Abstract

Random intermating of F2 populations has been suggested for obtaining precise estimates of recombination frequencies between tightly linked loci. In a simulation study, sampling effects due to small population sizes in the intermating generations were found to abolish the advantages of random intermating that were reported in previous theoretical studies considering an infinite population size. We propose a mating scheme for intermating with planned crosses that yields more precise estimates than those under random intermating.

MARKER applications such as marker-assisted backcrossing, marker-assisted selection, and map-based cloning require linkage maps with precise estimates of the recombination frequency r between tightly linked loci. The amount of information per individual

|

(1) |

(Mather 1936; Allard 1956), where nm is the size of the mapping population and  the expected variance of the recombination frequency estimate, is a statistic to compare alternative types of mapping populations with respect to the precision of recombination frequency estimates. To obtain a high mapping precision for tightly linked loci, t times intermated F2 mapping populations (

the expected variance of the recombination frequency estimate, is a statistic to compare alternative types of mapping populations with respect to the precision of recombination frequency estimates. To obtain a high mapping precision for tightly linked loci, t times intermated F2 mapping populations ( populations) were suggested (Darvasi and Soller 1995) and developed in Arabidopsis (Liu et al. 1996) and maize (Lee et al. 2002). Liu et al. (1996) derived ip for

populations) were suggested (Darvasi and Soller 1995) and developed in Arabidopsis (Liu et al. 1996) and maize (Lee et al. 2002). Liu et al. (1996) derived ip for  populations and found that ip for their

populations and found that ip for their  population was greater than that for an F2 population if r < 0.131.

population was greater than that for an F2 population if r < 0.131.

In their derivations, Liu et al. (1996) assumed random mating and infinite population sizes ni in the intermating generations. However, Falke et al. (2006) hypothesized that for finite ni sampling effects might overrule the increase in precision of estimates due to intermating. Martin and Hospital (2006) investigated estimation of recombination frequencies in recombinant inbred lines and found that maximum-likelihood estimates of r are biased if the relationship R = g(r) between r and the frequency R of recombinant gametes in the mapping population is nonlinear. The bias is determined by the size nm of the mapping population. For intermated populations, g is nonlinear and, hence, maximum-likelihood estimates of r from intermated populations are biased. Knowledge about the relative extent of (a) the reduction in ip due to finite sizes of intermating populations and (b) the bias of recombination frequency estimates due to finite sizes of mapping populations is important to assess the actual advantage of intermated populations over F2 base populations for linkage mapping. However, no results are available.

Our objectives were to (1) investigate with computer simulations the extent of the bias of maximum-likelihood estimates of r depending on the finite size nm of the mapping population assuming random mating with population size ni = ∞ in the intermating generations, (2) investigate with computer simulations the effect of finite population sizes ni in the intermating generations on the amount of information per individual ip in the mapping population, and (3) propose a mating scheme for intermating with planned crosses that results in the same ip values as random intermating with infinite population size.

Bias:

For intermated  mapping populations, the relation g between the recombination frequency r and the frequency of recombinant gametes R is

mapping populations, the relation g between the recombination frequency r and the frequency of recombinant gametes R is

|

(2) |

(Darvasi and Soller 1995). Because g is nonlinear, the maximum-likelihood estimator  (cf. Bailey 1961) of r is biased. Martin and Hospital (2006) employed a Taylor series expansion to derive a bias correction for arbitrary nonlinear g. Equation 18 of their derivations needs a correction. For g = f −1 it should read

(cf. Bailey 1961) of r is biased. Martin and Hospital (2006) employed a Taylor series expansion to derive a bias correction for arbitrary nonlinear g. Equation 18 of their derivations needs a correction. For g = f −1 it should read

|

(3) |

With this modification, the general form of the bias correction according to Martin and Hospital (2006) is

|

(4) |

where g′ and g″ are the first and second derivatives of g with respect to r. The bias-corrected estimator is then

|

(5) |

For  mapping populations, it can be calculated by using

mapping populations, it can be calculated by using

|

(6) |

and

|

(7) |

We conducted simulations with Plabsoft (Maurer et al. 2008) to investigate the extent of the bias of  and

and  in

in  and

and  mapping populations of size nm = 50, 100, 500, 100, and 5000, employing large population sizes ni = 25,000 in the intermating generations. For each nm we simulated 50,000 mapping populations in which

mapping populations of size nm = 50, 100, 500, 100, and 5000, employing large population sizes ni = 25,000 in the intermating generations. For each nm we simulated 50,000 mapping populations in which  and

and  were estimated for locus pairs with map distances

were estimated for locus pairs with map distances  . From the 50,000 simulated mapping experiments, the bias of

. From the 50,000 simulated mapping experiments, the bias of  and

and  was estimated as

was estimated as  and

and  .

.

For large population sizes (nm ≥ 500) and small recombination frequencies (r < 0.1), the bias of  was <10−4 in the

was <10−4 in the  and <3 × 10−4 in the

and <3 × 10−4 in the  mapping populations (Figure 1). However, for small populations (nm = 50, 100) and r = 0.1 the bias amounted to 10−3 and 4 × 10−3 in the

mapping populations (Figure 1). However, for small populations (nm = 50, 100) and r = 0.1 the bias amounted to 10−3 and 4 × 10−3 in the  and

and  mapping populations, respectively. Its absolute value was reduced efficiently by the bias correction. For example, for nm = 50 and r = 0.05 the bias of

mapping populations, respectively. Its absolute value was reduced efficiently by the bias correction. For example, for nm = 50 and r = 0.05 the bias of  in the

in the  was 3.6 × 10−4 and that of

was 3.6 × 10−4 and that of  was −1.2 × 10−4. In the

was −1.2 × 10−4. In the  mapping population the bias of

mapping population the bias of  was 10−3 and that of

was 10−3 and that of  was −7 × 10−5. For nm = 50 and recombination frequencies >0.1, the bias of

was −7 × 10−5. For nm = 50 and recombination frequencies >0.1, the bias of  was considerable, reaching its maximum value of ∼0.04 in the interval 0.2 < r < 0.3. For recombination frequencies r > 0.25 the bias correction resulted in a serious overcorrection (Figure 1).

was considerable, reaching its maximum value of ∼0.04 in the interval 0.2 < r < 0.3. For recombination frequencies r > 0.25 the bias correction resulted in a serious overcorrection (Figure 1).

Figure 1.—

Estimates of the bias  of the maximum-likelihood estimator

of the maximum-likelihood estimator  (left) and the bias

(left) and the bias  of the bias-corrected estimator

of the bias-corrected estimator  (right) for

(right) for  (top) and

(top) and  (bottom) mapping populations depending on the recombination frequency r. In the intermating generations, populations sizes ni = 25,000 were used. Sizes of the mapping populations were nm = 50, 100, 500, 1000, and 5000.

(bottom) mapping populations depending on the recombination frequency r. In the intermating generations, populations sizes ni = 25,000 were used. Sizes of the mapping populations were nm = 50, 100, 500, 1000, and 5000.

The goal of using intermated mapping populations is to increase the precision of recombination frequency estimates for tightly linked loci. Therefore, the properties of an estimator must be favorable for small values of r. For these, biasedness is not a serious problem of the maximum-likelihood estimator  . Nevertheless, the bias correction of Martin and Hospital (2006) with the modification presented in Equation 3 provides a means to reduce the bias to negligibly small values.

. Nevertheless, the bias correction of Martin and Hospital (2006) with the modification presented in Equation 3 provides a means to reduce the bias to negligibly small values.

Amount of information per individual:

The precision of alternative types of mapping populations can be compared by expressing their ip value as a proportion of the ip value of an F2 individual (Mather 1936):

|

(8) |

For F2 individuals Mather (1936) derived

|

(9) |

and for  individuals Liu et al. (1996) derived

individuals Liu et al. (1996) derived

|

(10) |

The derivations of Liu et al. (1996) assume infinite population sizes ni = ∞ in the intermating generations and, therefore, do not take into account an increase in the variance  due to sampling effects caused by finite population sizes ni.

due to sampling effects caused by finite population sizes ni.

Our investigations focus on the effect of finite population sizes ni in the intermating generations and a finite population size nm of an  mapping population on the amount of information per individual ip. The effect of finite ni is accounted for by carrying out simulations with finite population sizes. The effect of finite nm is accounted for by using a modified definition of the information content,

mapping population on the amount of information per individual ip. The effect of finite ni is accounted for by carrying out simulations with finite population sizes. The effect of finite nm is accounted for by using a modified definition of the information content,

|

(11) |

in which the variance  is replaced by the mean squared error

is replaced by the mean squared error  and, hence, the effect of the bias is considered.

and, hence, the effect of the bias is considered.

We investigated the effect of finite population sizes ni = 100, 200, 500 in the intermating generations on the amount of information ip of individuals in the  –

–  mapping populations of size nm = 100. For each type of mapping population and each ni, we simulated 50,000 mapping populations in which

mapping populations of size nm = 100. For each type of mapping population and each ni, we simulated 50,000 mapping populations in which  was estimated for locus pairs with map distances

was estimated for locus pairs with map distances  . From the 50,000 simulated mapping experiments, MSEr was estimated as

. From the 50,000 simulated mapping experiments, MSEr was estimated as  , from which ip and ir (Equations 11 and 8) were determined.

, from which ip and ir (Equations 11 and 8) were determined.

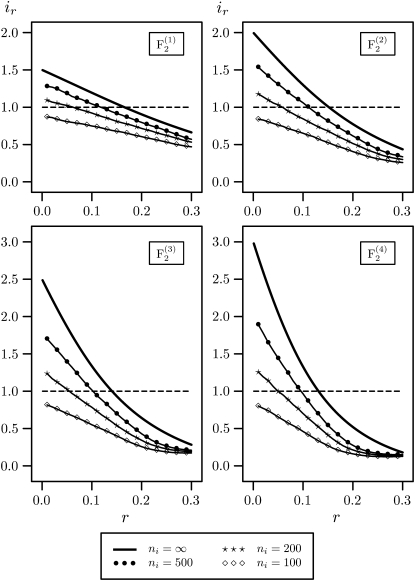

For ni = 100, the ir values were <1 for all types of mapping populations, irrespective of the recombination frequencies r (Figure 2). For ni = 200 and 500, the ir values were >1 if the recombination frequencies were > ≈0.05 and ≈0.1, respectively. Even with ni = 500, the ir values were considerably smaller than the ir values for infinite population sizes ni = ∞ calculated with Equation 10 (Liu et al. 1996).

Figure 2.—

Relative amount of information per individual ir in  –

–  mapping populations of size nm = 100 depending on the recombination frequency r. Simulation results are given for population sizes ni = 500, 200, and 100 in the intermating generations. For ni = ∞ the theoretical values (Equation 10) are presented.

mapping populations of size nm = 100 depending on the recombination frequency r. Simulation results are given for population sizes ni = 500, 200, and 100 in the intermating generations. For ni = ∞ the theoretical values (Equation 10) are presented.

We conclude that the population sizes ni of the intermating generations are the crucial factor for obtaining precise estimates of small r from  populations. A substantial gain in precision compared to estimation of recombination frequencies from the F2 base populations is achieved only if ni ≥ 500 are employed.

populations. A substantial gain in precision compared to estimation of recombination frequencies from the F2 base populations is achieved only if ni ≥ 500 are employed.

Mating scheme with independent recombinations:

From the assumption of infinite population sizes in the intermating generations it follows that the individuals of a mapping population do not have common ancestors in the F2 or intermating generations. Therefore, the recombination events in different individuals of the mapping population are stochastically independent. This stochastic independence is the key property of the model with infinite population sizes in the intermating generations, for which Liu et al. (1996) derived the information content per individual (Equation 10). For finite population sizes and random intermating, the above property of stochastic independence does not hold, because two individuals of the mapping populations can have a common ancestor with a probability larger than zero. This increases the standard error of the recombination frequency estimate and, hence, decreases the information content ip per individual. A mapping population consisting of nm individuals that have no common ancestors in F2 or later generations, i.e., with stochastic independence of recombination events in different individuals, can be generated with the following planned crossing scheme and finite population sizes ni.

For generating an  mapping population of size nm, an F2 population of size 2tnm is generated. Then, 2t−1nm pairs of F2 plants are crossed and from each cross one single

mapping population of size nm, an F2 population of size 2tnm is generated. Then, 2t−1nm pairs of F2 plants are crossed and from each cross one single  plant is generated, resulting in an

plant is generated, resulting in an  population of size 2t−1nm. The procedure is repeated in each subsequent generation, by producing exactly one progeny from the cross of two individuals of the parental population. Continuing the procedure for t generations results in a

population of size 2t−1nm. The procedure is repeated in each subsequent generation, by producing exactly one progeny from the cross of two individuals of the parental population. Continuing the procedure for t generations results in a  mapping population of size nm.

mapping population of size nm.

Mapping populations generated with this “mating scheme with independent recombinations” have the same properties as mapping populations derived from large random-mating populations. In such populations, the amount of information ip per individual is the same as in Equation 10. Hence, the mating scheme guarantees the maximum possible information content in the mapping population but reduces the efforts of employing large intermating populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Frank M. Gumpert for checking the derivations, Jasmina Muminović for her editorial work, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions.

References

- Allard, R. W., 1956. Formulas and tables to facilitate the calculation of recombination values in heredity. Hilgardia 24: 235–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, N. T. J., 1961. Mathematical Theory of Genetical Linkage. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Darvasi, A., and M. Soller, 1995. Advanced intercross lines, an experimental population for fine genetic mapping. Genetics 141: 1199–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falke, K. C., A. E. Melchinger, C. Flachenecker, B. Kusterer and M. Frisch, 2006. Comparison of linkage maps from F2 and three times intermated generations in two populations of European flint maize (Zea mays L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 113: 857–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M., N. Sharopova, W. D. Beavis, D. Grant, M. Katt et al., 2002. Expanding the genetic map of maize with the intermated B73 x Mo17 (IBM) population. Plant Mol. Biol. 48: 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.-C., S.-P. Kowalski, T.-H. Lan, K. A. Feldmann and A. H. Paterson, 1996. Genome wide high resolution mapping by recurrent intermating using Arabidopsis thaliana as a model. Genetics 142: 247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, O. C., and F. Hospital, 2006. Two- and three-locus tests for linkage analysis using recombinant inbred lines. Genetics 173: 451–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather, K., 1936. Types of linkage data and their values. Ann. Eugen. 7: 251–264. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, H. P., A. E. Melchinger and M. Frisch, 2008. Population genetic simulation and data analysis with Plabsoft. Euphytica (in press).