Abstract

Activin receptor type IIB (ActRIIB), a type II TGF-β serine/threonine kinase receptor, is integral to the activin and myostatin signaling pathway. Ligands such as activin and myostatin bind to activin type II receptors (ActRIIA, ActRIIB), and the GS domains of type I receptors are phosphorylated by type II receptors. Myostatin, a negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth, is regarded as a potential therapeutic target and binds to ActRIIB effectively, and to a lesser extent, to ActRIIA. The high-resolution structure of human ActRIIB kinase domain in complex with adenine establishes the conserved bilobal architecture consistent with all other catalytic kinase domains. The crystal structure reveals that the adenine has a considerably different orientation from that of the adenine moiety of ATP observed in other kinase structures due to the lack of an interaction by ribose-phosphate moiety and the presence of tautomers with two different protonation states at the N9 nitrogen. Although the Lys217–Glu230 salt bridge is absent, the unphosphorylated activation loop of ActRIIB adopts a conformation similar to that of the fully active form. Unlike the type I TGF-β receptor, where a partially conserved Ser280 is a gatekeeper residue, the AcRIIB structure possesses Thr265 with a back pocket supported by Phe247. Taken together, these structural features provide a molecular basis for understanding the coupled activity and recognition specificity for human ActRIIB kinase domain and for the rational design of selective inhibitors.

Keywords: TGF-β, ActRIIB, serine threonine kinase receptor

Activin receptor type IIB(ActRIIB) is a member of a family of signaling receptors that bind and are activated by transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) cytokines. TGF-β signaling pathways are central to processes that control growth, differentiation, and the fate of cells (Massagué et al. 2000; Tsuchida 2004).

Similar to other TGF-β receptors, ActRIIB is a type II receptor characterized by a short extracellular ligand-binding domain and a larger intracellular serine/threonine kinase domain (Mathews and Vale 1991; Donaldson et al. 1992; Shinozaki et al. 1992). Signaling through TGF-β receptors involves the binding of an extracellular ligand to a type II receptor. The ligand/type II receptor complex phosphorylates a type I receptor via serine/threonine kinase domains of the respective receptors. The signal is further propagated into the cell, initially by phosphorylation of Smad proteins (Attisano et al. 1996; Shi and Massagué 2003; Graham and Peng 2006).

Myostatin, also referred to as growth and differentiation factor 8 (GDF-8), is an endogenous extracellular ligand of ActRIIB in skeletal muscle. Signaling by myostatin through ActRIIB is thought to cause negative regulation of skeletal muscle mass; therefore, blocking the interaction of myostatin with ActRIIB will induce skeletal muscle hyperplasia and/or hypertrophy (Kambadur et al. 1997; McPherron et al. 1997; Zhu et al. 2000; Lee and McPherron 2001; Gonzalez-Cadavid and Bhasin 2004). Inhibitors of ActRIIB signaling may prevent or reverse the age-related loss of muscle mass that contributes to sarcopenia and may also be useful for the treatment of muscular dystrophy, cachexia, and diabetes mellitus (Walsh and Celeste 2005).

Although structural studies of the extracellular domain (amino acid residues 1–120 and 1–98) of ActRIIB from mouse in complex with activin have been described (Thompson et al. 2003; Greenwald et al. 2004), the three-dimensional structure of the cytoplasmic domain of ActRIIB that contains the catalytic kinase domain has not been disclosed previously.

Toward an understanding of the molecular mechanism of ActRIIB and its specificity, we determined the structure of the cytoplasmic kinase domain of ActRIIB from human. Our results provide an insight into the formation of the enzyme–substrate complex and a basis for the rational design of selective inhibitors of intracellular signaling by ActRIIB.

Results and Discussion

Overall structure

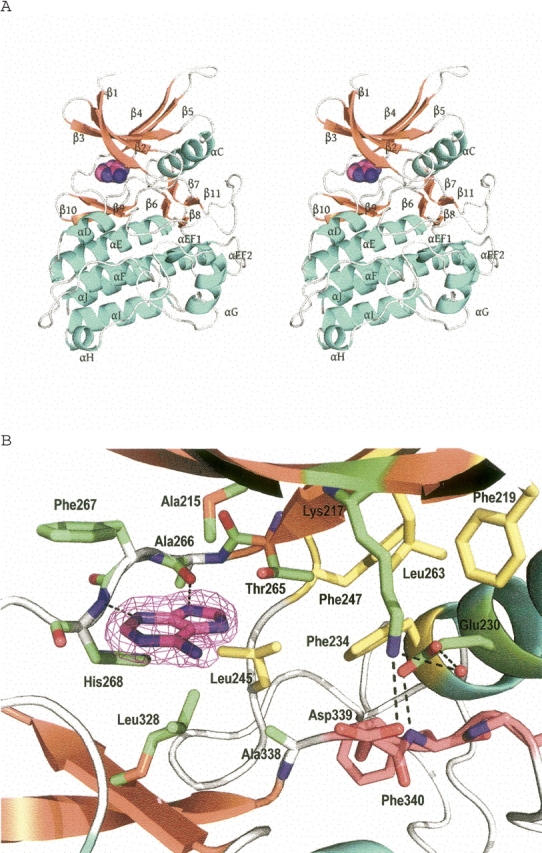

The crystal structure of unphosphorylated human ActRIIB kinase domain was determined at 2.0 Å resolution by molecular replacement methods using the structure of human TßRI (Huse et al. 2001) (PDB entry 1IAS) as the search probe. A summary of data collection and refinement statistics is reported in Table 1. The overall structure is similar to that of all other kinase catalytic domains, displaying a bilobal architecture. The smaller N-terminal lobe contains a five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet and a single α−helix (αC). The larger C-terminal lobe is mostly α-helical and contains the activation loop involved in polypeptide substrate binding. N- and C-terminal lobes are connected by the so-called hinge sequence, which partially defines the binding site for ATP and ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors (Fig. 1).

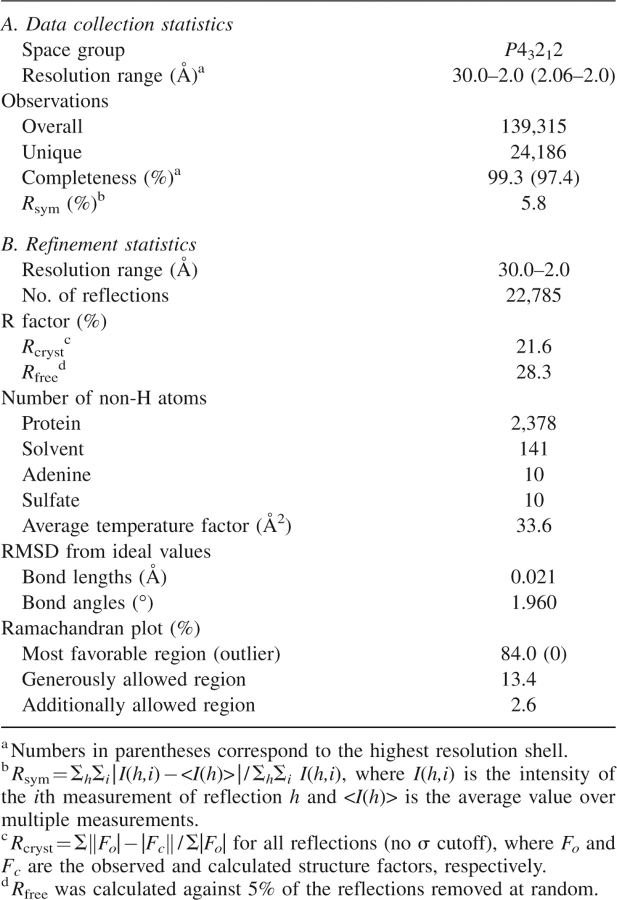

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for ActRIIB–adenine complex

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional structure of ActRIIB-adenine complex from human. (A) Stereoview of the ActRIIB–adenine complex. Secondary structure elements are shown in cyan (α-helices), orange (β-strands), and gray (loops). The bound adenine is shown as spheres. (B) Active site of ActRIIB bound to adenine. The Fo-Fc omit map contoured at 3.0 σ (magenta) is shown for the adenine. The hydrogen bonds are indicated by broken lines. DFG motif is shown in pink, and residues involved in lipophilic pocket are shown in yellow.

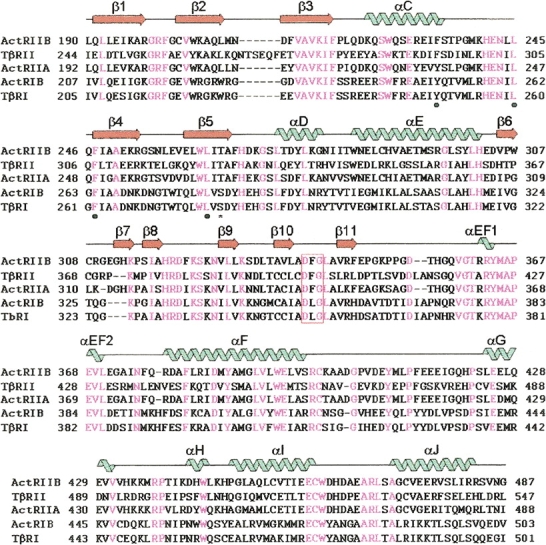

The catalytic domains of the ActRIIB and TßRI share about 39% sequence identity. Least-squares Cα superposition of the ActRIIB and TßRI kinase domain reveals this similarity and yields an overall RMSD value of 1.2 Å for 281 Cα atom pairs. Differences in the Cα backbones are more pronounced in solvent-exposed loops: residues 254–259 (connecting β4 to β5; RMSD = 2.4 Å), residues 308–310 (connecting β6 to β7; RMSD = 4.4 Å), and residues 347–361 (connecting β11 to αEF1; RMSD = 4.0 Å). The activation loop (residues 339–368), which exhibits substantial sequence variation and flexibility among the kinases, clearly distinguishes ActRIIB from TßRI (Fig. 2). In both FKBP12-bound TßRI and TßRI–NPC-30345 complexes, the activation loop forms a β-hairpin (β9 and β10) that is supported by a one and a half turn extension of the αF-helix (Huse et al. 1999, 2001). In the adenine-bound ActRIIB structure, however, the β-hairpin is absent and the equivalent β11 is directly connected to an additional one and a half turn helix (αEF1) (Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

A structure-based sequence alignment of the ActRIIB with other type I and type II receptor kinase domains (ActRIIA, ActRIB, TßRI, and TßRII). Secondary structure elements of the ActRIIB are represented by “noodles” (α-helices) and “arrows” (β-strands). They are colored blue for helices and orange for strands. Identical residues are highlighted in magenta. The DFG motif is boxed in red. The conserved residues involved in forming the back pocket are shown as “•” below the sequences. The gatekeeper residue is shown as “*” below sequences.

Similar to the TßRI structure, the α-helices in the C-terminal lobe display the same catalytic segment lowering and αE-helix bulge characteristic of tyrosine kinase, which may explain how actRIIB can function as a dual-specificity kinase under certain conditions. Endogenous activin type II receptor purified from mammalian cells exhibited not only serine and threonine, but also tyrosine kinase activity (Nakamura et al. 1992). However, the recombinant activin type II receptors have been reported to only have serine and threonine kinase activity (Mathews and Vale 1993).

Active site

The ATP-binding sites of protein kinases are the most common targets for the design of small-molecule inhibitors. Discovery and optimization of the ATP-competitive inhibitors had been perceived as a difficult obstacle to overcome due to the highly conserved nature of the ATP-binding site between kinase domains. However, small structural differences and plasticity between the ATP-binding sites of even closely homologous kinases have been successfully exploited to achieve selectivity and potency (Wang et al. 1998; Noble and Endicott 1999). In the ActRIIB structure, the bound adenine has a considerably different orientation from that of the adenine moiety of ATP observed in other kinase structures (Nighton et al. 1991). Adenine inserts into a hydrophobic pocket formed by the side chains of Ala215, Leu245, Phe267, Leu328, and Ala338. In contrast to the adenine moiety of ATP, which makes interactions through the N1 nitrogen and amino group, the N3 nitrogen and the protonated N9 of the adenine ring hydrogen bond to the main chain of Ala266 and His268, respectively (Fig. 1). The amino group of adenine is solvent exposed and does not make any interactions with the protein. The different binding mode of adenine seen here for ActRIIB, when compared with the binding of the adenine moeity of ATP binding seen in many other kinases, is due to the lack of additional inter-reactions with the ribose-phosphate moieity and the presence of tautomers with two different protonation states at the N9 nitrogen. The mixed population of the two tautomers have been observed in solution studies (Saenger 1983).

In a large number of kinase structures, the proximity of αC-helix to the active site and its interactions with many conserved and essential kinase elements plays a central role in kinase regulation (Sicheri and Kuriyan 1997). In the ActRIIB–adenine structure, the conserved salt bridge between Glu230 from αC-helix and Lys217 from the β3-strand is absent. Instead, Glu230 forms a water-bridged hydrogen bond with Lys217 and a hydrogen bond with the backbone amine of Phe340, which is part of the conserved DFG sequence that marks the N-terminal end of the activation loop. Despite the absence of the Lys217–Glu230 salt bridge, the adenine binding induces the unphosphorylated activation loop to adopt a conformation similar to that of the fully active form (Fig. 1).

A conserved “gatekeeper residue,” Thr265, connecting the N-terminal domain and the hinge loop (Ala266–Gly271) plays an important structural role and forms a water-bridged hydrogen bond with the carbonyl backbone of Leu263 and is involved in forming an additional lipophilic pocket with Phe234, Leu245, and Phe247. This lipophilic subpocket, referred as the “back pocket,” is adjacent to the ATP-binding site and has been considered in the design of other kinase inhibitors (Noble et al. 2004).

Active-site comparision to type I receptor kinase domain

Gln358, the conserved residue in the activation loop of ActRIIB and TßRII, is stabilized by hydrogen bonds with carbonyl backbones of Val369 and Leu370. The structurally equivalent residue, however, Arg372 in TßRI–FKBP12 complex, disrupts the ATP-binding site by extending its side chain into the catalytic center and forming an ion pair with Asp351, an important ligand for interacting with a magnesium ion (Huse et al. 1999). Thr265, the gatekeeper residue in ActRIIB, is larger than the analogous Ser280 in TßRI (Fig. 2). In the crystal structure of TßRI complexed with NPC-30345, the size of the side chain of the gatekeeper residue plays an important role in the specificity of NPC-30345 for TßRI (Huse et al. 2001).

Importantly, a conserved residue, Phe234 at the end of the αC-helix, is involved in forming a back pocket and plays a structural role by forming hydrophobic interactions with the two phenylalanine residues, Phe247 in the β4-strand and Phe340 in the conserved DFG motif. In contrast, TßRI bears a tyrosine residue, Tyr249, which has to move into the rear of the ATP-binding pocket to convert the N-terminal lobe into catalytically active conformation (Huse et al. 2001). The Tyr249 in the TßRI crystal structure is involved in hydrophobic interaction with Phe262 and Leu362, and is further stabilized by a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl backbone of Leu260.

In conclusion, the crystal structure of the human ActRIIB–adenine complex reveals that the unphosphorylated activation loop adopts a conformation similar to that of the fully active form, without the formation of the commonly observed Lys217–Glu230 salt bridge. The AcRIIB kinase domain from human represents a distinct type II receptor serine/threonine kinase subfamily identifiable in part by common features such as Thr265 as a gatekeeper residue and a back pocket supported by Phe247. The human ActRIIB kinase domain structure thus provides a basis for a more integrated understanding of the substrate recognition process, catalysis, and the development of small-molecule inhibitors.

Materials and Methods

Protein cloning, expression, and purification

Expression vector pMCG263 was prepared by ligating the ActRIIB cytoplasmic domain of residues 190–487 into BamHI and HindIII sites of a backbone vector containing the polylinker from the pFastBac vector (Invitrogen) and N-terminal His6 tag and thrombin cleavage sites. The resulting pMCG263 vector contained a nucleotide sequence encoding the ActRIIB cytoplasmic domain preceded by a start codon, His6 tag, and thrombin cleavage site, and terminated with two stop codons. The pMCG263 was transfected into Sf9 cells according to methods recommended by the manufacturer.

About 94 g (10 L) of cell paste of ActRIIB B263 construct expressed in Sf9/baculovirus cells were reconstituted in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8), 300 mM KCl, 5 mM TCEP (Tris[2-carboxyethyl] phosphine), complete protease inhibitors-EDTA free (Roche), and 10% glycerol at 1:5 cell/buffer ratio. The cells were mechanically lysed and the crude lysate cleared by centrifugation at 30,000g for 45 min at 4°C. The cleared lysate containing the soluble ActRIIB B263 protein was treated with Ni-NTA Superflow resin in a batch-binding mode, and the resultant protein:resin complex transferred to an XK column. The column was washed with lysis buffer. The bound ActRIIB protein was eluted with lysis buffer containing imidazole. Immediately prior to elution of the bound protein with imidazole (100 mM), a pre-equilibrated desalting column (Hi-Prep 26/10) was connected to remove imidazole. Purity and mass of the eluted ActRIIB was determined by SDS-PAGE analysis and LC-MS. Typically, a 10-L affinity purification preparation resulted in about 36 mg total of ActRIIB B263 protein. An aliquot of affinity-purified protein (about 16 mg) was then subjected to size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) with Superdex-200 column in buffer containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8), 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM TCEP, and 5% glycerol (v/v). The affinity and SEC-purified protein resulted in a highly pure protein with a molecular weight of 35,789.7 Da demonstrated by LC-MS, which matched the theoretical mass of the acetylated ActRIIB. Peak fractions were pooled and centrifuged at 13,000g for 45 min at 4°C to remove any particulate material. A typical SEC purification resulted in ∼50%–60% protein recovery. The protein was homogenous and monomeric as demonstrated by ultracentrifugation analysis (data not shown).

Crystallization of ActRIIB

For crystallization of the adenine–protein complex, 1 mL (0.935 mg/mL) of purified ActRIIB protein was used, to which a final concentration of 2 mM of adenine (33 uL of 60 mM stock in 0.1 N HCl) was added and then concentrated to about 100 μL.

Crystallization conditions were initially identified using a Hampton Research screening kit. Optimized crystals were grown at 22°C by vapor diffusion in hanging-drop plates with equal volumes of protein–adenine solution (0.935 mg/mL protein, 2 mM adenine) containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM TCEP, 5% glycerol (v/v), and reservoir solution containing 45 mM MES (2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid) (pH 6.5), 90 mM ammonium sulfate, 11%–14% polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether 5000 (w/v). Microseeding was used to produce larger, single crystals.

Data collection

The ActRIIB crystals complexed with adenine were transferred to a cryoprotectant solution composed of the reservoir solution containing 15%–25% ethylene glycol (v/v), and then flash-frozen in a stream of nitrogen gas at 100 K. A full data set was collected from a single crystal frozen in this manner at the Advanced Photon Source of Argonne National Laboratory on a ADSC Quantum 210 CCD detector. Data was processed using the HKL2000 suite of software (Otwinowski and Minor 1997). Data collection statistics are summarized in Table 1. The crystals belong to space group P43212 with unit cell dimensions a = b = 98.22 Å, c = 71.35 Å, α = β = γ = 90°, and contain one molecule of the polypeptide per asymmetric unit.

Structure determination

The structure of ActRIIB–adenine complex was solved by molecular replacement methods with the CCP4 version of AmoRe (Navaza 1994), using TßR-1 molecule (PDB code 1IAS) as a search model (correlation coefficient = 42.7% and R-factor = 51.0% for 15.0–3.0 Å resolution data). After molecular replacement, maximum likelihood-based refinement of the atomic position and temperature factors was performed with REFMAC (Murshudov et al. 1997) and the atomic model was built using the program O (Jones et al. 1991). Water molecules were first placed automatically using REFMAC/ARP (Perrakis et al. 1999) and verified manually. The final refined model of the ActRIIB–adenine complex includes residues 190–484 and two additional N-terminal residues that resulted from the recombinant expression system used. The stereochemical quality of the final model was assessed by PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993). Crystallographic statistics for the final model are shown in Table 1. Structural alignments with ActRIIB and TßR-1 were performed using the lsq options in O (Jones et al. 1991). Figures were prepared with PyMOL (DeLano 2002).

Coordinates

The coordinate for the ActRIIB–adenine complex structure has been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 2QLU.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dwight McGuire for help with the protein production and Drs. Jay Pandit, Xiayang Qiu, Shenping Liu, Felix Vajdos, and Andrew Seddon for insightful discussions.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Seungil Han, Pfizer, Inc., Pfizer Global Research and Development, Eastern Point Road, Groton, CT 06340, USA; e-mail: seungil.han@pfizer.com; fax: (860) 686-2095.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.073068407.

References

- Attisano L., Wrana, J.L., Montalvo, E., and Massagué, J. 1996. Activation of signaling by the activin receptor complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 1066–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W.L. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system, DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA, http://www.pymol.org.

- Donaldson C.J., Mathews, L.S., and Vale, W.W. 1992. Molecular cloning and binding properties of the human type II activin receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 184: 310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham H. and Peng, C. 2006. Activin receptor-like kinases: Structure, function and clinical implications. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 6: 45–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald J., Vega, M.E., Allendorph, G.P., Fischer, W., and Choe, S. 2004. A flexible activin explains the membrane-dependent cooperative assembly of TGF-β family receptors. Mol. Cell 15: 485–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse M., Chen, Y.-G., Massagué, J., and Kuriyan, J. 1999. Crystal structure of the cytoplasmic domain of the type I TGF-β receptor in complex with FKBP12. Cell 96: 425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse M., Muir, T.W., Xu, L., Chen, Y.-G., Kuriyan, J., and Massagué, J. 2001. The TGF-β receptor activation process: An inhibitor-to substrate-binding switch. Mol. Cell 8: 671–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou, S.W., Cowan, S.W., and Kjeldgaard, M. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallog. Sect. A 47: 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambadur R., Sharma, M., Smith, T.P., and Bass, J.J. 1997. Mutations in myostatin (GDF8) in double-muscled Belgian Blue and Piedmontese cattle. Genome Res. 7: 910–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., MacArthur, M.W., Moss, D.S., and Thornton, J.M. 1993. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24: 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.J. and McPherron, A.C. 2001. Regulation of myostatin activity and muscle growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 9306–9311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J., Blain, S.W., and Lo, R.S. 2000. TGF-β siginaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell 103: 295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews L.S. and Vale, W.W. 1991. Expression cloning of an activin receptor, a predicted transmembrane kinase. Cell 65: 973–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews L.S. and Vale, W.W. 1993. Characterization of type II activin receptors: Binding, processing and phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 19013–19018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron A.C., Lawler, A.M., and Lee, S.J. 1997. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-β superfamily member. Nature 387: 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G.N., Vagin, A., and Dodson, E.J. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structure by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallog. Sect. D. 53: 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T., Sugino, K., Kurosawa, N., Sawai, M., Takio, K., Eto, Y., Iwashita, S., Muramatsu, M., Titani, K., and Sugino, H. 1992. Isolation and characterization of activin receptor from mouse embryonal carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 267: 18924–18928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza J. 1994. AmoRe: An automated package for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallog. Sect. A. 50: 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Nighton D.R., Zheng, J., Ten Eyck, L.F., Ashford, V.A., Xuong, N.-H., Taylor, S.S., and Sowadski, J.M. 1991. Crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Science 253: 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble M.E. and Endicott, J.A. 1999. Chemical inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases: Insights into design from X-ray crystallographic studies. Pharmacol. Ther. 82: 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble M.E., Endicott, J.A., and Johnson, L.N. 2004. Protein kinase inhibitors: Insights into drug design from structure. Science 303: 1800–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. and Minor, W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276: 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A., Morris, R., and Lamzin, V.S. 1999. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6: 458–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenger W. 1983. Principles of nucleic acid structure. Springer-Verlag, New York.

- Shi Y. and Massagué, J. 2003. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 113: 685–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki H., Ito, I., Hasegawa, Y., Nakamura, K., Igarashi, S., Nakamura, M., Miyamoto, K., Eto, Y., Ibuki, Y., and Minegishi, T. 1992. Cloning and sequencing of a rat type II activin receptor. FEBS Lett. 312: 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicheri F. and Kuriyan, J. 1997. Structures of Src-family tyrosine kinases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7: 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T.B., Woodruff, T.K., and Jardetzky, T.S. 2003. Structures of an ActRIIB:activin A complex reveal a novel binding mode for TGF-β ligand:receptor interactions. EMBO J. 22: 1555–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida K. 2004. Activins, myostatin, and related TGF-β family members as novel therapeutic targets for endocrine, metabolic, and immune disorders. Curr. Drug Target Immune Endocr. Metabol. Disord. 4: 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F.S. and Celeste, A.J. 2005. Myostatin: A modulator of skeletal-muscle stem cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33: 1513–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Canagarajah, B.J., Boehm, J.C., Kassisa, S., Cobb, M.H., Young, P.R., Abdel-Meguid, S., Adams, J.L., and Goldsmith, E.J. 1998. Structural basis of inhibitor selectivity in MAP kinases. Structure 6: 1117–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Hadhazy, M., Wehling, M., Tidball, J.G., and McNally, E.M. 2000. Dominant negative myostatin produces hypertrophy without hyperplasia in muscle. FEBS Lett. 474: 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]