Abstract

The previous design of an unprecedented family of two-, three-, and four-helical, right-handed coiled coils utilized nonbiological amino acids to efficiently pack spaces in the oligomer cores. Here we show that a stable, right-handed parallel tetrameric coiled coil, called RH4B, can be designed entirely using biological amino acids. The X-ray crystal structure of RH4B was determined to 1.1 Å resolution using a designed metal binding site to coordinate a single Yb2+ ion per 33-amino acid polypeptide chain. The resulting experimental phases were particularly accurate, and the experimental electron density map provided an especially clear, unbiased view of the molecule. The RH4B structure closely matched the design, with equivalent core rotamers and an overall root-mean-square deviation for the N-terminal repeat of the tetramer of 0.24 Å. The clarity and resolution of the electron density map, however, revealed alternate rotamers and structural differences between the three sequence repeats in the molecule. These results suggest that the RH4B structure populates an unanticipated variety of structures.

Keywords: protein design, parameterized backbone, structural uniqueness, core packing

Computational protein design methods are increasingly identifying sequences that adopt conformations close to the predicted structure. This increased accuracy of structural predictions in design has enabled the production of new folds with high stability (Harbury et al. 1998; Kuhlman et al. 2003), specific ligand-binding sensors (Looger et al. 2003), and novel enzymes with considerable catalytic power (Bolon and Mayo 2001; Chevalier et al. 2002; Dwyer et al. 2004). Increasing the accuracy of computational designs has required new approaches to model backbone and side-chain flexibility. In the creation of the “Top7” protein with a novel α/β fold, for example, adjustment of the backbone proved a critical step in the design process (Kuhlman et al. 2003). Similarly, in the design of the RH family of right-handed coiled coils, backbone movements restrained to populate a continuous family of symmetric, infinite, rope-like coils were essential to minimize the energies of each sequence in alternate oligomeric states (Harbury et al. 1998).

Backbone variation is computationally challenging to model. An initial approach to overcome the combinatorial complexity of possible backbone conformations employed Crick's classic mathematical parameterization (Crick 1953b) to model the structures of coiled coils based on just seven adjustable parameters (Harbury et al. 1995). This economy allowed large structures to be modeled using an energetic penalty for deviations from an ideal coiled-coil backbone. Moreover, the common left-handed coiled coils comprise a simple, seven-residue repeat (a–g) with hydrophobic residues in the first and fourth (a and d) positions. This short sequence pattern dramatically simplified the sequence choices in design. Variations in the a and d residues were found to be sufficient to drive the formation of two-, three-, and four-helical coiled coils by packing into the inherently different core spaces in the different oligomers (Harbury et al. 1993, 1995; Zhu et al. 1993).

The heptad repeat causes the left-handed superhelical twist, because the seven-residue hydrophobic periodicity trails the 7.2 residues that form two full helical turns. The importance of this periodicity was tested in the design of a family of right-handed coiled coils that had not been observed in nature (Dure III 1993; Harbury et al. 1995, 1998). The right-handed architecture was based on a repeat of 11 residues (called a–k) with hydrophobic amino acids at positions a, d, and h. The 11 amino acids sweep out 1100° in an α-helix, leading three full turns by 20°. This mismatch encourages a right-handed superhelical twist that places the hydrophobic residues in the core. In the original design of the RH family, however, sequences containing nonbiological core amino acids were predicted to form the most stable and specific structures, because the biological residues failed to fill the core spaces as well in symmetric dimer, trimer, and tetramer structures.

Here we explore the ability of a homologous 11-amino acid repeat composed entirely of biological amino acids to form a right-handed tetramer. The designed sequence containing the residues ile, ala, and ile at the a, d, and h core positions was predicted to pack more stably into a tetramer than a trimer or dimer. A 33-residue peptide, RH4B (RH4 Biological), comprising three repeats formed a tetramer in solution that was less stable than the previously characterized RH4 tetramer containing allo-ile in the core. RH4B crystallized as a tetramer with the monomers related by crystallographic fourfold symmetry. Crystallization depended on inserting a metal binding site pioneered in the RH3 design (Plecs et al. 2004) composed of γ-carboxyglutamate residues spaced four residues apart on the helix surface. The binding of a single Yb2+ ion per monomer yielded an extraordinarily accurate, experimental electron density map at 1.1 Å resolution. The structure closely matched the design, with an overall right-handed superhelix and a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) from the design of 0.24 Å for the core residues and backbone of the N-terminal 11-residue repeat. In contrast to the elegant simplicity of the design, however, the high resolution and accuracy of the electron density map revealed not only variation among repeats in the structure, but also showed many residues adopted multiple rotamers. This heterogeneity was not accounted for directly in the design process, and may reflect the absence of biological selection for a unique structure.

Results

We adopted the general design process used previously to create the RH coiled coils (Harbury et al. 1998; Plecs et al. 2004). An 11-residue poly-alanine sequence was decorated at the a, d, and h positions with all combinations of the major rotamers of gly, ala, leu, ile, val, and met. The energy of each rotamer combination was minimized in two-, three-, and four-helical structures using a simple potential function consisting of a van der Waals term and a penalty for deviations from an ideal coiled-coil backbone. The van der Waals potential captured most of the variance in the calculated energies of the RH family design. The rotamer combination that produced a stable calculated tetramer and simultaneously was calculated to form a relatively unstable dimer or trimer was chosen for synthesis. This sequence, containing ile at a, ala at d, and ile at h, embodied stability and specificity for the target structure.

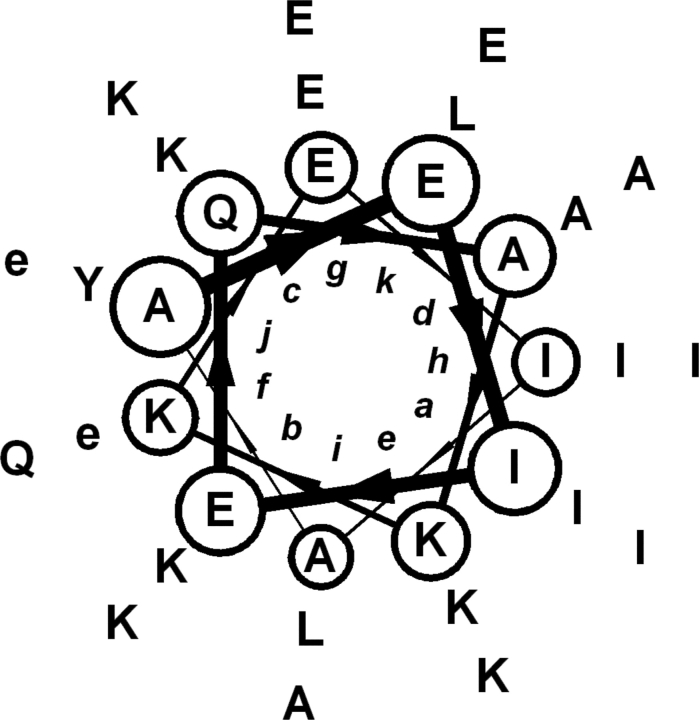

RH4B, a terminally blocked, 33-amino acid synthetic peptide containing three 11-mer repeats was synthesized using the same template sequence used previously in the RH family (Fig. 1; Plecs et al. 2004). This template contained charged or polar residues (lys, gln, or glu) at surface positions to increase the solubility and discourage antiparallel oligomerization through charge repulsion (Harbury et al. 1998). A tyr residue was also included as a UV absorbing reference, and surface glutamates 19 and 23 were replaced with γ-carboxyglutamic acid (gla or lowercase “e”) to facilitate metal binding for phase determination. This (i, i + 4) arrangement of gla residues was used previously in the RH3 coiled coil to bind Ni2+ or Co2+ for phasing the X-ray data (Plecs et al. 2004). Inserting the designed I-A-I designed core into the template gave the following sequence for RH4B: Ac-AEIEQAKKEIAYLIKKAKeEILeEIKKAKQEIA-Am, where the core positions are underlined.

Figure 1.

Sequence of the designed RH4B tetramer. Helical wheel representation starting with Ala1 at a j position shows each of the three 11-mer repeats in successive layers. Ile (a and h) or Ala (d) were placed at the core positions to favor tetramer formation. The surrounding template sequence was used previously in the design of the RH family of right-handed coiled coils (Harbury et al. 1998; Plecs et al. 2004). The charge pattern confers solubility and deters the formation of antiparallel oligomers. The lowercase “e” designates γ-carboxyglutamate, inserted at positions 19 and 23 to create a metal binding site.

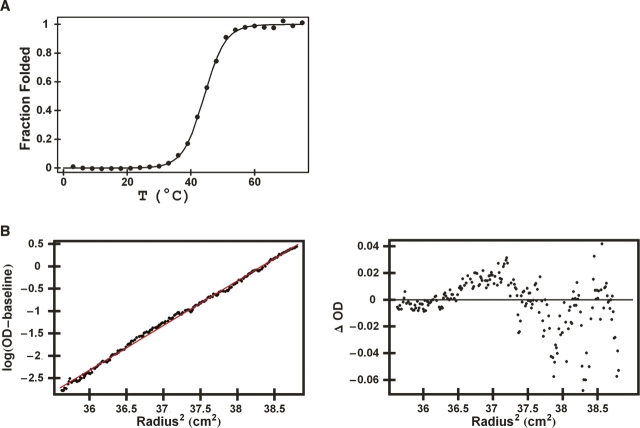

At 20-μM peptide concentration at pH 5.2, RH4B gave a helical CD spectrum, and thermal denaturation experiments indicated a Tm of >80°C (data not shown). Addition of 1 M guanidinium hydrochloride (GuHCl) reduced the Tm to 44°C (Fig. 2A). Analytical ultracentrifugation at an average peptide concentration of 300 μM showed that RH4B formed a tetramer in solution (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

RH4B forms a stable tetramer in solution. (A) Thermal melt in 1 M GuHCl monitored by circular dichroism revealed a Tm of 44°C at 20 μM peptide in 50 mM NaAc (pH 5.2), 50 mM ammonium sulfate, and 20 mM EDTA. The EDTA was present to remove any trace metals from the tetramer. (B) Equilibrium sedimentation data collected at 35,000 rpm at 25°C using 300 μM of RH4B in 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.2, 50 mM ammonium sulfate, and 20 mM EDTA. The logarithm of the baseline-corrected absorbance is plotted against the square of the radial position in the rotor. The solid line corresponds to a tetramer. The residuals from the tetramer fit are shown in the panel on the right. Fits using combinations of monomeric, dimeric, trimeric, tetrameric, hexameric, and octameric states did not reduce the residuals.

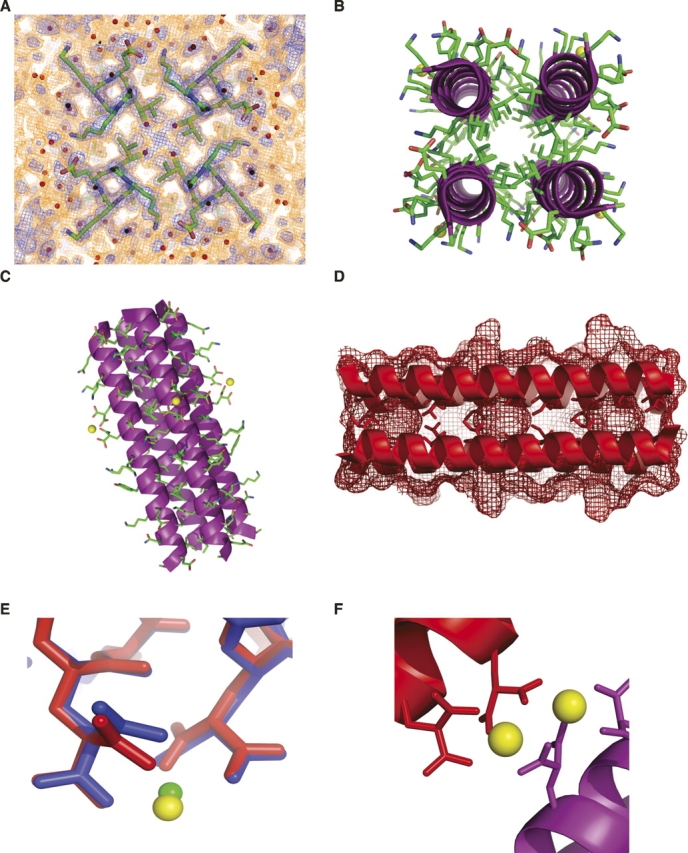

X-ray structure of RH4B

To explore the accuracy of the design, we determined the crystal structure of RH4B. No RH4B crystals grew in the absence of metals, but addition of 10 mM YbCl2 produced crystals that diffracted X-rays beyond 1 Å resolution. Multiwavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) phases were calculated to 1.3 Å resolution and extended to 1.1 Å resolution using RESOLVE (Terwilliger 2000). Because of the large number of electrons in the Yb2+ ion in comparison to the small size of the RH4B monomer, the experimental phases were extraordinarily accurate (Table 1). The mean figure of merit of the experimental phases to 1.3 Å resolution was 0.95, and the average anomalous phasing power of the derivative exceeded 9 (Table 1). As a consequence, the experimental electron density map provided a particularly accurate view of the tetramer with no bias from the model (Fig. 3A). The model was refined to R/R free values of 0.130/0.145 at 1.1 Å resolution, and the model and experimental phases had a correlation coefficient of 0.735.

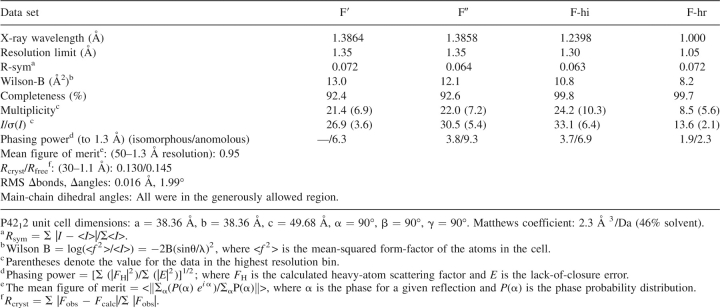

Table 1.

Crystallographic statistics for RH4B space group

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of RH4B. (A) Experimental electron density map at 1.1 Å resolution contoured at 1 σ (blue) and 0.3 σ (red) showing residues 7–10. These residues include an h residue in the core (Ile10). The electron density map shows apparent multiple rotamers for all four residues—Lys7, Lys8, Glu9, and Ile10—although only the density surrounding Ile10 was strong enough to justify building the alternate conformer in the model. (B) Axial view of the RH4B tetramer showing the right-handed twist of the N-terminal part of the coiled coil. (C) Side view of the tetramer. (D) RH4B tetramer ribbon diagram superimposed on surface contours shows core cavities bordered by Ala in the d position of all three 11-mer repeats. The core residues are shown in stick representation. (E) Superposition of the i, i + 4 metal binding sites in RH4B (red) and RH3 (blue). Compared to the bound Co2+ in RH3, the larger Yb2+ ion caused a rotation in χ2 of Gla19 and bound farther away from the helix. Metal-coordinated water molecules were omitted for clarity. (F) Adjacent Yb2+ ions bridged neighboring tetramers (blue and red) in the RH4B crystals.

The overall structure of RH4B (Fig. 3) formed the intended parallel, tetrameric coiled coil. The crystals contained one monomer per asymmetric unit, with the monomers related by crystallographic fourfold rotational symmetry. All residues and the terminal acetyl and amide groups were ordered. The helix extended from Glu2–Ala33. Unlike the RH3 structure, the N-acetyl and C-terminal amide did not cap the helix.

The core contained cavities corresponding to the alanine in the d position in the repeat (Fig. 3D). Water molecules were modeled inside these cavities, but the location of the crystallographic fourfold axis limits the interpretation of the electron density in the cavities. The charged residues in the e and g positions formed interhelical ion pairs. The distances between the terminal amino group of lys in the e positions and a carboxylate oxygen of glu in the g positions were 3.65 Å, 2.59 Å, and 2.79 Å, respectively, in repeats 1–3 (e.g., Fig. 3A).

The engineered metal binding site occurred on the surface of the tetramer at the boundary between the second and third 11-mer repeat (Fig. 1). As intended, the two γ-carboxyglutamate side chains coordinated the Yb2+ ion (Fig. 3E). The local metal coordination is similar to that observed in the structure of the RH3 trimer, which was analyzed with bound Ni2+ or Co2+ (Plecs et al. 2004). Unlike in the RH3 structure, however, this metal binding site also served as the only strong crystal contact between tetramers in the X–Y crystallographic plane (Fig. 3F).

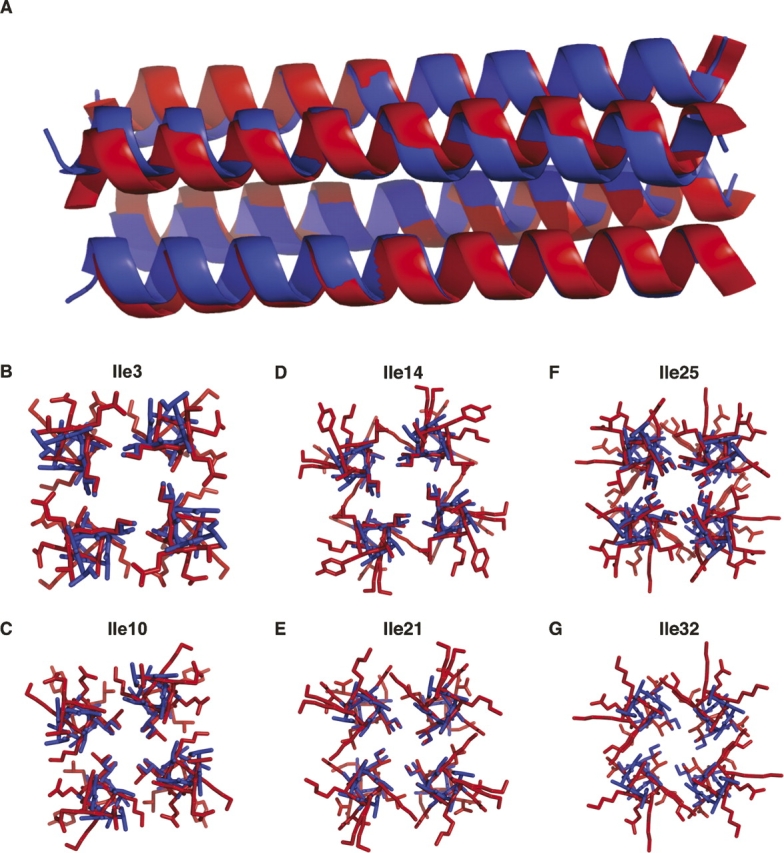

Like RH3 and RH4, RH4B matched the predicted structure with high precision (Figs. 4, 5). The RMSD between the predicted and measured α-carbons for the entire RH4B tetramer structure was 1.19 Å. The matches for the individual repeats ranged from 0.24 Å for the N terminus to 0.78 Å for the C-terminal repeat. All six of the designed core isoleucines adopted the predicted rotamer in the crystal structure (Fig. 4B–D). Overall, the structure showed close agreement with the design in oligomerization, general backbone placement, and rotamer selection.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the observed and designed RH4B structures. (A) Overlay of the ribbons of the designed (blue) and observed (red) structures. The RH4B tetramer structure matches the predicted structure. (B–G) All six of the designed core isoleucines adopted the predicted rotamer.

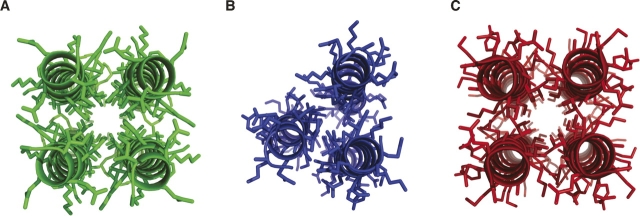

Figure 5.

Three designed right-handed coiled coils. (A–C) The RH4 (green, 1.9 Å resolution) (Harbury et al. 1998), RH3 (blue, 2.0 Å resolution) (Plecs et al. 2004), and RH4B (red) coiled coils were made by inserting different core residues into the same template sequence (Fig. 1). At the a, d, and h positions, RH3 contained alloIle-alloIle-Ile (where alloIle has the opposite side-chain chirality as Ile), RH4 contained Leu-alloIle-Ile and RH4B contained ile-ala-ile. These structures illustrate the diversity of coiled coils accessible by varying only the core amino acids. The RMS deviations between the central 11 amino acids of structures and the designs were 0.20 Å for RH4, 0.74 Å for RH3, and 0.64 Å for RH4B.

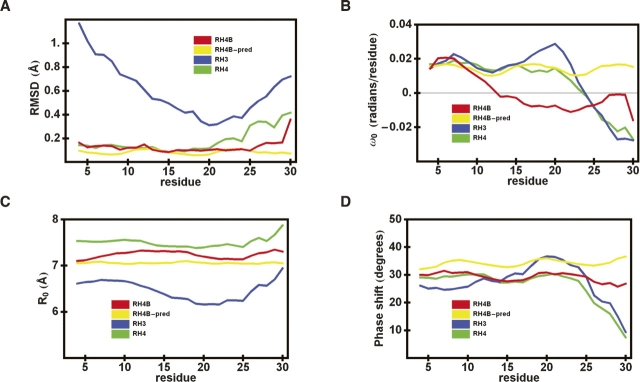

A more sensitive measure of the differences among coiled-coil structures is provided by the superhelical parameters (Fig. 6). For these calculations, the α-carbons of seven sequential residues in each of the helical chains were fit to an ideal superhelix (Harbury et al. 1995). This fit was done for each subsequent set of seven residues, centered on each residue from 4 to 30. The fit of each 7-mer in RH4B to an ideal coiled coil produced a small residual, indicating that short segments of the structure were accurately represented as ideal superhelices.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the superhelical parameters of the RH3 (blue), RH4 (green), and RH4B (red, observed and yellow, designed) coiled coils. Each superhelix was fit in a seven-residue window, centered on the residue given on the X-axis. (A) RMS deviation from an ideal superhelix (Å). (B) Superhelical twist, ω0 (radians/residue). (C) Superhelical radius, R0 (Å). (D) Angle from the h-position, ϕ (°).

The analysis of the superhelical twist (ω0) provided the biggest surprise. The twist is defined so that positive values correspond to a right-handed coiled coil and negative values correspond to a left-handed coiled coil. The RH4B structure unexpectedly straightened (or even became slightly left-handed) in the middle of the sequence, with ω0 values near zero (Fig. 6B). Consistent with this finding, the N-terminal 11 residues, where the coiled coil is right-handed, has a particularly low RMSD of 0.24 Å between the predicted and measured structures, considerably better than the 0.64 Å RMSD in the central region.

The differences in the other superhelical parameters between RH4B and the predicted model are relatively minor. The positioning of hydrophobic residues in the a, d, and h positions oriented the h position toward the central superhelical axis. The angle between the h position and the superhelical axis is equal to 7π/11-φ (Harbury et al. 1998). The φ angle and the superhelical radius (R0) of RH4B agree well with the predicted structure (Fig. 6C,D). By comparison, the RH3 and RH4 structures illustrate the ranges of these parameters accessible in the RH coiled coils (Figs. 5, 6).

Discussion

The design of RH4B succeeded on several levels. The sequence repeat comprised entirely of biological amino acids formed the intended parallel, tetrameric, right-handed coiled coil with the calculated core packing. The N-terminal 11-amino acid repeat, in particular, showed an RMSD for all atoms in the design of 0.24 Å. Not only did the metal binding site accommodate Yb2+ within the intended structure, the resulting experimental phases were among the most accurate reported for any protein structure. These results strengthen the hypothesis that this method of phasing is likely to be applicable generally to solvent-exposed helices in synthetic systems. The backbone RMSD between the observed structure and the design of RH4B was similar to that of the RH3 and RH4 coiled coils (Fig. 5).

Even with the unexpected straightening of the superhelical twist (Fig. 6B), the entire RH4B backbone remained within 1.19 Å of the predicted backbone. Moreover, the core rotamers adopted the predicted conformation. That the a, d, and h residues determined the oligomerization state of RH4B is consistent with earlier findings that core packing is sufficient to define the structural specificity of coiled coils (Harbury et al. 1993; Zhu et al. 1993; Harbury et al. 1994). The core of RH4B contained three packing defects, which occurred at the d position ala residues. Despite the predicted cavity in RH4B, the design calculation selected ala at the d position, because rotamers of the other sampled core residues left a larger cavity (gly) or fit better in alternate oligomers. The core defects perhaps contributed to the lower stability of RH4B compared to RH4, which denatured at ∼90°C in 3 M GuHCl (Harbury et al. 1998). The overall consistency of the RH4B structure and design highlights the utility of Crick's original backbone parameterization for modeling coiled-coil structures (Crick 1952, 1953a,b).

A naturally occurring, parallel, tetrameric coiled coil occurs in the tetrabrachion protein of the marine bacterium Staphylothermus marinus. Like the RH family, the tetrabrachion sequence contains an 11-amino acid pattern with hydrophobic residues (mostly ile, ala, val, and leu) in the a, d, and h positions. Unlike the RH4 repeat, however, ala occurs at the a positions in the 3-4-4 hydrophobic repeats in tetrabrachion. The d position contains mostly leu and ile residues, rather than the smaller ala. The structure of a 52-amino acid segment of the tetrabrachion coiled coil (Stetefeld et al. 2000) shows that the N-terminal 18 residues formed a right-handed superhelix (twist [ω0] = + 0.05 radians/residue). Like the C-terminal part of the RH4B structure, however, the last 34 amino acids formed a nearly straight helical bundle (−0.01 < ω0 < 0.01 radians/residue). The Cα RMSD of residues 2–33 of the RH4B tetramer with residues 7–38 from the 52-residue segment of the tetrabrachion coiled coil was 1.29Å. Thus, despite the continuous 3-4-4 pattern of hydrophobic side chains in RH4B and tetrabrachion, a continuous, parallel right-handed coiled coil was not formed in either structure. The transition to a straight helical bundle in tetrabrachion and RH4B contrast sharply with the continuous left-handed coiled coils formed by seven-residue repeats in numerous proteins.

The changes in the superhelical parameters along the RH4B structure reflected differences in the conformations of the repeats. Despite the strict fourfold symmetry of the structure, the RMSD between 11-mer repeats ranged from 0.24 to 0.78 Å. Moreover, 6/33 residues were modeled in alternate rotamers, and Glu4 was not visible beyond Cγ. Weak features in the experimental electron density map apparently corresponding to alternate rotamers were seen at most other positions (e.g., Fig. 1A), but including these conformations in the model did not lower the free R-value (data not shown). The presence of alternate structures emphasizes the variability in alternate structures accessible to the RH4B sequence. This variability may reflect that only the core residues were evaluated in the design calculations and the sequence was not subjected to any evolutionary process that may favor a more unique local structure.

Materials and Methods

RH4B sequence design

The RH4B sequence selection paralleled the methods used in the previously described computational design of the RH family of right-handed coiled coils (Harbury et al. 1998; Plecs et al. 2004). Briefly, the parameterized backbone method was used to maximize the predicted stability and specificity for forming a tetrameric, right-handed coiled coil. This optimization was initiated by taking an 11-residue sequence with periodic boundary conditions and setting all residues outside the core (i.e., not in the a, d, or h positions) to alanine. All permutations of the most abundant rotamers of gly, ala, leu, ile, val, and met were substituted into the a, d, and h positions in ideal homo-dimeric, homo-trimeric, or homo-tetrameric right-handed superhelical conformations, for a total of 3 × 63 = 648 permutations.

Each of these models was refined by minimizing a simple energy function, which consisted of the CHARMM19 van der Waals energy term (Brooks et al. 1983) plus a parameterization term that restrained the model to the family of coiled-coil backbones (Harbury et al. 1998; Plecs et al. 2004). Geometric constraints on covalent bonds (bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral restraints) were included, but charge and solvent effects were not. The additional parameterization term consisted of a harmonic energetic penalty for the deviation of each α-carbon in the model from an ideal superhelix (Harbury et al. 1995). This additional energy term is the signature of the parameterized backbone technique, and it has been shown to relieve the otherwise intractable search problem by restraining the search space to a low-dimensional manifold. This total effective energy function was minimized for each of the 648 initial structures through a sequence of Powell minimizations using XPLOR (Brunger 1992). These refined models were then compared for relative stability in the core by examining the respective minima of this simplified energy function. The ile-ala-ile pattern for the a, d, and h positions, respectively, yielded good predicted stability and specificity for the tetramer over the dimer and trimer.

The three core residues were inserted into an 11-residue sequence template that was used in the earlier designs of right-handed coiled coils containing nonbiological amino acids (Harbury et al. 1998; Plecs et al. 2004). As in the previous RH coiled-coiled designs, three approximate repeats of the 11-mer were linked to create the 33-residue RH4B monomer. To obtain experimental phases for the crystallographic data, the metal binding site pioneered in RH3 (Plecs et al. 2004), consisting of γ-carboxyglutamate residues at positions 19 and 23, was inserted into the RH4B sequence.

Peptide synthesis and purification

The RH4B peptides were synthesized using Fmoc, solid-phase, chemical synthesis at the University of Utah Health Sciences Center DNA/Peptide Core Facility. Peptides were purified using reversed-phase HPLC on a C18 column using an acetonitrile (AcN) gradient with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The peptides eluted from the column at ∼40% AcN. Peptide masses were confirmed using electrospray mass spectrometry on an Esquire LC. The peptides were concentrated using lyophilization.

Circular dichroism and equilibrium ultracentrifugation

Thermal melts were monitored by CD at 224 nm, in 50 mM NaAc (pH 5.2), 50 mM AmSO4, 20 mM EDTA, 1 M GuHCl, with a peptide concentration of 20 μM. In the absence of GuHCl, the Tm was over 80°C, and the upper baseline was not defined (data not shown). In the presence of 1 M GuHCl, the Tm was 44°C (Fig. 2A).

Equilibrium sedimentation was performed in a Beckman X-LA ultracentrifuge using 300 μM of RH4B in 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.2, 50 mM AmSO4, and 20 mM EDTA. The absorbance was measured at 274 nm, 25°C, 35,000 rpm, and averaged over 10 repetitions. The absorbance measurements were buffer corrected. The solvent density ρs was calculated to be 1.0064 g/cm3 by averaging the buffer constituents (Harding 1994). The specific volume was estimated by using a weighted average of the amino acids (Harding 1994). The γ-carboxyglutamates were approximated to have the same density as glutamate (though with a correspondingly larger mass). The resulting protein density for RH4B was found to be ρp = 1.309 g/cm3.

Crystallization and structure determination

The purified RH4B peptide was crystallized by vapor diffusion when a 15 mg/mL solution of RH4B was mixed in equal volume with 10 mM YbCl2, 10% PEG-4000, 150 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.2, and 100 mM ammonium sulfate. The crystal was immersed in Paratone-N oil, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Despite the fact that the mother liquor contained only 10% PEG 4000, no ice formed upon freezing as long as the mother liquor was not present outside the surface of the crystal.

Diffraction data were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) Beamline 9–2. Data were collected in a 100° wedge, since the crystal was observed to have tetrahedral symmetry. The inverse beam method was used to collect anomalous difference data. Two passes were made for each wavelength, a shorter one for low-resolution data and a longer one for high-resolution data. Multiwavelength anomalous diffraction data were collected at the inflection F′ = 1.3864 Å (8942.9 eV) and the peak F″ = 1.3858 Å (8946.8 eV) of the measured Yb absorption edge, as well as two reference wavelengths. After collecting the data at the first reference wavelength [Fhi = 1.2398 Å (10,000.0 eV)], the detector was moved closer to the crystal to increase the high-resolution limit at the second wavelength (Fhr = 1.0 Å).

The data were analyzed using ELVES (Holton and Alber 2004), which indexed the X-ray frames using MOSFLM (Leslie 1992; Powell 1999) and scaled and merged using SCALA (Evans 1993). The position of the Yb2+ site was found using SOLVE (Terwilliger and Berendzen 1999) to determine initial phases to 1.3 Å resolution. The metal site was refined using SHARP (Bricogne et al. 2003) and the resulting phases were extended to 1.1 Å resolution using RESOLVE (Terwilliger 2000). The mean figure of merit was calculated to be 0.95 by both SHARP and RESOLVE. An initial model was built using wARP (Morris et al. 2003). Utilizing visual feedback from O (Jones et al. 1991), the initial model was completed by hand. The model was refined through many iterations of REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al. 1997, 1999) and ARP (Lamzin and Wilson 1993). Anisotropic B factors and multiple conformers were added during refinement. The statistics of the final model are shown in Table 1.

Coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 2O6N).

Structure analysis and comparisons

Alignments between structures were calculated using the CCP4 program LSQKAB on the corresponding Cα atoms (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 1994). The cavity contours in Figure 3D were generated using the “show mesh” command of PyMOL (DeLano 2002) with the default van der Waals radii around all nonsolvent atoms in the RH4B tetramer. Superhelical parameters were calculated by performing a least-squares fit between the Cα atoms of 7-mers in the coiled coil against the coordinates predicted by an ideal superhelix (Harbury et al. 1998).

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Pehr Harbury and Peter Kim for initiating the RH design project. We thank Robert Schackmann for peptide synthesis, the staff of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory for help with X-ray data collection, and Catherine Dea for assistance preparing the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH Grant R01 GM48958.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Tom Alber, Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, 374B Stanley Hall, Number 3220, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3220. USA; e-mail: tom@ucxray.berkeley.edu; fax: (510) 666-2768.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062702907.

References

- Bolon D.N. and Mayo, S.L. 2001. Enzyme-like proteins by computational design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 14274–14279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricogne G., Vonrhein, C., Flensburg, C., Schiltz, M., and Paciorek, W. 2003. Generation, representation and flow of phase information in structure determination: Recent developments in and around SHARP 2.0. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59: 2023–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks B.R., Bruccoleri, R.E., Olafson, B.D., States, D.J., Swaminathan, S., and Karplus, M. 1983. CHARMM: A program for macromolecular energy minimization and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 4: 187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Brunger A.T. 1992. X-PLOR: A system for X-ray crystallography and NMR, 3.1 ed. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

- Chevalier B.S., Kortemme, T., Chadsey, M.S., Baker, D., Monnat, R.J., and Stoddard, B.L. 2002. Design, activity, and structure of a highly specific artificial endonuclease. Mol. Cell 10: 895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 1994. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol Crystallogr. 50: 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F.H. 1952. Is alpha-keratin a coiled coil? Nature 170: 882–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F.H.C. 1953a. The Fourier transform of a coiled-coil. Acta Crystallogr. 6: 685–689. [Google Scholar]

- Crick F.H.C. 1953b. The packing of α-helices: Simple coiled coils. Acta Crystallogr. 6: 689–697. [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W.L. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA.

- Dure L. 1993. A repeating 11-mer amino acid motif and plant desiccation. Plant J. 3: 363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer M.A., Looger, L.L., and Hellinga, H.W. 2004. Computational design of a biologically active enzyme. Science 304: 1967–1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans P.R. 1993. Data reduction. In Proceedings of CCP4 study weekend on data collection and processing (eds. L. Sawyer, N. Isaacs, and S. Bailey), pp. 114–122. Darebury Laboratory, Warrington, UK.

- Harbury P.B., Zhang, T., Kim, P.S., and Alber, T. 1993. A switch between two-, three-, and four-stranded coiled coils in GCN4 leucine zipper mutants. Science 262: 1401–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbury P.B., Kim, P.S., and Alber, T. 1994. Crystal structure of an isoleucine-zipper trimer. Nature 371: 80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbury P.B., Tidor, B., and Kim, P.S. 1995. Repacking protein cores with backbone freedom: Structure prediction for coiled coils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92: 8408–8412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbury P.B., Plecs, J.J., Tidor, B., Alber, T., and Kim, P.S. 1998. High-resolution protein design with backbone freedom. Science 282: 1462–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding S.E. 1994. Determination of absolute molecular weights using sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation. Methods Mol. Biol. 22: 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holton J. and Alber, T. 2004. Automated protein crystal structure determination using ELVES. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 1537–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou, J.Y., Cowan, S.W., and Kjeldgaard, M. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A 47: 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman B., Dantas, G., Ireton, G.C., Varani, G., Stoddard, B.L., and Baker, D. 2003. Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy. Science 302: 1364–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamzin V.S. and Wilson, K.S. 1993. Automated refinement of protein models. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 49: 129–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie A.G.W. 1992. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Daresbury Laboratory, Warrington, UK.

- Looger L.L., Dwyer, M.A., Smith, J.J., and Hellinga, H.W. 2003. Computational design of receptor and sensor proteins with novel functions. Nature 423: 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R.J., Perrakis, A., and Lamzin, V.S. 2003. ARP/wARP and automatic interpretation of protein electron density maps. Methods Enzymol. 374: 229–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G.N., Vagin, A.A., and Dodson, E.J. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53: 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G.N., Vagin, A.A., Lebedev, A., Wilson, K.S., and Dodson, E.J. 1999. Efficient anisotropic refinement of macromolecular structures using FFT. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55: 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plecs J.J., Harbury, P.B., Kim, P.S., and Alber, T. 2004. Structural test of the parameterized-backbone method for protein design. J. Mol. Biol. 342: 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell H.R. 1999. The Rossmann Fourier autoindexing algorithm in MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55: 1690–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetefeld J., Jenny, M., Schulthess, T., Landwehr, R., Engel, J., and Kammerer, R.A. 2000. Crystal structure of a naturally occurring parallel right-handed coiled-coil tetramer. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 772–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T.C. 2000. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56: 965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T.C. and Berendzen, J. 1999. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55: 849–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B.Y., Zhou, N.E., Kay, C.M., and Hodges, R.S. 1993. Packing and hydrophobicity effects on protein folding and stability: Effects of β-branched amino acids, valine and isoleucine, on the formation and stability of two-stranded α-helical coiled coils/leucine zippers. Protein Sci. 2: 383–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]