Abstract

Background

A neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion (NVHL) induces behavioral and physiological anomalies mimicking pathophysiological changes of schizophrenia. Because prefrontal cortical (PFC) pyramidal neurons recorded from adult NVHL rats exhibit abnormal responses to activation of the mesocortical dopaminergic (DA) system, we explored whether these changes are due to an altered DA modulation of pyramidal neurons.

Methods

Whole-cell recordings were used to examine the effects of DA and glutamate agonists on cell excitability in brain slices obtained from pre- (postnatal day [PD] 28 –35) and post-pubertal (PD > 61) sham and NVHL animals.

Results

N-methyl d-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole propionate (AMPA), and the D1 agonist SKF38393 increased excitability of deep layer pyramidal neurons in a concentration-dependent manner. The opposite effect was observed with the D2 agonist quinpirole. The effects of NMDA (but not AMPA) and SKF38393 on cell excitability were significantly higher in slices from NVHL animals, whereas quinpirole decrease of cell excitability was reduced. These differences were not observed in slices from pre-pubertal rats, suggesting that PFC DA and glutamatergic systems become altered after puberty in NVHL rats.

Conclusions

A disruption of PFC dopamine– glutamate interactions might emerge after puberty in brains with an early postnatal deficit in hippocampal inputs, and this disruption could contribute to the manifestation of schizophrenia-like symptoms.

Keywords: Adolescence, dopamine receptors, electrophysiology, GABA transmission, neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion, NMDA, puberty

The neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion (NVHL) has been proposed as a developmental animal model of cortical pathophysiological changes in schizophrenia. The NVHL produces a variety of behavioral and neurochemical abnormalities resembling phenomena observed in schizophrenia (Lipska and Weinberger 1998, 2000). Hyperlocomotion, excessive reactivity to stress, and deficits in sensorimotor gating and social interactions are typically observed in NVHL animals (Becker et al. 1999; Le Pen et al. 2000; Lipska et al. 1993, 2002), and most of these alterations become evident only after puberty (Lipska and Weinberger 1998, 2000). Treatment with classical and atypical antipsychotic drugs has been shown to reverse many of the abnormal behavioral and physiological changes associated with the NVHL (Goto and O’Donnell 2002; Le Pen and Moreau 2002; Lipska and Weinberger 1994), strengthening the notion that neural alterations in this model are relevant to schizophrenia pathophysiology.

Dopaminergic (DA) mesolimbic/mesocortical systems are compromised in these animals. In vivo intracellular recordings of prefrontal cortical (PFC) pyramidal neurons have revealed an abnormal response to activation of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in NVHL rats (O’Donnell et al. 2002). Ventral tegmental area stimulation typically induces a prolonged plateau depolarization with suppression of action potential firing in the normal PFC (Lewis and O’Donnell 2000). In contrast, an abnormal increase in spike firing was observed in NVHL animals but only after puberty and not with analogous lesions performed during adulthood (O’Donnell et al. 2002). Similar abnormal responses to VTA stimulation were observed in the nucleus accumbens (Goto and O’Donnell 2002), and these responses were eliminated with a PFC lesion (Goto and O’Donnell 2004). Thus, a disruption of DA actions in the PFC might be a critical component in NVHL animals. Because PFC DA–glutamate interactions continue to mature after puberty (Tseng and O’Donnell 2005), it is possible that a delayed disruption of these interactions is responsible for the abnormal mesocortical response observed in the PFC of NVHL animals. Here we performed whole-cell patch clamp recordings of PFC pyramidal neurons in brain slices obtained from NVHL and control animals at pre- and post-pubertal ages. We examined the changes in cell excitability induced by DA and glutamate agonists in NVHL animals. Because we have recently reported a strong D2 attenuation of PFC α-amino-3-hydroxy-5- methylisoxazole propionate (AMPA) and N-methyl d-aspartate (NMDA) responses (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004) that shapes PFC cell firing and in vivo data show that PFC neurons show exaggerated firing in response to mesocortical activation (O’Donnell et al. 2002), we explored whether a D2 downregulation of NMDA responses was affected in NVHL animals.

Methods and Materials

All experimental procedures were performed at Albany Medical College according to the U.S. Public Health Service Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Albany Medical College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

NVHL

Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained at 18 days of gestation from Taconic Farms (Germantown, New York). At postnatal day (PD) 6, male pups (15–19 g) were randomly separated into two groups either to be lesioned with ibotenic acid or to receive a vehicle injection. Male pups (PD 6–7) were anesthetized with hypothermia by placing them in wet ice for 10–15 min and secured onto a platform on a stereotaxic frame. A cannula was lowered into the ventral hippocampus (anteroposterior [AP]: −3.0 mm; lateral [L]: +3.5 mm; dorso-ventral [DV]: −5.0 mm), and .3 μL o f ibotenic acid (10μg/μL in mmol: 148 sodium chloride [NaCl], 3 potassium chloride [KCl], .2 sodium phosphate monobasic [NaH2PO4], 1.5 sodium phosphate dibasic [Na2HPO4], 1.4 calcium chloride dihydrate [CaCl2], 8 magnesium perchlorate [MgCl2]; pH 7.4) was delivered with a minipump at a rate of .15 μL/min. The cannula was left in place for 3 additional minutes before being removed. This procedure was repeated in the contralateral hippocampus. Sham animals received the same volume of vehicle on each side. After surgery, animals were warmed up and returned to their cages, where they remained undisturbed until weaning except for husbandry. All rats were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with food and tap water available ad libitum until the time of the experiment. The entire rostrocaudal extent of damage (areas with cell loss and cell disorganization) was estimated in all animals by Nissl staining as previously reported. Lesion sizes were estimated roughly as the area at the coronal section in which they were largest, by measuring the diameter of damage extent (O’Donnell et al. 2002).

Whole-Cell Patch Clamp Recordings

Rats were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, IP) before being decapitated. Brains were rapidly removed into ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mmol): 125 NaCl, 25 sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), 10 glucose, 3.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, .5 CaCl 2, and 3 MgCl2 (pH 7.45, osmolarity 295 ± 5 mOsm). Coronal slices (300 μm) containing only the medial PFC and adjacent white matter were cut on a Vibratome in ice-cold ACSF, transferred and incubated in warm (approximately 35°C) ACSF solution constantly oxygenated with 95% oxygen (O2)/5% carbon dioxide (CO2) for at least 90 min before recording. In the recording ACSF, CaCl2 was increased to 2 mmol and MgCl2 was decreased to 1 mmol. Patch pipettes (5–8 MΩ) were filled with (in mmol): 115 K-gluconate, 10 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 2 MgCl2, 20 KCl, 2 Mg adenosine triphosphate (MgATP), 2 aden - osine triphosphate (bi-sodium salt), .3 5′-guanylate triphosphate (GTP), and .125% Neurobiotin (pH 7.3, 280 ± 5 mOsm).

All experiments were conducted at 33°–35°C in ACSF (perfusion speed: 2 mL/min) constantly oxygenated with 95% O2/5% CO2. The PFC pyramidal neurons were identified under visual guidance with infrared-differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) video microscopy with a 40× water-immersion objective (Olympus BX51WI; Olympus America, Melville, New York). The image was detected with an IR-sensitive CCD camera (DAGE-MTI, Michigan City, Indiana) and displayed on a monitor. Whole-cell current-clamp recordings were performed with a computer-controlled amplifier (MultiClamp 700A; Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, California), and acquired with Axoscope 8.1 (Axon Instrument) at a sampling rate of 10 KHz. The liquid junction potential was not corrected, and electrode potentials were adjusted to zero before acquiring the whole-cell configuration. Input resistance (calculated from the linear portion of the current-voltage [IV] curve in the hyperpolarized direction), membrane potential, the number of evoked spikes, and the latency to the first spike evoked by a 500-msec-duration depolarizing current pulse were analyzed before and after drug treatment. Changes in cell excitability induced by drugs (DA and glutamate agonists and antagonists) were assessed by repeated delivery of constant-intensity (adjusted during baseline recordings) depolarizing pulses (every 15 sec) while adding the agents to the bath. Typically, current intensities were adjusted to evoke 2 spikes during baseline for drugs with a known increase in cell excitability or 4–5 spikes for drugs with a known attenuation of cell excitability (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004). All drugs (SKF38393, quinpirole, eticlopride, SCH23390, NMDA, and AMPA) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri). They were dissolved into oxygenated ACSF and applied in the recording solution at known concentrations. Both control and drug-containing ACSF were continuously oxygenated throughout the experiments. After 10–15 min of baseline recordings, a solution containing the drug cocktail was perfused for 5–6 min. All comparisons with baseline conditions were conducted 4–6 min after the onset of drug application. The effects observed with NMDA or AMPA were evident after the initial 3 min of drug application and required around 5–10 min to wash out. The effects obtained with D1 and D2 agonists were evident after 3 min of drug application and required 15–20 min to partially wash out (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004). All values are expressed as mean ± SD. Student t test was used for two-group comparisons involving a single continuous variable, and drug effects were compared with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). A two-way ANOVA was preferred to analyze the interactions between drug effects and lesion. The differences between experimental conditions were considered statistically significant when p < .05.

Results

Whole-cell current clamp recordings of PFC pyramidal neurons were conducted in brain slices obtained from 38 NVHL and 30 sham-operated post-pubertal (PD 61– 85) rats (Figure 1) from 14 litters. Rats from 11 litters were used in both groups, and the remaining 3 litters provided solely NVHL rats. Only one neuron per slice was recorded and typically two to three cells were obtained per animal. All recordings were performed with visual guidance, and Neurobiotin staining revealed that all recorded neurons were pyramidal cells (Figure 2B) located in deep layers of the medial PFC (prelimbic and infralimbic regions). These neurons were silent at rest, showing action potential firing in response to depolarizing current pulses (Figure 2A) and inward rectification with hyperpolarizing current injection (Figure 2C). The PFC pyramidal neurons recorded from NVHL (n = 82 cells) and sham (n = 71) animals exhibited similar resting membrane potential (NVHL: −70.5 ± 2.5 mV; sham: −70.6 ± 2.7 mV, mean ± SD) and input resistance (NVHL: 140.2 ± 42.5 MΩ; sham: 134.8 ± 34.1 MΩ). No significant differences in action potential threshold or spike kinetics (duration and amplitude) were observed between sham and lesioned groups (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion (NVHL). (A) Coronal sections showing the ventral hippocampus of a sham rat (top) and a typical NVHL (bottom), characterized by cell loss (thick arrows), and enlarged ventricles (thin arrows). (B) Drawings illustrating the extension of the neonatal lesion observed in adulthood. Gray and dark areas indicate maximal and minimal extents of damage, respectively.

Figure 2.

Whole-cell patch clamp recording of medial prefrontal cortical (PFC) pyramidal neurons from adult animals. (A) Typical responses to depolarizing and hyperpolarizing somatic current pulses (300 msec, from −300 to +100 pA) of a deep layer pyramidal neuron recorded from an adult rat. (B) Image of a typical deep-layer pyramidal neuron recorded from the medial PFC and labeled with Neurobiotin. Black arrowheads indicate the apical dendrite and the white arrowhead points to the cell body. (C) Current-voltage plot obtained from the traces shown in (A). Currents larger than −100 pA yielded an evident inward rectification (arrowhead) in the hyperpolarizing direction.

Reduced D2 Suppression and Increased D1 Enhancement of PFC Pyramidal Neuron Excitability in Adult NVHL Animals

The DA modulation of pyramidal cell excitability was assessed by measuring the number of spikes and the latency to the first spike evoked by constant-amplitude depolarizing current pulses (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004) in slices from NVHL and sham animals. To obtain an accurate measurement of cell excitability independent of membrane potential changes, continuous direct current was applied through the recording electrode to hold the cell to baseline membrane potential when drugs elicited changes in membrane potential.

Bath application of the D2 agonist quinpirole induced a concentration-dependent decrease of pyramidal cell excitability in both NVHL and sham animals without apparent changes in the membrane potential, action potential threshold, or kinetics. A two-way ANOVA revealed overall significant effects of “lesion group” and “drug concentration” in both the number of evoked spikes [lesion: F(1,69) = 59.45, p < .0001; drug: F(5,69) = 43.49, p < .0001] and the latency to the first spike [lesion: F(1,69) = 9.58, p < .003; drug: F(5,69) = 27.34, p < .0001]. However, the inhibitory action of quinpirole was attenuated in animals with an NVHL, with its dose-response curve shifted to the right (Figure 3). In sham animals, quinpirole (1 μmol/L) decreased the number of evoked spikes from 4.1 ± .2 to 2.1 ± .5 spikes [p < .001 compared with NVHL, Tukey post hoc test after significant interaction between drug and lesion, two-way ANOVA: F(5,69) = 9.1, p < .0001] and increased the latency to the first spike from 44.2 ± 2.4 msec to 78.0 ± 11.6 msec [p < .001 compared with NVHL, Tukey post hoc test after significant interaction between drug and lesion, two-way ANOVA: F(5,69) = 4.7, p < .001]. This concentration of quinpirole failed to modify pyramidal neuron excitability in rats with an NVHL; only higher doses (2 and 4 μmol/L) yielded the inhibitory effect in NVHL animals comparable to that obtained with 1 μmol/L in the sham group (Figure 3). This decrease in neuronal excitability was accompanied by a significant increase in input resistance in all groups (sham: from 132.9 ± 19.8 to 162.7 ± 16.2 MΩ with 1 μmol/L quinpirole, p < .002, Student t test; NVHL: from 130.2 ± 22.1 to 151.7 ± 29.1 MΩ with 2 μmol/L quinpirole, p < .02, Student t test) and was completely blocked with the D2 antagonist eticlopride. In presence of 20 μmol/L eticlopride, quinpirole (2 μmol/L) failed to change the number of evoked spikes (from 4 ±.3 to 3.9 ±.3 spikes, n = 5) or the latency to the first spike (from 48.6 ± 7.4 to 46.9 ± 9.7 msec) in cells recorded from NVHL rats. Eticlopride also blocked the inhibitory effect of quinpirole 4 μmol/L in the PFC of both sham and NVHL animals (n = 3/group, data not shown). Thus, the normal D2 attenuation of pyramidal cell excitability is reduced in animals that developed without a proper hippocampal innervation of the PFC, an effect that could be related to the reduced effect of the agonist on input resistance observed in the lesioned animals.

Figure 3.

The inhibitory effect of quinpirole on prefrontal cortical (PFC) pyramidal cell excitability is reduced in neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion (NVHL) animals. (A) Line graphs summarizing the concentration-dependent effect of quinpirole (n = 5– 6 cells/dose) on the excitability of PFC pyramidal neurons recorded from adult (postnatal day [PD] 61–78) NVHL and sham-operated animals (all data are mean ± SD; ***p < .0005, **p < .005, *p < .01, Tukey post hoc test after significant two-way analysis of variance). Only higher doses (2 and 4 μmol/L) yielded the inhibitory effect in NVHL animals (#p < .0002 compared with baseline, Tukey post hoc test). (B) Representative traces illustrating the effect of 1 μmol/L quinpirole on PFC pyramidal neuron excitability. Quinpirole (1 μmol/L) reduced the number of evoked spikes from 4 to 2 spikes in the PFC of sham animals, whereas no apparent effect was observed in the lesioned group.

Bath application of the D1 agonist SKF38393 resulted in a concentration-dependent excitability increase in pyramidal neurons from both groups of neurons. The two-way ANOVA revealed, similar to what was observed with quinpirole, overall significant effects of “lesion group” and “drug concentration” with SKF38393 in both the number of spikes [lesion: F(1,54) = 20.73, p < .0001; drug: F(4,54) = 54.29, p < .0001] and the latency to the first spike [lesion: F(1,54) = 23.93, p < .0001; drug: F(4,54) = 65.36, p < .0001] evoked by current pulses. However, the effect of SKF38393 was enhanced in NVHL animals (Figure 4). Bath application of 1 and 2 μmol/L SKF38393 failed to affect pyramidal cell excitability in sham animals but increased the number of evoked action potentials from 1.9 ± .3 to 2.6 ± .3 and 3.2 ± .4 [p < .001, Tukey post hoc test after significant interaction between drug and lesion, two-way ANOVA: F(4,54) = 3.1, p = 0.024], respectively, and reduced the latency to the first evoked spike from 105.8 ± 9.9 msec to 72.9 ± 12.6 and 55.7 ± 15.8 msec [p < .001, Tukey post hoc test after significant interaction between drug and lesion, two-way ANOVA: F(4,54) = 3.8, p = 0.009], respectively, in neurons recorded from NVHL animals (Figure 4). This excitatory effect of SKF38393 was independent of membrane potential depolarization and was not accompanied by changes in input resistance or action potential threshold or duration (data not shown). Furthermore, the D1 antagonist SCH23390 (10 μmol/L, n = 5 cells recorded from NVHL animals) blocked the effect of 8 μmol/L SKF38393. The number of evoked spikes and the latency to the first spike remained unchanged when the agonist was administered in presence of the antagonist. Evoked action potentials were 1.9 ± .4 before drug application and 2.1 ± .6 after SKF38393 + SCH23390. Similarly, the first spike latency was 107.5 ± 12.4 msec before SKF38393 + SCH23390 and 103.3 ± 14.5 msec after drug administration. Altogether, these results suggest that both D1 and D2 modulation of PFC neuronal activity are disrupted in animals with an NVHL, in a manner that would cause hyperexcitability in response to mesocortical activation.

Figure 4.

The excitatory effect of SKF38393 on prefrontal cortical (PFC) pyramidal cell excitability is enhanced in neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion (NVHL) animals. (A) Line graphs summarizing the concentration-dependent effect of SKF38393 (n = 5– 6 cells/dose) on the excitability of PFC pyramidal neurons recorded from adult (postnatal day [PD] 61–78) sham-operated and NVHL animals (***p < .0005, **p < .005, Tukey post-hoc test after significant two-way analysis of variance). (B) Traces of responses of two representative pyramidal neurons recorded from a sham and an NVHL rat during baseline and after bath application of 2 μmol/L SKF38393. The number of evoked spikes was not affected by SKF38393 in the neuron recorded from the sham rat. In contrast, bath application of 2 μmol/L SKF38393 increased pyramidal cell excitability from 2 to 3 spikes in the lesioned rat.

Increased Excitatory Effect of NMDA But Not AMPA in the PFC of Adult NVHL Animals

Bath application of NMDA and AMPA depolarize pyramidal neurons, particularly at higher doses (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004). Therefore, pyramidal neuron excitability was measured in all cases, holding the cells to baseline membrane potential with a continuous DC injection when necessary.

Bath application of NMDA induced a dose-dependent increase in excitability in PFC pyramidal neurons recorded from both lesioned and sham animals. However, the response to NMDA was higher in NVHL animals when compared with the sham-operated group (Figure 5). A two-way ANOVA showed overall significant effects of “lesion group” and “drug concentration” with NMDA in both the number of evoked spikes [lesion: F(1,60) = 47.12, p < .0001; drug: F(4,60) = 218.5, p < .0001] and the latency to the first spike [lesion: F(1,60) = 31.96, p < .0001; drug: F(4,60) = 139.5, p < .0001]. Bath application of 1 μmol/L NMDA, a dose that failed to affect excitability in sham animals, significantly increased the number of evoked spikes [from 1.9 ± .2 to 3.6 ± .7 spikes, p < .001, Tukey post hoc test after significant interaction between drug and lesion, two-way ANOVA: F(4,60) = 7.1, p < .0002] and decreased the latency to the first evoked spike [from 101.1 ± 18.8 to 41.4 ± 9.5 msec, p < .001, Tukey post hoc test after significant interaction between drug and lesion, two-way ANOVA: F(4,60) = 10.7, p < .00001] of PFC pyramidal neurons in lesioned animals (Figure 5). Moreover, the excitatory responses to 2 and 4 μmol/L NMDA were also enhanced in NVHL animals when compared with the sham group (Figure 5). In contrast, the increase in pyramidal cell excitability induced by bath application of AMPA was not different between NVHL and sham animals (Figure 6). These results suggest that alterations in ventral hippocampal inputs during early postnatal development enhance NMDA-mediated excitation without affecting the responses to AMPA in the adult PFC.

Figure 5.

The excitatory effect of N-methyl d-aspartate (NMDA) on PFC pyramidal cell excitability is enhanced in NVHL animals. (A) Line graphs summarizing the concentration-dependent effect of NMDA (n = 5–7 cells/dose) on the excitability of pyramidal neurons recorded in the PFC of adult (PD 61–78) sham-operated and NVHL animals (***p < .0002, **p < .001, Tukey post hoc test after significant two-way analysis of variance). (B) Representative traces of two PFC pyramidal neurons recorded from a sham and a lesioned animal illustrating their response to 2 μmol/L NMDA. After 5 min of NMDA, the number of evoked spikes increased from 2 t o 3 spikes in the sham group, whereas a more pronounced increase (from 2 t o 7 spikes) was observed in the lesioned animal. Abbreviations as in Figure 4.

Figure 6.

The effect of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole propionate (AMPA) on PFC pyramidal cell excitability is unchanged in NVHL animals. The PFC pyramidal neuron excitability increases in a concentration-dependent manner after bath application of AMPA (top: number of evoked spikes; bottom: first spike latency, n = 5– 6 cells/dose). The PFC pyramidal neurons recorded from sham and NVHL animals (PD 61–78) exhibited similar increase in the number of evoked spikes and decrease of first spike latency. Abbreviations as in Figure 4.

Altered Responses to D2, D1, and NMDA Are Not Observed in NVHL Animals Before Puberty

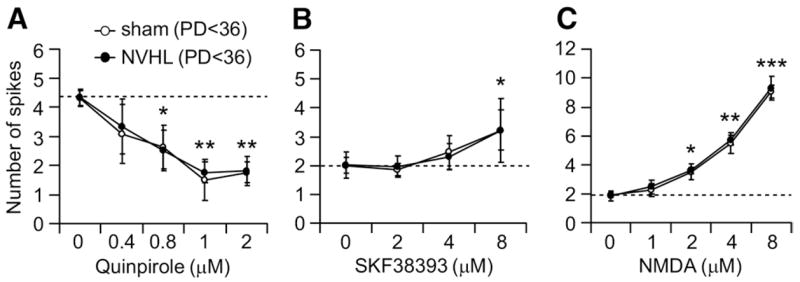

Because it has been repeatedly observed that NVHL-induced behavioral (Lipska and Weinberger 1998, 2000) and electrophysiological (O’Donnell et al. 2002) changes are evident only after puberty, additional recordings were performed to examine these responses in the PFC of pre-pubertal (PD 28–36) animals. Pyramidal neurons recorded from pre-pubertal sham (n = 23) and NVHL (n = 22) animals were silent at rest and exhibited similar resting membrane potential (NVHL: −68.5 ± 2.6 mV; sham: −68.4 ± 2.8 mV) and input resistance (NVHL: 140.6 ± 55.3 MΩ; sham: 134.1 ± 41.2 MΩ). Bath application of quinpirole resulted in similar concentration-dependent decrease of pyramidal cell excitability in both NVHL and sham animals, as revealed by the number evoked of spikes (Figure 7A) and latency to the first evoked spike (data not shown). Similarly, excitatory responses to increasing doses of SKF38393 and NMDA recorded in PFC pyramidal neurons from pre-pubertal lesioned and sham animals were undistinguishable (Figures 7B and 7C). These results indicate that the altered DA and glutamatergic control of pyramidal cell excitability observed in the adult NVHL animals are not present before puberty.

Figure 7.

Concentration-dependent effect of quinpirole (A), SKF38393 (B), and NMDA (C) on PFC pyramidal cell excitability (number of spikes evoked by somatic current pulses) recorded from pre-pubertal (PD 28 –36) animals. No differences were observed between sham-operated animals and those with an NVHL (4 –5 cells/dose). Abbreviations as in Figure 5. (*P <.05, **P <.01, ***P <.001.)

Disruption of D2–Glutamate Interactions in the Adult PFC of NVHL Animals

We have recently shown that activation of D2 receptors attenuates NMDA and AMPA-mediated excitation through different mechanisms in the PFC of developmentally mature animals (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004). To investigate whether these interactions are affected by an NVHL, we examined the effects of quinpirole on NMDA- and AMPA-induced excitability increase in PFC pyramidal neurons recorded from post-pubertal lesioned and sham animals. As reported previously (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004), bath application of .4 μmol/L (n = 4, data not shown) or 1 μmol/L quinpirole (n = 5) significantly reduced the excitatory effect of 4 μmol/L NMDA in sham animals (Figure 8). However, this D2 attenuation of NMDA effects was not observed in the lesioned group. Quinpirole (1 μmol/L, n = 6) failed to attenuate the changes in the number of evoked spikes or the latency to the first evoked spike observed with 4 μmol/L NMDA in the PFC of NVHL rats (Figure 8). The D2 modulation of AMPA-induced increase in excitability was also disrupted in the PFC of NHVL rats. Similar to what was observed with the D2–NMDA interaction, an attenuation of AMPA responses by quinpirole was only observed in pyramidal neurons recorded from sham animals (n = 5; Figure 9). In the PFC of NVHL rats, bath application of 1 μmol/L quinpirole failed to attenuate the increased number of evoked spikes or to reduce the latency to the first evoked spike induced with .2 μmol/L AMPA (Figure 9). These results indicate that an early postnatal disruption of the hippocampal inputs also alters the normal DA modulation of glutamatergic function in the adult PFC.

Figure 8.

Disruption of D2–NMDA interactions in the PFC of NVHL animals. Bar graphs summarize the effect of quinpirole on NMDA responses observed in the PFC of (A) sham and (B) NVHL animals (PD > 61). Bath application of quinpirole (1 μmol/L) significantly decreased the excitatory effect of NMDA (4 μmol/L) on PFC pyramidal neuron excitability (**p < .001, Tukey post hoc test after significant two-way analysis of variance). In contrast, the increase in the number of evoked spikes and decrease in first spike latency induced by NMDA were not affected by quinpirole in NVHL animals. Abbreviations as in Figure 5.

Figure 9.

Disruption of D2-AMPA interactions in the PFC of NVHL animals. Bar graphs summarize the effect of quinpirole on AMPA responses recorded in the PFC of (A) sham and (B) NVHL animals (PD > 61). The excitatory effects of .2 μmol/L AMPA on the number of evoked spikes and first spike latency were significantly attenuated with 1 μmol/L quinpirole in the PFC of sham animals (**p < .001, Tukey post hoc test after significant two-way analysis of variance). In contrast, these inhibitory actions of quinpirole on AMPA responses were not observed in PFC pyramidal neurons from NVHL rats. Abbreviations as in Figure 6.

Discussion

We investigated the effects of DA and glutamate on PFC pyramidal neuron excitability in brain slices obtained from NVHL and sham animals. As recently reported (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004), bath application of NMDA, AMPA, or the D1 agonist SKF38393 induced a concentration-dependent increase in pyramidal neuron excitability, whereas the D2 agonist quinpirole resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in cell excitability. The excitatory effects of SKF38393 and NMDA but not those mediated by AMPA were significantly enhanced in animals with an NVHL. The D2-mediated response was also altered in the PFC of lesioned animals, as revealed by a reduced attenuation of cell excitability by quinpirole. These changes were not evident in pre-pubertal animals, suggesting that PFC DA and glutamatergic systems become altered in neonatally lesioned animals only after puberty. In addition, the typical D2 attenuation of NMDA- and AMPA-mediated responses (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004) was only observed in the PFC of sham animals. These data indicate that PFC DA–glutamate interactions are also compromised in NVHL animals. Thus, all these changes might underlie the hyper-excitable PFC response to VTA stimulation (O’Donnell et al. 2002) and could be responsible for some of the behavioral deficits observed in these animals, which also emerge after puberty (Lipska and Weinberger 1998, 2000).

The PFC pyramidal neurons recorded from NVHL animals are more responsive to bath application of NMDA and the D1 agonist SKF38393 but not to AMPA. This selective excitability increase induced by NMDA or D1 activation was observed only in the PFC of post-pubertal (not pre-pubertal) NVHL animals, suggesting that an early disruption of the hippocampal–PFC pathway might alter the normal postnatal development of PFC D1 and NMDA function. Several mechanisms could account for these changes. It is well known that D1 receptors increase cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels and protein kinase A (PKA) activity (Nicola et al. 2000; Surmeier et al. 1995) and can potentiate NMDA-mediated excitation through a postsynaptic PFC– calcium-dependent mechanism (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004; Wang and O’Donnell 2001). It remains to be determined whether an abnormal upregulation of these postsynaptic second messenger cascade events could result in exaggerated pyramidal cell excitability in response to D1 and NMDA, as observed in the PFC of NVHL animals. A D1 receptor activation also induces NMDA receptor trafficking to the postsynaptic membrane (Dunah and Standaert 2001), increasing surface expression of NMDA receptors. This interaction could selectively enhance pyramidal neurons’ response to NMDA and not to AMPA in the adult PFC. In contrast, the reduced D2 inhibition and the lack of D2-mediated attenuation of AMPA and NMDA responses in the PFC of NVHL animals could reflect a disruption of D2 receptor function. We have shown that the attenuation of PFC pyramidal neuron excitability by D2 receptors depends on several mechanisms, including a direct postsynaptic modulation of cAMP-PKA and phospholipase C (PLC)–inositol 1,4–5 trisphosphate (IP3)-Ca++ second messenger cascades, and indirectly by enhancing firing of local γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic interneurons (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004). More precisely, the D2 attenuation of AMPA-mediated excitation involves postsynaptic inhibition of PKA and activation of PLC-IP3-Ca++ pathways, whereas the D2 inhibition of NMDA effects is mediated by activation of local GABAergic transmission (Tseng and O’Donnell 2004). Interestingly, the D2 activation of PFC GABAergic interneurons emerges after puberty (Tseng and O’Donnell 2006); thus, it is possible that PFC interneurons in NVHL animals acquire an abnormal response to DA during their peri-adolescent maturation. A deficit in PFC interneurons has indeed been suggested by the selective downregulation of glutamate decarboxylase-67 messenger RNA in the PFC of NVHL animals (Lipska et al. 2003a, 2003b). This, compounded by the abnormal potentiation of D1 and NMDA responses and the attenuation of D2 inhibition of AMPA responses, would yield a hyper-reactive PFC in NVHL animals, especially in response to mesocortical stimulation (O’Donnell et al. 2002; Tseng et al. 2006a). Thus, PFC DA–GABA– glutamate interactions are compromised in animals that received an early inactivation of the hippocampal formation.

To extrapolate the information obtained in brain slices to an intact brain and, even more, to a disease condition might require considering the limitations inherent in this preparation. The slices used here contained only the medial PFC, and all long-distance afferent projections had been sectioned by the coronal plane of slicing. However, a 300-μm-thick brain slice does contain a functional local network that allows the exploration of local interactions and actions of specific transmitters within that network. Thus, although these experiments were conducted in a reduced preparation, the cellular changes observed are likely to underscore the manner the entire system responds to mesocortical activation.

Post-pubertal alterations in the PFC of animals with a bilateral NVHL have been proposed to model the cortical deficits observed in schizophrenia (Lipska and Weinberger 1998), a disorder characterized by hypofrontality. Our findings of overall enhancement of PFC pyramidal neuron excitability in NVHL animals are consistent with increased firing observed in vivo with VTA stimulation in this model (O’Donnell et al. 2002). However, these observations might seem at odds with the common concept of hypofrontality. Hypofrontality typically refers to the lack of PFC activation during working-memory tasks (for review, see Manoach 2003). But it remains unknown whether “hypofrontality” is the result of a hypoactive PFC or a PFC with a hyperactive baseline that has limited room for further increase in activity when needed. For example, some studies have shown absence of changes or even increased activation of the frontal cortices of schizophrenia patients (Callicott et al. 1999, 2000, 2003a, 2003b; Honey et al. 2002; Manoach et al. 1999, 2000). The PFC dysfunction and working memory deficits in schizophrenia are variable and complex, probably depending on the loads required to conduct the working memory task. In imaging studies, PFC responses typically increase until the task load exceeds the PFC functional capacity, during which the activation decreases (for review, see Manoach 2003). A similar non-linear relationship was observed in schizophrenia but with increases at low working memory loads and a decrease in metabolic activity with loads that would engage the PFC of control subjects (Manoach 2003). The PFC metabolic responses to different intensities of VTA stimulation were tested in both sham and NVHL animals with cytochrome oxidase I staining, revealing a leftward shift only in post-pubertal animals that had received a bilateral NVHL (Tseng et al. 2006a). A functional magnetic resonance imaging study has also revealed increased blood flow in several brain regions, including the PFC, in NVHL animals (Risterucci et al. 2005). Therefore, the heightened excitability of pyramidal neurons reported here might represent a hyperactive state at low loads, potentially leading to a hypo-frontal state with higher demands.

What could be responsible for such dramatic changes at a late developmental stage? Without doubt, this question is essential to understanding how symptoms in schizophrenia, a disorder with a clear genetic predisposition (Harrison and Weinberger 2005), emerge late in adolescence. Several studies have highlighted a protracted PFC maturation. In human subjects, imaging studies revealed late changes in PFC morphology (Pantelis et al. 2005). Local PFC circuits do mature during adolescence in rats (Tseng and O’Donnell 2005, 2006) and monkeys (Woo et al. 1997). Thus, it is possible that the DA modulation of PFC circuits, including pyramidal cells and interneurons, matures during adolescence. It can be speculated that, in a brain in which hippocampal inputs to the PFC were disrupted during early development, PFC circuits become improperly assembled but do not result in behavioral anomalies until adolescence, because that is the time in which they would acquire an adult profile, particularly in their DA modulation. This possibility and the potential cellular mechanisms involved remain to be explored.

The mesocortical system is activated by salient stimuli (Horvitz 2000) and contributes to cognitive functions, including working memory, attention, and reward (Goldman-Rakic et al. 2000; Jay 2003; Schultz 2002). Ventral tegmental area stimulation with trains of pulses mimicking DA cell burst firing, typically observed with salient or reward-predicting stimuli, yields plateau depolarization along with reduced action potential firing (Lewis and O’Donnell 2000). This has been interpreted as a mechanism by which the mesocortical system reduces the impact of weak inputs, enhancing the saliency of stronger activated afferents to the PFC (O’Donnell 2003). This context-dependent DA increase will activate both D1 and D2 receptors, with D1 activation facilitating ongoing NMDA activity (Tseng and O’Donnell 2005; Wang and O’Donnell 2001) and both D1 and D2 activation reducing irrelevant excitatory inputs by increasing local inhibitory tone (Goldman-Rakic et al. 2000; Gorelova et al. 2002; Tseng and O’Donnell 2004, 2006; Tseng et al. 2006b) and reducing pyramidal neuron excitability in response to mesocortical stimulation (Lewis and O’Donnell 2000; Tseng et al. 2006b). The abnormal excitation by D1 and NMDA along with the lack of D2-mediated inhibition of AMPA and NMDA effects in the PFC of NVHL animals might contribute to establish the altered PFC electrophysiological (O’Donnell et al. 2002) and metabolic (Tseng et al. 2006a) responses observed in these animals. A disruption of DA-mediated inhibition might result in abnormal and inappropriate engagement of pyramidal neuron firing in response to excitatory inputs, which ultimately might lead to altered cognitive performance in NVHL animals (Chambers et al. 1999), a model proposed to mimic some of the cortical deficits observed in schizophrenia (Lipska and Weinberger 1998). Our observation, that this pattern of altered DA–glutamate–GABA interactions within PFC is a late emerging physiology, also might have implications for our understanding of the clinical onset in early adult life of the schizophrenia phenotype.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by MH57683 Grant (PO) and a National Alliance Research Schizophrenia and Depression Independent Investigator Award (PO).

We would like to thank Dr. Daniel R. Weinberger for the inspiration for this work and comments on the manuscript.

References

- Becker A, Grecksch G, Bernstein HG, Hollt V, Bogerts B. Social behaviour in rats lesioned with ibotenic acid in the hippocampus: quantitative and qualitative analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;144:333–338. doi: 10.1007/s002130051015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callicott JH, Bertolino A, Mattay VS, Langheim FJ, Duyn J, Coppola R, et al. Physiological dysfunction of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia revisited. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:1078 –1092. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.11.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callicott JH, Egan MF, Mattay VS, Bertolino A, Bone AD, Verchinksi B, et al. Abnormal fMRI response of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in cognitively intact siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003a;160:709 –719. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callicott JH, Mattay VS, Bertolino A, Finn K, Jones K, Frank JA, et al. Physiological characteristics of capacity constraints in working memory as revealed by functional MRI. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:20 –26. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callicott JH, Mattay VS, Verchinski BA, Marenco S, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Complexity of prefrontal cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia: More than up or down. Am J Psychiatry. 2003b;160:2209 –2215. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers RA, Moore J, McEvoy JP, Levin ED. Cognitive effects of neonatal hippocampal lesions in a rat model of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15:587–594. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunah AW, Standaert DG. Dopamine D1 receptor-dependent trafficking of striatal NMDA glutamate receptors to the postsynaptic membrane. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5546 –5558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05546.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS, Muly EC, 3rd, Williams GV. D1 receptors in prefrontal cells and circuits. Brain Res Rev. 2000;31:295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelova N, Seamans JK, Yang CR. Mechanisms of dopamine activation of fast-spiking interneurons that exert inhibition in rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:3150 –3166. doi: 10.1152/jn.00335.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y, O’Donnell P. Delayed mesolimbic system alteration in a developmental animal model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9070–9077. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-09070.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y, O’Donnell P. Prefrontal lesion reverses abnormal mesoaccumbens response in an animal model of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:172–176. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00783-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: On the matter of their convergence. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:40 – 68. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey GD, Bullmore ET, Sharma T. De-coupling of cognitive performance and cerebral functional response during working memory in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;53:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz JC. Mesolimbocortical and nigrostriatal dopamine responses to salient non-reward events. Neuroscience. 2000;96:651– 656. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay TM. Dopamine: A potential substrate for synaptic plasticity and memory mechanisms. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;69:375–390. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pen G, Grottick AJ, Higgins GA, Martin JR, Jenck F, Moreau JL. Spatial and associative learning deficits induced by neonatal excitotoxic hippocampal damage in rats: Further evaluation of an animal model of schizophrenia. Behav Pharmacol. 2000;11:257–268. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200006000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pen G, Moreau JL. Disruption of prepulse inhibition of startle reflex in a neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: Reversal by clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone but not by haloperidol. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BL, O’Donnell P. Ventral tegmental area afferents to the prefrontal cortex maintain membrane potential ‘up’ states in pyramidal neurons via D(1) dopamine receptors. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:1168 –1175. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.12.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipska BK, Aultman JM, Verma A, Weinberger DR, Moghaddam B. Neonatal damage of the ventral hippocampus impairs working memory in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:47–54. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipska BK, Jaskiw GE, Weinberger DR. Postpubertal emergence of hyperresponsiveness to stress and to amphetamine after neonatal excitotoxic hippocampal damage: A potential animal model of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:67–75. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipska BK, Lerman DN, Khaing ZZ, Weickert CS, Weinberger DR. Gene expression in dopamine and GABA systems in an animal model of schizophrenia: Effects of antipsychotic drugs. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:391– 402. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipska BK, Lerman DN, Khaing ZZ, Weinberger DR. The neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion model of schizophrenia: Effects on dopamine and GABA mRNA markers in the rat midbrain. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:3097–3104. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipska BK, Weinberger DR. Subchronic treatment with haloperidol and clozapine in rats with neonatal excitotoxic hippocampal damage. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1994;10:199 –205. doi: 10.1038/npp.1994.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipska BK, Weinberger DR. Prefrontal cortical and hippocampal modulation of dopamine-mediated effects. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;42:806 – 809. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60869-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipska BK, Weinberger DR. To model a psychiatric disorder in animals: Schizophrenia as a reality test. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:223–239. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoach DS. Prefrontal cortex dysfunction during working memory performance in schizophrenia: reconciling discrepant findings. Schizophr Res. 2003;60:285–298. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoach DS, Gollub RL, Benson ES, Searl MM, Goff DC, Halpern E, et al. Schizophrenic subjects show aberrant fMRI activation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia during working memory performance. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:99 –109. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoach DS, Press DZ, Thangaraj V, Searl MM, Goff DC, Halpern E, et al. Schizophrenic subjects activate dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during a working memory task as measured by fMRI. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1128 –1137. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola SM, Surmeier J, Malenka RC. Dopaminergic modulation of neuronal excitability in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:185–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell P. Dopamine gating of forebrain neural ensembles. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:429 – 435. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell P, Lewis BL, Weinberger DR, Lipska BK. Neonatal hippocampal damage alters electrophysiological properties of prefrontal cortical neurons in adult rats. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:975–982. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Yucel M, Wood SJ, Velakoulis D, Sun D, Berger G, et al. Structural brain imaging evidence for multiple pathological processes at different states of brain development in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 2005;31:672– 696. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risterucci C, Jeanneau K, Schoppenthau S, Bielser T, Kunnecke B, von Kienlin M, Moreau JL. Functional magnetic resonance imaging reveals similar brain activity changes in two different animal models of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 2005;180:724 –734. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Getting formal with dopamine and reward. Neuron. 2002;36:241–263. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, Bargas J, Hemmings HC, Jr, Nairn AC, Greengard P. Modulation of calcium currents by a D1 dopaminergic protein kinase/phosphatase cascade in rat neostriatal neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:385–397. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng KY, O’Donnell P. Dopamine-glutamate interactions controlling prefrontal cortical pyramidal cell excitability involve multiple signaling mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5131–5139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1021-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng KY, O’Donnell P. Post-pubertal emergence of prefrontal cortical up states induced by D1-NMDA co-activation. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:49 –57. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng KY, Amin F, Lewis BL, O’Donnell P. Altered prefrontal cortical metabolic response to mesocortical activation in adult animals with a neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion. Biol Psychiatry. 2006a;60:585–590. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng KY, Mallet N, Toreson KL, Le Moine C, Gonon F, O’Donnell P. Excitatory response of prefrontal cortical fast-spiking interneurons to ventral tegmental area stimulation in vivo. Synapse. 2006b;59:412– 417. doi: 10.1002/syn.20255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng KY, O’Donnell P. Dopamine modulation of prefrontal cortical interneurons changes during adolescence. Cereb Cortex. 2006 Jul 3; doi: 10.1093/cercor/bh1034. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, O’Donnell P. D1 dopamine receptors potentiate NMDA-mediated excitability increase in layer V prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:452– 462. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.5.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo TU, Pucak ML, Kye CH, Matus CV, Lewis DA. Peripubertal refinement of the intrinsic and associational circuitry in monkey prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1997;80:1149 –1158. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]