Abstract

β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) is one of the main protein components of senile plaques associated with Alzheimer's disease (AD). Aβ readily aggregates to forms fibrils and other aggregated species that have been shown to be toxic in a number of studies. In particular, soluble oligomeric forms are closely related to neurotoxicity. However, the relationship between neurotoxicity and the size of Aβ aggregates or oligomers is still under investigation. In this article, we show that different Aβ incubation conditions in vitro can affect the rate of Aβ fibril formation, the conformation and stability of intermediates in the aggregation pathway, and toxicity of aggregated species formed. When gently agitated, Aβ aggregates faster than Aβ prepared under quiescent conditions, forming fibrils. The morphology of fibrils formed at the end of aggregation with or without agitation, as observed in electron micrographs, is somewhat different. Interestingly, intermediates or oligomers formed during Aβ aggregation differ greatly under agitated and quiescent conditions. Unfolding studies in guanidine hydrochloride indicate that fibrils formed under quiescent conditions are more stable to unfolding in detergent than aggregation associated oligomers or Aβ fibrils formed with agitation. In addition, Aβ fibrils formed under quiescent conditions were less toxic to differentiated SH-SY5Y cells than the Aβ aggregation associated oligomers or fibrils formed with agitation. These results highlight differences between Aβ aggregation intermediates formed under different conditions and provide insight into the structure and stability of toxic Aβ oligomers.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, amyloid, aggregation, guanidine hydrochloride, unfolding

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive, neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system and the leading cause of dementia in aging population. One of the histopathological hallmarks of AD is the formation of neuritic plaques, the major protein component of which is β-amyloid peptide (Aβ). Two variants of Aβ, Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42, are the most abundant forms found in AD (Bayer et al. 2001; Turner et al. 2003).

Accumulating data show that while Aβ aggregates readily into amyloid fibrils, the Aβ species in soluble oligomeric forms rather than fibrils are closely associated with the neurotoxicity in vivo and in vitro. Toxicity has been attributed to Aβ-derived diffusible ligands (ADDLs) composed of Aβ1-42, with molecular weights between 17 and 42 kDa (Lambert et al. 1998; Klein et al. 2001) and heterogeneous globular species (also described as ADDLs) with hydrodynamic radii between 3 and 8 nm (Chromy et al. 2003). Spherical aggregates, not described as ADDLs, with radii over 15 nm have also been reported to be toxic (Hoshi et al. 2003). Toxic protofibrils of Aβ1-40 have been described with hydrodynamic radii ranging from 9 nm to over 300 nm (Walsh et al. 1999; Ward et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2002). When investigators have compared toxicity of fibril and oligomer Aβ species, they have found that the oligomeric species were more toxic (Dahlgren et al. 2002). While some investigators believe that there is a common structure associated with amyloid toxicity (Kayed et al. 2003), a careful characterization of such a common structure is still not available. Part of the challenge in elucidating the relationship between Aβ structure and toxicity is the difficulty in isolating pure samples of Aβ oligomers for characterization, although use of urea (Kim et al. 2004), low temperatures (Yong et al. 2002), or photocross-linkers have aided in their identification (Bitan and Teplow 2004). One approach has been to carefully characterize Aβ monomers and fibrils, and from those structures infer the nature of a toxic aggregation intermediate. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that even the molecular level structure of Aβ fibrils changes with aggregation conditions (Stine et al. 2003; Petkova et al. 2005, 2006; Shivaprasad and Wetzel 2006; among others).

In work presented here, we examined the differences in Aβ aggregation intermediates and final structures formed when only a simple modification in Aβ aggregation conditions was made, the presence or absence of agitation during aggregation. We show that while the final structures in the Aβ aggregation pathway are comparable by measures such as electron microscopy, the toxicity of fibrils formed are significantly different. In addition, intermediates in the aggregation pathway show significantly different structural rearrangements. When guanidine hydrochloride unfolding was used as a simple measure of stability of different aggregated species, the Aβ aggregation intermediates formed under quiescent conditions, the most toxic Aβ species we observed, were the structures that changed conformation at the lowest concentrations of guanidine hydrochloride. These results highlight the differences in Aβ aggregation mechanisms when aggregation occurs with agitation or under quiescent conditions. In addition, our results provide insight into the structure of the toxic Aβ oligomers formed during aggregation under quiescent conditions.

Results

Kinetics of Aβ aggregation with and without mixing

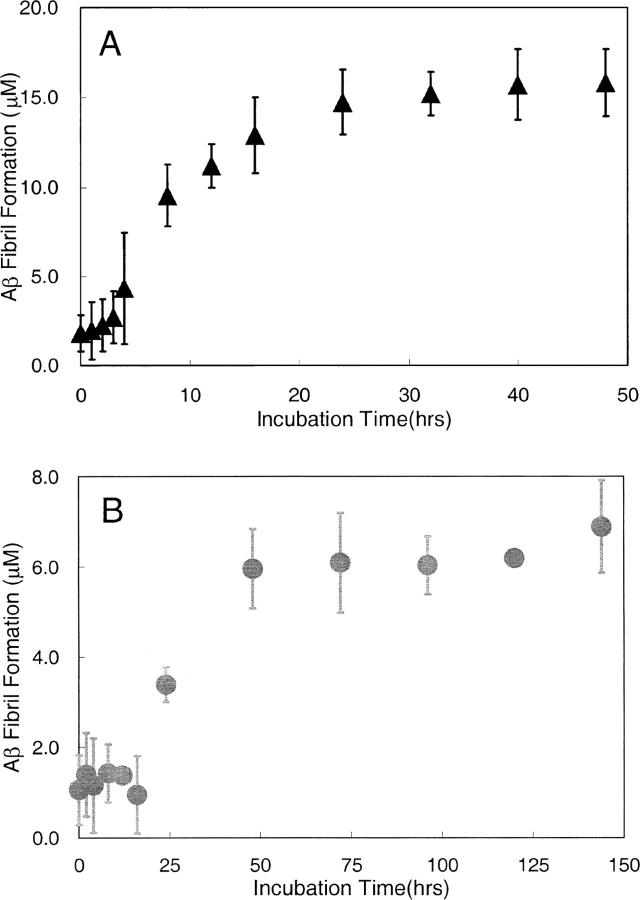

We examined the structure of 100 μM Aβ1-40 samples when aggregated with and without agitation at 37°C. Congo red binding was used as an indicator of extended β-sheet structure and changes in Aβ aggregation with time. As seen in Figure 1, the kinetics of Aβ fibril formation, as indicated by Congo red binding, follow a similar trend with and without agitation. However, the time scales for fibril formation under the two conditions differed by a factor of 2 to 4. In both cases, fibril formation followed a characteristic sigmoidal curve, with a lag phase at early incubation times, followed by a fibril growth phase, then a saturation phase. The lag phases were about 4 h and 16 h for agitation and quiescent aggregation conditions, respectively.

Figure 1.

Aβ aggregation as measured by Congo red binding as a function of time after initial dissolution of the peptide. One hundred millimolar Aβ was incubated at 37°C (A) with gentle agitation and (B) under quiescent conditions.

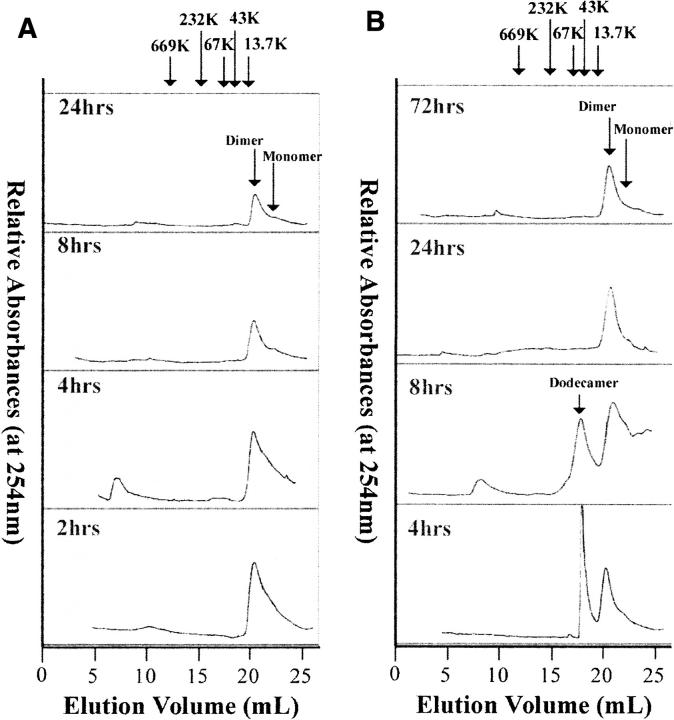

Size characterization of Aβ species during aggregation

We used size exclusion chromatography (SEC) to characterize the size of Aβ species associated with fibril formation when Aβ was aggregated with and without agitation to try to determine if there were significant differences in oligomers detectable during aggregation under the different conditions. When freshly prepared, Aβ species were observed that eluted at volumes consistent with monomer and dimer species, with an approximate 1:2 ratio of absorbance of monomer to dimer. When agitation was employed during aggregation, large Aβ species (>1500 kDa) appeared in chromatograms along with monomer and dimer as early as 2 h after the beginning of aggregation (Fig. 2A). These large species were also seen at 4 h into aggregation. After 4 h of aggregation, only monomer and dimer appeared on chromatograms as sample pretreatment (centrifugation at 7000g for 3 min) removed the largest aggregates formed. At 8 h and 24 h, the only Aβ species recorded in SEC chromatograms were monomer and dimer. The total amount of monomer and dimer species decreased with time of aggregation, indicating that more of the Aβ initially present was incorporated into large aggregated species that were removed via centrifugation prior to chromatography at later times during aggregation. Throughout aggregation, the relative ratio of monomer to dimer appeared constant, suggesting the two species were in equilibrium.

Figure 2.

Representative size exclusion chromatograms of 100 μM Aβ at different times during aggregation. Aβ samples were incubated at 37°C for (A) 2, 4, 8, and 24 h with gentle agitation and (B) 4, 8, 24, and 72 h under quiescent conditions.

Analogous to that observed in chromatograms taken during aggregation with agitation, in chromatograms taken of samples when aggregation proceeded under quiescent conditions, species eluting at volumes consistent with monomer and dimer of Aβ were present at all times, in an approximate 1:2 absorbance ratio, with their relative amounts decreasing with time during aggregation (Fig. 2B). Unlike aggregation with agitation, when aggregation proceeded under quiescent conditions, a species that eluted with an approximate molecular weight of ∼53 kDa was observed at 4 and 8 h after the beginning of aggregation. At later times this species was no longer present. The relative amounts of Aβ species observed during aggregation with and without agitation were calculated and are displayed in Table 1.

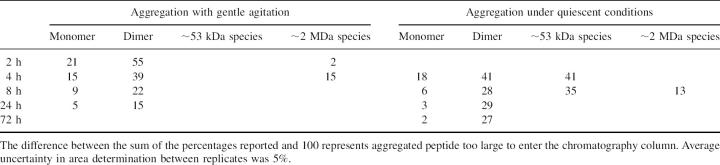

Table 1.

Percentage of Aβ species in peptide samples aggregated for different lengths of time as determined from peak areas of SEC chromatograms

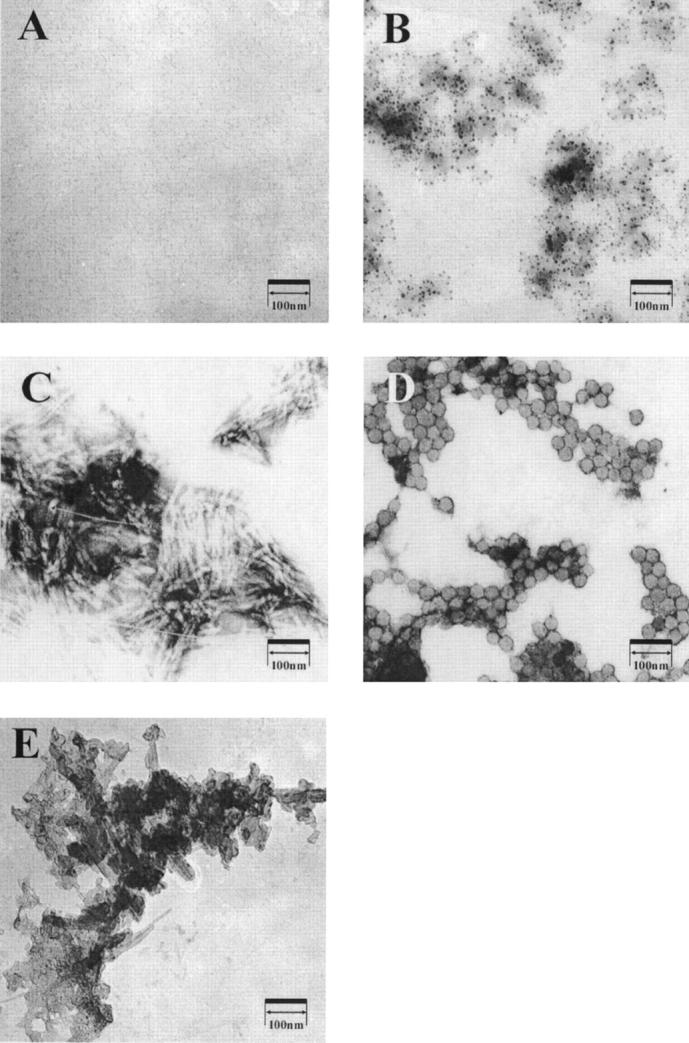

Electron micrographic images of Aβ species during aggregation

Electron microscopy was used to visualize Aβ species formed during aggregation with and without agitation. As seen in Figure 3A, there were no distinct structures observed in micrographs of fresh Aβ. At times 2 h after aggregation with agitation (Fig. 3B), small globular species with diameters under 5 nm could be observed. At 4 and 8 h after the initiation of aggregation with mixing, small globular species along with some fibril species could be seen in micrographs (data not shown). At 24 h, dense mats of fibrils could be observed (Fig. 3C). When aggregation proceeded under quiescent conditions, at 8 h after initiation of aggregation, uniform spherical species with diameters of 20–30 nm were seen (Fig. 3D). Species with this size and structure were never seen when aggregation proceeded with mixing. At 72 h, fibrils could be seen in micrographs that appeared more crystalline than fibrils observed when agitation was used during aggregation (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Representative EM images of 100 μM Aβ at different times during aggregation at 37°C; (A) fresh Aβ, (B) 2 h of aggregation with gentle agitation, (C) 24 h of aggregation with gentle agitation, (D) 8 h of aggregation under quiescent conditions, and (E) 72 h of aggregation under quiescent conditions.

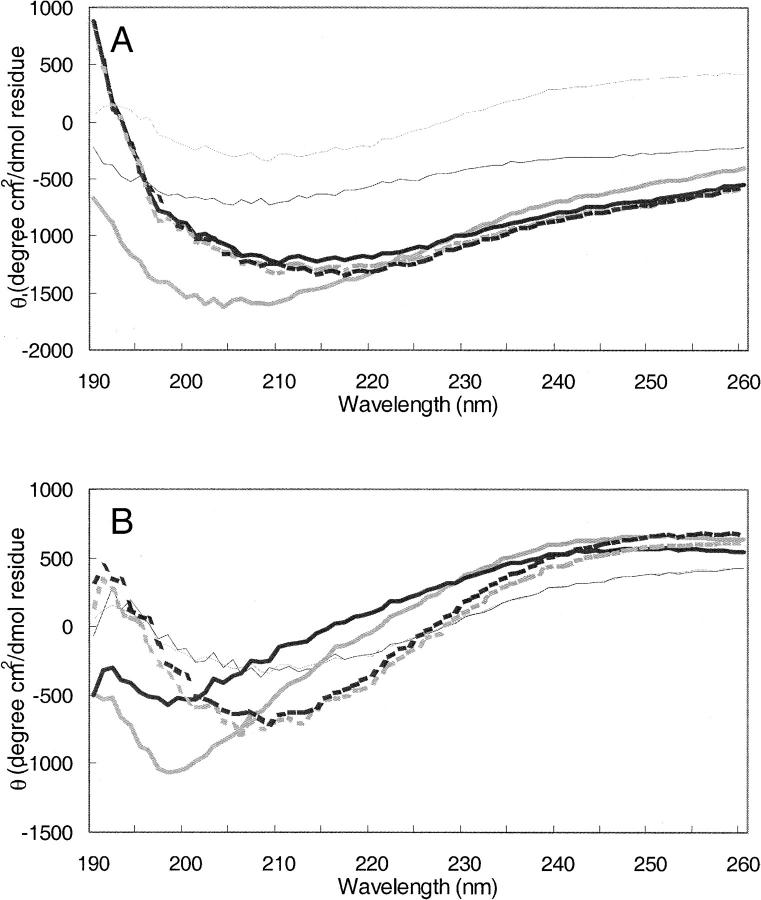

Changes in Aβ secondary structure during aggregation

Circular dichroism (CD) was used to examine secondary structure changes of Aβ during aggregation. As seen in Figure 4, the CD spectrum of fresh Aβ indicated that the fresh peptide contained a β-sheet-rich structure with some α-helix and random coil contribution. When aggregation proceeded with agitation, while changes in the CD spectrum were observed, they did not indicate a change in the basic secondary structure elements of the aggregating peptide (Fig. 4A). However, when Aβ was aggregated under quiescent conditions, a significant spectral shift in the CD spectrum was observed at times between 4 and 10 h after initiation of aggregation, consistent with a decrease in β sheet and an increase in random coil structure (Fig. 4B). The appearance of the spectral shift in CD structure at intermediate times during aggregation under quiescent conditions coincided with the observation of the large (20 nm) globular species on electron micrographs and the peak that elutes at an approximate molecular weight of 53 kDa on SEC chromatograms. At longer times after initiation of aggregation, the secondary structure of the aggregating Aβ took on more β-sheet content.

Figure 4.

Secondary structure of Aβ at different times during aggregation with gentle agitation (A) and under quiescent conditions (B). All times indicate time of incubation at 37°C after initial dissolution of 100 μM Aβ. Representative CD spectra are shown. (Light thin solid line) fresh Aβ; (dark thin solid line) 2 h; (light thick solid line) 4 h; (dark thick solid line) 8 h; (light thick broken line) 10 h; (dark thick broken line) 12 h.

Stability of Aβ species to structure change in denaturant

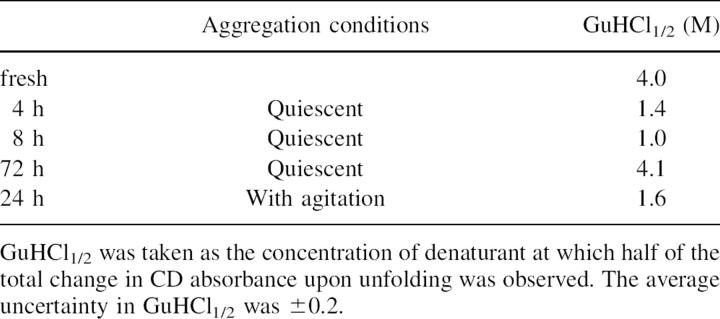

In order to obtain a relative measure of apparent stability of different Aβ species that formed during aggregation under different conditions, we examined structural changes of the Aβ species upon incubation with a denaturant, guanidine hydrochloride. This method was carried out just as typical protein unfolding experiments used to examine stability of folded proteins (Pace 1990). Figure 5 shows the change in Aβ structure as measured by CD as a function of different concentrations of denaturant for fresh and two aggregated samples, the sample aggregated for 8 h under quiescent conditions and the sample aggregated for 24 h with gentle agitation. In Table 2, the midpoints of the denaturation curves, GuHCl1/2, are presented. As seen in Figure 5, fresh Aβ required more denaturant before undergoing the maximum observed structural change, while Aβ fibrils formed with agitation and Aβ oligomeric species formed during Aβ aggregation under quiescent conditions required the least amount of denaturant to undergo the maximum observed structural change. The concentrations of denaturant at which the midpoint in the denaturation curve were observed (Table 2) were lowest for Aβ oligomers aggregated under quiescent conditions for 4 and 8 h and Aβ fibrils formed with agitation and were greatest for both fresh Aβ and Aβ fibrils formed under quiescent conditions. Because final CD results varied between samples of Aβ prepared at the same concentration, differing only in aggregation time and agitation conditions, it is clear that these CD measurements are not under equilibrium conditions. Thus, in this context, these measurements are not indicating the thermodynamic stability of oligomers, but rather their kinetic stability in the presence of guanidine. We have made no attempt to quantify changes in free energy associated with “unfolding” as it is not clear that equilibrium folding models apply to Aβ aggregation.

Figure 5.

Effect of guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) on structure of different Aβ aggregates as measured by CD intensity at 220 nm. Aβ samples (100 μM) were aggregated either with gentle agitation or under quiescent conditions at 37°C for various lengths of time, after which Aβ samples were mixed with GuHCl to a final concentration of 10 μM Aβ and 0.5–7 M GuHCl. CD intensity at 220 nm of Aβ samples in GuHCl were monitored for 2 h, until no further detectable changes in structure or CD intensity occurred. CD intensities at 220 nm were used for Aβ stability tests. (Filled triangles) fresh Aβ; (open squares) Aβ aggregated with gentle agitation for 24 h; (filled circles) Aβ aggregated for 8 h under quiescent conditions.

Table 2.

Midpoint of denaturation curve, GuHCl1/2, as a function of aggregation conditions

Biological activities of Aβ species

Aβ is known to be toxic to neuronlike cells when aggregated; however, it is not clear if fibrils or aggregation intermediates formed by different pathways have the same toxicity. We therefore examined viability of differentiated SY5Y cells that were treated with Aβ samples prepared with or without agitation using a relatively fast viability assay (2-h incubation with Aβ) in order to minimize structural and morphological changes of Aβ during incubation with cells. Two markers were used for viability, annexin-V-PE, which binds to phosphatidyl serine on the surface of early apoptotic cells, and 7-AAD, which binds to membrane permeable cells. Viable cells were taken as those that were both annexin-PE and 7-AAD negative. Positive and negative controls were used to determine assay sensitivity over the short incubation time.

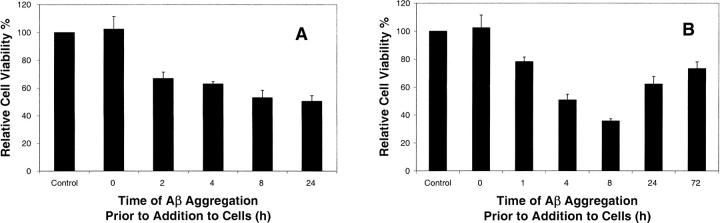

Relative cell viabilities of cells treated with Aβ samples aggregated under different conditions are shown in Figure 6. Cells treated with fresh Aβ had almost the same cell viability (102% ± 9%) as negative control population (p > 0.05). Aβ species prepared at different times of aggregation with agitation were significantly more toxic than controls (p < 0.05), and toxicity increased with time of aggregation of the peptide (Fig. 6A). When Aβ was aggregated under quiescent conditions, a different pattern of toxicity with time of aggregation was observed (Fig. 6B). The toxicity of species formed within the first 8 h of aggregation under quiescent conditions increased to a maximum observed toxicity at 8 h. Species formed after 24 or more hours of aggregation, however, had significantly less toxicity than those formed at earlier times. In addition, the toxicity of fibrils formed with agitation (24 h) was significantly greater than the toxicity of fibrils formed under quiescent conditions (72 h) (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Relative cell viability of differentiated SY5Y cells treated with 100 μM Aβ that had been aggregated with gentle agitation (A) or under quiescent conditions (B) for different lengths of time prior to addition to cells. Cells were incubated with Aβ for 2 h prior to assessment of viability via staining with annexin and 7AAD followed by flow cytometry.

Discussion

In the effort to develop new methods of preventing toxicity associated with Aβ of Alzheimer's disease, many investigators have sought to elucidate both the mechanism of Aβ aggregation (Lomakin et al. 1997; Esler et al. 2000; Pallitto and Murphy 2001; Kim et al. 2004; O'Nuallain et al. 2005; Sabate and Estelrich 2005; Pellarin and Caflisch 2006) and the relationship between Aβ structure and toxicity (Lambert et al. 1998; Ward et al. 2000; Walsh et al. 2002; Klein et al. 2001; Chromy et al. 2003; Hoshi et al. 2003). In the work we present here, we show that when Aβ is aggregated under different conditions, different mechanisms of aggregation appear to occur, and the oligomers formed during aggregation have different toxicities.

As seen in Figure 1, kinetics of Aβ aggregation, regardless of the presence or absence of agitation, differ in scale, but appear similar in form. The characteristic lag in development of extended β-sheet structure to which Congo red binds is typical of a nucleation mechanism of aggregation that a number of investigators propose for Aβ fibril formation (Lomakin et al. 1997; Pallitto and Murphy 2001; Pellarin and Caflisch 2006). Increased rates of aggregation with agitation relative to Aβ aggregation under quiescent conditions has also been observed by others (Tycko 2006; Petkova et al. 2006). In this study, we provide agitation by rotation at 18 rpm on a laboratory rotator. Others have used gentle agitation and sonication to mix during Aβ aggregation and found that the higher energy mixing increased the rate of aggregation (Petkova et al. 2006). While Congo red binding suggests that aggregation with and without agitation may be similar, data obtained from size exclusion chromatography, CD spectroscopy, and electron microscopy (Figs. 2–4) suggest that there are significant differences in the mechanism of aggregation with and without agitation of Aβ.

SEC chromatograms indicate that, throughout aggregation under conditions with or without agitation, species that elute at volumes consistent with monomer and dimer are present in the same ratio of peak areas in all chromatograms. This indicates these two species were in equilibrium with each other under all these conditions. Others have made similar observations of Aβ aggregation (Pallitto and Murphy 2001). The amounts of monomer and dimer relative to other species decreased with time, corresponding to increases in fibril formation as indicated by Congo red binding (Table 1). Different investigators have suggested that monomer or dimer are the building blocks for fibril nucleation or growth (Garzon-Rodriguez et al. 1997; Tseng et al. 1999; Roher et al. 2000; Hwang et al. 2004).

CD data indicate that Aβ was largely β-sheet prior to aggregation and did not undergo significant secondary structural rearrangements when aggregated with agitation. When aggregated under quiescent conditions, however, a dramatic shift in structure was observed at intermediate times (∼4–8 h after aggregation is initiated), which corresponded to the presence of an intermediate-sized species in chromatograms (approximate molecular weight as estimated from elution volume on SEC of 53 kDa) and large globular species in electron micrographs. None of these intermediate species were observed when aggregation proceeded with agitation.

A number of investigators have observed Aβ aggregation intermediates, formed either at low temperature or via a particular preparation method, sometimes referred to as Aβ derived diffusible ligands (ADDLs) (Lambert et al. 1998; Klein et al. 2001), that have molecular weights within the range we observed via SEC. A number of reports indicate that these ADDLs are the (or one of the) toxic Aβ oligomers (Lambert et al. 1998). Others have described spherical species of various sizes that are Aβ aggregation intermediates with sizes ranging from 3 to 20 nm, and some up to 100 nm depending on starting peptide and preparation method (Harper et al. 1999; Westlind-Danielsson and Arnerup 2001; Hoshi et al. 2003). Toxicity of the spherical Aβ species has also been reported (Hoshi et al. 2003). The ∼53-kDa species observed via SEC may be distinct from the spherical species observed via electron microscopy; however, it is not possible to tell from our data. Others have observed the formation of Aβ micelles (Lomakin et al. 1996; Yong et al. 2002; Kim and Lee 2004; Kim et al. 2004; Sabate and Estelrich 2005) which might appear as a large globular species via EM, but could change apparent molecular size during chromatography. Alternately, it is probable that via SEC we would not be able to detect a globular protein aggregate of 20 nm diameter as it would be removed from our sample during our sample pretreatment, nor would we be able to detect 53-kDa proteins via EM as they would be below the resolution of the microscope used.

That we observe dramatic structural rearrangements with aggregation under quiescent conditions but did not observe the same structural rearrangements when aggregation occurred with agitation is not surprising. If Aβ aggregation is nucleation dependent as others propose (Lomakin et al. 1997; Ramírez-Alvarado et al. 2000; Wogulis et al. 2005), then with agitation, one would expect more rapid collisions of molecules and faster nucleation, both in solution and against the walls of the tube in which aggregation took place. The faster rate of nucleation would mean that Aβ would have less time to undergo any intramolecular structural rearrangements that might be energetically favorable and increase stability of the fibril formed. Without agitation, the rate of peptide collision with other peptides would be slower, allowing more time for intramolecular rearrangement of the peptide before combining with other peptides to form an aggregation intermediate. In short, agitation would favor intermolecular rearrangements to bury hydrophobic surfaces or form hydrogen bonds that would lead to aggregation, while quiescent conditions would favor intramolecular rearrangements to bury hydrophobic surfaces. These intramolecular rearrangements could lead to formation of aggregation intermediates not seen when intermolecular interactions predominate.

It has recently been suggested that amyloid fibrils form through a micelle intermediate when relatively unstable β-sheet-forming peptides form the building blocks of the amyloid, while no micelle intermediate would be seen if a stable β-sheet-forming peptide were used as fibril precursors (Pellarin and Caflisch 2006). It is possible that under quiescent conditions, Aβ forms a somewhat unstable monomer, but with agitation, a more stable β-sheet monomer or dimer is formed.

Work coming out of the laboratories of Tycko (Petkova et al. 2005, 2006) and Wetzel (Whittemore et al. 2005; Shivaprasad and Wetzel 2006; Williams et al. 2006) demonstrates that Aβ fibrils formed with agitation and those formed under quiescent conditions have different molecular level structures. The presence of intramolecular salt bridges, the number of layers of β-sheets that form a protofibril unit, and peptide residues that make up β-sheet segments may all be different in fibrils formed under the different conditions. Thus it is not surprising that our data suggest that different mechanisms of aggregation govern fibril formation with and without agitation.

The relative stability of species formed during aggregation in the presence and absence of agitation can be inferred from data collected on conformation change of Aβ in a denaturant (Fig. 5; Table 2). When Aβ was aggregated with agitation, fibrils underwent conformation change in denaturant more readily than monomer. The trend in change in protein conformation with denaturant concentration (or slope of changes in free energy with denaturant concentration “m”) is traditionally interpreted as a measure of buried surface (Myers et al. 1995; Pace et al. 1996), suggesting that Aβ fibrils formed during agitation have more buried surface than Aβ monomers. When Aβ was aggregated under quiescent conditions, aggregation intermediates underwent conformation change more easily than either fresh or fibril Aβ, suggesting the intermediate had the most buried surface. While this interpretation of our results is in disagreement with an earlier report (Kremer et al. 2000), it is consistent with data that comes from our laboratory of the fluorescence of the hydrophobic probe, 1-anilino-8-naphthalene sulfonic acid (ANS), indicating that the aggregation intermediate formed under quiescent conditions was less hydrophobic or bound less ANS than either monomer or fibril (unpubl. results).

We examined biological activity or toxicity of fibrils and aggregation intermediates formed with and without agitation (Fig. 6). Toxicity of fibrils was greater when formed with agitation, while toxicity of aggregation intermediates formed between 4 and 8 h after initiation of aggregation under quiescent conditions were more toxic than other species formed. Fibrils formed with agitation and aggregation intermediates formed under quiescent conditions changed structure more readily in denaturant than other species examined (Fig. 5). Thus, for samples and conditions considered here, the difference in apparent stability in denaturant correlated with toxicity. A number of investigators have suggested that Aβ membrane interactions via Aβ conformational changes are important in the mechanism of Aβ toxicity (McLaurin and Chakrabartty 1997; Terzi et al. 1997; Demuro et al. 2005). Behavior of Aβ in a membrane and in a denaturant might be analogous. Thus, one could speculate that toxicity of an Aβ species may be related to its ability to change structure within the cell membrane.

There are several alternative explanations of the data presented. Others have reported that Aβ oligomers with structures similar to those we describe forming during aggregation under quiescent conditions are more toxic than fibrils (Dahlgren et al. 2002; Hoshi et al. 2003). However, some investigators have observed that fibrils formed under quiescent conditions, then sonicated, are more toxic than fibrils formed with agitation (Petkova et al. 2005). When comparing toxicity of fibrils formed via different methods, it has been very difficult to characterize concentration or number of fibrils in a solution. The average length of fibrils has been shown to change with aggregation condition (Walsh et al. 1999; Ward et al. 2000). The number of fibrils might also change with aggregation conditions (or with sonication). With agitation, one would expect larger numbers of fibrils or fibril nuclei than would be formed without agitation. Larger number of fibril ends or fibril nuclei would be expected to be associated with greater toxicity (Wogulis et al. 2005). Consequently, differences in toxicity observed may simply be due to differences in oligomer or fibril concentrations in solution.

In summary, we report structure and toxicity of Aβ species formed during aggregation via different methods. We show that fibrils formed via different methods do not have the same toxicity nor the same apparent stability to denaturants, nor do they appear to be formed via the same mechanism or have the same intermediate aggregation species. Aggregation intermediates formed under quiescent conditions appear to be similar to Aβ oligomer species reported by others such as ADDLs or spherical globules. They also may be the micelles suggested by others to be part of the Aβ aggregation pathway from which nuclei form. The same aggregation intermediates had low β-sheet content, low stability in denaturants, and high toxicity. This work provides insight into the structure of toxic Aβ oligomers and highlights differences in aggregation mechanisms of Aβ fibrils formed with and without agitation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

β-Amyloid (Aβ)–(1-40) was purchased from AnaSpec. Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells were purchased from ATCC (CRL-2266). Cell culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies. Superose6 HR 10/30 Column was purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. All other disposable supplies for FPLC were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Congo red was purchased from Fisher Chemicals. All other chemicals, unless otherwise specified, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co.

Protein sample preparation

Lyophilized Aβ1-40 was freshly dissolved in 0.1% (v/v) Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) solvent at the concentration of 10 mg/mL. This solution was incubated at room temperature for 20–30 min in order to completely dissolve the Aβ. Filtered phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.4 mM KH2PO4 at pH 7.4) was added to the Aβ solution to make the final concentrations used in experiments. For cell viability assays, MEM medium was used instead of PBS buffer. For aggregation with gentle mixing, Aβ samples were mixed in 1-mL vials filled 0.6 mL of solution mounted on a rotator at 18 rpm and 37°C, and samples were taken out with time. For aggregation under quiescent conditions, Aβ samples were incubated without disturbance in a 37°C incubator.

Congo red binding

Congo red was dissolved in PBS at the concentration of 120 μM and syringe filtered. The Congo red solution was mixed with protein samples at 1:9 ratios to make the final concentration of Congo red 12 μM. After a short vortex, the mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 30–40 min. Absorbance was measured from 400 nm to 700 nm (UV-Vis spectrometer model UV2101, Shimadzu Corp.). Alternatively, Congo red absorbance was read at 405 nm and 540 nm using an Emax Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices). In both cases, PBS buffer was used as blank control. The concentration of Aβ fibrils was estimated from Congo red binding via Equation 1:

where 541At and 403At are the absorbances of the Congo red-Aβ mixtures at 541 nm and 403 nm, respectively, and 403ACR is the absorbance of Congo red alone in phosphate buffer (Klunk et al. 1999). When using the microplate reader, absorbances at 405 nm and 540 nm were assumed to be same as those at 403 nm and 541 nm.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC)

A Superose6 HR 10/30 Column in a FPLC System (Pharmacia) was used to determine the molecular size of Aβ species. PBS buffer was used as a mobile phase with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. A 100-μL sample loop was used. Aβ samples were centrifuged at 7000g for 30 sec prior to SEC analysis. Supernatants of centrifuged samples were loaded in the 100-μL loop and injected into the column. Aβ species were detected by UV detector at 254 nm. The following proteins were used for calibration standards: ribonuclease (13.7 kDa), chymotrypsin (25 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), and albumin (67 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), catalase (232 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), thyroglobulin (660 kDa), and BD 2000 (2000 kDa). To calculate relative areas of Aβ in peaks from the SEC chromatograms, first the total area of a 100-μM Aβ sample was obtained from a chromatogram obtained without a column in the FPLC system. On the basis of this total area, relative areas from the SEC chromatograms were calculated.

Circular dichroism (CD)

Secondary structure of Aβ was measured using a PiStar-180 Circular Dichroism Spectrometer (Applied Photophysics). CD spectra in the far UV range (190–260 nm) were obtained using a 1-cm quartz cell, at 37°C, using a Xe lamp as a light source, a 1.0-nm bandwidth, 1.0-nm step interval, and 1.5 sec/nm scanning speed. The spectrometer was purged with nitrogen gas during measurement. PBS buffer was used for the calibration.

Electron micrograph (EM)

Two hundred microliters of Aβ peptide solution, prepared as described above, were mixed, placed on glow discharged grids, and then negatively stained with 1% aqueous ammonium molybdate (pH 7.0). Grids were examined in a Zeiss 10C transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. Calibration of magnification was done with a 2160 lines/mm crossed line grating replica (Electron Microscopy Sciences).

Aβ stability with guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl)

One hundred micromolar Aβ samples were prepared as described in the protein sample preparation. Aβ samples at 37°C were measured at 0 (fresh Aβ) and 24 h after initial dissolution for agitated samples and 4, 8, and 72 h after dissolution for samples aggregated under quiescent conditions. GuHCl was dissolved in PBS buffer and prepared at different concentrations. Aβ samples were mixed with GuHCl solution at the ratio of 1:9. The final Aβ concentration in each sample was 10 μM. The final GuHCl concentrations varied from 0.5 M to 7 M. Aβ samples in different GuHCl concentrations were incubated at 37°C for 2 h with the GuHCl. CD spectra were taken of the incubated Aβ-GuHCl samples and each was calibrated against a solutions of GuHCl at the same concentration in PBS buffer. CD intensity at 220 nm, a typical minimum for β-sheet structures, was used as an indicator of change in protein structure with denaturant addition. The midpoint of the denaturation curve, GuHCl1/2, was taken as the concentration of denaturant at which half of the total change in CD absorbance upon unfolding was observed. To determine GuHCl1/2, the linear portion of the denaturant curve was fit to a straight line, the slope of which was used to estimate the concentration of GuHCl at which one half of the total change in CD absorbance was observed.

Cell culture

SH-SY5Y cells were grown in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 25 mM sodium bicarbonate, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. Cells were cultured in a 5% (v/v) CO2 environment at 37°C incubator. Low passage number cells were used (<p20) in all experiments to reduce instability of the cell line.

Biological activity assay

For biological activity tests, SH-SY5Y cells at a density of 1 × 105cells/well were grown in 96-well plates. Cells were fully differentiated by addition of 20 ng/mL NGF for 8 d. Aβ samples in MEM medium were added to the differentiated SY5Y cells and the cells were incubated with Aβ samples at 37°C for 2 h. Negative controls (cells in medium with no Aβ) and positive controls (cells treated with 800 μM H2O2 in 50% [v/v] medium for 2 h) were also prepared. At least 3 wells were prepared for each Aβ treatment and each positive and negative control.

Cell viability was determined by using two fluorescent dyes, Annexin V-PE and 7-Amino-actinomycin (7-AAD). Annexin V-PE is a Ca2+ dependent phospholipid binding protein that has high binding affinity for phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cells. 7-AAD is taken up by necrotic or damaged cells, whereas live cells exclude 7-ADD. In this experiment, cells unstained for both Annexin V-PE and 7-AAD were taken as live cells. In order to stain the dead cells, Aβ treated cells were washed with PBS 1 or 2 times and 1× binding buffer was added to the cells (1× binding buffer: 10 mM HEPES/NaOH at pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2). Five microliters of Annexin V-PE and 5 μL of 7-AAD were added to the cells and cells were incubated for 15–20 min at room temperature in the dark. One hundred fifty microliters of 2× binding buffer were added to the cells, and cells were collected using a scrapper. Stained cells in 96-well plates were loaded in the FACS array (BD FACSArray, BD Bioscience) and fluorescence histograms for cells were obtained. To set up compensation and gates for the cell viability assays, three sets of staining controls were prepared, unstained cells, cells stained with Annexin V-PE alone, and cells stained with 7-AAD alone. Cells not stained with either dye (population with low fluorescence intensities for Annexin V-PE and 7-AAD) were taken as live cells, and the relative cell viabilities were calculated using Equation 2:

|

where L.C.sample is live cells (%) of Aβ treatment, L.C.Ncontrol is live cells (%) of negative control, and L.C.H2O2 is live cells (%) of H2O2 treatment (positive control).

Statistical analysis

For each experiment, at least three independent determinations were made. Significance of results was determined via the t test with p < 0.05 (95% confidence interval) unless otherwise indicated. Data are plotted as the mean plus or minus the standard error of the measurement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS042686) to T.A.G. and E.J.F. We thank Dhara Patel at UMBC for her assistance in flow cytometry analysis and Ann Ellis of the microscopy imaging center at Texas A&M University for preparation of electron micrograph images.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Theresa Good, Chemical and Biochemical Engineering, UMBC, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Baltimore, MD 21250, USA; e-mail: tgood@umbc.edu; fax: (410) 455-1049.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062514807.

References

- Bayer T.A., Wirths, O., Majtenyi, K., Hartmann, T., Multhaup, G., Beyreuther, K., and Czech, C. 2001. Key factors in Alzheimer's disease: β-Amyloid precursor protein processing, metabolism and intraneuronal transport. Brain Pathol. 11: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan G. and Teplow, D.B. 2004. Rapid photochemical cross-linking—A new tool for studies of metastable, amyloidogenic protein assemblies. Acc. Chem. Res. 37: 357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chromy B.A., Nowak, R.J., Lambert, M.P., Viola, K.L., Chang, L., Velasco, P.T., Jones, B.W., Fernandez, S.J., Lacor, P.N., Horowitz, P., et al. 2003. Self-assembly of Aβ(1-42) into globular neurotoxins. Biochemistry 42: 12749–12760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren K.N., Manelli, A.M., Stine Jr, W.B., Baker, L.K., Krafft, G.A., and LaDu, M.J. 2002. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 32046–32053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuro A., Mina, E., Kayed, R., Milton, S.C., Parker, I., and Glabe, C.G. 2005. Calcium dysregulation and membrane disruption as a ubiquitous neurotoxic mechanism of soluble amyloid oligomers. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 17294–17300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler W.P., Stimson, E.R., Jennings, J.M., Vinters, H.V., Ghilardi, J.R., Lee, J.P., Mantyh, P.W., and Maggio, J.E. 2000. Alzheimer's disease amyloid propagation by a template-dependent dock-lock mechanism. Biochemistry 39: 6288–6295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon-Rodriguez W., Sepulveda-Becerra, M., Milton, S., and Glabe, C.G. 1997. Soluble amyloid Aβ-(1-40) exists as a stable dimer at low concentrations. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 21037–21044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J.D., Wong, S.S., Lieber, C.M., and Lansbury Jr, P.T. 1999. Assembly of Aβ amyloid protofibrils: An in vitro model for a possible early event in Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry 38: 8972–8980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi M., Sato, M., Matsumoto, S., Noguchi, A., Yasutake, K., Yoshida, N., and Sato, K. 2003. Spherical aggregates of β-amyloid (amylospheroid) show high neurotoxicity and activate τ protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 6370–6375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W., Zhang, S., Kamm, R.D., and Karplus, M. 2004. Kinetic control of dimer structure formation in amyloid fibrillogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 12916–12921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R., Head, E., Thompson, J.L., McIntire, T.M., Milton, S.C., Cotman, C.W., and Glabe, C.G. 2003. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science 300: 486–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. and Lee, M. 2004. Observation of multi-step conformation switching in β-amyloid peptide aggregation by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 316: 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.R., Muresan, A., Lee, K.Y.C., and Murphy, R.M. 2004. Urea modulation of β-amyloid fibril growth: Experimental studies and kinetic models. Protein Sci. 13: 2888–2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein W.L., Krafft, G.A., and Finch, C.E. 2001. Targeting small Aβ oligomers: The solution to an Alzheimer's disease conundrum? Trends Neurosci. 24: 219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk W.E., Jacob, R.F., and Mason, R.P. 1999. Quantifying amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) aggregation using the Congo red-Aβ (CR-aβ) spectrophotometric assay. Anal. Biochem. 266: 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer J.J., Pallitto, M.M., Sklansky, D.J., and Murphy, R.M. 2000. Correlation of β-amyloid aggregate size and hydrophobicity with decreased bilayer fluidity of model membranes. Biochemistry 39: 10309–10318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M.P., Barlow, A.K., Chromy, B.A., Edwards, C., Freed, R., Liosatos, M., Morgan, T.E., Rozovsky, I., Trommer, B., Viola, K.L., et al. 1998. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95: 6448–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomakin A., Chung, D.S., Benedek, G.B., Kirschner, D.A., and Teplow, D.B. 1996. On the nucleation and growth of amyloid β-protein fibrils: Detection of nuclei and quantitation of rate constants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93: 1125–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomakin A., Teplow, D.B., Kirschner, D.A., and Benedek, G.B. 1997. Kinetic theory of fibrillogenesis of amyloid β-protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 7942–7947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaurin J. and Chakrabartty, A. 1997. Characterization of the interactions of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptides with phospholipid membranes. Eur. J. Biochem. 245: 355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J.K., Pace, C.N., and Scholtz, J.M. 1995. Denaturant m values and heat capacity changes: Relation to changes in accessible surface areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 4: 2138–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Nuallain B., Shivaprasad, S., Kheterpal, I., and Wetzel, R. 2005. Thermodynamics of Aβ(1-40) amyloid fibril elongation. Biochemistry 44: 12709–12718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace C.N. 1990. Measuring and increasing protein stability. Trends Biotechnol. 8: 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace C.N., Shirley, B.A., McNutt, M., and Gajiwala, K. 1996. Forces contributing to conformational stability of proteins. FASEB J. 10: 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallitto M.M. and Murphy, R.M. 2001. A mathematical model of the kinetics of β-amyloid fibril growth from the denatured state. Biophys. J. 81: 1805–1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellarin R. and Caflisch, A. 2006. Interpreting the aggregation kinetics of amyloid peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 360: 882–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkova A.T., Leapman, R.D., Gui, Z., Yau, W.M., Mattson, M., and Tycko, R. 2005. Self propagation, molecular level polymorphism in Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils. Science 307: 262–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkova A.T., Yau, W.M., and Tycko, R. 2006. Experimental constraints on the quaternary structure in Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry 45: 498–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Alvarado M., Merkel, J.S., and Regandagger, L. 2000. A systematic exploration of the influence of the protein stability on amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 8979–8984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roher A.E., Baudry, J., Chaney, M.O., Kuo, Y.M., Stine, W.B., and Emmerling, M.R. 2000. Oligomerizaiton and fibril asssembly of the amyloid-β protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1502: 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabate R. and Estelrich, J. 2005. Evidence of the existence of micelles in the fibrillogenesis of β-amyloid peptide. J. Phys. Chem. B 109: 11027–11032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivaprasad S. and Wetzel, R. 2006. Scanning cystein mutagenesis analysis of Aβ(1-40) amyloid fibrils. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine W.B., Dahlgren, K.N., Krafft, G.A., and LaDu, M.J. 2003. In vitro characterization of conditions for amyloid-β peptide oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 11612–11622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzi E., Holzemann, G., and Seelig, J. 1997. Interaction of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptide(1-40) with lipid membranes. Biochemistry 36: 14845–14852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng B.P., Esler, W.P., Clish, C.B., Stimson, E.R., Ghilardi, J.R., Vinters, H.V., Mantyh, P.W., Lee, J.P., and Maggio, J.E. 1999. Deposition of monomeric, not oligomeric, Aβ mediates growth of Alzheimer's disease amyloid plaques in human brain preparations. Biochemistry 38: 10424–10431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner P.R., O'Connor, K., Tate, W.P., and Abraham, W.C. 2003. Roles of amyloid precursor protein and its fragments in regulating neural activity, plasticity and memory. Prog. Neurobiol. 70: 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tycko R. 2006. Characterization of amyloid structures at the molecular level by solid state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 413: 103–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D.M., Hartley, D.M., Kusumoto, Y., Fezoui, Y., Condron, M.M., Lomakin, A., Benedek, G.B., Selkoe, D.J., and Teplow, D.B. 1999. Amyloid β-protein fibrillogenesis. Structure and biological activity of protofibrillar intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 25945–25952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D.M., Klyubin, I., Fadeeva, J.V., Cullen, W.K., Anwyl, R., Wolfe, M.S., Rowan, M.J., and Selkoe, D.J. 2002. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 416: 535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.S., Becerra-Arteaga, A., and Good, T.A. 2002. Development of a novel diffusion-based method to estimate the size of the aggregated Aβ species responsible for neurotoxicity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 80: 50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward R.V., Jennings, K.H., Jepras, R., Neville, W., Owen, D.E., Hawkins, J., Christie, G., Davis, J.B., George, A., Karran, E.H., et al. 2000. Fractionation and characterization of oligomeric, protofibrillar and fibrillar forms of β-amyloid peptide. Biochem. J. 348: 137–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlind-Danielsson A. and Arnerup, G. 2001. Spontaneous in vitro formation of supramolecular β-amyloid structures, “betaamy balls,” by β-amyloid 1-40 peptide. Biochemistry 40: 14736–14743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore N.A., Mishra, R., Kheterpal, I., Williams, A., Wetzel, R., and Serpersu, E.H. 2005. Hydrogen deuterium exchange maping of Aβ(1-40) amyloid fibril secondary structure using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry 44: 4434–4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A., Shivaprasad, S., and Wetzel, R. 2006. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of Aβ(1-40) amyloid fibril stability. J. Mol. Biol. 357: 1283–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wogulis M., Wright, S., Cunningham, D., Chilcote, T., Powell, K., and Rydel, R.E. 2005. Nucleation-dependent polymerization is an essential component of amyloid-mediated neuronal cell death. J. Neurosci. 25: 1071–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong W., Lomakin, A., Kirkitadze, M.D., Teplow, D.B., Chen, S.H., and Benedek, G.B. 2002. Structure determination of micelle-like intermediates in amyloid β-protein fibril assembly by using small angle neutron scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 150–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]