Abstract

Bloomfield's “Linguistics as a Science” (1930/1970), Language (1933/1961), and “Language or Ideas?” (1936a/1970), and Skinner's Verbal Behavior (1957) and Science and Human Behavior (1953) were analyzed in regard to their respective perspectives on science and scientific method, the verbal episode, meaning, and subject matter. Similarities between the two authors were found. In particular both asserted that (a) the study of language must be carried out through the methods of science; (b) the main function of language is to produce practical effects on the world through the mediation of a listener; and (c) a physicalist conception of meaning. Their differences concern the subject matter of their disciplines and their use of different models for the analysis of behavior. Bloomfield's linguistics and Skinner's functional analysis of verbal behavior are complementary approaches to language.

Keywords: verbal behavior, Bloomfield's and Skinner's analyses of language, interdisciplinary approach to verbal behavior

Previous reports (Matos & Passos, 2004, 2006; Passos & Matos, 1998) have pointed to the influence of linguistic analyses (mainly the technique of writing, traditional grammar, and structural linguistics1) on Skinner's Verbal Behavior (1957). Two of these influences were Leonard Bloomfield's conceptions of the phoneme and analogy. Other reports have also pointed to the influence of Bloomfield's teaching on Skinner (see, e.g., Joseph, Love, & Taylor, 2001, p. 110; McLeish & Martin, 1975; Passos, 2004, 2007), but the extent of this influence has not yet been fully evaluated. This paper examines more extensively this influence by comparing Bloomfield's and Skinner's formulations on the following topics: (a) the conception of science and of scientific method, (b) the act of speech or verbal episode, (c) meaning, and (d) subject matter. In the evaluation of possible influences, we look especially at four of the major characteristics of Skinner's thinking: (a) verbal behavior as mediated by a listener to be effective on the physical world; (b) the physicalist, as opposed to mentalistic, conception of verbal behavior and meaning; (c) the functional analysis of verbal behavior, with environmental events as the ultimate determinants of verbal behavior; and (d) verbal behavior as operant behavior maintained by its consequences.

The following works were examined: for Skinner, Verbal Behavior (1957), his most important work on the issue of verbal behavior, and Science and Human Behavior (1953); for Bloomfield, the works we found cited by Skinner, namely “Linguistics as a Science” (1930/1970), Language (1933/1961), and “Language or Ideas?” (1936a/1970). (Although Skinner did not cite Bloomfield in Verbal Behavior, he did so in Contingencies of Reinforcement, 1969, p. 11, in his autobiography, 1979, pp. 150, 281–282, and in a paper by Epstein, Lanza, & Skinner, 1980.)

Leonard Bloomfield

Leonard Bloomfield (1887–1949) was a major influence in the shift of linguistics from the historical and comparative study of languages prevalent during the 19th century to the description of the structure of languages in the 20th century. He defined himself as a behaviorist. His work at Ohio University, from 1921 to 1927, put him in close touch with the behaviorist A. P. Weiss (1879–1931), and they greatly influenced each other (Hall, 1990, pp. 23–26). In addition to his intimate knowledge of Weiss' work, whom he deeply admired and frequently cited (Bloomfield, 1930/1970, 1931/1970, 1932/1970, 1933/1961, pp. 512, 515, 1935/1970, 1936a/1970, 1936b/1970, 1942b/1970, 1944/1970), he was also aware of some of Pavlov's, Watson's, and Meyer's writings (Bloomfield, 1932/1970; 1936a/1970).

Coseriu (1986) considers Bloomfield “un lingüista ‘euro-americano’ conocedor de toda la tradición europea y americana … [en quien] confluyen todas las fuentes del estructuralismo” (“a ‘Euro-American’ linguist with expertise in all the European and American tradition … [in whom] flows together all the sources of structuralism”) (p. 149). To Bloomfield, more than to any other of his contemporaries, linguistics owes a certain and explicit methodological orientation: He “was the first to demonstrate the possibility and to exemplify the means of a unified scientific approach to all aspects of linguistic analysis: phonemic, morphological, syntactical; synchronic and diachronic” (Hall, 1950/1970, p. 549).

Bloomfield's contributions were sophisticated and varied. With ample knowledge of the Germanic, Indic, Slavic, and Greek linguistic groups (Bloch, 1949/1970), he made clearly explicit theoretical principles of the study of the Indo-European group of languages, in addition to relating these comparative studies to the plan of general linguistics (Lehmann, 1987). In the field of non-Indo-European languages, his excellent work (Fought, 1999a; Wolff, 1987) on Tagalog in 1917 was the first complete structural description of a language made in American linguistics (Hall, 1990, p. 17). He applied the methods of historical and comparative linguistics to the non-Indo-European Algonquian2 languages, becoming a reference for later studies of these languages (Goddard, 1987) and allowing the questioning of the presumed superiority of Indo-European languages by demonstrating that the same mechanisms of regular phonetic change already established for them were also verified in the indigenous languages of America (Bloomfield, 1919b/1987; Fought, 1999a).

Conceiving of mathematics as having an eminently linguistic nature,3 he illuminated its linguistic foundations by analyzing its discourse as a corpus, as any other set of linguistic data (e.g., a set of texts from a language) (Bloomfield, 1935/1970, 1936b/1970, 1937/1970, 1942b/1970; Hockett, 1970a, 1999). According to Tomalin (2004), his linguistic interest in mathematics evolved from his knowledge of contemporaneous branches of mathematics and the debate over the foundations of this discipline among leading mathematicians, which reveals Bloomfield's wide intellectual scope.

He formulated theoretical and methodological principles based on structural linguistics for the teaching of foreign languages (Bloomfield, 1942, 1945/1970) and didactic material specifically for the teaching of Russian and Dutch (Cowan, 1987). He offered what was probably the first systematic, detailed, and complete application of structural linguistics to the teaching of reading, combining the analysis of the relations between alphabetical writing and speech with the knowledge of the structure of languages in general and of the English language in particular. He specified principles to be followed in the teaching of reading for alphabetical writing regardless of the language, and applied them in a program for English, with ordered lessons, from the first words through full texts (Bloomfield, 1942a/1970; Bloomfield & Barnhart, 19614). Behavior-analytic research on the teaching of reading would greatly benefit from the study of this material (Matos & Passos, 2006).

His textbook Language (1933/1961) treats, among others, the following subjects: history of linguistic studies since antiquity; a physicalist and behaviorist conception of language; speech communities and the various languages and families of languages; descriptive and synchronic linguistics (phonology, meaning, lexicon, and grammar, with syntax and morphology); systems of writing and the role of written records in linguistic inquiries; historical and comparative linguistics; dialectology; and practical applications of linguistic knowledge. Since its publication, the book has been celebrated for the extent and importance of the areas of linguistic knowledge covered, for always presenting the best available information in each of these areas, and for the clarity and order of its exposition (Bolling, 1935/1970; Edgerton, 1933/1970; Kroesch, 1933/1970; Sturtevant, 1934/1970). It continues to be evaluated as an important reference in linguistic studies (Hockett, 1984, 1999; Lepschy, 1982, pp. 84–85). Coseriu (1986) considers the book as important for linguistics as the Cours de Linguistique Générale by de Saussure. He stated that Language

es—por su equilibrio, por su coherencia, por la vastedad y seguridad de la información en que se funda, por la multitud de problemas que toca—el mejor y el más completo tratado de lingüística general que se haya jamás escrito (esto, independientemente de cómo se juzgue la postura teórica de su autor). (is—by its balance, its coherence, the vastness and soundness of the information on which it is based, by the multitude of problems it touches—the best and most complete treatise of general linguistics which has been written ever [this, independently of how the theoretical position of its author is judged]). (p. 149)

Language influenced linguistics deeply and lastingly (Robins, 1997, pp. 237–238). Until the beginning of the 1960s (Koerner, 2003), American linguists followed predominantly a Bloomfieldian orientation, particularly in respect to the methods and techniques of description. Although since the 1960s a good part of linguistics has adopted a predominantly Chomskyan perspective5 (Robins, 1997, p. 260), many linguists remained influenced by Bloomfield (Murray, 1991/1999), and some of them consider his works to be a more valuable source of linguistic knowledge than the ones of any of his successors:

Bloomfield's descriptive linguistics and the system of elements and categories that expressed it had been broken up within his own lifetime by his heirs. Each adopted different subsets of its elements and quietly rejected the rest, while continuing to invoke Bloomfield's name in their works. I have come to believe, however, that it was Bloomfield, not his heirs, who saw farther and more clearly. (Fought, 1999b, pp. 328–329)

Bloomfield's Language and Skinner's Verbal Behavior

Bloomfield's Conception of Science and Scientific Method

Bloomfield's conception of science and of the scientific method shaped his approach to linguistic matters. According to him, physics and biology obtained scientific control over the phenomena that they study because they abandoned teleological pseudoexplanations, the circular reasoning according to which “things happen because there is a tendency for them to happen” (Bloomfield, 1930/1970). Unfortunately, the same did not happen to the human sciences: “In our universe man himself is the one factor of which we have no scientific understanding and over which we have no scientific control” (pp. 227–228). Teleology is widely used in explanations of human actions: A person acted in some way because the person wanted to, or chose to, or had a tendency to. Teleological explanations of human actions are rooted in dualistic conceptions of humans. They assume a mental parallel to the body, a nonphysical entity such as a mind or a will (1930/1970). Auspiciously, the monist conception, which speaks in terms compatible with physics and biology, was taking steps in several disciplines dedicated to the study of language, including linguistics and part of psychology. Bloomfield (1933/1961) identifies two trends in psychology, the dualist–mentalistic and the monist–materialist or mechanistic:

The mentalistic theory … supposes that the variability of human conduct is due to the interference of some non-physical factor, a spirit or will or mind … present in every human being. This spirit … is entirely different from material things and accordingly follows some other kind of causation or perhaps none at all. (p. 32)

The materialistic (or, better, mechanistic) theory supposes that the variability of human conduct, including speech, is due only to the fact that the human body is a very complex system. Human actions … are part of cause-and-effect sequences exactly like those … in the study of physics or chemistry. (p 33)

Bloomfield's embracing of this materialistic theory was the core of his Presidential Address in 1935 to the Linguistic Society of America, which appeared (Hockett, 1970b) in written form as “Language or Ideas?” (1936a/1970) and is one of Bloomfield's works referred to by Skinner (1979, pp. 281–282). As stated by Bloomfield, a path different from the one trod by linguists and behaviorists led the Vienna Circle philosophers to the analogous thesis of physicalism. According to physicalism, scientific statements must be able to be translated into physical terms, in movements that can be observed and described in coordinates of space and time. According to Bloomfield, other branches of science independently achieved the physicalist perspective, as did Pavlov's physiology. In Bloomfield's evaluation, the Vienna Circle and the behaviorists took an advanced position, with consequences for the study of language, by considering false the question of the relation between matter and mind: In scientific formulations, mentalistic terms refer to linguistic events, not to a supposed mentalistic entity. Mentalistic statements subjected to linguistic analysis will be revealed to be statements about language.

The mechanistic perspective of human action pervades the methods of the linguist, who is expected to observe and register carefully the facts of speech and the situations in which they happen, without resorting to that which cannot be observed (1933/1961, p. 38). Because linguistics is an autonomous scientific discipline, the observations must be free from prejudices and independent from philosophical, psychological, and commonsense assumptions (1933/1961, pp. vii–viii, 1, 17, 21–22). Linguistic investigations “will be the ground where science gains its first foothold in the understanding and control of human affairs” (1930/1970, p. 230). The difference that language, “a highly specialized and unstable biological complex” (p. 229), establishes between humans and the rest of life had forbidden the explanation of human actions in terms of biology, and a scientific explanation of language is a necessary step in this direction.6

The linguist studies human speech through the observation of big groups, from which it is possible to extract regularity, because “in no other respect are the activities of a group as rigidly standardized as in the forms of language” (1933/1961, p. 37). The linguist observes, registers, and studies the forms (pp. 37–38). Systematic observation and description of a great number of languages will allow, through inductive generalization, theoretical formulations of general grammar7 (p. 20). The importance of observation and detailed description of linguistic forms is reiterated by Bloomfield (pp. 3, 12, 17, 19–20, 22) and forms the basis of his admiration of Pānini's8 grammar of Sanskrit, which is revealing of his conceptions of science:

This grammar … is one of the greatest monuments of human intelligence. It describes, with the minutest detail, every inflection, derivation, and composition, and every syntactic usage of its author's speech. … The Indian grammar presented to European eyes, for the first time, a complete and accurate description of a language, based not upon theory but upon observation. (p. 11)

Skinner's Conception of Science and Scientific Method

According to Skinner (1953, pp. 4–5, 13–14, 1957, p. 459), in natural sciences the assumption of determinism and its possibilities of manipulation and control allowed humans to have great power over the natural world. “Unique in showing a cumulative progress” (1953, p. 11), science, taking human behavior as a subject matter, will allow humans to make a better use of the knowledge already gained over other objects (1953, p. 5, 1957, pp. 459–460). The adoption of the methods of natural sciences by human and social sciences presupposes the acceptance of determinism, the belief that events are regularly related (1953, pp. 6–8), as “a working assumption which must be adopted at the very start” (p. 6). The identification of regular relations will allow one to predict and control phenomena, that is, to produce them by manipulating the antecedent events regularly related. Verbal Behavior, by specifying the determinants of each type of verbal operant, represents Skinner's full statement that verbal behavior is also determined (1957, pp. 175, 228).

Scientific knowledge draws general rules from the observation of isolated facts. These general rules, scientific laws, later become organized in wider arrangements (Skinner, 1953, pp. 13–14, 18–19). A functional relation, the general rule or scientific law (p. 35), is the modern version of the old cause-and-effect relation (p. 23). In the case of psychology, it consists of one or more independent variables, located outside the organism (pp. 31, 35), whose variation results regularly in the variation of the dependent variable that represents the subject matter, the probability of occurrence of the behavior of the individual organism (pp. 19, 32). Although phenomena that occur inside the organism, studied by neurology and physiology, do mediate the relations between behavior and environment, a science of behavior searches for regular relations between them and is independent from both neurology and physiology (pp. 28, 34–35, 281).

To be susceptible to measurement and manipulation, the independent variables functionally related to behavior must have physical (spatial-temporal) dimensions, be located in the external environment of the organism, and occur before the dependent variable (1953, pp. 31, 35, 1957, pp. 462–463). The dependent variable, the behavior itself, also has physical dimensions and does not have special properties that require methods of investigation different from scientific ones (1953, pp. 35–36). These requirements can be called Skinner's physicalism, environmentalism, and antiteleologism (p. 51). The scientist's physicalist conception of the world is omnipresent in Skinner's work. From the subject matter (behavior) to its controlling variables (stimuli or properties of stimuli), including the private world (1957, pp. 130ff), everything offers itself to scientific inquiry through its physical nature. Skinner's environmentalism is seen in his view that the variables of which behavior is a function are located in the organism's immediate environment and environmental history (1953, p. 31). Skinner stresses that social sciences and psychology started to turn to the external determinants of action (1957, pp. 458–459). His antiteleologism appears in the concept that all independent variables related to behavior are in the history (immediate and remote) of the organism, thus preceding the dependent variable. Selection by consequences is not a teleological explanation of behavior, because the reinforcing consequence will strengthen responses to be emitted after, not before, it. The determinism encompassed in selection by consequences has the same nature that we find in natural selection and, in both cases, it is not teleological (pp. 462–463).

Bloomfield's and Skinner's conceptions of science and scientific method are very similar. Both emphasize:

The unity of science (human and social sciences must be like natural science). Linguistics and psychology, for Bloomfield, and psychology, for Skinner, are sciences.

The necessity of scientific control over the objects created in human cultures to benefit society with better uses of the power gained through natural sciences.

The search by social sciences and psychology for the determinants of human actions in agents that are external to behavior.

The independence of their respective disciplines. Linguistics, for Bloomfield, and psychology, for Skinner, should not ask other disciplines for explanations of their subject matter.

Physicalism as the necessary form of discourse for any science and the physicalist concept of the subject matter of linguistics and psychology.

The determinism that governs human actions, including language.

The rejection of teleological explanations of human action.

The inadequacy for science of the dualistic conception of world as well as of any kind of associated mentalism.

Observation is prior to theorizing and has a central role in the building of scientific knowledge.

The importance of inductive methods.

Bloomfield's Act of Speech

Bloomfield's act of speech, already mentioned by Skinner in 1934 (1979, p. 150; see also Epstein et al., 1980), illustrates the basic function of language, which is to produce practical effects in the world:

Suppose that Jack and Jill are walking down a lane. Jill is hungry. She sees an apple in a tree. She makes a noise with her larynx, tongue, and lips. Jack vaults the fence, climbs the tree, takes the apple, brings it to Jill, and places it in her hand. Jill eats the apple. … the incident consists of three parts, in order of time:

A. Practical events preceding the act of speech.

B. Speech.

C. Practical events following the act of speech. (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, pp. 22–23)

A is the speaker's stimulus (S): the stimuli arising from Jill's hunger; the light waves reflected by the apple that reach her eyes; her sight of Jack; her past interactions with him. B is speech itself, the source of the linguist's data, integrated by the speaker's reaction to S by means of speech, the transmission through the air of the sound waves produced by it, and the listener's reaction to the sound waves that reach his ears (pp. 23–25). C is related to both the listener—Jack takes the apple and gives it to Jill—and to the speaker, “in a very important way: She gets the apple into her grasp and eats it” (p. 23).

The speaker has two ways of reacting to practical stimuli9:

S→R (practical reaction)

S→r (linguistic substitute reaction) (p. 25)

The listener can react to both practical and linguistic stimuli:

(practical stimulus) S→R

(linguistic substitute stimulus) s→R (p. 25)

The speaker's substitute linguistic reaction to a nonlinguistic stimulus is complemented by the listener's practical reaction to a linguistic substitute stimulus:

S→r…….s→R (p. 26)

The term substitute is a reference to the learned nature of the speaker's and listener's reactions that involve language. There is nothing special in the mechanisms involved in the speaker's linguistic substitute reaction or in the listener's practical reaction to linguistic stimuli. They are “a phase of our general equipment for responding to stimuli, be they speech-sounds or others” (p. 32). Linguistic reactions are not different, in nature, from practical reactions, but their advantage is that “Language enables one person to make a reaction (R) when another person has the stimulus (S)” (p. 24).

The S-R symbolism used by Bloomfield, following the behaviorists of his time, carries an assumption on the type of causality involved in the determination of behavior, which is thought to be a function of antecedent stimuli. There is no place in the model for stimuli that succeed behavior, the ones called “consequences” of behavior by Skinner. A scientific model needs to represent all the relevant aspects of the situation under analysis. A comparison of both the analyses made by Bloomfield of the act of speech, one in common language and the other symbolized in the S-R model, shows that (a) the specifications related to the speaker's stimulus and the listener's practical and linguistic stimuli are represented in the model by S and s, and (b) the double possibility of reaction by the speaker to practical stimuli and the listener's reaction to practical and linguistic stimuli are represented in the model by R and r. The model leaves without representation an element of the analysis made in common language, which Bloomfield himself calls very important: the practical events that succeed acts of speech in their effects on the speaker. So, although Bloomfield used a Pavlovian paradigm, he expanded it by adding a new component: consequences (Stage C), which play an important part in the act of speech.

Skinner's Verbal Episode

The speech episode (Skinner, 1957, p. 36) or verbal episode (p. 33) is a paradigm of what happens in verbal interactions. It identifies the speaker's and listener's behavioral events as well as the arrangement of these events in a specific temporal order (p. 36). In the example of a mand, the speaker emits the verbal behavior “bread, please.” The listener offers the bread to the speaker, who takes the bread and says “thank you” to the listener, who finally answers with “you're welcome” (p. 37). This verbal episode is constituted by (a) the speaker's deprivation; (b) the nonverbal stimuli, mainly the two participants and the bread; (c) the units of verbal behavior “bread, please,” “thank you,” “you're welcome”; (d) the verbal stimuli that result from these units of verbal behavior; (e) the nonverbal behavior of the listener of passing the bread. The verbal responses “thank you” and “you're welcome” are generalized reinforcers that maintain, first, the nonverbal behavior of the listener of reinforcing the mand and, second, the speaker's verbal behavior of presenting this generalized reinforcer that maintains the behavior of the listener. In the listener's behavior of passing the bread, the reinforcer specified by the mand, Skinner locates the consequence that maintains verbal behavior (p. 37).

There are many similarities between Bloomfield's act of speech and Skinner's verbal episode:

Both are physicalist analyses of a verbal interaction according to elements relevant to a functional analysis of behavior, comprising the antecedents (deprivation and stimuli) and the consequences (reinforcers presented by a listener) of behavior.

Both present the same basic structure, consisting of two human organisms, whose behavior is under control of deprivation or stimuli presented by their verbal and nonverbal environment.

Both conceptualize verbal behavior as occurring because of the practical results it produces due to the participation of a listener, demanding interaction between the organisms.

Both identify environmental and behavioral elements (response, deprivation, and stimulus) that are part of the verbal episode, as well as the temporal order in which they occur.

An important difference between Bloomfield's act of speech and Skinner's verbal episode is in their theoretical conceptions of the functional relations between the stimuli and the responses that they control. For Bloomfield, the relation between antecedent stimuli and speech, as well as between verbal stimuli generated by speech and the reaction of the listener to them, is made possible by the mechanism of substitution, found in the Pavlovian model of reflexes (Skinner, 1953, p. 53). For Skinner, the relation between speech and environmental events characterizes operant behavior. The antecedent events in control of verbal behavior are deprivation and discriminative stimuli that control the emission, not the elicitation, of responses.

The theoretical model—the three-term contingency—that furnishes the elements for Skinner's analysis of the verbal episode represents better than the Pavlovian model the relations between stimuli and responses that, in the case of verbal behavior, do not present the quantitative properties of reflexes (Skinner, 1953, pp. 53–54). By conceiving of verbal behavior as operant behavior, Skinner (a) establishes its consequences as its most important determinant; (b) differentiates the operant and respondent (reflexive) effects produced by verbal behavior in the listener (pp. 29–30); (c) details several variables involved in the control of verbal behavior, allowing the explanation of very specific characteristics of verbal behavior (e.g., discriminative control explains why a set of different objects evokes the same name in extension, pp. 91ff, and why part of a verbal response is under control of nonverbal stimuli while another part falls under the control of verbal stimuli, pp. 185–187; generalized reinforcement elucidates how the verbal community is able to establish most verbal operants in the absence of specific deprivation, pp. 53–54, and shaping clarifies how the initial vocalizations of a child become gradually more and more similar to the pattern demanded by the community, pp. 59–60, 203–204). The approach is very parsimonious in the sense that the same concepts and mechanisms account for both verbal and nonverbal behavior. In brief, the three-term contingency used by Skinner allows him to differentiate verbal operants, the mechanisms for establishing them, and the listener's behavior of presenting consequences for the speaker's verbal behavior (pp. 36–37, 56–57, 67, 85–86). It is a powerful analytical instrument because it specifies very clearly the elements needed to be identified and manipulated, as well as the order in which one must manipulate them, if one wants to produce the speaker's verbal behavior and the listener's behavior of presenting consequences.

Bloomfield's Conception of Meaning

Bloomfield criticized mentalistic conceptions of meaning as “a non-physical process, a thought, concept, image, feeling, act of will” (1933/1961, p. 142) that happens inside the speaker preceding the emission of the form, and of language as “the expression of ideas, feelings, or volitions” (p. 142). For Bloomfield, the meaning of a statement is not contained in the statement itself. Instead, it is connected to the practical events that precede and follow it, related both to the speaker and to the listener: “speech-utterance, trivial and unimportant in itself, is important because it has a meaning: the meaning consists of the important things with which the speech-utterance (B) is connected, namely the practical events (A and C)” (p. 27).

A and C refer to each aspect of the world to which a speaker can react by means of speech (including the stimuli arising from his or her own body) as well as to the listener's reactions to the speaker's speech: “A and C make up the world in which we live” (1933/1961, p. 74). The continuum of the world (e.g., the color spectrum seen by physicists as a continuum scale) is divided in different ways by different languages in arbitrary and imprecise ways (e.g., red, orange, yellow, etc.) (p. 140). The meaning of a linguistic form is arbitrarily related to it, their linkage residing in the community's linguistic habits (pp. 140–141, 144–145). The stimulus situations in which a speaker emits the same linguistic form (e.g., apple) share some but not all features. The speaker is trained to utter this speech form in the presence of the common features, and these distinctive features constitute the meaning of this linguistic form. The other features of the situation are its nondistinctive features:

We must discriminate between non-distinctive features of the situation, such as the size, shape, color, and so on of any one particular apple, and the distinctive, or linguistic meaning (the semantic features) which are common to all the situations that call forth the utterance of the linguistic form, such as the features which are common to all the objects of which English-speaking people use the word apple. (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, pp. 140–141)

Bloomfield's physicalist conception of meaning together with his insistence on the difficulty of its scientific study because of the complexity of A and C (pp. 160–162, 167, 172, 208, 227, 246, 248, 266–268, 271, 276) were frequently misunderstood as excluding meaning from consideration (Bloomfield, 1945/1987; Fought, 1999a, 1999b; Hall, 1990, pp. 47–48; Hockett, 1999). For Bloomfield, linguistic forms are the material with which linguists work and are identified with the aid of meaning, although linguists do not have a scientific method to analyze meaning.

Skinner's Conception of Meaning

“Meaning,” “ideas,” “images,” “information,” “feelings,” “desires” (Skinner, 1957, pp. 5–8) are presumed events internal to the organism that constitute pseudoexplanations of verbal behavior and move the researcher away from the environmental variables that are effectively related to it (pp. 7, 9–10). The explanation of verbal behavior by means of these “causes” violates the principles required in a scientific explanation by pointing to something that does not have physical dimensions, as well as because of its circularity (1953, pp. 29–31). Although it is possible to redefine them in a scientifically acceptable way, Skinner opts for their abandonment, given the risk that the terminology will carry with it the old conceptions inadequate for a scientific analysis (1957, pp. 9–10). The “causes” of verbal behavior must respect the requirement of physicalism and be located outside the organism, clearly distinguishable from the behavior that they explain. Meaning “is not a property of behavior as such but of the conditions under which behavior occurs. Technically, meanings are to be found among the independent variables in a functional account, rather than as properties of the dependent variable” (1957, pp. 13–14).

The variables that determine the forms of verbal operants are the ones that approximate traditional10 meaning. With the mand, the deprivation or the aversive stimulus and the reinforcement specified by the mand are the correlates of what is often called meaning (Skinner, 1957, pp. 43–44). The innumerable nonverbal discriminative stimuli that can control the tacts are closer to what is usually considered to be the “meaning expressed by the speech form.” They constitute

the whole of the physical environment—the world of things and events which a speaker is said to “talk about.” Verbal behavior under the control of such stimuli is so important that it is often dealt with exclusively in the study of language and in theories of meaning. (p. 81)

The speaker's repertoire of tacts corresponds to the specific and arbitrary way that a given community analyzes the nonverbal world. Control of the response forms by stimuli or properties of stimuli has occurred in a way that was not planned, and there is no apparent logical necessity by which some and not other stimuli or properties of stimuli have acquired control over the forms.

If the world could be divided into many separate things or events and if we could set up a separate form of verbal response for each, the problem would be relatively simple. But the world is not so easily analyzed, or at least has not been so analyzed by those whose verbal behavior we must study. In any large verbal repertoire we find a confusing mixture of relations between forms of response and forms of stimuli. The problem is to find the basic units of “correspondence.” (Skinner, 1957, p. 116)

The operant is always a relation between classes of responses and classes of stimuli or properties of stimuli. Stimulus control presents variations that correspond to the variation of the occasioning stimuli, always in some way different from each other, because a verbal response was reinforced in the presence of a certain instance of a stimulus or a property of a stimulus. Moreover, stimuli on which reinforcement was not contingent but that, nonetheless, were present on the occasion of the reinforcer can acquire control over a tact. Thus, because different stimuli share certain properties, a new stimulus that possesses a property shared by another stimulus in the presence of which a response was reinforced can show control over the response. Skinner refers to these difficulties in terms of imprecise stimulus control (pp. 91ff).

The analysis of the stimuli of the physical world made by physics does not offer a solution for the identification of the stimuli that control tacts, because the properties of nature that are relevant for the analysis made by physics do not necessarily have a correspondence with the properties connected to the previous reinforcement of tacts by the verbal community:

The properties of nature which come to control verbal behavior are more numerous and complex than those covered in the accounts provided by physics, because verbal behavior is controlled by many temporary, incidental, and trivial characteristics which are ignored in a scientific analysis. (Skinner, 1957, p. 123)

We find many similarities between Bloomfield's and Skinner's conceptions relative to meaning:

Both criticize mentalistic conceptions of meaning as a nonphysical process—as “ideas,” “images,” “feelings,” “desires”—that would occur in the speaker, would be expressed by the verbal emission, and would correspond with a similar process occurring in the listener. These would be circular explanations of speech.

Both present a physicalist conception of meaning, which consists of the antecedent and consequent events to which speech is related.

Both consider these events of the world, including sounds produced by speech, as complex situations whose analysis by the linguist or the behavior analyst is very difficult.

Both understand that the analysis of the world made by language is arbitrary, corresponding to the conventions adopted by the verbal community, based on a partitioning of the world that does not necessarily coincide with the partitions made by sciences.

Also, we can notice how Bloomfield's conception of distinctive features of meaning is similar to Skinner's conception of the control of behavior by properties of the stimulus. Both of these conceptions refer to elements common to several situations in which the speech form or verbal behavior appears and how these common elements take control over the speech form. A difference between the two authors is that Skinner avoids using the term meaning.

Bloomfield's Subject Matter

For Bloomfield, linguistics does not establish value judgments on its subject matter; it is not the study of correct or elegant speech, or of literature. It also does not take writing as its main reference (1933/1961, pp. 21–22, 496–500). All speech forms must be considered and are part of the material of interest for linguistic investigation. The study of the speech of individuals is the way through which the linguist investigates the language of a community, that is, the features that are common to the speakers (pp. 22, 75). The unique way each person uses linguistic forms respects the conventions that are effective in the group, that is, the person's utterances will contain the forms and sequences of forms in use in the verbal community (pp. 37, 75).

The linguist observes acts of speech specifically to address Part B, the speech itself, the product of the linguistic substitute reaction of the speaker that functions as the linguistic substitute stimulus to which the listener reacts (pp. 24–26). The aim is to identify the linguistic forms with the aid of the stimuli and reactions that constitute meaning (pp. 26–27, 74–78). Linguistics has a methodological assumption that is also a logical requirement for the functioning of language: There is stability in the relations between linguistic forms and meaning (pp. 144–145).

Language is a universal human activity, realized in different ways in different groups (1933/1961, pp. 42ff): “The particular speech-sounds which people utter under particular stimuli, differ among different groups of men; mankind speaks many languages” (p. 29). The linguist studies the speech habits of communities (p. 37), the languages of the world (pp. 57ff). Although other animals use vocal signals as humans do, the difference between them lies in the greater complexity of languages. A language is a system of signaling, consisting of several signs—linguistic forms—by which speakers and listeners interact. Linguistic forms are combinations of units of signaling—phonemes—that occur in each language in limited number and combinations (p. 158). The system of linguistic forms is the language. The signaling of any meaning in a language is always made by means of a physical signal, that is, by formal features (lexical and grammatical): “a language can convey only such meanings as are attached to some formal feature: the speakers can signal only by means of signals” (p. 168).

The lexical and grammatical smallest units of signaling to which meanings are connected—the morphemes and tagmemes, respectively (pp. 161, 166)—are the resources offered by any language to its speakers and listeners: “The power or wealth of a language consists of the morphemes and the tagmemes (sentence-types, constructions, and substitutions). The number of morphemes and tagmemes in any language runs well into the thousands” (p. 276). The linguist assumes that the language is a structure (p. 281) of phonemic, lexical, and grammatical habits:

We suppose that language consists of two layers of habit. One layer is phonemic: the speakers have certain habits of voicing, tongue-movement, and so on. These habits make up the phonetic system of the language. The other layer consists of formal-semantic habits: the speakers habitually utter certain combinations of phonemes in response to certain types of stimuli, and respond appropriately when they hear these same combinations. These habits make up the grammar and lexicon of the language. (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, pp. 364–365)

Bloomfield tried to establish a method that allowed the identification of the phonological, lexical and grammatical units of the languages. At each of these levels, he identifies linguistic units of different sizes and considers the bigger ones as combinations of the smaller ones (pp. 128ff, 138, 264).

Skinner's Subject Matter

Verbal behavior is a special kind of operant behavior. Through it, “a man acts only indirectly upon the environment from which the ultimate consequences of his behavior emerge. His first effect is upon other men” (Skinner, 1957, p. 1). The relations that the properties or dimensions of nonverbal operant behavior have with the effects it produces in the environment are described by mechanical and geometrical principles, whereas the properties or dimensions of operant verbal behavior are related to the effects that it produces in a listener who was conditioned by the verbal community to be a mediator between the verbal behavior of the speaker and its consequence (pp. 1, 224–226). The effect achieved on the listener depends on the form of the verbal response, and the relation between the conditions of emission of any specific form and the reinforcement by the listener is kept stable among the verbal community:

The ultimate explanation of any kind of verbal behavior depends upon the action which the listener takes with respect to it. Effective action requires a verbal stimulus which is “intelligible” in the sense of loud and clear and which stands in a reasonably stable relation to the conditions under which it is emitted. (Skinner, 1957, p. 314)

A functional analysis of verbal behavior searches for the independent variables that control the verbal behavior of the individual speaker in a concrete interaction with the listener, in a specific and known environment, because the isolation of verbal behavior from the situations in which it had been produced obscures the functional relations relevant for its explanation. Verbal behavior, as speaking, writing, or gesturing, consists of muscular responses. In the case of vocal verbal behavior, the type most studied in Verbal Behavior, muscular responses produce an audible sound by means of which verbal behavior is effective. This sound is the datum for the behavior analyst (pp. 14–15).

Linguistic units of several sizes—words, roots, affixes, morphemes, phrases, idioms, sentences—can be studied by the behavior analyst, because “any one of these may have functional unity as a verbal operant” (Skinner, 1957, p. 21). However, Skinner clearly states the distinctiveness of the behavior analyst's approach, directed toward the analysis of the verbal behavior of the individual speaker, whose functional units should not be confused with the functional units found in the practices of a verbal community (p. 21). Verbal behavioral units are identified by the functional relations that parts of verbal behavior have with the environment (pp. 13ff). The typology of Skinner's verbal operants is based on the identification of the antecedent conditions (deprivation, aversive stimuli, discriminative stimuli) and of the consequences (reinforcement, punishment, extinction) that the verbal community makes contingent on each verbal operant (pp. 28ff).

Subject matter is the issue that most strongly distinguishes Skinner's functional analysis of verbal behavior from Bloomfield's linguistic analysis of language. According to Bloomfield, linguists study the speech habits of a community (p. 29)—the languages (p. 29), the structure of phonemic, lexical, and grammatical habits (p. 31)—but not the language of the individual (1933/1961, p. 75). The linguist studies and describes what is common to the verbal behavior—the system of linguistic forms in use—by the whole verbal community. The objective is not to predict the verbal behavior of any individual in particular (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, pp. 37, 75); thus, it is not centered on the peculiarities or in the repertoire of the speech of the individual (p. 22). These items that lie outside the realm of the linguist exactly constitute the behavior analyst's realm. Skinner (1957) acknowledged the different subject matter.

The “languages” studied by the linguist are the reinforcing practices of verbal communities. When we say that also means in addition or besides “in English,” we are not referring to the verbal behavior of any one speaker of English or the average performance of many speakers, but to the conditions under which a response is characteristically reinforced by a verbal community. … In studying the practices of the community rather than the behavior of the speaker, the linguist has not been concerned with verbal behavior in the present sense. … A functional analysis of the verbal community is not part of this book. (p. 461)

Yet, a few very important similarities are also found between the two authors views on subject matter:

Verbal behavior is not different in nature from other behavior of the organism. What specifies verbal behavior is the role of the listener who acts in a practical way.

Verbal behavior is learned. What makes the speaker utter verbal behavior and the listener react to it in an appropriate manner is the training provided to both by their verbal community.

There is a considerable, although relative, stability in the relations between forms of speech and meaning, and this stability is a requirement for the functioning of language.

Conclusion

The four major characteristics of Skinner's thinking will guide our final remarks.

Verbal Behavior Is Mediated by a Listener to Be Effective on the Physical World

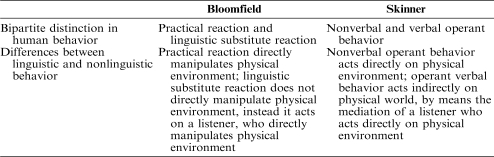

This essential part of Skinner's thinking leans on the same kind of elements and distinctions through which Bloomfield established the basic difference between human reactions that involve language from ones that do not, as is shown in Table 1. Skinner additionally clarifies the critical difference that defines the bipartition: Whereas nonverbal responses are reinforced according to the mechanical and geometrical relations that their properties have with the environment, verbal responses are reinforced through the mediation of a listener whose reinforcing behavior was taught by the verbal community.

Table 1.

Bloomfield's and Skinner's conception of linguistic and nonlinguistic behavior

The Physicalist, as Opposed to the Mentalistic, Conception of Verbal Behavior and Meaning

The physicalist conception of meaning is a hallmark of Bloomfield's linguistics. This equally essential aspect of Skinner's thinking does not represent a new formulation of meaning; instead it shows continuity with Bloomfield's tradition.

The Analysis of Verbal Behavior as Being Essentially A Functional Analysis, With Environmental Events as the Ultimate Determinants of Verbal Behavior

Bloomfield's critique of teleology together with his understanding of meaning as located in the environmental events that surround speech go in the direction of a functional analysis of language. However, as we saw, his objective was not an analysis of the repertoire of the individual speaker, but the description and analysis of the system of linguistic forms in a given verbal community, made through the observation of the situations in which the forms are uttered and the effects they evoke in the listener (i.e., according to functional criteria).

The specification of the repertoire of the individual speaker as a subject matter, as well as the formulation of theoretical and methodological instruments for its analysis, is original to Skinner. The detailing of various kinds of verbal operants, differentiated by means of their elements, together with the nature of the functional relations involved in each one of them, is a truly unique and remarkable contribution by Skinner to the field of language. There was no previous model for them in Bloomfield or in any other author before his formulation.

Verbal Behavior as Operant Behavior, Maintained by Its Consequences

The role of the consequence in the emission of verbal behavior was stressed by Bloomfield, even though the Pavlovian model that he used to analyze behavior and conditioning had no place for this element. It is worth noting that the shortcomings of this model do not interfere with his linguistic analysis, because his objective was not to study the individual speaker's verbal behavior or to study the processes that develop verbal operants.

Skinner assigns a place for consequences in his theoretical model of the operant contingency and specifies its relation to the other elements of it—deprivation, antecedent stimuli, and the verbal response itself. In doing so, he sets the procedures to be followed to both explain and develop the verbal behavior of the individual speaker.

Skinner's contributions to the field of language that we find to be original in relation to those of Bloomfield's previous conceptions (and, it seems, in relation to those of other authors as well) are related to their differences with respect to subject matter. Although different, there is a strong connection between the conceptions of Bloomfield and Skinner. Language, the structure of phonemic, lexical, and grammatical habits of a speech community as conceived by Bloomfield, is an abstract object built from the observations and analysis of specific instances of speech in one speech community. Verbal behavior is conceived of by Skinner as operant behavior whose reinforcement is mediated by a listener. Operant behavior is also an abstraction, a scientific construction, built from the observation of specific instances of behavior of one speaker. The connection of their subject matter comes from the fact that the listener reinforces verbal behavior according to the practices of the verbal community, or as Bloomfield put it, according to the structure of phonemic, lexical, and grammatical habits found in the verbal community.

These key similarities between the two authors could have come about in more than one way. They could reflect predominant diffuse conceptions at the time rather than any direct influence of one author on the other. It is possible that this is the case for some of their similarities. Both authors could have had one or more common influences, making what seems at first glance to be the influence of one on the other to be, in the end, a common influence exerted by a third author on both. This could be the case for their similar views of science and scientific methods. It would be interesting to investigate to what extent certain of Bloomfield's and Skinner's formulations appeared previously in Weiss, an author who exerted a recognized influence on Bloomfield and who is referred to by Skinner in Verbal Behavior (1957, p. 101).

However, the similarities related to properly linguistic questions can be seen as a direct influence of Bloomfield on Skinner. Previous works have pointed to similarities that belong in this category, such as Skinner's use of the model of analogy (Matos & Passos, 2004), his understanding of the phoneme and the method for the identification of the phonemes of languages (Joseph et al., 2001, p. 110; Matos & Passos, 2006; Passos & Matos, 1998), the ways of recording verbal behavior, and the conceptions of meaning and verbal episode (Matos & Passos, 1999; Passos, 2004; Passos & Matos, 1998). The similarities in this paper that can be seen as a direct influence are the conceptions of meaning, the verbal episode, and the subject matter of linguistics.

These similarities, and above all the connection of their respective subject matter, direct us to the theme of interdisciplinary work on language. Because the speaker's behavior results from the reinforcing practices of the verbal community, linguistic analysis of these practices is a logical and practical prerequisite for the analysis of this behavior. In fact, behavior analysts have been using linguistic descriptions (from traditional grammar or linguistics, or both) of the practices of the verbal community when working on their subject matter, the repertoire of the speaker (Matos & Passos, 2006). Thus it is important to acknowledge the existence of different linguistic descriptions of different aspects of the practices of the verbal community, as well as different linguistic descriptions of the same aspects of these practices as, for example, the descriptions of traditional grammar and the ones of structural linguistics. These different descriptions do not all have the same value; some are better or more useful for some aspects of the verbal behavior under consideration than others.

The scientific principles of Bloomfield's and Skinner's analyses are very similar, and in both cases these analyses effectively respect their principles. Analyses and descriptions of the practices of verbal communities made according to the tradition of Bloomfield's linguistics can be very useful in a functional analysis of verbal behavior.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on my PhD thesis, A Lingüística Estrutural de L. Bloomfield e a Análise Funcional do Comportamento Verbal de B. F. Skinner: Algumas Relações (L. Bloomfield's Structural Linguistics and B. F. Skinner's Functional Analysis of Verbal Behavior: Some Relations), directed by Maria Amelia Matos and presented at the Departamento de Psicologia Experimental, Universidade de São Paulo, in 1999. Maria Amelia Matos unfortunately died in 2005. McIlvane (2006) and Tomanari (2006) give two sensitive descriptions of her life and work. I am very grateful for having had her as a wonderful adviser and friend.

I thank David Eckerman and Fatima Pires who, being close to Maria Amelia both professionally and personally, agreed to read and comment on the final draft of the manuscript, and gave to me so many valuable suggestions.

Footnotes

Structural linguistics is the main trend in linguistics since the beginning of the 20th century (Lyons, 1981, pp. 218ff; Robins, 1997, p. 225). It conceives of a language as a structure, a systematic arrangement of units (certain combinations between them occur, while others do not occur) at the lexical, phonological, morphological, and syntactic levels. The units of the language are defined not by considering each one by itself, but by the relations that each one has with the others and by the differences between them. The linguist identifies and describes the units of the languages and the combinations in which they occur (Benveniste, 1971, pp. 79ff; Robins, 1988, p. 480, 1997, pp. 224–225). In a more restricted sense, not the one used in this paper, structural linguistics refers just to the linguistics of Bloomfield and his followers (Lepschy, 1982, p. 110; Robins, 1997, p. 239).

Algonquian comprises several Indian languages from Canada and the United States (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, p. 72).

According to Weiss (1929), “The conception of mathematics as an ideal language should be credited to Professor Leonard Bloomfield” (p. 14).

This work (Bloomfield, 1961), written during the 1930s, was published only in 1961, after its author's death, in the book Let's Read. The circulation of the manuscript among linguists influenced the elaboration of other works dedicated to the teaching of reading as Improving Your Reading in 1943 by Henry L. Smith, Jr. (1963) and Linguistics and Reading (1962) by Charles C. Fries. Bloomfield's system was tested, successfully, during the 1940s (Barnhart, 1961).

Although very different from Bloomfield's, Chomsky's linguistics also has its roots in Bloomfield's linguistics, as was pointed out incisively by some historians of linguistics (see, e.g., Fought, 1999b; Koerner, 2003; Lopes, 1997, p. 267; Matthews, 1986).

According to Bloomfield (1930/1970, 1931/1970), this hypothesis comes from Weiss, the first to understand the meaning of language, in the sense of substituting mentalistic explanations of human behavior by explanations based on language.

General grammar studies what is common to all languages (Auroux, 1992, p. 88), and includes basic issues such as “how language works, where it came from, how it relates to other aspects of human conduct” (Hockett, 1984, p. x). It refers to the universal applicability of linguistic theory and method to the study of languages, seen from theoretical, descriptive, and comparative perspectives (Crystal, 1980, p. 159).

Pānini (circa 6th century B.C., India) (Rogers, 1987) was the author of the most ancient scientific work written in any Indo-European language (Robins, 1997, p. 178), the most ancient grammar of Sanskrit that reached us (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, pp. 10–11). As early as 1919 (1919a, p. 41) Bloomfield refers to Pānini as his model for linguistic description.

In this and the following diagrams, the arrows symbolize the sequence of events, property of the nervous system, in the body of the speaker or the listener, and the dotted lines, sound waves (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, p. 26).

Skinner does not specify what were included in the formulations he calls “traditional” (1957, p. 3). Meaning is a term of ample use, be it in a technical sense (as in linguistics, philosophy, and other disciplines) or in a nontechnical sense (in the common language). Certainly there are many differences among the usages in different technical fields, different authors of one same area, and common language.

References

- Auroux S. A revolução tecnológica da gramatização [The technological revolution of grammatization] (E. P. Orlandi, Trans.) Campinas, Brazil: Editora da Unicamp; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart C.L. The story of the Bloomfield system. In: Bloomfield L, Barnhart C.L, editors. Let's read; a linguistic approach. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press; 1961. pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste E. Problems in general linguistics (M. E. Meek, Trans.) Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch B. Leonard Bloomfield. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 524–532. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Letter to T. Michelson. In letters from Bloomfield to Michelson and Sapir, edited by C. F. Hockett (pp. 40–41). In: Hall R.A Jr, editor. Leonard Bloomfield: Essays on his life and work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1919a. pp. 39–60. (1987), [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Letter to E. Sapir. In letters from Bloomfield to Michelson and Sapir, edited by C. F. Hockett (pp. 49–50). In: Hall R.A Jr, editor. Leonard Bloomfield: Essays on his life and work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1919b. pp. 39–60. (1987), [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Outline guide for the practical study of foreign languages. Baltimore: Linguistic Society of America; 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Letter to J. M. Cowan. In J. Milton Cowan, The whimsical Bloomfield. In: Hall R.A Jr, editor. Leonard Bloomfield: Essays on his life and work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1945. pp. 23–37.pp. 23–37. (1987), [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Language. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Teaching children to read. In: Bloomfield L, Barnhart C.L, editors. Let's read: A linguistic approach. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press; 1961. pp. 19–42. (Ed. by Barnhart of 1940 typescript) [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Linguistics as a science. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Albert Paul Weiss. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 237–239. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Lautgesetz und Analogie, by Eduard Hermann [Review]. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Linguistic aspects of science. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 307–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Language or ideas? In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 322–328. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Linguistic analysis of Mathematics, by A. F. Bentley. Behavior, knowledge, fact, by A. F. Bentley [Review]. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. The language of science [Fragments]. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Linguistics and reading. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 384–395. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Philosophical aspects of language. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 396–399. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Secondary and tertiary responses to language. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. About foreign language teaching. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 426–438. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L, Barnhart C.L. Let's read: A linguistic approach. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Bolling G.M. Language, by L. Bloomfield. [Review]. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 277–278. [Google Scholar]

- Coseriu E. Lecciones de lingüística general [Lessons on general linguistics] Madrid: Gredos; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan J.M. The whimsical Bloomfield. In: Hall R.A Jr, editor. Leonard Bloomfield: Essays on his life and work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1987. pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal D. A first dictionary of linguistics and phonetics. London: Andre Deutsch; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton F. Language, by L. Bloomfield. [Review]. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 258–260. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Lanza R.P, Skinner B.F. Symbolic communication between two pigeons (Columba livia domestica). Science. 1980;207:543–545. doi: 10.1126/science.207.4430.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fought J. Introduction. In: Fought J, editor. Leonard Bloomfield: Critical assessments of leading linguists: Vol. 1. Biographical sketches. London: Routledge; 1999a. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fought J. Leonard Bloomfield's linguistic legacy. Historiographia Linguistica. 1999b;26((3)):313–332. [Google Scholar]

- Fries C.C. Linguistics and reading. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard I. Leonard Bloomfield's descriptive and comparative studies of Algonquian. In: Hall R.A Jr, editor. Leonard Bloomfield: Essays on his life and work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1987. pp. 179–217. [Google Scholar]

- Hall R.A., Jr . In memoriam Leonard Bloomfield. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 547–553. [Google Scholar]

- Hall R.A., Jr . A life for language: A biographical memoir of Leonard Bloomfield. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hockett C.F. Introduction to The Language of Science [Fragments], by Leonard Bloomfield. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970a. pp. 333–334. [Google Scholar]

- Hockett C.F. Introduction to Language or Ideas? by Leonard Bloomfield. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970b. p. 322. [Google Scholar]

- Hockett C.F. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1984. Foreword. In L. Bloomfield, Language (pp. ix–xiv). pp. ix–xiv. [Google Scholar]

- Hockett C.F. Leonard Bloomfield: After fifty years. Historiographia Linguistica. 1999;26((3)):295–311. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph J.E, Love N, Taylor T.J. Landmarks in linguistic thought: Vol. 2. The western tradition in the twentieth century. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner E.F.K. Remarks on the origins of morphophonemics in American structuralist linguistics. Language & Communication. 2003;23:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kroesch S. Language, by L. Bloomfield [Review]. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 260–264. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann W.P. Bloomfield as an Indo-Europeanist. In: Hall R.A Jr, editor. Leonard Bloomfield: Essays on his life and work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1987. pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lepschy G.C. A survey of structural linguistics. London: Andre Deutsch; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes E. A identidade e a diferença: raízes históricas das teorias estruturais da narrativa [Identity and difference: Historical roots of structural theories of narrative] São Paulo, Brazil: São Paulo University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons J. Language and linguistics: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Matos M.A, Passos M.L.R.F. O ato da fala de L. Bloomfield: A ênfase sobre as conseqüências da fala [Leonard Bloomfield's act of speech: The emphasis on the consequences of speech]. In: Kerbauy R.R, Wielenska R.C, editors. Sobre Comportamento e Cognição: Vol. IV [On behavior and cognition: Vol. IV] Santo André, Brazil: ARBytes; 1999. pp. 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Matos M.A, Passos M.L.R.F. Emergent verbal behavior and analogy: Skinnerian and linguistics' approaches. May, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M.A, Passos M.L.R.F. Linguistic sources of Skinner's Verbal Behavior. The Behavior Analyst. 2006;29:89–107. doi: 10.1007/BF03392119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews P.H. Distributional syntax. In: Bynon T, Palmer F.R, editors. Studies in the history of western linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986. pp. 245–277. [Google Scholar]

- McIlvane W.J. Maria Amelia Matos: A remembrance and appreciation. In M. A. Matos, A. L. Matos, & W. J. McIlvane (2006). Rudimentary reading repertoires via stimulus equivalence and recombination of minimal verbal units. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2006;22:3–19. doi: 10.1007/BF03393023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish J, Martin J. Verbal behavior: A review and experimental analysis. The Journal of General Psychology. 1975;93:3–66. [Google Scholar]

- Murray S.O. How dark was the eclipse of Bloomfield? In: Fought J, editor. Leonard Bloomfield: Critical assessments of leading linguists: Vol 2. Reviews and meaning. London: Routledge; 1999. pp. 342–344. [Google Scholar]

- Passos M.L.R.F. Bloomfield e Skinner: língua e comportamento verbal [Bloomfield and Skinner: Language and verbal behavior] Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Nau; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Passos M.L.R.F. Bloomfield and Skinner: Speech-community, functions of language, and scientific activity. The Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;1((4)/2)((1)):76–96. [Google Scholar]

- Passos M.L.R.F, Matos M.A. The influence of Bloomfield's “Language” (1933) on B. F. Skinner's “Verbal Behavior” (1957) 1998. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Robins R.H. Appendix: History of linguistics. In: Newmeyer F.J, editor. Linguistics: The Cambridge survey, Vol. 1: Linguistic theory: Foundations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. pp. 462–484. [Google Scholar]

- Robins R.H. A short history of linguistics (4th ed.) London: Longman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D.E. The influence of Pānini on Leonard Bloomfield. In: Hall R.A Jr, editor. Leonard Bloomfield: Essays on his life and work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1987. pp. 89–138. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Science and human behavior. New York: Macmillan; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Verbal behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Contingencies of reinforcement: A theoretical analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. The shaping of a behaviorist. New York: Knopf; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Smith H.L., Jr Let's read: A linguistic approach, by L. Bloomfield & C. L. Barnhart [Review]. Language. 1963;39:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant E.H. Language, by L. Bloomfield. [Review]. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 265–266. [Google Scholar]

- Tomalin M. Leonard Bloomfield: Linguistics and mathematics. Historiographia Linguistica. 2004;31((1)):105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Tomanari G.Y. We lost a leader: Maria Amelia Matos (1939–2005). The Behavior Analyst. 2006;29:109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss A.P. A theoretical basis of human behavior (2nd ed.) Columbus, OH: R. G. Adams; 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J.U. Bloomfield as an Austronesianist. In: Hall R.A Jr, editor. Leonard Bloomfield: Essays on his life and work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1987. pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar]