 1H saturation was 7.0 s and a delay of that length was inserted for the saturation-free experiment. Uncertainty in the ssNOE was determined from estimates of the baseplane noise.

Spin-Relaxation Analysis

The 15N R1, R2, and (1H,15N) ssNOE values are determined primarily by fluctuations of the 15N CSA and 1H–15N dipolar interactions.51 The spectral-density function, J(ω), describes the degree of motion at frequencies ω, as determined by physical parameters of the system such as global molecular tumbling and local bond-vector fluctuations. Motion at appropriate sums and differences of the 1H and 15N Larmor frequencies determine values of R1, R2, and the ssNOE. We use the reduced spectral density approximation38 as the basis for our conversion of these relaxation constants into J(ωN), which tells us the degree of motion at NH bond vectors throughout the protein. This approximation yields

| (7) |

| (8) |

and

| (9) |

where and d = (μ0/4π)h γ HγN〈rNH−3〉 are the coupling constants for the CSA and dipolar interactions, Δσ = (−174 ± 18) ppm is the average 15N CSA assuming an axially symmetric chemical-shift tensor,52 rNH = 1.02 Å is the HN bond length, γx is gyromagnetic ratio and ωx is Larmor frequency of nucleus x, ħ is Planck’s constant divided by 2π and μ0 is the permeability of free space. The spectral density value at (0.870 ωH) was determined from the measured 15N R1 and 1H-15N ssNOE using equation (9), while J(0.921 ωH) was estimated from the 1/ω2 field dependence of J(0.870 ωH).53 These values and rearrangement of equation (7) allowed calculation of J(ωN) with uncertainty determined by propagating the uniform uncertainty in Δσ and the individually estimated uncertainties in R1 and the ssNOE.

Calculated Spin-Relaxation Parameters

Values of τm, the global molecular tumbling time were calculated using the program tmest, provided by Prof. Art Palmer of Columbia University. This program determines τm via iteratively minimization of computed spectral densities,

| (10) |

against values expected according to the measured and equations (7) and (8). The calculation assumes fully ordered local bond-vectors, i.e., squared order parameter, S2 = 1, and local correlation time, τc = 0, where τ = 1/(τm−1 + τc−1) in equation (10).54,55 Other assumptions of Rex = 0, an isotropic rotational diffusion tensor and the validity of reduced spectral density mapping, may not be valid at all sites, a concern dealt with here by using trimmed sets to obtain .54,56 Separate calculations of and were achieved using the program HydroNMR (version 5a),34,35 which predicts site-specific NMR spin-relaxation parameters by calculating global tumbling of the molecular structure in a hydrodynamic environment. In contrast to tmest, HydroNMR explicitly accounts for diffusional anisotropy. We ran calculations using a 3.2 Å atomic-element radius, T = 293 K, the corresponding viscosity of water [η = 0.01002 (dyne/cm2)·s], and other parameters as recommended. PDB coordinates 1TIM25 and 1TPH26 were used for apo and bound forms of cTIM. 1TPH is the structure WT cTIM bound by 2-phosphoglycolohydroxamate, which affects the cTIM structure in a manner similar to 2-PGA.

Scheme 1.

TIM-catalyzed reaction scheme (bracketed) with enediolate transition state and adjacent structure of the reaction intermediate analog, 2-phosphoglycolate (2-PGA) at right.

Scheme 2.

Highly conserved loop-6 sequence in TIM, here labeled for amino acids 166 – 176 found in chicken (Gallus gallus) TIM. Nomenclature used in the text assigns N1, N2, N3 to N-terminal hinge residues 166-168 and C1, C2, C3 to C-terminal hinge residues 174-176 respectively.

Scheme 3.