Abstract

BACKGROUND

Multiple complicated transitions or “bounce-backs” soon after hospital discharge may herald health system failure. Acute stroke patients often undergo transitions after hospital discharge, but little is known about complicated transitions in these patients.

OBJECTIVE

To identify predictors of complicated transitions within thirty days after hospital discharge for acute stroke.

DESIGN

Retrospective analysis of administrative data

SETTING

422 hospitals, southern and eastern United States

PARTICIPANTS

39,384 Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years discharged with acute ischemic stroke 1998–2000.

MEASUREMENTS

Complicated transition defined as movement from less to more intense care setting after hospital discharge, with hospital being most intense and home without home-health care being least intense.

RESULTS

20% of patients experienced at least one complicated transition; 16% of those experienced more than one complicated transition. After adjustment using logistic regression, factors predicting any complicated transition included older age, African-American race, Medicaid enrollment, prior hospitalization, gastrostomy tube, chronic disease, length of stay and discharge site. When compared to patients with only one complicated transition, patients with multiple complicated transitions were more likely to be African-American [Odds Ratio=1.38, 95% Confidence Interval=1.13–1.68], be male [1.21, 1.04–1.40], have prior diagnosis of fluid and electrolyte disorder (e.g. dehydration) [1.23, 1.07–1.43], have a prior hospitalization [1.18, 1.01–1.36] and be initially discharged to skilled-nursing facility/long-term care [1.22, 1.04–1.44]. They were less likely to be initially discharged to a rehabilitation center [0.71, 0.57–0.89].

CONCLUSIONS

Significant numbers of stroke patients experience complicated transitions soon after hospital discharge. Sociodemographic factors and initial discharge site distinguish patients with multiple complicated transitions. These factors may enable prospective identification and targeting of stroke patients at risk for “bouncing-back”.

Keywords: Transition, Stroke, Hospital Discharge, Risk Factors

INTRODUCTION

In the current system of specialized health care, patients with complex chronic health conditions like acute stroke often require care across multiple settings with numerous care transitions.1 Some of these patients will undergo “complicated transitions” (i.e. “bounce-backs”), movement from a less intense to a more intense care setting (e.g. home to the hospital).2 Patients who undergo multiple complicated transitions within a short period of time signify potential health system failures and represent promising targets for improved quality of care.2, 3 The 2001 Institute of Medicine report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the Twenty-first Century, calls for improved transition quality via greater health care delivery system integration.4 Better understanding of complicated transition prevalence, pattern and predictors is needed prior to fully realizing the Institute of Medicine’s charge.

Acute stroke provides an excellent model for the study of complicated transitions. Stroke is a common complex problem, accounting for a large degree of disability, mortality and resource utilization in the geriatric population. Stroke affects over 500,000 older persons each year in the United States and costs at least $53 billion annually.5 Acute stroke patients undergo frequent care transitions during their usual course of care6, 7 and are at significant risk for subsequent medical complications, like pneumonia. Stroke constitutes the largest category of patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation facilities8 and represents a large proportion of patients in sub-acute rehabilitation facilities.9 Given their large number, frequent transitions and significant risk for medical complications, patients with acute stroke are at high risk for complicated transitions and provide an excellent indicator of the health system’s capacity to support a complex, frequently transitioning population. Yet, to our knowledge, no investigation of complicated transitions in stroke patients has been published. By investigating the patterns and predictors of complicated transitions in acute stroke patients, prospective identification of patients at-risk for multiple complicated transitions will be possible, allowing for the development of targeted quality improvement strategies for vulnerable populations.

The objective of this analysis is to identify the characteristics and predictors of patients with complicated transitions in the first thirty days after hospitalization for acute stroke. First, we will describe the type and prevalence of complicated transitions during the first thirty days. Next, we will identify sociodemographic and clinical factors predictive of undergoing both any complicated transition as well as multiple complicated transitions. Finally, we will examine the predictors of complicated transition destination (emergency room or hospital) in acute stroke patients with multiple complicated transitions.

METHODS

Population and Sampling

We identified Medicare beneficiaries 65 years of age and older discharged alive with acute ischemic stroke during 1998–2000 in 11 metropolitan regions of the country.10 Patients were included in the sample if they had an International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) diagnosis code of 434 or 436 in the first position on the discharge diagnosis list from an acute care hospitalization, which has been found to accurately identify acute ischemic stroke in 89–90% of cases.11 If a patient had more than one acute ischemic stroke discharge over the study period, one discharge was randomly selected. This approach did not require analyses accounting for repeated observations on the same patient.

We obtained health maintenance organization (HMO) data from a large national managed care organization and fee-for-service (FFS) data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Our sample included 4,816 HMO patients with acute ischemic stroke (from 422 hospitals) enrolled in 11 Medicare Plus Choice plans serving 93 metropolitan counties primarily in the eastern half of the United States. Comparable data were obtained for 34,568 FFS patients discharged with acute ischemic stroke from the same hospitals. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin approved this study.

Data Extraction

We obtained enrollment data and final institutional and physician/supplier claims for all study patients from one year prior to their index hospital admission date to one year after their index hospital admission date. Both HMO and FFS patients had claims submitted using identical forms.12, 13 We also obtained all claims for HMO patients submitted to the HMO from out-of-network facilities. For all patients, we obtained the Medicare denominator file to determine age, gender, race, zip code, Medicaid enrollment, and date of death. This file was used to exclude beneficiaries who had end-stage renal disease, were missing Medicare Part A or Part B coverage, or received railroad retirement benefits.

Variables

The main dependent variable was complicated transition. “Complicated transition” was defined as movement from a less intense to a more intense care setting, with hospital being the most intense on the care spectrum, then emergency room (ER), followed by skilled nursing facility/rehabilitation center/long-term care, then home with home health care, and, finally, home without home health care as the least intense.2 Destination of the complicated transition was considered to be the most intense care level attained within an episode of care.

We obtained initial discharge destination from facility and non-facility claims occurring within one day of index hospitalization discharge date. Using facility claims, we identified patients admitted to rehabilitation facilities (freestanding or inpatient unit) and skilled nursing facilities. We used the place of service code on subsequent physician claims to identify patients discharged to long-term care facilities. Remaining patients were categorized as either home with home care claims within thirty days after the stroke discharge date or home with no home care claims. Patients with ER visits or rehospitalization within thirty days of the index hospitalization discharge date were identified using subsequent facility claims. For each patient, all identified sites of care within thirty days of the index hospitalization discharge date were sequentially ordered by date of service. This ordering enabled examination for movement from a less intense to a more intense care setting (a complicated transition). Patients were grouped into categories of no complicated transition, one complicated transition and survived thirty days, one complicated transition and died within thirty days, and ≥2 (multiple) complicated transitions for analysis. Additional stratifications were not performed as too few patients were present in the ≥3 complicated transition category (n=179) to allow for analysis.

We included individual and neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics as potential explanatory variables. Individual characteristics included age, gender, race, HMO membership and an indicator identifying beneficiaries with low to modest income who were fully enrolled in Medicaid or receive some help with Medicare cost-sharing through Medicaid. Zip+4 data were used to link patient data to the corresponding Census 2000 block group and obtain neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics including percent over 24 years of age with college degree and percent below poverty line.14

Individual comorbidities and measures of stroke severity were also included as potential explanatory variables. We identified 30 comorbid conditions by incorporating information from the index hospitalization, all hospitalizations during the prior year, and all physician claims during the prior year using methods proposed by Elixhauser, et al.,15 and Klabunde, et al.16 Of these 30 conditions, we included the 12 comorbidities present in over 5% of our sample as explanatory variables. We also coded the following: hospitalization during the year prior to the index hospitalization, dementia,17 stroke during the year prior to the index hospitalization,18 and concurrent cardiac events (acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris, coronary artery bypass graft, and cardiac catheterization). Two validated indicator variables, mechanical ventilation (CPT 94656, 94657; ICD-9 96.7x)19 and placement or revision of a gastrostomy tube (CPT 43750, 43760, 43761, 43832, 43246; ICD-9 43.11),20 were used to represent disease severity during index hospitalization. Length of index hospital stay as measured in days was also included as an explanatory variable.

Analysis

Multivariable logistic regression was used to analyze the relationship between the explanatory variables and complicated transitions (i.e., patients with at least one complicated transition as compared to surviving patients with no complicated transitions thirty days after index hospitalization). As one complicated transition in a vulnerable patient might randomly occur after hospitalization due to routine care complications, we next chose to compare patients with ≥2 (multiple) complicated transitions to those who had one complicated transition and survived thirty days. This comparison group is more likely to isolate factors identifying vulnerable patients at risk for multiple complicated transitions. Finally, to better understand the predictors of complicated transition destination, logistic regression was used to analyze the relationship between characteristics of patients with ≥2 complicated transitions to the ER and of patients with ≥2 complicated transitions to the hospital as compared to surviving patients with one complicated transition to either hospital or ER thirty days after index hospitalization discharge.

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 8.021 and Stata version 7.0.22 Results of logistic regression analyses are reported in odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). All confidence intervals and significance tests were significant at P < 0.05 and were calculated using robust estimates of the variance that allowed for clustering of patients within hospitals. Models included age (65–69 years, 70–74 years, 75–79 years, 80–85 years, and 85+ years), gender, race (Caucasian, African American, and Other), Medicaid, HMO membership, % of the census block group aged 25+ with college degrees, % of persons in the census block group below the poverty line, initial index hospitalization discharge destination (skilled nursing facility/long-term care, rehabilitation center, home with home health care and home without home health care), length of index hospital stay, prior hospitalization, prior stroke, cardiac arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, uncomplicated diabetes mellitus, complicated diabetes mellitus, hypertension, fluid and electrolyte disorders, valvular disease, peripheral vascular disorders, hypothyroidism, solid tumor without metastasis, deficiency anemias, depression, dementia, concurrent cardiac event, mechanical ventilation and presence of gastrostomy tube.

RESULTS

Descriptive Characteristics

Table 1 provides key characteristics of the acute stroke population studied. The average age was 79.64 years, while 39% of the population was male and 13% was African American. 16% received Medicaid and 11% were enrolled in an HMO. 38% had experienced a hospitalization in the year prior to the index hospitalization. Average length of stay for index hospitalization was 5.67 days. Initial index hospital discharge destination was skilled nursing facility for 34%, home without home health care for 31% and rehabilitation center for 20%. The remainder of patients (15%) were discharged home with home health care services. The most common comorbidities included hypertension (74%), cardiac arrhythmias (38%), complicated and uncomplicated diabetes mellitus (30%), congestive heart failure (23%), dementia (23%) and fluid and electrolyte disorders (23%). 7% of patients had placement of a gastrostomy tube and 2% required mechanical ventilation during the index hospitalization.

Table 1.

Key Characteristics of Acute Stroke Patient Population Studied (N=39,384)

| Characteristic | Patient Population* |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |

| Average Age in years (+/− SD) | 79.6 (7.5) |

| 65–69 years | 9.8 |

| 70–74 years | 17.6 |

| 75–79 years | 22.9 |

| 80–84 years | 22.2 |

| >85 years | 27.5 |

| Male | 39 |

| Caucasian | 83 |

| African-American | 13 |

| Other minority | 4 |

| Medicaid | 16 |

| HMO† member | 11 |

| % in block group Below the Poverty Line (+/− SD) | 11 (11) |

| % adults ≥25 years in block group with College Degree (+/− SD) | 24 (17) |

| Index Hospitalization | |

| Length of Stay in days (+/− SD) | 5.7 (4.5) |

| Discharged from Index Hospital Stay to: | |

| Home | 31 |

| Home with Home Health | 15 |

| Rehabilitation Center | 20 |

| Skilled Nursing Facility or Long-Term Care | 34 |

| Prior Medical History | |

| Prior Hospitalization | 38 |

| Prior stroke | 7 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 38 |

| Congestive heart failure | 23 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 19 |

| diabetes mellitus, uncomplicated | 22 |

| diabetes mellitus, complicated | 8 |

| Hypertension | 74 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 23 |

| Valvular disease | 16 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 15 |

| Hypothyroidism | 12 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 13 |

| Deficiency anemias | 15 |

| Depression | 9 |

| Dementia | 23 |

| Concurrent cardiac event | 2 |

| Disease severity | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2 |

| Gastrostomy tube | 7 |

Values represent percents unless specified otherwise.

Health maintenance organization

Complicated Transition Prevalence

A substantial number of stroke patients experienced at least one complicated transition during the first thirty days after acute stroke hospitalization. Twenty percent (N=8,052) experienced at least one complicated transition during the first thirty days after index hospitalization, while 16% (N=1,259) of those patients had multiple complicated transitions (≥2) during the same timeframe. Specifically, 6,793 patients experienced one complicated transition within the first thirty days, 1,080 patients experienced two, 156 patients experienced three, and 23 patients experienced four or more. The most common complicated transition destination for patients experiencing four or more complicated transitions was the ER.

Complicated Transition Patterns

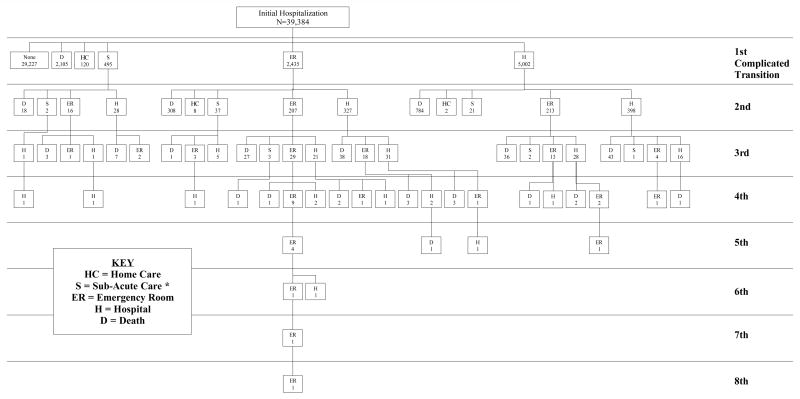

Patterns of complicated transition destination during the first thirty days after acute stroke showed marked complexity (Figure 1). Prior to each complicated transition, by definition, patients are in a less intense level of care, usually a sub-acute care setting or home. These movements to a less intense care setting between complicated transitions were not represented in Figure 1 due to practical space limitations and for visual clarity. Deaths were not counted as complicated transitions for analysis, but were represented in the figure to further clarify patients’ courses. Approximately 16% (n=1110) of patients with one complicated transition died within thirty days as compared to 14% (n=170) of patients with multiple complicated transitions. 7% (n=2105) of patients with no complicated transitions died within the thirty day timeframe.

Figure 1. Complicated Transition Patterns During the First 30 Days After Hospitalization for Acute Stroke.

In each box the letter denotes the complicated transition destination and the number denotes the number of patients undergoing the complicated transition. Less intense sites of care between complicated transition destinations are not represented due to space limitations. Key: HC = Home Care; S = Sub-Acute Care (Skilled Nursing Facility/Rehabilitation Center/Long-Term Care); ER = Emergency Room; H = Hospital; D = Death. Deaths were not counted as complicated transitions for analysis, but were represented in the figure to clarify patients’ courses.

* Sub-Acute Care = Skilled Nursing Facility /Rehabilitation Center /Long-Term Care

Predictors of Any Complicated Transition

Stroke patients with at least one complicated transition could be differentiated from those with no complicated transitions by a number of sociodemographic, index hospitalization and comorbidity measures. When compared to surviving acute stroke patients with no complicated transitions, patients with at least one complicated transition were more likely to be older, African-American, receive Medicaid, to have had prior hospitalizations and a longer index hospital length of stay, to be initially discharged to a skilled nursing facility/long-term care and to have congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, complicated or uncomplicated diabetes mellitus, fluid and electrolyte disorders, deficiency anemias, depression, dementia, concurrent cardiac event and a gastrostomy tube (Table 2). Having a gastrostomy tube and being initially discharged to a skilled nursing facility/long-term care were the two factors most strongly predictive of experiencing a complicated transition. In contrast, a higher percentage of college graduates in a stroke patient’s Census 2000 block group was associated with a lower risk of complicated transition.

Table 2.

Predictive Factors for Complicated Transitions in Acute Stroke Patients First 30 Days After Index Hospitalization (N=39,384)†

| Characteristic | At Least One Complicated Transition

|

|

|---|---|---|

| OR* | 95 % CI | |

| Sociodemographic | ||

| 70–74 years | 1.03 | (0.92, 1.16) |

| 75–79 years | 1.17 | (1.06, 1.29) ¶ |

| 80–84 years | 1.21 | (1.08, 1.36) § |

| >85 years | 1.30 | (1.16, 1.44) § |

| Male | 1.05 | (0.99, 1.11) |

| African-American | 1.17 | (1.06, 1.29) § |

| Other Race | 1.02 | (0.88, 1.18) |

| Medicaid | 1.18 | (1.09, 1.28) § |

| HMO member | 1.04 | (0.95, 1.13) |

| % in block group Below the Poverty Line | 0.94 | (0.71, 1.24) |

| % adults ≥25 years in block group with College Degree | 0.73 | (0.61, 0.88) § |

| Index Hospitalization | ||

| Length of Stay | 1.04 | (1.03, 1.05) § |

| Discharged from Index Hospital Stay to: | ||

| Home with Home Health‡ | 1.08 | (0.99, 1.17) |

| Rehabilitation Center‡ | 0.96 | (0.88, 1.05) |

| Skilled Nursing Facility or Long-Term Care‡ | 1.36 | (1.25, 1.48) § |

| Prior Medical History | ||

| Prior Hospitalization | 1.23 | (1.16, 1.31) § |

| Prior stroke | 1.07 | (0.97, 1.17) |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 1.05 | (0.99, 1.12) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.25 | (1.17, 1.34) § |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.19 | (1.11, 1.28) § |

| diabetes mellitus, uncomplicated | 1.12 | (1.04, 1.2) ¶ |

| diabetes mellitus, complicated | 1.15 | (1.04, 1.27) ¶ |

| Hypertension | 0.96 | (0.89, 1.02) |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 1.17 | (1.1, 1.24) § |

| Valvular disease | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.11) |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 1.08 | (1, 1.17) |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.99 | (0.92, 1.08) |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 0.99 | (0.92, 1.07) |

| Deficiency anemias | 1.10 | (1.02, 1.19) ¶ |

| Depression | 1.13 | (1.03, 1.25) ¶ |

| Dementia | 1.15 | (1.07, 1.23) § |

| Concurrent cardiac event | 1.31 | (1.08, 1.6) ¶ |

| Disease severity | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | 0.81 | (0.64, 1.02) |

| Gastrostomy tube | 1.52 | (1.37, 1.68) § |

As compared to acute stroke patient population with no complicated transitions 30 days after index hospitalization.

Deaths were not counted as complicated transitions for analysis.

Baseline comparison for discharge site is home without home health care.

p-value ≤ 0.001

p-value ≤ 0.05

Predictors of Multiple Complicated Transitions

To better identify predictive factors for multiple complicated transitions, acute stroke patients with multiple complicated transitions were compared to surviving patients with only one complicated transition. Those with multiple complicated transitions were more likely than their counterparts with only one complicated transition to be African-American (p-value = 0.002), have a diagnosis of fluid and electrolyte disorder (e.g. dehydration) (p-value = 0.005), be male, have had a prior hospitalization, and to have been initially discharged to a skilled nursing facility/long-term care (Table 3). Patients initially discharged to a rehabilitation center were less likely to have multiple complicated transitions (p-value = 0.003). Being African-American was the most strongly predictive factor. Except for a diagnosis of fluid and electrolyte disorder, no other comorbidity variables distinguished patients with multiple complicated transitions.

Table 3.

Predictive Factors for Multiple Complicated Transitions in Acute Stroke Patients First 30 Days After Index Hospitalization (N=7,097)†

| Characteristic | Multiple (≥ 2) Complicated Transitions* |

|

|---|---|---|

| OR‡ | 95 % CI | |

| Patient Characteristics | ||

| Male | 1.21 | (1.04, 1.4) ¶ |

| African-American | 1.38 | (1.13, 1.68) § |

| Prior Hospitalization | 1.18 | (1.01, 1.36) ¶ |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 1.23 | (1.07, 1.43) § |

| Index Hospitalization Characteristics | ||

| Initially Discharged to Rehabilitation Center | 0.71 | (0.57, 0.89) § |

| Initially Discharged to Skilled Nursing Facility or Long-Term Care | 1.22 | (1.04, 1.44) ¶ |

As compared to surviving patients with one complicated transition during the first 30 days after acute stroke hospitalization

Deaths were not counted as complicated transitions for analysis.

Adjusted for age, Medicaid status, HMO membership, socio-economic status, education, region, length of index hospital stay, prior stroke, cardiac arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, valvular disease, peripheral vascular disease, thyroid disease, malignancy, anemia, depression, dementia, concurrent cardiac event, mechanical ventilation and presence of gastrostomy tube. Baseline comparison for discharge site is home without home health care.

p-value ≤ 0.01

p-value ≤ 0.05

Predictors of Complicated Transition Destination

Of the study population with multiple complicated transitions, stroke patients with multiple complicated transitions only to the ER (N = 186) could be differentiated from those patients with multiple complicated transitions only to the hospital (N = 395) by a number of key factors. When compared to surviving acute stroke patients with one complicated transition to either the hospital or ER, acute stroke patients with multiple complicated transitions only to the ER were more likely to be African-American and to have valvular disease (Table 4). They were less likely to have a deficiency anemia or to have been initially discharged to a rehabilitation center. Patients with multiple complicated transitions only to the hospital were more apt to be male, have a gastrostomy tube and to have a diagnosis of hypertension and fluid or electrolyte disorder than their surviving counterparts with only one complicated transition to either the hospital or ER.

Table 4.

Predictors of Complicated Transition Destination (ER or Hospital) in Patients with Multiple Complicated Transitions in the First 30 Days After Acute Stroke Hospitalization (N=5,947)†

| Characteristic | Multiple (≥2) Complicated Transitions to Only ER* |

Multiple (≥2) Complicated Transitions to Only Hospital* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR‡ | 95 % CI | OR‡ | 95 % CI | |

| Patient Characteristics | ||||

| Male | 0.80 | (0.56, 1.15) | 1.45 | (1.17, 1.79) § |

| African-American | 1.96 | (1.23, 3.12) § | 1.17 | (0.85, 1.61) |

| Hypertension | 0.71 | (0.5, 1.02) | 1.30 | (1, 1.68) ¶ |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 1.23 | (0.86, 1.77) | 1.32 | (1.04, 1.67) ¶ |

| Valvular disease | 1.49 | (1.06, 2.1) ¶ | 1.09 | (0.8, 1.47) |

| Deficiency anemias | 0.64 | (0.42, 0.97) ¶ | 1.29 | (0.97, 1.72) |

| Gastrostomy tube | 0.58 | (0.33, 1.02) | 1.51 | (1.05, 2.19) ¶ |

| Index Hospitalization Characteristics | ||||

| Initially Discharged to Rehabilitation Center | 0.39 | (0.21, 0.73) § | 0.79 | (0.54, 1.16) |

As compared to surviving patients with one complicated transition to either hospital or ER 30 days after acute stroke hospitalization

Deaths were not counted as complicated transitions for analysis.

Adjusted for age, Medicaid status, HMO membership, socio-economic status, education, region, index hospitalization length of stay, prior stroke, cardiac arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, thyroid disease, malignancy, depression, dementia, concurrent cardiac event and mechanical ventilation. Baseline comparison for discharge site is home without home health care.

p-value ≤ 0.01

p-value ≤ 0.05

DISCUSSION

A significant percentage of stroke patients experienced complicated transitions within thirty days of their acute stroke hospitalization. Stroke patients with any complicated transitions were more likely to be older, African-American, Medicaid enrollees, have longer index hospital lengths of stay, be initially discharged to skilled nursing facilities/long-term care and to have more chronic diseases than their counterparts with no complicated transitions. However, when patients with multiple complicated transitions were compared to those with one complicated transition, those with multiple complicated transitions were notably distinguished by sociodemographic factors and initial discharge site, with comorbidity factors playing a significantly lesser role.

Measurement of complicated transitions within a population likely provides a better overview of patient trajectory than does rehospitalization or ER visit data alone. The 2001 Institute of Medicine’s charge of improved transition quality via greater health system integration necessitates an integrated measure of patient progression through the health system.4 Coleman’s concept of complicated transition provides just such a measure.2 By integrating all of a patient’s “bounce-backs” (i.e., transitions to settings of increased intensity) through a health system in one measure, the concept of complicated transition allows for identification of patient populations utilizing combinations of higher intensity health services. It identifies at risk patients that measures of ER visits alone or rehospitalization rates alone may miss. As a result, a focus on complicated transitions may improve health system evaluation, especially in the area of chronic disease and disability care. This complicated transitions measure could be utilized by administrators and clinicians to prospectively identify and target a specific population of acute stroke patients for whom additional preventive services, such as home health, social work or transitional care interventions,23 may result in improved patient outcome and decreased overall cost. Additionally, the overall number or change in number of complicated transitions over time may have potential value as a marker for intervention efficacy, thus enabling program evaluation and comparison at both the clinical and administrative levels.

Given the number and complexity of transitions acute stroke patients experience soon after hospitalization, we believe the acute stroke population provides an ideal model for study of patient transitions, complicated transitions and for implementation of interventions designed to improve transitional care quality. Our findings agree with those of previous studies documenting the high risk of readmission soon after acute stroke hospitalization and the frequent transitions acute stroke patients experience during their usual course of care.6, 24 Additionally, our data supports that complicated transitions soon after discharge are very common in this population. Prior investigations have demonstrated that improved patient transitions using protocols or procedures targeted specifically at the health system-patient interface can be beneficial in decreasing readmission rates of acute stroke patients.7 If even a small proportion of the many complicated transitions stroke patients experience could be prevented via prospective identification of and intervention with patients at risk, the cost savings would likely be substantial.5 Certainly, further study in the area of stroke transitional care and complicated transition prevention is warranted.

We demonstrated that stroke patients with multiple complicated transitions could be differentiated from their counterparts with only one complicated transition by sociodemographic factors and initial discharge site, with comorbidity factors playing a significantly lesser role. This result, along with the complete lack of significance of stroke severity variables within this model and the lack of a 30 day mortality difference between complicated transition patient groupings, strengthens the position that health system failures are the main contributor to multiple complicated transitions in this vulnerable population. We could divide factors predictive of multiple complicated transitions into two groups: those predictive of recurrent ER utilization (i.e. African-American race) and those predictive of rehospitalization (i.e. fluid and electrolyte disorders). Overall, these findings provide potential for prospective identification of specific populations in need of preventive intervention.

Our finding that African-American race was the strongest predictive factor for multiple complicated transitions agrees with that of previous studies examining factors surrounding stroke readmission.25, 26 These findings echo known data regarding African-American rehospitalization and emergency room use rates in other disease models including diabetes mellitus and asthma.27–29 In contrast, a previous Veterans Administration study of congestive heart failure found no relationship between ethnicity and readmission rate, and only minimal differences in emergency service utilization by race.30 This distinction may be due to fundamental differences between disease models or to the availability of more equitable health care access in the Veterans Administration system. As access to primary care is an important factor in decreasing mortality and preventable hospitalizations in African-Americans, further investigation into the role primary care access has in African-American patients with multiple complicated transitions is warranted.31–33 Additionally, if African-Americans refuse or are not referred to post-stroke rehabilitation at rates higher than whites,34 similar to the phenomenon seen in cardiac rehabilitation,35 they would lose the protective effect that initial discharge to a rehabilitation center has on the risk of undergoing multiple complicated transitions. Further investigation into what effect patient preference for post-stroke rehabilitation has on the risk of experiencing multiple complicated transitions soon after index hospital discharge is needed.

Besides African American race, several other factors predicted multiple complicated transitions soon after acute stroke hospitalization. Diagnosis of any fluid and electrolyte disorder (e.g. dehydration) either during the index hospitalization or in the year prior to the index hospitalization was a strong predictor of both rehospitalization and multiple complicated transitions and may represent a surrogate marker for presence of decreased social support,36 a factor which may increase the likelihood of a complicated transition. The increased rehospitalization risk in post-stroke males noted in this study echoes that of previous studies in the post-stroke population.26 Our findings of increased risk of multiple complicated transitions in patients initially discharged to skilled nursing facilities/long-term care centers is consistent with previously known patterns of care utilization,37 and may reflect greater likelihood of inappropriate transfer,38 incomplete adjustment for increased illness severity, or greater chance for poor quality care transitions in this population. The decreased risk of multiple complicated transitions for patients initially discharged to rehabilitation facilities may reflect improved access to primary care within the rehabilitation center, incomplete adjustment for an overall reduced illness severity in this population, a protective effect of rehabilitation services,39 or the physical location of many of these facilities within hospitals, allowing for initiation of multi-specialty, increased intensity care without leaving the rehabilitation center confines. Certainly, this protective effect of rehabilitation facilities for complicated transitions is notable, worthy of further investigation, and argues for encouraging referral of acute stroke patients to rehabilitation facilities immediately after their acute hospitalization.

This study has limitations. To address the potential problems associated with administrative diagnosis and procedure codes, we used codes previously shown to accurately identify ischemic stroke.11 However, in any study utilizing administrative data some misclassification may occur.40 Since patients with stroke documentation in the non-primary diagnostic position have greater comorbidity burden and 30-day mortality, by using the primary discharge diagnosis code we may have biased the sample toward more benign outcomes.41 Our measures of stroke severity were limited but valid.19, 20 However, in the absence of more definitive severity measures, such as post-stroke functional status, it is impossible to comment on the appropriateness of patient discharge from the index hospitalization. Additionally, administrative data provides no direct measures of patient preference. Stroke patients’ preferences, especially regarding code status, likely influence their chance of experiencing multiple complicated transitions.42 Thus, lack of information regarding patient preference is a major limitation of this particular research approach. Additional studies to explore the role of appropriate patient discharge and patient preference in complicated transitions are needed. Finally, it is unclear whether these findings would apply to non-stroke populations. Further study of complicated transitions in patient populations other than acute stroke is needed.

In conclusion, our research has a number of broad implications. First, the concept of complicated transition provides a much needed, integrated measure of a patient’s progress through the health system. Application of the complicated transition measure to other patient populations may prove valuable in better understanding how adequately the health system manages acute and chronic disease and in better identifying patients at increased risk of poor health outcome. Secondly, stroke patients provide an excellent model for the study of transitional care, especially given the frequent occurrence of complicated transitions in this population. Additional interventions to prevent complicated transitions and analyses to understand the cost of complicated transitions in stroke patients are needed. Finally, acute stroke patients with multiple complicated transitions can be differentiated from their counterparts with one complicated transition primarily by sociodemographic variables and initial discharge site. This argues for possible health system failure and provides clinicians and administrators the ability to prospectively identify a vulnerable population in need of preventive intervention. Further investigation into the effect of health system accessibility and patient preference on the multiple complicated transitions measure will improve our understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sandy Wright and Bernie Tennis for their assistance in variable creation, and Sonja Raaum and Julia Yahnke for their assistance in manuscript editing.

This study was supported by a grant (R01-AG19747) from the National Institute of Aging (Principal Investigator: Maureen Smith, MD PhD).

Footnotes

This research has been previously presented at the National Meetings of the Gerontological Society of America, 2005 and Academy Health, 2005.

Conflicts of Interest

Amy Kind: None

Maureen Smith: None

Jennifer Frytak: None

Michael Finch: None

Author Contributions: Amy Kind: Active in study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript

Maureen Smith: Active in study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript

Jennifer Frytak: Active in acquisition of data and preparation of manuscript

Michael Finch: Active in acquisition of data and preparation of manuscript

Sponsor’s Role: Not applicable

References

- 1.Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:549–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman EA, Min SJ, Chomiak A, et al. Posthospital care transitions: patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1449–1465. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:533–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurtado MP, Swift EK, Corrigan JM. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press: Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Heart Association. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics - 2004 Update. Dallas, TX: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claesson L, Gosman-Hedstrom G, Lundgren-Lindquist B, et al. Characteristics of elderly people readmitted to the hospital during the first year after stroke. The Goteborg 70+ stroke study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;14:169–176. doi: 10.1159/000065684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen HE, Schultz-Larsen K, Kreiner S, et al. Can readmission after stroke be prevented? Results of a randomized clinical study: a postdischarge follow-up service for stroke survivors. Stroke. 2000;31:1038–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutsch A, Fiedler RC, Granger CV, et al. The Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation report of patients discharged from comprehensive medical rehabilitation programs in 1999. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:133–142. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200202000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutsch A, Fiedler RC, Iwanenko W, et al. The Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation report: patients discharged from subacute rehabilitation programs in 1999. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82:703–711. doi: 10.1097/01.PHM.0000083665.58045.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith MA, Frytak JR, Liou JI, et al. Rehospitalization and survival for stroke patients in managed care and traditional Medicare plans. Med Care. 2005;43:902–910. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173597.97232.a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benesch C, Witter DM, Jr, Wilder AL, et al. Inaccuracy of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) in identifying the diagnosis of ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Neurology. 1997;49:660–664. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Uniform Billing Committee (NUBC) Form UB-92: American Hospital Association. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medicare/Medicaid Health Insurance Common Claim Form, Instructions and Supporting Regulations. Form No. CMS-1500, CMS-1490U, CMS-1490S (OMB #0938-0008). 2002.

- 14.Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pippenger M, Holloway RG, Vickrey BG. Neurologists’ use of ICD-9CM codes for dementia. Neurology. 2001;56:1206–1209. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samsa GP, Bian J, Lipscomb J, et al. Epidemiology of recurrent cerebral infarction: a Medicare claims-based comparison of first and recurrent strokes on 2-year survival and cost. Stroke. 1999;30:338–349. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.2.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horner RD, Sloane RJ, Kahn KL. Is use of mechanical ventilation a reasonable proxy indicator for coma among Medicare patients hospitalized for acute stroke? Health Serv Res. 1998;32:841–859. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quan H, Parsons GA, Ghali WA. Validity of procedure codes in International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification administrative data. Med Care. 2004;42:801–809. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000132391.59713.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SAS Statistical Software [computer program]. Version 8.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stata Statistical Software [computer program]. Version 8.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, et al. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the Care Transitions Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1817–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen HE, Schultz-Larsen K, Kreiner S, et al. Can readmission after stroke be prevented? Results of a randomized clinical study: a postdischarge follow-up service for stroke survivors. Stroke. 1038;31:1038–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kennedy BS. Does race predict stroke readmission? An analysis using the truncated negative binomial model. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:699–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ottenbacher KJ, Smith PM, Illig SB, et al. Characteristics of persons rehospitalized after stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1367;82:1367–1374. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.26088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoratti EM, Havstad S, Rodriguez J, et al. Health service use by African Americans and Caucasians with asthma in a managed care setting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:371–377. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.2.9608039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blixen CE, Havstad S, Tilley BC, et al. A comparison of asthma-related healthcare use between African-Americans and Caucasians belonging to a health maintenance organization (HMO) J Asthma. 1999;36:195–204. doi: 10.3109/02770909909056317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bazargan M, Johnson KH, Stein JA. Emergency department utilization among Hispanic and African-American under-served patients with type 2 diabetes. Ethn Dis. 2003;13:369–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deswal A, Petersen NJ, Souchek J, et al. Impact of race on health care utilization and outcomes in veterans with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:778–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi L, Macinko J, Starfield B, et al. Primary care, race, and mortality in US states. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaskin DJ, Hoffman C. Racial and ethnic differences in preventable hospitalizations across 10 states. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;1:85–107. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelley MA, Perloff JD, Morris NM, et al. Primary care arrangements and access to care among African-American women in three Chicago communities. Women Health. 1992;18:91–106. doi: 10.1300/J013v18n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rundek T, Mast H, Hartmann A, et al. Predictors of resource use after acute hospitalization: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Neurology. 1180;55:1180–1187. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen JK, Scott LB, Stewart KJ, et al. Disparities in women’s referral to and enrollment in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:747–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Himmelstein DU, Jones AA, Woolhandler S. Hypernatremic dehydration in nursing home patients: an indicator of neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:466–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb05118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ackermann RJ, Kemle KA, Vogel RL, et al. Emergency department use by nursing home residents. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:749–757. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saliba D, Kington R, Buchanan J, et al. Appropriateness of the decision to transfer nursing facility residents to the hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:154–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoenig H, Sloane R, Horner RD, et al. Differences in rehabilitation services and outcomes among stroke patients cared for in veterans hospitals. Health Serv Res. 2001;35:1293–1318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGlynn EA, Damberg CL, Kerr EA, et al. Health information systems: design issues and analytic applications. Santa Monica: RAND; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT., Jr Validating administrative data in stroke research. Stroke. 2002;33:2465–2470. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000032240.28636.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zweig SC, Kruse RL, Binder EF, et al. Effect of do-not-resuscitate orders on hospitalization of nursing home residents evaluated for lower respiratory infections. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]